Abstract

The inhibition of cysteine biosynthesis in prokaryotes and protozoa has been proposed to be relevant for the development of antibiotics. Haemophilus influenzae O-acetylserine sulfhydrylase (OASS), catalyzing L-cysteine formation, is inhibited by the insertion of the C-terminal pentapeptide (MNLNI) of serine acetyltransferase into the active site. 400 MNXXI pentapeptides were generated, docked into OASS active site using GOLD and scored with HINT. The terminal P5 Ile accounts for about 50% of the binding energy. Glu or Asp at position P4, and to a lesser extent, at position P3, also significantly contribute to the binding interaction. The predicted affinity of 14 selected pentapeptides correlated well with the experimentally determined dissociation constants. The X-ray structure of three high affinity pentapeptides-OASS complexes were compared with the docked poses. These results, combined with a GRID analysis of the active site, allowed us to define a pharmacophoric scaffold for the design of peptidomimetic inhibitors.

Introduction

Antibiotic resistance is one of the most alarming and potentially devastating health crises of the 21st century.1–3 After the successful development from 1945 to 1980 of numerous life-saving antibiotics with a broad spectrum of effectiveness against Gram negative bacteria, acquired bacterial resistance has caused several antibiotics to become useless or, at best, compromised in their ability to counteract bacterial infection. Furthermore, no new classes of antibiotics were introduced to the pharmaceutical market between 1962 and 19994, 5 and only three, oxazolidinones, cyclic lipopeptides and mutilins, after 2000.6–8 This limits the antibiotic arsenal available to treat an increasing number of bacterial infections, especially in hospital settings, where bacterial selection is more stringent. The complexity of the antibiotic resistome and the interplay between host and pathogen call for identification of novel targets and strategies for the development of potent and specific antibiotics.9, 10 A decrease in bacterial fitness at infection loci, caused by inhibition of metabolic enzymes, has been envisioned as a pursuable therapeutic strategy.11

Cysteine represents a key amino acid in both eukaryotes and prokaryotes because it constitutes a central building block for the biosynthesis of several important metabolites, such as methionine, coenzyme A, glutathione, and S-adenosylmethionine.12–14 The pathway of sulfur assimilation involves the conversion of sulfate to sulfide by the action of different enzymes (Scheme 1). The metabolic pathways responsible for synthesis of cysteine exhibit a high degree of divergence.14, 15 In plants and bacteria sulfur is incorporated into cysteine in an assimilatory reduction pathway. In vertebrates the enzymes involved in the de novo biosynthesis of cysteine are absent and such organisms rely on the reverse transsulfuration pathway (i.e., production of cysteine from methionine via homocysteine) to meet their metabolic needs for this amino acid. This pathway is also present in some protozoa, like Leishmania.16 Cysteine itself, although toxic at high concentrations, is the main antioxidant in parasitic protozoa like Trichomonas vaginalis.15 Genes involved in sulfur metabolism have been implicated in virulence17 and thus the inhibition of the corresponding gene products has been proposed to be pharmacologically relevant.18–20 For example, it has been demonstrated that cysteine biosynthesis is crucial for swarm-cell differentiation in Salmonella typhimurium and deletion mutants of the cysteine operon show decreased antibiotic resistance.21 Furthermore, the up-regulation of genes involved in sulfur metabolism is widespread among pathogens during the dormant phase,22, 23 in different developmental stages24–26 and in response to oxidative stress.27

Scheme 1.

Assimilatory pathway of sulfur incorporation into cysteine in enteric bacteria. Enzymes are shown in bold italics. Inhibition ( ) and activation (

) and activation ( ) of enzyme activities are shown in colour. Cysteine inhibits SAT and SAT inhibits OASS-A. OASS-A activates ATP sulfurylase.

) of enzyme activities are shown in colour. Cysteine inhibits SAT and SAT inhibits OASS-A. OASS-A activates ATP sulfurylase.

The final step of cysteine biosynthesis involves the reaction between sulfide and O-acetylserine via a β-replacement reaction catalyzed by the PLP-dependent enzyme O-acetylserine sulfhydrylase (OASS; EC 2.5.1.47) (Scheme 1).28 In microorganisms, two isoforms of OASS are present, originally referred to as OASS-A and OASS-B, the gene products of cysK and cysM, respectively. In enteric bacteria OASS-A is highly expressed at basal levels,29 whereas OASS-B is induced under anaerobic conditions,30 accounting for only 20% of cysteine synthase activity at most.31 OASS-B catalyzes also the synthesis of sulfocysteine from thiosulfate and O-acetylserine.

For microorganisms exploiting the assimilatory reduction pathway, a key regulatory step is the inhibition of OASS-A by serine acetyltransferase (SAT; EC 2.3.1.30) (Scheme 1). SAT interacts directly with OASS-A to form cysteine synthase, a bienzyme complex that leads to OASS-A inhibition32–34 and increased SAT activity.35 No inhibition by SAT has been reported for the OASS-B isoenzyme.36 The SAT-OASS interaction mechanism has been revealed at the molecular level by combining the information derived from detailed biochemical analyses36–40 and the three dimensional structure of SAT (Fig. 1a) and OASS-A (Fig. 1b) from S. typhimurium,41, 42 Haemophilus influenzae, 43, 44 Escherichia coli 45 and Arabidopsis thaliana. 46, 47 Furthermore, structures were determined for OASS-A from H. influenzae (hereafter referred to as HiOASS-A) complexed with the GIDDGMNLNI C-terminal decapeptide of SAT,48 OASS from A. thaliana (AtOASS) complexed with the C-terminal decapeptide of SAT, YLTEWSDYVI,47 and OASS-A from M. tuberculosis (MtOASS-A) complexed with the DFSI C-terminal tetrapeptide of SAT.49 As shown in Figure 1c, the SAT C-terminal peptide penetrates into the OASS active site, competing with the substrate O-acetylserine. However, only the last four amino acids were crystallographically detected, suggesting that the interactions between these residues and the active site are providing the predominant contribution to the binding free energy. In particular, biochemical studies of several modified decapeptides indicated that Ile276, the conserved SAT C-terminal amino acid, is essential for binding. Ile 276 makes several favorable contacts with the surrounding residues, including four hydrogen bonds between the carboxylate and Asn72, Thr73, Thr79 and Gln143, and hydrophobic interactions between the side chain and apolar groups (Fig. 1c, Scheme 2a).

Figure 1.

a. Ribbon-tube representation of HiSAT (PDB code 1sst).48 The C-terminal region (aa 241–267), including the peptide complexed with HiOASS-A (aa 258–267) is not shown in the picture since this region was not crystallographically detected. b. Ribbon-tube representation of HiOASS-A complexed with the SAT C-terminal tetrapeptide (PDB code 1y7l).44 c. HiOASS-A binding pocket. The SAT C-terminal tetrapeptide is represented in yellow sticks. The HiOASS-A residues forming H-bonds (white dashed lines) with the SAT peptide are shown in transparent white sticks. The binding pocket surface is displayed as a function of the lipophilic potential. Lipophilic regions are colored brown, whereas the polar cleft regions are progressively colored green, cyan and blue. Only essential hydrogens are shown.

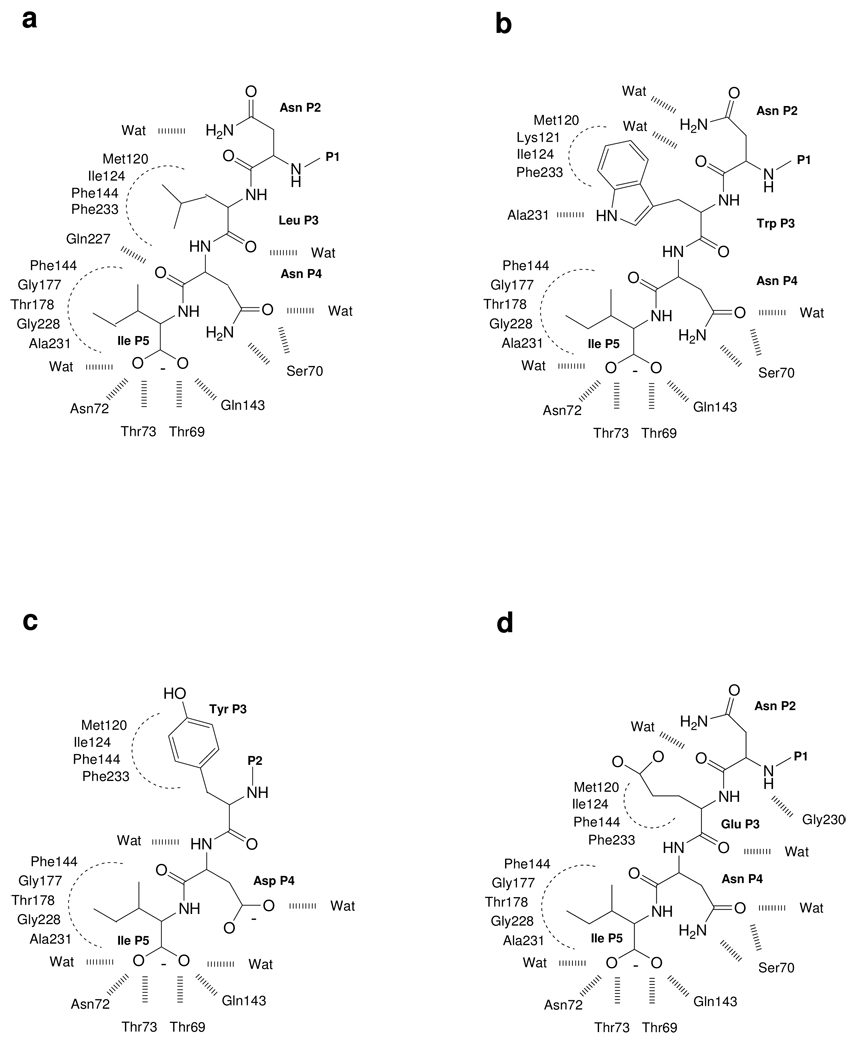

Scheme 2.

