Abstract

Compared with other developed countries, the United States has an inefficient and expensive health care system with poor outcomes and many citizens who are denied access.

Inefficiency is increased by the lack of an integrated system that could promote an optimal mix of personal medical care and population health measures. We advocate a health trust system to provide core medical benefits to every American, while improving efficiency and reducing redundancy.

The major innovation of this plan would be to incorporate existing private health insurance plans in a national system that rebalances health care spending between personal and population health services and directs spending to investments with the greatest long-run returns.

THE UNITED STATES HAS THE most technologically intensive medical practice in the world.1 It also spends more than any other nation on medical care,2 but health outcomes in the United States are inferior to those in most other developed nations.3–7 This inefficiency—spending more with poorer results—stems partly from failure to provide effective access to medical care to a substantial share of the population.8,9 Lack of access leads to wider disparities in health in the United States than are experienced by the populations of other developed nations. The fragmented delivery system also leads to cost shifting (insurers' attempts to transfer costs to other payers), administrative waste, and an imbalance between spending on medical care and spending on population health initiatives.

There is general agreement that the US health care system should be more efficient as well as more equitable.10,11 Most comprehensive proposals for reforming the system recognize the need for universal coverage that is independent of employment status, disability status, or age, although some would continue to rely on employers to collect health insurance payments.12 Although universal insurance is important, it is not the only urgent issue. A reformed system should integrate personal preventive and therapeutic care with public health and should include population-wide health initiatives. Coordinating personal medical care with population health will require a more structured system than has ever existed in the United States.

We argue that a reformed health care system not only should provide health insurance coverage for all but should also be organized and funded to take advantage of new knowledge about medical and nonmedical determinants of health. This health trust system (HTS) would (1) assess the cost of health insurance equitably, (2) promote efficiency by reducing fragmentation and relying on competitive markets, (3) allow coordination of spending on population health and personal medical care, (4) accommodate heterogeneous preferences, and (5) build on existing American health insurance and provider institutions, informed by international experience.

UNDERINVESTMENT IN PUBLIC HEALTH

Underinvestment in preventive care and population health persists in the United States despite the growing evidence that such investments have great potential to improve health.13–17 High rates of return have been demonstrated for community-level interventions to reduce the high-risk behaviors that promote chronic diseases, which account for two thirds of all deaths in the United States and a higher percentage of deaths among the most disadvantaged groups.5,18 These chronic diseases are often associated with high-risk lifestyle consumption choices (smoking, drinking, and poor diet), which may be more effectively averted by policy interventions in the community and early in the life course than altered by later interventions within the medical care sector.5 For example, 2 structural interventions in California—levying a cigarette tax and banning indoor smoking in public places—resulted in dramatic declines in smoking, followed by declines in the rates of lung cancer and heart disease in the state.19 Disadvantaged populations, which bear the greatest burden of chronic disease, stand to benefit most from public and population health interventions.

The current financing structure and organization of care in the United States provide strong incentives to treat illness after it occurs rather than to invest in prevention. Health insurance policies also encourage a suboptimal mix of services, relying on expensive, and often redundant, technology, with inadequate coverage for preventive care. The fragmented health care financing system also wastes resources through cost shifting and excessive administrative costs.20

To create a more effective and efficient health care system, the United States should capitalize on current health reform efforts that aim to make access to care universal and contain its costs within an integrated health system. This will require redesigning the system to allocate resources to therapeutic care and to population health in a balance that more closely reflects their abilities to promote health and thereby increases the health returns generated by health expenditures.

ARCHITECTURE OF AN INTEGRATED HEALTH SYSTEM

In addition to providing universal access and equitable funding, a reformed health system should strive to (1) increase efficiency by formulating coherent policy with appropriate incentives, information, and supporting infrastructure; (2) foster coordination of public, population, and private health care at the local level; (3) impose financial discipline, or cost containment; and (4) encourage choice for, and responsiveness to, clients.

