Abstract

Studies evaluating the efficacy of brief interventions with mandated college students have reported declines in drinking from baseline to short-term follow-up regardless of intervention condition. A key question is whether these observed changes are due to the intervention or to the incident and/or reprimand. This study evaluates a brief personal feedback intervention (PFI) for students (N = 230), who were referred to a student assistance program because of infractions of university rules regarding substance use, to determine whether observed changes in substance are attributable to the intervention. Half the students received immediate feedback (at baseline and after the 2-month follow-up) and half received delayed feedback (only after the 2 mo. follow-up). Students in both conditions generally reduced their drinking and alcohol-related problems from baseline to the 2 mo. follow-up and from the 2 mo. to the 7 mo. follow-up; however, there were no significant between-group differences at either follow-up. Therefore, it appears that the incident and/or reprimand are important instigators of mandated student change, and that written PFIs do not enhance these effects on a short-term basis, but may on a longer-term basis.

Keywords: College Students, Alcohol, Drugs, Brief Interventions, Mandated Students

Drinking and drug use among college students have received a lot of attention in scientific journals and the popular media. Heavy use has been associated with a host of negative consequences including fatal and nonfatal accidents and injuries, academic failure, violence and other crime, and unsafe sexual behavior (Hingson, Heeren, Winter, & Wechsler, 2005; Perkins, 2002; Presley, Meilman, & Cashin, 1996; Wechsler, Lee, Kuo, & Lee, 2000). Therefore, interventions are needed to reduce the risks associated with heavy drinking and drug use among college students.

One type of intervention that has been shown to be particularly efficacious with college students has been brief personalized feedback interventions (PFIs). PFIs are based on the assumption that if a student receives information about his or her drinking and drug use patterns in relation to peers, as well as his or her personal risk factors, the student will be motivated to change his or her use and will implement change (Miller, Toscova, Miller, & Sanchez, 2000). Recent reviews of rigorous evaluations have shown that in-person, mailed, and computer-generated PFIs reduce heavy drinking and related problems among high-risk college student volunteers, at least on a short-term basis (Larimer, Cronce, Lee, & Kilmer, 2004/2005; Walter & Neighbors, 2005; White, 2006). However, many of the studies relied on small samples and short-term follow-ups. In addition, effects sizes have been relatively modest in many of the studies (White, 2006).

Less research has evaluated PFIs for mandated students (i.e., students who are required to participate in an intervention by school authorities). White (2006) identified four randomized design studies of PFIs for mandated college students. Only one study, by Fromme and Corbin (2004), included a no (delayed) treatment control group. They found that all groups, including the control group, reduced their drinking over time. At the 6-week post-test, the only alcohol-related outcome that differentiated between treatment and control groups was driving after drinking and at the 6-month follow-up, there were no significant effects involving treatment condition. The other three studies compared a brief motivational intervention with personalized feedback to either an alcohol education CD-Rom (Barnett, Colby, & Monti, 2004; cited in Barnett et al., 2004), an alcohol education class (Borsari & Carey, 2005), or a written feedback intervention (White, Morgan, Pugh, Celinska, Labouvie, & Pandina, 2006). Results from these latter three studies indicated that students in all conditions reduced their substance use from baseline to a short-term follow-up.

Given that students in all conditions improved, the question remains as to whether the changes observed in studies of mandated students are due to the intervention or to other factors. The fact that most studies of mandated students have not included a no-treatment control group, due to ethical or clinical reasons (Barnett & Read, 2005), means that there is no way to determine whether the observed changes were due to the intervention, the incident, or being caught and reprimanded. Barnett, Colby, and Monti (2004) found that the majority of mandated students indicated that they had changed their behavior as a result of the incident. In a later analysis of these same data, Barnett, Goldstein, Murphy, Colby, and Monti (2006) found that the perceived adversity of the incident was positively related to motivation to change drinking behavior. Therefore, it is possible that decreases observed among mandated students are not due to the interventions.

Whereas studies of high-risk student volunteers support the short-term efficacy of computer and mailed PFIs (Collins, Carey, & Sliwinski, 2002; Neighbors, Larimer, & Lewis, 2004), the only study that tested the efficacy of a written feedback intervention for mandated students was White and colleagues (2006). They compared a written PFI to an in-person motivational PFI. At the 4-month follow-up, they found significant reductions from baseline in drinking behavior, related problems, and the prevalence of cigarette and marijuana use in both conditions. They found no significant between-group differences and concluded that, at least on a short-term basis, a written PFI is as efficacious as an in-person PFI with mandated students. However, at the 15-month follow-up, students in the in-person condition increased their alcohol use and related problems significantly less than those in the written feedback condition (White, Mun, Pugh, & Morgan, 2007). It is possible, therefore, that the short-term reductions observed in the written feedback condition were a response to the incident rather than the intervention.

This study attempts to test specifically whether written feedback interventions are efficacious for mandated students. We compare the short-term (at 2 months) and longer-term (at 7 months) effects of an immediate written PFI to a delayed written PFI for mandated students. By delaying feedback for one group, we can test whether the intervention had an effect beyond that of simply being caught and being mandated. Within our randomized design, both groups received feedback after the first follow-up. Therefore, we can also test whether the delayed feedback (for the delayed group) and the additional feedback (for the immediate feedback group) had an incremental effect on sustaining or accelerating reductions in use behaviors. Barnett et al. (2004) tested the effects of a booster for mandated students receiving a brief motivational intervention. They found no differences in alcohol use behaviors between those who received the booster and those who did not at the 3-month follow-up. We hypothesize that students in the immediate feedback group will reduce their substance use and related problems more than those in the delayed feedback group from baseline to the 2-month follow-up, thus reflecting effects of the personalized feedback intervention. Given that the feedback at the 2-month follow-up will be the first time that the delayed group receives an intervention, and also given the relatively small booster effects expected (Barnett et al., 2004), we hypothesize that students in the delayed group will reduce their substance use and related problems from the 2-month follow-up to the 7-month follow-up more than those in the immediate group.

