Abstract

Alcohol exposure during development can cause variable neurofacial deficit and growth retardation known as fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD). The mechanism underlying FASD is not fully understood. However, alcohol, which is known to affect methyl donor metabolism, may induce aberrant epigenetic changes contributing to FASD. Using a tightly controlled whole-embryo culture, we investigated the effect of alcohol exposure (88 mM) at early embryonic neurulation on genome-wide DNA methylation and gene expression in the C57BL/6 mouse. The DNA methylation landscape around promoter CpG islands at early mouse development was analyzed using MeDIP (methylated DNA immunoprecipitation) coupled with microarray (MeDIP-chip). At early neurulation, genes associated with high CpG promoters (HCP) had a lower ratio of methylation but a greater ratio of expression. Alcohol-induced alterations in DNA methylation were observed, particularly in genes on chromosomes 7, 10 and X; remarkably, a >10 fold increase in the number of genes with increased methylation on chromosomes 10 and X was observed in alcohol-exposed embryos with a neural tube defect phenotype compared to embryos without a neural tube defect. Significant changes in methylation were seen in imprinted genes, genes known to play roles in cell cycle, growth, apoptosis, cancer, and in a large number of genes associated with olfaction. Altered methylation was associated with significant (p < 0.01) changes in expression for 84 genes. Sequenom EpiTYPER DNA methylation analysis was used for validation of the MeDIP-chip data. Increased methylation of genes known to play a role in metabolism (Cyp4f13) and decreased methylation of genes associated with development (Nlgn3, Elavl2, Sox21 and Sim1), imprinting (Igf2r) and chromatin (Hist1h3d) was confirmed. In a mouse model for FASD, we show for the first time that alcohol exposure during early neurulation can induce aberrant changes in DNA methylation patterns with associated changes in gene expression, which together may contribute to the observed abnormal fetal development.

Keywords: fetal alcohol syndrome, epigenetics, MeDIP-chip, sequenom mass array, microarray, neural tube defect

Introduction

Epigenetic modifications, primarily DNA methylation and histone modification, regulate key developmental events, including germ cell imprinting,1 stem cell maintenance,2–7 cell fate and tissue patterning.8 Epigenetics not only affects the expression of individual genes but also plays crucial roles in shaping developmental patterns, contributing to tissue-specific changes and maintenance of cellular memory required for developmental stability.8,9 Moreover, aberrant epigenetic changes in response to environmental stimuli have been shown to contribute to developmental disorders.10

CpG islands are typically defined as short DNA regions of genome containing a high frequency of CG dinucleotides.11,12 CpG islands are often located in promoter regions in the 5' flanking region of housekeeping genes and many tissue-specific genes.11,13,14 Mammalian genome projects have identified approximately 15,500 and 29,000 CpG islands in the mouse and human genomes, respectively.15–18 Methylation of DNA at CpG dinucleotides is an epigenetic modification that plays an important role in the control of gene expression19 and chromosomal structure in mammalian cells.20 Cytosine methylation of the CpG dinucleotide sequence contributes significantly to genomic imprinting8,21 and X-chromosome inactivation,22 and plays a crucial role in the earliest stages of embryogenesis.23 DNA methylation is also a fundamental aspect of programmed fetal development,24 determining cell fate, pattern formation, and terminal differentiation.8

DNA methylation changes are highly orchestrated during mouse embryo development. A cycle of demethylation prior to implantation, followed by a wave of de novo methylation after implantation, establishes embryonic methylation patterns critical for determining somatic DNA methylation patterns.23–26 This phenomenon of epigenetic reprogramming is essential for normal embryonic development, as disruption of the methylation cycle during early development causes neural tube deficits27,28 and studies have further shown that DNA methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1) overexpression results in genomic hypermethylation and embryonic lethality.29,30

Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD), including various degrees of neural developmental deficit, growth retardation, and facial dysmorphology due to exposure to alcohol during pregnancy, is a leading cause of non-genetic mental retardation.31–34 While the underlying mechanism driving FASD remains unclear,35–37 alcohol has multiple effects on methyl donors,38 which in theory, could lead to downstream epigenetic modifications,39 potentially bridging gene-environment interactions and providing a novel mechanism for FASD. Alcohol ingestion in animals has been shown to inhibit folate-mediated methionine synthesis, thereby interrupting critical methylation processes mediated through s-adenosyl methionine, the activated form of methionine and substrate for biologic methylation. Alcohol appears to interfere with the folate-methyl metabolic pathway for methyl donors by inhibiting methionine synthase and methionine adenosyl transferase. Inhibition of methionine synthesis also creates a “methylfolate trap” analogous to what occurs in vitamin B12 deficiency.38 In addition, some evidence indicates that alcohol may redirect the utilization of folate toward serine synthesis and thereby interfere with a critical function of methylene tetrahydrofolate and thymidine synthesis.40,41 The contention of alcohol-induced alteration of fetal DNA methylation has been put forward but not yet established,39,42 and evidence that alcohol causes fetal alcohol damage through altered DNA or histone methylation has not been investigated. However, alcohol exposure has been associated with decreased DNMT mRNA levels in the sperm of male rats exposed to alcohol,43 and substantial evidence supports a significant role for DNA methylation in neural cell lineage differentiation and early brain development.44–47

Altered fetal gene expression patterns after alcohol exposure have been reported,48–51 but the mechanism underlying alcohol-induced changes in gene expression remains to be elucidated. In the current study, we used an established whole-embryo culture system with strictly controlled staging (timed by somite number) and alcohol dose to investigate the effect of alcohol exposure during early embryo development on genome-wide DNA methylation patterns. Methyl-DNA immunoprecipitation followed by microarrays (MeDIP-chip) was used for DNA methylation mapping and measurement across the mouse embryo genome. The methylation microarray data was validated using Sequenom Mass ARRAY and correlated with gene expression data. Average methylation signals in the entire promoter region were used to characterize mouse embryo DNA methylation profiles. In addition, a novel two-consecutive probe analysis was employed to detect alcohol-induced methylation changes in localized genomic regions (the same direction change of two probes stretched over 150 nucleotides). Based on our integrated analysis, we conclude that alcohol exposure during early neurulation induces significant changes in DNA methylation patterns and gene expression that may contribute to FASD development.

