Abstract

Progression through the cell cycle is regulated in part by the sequential activation and inactivation of cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs). Many signals arrest the cell cycle through inhibition of CDKs by CDK inhibitors (CKIs). p27Kip1 (p27) was first identified as a CKI that binds and inhibits cyclin A/CDK2 and cyclin E/CDK2 complexes in G1. Here we report that p27 has an additional property, the ability to induce a proteolytic activity that cleaves cyclin A, yielding a truncated cyclin A lacking the mitotic destruction box. Other CKIs (p15Ink4b, p16Ink4a, p21Cip1, and p57Kip2) do not induce cleavage of cyclin A; other cyclins (cyclin B, D1, and E) are not cleaved by the p27-induced protease activity. The C-terminal half of p27, which is dispensable for its kinase inhibitory activity, is required to induce cleavage. Mechanistically, p27 does not appear to cause cleavage through direct interaction with cyclin/CDK complexes. Instead, it activates a latent protease that, once activated, does not require the continuing presence of p27. Mutation of cyclin A at R70 or R71, residues at or very close to the cleavage site, blocks cleavage. Noncleavable mutants are still recognized by the anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome pathway responsible for ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis of mitotic cyclins, indicating that the p27-induced cleavage of cyclin A is part of a separate pathway. We refer to this protease as Tsap (pTwenty-seven- activated protease).

Keywords: proteolysis, cell cycle

In human somatic cells, entry into mitosis requires activation of cyclin-dependent kinase 1 (CDK1; p34cdc2) by cyclin A and cyclin B, whereas progression from G1 into S phase requires activation of other CDKs by cyclins D, E, and A (1, 2). The kinase activities of cyclin/CDK complexes can be regulated by stage-specific proteolytic destruction of the cyclin subunit, phosphorylations of the CDK subunit, and binding by inhibitors called cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors (CKIs, reviewed in refs. 3–7). Signals that arrest the cell cycle often do so by inducing accumulation of CKIs (3, 4). Two CKI families have been identified. Ink family members (p16Ink4a, p15Ink4b, p18Ink4c, and p19Ink4d) selectively inhibit the G1 kinases CDK4 and CDK6. The Kip/Cip family of CKIs (p21Cip1, p27Kip1, and p57Kip2) inhibits a broader range of cyclin/CDK complexes. Members of the Kip/Cip family share a highly conserved N-terminal region, which contains a cyclin-binding region and a CDK-binding region, both of which contribute to inhibition of cyclin/CDK activity. The sequences of their C-terminal domains, by contrast, are very divergent and are believed to largely responsible for the specificity of the individual family members (3, 4, 8, 9).

p21Cip1 (p21) is up-regulated in a wide variety of settings. Signals that result in DNA damage activate the p53-dependent transcription and accumulation of p21, which associates with cyclin/CDK complexes and contributes to arresting DNA-damaged cells in G1 (10–13). Increases in p21 levels also occur as cells approach senescence, and as cells exit the cell cycle during terminal differentiation (14–18). p21−/− mice develop normally, indicating that p21 is not required uniquely for normal cell cycle functions during mouse development. Fibroblasts from these animals fail to arrest after DNA damage, however, indicating an essential role in at least one checkpoint control pathway regulating cell division (19, 20). Ectopic expression of p21 often results in cell cycle arrest, mainly in the G1 phase of the cycle (11). p21 contains two functionally distinct domains: an N-terminal domain that binds and inhibits cyclin/CDK complexes, and a C-terminal region that binds and inhibits proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA), a component of DNA polymerase. When expressed individually, each domain can independently arrest the cells in G1 (3, 4, 9).

p57Kip2 (p57) is able to bind to and inhibit the activities of cdk2, cdk3, and cdk4, and overexpression of p57 leads to a G1 arrest (21, 22). p57 is expressed at high levels in many differentiating cells and adult tissues, and loss of p57 correlates with defects in both proliferation and differentiation in a subset of cells that normally express p57 (23, 24). The C-terminal domain of p57, while largely divergent in sequence from that of p21, contains a short region that resembles the 20-residue PCNA-binding domain of p21 and can mediate binding to PCNA in vitro (25). Like p21, the C-terminal domain of p57 can inhibit PCNA-dependent DNA synthesis in vitro and block the onset of S phase in vivo (25). Thus, both p21 and p57 contain separate cyclin/CDK- and PCNA-binding domains, each of which can independently arrest the cell cycle.

By contrast with the two activities known for p21 and p57, only one activity has been established so far for p27Kip1 (p27): the ability of its highly conserved N-terminal domain to bind and inhibit cyclin/CDK complexes (3, 4, 9). The function of p27’s distinctive C-terminal domain is unknown. p27 was identified initially as a CDK inhibitory protein induced by a variety of antiproliferative signals (including contact inhibition, growth factor withdrawal, and exposure to transforming growth factor β, rapamycin, or lovastatin) that resulted in cells arresting in either G0 or G1 of the cell cycle (26–32). In vivo, p27 can inhibit the kinase activities of a variety of cyclin/CDK complexes, including those containing CDK1, -2, -4, or -6, and cyclins A, E, or D. Its N-terminal domain is sufficient to block cyclin/CDK kinase activity, both in vitro and in vivo, and to arrest cell cycle progression (29, 33). In normal cells, p27 protein levels increase as cells become quiescent and rapidly decrease (but do not disappear) when cells are stimulated to reenter the cell cycle (34–36). Overexpression of p27 arrests cells mainly in G1 (28, 29). While p27−/− mice are viable, most organs are larger than normal, apparently the result of undergoing additional rounds of cell division prior to terminal differentiation, and these mice show a greatly increased risk of tumor formation in certain tissues (37–39). In humans, loss of p27 is also associated with an increased susceptibility to tumorigenesis (e.g., refs. 40–42).

Here we show that p27 possesses a second property, the ability to induce a proteolytic activity that cleaves within the N-terminal domain of cyclin A. This cleavage removes the mitotic destruction box, yielding a truncated cyclin A that evades degradation by the mitotic destruction machinery. Only p27, and not other CKIs tested, induces this protease activity; among the cyclins tested, only cyclin A is a target of this activity. Mechanistic studies reveal that p27 does not appear to induce cleavage through its direct interaction with cyclin A/CDK. Instead, p27 initiates activation of a latent protease, which then acts on cyclin A. The C-terminal domain of p27, which is dispensable for its ability to bind and inhibit cyclin/CDK activity, is essential for the ability of p27 to induce cleavage of cyclin A. This work thus reveals the existence of a pathway in which one cell cycle regulator, p27, can induce activation of an unidentified proteolytic pathway that selectively targets another cell cycle regulator, cyclin A, for a discrete proteolytic cleavage.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Culture.

