Summary

A key feature of escape responses is the fast translation of sensory information into a coordinated motor output. In C. elegans anterior touch initiates a backward escape response in which lateral head movements are suppressed. Here we show that tyramine inhibits head movements and forward locomotion through the activation of a tyramine-gated chloride channel, LGC-55. lgc-55 mutant animals have defects in reversal behavior and fail to suppress head oscillations in response to anterior touch. lgc-55 is expressed in neurons and muscle cells that receive direct synaptic inputs from tyraminergic motor neurons. Therefore, tyramine can act as a classical inhibitory neurotransmitter. Activation of LGC-55 by tyramine coordinates the output of two distinct motor programs, locomotion and head movements that are critical for a C. elegans escape response.

Introduction

Biogenic amines play an important role in the modulation of behaviors in a wide variety of organisms. In contrast to the classical biogenic amines, like dopamine or serotonin, roles for trace amines in the nervous system remain elusive. The trace amine, tyramine is found in the nervous system of animals ranging from nematodes to mammals. Tyramine has often been considered as a metabolic byproduct, or intermediate in the biosynthesis, of the classical biogenic amines. However, the characterization of invertebrate and mammalian G-protein coupled receptors that can be activated by tyramine has piqued new interest in the role of tyramine in animal behavior and physiology. The mammalian trace-amine associated receptor TAAR1, has a high affinity for tyramine and beta-phenylethylamine and is broadly expressed in the mammalian brain (Borowsky et al., 2001; Miller et al., 2005). Tyramine responsive G-protein coupled receptors have been characterized in fruit flies, locusts, honeybees, silk moths and nematodes (Blenau et al., 2000; Ohta et al., 2003; Rex et al., 2005; Rex and Komuniecki, 2002; Saudou et al., 1990). However, it is unclear whether tyramine is the endogenous ligand for these receptors and the role of tyramine in animal physiology and behavior remains relatively unexplored.

Like in mammals, tyramine levels in invertebrates are much lower than those of the classic invertebrate biogenic amines, dopamine, serotonin and octopamine (Cole et al., 2005; Monastirioti et al., 1996). In invertebrates tyramine is also a precursor in the biosynthesis of octopamine, often considered to be the invertebrate analog of norepinephrine (Roeder et al., 2003). In C. elegans tyramine is synthesized from tyrosine by a tyrosine decarboxylase (tdc-1), and a tyramine beta-hydroxylase (tbh-1) is required to convert tyramine to octopamine (Alkema et al., 2005). TDC-1 and TBH-1 are co-expressed in a single pair of interneurons, the RICs, and in gonadal sheath cells, indicating that these cells are octopaminergic. TDC-1 is also expressed on its own in the RIM motor neurons and the uterine UV1 cells suggesting that these cells are uniquely tyraminergic in C. elegans. Furthermore, animals that lack tyramine and octopamine (tdc-1 mutants) have behavioral defects that are not shared by animals that only lack octopamine (tbh-1 mutants), suggesting a distinct role for tyramine in C. elegans behavior (Alkema et al., 2005). tdc-1 mutants, unlike tbh-1 mutants, have defects in egg laying, reversal behavior and fail to suppress head movements in response to gentle anterior touch. The C. elegans neural wiring diagram (White et al., 1986) and cell ablation studies indicate that the tyraminergic RIM motorneurons link the neural circuits that control locomotion and head movements. In the wild, the suppression of head movements in response to touch may allow the animal to escape nematophagous fungi that trap nematodes with constricting hyphal rings (Barron, 1977).

The study of relatively simple circuits in invertebrates has provided fundamental insights on how biogenic amines change the output of distinct motor programs (Marder and Bucher, 2001; Katz et al., 1994; Nusbaum and Beenhakker, 2002). In this report, we show that tyramine inhibits head movements and induces long backward runs through the activation of a tyramine-gated chloride channel, LGC-55. lgc-55 is expressed in cells that are postsynaptic to the tyraminergic RIM neurons and the activation of LGC-55 inhibits the neural circuits that drive head movements and locomotion. Our data firmly establish tyramine as a classical neurotransmitter in C. elegans and suggest that fast inhibitory tyraminergic transmission plays a critical role in coordinating a C. elegans escape response.

Results

Exogenous tyramine induces backward locomotion and inhibits head movements

C. elegans moves on its side in a sinusoidal pattern by propagating dorso-ventral waves of body wall muscle flexures along the length of its body. Locomotion is accompanied by exploratory head movements, where the tip of the nose of the animal moves from side to side. Head movements are controlled independently from body movements by a set of radially symmetric head and neck muscles. The tyraminergic RIM motorneurons make synaptic connections with neck muscles that control head movements and command neurons that drive locomotion (Figure 1). To study how tyramine signaling might control head and body movements during locomotion, we developed a simple assay for measuring behavioral responses to tyramine. We found that wild-type animals became immobilized on agar plates containing exogenous tyramine in a dose-dependent manner (See Figure S1 Supplemental Data). In extended behavioral studies of individual worms in the presence of 30 mM exogenous tyramine, we noted a progressive sequence of behaviors that were nearly invariant from animal to animal (Figure 1). Wild-type animals displayed a brief period of forward locomotion in which head movements ceased completely, while sinusoidal body movements in the posterior half of the animal persisted. Immobilization of head movements was followed by strikingly long backward locomotory runs (Figure 1A and Figure 7D, See Movie S2). Following this behavioral sequence, most wild-type animals became completely immobilized within 5 minutes of tyramine exposure. Locomotion could still be triggered in immobilized animals by mechanical stimulation with a platinum wire. However, movements were restricted to the posterior half of the animal (body movements) while the head remained paralyzed (See Movie S3). These results support the idea that exogenous tyramine affects head movements and locomotory body movements through distinct tyraminergic signaling pathways.

Figure 1. Exogenous Tyramine Induces Long Reversals and Suppresses Head Movements.

(A) Still image of locomotion pattern of wild-type animals on 30 mM tyramine prior to immobilization. The x marks the starting location and the dashed line marks the backward locomotory run (See Supplemental Movie S1). Inset: the main synaptic outputs of the tyraminergic RIM motorneurons include the AVB forward locomotion command neurons, the RMD and SMD motorneurons and neck muscles. (B) Overlay of three still images of wild type and lgc-55(zf11) after five minutes on exogenous tyramine. Images were taken approximately 2 s apart. Wild-type animals completely immobilize. lgc-55 mutants move their heads while their body remains immobilized. (C) Quantification of head and body movements on 30 mM tyramine. Shown is the percentage of animals immobilized by tyramine each minute for 20 min. Each data point is the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) for at least four trials totaling 40 or more animals. lgc-55 mutants continue to move their heads through the duration of the assay, while the body immobilizes similarly to wild-type animals.

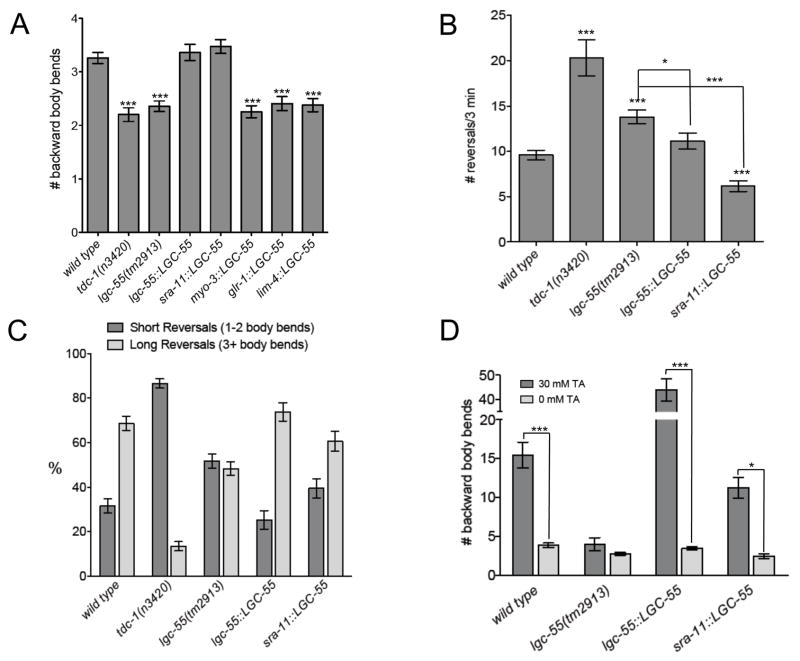

Figure 7. lgc-55 Mutants Have defects in Reversal Behavior.

