Abstract

Objective

The authors conduct a within intervention group analysis to test whether caregiver engagement (e.g., participation, homework completion, openness to ideas, apparent satisfaction) in a group-based intervention moderates risk factors for foster child outcomes in a state-supported randomized trial of caregiver parent training.

Methods

The intervention is delivered in 16 weekly sessions by trained leaders. Outcomes are pre–post change in problem behaviors and negative placements.

Results

Analysis of 337 caregivers nested within 59 parent groups show caregiver engagement moderates number of prior placements on increases in child problem behaviors, and moderates risk of negative placement disruption for Hispanics.

Conclusions

Variance in parent group process affects program effectiveness. Implications for practice and increasing effective engagement are discussed.

Keywords: intervention engagement, group-based intervention, foster care, multi-level modeling

In the growing field of implementation science, we need to understand what factors account for differential effectiveness across implementation settings. At present there is a gap in social service research regarding what we know about implementing effective services and what we know about treatment efficacy and evidence-based practice (Glisson, 2007). Evaluators have long argued for the need to understand how child, family, and intervention context contribute to differential responsiveness to treatments for children receiving services (Allen & Philliber, 2001; Hoagwood, Burns, Kiser, Ringeisen, & Schoenwald, 2001; Kazdin & Wassell, 1999). The goal of the present article is to examine differential effectiveness of a group-based intervention for foster parents aimed at reducing foster child behavior problems by examining the level of engagement foster parents achieved in the parent intervention groups.

Interventions that are delivered in groups add another layer of complexity to understanding the differential responsiveness of individual participants. It is often an assumption in large scale implementation studies that programs are universally implemented across settings, sites, and time. Yet it is likely that variance in the delivery of a program across agencies, geographic locations, or individually run groups contribute to differential effectiveness. Recent attention has been paid to understanding whether group factors such as participation, engagement, acceptance of the treatment, and satisfaction account for variance in treatment outcomes during implementation (Hogue, Liddle, Singer, & Leckrone, 2006).

Factors that influence the group context such as engagement and reactions of group members may influence the level of benefit that the individual participant obtains from the intervention. Compared with reviews of singular participant or group leader factors such as negative mood or negative interpersonal process, less is known about how group context influences outcomes; and in particular, how group context may interact with participant characteristics (Walrath, Ybarra, & Holden, 2006). Understanding multiple contributions and interactions is especially important when conducting services-based effectiveness research in community settings where there is great heterogeneity in child risk and functioning, family backgrounds, and type of services received (Glisson, 2007). Variance during implementation such as group engagement, openness to new ideas, and willingness to change could be as fundamental as the intervention curriculum in determining what is effective in real world settings.

Presently, we address the question of whether variation in caregiver engagement in intervention groups buffers known risk factors for foster children such as pretreatment behavior problems and a prior history of placement disruptions. We also include foster parent factors associated with outcomes such as kinship status, race–ethnicity, negativity, and ethnic match with the group leader. The intervention under study is Project KEEP (keeping foster parents trained and supported) based on Multidimensional Treatment Foster Care (MTFC) and Parent Management Training (PMT) approaches. MTFC involves multiple levels of intervention and wrap-around services including individualized treatment for children; whereas the KEEP program in this report was based solely on parent training delivered in 16 weekly parent groups.

Project KEEP Findings

KEEP was a group-based intervention for state-supported foster parents tested in a randomized clinical trial with 700 foster and kinship parents of children aged 5 to 12 (Chamberlain et al., 2006; Price et al., 2008). Findings to date in three published studies have focused on characteristics of participants, risk factors, and primary effectiveness. An analysis of the control condition families only demonstrated that baseline child behavior problems predicted subsequent placement disruption from foster homes (Chamberlain et al., 2006). Specifically, six or more child behavior problems reported by the foster parent during brief daily telephone interviews significantly amplified the likelihood of subsequent negative placement disruptions. A subsequent effectiveness analysis showed that KEEP significantly reduced the daily rates of child behavior problems for intervention families compared with control families. Furthermore, effective parenting mediated the association between the intervention and reductions in child behavior problems (Chamberlain et al., 2008). In addition, there was a group by initial risk interaction; families who reported a greater number of baseline child behavior problems benefited more from intervention than those reporting fewer problems.

A third study examined KEEP effectiveness on placement outcomes and found that children’s prior placement history predicted negative placement disruptions 6.5 months following baseline (Price et al., 2008). Furthermore, the KEEP intervention significantly increased positive placements and buffered the effect of prior placement history on negative placement disruptions for the intervention families relative to controls. Taken together, this set of KEEP studies not only demonstrated the program’s effectiveness in preventing negative placement and behavioral outcomes, but demonstrated additional benefits for higher risk children (those with greater behavior problems or a greater number of prior placements).

In the present study, we advance prior KEEP evaluations by examining parent group differences at the group level during implementation of the intervention. More specifically, we test whether group engagement moderates child or foster parent characteristics. To do this, we focus solely on the experimental group (only those foster families who were randomly assigned to receive the KEEP intervention). In order to deliver the KEEP intervention to over 350 randomly assigned families, families were enrolled in separately conducted parent groups with from 3–10 families per group participating. We therefore employed a multi-level modeling framework flexible enough to estimate family level and group level effects accounting for the clustering of participants in separate groups. We next briefly review child, parent, and group context factors that have been identified in previous research with foster care outcomes.

