Abstract

Infection by pathogenic strains of Leptospira hinges on the pathogen’s ability to adhere to host cells via extracellular matrix such as fibronectin (Fn). Previously, the immunoglobulin-like domains of Leptospira Lig proteins were recognized as adhesins binding to N-terminal domain (NTD) and gelatin binding domain (GBD) of Fn. In this study, we identified another Fn-binding motif on the C-terminus of the Leptospira adhesin LigB (LigBCtv), residues 1708–1712 containing sequence LIPAD with a β-strand and nascent helical structure. This motif binds to 15th type III modules (15F3) (KD = 10.70 μM), and association (kon = 600 M−1 s−1) and dissociation (koff = 0.0129 s−1) rate constants represents a slow binding kinetics in this interaction. Moreover, pretreatment of MDCK cells with LigB1706–1716 blocked the binding of Leptospira by 39%, demonstrating a significant role of LigB1706–1716 in cellular adhesion. These data indicate that the LIPAD residues (LigB1708–1712) of the Leptospira interrogans LigB protein bind 15F3 of Fn at a novel binding site, and this interaction contributes to adhesion to host cells.

Keywords: Leptospira interrogans, Fibronectin, Type III modules, LigB

Introduction

Leptospirosis, caused by infection with pathogenic spirochete Leptospira spp., is a serious zoonosis with world-wide distribution [1]. These spirochetes usually penetrate through mucosal surfaces and/or skin wounds and disseminate to several organs, especially the kidney, liver, and lungs. Infection may lead to Weil’s disease, which results in liver failure (jaundice), renal failure (nephritis), pulmonary hemorrhage and/or meningitis [1]. Human leptospirosis is often waterborne, and most commonly occurs in tropical areas of the world [1] and remerging in the United States [2].

Many microbial pathogens produce Microbial Surface Components Recognizing Adhesive Matrix Molecules (MSCRAMM) to facilitate their colonization of host tissues during initial infection [3]. Pathogenic leptospires bind to mammalian cells, such as MDCK cells often via the extracellular matrix (ECM) and several adhesion molecules have been identified from Leptospira spp. [4–6].

Leptospiral immunoglobulin-like proteins, LigA and LigB, possess 12 and 13 immunoglobulin-like (Ig-like) domains are recognized as MSCRAMMs [7,8]. The binding of LigB to Fn is also modulated by calcium [9]. These studies indicate that Lig proteins are pivotal virulence factors of pathogenic Leptospira spp.

In previous studies, strong and mild affinity Fn-binding sites were located on LigB within Ig-like domains of LigB (LigBCen) and the C-terminal variable (LigBCtv) regions, respectively (Fig. 1A) [4,5]. Here, we have further localized the Fn-binding motif of LigBCtv to amino acids (AA) 1708–1712, this sequence binds to the 15F3. This significant inhibition of cell binding by this short peptide demonstrates the importance of this sequence in adhesion of the pathogen to target tissues.