Interactions between the HiOASS active site residues and the peptides as derived from the crystallographic structure for complexes with: a. MNLNI; b. MNWNI; c. MNYDI; d. MNENI.

In the present work, we predict the binding free energy of 400 pentapeptides, MNXXI, interacting with the HiOASS-A active site using a combined docking-scoring procedure based on GOLD50, 51 and HINT.52–54 The free energy predictions were verified by the experimental determination of the binding affinity of 14 of these pentapeptides, selected for spanning a large range of predicted binding affinity and presenting charged, polar or apolar residues at mutation sites. Moreover, docked poses of three pentapeptides were compared to the conformations determined by X-ray crystallography. Overall, this study allows us to propose a validated pharmacophore that can serve as a basis for the design of peptidomimetic inhibitors of HiOASS-A with potential antibiotic activity.

Results and Discussion

Computational analysis

Energetic mapping of HiOASS-SAT peptide complexes

In the crystallographic structure of the complex between the HiSAT C-terminal decapeptide and HiOASS-A,48 only the last four amino acids NLNI were detected (Fig. 1c, Scheme 2a), indicating their relevance to the binding interaction and the concomitant lack of relevance for the other six, presumably disordered, residues. In order to determine the quantitative contribution of the individual SAT C-terminal residues with respect to the free energy of interaction with OASS, the HINT force field52 was used to deconvolve the interaction energies of the complex. Figure 2 illustrates the relative contributions of the four individual amino acids of the peptide interacting with the protein active site. The terminal Ile was found to account for about 80% of the total interaction energy, acting as an essential anchor point for the correct positioning of the C-terminal peptide. The major contributions of the terminal Ile267 (P5) to binding energy are largely derived from hydrogen bonds donated by Thr69 and Thr73 to its carboxylate (Scheme 2a). In addition, the Ile side-chain makes hydrophobic interactions in an apolar pocket formed by the PLP cofactor and Phe144. The C-terminal Ile residue is present in SAT sequences from different organisms36 and the essential role played by this residue in stabilization of the (OASS-A)-SAT complex is confirmed by mutagenesis experiments that show deletion of the Ile or its mutation to Ala to eliminate SAT binding to OASS.40, 47

Figure 2.

HINT score fraction (expressed as a percentage of the total HINT score value) assigned to the interaction between the different SAT C-terminal residues and the OASS-A binding pocket in the crystallographic HiOASS-A decapeptide complex.44

The amino acids at position P4 and P3, Asn266 and Leu265, contribute almost equally, accounting for about 10% of the total interaction energy, while the contribution of Asn264 (P2) is negatively scored, i.e., unfavorable (Fig. 2). It is interesting to note that the sequence alignment of γ-proteobacteria indicates that at P4/P3, either the Asn/Leu or Gly/Asp couple is observed (see Fig. 4 in36).

Figure 4.

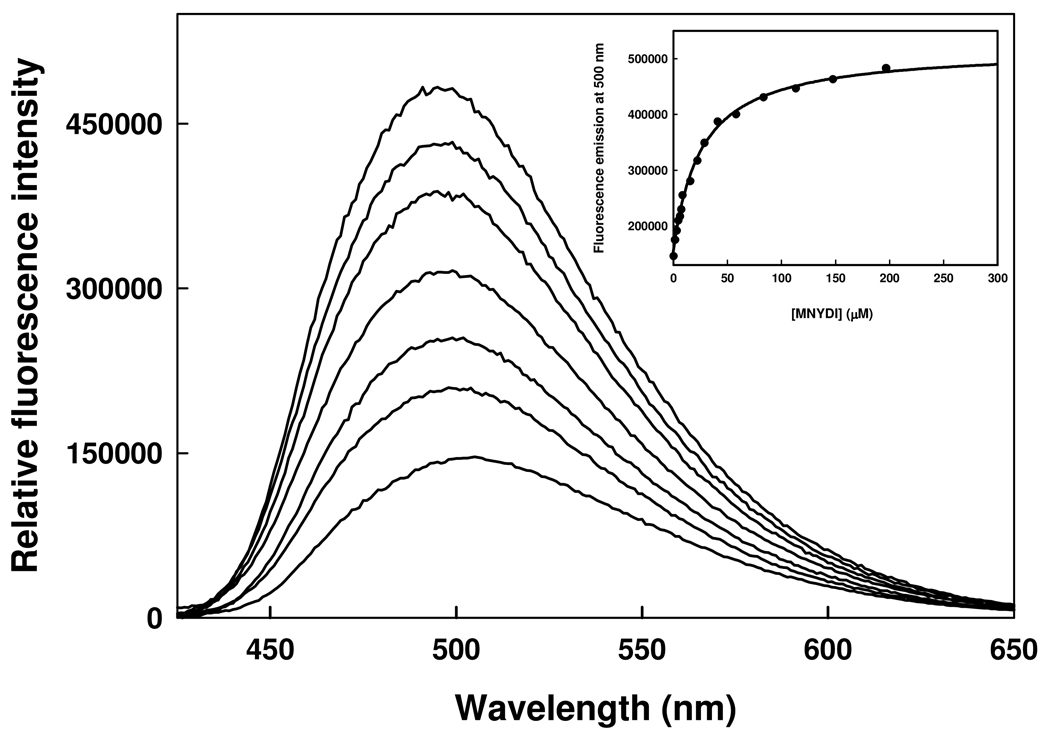

Binding of MNYDI to HiOASS. Fluorescence emission spectra upon excitation at 412 nm (slitex= 4 nm, slitem= 4 nm) of a solution containing 1 µM HiOASS and increasing concentrations of MNYDI in 100 mM Hepes buffer, pH 7, at 20°C. Inset. Dependence of the fluorescence emission intensity at 500 nm on the peptide concentration. Line through data points is the fit to a binding isotherm with Kd of 25.8 ± 1.7 µM.

Docking analysis

In order to design specific HiOASS-A inhibitors, we performed an in silico (virtual) screening of a library of pentapeptides, combining the GOLD docking program with the HINT scoring function. We have previously assessed the reliability of this combination of software tools55 for a variety of protein-ligand systems, and have independently confirmed its applicability in the OASS-A-pentapeptide system (see below). First, the SAT peptides were extracted from the OASS-A binding pocket of the three available crystal structures, i.e., HiOASS-A complexed with the last four residues of HiSAT (PDB code 1y7l),48 AtOASS complexed with the last eight residues of AtSAT (PDB code 2isq)47 and MtOASS-A complexed with the last four residues of MtSAT (PDB code 2q3c).49 Then, these peptides were docked into their corresponding binding pockets with GOLD. Given the flexibility of peptide ligands and the large number of rotatable bonds, significant and reproducible results were only obtained by applying distance and steric constraints aimed at reducing the degrees of freedom explored by the pose generation algorithm (see Materials and Methods). The best poses were selected using HINT scoring. The RMSD between docked and crystal conformations for the three structures was found to be lower than 2.0 Å, indicating that, with the applied constraints, the GOLD/HINT procedure is reliable for this system.