Foster Child and Parent Risk Factors

Child behavior problems and history of previous placement disruptions are key risk factors for negative outcomes for children in foster care (Chamberlain et al., 2006; Newton, Litrownik, & Landsverk, 2000). Among other risk factors identified in systematic evaluations of foster care, children’s age and sex have some consistency in the literature. Clark and colleagues (1998) found that boys and older children demonstrated differential improvement in externalizing behaviors and placement stability, respectively, in a randomized trial comparing foster care with case management with standard foster care services. Similarly, in a foster care intervention study for infants and toddlers, Dozier et al. (2006) found fewer behavior problems reported by parents for older children compared with younger children. Related, in a study contrasting young children in a normative community sample with children placed in foster care, Leve, Fisher, and DeGarmo (2007) found that the level of behavior problems prior to school entry predicted later poor peer relations for girls but not for boys.

Parent and child race–ethnicity and concomitant social disadvantage are associated with treatment outcomes, treatment needs, and implementation effectiveness (Berger, McDaniel, & Paxson, 2005; Zambrana & Capello, 2003). For example, one national study found that minority children were four times as likely as matched nonminority children to deteriorate in child adjustment after 6 months of involvement in systems of care (Walrath, Ybarra, & Holden, 2006). Race and ethnicity can be particularly salient for intervention and treatment programs when considering linguistic needs and ethnic match of treatment providers. Several studies have shown that ethnic and language match of participants with therapists is associated with greater attendance and lower likelihood of premature termination or dropout (Hall, 2001; Schoenwald, Halliday-Boykins, & Henggler, 2003; Sue, Fujino, Hu, Takeuchi, & Zane, 1991). To date, we are aware of no studies investigating how ethnic matching of group leaders may affect implementation in groups for foster parents. Finally, kinship care is also associated with foster child outcomes. Children in kinship care have more stable placements (i.e., they disrupt from placement less often) and reunify with biological parents less frequently (Berrick, 1998; Price et al., 2008).

Intervention Group Context

Existing studies of implementation effectiveness have focused primarily on site, agency, or therapist adherence to intervention curricula (Holden, Connor, Brannan, Foster, & Blau, 2002; McMillan, 2007). Findings on group leaders indicate that therapist experience and negative leadership style are associated with group process, satisfaction, dropout, and individual outcomes (Oie & Browne, 2006; Roback, 2000). Little is known about the role of other important group factors in group-based foster parent interventions such as the KEEP study. Data from the KEEP intervention were collected at each group session on each foster or kin caregiver’s level of engagement for each session. For example, group leaders rated parent’s level of participation, openness to the intervention ideas, satisfaction with the intervention methods, and their completion of homework practice which was designed to target key interactions between the foster parents and the children placed in their homes. Leaders also rated caregivers’ negative mood at each session.

Based on the risk factors highlighted in literature above, we hypothesized that variance in group context (defined by the level of engagement in parent groups) would moderate the effect of potential risk factors such as children’s pre-treatment behavior problems, prior history of placement disruptions, ethnic match of foster parent, age, and sex in predicting change in children’s problem behaviors and probability of a negative placement. Caregiver factors included kinship status, race–ethnicity, ethnic match of group leader, and mood. Alpha was set at .05. Because some children exited the home by termination assessment, analyses addressed two basic hypotheses:

For children who had not exited the home and had pre–post intervention data, we expected that higher levels of group engagement would beneficially moderate risk factors on change in children’s problem behaviors.

For all children enrolled in the intervention groups, we expected that higher levels of group engagement would beneficially moderate risk for a negative placement disruption.

Method

Procedures and Participants

The KEEP study was a collaboration among the San Diego County Department of Health and Human Services, the Oregon Social Learning Center, and the Child and Adolescent Services Research Center. The final sample for the full study was determined by eligible families that agreed to random assignment, completed signed informed consent procedures, and participated in a baseline assessment. Data in the present report focused only on participants randomly assigned to the intervention condition. Recruitment of participants was facilitated by data systems from the social service agency that were reviewed on a weekly basis to identify eligible children and foster families. Eligible study participants included all foster and kinship parents receiving a new placement of a child from the San Diego County Department of Health and Human Services child welfare system between 1999 and 2004. Eligibility requirements were (a) the child had been in either a kin or nonkin foster care placement for a minimum of 30 days; (b) the child was between the ages of 5 and 12; and (c) the child was not considered “medically fragile” (that is, not severely physically or mentally handicapped). Once deemed eligible, families were randomly assigned to either the intervention or to the control (case worker services as usual) condition.

All recruitment, consent, and research procedures were approved jointly by the Institutional Review Board for the protection of human participants (IRB) of the San Diego State University for the Center for Adolescent Services Research Center and by the IRB at the Oregon Social Learning Center. At the home interview foster parents received a detailed project description, consent information, a Participant’s Bill of Rights, and an IRB approved consent forms. The resulting sample comprised 700 foster child families, 359 intervention, and 341 services as usual (34% kinship placements, 66% non-relative placements). The sample was ethnically diverse, comprising 21% African American, 33% Latino, 22% Caucasian, 22% mixed ethnic, 1% Asian American, and 1% Native American children.

Data for this within intervention group report are from those foster parents and children who were randomly assigned to the “intent to treat” intervention condition and who attended group sessions and therefore had group exposure and session data (n = 337, 94% of 359 intent to treat intervention cases). In comparing attendee and non-attendee foster parents, there were no significant differences in children’s behavior problems, prior risk factors, age, or sex, or other risk factors included in the analyses. No differences were obtained for caregivers with the exception of age; older caregivers were more likely to attend groups (M = 50.29, SD = 43, and M = 43.29, SD = 14.69, p <.05).

The pre–post intervention study design included a 5-month post-baseline intervention termination assessment. The full sample was recruited in overlapping groups from September 2000 to February 2004. Assessment interviewers were blind to random assignment. By intervention termination assessment, 29% of intervention children had exited the home (Price et al., 2008). By termination, 81% of the foster parents were retained in the study whether the original focal child exited the home or not. Attrition analysis on all child variables revealed no significant differences at baseline between those intent to treat families with pre–post data and those lost to follow-up. Attrition analyses on foster parent variables revealed that there was a higher proportion of kin caregivers for those retained compared to those lost to follow-up (37% and 21%, respectively, χ2 (1) < 9.68, p <.01). No other differences were observed on foster parent variables. There was no differential attrition by group assignment in the full KEEP study (Chamberlain et al., 2008).