We propose a health system consisting of a national independent body, a national health trust (NHT), which would coordinate regional- or state-based affiliates— regional health trusts (RHTs)— and which would form a coherent national structure to ensure orderly and efficient operation.

National Health Trust

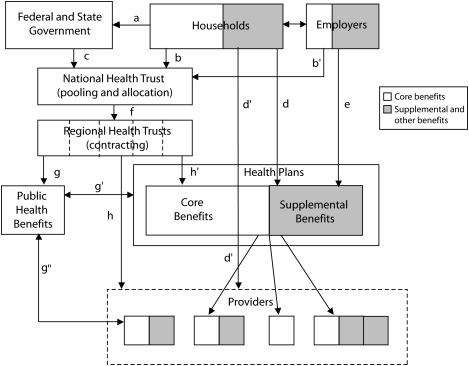

The proposed structure and operations of an NHT are summarized in Figure 1. Households would pay taxes to federal or state governments to support health services. Households would also make direct, mandatory payments to the NHT to support health care, similar to payroll taxes that support the Social Security system or the payment Medicare currently requires for enrollment in Part B coverage. These contributions might be collected by employers along with their own potential contributions on behalf of employees, but employers would no longer offer insurance for core benefits. Rather, all residents would select a health plan or physician through their regional insurance exchange. All tax-based and mandatory contributions would be pooled by the NHT into a global budget for health spending. The NHT would retain some funds for national health policy activities and allocate the majority to RHTs.

FIGURE 1.

Architecture of a restructured health care system.

Note. a = household general taxes; b = household mandatory contribution to the National Health Trust (NHT); c = government funds to the NHT; d = household contribution to supplemental benefits; d′ = household direct purchasing of medical services; e = employer contribution to supplemental benefits; f = Regional Health Trust (RHT) allocation for core benefits; g = RHT allocation for population health initiative; g′ = RHT funding and coordination of population health initiatives with plans; g″ = RHT funding and coordination of population health initiatives with providers; h = RHT direct purchase of services; h′ = RHT indirect contracting of service.

The size of the global budget for health, the means of funding it, and decisions about who is eligible for personal health benefits would be determined through the political process. Several mechanisms have been proposed for more equitable financing of the system: payroll taxes, income taxes, or value-added taxes.6,7,21,22 A reformed system might include a variety of funding strategies, similar to the current Medicare system, which is funded by payroll taxes, general revenues, and subscriber contributions.

An NHT would use risk-adjusted capitations to allocate funding to RHTs, which would direct funding to personal care and population health activities in their regions. This would ensure that funding for health services would be responsive to the needs of populations living in different regions as well as taking into account the available medical infrastructure and manpower. In addition to adjusting for health risks, the capitation mechanism would have to take into account the differential costs of delivering medical care in various regions of the country, through mechanisms similar to those the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services has developed for Medicare inpatient and outpatient services. Different populations could thus be afforded equal opportunities to realize their health potential.

An NHT would also have responsibility for developing uniform national policies to promote information technology, assist with the adoption of new medical technology, define criteria for high-quality care for particular diseases, conduct comparative effectiveness analyses, and forecast future health manpower needs.23 It would also update and improve risk adjustment tools to ensure fair allocations to RHTs and for use in allocating capitation-based payments to health plans to prevent risk selection.

Regional Health Trusts

RHTs would be responsible for organizing, managing, and overseeing the delivery of the core benefits: personal care combined with population health interventions. However, RHTs would not become providers of services; rather, an RHT would contract for services either directly with providers or indirectly through integrated plans and would also finance population and public health initiatives.

The proposed system would accommodate the population's heterogeneous preferences by allowing households and employers to purchase voluntary insurance for supplemental benefits not included among the core benefits or to pay out of pocket directly to providers for noncovered services. These supplemental benefits would not be financed with pooled, RHT funding.