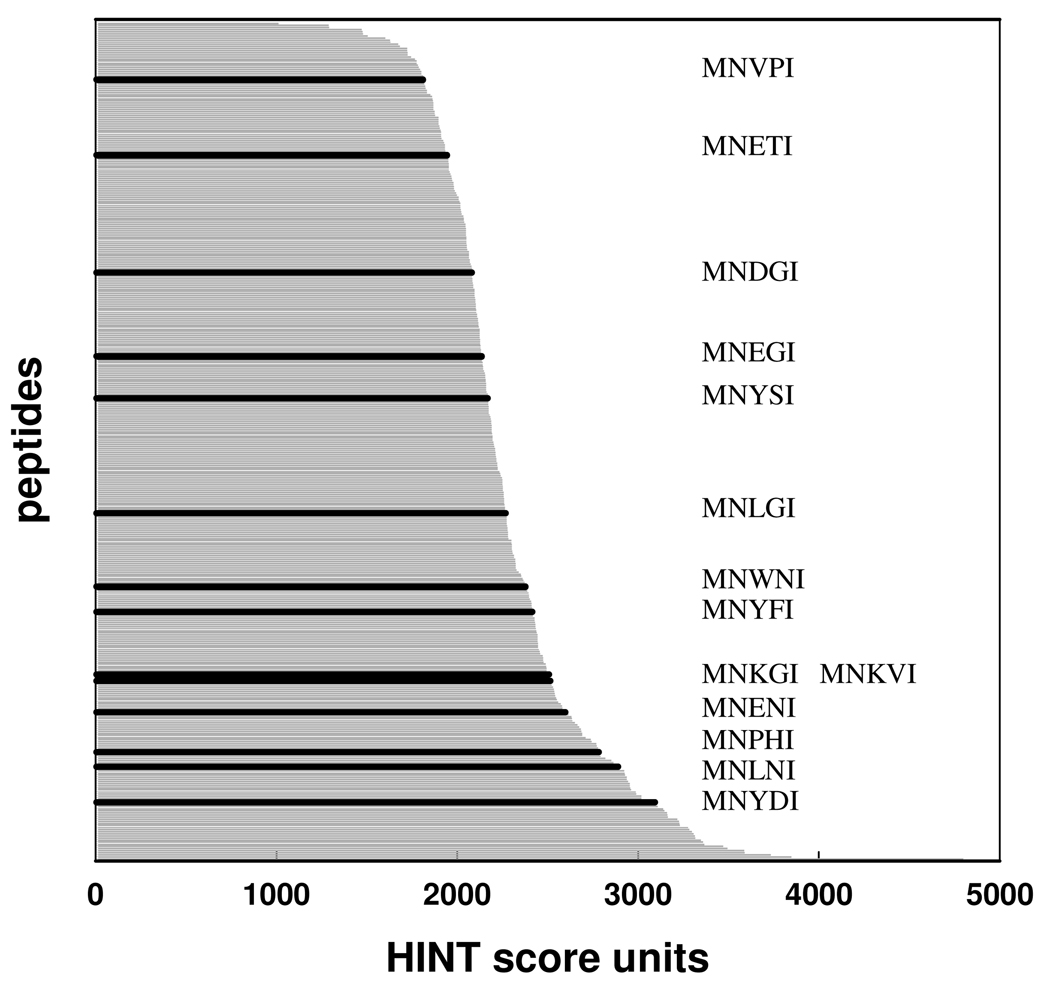

The potential 400 MNXXI pentapeptides were automatically generated, i.e., all possible permutations in the 3rd and 4th positions were modeled. To be consistent with the experimental findings40, 47 and the energetic mapping (Fig. 2), the terminal (P5) Ile was maintained in all pentapeptides. Similarly, the N-terminal Met and Asn were maintained to better simulate the intrinsic flexibility and occupancy of the native SAT C-terminal chain, even though they were demonstrated (Fig. 2) to be too far from key residues in the active site pocket to significantly affect binding. These 400 peptides were automatically docked into the HiOASS-A binding pocket and scored with both the GOLDScore fitness function and HINT. Since different conformations of the same molecule may coexist under biological conditions and contribute to the whole free energy of binding, a Boltzmann average calculation was applied, simultaneously considering the contributions of different conformations to the predicted free energy of binding. This procedure increased the accuracy of the computational analysis. The peptide pose showing the highest HINT score was retained as the best fitting candidate. The HINT score distribution of the 400 pentapeptides spans a range between about 1000 and 4000 (Fig. 3). In previous studies53, 56, HINT score differences have been shown to correlate with ΔΔG with a slope indicating that around 500 HINT score units correspond to 1 kcal mol−1 in free energy of association.

Figure 3.

HINT score values assigned to the interaction of the 400 MNXXI docked peptides and the HiOASS-A binding pocket. The HINT scores (grey lines) are reported in decreasing order. The pentapeptides experimentally tested are shown in black

Determination of binding affinity for selected pentapeptides

Among the 400 MNXXI peptides docked into HiOASS-A binding site and scored, 14 pentapeptides were selected to be experimentally tested (Table 1). These included the native SAT peptide (MNLNI), peptides bearing, at P3 and P4, hydrophobic, polar and positively or negatively charged residues, and peptides with both high and low HINT score values in order to obtain a general correlation between predicted and experimental binding affinities, and, thus, to evaluate the prediction capability of our procedure. The selected peptides were synthesized and their Kdiss values for HiOASS-A were determined by steady-state fluorescence titrations, exploiting the changes in the emission properties of PLP induced by ligand binding.36 A representative binding titration of MNYDI to HiOASS is shown in Fig. 4. The interaction of the pentapeptide with HiOASS-A causes an increase in the fluorescence emission intensity upon excitation at the wavelength of the PLP internal aldimine absorption band (412 nm) and a shift of the emission maximum from 509 to 493 nm, indicating a decrease in the polarity of the PLP environment upon peptide binding. The dependence of the fluorescence emission at 500 nm on pentapeptide concentration was fitted to a binding isotherm with Kdiss of 25.8 ± 1.7 µM (Fig. 4, Inset). The binding affinities for the selected pentapeptides are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Predicted HINT score values and experimentally determined dissociation constants Kd and pKd for the fourteen selected pentapeptides.

| Peptides | HINT score | Experimental Kd (µM) | pKd |

|---|---|---|---|

| MNLNI (wild type) | 2889 | 44.0 ± 3.6 | 4.36 |

|

|

2377 | 24.9 ± 3.6 | 4.60 |

|

|

3093 | 25.8 ± 1.7 | 4.59 |

|

|

2596 | 38.7 ± 2.8 | 4.41 |

| 2169 | 60.8 ± 8.7 | 4.22 | |

|

|

2416 | 191 ± 39 | 3.72 |

| 2267 | 570 ± 87 | 3.24 | |

| 2080 | 1030 ± 280 | 2.99 | |

| 2134 | 2270 ± 119 | 2.64 | |

| 1811 | 3330 ± 430 | 2.48 | |

|

|

1942 | 3420 ± 220 | 2.47 |

|

|

2783 | 7100 ± 1000 | 2.15 |

|

|

2515 | 13300 ± 700 | 1.88 |

|

|

2506 | 15200 ± 1250 | 1.82 |

HiOASS-peptide complex crystallized and determined crystallographically;

HiOASS-peptide complex crystallized but with peptide crystallographically undetectable;

peptide may form an intramolecular hydrogen bond that would preclude strong protein binding.

Correlation between predicted and experimental binding affinities of pentapetides to HiOASS-A

The correlation between the experimentally determined dissociation constants and the HINT scores (Htotal) for the 14 pentapeptides is shown in Figure 5. Data points were fitted to a linear regression, excluding the three outliers MNKGI, MNKVI and MNPHI, all containing positive, ionizable residues. The correlation is characterized by the equation:

with an r2 of 0.65 and a standard error of 0.54 pKdiss units.

Figure 5.

Correlation between the experimental pKd and the computational HINT scores for the 14 selected pentapeptides. The correlation is characterized by the equation pKdiss = 0.0018 Htotal – 0.60 with an r2 of 0.65 and a standard error of 0.54 pKdiss units.

The observed good correlation between HINT scores and the experimental values of pKdiss, indicates that the GOLD/HINT procedure is robust and permits the identification of specific HiOASS-A ligands. The use of the GOLDScore Fitness function (data not shown) yielded a potentially usable, but inferior, correlation with r2 = 0.44. Both correlations failed in the prediction for three peptides containing positive, ionizable residues, for which the interaction with HiOASS-A was significantly overestimated. The lysine amino group present in both MNKGI and MNKVI typically bears a positive charge under physiological conditions, while histidine, normally considered neutral, may be protonated on its imidazole nitrogen. Although the pKa of His is around 6, the presence of the nearby carboxy terminus could increase its ionizability due to charge-charge interactions. The presence of a positive charge on the third or on the fourth residue may induce the formation of a strong intramolecular salt bridge with the negatively charged carboxylic moiety of the terminal isoleucine within these peptides. The almost cyclic conformation of these peptides may preclude them binding to the HiOASS-A pocket, thus leading to the very high observed dissociation constants (Table 1). Also, for MNPHI, another possible explanation for its low affinity is that proline in P3 affects the peptide shape and dynamics, thus reducing the flexibility required to properly fit into the binding pocket.

Structure of HiOASS-Peptide Complexes

In order to support the predictions of the modeling, and to gain further insights into the conformation of peptides in the HiOASS-A binding pocket for design purposes, the structures of complexes formed by HiOASS-A and a subset of pentapeptides were determined by X-ray diffraction. The set of crystallized complexes included MNWNI, experimentally the best binder among the tested peptides (Table 1), and, in decreasing binding affinity order, MNYDI, MNENI, MNYFI, MNETI and MNKGI. Only the crystals for the three highest affinity HiOASS/peptide complexes (MNWNI, MNYDI and MNENI) yielded interpretable electron density for the peptide in Fo-Fc and 2Fo-Fc maps. This is largely explained by the inhibitory effect exerted by sulfate that significantly decreases the affinity of peptides both in solution and in the crystalline state. For example, in solution, MNENI exhibits a Kdiss of 38 µM (Table 1) and 2.5 mM, in the absence and presence of 500 mM ammonium sulfate, respectively, and a Kdiss of about 7 mM in the crystal, as determined by a fluorimetric titration on a HiOASS-A microcrystalline suspension (data not shown).

