Abstract

Endothelia, once thought of as a barrier to the delivery of therapeutics, is now a major target for tissue specific drug delivery. Tissue and disease specific molecular presentations on endothelial cells provide targets for anchoring or internalizing delivery vectors. Porous silicon delivery vectors are phagocytosed by vascular endothelial cells. The rapidity and efficiency of silicon microparticle uptake lead us to delineate the kinetics of internalization. In order to discriminate between surface attached and internalized microparticles, we developed a double fluorescent/FRET flow cytometric approach. The approach relies on quenching of antibody conjugated fluorescein isothiocyanate covalently attached to the microparticle surface by attachment of a secondary antibody labeled with an acceptor fluorophore, phycoerythrin. The resulting half time for microparticle internalization was 15.7 minutes, with confirmation provided by live confocal imaging as well as transmission electron microscopy.

Key terms: phagocytosis, flow cytometry, endothelia, fluorescence quenching, live cell confocal imaging

Introduction

Vascular endothelial cells are accessible from the blood and thereby represent targets for drug delivery. Current vascular targeting strategies include antiangiogenic therapy, antivascular therapy (1), and first-stage targeting for multi-functional drug delivery vehicles (2). Distinct features of tumor blood vessels, i.e. vascular zip codes, can function as homing devices for intravascularly administered drug delivery vehicles labeled with appropriate peptides or antibodies (3). As a first step in designing delivery vectors for cancer therapeutics, we have fabricated porous silicon microparticles that are internalized by vascular endothelial cells via phagocytosis and macropinocytosis (4).

The distinction between professional and nonprofessional phagocytes is attributed to an array of dedicated phagocytic receptors on the former population that broadens their target range. Nonprofessional phagocytes, such as vascular endothelial cells, are able to internalize large micron size particulates (4), however, in contrast to professional phagocytes, serum opsonization of particulates hinders rather than augments internalization. One approach to bypass this obstruction is to bioengineer the surface of drug delivery vehicles to reduce binding to these serum dys-opsonins, favoring endothelial uptake of particulates (4).

To create delivery vectors with physical characteristics that favor transient interactions with endothelia, we first predicted the optimal size and shape of our silicon particles by mathematical modeling (5). Prior to applying targeting ligands to our vectors it is important to first establish techniques to measure binding and uptake of microparticles by endothelial cells. In this report, a comparison of existing methods, as well as a novel method, is presented which characterize the mechanics and kinetics of internalization. Due to a dependence of some of these techniques on fluorescent microparticles, which attract serum dys-opsonins, these studies were performed in serum-free media.

Materials and Methods

Silicon particle fabrication

Mesoporous quasi-hemispherical and discoidal silicon microparticles were designed, engineered, and fabricated in the Microelectronics Research Center at The University of Texas at Austin. Microparticles had a mean diameter of 3.2 ± 0.2 μm, with pore diameters 6.0 ± 2.1 nm (hemispherical) or 51.3 ± 28.7 nm (discoidal). Processing details were recently published by our laboratory (2,4). Briefly, heavily doped p++ type (100) silicon wafers (Silicon Quest, Inc, Santa Clara, CA) were used as the silicon source. Standard photolithography was used to pattern the microparticles over the wafer using a contact aligner (EVG 620 aligner) and AZ5209 photoresist. Particles were made porous using a two-step electrochemical etching process.

Microparticles were released by sonication and treated with piranha solution (1 volume H2O2 and 2 volumes of H2SO4) to oxidize the surface. The suspension was heated to 110–120 °C for 2 hour, washed in deionized water, and suspended in isopropyl alcohol (IPA) containing 0.5% (v/v) 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane (APTES) (Sigma) for 2 hour at room temperature. For fluorescence microscopy experiments, APTES-modified microparticles were conjugated to either DyLight 488 or DyLight 594 (Pierce; N-hydroxy succinimide (NHS)-ester activated fluorescent dyes), according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Antibody conjugation

APTES modified silicon microparticles were covalently modified with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated mouse monoclonal antibody (BD Biosciences; San Jose, CA) using the crossslinker sulfosuccinimidyl-4-(N-maleimidomethyl)cyclohexane-1-carboxylate (Sulfo-SMCC; Pierce, Rockford, IL). Silicon microparticles (3 × 107) were suspended in a 400 μl solution containing 2 mg Sulfo-SMCC (5mg/ml) for 30 minutes. Concurrently, 10 μg of antibody was reacted with the non-thiol reductant tris (2-carboxyethyl) phosphine (TCEP; 0.5 mM) in 100 μl to disrupt interchain disulphide bonds (phosphate buffer; 30 min). The pH of the antibody solution was adjusted to 6.5–7.5 using NaOH. Excess crosslinker was removed from the sulfhydryl-reactive silicon microparticles by washing with deionized water, and the activated antibody (10 μg;100 μl) was introduced. Following an overnight incubation at 4°C, free antibody was removed by washing twice in phosphate buffer. Uniform labeling of microparticles with antibody was confirmed by measuring fluorescence by flow cytometry (supplemental Figure 7).