(A) Average number of backward body bends in response to anterior touch of wild-type (n= 317), tdc-1(n3420) (n=139), lgc-55(tm2913) (n=257), lgc-55 rescue [lgc-55(tm2913); zfEx2, (n=204)], sra-11::LGC-55 [lgc-55(tm2913); zfEx37, (n=190)], myo-3::LGC-55 [lgc-55(tm2913); zfEx31, (n=157)], glr-1::LGC-55 [lgc-55(tm2913); zfEx42, (n=133)], and lim-4::LGC-55 [lgc-55(tm2913); zfEx44, (n=108)] animals. (B) Number of spontaneous reversals in 3 minutes of well fed wild-type (n=55), tdc-1(n3420) (n=16), lgc-55(tm2913), (n=40), lgc-55 rescue [lgc-55(tm2913); zfEx2, (n=27)], and sra-11::LGC-55 [lgc-55(tm2913); zfEx37, (n=32)] animals on plates without food. Statistical difference from wild type unless otherwise noted; ***p<0.0001, *p<0.01, two-tailed Student’s t test. (C) Distribution of short (1-2 body bends) and long (3+ body bends) spontaneous reversals made in 3 minutes. p<0.001, two-way ANOVA. (D) Number of backward body bends made during the longest backward run before paralysis on 30 mM tyramine of wild-type (n=33), lgc-55(tm2913) (n=20), lgc-55 rescue [lgc-55(tm2913); zfEx2, (n=20)], and sra-11::LGC-55 [lgc-55(tm2913); zfEx37, (n=29)] animals. 0 mM data represent the number of backward body bends during the longest backward run made in 3 min on agar plates without food for wild-type (n=28), lgc-55(tm2913) (n=20), lgc-55 rescue [lgc-55(tm2913); zfEx2 (n=20)], and sra-11::LGC-55 [lgc-55(tm2913); zfEx37, (n=12)] animals. p<0.0001, two-way ANOVA; ***p<0.001, *p<0.01, Bonferroni post-test. Error bars represent SEM.

lgc-55 mutants are partially resistant to exogenous tyramine

To identify genes involved in tyramine signaling we performed a genetic screen for mutants that are resistant to the paralytic effects of exogenous tyramine. We placed F2 progeny of 10,000 mutagenized hermaphrodites on agar plates containing 30 mM tyramine and selected rare mutants that displayed sustained body and/or head movements. Two mutants isolated from this screen, zf11 and zf53, became immobilized slightly more slowly than wild-type animals and continued head movements on plates containing exogenous tyramine (Figure 1B and 1C). However, neither zf11 nor zf53 mutant animals displayed any body movements posterior to the pharynx (See Movie S4). Furthermore, exogenous tyramine failed to induce long backward locomotory runs in the zf11 and zf53 mutants (See Figure 7D). zf11 and zf53 mutant animals were healthy and viable with normal brood sizes and had no obvious defects in locomotion pattern or head movements in the absence of exogenous tyramine.

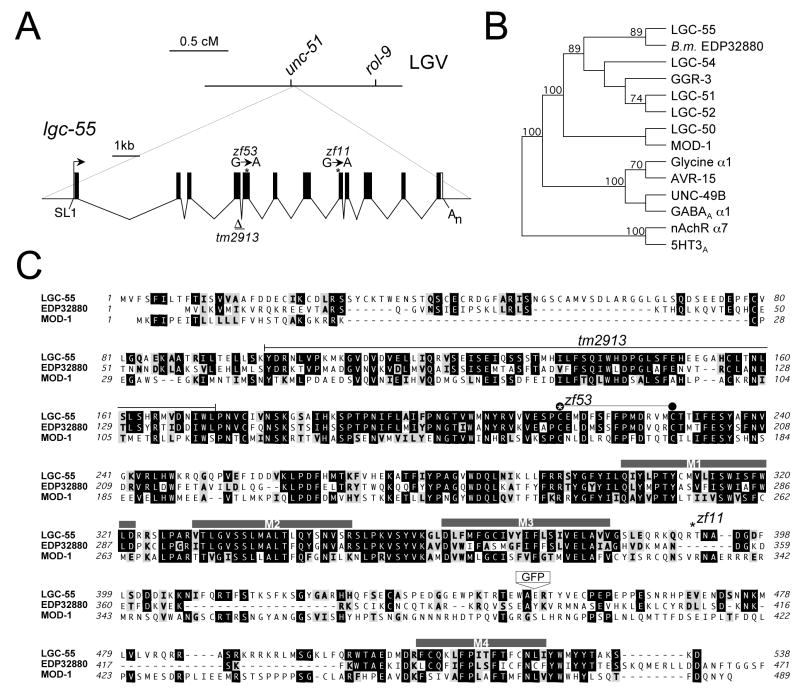

We mapped zf11 using single nucleotide polymorphisms and three-factor mapping to the right of chromosome V close to unc-51 (Figure 2A). This genomic region contains a gene, lgc-55, which encodes a protein with similarity to members of the cysteine-loop ligand-gated ion channels (Cys-loop LGIC) (Figure 2B) (Betz, 1990). Sequence analysis revealed single-base transitions in the lgc-55 coding sequence in zf11 and zf53 mutants. The lgc-55 gene structure was confirmed by analysis of expressed sequence tagged full-length cDNA clones. The predicted LGC-55 protein is comprised of a large extracellular ligand-binding domain with a characteristic Cys-loop motif, four transmembrane domains (M1-M4) and a large intra-cellular domain between M3 and M4 (Figure 2C). The zf11 allele mutates a splice acceptor site of exon 9, which causes a frame shift that would lead to premature truncation of the LGC-55 protein. The zf53 allele converts the first cysteine codon of the Cys-loop to a tyrosine (C215Y). The cysteines of the Cys-loop motif in the N-terminal extracellular ligand-binding region of each subunit form a disulphide bond that plays a key role in receptor assembly (Green and Wanamaker, 1997) and gating of the ion channel (Grutter et al., 2005). We also obtained an available deletion allele tm2913, which deletes parts of both exon 4 and 5 of the lgc-55 gene. The deletion should prematurely truncate the LGC-55 protein and therefore most likely represents a null allele. Like lgc-55(zf11) and lgc-55(zf53) mutants, lgc-55(tm2913) mutants animals are resistant to tyramine-mediated head paralysis, suggesting that lgc-55(zf11) and lgc-55(zf53) also represent loss-of-function alleles. We were able to restore tyramine sensitivity by expressing a transgenic lgc-55 minigene in lgc-55 mutants (Figure 1C). These data indicate that lgc-55 is required for the paralytic effects of exogenous tyramine on head movements.

Figure 2. lgc-55 encodes a ligand-gated ion channel subunit.

(A) The lgc-55 locus. Genetic map and gene structure of lgc-55: coding sequences are represented as black boxes; untranslated regions are represented as white boxes. The SL1 trans-spliced leader and the poly(A) tail are indicated. The position of the lgc-55(zf11) allele lgc-55(zf53) and lgc-55(tm2193) allele are indicated. The lgc-55(tm2913) has a 285 bp deletion that removes part of exon 4 and exon 5. The deleted region indicated by bars. (B) Phylogenetic tree of LGC-55 and various ligand-gated ion channel subunits. Predicted C. elegans LGICs (Jones and Sattelle, 2008), including the 5HT receptor MOD-1, glutamate receptor AVR-15, GABA receptor UNC-49B, the Brugia malayi predicted protein EDP32880, and human GABAAα1, nAchRα7 and 5HT3A. A neighbor weighted tree of decarboxylase-conserved regions based on bootstrap analysis and the Unweighted Pair Group Method with Arithmetic Mean (UPGMA) was determined using MacVector software (Accelrys). (C) Alignment of LGC-55 with MOD-1 and the closely related predicted protein from Brugia malayi, EDP32880. Identities are outlined in black and similarities are shaded. The four predicted transmembrane domains are indicated by black bars, and the Cys-loop is indicated by a line with two black with black circles. The LGC-55 zf11 and zf53 mutations are indicated by stars, the black line denotes the amino acids deleted in the tm2913 allele. The position of the GFP insertion of the LGC-55::GFP translational fusion is indicated.

LGC-55 is an ionotropic tyramine receptor

Cys-loop LGIC receptors, like nicotinic acetylcholine (nAChR), γ-aminobutyric acid (GABAAR), glycine (GlyR) and serotonin (5HT3AR) receptors, form pentameric complexes in the cell membrane (Betz, 1990). Ligand binding at the N-terminal domain induces a conformational change causing the pore of the channel to open. LGC-55 is most closely related to this family of ligand-gated ion channels, in particular the GABA-, glycine-gated chloride channels as well as the C. elegans 5HT-gated chloride channel, MOD-1 (Ranganathan et al., 2000) (Figure 2B). Additionally, we identified orthologues of LGC-55 in the genomes of the closely related nematode species C. briggsae (CBP26358, 94% identity), C. remanei (RP28082, 95% identity), Pristionchus pacificus (PP01401, 70% identity) and the more distantly related parasitic nematode Brugia malayi (EDP32880, 52% identity).

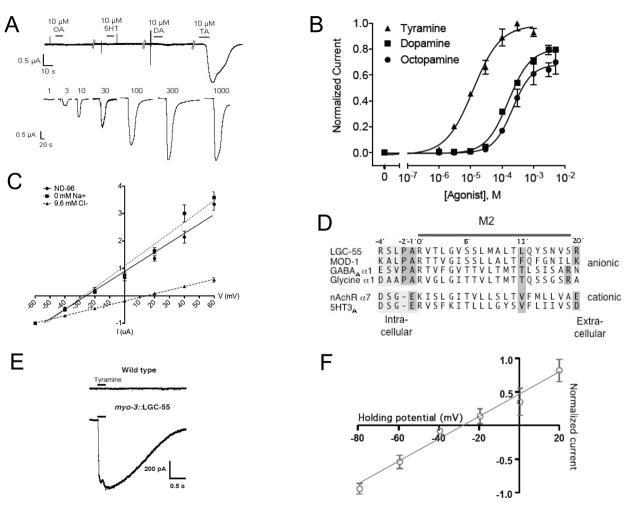

To determine whether LGC-55 can form functional homomeric channels, we expressed lgc-55 in Xenopus laevis oocytes for two-electrode voltage clamp recordings. In lgc-55 injected oocytes, application of tyramine in concentrations ranging from 1–1000 μM evoked robust and rapidly developing inward currents up to 2.2 μA (Figure 3A). Application of tyramine to mock injected oocytes showed no such response (data not shown). The EC50 (effective concentration for half maximal response) for tyramine activation of LGC-55 receptors was 12.1 ± 1.2 μM, a concentration well within the range of EC50 values defined for neurotransmitters that activate closely related LGIC family members (Figure 3B). These data indicate that LGC-55 forms a functional homomeric receptor that can be activated by tyramine. The EC50 of the structurally related amines, octopamine and dopamine, is approximately 10-fold lower than those for tyramine (EC50 = 215.2 ± 1.1 μM and 158.8 ± 1.1 μM respectively), whereas serotonin only elicited small LGC-55-dependent inward currents at millimolar concentrations. GABA, glycine, acetylcholine, and histamine did not elicit any significant LGC-55-dependent inward currents even at concentrations as high as 1 mM. Although octopamine and dopamine may activate LGC-55 in vivo, tyramine is the most potent activator of LGC-55, suggesting that tyramine could function as the native ligand for LGC-55.