Results

Embryonic phenotypes due to alcohol treatment

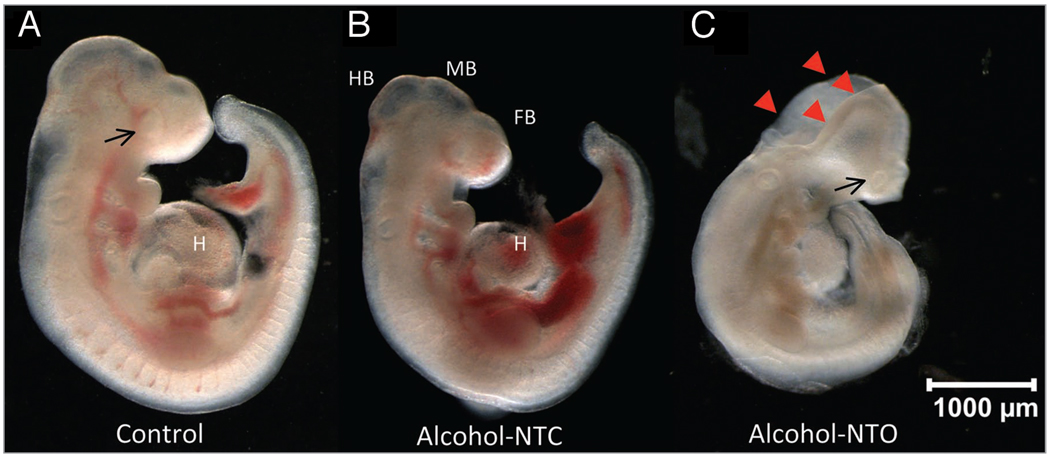

Only embryos that displayed active heartbeats and blood circulation at the end of culture were used for analysis (>95% among all cultured embryos). We observed delayed growth and reduced overall growth of embryos treated with alcohol, in agreement with a previous report.52 Overall growth retardation was accompanied by significant alterations in development of the heart, caudal neural tube, brain vesicles, optic system and limb buds (Fig. 1). Developmental abnormalities in various organ systems (Fig. 1), including abnormalities of the heart and ventricular chambers, a reduced blood/vascular system, flattened forebrain, small/slanted eyes, abnormal tail morphology, abnormal limb web, and an unfinished turning of the neural axis were seen in the alcohol-treated embryos. Furthermore, approximately 33% of the alcohol-treated embryos had a neural tube opening abnormality compared to <5% of the controls. Failure of neural tube closure occurred most frequently in the head fold, although delayed or incomplete neural tube closure in midbrain and hindbrain was also seen. The abnormalities and developmental delays were clearly more severe in alcohol-treated embryos with neural tube opening (ALC-NTO) than in alcohol-treated embryos with neural tube closed (ALC-NTC) subgroups, particularly in development of the neural axis, including hindbrain, midbrain, forebrain and optic vesicle.

Figure 1.

Alcohol-induced dysmorphology of embryonic development at E8.25 + 44 hrs. The alcohol-treated embryos showed developmental delay and abnormality. Several examples (in B and C) are demonstrated in abnormality of the heart (H); small forebrain (FB), midbrain (MB), or hindbrain (HB); small eyes (arrow in C); abnormal tail morphology as compared with Control (A). A major dichotomic phenotype is embryos with neural tube closed but with delay and abnormality in development (NTC, B), and neural tube opened (arrowheads, not closed in time; NTO, C) that accompany more severe dysmorphology. An alcohol-treated embryo with neural tube opened (Alcohol-NTO) is shown in (C). Scale bar: 1,000 micron.