Confocal microscopy

Human microvascular endothelial cells (HMVECs), a kind gift from Rong Shao at Baystate Medical Center/University of Massachusetts, were cultured in Clonetics® EGM® Endothelial Cell Growth Medium (Lonza; Walkersville, MD). For live cell imaging, HMVECs were cultured in glass bottom 24-well plates purchased from MatTek Corporation (Ashland, MA). CellTracker Green CMFDA (Molecular Probes Inc.; Eugene, OR) was introduced to the cells at 0.5 μM in serum-free medium for 30 minutes at 37°C, followed by another 30 minutes in fresh medium at 37°C. Cells were switched back to serum-free media (containing 0.2% BSA) for an additional 30 minutes to remove serum dys-opsonins that would block microparticle uptake by HMVECs, and subsequently DyLight 594-modified microparticles (1:10; cell:microparticle) were added to the culture. Images were acquired in 4 z-planes with a step size of 1.5 μm every 1 minute using a 1X81 Olympus Microscope equipped with a DSU Confocal Attachment and a 40x water-immersion objective. Still shots represent the best focal plane while the movie is comprised of projection images using in-focus light from all planes.

Flow cytometry

Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells (HUVECs) were purchased from Lonza Walkersville, Inc. and maintained in EBM®-2 medium (Clonetics®). HUVECs or HMVECs (1.5 × 105 cells/well) were seeded into 6 well plates and 24 hours later the cells were incubated with the specified number of silicon microparticles in serum-free media for 60 minutes. For studies examining the effect of CellTracker Green CMFDA on microparticle uptake, cells were treated as described in the previous section using 0.5–2.0 μM CellTracker prior to addition of the microparticles. Microparticle association with cells was determined by either measuring side scatter or fluorescent intensity using a Becton Dickinson FACSCalibur Flow equipped with a 488-nm argon laser and CellQuest software (Becton Dickinson; San Jose, CA).

For kinetic studies, HUVECs were preincubated in serum-free media for 2 hour at 37°C, then transferred to ice and cold media, containing 4 × 106 particles per well, was introduced. After 45 minutes, the media was replaced with warm media and cells were moved to 37°C for the indicated amount of time. Particle internalization was then stopped by washing the cells in cold PBS (containing 1% BSA) and incubating cells on ice for 30 minutes with 2.5 μg/ml Rat Anti-Mouse Ig, κ light chain antibody, either unlabeled or labeled with Phycoerythrin (PE; BD Pharmingen). Cells were recovered using trypsin and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

Microparticle binding and uptake by HUVECs was observed by scanning electron microscopy. Cells were plated in a 24 well plate containing 5 × 7 mm Silicon Chip Specimen Supports (Ted Pella, Inc., Redding, CA) at 5 × 104 cells per well. When cells were confluent, media containing microparticles (1:20, cell:microparticles, 0.5 ml/well) was introduced and cells were incubated at 37°C for 60 minutes. Samples were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde for 30 minutes (Sigma-Aldrich; St. Louis, MO), then dehydrated in increasing concentrations of ethanol, followed by incubation in a 50% alcohol-hexamethyldisilazane (HMDS; Sigma-Aldrich) solution for 10 minutes, with a final incubation in pure HMDS for 5 minutes to prepare for overnight drying in a desiccator. Specimens were mounted on SEM stubs (Ted Pella, Inc.) using conductive adhesive tape (12mm OD PELCO Tabs, Ted Pella, Inc.). Samples were sputter coated with a 10 nm layer of gold using a Plasma Sciences CrC-150 Sputtering System (Torr International, Inc.). SEM images were acquired under high vacuum, at 20.00 kV, spot size 5.0, using a FEI Quanta 400 FEG ESEM equipped with an ETD (SE) detector.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

HUVECs were grown to 80% confluency in a 6 well plate. Using 1 ml of serum-free EBM media per well, 3.2 μm particles were introduced at a cell:microparticle ratio of 1:10 at 37°C for 15 minutes. HUVECs were then washed and fixed in a solution of 2% paraformaldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences; Hatfield, PA) and 3% glutaraldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich) in PBS, pH 7.4 for one hour. After fixation, the samples were washed and treated with 0.1% Millipore-filtered cacodylate buffered tannic acid, post -fixed with 1% buffered osmium tetroxide for 30 minutes, and stained en bloc with 1% Millipore-filtered uranyl acetate. The samples were dehydrated in increasing concentrations of ethanol, infiltrated, and embedded in Poly-bed 812 medium. The samples were polymerized in a 60°C oven for 2 days. Ultrathin sections were cut in Leica Ultracut microtome (Leica, Deerfield, IL), stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate in a Leica EM Stainer, and examined in a JEM 1010 transmission electron microscope (JOEL, USA, Inc., Peabody, MA) at an accelerating voltage of 80 kV. Digital images were obtained using the AMT Imaging System (Advanced Microscopy Techniques Cory, Danvers, MA).

