Abstract

Background

Coregulator proteins are "master regulators", directing transcriptional and posttranscriptional regulation of many target genes, and are critical in many normal physiological processes, but also in hormone driven diseases, such as breast cancer. Little is known on how genetic changes in these genes impact disease development and progression. Thus, we set out to identify novel single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) within SRC-1 (NCoA1), SRC-3 (NCoA3, AIB1), NCoR (NCoR1), and SMRT (NCoR2), and test the most promising SNPs for associations with breast cancer risk.

Methods

The identification of novel SNPs was accomplished by sequencing the coding regions of these genes in 96 apparently normal individuals (48 Caucasian Americans, 48 African Americans). To assess their association with breast cancer risk, five SNPs were genotyped in 1218 familial BRCA1/2-mutation negative breast cancer cases and 1509 controls (rs1804645, rs6094752, rs2230782, rs2076546, rs2229840).

Results

Through our resequencing effort, we identified 74 novel SNPs (30 in NCoR, 32 in SMRT, 10 in SRC-3, and 2 in SRC-1). Of these, 8 were found with minor allele frequency (MAF) >5% illustrating the large amount of genetic diversity yet to be discovered. The previously shown protective effect of rs2230782 in SRC-3 was strengthened (OR = 0.45 [0.21-0.98], p = 0.04). No significant associations were found with the other SNPs genotyped.

Conclusions

This data illustrates the importance of coregulators, especially SRC-3, in breast cancer development and suggests that more focused studies, including functional analyses, should be conducted.

Background

Nuclear receptors are critical for proper development and function of many physiological pathways including lipid metabolism, inflammation, and cell growth [1-3]. Over the past 25 years, it has become clear that nuclear receptors are also critical for the onset and progression of many diseases, including cancer. In breast cancer, for example, estrogen receptor-α (ERα) is expressed and drives tumor growth in approximately 2/3 of cases. However, only recently it has been appreciated that proper nuclear receptor function is absolutely dependent on the interaction with coregulator proteins [4]. These proteins couple nuclear receptors with RNA polymerase II and chromatin remodeling machinery to either activate (coactivators) or repress (corepressors) nuclear receptor mediated gene transcription. And because a single or a subset of coregulators can simultaneously regulate multiple cellular processes through multiple nuclear receptors, they have been classified as 'master regulators' [3]. Keeping with this classification, many coregulators have been implicated in numerous human diseases, including breast cancer [5-10].

Family history is one of the strongest risk factors for breast cancer with the risk approximately double in first degree relatives of women with breast cancer compared to the general population [11]. Because of this, many attempts to identify genetic risk factors using multiple approaches have been conducted. However, despite the identification of mutations in the major risk factor genes such as BRCA1, BRCA2, PTEN, CHEK2, and ATM, it is estimated that ~75% of familial breast cancers have yet unidentified risk alleles [12]. ERα is expressed and drives a large fraction of breast cancer cases and is therefore an excellent candidate gene for identifying breast cancer risk factors. Recently, a significant association with familial breast cancer risk has been observed for the C allele of ESR1_rs2747648 in an allele dose-dependent manner. This variant is located in a miRNA-binding site in the 3' untranslated region of ESR1 [13]. However, historically very few associations have been found between SNPs in ERα and breast cancer risk. Further, a recent study conducted a comprehensive search of all SNPs in ERα that revealed no major risk associations (n>55,000 breast cancer cases and controls) [14]. This suggests that other players in the ER signaling pathway may be important for breast cancer risk. Because of the critical importance of coregulators for ERα function, we hypothesized that breast cancer risk is influenced by SNPs within the coactivators SRC-1/NCoA1 and SRC-3/NCoA3/AIB1 and the corepressors NCoR and SMRT/NCoR2.

We previously reported two SNPs in SRC-3 (rs2230782 and rs2076546) associated with reduced breast cancer risk in a case-control study of German and Polish high-risk, BRCA1/2 mutation-negative women (cases: 775, controls: 1628) [15]. In a recent study by Haiman et al [16], coregulator sequencing was conducted in 95 women with advanced breast cancer from the Multiethnic Cohort (African Americans, Latinos, Japanese, Native Hawaiians, and European Americans) to identify novel SNPs and determine their contribution to breast cancer risk in the Multiethnic Cohort (cases: 1612, controls: 1961). Two SNPs were significantly associated with breast cancer risk in this study (one in each of SMRT and CALCOCO1). These SNPs, however, are found exclusively or nearly exclusively in African Americans and therefore cannot be feasibly tested in DNA banks derived from European individuals. One SRC-3 SNP previously identified to be protective in our study [15] was genotyped (rs2230782) and found not to be associated with altered breast cancer risk in the Haiman study [16]. The other SNP we reported to be protective (rs2076546) was not genotyped in this study since it focused on non-synonymous SNPs.