HeLa, 293 (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) and FR3T3 cells (provided by Jean Rommelaere) were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) plus 10% fetal calf serum (GIBCO/BRL). To obtain cells arrested in S phase, cells were incubated in medium containing either 2 mM hydroxyurea (Sigma) or 2 mM thymidine (Sigma) for 18–20 hr. Cells were arrested in mitosis by incubation in DMEM containing 0.3 μM nocodazole (Sigma) for 16–18 hr. FR3T3 cells were synchronized in G0 by serum starvation for 48–72 hr before adding 10% fetal calf serum to induce reentry into the cell cycle. At 2-hr intervals the cells were pulse-labeled with 100 μM bromodeoxyuridine (Sigma) for 25 min, fixed, and stained; cells containing incorporated label were counted (43). Remaining cells were used for immunoblotting. 293 cells were transfected by using Superfect Reagent (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and analyzed by immunoblotting 48 hr after transfection.

Plasmids.

All cDNAs encoded human proteins unless otherwise noted. Plasmids encoding the cyclin A D-box mutant or the cyclin A construct tagged with an AU1 epitope at the N terminus and a hemagglutinin (HA) epitope at the C terminus were generated by PCR and cloned into pGEM4Z. Cyclin A deletion mutants, which contained a C-terminal AU5 tag, were created by PCR and cloned into pcDNA3. Cyclin A point mutants were created by using oligonucleotide-directed mutagenesis (44) on single-stranded template derived from pcDNA3 encoding full-length cyclin A-AU5. For transfections of 293 cells, cyclin A wild-type or noncleavable mutant cDNAs were cloned into pCS2+. The following colleagues generously provided plasmids: Mark Rolfe (pT7–7-His-p27Kip1), Anindya Dutta (pcDNA3-p27-N, pcDNA3-p27-C), Pradip Raychaudhuri (pcDNA3-mouse p27Kip1-WT, -mC, mK), Gordon Peters (pBuescript-p15Ink4b), Ed Harlow (pCMV-p16Ink4a, pBluescript-p21Cip1, pcDNA3-p57Kip2), William Dunphy (pET9-His-p28Kix1), James Maller (p27Xic1), and Mark Carrington and Deborah Wolgemuth (pBluescript-mouse cyclin A1, A2).

HeLa Cell Extracts.

To prepare extracts from S-phase cells, HeLa cells were grown to 50% confluence, then arrested in S phase by a single hydroxyurea block. Cells were harvested by trypsin/EDTA treatment and washed twice in ice-cold PBS and once in low-salt buffer [50 mM Hepes/NaOH, pH 7.4/5 mM KCl/1.5 mM MgCl2/1 mM DTT plus protease inhibitors (complete protease inhibitor tablets, Boehringer Mannheim)]. Cells were resuspended in 0.5 vol of low-salt buffer and lysed by sonication. Cellular debris was removed by centrifugation at 14,000 × g for 20 min. The supernatant (HeLa-HU) was divided into aliquots, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C. Extracts from mitotic cells (HeLa-Noc) were prepared from cells arrested with nocodazole as described above. For cyclin degradation assays, extracts from HeLa cells synchronized in G1 phase were prepared as described (45).

In Vitro Transcription and Translation.

All reactions were performed using a coupled reticulocyte lysate system (TNT, Promega) in volumes of 20–50 μl. [35S]Methionine (1,175 Ci/mmol; 1 Ci = 37 GBq) was used for labeling in vitro translated proteins.

Cyclin A Cleavage and Degradation Assays.

Equal volumes of HeLa-HU or HeLa-Noc extract and reticulocyte lysate (RL) expressing various CKIs were mixed and incubated at 30°C. At each time point, 3-μl aliquots were transferred into SDS sample buffer and analyzed on SDS/PAGE followed by immunoblotting. If radiolabeled or tagged cyclin A was used, the reaction mixture was supplemented with another volume of 35S-labeled cyclin A RL translation product, and cyclin A was detected by autoradiography or by immunoblotting. Cyclin degradation assays were done as described (45, 46).

Antibodies.

The following antibodies were used in this study: cyclin A (H-432), mouse cyclin A (C-19), cyclin B (H-433), cyclin D1 (R-124), cyclin E (C-19), p27 (F-8 and C-19) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology); AU1 (Babco, Richmond, CA), 12CA5/anti-HA (Boehringer Mannheim). For immunoblot analysis, cell extracts were resolved by electrophoresis on SDS/12.5% or 15% polyacrylamide gels and transferred onto poly(vinylidene difluoride) (PVDF) membranes (Millipore). Blocking of the membrane and incubations with antibodies were performed in Tris-buffered saline containing 5% or 2% nonfat dry milk, respectively. Immunoblots were developed by using enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL; Amersham).

To immunodeplete p27Kip1 from RL, 90-μl samples were precleared by incubation with 8 μl of staphylococcal protein A-Sepharose (Pharmacia) for 1 hr at 4°C. The supernatant was incubated with 5 μl of antibody solution [either αp27Kip1 (C-19) or a control antibody] and 8 μl of protein A-Sepharose for 2 hr at 4°C. This procedure was repeated three times. The final supernatant did not contain any detectable p27Kip1.

For immunoprecipitations, 60 μl of HeLa-HU extract was coincubated with RL immunodepleted of p27Kip1, RL expressing p27Kip1 immunodepleted of p27Kip1, or RL expressing p27Kip1 that had been mock-depleted. Samples (3 μl) were analyzed by SDS/PAGE followed by blotting with cyclin A antibodies.

For kinase assays from HeLa-HU extracts, 35-μl samples were diluted in Nonidet P-40 buffer (20 mM Hepes/NaOH, pH 7.4/10 mM EDTA/175 mM NaCl/0.7% Nonidet P-40 plus complete protease inhibitors) to a final volume of 185 μl. After centrifugation for 20 min at 14,000 × g, the supernatant was precleared with 10 μl of protein A-Sepharose for 45 min at 4°C and then incubated with 7 μl of cyclin A antibodies (100 μg/ml) for 90 min at 4°C followed by the addition of 10 μl of protein A-Sepharose for an additional 90 min. Immunocomplexes were harvested by centrifugation, washed five times in Nonidet P-40 buffer and once in kinase buffer (20 mM Hepes/NaOH, pH 7.4/10 mM MgCl2/1 mM DTT), and resuspended in 20 μl of kinase buffer plus 0.2 mM ATP, 7.5 μg of histone H1 (Sigma), 10 μM protein kinase C inhibitor, and 0.5 μl of [γ-32P]ATP (6,000 Ci/mmol). The mixture was incubated for 20 min at 37°C and the reaction was stopped by addition of 30 μl of SDS sample buffer. Samples (10 μl) were analyzed by SDS/PAGE followed by autoradiography.