Results

Silicon microparticle uptake by endothelial cells

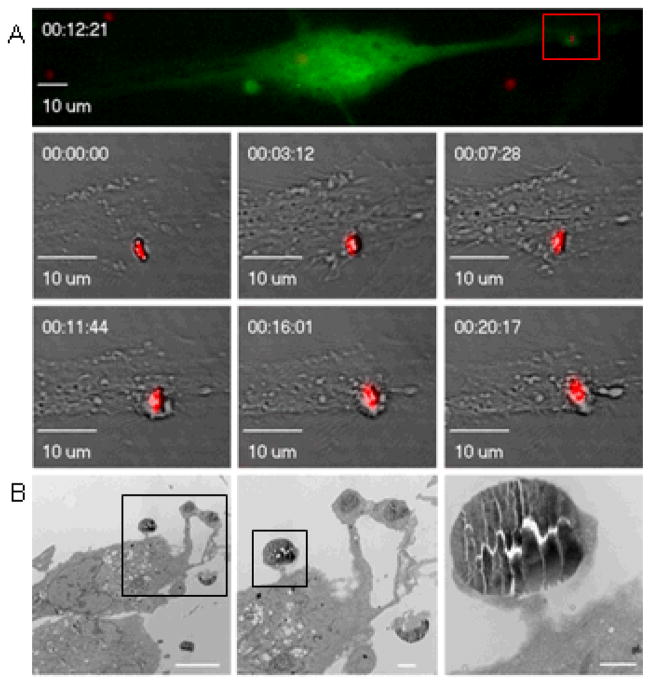

In this study, live uptake of silicon microparticles was monitored in HMVECs by real time confocal microscopy following treatment of cells with CellTracker Green CMFDA. The green fluorescent chloromethyl derivative of fluorescein diacetate freely passes through the cell membrane and once inside the cell is retained by transformation into a cell impermeant product. Silicon microparticles, modified with red DyLight 594, were added to the cell media and images were taken every 1 minutes. The top confocal image shown Figure 1.A. was taken 12 minutes after the microparticle came to rest near the endothelial cell. The region of microparticle uptake is amplified and shown at 6 time points. The corresponding movies are included in the supplemental data. Although the microparticle appears to be near the cell membrane throughout the movie, membrane stretching and accumulation of dye beneath the microparticle becomes most apparent around 5–7 minutes. Near 12 minutes the microparticle is surrounded by a large cellular ring which is maintained in all subsequent images. Live confocal imaging experiments and studies on the effects of CellTracker Green concentration on microparticles uptake were performed with HMVECs and discoidal microparticles, while all other experiments were performed with HUVECs and similarly sized quasi-hemispherical microparticles. Live cell imaging was performed at the UT-MDACC Shared Microscopy Facility.

Figure 1.

Time-lapse micrographs showing endothelial phagocytosis of a 3.6 μm silicon microparticle. A) HMVECs, stained with CellTracker Green, were imaged every 1 minute. A series of confocal images is shown to illustrate the sequence of steps involved in microparticle uptake. The color image shows the cell forming a ring around the particle at 12.3 minutes. B) Transmission electron micrographs were taken 15 s after introduction of microparticles to HUVECs at 37°C (magnification 3000; 6000; 25,000; bars 10, 2, and 0.5 μm).

The transmission electron micrographs shown in Figure 1.B. are a series of images taken at increasing magnification. HUVECs were incubated with microparticles at 4°C for 45 minutes to allow microparticles to bind the cell membrane. HUVECs were then warmed to 37°C for 15 minutes, and then fixed for sample processing. The images show pseudopodia which has migrated towards the microparticles. Some microparticles are completely engulfed by a ring of actin and cell membrane, while others (see highest magnification image) are at the pedestal stage of internalization and rest upon an actin cup.