Here we report an extension of our previous study that identified two SNPs within SRC-3 associated with reduced breast cancer risk [15]. We followed a similar approach by genotyping candidate SNPs for associations with breast cancer risk in a high-risk, BRCA1/2 mutation-negative case-control study; however, the original study was extended in three ways. First, three additional coregulators were examined. Second, we sequenced 96 apparently normal individuals from two populations (48 Caucasian Americans and 48 African Americans) to discover novel SNPs and to confirm or reveal SNP frequency information in different populations. Third, a larger population was examined, almost doubling the number of cases and significantly improving our statistical power. The association studies allowed us to strengthen the significance of the protective effect previously reported for a SNP in SRC-3 while extending it to a rare two-SNP haplotype that is highly protective for breast cancer risk.

Methods

SNP Discovery

Target sequence obtained from NCBI consisting of all exons, 500 bp of proximal promoter, and 25 bp of flanking introns from SRC-1, SRC-3, NCoR, and SMRT was submitted for primer design and Sanger sequencing to Polymorphic DNA Technologies Inc. (Alameda CA). DNA from 96 samples (48 Caucasian American, 48 African American) obtained from the Coriell Institute (Camden, NJ, USA) (sample sets: HD100CAU and HD100AA) was sequenced in both directions and aligned to NCBI reference sequence and previously reported SNPs in dbSNP. These samples had been collected and anonymized by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. Visual inspection of chromatograms was conducted for heterozygous calls.

Genotyping Cohort

A case-control study was conducted investigating a German familial breast cancer study cohort. Unrelated, German, female BRCA1/2 mutation negative index cases from breast cancer families were used in this study. The samples, all of Caucasian origin, were collected during the years 1997-2005 by six centers of the German Consortium for Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer (GC-HBOC: centers of Heidelberg, Würzburg, Cologne, Kiel, Düsseldorf and Munich, see authors affiliations). Familial cases were identified based on (A1) families with two or more breast cancer cases including at least two cases with onset below the age of 50 years; (A2) families with at least one male breast cancer case; (B) families with at least one breast cancer and one ovarian cancer case; (C) families with at least two breast cancer cases including one case diagnosed before the age of 50 years; (D) families with at least two breast cancer cases diagnosed after the age of 50 years; (E) single cases of breast cancer with age of diagnosis before 35 years. These selection criteria which have previously been reported [17] enrich for cases caused by genetic factor(s). The control population included healthy and unrelated female blood donors collected by the Institute of Transfusion Medicine and Immunology (Mannheim), sharing the ethnic background and sex with the breast cancer patients. The age distribution in the controls and cases was similar (controls: mean age 45.6 years, median age 46 years, age range from 18 to 68 years old; cases: mean age 45.1 years, median age 45 years, age range from 19 to 87 years old). According to the German guidelines for blood donation, all blood donors were examined by a standard questionnaire and gave their informed consent. They were randomly selected during the years 2004-2007 for this study and no further inclusion criteria were applied during recruitment. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Heidelberg (Heidelberg, Germany).

Genotyping

Genotyping was conducted using TaqMan allelic discrimination assays. Primers and TaqMan MGB probes were purchased from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA).

SRC-3 Q586H: 5'-CTGGGCTTTTATTGCGACCAAA-3V, reverse 5VGCTCTCCTTACTTTCTTTGTCACTGA-3'; TaqMan probes: forward 5'-TTCAATGTGTCACTCAAAT-3'-VIC, reverse 5'-CAATGTGTCAGTCAAAT-3'-FAM.

SRC-3 T960T: forward 5'-CCTGCACTGGGTGGCT-3', reverse 5'-CTCGCACCTGGTATGCTATTAGAC-3'; TaqMan probes: forward 5'-CTATTCCCACATTGCCTC-3'-VIC, reverse 5'-TTCCCACGTTGCCTC-3'-FAM.

SRC-3 C218R: forward 5'-AGACATAAACGCCAGTCCTGAAATG-3', reverse 5'-GCCAGAGATATGAAACAATGCAGTG-3'; TaqMan probes: forward 5'-TGAAATGCGCCAGAG-3'-VIC, reverse 5'-TGAAATGTGCCAGAG-3'-FAM.

SRC-1 P1272S: forward 5'-CCCTCCTCCTCAGAGTTCTCT-3', reverse 5'-CCTTCATGTCTGGTGACTGATACC-3'; TaqMan probes: forward 5'-CAGGTGGAGTTTGC-3'-VIC, reverse 5'-CAGGTGAAGTTTGC-3'-FAM.

SMRT A1706T: forward 5'-ACCTCGCAGCAGATGCA-3', reverse 5'-GAGGCCCCTCAGCATATCAG-3'; TaqMan probes: forward 5'-CCACAACACGGCCAC-3'-VIC, reverse 5'-CACAACGCGGCCAC-3'-FAM.

Genotyping call rates for all studies were >97%. The SNP assays were validated by re-genotyping 5% of all samples. The concordance rate for all SNPs varied from 99 to 100%.

