Abstract

The T-box gene eomesodermin (eomes) has been implicated in mesoderm specification and patterning in both zebrafish and frog. Here, we describe an additional function for eomes in the control of morphogenesis. Epiboly, the spreading and thinning of an epithelial cell sheet, is a central component of gastrulation in many species; however, despite its importance, little is known about its molecular control. Here, we show that repression of eomes function in the zebrafish embryo dramatically inhibits epiboly movements. We also show that eomes regulates the expression of a zygotic homeobox transcription factor mtx2. Gene knockdown of mtx2 using antisense morpholino oligonucleotides, likewise, leads to an inhibition of epiboly; moreover, we show that knockdown of mtx2 function in the extraembryonic yolk syncytial layer only is sufficient to cause epiboly defects. Thus, we have identified two components in a molecular pathway controlling epiboly and show that interactions between deep layer cells of the embryo proper and extraembryonic tissues contribute in a coordinated manner to different aspects of epiboly movements.

Keywords: zebrafish, epiboly, radial intercalation, eomesodermin, mtx2

INTRODUCTION

One of the most significant events during development is gastrulation, when cellular rearrangements produce the embryonic germ layers and set the stage for the emergence of the adult body plan. In zebrafish, several different types of cell movements occur during gastrulation, including epiboly (Warga and Kimmel, 1990). Epiboly is the process by which the blastoderm, which initially sits on top of a large yolk ball, thins and spreads downward to engulf the yolk by the end of gastrulation. Epiboly can be divided into two phases: initiation, which is driven by radial intercalation, and progression, which leads to closure of the blastopore (Strahle and Jesuthasan, 1993). Radial intercalation occurs from the sphere stage (4 hours postfertilization, hpf) to the dome stage (4.3 hpf), when cells move radially toward the surface of the blastoderm to take up more superficial positions, while at the same time the yolk cell domes toward the animal pole (Warga and Kimmel, 1990). The result of these changes is that the blastoderm thins and its surface area increases, which allows the vegetal spread of the blastoderm to proceed.

Although epiboly is a common cell movement during gastrulation in several species (reviewed in Kane and Adams, 2002), we know little about its molecular control. We do not know what initiates radial intercalation and the concomitant doming of the yolk and what sort of changes in adhesion molecules and cytoskeletal components occur in cells during this process. How epiboly is coordinated between the different cell layers of the embryo is also not well understood. Only a single epiboly mutant, called half-baked (hab), was isolated from screens for zygotic mutants in zebrafish (Kane et al., 1996; Kane and Adams, 2002), although recently, several epiboly mutants were isolated in a screen for maternal effect mutants (Wagner et al., 2004).

In previous work, we described the role of the maternal T-box transcription factor eomesodermin (eomes) in the induction of a subset of dorsal organizer genes (Bruce et al., 2003). Here, we describe an additional function for eomes in the control of early cell movements by showing that over-expression of an eomes repressor construct inhibits the initiation of epiboly. We also show that eomes regulates the expression of the zygotic homeobox transcription factor mtx2. Reduction of mtx2 function using antisense morpholino oligonucleotides leads to disruptions in the progression of epiboly. These findings provide new insights into the molecular control of this critical cell movement and are consistent with work in several species demonstrating the importance of T-box genes in the control of morphogenesis (for recent review, see Showell et al., 2004). In addition, work in the frog and mouse has implicated Eomes in the control of early morphogenetic movements, suggesting that this may represent an evolutionarily conserved function of Eomes (Ryan et al., 1996; Russ et al., 2000). Despite evidence for a conserved role for Eomes in morphogenesis, this work is the first to implicate Eomes in epiboly.

RESULTS

Overexpression of the Repressor Construct eomes-eng Inhibits Epiboly

We wished to investigate the possible effects on development stemming from a general knockdown of Eomes function, but, as shown previously in Bruce et al., the presence of maternal Eomes protein precluded the successful use of eomes morpholinos (Bruce et al., 2003). Instead, we made use of our finding that eomes functions as a transcriptional activator in the early embryo, and we injected eomes-eng RNA, encoding a repressor construct consisting of the eomes DNA binding domain fused to the Engrailed transcriptional repressor domain, into early embryos (Bruce et al., 2003). Although there are caveats to using a repressor construct, this approach has proven quite successful in the study of T-box gene function and such constructs have been shown to recapitulate specific mutant phenotypes (for example, Conlon et al., 1996, 2001; Tada and Smith, 2001; Mullen et al., 2002).

Previously, we described the consequences of injecting eomes-eng into just a subset of cells in the early embryo (Bruce et al., 2003). Specifically, we showed that expression of this construct in cells on the dorsal side of the embryo in the organizer leads to an inhibition of expression of some organizer genes, including goosecoid (gsc) and floating head (flh). We now describe our finding that when eomes-eng was overexpressed more globally in early embryos, defects in epiboly were observed, indicating that eomes may have an additional function in early cell movements.