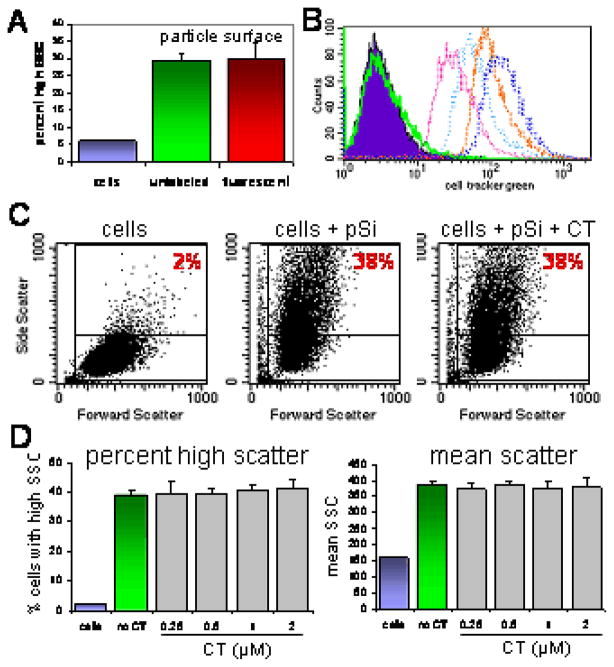

To verify that modification of the microparticle surface with Dylight-594 did not alter uptake by endothelial cells under serum-free conditions, cells were incubated with either unlabeled or Dylight-labeled microparticles for 45 minutes at 37°C. Figure 2A shows similar association of HMVECs with both types of microparticles. To examine the effect of CellTracker Green concentration on microparticle uptake, HMVECs were labeled with 0.25–2.0 μM CellTracker, then exposed to microparticles. A histogram showing the increase in fluorescence of cells with increasing concentrations of CellTracker Green in shown in Figure 2B. To quantitate the number of microparticles associating with cells, we measured the increase in orthogonal light scatter caused by cells that have internalized microparticles by flow cytometry (6) (Fig. 3C). While high side scatter is seen in approximately 2% of control cells, there is an increase in both the percent of cells displaying high side scatter and the mean intensity of the side scatter as the number of cell-associated microparticles increases. The two histograms on the right show cells associating with similar numbers of microparticles in the absence and presence of 2.0 μM CellTracker, respectively. The effect on CellTracker concentration on both the percent of cells with high side scatter and the mean side scatter in the presence of microparticles is shown in Figure 2D (n=3 per group). CellTracker, at any of the concentrations tested, did not affect association of HMVECs with microparticles. Similarly, CellTracker did not alter the association of HMVECs with Dylight-595 labeled microparticles (supplemental data Figure 8).

Figure 2.

Flow cytometric analysis of the effect of fluorescent labels on microparticle uptake. A) Association of HMVECs with either unlabeled (middle peak) or Dylight 594-labeled (right peak) silicon microparticles; B) Histogram showing the fluorescent intensity (FL1) of control cells (solid peak) and cells labeled with increasing concentrations of CellTracker Green; C) Dot plots showing the effect of microparticle (pSi) uptake and CellTracker Green (CT) on orthogonal light (side) scatter D) The impact of CellTracker Green on microparticle uptake is displayed as both the percent of cells with high side scatter (left) and as a measure of mean side scatter (right) in the presence of increasing concentrations of CellTracker Green at a fixed ratio of 10 microparticles per cell.

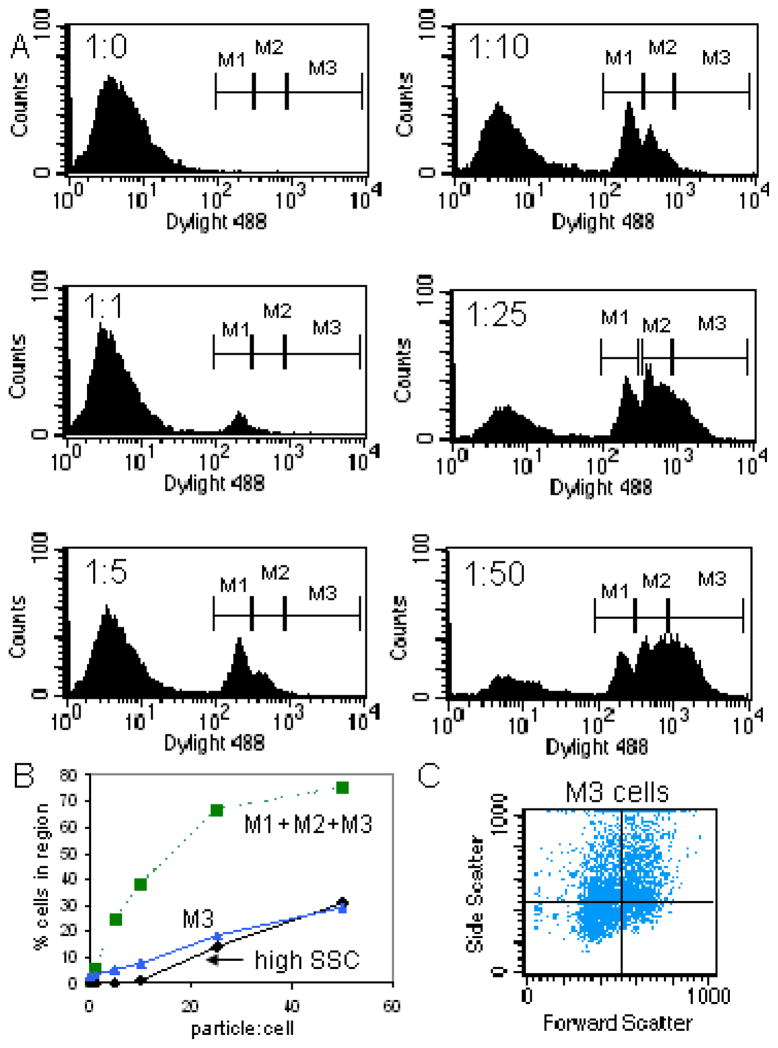

Figure 3.