The structures of the HiOASS-peptide complexes (MNWNI, MNYDI and MNENI) were determined to 1.7 – 1.9 Å resolution with crystallographic R-factors of 16.5 – 17.2% (Table 2). Each structure includes residues 2–311 out of the 316 residues that comprise the monomer, and a single molecule of the PLP cofactor in a Schiff base linkage with Lys42 in the active site. In general, the bound peptides in these crystals displayed a trend toward greater order from their N- to C- termini. For this reason either one or two N-terminal residues of (MN)YDI, (M)NWNI and (M)NENI could not be modeled (residues not detected in the electron density maps enclosed in parentheses). The polypeptide chains of HiOASS-A in the three complexes superimpose nearly perfectly with one another and with the structure of HiOASS-A in complex with the decapeptide modeled as MNLNI.48 The main chain conformations of the (M)NWNI and (M)NENI peptides bound to HiOASS-A are also similar (Fig. 6a), but differ from that of (MN)YDI. However, in all three structures, the location and conformation of the C-terminal Ile residue at position P5 is identical. Similar to the description above, one oxygen of the C-terminal carboxylate group interacts with both a backbone amide nitrogen of an α-helix (Thr73) and a water molecule while the other oxygen atom interacts with the side chain hydroxyl of Thr69 and the carboxamide nitrogen of Gln143. However, the Asn P4 sidechain carboxamide group common to (M)NWNI and (M)NENI is hydrogen bonded to the hydroxyl and main chain amide of Ser 70, while the Asp P4 side chain carboxyl of (MN)YDI is directed toward solvent. This altered conformation leaves space for a sulfate ion to bind at the same location as the Asn P4 side chains of (M)NWNI and (M)NENI and to mimic the interactions of these residues with Ser70. The unique main chain conformation of (MN)YDI may be due to the participation of the Tyr at P3 in a favorable aromatic cluster with Phe144 and Phe233. The most relevant interactions formed by the native and by the mutated pentapeptides within the HiOASS-A binding pocket are reported in Scheme 2.

Table 2.

X-ray data measurement and refinement statistics.a

| Peptide | MNYDI | MNWNI | MNENI |

|---|---|---|---|

| PDB code | 3IQH | 3IQG | 3IQI |

| Data Measurement | |||

| resolution (Å) | 26.54 – 1.90 | 28.14 – 1.90 | 22.08 – 1.70 |

| space group | I41 | I41 | I41 |

| a (Å) | 112.153 | 112.474 | 112.264 |

| c (Å) | 45.728 | 45.928 | 45.835 |

| no. of observed reflections | 79664 | 86365 | 119157 |

| no. of unique reflections | 19121 | 21544 | 29196 |

| completeness (%) | 89.0 (69.5) | 99.2 (95.7) | 97.3 (85.9) |

| <I/σ(I)> | 21.6 (6.3) | 31.8 (8.6) | 28.1 (6.2) |

| Rmerge | 5.6 (23.0) | 2.9 (10.3) | 3.3 (15.2) |

| Peptide Residues Modeled | YDI | NWNI | NENI |

| Atoms | |||

| no. of protein atoms | 2321 | 2318 | 2318 |

| no. of cofactor atoms | 15 | 15 | 15 |

| no. of peptide atoms | 29 | 39 | 34 |

| no. of water/ions | 241 | 234 | 235 |

| Average thermal factor (Å2) | |||

| protein atoms | 17.0 | 18.8 | 14.4 |

| cofactor atoms | 10.2 | 13.0 | 8.8 |

| peptide atoms | 32.9 | 44.0 | 29.2 |

| water/ions | 27.6 | 29.2 | 23.7 |

| RMS deviation from ideality | |||

| bond lengths (Å) | 0.014 | 0.015 | 0.011 |

| bond angles (°) | 1.39 | 1.41 | 1.28 |

| R-factor (%) / R-free (%) | 16.5/20.9 (22.6/30.4) | 16.6/20.5 (20.9/28.0) | 17.2/20.4 (27.2/31.4) |

All structures contained the PLP cofactor and were modeled with either three or four residues of the included pentapeptide. Rmerge (%) = Σ| Ii − I | / Σ | Ii | × 100. Rfactor (%) = Σ |Fo − Fc|/Σ |Fo| × 100 for all available data, but excluding data reserved for the calculation of R free. Rfree (%) = Σ |Fo − Fc|/Σ |Fo| × 100 for a 5% subset of X-ray diffraction data omitted from the refinement calculations. Values in parentheses refer to the corresponding statistics calculated for data in the highest resolution bin.

Figure 6.

X-ray structures of MNWNI, MNYDI and MNENI bound to HiOASS and comparison with the conformations generated from docking/scoring. a. Superposition of the crystallographically determined structures of MNLNI (yellow), MNWNI (green), MNYDI (light blue) and MNENI (orange) within the HiOASS active site. b. MNWNI conformations generated from docking/scoring and determined crystallographically are displayed in magenta and green, respectively. c. MNYDI conformations generated from docking/scoring and determined crystallographically are displayed in magenta and light blue, respectively. d. MNENI conformations generated from docking/scoring and determined crystallographically are displayed in magenta and orange, respectively. For b–d the HiOASS active site is represented by a Connolly surface built with Sybyl MOLCAD tools and colored as a depth function. External protruding regions are colored blue, while cavities and clefts are progressively colored green, yellow and orange.

Comparison between docked poses and crystallographic conformations

To gain insight into the structural correlation between poses of pentapeptides originated by the GOLD/HINT procedure and the conformations determined by X-ray crystallography, the three available HiOASS-pentapeptide complexes were superimposed as shown in Figure 6b–d. Each of the structures is discussed in turn.

The structure of the binding site of the HiOASS-(M)NWNI complex is reported in Figure 6b. The crystallographic position of the peptide superimposes with the conformation predicted by docking. The terminal Ile at P5 occupies exactly the same location in both models, interacting with the protein through the deprotonated carboxylic moiety as described above. In both the docked and crystallographic models the Asn at P4 contacts the Ser70 hydroxyl through the side-chain amino group, whereas the carbonyl interacts with the backbone amino group of Ser70 and a second water molecule in the crystal. The backbone of the Trp at P3 occupies the same position, while the side chains, located in the same hydrophobic pocket, show different orientations in the two models. In the crystallographic model the Trp side chain interacts with the Ala231 carbonylic group through the nitrogen of the indole ring whereas in the docked model the Trp side chain forms a π−π interaction with the phenyl ring of Phe233. Finally, substantially different orientations are assumed by Asn at P2, which interacts with two water molecules in the crystal, while in the docking model it contacts the carbonyl moieties of Ile226 and Gly230, through its backbone NH and side chain amido groups, respectively. Overall, the protein residues in the binding site are quite similar in position, with the exception of Gln227, which closes the pocket in the docking model (as in the original 1y7l structure), while adopting the opposite orientation in the crystallographically-analyzed structures described here.

The superposition of the crystallographic structure and the docked model of the HiOASS-(MN)YDI complex is reported in Figure 6c. As previously noted, Ile P5 shows the same orientation in both models with the same hydrogen bonding network with Thr69, Asn72, Thr73 and Gln143, but with an additional water molecule in the crystal structure. A significant change, mainly due to the placement of a sulfate ion into the binding pocket, is observed at positions P4 and P3. In the docking model, the carboxylate of Asp at P4 interacts with the amino and the hydroxyl groups of Ser70, while the backbone carbonyl contacts the hydroxyl of Thr69 and the backbone NH of Gly71. In the crystallographic structure, the sulfate ion contacts both Ser70 and Gly71, displacing the Asp P4 carboxylate, forcing it to occupy a more central position interacting only with a couple of water molecules. This relocation of Asp P4 also induces a different orientation on Tyr P3 that partially places the aromatic ring in the hydrophobic pocket occupied by Tyr in the docking model forming a favorable π−π interaction with the side chain of Phe233.

The superposition of the crystallographic and docked models of the HiOASS-MNENI complex is shown in Figure 6d. Again, the terminal residue Ile at P5 occupies exactly the same location in both models, as does the following Asn at P4, interacting with the Ser70 hydroxyl through the side-chain amido group and with the backbone amide NHs of Ser70 and Gly71. However, in the docked model the backbone carbonyl of the Asn at P4 forms a strong hydrogen bond with the side chain of Gln227, while in the crystal structure this interaction is not seen because the Gln227 side chain has adopted a different orientation pointing towards the opposite side of the pocket. While not apparently involved in notable interactions, the Glu at P3 in the docked model is well aligned with the corresponding residue in the crystallographic structure. Not surprisingly, more significant deviations occur at the Asn at P2. In the crystal model the P2 backbone carbonyl forms an intramolecular hydrogen bond with the backbone NH of Asn P4, while in the docked model Asn P2 interacts with the backbone NH of Gly228.

