Abstract

Background

Respiratory problems have been shown to be associated with the development of panic anxiety. Family members play an essential role for children to emotionally manage their symptoms. This study aimed to examine the relation between severity of respiratory symptoms in children with asthma and separation anxiety. Relying on direct observation of family interactions during a mealtime, a model is tested whereby family interactions mediate the relation between asthma severity and separation anxiety symptoms.

Methods

Sixty-three children (ages 9 – 12 years) with persistent asthma were interviewed via the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children IV; family interactions were assessed via direct observation of a mealtime; primary caregivers completed the Childhood Asthma Severity Scale; youth pulmonary function was ascertained with pre and post-bronchodilator spirometry; adherence to asthma medications was objectively tracked for six weeks.

Results

Poorer pulmonary function and higher functional asthma severity were related to higher numbers of separation anxiety symptoms. Controlling for medication adherence, family interaction patterns mediated the relationship between poorer pulmonary function and child separation anxiety symptoms.

Conclusions

Family mealtime interactions may be a mechanism by which respiratory disorders are associated with separation anxiety symptoms in children, potentially through increasing the child's capacity to cognitively frame asthma symptoms as less threatening, or through increasing the child's sense of security within their family relationships.

Separation anxiety is the most commonly diagnosed anxiety disorder in preadolescent children (Cartwright-Hatton, McNicol, & Doubleday, 2006). Childhood separation anxiety has the potential to endure into adulthood in the form of panic disorder (Klein, 1993; Slattery et al., 2002). Hence, explicating origins of separation anxiety is of concern to clinicians and researchers of childhood psychopathology.

One origin of separation anxiety may lie in the physiological sensation of anxiety. For example, some physiological models conceptualize panic anxiety (fright, fight, and flight) as one of a set of Central Nervous System reflexes (also including cough, fast and shallow breathing, glottic closure) designed to protect the respiratory system from short term dangers (Slattery et al., 2002; Wamboldt & Wamboldt, 2008). These protective reflexes can become sensitized, hyperresponsive, and dysfunctional, as in the context of chronic respiratory disorders (Gorman, Kent, Sullivan, & Coplan, 2000; Wamboldt & Wamboldt, 2008). In support of this hyperresponsivity hypothesis, high rates of panic disorder are often evidenced in patients with respiratory disorders such as asthma (Goodwin, Messineo, Bregante, Hoven, & Kairam, 2005). Similarly, children with asthma show greater rates of separation anxiety than children without asthma (e.g., 32% vs. 13%; Bussing, Burket, & Kelleher, 1996). Thus, this study focused on the relationship between asthma severity and anxiety – specifically, separation anxiety – in children with asthma.

Childhood Asthma and Anxiety Symptoms

While it is known that children with asthma experience elevated rates of anxiety symptoms overall (Ortega, Huertas, Canino, Ramirez, & Rubio-Stipec, 2002; Wamboldt, Weintraub, Krafchick, & Wamboldt, 1996), it is also clear that many children with asthma do not have increased anxiety symptoms. There is little consensus about the direct relation between asthma severity and anxiety in children. Some studies report no relation between disease severity and anxiety symptoms (Bussing et al., 1996; Wamboldt, Fritz, Mansell, McQuaid, & Klein, 1998) whereas others find such a relation (Richardson et al., 2006). These inconsistencies may be due to confounds in the measurement of severity (Wamboldt et al., 1998) and different conceptualizations of anxiety. First, whereas some studies calculate asthma severity from reports of functional asthma morbidity such as symptoms or health care utilization, other studies examine pulmonary function directly through spirometry. Short-term asthma control is not fully correlated with long-term asthma severity (i.e. severe asthma can be under excellent control with appropriate treatment or mild asthma can be associated with clinically significant flares). Therefore, in this study, we focused on the objective measurement of disease severity but also described the functional aspects of asthma morbidity garnered through parent report. In addition, we also controlled for adherence to prescribed asthma medications which can affect the current expression of disease symptoms associated with severity and has been found to be related to psychological adaptation (Bender, Milgrom, Rand, & Ackerson, 1998). Second, following previous published reports we focused on children who may have been sub-threshold for diagnosis of disorder but who expressed symptoms of separation anxiety and indicated significant impairment (Slattery et al., 2002). This standard is consistent with clinical practice, where functional impairment is of primary concern (Costello, Egger, & Angold, 2005).