Flow cytometric analysis of microparticle association with endothelial cells. A) Flow cytometric histograms of FL1 showing discrete cell populations arising from association of cells with increasing numbers of fluorescent microparticles. Each histogram represents an increasing ratio of microparticles to cells; B) Percentage of cells associating with microparticles based on either high side scatter (high SSC), or fluorescence. Both the total percent of fluorescent cells (M1+M2+M3) and the percent cells falling within the highest fluorescent region (M3) are shown; C) Cells within the M3 fluorescent region were selected and a scatter plot arising from that population of cells is displayed (i.e. cells were back-gated from M3).

Quantifying association of cells with silicon microparticles

A second approach for quantitating association of silicon microparticles with endothelial cells is measuring the mean fluorescent intensity of cells, or percent positive cells, as they engulf labeled microparticles (7). HUVECs were incubated with serial dilutions of DyLight 488-labeled microparticles (Fig. 3A). At a ratio of one microparticle per cell, a single positive peak arises (M1), which is accompanied by a second peak (M2) at 5 microparticles per cell. At higher microparticle ratios, a third broad peak (M3) arises, however, the early peaks representing low microparticle associations continue to persist.

Figure 3B is a titration of HUVECs with increasing numbers of microparticles comparing the use of side scatter verses fluorescent measurements to determine the percent of cells associating with microparticles. Fluorescence was a more sensitive measure of microparticle uptake when considering the total population of positive cells (M1+M2+M3). When comparing the percentage of brightly fluorescent cells (M3) to the percentage of high side scatter cells (high SSC), the association of cells with microparticles were analogous. This means that the defined high side scatter region is only occupied by cells associated with multiple microparticles. The scatter plot in Figure 3C, derived from brightly fluorescent cells (i.e. back-gated on M3), shows that brightly fluorescent cells display elevated side scatter, but that the range is still very diverse, both with respect to cell size and granularity.

While the above flow cytometry techniques measure microparticle association with cells, they don’t distinguish between microparticles on the cell surface and internalized microparticles. The next section describes existing methods for measuring particle uptake by flow cytometry and presents a new technique based on fluorescent antibodies.

Double-antibody assay for measuring kinetics of internalization

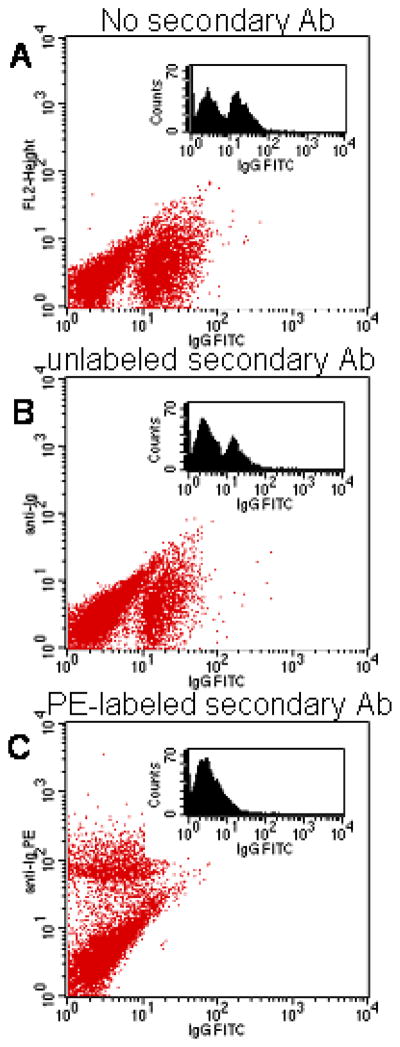

An existing method for measuring particle internalization calls for labeling particles/organisms with fluorescein, and subsequent to phagocytosis, labeling the DNA of surface organisms with ethidium bromide (8,9). Excitation of the surface fluorescein leads to resonance energy transfer to the ethidium bromide, resulting in red and green organisms on the surface. In order to enhance the phenomena of resonance energy transfer with surface particles we have modified microparticles with FITC conjugated antibodies, and subsequent to phagocytosis, we introduce secondary antibodies labeled with an acceptor fluorophore, PE. The proximity of the fluorophores causes complete quenching of the surface fluorescein, and simultaneously introduces red fluorescence to the surface particles, yielding red surface particles and green internal particles. This new approach also applies to particles which lack nucleic acids and therefore would not bind ethidium bromide. PE was chosen as the energy acceptor because its excitation spectra have a near complete overlap with the emission spectrum of FITC. This dual detection technique discriminates between surface and internal particles in a single data acquisition step and eliminates the need for multiple, sequential measurements.

Microparticles were conjugated to FITC labeled antibody, then incubated with cells on ice to allow binding, but prevent internalization (Fig. 4A). Next, a secondary antibody, either unlabeled or labeled with PE (FL2), was introduced and allowed to associate with primary antibody on microparticles bound to the cell surface (4°C). Binding by the unlabeled secondary antibody failed to effectively quench FITC fluorescence (Fig. 4B), however, when labeled with PE-conjugated secondary antibody, FITC fluorescence was completely quenched along with the concordinant increase in FL2 fluorescence (Fig. 4C). Thus quenching of FITC fluorescence associated with the microparticles was due to the proximity of the two fluorophores, and not due to nonspectroscopic binding of the secondary antibody.

