Much has been written about Dr. William Stewart Halsted, considered one of the greatest and most influential surgeons of all time (Figure 1). Halsted was born in 1852 in New York City, the son of a wealthy dry goods importer, and lived on Fifth Avenue. Upon graduation from Andover, Yale, and the Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, he trained in New York and spent 2 years in Europe studying anatomy and embryology.

Figure 1.

Dr. William Stewart Halsted (portrait by Stocksdale). Reprinted with permission of the Alan Mason Chesney Medical Archives of The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions.

In 1880, he began the private practice of surgery. He was very busy, operating at multiple hospitals, and also taught anatomy. In 1884, he became an “accidental addict.” He was impressed by a report by Dr. Carl Keller at a conference in Heidelberg, Germany, on the successful use of cocaine for anesthesia of the eye. Halsted and several colleagues and medical students in New York City began a series of experiments on themselves. The results, which led to the development of local and regional anesthesia, were published by Halsted in 1885.

Unfortunately, Halsted became addicted and in 1885 was approached by his good friend, Dr. William Henry Welch, who was then a pathologist at Bellevue Hospital. A treatment plan proposed by Welch consisted of a sea trip to the Windward Islands but failed. Halsted then admitted himself to the Butler Hospital in Providence, Rhode Island, and was treated by substituting morphine for cocaine.

In late 1886, Halsted was invited by Welch to move to Baltimore and live with him and work in his laboratory while the new Johns Hopkins Hospital was being constructed. (Welch had recently been appointed professor of pathology.) Halsted worked diligently in the lab along with associates Franklin Mall and William Councilman, testing surgical techniques and doing investigations on dogs. A few months later, Halsted readmitted himself to the Butler Hospital for further treatment for 9 months.

Halsted returned to Baltimore in early 1888, and, after the endorsements of Welch and Osler to the trustees, was later appointed surgeon in chief to The Johns Hopkins dispensary and acting surgeon at the hospital for 1 year. The hospital officially opened in 1889 and Halsted was named surgeon in chief in 1890 and finally professor of surgery in 1892.

Dr. William F. Rienhoff Jr., who was the last surgical resident of Dr. Halsted, entered Johns Hopkins in 1910 as a medical student and later became a well-known professor of surgery at Hopkins. Dr. Rienhoff produced an interesting manuscript of his personal reminiscences from 1915 to 1960. In this, he discussed Halsted's principles of surgical technique, advising surgical students to “handle tissues with great care, avoiding interruption of the circulation, and closing the incision carefully and gently, layer by layer, the sutures thus avoiding tension which might interfere with the blood supply.” Further, the “end of the forceps should be small to avoid crushing surrounding tissue” and a drain was “essential where there is necrotic tissue and infection.” Rienhoff stated, “These lessons to us as third and fourth year medical students were constantly drilled into us.”

Halsted's addiction to morphine continued, and his personality changed as he became more reclusive. Nevertheless, it is amazing and somewhat miraculous that he was able to continue as the chief of surgery at Hopkins for 30 more years until his death in 1922. His creative genius led to numerous innovations and contributions to surgery, some of which are listed in the Table.

Table.

Halsted's innovations and contributions to surgery

| 1. | As a medical student, invented a traction apparatus for neck fractures. |

| 2. | As a resident, was responsible for the inclusion of temperature charts in the medical record. |

| 3. | In 1881, performed the first emergency blood transfusion (on his sister) and one of the first operations for gallstones (on his mother). |

| 4. | Was the first to use cocaine for local and regional anesthesia and also the first to demonstrate spinal anesthesia. This discovery later greatly enlarged the scope of dentistry. |

| 5. | Was the first to promote “safe surgery” (asepsis, careful handling of tissues, hemostasis, and introduction of fine silk sutures and delicate forceps). |

| 6. | Developed new operations for intestinal, stomach, gallbladder, thyroid, hernia, and breast surgery. Also signalled advances in vascular surgery (first to excise a subclavian aneurysm). |

| 7. | Promoted rubber gloves for scrub nurse Caroline (see discussion in article). |

| 8. | Was the first to use plate and screw techniques with burial screws for long bone fractures. |

| 9. | Most importantly, was the first in the USA to develop a “school of surgery”: a rigorous training program for young surgeons. His department of surgery established four subspecialties: otolaryngology, urology, orthopedics, and neurosurgery. Seven of his residents became professors of surgery. |

Dr. Halsted worked with Dr. Franklin Mall, professor of anatomy in the Hunterian Laboratory of Experimental Medicine. In their surgery on dogs, they focused on intestinal anastomosis. Halsted favored fine silk sutures and was the first to show that the submucous layer was the strong layer of the intestine.