Figure 3. LGC-55 is a Tyramine Gated Chloride Channel.

(A) Representative traces from Xenopus oocytes injected with lgc-55 cRNA showing responses to 10 μM octopamine (OA), serotonin (5HT), dopamine (DA), and tyramine (TA) as well 1–1000 μM TA in ND-96. Neurotransmitters were bath-applied for 10 s. (B) LGC-55 TA, OA and DA dose response curves. EC50TA = 12.1 ± 1.2 μM and Hill Coefficient = 1.0 ± 0.17, EC50DA = 158.8 ± 1.1 μM, EC50OA = 215.2 ± 1.1 μM. Each data point represents the mean current value normalized to the mean maximum current observed for tyramine, (Imax = 2.2 ± 0.17 μA). Error bars represent SEM. (C) Ion selectivity of LGC-55 in Xenopus oocytes. TA-evoked (10 μM, 10 s) currents were recorded at the holding potentials shown. Circles: standard ND-96 (Erev = −25.7 ± 0.9 mV, n=4); squares: 0 mM Na+ (Erev = −27.2 ± 1.3 mV, n=4); triangles: 9.6 mM Cl− (Erev= 15.0 ± 2.6 mV, n=4). I-V curves were plotted using linear regression, error bars represent SEM. (D) Alignment of the M2 region of LGC-55 with other members of the Cys-loop ligand-gated ion channel family. Shaded regions indicate residues important for ion selectivity. (E) Representative current responses to tyramine application (200 μM) recorded from C. elegans body wall muscle cells of wild-type (upper) or transgenic animals expressing myo-3::LGC-55 (lower). Black bars indicate duration of tyramine application (250 ms). (F) Current-voltage relationship for LGC-55 receptors expressed in C. elegans body wall muscle cells under normal recording conditions. Current responses to tyramine were recorded at the holding potentials indicated.

LGC-55 is a tyramine gated chloride channel

The ion selectivity of cys-loop LGICs is determined by the M2 domain, which lines the pore of the ion channel. LGC-55 contains a PAR motif on the cytoplasmic side of the M2 domain, which is conserved in most anion-selective channels (Figure 3D) (Karlin and Akabas, 1995). To determine the ion selectivity we analyzed the current-voltage (I-V) relationship for LGC-55 under a variety of ionic conditions. Under our standard recording conditions (100 mM Cl−), current responses to tyramine application reversed at −25.7 ± 0.9 mV (Figure 3C), consistent with the chloride equilibrium potential (ECl) in Xenopus oocytes (Weber, 1999). This is similar to the reported reversal potential of other C. elegans chloride selective channels, such as the UNC-49B/GABA receptor (Bamber et al., 1999) and the serotonin-gated chloride channel, MOD-1 (Ranganathan et al., 2000) and significantly different from the near 0 mV reversal potential normally observed for non-selective cation channels. Furthermore, after complete substitution of extracellular sodium with the large impermeant cation N-methyl-D-glucamine (NMDG), we did not observe an obvious change in reversal potential (ErevNMDG = −27.2 ± 1.3 mV), suggesting that sodium ions do not significantly contribute to the current passing through the LGC-55 ion channel (Figure 3C).

To test how changes in the chloride ion concentration affected the reversal potential of LGC-55, we substituted external chloride with the large anion gluconate. When the chloride concentration was reduced by 10-fold, we observed a rightward shift in reversal potential of approximately 40 mV (Erevgluconate = 14.9 ± 2.6) (Figure 3C). These data are consistent with corresponding shifts predicted by the Nernst equation and indicate that LGC-55 is a chloride selective channel. To test whether the LGC-55 receptors expressed in vivo were also chloride selective, we expressed lgc-55 in C. elegans body wall muscles using the muscle-specific myo-3 promoter (myo-3::LGC-55) and recorded current responses to tyramine using whole-cell patch clamp electrophysiology (Figure 3E). While we never detected measurable current responses to tyramine in body wall muscles of wild-type worms, we noted robust responses to tyramine in the body wall muscles of transgenic worms expressing LGC-55. Consistent with our results for heterologously expressed LGC-55 receptors, current responses to tyramine reversed at approximately −30 mV (Figure 3F), near the predicted reversal potential for an anion-selective channel under our conditions (Francis and Maricq, 2006).

LGC-55 is expressed in cells that are postsynaptic to the tyraminergic RIM motorneurons

To determine the expression pattern of lgc-55 we generated translational fluorescent reporter constructs. A 7 kb lgc-55 genomic fragment including a 3.5 kb promoter and the first intron was fused to the open reading frame of green (GFP) (Chalfie et al., 1994) and red (mCherry) fluorescent reporters (Shaner et al., 2004). lgc-55::mCherry and lgc-55::GFP transgenic animals showed reporter expression in a subset of neck muscles, and a restricted set of neurons (Figure 4). We have identified these neurons as the AVB, RMD, SMDD, SMDV, IL1D, IL1V, SDQ, HSN and ALN neurons (Figure 4A, B, C, and S5-7). In addition, weak lgc-55 reporter expression was also detected in the UV1 cells and tail muscle cells.

Figure 4. Expression Pattern of lgc-55.

(A) Adult animal showing expression of a fluorescent lgc-55::mCherry (zfIs4) transcriptional reporter in neck muscles, head neurons, SDQ, HSN and ALN neurons. (B) Head region of an adult animal showing expression of lgc-55::mCherry in head neurons, IL1, RMD, SMD, and AVB. (C) Expression of lgc-55::GFP (zfIs6) in the HSN and uterine UV1 cells. The star indicates position of the vulva. (D) Expression of lgc-55::GFP in the third row of neck muscle cells. (E) Expression of LGC-55::GFP (zfEx38) translational reporter showing subcellular localization to neuronal cell bodies, nerve ring and muscle arms. Position of the nerve ring is indicated by the dotted line. Scale bar, 10 μm. Anterior is to the left and ventral side is down in all images.

To visualize the localization of the LGC-55 protein we fused the GFP coding sequence between the M3 and M4 coding domain of the minimal rescuing construct. The LGC-55::GFP construct rescued the sensitivity of lgc-55(tm2913) mutants to exogenous tyramine and also rescued defects in the suppression of head oscillations (data not shown), indicating that LGC-55::GFP is, at least in part, properly localized to restore tyraminergic signaling. LGC-55::GFP fluorescence was observed in neuronal cell bodies and punctate structures in the nerve ring suggestive of postsynaptic specializations (Figure 4E). In C. elegans, muscles extend cytoplasmic arms that synapse with bundles of motor neuron processes (White et al., 1986; Hall and Altun, 2007). Neck muscle arms turn anteriorly into the nerve ring where they make synapses with the head motorneurons including the tyraminergic RIMs. Therefore, the LGC-55::GFP puncta in the nerve ring suggest that LGC-55 receptors cluster at post synaptic sites that may include neuromuscular synapses between the RIMs and the neck muscles. The neck muscles, the AVB, RMD, SMDD and SMDV neurons are postsynaptic to the tyraminergic RIM motor neurons (White et al., 1986), consistent with tyramine being an endogenous ligand of LGC-55. The HSN, IL1, SDQ and ALN neurons send processes to the nerve ring but do not receive direct synaptic input from the RIM suggesting that LGC-55 may also act extrasynaptically. Furthermore, tyramine release from non-neuronal cells, such as the uterine UV1 cells, could activate LGC-55.

lgc-55 is required in neck muscles to suppress head oscillation in response to anterior touch

Gentle touch to the anterior half of the body of C. elegans elicits an escape response in which the animal reverses its direction of locomotion (Chalfie et al., 1985). Wild-type animals suppress head oscillations during this backing response (Movie S8). Mutant animals that lack tyramine, and animals in which the tyraminergic RIM motorneurons are ablated, fail to suppress head oscillations in response to anterior touch (Alkema et al., 2005). lgc-55 mutants had no obvious defects in locomotion pattern or head oscillations during normal foraging. However, we found that lgc-55 mutant animals failed to suppress head oscillations in response to anterior touch (Figure 5, Movie S9).

Figure 5. lgc-55 Mutants Fail to Suppress Head Oscillations in Response to Anterior Touch.