RESULTS

p27 Induces Cleavage of Cyclin A.

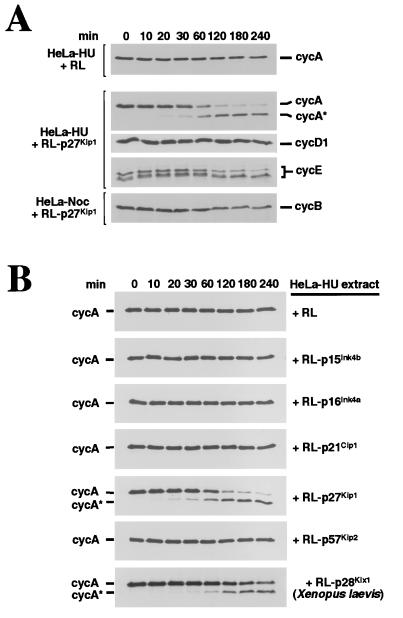

Our attention was first drawn to the ability of p27 to induce cleavage of cyclin A while we were using in vitro systems to study the degradation of various cyclins and CKIs during the cell cycle. We incubated an extract of HeLa cells arrested in S phase by hydroxyurea (HeLa-HU) with rabbit RL containing in vitro translated, radiolabeled p27 (RL-p27), with the initial aim of examining p27 stability. Since the cyclin A present in the HeLa-HU extract was expected to be stable, we monitored cyclin A levels on immunoblots of the same samples as a control. To our surprise, addition of RL-p27 led to the disappearance of full-length cyclin A protein from the HeLa-HU extract and the appearance of a more rapidly migrating band (cycA*, Fig. 1A). As shown below, this conversion appears to be the result of a discrete proteolytic cleavage, and we thus refer to this event as cleavage. Addition of unprogrammed RL did not induce cleavage of cyclin A, indicating that the p27 translation product was responsible for inducing cleavage of cyclin A. The addition of RL-p27 had no detectable effect on the migration of endogenous cyclins D1 or E present in the HeLa-HU extract or cyclin B present in extracts of nocodazole-arrested M-phase cells (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

p27 induces formation of a modified form of cyclin A (cycA*). (A) p27 expression in RL leads to modification of cyclin A but not other human cyclins. Human p27 was transcribed and translated in rabbit RL (RL-p27) and incubated with HeLa-HU extracts (for detection of cyclins A, D1, and E) or HeLa-Noc extracts (for detection of cyclin B). HeLa-HU extract was incubated with unprogrammed RL as a control. Samples were taken at the indicated times and analyzed by SDS/PAGE followed by immunoblotting with antibodies against human cyclins A, D1, E, and B. (B) The ability to induce formation of cycA* is specific to p27. HeLa-HU extracts were incubated with RL in which the indicated human (RL-p15Ink4b, RL-p16Ink4a, RL-p21Cip1, or RL-p57Kip2) or Xenopus (RL-p28Kix1) CKIs had been translated. Samples were taken at the indicated times and analyzed by SDS/PAGE followed by blotting with cyclin A antibodies.

In the same assay, neither Ink family CKIs (p15Ink4b, p16Ink4a) nor other members of the Kip/Cip family (p21Cip1, p57Kip2) induced detectable cleavage of cyclin A (Fig. 1B). Only the related Xenopus CKIs p28Kix1 (Fig. 1B) and p27Xic1 (not shown), which share sequence homology with both p21Cip1 and p27 (47, 48) led to cleavage. Thus, the ability to induce cleavage of cyclin A seems limited to p27-related CKIs and, of the cyclins tested, only cyclin A is cleaved in response to p27.

p27 Induces Cleavage Within the N Terminus to Generate a Truncated Cyclin A Lacking the Mitotic Destruction Box.

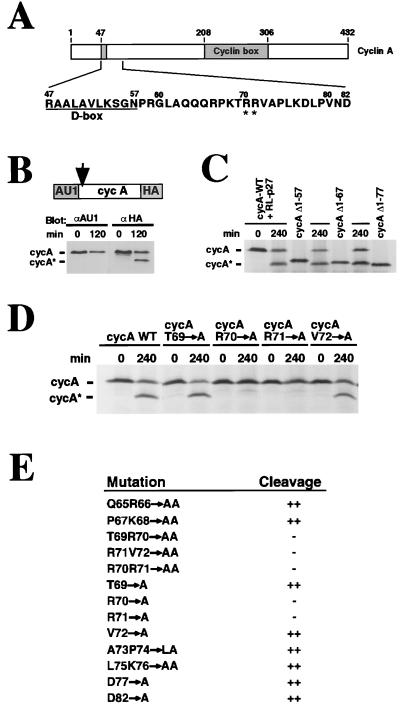

The N-terminal half of cyclin A contains a short destruction box (D-box) sequence similar to the one required for the ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis of B-type cyclins during mitosis (49, 50); see Fig. 2A). The C-terminal cyclin box domain is necessary for CDK binding and activation (reviewed in ref. 51). To determine from which end sequences were removed, we created a construct encoding cyclin A bearing both an N-terminal AU1 and a C-terminal HA tag, and asked which tag was removed by using the following assay. The tagged cyclin A was produced by in vitro translation, mixed with HeLa-HU extract (in which cyclin A is stable), and then incubated with RL-p27 to induce cleavage. Immunoblots using AU1 or HA antibodies revealed that p27 induces removal of the N-terminal AU1 tag and thus cleaved within the N terminus (Fig. 2B). Using a set of cyclin A deletion mutants (Δ1–57, Δ1–67, and Δ1–77) as size markers, we estimated that cycA* lacks between 68 and 76 N-terminal residues (Fig. 2C). Thus, p27-induced cleavage of cyclin A occurs downstream of the D box and results in the formation of a truncated cyclin A lacking the D box.

Figure 2.

Proteolytic cleavage yields an N-terminally truncated form of cyclin A lacking the mitotic destruction box (D box). (A) Diagram of cyclin A. The location of the D box and cyclin box are shown; the predicted site of p27-induced cleavage is indicated by asterisks. (B) p27 induces removal of N-terminal sequences from cyclin A. In vitro translated cyclin A protein bearing an N-terminal AU1 and a C-terminal HA tag was incubated with HeLa-HU extracts and RL-p27 to induce cleavage. Samples were taken at 0 and 120 min and were analyzed by SDS/PAGE followed by immunoblotting using antibodies against the AU1 or HA tag, as indicated. (C) Cyclin A is cleaved between amino acid residues 67 and 77. Radiolabeled cyclin A translation product was incubated for 240 min with RL-p27 to induce cleavage, as in B. A set of N-terminal deletion mutants of cyclin A (Δ1–57, Δ1–67, Δ1–77) was generated by PCR and translated in vitro to yield a set of radiolabeled cyclin A size markers. Samples were analyzed by SDS/PAGE followed by autoradiography. (D) R70 and R71 are essential for cleavage of cyclin A. Radiolabeled translation products of the indicated point mutants were mixed with HeLa-HU extracts and RL-p27 and incubated for 240 min. Samples were analyzed as in C. (E) Complete set of cyclin A point mutants tested for p27-induced cleavage. Mutants were tested as in D.