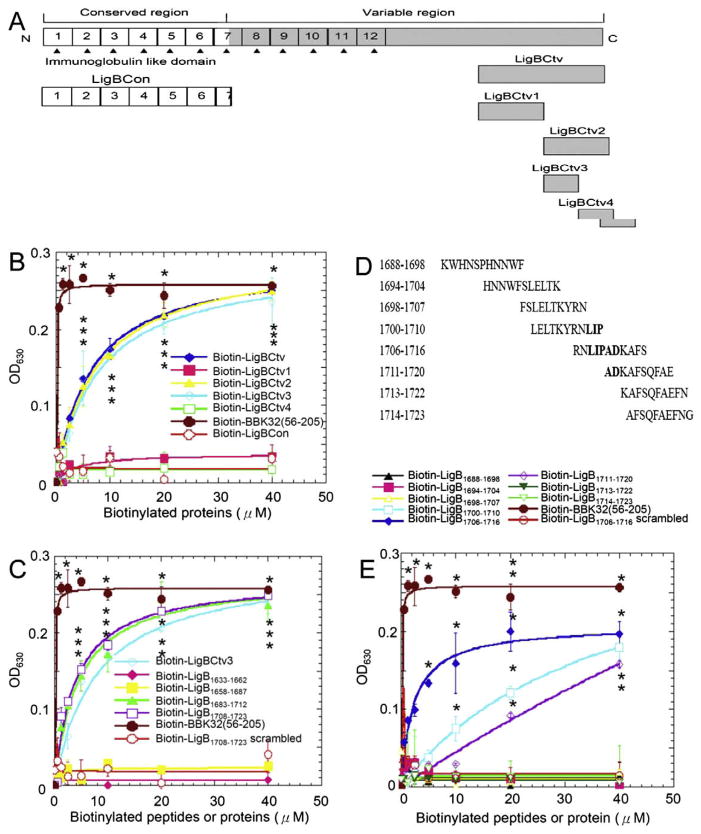

Fig. 1.

Identification of Fn-binding residues on LigBCtv. (A) A schematic diagram showing the truncated LigBCtv used in this study. (B) The Fn-binding activity of LigBCtv1, LigBCtv2, LigBCtv3, and LigBCtv4 regions. (C) The Fn-binding activity of the 30mers peptides from LigBCtv. (D) The synthetic peptide sequences (11mers) with overlapping regions used to identify the essential amino acids (indicated in bold) required for Fn binding. (E) The synthetic peptides indicated in (D) used in the Fn-binding assays. Various concentrations (40, 20, 10, 5, 2.5, 1.25, and 0.625 μM) of each tested biotinylated-protein or -peptide, -BBK3256–205 (positive control; B, C, and E), -LigBCon (negative control; B) or -scrambled peptide (negative control; C and E) were used in this study. Bound proteins or peptides were measured by ELISA.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains and cell culture

Leptospira interrogans serovar Pomona (NVSL1427-35-093002) was used as previously described [10]. Leptospires were grown in EMJH medium at 30 °C for less than five passages; growth was monitored by dark-field microscopy [10]. Madin–Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells (ATCC CCL34™) were cultured in Dulbecco’s minimum essential medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (GIBCO Laboratories, Grand Island, NY). Cells were grown at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2.

Reagents and antibodies

Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated streptavidin or goat anti-hamster antibody was purchased from Zymed (San Diego, CA) or Biosource (Camarillo, CA), respectively. FITC-conjugated streptavidin was purchased from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). Cell binding domain (CBD, 120 kDa) or 40 kDa domain (40 kDa) of Fn were purchased from Chemicon International (Temecula, CA). Anti-L. interrogans antibodies were previously prepared in hamsters from the challenge controls [10]. Full length human plasma Fn, N-terminal domain (NTD) or gelatin binding domain (GBD) of Fn were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO), and Biotin labeling kit were purchased from Pierce (Rockford, IL).

Plasmid construction and protein purification

Rat 12th–13th, 14th, or 15th type III modules were purified as maltose binding protein (MBP) fusion proteins (Fig. 3A) [11]. The DNA fragments of LigBCon and BBK32 (AA 56–205) were inserted into pGEX-4T-2 (GE, Piscataway, NJ) [10]. LigBCtv was analyzed with Jpred to predict the secondary structure for truncation construction. Constructs for the expression of GST fused with LigBCtv1 (AA 1418–1632), LigBCtv2 (AA 1633–1889), LigBCtv3 (AA 1633–1723) and LigBCtv4 (AA 1724–1889) were generated using the vector pGEX-4T-2 (Fig. 1A). Relevant fragments of DNA were amplified by PCR using primers (Supplemental Table 1) based on the ligB sequence [7]. Primers were engineered to introduce a BamHI or SalIsite at the 5′ end of each fragment and a stop codon followed by a SalI or NotI site at the 3′ end of each fragment. PCR products were digested sequentially with Bam-HI/SalI or SalI/NotI for the indicated fragment and then ligated into pGEX-4T-2. In this study, we purified the soluble form of the four GST fusion peptides from Escherichia coli as previously described [7].