Dr. Rienhoff was of the opinion that Halsted's “addiction to cocaine was a great assistance to him in his experimental and clinical studies.” His withdrawal from the pressures of his previous busy life in New York City gave him “leisure to think and develop powers within himself that otherwise may have lain dormant.” Voiced this way, his accidental cocaine addiction was a “blessing.”

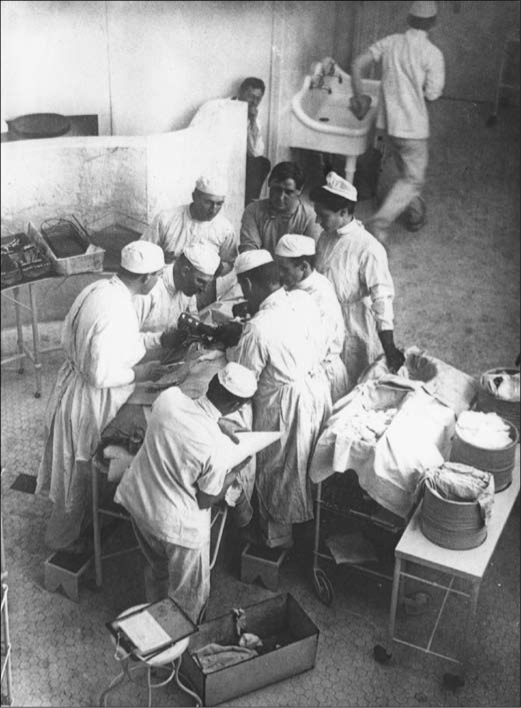

Halsted was said to be a “very meticulous” operator but was a “head surgeon, not a hand surgeon,” according to his close associate Dr. John M. T. Finney. Halsted selected his house officers with great care and made his school of surgery distinctive, training his young men in every technical detail to make surgery a safer form of therapy (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

All-star operation in 1904 by Dr. Halsted and his colleagues. Reprinted with permission of the Alan Mason Chesney Medical Archives of The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions. Next to Dr. Halsted are Dr. Joseph Bloodgood, Dr. Hugh Young, and Dr. Harvey Cushing. Directly across from Dr. Halsted is Dr. John M. T. Finney. Dr. Frank Mitchell administered ether anesthesia.

DOMESTIC LIFE

In 1890, Dr. Halsted married Caroline Hampton, the niece of famed Confederate General Wade Hampton III (later a South Carolina governor and US senator). It was a merger of the wealthy merchant class of the North with the planter aristocracy of the South. Caroline's mother, Sally Baxter Hampton, was a leader in New York society and was courted by many eligible men, including William Makepeace Thackeray.

In 1855, Sally married Frank Hampton, the younger brother of Wade Hampton III. Unfortunately, Sally died prematurely in 1862 of tuberculosis at the age of 29 and Frank was killed 9 months later at the Battle of Brandy Station in Virginia. Caroline was raised by her three aunts (Caroline, Anne, and Katie Hampton) in a small house behind the ruins of Millwood, General Hampton's plantation home, which had been burned by Union troops.

In 1885, Caroline surprised her family by moving to New York City to enter nursing school, graduating from New York Hospital in 1888. When The Johns Hopkins Hospital opened the following year, Dr. William Halsted appointed her chief nurse of the operating room, and she became his scrub nurse. When her sensitive hands and arms could not tolerate mercuric chloride disinfectant, she developed a contact dermatitis. Halsted requested the Goodyear Rubber Company to make two pairs of rubber gloves to protect her hands. This marked the beginning of the use of rubber gloves in the operating room in this country. (Thus Caroline was the first medical professional to wear them.)

In 1890, Halsted and Caroline were married at Trinity Episcopal Church in Columbia, South Carolina. Dr. William Welch was best man, and the newlyweds honeymooned at the Hampton Hunting Lodge in Cashiers, North Carolina. Dr. Halsted became enthralled with the beauty of the Hampton estate and realized it would be a retreat from the heat and humidity of the Baltimore summers. From 1892 to 1893, he purchased over 400 acres from Caroline's aunts and called the property “High Hampton,” a name that combined the two families, as the Halsted estate in England had been called “High Halsted.” Later, the Halsteds built a cottage and a guest house (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The Halsted cottage at High Hampton. Reprinted with permission of the Alan Mason Chesney Medical Archives of The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions.