To determine which residues are essential for cleavage, individual residues, or pairs of residues, across the region 65–77 were changed to alanines, the mutant cyclins were produced by in vitro translation, and their abilities to respond to p27 were tested by the assay just described. Substitution of alanine for either R70 or R71 completely blocked the appearance of cycA*, whereas mutations at other residues did not (Fig. 2 D and E). Two A-type mouse cyclins were also tested. Mouse cyclin A2, which contains the sequence TRRV found at the presumptive cleavage site in human cyclin A, was cleaved; mouse cyclin A1, which lacks this sequence, was not (data not shown). It is most likely that the production of cycA* is due to a discrete cleavage event and that this cleavage occurs at or near R70 or R71, since (i) cycA* is estimated to lack between 68 and 76 residues, (ii) only cycA*, and not a range of larger fragments, is detected, and (iii) only alanine substitutions at R70 or R71 blocked formation of cycA*.

Recently, a small number of cell cycle regulatory proteins have been found to be cleaved by caspases during apoptosis (52–54). In Xenopus embryos undergoing experimentally induced apoptosis, cyclin A is cleaved downstream of the D box by a type 3 caspase activity, generating a truncated cyclin A lacking the D box (55). Caspases cleave after selected aspartic acid residues, and in cyclin A there are only two aspartic acid residues (D77 and D82) in the general vicinity of the cleavage site. Although the fragments produced by cleavage at either of these residues would be expected to migrate more rapidly than cycA*, it was important to test whether either could represent the cleavage site. Thus, we converted D77 and D82 to alanines and tested the ability of the mutants to be cleaved in response to p27. These mutations failed to block cleavage (Fig. 2E). Furthermore, none of the caspase inhibitors tested (N-ethylmaleimide and the aldehyde tetrapeptides YVAD-CHO and DEVD-CHO) blocked p27-induced cleavage (not shown). These results argue strongly against cleavage by a caspase.

NF-κB provides a well-studied example of a protein that is cleaved at a discrete location by the proteasome (56), and purified 26S proteasomes can cleave purified recombinant cyclin B protein at a specific lysine residue just downstream of the D box (57). Thus, it was important to test whether p27-induced cleavage of cyclin A was blocked by proteasome inhibitors. None of the inhibitors tested (ALLN, MG132, lactacysteine) inhibited cleavage, nor did ATP depletion (not shown), arguing against proteasome-mediated cleavage. Similarly, inhibitors of serine proteases (phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, aprotinin), cysteine proteases (E-64, leupeptin), metalloproteases (bestatin, EDTA), aspartic proteases (pepstatin), or caspases (see above) failed to block p27-induced cleavage. The identity of the protease responsible for cyclin A cleavage is currently unknown.

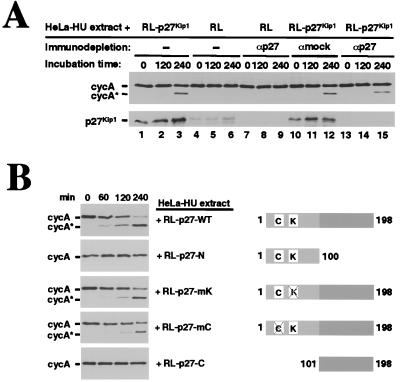

p27 Induces Activation of a Latent Protease in RL.

Mechanistically, we can envision four models whereby p27 leads to cleavage of cyclin A. (i) p27 is a protease itself. (ii) p27 acts as an adaptor for a protease. (iii) p27 induces a conformational change in cyclin A, making it available to a constitutively active protease. (iv) p27 induces activation of a protease. Results of the experiment shown in Fig. 3A rule out the first three possibilities. p27 was translated in vitro to generate RL that contained both p27 and the cleaving activity. p27 was then removed from this lysate by immunodepletion, and the p27-depleted supernatant was tested for its ability to induce cleavage of cyclin A in the HeLa-HU extract. As seen earlier, unprogrammed RL, which contains trace levels of p27, did not induce cleavage (Fig. 3A, lanes 4, 5, and 6), whereas RL-p27, which contains high levels of p27, did (lanes 1, 2, and 3). Importantly, RL-p27 from which all detectable p27 was subsequently removed by immunodepletion retained the same level of cleaving activity (lanes 13, 14, and 15) as mock-depleted RL-p27 (lanes 10, 11, and 12). These results exclude mechanisms that depend on p27 binding to cyclin A or on its providing the associated protease activity. Instead, they establish that p27 initiates activation of a protease and that, once activated, the protease does not require the continuing presence of p27 for its ability to cleave cyclin A.

Figure 3.

p27 induction of the cyclin A-cleaving activity. (A) p27 activates a protease that, once activated, no longer requires the presence of p27. p27 was translated in RL (RL-p27) and p27 was subsequently removed by immunodepletion. Immuno- or mock-depleted RL-p27 was incubated with HeLa-HU extracts for the indicated times, and generation of cycA* was monitored by immunoblotting. As controls, HeLa-HU extracts were incubated with nondepleted RL-p27 or nondepleted or immunodepleted unprogrammed RL as indicated (Upper). The efficiency of p27 immunodepletions from RL and from RL-p27 was examined by immunoblotting with p27 antibodies (Lower). (B) The N-terminal domain of p27, which contains its kinase inhibitory activity, is required but not sufficient to induce cleavage of cyclin A. Various deletion or point mutants of p27 (shown schematically on the right) were translated in reticulocyte lysate and incubated with HeLa-HU extracts. Samples were analyzed by SDS/PAGE followed by immunoblotting using cyclin A antibodies.

p27’s Ability to Induce Cleavage of Cyclin A Is Independent of Its Kinase-Inhibitory Function and Requires Its Distinctive C-Terminal Domain.

How does p27 induce activation of this protease? One possibility is that p27 works through its conventional role as a kinase inhibitor—i.e., it inhibits a kinase that inhibits the protease. We thus asked whether p27’s kinase-inhibitory domain alone could induce cleavage. The N-terminal half (residues 1–100), which is fully capable of binding and inhibiting cyclin/CDK complexes (58), failed to induce cleavage (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, mutations in either the cyclin-binding (R30–F33) or CDK-binding (W60–F64) domains, each of which prevent p27 from acting as a kinase inhibitor (59, 60), did not interfere with the appearance of cleaving activity. However, the C-terminal half by itself did not induce cleavage activity (Fig. 3B). This inability could be due to a failure of the truncated p27 to fold properly, a need for additional N-terminal residues, or for a requirement for the entire p27 molecule. Thus, p27’s ability to induce cleavage of cyclin A is independent of its kinase inhibitory function and requires its distinctive C-terminal half.