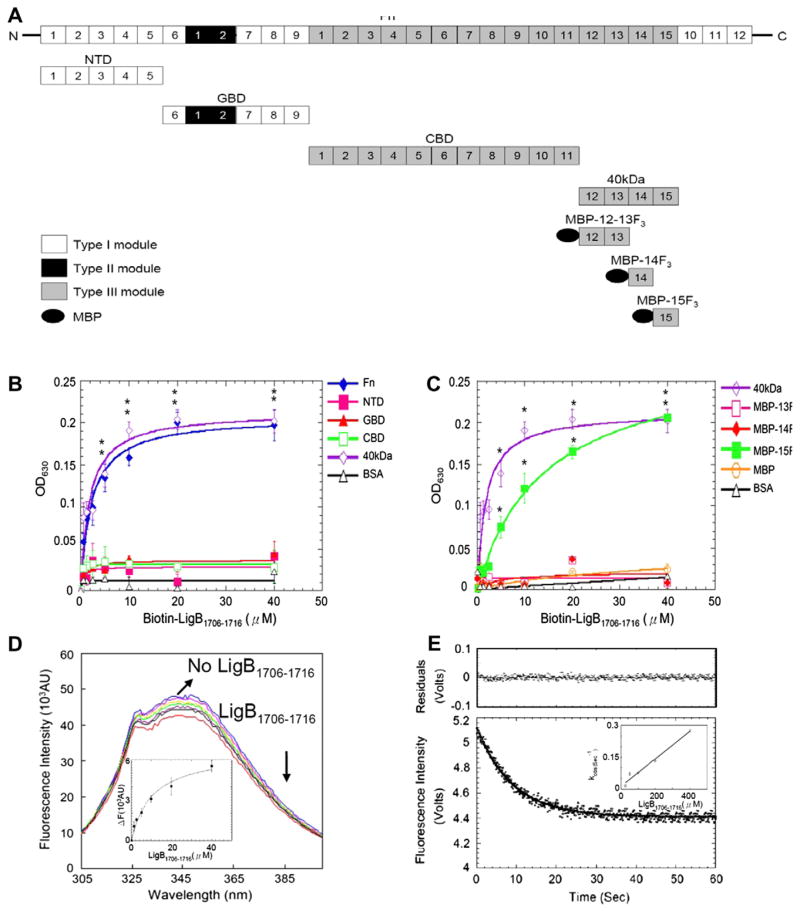

Fig. 3.

Mapping and characterization of LigB1706–1716 binding sites on Fn. (A) A chart presenting Fn and truncated Fn used in this study. (B,C) Various concentration (0.625, 1.25, 2.5, 5, 10, 20, 40 μM) of biotin-LigB1706–1716 or biotin (negative control and data not shown) were added to 1 μg of (B) Fn, NTD, GBD, CBD, 40 kDa, or BSA (negative control) (C) 40 kDa, MBP-12–13F3, MBP-14F3, MBP-15F3, MBP (negative control), or BSA (negative control) coated microtiter plate wells. Bound proteins were measured by ELISA. (D) 1 μM of 15F3 in PBS in the presence of 0, 0.625, 1.25, 2.5, 5, 10, 20 and 40 μM of LigB1706–1716 was excited at 295 nm to measure Trp fluorescence. Inner plot: KD of 15F3-LigB1706–1716 determined by monitoring quenching fluorescence intensities at 350 nm. (E) Stop flow experiment of 15F3 binding to LigB1706–1716. The signal represents the total fluorescence emission above 320 nm by excited at 295 nm. Inner plot: The kinetic plot of kobs versus concentration of 1 μM 15F3 under different LigB1706–1716 concentrations (25, 50, 100, 200, 400 μM).

Binding assays by ELISA

To determine the binding of truncated LigB (LigBCtv1, LigBCtv2, LigBCtv3, or LigBCtv4) or LigB peptides to Fn, 1 μg of Fn or BSA (negative control) was coated onto microtiter plate wells described previously [4,5]. Then, various concentrations (as indicated in Figs. 1 and 3) of biotinylated LigB truncated protein, LigB peptide (Figs. 1B, C, and E and 3), scrambled peptide (negative control, Supplemental Table 2), BBK32 (56–205) (positive control, [12] or LigBCon (negative control, [5]) was added to each microtiter plate wells for 1 h at 37 °C. To measure the binding of biotinylated LigB protein, HRP-conjugated streptavidin was added into microtiter plate wells (1:1000).