Family Interaction Patterns

The family, which is charged with protection of children and the provision of security and stability (Bowlby, 1982), is a central arena in which children with asthma may learn how to interpret and process the threat of acute asthma symptoms. In addition, the family is also impacted by a child's asthma. We reasoned that families may respond to challenges in a variety of ways, which in turn, would be associated with separation anxiety.

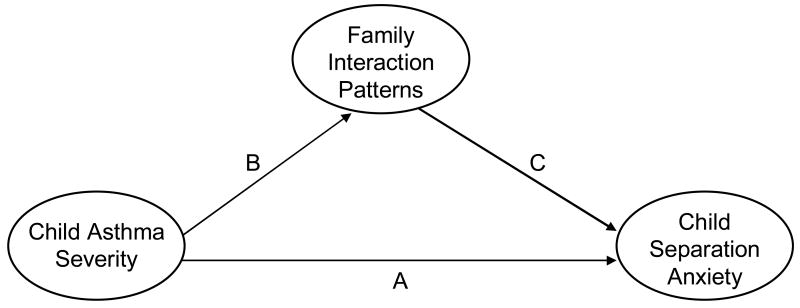

Although there is evidence of associations between family factors and child asthma severity, most studies focus on parenting factors as opposed to family-wide interaction patterns and conceptualize the family as contributing to the overall health of the child with asthma (Fiese & Everhart, 2006; Kaugers et al., 2004; Wood et al., 2006). Here, we focused on the links between asthma severity and family interaction patterns and family interactions and child separation anxiety symptoms. In the face of challenge, some families may create a responsive and organized environment that places the child at ease while other families may create a more chaotic or unresponsive environment that would foster symptoms of worry and anxiety. Thus, the goal of this study was to examine whether family interactions, as measured through a mealtime observation, would mediate the relation between asthma symptoms and separation anxiety symptoms (Figure 1, Path B-C).

Figure 1.

Proposed Direct and Indirect Pathways

To date, few studies have directly examined the relation between family interaction patterns and child separation anxiety symptoms. Wood and colleagues report significant relations between child anxiety and depression symptoms, negative family emotional climate (Wood et al., 2006), and asthma disease severity (Wood et al., 2007). Available evidence suggests that social context, for example a more secure attachment or the presence of a “safe other” during provocation testing, reduces the presence of panic and hyperventilation attacks (Wright, Rodriquez, & Cohen, 1998). Because separation anxiety is viewed as a childhood precursor of panic disorder, it is reasonable to expect that the extent to which a family environment is non-supportive would be associated with the development of anxiety symptoms in the context of more severe or poorly controlled asthma (Figure 1, Path C).

Mealtimes provide a window into both the instrumental and affective aspects of family interaction patterns associated with children's mental and physical health (Fiese, Foley, & Spagnola, 2006). A growing empirical base has demonstrated that frequency of mealtimes and how the task is accomplished (e.g., presence or absence of chaos) is associated with mental and physical health outcomes in children and youth (Compan, Moreno, Ruiz, & Pascual, 2002; Fulkerson, Strauss, Neumark-Sztainer, Story, & Boutelle, 2007); emotional connections during mealtimes protect adolescents from substance abuse and disordered eating (Eisenberg, Neumark-Sztainer, Fulkerson, & Story, 2008; Neumark-Sztainer et al., 2007); and family interactions during mealtimes are associated with health outcomes for children with chronic health conditions (Janicke, Mitchell, & Stark, 2005; Powers et al., 2002). Researchers have found mealtimes a valuable setting to assay family interactions because it involves the whole family (including fathers and siblings), is ecologically valid (Larson, Wiley, & Branscomb, 2006), and communication during mealtimes appears to be relatively stable over time (Mitchell, Piazza-Waggoner, Modi, & Janicke, 2009). Further, for youth between six and eleven years of age, 78.9% eat dinner with at least one parent seven nights a week (CASA, 2007). Thus, these are frequent events that have the potential to shape the child's expectations about how the family will respond during recurring events.

Restatement of Aims and Hypotheses

We had two guiding questions in this study. First, is asthma severity, as measured by pulmonary testing and by reported asthma symptoms, related to the development of separation anxiety symptoms in children? We relied on child responses to structured interviews about anxiety symptoms because children tend to be more reliable reporters of their internalizing symptoms than their parents (Costello, 1989). Second, can family interaction patterns mediate the association between asthma separation anxiety symptoms? We examined how the family interacts during a mealtime in their own home as a way of getting a naturalistic assay of typical family behaviors: 90% of the families described their recorded meals as typical or very typical. We expected family interaction observed during mealtime to partially mediate the relation between asthma severity and separation anxiety symptoms. We hypothesized that the stress related to a child with greater asthma severity may compromise family interaction patterns, and that both asthma severity and less organized and less affectively supportive family interactions would be associated with increased anxiety symptoms in the child.