Intervention

Participants in the intervention group received 16 weeks of training, supervision, and support in behavior management methods. The intervention was implemented by paraprofessionals with no prior experience with the MTFC behavior management model or other parent-mediated interventions. Rather, experience with group settings, interpersonal skills, motivation, and knowledge of children were given high priority in selecting interventionists. Interventionists were trained during a 5-day session and supervised weekly where session videotapes were viewed and discussed.

The treated 337 caregivers were nested in 59 intervention groups consisting of 3 to 10 foster parents. Each group was conducted by a trained leader–facilitator and co-facilitator. Curriculum were designed to map on to protective and risk factors that were been found in previous studies to be developmentally relevant malleable targets for change (Eddy & Chamberlain, 2000). Sessions were structured so that the curriculum content was integrated into group discussions and primary concepts were illustrated via role-plays and videotaped recordings. Home practice assignments were given that related to the topics covered during sessions in order to assist parents in implementing the behavioral procedures taught in the group meeting. The leaders were trained and supervised to keep the group atmosphere pleasant, upbeat, and positive and to reinforce parents’ problem solving and discussions of parenting strategies and to minimize discussions about the deficits of the child welfare system, caseworkers, or the severity of child psychopathology. If foster parents missed a parent-training session, the material was delivered during a home visit (20% of the sessions). Such home visits have been found to be an effective means of increasing the dosage of the intervention for families who miss intervention sessions (Reid & Eddy, 1997).

Parenting groups were conducted in community recreation centers or churches. Childcare was provided. Several strategies were used to maintain attendance including (a) provision of childcare, using qualified and licensed individuals, so that parents could bring younger children and know that they were being given adequate care; (b) credit was given toward yearly licensing requirement for foster care; (c) parents were reimbursed $15 per session for travel expenses; (d) refreshments were provided. Attendance rates were high: 81% completed 80% or more of the group sessions, and 75% completed 90% or more of the group sessions.

Measures

Child Outcomes

The Parent Daily Report Checklist (PDR: Chamberlain & Reid, 1987) was a 30-item summative index of child behavior problems reported by parents during a series of consecutive or closely spaced repeated telephone interviews 1 to 3 days apart at baseline and termination. At each assessment, parents reported whether the behavior happened at least once or did not occur, yes or no, to the following question, “Thinking about (child’s name), during the past 24 hours did any of the following behaviors occur?” (e.g., argue, talk back, fight, lie). The PDR was designed to avoid aggregate recall or estimates of frequency thought to bias estimates (Stone, Broderick, Kaell, DelesPaul, Porter, 2000) and has been used in previous outcome studies (e.g., Kazdin & Wassell, 1999; McClowry, Snow, Tamis-Lemonda, 2005). It has convergent validity with observed behaviors in the home (Weinrott, Bauske, & Patterson, 1979). The PDR scores were computed by summing the number of behaviors reported per day (of a possible 30) on each call and dividing by the number of calls. Inter-call alpha reliability of the PDR was .84 at baseline and .83 at termination.

The second outcome was negative placement disruption for children exiting the home (yes–no). Foster parents were asked at intervention termination assessment if the child had remained in the home or had moved. Assessors coded the reason for exiting. Negative placement disruptions were defined by negative reasons for the exit from the home such as being moved to another foster home, a more restrictive environment such as a psychiatric care or juvenile detention center, or child runaways.

Child and Foster Parent Characteristics

Number of Prior Placements was obtained from available case files indicating the life-time placement histories of each child; and Age of child was measured in years since birth. Categorical contrasts included Sex of child coded 0 for females and 1 for males. Foster parents reported on their age and race-ethnicity coded 0 and 1 to reflect African Americans, Hispanics, and European Americans; Kinship Status was 0 and 1 to reflect placement with a relative. Foster parent-group leader Ethnic Match was scored by comparing the group leader’s race–ethnicity for each session to each foster parent’s race–ethnicity. The majority of groups were conducted by racial and ethnic minority group leaders. For example, there were a total of 5,392 individual possible sessions for attending families to participate in (337 × 16); of those, 2% were conducted by group leaders of European American decent, 33% by an African American, and 53% by a Hispanic group leader. In most cases, the group leader was the same primary group leader for each session; however, there were also instances of group leaders differing over the course of 16 weeks. Therefore, the group leader ethnic match was computed as the proportion of match across all 16 sessions. The observed score ranged from 0 to 1, with an average ethnic match of 61% (SD = .47). Finally, therapists rated negative mood of caregivers for that specific session using a scale of 1(Not at all) to 5 (Very much). Mood was log transformed due to a right skewed distribution.

Intervention Group Context

Kin or foster parent caregiver engagement was rated after each session with Likert-type items rated by group leaders on a scale form 1 (Not at all) to 5 (Very much). Six items were submitted to an exploratory principal components factor analysis with varimax rotation aggregated across all sessions. The overall engagement score in analyses to follow was the mean level across intervention sessions. One factor was extracted obtaining an eigenvalue greater than 2.00 with loadings from .62 to .94 (Eigenvalue = 2.82). The items defining the factor were level of participation in group process, caregiver was open to ideas presented, seemed satisfied with session, and implemented homework practice. We defined the obtained 4-item scale score as group engagement (α =.81). Two items, was supported by group and was confronted by group did not load or converge with the engagement factor and were eliminated.