To identify the binding site of LigB1706–1716 on Fn, 1 μg of each full length Fn, NTD, GBD, CBD, 40 kDa domain of Fn, or MBP fused with 12th–13th type III modules (MBP-12–13F3), 14th type III modules (MBP-14F3), or 15th type III modules (MBP-15F3) of Fn and MBP (negative control) were coated onto microtiter plate wells. Then, various concentrations (as indicated in Fig. 3B and C) of biotin-conjugated LigB1706–1716 (biotin-LigB1706–1716) or biotin (negative control, data not shown) were added to microtiter plate wells. To measure the binding of LigB1706–1716 to MDCK cells, MDCK cells (105) were incubated with various concentrations (as indicated in Fig. 4A) of biotin-LigB1706–1716 or biotin (negative control) in 100 μl PBS for 1 h at 37 °C. To measure the binding inhibition of Leptospira to MDCK cells treated with LigB1706–1716, MDCK cells (105) were pretreated with various concentrations (as indicated in Fig. 4B) of biotin- LigB1706–1716 or biotin (negative control) in 100 μl PBS for 1 h at 37 °C. Then, the following steps such as the addition of Leptospira, plate washing, and the incubation and usage of antibodies were described previously [5]. To detect the binding of biotin-LigB1706–1716 or biotin to Fn or MDCK cells, HRP-conjugated streptavidin (1:1000) was added and incubated for 30 min at 25 °C. The measurement of the binding by ELISA was described previously [5].

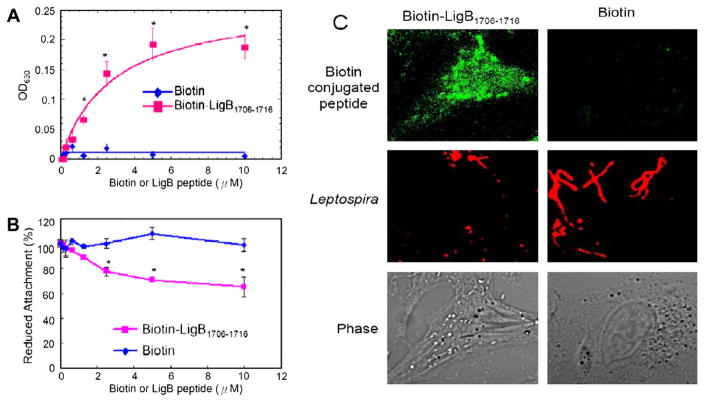

Fig. 4.

The binding of LigB1706–1716 to MDCK cells reduces leptospiral adhesion. (A) Various concentrations (0, 2, 4, 6, 8, or 10 μM) of biotin-LigB1706–1716, or biotin (negative control) were added to MDCK cells (105). (B,C) LigB1706–1716 inhibits the binding of Leptospira to MDCK cells. (B) MDCK cells (105) were incubated with various concentrations (0, 2, 4, 6, or 8, 10 μM) of biotin-LigB1706–1716, or biotin (negative control) prior to the addition of Leptospira (107). (A) The binding or (B) the reduced attachment was measured by ELISA. (C) The adhesion of Leptospira (108) or the binding of 10 μM of biotin or biotin-LigB1706–1716 to MDCK cells (106) was detected by CLSM.

NMR sample preparation and experiments

2.51 mM of cysteine conjugated LigB1703–1717 in PBS (pH 6.0) in either H2O or D2O was applied to NMR. NMR spectra were recorded at 25 °C on a Varian Inova 600 MHz spectrometer using the States-Haberkorn hyper-complex method of frequency discrimination [12]. Two-dimensional homonuclear total correlation spectroscopy (TOCSY) [13] and nuclear Overhauser enhancement spectroscopy (NOESY) [14] spectra were recorded with spectral widths of 6 kHz in t1 (1024 real + imaginary data points in the TOCSY and H2O NOESY experiments, 800 real + imaginary in the D2O NOESY experiment) and 8 kHz in t2 (2048 real + imaginary data points). Two-dimensional TOCSY spectra were acquired with a DIPSI-2 [15] isotropic mixing period (tmix) of 55 ms, and NOESY spectra were acquired with a tmix of 200 ms. For both experiments, the spectra were processed to a final data size of 1024 by 2048 real points.