Methods

Sample

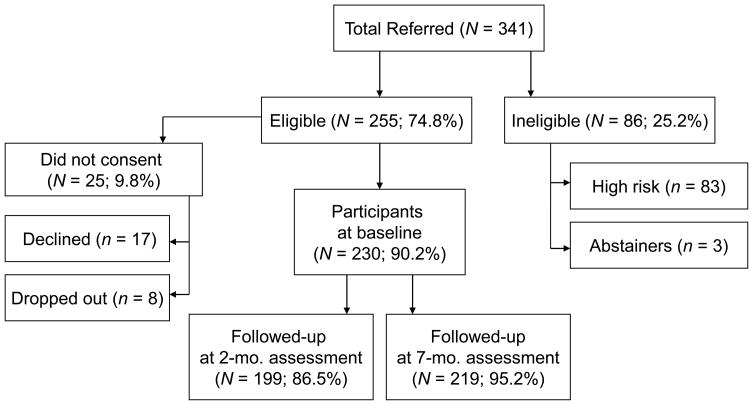

The sample consists of students who were mandated to the Rutgers University Alcohol and Other Drug Assistance Program for Students (ADAPS) because of violation of university rules about alcohol and drug use in residence halls between September 2005 and February 2006 (a total of 341 students referred). Almost all (90.2%) of the students were referred for an alcohol violation, 8.3% for a marijuana violation, and 1.5% for other violations. Most (81.9%) of the students were caught by a residence counselor for use in the dorms, which did not require medical attention, 15.4% were involved in an incident requiring medical or emergency attention, 1.2% got in trouble with the police, and the rest (1.5%) had another referral source. Students who were arrested for driving while intoxicated or other legal offenses were not included in this sample because of legal requirements. Because of the delayed treatment condition, the highest risk students were deemed clinically ineligible for the research project (n = 83; 24.3%). The high-risk ineligible students reported: 1) a peak blood alcohol concentration (BAC) in a typical week in the past month > .20%; 2) more than 10 alcohol-related problems in the last year; 3) more than 24 drinks in a typical week; 4) more than 10 drug-related consequences in the past year; 5) a Beck Depression Inventory (Beck & Steer, 1984) score > 12; 6) suicidal thoughts; 7) being arrested for DWI in past 3 months; 8) having had a prior residence life referral; 9) having received prior services at ADAPS; and / or 10) having had previous treatment (formal treatment or self-help) for alcohol or drug problems (excluding emergency room visits). In addition, students were deemed ineligible if residence life personnel reported concern about the student’s alcohol/drug use. An additional three students were ineligible because they were lifetime abstainers (had never tried) of alcohol and drugs. (These three students were simply caught in a room with someone else who was drinking or using drugs.) Of the 255 eligible students, 17 (6.7%) refused to participate in the study and eight students (3.1%) dropped out before they could be asked to participate (for total 25 non-consenters; 9.8%). These non-consenting students did not differ significantly (p > .05) from the consenting participants on their alcohol and drug use at baseline. (See Figure 1 for a flowchart showing recruitment, participation, and follow-up rates.)

Figure 1.

A flowchart of recruitment, participation, and follow-up rates.

The sample for the present study consists of 230 (164 males, 71.3%) eligible students who agreed to participate in the research project. The sample was predominantly Caucasian (68.1%), 17.7% Asian, 5.3% Hispanic/Latino, 3.5% Black, and 4.4% other or mixed. Most of participating students were in the first two years of college (62.6% first year, 27% second year). Table 1 presents a description of the sample in terms of sociodemographic variables and alcohol and drug use at the three assessments for the two intervention groups.

Table 1.

Demographics and Substance Use Variables for the Immediate and Delayed Intervention Groups (N = 230)

| Immediate (n = 111) |

Delayed (n = 119) |

t (df = 228) or χ2 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Baseline | 2 mo. | 7 mo. | Baseline | 2 mo. | 7 mo. | Baseline | 2 mo. | 7 mo. |

| Demographics | |||||||||

| Male | 69.4% | 73.1% | .39 | ||||||

| First-year student | 58.6% | 66.4% | 1.50 | ||||||

| Social desirability | 8.74 (2.39) | 8.87 (2.34) | .43 | ||||||

| Substance Use and Abuse | |||||||||

| Frequency of alcohol use past month | 2.38 (1.11) | 2.08 (1.34) | 1.73 (1.65) | 2.39 (1.15) | 2.06 (1.37) | 1.64 (1.76) | .11 (d =.02) | −.10 (d = .01) | −.42 (d = .06) |

| Number of heavy episodic drinking occasions in the past month | 1.07 (1.71) | .59 (.98) | .97 (1.99) | 1.06 (1.73) | .80 (1.40) | .82 (2.59) | −.06 (d = .01) | .93 (d = .12) | −1.12 (d = .15) |

| Peak BAC in a typical week | .04 (.05) | .03 (.04) | .03 (.04) | .05 (.05) | .04 (.04) | .03 (.04) | 1.07 (d = .14) | .50 (d = .07) | −.59 (d = .08) |

| Number of alcohol problems in the past 2 months | .89 (1.48) | .80 (1.53) | .50 (1.09) | .90 (1.24) | .66 (1.28) | .52 (1.50) | .50 (d = .07) | −.56 (d = .07) | −.61 (d = .08) |

| Number of cigarettes smoked per day in the past month | 1.36 (5.27) | .97 (3.05) | .81 (2.53) | .53 (2.05) | .37 (1.32) | .34 (1.34) | −1.59 (d = .21) | −1.70 (d =.22) | −1.92 (d = .25) |

| Frequency of marijuana use in the past month | .61 (1.25) | .49 (1.17) | .34 (1.02) | .53 (1.10) | .59 (1.37) | .31 (.97) | −.40 (d = .05) | .37 (d = .05) | −.18 (d = .02) |

Note. All χ2 and t test results in the last column were not statistically significant, indicating no statistical between-group differences in all measures. Immediate = Immediate Personalized Feedback Intervention, Delayed = Delayed Personalized Feedback Intervention; BAC = Typical peak blood alcohol concentration. Percentages are reported for dichotomous variables and means and standard deviations (in parentheses) are reported in original measurement units for continuous variables. Inferential statistics were conducted using log-transformed variables. 2 mo. = 2-month follow-up assessment; 7 mo. = 7-month follow-up assessment. d = Cohen’s measure of effect size (Cohen, 1988, p. 40).

Interventions and Procedures

In the first session, all students referred to ADAPS completed a baseline assessment on a PC. The personalized written feedback profile and a “clinician alert” sheet (identifying any students who were ineligible based on the criteria described above) were immediately printed out by the ADAPS clinician. Those students deemed eligible were randomly assigned (by the flip of a coin) to either the immediate or the delayed feedback condition. Students in the immediate condition (n = 111; 48.3%) were handed their personalized feedback profile, which included information on a student’s drinking and drug use patterns in comparison to other college students of the same sex, typical and heaviest week peak BAC, alcohol- and drug-related problems, alcohol expectancies, risky behaviors (e.g., unplanned sex after using alcohol or drugs), and personal risk factors (e.g., depression score, family history of alcoholism). In addition, it contained educational information about the effects of various BAC levels, strategies to reduce risky behavior, the negative consequences of smoking, the amount of money spent on cigarettes and alcohol, and the amount of calories from drinking each week and how much exercise it would take to lose those calories. Students were then scheduled to return 2 months later. The profiles were not discussed with students. Students in the delayed condition (n = 119; 51.7%) were scheduled to return in 2 months, but did not receive their profile.