Analytic Strategy for Multilevel Within Intervention Group Analysis

We specified multi-level models using hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) in the HLM6 program. HLM is a hierarchical regression framework accounting for the clustering or nesting of persons within groups (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002). Also known as mixture modeling, HLM estimates group level (Level 2) and individual level (Level 1) influence on child outcomes. HLM can also test whether group level variables interact with or moderate effects of an individual level predictor (e.g., Level 2 × Level 1 interaction). Another advantage of HLM is the ability to estimate binary outcomes as the probability of an outcome or the log odds. For the pre–post design, we specified the HLM regressions as an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) with post intervention termination behaviors as outcomes controlling for pre intervention behaviors. More specifically, regression slopes are first estimated in HLM for each individual at the caregiver–child level at Level 1 and then are summarized within each separate intervention group at Level 2. The Level 1 child outcomes are then regressed on predictors as a function of an intercept (β0), baseline problem behaviors (β1), and any foster parent or child characteristic entered as a predictors (β2....n), plus an error term. The Level 2 model estimates variation across parent intervention groups, or the variance in child outcomes and variance in Level 1 β predictors across groups plus an error term. In our models, a significant effect of group context (e.g., engagement) on a Level 1 predictor represents a moderating effect of engagement, or simply a Group Engagement × Foster Parent-Child interaction. Using the same structure, the probability of a negative placement is a function of Level 1 and Level 2 variables, or the log odds of a negative placement.

Results

Means and standard deviations for study variables are shown in Table 1. Both the mean score for group process and the constituent items from the factor analysis are presented. We next evaluated the “unconditional” model estimating intercepts across levels with no predictors entered in the model. The estimated variance components provide information to determine variance attributable to intervention groups. Results are shown in Table 2. Only higher level variance components are tested for significant variation above the lower level, in this case the Level 2 variance for parent groups. Variance attributed to groups is computed as the group variance component divided by the total variance which is also the intra-class correlation (ICC) for parent groups. In this study, 7% of the variance in child behavior problems measured with the PDR was attributed to significant variation across the parent intervention groups. Four percent of the variance in negative placement disruption was accounted for by the ICC for parent groups, although this variation was marginally significant. The next set of analyses focused on prediction of the daily reported behavior problems and probability of negative placement disruptions.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Study Variables at Family and Parent Group Level (n = 59 Groups, 337 Foster Parents and Children)

| Intervention Group Engagement (Level 2, n = 59) | ||

|---|---|---|

| M | SD | |

| Mean scale score | 3.67 | .26 |

| Foster parent level of participation | 3.82 | .29 |

| Foster parent was open to ideas presented | 3.81 | .33 |

| Foster parent seemed satisfied | 3.73 | .30 |

| Foster parent implemented homework-practice | 3.30 | .36 |

| Foster Child and Foster Parent (Level 1 n = 337) | ||

| PDR Problem Behaviors Baseline | 5.94 | 4.18 |

| PDR Problem Behaviors Post Intervention | 4.25 | 3.85 |

| Foster Child Age | 8.87 | 2.20 |

| Foster Child Sex (male) | .50 | |

| Number of Prior Placements | 2.98 | 3.10 |

| European American | .23 | |

| African American | .30 | |

| Hispanic | .43 | |

| Foster parent age | 50.30 | 11.51 |

| Ethnic match foster parent-foster child | .67 | |

| Ethnic match foster parent-group leader | .61 | |

| Kinship caregivers | .32 | |

| Foster Parent Mood | 1.07 | .09 |

| Negative Placement Disruptiona | .13 |

Note: The n size for negative placement disruption includes all children in intervention group at baseline, else data are for families with pre-post data who have not experienced a placement during the study. PDR =Parent Daily Report.

PDR =Parent Daily Report.

Table 2.

Multilevel Variance Components and Intra-Parent Group Correlation for Unconditional Modela

| Daily Behavior Problems (PDR) | Negative Placements | |

|---|---|---|

| Variance Component | ||

| Level 1 Foster Parents | 13.80 | .11 |

| Level 2 Parent Groups | 1.02* | .004† |

| % Total Variance or | ||

| Intra-Parent Group Correlation | .07 | .04 |

Note: Only Level 2 variance components are tested

p <.05

p =.07

Change in Problem Behaviors

Results for prediction of pre–post problem behaviors are shown in Table 3 using unstandardized regression coefficients. Model 1 displays effects for the foster parent and child level predictors at Level 1. The second column (Model 2) adds the effect of group engagement at the group level interacting with, that is, predicting, or moderating, the respective family level predictors. None of the hypothesized family level risk factors obtained significant prediction of change in problem behaviors at the .05 alpha level. The group level hypothesis was supported for prior placement history. Focusing on Model 2 in the right hand column, group engagement significantly moderated prior placement history (β = −.74, p <.05). The finding indicated that if a child had high numbers of prior placements, the intervention was more effective if foster parents had high levels of engagement in intervention groups but was not as effective if the parents exhibited low levels of engagement.

Table 3.

Multilevel Model of Pre-Post Intervention Foster Child Behavior Outcomes (Unstandardized Coefficients, n = 231 Families, n = 59 Groups).