NMR data were processed and analyzed using the software tools nmrPipe and nmrDraw [16]. Solvent subtraction was obtained by subtraction of a fourth-order polynomial fit in the time domain. The free induction decay (FID) was generally multiplied by a 72° shifted squared sine-bell function before zero-fitting and Fourier transformation. Linear baseline correction was applied in the acquisition dimension of all spectra. Analysis of the resulting TOCSY and NOESY spectra yielded proton resonance assignments for all 16 LigB-derived residues (Supplemental Table 3). Cys1 and Thr2 lack δHN assignments because of fast proton exchange of the N-terminal amino group.

Fluorescence spectrometry

Intrinsic fluorescence emission spectra were measured on a Hitachi F4500 spectrofluorometer (Hitachi, San Jose, CA). All conditions of recorded spectra were described previously [6]. For LigB1706–1716 titration, various concentrations of LigB1706–1716 (as indicated in Fig. 3D) was mixed with 1 μM of 15F3 of Fn and spectra were recorded after 5 min. To determine the dissociation constant (KD), the fluorescence intensities at 350 nm were recorded and fitted by using KaleidaGraph software (Version 2.1.3 Abelbeck software). All of the measurements were corrected for dilution and for inner filter effect.

Stopped-flow measurements

Stopped-flow measurements were performed using a KinTek stopped flow system (Austin, TX). Trp fluorescence emission above 320 nm was monitored using an excitation wavelength of 295 nm and a 320 nm cut-off filter at 25 °C. The stopped-flow experiments were performed by mixing Fn 15F3 in PBS after mixing with increased concentrations of LigB1706–1716; the time course of fluorescence intensity change was recorded by 1000 pairs of data in each experiment, and sets of data from three experiments were averaged. The apparent observed rate (kobs) was obtained by fitting the stopped-flow trace (average of five repeated runs) with a single exponential equation as shown follows.

| (1) |

where Ft is the fluorescence observed at any time, t, and A is the signal amplitude. F∞ is the final value of fluorescence, and kobs is the observed first order rate constant. The residuals were measured by the differences between the calculated fit and the exponential data. To calculate kon and koff of the binding reaction, the concentrations of LigB1706–1716 were at least 25-fold higher than that of 15F3 to fulfill the requirement of pseudo-first order so kobs obtained from different concentrations of LigB1706–1716 could fit the following equation to determine the value of kon and koff.

| (2) |

Binding assays by confocal laser-scanning microscopy (CLSM)

MDCK cells (106) were preincubated with 10 μM of biotin-LigB1706–1716 or biotin (negative control) as previously described [5]. Then, 150 μl of FITC-conjugated streptavidin was added (1:250). Fixation and immunofluorescence staining were followed as previously described [5]. Three fields were selected to count the number of binding organisms counted by an investigator blinded to the treatment group. To measure the reduced attachment of Leptospira. All studies were repeated three times.

Statistical analysis

Significance between samples was determined using the Student’s t-test following logarithmic transformation of the data. Two-tailed P-values were determined for each sample and a P-value < 0.05 was considered significant. Each data point represents the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of sample tested in triplicate. An (*) indicates the result was statistically significant.

Results

LigB residues 1708–1712 (LIPAD) possess Fn-binding activity

To identify the Fn-binding region, truncated LigBCtv including LigBCtv1, LigBCtv2, LigBCtv3, and LigBCtv4 (Fig. 1A) were assayed for Fn-binding capability using ELISA. Only LigBCtv2 and LigBCtv3 bound Fn (Fig. 1B). The Fn-binding region was more finely mapped to LigB residues 1688–1723 using synthesized peptides corresponding to the LigBCtv sequence (Fig. 1C). Then, peptides corresponding to AA 1688–1723 were also synthesized with overlapping regions of five amino acids (Fig. 1D and Supplemental Table 2). Eventually, LigB1706–1716 displayed the highest Fn-binding activity, while both LigB1700–1710 and LigB1711–1720 had moderate Fn-binding affinities (Fig. 1D). Based on the alignment of these three peptides, the residues LIPAD (LigB1708–1712) of LigBCtv were found to be essential for Fn binding (Fig. 1E).