Method

Participants

Data were drawn from a larger study of family life and asthma. Families were recruited through an ambulatory clinic at a teaching hospital, a pediatric pulmonary clinic, or area group pediatric practices in a mid-size city. Families responded to flyers describing the “Family Life and Asthma” study. Participants were told researchers were interested in learning about family experiences with asthma. Child inclusionary criteria were: (1) between the ages of five and twelve, (2) had an asthma diagnosis (of at least one year) as indicated by physician notes in medical records and by a spirometric test conducted by a licensed respiratory therapist and analyzed by a pediatric pulmonologist, (3) prescribed daily asthma controller medication for at least six months, and (4) was not diagnosed with a chronic medical condition other than asthma. Participants were excluded if they were currently in foster care due to informed consent restrictions. Participants included in this report include a sub-sample of 63 children (37 boys; 9-12 years (M = 10.16 (SD = 1.10) who were at least nine years old (and therefore able to complete the structured interview) and their primary caregivers (95% mothers, 3% grandmothers, and 2% fathers). Caregiver-reported child race was 33% African-American, 54% Caucasian, 10% other (typically mixed race) and 3% Hispanic. Socioeconomic status (Hollingshead, 1975), ranged from 8.0 – 66.0 (M=39.49; SD=17.9). Forty-four percent of primary caregivers reported being in their first marriage, 3% living with a partner, 13% remarried, 18% single or widowed, and 21% separated or divorced.

Procedure

In this Institutional Review Board approved study, children and caregivers were interviewed in a home-like laboratory setting where caregiver written consent and child verbal assent were obtained. Of the families who expressed interest in the study, 14% were ineligible upon further screening. Of the remaining eligible participants, 94% completed the laboratory visit during which caregivers and children completed questionnaires and were interviewed about child mental and physical health. Within one week of the lab visit, research assistants went to the family's home, set up a video camera, and instructed the family on how to record the meal.

Measures

Demographics

Primary caregivers reported education and occupation and socioeconomic status was calculated according to Hollingshead (1975).

Medication Adherence

Adherence was tracked for six weeks either through electronic recording devices (MDIlog-II) or telephone diaries depending on the type of medication that the child was prescribed (e.g., telephone diaries for oral controller medications where electronic devices were not available at the time of the study). Adherence was the number of doses taken over doses prescribed for each day, averaged over the six week period. While the MDILog ratings provide a more objective measure of adherence (Bender et al., 2000), telephone diaries can provide acceptable estimates of medication adherence (Rapoff, 1999).

Childhood Asthma Severity Scale (CHAS)

Caregivers completed the CHAS based on asthma related events over the past year (Ortega, Belanger, Bracken, & Leaderer, 2001). Predictive validity of the CHAS has been established by l associations with functional limitations and asthma related activity changes. Fourteen questions assess asthma severity along three general dimensions: 1) asthma symptoms, 2) health care utilization, and 3) medication use. A total score was calculated (internal consistency in this sample, α= .75).

Asthma Severity/Lung Function (Spirometry)

A respiratory therapist conducted a spirometry test during the laboratory visit. Testing was performed on a PDS 313100-WSU KOKO Spirometer and yielded measurements of forced vital capacity (FVC), forced expiratory flow in 1 second (FEV1), and forced expiratory flow, 25% to 75% of vital capacity (FEV25-75.). Each child performed three FVC maneuvers into a spirometer while at rest, and the test with the largest sum of FVC and FEV1 was used for analysis. Spirometry was repeated 10 minutes after albuterol was administered by MDI with aid of an Aerochamber. Severity was classified as: FEV1 ≤ 40% of predicted = severe; FEV1 > 40% and ≤ 60% = moderate; FEV1 > 60% and ≤ 80% = mild; and FEV1 80% or greater = slight, or normal. These classifications, made by a board certified pediatric pulmonologist, yielded a 1-4 scale where higher scores indicate more compromised lung function.