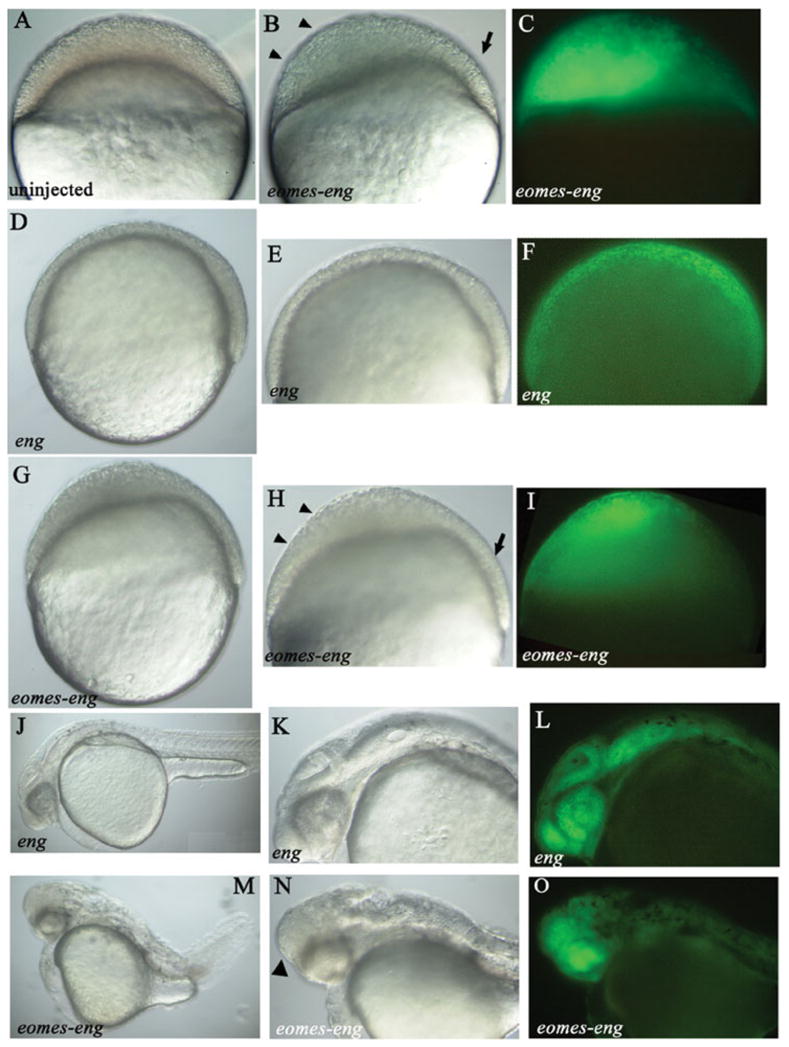

In embryos coinjected with repressor eomes-eng RNA and, as a tracer, gfp RNA, portions of the blastoderm failed to thin (Fig. 1, compare B,G with A,D). As thinning of the blastoderm at this stage in development is the result of radial intercalation (Warga and Kimmel, 1990), we infer that the defects we observe in eomes-eng–injected embryos are the result of inhibiting radial intercalation. The reduction in intercalation was limited to regions of green fluorescent protein (GFP) expression, suggesting a cell-autonomous defect (Fig. 1, compare I with F). In contrast, cells that did not express GFP appeared to undergo radial intercalation normally (arrow, Fig. 1B,H). In control-injected embryos, GFP-expressing cells became evenly distributed in the blastoderm during epiboly (Fig. 1F), whereas GFP-expressing cells in eomes-eng–injected embryos did not (Fig. 1I), which further supports the conclusion that intercalation is impaired. The defect was apparent very early in development, by dome stage, suggesting that injected embryos were unable to initiate radial intercalation. This phenotype was seen in 92% (165 of 180) of eomes-eng–injected embryos, was never seen in embryos injected with RNA encoding the engrailed repressor domain alone (0 of 36, Fig. 1D–F), and rarely was seen in uninjected embryos (3%, 4 of 123).

Fig. 1.

eomes-eng inhibits epiboly. A–O: All views lateral. J–O: anterior toward the left. Construct injected, if any, is indicated in the bottom left corner. A–C: Embryos at 30% epiboly (4.7 hours postfertilization [hpf]), (D–I) embryos at 60% epiboly (6.5 hpf). A: Uninjected control. B: Embryo injected with gfp and eomes-eng RNA. Arrowheads indicate the region of the blastoderm that has failed to thin, and the arrow indicates the normal region of the blastoderm. C: Same embryo as in B showing green fluorescent protein (GFP) fluorescence. The region indicated by the arrowheads in B is where most of the GFP expression is located. D: Control embryo injected with gfp and eng RNA. E: Higher power view of embryo in D. F: Same embryo as in E, showing that GFP fluorescence is distributed throughout the blastoderm. GFP-positive cells are intermingled with unlabeled cells. G: Embryo injected with gfp and eomes-eng RNA. H: Higher power view of embryo in G. Arrowheads indicate region of the blastoderm that has failed to thin, and the arrow indicates the normal region of the blastoderm. I: Same embryo as in H, showing GFP fluorescence. The region indicated by the arrowheads in H is where most of the GFP expression is located. J–O: Embryos at 1 day postfertilization. J: Control embryo injected with gfp and eng RNA. K: Higher magnification of J, showing the head region. L: Same embryo as in K, showing evenly distributed GFP fluorescence. M: Embryo injected with gfp and eomes-eng RNA. N: Higher magnification of M, showing abnormal head region. O: Same embryo as in N showing GFP fluorescence concentrated in the anterior portion of the head.

The phenotypes of eomes-eng–injected embryos at 1 day postfertilization (dpf) included head and trunk defects, which presumably were the result of abnormal gastrulation movements, as a consequence of impaired epiboly. The most common defects in embryos were shortened axes and twisted tails (52%, 55 of 106; Fig. 1M). Twisted tails were observed at the level of the anus (the posterior end of the yolk extension), which marks the closure point during epiboly. This finding suggests that closure over the yolk during gastrulation was abnormal. In some cases, cells expressing eomes-eng remained at the animal pole during epiboly and, thus, ended up in the head at 1 dpf (24%, 10 of 42; Fig. 1N,O). In addition, axial clefts were sometimes observed (11%, 10/92); these are a hallmark of delayed epiboly (Lunde et al., 2004; Wagner et al., 2004).

We performed several experiments to control for potential nonspecific effects of the repressor construct. We previously performed dose–response experiments and demonstrated that the defects caused by eomes-eng can be rescued by coinjection of eomes RNA (Bruce et al., 2003). In addition, we made an equivalent construct using the T-box domain of another T-box gene, no tail, which does not yield the same phenotypes as eomes-eng when injected into embryos (Bruce et al., 2003).

Here, we examined overall cell morphology to ensure that the observed defects were not the result of nonspecific toxicity. To outline cell shapes, we injected a mixture of RNA encoding both cytoplasmic and membrane bound forms of GFP, alone or in combination with eomes-eng (Supplementary Figure S1A,B, which can be viewed at http://www.interscience.wiley.com/jpages/1058-8388/suppmat; Ulrich et al., 2003). We saw no obvious differences in cell morphology in eomes-eng–injected embryos when compared with control embryos. We also examined the microtubule cytoskeleton of blastoderm cells by immunostaining with anti-tubulin antibody (Supplementary Figure S1C,D) and again saw no dramatic changes in eomes-eng–injected embryos that would be indicative of sick or damaged cells.

Eomes Protein Distribution Correlates With a Function in Epiboly

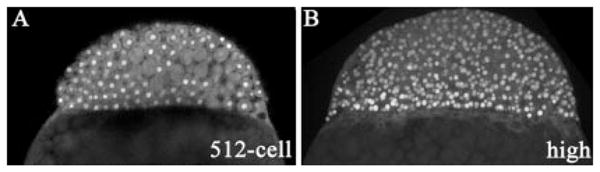

Eomes is expressed at the right time and place to mediate radial intercalation and epiboly. Using a polyclonal antibody that we generated, we previously described the protein expression pattern at the sphere stage (4 hpf), when zygotic genes involved in organizer formation and function are first expressed (Bruce et al., 2003). At this time, Eomes is confined to nuclei on the dorsal side of the embryo. However, Eomes has an earlier pattern of protein expression that is shown in Figure 2. Around the midblastula transition (2.75 hpf), Eomes protein was detected in nuclei throughout the blastoderm (Fig. 2A). This pattern persisted through the high stage at 3.3 hpf (Fig. 2B). Thus, Eomes is present in the nuclei of all embryonic cells, at the time when those cells first become motile (Kane and Kimmel, 1993), and just before the start of radial intercalation.