β-Strand and nascent helical character are in the peptide containing the LIPAD motif

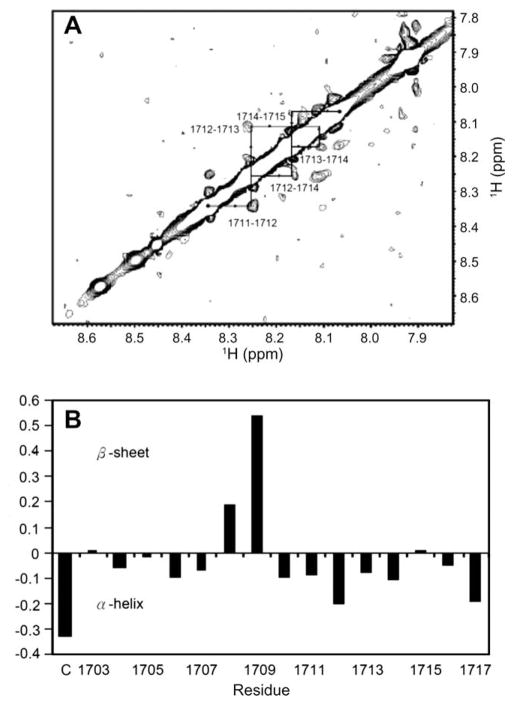

To reveal the structure of this Fn-binding motif, LigB1703–1717, the peptide containing LIPAD residues, was investigated with NMR. As shown in Fig. 2A, nuclear Overhauser effect (NOE) cross-peaks between successive amide protons, or dNN(i,i + 1) NOEs, were observed for residues A1711D1712K1713A1714F1715 in the NOESY spectra of LigB1703–1717. An additional cross-peak between the amide protons of D1712 and A1714, or dNN(i,i + 2) NOE, was also observed. This pattern of local NOEs is indicative of nascent helical structure, defined as an equilibrium between a series of turn-like structures and unfolded states [17]. Furthermore, the secondary structure of peptides can be elucidated by ΔδHα difference between an observed alpha protons chemical shift and the corresponding random coil value for a given amino acid residue [18]. As shown in Fig. 2B, ΔδHα values greater than +0.1 for sequential residues L1708 and I1709 (+0.19 and +0.54, respectively), indicating that this segment of the peptide may transiently adopt a β-strand conformation. This region is followed by a nascent helical region for residues A1711D1712K1713A1714 consistent with the nascent helical character deduced from the observed NOEs involving these residues as described above. The low value for cysteine, the first amino acid in the peptide (conjugated for mouse immunization) is most likely due to its position near the positive N terminus.

Fig. 2.

(A) HN–HN region of the homonuclear NOESY spectrum (tmix = 200 ms, pH 6.0) of LigB1703–1717 in PBS in H2O. The dNN cross-peaks are labeled with residue numbers, and arrows indicate sequential connectivities. The NOEs between sequential residues in residues A1711 through F1715 indicate nascent helical character. (B) Plot of the difference in Hα chemical shifts, or ΔδHα, between observed and random coil values for LigB1703–1717. (C) Indicated the first cysteine conjugated on LigB1703–1717. A stretch of ΔδHα values below −0.1 indicates nascent α-helical structure, and a stretch of values above 0.1 indicates preference for β-strand conformation.

The LigB LIPAD motif binds to the 15th type III module of Fn with slow binding kinetics

ELISA was also performed with biotin-LigB1706–1716 and full length or truncated Fn including NTD, GBD, CBD, and 40 kDa to identify the LIPAD-binding site on Fn. The results show that LigB1706–1716 binds to Fn and 40 kDa (Fig. 3B). Then, the ELISA applied to biotin-LigB1706–1716 with 40 kDa and MBP-12–13F3, MBP-14F3, MBP-15F3 further locate the LIPAD-binding site on 15F3 (Fig. 3C) in agreement with the quenching of the intrinsic Trp fluorescence intensity of 15F3 in the presence of LigB1706–1716 (KD = 10.70 ± 2.23 μM) (Fig. 3D). The kinetic rates of LigB1706–1716-15F3 determined by stop flow experiment (kon = 600 ± 12 M−1 s−1 and koff = 0.0129 ± 0.0003 s−1) are comparatively slow (Fig. 3E). These results indicate that the LIPAD motif binds to the 15F3 with a slow binding kinetics.