(A) Illustration of C. elegans head movements during locomotion. Wild-type animals and lgc-55 mutants oscillate their heads during forward locomotion. Anterior touch of wild-type animals with an eyelash induces a reversal response during which the head oscillations are suppressed. lgc-55 mutants fail to suppress head oscillations during the reversal. (B) Expression patterns of promoters used for cell specific rescue of lgc-55: lim-4 (Sagasti et al., 1999); glr-1 (Hart et al., 1995; Maricq et al., 1995); sra-11 (Altun-Gultekin et al., 2001) and myo-3 (Okkema et al., 1993). Note: We could not detect expression of a glr-1::GFP reporter in the AVB neurons of adult transgenic animals; See Figure S5-S7. Cells overlapping with lgc-55 expression are indicated in bold. (C) Suppression of head oscillations in response to anterior touch was scored during the reversal response, wild-type (n=235), lgc-55 mutants [lgc-55(tm2913), n=205; lgc-55(zf11), n=205, lgc-55(zf53), n=170], lgc-55 rescue [lgc-55(tm2913); zfEx2, (n=205)], myo-3::LGC-55 [lgc-55(tm2913); zfEx31, (n=100)], sra-11::LGC-55 [lgc-55(tm2913); zfEx37, (n=185)], glr-1::LGC-55 [lgc-55(tm2913); zfEx42, (n=130)], and lim-4::LGC-55 [lgc-55(tm2913); zfEx44, (n=115)]. Error bars represent SEM. Statistical difference from wild type; ***p<0.0001, two-tailed Student’s t test. ‡ p<0.0001, two- tailed Student’s t test. glr-1::LGC-55 transgenic animals do not completely suppress head oscillations and appear to have a kinked head during reversals in response to anterior touch. See text for details.

How does the tyramine-gated chloride channel suppress head oscillations in response to anterior touch? Head movements that accompany foraging behavior are controlled by the excitatory cholinergic RMD and SMD neurons and the inhibitory GABAergic RME neurons that provide synaptic inputs to the neck muscles (Hart et al., 1995; Gray et al., 2005). The RMD and SMD neurons are coupled through gap junctions and reciprocal synaptic connections, and innervate contralateral neck muscles (White et al., 1986). The RMD neurons display bistable potentials, which may contribute to the oscillatory head movements (Mellem et al., 2008). The GABAergic RME neurons synapse onto the neck muscles as well as the RMD and SMD neurons and limit the extent of head deflection during head oscillations (McIntire et al., 1993).

We observed strong lgc-55::GFP expression in the RMD and SMD neurons as well as 8 radially symmetric neck muscle cells (Figure 4B and D). We therefore sought to identify the cells in which lgc-55 acts to suppress head oscillations in response to anterior touch using cell specific rescue and mosaic analysis. For the first approach we expressed the lgc-55 cDNA under the control of cell specific promoters in the lgc-55(tm2913) mutants. We used the following promoters to drive the expression of lgc-55 in specific subsets of cells: lim-4: the RMD neurons (plus 5 additional neurons) (Sagasti et al., 1999); glr-1: the RMD and SMD neurons (plus 14 additional neurons) (Hart et al., 1995; Maricq et al., 1995); sra-11: the AVB neurons (plus 2 additional neurons) (Altun-Gultekin et al., 2001) and myo-3: body wall muscle (including neck muscle) (Okkema et al., 1993) (Figure 5B). Expression of lgc-55 in the AVB (sra-11::LGC-55) or RMD (lim-4::LGC-55) neurons failed to rescue the defect in the suppression of head oscillations (Figure 5C). Animals that expressed lgc-55 in the RMD and SMD neurons (glr-1::LGC-55) also did not fully rescue the suppression of head oscillations but usually kinked their head to one side while reversing. However RMD and SMD expression did restore sensitivity to the paralyzing effects of exogenous tyramine in head movement assays (Figure S10). The expression of myo-3::LGC-55 in muscle, on the other hand, fully rescued the defect in the suppression of head oscillations of lgc-55 mutants (Figure 5C) and restored sensitivity to the paralyzing effects of exogenous tyramine in head movement assays (Figure S10). Animals in which lgc-55 expression was rescued in body wall muscle displayed normal locomotion and backing in response to touch, suggesting that tyraminergic activation of lgc-55 mainly occured synaptically at the RIM-neck muscle neuromuscular junctions.

As a second approach we performed genetic mosaic analysis. The lgc-55 expressing neurons are derived from the embryonic AB blastomere, whereas the body wall muscles are derived from the P1 blastomere (Figure 6A). Using GFP and mCherry markers, we selected animals that had lost a rescuing extra-chromosomal array in either the descendants of the AB blastomere or the descendants of the P1 blastomere. Mosaic animals that lost the array in the P1 lineage failed to suppress head oscillations whereas animals that lost the array in the AB lineage did suppress head oscillations in response to touch (Figure 6B). Exogenous tyramine could still inhibit head movements in animals that lost the rescuing array in the P1 lineage, albeit to lesser extent than animals that lost the array in the AB lineage. These results indicate that even though LGC-55 expression in the RMD and SMD neurons may contribute to the suppression, LGC-55 expression in neck muscles is necessary and sufficient to fully suppress lateral head movements upon anterior touch. However, lgc-55 expression in neurons was required to mediate the tyraminergic stimulation of backward locomotion, since exogenous tyramine did not induce long backward locomotory runs in animals that had lost the array in the AB lineage (see below).

Figure 6. lgc-55 is Required in Neck Muscles to Suppress Head Oscillations.

(A) Diagram of C. elegans early cell lineage. lgc-55 expressing cells derived from AB and P1 are indicated. (B) Mosaic Analysis. An lgc-55 rescuing construct was injected into lgc-55(tm2913) mutant animals together with lgc-55::mCherry and myo-3::GFP as lineage markers. Animals lacking lgc-55 function in either the AB or P1 lineages and non-mosaic controls were analyzed for suppression of head oscillations in response to anterior touch, head paralysis after 5 min. on exogenous tyramine (30 mM) and longest backward run on 30 mM tyramine. Data shown are the mean ± SEM.

lgc-55 acts in the AVB forward locomotion command neurons to modulate reversal behavior

On agar plates C. elegans mainly displays forward locomotion interrupted by brief backward locomotory runs. The neural circuit that controls forward and backward locomotion consists of four pairs of locomotion command interneurons: the PVC and AVB neurons are primarily required for forward locomotion whereas the AVD and AVA neurons are required for backward locomotion (Chalfie et al., 1985). Electrophysiology, Ca2+ imaging and genetic experiments indicate that depolarization of the forward locomotion command neurons results in forward locomotion whereas depolarization of the backward locomotion command neurons drives backward locomotion (Chronis et al., 2007; Zheng et al., 1999). The forward and backward locomotion command neurons make reciprocal synaptic connections, which may link the neural activities underlying these antagonistic behaviors and allow the animal to switch its direction of locomotion. The tyraminergic RIM neurons are electrically coupled through gap junctions with the AVA backward command neurons and have synaptic outputs onto the AVB forward locomotion command neurons. Although tyramine deficient animals normally initiate backward locomotion in response to anterior touch, they back up less far than the wild type. In addition, tyramine deficient animals have a marked increase in the number of spontaneous reversals indicating that tyramine modulates reversal behavior (Alkema et al., 2005).

We tested whether lgc-55 mutants have defects in reversal behavior. Like tdc-1 mutants, lgc-55 mutants initiated backward locomotion normally in response to anterior touch but displayed shorter runs of backward movement (2.4 ± 0.1 body bends) than the wild type (3.3 ± 0.1 body bends) (Figure 7A and S11). In addition, we found that lgc-55 mutants had an increase in spontaneous reversals compared to the wild type, although the increase was less pronounced than that of the tdc-1 mutants (Figure 7B). To examine spontaneous reversal behavior in more detail we categorized the reversals according to the number of backward body bends (Gray et al., 2005). We found that lgc-55 mutants displayed more short reversals than wild-type worms (Figure 7C). The increase in short reversals was even more dramatic in the tdc-1 mutants. An lgc-55 minigene rescued the defects of lgc-55 mutants in reversal behavior in both the touch-induced and spontaneous reversal assays.

Where does lgc-55 act to increase the length of reversals? Cell specific rescue experiments showed that lgc-55 expression in the RMD (lim-4::lgc-55), RMD or SMD neurons (glr-1::lgc-55) or body wall muscle (myo-3::lgc-55) did not restore normal reversal behavior in lgc-55 mutants (Figure 7A, data not shown). However, lgc-55 expression in the AVB neurons (sra-11::lgc-55) restored normal reversal behavior in lgc-55 mutants. The length of backward runs in response to anterior touch (on average 3.3 ± 0.2 backward body bends), and the number and percentage of long reversals (39.6% short vs 60.4% long) in spontaneous reversal assays were comparable to those observed for wild-type worms (Figure 7). These data indicate that lgc-55 expression in the AVB neurons is required to sustain backward locomotion once a reversal is initiated.

Our data support the hypothesis that tyramine inhibits forward locomotion by activating lgc-55 and hyperpolarizing the AVB forward locomotion command neurons. The lgc-55 dependent inhibition of the forward locomotion program could dramatically shift the balance towards the backward locomotion program, thus explaining our observation that exogenous tyramine induces extremely long backward locomotory runs. To further test this hypothesis, we quantified reversal behavior in the presence of exogenous tyramine. The longest average backwards run for wild-type worms in the presence of exogenous tyramine was approximately 15 body bends, compared to 4 body bends in the absence of exogenous tyramine (Figure 7D). However, exogenous tyramine did not elicit prolonged backward runs in lgc-55 mutant animals (4.0 versus 2.8 backward body bends, respectively). In contrast, lgc-55 mutants that carried a rescuing lgc-55 transgene displayed a dramatic increase in the length of backwards runs in this assay (44 backward body bends), likely due to overexpression of lgc-55. Exogenous tyramine also triggered long backward runs (11 backward body bends) in lgc-55 mutants that express lgc-55 in the AVB neurons using the sra-11::lgc-55 transgene (Figure 7D), but failed to do so in animals that express lgc-55 in the SMD and/or RMD neurons or body wall muscles (data not shown). This result indicates that the effects of exogenous tyramine on backward locomotion are mediated, at least in part, through the activation of lgc-55 in the AVB forward locomotion neurons.