Fig. 2.

Eomes is expressed throughout the blastoderm at early blastula stages. Images are single scans from a confocal z-series of embryos shown in lateral view and stained with the anti-Eomes antibody. A: Embryo at 512-cell stage (2.75 hours postfertilization [hpf]). Nuclear staining can be seen throughout the blastoderm, although not all nuclei are in the plane of view. B: Embryo at the high stage (3.3 hpf). Protein expression can be seen in nuclei throughout the blastoderm.

Regional Patterning Is Normal in eomes-eng–Injected Embryos

As we previously showed that regional overexpression of eomes-eng in the organizer leads to reduced expression of the organizer genes gsc and flh (Bruce et al., 2003), we investigated whether the cell movement defects we observed when eomes-eng was overexpressed globally resulted from abnormal dorsal–ventral patterning. We examined the expression of the organizer markers gsc and flh at the shield stage and found that it was generally unaffected. Of embryos injected with eomes-eng, 35% (6 of 17) showed a slight reduction in gsc expression, whereas uninjected embryos (37 of 37) and eng-injected (10 of 10) embryos expressed gsc normally. flh was expressed normally in 16 of 18 (89%) embryos examined, whereas slightly patchier expression was observed in 2 embryos. Expression was normal in uninjected embryos (22 of 22). Thus, the cell movement defects caused by eomes-eng do not seem to be the result of defects in the expression of dorsal–ventral patterning genes.

Eomes protein is also expressed in a subset of cells in the enveloping layer, an extraembryonic tissue, which comprises the outermost layer of the blastoderm and produces a transient epithelium (Kimmel et al., 1995; Bruce et al., 2003). To determine whether the enveloping layer was disrupted in eomes-eng–injected embryos, we examined the expression of keratin4, which is expressed exclusively in this cell layer (Thisse et al., 2001). We found that keratin4 was expressed normally in uninjected control embryos (95 of 95) and was normal in 98% (54 of 55) of eomes-eng–injected embryos, suggesting that the enveloping layer was unaffected.

eomes Regulates Expression of mtx2, a Member of the Mix/Bix Gene Family

As an initial strategy to identify downstream target genes of eomes, we took a candidate gene approach. In frogs, the T-box genes Eomes and VegT have been shown to regulate the expression of members of the Mix/Bix family of homeobox containing transcription factors (Ryan et al., 1996; Lemaire et al., 1998; Tada et al., 1998; Casey et al., 1999). In addition, the mouse Eomes gene appears to directly regulate the Mix/Bix gene Mixl1 (Russ et al., 2000; Sahr et al., 2002). These findings, suggesting a conserved interaction between T-box genes and Mix/Bix genes, lead us to investigate whether Eomes regulated Mix/Bix genes in zebrafish.

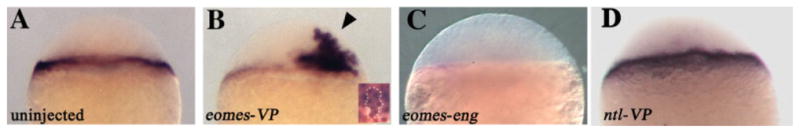

We examined expression of three Mix/Bix genes identified in the zebrafish as bon, mtx1, and mtx2 (Alexander and Stainier, 1999; Hirata et al., 2000; Kikuchi et al., 2000). Although the functions of mtx1 and mtx2 were unknown, their expression patterns partially overlapped with eomes; therefore, we examined whether eomes could activate the expression of either gene. Overexpression of eomes or eomes-VP (an activator construct, consisting of the eomes DNA binding region fused to the VP16 transcriptional activator domain; Bruce et al., 2003) induced ectopic expression of mtx2 but not mtx1 or bon (Fig. 3B and data not shown). mtx2, a zygotic gene, is expressed in a dynamic pattern that includes expression in marginal cells adjacent to the yolk and in the yolk syncytial layer (YSL; Hirata et al., 2000). The YSL is an extraembryonic structure that forms when marginal cells fuse with the previously anuclear yolk ball around the start of zygotic transcription and, thereby, provides an interface between the embryonic cells and underlying yolk (Kimmel and Law, 1985). Ectopic expression of mtx2 was observed in cells several cell diameters away from the margin into the animal pole region, particularly in embryos injected with eomes-VP (arrowhead, Fig. 3B). Injection of eomes-VP resulted in ectopic expression of mtx2 in 76% of embryos (32 of 42), whereas injection of eomes resulted in ectopic expression in 57% of embryos (13/23).

Fig. 3.

eomes regulates mtx2 expression cell-autonomously. All views are lateral, and all embryos are at sphere stage (4 hours postfertilization [hpf]). Injected construct, if any, is indicated in lower left corner. A: In situ hybridization of mtx2 in an uninjected embryo, showing expression in the marginal cells of the blastoderm and the underlying yolk syncytial layer. B: eomes-VP–injected embryo with ectopic mtx2 expression (arrowhead). Inset shows a portion of the blastoderm of a myc-eomes–injected embryo with Eomes protein expression in the nucleus in brown and mtx2 expression in blue. White outline demarcates a group of cells that coexpress Eomes and ectopic mtx2, indicating a cell-autonomous induction of mtx2 by Eomes. C: Reduced mtx2 expression in an embryo injected with eomes-eng. D: ntl-VP–injected embryo with normal mtx2 expression.

We investigated whether eomes induced mtx2 expression cell-autonomously or non–cell-autonomously by injecting myc-eomes RNA, which produces a myc epitope tagged protein that can be visualized with anti-myc antibody (Bruce et al., 2003). Double labeling with anti-myc antibody and mtx2 in situ hybridization demonstrated that eomes induced mtx2 expression cell autonomously in deep cells of the blastoderm (Fig. 3B, inset).

Pursuing this connection further, we found that injection of the repressor construct eomes-eng led to a reduction in mtx2 expression in 78% of embryos (31 of 40), indicating a tight regulation of mtx2 expression by eomes (Fig. 3C). The embryos shown in Figure 3B,C received injections into a single blastomere at the eight-cell stage. We also observed reduced mtx2 expression when eomes-eng was injected globally into one-cell stage embryos (data not shown). In contrast we found that eomes-eng had no effect upon the expression of bon, a Mix/Bix gene that plays an important role in endoderm specification (Alexander and Stainier, 1999; Kikuchi et al., 2000). Thus, eomes is capable of specifically regulating the expression of mtx2 in the zebrafish, without affecting other Mix/Bix-type genes.