| Post Intervention Problem Behaviors (PDR) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |

| Problem Behaviors Pre Intervention Score | 0.59*** | 0.59*** |

| Foster Child Age | −0.12 | −0.16 |

| Foster Child Sex (male) | 0.40 | 0.40 |

| Number of Prior Placements | −0.10 | −0.13* |

| Foster Parent- African American | 0.66 | 1.02 |

| Foster Parent- Hispanic | 0.73 | 1.07 |

| Foster Parent Age | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| Ethnic Match Foster Parent-Child | 0.22 | 0.25 |

| Ethnic Match Foster Parent-Group Leader | −0.51 | −0.56 |

| Kinship Status | −0.32 | −0.41 |

| Log FP Mood | 2.88 | 3.09 |

| Group Engagement × Child Age | 0.36 | |

| Group Engagement × Child Sex (male) | 1.08 | |

| Group Engagement × Prior Placements | −0.74* | |

| Group Engagement × FP African American | −4.53 | |

| Group Engagement × FP Hispanic | −3.35 | |

| Group Engagement × FP Age | 0.02 | |

| Group Engagement × Ethnic Match Child | 1.04 | |

| Group Engagement × Ethnic Match Leader | 2.12 | |

| Group Engagement × FP Kinship | −2.95 | |

| Group Engagement × FP Mood | −1.11 | |

| Incremental Change in Proportion of Variance Explained | .47 | .36 |

Note: FP = foster parent; PDR = Parent Daily Report

p <.001

p <.05

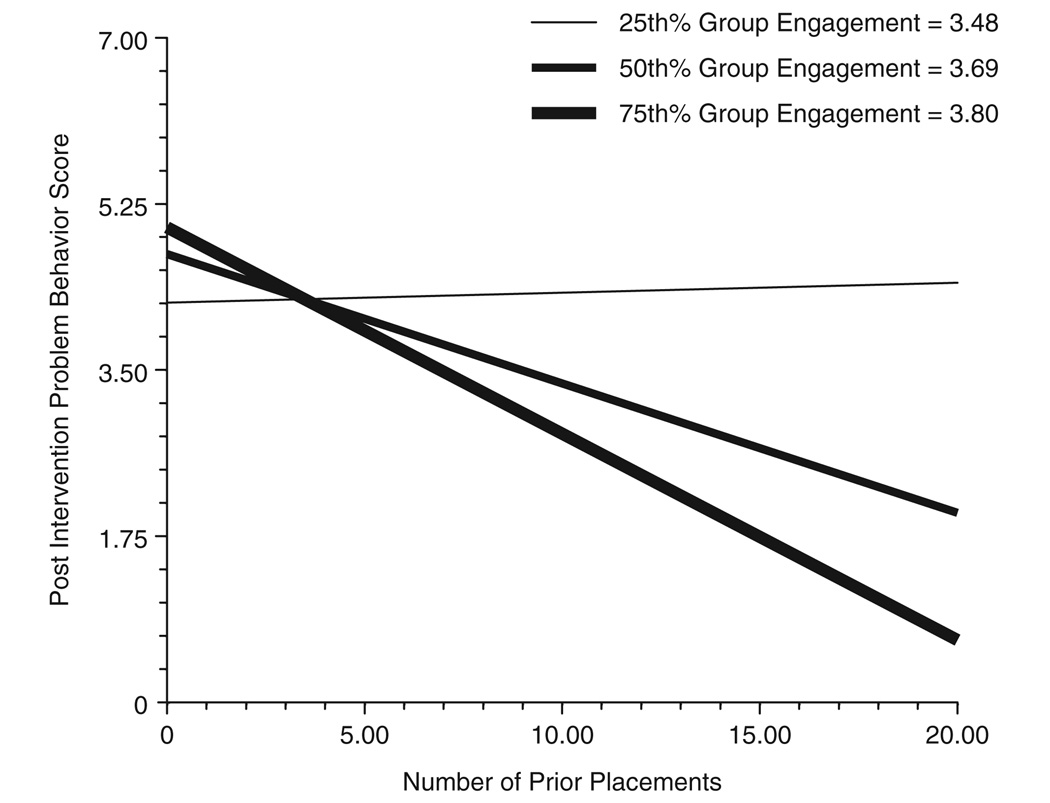

To illustrate the effect of group engagement on prior placement history, the family level slopes for the effect of prior placements on post intervention outcomes are plotted in Figure 1 by the 25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles of group engagement at Level 2 for the PDR outcome. Slopes for the lower percentiles of group engagement were significantly more positive and slopes for the higher percentiles of group engagement were significantly more negative. Therefore, higher engagement of group members buffered the effect of prior placement risk, whereas lower levels of group process did not serve to buffer risk. For caregivers who were more engaged in group activities of the intervention, benefit of the intervention was greater for children at higher risk due to higher numbers of prior placements.

Figure 1.

Moderating Effect of Group Engagement on Prior Placements Predicting Change in Daily Reported Behavior Problems from Baseline to Post Intervention Follow-up

Probability of a Negative Placement Disruption

Results for the multilevel logit model are presented in Table 4 in the form of odds ratios for the probability of a negative placement exit from the home. There are no negative values estimated for interpreting odds ratio coefficients. Odds ratios in both Model 1 and Model 2 that are greater than one are interpreted as increased risk. Odds ratios that are fractions less than one represent reductions in risk.

Table 4.

Multilevel Logit Model for Probability of Negative Placement Disruption (n = 337 Families, n = 59 Groups)

| Negative Placement Odds Ratio |

||

|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |

| Foster Child Age | 0.93 | 0.95 |

| Foster Child Sex (male) | 1.02 | 0.92 |

| Number of Prior Placements | 0.99 | 1.01 |

| Foster Parent- African American | 2.25 | 2.24 |

| Foster Parent- Hispanic | 1.53 | 0.96 |

| Foster Parent Age | 0.99 | 0.52 |

| Ethnic Match Foster Parent-Child | 0.65 | 0.63 |

| Ethnic Match Foster Parent-Group Leader | 0.67 | 0.81 |

| Kinship Status | 0.33** | 0.42** |

| Log FP Mood | 13.75** | 13.95** |

| Group Engagement × Child Age | 0.87 | |

| Group Engagement × Child Sex (male) | 0.23 | |

| Group Engagement × Prior Placements | 1.16 | |

| Group Engagement × FP African American | 0.64 | |

| Group Engagement × FP Hispanic | 0.03* | |

| Group Engagement × FP Age | 0.14 | |

| Group Engagement × Ethnic Match Child | 3.68 | |

| Group Engagement × Ethnic Match Leader | 0.79 | |

| Group Engagement × FP Kinship | 9.06 | |

| Group Engagement × FP Mood | 1.78 | |

| Incremental Change in Proportion of Variance Explained | .05 | .41 |

Note: FP = foster parent

p < .01;