Thereafter, Dr. Halsted typically left Baltimore around June 1 and returned around October 1. Mrs. Halsted, who generally arrived in May and stayed until Thanksgiving, literally ran the farm, directed the hired hands, and supervised the planting of the garden and crops. She preferred the outdoor life at High Hampton to the social amenities of Baltimore. In fact, she loved animals and especially horses. She was a very skilled rider and was known for her horsemanship (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Caroline Hampton Halsted loved to drive her buggy with her dogs. Reprinted with permission of the Alan Mason Chesney Medical Archives of The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions.

HIGH HAMPTON

Dr. Halsted gradually bought out the adjacent small farms for approximately $5 an acre, and the estate grew from 400 to around 2200 acres. High Hampton was an ideal retreat for Halsted, who loved solitude. He once wrote Dr. Harvey Cushing, who at the time was his chief resident, explaining how to get messages to him: “by telegram to Hendersonville, by telephone to Brevard, then to Sapphire, and finally by horseback to Cashiers.”

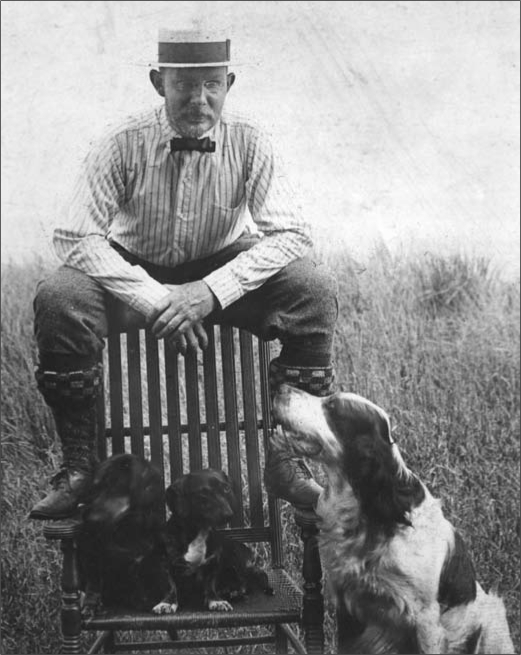

Dr. and Mrs. Halsted raised a superb collection of prized dahlias and planted many unusual trees. He pursued his hobby of astronomy. The Halsteds always had good horses, cattle, and a number of dogs (who usually slept with the family) (Figure 5). Caroline carried her two favorite dachshunds, Nip and Tuck, everywhere in a wicker basket.

Figure 5.

Halsted, dressed impeccably, with some of his dogs at High Hampton. Reprinted with permission of the Alan Mason Chesney Medical Archives of The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions.

The Halsteds were described as opposites in appearance. “He was a dandy, garbed in European tailored suits and Parisian cobbled boots, who dressed impeccably, even sending his dress shirts to Paris to be laundered.” Mrs. Halsted's style was described as “plain and austere.” Nevertheless, the couple were remarkably well suited to each other, each being reserved and self-sufficient and described by others as “socially aloof” and somewhat “eccentric.”

Osler commented about Halsted: “He married a woman after his own heart…. They were well matched—had no family, cared nothing for society but were devoted to their dogs and horses, and especially to each other.”

Caroline and Halsted took a great deal of interest in their mountain neighbors who depended on Dr. Halsted (probably the first physician in Cashiers) for their medical needs. They respected him greatly, and he sent a good number to The Johns Hopkins Hospital, frequently paying their expenses. Halsted's medical advice was also sought by members of the Hampton family in South Carolina.

On November 10, 1921, Dr. Halsted wrote to a neighbor's husband in the Cashiers vicinity:

Your letter has just arrived. I am very sorry to learn that your wife is in such trouble. Should she come to the Johns Hopkins Hospital it will give me pleasure to place her in the best hands and do what I can to make her sojourn here a pleasant one. I will speak to the Superintendent, explaining the situation, in the hope that he may be able to reduce the price for her board. The regular price per week for a bed in the ward is $20.

And one week later (November 18, 1921), Halsted wrote to the patient:

I regret that it is impossible for me to tell you what the nature of the operation is likely to be, but I presume from what the doctors have told you that you have nothing very serious…. Whatever it may be necessary to do, there will be no charge for the operation. The charter of the hospital does not permit us to admit free patients from outside of the state of Maryland. In the case of [another patient], I succeeded in having the price reduced to $10 per week. If you can meet this expense, kindly let me know.