Discussion

Tyramine acts as a classical neurotransmitter in C. elegans

Although tyramine is found in nervous systems from worms to man, it has remained unclear whether tyramine can act as a bona fide neurotransmitter. The data presented further satisfy the six criteria that tyramine must meet to enter the realm of neurotransmitters (Paton, 1958)(Cowan et al., 2001): (1) the presynaptic neuron contains enzymes to make the substance; (2) the substance is released upon activation of the neuron; (3) exogenous application of the substance to the postsynaptic cell mimics normal synaptic transmission; (4) the postsynaptic cell has receptors for the substance; (5) blocking the receptor disrupts the activity of the substance; (6) there are mechanisms to terminate the action of the substance. First, it was previously shown that the C. elegans RIM neurons contain the TDC-1 enzyme that synthesizes tyramine. Second, behavioral analysis of tdc-1 mutants, vesicular monoamine transporter (cat-1) mutants and laser ablation studies indicate that activation of the RIM motor neuron leads to synaptic tyramine release (Alkema et al., 2005). Third, here we show that exogenous tyramine, like endogenous tyramine release, leads to the suppression of head oscillations and stimulates backward locomotion. Fourth, cells that are postsynaptic to the RIM express the tyramine-gated chloride channel, LGC-55. Fifth, genetic disruption of the receptor blocks the tyramine-induced suppression of head oscillations and stimulation of backward locomotion. Sixth, to date no tyramine or octopamine reuptake transporter has been characterized in C. elegans. However, several of the C. elegans sodium neurotransmitter transporter gene family (SNF) (Mullen et al., 2006) have not been characterized. In addition, monoamine-oxidase (MAO) and aryl-alkylamine N-acetyltransferase activities have been detected in nematodes including C. elegans (Isaac et al., 1996) indicating that mechanisms that could terminate tyramine action are present in C. elegans.

Metabotropic tyramine receptors have been identified in a wide variety of animals. Three G-protein coupled receptors that are activated by tyramine, SER-2, TYRA-2 and TYRA-3, have been identified in C. elegans (Rex et al., 2005; Rex and Komuniecki, 2002; Wragg et al., 2007; Tsalik et al., 2003). ser-2, tyra-2 and tyra-3, are expressed in cells that do not receive direct input from the tyraminergic RIMs suggesting that tyramine mainly acts as a neurohormone to activate G-protein coupled tyramine receptors. ser-2, tyra-2 and tyra-3 mutants have no obvious defects in the suppression of head oscillations or reversal behavior. However, ser-2 mutants are partially resistant to the inhibitory effects of tyramine on body movements (J.D. and M.J.A, unpublished observations). LGC-55 provides the first example of an ionotropic-tyramine receptor. Ligand-gated ion channels are thought to have arisen from a common ancestor over 2 billion years ago (Ortells and Lunt, 1995). LGC-55 is found in the same clade as the serotonin-gated chloride channel MOD-1, suggesting that an ancestral anion-channel accumulated mutations in its extracellular domain to acquire sensitivity to tyramine. Have tyramine-gated chloride channels evolved in species other than nematodes? Some observations seem to support this idea. Tyramine increases chloride conductance in the Drosophila Malpighian (renal) tubules (Blumenthal, 2005). Furthermore in rats, tyramine induces strong inhibitory effects on the firing rate of caudate and cortical neurons (Henwood et al., 1979) and can induce hyperpolarization in neurons of the subthalamic nucleus (Zhu et al., 2007) of the rat brain.

Tyramine coordinates distinct motor programs in a C. elegans escape response

The analysis of escape responses in flies, crayfish and goldfish have illuminated how neural networks translate sensory input into a motor output (Korn and Faber, 2005; Edwards et al., 2002; Allen et al., 2006). An animal’s escape response increases its ability to survive predator-prey encounters. One of the main predators of nematodes are the nematophagous fungi (Barron, 1977). These carnivorous fungi are ubiquitous in the soil and decaying organic material and have developed distinctive trapping devices, including constricting hyphal rings, to catch worms (Thorn and Barron, 1984). When a nematode passes through a hyphal ring, gentle friction induces the cells of the ring to inflate and catch the nematode. In C. elegans gentle anterior touch is detected by the ALM and AVM mechanosensory neurons (Figure 8) (Chalfie and Sulston, 1981). The neural wiring diagram and laser ablation studies support a model by which activation of the ALM and AVM neurons leads to the inhibition of the PVC and AVB forward locomotion command neurons and activation of the AVD and AVA backward locomotion command neurons. This causes the animal to move backward away from the stimulus (Chalfie et al., 1985). Subsequently, the RIM is activated through gap junctions with the AVA neurons triggering the release of tyramine (Alkema et al., 2005) and the activation of tyramine-gated chloride channel, LGC-55.

Figure 8. Model: Neural Circuit for Tyraminergic Coordination of C. elegans Escape Response.

Tyraminergic activation of LGC-55 hyperpolarizes neck muscles and the AVB command neurons inducing suppression of head oscillations and sustained backward locomotion in response to touch. Schematic representation of the neural circuit that controls locomotion and head movements. Synaptic connections (triangles) and gap junctions (bars) are as described by White et al. (1986). Sensory neurons shown as triangles, command neurons required for locomotion are shown as hexagons, and motor neurons are depicted as circles. Neck muscles are represented as an oval. lgc-55 expressing cells and neurons are light grey. The tyraminergic motor neuron (RIM) is dark grey. Hypothesized excitatory (+) connections of neurons in this circuit are based on the identification of neurotransmitters, laser ablation and genetic studies cited in this paper. Inhibitory (-) connections important for suppression of head oscillations in response to anterior touch and sustained backward locomotion are based on behavioral, electrophysiological, and expression data described in this paper. See text for details.

In response to anterior touch, lgc-55 mutants, like tyramine deficient animals, fail to suppress head movements and back up less far than the wild type. This indicates that tyramine modulates the output of two independent motor programs, head movements and locomotion. lgc-55 is expressed in neck muscles, the RMD and SMD motorneurons and the AVB forward locomotion command neurons that receive postsynaptic inputs from the RIM. Our studies indicate that tyramine hyperpolarizes neck muscles through activation of LGC-55, thus relaxing the muscle and inhibiting head movements. Since lgc-55 is also expressed in the cholinergic RMD and SMD motor neurons, which regulate head movements, hyperpolarization of these motor neurons may further contribute to the inhibition of head movements. Interestingly, recent patch-clamp studies have demonstrated that the RMD neurons display bistable potentials that depend on extrinsic activation of membrane conductance in the RMD neurons (Mellem et al., 2008). The expression of LGC-55 in RMD neurons suggests that tyraminergic inhibitory synaptic input may be important for the generation of RMD bistability.

LGC-55 expression in the AVB forward locomotion command neurons is required for tyraminergic modulation of reversal behavior. The forward locomotion command neurons make presumptive inhibitory inputs onto the backward locomotion command neurons to coordinate the animal’s locomotion program. Our data indicate that tyraminergic activation of LGC-55 in the AVB shifts the balance of the bistable circuit that controls the direction of locomotion in favor of the backward locomotion program. Tyramine reinforces the backward locomotion program allowing the animal to make a long reversal before reinitiating forward locomotion (Figure 8). Long reversals (3 or more body bends) are usually coupled to an omega turn, in which the head bends ventrally towards the tail (Croll, 1975). Omega turns usually change the direction of locomotion to one directly opposite to the original trajectory (approximately 180°). Short reversals of 1 or 2 body bends lead to a relatively small (40° to 70°, respectively) change in direction of locomotion (Gray et al., 2005; Zhao et al., 2003). Therefore, the suppression of head oscillations coupled to long reversals may allow the animal to engage in a more efficient escape response.

The C. elegans neural escape circuit is reminiscent of the neural escape circuit in flies. In the Drosophila escape response the giant fiber (GF) neurons coordinate distinct motor programs: leg extension and wing depression, which are required for fast flight initiation (Hammond and O’Shea, 2007; Card and Dickinson, 2008). Fly GF interneurons make electrical synapses with the TTMn motorneurons, which control leg jump, and the PSI interneurons, which control wing depression (Tanouye and Wyman, 1980). Additional synaptic connectivity exists between PSI interneurons and the TTMn neurons that presumably contribute to a coordinated motor response (Phelan et al., 1996). Like the worm AVA neurons, the fly GF neurons control two distinct motor programs. Could tyramine play a role in the coordination of these motor programs in the fly escape response? Interestingly, tyramine appears to inhibit flight initiation (Brembs et al., 2007) and flies that have an excess of tyramine or lack the tyramine G-protein coupled receptor, TyRhomo do not jump as far as the wild type in fly escape assays (Zumstein et al., 2004). These striking similarities between worms and flies, suggests that tyramine may act as a conserved coordinator of motor programs in invertebrate escape responses.

Experimental Procedures

Genetic Screen, Mapping and Cloning of LGC-55

All strains were cultured at 22°C on NGM agar plates with the E. coli strain OP50 as a food source. The wild-type strain was Bristol N2. All strains were obtained from the C. elegans Genetics Center (CGC) unless otherwise noted. Wild-type animals were mutagenized with 50 mM EMS (Brenner, 1974). Young adult F2 progeny of approximately 14,000 mutagenized F1 animals were washed twice with water and transferred to 40 mM tyramine plates. After 10 to 20 minutes animals that displayed sustained head or body movements were picked to single plates. Primary isolates were retested on 30 mM tyramine. Twelve mutants were isolated, of which only zf11 and zf53 were sensitive to the inhibitory effects on body movements but resistant to the inhibitory effects on head movements.