Figure 4.

Dot plots showing the effect of secondary antibody binding on FITC emission from HUVECs incubated with microparticles. In all samples, HUVECs were incubated with FITC-conjugated antibody modified microparticles for 30 minutes at 4°C. A) Control sample; B–C) Samples after incubation with unlabeled (B) or PE-conjugated (C) secondary antibody. For all samples, histograms of FL1 are included as inserts.

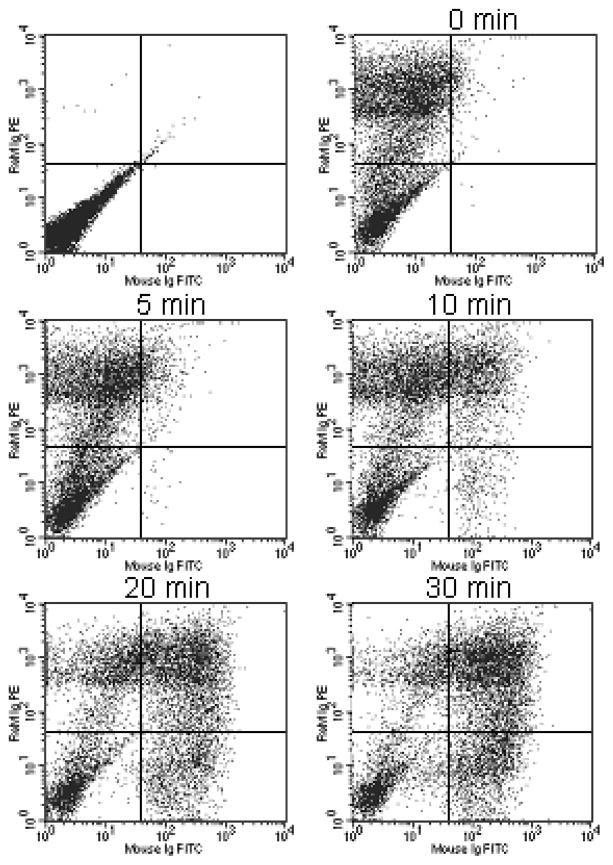

In order to measure the rate of particle internalization, HUVECs were surface labeled with FITC-conjugated antibody-modified microparticles by incubation at 4°C for 45 minutes (25 microparticles per cell). The cold media was then replaced with warm media to initiate internalization and the cells were moved to 37°C for the indicated amount of time. The cells were then put on ice and labeled with a secondary PE labeled antibody to label/quench microparticles remaining on the cell surface. Figure 5 contains dot plots that illustrate cells moving from FITC negative (UL, LL) to FITC positive quadrants (UR, LR) with time as the microparticles are internalized. At later time points, microparticles become completely internalized within a population of cells and the FITC positive cells are no longer co-labeled with PE (LR quadrant; labeled OUT in Fig. 6A).

Figure 5.

Dot plots at different time intervals for double fluorescent/FRET flow cytometric assay. HUVECs were incubated with FITC-antibody conjugated microparticles for 45 minutes on ice followed by incubation at 37°C for the indicated amount of time. Cells were then labeled with a PE-conjugated secondary antibody.

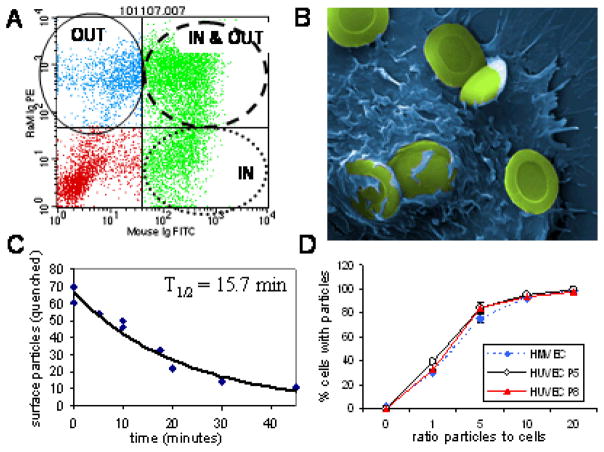

Figure 6.

Double fluorescent/FRET antibody assay. A) Dot plot quadrants represent cells with only surface particles (OUT), cells with surface and internal particles (IN & OUT), and cells with only internal particles (IN); B) A pseudo-colored scanning electron micrograph showing microparticles remaining on the cell surface or partially internalized after 60 minutes at 37°C. C) The decease in fluorescent quenching was used as a metric for calculating the rate of microparticle internalization. Data was fit to an exponential curve (y = 66.473e−0.0451x; R2 = 0.9501); D) Microparticle uptake was compared for HMVEC and HUVECs at passage 5 and 8.