At the 2-month follow-up, students were asked whether they wished to participate in the research (which did not affect the intervention they received) and informed consent forms were signed. At this point, students were told that their information for the study would be used only for research purposes and that their data were protected by a Federal Certificate of Confidentiality. The study was approved by the Rutgers Institutional Review Board for the Protection of Human Subjects in Research. At this session, students in both conditions again completed an assessment on a PC asking about their drinking and drug use during the past 2 months. Those in the immediate condition were given a personalized profile form (similar to the first one they had received) based on the information from their second assessment. Students in the delay condition were given both their baseline and 2-month personal profiles at the second session. The profiles were not discussed with students in either condition. A total of 199 eligible consenting students returned for the 2-month assessment. The mean length of time for the 2-month follow-up was 68 days (SD = 21 days) after the baseline assessment.

Students then completed a third assessment 7 months after baseline (N = 219) either on a PC at ADAPS (11%) or over the telephone (89%). The follow-up was supposed to be scheduled 6-months post baseline. However, due to some difficulty in contacting and scheduling students, the mean interval was approximately 7 months (mean = 209 days, SD = 28 days) from the baseline survey.1 There were no significant (p > .05) differences between those who were interviewed over the phone and those who responded on the PC for any of the outcomes except that the PC responders reported higher frequency of alcohol use in the last 2 months than telephone interview responders [means 2.41 versus 1.52, respectively, t (df = 27.3) = 2.45, p < .05].2

Attrition analyses were conducted for those who completed the 2-month and the 7-month assessments and those who did not. There were no significant (p >. 05) differences between participants at the 2-month follow-up and non-participants on all measures of alcohol and drug use at baseline. Those 11 students who did not complete the 7-month assessment did not differ from those who participated on all measures of alcohol and drug use at baseline, with a single exception of marijuana use. Non-participants reported a slightly greater frequency of marijuana use at baseline than participants [means .70 versus .26, respectively, t (df = 10.7) = 2.36, p < .05].3

Measures

Intervention condition

The immediate PFI condition was coded 1 and delayed PFI condition was coded 0.

Outcome measures

Substance use was assessed similarly at baseline, at the 2-month follow-up, and at the 7-month follow-up. We examined six alcohol and drug use variables separately in order to investigate specific effects of the immediate PFI across different domains of use over time. Past month alcohol frequency was measured on a 8-point ordinal scale: 0 = never; 1 = not in the last month; 2 = once a month; 3 = 2–3 times a month; 4 = 1–2 times a week; 5 = 3–4 times a week; 6 = 5–6 times a week; and 7 = daily. Students also reported the number of occasions of heavy episodic drinking (five or more drinks for males and four or more for females during one drinking occasion) in the past month (Wechsler, Lee, Kuo, Seibring, Nelson, & Lee, 2002). Questions adopted from the Modified Daily Drinking Questionnaire (Collins, Parks, & Marlatt, 1985) were used to assess the number of drinks and the number of hours of drinking each day in a typical week in the last month. The responses to these questions were combined with sex and body weight to determine the peak BAC for each day of the week based on a modified version of the Widmark (1932) formula. From these estimations, we selected the highest peak BAC in a typical week. We also measured the frequency of marijuana use in the past month on a 7-point ordinal scale: 0 = never; 1 = not in the last month; 2 = once a month; 3 = 2–3 times a month; 4 = 1–2 times a week; 5 = 3–4 times a week; and 6 = nearly daily or daily, and typical quantity of cigarettes smoked per day in the last month (ranging from 0 to more than 20).

Alcohol-related problems were measured using the Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index (RAPI; White & Labouvie, 1989). The RAPI has demonstrated reliability and discriminant and construct validity in both general population and clinical samples of adolescents and young adults (White, Filstead, Labouvie, Conlin, & Pandina, 1988; White & Labouvie, 1989, 2000). For these analyses we counted the total number of problems experienced in the last 2 months (range 0–18) (α = .66 – .77 across the three assessments). Note that we did not include drug-related problems because few students reported any drug-related problems in this sample.

Control variables

We controlled for sex (coded 1 for males and 0 for females) and year in college (dichotomized with first year coded 1 and second through fourth year coded 0) because these two variables are related to patterns of substance use (Bachman, Wadsworth, O’Malley, Johnston, & Schulenberg, 1997; Baer, Kivlahan, Blume, McKnight, & Marlatt, 2001; Carey, Carey, Maisto, & Henson, 2006).

Social desirability and self-report alcohol and drug use

Data come from participant self-report. Other researchers have shown that college students can provide valid alcohol and drug use data (e.g., Darke, 1998) and that the use of collateral reports does not necessarily improve accuracy or reliability of the data (Marlatt, Baer, Kivlahan, Dimeff, Larimer, Quigley, et al., 1998). However, it should be noted that these studies were conducted with volunteer students, and mandated students might under-report their use due to their special circumstance. Therefore, we included a shortened version (13 items) of the Social Desirability Scale (SDS; Andrews & Meyer, 2003, α = .66) in the baseline questionnaire. We found that high social desirability at baseline was significantly correlated with reporting lower levels of some measures of alcohol and drug use at baseline and at the 2-month follow-up, but not at the 7-month follow-up.4 However, there were no significant differences between the delayed and immediate groups in SDS scores at baseline (see Table 1). We did not control for social desirability scores in the analyses because self-reported alcohol and drug use due to demand characteristics of a participant would be equivalent in both intervention groups.

Analyses

All substance use variables, with the exception of frequency of alcohol use, were log-transformed after adding a constant of one to normalize skewed, over-dispersed distributions. The measure of frequency of alcohol use showed skewness ranging from −.32 to .43 at the three different assessments, while all other measures had skewness ranging from 1.04 to 7.69, with significant t ratios (i.e., the critical ratio of skewness to SE). The total sample of 230 participants had a small portion of missing data across three measurements (a total of 5.3% of missing item-level observations). Little’s chi-square test of Missing Completely At Random (MCAR test; Little, 1988) resulted in a significant χ2 (df = 94) = 125.81, p = .02. However, the ratio of χ2 to the degrees of freedom was small, and the MCAR assumption tends to be very conservative; thus, we determined that missingness is rather ignorable and the subsequent imputation of missing values is unbiased (Little & Rubin, 1987; Schafer, 1997). The expectation maximization (EM) algorithm for maximum likelihood (ML) estimation was utilized for missing data imputation using the SAS program (SAS Institute, 2002–2006).