CpG island classification and promoter DNA methylation levels

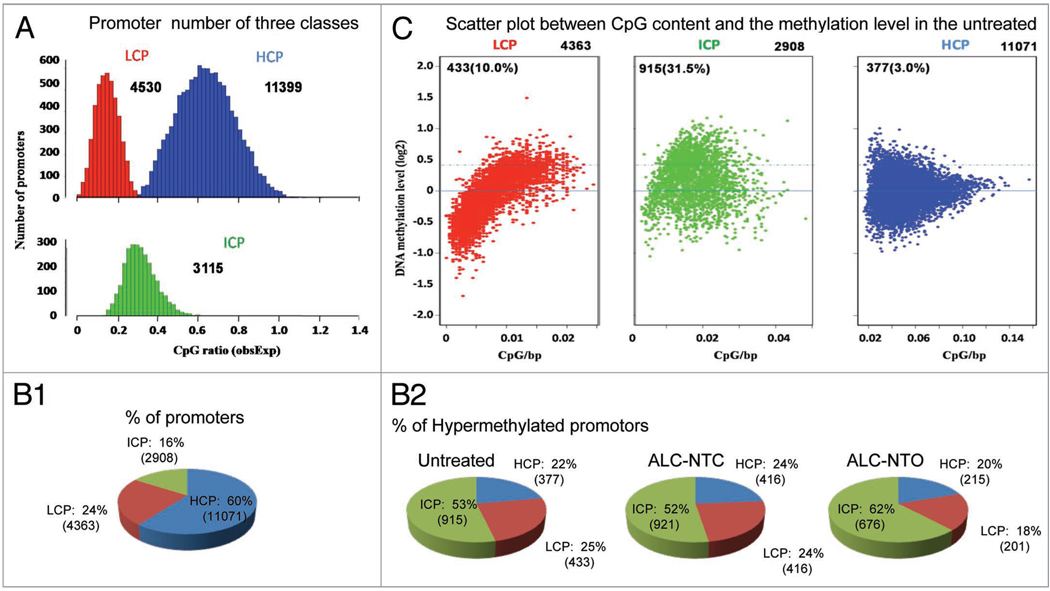

We first categorized 19,044 annotated RefSeq promoters (including 18,342 autosomal chromosomes and 702 promoters on sex chromosomes) into three categories based upon GC content: High (HCP), Low (LCP) and Intermediate (ICP) CpG density (defined in Methods, see Fig. 2A). Among the 18,342 autosomal promoters, more genes were classified as HCP (60%) than ICP (24%) and LCP (16%) (Fig. 2B1). In addition, a contrast between the methylation level profile and CpG density was apparent. Of 1725 hypermethylated promoters (higher than 1.3-fold of the genome-wide median methylation level, see Methods) in the untreated (control) embryos, the number of hypermethylated HCP and LCP genes was significantly lower (22% and 24% respectively), compared to the ICP group (54%) (Fig. 2B2), and a similar distribution was observed in the alcohol-treated group (Fig. 2B2). By plotting the distribution of genome-wide methylation profiles of untreated embryos against the CpG density within each promoter category (Fig. 2C), we observed that DNA methylation levels of the three promoter categories were markedly different during early embryo development (at neurulation stage) chi-square p-value <2.2 × 10−16 against the CpG density (Fig. 2C). The ratio of hypermethylated genes in each category (see dots above the dash line in Fig. 2C) were sharply different, with 3% (of 11,071 genes) in HCP, and 10% (of 4,363 genes) in LCP, compared to 31.5% (of 2,908 genes) in the ICP groups.

Figure 2.

Characterization of DNA methylation patterns in different promoter categories. (A) Histogram of the number of promoters in each category. LCP: low-CpG promoter, ICP: intermediate-CpG promoter and HCP: high-CpG promoters (see definition in text). The definition was based on the sequence identity of the promoters from −1,300 to +500 bp from transcription start site. The number indicates the number of genes in each category of all chromosomes. (BI) Shows the percentage of autosomal genes in three promotor categories (CI; HCP, ICP, LCP), and (B2) the percentage of hypermethylated autosomal genes in control (Untreated) and alcohol-treated with phenotype neural tube closed (ALC-NTC) and neural tube opened (ALC-NTO). In HCP/LCP category, there are less hypermethylated (see definition in C) genes in ALC-NTO than in ALC-NTC. (C) Scatter plot of promoter methylation level and promoter CpG content. X-axis denotes the observed-to-expected CpG ratio, and Y-axis represents the average log2 transformation of the methylation signal level through all the probes in −1,300 to +500 bp from transcription start site; LCP (Red), ICP (green), and HCP (blue) promoters. The dash line at y = 0.4 is defined as cutoff for hypermethylation, which represents 1.3-fold of the genome-wide median methylation level. The dots above this line are considered hypermethylated. This scatter distribution pattern is well-conserved across mouse to human.54

DNA methylation levels and gene expression

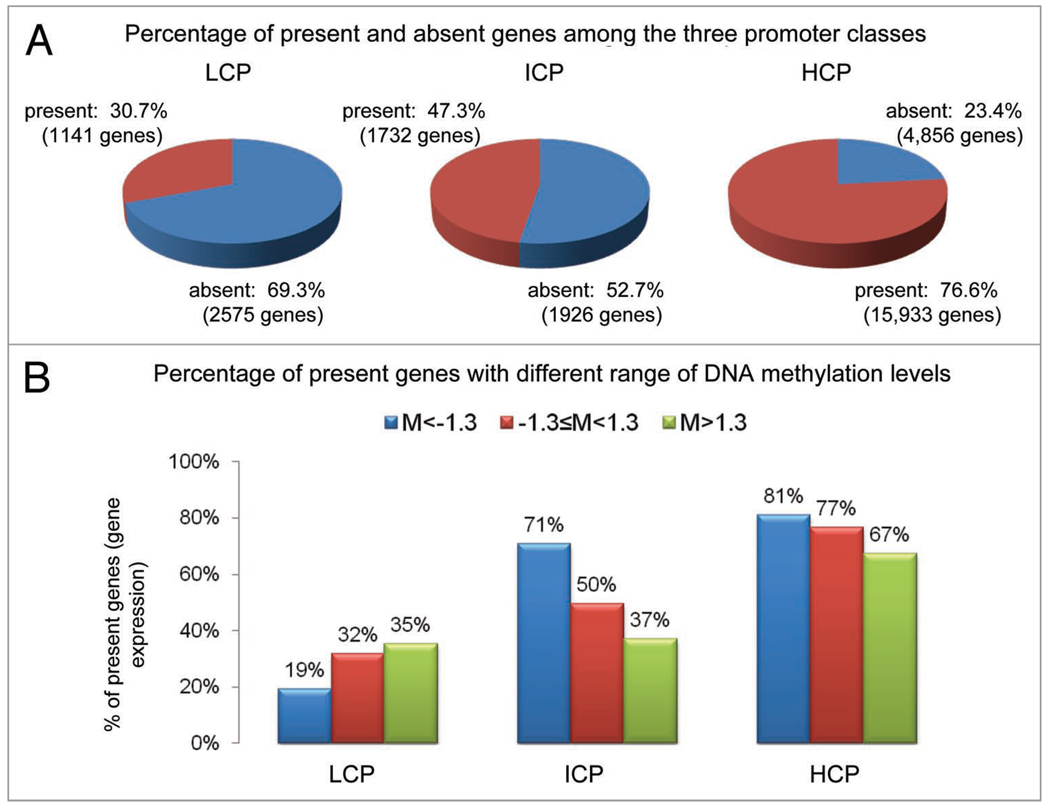

We further compared the DNA methylation patterns of the three promoter classes with gene expression levels (GEO Accession# GSE9545; Affymetrix microarray, n = 4) under the same treatment conditions and experimental settings. The majority of genes in the HCP promoter group were expressed (76.6% of the probe sets can be reliably detected as “present” in Affymetrix microarray by the MAS5 algorithm), followed by ICP (47.3% are “present”) and LCP (30.7%) (Chi-square p-value <2.2 × 10−16). In the ICP group, which contains a high methylation density, there was a clear inverse relationship between gene expression levels and promoter DNA methylation levels, measured by the average signal levels of all the probes in the promoter region (Fig. 3A; chi-square p-value <2.2 × 10−16). Microarray signals for 71% of the hypomethylated ICP promoters (methylation levels were at least 1.3-fold lower than the genome-wide median methylation level) were “present” in the gene expression microarray; in contrast, only 37% hypermethylated promoters were “present” (Fig. 3B; chi-square p-value <2.2 × 10−16).

Figure 3.