Halsted frequently spent part of his sojourn from Hopkins at medical meetings in Europe. He was usually very modest about his accomplishments but in 1914 wrote to his sister Bertie (Mrs. John T. Terry Jr.) in New York City about an honor he received in Berlin. On April 20, 1914, he wrote the following letter:

Dearest Bertie,

I am set to sail tomorrow morning by the Kaiser Wilhelm II…. Have had a wonderful week, attending the Congress of German Surgeons and reading a paper.

I nearly collapsed at the meeting 3 days ago on hearing my name proposed for the highest honor that it is possible for a surgeon to receive…. My name was proposed for Ehrenliebglied. There are only 8 Ehrenliebgliedes of the German Surgical Association. Of these Lister is one…. Have had to reply almost every evening in German to a toast … and this was pretty trying…. It is a sign of old age that I have to write and tell you all this.

Devotedly,

Billy

And then on July 26, 1914, another letter from London (Savoy Hotel) to his sister:

Darling Bertie,

… I am about to send you a photograph taken at Professor Kocher's Clinic at Berne at the close of an operation which I was performing upon an old woman for the case of an aneurysm of the aorta…. I have declined an invitation to a banquet given by the English members of the International Society of Urology, which is now holding in London its second triennial Congress. Dr. Hugh Hampton Young, associate professor of genito-urinary surgery at the J.H.U. and one of the members of my staff in whom I take the greatest pride, has carried off all the honors of this meeting, I am told. I was quite sure he would, for he is easily the first man in America in his specialty, and possibly has no peer in his line in the world…. Yesterday Osler [Sir William Osler] came down from Oxford to see me and gave me a nice luncheon at the Automobile Club. Young and his wife were also present. I hope to go to Oxford tomorrow to pay my respects to Lady Osler.

At High Hampton, Caroline's days were very active. She worked in the fields with the hired hands from morning till night. Halsted was very proud of her farming work and wrote several letters from Baltimore during the winter to Douglas Bradley, caretaker at High Hampton. His letters (probably based on suggestions by Caroline) gave specific orders for planting crops, cutting wood, and purchasing animals, etc. Halsted also ordered supplies locally and assisted in hiring servants. On January 7, 1920, Dr. Halsted wrote to Douglas Bradley in Cashiers:

Mrs. Halsted asked me to send you the enclosed check and to say she would like to have you arrange for the cutting of 20 or 25 cords of firewood. This, as you know, should be red oak or chestnut oak or hickory; we do not like white oak for the open fires. You will, I suppose, have it cut in 8 foot lengths, and later saw these up at the mill.

I hope you are well. Please remember me to Della and the children.

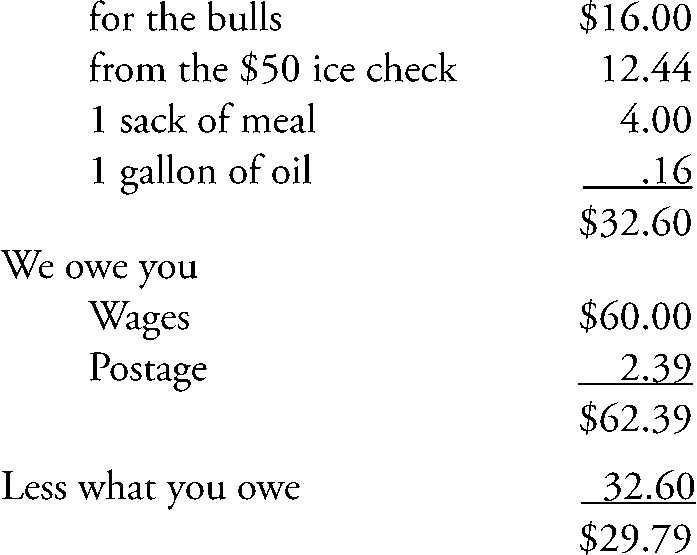

And on February 7, 1920, Halsted wrote to Douglas Bradley:

I am pleased to receive your letter and to know that all is going well at High Hampton and that you and Della and the children are all in good health.