We conducted two analyses. First, we conducted paired t-tests to investigate whether students’ substance use decreased in two separate periods from their baseline to 2-month follow-up, and from their 2-month to 7-month follow-up separately for the immediate and delayed PFI conditions. These analyses were conducted separately for the two conditions and, thus, test for within-group changes. Second, we analyzed the change across the two groups using linear growth models. We used a hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) software package (version 6.02; Raudenbush, Bryk, & Congdon, 2005) to examine intra-individual change over time by conceptualizing repeated measures as being nested within the individual. This type of analysis examines within-individual change across the two intervention conditions. Thus, it allows us to test our hypotheses regarding the differential effects of the immediate and delayed PFIs on changes in substance use. Since students’ substance use levels at the 2-month assessment across the immediate and delayed PFI groups indicated the effects of the immediate PFI on their substance use and related problems, we used a coding scheme that makes the intercept coefficient correspond to the level of outcome at the 2-month follow-up assessment (instead of corresponding to the baseline level). In addition, baseline levels of substance use were of little interest since students were randomly assigned to either group and analyses indicated no significant differences between groups at baseline (see below). This coding scheme (see Appendix) also allowed two different linear patterns during the two distinct temporal phases: (1) the first phase between baseline and the 2-month follow-up, and (2) the second phase between the 2-month follow-up and 7-month follow-up assessments. Based on this coding scheme, the change between baseline and the 2-month follow-up was indicated by the first change parameter, while the second change parameter indicated the change during the period between the 2-month and 7-month follow-up assessments. Negative parameter estimates for changes indicate a decrease (see Appendix for detail).

We tested two models. The first model included two code variables and an intercept to indicate two different linear change patterns during the two temporal phases, and the outcome level at the 2-month follow-up (unconditional two-piece linear model). An intercept from this model would indicate the aggregate-level outcome across all participants at the 2-month follow-up. Results would also indicate the direction and magnitude of change during the two phases. Change parameters were specified as non-random because the time-series was short (three time points) and three parameters were required to adequately fit the data, thus leaving no degrees of freedom to incorporate random components into the model. Therefore, all potential random variation was absorbed into a 3 × 3 covariance matrix that captured all variation and covariation among three repeated observations.

For the conditional model, we added immediate (versus delayed) condition, first-year student (versus second- to fourth-year student), and male (versus female) as between-individual factors to the unconditional model to see if the change over time would be explained by these between-individual factors. This analysis provides tests of significant between-group differences (e.g., immediate vs. delayed PFI) on students’ substance use at the 2-month, and their changes from baseline to the 2-month, and from the 2-month to the 7-month follow-ups. Statistically improved overall model fit of the conditional model over the unconditional model fit would indicate that individual differences in intra-individual change during the two phases are explained by the added between-individual factors.

Results

Baseline Group Differences in Levels

Table 1 presents a description of the sample in terms of sociodemographic variables and baseline alcohol and drug use. The chi-square results presented in the third column in Table 1 indicate between-intervention condition group differences in the demographic variables at baseline and the t-test results indicate between-group differences in the substance use measures at baseline, the 2-month follow-up, and the 7-month follow-up. At baseline, there was no significant difference in any measures between students assigned to the immediate PFI condition and those assigned to the delayed PFI. Therefore, the randomization process was deemed successful. There were also no significant differences between groups on any alcohol or drug use measures at either follow-up assessment.5 The lack of significant findings between the two groups was not due to insufficient sample size. The effect sizes (d) presented in the third column of Table 1 for the between-intervention condition group differences indicate that, with a single exception of cigarette use which had a small effect, between-group effects were almost nonexistent for all measures of alcohol and drug use.

Overall Within-individual Changes

We examined within-individual changes over the 7-month period following the brief interventions using paired t-tests (see Table 2). Mandated students in the immediate PFI condition significantly decreased their frequency of alcohol use, frequency of heavy episodic drinking, and peak BAC levels at 2 months post-intervention, compared to their baseline levels. From the 2-month to the 7-month follow-up (after their “booster” written PFI), these students in the immediate PFI further significantly decreased their frequency of alcohol use, and reported fewer alcohol-related problems. Mandated students in the delayed PFI condition significantly decreased their frequency of alcohol use, and reported fewer alcohol-related problems and decreased peak BAC levels at the 2-month follow-up without having received any personalized feedback. After receiving a written PFI at the 2-month assessment, students further significantly decreased their frequency of alcohol and marijuana use, their peak BAC levels, and the number of alcohol-related problems when assessed at the 7-month follow-up.6

Table 2.

Within-individual Reduction in Substance Use Measures at the 2-Month and 7-Month Follow-ups (N = 230)

| Immediate (n = 111) |

Delayed (n = 119) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | Mean | t | d | Mean | t | d |

| From baseline to 2 mo. | ||||||

| Frequency of alcohol use | −.30* | −2.45 | .23 | −.33** | −3.05 | .28 |

| Number of heavy episodic drinking occasions | −.17** | −3.10 | .29 | −.10 | −1.80 | .16 |

| Peak BAC | −.01* | −2.57 | .24 | −.01** | −3.01 | .28 |

| Number of alcohol-related problems | −.05 | −.84 | .08 | −.13* | −2.55 | .23 |

| Number of cigarettes smoked per day | −.03 | −.94 | .09 | −.02 | −.78 | .07 |

| Frequency of marijuana use | −.07 | −1.51 | .14 | −.01 | −.40 | .04 |

| From 2 mo. to 7 mo. | ||||||

| Frequency of alcohol use | −.35* | −2.48 | .24 | −.42** | −3.03 | .28 |

| Number of heavy episodic drinking occasions | .07 | 1.47 | .14 | −.08 | −1.52 | .14 |

| Peak BAC | −.00 | −1.14 | .11 | −.01* | −2.37 | .22 |

| Number of alcohol-related problems | −.12* | −2.14 | .20 | −.12* | −2.11 | .19 |

| Number of cigarettes smoked per day | −.02 | −.45 | .04 | −.03 | −1.47 | .13 |

| Frequency of marijuana use | −.07 | −1.87 | .18 | −.11** | −2.85 | .26 |

Note. p < .05

p < .01, Negative mean changes indicate decreased levels of substance use. Immediate = Immediate Personalized Feedback Intervention, Delayed = Delayed Personalized Feedback Intervention; BAC = Typical peak blood alcohol concentration. d = Cohen’s (1988) measure of effect size.