Correlation between promoter CpG content, DNA methylation levels, and gene expression levels. (A) Percentage of present genes (detection call >=0.5) whose expression levels can be reliably detected in microarray experiments in LCP, ICP and HCP, respectively. A higher percentage of present genes imply an overall higher gene expression profile. It shows that HCP has the highest percentage of gene expression followed by ICP and LCP. (B) Percentage of present genes with different range of DNA methylation levels in LCP, ICP and HCP. In the ICP and HCP, higher methylation correlated with lower gene expression.

Alcohol modification of DNA methylation level

In many case, “functional” changes in DNA methylation may occur in a short stretch of a promoter CpG island. Thus, instead of analyzing an average methylation change for an entire promoter, we discerned the DNA methylation level changes at a two-consecutive probe-level (same direction change of two probes stretched over 150 nucleotides) (see Methods). A linear mixed-effect model was used to analyze the alcohol-induced methylation changes along the promoter region (see Methods) by comparing control vs. ALC-NTO (neural tube open), and control vs. ALC-NTC (neural tube closed).

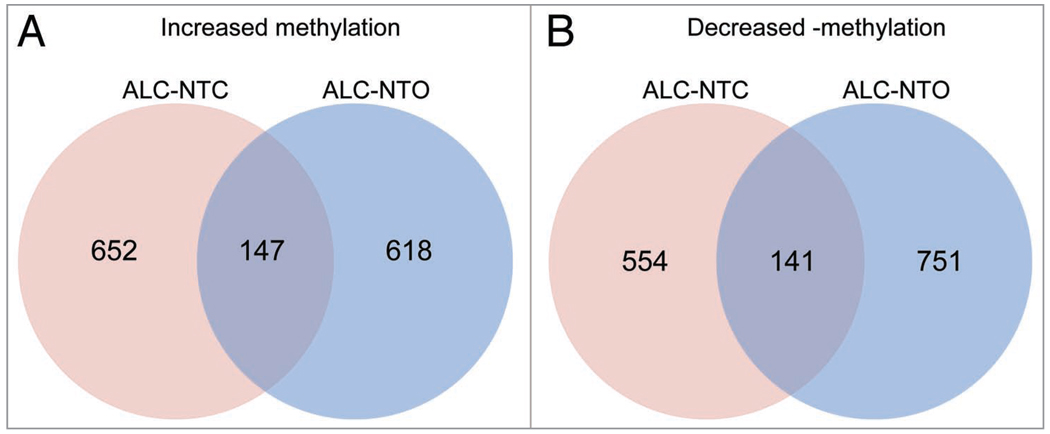

Using this approach, increased methylation in 1,028 genes was observed after alcohol treatment (without consideration of neural tube phenotype), and 1,136 genes showed decreased methylation. When considering the different phenotypes, 1,126 genes displayed increased methylation in the ALC-NTC group, and decreased methylation of 1,030 genes was observed. In the ALC-NTO group, increased methylation of 1,045 genes was seen, and 1,202 genes displayed decreased methylation (p < 0.01). As shown in the Venn diagram in Figure 4, an intersection of the two analyses revealed increased methylation common of 147 genes (Suppl. S1) and decreased methylation of 141 genes (Suppl. S2).

Figure 4.

Venn diagram denoting the number of genes containing at least two differentially methylated consecutive probes. (A) Increased- and (B) Decreased methylation in two statistical comparisons, control vs. ALC-NTC and control vs. ALC-NTO. There are 147 genes with increased methylation levels in both groups, and 141 with decreased methylation levels by alcohol treatment.

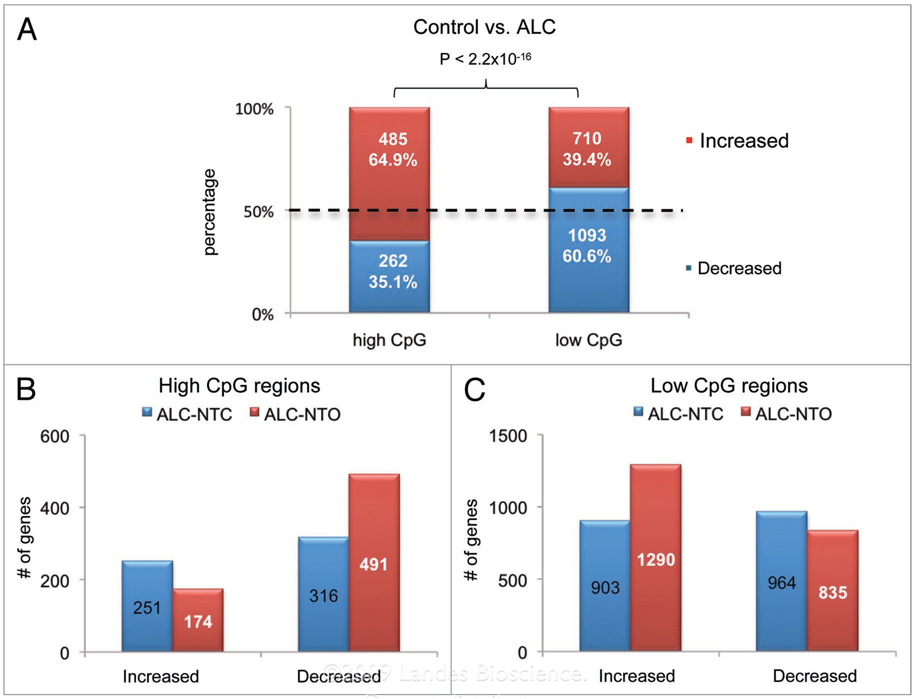

Of the genes showing significant changes in DNA methylation, two features were observed. First, alcohol treatment resulted in more genes with a higher methylation level than normal in the HCP (increased methylation of 485 genes vs. decreased methylation of 262 genes), while the reverse was seen in the LCP (decreased methylation of 1,093 genes vs. increased methylation of 710 genes) (chi-square p-value <2 × 10−16, Fig. 5A). Second, more methylation alterations (both increased- and decreased-methylation) were found in ALC-NTO (1781 methylation changes) than in ALC-NTC (1394 methylation changes). Similar to the first profile, in the HCP region, a greater number of genes displayed increased methylation in ALC-NTO (491 genes) than in ALC-NTC (316 genes). In LCP, the number of genes showing decreased methylation was greater in the ALC-NTO (1290 genes) than in ALC-NTC (903 genes) (Fig. 5B and C).