Statistical Analysis

Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium test was undertaken using the chi-square "goodness-of-fit" test. Crude odds ratios (ORs), 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) and P values were computed by unconditional logistic regression using a tool offered by the Institute of Human Genetics, Technical University Munich, Germany http://ihg.gsf.de/cgi-bin/hw/hwa1.pl. Power calculations were determined using power and sample size calculator software PS version 2.1.31 http://www.mc.vanderbilt.edu/prevmed/ps/. With the total sample size, we had 80% power to detect OR of 0.79/1.26 and 0.57/1.56 for carrier frequencies of 30% and 5%, respectively.

Haplotype Analysis

Haplotypes of variants located in the same gene were determined using the PHASE 2 software created by Stephens et al. [18], or SNPHAP 1.3 software created by David Clayton http://www-gene.cimr.cam.ac.uk/clayton/software/snphap.txt. Each individual was assumed to carry the most likely pair of haplotypes and the haplotype distributions were estimated based on the controls.

Results/Discussion

SNP Discovery

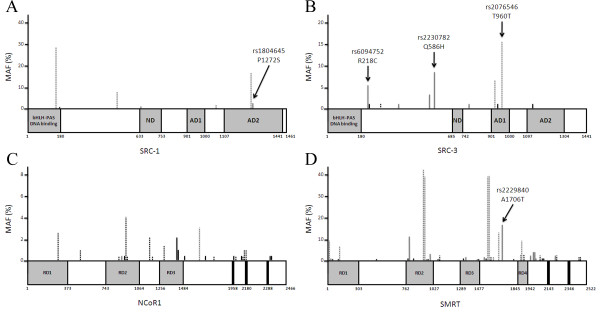

Complete coding regions and 25 bp of the flanking intronic regions of SRC-1, SRC-3, NCoR, and SMRT were fully sequenced in both directions using Sanger sequencing in 96 apparently normal individuals (48 Caucasian American, 48 African American) generating a total of ~5.8 MB of sequence. From this effort we identified 120 SNPs (61 in SMRT, 33 in NCoR, 18 in SRC-3, and 8 in SRC-1). A summary of the results is shown in Table 1 and details are provided in Additional File 1. Of these, 86 coding SNPs were identified resulting in 36 nonsynonymous SNPs (nsSNPs). SMRT contained the largest number of SNPs (61 total, 43 coding, and 17 nsSNPs). Despite its close relationship with SMRT, NCoR contains far fewer SNPs (33 total, 25 coding, and 10 nsSNPs). This is especially evident when only common SNPs are considered (minor allele frequency [MAF]>5%; 16 in SMRT, 1 in NCoR). The position of the coding SNPs and the MAF is schematically presented in Figure 1.

Table 1.

SNP Discovery Summary.

| Gene | Total SNPs | Coding SNPs | nsSNPs | Total SNPs MAF>5% | Novel SNPs | Novel nsSNPs | Novel SNPs MAF>5% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMRT | 61 | 43 | 17 | 16 | 32 | 6 | 7 |

| NCoR | 33 | 25 | 10 | 1 | 30 | 9 | 0 |

| SRC-3 | 18 | 11 | 8 | 5 | 10 | 3 | 1 |

| SRC-1 | 8 | 7 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 120 | 86 | 36 | 25 | 74 | 18 | 8 |

Figure 1.

SNP discovery in (A) SRC-1, (B) SRC-3, (C) NCoR, and (D) SMRT. Vertical lines delineate the position of SNPs identified by our resequencing effort. The height of the vertical lines represents the frequency at which the SNP was found. Black lines represent novel SNPs, grey lines represent SNPs found in dbSNP. Solid lines represent nonsynonymous SNPs, dashed lines represent synonymous SNPs. Positions of SNPs genotyped for risk associations are pointed out by arrows.

By conducting the sequencing in two populations, we were able to distinguish SNPs unique to a particular population. We identified 66 SNPs unique to African Americans and 23 SNPs unique to Caucasian Americans (see Additional File 1). This distribution is similar to that reported previously in the SNP@Ethnos database for Yoruban and European populations and is hypothesized to arise from bottlenecks in non-African population history[19] However, most of the unique SNPs found in Caucasians were rare, possibly suggesting that these are recent alterations since only 4 out of the 23 unique SNPs (17%) were found in more than a single individual. On the other hand, 31 out of the 66 unique SNPs (47%) in African Americans were found in more than a single individual. It is important to note that some of the population unique SNPs are rare and since only 48 individuals were sequenced for each population, they could appear as unique SNPs purely by chance.

From our sequencing effort we identified 74 SNPs in these four coregulators not previously represented in dbSNP or reported in the recent study by Haiman et al [16] (Table 1, columns on the right). We will refer to these SNPs as novel SNPs. Surprisingly, 8 of these novel SNPs were found at MAF>5% (7 within SMRT and 1 within SRC-3). Of the 74 novel SNPs, 18 were nonsynonymous, again with SMRT harboring many of the alterations. This illustrates that SMRT is by far the most polymorphic of the 4 coregulators. A recent study suggests that mutation rate, compared to selection pressure, has a larger impact on polymorphism frequency in a region [20]. Further, areas of condensed chromatin have been suggested to have the highest level of background mutation [21]. Together this suggests that SMRT is under less selective pressure than NCoR and/or is in a region of the genome with a higher mutation rate (possibly in an area of condensed chromatin).