The rate of internalization can either be derived from the increase in FITC fluorescence (i.e. particle internalization; UR + LR quadrants) or from the decrease in surface labeling with the secondary antibody (PE negative). However, there appears to be a limit to the number of microparticles that a cell can internalize, and any microparticles above that number remain bound to the cell surface. The scanning electron micrograph shown in Figure 6B is a HUVEC cell after incubation with microparticles for 60 minutes. While some microparticles are internalized, a large number of microparticles remain bound to the cell surface. In our flow cytometry assay, microparticles on the cell surface remain positive for PE labeling, eliminating the loss in surface PE staining as an indicator for calculating the rate of uptake. The rate of internalization was calculated by measuring the decrease in FITC quenching with time (Fig. 6C). Based on measurements from two separate experiments, the time for half the microparticles to be internalized was 15.7 minutes.

To validate the use of multiple endothelial cell lines and the use of HUVECs at different passages, microparticle uptake at increasing numbers of microparticles was compared between HMVECs and HUVECs at passages 5 and 8. The percentage of cells internalizing Dylight-488 labeled microparticles is shown in Figure 6D. No differences were seen between the cell types. Samples were run in triplicate and error bars are present but small. All experiments presented in this study based on HUVECs used cells between passages 3–8.

Discussion

Vascular endothelial cells have a tremendous ability to internalize porous silicon microparticles, rapidly and in numbers that can exceed 20 microparticles per cell. In order to define both the mechanics and kinetics of endothelial engulfment of porous silicon microparticles we have compared a number of experimental approaches, as well as modified existing techniques, to allow the discrimination between surface-bound and internalized microparticles.

The use of elevated side scatter as a metric for uptake of silicon microparticles by flow cytometry shows a linear relationship between microparticle association and side scatter; however, when compared to fluorescent measurements, the percent of cells engaging in microparticle contact is underrepresented. While both of these techniques are sensitive to the number of microparticles associating with cells, they are unable to discriminate between surface-bound and intracellular microparticles. To determine the location of microparticles, we developed a double fluorescent/FRET flow cytometric approach using fluorescent labeled antibodies. The rate of internalization was calculated to be t1/2 equals 15.7 min. Microscopic observations by confocal and transmission electron microscopy supported the calculated time interval for microparticle uptake. This time course encompasses all stages of microparticle internalization, which includes adhesion, the latency period, emergence of pseudopods (pedestal phase), and protrusion of lamellar pseudopods to surround the particle, as well as the final rounding phase in which the particle is pulled into the cell (10).

Previously, double fluorescent techniques using fluorescein labeled bacteria and specific PE-conjugated antibodies have been published but did not incorporate FRET (11). Studies in which PE has been used as an acceptor fluorophore for fluorescein emission include an approach developed by Posner et al.(12) for studying IgE-FcεRI aggregation. These researchers used DNP25PE to quench FITC-IgE bound to the cell surface in order to quantitate the number of occupied FcεRI receptors.

Established flow cytometry techniques that are able to discriminate between surface and internal particulates require acquisition of total fluorescence, followed by addition and dilution with a quenching agent, and reaquisition. Quenching agents include ethidium bromide (13), trypan blue (7,14–16), and crystal violet (17). In our hands, trypan blue quenching of FITC labeled microparticles on the cell surface was not effective for measuring internalization of silicon microparticles by HUVECs. This may be due to the large amount of internal fluorescence arising from intracellular microparticles. The advantage of using a double fluorophore based assay to measure internalization is that we are not relying solely on the shift of a single fluorescence peak to quantitate uptake, but rather measuring fluorescence from two fluorophores, one that emerges as the particle is internalized and the other which disappears upon internalization. The location of cells within a flow cytometric dot plot simultaneously provides a measure of both internalized and surface microparticles on single cells.

One problem encountered with our antibody-based double fluorescent/FRET flow cytometric approach is the finding that antibodies bound to the microparticle surface are dys-opsonins with respect to microparticle uptake by HUVECs (4). This inhibition is due to lack of Fc gamma receptors on the cell surface (4). In order to circumvent this problem, various techniques were compared for conjugating antibody to the microparticle surface. Treatment of the antibody with the reducing agent TCEP prior to attachment to the microparticle provided microparticles that were internalized by HUVECs. We hypothesize that this conjugation procedure either favored antibody orientations that shielded the Fc portion of the antibody, or altered the density of bound antibody.