Family Mealtime Interaction

The Mealtime Interaction Coding System (MICS; (Dickstein, Hayden, Schiller, Seifer, & San Antonio, 1994) is adapted from the McMaster Model of Family Functioning. The MICS has been used to study family interactions with children with a variety of conditions including childhood obesity (Moens, Braet, & Soetens, 2007) and behavior problems (Dickstein, St. Andre, Sameroff, Seifer, & Schiller, 1999). We utilized scales that reflect family organization (Task Accomplishment and Roles) and family affect (Interpersonal Involvement and Affect Management). Task Accomplishment identifies the progression of the meal (structure, resolution of disruptions), ranging from 1 (chaotic/little routine) to 7 (flexible, well-planned and managed meal). The Roles ratings, reflecting the extent to which family dinnertime responsibilities seem explicit, age-appropriate, and distributed in a balanced way, range from 1 (inappropriately, ineffectively or unfairly distributed) to 7 (clear, reasonable and agreed-upon roles). Interpersonal Involvement focuses on verbal and non-verbal ways in which family members exhibit that they value and are interested in others' feelings, opinions, and experiences, with ratings ranging from 1 (extreme lack of involvement or over-involvement) to 7 (everyone demonstrates empathic involvement with others). Affect Management captures the production of affect (e.g., appropriateness, intensity) and the sensitivity of the response; ratings range from 1 (restricted, incongruent, or labile emotions) to 7 (emotions are expressed and responded to sensitively). All raters were blind to other results of the study. Each scale is scored separately after viewing the first twenty minutes of the mealtime interaction. Twenty percent of the interactions were double-coded by raters. Interrater reliability, intraclass correlations, for the four constructs ranged from .76 to .94 (M= .87).

Separation Anxiety

Separation anxiety was assessed via the computer assisted Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children-Youth Version (Jensen et al., 1995). We employed both the sum of separation anxiety symptoms endorsed and the DISC sub-threshold designation when a probable diagnosis was assigned when functional impairment was present. The validity of the DISC-IV youth self-report is supported by the agreement of previous versions with clinician ratings (Shaffer, Fisher, Lucas, Dulcan, & Schwab-Stone, 2000).

We considered separation anxiety in two ways consistent with previous reports (Slattery et al., 2002). First, we totaled the number of symptoms endorsed by the child to create a total score. Second, for descriptive purposes we created a categorical distinction following DISC IV algorithms for symptoms and impairment resulting in a sub-threshold grouping of separation anxiety.

Results

To address the first goal of this study, we examined correlations between asthma severity and total separation anxiety symptoms. Children reported a range of anxiety symptoms from zero to 11. Both pulmonary function and parent reported functional asthma severity were significantly related to total symptoms of separation anxiety. More separation anxiety symptoms were significantly associated with poorer pulmonary function (r = .35, p < .01) and higher parent reported wheezing (r = .28, p < .05), coughing (r = .33, p < .01), chest tightness (r = .29, p < .05), urgent care use (r = .29, p < .05), emergency room use (r = .38, p < .01), but not shortness of breath (r = .23, ns).

We also examined differences between two groups: children without separation anxiety (73%) and children with elevated separation anxiety symptoms (27%) based on being classified in the sub-threshold group of separation anxiety via levels of symptoms and impairment. These more symptomatic children did not differ from the other children on gender and age, but symptomatic designation was associated with lower SES [F (1,61) = 11.25, p ≤ .001]. The symptomatic separation anxiety group differed significantly from the less impaired group on both objective measures of disease severity (pulmonary function) and parent report of functional morbidity (see Table 1). We examined the relation between family interaction patterns and separation anxiety. For the symptomatic group, mealtime interactions were characterized by significantly more difficulty in getting the task of the meal accomplished, were less affectively responsive, and were less likely to assign roles during the meal than the group with no signs of separation anxiety. When considering the total separation anxiety symptom score, a similar pattern of results was evident. There were negative relations between the total separation anxiety score and task accomplishment (r = -.34, p < .01), affective responsiveness (r = -.28, p < .05), and roles (r = -. 32, p < .01).

Table 1.