HiOASS active site hot spots

To understand the key features of the target binding pocket architecture and the concomitant pharmacophoric properties of possible inhibitors, the individual energetic contributions of the P3, P4 and P5 amino acids of the 400 pentapeptides are reported in Fig. 7. The Ile at P5 generally provides a very positive HINT score for the 400 pentapeptides with a few variations attributable to small local adjustments of Ile P5 within the target binding pocket. The evident differences in H-bond lengths or other interactions are induced by the natural flexibility of peptidic ligands or by interactions with neighboring residues. This is the case, for instance, in the HiOASS-MNSKI complex where the peptide assumes an atypical orientation because the Lys in position P4 extends up to Asp67 and is thus located within an area not occupied by the other peptides. In some of the docked MNXDI and MNXEI peptides the energetic contribution of the P5 Ile is lower than the contributions made by Glu or Asp at P4. In particular, the hydropathic interaction analysis suggests that Glu at P4 contributes significantly to binding in MNAEI or MNGEI, as Asp in MNPDI and MNTDI. The energetic contributions of Glu and Asp originate from their interactions with the backbone and the side chain of Ser70 (Scheme 2). The important role of a P4 acid is somewhat surprising given the presence at P4 of Asn in the HiSAT C-terminal pentapeptide, substituted by Gly in other species.36 Although to a lesser extent, good contacts are also made at P4 by Asn, Gln and His. As described above, the peptides with Lys at P4 are likely to possess intramolecular hydrogen bonds that would preclude them from binding despite their high HINT scores.

Figure 7.

Mapping of the energetic contribution of the 400 pentapeptides. The black line represents the HINT scores attributed to the residues at position P3, the red line represents the sum of HINT scores at positions P3 and P4, and the cyan line represents the sum of HINT scores at positions P3, P4 and P5. The dotted line is the zero value.

The amino acids at P3 make at best small favorable contributions, but the trends are interpretable. Favorable contacts are given by apolar residues, like Ala, Gly, Ile, Leu, Phe, Pro, Trp and Val, which are more prone to occupy the hydrophobic cleft lined by Met120, Ile124, Phe144 and Phe233. Unfavorable contacts are given by polar and/or hydrogen bond donating residues such as Arg, Cys, Ser, Thr and, especially, by Asn, Asp, Gln, Glu and Tyr. In contrast, MNEGI, MNEII, MNETI and MNELI pair the carboxylic moiety of Glu in P3, which is sufficiently long to contact Ser70, which normally interacts with residues at position P4, with the apolar side chains of Gly, Ile, Thr and Leu at P4 that occupy the previously described hydrophobic cleft.

Overall, a good HiOASS-A peptidic binder should be able to place two H-bond acceptor groups, better if negatively charged, in positions P4 and P5, and a hydrophobic moiety at P3. For P5 the acceptor role is very well fulfilled by the C-terminal carboxylate, so the side chain of P5 does not need to be polar. It is instructive to compare the Structure-Activity Relations detailed above with Molecular Interaction Fields calculated by the GRID force field.57 This result is represented by the set of contours superimposed with the wild type SAT C-terminal tetrapeptide in Figure 8. Red contours, which correspond to favorable areas for placing an H-bond acceptor group, align well with the carboxylate moieties of Ile at P5 (contour a) and with an extension (contour b) delimited by Asn72, Gly228 and the PLP cofactor (residues not shown), where a water molecule has been crystallographically detected. A further favorable area for a putative negatively charged residue has been identified at position P4 (contour c). This contour extends towards Thr69, Ser70 and Thr91 (residues not shown), and is normally occupied by a water molecule in the crystallographic structure. A smaller favorable area has been also identified near one of the main hydrophobic contours (contour h) but outside of the binding pocket. Significant favorable regions for placing an H-bond donor group (identified by blue contours) are located near the CG2 methyl of the isobutyl side chain of Ile P5, probably because of proximity to the PLP phosphate (contour d), and to a lesser extent, at position P4 next to Asn side-chain nitrogen (contour c). Contour e, lined by Asp67, Ala68, Lys142 and Gln143, identifies a putative favorable site for placing either an H-bond donor or acceptor group. However, this region is too far from the crystallographic peptide binding site to be considered pharmacophorically relevant. Finally, three hydrophobic regions (green contours) are evidenced in the map: i) near the CD1 methyl of the P5 Ile side chain, positively interacting with Phe144 (contour f); ii) in a region close to Pro93 that is not occupied by any of the crystallographic or docked peptides (contour g); and iii) in the hydrophobic cleft delimited by Ile124, Phe144 and Phe233 in the proximity of the side chain of residue P3 (contour h). Together, these observations describe a pharmacophoric template that can be exploited for the design and development of non-peptidic inhibitors of HiOASS-A. A somewhat similar approach has been recently pursued on M. tuberculosis adenosine-5'-phosphosulfate reductase, an enzyme involved in sulfur assimilation and a validated target to develop new antitubercular agents, particularly for the treatment of latent infection. 58

Figure 8.

GRID Molecular Interaction Fields calculated for the HiOASS active site. The red, blue and green-colored contours correspond to the Molecular Interaction Fields calculated for H-bond acceptor (O), H-bond donor (N1) and hydrophobic (DRY) probes. The active site surface is represented as a function of the cavity depth while the wild type crystallographic SAT C-terminal tetrapeptide is shown in transparent capped sticks.

Conclusions

It is well understood that cysteine biosynthetic pathways are, although to a different extent, redundant in pathogenic microorganisms.59, 60 This observation has multiple consequences on the design of drugs targeting enzymes acting in these pathways. First, the inhibition of a pathway can induce the up-regulation of a compensating enzyme, thus decreasing drug potency. Second, redundancy points to the relevance of cysteine biosynthesis for microorganisms growth and virulence.17, 60 Third, different pathways are often up-regulated under different conditions and are unlikely to play the same role during different infection phases.24–26 OASS-A inhibition likely results in a decreased fitness of bacteria towards the environmental stresses present at infection loci due to the decrease in the availability of cysteine.24 For example, S. typhimurium, like M. tuberculosis, is capable of long term survival and persistent infection inside macrophages and is thus thought to have developed a large armory of anti-oxidant defenses against oxidative stress, mainly relying on cysteine.61 Striking examples of the relevance of cysteine biosynthesis on pathogens fitness are provided by the 500 fold decrease in antibiotic resistance, as measured by MIC, in the swarm state of S. typhimurium knock out for cysK,21 and by the partial block of Entamoeba histolytica trophozoites proliferation by inhibition of SAT.62 We have identified a series of HiOASS-A pentapeptide inhibitors with promising lead molecule properties. Further efforts underway include the development of peptidomimetic inhibitors based on these results that will be of potential interest as antibiotic agents.

Experimental Section

Chemicals

Chemicals, purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, were of the best available quality and used as received. Experiments, if not otherwise indicated, were carried out in 100 mM Hepes buffer, pH 7 at 20 °C.

Enzyme and peptides

HiOASS was overexpressed in E. coli BL21(DE3)/pET28a and purified by Ni-NTA affinity and Superdex 200 pg gel filtration chromatography as previously described.48

Pentapeptides used in the binding measurements were synthesized and HPLC-purified to > 95% (Sigma-Genosys and CRIBI, Padova, Italy). Peptides were synthesized on a segmented continuous-flow synthesis platform, from the C-terminus to the N-terminus using Fmoc chemistry and a solid support resin. Pentapetides were purified to > 95 % by reverse phase chromatography. The purified fractions were confirmed by analytical HPLC-mass spectrometry. Pentapetides were obtained as a lyophilized powder, dissolved in water or buffer and dialyzed against 100 mM Hepes buffer prior to use. The pentapeptides used in the crystallographic experiments, MNYDI, MNKGI, MNWNI, MNYFI, MNENI and MNETI, were also synthesized and HPLC-purified to > 95% (Genscript Corporation, Piscataway, NJ).

Computational analysis

Molecular modeling

The crystallographic structure of HiOASS-A, complexed with the SAT C-terminal decapeptide, was retrieved from the PDB48 (PDB code 1y7l). The structure was checked for chemically consistent atom and bond type assignments using the molecular modeling program Sybyl 7.3 (www.tripos.com). Amino and carboxy-terminal groups were set as protonated and deprotonated, respectively. Hydrogen atoms were computationally added using the Sybyl Biopolymer and Build/Edit menu tools, and energy minimized using the Powell algorithm, with a convergence gradient of ≤ 0.5 kcal (mol Å)−1 and a maximum of 1500 cycles.