As a control for the specificity of the effect, we examined mtx2 expression in embryos injected with RNA encoding ntl-VP, an activator construct. ntl is the zebrafish homolog of the T-box gene Brachyury and is expressed in the early embryo (Schulte-Merker et al., 1992). At the sphere stage, expression of mtx2 was normal in uninjected control embryos (43 of 43), as well as in embryos injected with gfp RNA (36 of 36). Expression of mtx2 was also normal in embryos injected with ntl-VP (42/42, Fig. 3D). These results suggest that eomes specifically regulates the expression of mtx2.

mtx2 Is Also Required for Epiboly

As mtx2 is a strictly zygotically expressed gene and is regulated by eomes, we investigated its potential function in epiboly by gene knockdown using two independent antisense morpholinos (Mtx2-MO1 and Mtx2-MO2). The activity of both mtx2 morpholinos was tested as described (see Experimental Procedures section; Oates and Ho, 2002).

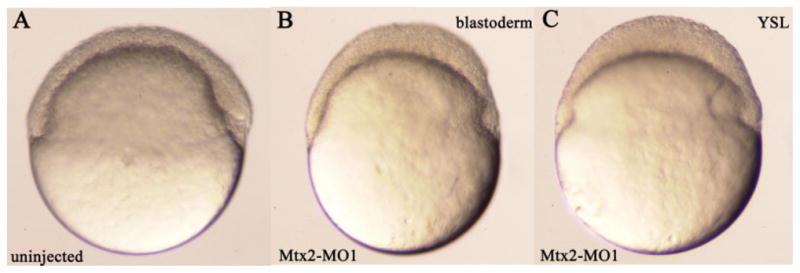

After injection of either morpholino into one-cell stage embryos, epiboly defects were observed, although the initiation of epiboly appeared to occur normally (Fig. 4, compare A and B). The defects were first observed at and subsequent to the shield stage (6 hpf) when the blastoderm margin failed to continue its vegetal movement and as a result the blastoderm did not thin further. We observed identical phenotypes with Mtx2-MO1 and Mtx2-MO2, thus for simplicity, we focused on Mtx2-MO1. Epiboly defects were observed in 96% (115 of 120) of Mtx2-MO1–injected embryos. The majority of embryos injected with Mtx2-MO1 died by mid-epiboly due to the yolk cell bursting. Of interest, yolk cell lysis is also observed in the zebrafish epiboly arrest mutant half-baked (Kane et al., 1996; Kane and Adams, 2002) as well as in the maternal effect epiboly mutant betty boop (Wagner et al., 2004). As we did for eomes-eng, we examined cell morphology by coinjection of morpholinos and gpf RNA and saw no differences from control embryos; similarly, we saw no obvious defects in the microtubule cytoskeleton using an anti-tubulin antibody (data not shown). These data suggest that the morpholino effects are specific and not the consequence of general toxicity.

Fig. 4.

mtx2 morpholinos inhibit epiboly. All views are lateral with dorsal to the right; all embryos are at shield stage (6 hours postfertilization). Injected construct, if any, is indicated in lower left corner. A: Uninjected embryo. B: Embryo injected with Mtx2-MO1 into one cell at the two-cell stage; note that the blastoderm is thickened compared with control. C: Embryo injected with Mtx2-MO1 into the yolk syncytial layer (YSL); note that the blastoderm is thickened compared with control.

As mtx2 is expressed in the YSL as well as in the marginal cells of the blastoderm, we were interested in examining its function there. We injected Mtx2-MO1 into the YSL shortly after its formation and observed defects similar to those seen in embryos injected with Mtx2-MO1 into a single blastomere at the two-cell stage (Fig. 4C). Epiboly defects were observed in 27 of 27 embryos injected with morpholino into the YSL. This finding suggests that mtx2 expression in the YSL is required for normal epiboly. As eomes is not expressed in the YSL, mtx2 expression may be regulated differently in the YSL than in the blastoderm.

We were also interested in trying to rescue the defects caused by eomes-eng by coinjecting mtx2 RNA. If the defects observed in eomes-eng–injected embryos were the result, in part or whole, of repressing mtx2 expression, then we might expect to see a rescue of the epiboly defect. However, we were unable to carry out these experiments for technical reasons. We observed a severe overexpression phenotype, even at low doses, when mtx2 RNA was injected into one-cell stage embryos, thus making it impractical to score for a rescue. In an attempt to overcome this difficulty, we injected mtx2 RNA into the yolk syncytial layer; however, we found that this injection had no effect on eomes-eng–injected embryos (data not shown). This finding suggests that, although expression of mtx2 in the YSL is required for normal epiboly, it may not be sufficient. In summary, mtx2 morpholino-injected embryos had defects in the progression of epiboly and mtx2 morpholinos produce the same defects whether injected into the YSL or the blastoderm.

Regional Patterning Is Normal in mtx2 Morpholino-Injected Embryos

We examined dorsal–ventral patterning in morpholino-injected embryos by examining gsc expression. gsc expression was normal in uninjected embryos (90 of 90) and was present in all Mtx2-MO1–injected embryos (99 of 99), although the domains were slightly disorganized in 52% (52 of 99) of the embryos, consistent with defects in morphogenesis. Expression of flh was observed in 30 of 30 embryos injected with Mtx2-MO1, although the staining was slightly less intense than in control embryos in 13 of 30 embryos. Normal expression was observed in uninjected controls (22 of 22). We also examined the expression of the ventral marker evel (Joly et al., 1993), which was expressed normally in uninjected control embryos (124 of 124) and in 95% (63 of 66) of Mtx2-MO1–injected embryos. Thus, dorsal–ventral patterning was largely unaffected in mtx2 knockdown embryos.

We also examined the expression of the pan mesodermal marker no tail (Schulte-Merker et al., 1992) and found that it was normal in uninjected control embryos (122 of 122) as well as in 91% (91 of 100) of Mtx2-MO1–injected embryos. Similarly, the endodermal marker bon, was expressed normally in both uninjected control embryos (50 of 50) and morpholino-injected embryos (78 of 78). These results suggest that the general specification of endoderm and mesoderm was normal in morpholino-injected embryos.

We also examined the expression of the endodermal marker sox17, specifically in dorsal forerunner cells (Alexander and Stainier, 1999). Expression of sox17 was normal in 99% (68 of 69) of uninjected control embryos and absent in one embryo. No forerunner cell expression of sox17 was detected in 24% (9 of 37) of morpholino-injected embryos. We suspect that this absence of expression was the result of developmental delay rather than a specific effect on the forerunner cells, because, as a result of the epiboly defect, the morpholino-injected embryos were difficult to stage and most lysed by the shield stage, which is when forerunner expression is first detected (Alexander and Stainier, 1999).