We mapped lgc-55(zf11) to LG V using the SNP mapping procedure as previously described (Wicks et al., 2001; Davis et al., 2005). Further three factor mapping placed lgc-55(zf11) to the left of rol-9 close to unc-51. Full-length lgc-55 cDNA sequence was obtained from the expressed sequence tag (EST) clone yk1072c.07. Standard techniques for molecular biology were used. ClustalW alignments were carried out using MacVector software (Accelrys). The lgc-55 deletion allele was obtained from National Bioresource Project and outcrossed four times.

All transgenic strains were obtained by microinjection of plasmid DNA into the germline. At least three independent transgenic lines were obtained and data are from a single representative line. An lgc-55 rescue construct was made by cloning a lgc-55 genomic fragment corresponding to nucleotide (nt) −2663 to +3895 relative to the translation start site into the EcoRV site in yk1072c7. For muscle specific rescue an Acc65I/XhoI fragment containing the full-length lgc-55 cDNA was cloned into pPD95.86 behind the myo-3 promoter. A 2751 bp genomic fragment upstream of the sra-11 translation start site was fused to the full-length lgc-55 cDNA for expression of LGC-55 in the AVB, AIY and AIA (weakly), as well as to GFP for expression analysis. A PstI/Acc65I fragment from the vector pV6 containing the glr-1 promoter was fused to the full-length lgc-55 cDNA for expression of LGC-55 in head neurons including RMD, SMDD, and SMDV. A 3545 bp genomic fragment upstream lim-4 translation start site was fused to the full-length lgc-55 cDNA for expression of LGC-55 in RMD and other head neurons. LGC-55::GFP translational fusion constructs were made by cloning GFP into an engineered AscI restriction in the genomic rescuing construct in the sequence encoding the intracellular loop between TM3 and TM4 (See Figure 2C). Transgenic animals for cell specific rescue experiments were made by co-injecting genomic, LGC-55::GFP, myo-3::LGC-55, sra-11::LGC-55, glr-1::LGC-55 or lim-4::LGC-55 plasmids at 20 ng/μl along with the lin-15 rescuing plasmid pL15EK at 80 ng/μl into lgc-55(tm2913); lin15(n765ts) animals. lgc-55::gfp and lgc-55::mCherry transcriptional fusion constructs were made by cloning a genomic fragment corresponding to nt −2663 to +3859 relative to the translational start site into the following vectors pPD95.70 (GFP) and pPD95.70Cherry (mCherry). The membrane targeting signal sequence corresponding to nt +4 to +48 relative to the lgc-55 translational start site was removed using site directed mutagenesis. GFP and mCherry constructs were microinjected along with the lin-15 rescuing plasmid, pL15EK, at 80 ng/μl into lin15(n765ts) animals.

Cell Identification

Identifications of cells that expressed the lgc-55::mCherry reporter were based on cell body positions, axon morphologies and co-expression with previously described cell specific GFP markers. Strains containing the following fusion genes were used to confirm cell identification: IL1: sEx15005 (y111b2a.8::GFP), AVB: otls123 (sra-11::GFP), RMD, SMDD, SMDV: kyls29 (glr-1::GFP) and nuIs25 (glr-1::GFP), and ALN, SDQ: otls107 (ser-2::GFP). All strains were examined for co-expression of GFP and mCherry by fluorescence microscopy.

Behavioral Assays

All behavioral analysis was performed with young adult animals (24 hours post L4) at room temperature (22–24°C); different genotypes were scored in parallel, with the researcher blinded to the genotype. To quantify tyramine resistance, young adult animals were transferred to agar plates supplemented with 30 mM tyramine and the percentage of immobilized animals was scored every minute for a 20-minute period. Body and head movements were scored separately. Body movement was defined as sustained locomotion for more than 5 seconds, and head movement was defined as sustained lateral swings of the head (anterior to the posterior pharyngeal bulb) only. Wild-type animals paralyzed on 30 mM tyramine within 3–5 minutes. Tyramine plates were prepared by autoclaving 1.7% agar in water, cooling to ~55°C and adding glacial acetic acid to a concentration of 2 mM and tyramine-HCl (Sigma) to a concentration of 30 mM.

To quantify the effect of tyramine on backward locomotion, animals were transferred in a small drop of water to agar plates with or without 30 mM tyramine (tyramine free plates were made as described above, without the addition of tyramine). The drop of liquid was quickly dried with a KimWipe, with care taken not to disturb the animal. Once the spot was dry, the animals were filmed using an Imaging Source DMK 21F04 firewire camera and Astro IIDC software, for 5 minutes or until the animal became paralyzed. The length of each reversal was quantified by counting the number of backward body bends. A backward body bend was defined as half of a sine wave and quantified by counting the number of bends made in the posterior body region during backward runs. The data represent the longest average reversal made within the time interval.

Spontaneous reversal frequency was scored on unseeded NGM agar. Animals were transferred from their culture plate to an unseeded plate and allowed to crawl away from any food that might have been transferred. The animals were then gently transferred without food to another unseeded plate and allowed to recover for 1 minute. After the recovery period the animals were filmed for 3 minutes. The reversal frequency was determined as described in Tsalik and Hobert (2003), and reversal length was scored according to Gray et al. (2005). Animals that crawled to the edge of the plate during filming were discarded. To quantify backward locomotion in response to touch, animals were touched gently with an eyelash posterior to the pharynx and the number of backward body bends made in response to the touch was counted. The suppression of head oscillations was scored as described by Alkema, et al. (2005).

Mosaic Analysis

Strains used for mosaic analysis (QW231 and QW232) were made by coinjecting myo-3::GFP (50ng/ul), lgc-55::mCherry (30 ng/μl), the lgc-55 rescuing construct (20ng/μl) and lin-15 rescuing plasmid pL15EK (80 ng/μl) into lgc-55(tm2913); lin15(n765ts) animals. To facilitate the identification of animals that lost the extrachromosomal array in the AB lineage, we selected multivulva (Muv) animals that expressed myo-3::GFP. Animals that lost the extragenic array the P1 lineage were selected by picking non-Muv animals that did not express myo-3::GFP. Animals that lost the rescuing array in either AB or P1 lineages and non-mosaic controls were tested for the suppression of head oscillations, head paralysis and backward locomotion on exogenous tyramine as described above. Once behavioral assays were completed animals were mounted and examined for the presence of GFP and mCherry using fluorescence microscopy to confirm expression of the array in the appropriate cell type. Animals not expressing the array in all neck muscle or all head neurons were discarded.

Electrophysiology of LGC-55

An EagI/XhoI fragment containing the full length LGC-55 cDNA, including the 5′ and 3′ UTRs was cloned into the EagI/XhoI site of the vector pSGEM for oocyte expression. Capped RNA was prepared using T7 polymerase from Promega. Stage V and VI oocytes from X. laevis were injected with ~50 ng of cRNA. Two electrode voltage clamp experiments were preformed 2–3 days post injection at room temperature (22–24°C). The standard bath solution for dose response and control experiments was ND96: 96 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 5 mM HEPES. For dose response experiments, oocytes were voltage clamped at −60 mV and were subjected to a 10 second application of neurotransmitter (1–1000 μM, in ND96) with 2–3 minute washes between each application. All dose response data were normalized to the mean maximum current observed for tyramine. Data were gathered in 12 independent experiments for each neurotransmitter (totaling 31 eggs), using oocytes from different frogs. Data were consistent between the different batches of oocytes and represent the mean of at least four recordings for each dose of neurotransmitter.

The reversal potential of LGC-55 expressing oocytes was first determined in standard ND96 (as above). For the sodium permeability test, we substituted 96 mM NMDG for NaCl. The Cl− permeability test was preformed in 10% NaCl (9.6 mM NaCl, 86.4 mM sodium gluconate, 2 mM KCl, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 5mM HEPES). All points represent the response to an application of 10 μM TA for 10 s at the indicated holding potentials. Data were normalized to the tyramine current at −60 mV and averaged for 4–5 oocytes per data point. We used 3 M KCl filled electrodes with a resistance between 1–4 MΩ. We used agarose bridges to minimize liquid junction potentials and liquid junction potentials occurring at the tip of the recording electrodes were corrected prior to recording. Currents were recorded using Warner Instrument OC-725 two-electrode voltage clamp (TEVC) and data were acquired with Digidata 1322A using pClamp 9 (Axon Instruments). Normalized dose response data were fit to the Hill equation log(θ/1-θ)= nlog[L]-nlogKA. Reversal potential (Erev) was calculated by determining the x intercept of the linear regression line of each I-V curve and averaged for 4–5 oocytes. Whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings of C. elegans muscle cells were performed as previously described in Francis, et al (2005). In short, recording pipettes were filled with an intracellular solution of 25 mM KCl and 115 mM K-gluconate. Muscle cells were voltage clamped at −60 mV and 200 μM tyramine was pressure applied for 250 ms. The reversal potential of LGC-55 in C. elegans body wall muscle was determined using voltage steps in 20 mV increments. Data were normalized to the Imax for each animal and averaged across 3 to 4 animals. Curve fitting and statistical analyses were performed with Prism version 5.0a for Mac OS X (GraphPad Software).