Between-group Differences in Changes

Results from the unconditional and conditional two-piece linear models (see Table 3) were consistent with the results shown in Tables 1 and 2. At the aggregate level, all alcohol use outcomes showed a statistically significant initial decrease between baseline and the 2-month assessment, subsequently followed by a statistically significant decrease from the 2-month to the 7-month assessment. Cigarette smoking did not show any decrease during the 7-month period. Marijuana use decreased significantly from baseline to the 7-month follow-up, but not from baseline to the 2-month follow-up.

Table 3.

Parameter Estimates from the Two-piece Linear Model (N = 230)

| Freq. drinking | Heavy drinking | Peak BAC | Alcohol problems | Cigarette smoking | Marijuana use | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unconditional Model | ||||||

| Level at 2 months post intervention | 2.07** (.09) | .37** (.03) | .03** (.00) | .35** (.04) | .21** (.04) | .25** (.03) |

| Initial decrease (0 – 2 mo.)1 | −.31** (.08) | −.14** (.04) | −.01** (.00) | −.10* (.04) | −.03 (.02) | −.04 (.03) |

| Subsequent decrease (2–7 mo.)1 | −.39** (.10) | −.01 (.04) | −.01* (.00) | −.12** (.04) | −.02 (.02) | −.09** (.03) |

| Deviance (9 parameters) | 2235.30 | 1085.39 | 601.03 | 1049.78 | 677.43 | 694.90 |

| AIC | 2253.30 | 1103.39 | 619.03 | 1067.78 | 695.43 | 712.90 |

| Conditional Model | ||||||

| Intercept (Level at 2 mo.) | 2.06** (.22) | .39** (.08) | .03** (.01) | .28** (.09) | .15 (.09) | .18* (.09) |

| Immediate (1; delay = 0) 2 | .01 (.18) | −.07 (.07) | −.00 (.01) | .05 (.07) | .13 (.08) | −.02 (.07) |

| Male (1; female = 0) 2 | .10 (.20) | .12 (.07) | .00 (.01) | −.03 (.08) | .05 (.08) | .14 (.08) |

| First-year (1; else = 0) 2 | −.11 (.18) | −.1 2 (.07) | −.00 (.01) | .12 (.08) | −.05 (.08) | −.03 (.07) |

| Intercept (Initial decrease 0–2 mo.) | −.39 (.20) | −.04 (.10) | −.01 (.01) | −.20 (.10) | −.05 (.06) | −.00 (.07) |

| Immediate (1; delay = 0) 3 | .04 (.16) | −.08 (.08) | .00 (.01) | .08 (.08) | −.01 (.05) | −.06 (.05) |

| Male (1; female = 0) 3 | .04 (.18) | .02 (.09) | .01 (.01) | .13 (.09) | .06 (.05) | .07 (.06) |

| First-year (1; else = 0) 3 | .04 (.17) | −.12 (.08) | −.01 (.01) | −.04 (.09) | −.03 (.05) | −.09 (.06) |

| Intercept (Subsequent decrease 2–7 mo.) | −.53* (.24) | −.18* (.09) | −.01 (.01) | −.16 (.10) | −.01 (.06) | −.03 (.07) |

| Immediate (1; delay = 0) 3 | .07 (.19) | .16* (.07) | .01 (.01) | −.00 (.08) | .01 (.04) | .03 (.05) |

| Male (1; female = 0) 3 | .46* (.21) | .07 (.08) | −.00 (.01) | .17 (.09) | −.05 (.05) | −.15* (.06) |

| First-year (1; else = 0) 3 | −.34 (.20) | .07 (.08) | .00 (.01) | −.12 (.08) | .03 (.05) | .05 (.06) |

| Deviance (18 parameters) | 2225.33 | 1072.05 | 593.55 | 1035.52 | 670.17 | 684.63 |

| AIC | 2261.33 | 1108.05 | 629.55 | 1071.52 | 706.17 | 720.63 |

| Δ Deviance (Δdf = 9) 4 | 9.97 | 13.34 | 7.48 | 14.26 | 7.26 | 10.27 |

Note. p < .05,

p < .01; Numbers in parenthesis are standard errors. Immediate = Immediate Personalized Feedback Intervention, Delay = Delayed Personalized Feedback Intervention, BAC = Typical peak blood alcohol concentration, AIC = Akaike Information Criterion.

= Negative coefficients indicate decreases and the size of coefficients indicates the amount of decrease in the measurement units analyzed;

= Positive coefficients indicate higher levels of substance use at the 2-month for those in the Immediate PFI or those who are male or freshmen;

= Positive coefficients indicate less reduction and negative coefficients indicate more reduction for those in the Immediate PFI or those who are male or freshmen; and

= Deviance = −2 Log Likelihood (LL), and the χ2 tests of the differences in deviance resulted in non-significant reductions (p > .05). Their exact p values were .35, .15, .59, .11, .61, and .33, respectively.

All conditional models with between-individual factors, including immediate PFI effects, did not statistically improve the model fit based on the chi-square tests of the differences in deviance and also on the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). The AIC takes into account the number of parameters estimated in the model and can be used to compare non-nested models. The model with the smaller AIC fits better. In the current study, for all outcome measures, the unconditional model fit the data better, which means that the immediate (versus delayed) condition, first-year student (versus second- to fourth-year student), and male (versus female) as the set of predictors did not explain outcomes above and beyond what was expected for the degrees of freedom invested. Therefore, after controlling any potential effects of being male and a first-year college student, there were no between-intervention condition group differences in the decreases from baseline to the 2-month assessment, and from the 2-month to the 7-month assessment.7 In addition, at the 2-month assessment, the delayed PFI group did not differ from the immediate PFI group on all six alcohol and drug use variables (see the third row from the conditional model in Table 3).

Discussion

The results of this study indicate that the written PFI did not account for short-term changes in substance use among mandated students. However, there may have been longer-term positive effects of the written PFI. In terms of the short-term reductions, we found that mandated students in both groups significantly reduced aspects of their drinking behavior, but those who received the written feedback immediately did not differ significantly from those who did not receive it until the 2-month follow-up. Therefore, it is probable that these mandated students significantly reduced their drinking following the incident or as a result of being caught and being mandated. Clearly, interventions are needed to capitalize on the incident, or what Barnett, Monti, and Wood (2001) refer to as the “teachable moment.” In the Barnett et al. (2006) study, however, only 29% of the mandated students were in the planning or action stage of change following the incident, which suggests that even serious incidents were not sufficient to cause most students to reduce their drinking. Barnett et al. also found that lighter drinkers were more affected by the incident than heavier drinkers. They suggested that less experienced drinkers may become quickly motivated to avoid further heavy drinking, whereas heavier drinking students, who regularly experience the benefits of drinking, may be less affected by a single alcohol-related incident. That is, frequent drinkers may still decide that the benefits of drinking outweigh the costs and may not be ready to reduce their drinking. Therefore, the incident, compared to the intervention, may have shown a stronger short-term effect in our study because the heaviest drinkers were eliminated. Studies of volunteer students have also suggested that it is the heaviest drinkers who benefit most from brief interventions (Murphy, Duchnick, Vuchinich, Davison, Karg, Olson, et al., 2001). The fact that we excluded the highest risk students (due to clinical and ethical reasons) may have undermined our ability to observe intervention effects.