Docking procedure

Docking of ligands was performed with the program GOLD, version 3.1 (CCDC; Cambridge, UK; www.ccd.cam.ac.uk). The SAT C-terminal peptide was removed from the HiOASS active site and a series of pentapeptides, automatically created with an SPL script executed within Sybyl, were docked in the binding pocket. While we explored unrestrained docking, structural considerations dictated the use of constraints. First, the active site pocket of OASS-A is notably larger than necessary to accommodate the bound peptides. Also, the high flexibility and the relatively large number of rotatable bonds of pentapeptides may negatively affect the binding mode predictions.63 Thus, conformational constraints were applied during the docking simulations. In particular, the hydrogen bonds formed between the carboxylic group of the SAT C-terminal Ile276 (P5) and the hydroxyl hydrogen of Thr69 and the backbone amide hydrogen of Thr73, located in the HiOASS binding pocket, were constrained to be within a distance range of 1.8–2.0 Å, as found in the crystallographic structures. Moreover, for each pentapeptide the α-carbon of Asn P2 was constrained to be within a sphere of defined radius from the corresponding atom in the template crystallographic structure (1y7l). Several docking runs were carried out with radii of 1.5, 2.0, 2.5 and 3.0 Å. The best results (vide infra) were obtained with the sphere radius set to 1.5 Å. This constraint avoids the unreliable generation of peptide poses bent towards the lower part of the binding pocket, a conformation not detected crystallographically. For each peptide 100 different poses were generated. A radius of 15 Å from the center of the active site was used to direct site location. For each GOLD docking search, a maximum number of 100000 operations were performed on a population of 100 individuals with a selection pressure of 1.1. Operator weights for crossover, mutation and migration were set to 95, 95 and 10, respectively. The number of islands was set to 5 and the niche to 2. The hydrogen bond distance was set to 2.5 Å and the vdW linear cut-off to 4.0 Å. The formation of intramolecular hydrogen bonds for the pentapeptide ligands was allowed. Polar hydrogen atoms in the binding pocket were allowed to optimize for hydrogen bonding during the docking simulations. The default GOLDScore fitness function50, 51 was utilized for the energetic evaluation during docking runs.

Hydropathic analysis

The software HINT (Hydrophatic INTeractions)52 was used as a post-docking processor tool.55, 64 Docked conformations generated by GOLD for each pentapeptide ligand were re-scored with HINT in order to predict the best binding mode. The HINT score provides an empirical, but quantitative, evaluation of a ligand-protein interaction as a sum of all single atom-atom interactions using the following equation:

where bij is the interaction score between atoms i and j, a the hydrophobic atomic constant, S the solvent accessible surface area, Tij a logic function assuming +1 or −1 values, depending on the nature of the interacting atoms, and Rij and rij are functions of the distance between atoms i and j.54 The HINT paradigm is based on the assumption that each bij is related to a partial δg value and that the HINT score is directly comparable to the global interaction ΔG°. Higher HINT scores correlate with more favorable binding free energies.53, 56, 65–67 For the protein, atom-based a and S parameters are obtained from a lookup dictionary keyed by residue type and solvent conditions. In this work each residue’s protonation state determined its solvent condition (i.e., local pH) using the “inferred” option. A HINT option that corrects the Si terms for backbone amide hydrogen atoms by adding 20 Å2 68 was used to improve the relative energetics of inter- and intra-molecular hydrogen bonds involving backbone amides. For the peptides the partitioning, i.e., assignment of the a and S values, was performed using the “calculate” method, an adaptation of the CLOG-P method of Leo.69 For both protein and ligand the “semi-essential” hydrogen mode was used. This mode treats polar hydrogen atoms and hydrogen atoms bonded to unsaturated carbon atoms explicitly. These hydrogen atoms were also allowed to act as hydrogen bond donors. Finally, the HINT scores for peptide conformations were Boltzmann averaged in order to weight the contributions given by the most probable conformations.70

Pharmacophore analysis

To identify the residues in the active site that are relevant for binding (“active site hot spots”) a GRID57 analysis using version 22a (www.moldiscovery.com) was performed. The number of planes per Å for the grid box (NPLA) was set to 3. The DRY probe was used to describe the potential hydrophobic interactions, while the sp2 carbonyl oxygen (O) and the neutral flat amino (N1) probes were used to evaluate the hydrogen bond donor and acceptor capacity of the target, respectively.

Determination of pentapeptide binding affinity to HiOASS-A

Pentapeptide binding to HiOASS was determined by monitoring the increase in fluorescence emission of the PLP cofactor at 500 nm following excitation at 412 nm.36 Emission spectra were collected at increasing pentapeptide concentrations in the presence of 1 µM HiOASS-A, 100 mM Hepes buffer at pH 7 (except for MNYFI, where pH 8 was used due to limited solubility. The dissociation constant of MNLNI for HiOASS-A is not significantly affected by pH in the range 7–9), 20°C. All spectra were corrected for the buffer contribution. Fluorescence measurements were carried out using a FluoroMax-3 fluorometer (HORIBA), equipped with a thermostated cell-holder.

The dependence on pentapeptide concentration of fluorescence emission was fitted to a binding isotherm:

where I is the observed fluorescence intensity, Imax is the maximum fluorescence change at saturating [L], [L] is the pentapeptide concentration, and Kdiss is the dissociation constant of the HiOASS-pentapeptide complex.

Crystallization of HiOASS/pentapeptide complexes

The concentration of pentapeptides used for crystallization was near their respective solubility limits in the crystallization solutions. For crystallization by the hanging drop vapor diffusion method, protein solutions containing each peptide were mixed with an equal volume of reservoir solution on a circular coverslip and inverted over sealed 1 mL reservoirs of 24 well Linbro plates.

HiOASS/MNYDI

The protein solution was 7.5 mg/mL HiOASS-A, 10 mM Hepes, pH 8.0, 25 mM NaCl, 8.8 mM peptide. The reservoir solution was 100 mM Hepes, pH 7.5, 2.1 M (NH4)2SO4 and 2% (w/v) polyethyleneglycol 400. Crystals were harvested from 5 µL hanging drops, swept rapidly through a cryoprotectant solution containing 0.1 M Hepes, pH 7.5, 1.4 M (NH4)2SO4, 0.7 M Li2SO4 and plunged into liquid nitrogen prior to X-ray data measurement.

HiOASS/MNKGI

The protein solution was 7.5 mg/mL HiOASS-A, 20 mM Hepes, pH 7.5, 20 mM NaCl, 12.5 mM peptide. The reservoir solution was 100 mM Hepes, pH 7.5, 2.0 M (NH4)2SO4 and 2% (w/v) polyethyleneglycol 400. Crystals were harvested from 5 µL hanging drops, swept rapidly through a cryoprotectant solution containing 0.1 M Hepes, pH 7.5, 2.2 M (NH4)2SO4, 50 mM NaCl, 20% (w/v) glycerol and plunged into liquid nitrogen prior to X-ray data measurement.

HiOASS/MNWNI

The protein solution was 7.5 mg/mL HiOASS-A, 10 mM Hepes, pH 7.5, 25 mM NaCl, 7.5 mM peptide. The reservoir solution was 100 mM Caps, pH 10.5, 1.75 M (NH4)2SO4 and 0.2 M Li2SO4. Crystals were harvested from 4 µL hanging drops, swept rapidly through a cryoprotectant solution containing 0.1 M Caps, pH 10.5, 1.7 M (NH4)2SO4, 0.2 M Li2SO4, 20% (w/v) glycerol and plunged into liquid nitrogen prior to X-ray data measurement.

HiOASS/MNYFI

The protein solution was 7.5 mg/mL HiOASS-A, 20 mM Hepes, pH 8.0, 20 mM NaCl, 12.7 mM peptide. The reservoir solution was 100 mM Hepes, pH 7.5, 1.9 M (NH4)2SO4 and 2% (w/v) polyethyleneglycol 400. Crystals were harvested from 5 µL hanging drops, swept rapidly through a cryoprotectant solution containing 0.1 M Hepes, pH 7.5, 2.2 M (NH4)2SO4, 50 mM NaCl, 20% (w/v) glycerol and plunged into liquid nitrogen prior to X-ray data measurement.

HiOASS/MNENI

The protein solution was 7.5 mg/mL HiOASS-A, 10 mM Hepes, pH 7.5, 25 mM NaCl, 9.4 mM peptide. The reservoir solution was 100 mM Hepes, pH 7.5, 1.8 M (NH4)2SO4 and 2% (w/v) polyethyleneglycol 400. Crystals were harvested from 4 µL hanging drops, swept rapidly through a cryoprotectant solution containing 0.1 M Hepes, pH 7.5, 1.65 M (NH4)2SO4, 0.5 M Li2SO4 and plunged into liquid nitrogen prior to X-ray data measurement.

HiOASS/MNETI

The protein solution was 7.5 mg/mL HiOASS-A, 20 mM Hepes, pH 7.5, 20 mM NaCl, 9.4 mM peptide. The reservoir solution was 100 mM Hepes, pH 7.5, 2.1 M (NH4)2SO4 and 2% (w/v) polyethyleneglycol 400. Crystals were harvested from 5 µL hanging drops, swept rapidly through a cryoprotectant solution containing 0.1 M Hepes, pH 7.5, 2.2 M (NH4)2SO4, 20% (w/v) glycerol and plunged into liquid nitrogen prior to X-ray data measurement.