Supplementary Material

S1. Wild-type animals immobilize on exogenous tyramine.

Dose dependent immobilization of wild-type animals on exogenous tyramine. The percentage of immobilized animals, at varying concentrations of exogenous tyramine, are depicted over a 20 minute period. Each data point represents the average ± SEM for at least five trials totaling at least 50 animals.

S2. Movie of a wild-type animal on plates containing 30 mM tyramine.

Filming began immediately after the animal was placed on the plate and ended shortly after paralysis. Movie was shot at 15 frames per second (fps) and sped up five times.

S3. Movie of a wild-type animal after 5 minutes on plates containing 30 mM tyramine.

Animals paralyze, but can still move in response to mechanical stimulation. Body movements are apparent, but the head and neck remain paralyzed. Movie was filmed at 15 fps.

S4. Movie of a lgc-55 animal after 5 minutes on plates containing 30 mM tyramine.

lgc-55 mutant worms display sustained head movements, while body movements are inhibited. Movie was filmed at 15 fps.

S5. Co-expression of lgc-55::mCherry and glr-1::GFP

Co-expression of lgc-55::mCherry(zfIs4) with glr-1::GFP (kyIs29) (Maricq et al., 1995)and glr-1::GFP(nuIs25) (Hart et al., 1995). Confocal images show co-expression of LGC-55 and GLR-1 in the RMD, SMDD and SMDV. The AVB cell-body, similar to the cell labeled by lgc-55::mCherry, lies on the dorsal side of the animal just anterior to the posterior pharyngeal bulb and has a process that runs ventrally through the amphid commissure (indicated by arrow head) before turning anteriorly and entering the nerve ring (White et al., 1986). It was previously reported that glr-1 is expressed in the AVJ, RIM, AVD and AVB (Hart et al., 1995; Maricq et al., 1995). In the adult animal, we observe glr-1::GFP expression (middle panels) in three cells just anterior to the posterior bulb. The dorsal most cell in this group is slightly ventral compared to the lgc-55::mCherry neuron and has a process that extends anteriorly into the nerve ring, similar to the cell body position and axon morphology of the AVJ. Based on cell body position, axon morphology, which includes a process that runs through the amphid commisure and co-expression with sra-11::GFP (See Figures S6-7), we conclude lgc-55 is expressed in the AVB. Anterior is to the left. Scale bar, 10 μm.

S6. Co-expression of lgc-55::mCherry and sra-11::GFP

Co-expression of lgc-55::mCherry(zfIs4) with sra-11::GFP(otIs123) (Altun-Gultekin et al., 2001). Confocal images show LGC-55 expression in the AVB. Co-expressing cell is on the dorsal side of the animal just anterior to the posterior pharyngeal bulb and has a process the projects ventrally before turning anteriorly and entering the nerve ring in both sets of images. Anterior is to the left. Scale bar, 10 μm.

S7. sra-11::GFP and glr-1::GFP Label Different Subsets of Neurons.

(A) Fluorescence microscopy of animals expressing both glr-1::GFP(kyIs29) and sra-11::GFP(otIs123). Animals expressing both GFP markers were examined to determine the presence expression in the AVB. If sra-11::GFP and glr-1::GFP are both expressed in the AVB, three cells should be visible in animals expressing both transgenes. Here, four cells are visible suggesting that sra-11::GFP and glr-1::GFP label different subsets of neurons. (B) Confocal image of sra-11::GFP(zfEx46). Promoter is the same as sra-11::LGC-55, and shows expression in AVB and AIY similar to sra-11::GFP(otIs123).

S8. Movie of gentle anterior touch response of wild-type animals.

Wild-type animals suppress head oscillations in response to anterior touch.

S9. Movie of gentle anterior touch response of lgc-55(tm2913) mutant animals.

lgc-55 mutant animals fail to suppress head oscillations in response to anterior touch.

S10. LGC-55 expression in the RMD and SMD neurons or neck muscles restores sensitivity to exogenous tyramine.

Quantification of head movements of tissue specific rescue lines on 30 mM tyramine. Expression of lgc-55 in muscle (myo-3::LGC-55), RMD and SMD (glr-1::LGC-55) restores sensitivity to exogenous tyramine. Animals expressing lgc-55 in AVB (sra-11::LGC-55) and RMD alone (lim-4::LGC-55) are resistant to exogenous tyramine.

S11. lgc-55 Mutants Have Defects in Reversal Behavior.

Distribution of number of backward body bends in response to anterior touch of wild type (n= 317), tdc-1(n3420) (n=139), lgc-55(tm2913) (n=257), lgc-55 rescue [lgc-55(tm2913); zfEx2, (n=204)], sra-11::LGC-55 [lgc-55(tm2913); zfEx37, (n=190)], lim-4::LGC-55 [lgc-55(tm2913); zfEx44, (n=108)], glr-1::LGC-55 [lgc-55(tm2913); zfEx42, (n=133)], and myo-3::LGC-55 [lgc-55(tm2913); zfEx31, (n=157)] animals. See also Figure 7A.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Andrew Fire for GFP vectors, Yuji Kohara for cDNA clones, the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center (CGC) for worm strains, the National Bioresource Project for the lgc-55 deletion mutant, Jennifer Ziegenfuss for help with the genetic screen, Bill Kobertz, Steven Gage and Karen Mruk for help with the Xenopus Oocyte experiments, David Hall and Zeynep Altun for help with cell identification, Villu Maricq for glr-1 promoter constructs, Niels Ringstad, Namiko Abe and Bob Horvitz for sharing unpublished results, Vivian Budnik and Scott Waddell for critically reading the manuscript. This research was supported by a grant from the Worcester Foundation (M.J.A.) and grant GM084491 from the National Institute of Health (M.J.A.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alkema MJ, Hunter-Ensor M, Ringstad N, Horvitz HR. Tyramine Functions independently of octopamine in the Caenorhabditis elegans nervous system. Neuron. 2005;46:247–260. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen MJ, Godenschwege TA, Tanouye MA, Phelan P. Making an escape: development and function of the Drosophila giant fibre system. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2006;17:31–41. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2005.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altun-Gultekin Z, Andachi Y, Tsalik EL, Pilgrim D, Kohara Y, Hobert O. A regulatory cascade of three homeobox genes, ceh-10, ttx-3 and ceh-23, controls cell fate specification of a defined interneuron class in C. elegans. Development. 2001;128:1951–1969. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.11.1951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bamber BA, Beg AA, Twyman RE, Jorgensen EM. The Caenorhabditis elegans unc-49 locus encodes multiple subunits of a heteromultimeric GABA receptor. J Neurosci. 1999;19:5348–5359. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-13-05348.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barron GL. The Nematode-Destroying Fungi Topics in Mycobiology Canadian Biological Publications. 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Betz H. Ligand-gated ion channels in the brain: the amino acid receptor superfamily. Neuron. 1990;5:383–392. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90077-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blenau W, Balfanz S, Baumann A. Amtyr1: characterization of a gene from honeybee (Apis mellifera) brain encoding a functional tyramine receptor. J Neurochem. 2000;74:900–908. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0740900.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenthal EM. Modulation of tyramine signaling by osmolality in an insect secretory epithelium. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2005;289:C1261–7. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00026.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borowsky B, Adham N, Jones KA, Raddatz R, Artymyshyn R, Ogozalek KL, Durkin MM, Lakhlani PP, Bonini JA, Pathirana S, Boyle N, Pu X, Kouranova E, Lichtblau H, Ochoa FY, Branchek TA, Gerald C. Trace amines: identification of a family of mammalian G protein-coupled receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:8966–8971. doi: 10.1073/pnas.151105198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brembs B, Christiansen F, Pfluger HJ, Duch C. Flight initiation and maintenance deficits in flies with genetically altered biogenic amine levels. J Neurosci. 2007;27:11122–11131. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2704-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner S. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1974;77:71–94. doi: 10.1093/genetics/77.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Card G, Dickinson M. Performance trade-offs in the flight initiation of Drosophila. J Exp Biol. 2008;211:341–353. doi: 10.1242/jeb.012682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalfie M, Sulston J. Developmental genetics of the mechanosensory neurons of Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 1981;82:358–370. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(81)90459-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalfie M, Sulston JE, White JG, Southgate E, Thomson JN, Brenner S. The neural circuit for touch sensitivity in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Neurosci. 1985;5:956–964. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.05-04-00956.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalfie M, Tu Y, Euskirchen G, Ward WW, Prasher DC. Green fluorescent protein as a marker for gene expression. Science. 1994;263:802–805. doi: 10.1126/science.8303295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chronis N, Zimmer M, Bargmann CI. Microfluidics for in vivo imaging of neuronal and behavioral activity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat Methods. 2007;4:727–731. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole SH, Carney GE, McClung CA, Willard SS, Taylor BJ, Hirsh J. Two functional but noncomplementing Drosophila tyrosine decarboxylase genes: distinct roles for neural tyramine and octopamine in female fertility. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:14948–14955. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414197200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan WM, Südhof TC, Stevens CF. Synapses Johns Hopkins University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Croll NA. Integrated behavior in the feeding phase of Ceanorhabditis elegans (Nematoda) J Zool Lond. 1975;176:159–176. [Google Scholar]