p < .05

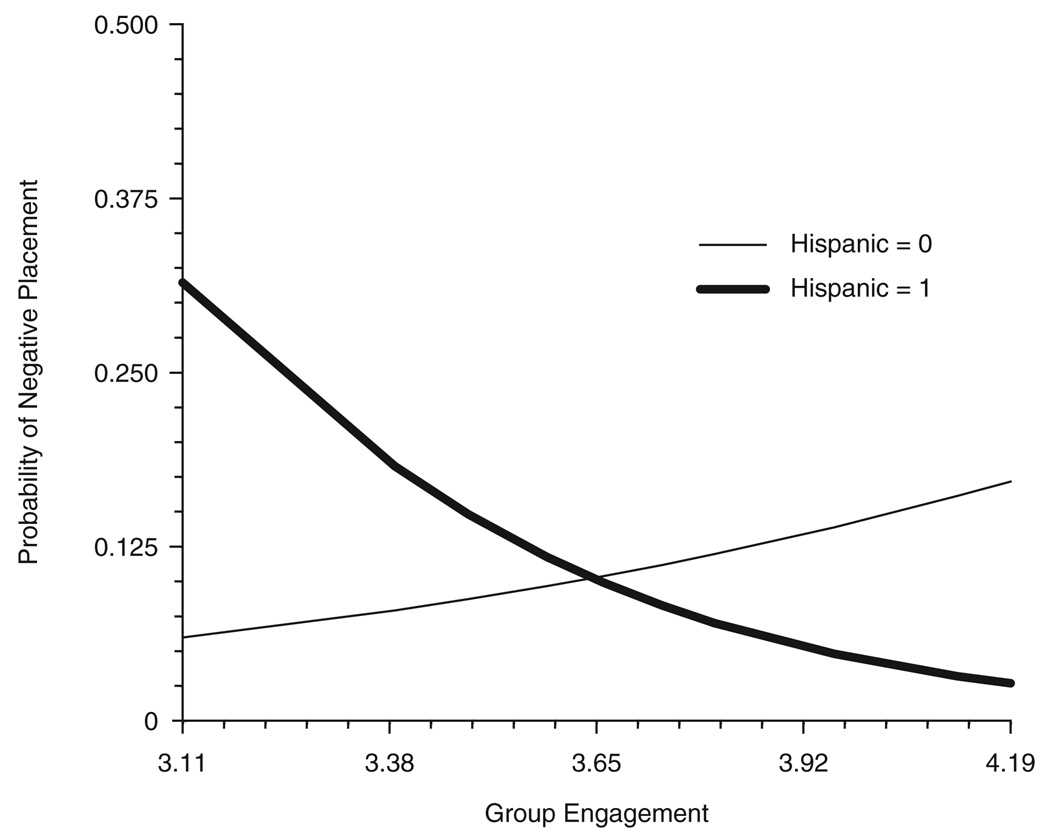

For the family level predictors in the left hand column, kinship caregivers were 67% less likely to experience a negative placement disruption controlling for the other covariates, and caregivers time varying negative mood was associated with over 13 times greater likelihood to have a negative disruption. In Model 2 in the right hand column, for a standard unit increase on the scale of group engagement, Hispanic caregivers were significantly less likely to experience a negative disruption by over 90% compared with caregivers in groups characterized by lower levels of engagement. The estimated beneficial effect of group engagement of Hispanic caregivers is plotted in Figure 2. Thirteen percent of intervention families experienced a negative placement disruption. The interaction effect illustrated in Figure 2 means that in comparing Hispanic families with non-Hispanic families, at average levels of group engagement, both Hispanics and Non-Hispanics were around the average probability of a negative disruption for the entire sample. However, risk was nearly double if Hispanics were at low levels of group engagement but risk was less than half the average if Hispanic foster parents exhibited high group engagement.

Figure 2.

Moderating Effect of Group Engagement in Predicting Reduced Risk of Negative Placement for Hispanic Caregivers

Discussion and Applications to Practice

The present study conducted a within intervention group analysis to examine whether variance across foster parent groups during implementation contributed to intervention outcomes. Our goal was to examine potential variation across foster parent groups during implementation of the intervention. Intent to treat analyses for effectiveness of a given program is the gold standard in demonstrating the utility of implementing an intervention. One assumption for effectiveness in large scale implementations is that programs are uniformly delivered. Such an approach is undertaken for good reason with program designers desiring evidence of effectiveness and generalizability across various implementation settings. However, as some of the present data illustrated, it is possible that participant, group leaders, and group process variables could explain additional variance in effectiveness.

We defined group engagement as group leader ratings of foster parent’s level of participation, openness to the intervention ideas, satisfaction with intervention methods, and completion of homework practice during each group intervention session. We hypothesized that foster parents with higher levels of group engagement would benefit more from the intervention compared with foster parents with lower levels of group engagement. We expected the engagement would moderate known risk factors for foster child outcomes.

The findings suggested that effective group engagement during intervention is a factor associated with implementation success. Although the effects of variation in group engagement were modest across the range of family level characteristics, the present findings demonstrated that the effective engagement of foster and kin caregivers was associated with reducing risk of prior placement histories. Thus, for foster parents of children with a high number of prior placements, greater benefit was obtained when they participated in intervention groups characterized by higher engagement among all members. In fact, this finding is likely contributing to the differential effect previously shown for the main effectiveness evaluation previously published on the KEEP. That is, findings from the KEEP trial have shown that the intervention moderated effects of prior placement history for the intervention families relative to their control group counterparts in the treatment as usual service delivery (Price et al., 2008). Using a within treatment group design, the present study implicated a mechanism accounting for that differential effect was attributable to variation in the level of group engagement by the foster and kin parent caregivers. If replicated, this pattern of findings suggests a key mechanism—positive group engagement—whereby families with the greatest prior risk could show improved outcomes. Additional work focused on experimentally improving group engagement during treatment might yield additional insight into how to help those most in need.