LigB1708–1712 LIPAD residues mediate the attachment of Leptospira to MDCK cells

To investigate the role of the LIPAD residues in cell binding, various concentrations of biotin-conjugated LigB1706–1716 or biotin were added to MDCK cells. Our results show that biotin-LigB1706–1716 binds to MDCK cells in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4A and C). Pretreatment of MDCK cells with biotin-LigB1706–1716 reduced the attachment of Leptospira by approximately 39% compared to either untreated (data not shown) or biotin-treated MDCK cells in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4B).

Discussion

Recently, it was shown that the some bacterial Fn-binding proteins binds to NTD by β zipper, two antiparallel β-strands [19], but some binds to the cationic cradle of the 13F3 [20]. Here, we show that the LIPAD motif of LigB binds to the 15F3, and this motif can also found in other Leptospira serovars and zonadhesin, an eukaryotic ECM binding proteins [21]. Our study describes for the first time a bacterial MSCRAMM binding to this module. These results suggest that LigB1706–1716 may exploit a novel Fn-binding mechanism.

The immunoglobulin-like repeat regions of LigA and LigB, including LigBCen2, strongly bind to the NTD and GBD [4,5]. This study identifies an Fn-binding LIPAD motif located in the C-terminal non-repeat region of LigB that slowly binds to the 15F3 with moderate affinity (KD = 10.70 μM, kon = 600 M−1 s−1, koff = 0.0129 s−1) (Fig. 3). The kinetic rates of LigB1706–1716 binding to the 15F3 are at least 100-fold slower than rates seen with other bacterial Fn-binding proteins [22]. The slow koff may be an important factor in retention of the bound state in the biological system. In an in vivo system where the concentration of ligand is not constant, but rather influenced by factors such as absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME), the residence time of a receptor–ligand complex is not necessarily appropriately described by the equilibrium dissociation constant KD [23]. Current experimental evidence has pointed to the dissociation rate constant koff as a more relevant parameter in some cases [24]. This has led to arguments that the koff may be an important parameter to consider in drug design and screening. In light of this, it is tempting to interpret the slow koff of the LigB1706–1716:Fn complex as an example of an evolutionarily optimized koff for a bacterial adhesin/target complex, which is challenged by many of the same limitations to overall ligand concentration as drug/target complexes are.

It has been indicated a ligB mutant with an insertion containing a Spcr cassette into the 3′ end of the ligB gene is still virulent in a hamster model [25]. The reasons are unknown. However, there are several possibilities: (1) LigB is only needed for initial adhesion and invasion of Leptospira moving from the environment through mucous membranes and injured skin. (2) The presence of other putative adhesins with potentially redundant functions. To answer these questions, further studies are needed.

We have demonstrated that the sequence LIPAD located on the C-terminus of LigB is an Fn-binding motif that interacts with the 15th type III module of Fn with slow binding kinetics, mediates cell adhesion, and displays β-strand and nascent helix character when free in solution. Work to further elucidate this interaction is in progress in our lab.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the Biotechnology Research and Development Corporation (BRDC), the Harry M. Zweig Memorial Fund for Equine Research, the National Science Foundation (L.K.N.), an NIH Biophysics Training Grant (A.I.G.), and the New York State Science and Technology Foundation. Thanks to Prof. B.U. Pauli for 12–13F3, 14F3, and 15F3 clones, Dr. Marci Scidmore for the using of CLFM and to Drs. Jeremiah Hanes’s assistance in stopped flow technique.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.08.089.