Figure 5.

Alcohol-induced DNA methylation changes in neural tube open and close groups. (A) Alcohol affected methylation profiles in high-CpG and low-CpG regions (control compared with ALC-NTO, ALC-NTC combined). The genes with regions of high CpG tend to be increased in methylation, while those of low CpG tend to be decreased in methylation. (B) Number of promoters that are increase- or decrease in methylation in two consecutive probes with high CpG contents. (C) Number of increased- or decreased-methylation promoters in two consecutive probes with low CpG content. In the ALC-NTO group, more increased methylation genes with high CpG content, and more decreased methylation genes with low CpG content, were apparent, in agreement with the more severe neural tube development phenotype in ALC-NTO vs. ALC-NTC.

Chromosomal distribution

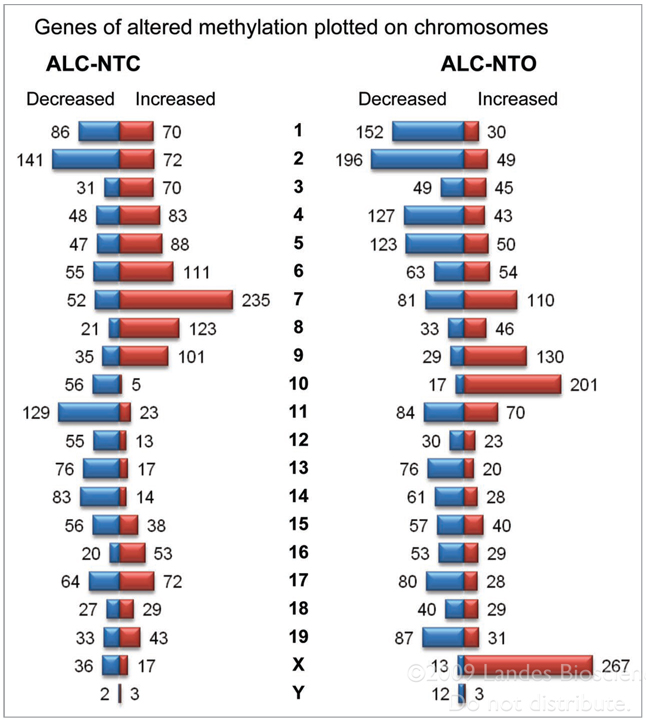

Alcohol-induced methylation alterations in the chromosomal landscape were observed, with a higher overall number of methylation alterations (>200) in chromosomes 7, 10 and X chromosomes (Fig. 6), which are known to contain many imprinted genes and genes prone to silencing. Furthermore, a greater number of methylation alterations were seen in ALC-NTO than in ALC-NTC groups, e.g., 201 increased methylation changes were observed in chromosome 10 of ALC-NTO, but only 5 such changes were seen in ALC-NTC (Fig. 6). In the X chromosome of ALC-NTO, 267 increased methylation changes were found compared to only 17 in ALC-NTC (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Number of genes containing two consecutive probes showing increased- and decreased-methylation in each chromosome. (A) Neural tube close group. (B) Neural tube open group. There are decreased- and increased methylation changes of genes in each chromosome. Highly significant changes were seen in Chromosome 7, 10 and X. These chromosomes are also known to be enriched for imprinted or silenced genes.

Alcohol modification of DNA methylation and gene expression

Altered gene expression after alcohol treatment was also observed, as indicated by the Affymetrix expression microarray analysis of 4 control and 7 alcohol-treated embryos (4 NTC and 3 NTO; database deposited, GEO Accession# GSE9545). By comparing genes with altered DNA methylation (p < 0.01) and altered expression (p < 0.01), 84 genes showed alterations in both, and these genes were associated with multiple functions, including chromatin remodeling (chromatin accessibility complex 1, Chracl; bromodomain and WD repeat domain containing 1, Brwd1; and TH1-like homolog, TH1l), ubiquitin (UEb3c), homeobox (forkhead box P3, Foxp3; wingless-related MMTV integration site 6, Wnt6), neuronal morphogenesis and synaptic plasticity (WASP family 1, Wasf1), hemopoiesis (glycophorin A, Gypa), and neural developmental-related genes (see below).