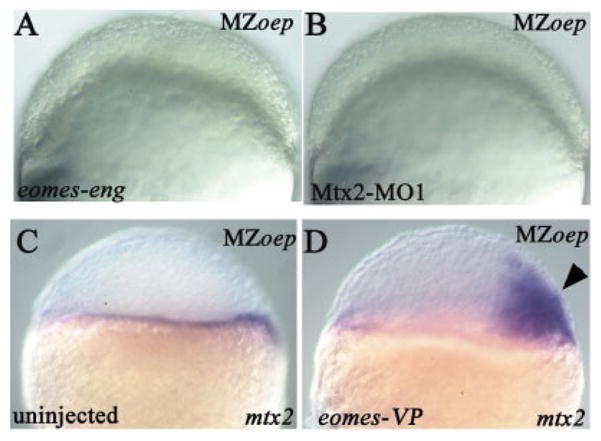

Epiboly Defects Are Nodal-Independent

We next tested whether the effects of eomes-eng and mtx2 morpholinos on cell movements were Nodal-dependent, because induction of organizer genes by eomes overexpression requires Nodal signaling (Bruce et al., 2003). The process of epiboly itself does not depend on Nodal signaling, as early epiboly movements are overtly normal in MZoep embryos (Feldman et al., 2000). MZoep embryos lack of Nodal involvement in epiboly, injection of either eomes-eng or Mtx2-MO1 into MZoep embryos inhibited epiboly in a manner indistinguishable from their effects on wild-type embryos (13 of 13 for eomes-eng–injected embryos and 14 of 14 for Mtx2-MO1–injected embryos; Fig. 5A,B).

Fig. 5.

Epiboly defect is Nodal-independent. All views are lateral; the mutant phenotype is indicated in upper right corner; the injected construct is indicated in lower left corner. A,B: At 50% epiboly (5.25 hours postfertilization [hpf]). C,D: At sphere stage (4 hpf). A: Embryo injected with eomes-eng; the blastoderm has failed to thin. B: Embryo injected with Mtx2-MO1; the blastoderm has failed to thin. C: mtx2 expression in an uninjected embryo. D: Ectopic mtx2 expression (arrowhead) in an eomes-VP–injected (into a single cell at the eight-cell stage) embryo.

Hirata and coworkers demonstrated that mtx2 expression is not regulated by Nodal signaling (Hirata et al., 2000). This finding suggested that regulation of mtx2 by eomes might also be independent of Nodal signaling. To verify that mtx2 expression was unaffected by a loss of maternal and zygotic Nodals, we performed in situ hybridizations on MZoep embryos and found that mtx2 expression was normal (Fig. 5C). Next, we injected an activator construct, eomes-VP (Bruce et al., 2003), into MZoep embryos and found that eomes-VP was still capable of inducing ectopic expression of mtx2 (86%, 37 of 43; Fig. 5D). Therefore, eomes regulates mtx2 through a non-Nodal pathway and the regulation of epiboly by both genes is Nodal-independent.

DISCUSSION

eomes Has a Role in Epiboly

We have shown that eomes is involved in two processes in the developing zebrafish embryo. In prior work, we showed that overexpression of eomes leads to Nodal-dependent ectopic expression of organizer genes and induction of secondary axes, demonstrating a potential role in organizer function (Bruce et al., 2003). Here, we report that overexpression of a repressor construct revealed an additional, Nodal-independent, role for eomes in epiboly. The correct execution of epiboly is essential for gastrulation and, hence, viability of the embryo. Little is known about the genetic control of this process; here, we present evidence that eomes may be required for epiboly.

Eomes protein is expressed in two distinct patterns, which correlate with the two Eomes functions that we have described. One pattern correlates with a role in induction of zygotic organizer gene expression (Bruce et al., 2003), whereas an additional pattern is apparent at earlier stages of development around the midblastula transition, when cells in the zebrafish embryo first become motile (Kane and Kimmel, 1993). At this stage, we observed nuclear localized Eomes throughout the blastoderm. Eomes protein is expressed in the cells that will undergo radial intercalation and epiboly at the time when these cell movements are initiating; thus, Eomes is expressed in the right location and at the correct time to influence the behavior of intercalating cells. Consistent with this expression pattern is the observation that the epiboly defects seen in eomes-eng–injected embryos were first apparent at doming, which suggests that Eomes is required for the initiation of this cell movement. The mechanism by which eomes directs epiboly is unclear but may involve regulation of cell adhesion, which has been proposed to be a common mechanism of T-box function (Ahn et al., 2002). What controls these two different protein expression patterns currently is unknown but, once determined, should provide insight into how the two functions of eomes are coordinated. The two eomes functions might result from interactions with different partner proteins that are expressed in distinct regions of the embryo. Other groups have demonstrated that T-box genes can act synergistically and interact physically with other transcription factors (Bruneau et al., 2001; Hiroi et al., 2001).

One obvious question is why we did not observe dramatic cell movement defects in our gain-of-function experiments in which eomes was overexpressed in embryos. We did observe abnormal thickenings corresponding to regions of overexpressing cells, which we interpreted as ectopic shields, based on marker gene expression (Bruce et al., 2003). However, these thickened regions may also be indicative of changes in the adhesive properties of the eomes overexpressing cells. It is also possible that cells cannot epibolize to excess, as might be expected in response to eomes overexpression, as they are confined by an outer epithelium called the enveloping layer. Closer examination of the behavior of individual cells in overexpressing embryos may reveal defects that are not apparent at the level of the whole embryo.

In addition, we saw relatively minor effects on the expression of dorsal organizer gene expression in embryos injected globally with eomes-eng, in contrast to the near complete repression of gsc and flh expression that we described in our previous overexpression studies (Bruce et al., 2003). These differences are most easily explained by differences in how the experiments were performed. Here, eomes-eng was injected into the yolk; thus, the RNA was distributed more widely throughout the embryo than in our previous experiments when eomes-eng was injected into a single cell at the eight-cell stage. The lower concentration of eomes-eng in the injected embryos seems a likely explanation for the observed differences in dorsal marker gene expression.

eomes and mtx2 Affect Epiboly in Different Ways

T-box genes have been shown to regulate the expression of Mix/Bix class homeobox genes (Ryan et al., 1996; Lemaire et al., 1998; Tada et al., 1998; Casey et al., 1999). We have shown that in zebrafish overexpression of eomes induces ectopic expression of the Mix/Bix gene mtx2, and, conversely, injection of eomes-eng leads to a reduction in mtx2 expression. Furthermore, injection of mtx2 antisense morpholino oligonucleotides resulted in defects in epiboly, raising the possibility that the regulation of epiboly by eomes occurs in part through mtx2.

We have also shown that eomes can induce mtx2 expression cell-autonomously. This finding may seem surprising given that mtx2 is expressed in only a portion of the early eomes expression domain. However, this result is consistent with other work on T-box gene regulation in zebrafish. For example, Goering et al. showed that the T-box gene ntl regulates expression of different genes in different portions of its expression domain (Goering et al., 2003). Furthermore, they demonstrated that this differential regulation is accomplished by means of interactions between different T-box genes with overlapping expression domains (Goering et al., 2003). It remains to be seen whether eomes interacts with other T-box genes or with other region specific factors to carry out its functions and, further, to be determined is whether the induction of mtx2 is direct or indirect.