Group Differences on Disease Severity and Mealtime Interactions for Separation Anxiety Groups

| Severity Measure | Group Mean (SD) | t (df) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sub-threshold Separation Anxiety And Impairment | Non-impaired Group | |||

| Child Asthma Severity | ||||

| Lung Function | 2.44 (.23) | 1.82 (.13) | 2.25 (60) | .03 |

| Parent Report | ||||

| Wheeze | 1.31 (.14) | 0.93 (.08) | 2.24 (60) | .03 |

| Cough | 1.56 (.13) | 1.17 (.08) | 2.56 (60) | .01 |

| Shortness of Breath | 1.50 (.13) | 1.17 (.08) | 2.02 (60) | .05 |

| Tightness | 1.31 (.14) | .91 (.09) | 2.32 (60) | .02 |

| Urgent Care | 0.62 (.12) | .32 (.07) | 2.14 (60) | .04 |

| ER | 0.62 (.11) | .24 (.06) | 2.96 (60) | .004 |

| Overall Score | 11.65 (.87) | 9.46 (.53) | 2.13 (60) | .04 |

| Mealtime Interactions | ||||

| Task Accomplishment | 3.8 | 4.9 | 2.73 (56) | .01 |

| Affect Management | 3.8 | 4.77 | 2.07 (56) | .04 |

| Interpersonal Involvement | 3.73 | 4.77 | 1.89 (56) | .06 |

| Roles | 4.13 | 5.14 | 2.57 (56) | .01 |

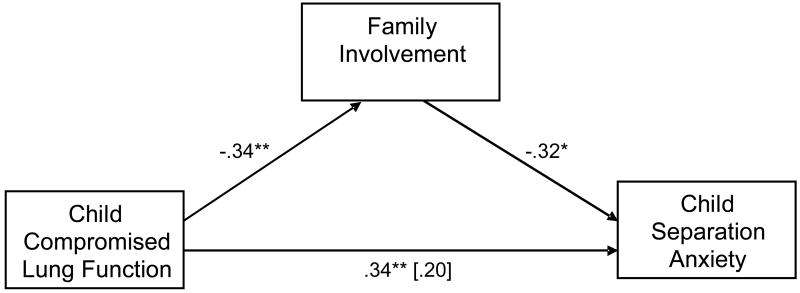

To address the second goal of this study and test the mediation models, we focused our analysis on the pulmonary function measure as it represents the most objective measure of disease severity. Moreover, because disease severity can be influenced by adherence to prescribed medications, we included medication adherence as a covariate in our mediation analysis. We tested each mediator model in a series of three steps. First, poorer pulmonary function was associated with greater symptoms of child separation anxiety, beyond the impact of medication adherence [F (2, 60) = 7.29, p < .01]. Second, over and above the impact of medication adherence, poorer pulmonary function was associated with less family task accomplishment [F (2, 55) = 4.34, p < .05] and affective involvement [F (2, 55) = 7.28, p< .01]. Third, over and above the effects of medication adherence and pulmonary function, separation anxiety was associated with family task accomplishment [F (3, 55) = 5.35, p <.05], roles [F (3, 55) = 6.45, p < .01], and involvement [F (3, 55) = 4.71, p < .05], but not affect management [F (3, 55) = 2.53, n.s.]. For all three supported mediators, the association between pulmonary function and separation anxiety no longer remained statistically significant, and was meaningfully smaller, with the addition of the family mealtime interactions to the model (see Figure 2 for illustration). To specifically test whether the mealtime interaction pathways were statistically significant, we employed procedures outlined in MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, & Sheets (2002). There were significant effects of child asthma severity on separation anxiety through family task accomplishment (z′= 1.59, p < .05), role maintenance (z′= 1.57, p < .05), and family involvement (z′= 1.75, p < .05).

Figure 2.

Illustration of Family Mealtime Mediation Models

*p < .05; ** p < .01 Reported values are standardized Beta coefficients.

Discussion

This study set out to examine whether the relationship between asthma symptoms and separation anxiety could be explained, in part, by variability in interactions observed during a family mealtime. We found three aspects of family interaction patterns that consistently mediated the relation between child asthma severity and separation anxiety symptoms: how the overall task of the meal was organized, role assignment, and overall family involvement. Taken together, this triad reflects family management strategies which is somewhat distinct from the emotional and affective aspects of family life (although they are certainly related). Family management strategies reflect how daily life is organized in its routine settings such as mealtimes, bedtimes, and other repetitive events such as homework. When families are overwhelmed or lack skills to keep routines in place then there are often psychological and physical costs to their children (Fiese, 2006). Other researchers have found that family chaos results in heightened psychophysiological reactivity (Evans, 2003). What this study adds to the literature is the direct observation of family interactions in relation to child mental health outcomes in the context of physiological (i.e., respiratory illness) risk.

It is reasonable to question whether mealtime interactions are representative of family exchanges. There is little extant literature that directly compares mealtime interactions with structured lab based observations. Hence we are not able to directly answer this question. However, we do know that mealtimes are fairly frequent events for over half of families with school age and teenage youth (CASA, 2007). Thus, they represent opportunities for family interaction that extends beyond the laboratory.