Thus, an RHT would operate much like a health insurance exchange or the Federal Employees Health Benefit Plan (FEHBP). The FEHBP, which has been put forward as a model in several prominent reform proposals,5,7,24 is funded by the government in its capacity as an employer. Premium levels of the offered health plans vary, but the federal government makes a defined contribution to any plan chosen, with the employee paying the additional cost of more expensive plans.25

RHTs would employ quality standards developed by the NHT to evaluate quality of care and make this information available to consumers to facilitate selecting providers or plans. RHTs could monitor quality of care at the patient level, tracking patients by their unique insurance identifier. They could also use health information technology, which can improve both quality of care and productivity, as the Veterans Affairs hospitals have shown.26,27

Information technology systems would also play a key role in monitoring population health by allowing RHTs to aggregate data across numerous health care providers to implement routine data collection for population health surveillance, which is difficult in the current fragmented delivery system. This surveillance would facilitate improved targeting of population health interventions and efforts to reduce disparities across subregions by allowing RHTs to direct health resources to areas that lag behind in health outcomes. Adoption of health information technology in the United States has been limited because the current market-based approach requires health organizations to fund their own health information technology operations.28 RHTs would invest in health information technology as a public good.

The FEHBP and most of the reform proposals under discussion lack 1 element that is crucial for a reformed health care system: a mechanism to balance resources for public and population health with those devoted to personal medical services. A key innovation in an HTS would be that RHTs would not allocate all of their funding for the delivery of personal medical services but would also finance health interventions at a population level, coordinating these with health plans.

Giving RHTs control of health financing within their geographic area would allow them to consider the trade-offs between the 2 types of care so that they could allocate their available funding to maximize health in the population. For example, an RHT might prefer to finance population-based interventions to reduce the future incidence of type 2 diabetes among adults at risk for the disease rather than interventions delivered in the medical setting, because the literature shows that lifestyle interventions are more successful as well as more cost effective.29,30

Recognizing the effect of factors outside of the medical care system and incorporating them into an overall plan would result in greater health gains from a given investment. RHTs would also contribute to population health by assessing the health effects of activities outside of the health care sector (e.g., road building, the built environment, waste disposal). An RHT, with responsibility for the health of all residents in a geographic area, could more readily implement health impact assessments than has been the case to date, to provide the public with information about the external costs or benefits to health likely to result from public decisions in nonhealth areas.31

Contracting.

RHTs could fulfill their mission of securing publicly funded core medical benefits for their constituents either by paying individual providers or provider groups directly (as Medicare does for the majority of its enrollees) or by contracting with integrated health plans (e.g., Medicare Advantage) to deliver services. For-profit or nonprofit plans would contract with individual providers or groups to supply core benefits to their members. A mixed system, such as the building blocks system proposed by Schoen, Davis, and Collins,32 would also be feasible. Regardless of the contracting arrangements, individual providers and plans affiliated with an RHT would be required to maintain open enrollment and to accept all residents wishing to enroll, subject to limits set by the RHT. Risk adjustment of the capitation would counteract providers' incentive to enroll only applicants who appear to be low risk.

An RHT could contract for and coordinate population health initiatives with plans, providers, and local government agencies. It is conceivable, for instance, that an RHT would contract directly with competing plans for personal care but contract directly with private providers or local government agencies to implement population health initiatives that involve economies of scale and have population-wide effects.

Organization and management.

The 2 alternative contracting arrangements would allow for different amounts of decentralization of management and risk holding.33 Integrated plans would assume the fiduciary role of controlling costs to stay within their contractual capitation and might find it profitable to invest in prevention and population health. In Israel, for example, competing health plans see preventive services as a means of attracting younger subscribers, who are considered good risks.

By contrast, individual medical providers could supply personal preventive care (e.g., immunizations), but they could not assume wide-ranging responsibilities for health behavior changes requiring mass communication efforts. Thus, direct contracting with providers would leave RHTs with the major responsibility for controlling costs and financing preventive and population health initiatives.

Quality of care.