Genotyping for Association with Breast Cancer Risk

We genotyped a case-control study of female index patients of BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation negative breast cancer families for two SNPs in SRC-3 which were previously shown to have a protective effect for breast cancer [15] (rs2230782 and rs2076546). Additionally, we genotyped other coregulator SNPs we rationalized may have functional consequences based on the severity of the amino acid change and proximity to functional domains [rs1804645 (SRC-1), rs6094752 (SRC-3), and rs2229840 & rs7978237 (SMRT)] (positions are highlighted in Figure 1). For example, rs1804645 (SRC-1 P1272S) was chosen since it is the only non-synonymous SNP in SRC-1, is located in the second activation domain, and is predicted to be 'probably damaging' by a polymorphism phenotype prediction tool (PolyPhen, http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph/). Rs6094752 (SRC-3 R218C) was chosen because of the loss of charge and size as a result of the amino acid substitution, and is one of the most common non-synonymous SNPs in SRC-3. The SNPs in SMRT, rs2229840 (A1706T) and rs7978237 (G781E) were chosen for genotyping due to high frequency, severity of amino acid change, and location in a functional domain. Several approaches to design TaqMan assays for rs7978237 failed. We were therefore unable to obtain genotyping information for this SNP.

The genotyping results were in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium in controls for all SNPs investigated (p = 0.309 for rs1804645; p = 0.112 for rs6094752; p = 0.058 for rs2230782; p = 0.067 for rs2076546; p = 0.140 for rs2229840). The three SNPs that we rationalized may have functional consequences that we were able to genotype, namely SRC-1 P1272S (rs1804645), SRC-3 R218C (rs6094752), and SMRT A1706T (rs2229840), did not significantly associate with breast cancer risk (Table 2). Also, stratification for age (> = 50 year and <50 years of age) in order to investigate a possible risk influence in pre- or postmenopausal women revealed no significant associations except for rs6094752 where a significant effect could be detected for heterozygous carriers only (Table 3). However, this is most likely a chance effect due to multiple testing. Stratification by bilateral cases revealed no significant associations (Table 4). We observed a protective effect of the homozygous c-allele carrier of SRC-3 Q586H rs2230782 (GG+GC versus CC: OR = 0.45, 95%CI = 0.041, Table 2), similar to the findings that have been reported before (GG+GC versus CC: OR = 0.39, 95%CI = 0.14-1.05 p = 0.061) [15]. As our study included a portion of the samples of the previous reported study it is noteworthy to mention that the results of the current study excluding the previously analyzed samples show the same protective effect and borderline significance (GG+GC versus CC: OR = 0.37, 95%CI = 0.13-1.08, p = 0.059). However, we failed to replicate previous associations between SRC-3 rs2076546 (T960T) SNP and breast cancer risk. The haplotype analysis of the variants analysed in SRC-3 revealed a protective haplotype including the C-C-G-alleles of R218C, Q586H and T960T, respectively (Table 5). As the haplotype is very rare occurring with a frequency of 0.03 in controls this result has to be verified in further multi-center collaboration studies.

Table 2.

Summary of associations in entire population

| SNP | Genotypes | Cases | Controls | OR | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SRC-1 | CC (%) | 1147 (94.2) | 1432 (94.9) | 1 | ||

| rs1804645 | CT (%) | 69 (5.6) | 77 (5.1) | 1.11 | 0.80-1.56 | 0.510 |

| P1272S | TT (%) | 2 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | - | - | - |

| [CT + TT]<-> [CC] | 1.15 | 0.82-1.60 | 0.405 | |||

| SRC-3 | CC (%) | 1089 (89.9) | 1330 (89.3) | 1 | ||

| rs6094752 | CT (%) | 116 (9.6) | 152 (10.2) | 0.93 | 0.72-1.20 | 0.587 |

| C218R | TT (%) | 6 (0.5) | 8 (0.5) | 0.92 | 0.32-2.65 | 0.871 |

| [CT + TT]<-> [CC] | 0.93 | 0.73-1.19 | 0.575 | |||

| SRC-3 | GG (%) | 988 (80.8) | 1207 (80.3) | 1 | ||

| rs2230782 | CG (%) | 226 (18.5) | 272 (18.1) | 1.11 | 0.83-1.23 | 0.881 |

| Q586H | CC (%) | 9 (0.7) | 24 (1.6) | 0.46 | 0.21-0.99 | 0.042 |

| [CC]<-> [GG + GC] | 0.45* | 0.21-0.98* | 0.041* | |||

| SRC-3 | AA (%) | 1011 (82.7) | 1240 (82.2) | 1 | ||

| rs2076546 | AG (%) | 202 (16.5) | 249 (16.5) | 0.99 | 0.25-1.22 | 0.961 |

| T960T | GG (%) | 9 (0.8) | 20 (1.3) | 0.55 | 0.25-1.22 | 0.135 |

| [AG + GG]<-> [AA] | 0.96° | 0.79-1.17° | 0.702° | |||

| SMRT | GG (%) | 789 (66.2) | 1004 (67.6) | 1 | ||

| rs2229840 | AG (%) | 357 (30.0) | 423 (28.5) | 1.07 | 0.91-1.27 | 0.407 |

| A1706T | AA (%) | 45 (3.8) | 57 (3.9) | 1.01 | 0.67-1.50 | 0.982 |

| [AG + GG]<-> [AA] | 1.06 | 0.91-1.25 | 0.441 | |||

Odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) and P-values. Please note that the results excluding samples (345 cases/1190 controls) that have been analysed in a previous study (14) are *OR = 0.37, 95%CI = 0.13-1.08, p = 0.059 and °OR = 1.13, 95%CI = 0.80-1.59, p = 0.491.

Table 3.

Associations according to age stratification

| SNP | Genotypes | Cases | Controls | OR | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases and Controls ≥50 | ||||||

| SRC-1 | CC (%) | 306 (93.9) | 747 (94.9) | 1 | ||

| rs1804645 | CT (%) | 20 (6.1) | 40 (5.1) | 1.22 | 0.70-2.12 | 0.479 |

| P1272S | TT (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | - | - | - |

| [CT + TT]<-> [CC] | 1.22 | 0.70-2.12 | 0.479 | |||

| SRC-3 | CC (%) | 299 (92.8) | 691 (89.0) | 1 | ||

| rs6094752 | CT (%) | 20 (6.2) | 80 (10.4) | 0.58 | 0.35-0.96 | 0.033 |

| C218R | TT (%) | 3 (1.0) | 5 (0.6) | 1.39 | 0.33-5.84 | 0.654 |

| [CT + TT]<-> [CC] | 0.62 | 0.39-1.01 | 0.053 | |||

| SRC-3 | GG (%) | 253 (78.1) | 623 (79.4) | 1 | ||

| rs2230782 | GC (%) | 68 (21.0) | 150 (19.1) | 1.12 | 0.81-1.54 | 0.502 |

| Q586H | CC (%) | 3 (0.9) | 12 (1.5) | 0.62 | 0.17-2.20 | 0.451 |

| [CC]<-> [GG + GC] | 0.60 | 0.16-2.14 | 0.429 | |||

| SRC-3 | AA (%) | 270 (83.6) | 653 (82.5) | 1 | ||

| rs2076546 | AG (%) | 52 (16.1) | 126 (15.9) | 0.99 | 0.70-1.42 | 0.991 |

| T960T | GG (%) | 1 (0.3) | 12 (1.6) | 0.20 | 0.02-1.56 | 0.088 |

| [AG + GG]<-> [AA] | 0.93 | 0.66-1.31 | 0.676 | |||

| SMRT | GG (%) | 222 (69.4) | 517 (67.0) | 1 | ||

| rs2229840 | AG (%) | 89 (27.8) | 220 (28.5) | 0.94 | 0.70-1.26 | 0.689 |

| A1706T | AA (%) | 9 (2.8) | 35 (4.5) | 0.59 | 0.28-1.27 | 0.175 |

| [AG + GG]<-> [AA] | 0.89 | 0.68-1.18 | 0.439 | |||

| Cases and Controls < 50 | ||||||

| SRC-1 | CC (%) | 682 (94.4) | 685 (94.9) | 1 | ||

| rs1804645 | CT (%) | 38 (5.3) | 37 (5.1) | 1.03 | 0.65-1.64 | 0.896 |

| P1272S | TT (%) | 2 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | - | - | - |

| [CT + TT]<-> [CC] | 1.08 | 0.69-1.72 | 0.725 | |||

| SRC-3 | CC (%) | 633 (88.6) | 639 (89.4) | 1 | ||

| rs6094752 | CT (%) | 77 (10.8) | 72 (10.1) | 1.08 | 0.77-1.52 | 0.658 |

| C218R | TT (%) | 4 (0.6) | 4 (0.6) | 1.01 | 0.25-4.05 | 0.989 |

| [CT + TT]<-> [CC] | 1.08 | 0.77-1.50 | 0.665 | |||

| SRC-3 | GG (%) | 592 (82.2) | 584 (81.3) | 1 | ||

| rs2230782 | GC (%) | 122 (16.9) | 122 (17.0) | 0.98 | 0.75-1.30 | 0.923 |

| Q586H | CC (%) | 6 (0.9) | 12 (1.7) | 0.49 | 0.18-1.32 | 0.152 |

| [CC]<-> [GG + GC] | 0.49 | 0.18-1.32 | 0.153 | |||

| SRC-3 | AA (%) | 592 (82.1) | 587 (81.7) | 1 | ||

| rs2076546 | AG (%) | 123 (17.1) | 123 (17.1) | 0.99 | 0.75-1.30 | 0.952 |

| T960T | GG (%) | 6 (0.8) | 8 (1.2) | 0.74 | 0.26-2.16 | 0.584 |

| [AG + GG]<-> [AA] | 0.98 | 0.75-1.28 | 0.862 | |||

| SMRT | GG (%) | 470 (66.9) | 487 (68.4) | 1 | ||

| rs2229840 | AG (%) | 202 (28.8) | 203 (28.5) | 1.03 | 0.82-1.30 | 0.796 |

| A1706T | AA (%) | 30 (4.3) | 22 (3.1) | 1.41 | 0.80-2.48 | 0.228 |

| [AG + GG]<-> [AA] | 1.07 | 0.85-1.33 | 0.561 | |||

Odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) and P-values.

Table 4.

Associations with stratification by bilateral cases

| SNP | Genotypes | Cases | Controls | OR | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases bilateral | ||||||

| SRC-1 | CC (%) | 106 (93.8) | 1432 (94.9) | 1 | ||

| Rs1804645 | CT (%) | 6 (5.3) | 77 (5.1) | 1.05 | 0.44-2.47 | 0.906 |

| P1272S | TT (%) | 1 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | - | - | - |

| [CT + TT]<-> [CC] | 1.22 | 0.55-2.73 | 0.613 | |||

| SRC-3 | CC (%) | 95 (86.4) | 1330 (89.3) | 1 | ||

| rs6094752 | CT (%) | 14 (12.7) | 152 (10.2) | 1.29 | 0.72-2.32 | 0.393 |

| C218R | TT (%) | 1 (0.9) | 8 (0.5) | 1.75 | 0.22-14.14 | 0.595 |

| [CT + TT]<-> [CC] | 1.31 | 0.74-2.32 | 0.347 | |||

| SRC-3 | GG (%) | 88 (80.0) | 1207 (80.3) | 1 | ||

| Rs2230782 | GC (%) | 22 (20.0) | 272 (18.1) | 1.11 | 0.68-1.80 | 0.675 |

| Q586H | CC (%) | 0 (0.7) | 24 (1.6) | 0.28 | 0.017-4.62 | 0.186 |

| [CC]<-> [GG + CT] | 1.02 | 0.63-1.65 | 0.938 | |||

| SRC-3 | AA (%) | 89 (80.2) | 1240 (82.2) | 1 | ||

| rs2076546 | AG (%) | 21 (18.9) | 249 (16.5) | 1.17 | 0.72-1.93 | 0.522 |

| T960T | GG (%) | 1 (0.9) | 20 (1.3) | 0.69 | 0.09-5.25 | 0.724 |

| [AG + GG]<-> [AA] | 1.14 | 0.70-1.85 | 0.597 | |||

| SMRT | GG (%) | 79 (72.5) | 1004 (67.6) | 1 | ||

| rs2229840 | AG (%) | 27 (24.8) | 423 (28.5) | 0.81 | 0.52-1.27 | 0.363 |

| A1706T | AA (%) | 3 (2.7) | 57 (3.9) | 0.67 | 0.20-2.18 | 0.502 |

| [AG + GG]<-> [AA] | 0.79 | 0.51-1.23 | 0.298 | |||

Odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) and P-values.

Table 5.

Associations of SRC-3 haplotypes

| Haplotypesa | Cases (%) | Controls (%) | OR | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CGA | 1847 (77.0) | 2199 (75.0) | 1 | ||

| CCA | 227 (9.5) | 298 (10.1) | 0.91 | 0.75-1.09 | 0.2963 |

| CGG | 205 (8.5) | 267 (9.1) | 0.91 | 0.75-1.11 | 0.3597 |

| TGA | 119 (4.9) | 162 (5.5) | 0.87 | 0.68-1.12 | 0.2824 |

| CCG | 0 (0.0) | 8 (0.3) | 0.07 | 0.004-1.21 | 0.0096 |

| TCG | 2 (0.1) | 1 (0.0) | 2.38 | 0.22-26.28 | 0.4651 |

| TGG | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.0) | 0.39 | 0.02-9.74 | 0.3659 |

a haplotypes representing the alleles of C218R, Q586H and T960T compared with wildtype. Haplotype frequencies of SRC-3 polymorphisms C218R, Q586H and T960T in the German study population compared with the, odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) and P-values.

