Abstract

Many promising technology-based programs designed to promote healthy behaviors such as physical activity and healthy eating have not been adapted for use with diverse communities, including Latino communities. We designed a community-based health kiosk program for English- and Spanish-speaking Latinos. Users receive personalized feedback on nutrition, physical activity, and smoking behaviors from computerized role models that guide them in establishing goals in 1 or more of these 3 areas. We found significant improvements in nutrition and physical activity among 245 Latino program users; however, no changes were observed with respect to smoking behaviors. The program shows promise for extending the reach of chronic disease prevention and self-management programs.

Cardiovascular disease, although often preventable through nutrition and physical activity, remains the leading cause of death in the United States.1,2 Latinos are less likely than members of other racial/ethnic groups to receive information on how to prevent cardiovascular disease,3–6 in part because of their often limited access to health care services.7

Computer technology is rarely used as a means for health promotion among Latinos,8 even though it may greatly extend the reach, fidelity, and sustainability of health promotion efforts.9 We developed a computer program, LUCHAR (Latinos Using Cardio Health Action to Reduce Risk), with the goal of encouraging healthy diets and increased physical activity in the Latino population (luchar means “to battle” in Spanish). This interactive, computer-based program, designed to be self-administered via kiosks situated in community settings, is intended to help users increase physical activity, improve nutrition, and reduce or quit smoking.

LUCHAR, grounded in social science theory,10–13 was developed through formative community work14–18 (details on the development of the program are reported elsewhere19). Users can complete the program in English or Spanish and do so at their own pace. They begin by inputting their gender and age and are then matched to a computerized role model of the same gender and a similar age. With pictorial, audio, and musical accompaniment, the role model introduces the program and invites users to answer questions about their heart disease risk.

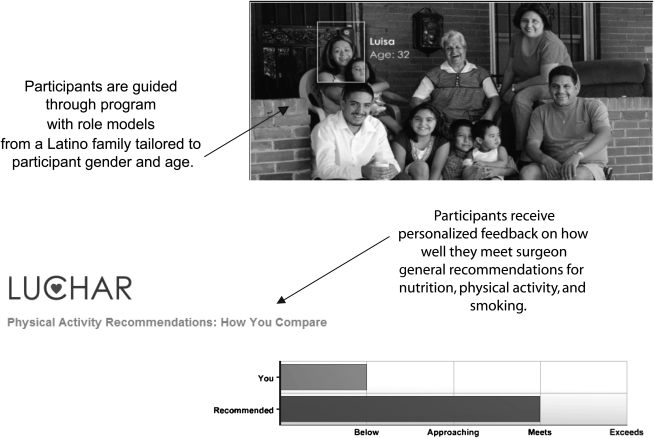

After answering questions about their health status and nutrition, physical activity, and smoking behaviors, users receive graphical feedback (Figure 1) showing comparisons with the surgeon general's recommendations in terms of these behaviors. The role model encourages users to set 1 behavior change goal related to physical activity, nutrition, or smoking, and they identify anticipated barriers to and strategies for achieving their goal. Users receive a printout at the completion of the program that includes their personal program summary and referrals for local resources that can help support their goal.

FIGURE 1.

Features of the LUCHAR program.

METHODS

Between March 2006 and October 2008, we partnered with trusted community-based organizations (2 social service agencies, a church, a school, and a coffee shop) and a primary care clinic serving Latinos in Denver, Colorado, to pilot test LUCHAR, giving them computers, kiosks, and printers to facilitate delivery of the program. A bilingual recruiter was regularly on site at the community and clinic facilities to enroll users, and agency representatives could refer interested users to this recruiter when she was not on site if they wanted to participate. The recruiter established rapport with users and helped them develop familiarity with the program's computers; she also completed all follow-up assessments, allowing for greater program continuity.

In the 5 community settings, we screened 285 Latinos to determine whether they were eligible for the program (participants were required to be English or Spanish speakers, residents of Denver, and aged 21 years or older); of the 230 who were eligible, 200 completed the program (36–51 at each community site). In the primary care clinic, we screened 134 persons, of whom 103 were eligible and 99 completed the program.

Two months after program completion, 81% of the community participants and 84% of the clinic participants were administered a telephone-based follow-up risk assessment (these retention rates are as high as or higher than those of many research programs involving Latinos14–17). Remaining participants were considered lost to follow-up after 5 failed contact attempts; most of these failed follow-up attempts were attributed to disconnected telephones (42%) and nonavailability because of travel to Mexico (38%). We observed no baseline demographic or behavioral differences between those completing and not completing the follow-up assessment.

RESULTS

LUCHAR program users were primarily aged between 31 and 50 years (64%), and all self-identified as Latino. Slightly under half (47%) were exclusive Spanish speakers, and the same percentage were men. A third (35%) had not completed high school. Many of the participants were classified as obese (56%), and 48% indicated that they had been diagnosed with at least 1 chronic condition.

Behavioral outcomes at the 2-month follow-up are shown in Table 1. Participants showed significant improvements in fruit and vegetable consumption at the follow-up assessment, along with significant increases in the overall quality of their diet and in their physical activity levels. The program had no impact on smoking behavior.

TABLE 1.