Although RHTs would retain the final responsibility for monitoring quality of care, this obligation could be shared with accountable health plans.34 Direct contracting with individual providers would vest an RHT with greater responsibility for overseeing and coordinating treatment, because it alone would have a comprehensive view of all the services delivered. Yet an RHT, which would be primarily limited to retrospective review, might find it difficult to intervene directly. The Medicare experience suggests that it is difficult to avoid duplication of services, to coordinate care for individual patients, and to effectively monitor quality in a system that contracts and compensates providers individually.35,36 Unlike RHTs, integrated health plans would both provide services and remain accountable to their members, who would need to be satisfied in a competitive environment; thus they could exercise oversight more effectively.

Compared with fee-for-service providers, capitated providers have been found to provide more clinical preventive care, which can reduce long-term costs and thereby promote the long-term goals of RHTs.37 For similar reasons, integrated systems might also more effectively partner with the population health initiatives of RHTs.

Finally, integrated systems can more readily benefit from economies of scale by sharing administrative and expert staff, equipment, and specialized facilities. Integrated systems such as Kaiser Permanente or Veterans Affairs are also more likely to use electronic medical records and advanced health information technology to promote care quality.38

ADVANTAGES AND SAFEGUARDS IN A HEALTH TRUST SYSTEM

Most of the political discussion of health care reform in the United States has centered on the crisis in health care costs and the related lack of access to quality medical care. These important issues are, however, part of a larger problem: the current inability of the United States to care for the health for its population efficiently because it lacks a coherent system for financing and providing medical care as well as a mechanism for allocating resources both to medical care for individuals and to public and population health initiatives. Our proposal would create a logical, nested organization that would build on the foundations of the current US health care system.

Our proposed structure would have several fundamental advantages. It could ensure that health spending would be targeted to its most productive uses and that decision makers could take a more appropriate long-term perspective on the health of Americans by investing now in prevention and health promotion, while also providing medical care equitably to all Americans. Such a system would reduce billing costs and administrative waste by eliminating medical underwriting, duplicate coverage, and cost shifting. In addition, the rebalancing of personal and population health initiatives and the development and dissemination of information on the constituents of cost-effective health care would act to control costs.

Universality

The proposed HTS promises every American a portable, basic package of core benefits, independent of employment status, which would comprise personal and population services for prevention and treatment. This HTS would mainstream the care of low-income persons currently enrolled in categorical programs for people with particular characteristics, such as Medicaid for the disabled, the State Children's Insurance Program for children, or Ryan White Care Act programs for treatment of HIV/AIDS. Under an HTS, a voucher would support enrollment of the categorically eligible in any plan offered in their area, thereby expanding their choice of providers. Plans' incentives to favor low-risk applicants would be mitigated by receipt of a risk-adjusted capitation payment that would be independent of the enrollee contribution.

Universality does not imply uniform care, either in content or in form. In an HTS, individuals would have a greater choice of providers than is currently available to most Americans. Although everyone would be guaranteed the same core benefits, individuals could satisfy diverse preferences by supplementing the core benefits with their personal funds, within the same health system, much as FEHBP enrollees currently do. Although this arrangement may raise the specter of a 2-tiered system, supplementation has not been a major issue in the FEHBP. Some individuals now have benefits that exceed the core benefits that can be provided universally. Allowing them to supplement the core benefit package and keep their current health insurance if they prefer it may be necessary for political acceptability.

The organization of health coverage in the Netherlands provides a prototype for the type of system we advocate. Dutch residents receive a risk-adjusted voucher for a basic benefit package, purchased from competing insurers. They can supplement the core benefits through their own resources or funding from their employer. The Netherlands combats risk segmentation by compensating plans with highly developed risk-adjusted capitation payments.39

Governance

An HTS would finance universal coverage through mandated contributions but would rely on private providers to supply medical care. It would not resemble socialized medicine. The federal government would in fact remain distant from the organization and management of the system, let alone the management and provision of care. However, to ensure that plans assume a fiduciary role on behalf of the public, the NHT and RHTs would have to carefully monitor that health plans are providing appropriate care and not engaging in risk selection.