The discordant findings between our studies and the Haiman study [16] with respect to SRC-3 Q586H may be due to the inherent differences in the populations examined. For example, our studies exclusively examined Europeans while the study by Haiman et al. examined a range of ethnic backgrounds. A number of recent studies suggest that a SNP association could be specific to the genetic background of a certain ethnic group [22,23]. It is possible that the Q586H effect is only seen in European populations, and/or that the lower number of unselected European cases within the Haiman study had insufficient power to detect this effect. The selection of high risk BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation negative cases in our study is expected to act as a multiplier to further increase our power to detect associations. Lastly, since only nonsynonymous SNPs were genotyped in the Haiman study, the stronger effect seen in the two-SNP SRC-3 haplotype could not be observed. We did not genotype the two SNPs (SMRT H52R and CALCOCO1 R12H) identified in the Haiman study to be associated with breast cancer risk since they were found either exclusively or predominantly in African Americans (European population MAF: SMRT H52R = 0%, CALCOCO1 R12H = 0.6%). Since our study exclusively contains Europeans, it was unlikely that we would obtain sufficient power to detect an association.

Conclusions

In summary, these results illustrate the dramatic differences in polymorphism frequency that can be seen amongst closely related genes. Further, the fact that so many novel SNPs were identified through our sequencing effort, even common SNPs with MAF>5%, illustrates the huge amount of genetic diversity that has yet to be discovered. Finally, the strengthening of the association between the SRC-3 Q586H SNP and decreased breast cancer risk, and the identification of a rare haplotype within SRC-3 associated with decreased risk, suggest that this information could be used to help identify a subgroup of high-risk women at a more modest risk. However, this remains to be verified prospectively.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

RJH helped to draft the manuscript, analyzed the re-sequencing data, and participated in the study design and coordination. ST performed genotyping assays and was involved in the statistical analysis and manuscript revisions. ASR, JW, SEM, TCS, JMR, SO were involved in the acquisition of the Coriell samples and their sequencing. KH, CS, ND, PB, BHFW, DN, NA, RVM, BW, RKS, AM, CRB, BB were involved in the generation and analysis of the breast cancer case-control study. BB and SO contributed equally to the study by conceiving it, participating in its design, and helping to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Supplementary Material

SNP Discovery Table. All variants in SMRT, NCoR, SRC-1, and SRC-3 identified from the sequencing effort are presented in this additional excel file. Variant information includes: genomic position, coding domain position, rs# (if applicable), nucleotide exchange, amino acid position and exchange (if applicable), and frequency in each of the populations.

Contributor Information

Ryan J Hartmaier, Email: hartmaie@bcm.edu.

Sandrine Tchatchou, Email: s.tchatchou@dkfz-heidelberg.de.

Alexandra S Richter, Email: asrichte@bcm.edu.

Jay Wang, Email: jayw@bcm.edu.

Sean E McGuire, Email: semcguir@bcm.edu.

Todd C Skaar, Email: tskaar@iupui.edu.

Jimmy M Rae, Email: jimmyrae@med.umich.edu.

Kari Hemminki, Email: k.heminki@dkfz-heidelberg.de.

Christian Sutter, Email: c.sutter@med.uni-heidelberg.de.

Nina Ditsch, Email: nina.ditsch@med.uni-muenchen.de.

Peter Bugert, Email: p.bugert@blutspende.de.

Bernhard HF Weber, Email: bweb@klinik.uni-regensburg.de.

Dieter Niederacher, Email: niederac@uni-duesseldorf.de.

Norbert Arnold, Email: nkarnold@email.uni-kiel.de.

Raymonda Varon-Mateeva, Email: raymonda.varon-mateeva@charite.de.

Barbara Wappenschmidt, Email: barbara.wappenschmidt@uk-koeln.de.

Rita K Schmutzler, Email: rita.schmutzler@uk-koeln.de.

Alfons Meindl, Email: alfons.meindl@lrz.tum.de.

Claus R Bartram, Email: cr_bartram@med.uni-heidelberg.de.

Barbara Burwinkel, Email: B.Burwinkel@dkfz-heidelberg.de.

Steffi Oesterreich, Email: steffio@bcm.edu.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by a DoD Predoctoral fellowship W81XWH-07-BCRP-PREDOC (RJH) and by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute Med into Grad Initiative for the Translational Biology and Molecular Medicine Graduate Program (RJH, SO), by the Pharmacogenetics Research Network Grant # U-01 GM61373 which supports the Consortium on Breast Cancer Pharmacogenomics (COBRA) (SO, TCS, JMR), a SPORE Pilot Project (SO) from SPORE (CA58183), and the Fetzer Family Memorial Fund. We would like to thank all participants who joined this study. The German breast cancer samples were collected within a project funded by the Deutsche Krebshilfe (Grant number: 107054). This study was supported by the Helmholtz society, the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ) and the Dietmar Hopp Foundation.