Sequenom mass ARRAY validation of MeDIP microarray

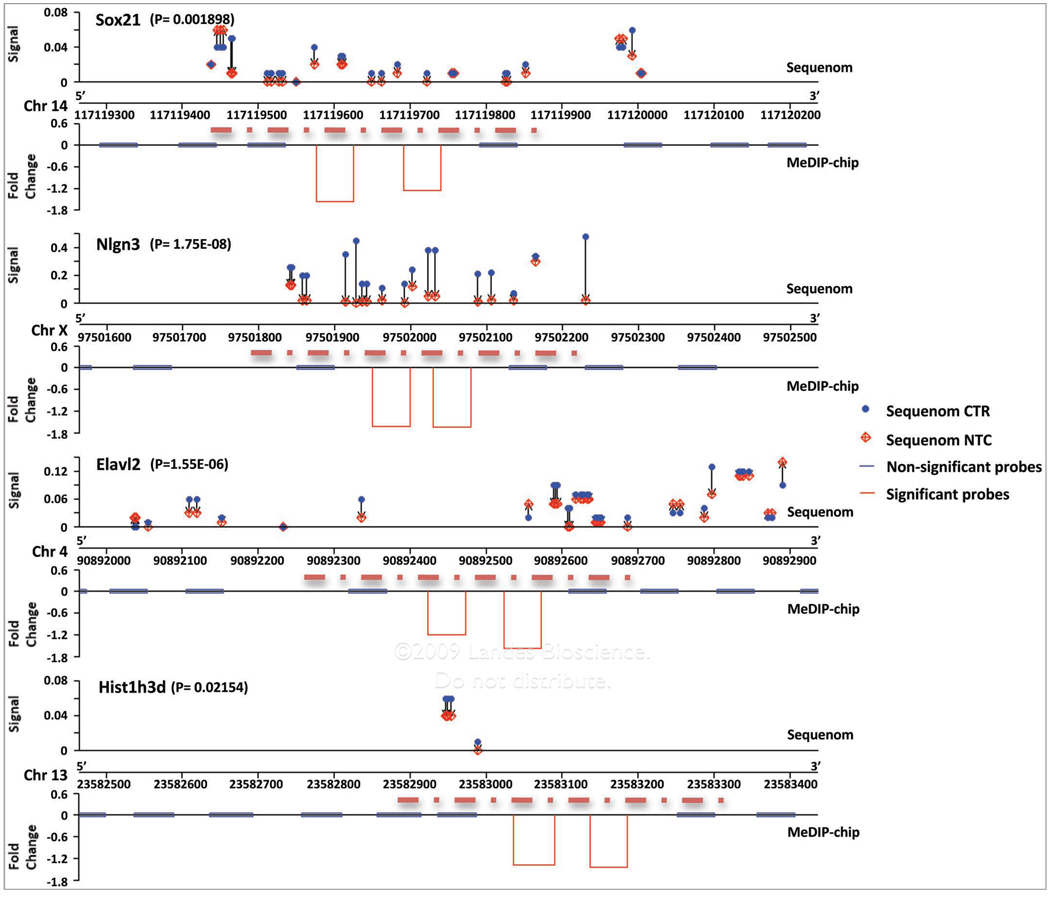

Sequenom technology was utilized to validate the methylation microarray findings (see Methods). An example of alignment between Sequenom and MeDIP for four genes is shown in Figure 7. Decreased methylation of Elavl2 (Embryonic lethal, abnormal vision, Drosophila-like 2; a.k.a. Hu antigen B), Sox21 (SRY-box containing gene 21), Sim1 (single minded homolog 1), Hist1h3d (histone cluster 1, H3d), Igf2r (insulin-like growth factor 2 receptor), and Nlgn3 (neuroligin 3), and increased methylation of Cyp4f13 (cytochrome P450, family 4, subfamily f, polypeptide 13) was confirmed using Sequenom technology. Furthermore, decreased methylation of Elavl2 and Sox21 corresponded with increased gene expression, while Nlgn3 and Igf2r expression was not altered significantly. Cyp4f13 expression data was not available.

Figure 7.

Sequenom analysis confirming key alcohol-induced DNA methylational changes for (A) Sox21, (B) Nlgn3, (C) Elavl2 and (D) Hist1h3d. For each gene, the upper panel shows the sequenom-detected methylation signal along the genomic DNA region being targeted. The blue circles and red diamonds indicate the % of methylated CpGs in control and alcohol-treated conditions. The lower panel shows the correspondent MeDIP-chip-derived changes; the red dash line between the sequenom and MeDIP-chip data demonstrates the projected genomic regions where the MeDIP-derived DNA fragment can reach (150 bp upstream of the 5'-end and 150 bp downstream of the 3'-end of the two-consecutive probes). The blue bars indicate the positions of probes whose methylational changes are not statistically significant. The red bars denote the fold changes of the two probes whose alcohol-induced methylational changes are statistically significant, based upon the two consecutive analyses.

Discussion

CpG island landscape, methylation patterns and transcription at early neurulation

The present study represents the first genome-wide methylation pattern analysis at the mouse neurulation stage. Differences in DNA methylation patterns for three classes of CpG islands—HCP, LCP and ICP—were observed during early development. Furthermore, by comparing our data with recently published studies on CpG distribution patterns around promoter regions, we found that the promoter CpG landscape was remarkably conserved among mouse embryonic stem cells,53 mouse developing embryos (current study), and differentiated human fibroblast cells,54 allowing DNA methylation profiles to be compared in various stages across species, supporting the belief that CpG island patterns are evolutionally conserved and biologically significant. Among CpG island distribution categories, many HCP genes are known to be associated with ubiquitous housekeeping genes and highly regulated, key developmental genes, while LCP genes are generally associated with tissue-specific genes55,56 suggesting that analyzing methylation changes according to CpG density profiles may provide additional functional insight, as discussed below.

DNA methylation levels differed markedly among the three CpG promoter density profiles at the early neurulation stage. The incidence of hypermethylation in HCP was low, correlating with active transcription at the beginning of neurulation, a period of rapid growth. In addition, the number of expressed genes was two-fold greater than in the HCP than in the LCP promoter group, in agreement with a previous study,56 predicting expression of more housekeeping and developmental genes than tissue-specific genes at this early stage of development. This DNA methylation-to-transcription trend was much less apparent in the lower promoter CpG density genes; i.e., in the ICP group, about 1/3 of genes were hypermethylated (Fig. 2C) while 1/2 of genes were silent (Fig. 3A). In the LCP group, most of the genes remained silent but not hypermethylated. Although our findings demonstrate a strong reverse correlation of gene expression level with methylation level, we are not attempting to absolutely link hypomethylation and gene expression. For instance in HCP, 3% genes are hypermethylated, while 76.6% are expressed. However, for individual genes, the expression level is dependent on the transcription factors that are recruited to the methylation sites. Our findings suggest that at the embryonic stage, DNA methylation has a stronger influence on HCP compared to LCP genes, and in our future studies we will extend this analysis to include activating and repressive histone marks associated with these promoter categories.

The distribution of DNA methylation patterns among the three CpG promoter density profiles (Fig. 2) is remarkably similar across species and tissue types,53,54 indicating that methylation pattern across CpG density is evolutionarily well-conserved from mouse to human. The fact that the methylation profiles are eliminated and reprogrammed twice in the life-cycle of each organism implies that maintaining methylation stability is crucial for establishing gene expression programs that are essential for functional maintenance of an organism. Also worthy of mention, in the LCP group, the methylation level increased with increasing CpG content (Fig. 2C), suggesting a relationship between CpG dinucleotide availability and DNA methylation levels. In the ICP group, a bell-shape distribution of methylation was observed, with the highest methylation levels at 0.02 CpG/bp (middle of the plot). In the HCP group, representing a majority (~60%) of the genes, the greater divergence of methylation was at lower CpG levels, and the methylation levels were reduced to the genome-wide median level as the CpG content increased (Fig. 2C). Most of the hypermethylated promoters in HCP have a lower CpG content, an observation consistent with the fact that CpG dinucleotides are reduced in vertebrate genomic DNA due to deamination and elimination of mutations during evolution.57 Overall, our results demonstrate that (a) promoter methylation density is related to CpG island density; (b) methylation density has a stronger influence on gene expression than CpG island density; and (c) in ICP and HCP, methylation favors transcriptional repression.