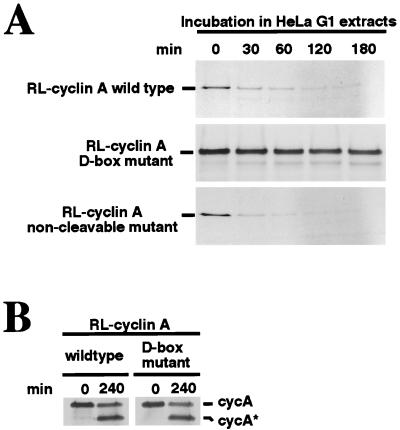

p27-Induced Cleavage and D-Box-Dependent Degradation of Cyclin A Occur Independently.

Mitotic cyclins A and B are degraded during mitosis by ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis. This selective ubiquitination is catalyzed by the anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C) and depends on the presence of a D box in the cyclin target (5, 6, 45, 49, 61–63). In somatic cells, degradation of B-type cyclins continues through G1 phase; removal of the D box or mutations within it result in a nondegradable cyclin B that prevents CDK1 inactivation and exit from mitosis (45, 64). While not as well studied as cyclin B, the destruction of cyclin A during mitosis also appears to depend on the D box (50, 65). We thus investigated a possible relationship between D-box-dependent, APC/C-mediated destruction of cyclin A and p27-induced cleavage of cyclin A. To address this point, we used a cell-free system prepared from HeLa cells that had been arrested in M phase by nocodazole treatment (where cyclin destruction is inhibited), washed free of nocodazole to allow resumption of progression through mitosis and activation of the APC/C pathway, and collected in early G1 (where the APC/C pathway remains active) (45). Radiolabeled cyclin A was produced by in vitro translation and tested to its stability in the G1 extracts. As previously demonstrated for cyclin B (45), cyclin A was rapidly degraded in the G1 extract (Fig. 4A, Top) and its disappearance was completely blocked by point mutations within the D box (Middle). Thus, just as for cyclin B, the destruction of cyclin A continues during G1 and this destruction is D box dependent. By contrast with the D-box mutant, a noncleavable mutant of cyclin A was degraded as efficiently as wild-type cyclin A (Lower). These results argue that the sequences required for cyclin A’s ability to be cleaved in response to p27 are not required for D-box-dependent degradation of cyclin A.

Figure 4.

p27-induced cleavage of cyclin A and D-box-dependent degradation of cyclin A occur independently. (A) Cleavage of cyclin A is not a prerequisite for its degradation in human G1-phase extracts. Radiolabeled wild-type cyclin A, D-box mutant (R47L50 → AA), or noncleavable mutant (T69R70 → AA) were produced by in vitro translation and incubated with HeLa G1 cell extracts for the indicated times. Degradation of translation products was monitored by SDS/PAGE followed by autoradiography. (B) p27-induced cleavage of cyclin A is not dependent on a functional destruction box. Radiolabeled, in vitro translated wild-type cyclin A or D-box mutant proteins were incubated with HeLa-HU extract and RL-p27. Samples were analyzed as in A.

We next asked whether an intact D box is required for the ability of cyclin A to be cleaved in response to p27. Radiolabeled cyclin A proteins were prepared by in vitro translation and then mixed with HeLa-HU extracts (where cyclin A is stable) plus RL-p27 (to provide the cleaving activity). As shown in Fig. 4B, wild-type and D-box-mutated cyclin A were cleaved with equal efficiency. Taken together with the data in Fig. 4A, these results establish that p27-inducible cleavage and D-box-dependent destruction of cyclin A can proceed independently.

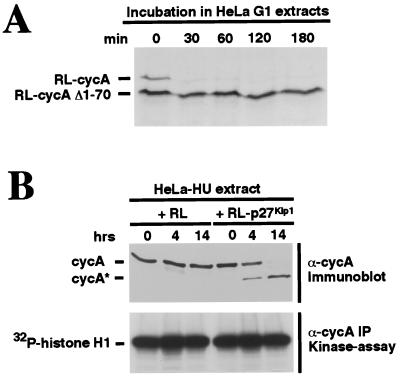

Cleaved Cyclin A Is Stable and Remains Part of an Active CDK Complex.

Since destruction of cyclin A during mitosis (50) and G1 (Fig. 4A) requires the D box, and p27-induced cleavage removes the D box, it was expected that the cleaved form of cyclin A would be resistant to APC/C-mediated degradation. To test this expectation, translation products of constructs encoding full-length cyclin A, or a cyclin A that had been truncated at or near the p27-induced cleavage site (cycA Δ1–70), were incubated with HeLa G1 extract, and the stabilities of the two cyclins were monitored. As predicted, cycA Δ1–70 was stable, while full-length cyclin A was rapidly degraded (Fig. 5A).

Figure 5.

Cleaved cyclin A is stable and remains part of an active CDK complex. (A) Cleaved cyclin A is stabilized in G1 cell extracts. Radiolabeled, in vitro translated full-length (RL-cycA) and a truncated cyclin A protein corresponding to cycA* (RL-cycA Δ1–70) were prepared and incubated with HeLa G1 cell extracts as in Fig. 4A. Degradation of translation products was monitored by SDS/PAGE followed by autoradiography. (B) Cleaved cyclin A remains part of an active CDK complex. HeLa-HU extracts were coincubated with RL-p27 that had been immunodepleted of p27 for the indicated times. Cleavage of endogenous cyclin A was monitored by immunoblotting (Upper). At each indicated time point samples were taken and cyclin A-containing CDK complexes were recovered by immunoprecipitation; subsequent kinase assays used histone H1 as a substrate (Lower).

p27-induced cleavage of cyclin A does not remove any regions known to be required for binding and activating CDK2 (50, 66). Thus, it might be expected that cleavage does not interfere with the kinase activity of these complexes. To test this idea, we asked whether the activity of the preformed, active cyclin A/CDK2 complexes that are present in HeLa-HU phase extracts were affected by p27-induced cleavage of the cyclin A partner. Since p27 can independently inhibit kinase activity (see Introduction) and induce cleaving activity (Fig. 4B), we separated p27 from the cleaving activity by using the strategy described earlier. p27 was first translated in RL to induce the appearance of cleaving activity and then removed from the lysate by immunodepletion. The immunodepleted supernatant, which lacks p27 but still contains cleaving activity, was then incubated with HeLa-HU extract to induce cleavage of endogenous cyclin A. Cyclin A cleavage was monitored on immunoblots (Fig. 5B Upper). To test for associated kinase activity, cyclin A immunoprecipitates were assayed for kinase activity toward histone H1, a standard substrate (Fig. 5B Lower). The results demonstrate both that cyclin A complexed with CDK can be cleaved and that this cleavage does not affect their kinase activity. Thus, p27 is capable of generating the formation of active CDK complexes containing truncated cyclin A, and such complexes evade destruction by the D-box-dependent APC/C pathway.