The basic nature of US health care provision would remain intact, and all Americans enrolled in an insurance plan of any type could continue to receive care in the same manner they receive it today, although funding sources would change. The proposed plan would rely heavily on private, nongovernmental entities to insure the core benefits as well as to offer supplemental insurance. Specialized government-run programs such as Medicare and Medicaid could remain in place and function as health plans, at least in the near term.

Proponents of a single-payer system argue that eliminating private health insurance altogether would further reduce administrative costs to levels achieved in Medicare (2%–3%).40 In the current US private health insurance system, administrative costs account for 20% to 25% of premiums, which may reflect such practices as medical underwriting and separate contracts with multiple employers, neither of which would be a factor in the proposed HTS.20 Switzerland's national health insurance is delivered by competing private plans, with administrative costs of approximately 6%.41 When Israel enacted its national health insurance program in 1995, the costs of collecting premiums fell by 75%.42

Health Promotion and Cost Control

An HTS would promote health and increase the efficiency of the health system in 3 important ways. First, RHTs could rebalance spending on personal medical care and on public and population health initiatives because they would allocate the budgets for both sets of activities and could monitor the yield in health benefits per dollar spent. By overcoming the fragmentation of the current employer-based system, RHTs could effectively coordinate personal care and population health spending. An NHT would provide the information base that RHTs would need to allocate funding between the sectors effectively.

Second, the goal of optimizing lifetime health is currently overpowered by the short planning horizons of private insurance contracts. Annual contracts do not promote making investments early in the life cycle, even though they might avert many costly illnesses later in life.43,44 RHTs could take a long-term perspective because they would be responsible for the entire population in their geographic area over the long run.

Third, the proposed NHT and RHTs could slow the growth of health care costs by enhancing the efficiency with which providers deliver care. In the medical care sector, an NHT could develop treatment guidelines for high-quality care, assess new technology, improve information systems, and eliminate overlapping responsibilities across programs to prevent wasteful cost shifting. In the public and population health sectors, an NHT's efforts to identify and disseminate cost-effective interventions would increase the impact of health spending.

Health Care Delivery the American Way

Our proposed delivery system would build on existing components of the current health care system to create a national health plan incorporating competing private health plans, similar to the universal-coverage, regionally administered national systems in Germany, Switzerland, and the Netherlands. Each of these countries achieves superior health outcomes yet spends a smaller proportion of gross domestic product on health (between 9.2% and 11.6%) than does the United States.2

The United States has numerous large insurance plans and managed care plans that could form the foundation of the health plans in an organized market, as in the example of Germany. Prior to 1996, a German's occupation or residence determined eligibility for particular sickness funds, each of which operated as a separate risk pool. These funds were incorporated into a national system, which had evolved by 2009 to allow residents to choose among competing sickness funds, which are financed primarily by risk-adjusted capitations from a central, national health fund.45 France and Israel also built on existing employer-based insurance and contributions, which began as voluntary arrangements, to create a universal, national health insurance system.36,42

Our proposal for an independent national health care system presents political and practical challenges, including preventing risk segmentation, adopting health information technology, and empowering RHTs to take an active role in promoting population health. These challenges may be judged as minor, however, compared with the failings of the current system, with more than 46 million Americans uninsured, escalating medical costs, no connection or coordination between public and population health and personal medical care, highly variable quality of care, and no national mechanism to ensure that needed investments are made to promote long-term health. An HTS would correct these failings by incorporating, rather than destroying, the American health insurance industry.

Acknowledgments

We thank the California Endowment for support through the Blue Sky Health Initiative. We also thank the Commonwealth Fund for support through The Emerging Paradigm in Health Systems; Achieving and Preserving Universal Entitlement in Developed Nations.