While antibody mediated inhibition of microparticle uptake by endothelial cells was a potential problem for validating the double fluorescent/FRET flow cytometry approach with non-specific antibodies, it is also the key to creating an assay to measure uptake of drug delivery vehicles targeted to specific cell populations, such as tumor-associated endothelium. Drug delivery vehicles (i.e. nano and microparticles) are frequently labeled with highly specific antibodies to favor binding to cells located at pathological lesions. The effect of specific antibodies on both binding and internalization of particles can be quickly evaluated using our antibody-based double fluorescent/FRET flow cytometric approach. Additionally, this novel method for quantitiating both binding and internalization of particles can be used to assess the impact of antibody density on the particle surface and the impact of serum opsonins on binding and internalization of antibody-labeled particles.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the Rice Shared Resource Facility for use of the scanning electron microscope, and Kenneth Dunner Jr. at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Research Center (UT-MDACC) High Resolution Electron Microscopy Facility for sample processing and image acquisition by transmission electron microscopy. We appreciate Aaron Mack for his technical assistance.

This research was supported by grants DODW81XWH-07-1-0596, DODW81XWH-09-1-0212, and DODW81XWH-07-2-0101; NASA NNJ06HE06A; NIH RO1CA128797; State of Texas Emerging Technology Fund; and UT-MDACC Institutional Core Grant #CA16672.

References

- 1.Sato M, Arap W, Pasqualini R. Molecular targets on blood vessels for cancer therapies in clinical trials. Oncology (Williston Park) 2007;21(11):1346–52. discussion 1354–5, 1367, 1370 passim. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tasciotti E, Liu X, Bhavane R, Plant K, Leonard AD, Price BK, Cheng MM, Decuzzi P, Tour JM, Robertson F, et al. Mesoporous silicon particles as a multistage delivery system for imaging and therapeutic applications. Nat Nanotechnol. 2008;3(3):151–7. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2008.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ruoslahti E. Vascular zip codes in angiogenesis and metastasis. Biochem Soc Trans. 2004;32(Pt3):397–402. doi: 10.1042/BST0320397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Serda RE, Gu J, Bhavane RC, Liu X, Chiappini C, Decuzzi P, Ferrari M. The association of silicon microparticles with endothelial cells in drug delivery to the vasculature. Biomaterials. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Decuzzi P, Lee S, Bhushan B, Ferrari M. A theoretical model for the margination of particles within blood vessels. Ann Biomed Eng. 2005;33(2):179–90. doi: 10.1007/s10439-005-8976-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baldwin L, Flanagan BF, Hunt JA. Flow cytometric measurement of phagocytosis reveals a role for C3b in metal particle uptake by phagocytes. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2005;73(1):80–5. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hartig SM, Greene RR, Carlesso G, Higginbotham JN, Khan WN, Prokop A, Davidson JM. Kinetic analysis of nanoparticulate polyelectrolyte complex interactions with endothelial cells. Biomaterials. 2007;28(26):3843–55. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robinson JP, Carter WO, Narayanan P. Functional Assays by Flow Cytometry. In: Rose EdMNR, Folds JD, Lane HC, Nakumura R., editors. Manual of Clinical Laboratory Immunology. Volume Immune cell phenotyping and flow cytometric analysis: Am. Soc. Microbiology. 5. 1997. pp. 245–254. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bassoe CF. Processing of staphylococcus aureus and zymosan particles by human leukocytes measured by flow cytometry. Cytometry. 1984;5(1):86–91. doi: 10.1002/cyto.990050113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herant M, Heinrich V, Dembo M. Mechanics of neutrophil phagocytosis: experiments and quantitative models. J Cell Sci. 2006;119(Pt 9):1903–13. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Boer EC, Bevers RF, Kurth KH, Schamhart DH. Double fluorescent flow cytometric assessment of bacterial internalization and binding by epithelial cells. Cytometry. 1996;25(4):381–7. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0320(19961201)25:4<381::AID-CYTO10>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Posner RG, Savage PB, Peters AS, Macias A, DelGado J, Zwartz G, Sklar LA, Hlavacek WS. A quantitative approach for studying IgE-FcepsilonRI aggregation. Mol Immunol. 2002;38(16–18):1221–8. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(02)00067-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heinzelmann M, Gardner SA, Mercer-Jones M, Roll AJ, Polk HC., Jr Quantification of phagocytosis in human neutrophils by flow cytometry. Microbiol Immunol. 1999;43(6):505–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1999.tb02435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weersink AJ, Van Kessel KP, Torensma R, Van Strijp JA, Verhoef J. Binding of rough lipopolysaccharides (LPS) to human leukocytes. Inhibition by anti-LPS monoclonal antibody. J Immunol. 1990;145(1):318–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Innes NP, Ogden GR. A technique for the study of endocytosis in human oral epithelial cells. Arch Oral Biol. 1999;44(6):519–23. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9969(99)00027-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chaka W, Scharringa J, Verheul AF, Verhoef J, Van Strijp AG, Hoepelman IM. Quantitative analysis of phagocytosis and killing of Cryptococcus neoformans by human peripheral blood mononuclear cells by flow cytometry. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1995;2(6):753–9. doi: 10.1128/cdli.2.6.753-759.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Umino T, Skold CM, Pirruccello SJ, Spurzem JR, Rennard SI. Two-colour flow-cytometric analysis of pulmonary alveolar macrophages from smokers. Eur Respir J. 1999;13(4):894–9. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.1999.13d33.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.