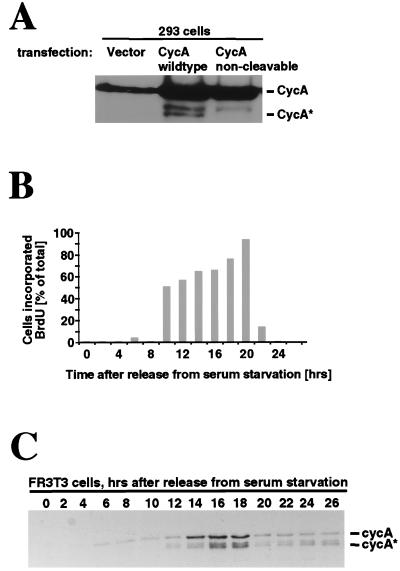

In Vivo Cleavage of Cyclin A.

Since cyclin A cleavage can be easily detected in vitro, and certain cell lines show potential cyclin A cleavage products in vivo (see below), we undertook preliminary experiments investigating cyclin A cleavage in vivo. 293 (human) cells were transfected with cDNAs encoding either wild-type or a noncleavable mutant of cyclin A and then were analyzed on immunoblots using cyclin A antibodies. In untransfected asynchronously dividing cells, where cyclin A levels are relatively low, a potential cleavage product of cyclin A was not readily apparent (Fig. 6A, lane 1). However, when cyclin A was overexpressed in these cells, two smaller forms were detected (lane 2), and the most rapidly migrating one co-migrated with human cycA*. Most importantly, this band was absent from cells transfected with the noncleavable cyclin A mutant (lane 3), arguing that it was generated by cleavage in vivo. The identity of the middle band is unknown.

Figure 6.

In vivo cleavage of cyclin A. (A) Cyclin A is cleaved in vivo in 293 (human) cells. 293 cells were transfected with empty vector (lane 1), wild-type cyclin A cDNA (lane 2), or a noncleavable mutant of cyclin A cDNA (lane 3). Extracts of transfected cells were analyzed by SDS/PAGE followed by immunoblotting with cyclin A antibodies. (B) Bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation of FR3T3 (rat) cells after release from serum starvation. FR3T3 cells were serum starved for 72 hr and released into medium containing 10% serum. At each time point cells were pulse-labeled with bromodeoxyuridine to monitor DNA synthesis. (C) Detection of cycA* in FR3T3 cells. After release from serum starvation FR3T3 cells were taken at 2-hr intervals and processed for immunoblotting using mouse-specific cyclin A antibodies.

There are a few examples of previous studies in which potential cyclin A cleavage products are clearly evident (67–69). One of the more striking is provided by a study using FR3T3 cells, a nontransformed rat fibroblast cell line, in which immunoblots reveal accumulation of both full-length cyclin A and a smaller protein in the size range of cleaved cyclin A during S phase (67). We thus asked whether the smaller form of cyclin A might correspond to cleaved cyclin A. FR3T3 cells were synchronized in G0, released into the cell cycle by addition of serum, and assayed at 2-hr intervals for both DNA synthesis (Fig. 6B) and cyclin A profiles (Fig. 6C). The level of full-length cyclin A increased sharply around the time of the G1/S transition and remained high during S phase, as did a more rapidly migrating doublet of cyclin A. This pattern closely resembles that seen previously in FR3T3 cells (67) and in 293 cells (Fig. 6A). To ask whether either of the smaller cyclin A bands could represent the cleaved form, we compared their mobilities with the mobility of cleaved cyclin A. Because rat cyclin A has not yet been cloned, we used the mouse cyclin A2 as substrate in the p27-induced cleavage reaction to generate a size marker for cleaved rodent cycA*. The most rapidly migrating band of rat cyclin A comigrated with the cleaved form of mouse cyclin A2, consistent with the hypothesis that it represents an in vivo cleavage product of an A2-type of rodent cyclin.

Attempts to increase the level of the presumptive cleavage form by ectopic expression of p27 were inconclusive, in both FR3T3 and 293 cells. This could be because a component of the p27-inducible protease system, although readily detectable in reticulocyte lysate, is rate-limiting in these cells. Alternatively, cyclin A cleavage could be restricted to certain cell cycle conditions, to certain lineages, or to certain physiological circumstances. Understanding the consequences of cyclin A cleavage in vivo, and how p27 is involved in this event, are important goals of future studies.

DISCUSSION

The results presented here reveal (i) a previously unknown property of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27, its ability to induce the selective cleavage of an A-type cyclin; (ii) the existence of a latent protease that can be activated in response to p27; and (iii) a new proteolytic modification of certain A-type cyclins.

The Kip/Cip CKI family members p21, p27, and p57 contain conserved N-terminal domains responsible for binding and inhibiting cyclin/CDK complexes, and highly divergent C-terminal domains that are believed to be largely responsible for the functional differences among the three classes. In p21, each domain can independently arrest cell cycle progression, at least experimentally: the N terminus inhibits a broad range of cyclin/CDK activities, and a small region within the C terminus binds and inhibits PCNA, an essential component of DNA polymerase. The same is true for p57, although its additional sequence diversity within the C-terminal domain suggests that this region plays other roles as well (see Introduction). By contrast, the C-terminal domain of p27 lacks a PCNA-binding motif and fails to bind PCNA (25). The demonstration that p27 induces a proteolytic activity that selectively targets another cell cycle regulator, and that the C terminus of p27 is required for this event, now establishes a second activity for p27.

How does p27 induce cyclin A-cleaving activity? Because the N-terminal domain binds to the cyclin A/CDK complex and the C-terminal domain is required for cleavage, it would not have been surprising to find that p27 acts as an adaptor, binding to both the cyclin/CDK complex through N-terminal sequences and the protease through C-terminal sequences. This idea, and other models requiring a direct interaction of p27 with cyclin A, was ruled out by in vitro experiments showing that once the addition of p27 has led to the appearance of cleaving activity, p27 can be removed by immunodepletion and the cleaving activity remains. Since p27 can bind and inhibit cyclin/CDKs, it would not have been surprising to find that p27 inhibits a cyclin/CDK kinase activity that inhibits the protease activity. This idea was ruled out by experiments showing that mutation of p27’s kinase-binding domain, which is essential for its ability to inhibit CDK activity, does not interfere with its ability to generate cyclin A-cleaving activity. Taken together, these results argue that p27 induces activation of a latent protease by a pathway that does not depend on its well-established CDK-inhibitory activity and, instead, requires its distinctive C-terminal domain. The nature of this protease and the molecular pathway connecting p27 to its activation remain to be identified We refer to this protease as Tsap (pTwenty-seven-activated protease).