The epiboly defects observed in eomes-eng and mtx2 morpholino-injected embryos were not identical. One difference was that defects were apparent earlier in eomes-eng-injected embryos. In eomes-eng–injected embryos, there were regions where the yolk cell did not dome and the blastoderm remained thick, suggesting a failure to initiate radial intercalation. The defects in mtx2 morpholino-injected embryos were first observed around the shield stage, when the blastoderm margin failed to progress vegetally and the blastoderm did not continue to thin. The earlier onset of defects in eomes-eng–injected embryos compared with mtx2 morpholino-injected ones suggests that eomes regulates additional downstream targets, which are responsible for the initiation of radial intercalation.

We also showed that Mtx2-MO1 had the same effect when injected into the YSL as it did when injected into the blastoderm. This finding suggests that mtx2 is required in the YSL for normal epiboly. However, it may not be sufficient for normal epiboly, as injection of mtx2 RNA into the YSL cannot rescue the epiboly defects in eomes-eng–injected embryos. We hypothesize that mtx2 is required both in the blastoderm and in the YSL for normal epiboly. As eomes is not expressed in the YSL, the regulation of mtx2 in the YSL may be different from that in the blastoderm. Eomes may regulate mtx2 expression in the YSL non– cell-autonomously, consistent with our previous work demonstrating that Eomes could induce gsc expression by a non– cell-autonomous mechanism (Bruce et al., 2003). Another alternative is that Eomes might only regulate mtx2 expression in the blastoderm, which could indirectly affect the accumulation of mtx2 in the YSL when it forms by means of the fusion of marginal blastoderm cells with the yolk.

Another difference was the mid-epiboly death, which was a consequence of the yolk cell bursting. This finding was observed in mtx2 morpholino-injected embryos but rarely in eomes-eng–injected embryos. The effect of mtx2-morpholinos may have been more severe due to a more even distribution of morpholinos throughout the embryo than the injected eomes-eng RNA (Nasevicius and Ekker, 2000). In addition, there may be multiple upstream regulators of mtx2 expression, which act in parallel pathways. This scenario is supported by the phenotype of the recently isolated maternal effect mutant betty boop, which is nearly identical to the epiboly defects observed in mtx2 morpholino-injected embryos (Wagner et al., 2004). Thus, there may be lower levels of Mtx2 protein in morpholino-injected embryos than in eomes-eng–injected embryos, leading to a more severe mtx2 reduction-of-function phenotype.

Mechanism of Epiboly

Little is known about the mechanisms that initiate radial intercalation, although the assumption is that doming of the yolk cell provides the motive force (for review, see Kane and Adams, 2002). This explanation has led to the idea that the cells of the embryo are pushed outward when the yolk cell domes rather than actively initiating movement. More is known about the forces involved in the progression of epiboly, which occurs from the dome stage through the end of gastrulation. Here again, evidence points to the importance of the yolk cell. In a related fish species, Fundulus, removal of the blastoderm from the yolk does not prevent epiboly of the YSL, suggesting its independence from the cells of the blastoderm (Trinkaus, 1951; Betchaku and Trinkaus, 1978). However, there is some evidence that the YSL is not the sole force behind epiboly. This evidence comes from analysis of the epiboly mutant half-baked, which has defects in the movements of the deep cells but not of the YSL (Kane and Adams, 2002). This finding indicates that epibolic movements of blastoderm cells are genetically separable from the YSL and that blastoderm cells may not be passive participants in epiboly.

Eomes appears to act directly upon the cells of the blastoderm, which would be consistent with the apparent cell autonomy of the defects in eomes-eng-injected embryos, and if confirmed would represent the first experimental evidence that cells of the embryo actively participate in epiboly. Although eomes can induce mtx2 expression cell autonomously in the blastoderm it might also be involved in regulating mtx2 expression indirectly in the YSL. Perhaps the most likely scenario is that Eomes functions by a combination of both cell-autonomous and non–cell-autonomous mechanisms, not only during organizer formation, as we have previously described (Bruce et al., 2003), but also during the earlier process of epiboly.

Conserved Role for Eomesodermin in Morphogenesis

A conserved evolutionary role for Eomes in orchestrating gastrulation movements is suggested from work in Xenopus and mouse (reviewed in Graham, 2000). Injection of a putative dominant-negative Eomes construct into Xenopus embryos led to the formation of exogastrulae and gastrulation arrest, indicative of abnormal cell movements (Ryan et al., 1996). Aberrant cell movements were also implicated in the gastrulation failure observed in mice lacking Eomes, in which cells fail to migrate into the primitive streak (Russ et al., 2000).

A likely downstream target of murine Eomes is the Mix/Bix gene Mixl1 (Russ et al., 2000). Analysis of the Mixl1 promoter revealed the presence of putative T-box binding sites (Sahr et al., 2002). In addition, analysis of mice homozygous for a null mutation in the Mixl1 gene revealed defects in mesoderm and endoderm morphogenesis during gastrulation and the presence of bifurcated axes (Hart et al., 2002), which are also observed in zebrafish embryos injected with eomes-eng. In both zebrafish and mouse, this function appears to be mediated, at least in part, by downstream target genes that belong to the Mix/Bix family. Together these results point to a conserved role for Eomes in the control of cell movements, although our work is the first to implicate Eomes in epiboly. In mouse and frog, Eomes is not expressed maternally; thus, it will be interesting to determine whether the two described functions of Eomes correlate with either the maternal or zygotic expression of the gene.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Zebrafish

Zebrafish embryos were obtained from natural matings and staged as described (Kimmel et al., 1995). Wild-type strains used included a local pet store strain, *AB and TLF. MZoep mutants were produced from crosses of rescued oepm134/oepm134, which were gifts from M. Halpern and R. Warga.

Whole-Mount In Situ Hybridization

In situ hybridizations were performed as previously described (Bruce et al., 2003). Antisense riboprobes to goosecoid (Stachel et al., 1993), bonnie and clyde (Alexander and Stainier, 1999), evel (Joly et al., 1993), mtx1 and mtx2 (Hirata et al., 2000), floating head (Talbot et al., 1995), sox17 (Alexander and Stainier, 1999), no tail (Schulte-Merker et al., 1994), and keratin4 (Thisse et al., 2001) were synthesized as described.

Expression Constructs

eomes and ntl constructs have been described previously (Bruce et al., 2003).