References

- 1.Faine SB, Adher B, Bolin C, et al. Leptospira and Leptospirosis. MedSci; Melbourne, Australia: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meites E, Jay MT, Deresinski S, et al. Reemerging leptospirosis, California. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:406–412. doi: 10.3201/eid1003.030431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schwarz-Linek U, Hook M, Potts JR. The molecular basis of fibronectin-mediated bacterial adherence to host cells. Mol Microbiol. 2004;52:631–641. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin YP, Chang YF. A domain of the Leptospira LigB contributes to high affinity binding of fibronectin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;362:443–448. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.07.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin YP, Chang YF. The C-terminal variable domain of LigB from Leptospira mediates binding to fibronectin. J Vet Sci. 2008;9:133–144. doi: 10.4142/jvs.2008.9.2.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Merien F, Truccolo J, Baranton G, et al. Identification of a 36-kDa fibronectin-binding protein expressed by a virulent variant of Leptospira interrogans serovar icterohaemorrhagiae. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2000;185:17–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2000.tb09034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Palaniappan RU, Chang YF, Hassan F, et al. Expression of leptospiral immunoglobulin-like protein by Leptospira interrogans and evaluation of its diagnostic potential in a kinetic ELISA. J Med Microbiol. 2004;53:975–984. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.45568-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Palaniappan RU, Chang YF, Jusuf SS, et al. Cloning and molecular characterization of an immunogenic LigA protein of Leptospira interrogans. Infect Immun. 2002;70:5924–5930. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.11.5924-5930.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin YP, Raman R, Sharma Y, et al. Calcium binds to leptospiral immunoglobulin-like protein, LigB and modulates fibronectin binding. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:25140–25149. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801350200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Palaniappan RU, McDonough SP, Divers TJ, et al. Immunoprotection of recombinant leptospiral immunoglobulin-like protein A against Leptospira interrogans serovar Pomona infection. Infect Immun. 2006;74:1745–1750. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.3.1745-1750.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheng HC, Abdel-Ghany M, Pauli BU. A novel consensus motif in fibronectin mediates dipeptidyl peptidase IV adhesion and metastasis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:24600–24607. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303424200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.States DJ, Haberkorn RA, Rubena DJ. Two-dimensional nuclear overhauser experiment with pure absorption phase in four quadrants. J Magn Reson. 1982;48:286–292. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bax A, Davis DG. MLEV-17 based two-dimensional homonuclear magnetization transfer spectroscopy. J Magn Reson. 1985;65:355–360. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bodenhausen G, Kogler H, Ernst RR. Selection of coherence transfer pathways in NMR pulse experiments. J Magn Reson. 1984;58:370–388. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2011.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shaka AJ, Lee CL, Pines A. Iterative schemes for bilinear operators; application to spin decoupling. J Magn Reson. 1988;77:274–293. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Delaglio F, Grzesiek S, Vuister GW, et al. NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J Biomol NMR. 1995;6:277–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dyson HJ, Rance M, Houghten RA, et al. Folding of immunogenic peptide fragments of proteins in water solution. II. The nascent helix. J Mol Biol. 1988;201:201–217. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90447-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wishart DS, Sykes BD, Richards FM. The chemical shift index: a fast and simple method for the assignment of protein secondary structure through NMR spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 1992;31:1647–1651. doi: 10.1021/bi00121a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schwarz-Linek U, Werner JM, Pickford AR, et al. Pathogenic bacteria attach to human fibronectin through a tandem beta-zipper. Nature. 2003;423:177–181. doi: 10.1038/nature01589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kingsley RA, Keestra AM, de Zoete MR, et al. The ShdA adhesin binds to the cationic cradle of the fibronectin 13FnIII repeat module: evidence for molecular mimicry of heparin binding. Mol Microbiol. 2004;52:345–355. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.03995.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hardy DM, Garbers DL. A sperm membrane protein that binds in a species-specific manner to the egg extracellular matrix is homologous to von Willebrand factor. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:26025–26028. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.44.26025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kreikemeyer B, Oehmcke S, Nakata M, et al. Streptococcus pyogenes fibronectin-binding protein F2: expression profile, binding characteristics, and impact on eukaryotic cell interactions. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:15850–15859. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313613200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Copeland RA, Pompliano DL, Meek TD. Drug-target residence time and its implications for lead optimization. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:730–739. doi: 10.1038/nrd2082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berezov A, Zhang HT, Greene MI. Disabling ErbB receptors with rationally designed exocyclic mimetics of antibodies: structure–function analysis. J Med Chem. 2001;44:2565–2574. doi: 10.1021/jm000527m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Croda J, Figueira CP, Wunder EA, Jr, et al. Targeted mutagenesis in pathogenic Leptospira species: disruption of the LigB gene does not affect virulence in animal models of leptospirosis. Infect Immun. 2008;76:5826–5833. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00989-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.