Confidence in our findings is supported by other reports that have found variations in mealtime interaction patterns in relation to such outcomes as psychosocial well-being in adolescents (Eisenberg, Olson, Neumark-Sztainer, Story, & Bearinger, 2004), pediatric overweight (Moens et al., 2007), and functional morbidity in other chronic health conditions (Powers et al., 2002; Stark et al., 2000). The repetitive nature of mealtimes may allow for checking in on symptom expression, a quick reminder to take medications, and planning ahead for the next day's events. Family management becomes part of the child's expectable environment and serves to reduce feelings associated with unpredictability and uncontrollability associated with anxiety. Family discussions which can calmly impart knowledge and communicate plans may serve as a proxy as to how families can help children understand and manage the physiologic symptoms associated with asthma.

Using a widely accepted structured clinical interview, we found elevated rates of separation anxiety symptoms in children with persistent asthma, which is consistent with epidemiological reports. While over one quarter of our sample endorsed symptoms that can be considered indicative of significant impairment, they did not meet criteria for diagnosis of separation anxiety disorders. In this regard, our report is similar to that of others that describe the increased risk of children with asthma for anxiety related disorders (Goodwin et al., 2005) and speaks to how considering symptoms and impairment at an early stage may inform clinicians about the early signs of anxiety as precursors of more serious conditions.

Consistent with predictions, we found a relatively strong relation between compromised lung function and separation anxiety symptoms, even while controlling for medication adherence. This suggests that for children with asthma, the felt experience of shortness of breath, wheezing, and coughing can translate into symptoms of worry, the desire to keep close proximity to caregivers, and symptoms associated with such worry and vigilance (e.g., headache, activity limitations). Over time, the occurrence of physiological symptoms associated with asthma may become connected to the psychological experience of anxiety. These results imply the utility of future studies designed to test the hypothesis that there is a physiological basis (e.g., CNS substrate or suffocation feeling) underlying panic anxiety.

Findings from this study should be considered in light of limitations, including the relatively small sample size. While we employed a purposeful sampling procedure to draw children from diverse health provider sites, we are cognizant of the fact that the families volunteered for the study and were organized enough to conduct a family mealtime. More mobile and chaotic family types may be less likely to volunteer for such studies. However, it should be noted that chaotic and disorganized mealtime interactions were observed. We also cannot rule out that mental health factors of family members significantly contributes to the interactions we observed.

Despite limitations, this study speaks to the potential utility in examining the origins of separation anxiety symptoms in high risk groups such as children with chronic asthma. Chronic risk conditions can compromise child functioning both directly and indirectly by affecting family functioning. Future research is warranted to examine more fully how compromised lung function influences family interaction patterns, and how those interactions contribute to the development of separation anxiety symptoms. Wood has proposed a biobehavioral model whereby parent-child relationship security predicts disease severity (Wood et al., 2006), and indeed it may be that family interaction patterns result in, and are a result of, asthma severity in a more circuitous manner than we have captured here.

Clinical Implications

This study focused on children at sub-threshold levels of separation anxiety. These are the children who often come to the attention of primary care physicians showing early signs of anxiety that may eventually lead to more serious disturbances, including post traumatic stress disorder and panic disorders (Costello, 1989). Therefore, these youth may be good candidates for clinical interventions aimed at reducing anxiety and preventing future panic disorders.

In addition, findings from this study reinforce the importance of family interactions in children's mental health. Although more severe asthma increased children's separation anxiety symptoms, findings imply that it did so in part by compromising families' interactions. Children who experience family mealtimes as times that operate in a relatively smooth manner, with expectable roles, and are opportunities for meaningful exchanges about the days' events may be less at risk for developing separation anxiety symptoms. If future research supports these findings, families could be encouraged to practice mealtime behaviors likely to promote child feelings of security and belonging, which in turn may reduce feelings of being left alone, panic, and fear frequently observed in children with anxiety symptoms. We recognize that this is not a panacea for the multiple challenges which families face- and that psychiatric conditions may present barriers to smooth mealtimes. However, healthy and organized daily routines may be indicated as one avenue where clinicians and families could forge partnerships in the interests of child wellbeing (Fiese & Wamboldt, 2000).

Key Points.

Asthma symptoms and separation anxiety are related.

Family interactions may mediate the relation between asthma symptoms and separation anxiety by providing a secure environment where there is responsive communication.