Effect of alcohol on DNA methylation and phenotype

We noted two trends in alcohol-induced, DNA methylation landscape changes. First, alcohol treatment was associated with a characteristic pattern of both increased and decreased DNA methylation: more genes showed a methylation increase in the HCP group, while a methylation decrease was noted for more genes in the LCP group. Second, this methylation pattern appeared to be associated with the severity of the neural tube abnormality phenotype (NTO vs. NTC): (a) in general, there were more methylation alterations (both increased- and decreased-methylation) in ALC-NTO than in ALC-NTC; (b) significantly, in the HCP, greater increased methylation occurred in ALC-NTO than in ALC-NTC, while in LCP, more decreased methylation occurred in ALC-NTO than ALC-NTC. As both of these trends were greater in ALC-NTO with severe neural tube defects than in ALC-NTC with an intact neural tube, this result demonstrates a correlation between methylation changes and alcohol-induced neural tube defects. This trend is more clearly demonstrated when the genes with methylation changes are plotted in each chromosome (discussed see below).

Alcohol-induced methylation alterations in chromosomes containing a large number of imprinted genes and genes prone to silencing were observed (Fig. 6 and Table 3). Chromosome 7 is known to contain clusters of imprinted genes (e.g., Igf2, Ube3a) that mediate embryonic growth and development. Increased methylation of a large number of genes in alcohol-treated embryos with more severe neural tube defects (i.e., ALC-NTO as compared to ALC-NTC) was particularly evident in Chromosome 10 and the X chromosome. A remarkable ~15-fold increase in methylated genes in the X chromosome was observed when neural tube development was compromised by alcohol treatment. While already containing many silenced genes,58 our data indicates further DNA methylation-mediated repression of the X chromosome, perhaps suggesting a compelling new hypothesis that large-scale alcohol-induced methylation changes in the X chromosome contributes to neural tube defects.

Table 3.

List of imprinted genes with DNA methylation changes in ALC-NTC and ALC-NTO

| Treatment group | Increased Methylation |

Decreased Methylation |

|---|---|---|

| ALC-NTC | Cdkn1c, Ube3a | Grb10, Igf2r, Slc22a18 |

| ALC-NTO | Ube3a | Gatm, H19, Igf2r, Nnat |

DNA methylation alteration of specific gene profiles

By intersecting the genes showing alcohol-induced increased methylation among the two neural tube phenotypes, we identified 147 genes common to both NTO and NTC alcohol-treated groups (Fig. 4). Ingenuity Pathway Analysis showed that these genes are involved in key embryonic developmental events, such as Enah (Enah enabled homolog) in neurulation of neural tubes as well as corpus collosum development, Ets (26 avian leukemia oncogene) and Vaxl (ventral anterior homeobox containing gene 1) in differentiation of embryonic tissue (Table 1). Also, 141 genes with decreased methylation were common to both phenotypes (NTO and NTC) (Fig. 4). Ingenuity Pathway Analyses revealed that these genes are involved in the development of cardiomyocytes (Ptpn11), ventralization of retina (Vax2), development of the sensory nervous system (Kif1a), neuroprotection of granule cells (Crh), and migration of embryonic stem cells (Srf) (Table 1). In addition, DNA methylation changes were seen in a group of genes involved in developmental syndromes that share common phenotypes with FAS (Table 2A), as indicated by a recent report by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC Guidelines for Referral and Diagnosis, July 2004). The phenotypes of nine syndromes—Aarskog syndrome, Williams syndrome, Noonan’s syndrome, Dubowitz syndrome, Brachman-Delange syndrome, Toluene embryopathy, Fetal hydantion syndrome, Fetal Valproate syndrome, and Maternal PKU fetal effects—all display considerable overlap with FASD. MeDIP-chip analysis identified gene DNA methylation changes in both NTC and NTO phenotype involved in three of those syndromes-Williams syndrome (Wbscr 1 and Wbscr 22), Noonan’s syndrome (Ptpn11), and Brachman-Delange syndrome (Nipbl) (Table 2A). In addition, alcohol-induced DNA methylation level changes in genes involved in other developmental syndromes like Angelmann syndrome (UBe3a), Bartter’s syndrome (Bsnd), Cleft palate syndrome (Pdgfra, snai1), and Hurler’s syndrome (Idua) were identified using MeDIP-chip (Table 2B). Furthermore, alcohol also altered methylation in genes known to be imprinted which my interfere (eg. Igf2r) or increase the silencing of gene expression (eg. Ube3a in Angelmann Syndrome-Table 3).

Table 1.

Functional analysis of genes that show increased and decreased methylation in both NTO and NTC group using Ingenuity pathway analysis

| Increased methylation | Decreased methylation | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Function | Molecules | Function | Molecules |

| Alzheimer’s disease, Dysplasia of cerebral cortex | App | Bartter’s syndrome | Bsnd |

| Demyelination of CNS | Mog | Disorganization of Ventricular septum | Srf |

| Heart damage | Hmox1, Trim | Development of cardiomyocytes, Noonan Syndrome |

Ptpn11 |

| Congenital fibrosis of extra ocular muscles, Ptosis | Kif21a | Cranial chondrodystrophy | Pthlh |

| Blepharophimosis | Foxl2 | Lissencephaly, Sub cortical laminar heterotropia | Pafah1b1 |

| Cleft Palate Syndrome, Morphology of Aortic arch | Pdgfra | ALS-Parkinsonism/Dementia | Trpm7 |

| Angelmann Syndrome | Ube3a | Posterior polymorphus corneal dystrophy 1 | Vsx1 |

| Myotonic Dystrophy | Dmpk | Ventralization of Retina, Closure of optic fissure | Vax2 |

| Hurler’s Syndrome | Idua | Development of sensory nervous system | Kif1a |

| Formation of right ventricle of heart | Smyd1 | Neuroprotection of granule cells | Crh |

| Diameter of descending aorta | Efemp2 | Migration of embryonic stem cells | Srf |

| Patterning of Rhombencephalon | Aldh1a1 | Segmentation of somites | Ncstn |

| Neurulation of Neural tube, Development of Corpus col- losum |

Enah | ||

| Differentiation of embryonic tissue | Ets2, Vax1 | ||

| Cleft Palate Syndrome, Production of Neural crest cells | Snai1 | ||

| Maturation of Granule cells | Neurod6 | ||

Table 2.