Considering the main effects of risk factors, kinship caregivers were less likely to experience a negative placement disruption but kinship was not related to changes in problem behaviors. In addition, prior studies have noted that kinship caregivers rely more on group support (Berrick, 1998); however, the group engagement score did not moderate effects of kinship status in predicting child outcomes. Perhaps more specified measures of group support would better test this hypothesis.

Main effects of within intervention race–ethnicity contrasts and ethnic-matching were not associated with PDR reports or negative placement disruptions. For Hispanics, group engagement significantly predicted benefit in reducing risk for negative placement disruption. These findings suggest that group engagement and group process indicators are potentially more salient for Hispanic families.

We also caution that interpretation of risk factors for a within groups analysis is not the same as a comparison of intervention group risk and control group counterparts in a randomized control trial. Therefore, another possible explanation pertaining to lack of prediction by family risk factors on the PDR is that a within the intervention group analysis for subjects who were all treated may show relatively smaller variance in differential effectiveness than might be shown for risk factors when comparing treatment families with control group counterparts. In some respects, the more effective a program across wider range of risk factors, the more universal the effectiveness of a given program. Therefore, differential effectiveness can be seen as a double-edged sword showing impact for subsets of participants but at the same time also providing a unique opportunity to capitalize on factors for targeting particular persons or further tailoring interventions to increase effectiveness (Walrath et al., 2006).

The data also suggested that the foster parent mood was a salient parent level risk factor for negative placement disruptions. Some treatment literatures suggest that negativity by leaders and participants interferes with effective group process. In the present findings effective group engagement did not moderate foster parent negative mood. Clinically, there was likely variance across groups in whether leaders attempted to buffer negative interpersonal process or whether it was more effective to reinforce positivity and not attend to negativity. We also note that the negative mood ratings provided significant predictive variance but the distribution of mood across individuals was not indicative of intense levels of negativity on the average and is likely contributing to the large odds ratios.

There were several limitations in the present study. One limitation was that the group leader provided the ratings of group engagement thus leading to potential reporter biases. A more theoretically precise measure would involve objective ratings or observations of the group as the unit of measurement providing indicators of interpersonal and interactional qualities of the group interaction. Multiple perspectives from group participants, leaders, and objective raters would be optimal. At the same time, the data for group level and family level data were from different sources. Regarding method source variance, Shirk and Karver’s (2003) meta analysis of treatment outcomes for adolescents demonstrated a significantly stronger effect of single source predictors and outcomes compared to effects for non-shared sources of data among predictors and outcomes. Although the group data were rated by the leader, a potential advantage of instrumentation in the present study was that groups were characterized by ratings of each participating member which may provide more reliable estimates of variance than would globally rated dimensions of group dynamics (Shirk & Karver, 2003). Another limitation was the absence of measures focusing on implementation fidelity or adherence to the weekly session curricula or specific weekly intervention goals. It is likely that variance in appropriate content coverage and fidelity would add to treatment outcome variance within the intervention group. Fidelity measures are being developed for future replications to also test the unique independent effects of fidelity and effective group process outcomes. Nonetheless, the present findings have implications for practice in that they underscore the importance of the context of the individual group setting. The tone of the group and the leader’s skill at engaging foster parents in positive group process much like adherence to the intervention curriculum appears to be a salient factor in determining positive child behavioral outcomes and buffering placement disruptions, especially in non-relative foster homes caring for high-risk children.

This implies that when implementing interventions with foster parents, training and supervising clinical personnel to use effective engagement strategies is an important focus in its own right. Related is the finding that parent negative mood was predictive of increased risk for placement disruption. The sources of negative mood were not examined in this study and could have been child related (e.g., difficult to manage, bad fit in the home) or not (life event or stress driven). If the goal of the intervention is to provide meaningful skills and support to foster parents so that they are equipped to effectively parent the children in their care, the findings here imply that future work on promoting positive engagement and identifying and buffering sources of parental stress would be productive avenues for increasing positive outcomes for foster children, foster parents, and the child welfare system in general.

Acknowledgments

Support for this research was provided by Grant Nos. R01 MH 60195 from the Child and Adolescent Treatment and Preventive Intervention Research Branch, DSIR, NIMH, U.S. PHS; R01 DA 15208, and R01 DA 021272 from the Prevention Research Branch, NIDA, U.S., PHS; R01 MH 054257 from the Early Intervention and Epidemiology Branch, NIMH, U.S. PHS; and P20 DA 17592 from the Division of Epidemiology, Services and Prevention Branch NIDA, U.S., PHS. The authors wish to thank Yvonne Campbell and Patty Rahiser from the San Diego Health and Human Services Agency, and Jan Price and Courtenay Padgett, project coordinators.

Contributor Information

David S. DeGarmo, Oregon Social Learning Center

Patricia Chamberlain, Oregon Social Learning Center.

Leslie D. Leve, Oregon Social Learning Center

Joe Price, Child and Adolescent Services Research Center, San Diego, CA.