Greater asthma severity was related to greater separation anxiety symptoms through less supportive family interaction patterns during mealtime interactions. Compromised family interactions may increase feelings of isolation, panic, and fear associated with separation anxiety.

Promoting healthy mealtime interactions may be one way to foster child wellbeing.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant to the first author from the National Institute of Mental Health (#51771).

Contributor Information

Barbara H. Fiese, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Marcia A. Winter, Syracuse University

Frederick S. Wamboldt, National Jewish Health

Rani D. Anbar, Upstate Medical University

Marianne Z. Wamboldt, University of Colorado Denver School of Medicine

References

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender B, Milgrom H, Rand C, Ackerson L. Psychological factors associated with medication nonadherence in asthmatic children. Journal of Asthma. 1998;35:347–353. doi: 10.3109/02770909809075667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender B, Wamboldt FS, O'Connor SL, Rand C, Szefler S, Milgrom H, et al. Measurement of children's asthma medication adherence by self-report, mother report, canister weight, and Doser CT. Annals of Allergy, Asthma, & Immunology. 2000;85:416–421. doi: 10.1016/s1081-1206(10)62557-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss. Vol. 2. New York: Basic Books; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Bussing R, Burket RC, Kelleher ET. Prevalence of anxiety disorders in a clinic-based sample of pediatric asthma patients. Psychosomatics. 1996;37:108–115. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(96)71576-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartwright-Hatton S, McNicol K, Doubleday E. Anxiety in a neglected population: Prevalence of anxiety disorders in pre-adolescent children. Clinical Psychology Review. 2006;26:817–833. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CASA. The importance of family dinners III. New York: Columbia University; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Compan E, Moreno J, Ruiz MT, Pascual E. Doing things together: Adolescent health and family rituals. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2002;56:89–94. doi: 10.1136/jech.56.2.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ. Child psychiatric disorders and their correlates: A primary care pediatric sample. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1989;28:851–855. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198911000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Egger HL, Angold A. The developmental epidemiology of anxiety disorders: Phenomenology, prevalence, and comorbidity. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2005;14:631–648. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2005.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickstein S, Hayden LC, Schiller M, Seifer R, San Antonio W. Adapted from the McMaster Clinical Rating Scale. East Providence, RI: E. P. Bradley Hospital; 1994. Providence Family Study mealtime family interaction coding system. [Google Scholar]

- Dickstein S, St Andre M, Sameroff AJ, Seifer R, Schiller M. Maternal depression, family functioning, and child outcomes: A narrative assessment. In: Fiese BH, Sameroff AJ, Grotevant HD, Wamboldt FS, Dickstein S, Fravel DL, editors. The stories that families tell: Narrative coherence, narrative interaction, and relationship beliefs. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2. Vol. 64. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers; 1999. pp. 84–104. Serial no. 257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg ME, Neumark-Sztainer D, Fulkerson JA, Story M. Family meals and substance use: Is there a long-term protective association? Journal of Adolescent Health. 2008;43:151–156. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg ME, Olson RE, Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, Bearinger LH. Correlations between family meals and psychosocial well-being among adolescents. Archives Pediatric And Adolescent Medicine. 2004;158:792–796. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.8.792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans GW. A multimethodological analysis of cumulative risk and allostatic load among rural children. Deveopmental Psychology. 2003;39:924–933. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.39.5.924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiese BH. Family Routines and Rituals. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Fiese BH, Everhart RS. Medical adherence and childhood chronic illness: Family daily management skills and emotional climate as emerging contributors. Current Opinions in Pediatrics. 2006;18:551–557. doi: 10.1097/01.mop.0000245357.68207.9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiese BH, Foley KP, Spagnola M. Routine and ritual elements in family mealtimes: Contexts for child wellbeing and family identity. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development. 2006;111:67–90. doi: 10.1002/cd.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiese BH, Wamboldt FS. Family routines, rituals, and asthma management: A proposal for family-based strategies to increase treatment adherence. Families, Systems & Health. 2000;18:405–418. [Google Scholar]