There was an additional reduction in alcohol use and related problems from the 2-month to the 7-month follow-up, again with no between-group differences. Given that both groups received the written feedback at the 2-month follow-up, it is possible that this written feedback had a positive effect on changes in alcohol use after the initial post-incident reduction. We had expected greater change for the delayed than the immediate group after the 2-month PFI because this would have been their first intervention. Perhaps the initial PFI occurred too soon after the incident, and, thus, had little impact above that of the incident for the immediate group. Instead, the 2-month PFI may have served the same purpose for these students as it did for those in the delayed group. Without a third group who did not receive the feedback at 2 months, we cannot be certain that the changes were due to intervention. However, if the written feedback intervention was efficacious beyond the effect of the incident, then it may make sense to institute a booster feedback session for mandated students.8

There are other possible explanations for the observed reductions in substance use besides the incident or getting caught and mandated (for changes at 2 months) and the intervention (for changes at 7 months). First, studies of college students have shown a natural reduction in drinking over time (Baer et al., 2001). However, in an evaluation of a PFI for mandated students, White and colleagues (2006) found that the reductions in substance use and related problems from baseline to follow-up were not due to developmental changes or regression to the mean. A second possible explanation is that the assessment itself (i.e., completing a questionnaire about one’s substance use) causes a student to reduce his or her drinking (Carey et al., 2006; Fromme & Corbin, 2004). White and colleagues (2006) tested for this possibility and concluded that completing an assessment did not account for the short-term decreases in substance use that they observed for mandated students. They acknowledged, however, that a required assessment for mandated students may have a different effect than a questionnaire administered to non-mandated volunteers. Further, Carey and colleagues (2006) found that a brief motivational intervention clearly had added short-term benefits beyond a thorough assessment with high-risk student volunteers.

Our findings for drug use were relatively weak. There were no significant reductions in cigarette use at either follow-up for either group. There was a significant reduction in marijuana use only from the 2-month to the 7-month follow-up only for the delayed group. The assessment and profile highlighted alcohol use in much more detail than drug use and this difference might account for the lack of significant drug use findings. In addition, most students were referred for alcohol-related incidents and rates of smoking and frequency of marijuana use were relatively low even at baseline. Therefore, there may have been less room to measure change for drugs rather than alcohol (i.e., floor effects). In a previous study comparing an in-person to a written PFI for mandated students, we found that both interventions reduced the prevalence of smoking and marijuana use at the 4-month follow-up (White et al., 2006), but not the quantity of cigarettes or frequency of marijuana use at 4 months and 15 months post-intervention (White et al., 2007). Therefore, for low base-rate behaviors, such as tobacco and marijuana use in this sample, reducing prevalence may be a realistic goal. More research is needed to test drug-specific PFIs for college students.

The results of the present study should be interpreted cautiously due to several limitations. First, we had to eliminate the highest risk students (24%) for clinical and ethical reasons. Their exclusion reduced our power to find significant group differences in reductions, due in part to a reduced sample size but more importantly because the students who were excluded had the greatest room for change and were more comparable to the high-risk volunteers used in other studies that have evaluated written feedback interventions. However, potential effects due to the exclusion of high-risk students on current findings are far from clear. Although it is reasonable to assume that the reported reductions over time in this current study would be greater with the inclusion of the high-risk sample, it is uncertain how it would affect between-group differences in reductions with students being randomly assigned. Second, we relied on participant self-report and did not validate their reports. However, other studies of college student drinking and related problems have shown that use of collaterals does not improve validity of the data (Carey et al., 2006; Marlatt et al., 1998). Nevertheless, these other studies were not with mandated students, who may be more motivated to under-report use levels. Our findings on social desirability with mandated students support the notion that students with high demand characteristics tend to under-report their alcohol and drug use. In our study, social desirability levels were equivalent for students in both intervention conditions, and consequently deemed to have neutral effects on outcomes. Third, most students completed the 7-month follow-up as a telephone survey, which could have resulted in lower rates of reported substance use. However, Chassin, Presson, Sherman, and Edwards (1990) found that telephone interviews are as reliable as in-person interviews for collecting sensitive information, such as drug use (see also McAuliffe, Geller, LaBrie, Paletz, & Fournier, 1998). Further, Petrie, Fleming, Haggerty, Catalano, Harachi, and Brown (2005) found no significant differences in responses to substance use questions between youth who completed surveys online and those interviewed in person. In our study, we found only one significant difference between those students who completed the follow-up on the PC and those who responded to the telephone interview and this difference was not substantive (see footnote 2). Fourth, we did not have a measure of intervention fidelity to determine if the students read and understood their personal profiles. However, in a previous study with similar mandated students, we found that those in a written feedback condition were as likely to read their written profiles as those who went over their profiles with a counselor (White et al., 2007).9 Finally, the sample was predominantly white and may not generalize to other ethnic/racial groups.

Despite these limitations, this is the first study to rigorously evaluate the efficacy of a written PFI for mandated college students. Previous evaluations of mailed and computer-generated written PFIs have shown that they are efficacious for college student volunteers when compared to a no-treatment control (Collins et al., 2002; Neighbors et al., 2004). In contrast, our results showed that written PFIs may not be efficacious for mandated students on a short-term basis. Therefore, they may work better with volunteer than mandated students. That is, the incident or being caught and reprimanded may have a stronger effect than written PFIs on causing reductions in alcohol and drug use for mandated students. Perhaps those students who do not change their behavior as a result of the incident need an in-person motivational intervention to help motivate them to change. White et al. (2007) have shown that a brief in-person motivational intervention clearly had long-term benefits over a written feedback intervention for mandated students. In-person counseling may be needed to increase the depth of processing of the feedback information or to elicit a verbal commitment to change (Walters & Neighbors, 2005). Therefore, more research is needed to evaluate motivational interventions for mandated students and to determine the most effective ways to capitalize on the “teachable moment.”

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA 17552) as part of the Rutgers Transdiscplinary Prevention Research Center. The authors thank Lisa Laitman, Barbara Kachur, Brian Kaye, Corey Grassl, Lisa Pugh, and Kelly Pugh for their help with the data collection and their commitment to the research project and Adam Thacker for his help with data base management. We also thank three anonymous reviewers for their comments and suggestions.