Antisense Morpholino Oligonucleotides

Two different antisense morpholino oligonucleotides targeted against mtx2 (accession no. AB034246) were obtained from Gene Tools LLC (Philomath, OR), Mtx2-MO1: 5′-CATTGAGTATTTTGCAGCTCTCTTG-3′, and Mtx2-MO2: 5′-TTGCAGAAAATAAGTAAGTCAAGC-3′. To test the specificity of the morpholino, the coding sequence plus a portion of the 5′ untranslated region (including the morpholino target sequence) was cloned in frame into a plasmid containing GFP, to generate mtx2-GFP (Oates and Ho, 2002). Injection of mtx2-GFP RNA resulted in nuclear-localized GFP expression (20 of 20 embryos), whereas coinjection of mtx2-GFP and Mtx2-MO1 led to reduced or undetectable GFP fluorescence in 100% of injected embryos (36 of 36 embryos). Coinjection of Mtx2-MO1 and GFP RNA, which did not contain the morpholino target sequence, had no effect on GFP fluorescence (16 of 16 embryos). The results for Mtx2-MO2 were similar. Embryos injected with mtx2-GFP RNA alone resulted in nuclear GFP expression (8 of 8 embryos), whereas coinjection of mtx2-GFP RNA and Mtx2-MO2 led to reduced or absent GFP expression (22 of 22 embryos). In contrast, coinjection of an unrelated morpholino at the same concentration and mtx2-GFP RNA had no effect on GFP fluorescence (21 of 21 embryos). As similar defects were observed with both morpholinos, we conducted most of our studies with MO1.

Microinjections

Microinjections were performed as described previously either through the chorion at the one- to four-cell stage or into dechorionated embryos (Bruce et al., 2003). Morpholino antisense oligonucleotides were injected into the yolk or into a single cell of one- to four-cell stage embryos at a concentration of 2.5 ng/nl. mtx2-GFP RNA was injected into the yolk of one- to four-cell stage embryos at a concentration of 100 ng/μl. Morpholino concentrations were determined by testing a range of concentrations and selecting the one that did not cause nonspecific defects. Injections of eomes-eng, eng, and eomes-VP, and ntl-VP were performed as described (Bruce et al., 2003).

Antibody Staining and Imaging

Anti-Eomes and anti-myc antibody staining and imaging were performed as described (Bruce et al., 2003). Anti-tubulin antibody staining was performed as described (Topczewski and Solnica-Krezel, 1999).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Holly Dow, Devon Mann, and Becky Beilang for fish care. We thank members of the zebrafish community for generously providing probes. For the mtx constructs we thank Masahiko Hibi. The membrane localized GFP construct was made by David Turner and provided by Richard Harland. The keratin4 probe was obtained from the Zebrafish International Resource Center at the University of Oregon, which is supported by grant P40 RR12546 from the NIH-NCRR. For helpful discussions we thank members of the Ho lab. For comments on the manuscript, we thank Vince Tropepe, and for comments on an earlier version, we thank Andrew Oates. For technical assistance, we thank Sayre Vickers, and for confocal assistance we thank Henry Hong. For generously providing reagents and equipment, we thank Dorothea Godt, Ellie Larsen, Maurice Ringuette, Helen Rodd, Patricia Romans, Locke Rowe, Ulli Tepass, Vince Tropepe, Sue Varmuza, and Rudi Winklbauer. This work was supported by NIH and NSF grants to R.K.H. and University of Toronto Departmental Start-up funds to A.E.E.B.

Grant sponsors: NIH; NSF; University of Toronto Departmental Funds.

Footnotes

The Supplementary Material referred to in this article can be found at http://www.interscience.wiley.com/jpages/1058-8388/suppmat