References

- Lonard DM, O'Malley BW. The expanding cosmos of nuclear receptor coactivators. Cell. 2006;125(3):411–414. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Malley BW. Coregulators: from Whence Came These 'Master Genes'. Mol Endocrinol. 2007;21(5):1009–13. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonard DM, O'Malley BW. Nuclear receptor coregulators: judges, juries, and executioners of cellular regulation. Mol Cell. 2007;27(5):691–700. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonard DM, Lanz RB, O'Malley BW. Nuclear receptor coregulators and human disease. Endocr Rev. 2007;28(5):575–587. doi: 10.1210/er.2007-0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agoulnik IU, Vaid A, Bingman WE, Erdeme H, Frolov A, Smith CL, Ayala G, Ittmann MM, Weigel NL. Role of SRC-1 in the promotion of prostate cancer cell growth and tumor progression. Cancer Res. 2005;65(17):7959–7967. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chopra AR, Louet JF, Saha P, An J, Demayo F, Xu J, York B, Karpen S, Finegold M, Moore D. Absence of the SRC-2 coactivator results in a glycogenopathy resembling Von Gierke's disease. Science. 2008;322(5906):1395–1399. doi: 10.1126/science.1164847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers E, Fleming FJ, Crotty TB, Kelly G, McDermott EW, O'Higgins NJ, Hill AD, Young LS. Inverse relationship between ER-beta and SRC-1 predicts outcome in endocrine-resistant breast cancer. British journal of cancer. 2004;91(9):1687–1693. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redmond AM, Bane FT, Stafford AT, McIlroy M, Dillon MF, Crotty TB, Hill AD, Young LS. Coassociation of estrogen receptor and p160 proteins predicts resistance to endocrine treatment; SRC-1 is an independent predictor of breast cancer recurrence. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(6):2098–2106. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaguchi H, Fujimoto J, Sun WS, Tamaya T. Clinical implications of steroid receptor coactivator (SRC)-3 in uterine endometrial cancers. The Journal of steroid biochemistry and molecular biology. 2007;104(3-5):237–240. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Yuan Y, Liao L, Kuang SQ, Tien JC, O'Malley BW, Xu J. Disruption of the SRC-1 gene in mice suppresses breast cancer metastasis without affecting primary tumor formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(1):151–156. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808703105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breast Cancer Facts & Figures 2007-2008

- Houlston RS, Peto J. The search for low-penetrance cancer susceptibility alleles. Oncogene. 2004;23(38):6471–6476. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tchatchou S, Jung A, Hemminki K, Sutter C, Wappenschmidt B, Bugert P, Weber BH, Niederacher D, Arnold N, Varon-Mateeva R. A variant affecting a putative miRNA target site in estrogen receptor (ESR) 1 is associated with breast cancer risk in premenopausal women. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30(1):59–64. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgn253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunning AM, Healey CS, Baynes C, Maia AT, Scollen S, Vega A, Rodriguez R, Barbosa-Morais NL, Ponder BA, Low YL. Association of ESR1 gene tagging SNPs with breast cancer risk. Human molecular genetics. 2009;18(6):1131–1139. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burwinkel B, Wirtenberger M, Klaes R, Schmutzler RK, Grzybowska E, Forsti A, Frank B, Bermejo JL, Bugert P, Wappenschmidt B. Association of NCOA3 polymorphisms with breast cancer risk. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(6):2169–2174. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haiman CA, Garcia RR, Hsu C, Xia L, Ha H, Sheng X, Le Marchand L, Kolonel LN, Henderson BE, Stallcup MR. Screening and association testing of common coding variation in steroid hormone receptor co-activator and co-repressor genes in relation to breast cancer risk: the Multiethnic Cohort. BMC cancer. 2009;9:43. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang R, Frank B, Hemminki K, Bartram CR, Wappenschmidt B, Sutter C, Kiechle M, Bugert P, Schmutzler RK, Arnold N. SNPs in ultraconserved elements and familial breast cancer risk. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29(2):351–355. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens M, Smith NJ, Donnelly P. A new statistical method for haplotype reconstruction from population data. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;68(4):978–989. doi: 10.1086/319501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J, Hwang S, Lee YS, Kim SC, Lee D. SNP@Ethnos: a database of ethnically variant single-nucleotide polymorphisms. Nucleic acids research. 2007. pp. D711–715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Gorlov IP, Gorlova OY, Amos CI. Relative effects of mutability and selection on single nucleotide polymorphisms in transcribed regions of the human genome. BMC genomics. 2008;9:292. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prendergast JG, Campbell H, Gilbert N, Dunlop MG, Bickmore WA, Semple CA. Chromatin structure and evolution in the human genome. BMC evolutionary biology. 2007;7:72. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-7-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meulenbelt I, Chapman K, Dieguez-Gonzalez R, Shi D, Tsezou A, Dai J, Malizos KN, Kloppenburg M, Carr A, Nakajima M. Large Replication Study and Meta-Analyses of Dvwa as an Osteoarthritis Susceptibility Locus in European and Asian Populations. Human molecular genetics. 2009. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zhang G, Goldblatt J, LeSouef PN. Does the relationship between IgE and the CD14 gene depend on ethnicity? Allergy. 2008;63(11):1411–1417. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2008.01804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

SNP Discovery Table. All variants in SMRT, NCoR, SRC-1, and SRC-3 identified from the sequencing effort are presented in this additional excel file. Variant information includes: genomic position, coding domain position, rs# (if applicable), nucleotide exchange, amino acid position and exchange (if applicable), and frequency in each of the populations.