As I understand the account you have sent me you owe us

In 1919, Halsted underwent gallbladder surgery at Hopkins with temporary relief of his abdominal and chest pains. However, in 1922, he developed jaundice and returned to Baltimore for removal of another common duct stone. Postoperative complications occurred, and he died on September 7, 1922.

Eleven days later, Caroline Halsted wrote from 1201 Eutaw Place in Baltimore.

Dear Dr. Welch,

It is hard for me to tell you how much I appreciate all that you have done and are doing for me…. There seems, to me, an overwhelming amount of work to be done…. I need to get some idea as to what the university wishes done with the books, papers etc….

I sometimes wonder if you have any idea of the great love and admiration that Dr. Halsted had for you. He never mentioned you without praise. He often said “Welch is the Johns Hopkins. Without him it would be nothing. He has been the best friend to me that any man could ever be.”

Very sincerely yours,

Caroline H. Halsted

On October 13, 1922, Dr. Welch replied to Caroline:

Dear Mrs. Halsted,

I have received [your letter and later] the mementoes of Dr. Halsted, and am delighted to have them. It is very kind and thoughtful of you to select the souvenirs, which I shall cherish in memory of my dearest friend and comrade of over forty years…. I am temporarily laid up with an attack of gout, but I hope that before long Dr. MacCallum and I can look over Dr. Halsted's books and papers. I understand you are eager to have all such matters looked after and settled as soon as possible. I hope you know how completely I reciprocated Dr. Halsted's feelings of affection. I admired him above all my colleagues. There is no one who can fill his place as he did. The memory of his wonderful character and life and devotion must be your most precious possession….

With most cordial regard and best wishes, I am

Very sincerely yours,

William H. Welch

Caroline Halsted was mentally and physically exhausted after her loss and died of pneumonia on November 27, 1922, less than 3 months after Dr. Halsted.

An editorial in the Baltimore Sun on September 8, 1922 (the day after Halsted's death) stated:

Because Dr. William S. Halsted lived, the world is a better, a safer, a happier place in which to be…. He was one of the few men who really count. Quiet, simple, unostentatious except in the medical world, where he towered, the full scale of his genius and the tremendous extent and value of his services to mankind were neither generally known nor generally appreciated.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank Ms. Marjorie Kehoe for her outstanding help and support from the Alan Mason Chesney Medical Archives of The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions. I am also especially grateful to Ms. Cynthia Orticio for her expert technical assistance in preparing the manuscript.

SELECTED REFERENCES

- 1.MacCallum WG. William Stewart Halsted: Surgeon. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 1930. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Osler W, Bates DG, Bensley EH. The inner history of the Johns Hopkins Hospital. Johns Hopkins Med J. 1969;125(4):184–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crowe SJ. Halsted of Johns Hopkins. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Penfield W. Halsted of Johns Hopkins. JAMA. 1969;210(12):2214–2218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nunn DB. The Halsteds. The professor and Caroline. J Fla Med Assoc. 1991;78(4):233–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cameron JL. William Stewart Halsted. Our surgical heritage. Ann Surg. 1997;225(5):445–458. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199705000-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nunn DB. Caroline Hampton Halsted, an eccentric but well matched helpmate. Perspect Biol Med. 1998;42(1):83–94. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nunn DB. Dr. Halsted's addiction. Johns Hopkins Advanced Studies in Medicine. 2006;6(3):106–108. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rankin JS. William Stewart Halsted: a lecture by Dr. Peter D. Olch. Ann Surg. 2006;243(3):418–425. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000201546.94163.00. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Correspondence between William Halsted and Douglas Bradley, 1913 to 1921 Box 11, folder 6, Halsted Papers, the Alan Mason Chesney Medical Archives of The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions, Baltimore, Maryland. Hereafter referred to as Halsted Papers, JHMI.

- 11.William Halsted to his sister Bertie (Mrs. John T. Terry Jr.) in New York City, April 20, 1914, and July 26, 1914. Box 63a, folder “Family,” Halsted Papers, JHMI.

- 12.Caroline Halsted to William Henry Welch, September 18, 1922. Box 23, folder 30, Halsted Papers, JHMI.

- 13.William Henry Welch to Caroline Halsted, October 13, 1922. Box 23, folder 30, Halsted Papers, JHMI.

- 14.Rienhoff WF Jr. Personal reminiscences of The Johns Hopkins Medical School and the Johns Hopkins Surgical Service 1915–1960 Unpublished manuscript, circa 1977, the Alan Mason Chesney Medical Archives of The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions, Baltimore, Maryland.