- Davis MW, Hammarlund M, Harrach T, Hullett P, Olsen S, Jorgensen EM. Rapid single nucleotide polymorphism mapping in C. elegans. BMC Genomics. 2005;6:118. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-6-118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards DH, Yeh SR, Musolf BE, Antonsen BL, Krasne FB. Metamodulation of the crayfish escape circuit. Brain Behav Evol. 2002;60:360–369. doi: 10.1159/000067789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis MM, Maricq AV. Electrophysiological analysis of neuronal and muscle function in C. elegans. Methods Mol Biol. 2006;351:175–192. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-151-7:175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray JM, Hill JJ, Bargmann CI. A circuit for navigation in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:3184–3191. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409009101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green WN, Wanamaker CP. The role of the cystine loop in acetylcholine receptor assembly. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:20945–20953. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.33.20945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grutter T, de Carvalho LP, Dufresne V, Taly A, Edelstein SJ, Changeux JP. Molecular tuning of fast gating in pentameric ligand-gated ion channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:18207–18212. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509024102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall D, Altun ZF. C. elegans. Atlas Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hammond S, O’Shea M. Escape flight initiation in the fly. J Comp Physiol A Neuroethol Sens Neural Behav Physiol. 2007;193:471–476. doi: 10.1007/s00359-006-0203-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart AC, Sims S, Kaplan JM. Synaptic code for sensory modalities revealed by C. elegans GLR-1 glutamate receptor. Nature. 1995;378:82–85. doi: 10.1038/378082a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henwood RW, Boulton AA, Phillis JW. Iontophoretic studies of some trace amines in the mammalian CNS. Brain Res. 1979;164:347–351. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(79)90035-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaac RE, MacGregor D, Coates D. Metabolism and inactivation of neurotransmitters in nematodes. Parasitology. 1996;113(Suppl):S157–73. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000077957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones AK, Sattelle DB. The cys-loop ligand-gated ion channel gene superfamily of the nematode, Caenorhabditis elegans. Invert Neurosci. 2008;8:41–47. doi: 10.1007/s10158-008-0068-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlin A, Akabas MH. Toward a structural basis for the function of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and their cousins. Neuron. 1995;15:1231–1244. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz PS, Getting PA, Frost WN. Dynamic neuromodulation of synaptic strength intrinsic to a central pattern generator circuit. Nature. 1994;367:729–731. doi: 10.1038/367729a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korn H, Faber DS. The Mauthner cell half a century later: a neurobiological model for decision-making? Neuron. 2005;47:13–28. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marder E, Bucher D. Central pattern generators and the control of rhythmic movements. Curr Biol. 2001;11:R986–96. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00581-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maricq AV, Peckol E, Driscoll M, Bargmann CI. Mechanosensory signalling in C. elegans mediated by the GLR-1 glutamate receptor. Nature. 1995;378:78–81. doi: 10.1038/378078a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntire SL, Jorgensen E, Kaplan J, Horvitz HR. The GABAergic nervous system of Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 1993;364:337–341. doi: 10.1038/364337a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellem JE, Brockie PJ, Madsen DM, Maricq AV. Action potentials contribute to neuronal signaling in C. elegans. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:865–867. doi: 10.1038/nn.2131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller GM, Verrico CD, Jassen A, Konar M, Yang H, Panas H, Bahn M, Johnson R, Madras BK. Primate trace amine receptor 1 modulation by the dopamine transporter. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;313:983–994. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.084459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monastirioti M, Linn CE, Jr, White K. Characterization of Drosophila tyramine beta-hydroxylase gene and isolation of mutant flies lacking octopamine. J Neurosci. 1996;16:3900–3911. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-12-03900.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullen GP, Mathews EA, Saxena P, Fields SD, McManus JR, Moulder G, Barstead RJ, Quick MW, Rand JB. The Caenorhabditis elegans snf-11 gene encodes a sodium-dependent GABA transporter required for clearance of synaptic GABA. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:3021–3030. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-02-0155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nusbaum MP, Beenhakker MP. A small-systems approach to motor pattern generation. Nature. 2002;417:343–350. doi: 10.1038/417343a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohta H, Utsumi T, Ozoe Y. B96Bom encodes a Bombyx mori tyramine receptor negatively coupled to adenylate cyclase. Insect Mol Biol. 2003;12:217–223. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2583.2003.00404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okkema PG, Harrison SW, Plunger V, Aryana A, Fire A. Sequence requirements for myosin gene expression and regulation in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1993;135:385–404. doi: 10.1093/genetics/135.2.385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortells MO, Lunt GG. Evolutionary history of the ligand-gated ion-channel superfamily of receptors. Trends Neurosci. 1995;18:121–127. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(95)93887-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paton WD. Central and synaptic transmission in the nervous system; pharmacological aspects. Annu Rev Physiol. 1958;20:431–470. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.20.030158.002243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelan P, Nakagawa M, Wilkin MB, Moffat KG, O’Kane CJ, Davies JA, Bacon JP. Mutations in shaking-B prevent electrical synapse formation in the Drosophila giant fiber system. J Neurosci. 1996;16:1101–1113. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-03-01101.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranganathan R, Cannon SC, Horvitz HR. MOD-1 is a serotonin-gated chloride channel that modulates locomotory behaviour in C. elegans. Nature. 2000;408:470–475. doi: 10.1038/35044083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rex E, Hapiak V, Hobson R, Smith K, Xiao H, Komuniecki R. TYRA-2 (F01E11.5): a Caenorhabditis elegans tyramine receptor expressed in the MC and NSM pharyngeal neurons. J Neurochem. 2005;94:181–191. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rex E, Komuniecki RW. Characterization of a tyramine receptor from Caenorhabditis elegans. J Neurochem. 2002;82:1352–1359. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roeder T, Seifert M, Kahler C, Gewecke M. Tyramine and octopamine: antagonistic modulators of behavior and metabolism. Arch Insect Biochem Physiol. 2003;54:1–13. doi: 10.1002/arch.10102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagasti A, Hobert O, Troemel ER, Ruvkun G, Bargmann CI. Alternative olfactory neuron fates are specified by the LIM homeobox gene lim-4. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1794–1806. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.14.1794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saudou F, Amlaiky N, Plassat JL, Borrelli E, Hen R. Cloning and characterization of a Drosophila tyramine receptor. Embo J. 1990;9:3611–3617. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07572.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaner NC, Campbell RE, Steinbach PA, Giepmans BN, Palmer AE, Tsien RY. Improved monomeric red, orange and yellow fluorescent proteins derived from Discosoma sp. red fluorescent protein. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:1567–1572. doi: 10.1038/nbt1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanouye MA, Wyman RJ. Motor outputs of giant nerve fiber in Drosophila. J Neurophysiol. 1980;44:405–421. doi: 10.1152/jn.1980.44.2.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorn RG, Barron GL. Carnivorous Mushrooms. Science. 1984;224:76–78. doi: 10.1126/science.224.4644.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsalik EL, Niacaris T, Wenick AS, Pau K, Avery L, Hobert O. LIM homeobox gene-dependent expression of biogenic amine receptors in restricted regions of the C. elegans nervous system. Dev Biol. 2003;263:81–102. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(03)00447-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber W. Ion currents of Xenopus laevis oocytes: state of the art. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1421:213–233. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(99)00135-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White JG, Southgate E, Thomson JN, Brenner S. The structure of the of the nervous system of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1986;314:1–340. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1986.0056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wicks SR, Yeh RT, Gish WR, Waterston RH, Plasterk RH. Rapid gene mapping in Caenorhabditis elegans using a high density polymorphism map. Nat Genet. 2001;28:160–164. doi: 10.1038/88878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wragg RT, Hapiak V, Miller SB, Harris GP, Gray J, Komuniecki PR, Komuniecki RW. Tyramine and octopamine independently inhibit serotonin-stimulated aversive behaviors in Caenorhabditis elegans through two novel amine receptors. J Neurosci. 2007;27:13402–13412. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3495-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao B, Khare P, Feldman L, Dent JA. Reversal frequency in Caenorhabditis elegans represents an integrated response to the state of the animal and its environment. J Neurosci. 2003;23:5319–5328. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-12-05319.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Y, Brockie PJ, Mellem JE, Madsen DM, Maricq AV. Neuronal control of locomotion in C. elegans is modified by a dominant mutation in the GLR-1 ionotropic glutamate receptor. Neuron. 1999;24:347–361. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80849-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu ZT, Munhall AC, Johnson SW. Tyramine excites rat subthalamic neurons in vitro by a dopamine-dependent mechanism. Neuropharmacology. 2007;52:1169–1178. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zumstein N, Forman O, Nongthomba U, Sparrow JC, Elliott CJ. Distance and force production during jumping in wild-type and mutant Drosophila melanogaster. J Exp Biol. 2004;207:3515–3522. doi: 10.1242/jeb.01181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

S1. Wild-type animals immobilize on exogenous tyramine.

Dose dependent immobilization of wild-type animals on exogenous tyramine. The percentage of immobilized animals, at varying concentrations of exogenous tyramine, are depicted over a 20 minute period. Each data point represents the average ± SEM for at least five trials totaling at least 50 animals.

S2. Movie of a wild-type animal on plates containing 30 mM tyramine.

Filming began immediately after the animal was placed on the plate and ended shortly after paralysis. Movie was shot at 15 frames per second (fps) and sped up five times.

S3. Movie of a wild-type animal after 5 minutes on plates containing 30 mM tyramine.

Animals paralyze, but can still move in response to mechanical stimulation. Body movements are apparent, but the head and neck remain paralyzed. Movie was filmed at 15 fps.

S4. Movie of a lgc-55 animal after 5 minutes on plates containing 30 mM tyramine.

lgc-55 mutant worms display sustained head movements, while body movements are inhibited. Movie was filmed at 15 fps.

S5. Co-expression of lgc-55::mCherry and glr-1::GFP