Outcomes for LUCHAR Pilot Community and Clinic Samples: Denver, CO, 2007–2008

| Community |

Clinic |

|||

| Baseline (n = 200) | 2-Month Follow-Up (n = 161) | Baseline (n = 99) | 2-Month Follow-Up (n = 84) | |

| Nutrition | ||||

| ≥ 5 fruit/vegetable servings per d, % | 14 | 25* | 14 | 30* |

| < 2 fruit/vegetable servings per d, % | 56 | 46* | 68 | 35** |

| Mean overall nutrition scorea | 5.1 | 4.6** | 6.0 | 4.1** |

| Physical activity, % | ||||

| Meets recommended guidelinesb | 33 | 49*** | 45 | 65** |

| Does not meet recommended guidelinesb | 52 | 40*** | 55 | 35** |

| Currently smokes, % | 20 | 19 | 18 | 16 |

Higher scores reflect poorer nutrition.

30 minutes of physical activity per day most days of the week.

*P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001.

DISCUSSION

We know of no other program that has demonstrated the feasibility of partnering with community-based organizations to deliver a computer-based health intervention to Latinos. Our easy-to-use, replicable program showed promising effects in this pilot study, with significant changes in nutrition and physical activity behaviors at 2 months. There were no effects on smoking, possibly because the program involved a 1-time, low-intensity intervention.

By providing evidence of the efficacy of technology-based health promotion efforts, LUCHAR and similar programs can improve the reach of health promotion in diverse communities. However, LUCHAR is not simply a computer-based program delivered on a kiosk; community partnerships and the availability of recruiters capable of establishing and sustaining rapport are essential to its success.

Our study involved limitations, including the use of self-reported data and the lack of a control group or randomization. To overcome these limitations, our next step will be to test LUCHAR in the context of a community-based, randomized controlled trial with the goal of documenting the program's effects on weight and body mass index.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported through funding provided by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (project 1U01 HL79208).

We acknowledge the following Denver community organizations that partnered with us in this work: Servicios de La Raza, San Cayetano, Centro Juan Diego, Remington School, and The Laughing Bean Café.

Human Participant Protection

This study was approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board. Participants provided written informed consent.

References

- 1.Minino AM, Heron MP, Smith BL. Deaths: preliminary data for 2004. Natl Vital Stat Rep 2006;54(19):1–49 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Greenland P, Knoll MD, Stamler J, et al. Major risk factors as antecedents of fatal and nonfatal coronary heart disease events. JAMA 2003;290(7):891–897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barbeau EM, Krieger N, Soobader M. Working class matters: socioeconomic disadvantage, race/ethnicity, gender, and smoking in NHIS 2000. Am J Public Health 2004;94(2):269–278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.State-specific trends in self-reported blood pressure screening and high blood pressure—United States, 1991–1999. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2002;51(21):456–460 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hajjar I, Kotchen TA. Trends in prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in the United States, 1988–2000. JAMA 2003;290(2):199–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glover MJ, Greenlund KJ, Ayala C, Croft JB. Racial/ethnic disparities in prevalence, treatment, and control of hypertension. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2005;54(1):7–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eakin EG, Bull SS, Riley K, Reeves MM, Gutierrez S, McLaughlin P. Recruitment and retention of Latinos in a primary care-based physical activity and diet trial: the Resources for Health Study. Health Educ Res 2007;22(3):361–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Latinos, Computers and the Internet: How Congress and the Current Administration's Framing of the Digital Divide Has Negatively Impacted Policy Initiatives Established to Close the Significant Technology Gap That Remains Berkeley, CA: Latino Issue Forum; 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glasgow R, Bull SS. Making a difference with interactive technology: considerations in using and evaluating computerized aids for diabetes self-management education. Diabetes Spectrum 2001;14(2):99–106 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bandura A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1986 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bandura A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control New York, NY: WH Freeman; 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stokols D, Allen J, Bellingham RL. The social ecology of health promotion: implications for research and practice. Am J Health Promot 1996;10(4):247–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glasgow RE, Strycker LA, Toobert DJ, Eakin E. A social-ecologic approach to assessing support for disease self-management: the Chronic Illness Resources Survey. J Behav Med 2000;23(6):559–583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Caban CE. Hispanic research: implications of the National Institutes of Health guidelines on inclusion of women and minorities in clinical research. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 1995;18:165–169 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olin JT, Dagerman KS, Fox LS, Bowers B, Schneider LS. Increasing ethnic minority participation in Alzheimer disease research. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2002;16(suppl 2):S82–S85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gauthier MA, Clarke WP. Gaining and sustaining minority participation in longitudinal research projects. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 1999;13(suppl 1):S29–S33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Senturia YD, McNiff Mortimer K, Baker D, et al. Successful techniques for retention of study participants in an inner-city population. Control Clin Trials 1998;19(6):544–554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patrick JH, Pruchno RA, Rose MS. Recruiting research participants: a comparison of the costs and effectiveness of five recruitment strategies. Gerontologist 1998;38(3):295–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Padilla R, Bull S, Raghunath SG, Fernald D, Havranek EP, Steiner JF. Designing a cardiovascular disease prevention Web site for Latinos: qualitative community feedback [published online ahead of print April 2, 2008]. Health Promot Pract [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]