- Fulkerson JA, Strauss J, Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, Boutelle K. Correlates of psychosocial well-being among overweight adolescents: The role of the family. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:181–186. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.1.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin RD, Messineo K, Bregante A, Hoven CW, Kairam R. Prevalence of probable mental disorders among pediatric asthma patients in an inner city clinic. Journal of Asthma. 2005;42:643–647. doi: 10.1080/02770900500264770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman J, Kent JM, Sullivan GM, Coplan JD. Neuroanatomical hypothesis of panic disorder, revised. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;157:493–505. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.4.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB. A four-factor classification of social status. New Haven, CT: Yale University; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Janicke DM, Mitchell MJ, Stark LJ. Family functioning in school-age children with cystic fibrosis: An observational assessment of family interactions in the mealtime environment. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2005;30:179–186. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsi005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen P, Roper M, Fisher P, Piacentini J, Canino G, Richters J, et al. Test-retest reliability of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC 2.1): Parent, child, and combined algorithms. Archives General Psychiatry. 1995;52:61–71. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950130061007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaugers AS, Klinnert MD, Bender BG. Family influences on pediatric asthma. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2004;29:475–491. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsh051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein DF. False suffocation alarms, spontaneous panics, and related conditions: An integrative hypothesis. Archives General Psychiatry. 1993;50:306–318. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820160076009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson RW, Wiley AR, Branscomb KR. Family meals as contexts of development and socialization. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell M, Piazza-Waggoner C, Modi A, Janicke D. Examining short-term stability of the mealtime interaction coding system (MICS) Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2009;34:63–68. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moens E, Braet C, Soetens B. Observation of family functioning at mealtime: A comparison between families of children with and without overweight. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2007;32:52–63. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsl011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumark-Sztainer D, Wall M, Haines J, Story M, Sherwood NE, van den Berg PA. Shared risk and protective factors for overweight and disordered eating in adolescents. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2007;33:359–369. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortega AN, Belanger KD, Bracken MB, Leaderer BP. A childhood asthma severity scale: Symptoms, medications, and health care visits. Annals Allergy Asthma Immunology. 2001;86:405–413. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)62486-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortega AN, Huertas SE, Canino G, Ramirez R, Rubio-Stipec M. Childhood asthma, chronic illness, and psychiatric disorders. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2002;190:275–281. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200205000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers SW, Byars KC, Mitchell MJ, Patton SR, Standiford DA, Dolan LM. Parent report of mealtime behavior and parenting stress in young children with Type I diabetes and in healthy control children. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:313–318. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.2.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapoff MA. Adherence to pediatric medical regimens. New York: Kluwer Academic; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson LP, Lozano P, Russo J, McCauley E, Bush T, W K. Asthma symptom burden: Relationship to asthma severity and anxiety and depression symptoms. Pediatrics. 2006;118:1042–1051. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Fisher P, Lucas CP, Dulcan MK, Schwab-Stone ME. NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version IV (NIMH DISC-IV): Description, differences from previous versions, and reliability of some common diagnoses. Journal of American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39:28–38. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slattery MJ, Klein DF, Mannuzza S, Moulton JL, Pine DS, Klein RG. Relationship between separation anxiety disorder, parental panic disorder, and atopic disorders in children: A controlled high risk study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2002;41:947–954. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200208000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark LJ, Jelalian E, Powers SW, Mulvihill MM, Opipari LC, Bowen A, et al. Parent and child mealtime behavior in families of children with cystic fibrosis. Journal of Pediatrics. 2000;136:195–200. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(00)70101-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wamboldt FS, Wamboldt MZ. Psychiatric aspects of respiratory symptoms. In: Taussig LM, Landau LI, editors. Textbook of Pediatric Respiratory Medicine. 2nd. St. Louis: Mosby; 2008. pp. 1039–1051. [Google Scholar]

- Wamboldt MZ, Fritz G, Mansell A, McQuaid EL, Klein R. The relationship of asthma severity and psychological problems in children. Journal American Academy Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1998;37:943–950. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199809000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wamboldt MZ, Weintraub P, Krafchick D, Wamboldt M. Psychiatric family history in adolescents with severe asthma. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1996;35:1042–1049. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199608000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood BL, Lim J, Miller BD, Cheah P, Zwetsch T, Ramesh S, et al. Testing the biobehavioral family model in pediatric asthma: Pathways of effect. Family Process. 2007 doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2008.00237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood BL, Miller BD, Jungha L, Lillis K, Ballow M, Stern T, et al. Family relational factors in pediatric depression and asthma: Pathways of effect. Journal of American Academy Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2006;45:1494–1502. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000237711.81378.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright RJ, Rodriquez MA, Cohen S. Review of psychosocial stress and asthma: An integrated biopsychosocial approach. Thorax. 1998;53:1066–1074. doi: 10.1136/thx.53.12.1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]