We are grateful to our colleagues on the Blue Sky Health Initiative, Helen DuPlessis, David Ganz, Neal Halfon, Mark Peterson, and Samuel Sessions, and to Rucker Johnson, Theodore Joyce, and Emmett Keeler for comments on previous drafts of this article.

Human Participant Protection

No protocol approval was necessary because no human participants were involved.

References

- 1.Anderson GF, Reinhardt UE, Hussey PS. It's the prices stupid: why the United States is so different from other countries. Health Aff (Millwood) 2003;22(1):89–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson GF, Frogner BK. Health spending in OECD countries: obtaining value per dollar. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27(6):1718–1727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aaron HJ. Budget crisis, entitlement crisis, health care financing problem–which is it? Health Aff (Millwood) 2007;26(6):1622–1633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McGlynn EA, Asch SM, Adams J, et al. The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. N Engl J Med 2003;348(26):2635–2645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sassi F, Hurst J. The Prevention of Lifestyle-Related Chronic Diseases: An Economic Framework Paris, France: OECD Publishing, 2008. OECD Health Working Paper 32 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Research and Policy Committee. Quality, Affordable Health Care for All Washington, DC: Committee for Economic Development; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fuchs VR, Emmanuel EJ. Health care reform: why? what? when? Health Aff (Millwood) 2005;24(6):1399–1414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.US Census Bureau Housing and household economic statistics division. Health insurance coverage: 2007. Available at: http://www.census.gov/hhes/www/hlthins/hlthin07/hlth07asc.html. Accessed November 21, 2008

- 9.Schoen C, Osborn R, How SK, Doty MM, Peugh J. In chronic condition: experiences of patients with complex health care needs, in eight countries, 2008. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28(1):w1–w16 Epub November 13, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Commission on a High Performance Health System. A High Performance Health System for the United States: An Ambitious Agenda for the Next President Hollander C, New York, NY: Commonwealth Fund; 2007:75 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Committee on Reviewing Evidence to Identify Highly Effective Clinical Services, Board on Health Care Services, Institute of Medicine. Knowing What Works in Health Care: A Roadmap for the Nation Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ginsburg PB. Employment-based health benefits under universal coverage. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27(3):675–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kindig DA. Understanding population health terminology. Milbank Q 2007;85(1):139–161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kindig D, Stoddart D. What is population health? Am J Public Health 2003;93(3):380–383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marmot M. Social determinants of health inequalities. Lancet 2005;365(9464):1099–1104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McGinnis JM, Williams-Russo P, Knickman JR. The case for more active policy attention to health promotion. Health Aff (Millwood) 2002;21(2):78–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Committee on Capitalizing on Social Science and Behavioral Research to Improve the Public's Health. Promoting Health: Intervention Strategies From Social and Behavioral Research Smedley BD, Syme SL, Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trust for America's Health Prevention for a healthier America: investments in disease prevention yield significant savings, stronger communities. 2008. Available at: http://healthyamericans.org/reports/prevention08. Accessed September 11, 2008

- 19.California Tobacco Control Program. California Tobacco Control Update 2009: 20 Years of Tobacco Control in California Sacramento: California Department of Public Health; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Himmelstein DU, Woolhandler S, Wolfe SM. Administrative waste in the U.S. health care system in 2003: the cost to the nation, the states, and the District of Columbia, with state-specific estimates of potential savings. Int J Health Serv 2004;34(1):79–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sessions SY, Lee PR. A road map for universal coverage: finding a pass through the financial mountains. J Health Polit Policy Law 2008;33(2):155–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Emanuel E. Healthcare, Guaranteed: A Simple, Secure Solution for America New York, NY: PublicAffairs; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Emanuel EJ, Fuchs VR, Garber AM. Essential elements of a technology and outcomes assessment initiative. JAMA 2007;298(11):1323–1325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Singer SJ, Garber AM, Enthoven AC. Near-universal coverage through health plan competition: an insurance exchange approach. : Meyer JA, Wicks EK, Covering America: Real Remedies for the Uninsured Dublin, Ireland: Economic and Social Research Institute; 2001:155–171 [Google Scholar]