References

- Ahn DG, Kourakis MJ, Rohde LA, Silver LM, Ho RK. T-box gene tbx5 is essential for formation of the pectoral limb bud. Nature. 2002;417:754–758. doi: 10.1038/nature00814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander J, Stainier DY. A molecular pathway leading to endoderm formation in zebrafish. Curr Biol. 1999;9:1147–1157. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(00)80016-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betchaku T, Trinkaus JP. Contact relations, surface activity and cortical microfilaments of marginal cells of the enveloping layer and of the yolk syncytial and yolk cytoplasmic layers of Fundulus before and during epiboly. J Exp Zoo. 1978;206:381–426. doi: 10.1002/jez.1402060310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce AEE, Howley C, Zhou Y, Vickers SL, Silver LM, King ML, Ho RK. The maternally expressed zebrafish T-box gene, eomesodermin, regulates organizer formation. Development. 2003;130:5503–5517. doi: 10.1242/dev.00763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruneau BG, Nemer G, Schmitt JP, Charron F, Robitaille L, Caron S, Conner DA, Gessler M, Nemer M, Seidman CE, Seidman JG. A murine model of Holt-Oram syndrome defines roles for the T-box transcription factor Tbx5 in cardiogenesis and disease. Cell. 2001;106:709–721. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00493-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey ES, Tada M, Fairclough L, Wylie CL, Heasman J, Smith JC. Bix4 is activated directly by VegT and mediates endoderm formation in Xenopus development. Development. 1999;126:4193–4200. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.19.4193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conlon FL, Sedgwick SG, Weston KM, Smith JC. Inhibition of Xbra transcription activation causes defects in mesodermal patterning and reveals auto-regulation of Xbra in dorsal mesoderm. Development. 1996;122:2427–2435. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.8.2427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conlon FL, Fairclough L, Price BMJ, Casey ES, Smith JC. Determinants of T box protein specificity. Development. 2001;128:3749–3758. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.19.3749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman B, Gates MA, Egan ES, Dougan ST, Rennebeck G, Sirotkin HI, Schier AF, Talbot WS. Zebrafish organizer development and germ-layer formation require nodal-related signals. Nature. 1998;395:181–185. doi: 10.1038/26013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman B, Dougan ST, Schier AF, Talbot WS. Nodal-related signals establish mesendodermal fate and trunk neural identity in zebrafish. Curr Biol. 2000;10:531–534. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00469-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goering LM, Hoshijima K, Hug B, Bisgrove B, Kispert A, Grunwald DJ. An interacting network of T-box genes directs gene expression and fate in the zebrafish mesoderm. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:9410–9415. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1633548100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham A. Mammalian development: new trick for an old dog. Curr Biol. 2000;10:R401–R403. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00503-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart AH, Hartley L, Sourris K, Stadler ES, Li R, Stanley EG, Tam PPL, Elefanty AG, Robb L. Mixl1 is required for axial mesendoderm morphogenesis and patterning in the murine embryo. Development. 2002;129:3597–3608. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.15.3597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirata T, Yamanaka Y, Ryu SL, Shimizu T, Yabe T, Hibi M, Hirano T. Novel mix-family homeobox genes in zebrafish and their differential regulation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;271:603–609. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiroi Y, Kudoh S, Monzen K, Ikeda Y, Yazaki Y, Nagai R, Komuro I. Tbx5 associates with Nkx2-5 and synergistically promotes cardiomyocyte differentiation. Nat Genet. 2001;28:276–280. doi: 10.1038/90123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joly JS, Joly C, Schulte-Merker S, Boulekbache H, Condamine H. The ventral and posterior expression of the zebrafish homeobox gene eve1 is perturbed in dorsalized and mutant embryos. Development. 1993;119:1261–1275. doi: 10.1242/dev.119.4.1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane D, Adams R. Life at the edge: epiboly and involution in the zebrafish. Results Probl Cell Differ. 2002;40:117–135. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-46041-1_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane DA, Kimmel CB. The zebrafish midblastulatransition. Development. 1993;119:447–456. doi: 10.1242/dev.119.2.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane DA, Hammerschmidt M, Mullins MC, Maischein HM, Brand M, van Eeden FJ, Furutani-Seiki M, Granato M, Haffter P, Heisenberg CP, Jiang YJ, Kelsh RN, Odenthal J, Warga RM, Nusslein-Volhard C. The zebrafish epiboly mutants. Development. 1996;123:47–55. doi: 10.1242/dev.123.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi Y, Trinh LA, Reiter JF, Alexander J, Yelon D, Stainier DY. The zebrafish bonnie and clyde gene encodes a Mix family homeodomain protein that regulates the generation of endodermal precursors. Genes Dev. 2000;14:1279–1289. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel CB, Law RD. Cell lineage of zebrafish blastomeres. II. Formation of the yolk syncytial layer. Dev Biol. 1985;108:86–93. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(85)90011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel CB, Ballard WW, Kimmel SR, Ullmann B, Schilling TF. Stages of embryonic development of the zebrafish. Dev Dyn. 1995;203:253–310. doi: 10.1002/aja.1002030302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemaire P, Darras S, Caillol D, Kodjabachian L. A role for the vegetally expressed Xenopus gene Mix.1 in endoderm formation and in the restriction of mesoderm to the marginal zone. Development. 1998;125:2371–2380. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.13.2371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunde K, Belting H-G, Driever W. Zebrafish pou5f1/pou2, homolog of mammalian oct4 functions in the endoderm specification cascade. Curr Biol. 2004;14:48–55. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullen AC, Hutchins AS, High FA, Lee HW, Sykes KJ, Chodosh LA, Reiner SL. Hlx is induced by and genetically interacts with T-bet to promote heritable TH1 gene induction. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:652–658. doi: 10.1038/ni807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasevicius A, Ekker SC. Effective targeted gene ’knockdown’ in zebrafish. Nat Genet. 2000;26:216–220. doi: 10.1038/79951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oates AC, Ho RK. Hairy/E(spl)-related (Her) genes are central components of the segmentation oscillator and display redundancy with the Delta/Notch signaling pathway in the formation of anterior segmental boundaries in the zebrafish. Development. 2002;129:2929–2946. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.12.2929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russ AP, Wattler S, Colledge WH, Aparicio SA, Carlton MB, Pearce JJ, Barton SC, Surani MA, Ryan K, Nehls MC, Wilson V, Evans MJ. Eomesodermin is required for mouse trophoblast development and mesoderm formation. Nature. 2000;404:95–99. doi: 10.1038/35003601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan K, Garrett N, Mitchell A, Gurdon JB. Eomesodermin, a key early gene in Xenopus mesoderm differentiation. Cell. 1996;87:989–1000. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81794-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahr K, Campos Dias D, Sanchez R, Chen D, Chen SW, Gudas LJ, Baron MH. Structure, upstream promoter region, and functional domains of a mouse and human Mix paired-like homeobox gene. Gene. 2002;291:135–147. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(02)00590-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulte-Merker S, Ho RK, Herrmann BG, Nusslein-Volhard C. The protein product of the zebrafish homologue of the mouse T gene is expressed in nuclei of the germ ring and the notochord of the early embryo. Development. 1992;116:1021–1032. doi: 10.1242/dev.116.4.1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulte-Merker S, van Eeden FJ, Halpern ME, Kimmel CB, Nusslein-Volhard C. no tail (ntl) is the zebrafish homologue of the mouse T (Brachyury) gene. Development. 1994;120:1009–1015. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.4.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Showell C, Binder O, Conlon FL. T-box genes in early embryogenesis. Dev Dyn. 2004;229:201–218. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stachel SE, Grunwald DJ, Myers PZ. Lithium perturbation and goosecoid expression identify a dorsal specification pathway in the pregastrula zebrafish. Development. 1993;117:1261–1274. doi: 10.1242/dev.117.4.1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strahle U, Jesuthasan S. Ultraviolet irradiation impairs epiboly in zebrafish embryos: evidence for a microtubule-dependent mechanism of epiboly. Development. 1993;119:909–919. doi: 10.1242/dev.119.3.909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tada M, Smith JC. T-targets: clues to understanding the functions of T-box proteins. Dev Growth Differ. 2001;43:1–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-169x.2001.00556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tada M, Casey ES, Fairclough L, Smith JC. Bix1, a direct target of Xenopus T-box genes, causes formation of ventral mesoderm and endoderm. Development. 1998;125:3997–4006. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.20.3997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talbot WS, Trevarrow B, Halpern ME, Melby AE, Farr G, Postlethwait JH, Jowett T, Kimmel CB, Kimelman D. A homeobox gene essential for zebrafish notochord development. Nature. 1995;378:150–157. doi: 10.1038/378150a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thisse B, Pflumio S, Fürthauer M, Loppin B, Heyer V, Degrave A, Woehl R, Lux A, Steffan T, Charbonnier XQ, Thisse C. Expression of the zebrafish genome during embryogenesis ZFIN Direct Data Submission. ZFIN Direct Data Submission 2001 [Google Scholar]

- Topczewski J, Solnica-Krezel L. Cytoskeletal dynamics of the zebrafish embryo. In: Detrich WH, Westerfield M, Zon LI, editors. Methods in cell biology the zebrafish: biology. London: Academic Press; 1999. pp. 206–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trinkaus JP. A study of mechanisms of epiboly in the egg of Fundulus heteroclitus. J Exp Zool. 1951;118:269–320. [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich F, Concha ML, Heid PJ, Voss E, Witzel S, Roehl H, Tada M, Wilson SW, Adams RJ, Soll DR, Heisenberg C-P. Slb/Wnt11 controls hypoblast cell migration and morphogenesis at the onset of zebrafish gastrulation. Development. 2003;130:5375–5384. doi: 10.1242/dev.00758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner DS, Dosch R, Mintzer KA, Wiemelt AP, Mullins MC. Maternal control of development at the midblastula transition and beyond: mutants from the zebrafish II. Dev Cell. 2004;6:781–790. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warga RM, Kimmel CB. Cell movements during epiboly and gastrulation in zebrafish. Development. 1990;108:569–580. doi: 10.1242/dev.108.4.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.