Appendix

A Coding Scheme Used in the Study for a Two-piece Linear Model

| Coding | Baseline | 2-month | 7-month | Interpretation of estimated change parameters |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 1 | 1 | 1 | p0 - Outcome level at 2-month follow-up |

| 1st code variable | −1 | 0 | 0 | p1 - Initial change during the first phase between baseline and the 2-month assessment |

| 2nd code variable | 0 | 0 | 1 | p2 - Subsequent change during the second phase between the 2-month and 7-month follow-ups |

The unconditional model at level 1 can generally be expressed as

ŷt = p0 + p1 code1 + p2 code2, where p0, p1, and p2 indicate an intercept, the first change parameter, and the second change parameter, respectively. Inserting code variables (code1 and code2) results in simplified formulas

ŷt=1 = p0 + p1 * (−1) at baseline,

ŷt=2 = p0 at the 2-month, and

ŷt=3 = p0 + p2 * (1) at the 7-month follow-up. Therefore, the change from baseline and to the 2-month assessment can be captured by ŷt=1 − ŷt=2 = (p0 − p1) − (p0) = − p1 and the change from the 2-month to the 7-month is expressed as ŷt=2 − ŷt=3 = (p0) − (p0+ p2) = − p2.

Positive p1 or p2 indicates an increase in an outcome; negative p1 or p2 indicates a decrease in an outcome.

Footnotes

There was one case who had a much shorter follow-up period in which the 2-month and the 7-month assessment measures overlapped in the referent time frame. When this case was omitted, the results did not change.

The reported degrees of freedom were adjusted for unequal variances due to disproportionate group sizes. Although mean differences were statistically significant, when values are rounded to the closest ordinal level, both groups reported consuming alcohol approximately once a month.

The reported degrees of freedom were adjusted for unequal variances due to disproportionate group sizes. Both groups reported approximately no use of marijuana.

The significant (p < .05) correlations with social desirability at baseline were: r = −.17, −.16, −.23, and −.14, respectively, for heavy episodic drinking, peak BAC, alcohol-related problems, and marijuana use. The significant correlations with social desirability at the 2-month follow-up were: r = −.30, −.26, −.26, and −.28, respectively, for frequency of alcohol use, heavy episodic drinking, peak BAC, and alcohol-related problems. Social desirability was not related to alcohol and drug use at the 7-month follow-up. Therefore, demand characteristics of students were related to the majority of self-reported alcohol and drug use at baseline and the 2-month follow-up assessments with their effect sizes generally classified as small (r = .1, .3, and .5 respectively for small, medium, and large effects; Cohen, 1988). However, over the long term any effects of demand characteristics on self-reported alcohol and drug use seemed to wane.

We additionally conducted nonparametric tests to examine whether group differences existed in alcohol and drug use and alcohol-related problems at each assessment using non-transformed raw data. When distributional assumptions (e.g., normally distributed data) are not met, nonparametric tests are an alternative to parametric tests (e.g., t-tests) conducted using log-transformed data. Unlike parametric tests, nonparametric tests involve a very few assumptions regarding the population distribution from which the data are sampled. Thus, ordinal data or skewed data can be analyzed using nonparametric tests. The Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney tests resulted in the same conclusion as reported; that is, there were no differences in all outcome measures at any assessment between the immediate and delayed PFI groups.

As an alterative to paired t-tests using transformed data, we additionally conducted nonparametric tests to examine the intra-individual changes in the six outcomes based on non-transformed raw data using the Wilcoxon’s signed rank tests. For the immediate PFI group, nonparametric tests indicated that the reported significant decrease in alcohol-related problems from the 2-month to the 7-month assessment in Table 2 was not replicated, while we found significant reductions in marijuana use in both time periods and peak BAC levels from the 2-month to the 7-month assessment. However, nonparametric test results converged on the same findings as reported in Table 2 for the delayed PFI group. In the context that the Wilcoxon’s signed rank test tends to be affected by inflated type I error probability under the skewed population distribution of the positive and negative change/difference scores (Tamhane & Dunlop, 2000, p. 569), some of the significant findings for the immediate PFI group may need to be cautiously interpreted.

We ran the conditional model with just one predictor (immediate vs. delayed PFI). Based on the AIC, this intermediate conditional model fit the data best in all analyses due to its parsimony. However, in all models, none of the parameters indicate that the PFI group effect on change was significant.

We additionally analyzed students’ readiness to change measured by the Readiness to Change Questionnaire (RTCQ; Heather & Rollnick, 2000). The Pre-contemplation items were reverse coded to represent a global scale of readiness to change (Budd & Rollnick, 1996; Forsberg, Halldin, & Wennberg, 2003) and Chronbach’s alpha at baseline for all 12 items in this sample was .85. Readiness to change did not significantly change from the baseline to the 2-month assessment or from the 2-month to the 7-month assessment for either intervention condition group. In addition, we did not find any significant difference in readiness to change between students assigned to the immediate PFI condition and those assigned to the delayed PFI at the baseline, 2-month, and 7-month assessments. Therefore, we concluded that students’ readiness to change at baseline and their progression (or regression) over time does not explain the reductions in alcohol and drug use in the current study and also that the written PFI had no effect on readiness to change.

We ran chi-square analyses to compare ADAPS mandated students from an evaluation study comparing a brief motivational PFI (BMI) to a written feedback only PFI (WF) conducted by White and colleagues (2007). There were no significant differences between the WF and BMI students in the percent who read their written profile [7.7% vs. 3.4%, respectively; χ2 (df = 1) = 2.00, p > .05] and the percent who reported that they did not understand the ADAPS program [10.6% vs. 5.1%, respectively; χ2 (df = 1) = 2.30, p > .05].