X-Ray Data Measurement and Structure Determination

X-ray diffraction data were measured at 110 K using a Rigaku R-Axis IV++ image plate detector and RU-H3R rotating copper anode X-ray generator equipped with Osmic Blue optics and operating at 50 kV and 100 mA (Table 2). The X-ray diffraction data were reduced with MOSFLM.71 The crystals studied in this work were isomorphous to a previously studied tetragonal form of HiOASS-A in complex with a decapeptide.48 These atomic coordinates (PDB accession code 1y7l), with peptide atoms omitted, were used as the initial model for solving the crystal structures of the newly prepared HiOASS-A complexes by molecular replacement. Manual model building was with COOT72 and atomic parameter refinement was carried out using REFMAC73 of the CCP4 program package.74

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the financial support of the Italian Ministry of University and Research for an International Cooperation Grant to A.M., the U.S. National Institutes of Health GM071894 to G. E. K. and the Grayce B. Kerr endowment to the University of Oklahoma to support the research of P. F. C.

Abbreviations list

- AtOASS

Arabidopsis thaliana O-acetylserine sulfhydrylase

- AtSAT

Arabidopsis thaliana serine acetyltransferase

- Caps

3-(cyclohexylamino)-1-propanesulfonic acid

- Hepes

N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N’-2-ethanesulfonic acid

- HiOASS

Haemophilus influenzae O-acetylserine sulfhydrylase

- HiSAT

Haemophilus influenzae serine acetyltransferase

- MNLNI

HiSAT C-terminal pentapeptide Met-Asn-Leu-Asn-Ile

- MtOASS

Mycobacterium tuberculosis O-acetylserine sulfhydrylase

- MtSAT

Mycobacterium tuberculosis serine acetyltransferase

- PLP

pyridoxal 5’-phosphate

- StOASS

Salmonella typhimurium O-acetylserine sulfhydrylase

- StSAT

Salmonella typhimurium serine acetyltransferase

Footnotes

The X-ray structures of HiOASS-A in complex with peptides MNWNI, MNYDI and MNENI have been deposited in the RCSB Protein Data Bank with PDB ID codes 3IQG, 3IQH and 3IQI, respectively.