- 25.United States Office of Personnel Management FEHBP handbook. 2006. Available at: http://www.opm.gov/insure/handbook/fehb01.asp. Accessed November 13, 2006

- 26.Asch SM, McGlynn EA, Hogan MM, et al. Comparison of quality of care for patients in the Veterans Health Administration and patients in a national sample. Ann Intern Med 2004;141(12):938–945 Available at: http://www.annals.org/cgi/content/full/141/12/938. Accessed March 18, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Evans DC, Nichol WP, Perlin JB. Effect of the implementation of an enterprise-wide Electronic Health Record on productivity in the Veterans Health Administration. Health Econ Policy Law 2006;1(Pt 2):163–169 doi:10.1017/S1744133105001210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adler-Milstein J, Bates DW, Jha AK. U.S. regional health information organizations: progress and challenges. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28(2):483–492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med 2002;346(6):393–403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Herman WH, Hoerger TJ, Brandle M, et al. The cost-effectiveness of lifestyle modification or metformin in preventing type 2 diabetes in adults with impaired glucose tolerance. Ann Intern Med 2005;142(5):323–332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dannenberg AL, Bhatia R, Cole BL, Heaton SK, Feldman JD, Rutt CD. Use of health impact assessment in the U.S.: 27 case studies, 1999–2007. Am J Prev Med 2008;34(3):241–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schoen C, Davis K, Collins SR. Building blocks for reform: achieving universal coverage with private and public group health insurance. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27(3):646–657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chernichovsky D. Pluralism, public choice, and the state in the emerging paradigm in health systems. Milbank Q 2002;80(1):5–39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fisher ES, Berwick DM, Davis K. Achieving health care reform—how physicians can help. N Engl J Med 2009;360(24):2495–2497 Epub May 20, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pham HH, Schrag D, O'Malley AS, Wu B, Bach PB. Care patterns in Medicare and their implications for pay for performance. N Engl J Med 2007;356(11):1130–1139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gawande A. Getting there from here: how should Obama reform health care? New Yorker 2009;January 26:26–33 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miller RH, Luft HS. HMO plan performance update: an analysis of the literature, 1997–2001. Health Aff (Millwood) 2002;21(4):63–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kleinke JD. Dot-gov: market failure and the creation of a national health information technology system. Health Aff (Millwood) 2005;24(5):1246–1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van de Ven WP, Schut FT. Universal mandatory health insurance in the Netherlands: a model for the United States? Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27(3):771–781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Federal Hospital Insurance and Federal Supplementary Medical Insurance trust funds The 2008 annual report of the boards of trustees of the Federal Hospital Insurance and Federal Supplementary Medical Insurance trust funds. Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/ReportsTrustFunds. Accessed March 19, 2009

- 41.Leu RE, Rutten FFH, Brouwer W, Matter P, Rutschi C. The Swiss and Dutch Health Insurance Systems: Universal Coverage and Regulated Competitive Insurance Markets New York, NY: Commonwealth Fund; 2009. Publication 1220. Available at: http://www.commonwealthfund.org/Content/Publications/Fund-Reports/2009/Jan/The-Swiss-and-Dutch-Health-Insurance-Systems–Universal-Coverage-and-Regulated-Competitive-Insurance.aspx. Accessed February 6, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chernichovsky D, Chinitz D. The political economy of health system reform in Israel. Health Econ 1995;4(2):127–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Halfon N, Hochstein M. Life course health development: an integrated framework for developing health, policy, and research. Milbank Q 2002;80(3):433–479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heckman JJ. Economics of health and mortality special feature: the economics, technology, and neuroscience of human capability formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2007;104(33):13250–13255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schmidt U. Shepherding major health system reforms: a conversation with German health minister Ulla Schmidt. Interview by Tsung-Mei Cheng and Uwe Reinhardt. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27(3):w204–w213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]