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/journals/adb

References

- Andrews P, Meyer RG. Marlowe-Crowne social desirability scale and sort form C: Forensic norms. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2003;59:483–492. doi: 10.1002/jclp.10136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachman JG, Wadsworth KN, O’Malley PM, Johnston LD, Schulenberg J. Smoking, drinking and drug use in young adulthood: The impacts of new freedoms and new responsibilities. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum Associates; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS, Kivlahan DR, Blume AW, McKnight P, Marlatt GA. Brief intervention for heavy drinking college students: Four-year follow-up and natural history. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;98:1310–1316. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.8.1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett NP, Colby SM, Monti P. Brief motivational intervention with college students following medical treatment or discipline for alcohol (pp. 971–973). In N. P. Barnett, T. O. Tevyaw, K. Fromme, B. Borsari, K. B. Carey, & W. R. Corbin, et al. (2004) Brief alcohol interventions with mandated or adjudicated college students. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2004;28:966–975. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000128231.97817.c7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett NP, Goldstein AL, Murphy JG, Colby SM, Monti PM. “I’ll never drink like that again”: Characteristics of alcohol-related incidents and predictors of motivation to change in college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67:754–763. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett N, Monti PM, Wood M. Motivational interviewing for alcohol-involved adolescents in the emergency room. In: Wagner EF, Waldron HB, editors. Innovations in adolescent substance abuse interventions. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Pergamon/Elsevier Science Inc; 2001. pp. 143–168. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett NP, Read JP. Mandatory alcohol intervention for alcohol abusing college students: A systematic review. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2005;29:147–158. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett N, Tevyaw T, Fromme K, Bosari B, Carey KB, Corbin WR, et al. Brief alcohol interventions with mandated or adjudicated college students. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2004;28:966–975. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000128231.97817.c7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA. Internal consistencies of the original and revised Beck Depression Inventory. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1984;40:1365–1367. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(198411)40:6<1365::aid-jclp2270400615>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey KB. Two brief alcohol interventions for mandated college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19:296–302. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.3.296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budd R, Rollnick S. The structure of the readiness to change questionnaire: A test of Prochaska & DiClemente’s transtheoretical model. British Journal of Health Psychology. 1996;1:365–376. [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Carey MP, Maisto SA, Henson JM. Brief motivational interventions for heavy college drinkers: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:943–954. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.5.943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Presson CC, Sherman SJ, Edwards DA. The natural history of cigarette smoking: Predicting young adult smoking outcomes from adolescent smoking patterns. Health Psychology. 1990;9:701–716. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.9.6.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Parks GA, Marlatt GA. Social determinants of alcohol consumption: The effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:189–200. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins S, Carey K, Sliwinski M. Mailed personalized normative feedback as a brief intervention for at risk college drinkers. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63:559–567. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darke S. Self-report among injecting drug users: A review. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1998;51:253–263. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00028-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsberg L, Halldin J, Wennberg P. Psychometric properties and factor structure of the readiness to change questionnaire. Alcohol & Alcoholism. 2003;38(3):276–280. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agg067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromme K, Corbin W. Prevention of heavy drinking and associated negative consequences among mandated and voluntary college students. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:1038–1049. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heather N, Rollnick S. Readiness to change questionnaire: User’s manual. Sydney: National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hingson R, Heeren T, Winter M, Wechsler H. Magnitude of alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18–24: Changes from 1998 to 2001. Annual Review of Public Health. 2005;26:259–279. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Cronce JM, Lee CM, Kilmer JR. Brief intervention in college settings. Alcohol, Health, and Research. 2004/2005;28:94–104. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little RJA. A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. Journal of American Statistical Association. 1988;83:1198–1202. [Google Scholar]

- Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical analysis with missing data. Wiley & Sons; New York: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt GA, Baer JS, Kivlahan DR, Dimeff LA, Larimer ME, Quigley LA, et al. Screening and brief intervention for high-risk college student drinkers: Results from a 2-year follow-up assessment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:604–615. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.4.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAuliffe WE, Geller S, LaBrie R, Paletz S, Fournier E. Are telephone surveys suitable for studying substance abuse? Cost, administration, coverage and response rate issues. Journal of Drug Issues. 1998;28:455–484. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Toscova RT, Miller JH, Sanchez V. A theory based motivational approach for reducing alcohol/drug problems in college. Health Education and Behavior. 2000;27:744–759. doi: 10.1177/109019810002700609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, Duchnick JJ, Vuchinich RE, Davison JW, Karg RS, Olson AM, et al. Relative efficacy of a brief motivational intervention for college student drinkers. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2001;15:373–379. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.15.4.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Larimer ME, Lewis MA. Targeting misperceptions of descriptive drinking norms: Efficacy of a computer delivered personalized normative feedback intervention. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:434–447. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins HW. Surveying the damage: A review of research on consequences of alcohol misuse in college populations. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;14:91–100. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrie R, Fleming C, Haggerty K, Catalano Harachi T, Brown E. Asking 18 year olds about sex and drugs: A comparison of web and in-person survey modes. Poster presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Prevention Research; Washington, DC. 2005. May, [Google Scholar]

- Presley CA, Meilman PW, Cashin JR. Alcohol and drugs on American campuses: Use, consequences, and perceptions of the campus environment. Vol. 4. Carbondale, IL: CORE Institute, Southern Illinois University; 1996. pp. 1992–1994. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush S, Bryk A, Congdon R. Hierarchical linear and nonlinear modeling (Version 6.02) [Computer software] Chicago, IL: Scientific Software International, Inc; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute. SAS for Windows (Version 9.1) [Computer software] Cary, NC: SAS Institute; 2002–2006. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL. Analysis of incomplete multivariate data. New York: Chapman & Hall; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Tamhane AC, Dunlop DD. Statistics and data analysis from elementary to intermediate. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Walters ST, Neighbors C. Feedback interventions for college alcohol misuse: What, why and for whom? Addictive Behaviors. 2005;30:1168–1182. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Lee JE, Kuo M, Lee H. College binge drinking in the 1990s: A continuing problem: Results of the Harvard School of Public Health 1999 College Alcohol Study. Journal of American College Health. 2000;48:199–210. doi: 10.1080/07448480009599305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Lee JE, Kuo M, Seibring M, Nelson T, Lee H. Trends in college binge drinking during a period of increased prevention efforts: Findings from 4 Harvard School of Public Health College Alcohol Study surveys: 1993–2001. Journal of American College Health. 2002;50:203–217. doi: 10.1080/07448480209595713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR. Reduction of alcohol-related harm on United States college campuses: The use of personal feedback interventions. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2006;17:310–319. [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Filstead WJ, Labouvie EW, Conlin J, Pandina RJ. Assessing alcohol problems in clinical and nonclinical adolescent populations [Abstract] Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1988;12:328. [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Labouvie EW. Toward the assessment of adolescent problem drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1989;50:30–37. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1989.50.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Labouvie EW. Longitudinal trends in problem drinking as measured by the Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index [Abstract] Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research. 2000;24:76A. [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Morgan TJ, Pugh LA, Celinska K, Labouvie EW, Pandina RJ. Evaluating two brief personal substance use interventions for mandated college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67:309–317. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Mun EY, Pugh L, Morgan TJ. Long-term effects of brief substance use interventions for mandated college students: Sleeper effects of an in-person personal feedback intervention. Alcoholism Clinical and Experimental Research. 2007;31(8):1380–1391. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widmark E. In: Principles and applications of mediocolegal alcohol determination. Baselt RC, editor. Biomedical Publications, University of California; Davis: 1932. 1981. [Google Scholar]