In mice lacking p27, many organs appear to go through additional rounds of cell division prior to terminal differentiation, and certain tissues are prone to dysplasia and tumor formation (37–39, 70). In humans, decreases in p27 levels are also correlated with tumorigenesis (see, for example, refs. 40–42). Such effects could be attributed solely to p27’s ability to inhibit CDK activity. However, it is also possible that under certain circumstances, p27 is involved in the coordinated cleavage of a set of substrates, in much the same way that the APC/C and caspase pathways each target selected sets of proteins whose coordinated degradation or cleavage brings about massive changes in the state of the cell (5, 6, 71).

What is the function of p27-mediated cleavage of cyclin A in vivo? In vitro, it is clear that active cyclin complexes present in S phase can be cleaved by the p27-activated protease and that complexes containing cleaved cyclin A (cycA*) retain high histone H1 kinase activity. One possibility is that cycA* might target its kinase partner to different substrates, to other interacting proteins, or to different locations within in the cell. Apart from a study reporting no obvious differences in cellular localization between full-length cyclin A and a construct lacking the entire N-terminal region (72), there is no information on this point in somatic cells. Furthermore, since cyclin A is unusual among the cyclins in that it is required for two very different cell cycle events, the G1/S transition and entry into mitosis (68, 73), it will be important to determine whether cyclin A cleavage might be involved in either of these transitions, or in some other event such as checkpoint arrest, cell cycle exit, or differentiation.

S-phase complexes containing cleaved cyclin A retain kinase activity. Cleaved cyclin A, which lacks the D box, is resistant to D-box-dependent, APC/C-mediated destruction during completion of mitosis and progression through G1. Thus, an obvious possibility is that cleaved cyclin A would accumulate during the cell cycle, fail to be destroyed during mitosis, and thus delay or block exit from mitosis into G1 of the next cell cycle. However, this may not be the case. Our preliminary studies with synchronized FR3T3 cells in vivo indicate that levels of the presumptive cleaved form, which appears prominently during S phase, decline later in the cell cycle, suggesting that cleaved cyclin A can be degraded by a D-box-independent pathway. In vivo studies investigating the circumstances under which this pathway is utilized and the biological consequences of cyclin A cleavage are obvious and important next steps.

Acknowledgments

We are immensely grateful to all of the people who sent the many constructs listed above. We thank all of the members of the Ruderman lab for their advice, enthusiasm, and help during this work. We are grateful to Heike Krebber, Anindya Dutta, and Elaine Elion for comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by postdoctoral fellowships from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (H.B.) and the American Cancer Society (F.M.T.) and by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (J.V.R.).