References

- Allen JP, Philliber S. Who benefits most from a broadly targeted prevention program? Differential efficacy across populations in the teen outreach program. Journal of Community Psychology. 2001;29:637–655. doi: 10.1002/jcop.1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger LM, McDaniel M, Paxson C. Assessing parenting behaviors across racial groups: Implications for the child welfare system. The Social Service Review. 2005;79:653–751. [Google Scholar]

- Berrick JD. When children cannot remain home: Foster family care and kinship care. The Future of Children. 1998;8:72–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain P, Price J, Leve LD, Laurent H, Landsverk JA, Reid JB. Prevention of behavior problems for children in foster care: Outcomes and mediation effects. Prevention Science. 2008;9:17–27. doi: 10.1007/s11121-007-0080-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain P, Price JM, Reid JB, Landsverk J, Fisher PA, Stoolmiller M. Who disrupts from placement in foster and kinship care? Child Abuse & Neglect. 2006;30:409–424. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain P, Reid JB. Parent observation and report of child symptoms. Behavioral Assessment. 1987;9:97–109. [Google Scholar]

- Clark HB, Lee B, Prange ME, Stewart ES, McDonald BB, Boyd LA. An individualized wraparound process for children in foster care with emotional/behavioral disturbances: Findings and implications from a controlled study. In: Epstein M, Kutash K, Duchnowski A, editors. Outcomes for children and youth with emotional and behavioral disorders and their families: Programs and evaluation best practices. Dallas, TX: PRO-ED; 1998. pp. 513–542. [Google Scholar]

- Dozier M, Peloso E, Linidheim O, Gordon MK, Manni M, Sepulveda S, et al. Developing evidence-based interventions for foster children: An example of a randomized clinical trial with infants and toddlers. Journal of Social Issues. 2006;62:7676–7785. [Google Scholar]

- Eddy JM, Chamberlain P. Family management and deviant peer association as mediators of the impact of treatment condition on youth antisocial behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:857–863. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.68.5.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glisson C. Assessing and changing organizational culture and climate for effective services. Research on Social Work Practice. 2007;17:736–747. [Google Scholar]

- Hall GCN. Psychotherapy research with ethnic minorities:Empirical, ethical, and conceptual issues. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69:502–510. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.3.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoagwood K, Burns BJ, Kiser L, Ringeisen H, Schoenwald SK. Evidence-based practice in child and adolescent mental health services. Psychiatric Services. 2001;52:1179–1189. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.9.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogue A, Liddle HA, Singer A, Leckrone J. Inervention fidelity in family-based prevention counseling for adolescent problem behaviors. Journal of Community Psychology. 2006;33:191–211. [Google Scholar]

- Holden EW, Connor T, Brannan AM, Foster EM, Blau G. Evaluation of the Connecticut Title IV-E Waiver Program: Assessing the effectiveness, implementation fidelity, and cost/ benefits of a continuum of care. Children and Youth Services Review. 2002;24:409–430. [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, Wassell G. Barriers to treatment participation and therapeutic change among children referred for conduct disorder. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1999;28:160–172. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2802_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leve LD, Fisher PA, DeGarmo DS. Peer relations at school entry: Sex differences in the outcomes of foster care. Merrill Palmer Quarterly. 2007;53(4):557–577. doi: 10.1353/mpq.2008.0003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClowry SG, Snow DL, Tamis-LeMonda CS. An evaluation of the effects of INSIGHTS on the behavior of inner city primary school children. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2005;26:567–584. doi: 10.1007/s10935-005-0015-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillan JH. Randomized field trials and internal validity: Not so fast my friend. Practical Assessment Research & Evaluation. 2007;12 Available online http://pareonline.net/getvn.asp?v=12&n=15.

- Newton RR, Litrownik AJ, Landsverk JA. Children and youth in foster care: Disentangling the relationship between problem behaviors and number of placements. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2000;24:1363–1374. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(00)00189-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oie TPS, Browne A. Components of group processes: Have they contributed to the outcome of mood and anxiety disorder patients in a group cognitive-behavior therapy program? American Journal of Psychotherapy. 2006;60:53–70. doi: 10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.2006.60.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price JM, Chamberlain P, Landsverk J, Reid J, Leve L, Laurent H. Effects of a foster parent training intervention on placement changes of children in foster care. Child Maltreatment. 2008;13:64–75. doi: 10.1177/1077559507310612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. Vol. 1. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Reid JB, Eddy JM. Can we prevent violence, and can we afford not to? In: Rubin EL, editor. Minimizing harm as a goal for crime policy in California: A policy research program report. Berkeley, CA: University of California; 1997. pp. 47–51. [Google Scholar]

- Roback HB. Adverse outcomes in group psychotherapy: Risk factors, prevention, and research directions. Journal of Psychotherapy Practice and Research. 2000;9:113–122. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenwald SK, Halliday-Boykins CA, Henggeler SW. Client-level predictors of adherence to MST in community service settings. Family Process. 2003;42:345–359. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2003.00345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirk SR, Karver M. Prediction of treatment outcome from relationship variables in child and adolescent therapy: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:452–464. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.3.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone AA, Broderick JE, Kaell AT, DelesPaul PAEG, Porter LE. Does the peak-end phenomenon observed in laboratory pain studies apply to real-world pain in rheumatoid arthritics? Journal of Pain. 2000;1:212–217. doi: 10.1054/jpai.2000.7568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sue S, Fujino DC, Hu L-t, Takeuchi DT. Community mental health services for ethnic minority groups: A test of the cultural responsiveness hypothesis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;59:533–540. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.4.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walrath CM, Ybarra ML, Holden EW. Understanding the pre-referral factors associated with differential 6-month outcomes among children receiving system-of-care services. Psychological Services. 2006;3:35–50. [Google Scholar]

- Weinrott MR, Bauske B, Patterson GR. Systematic replication of a social learning approach. In: Sjöden PO, Bates S, Dockens WS III, editors. Trends in behavior therapy. New York: Academic Press; 1979. pp. 331–352. [Google Scholar]

- Zambrana RE, Capello D. Promoting Latino child and family welfare: Strategies for strengthening the child welfare system. Children and Youth Services Review. 2003;25:755–780. [Google Scholar]