References

- 1.de Lencastre H, Oliveira D, Tomasz A. Antibiotic resistant Staphylococcus aureus: a paradigm of adaptive power. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2007;10:428–435. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Livermore DM. The need for new antibiotics. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2004;10 Suppl 4:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-0691.2004.1004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nikaido H. Multidrug resistance in bacteria. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2009;78:119–146. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.082907.145923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Conly J, Johnston B. Where are all the new antibiotics? The new antibiotic paradox. Can. J. Infect. Dis. Med. Microbiol. 2005;16:159–160. doi: 10.1155/2005/892058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spellberg B, Powers JH, Brass EP, Miller LG, Edwards JE., Jr. Trends in antimicrobial drug development: implications for the future. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2004;38:1279–1286. doi: 10.1086/420937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barbachyn MR, Ford CW. Oxazolidinone structure-activity relationships leading to linezolid. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2003;42:2010–2023. doi: 10.1002/anie.200200528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fischbach MA, Walsh CT. Antibiotics for emerging pathogens. Science. 2009;325:1089–1093. doi: 10.1126/science.1176667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kern WV. Daptomycin: first in a new class of antibiotics for complicated skin and soft-tissue infections. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2006;60:370–378. doi: 10.1111/j.1368-5031.2005.00885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coates AR, Hu Y. Novel approaches to developing new antibiotics for bacterial infections. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2007;152:1147–1154. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lynch SV, Wiener-Kronish JP. Novel strategies to combat bacterial virulence. Curr. Opin. Crit. Care. 2008;14:593–599. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e32830f1dd5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alksne LE, Projan SJ. Bacterial virulence as a target for antimicrobial chemotherapy. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2000;11:625–636. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(00)00155-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sekowska A, Kung HF, Danchin A. Sulfur metabolism in Escherichia coli and related bacteria: facts and fiction. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2000;2:145–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kessler D. Enzymatic activation of sulfur for incorporation into biomolecules in prokaryotes. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2006;30:825–840. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2006.00036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cooper AJ. Biochemistry of sulfur-containing amino acids. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1983;52:187–222. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.52.070183.001155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nozaki T, Ali V, Tokoro M. Sulfur-containing amino acid metabolism in parasitic protozoa. Adv. Parasitol. 2005;60:1–99. doi: 10.1016/S0065-308X(05)60001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williams RA, Westrop GD, Coombs GH. Two pathways for cysteine biosynthesis in Leishmania major. Biochem. J. 2009;420:451–462. doi: 10.1042/BJ20082441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wooff E, Michell SL, Gordon SV, Chambers MA, Bardarov S, Jacobs WR, Jr., Hewinson RG, Wheeler PR. Functional genomics reveals the sole sulphate transporter of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex and its relevance to the acquisition of sulphur in vivo. Mol. Microbiol. 2002;43:653–663. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02771.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Westrop GD, Goodall G, Mottram JC, Coombs GH. Cysteine biosynthesis in Trichomonas vaginalis involves cysteine synthase utilizing O-phosphoserine. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:25062–25075. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600688200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hussain S, Ali V, Jeelani G, Nozaki T. Isoform-dependent feedback regulation of serine O-acetyltransferase isoenzymes involved in L-cysteine biosynthesis of Entamoeba histolytica. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2009;163:39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2008.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Agren D, Schnell R, Oehlmann W, Singh M, Schneider G. Cysteine synthase (CysM) of Mycobacterium tuberculosis is an O-phosphoserine sulfhydrylase: evidence for an alternative cysteine biosynthesis pathway in mycobacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:31567–31574. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804877200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Turnbull AL, Surette MG. L-Cysteine is required for induced antibiotic resistance in actively swarming Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Microbiology. 2008;154:3410–3419. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2008/020347-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hampshire T, Soneji S, Bacon J, James BW, Hinds J, Laing K, Stabler RA, Marsh PD, Butcher PD. Stationary phase gene expression of Mycobacterium tuberculosis following a progressive nutrient depletion: a model for persistent organisms? Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2004;84:228–238. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2003.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schnappinger D, Ehrt S, Voskuil MI, Liu Y, Mangan JA, Monahan IM, Dolganov G, Efron B, Butcher PD, Nathan C, Schoolnik GK. Transcriptional Adaptation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis within Macrophages: Insights into the Phagosomal Environment. J. Exp. Med. 2003;198:693–704. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bhave DP, Muse WB, 3rd, Carroll KS. Drug targets in mycobacterial sulfur metabolism. Infect Disord Drug Targets. 2007;7:140–158. doi: 10.2174/187152607781001772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garzoni C, Francois P, Huyghe A, Couzinet S, Tapparel C, Charbonnier Y, Renzoni A, Lucchini S, Lew DP, Vaudaux P, Kelley WL, Schrenzel J. A global view of Staphylococcus aureus whole genome expression upon internalization in human epithelial cells. BMC Genomics. 2007;8:171. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grifantini R, Bartolini E, Muzzi A, Draghi M, Frigimelica E, Berger J, Ratti G, Petracca R, Galli G, Agnusdei M, Giuliani MM, Santini L, Brunelli B, Tettelin H, Rappuoli R, Randazzo F, Grandi G. Previously unrecognized vaccine candidates against group B Meningococcus identified by DNA microarrays. Nat. Biotechnol. 2002;20:914–921. doi: 10.1038/nbt728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang S, Deng K, Zaremba S, Deng X, Lin C, Wang Q, Tortorello ML, Zhang W. Transcriptomic Response of Escherichia coli O157:H7 to Oxidative Stress. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009;75:6110–6123. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00914-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kredich NM. Biosynthesis of cysteine. In: Neidhardt FC, editor. Escherichia coli and Salmonella. 2nd ed. Washington: ASM Press; 1996. pp. 514–527. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kredich NM. Regulation of L-cysteine biosynthesis in Salmonella typhimurium. I. Effects of growth of varying sulfur sources and O-acetyl-L-serine on gene expression. J. Biol. Chem. 1971;246:3474–3484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tai CH, Nalabolu SR, Jacobson TM, Minter DE, Cook PF. Kinetic mechanisms of the A and B isozymes of O-acetylserine sulfhydrylase from Salmonella typhimurium LT-2 using the natural and alternative reactants. Biochemistry. 1993;32:6433–6442. doi: 10.1021/bi00076a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakamura T, Kon Y, Iwahashi H, Eguchi Y. Evidence that thiosulfate assimilation by Salmonella typhimurium is catalyzed by cysteine synthase B. J. Bacteriol. 1983;156:656–662. doi: 10.1128/jb.156.2.656-662.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Droux M, Ruffet ML, Douce R, Job D. Interactions between serine acetyltransferase and O-acetylserine (thiol) lyase in higher plants - Structural and kinetic properties of the free and bound enzymes. Eur. J. Biochem. 1998;255:235–245. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2550235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kredich NM, Becker MA, Tomkins GM. Purification and characterization of cysteine synthetase, a bifunctional protein complex, from Salmonella typhimurium. J. Biol. Chem. 1969;244:2428–2439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mino K, Yamanoue T, Sakiyama T, Eisaki N, Matsuyama A, Nakanishi K. Effects of bienzyme complex formation of cysteine synthetase from Escherichia coli on some properties and kinetics. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2000;64:1628–1640. doi: 10.1271/bbb.64.1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kumaran S, Yi H, Krishnan HB, Jez JM. Assembly of the cysteine synthase complex and the regulatory role of protein-protein interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:10268–10275. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M900154200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Campanini B, Speroni F, Salsi E, Cook PF, Roderick SL, Huang B, Bettati S, Mozzarelli A. Interaction of serine acetyltransferase with O-acetylserine sulfhydrylase active site: evidence from fluorescence spectroscopy. Protein Sci. 2005;14:2115–2124. doi: 10.1110/ps.051492805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mino K, Hiraoka K, Imamura K, Sakiyama T, Eisaki N, Matsuyama A, Nakanishi K. Characteristics of serine acetyltransferase from Escherichia coli deleting different lengths of amino acid residues from the C-terminus. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2000;64:1874–1880. doi: 10.1271/bbb.64.1874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mino K, Imamura K, Sakiyama T, Eisaki N, Matsuyama A, Nakanishi K. Increase in the stability of serine acetyltransferase from Escherichia coli against cold inactivation and proteolysis by forming a bienzyme complex. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2001;65:865–874. doi: 10.1271/bbb.65.865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mino K, Yamanoue T, Sakiyama T, Eisaki N, Matsuyama A, Nakanishi K. Purification and characterization of serine acetyltransferase from Escherichia coli partially truncated at the C-terminal region. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 1999;63:168–179. doi: 10.1271/bbb.63.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhao C, Moriga Y, Feng B, Kumada Y, Imanaka H, Imamura K, Nakanishi K. On the interaction site of serine acetyltransferase in the cysteine synthase complex from Escherichia coli. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006;341:911–916. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.01.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Burkhard P, Rao GS, Hohenester E, Schnackerz KD, Cook PF, Jansonius JN. Three-dimensional structure of O-acetylserine sulfhydrylase from Salmonella typhimurium. J. Mol. Biol. 1998;283:121–133. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Burkhard P, Tai CH, Ristroph CM, Cook PF, Jansonius JN. Ligand binding induces a large conformational change in O-acetylserine sulfhydrylase from Salmonella typhimurium. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;291:941–953. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gorman J, Shapiro L. Structure of serine acetyltransferase from Haemophilus influenzae Rd. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 2004;60:1600–1605. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904015240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Olsen LR, Huang B, Vetting MW, Roderick SL. Structure of serine acetyltransferase in complexes with CoA and its cysteine feedback inhibitor. Biochemistry. 2004;43:6013–6019. doi: 10.1021/bi0358521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pye VE, Tingey AP, Robson RL, Moody PC. The structure and mechanism of serine acetyltransferase from Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:40729–40736. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403751200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bonner ER, Cahoon RE, Knapke SM, Jez JM. Molecular basis of cysteine biosynthesis in plants: structural and functional analysis of O-acetylserine sulfhydrylase from Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:38803–38813. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505313200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Francois JA, Kumaran S, Jez JM. Structural basis for interaction of O-acetylserine sulfhydrylase and serine acetyltransferase in the Arabidopsis cysteine synthase complex. Plant Cell. 2006;18:3647–3655. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.047316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huang B, Vetting MW, Roderick SL. The active site of O-acetylserine sulfhydrylase is the anchor point for bienzyme complex formation with serine acetyltransferase. J. Bacteriol. 2005;187:3201–3205. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.9.3201-3205.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schnell R, Oehlmann W, Singh M, Schneider G. Structural insights into catalysis and inhibition of O-acetylserine sulfhydrylase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Crystal structures of the enzyme alpha-aminoacrylate intermediate and an enzyme-inhibitor complex. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:23473–23481. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703518200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jones G, Willett P, Glen RC. Molecular recognition of receptor sites using a genetic algorithm with a description of desolvation. J. Mol. Biol. 1995;245:43–53. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(95)80037-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jones G, Willett P, Glen RC, Leach AR, Taylor R. Development and validation of a genetic algorithm for flexible docking. J. Mol. Biol. 1997;267:727–748. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kellogg EG, Abraham DJ. Hydrophobicity: is LogPo/w more than the sum of its parts? Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2000;35:651–661. doi: 10.1016/s0223-5234(00)00167-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cozzini P, Fornabaio M, Marabotti A, Abraham DJ, Kellogg GE, Mozzarelli A. Simple, intuitive calculations of free energy of binding for protein-ligand complexes. 1. Models without explicit constrained water. J. Med. Chem. 2002;45:2469–2483. doi: 10.1021/jm0200299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kellogg GE, Burnett JC, Abraham DJ. Very empirical treatment of salvation and entropy: a force field derived from log Po/w. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 2001;15:381–393. doi: 10.1023/a:1011136228678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Spyrakis F, Amadasi A, Fornabaio M, Abraham DJ, Mozzarelli A, Kellogg GE, Cozzini P. The consequences of scoring docked ligand conformations using free energy correlations. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2007;42:921–933. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2006.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Marabotti A, Spyrakis F, Facchiano A, Cozzini P, Alberti S, Kellogg GE, Mozzarelli A. Energy-based prediction of amino acid-nucleotide base recognition. J. Comput. Chem. 2008;29:1955–1969. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Goodford PJ. A computational procedure for determining energetically favorable binding sites on biologically important macromolecules. J. Med. Chem. 1985;28:849–857. doi: 10.1021/jm00145a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hong JA, Bhave DP, Carroll KS. Identification of Critical Ligand Binding Determinants in Mycobacterium tuberculosis Adenosine-5'-phosphosulfate Reductase. J. Med. Chem. 2009;52:5485–5495. doi: 10.1021/jm900728u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Burns KE, Baumgart S, Dorrestein PC, Zhai H, McLafferty FW, Begley TP. Reconstitution of a new cysteine biosynthetic pathway in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:11602–11603. doi: 10.1021/ja053476x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Soutourina O, Poupel O, Coppee JY, Danchin A, Msadek T, Martin-Verstraete I. CymR, the master regulator of cysteine metabolism in Staphylococcus aureus, controls host sulphur source utilization and plays a role in biofilm formation. Mol. Microbiol. 2009;73:194–211. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06760.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Agren D, Schnell R, Schneider G. The C-terminal of CysM from Mycobacterium tuberculosis protects the aminoacrylate intermediate and is involved in sulfur donor selectivity. FEBS Lett. 2009;583:330–336. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Agarwal SM, Jain R, Bhattacharya A, Azam A. Inhibitors of Escherichia coli serine acetyltransferase block proliferation of Entamoeba histolytica trophozoites. Int. J. Parasitol. 2008;38:137–141. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Erickson JA, Jalaie M, Robertson DH, Lewis RA, Vieth M. Lessons in molecular recognition: the effects of ligand and protein flexibility on molecular docking accuracy. J. Med. Chem. 2004;47:45–55. doi: 10.1021/jm030209y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Amadasi A, Cozzini P, Incerti M, Duce E, Fisicaro E, Vicini P. Molecular modeling of binding between amidinobenzisothiazoles, with antidegenerative activity on cartilage, and matrix metalloproteinase-3. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2007;15:1420–1429. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fornabaio M, Spyrakis F, Mozzarelli A, Cozzini P, Abraham DJ, Kellogg GE. Simple, intuitive calculations of free energy of binding for protein-ligand complexes. 3. The free energy contribution of structural water molecules in HIV-1 protease complexes. J. Med. Chem. 2004;47:4507–4516. doi: 10.1021/jm030596b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fornabaio M, Cozzini P, Mozzarelli A, Abraham DJ, Kellogg GE. Simple, intuitive calculations of free energy of binding for protein-ligand complexes. 2. Computational titration and pH effects in molecular models of neuraminidase-inhibitor complexes. J. Med. Chem. 2003;46:4487–4500. doi: 10.1021/jm0302593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Amadasi A, Spyrakis F, Cozzini P, Abraham DJ, Kellogg GE, Mozzarelli A. Mapping the energetics of water-protein and water-ligand interactions with the "natural" HINT forcefield: predictive tools for characterizing the roles of water in biomolecules. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;358:289–309. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.01.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Porotto M, Fornabaio M, Greengard O, Murrell MT, Kellogg GE, Moscona A. Paramyxovirus receptor-binding molecules: engagement of one site on the hemagglutinin-neuraminidase protein modulates activity at the second site. J. Virol. 2006;80:1204–1213. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.3.1204-1213.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hansch C, Leo A. Substituents constants for correlation analysis in chemistry and biology. New York: John Wiley and Sons Inc.; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Amadasi A, Surface JA, Spyrakis F, Cozzini P, Mozzarelli A, Kellogg GE. Robust classification of "relevant" water molecules in putative protein binding sites. J. Med. Chem. 2008;51:1063–1067. doi: 10.1021/jm701023h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Leslie AGW. Recent changes to the MOSFLM package for processing film and image plate data. Joint CCP4 + ESF-EAMCB Newsletter on Protein Crystallography 26. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 72.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 1997;53:240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Collaborative Computational Project. N. The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 1994;50:760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]