ABBREVIATIONS

- CDK

cyclin-dependent kinase

- CKI

CDK inhibitor

- APC/C

anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome

- PCNA

proliferating cell nuclear antigen

- HA

hemagglutinin

- RL

reticulocyte lysate

References

- 1.Sherr C J. Cell. 1993;73:1059–1065. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90636-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pines J. Trends Biochem Sci. 1993;18:195–197. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(93)90185-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hengst L, Reed S I. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1998;227:25–41. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-71941-7_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sherr C, Roberts J. Genes Dev. 1995;9:1149–1163. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.10.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.King R W, Deshaies R J, Peters J, Kirschner M. Science. 1996;274:1652–1659. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5293.1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Townsley F, Ruderman J V. Trends Cell Biol. 1998;8:238–244. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(98)01268-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morgan D O. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1997;13:261–291. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.13.1.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sherr C. Science. 1996;274:1672–1677. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5293.1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dynlacht B D, Ngwu C, Winston J, Swindell E C, Elledge S J, Harlow E, Harper J W. Methods Enzymol. 1997;283:230–244. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(97)83019-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.El-Deiry W S, Tokino T, Velculescu V E, Levy D B, Parsons R, Trent J M, Lin D, Mercer W E, Kinzler K W, Vogelstein B. Cell. 1993;75:817–825. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90500-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harper J W, Adami G R, Wei N, Keyomarsi K, Elledge S J. Cell. 1993;75:805–816. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90499-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dulic V, Kaufmann W K, Wilson S J, Tlsty T D, Lees E, Harper J W, Elledge S J, Reed S I. Cell. 1994;76:1013–1023. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90379-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.El-Deiry W, Harper J W, O’Connor P M, Velculescu V E, Canman C E, Jackman J, Pietenpol J A, Burrell M, Hill D E, Wang Y, et al. Cancer Res. 1994;54:1169–1174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Noda A, Ning Y, Venable S F, Pereira S O, Smith J R. Exp Cell Res. 1994;211:90–98. doi: 10.1006/excr.1994.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Halevy O, Novitch B, Spicer D, Skapek S, Rhee J, Hannon G, Beach D, Lassar A. Science. 1995;267:1018–1021. doi: 10.1126/science.7863327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Macleod K F, Sherry N, Hannon G, Beach D, Tokino T, Kinzler K, Vogelstein B, Jacks T. Genes Dev. 1995;9:935–944. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.8.935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu M, Lee M H, Cohen M, Bommakanti M, Freedman L P. Genes Dev. 1996;10:142–153. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.2.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parker S B, Eichele G, Zhang P, Rawls A, Sands A T, Bradley A, Olson E N, Harper J W, Elledge S J. Science. 1995;267:1024–1027. doi: 10.1126/science.7863329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deng C, Zhang P, Harper J W, Elledge S J, Leder P. Cell. 1995;82:675–684. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90039-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Waldman T, Kinzler K W, Vogelstein B. Cancer Res. 1995;55:5187–5190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee M H, Reynisdottir I, Massague J. Genes Dev. 1995;9:639–649. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.6.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matsuoka S, Edwards M C, Bai C, Parker S, Zhang P, Baldini A, Harper J W, Elledge S J. Genes Dev. 1995;9:650–662. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.6.650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang P, Liégeois N J, Wong C, Finegold M, Hou H, Thompson J C, Silverman A, Harper J W, DePinho R A, Elledge S J. Nature (London) 1997;387:151–158. doi: 10.1038/387151a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yan Y, Frisén J, Lee M H, Massagué J, Barbacid M. Genes Dev. 1997;11:973–983. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.8.973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Watanabe H, Pan Z, Schreiber-Augus N, DePinho R A, Hurwitz J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:1392–1397. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nourse J, Firpo E, Flanagan W M, Coats S, Polyak K, Lee M H, Massague J, Crabtree G R, Roberts J M. Nature (London) 1994;372:570–573. doi: 10.1038/372570a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harper J, Elledge S, Keyomarsi K, Dynlacht B, Tsai L-H, Zhang P, Dobrowolski S, Bai C, Connell-Crowley L, Swindell E, Fax M, Wei N. Mol Biol Cell. 1995;6:387–400. doi: 10.1091/mbc.6.4.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Polyak K, Kato J Y, Solomon M J, Sherr C J, Massague J, Roberts J M, Koff A. Genes Dev. 1994;8:9–22. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Toyoshima H, Hunter T. Cell. 1994;78:67–74. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90573-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Slingerland J M, Hengst L, Pan C H, Alexander D, Stampfer M R, Reed S I. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:3683–3694. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.6.3683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hengst L, Dulic V, Slingerland J, Lees E, Reed S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:5291–5295. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.12.5291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coats S, Flanagan W M, Nourse J, Roberts J M. Science. 1996;272:877–880. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5263.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Russo A A, Jeffrey P D, Patten A, Massague J, Pavletich N P. Nature (London) 1996;382:325–331. doi: 10.1038/382325a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hengst L, Reed S I. Science. 1996;271:1861–1864. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5257.1861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kranenburg O, Scharnhorst V, Van der Eb A, Zantema A. J Cell Biol. 1995;131:227–234. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.1.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pagano M, Tam S W, Theodoras A M, Beer-Romero P, Del Sal G, Chau V, Yew P R, Draetta G F, Rolfe M. Science. 1995;269:682–685. doi: 10.1126/science.7624798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kiyokawa H, Kineman R D, Manova-Todorova K O, Soares V C, Hoffman E S, Ono M, Khanam D, Hayday A C, Frohman L A, Koff A. Cell. 1996;78:721–732. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81238-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fero M, Rivkin M, Tasch M, Porter P, Carow C E, Firpo E, Polyak K, Tsai L, Broudy V, Perlmutter R, Kaushansky K, Roberts J M. Cell. 1996;85:733–744. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81239-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nakayama K, Ishida N, Shirane M, Inomata A, Inoue T, Shishido N, Horii I, Loh D Y, Nakayama K. Cell. 1996;85:707–720. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81237-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Loda M, Dukor B, Tam S W, Lavin P, Florentino M, Draetta G F, Jessup J M, Pagano M. Nat Med. 1997;3:231–234. doi: 10.1038/nm0297-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cavelos C, Bhattacharya N, Ung Y C, Wilson J A, Roncari L, Sandhu C, Shaw P, Yeger H, Morava-Protzner I, Kapusta L, Franssen E, Pritchard K I, Slingerland J M. Nat Med. 1997;3:227–230. doi: 10.1038/nm0297-227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cordon-Cardo C, Koff A, Drobnjak M, Capodieci P, Osman I, Millard S S, Gaudin P B, Fazzari M, Zhang Z F, Massague J, Scher H I. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:1284–1291. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.17.1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pines J. Methods Enzymol. 1997;283:99–113. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(97)83010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kunkel T A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:488–492. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.2.488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brandeis M, Hunt T. EMBO J. 1996;15:5280–5289. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Arvand A, Bastians H, Welford S, Ruderman J, Denny C. Oncogene. 1998;17:2039–2046. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shou W, Dunphy W. Mol Biol Cell. 1996;7:457–469. doi: 10.1091/mbc.7.3.457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Su J, Remple R E, Erikson E, Maller J L. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:10187–10191. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.22.10187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Glotzer M, Murray A W, Kirschner M W. Nature (London) 1991;349:132–138. doi: 10.1038/349132a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Luca F C, Shibuya E K, Dohrmann C D, Ruderman J V. EMBO J. 1991;10:4311–4320. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb05009.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Morgan D O. Nature (London) 1995;374:131–134. doi: 10.1038/374131a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Poon R Y C, Hunter T. Oncogene. 1998;16:1333–1343. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhou B, Li H, Yuan J, Kirschner M W. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:6785–6790. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Levkau B, Koyama H, Raines E, Clurman B, Herren B, Orth K, Roberts J, Ross R. Mol Cell. 1998;1:553–563. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80055-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stack J H, Newport J W. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1997;124:3185–3195. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.16.3185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Palombella V J, Rando O J, Goldberg A L, Maniatis T. Cell. 1994;78:773–785. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(94)90482-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tokumoto T, Yamashita M, Tokumoto M, Katsu T, Horiguchi R, Kajiura H, Nagahama T. J Cell Biol. 1997;138:1313–1322. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.6.1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Polyak K, Lee M, Erdjument-Bromage H, Koff A, Roberts J, Tempst P, Massague J. Cell. 1994;78:59–66. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90572-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shiyanov P, Hayes S, Chen N, Pestov D, Lau L, Raychaudhuri P. Mol Biol Cell. 1997;8:1815–1827. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.9.1815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vlach J, Hennecke S, Amati B. EMBO J. 1997;16:5334–5344. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.17.5334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sudakin V, Ganoth D, Dahan A, Heller H, Hershko J, Luca F C, Ruderman J V, Hershko A. Mol Biol Cell. 1995;6:185–198. doi: 10.1091/mbc.6.2.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.King R, Peters J, Tugendreich S M, Rolfe M, Hieter P, Kirschner M W. Cell. 1995;81:279–288. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90338-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Irniger S, Piatti S, Michaelis C, Nasmyth K. Cell. 1995;81:269–277. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90337-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Amon A, Irniger S, Nasmyth K. Cell. 1994;77:1037–1050. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90443-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lorca T, Devault A, Colas P, Van Loon A, Fesquet D, Lazaro J B, Doree M. FEBS Lett. 1992;306:90–93. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80844-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jeffrey P D, Russo A A, Polyak K, Gibbs E, Hurwitz J, Massague J, Pavletich N P. Nature (London) 1995;376:313–320. doi: 10.1038/376313a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Deleu L, Fuks F, Spitkovsky D, Horlein R, Faisst S, Rommelaere J. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:409–419. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.1.409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Girard F, Strausfeld U, Fernandez A, Lamb N J C. Cell. 1991;67:1169–1179. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90293-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dulic V, Stein G, Far D F, Reed S I. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:546–557. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.1.546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Durand B, Fero M, Roberts J, Raff M. Curr Biol. 1998;8:431–440. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70177-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Thornberry N A, Labeznik Y. Science. 1998;281:1312–1316. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5381.1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Maridor G, Gallant P, Goldsteyn R, Nigg E A. J Cell Sci. 1993;106:535–544. doi: 10.1242/jcs.106.2.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pagano M, Pepperkok R, Verde F, Ansorje W, Draetta G. EMBO J. 1992;11:961–971. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05135.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]