Genes with DNA methylation changes involved in developmental syndromes, which has a considerable overlap with fetal alcohol syndrome, a severe form of FASD based on CDC reports (2A), and other related developmental syndromes (2B)

| (A) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Syndromes | ALC-NTC Increased Methylation |

ALC-NTC Decreased Methylation |

ALC-NTO Increased Methylation |

ALC-NTO Decreased Methylation |

| William’s | Wbscr22 | Wbscr1 | Wbscr22 | |

| Noonan’s | Ptpn11 | Ptpn11 | ||

| Brachman-Delange | Nipbl | |||

| (B) | ||||

| Syndromes |

ALC-NTC Increased Methylation |

ALC-NTC Decreased Methylation |

ALC-NTO Increased Methylation |

ALC-NTO Decreased Methylation |

| Angelmann | Ube3a | Ube3a | ||

| Bartter’s | Bsnd | Bsnd | ||

| Cleft-palate | Pdgfra, Snai1 | Pdgfra, Snai1 | ||

| Hurler’s | Idua | Idua | ||

Alcohol exposure had a significant effect on the methylation of genes important for olfactory reception 104 genes in ALC-NTC and 98 genes in ALC-NTO (see Suppl. S3), and most of these are LCP genes. Olfactory gene methylation would be consistent with observations that subjects exposed to alcohol prenatally are more likely to associate alcohol odor with memory.59–61 Furthermore, quantitative trait locus (QTL) analysis on alcohol-differentially vulnerable C56/BL6 and DBA2 recombinant inbred (BxD) mice showed a cluster of olfactory receptor genes to be candidate alcohol-sensitive genes (personal communication, Chris Downing, and our unpublished observation).

A number of Sequenom-validated genes were functionally closely related to neural development and neurulation. Altered methylation of key genes relevant to neurons (Elavl2, a Hu antigen expressed in immature neurons62) and glia development (Neuroligin 3, Nlgn3; gain-of-function of Nlgn3 is regarded as a new model for autism spectrum disorders63), neural patterning (Sox21), and neuroendocrine function (Sim1) were observed. Gene expression data was available for Elavl2 and Sox21, and decreased methylation corresponded with increased expression. Furthermore, we validated that Hist1h3d, which encodes a member of the Histone H3 gene family responsible for nucleosome structure, displayed decreased methylation.

We acknowledge that early embryo culture systems do not allow for the evaluation tissue- or cell type-specific change in methylation levels; rather, the results represent an average across embryo cell types and tissues. In this regard, the current analysis does not address methylation changes in genes that may be hypomethylated in one cell type and hypermethylated in another in the same probe regions.64 While the whole-embryo approach is likely to be less sensitive for identifying methylation changes in a very small number of cells, our results clearly demonstrate that it is sufficiently sensitive for identifying small methylation changes in a large number of cells types (discussed above for different genes). To address these and other important issues, our future investigations will include tissue-specific studies of DNA methylation profiling and histone modification. Furthermore, the current approach concentrates on interrogating potential changes in DNA methylation around promoter regions, while distal regulatory elements (enhancer, insulator, intergene and non-code sequence regions) are not included. However, in our future investigations, we will extend the analysis to distal regulatory elements using next-generation, massive parallel-sequencing approaches and elucidate whether promoter methylation distribution correlates with the chromatin state,55 as well as whether methylation patterns and chromatin states associate with differentiation of ES cells to early embryo neurulation and to fully differentiated cells and tissue.

Importantly, many of the genes displaying alcohol-associated methylation changes also demonstrated changes in expression at the mRNA level. Although the mechanism between alcohol-induced epigenetic modification and altered transcription has yet to be elucidated, these events occurred in genes with a functional spectrum related to epigenetics and development, including his-tone modifications, chromatin remodeling and developmental processing neural genes. Collectively, the results indicate that alcohol exposure has the potential to epigenetically modify genes critical in mediating dysmorphology in neurodevelopment, findings that may have major implications in identifying new mechanisms of how alcohol leads to developmental deficits at the epigenetic level.

Methods

Overview

The dysmorphology and phenotype were tested in the whole embryo culture model for alcohol-induced abnormalities with distinct sub-phenotypes related to timely neural tube closure. Described as neural tube closed (NTC), neural tube opened (NTO);65 the heat map of the gene distribution of these two sub-phenotypes are also found sub-clustered (Manuscript in preparation; gene expression profile uploaded in GEO Accession# GSE9545); thus, DNA methylation levels in these two sub-phenotypes were further observed. We mapped the promoter methylome at the early neurulation stage of the embryonic development using a high-throughput analysis, “MeDIP” (methylated DNA immunoprecipitation), coupled with microarray analysis for genome-wide identification of hyper- and hypo-methylation of genes.54 DNA methylation was analyzed mainly at 1.8 Kb promoter regions around transcription start sites (www.nimblegen.com, Madison, WI); validation of the MeDIP results was confirmed by Sequenom Mass ARRAY of target genes.

Embryo culture

We have previously demonstrated that a great degree of inter- as well as intra-uterus variability occurs in the staging of mouse neurulation. A high-throughput analysis using in vivo-derived samples adds a great many confounding factors into high throughput analysis. In this study, we used an established embryo culture system with a narrow mating window and matching somite numbers. Two-month-old C57BL/6 (B6) mice (weighing approximately 20 g) were purchased from Harlan, Inc., (Indianapolis, IN). Upon arrival, mouse breeders were individually housed and acclimated for at least 1 week prior to mating. Mice were maintained on a 12-hr light-dark cycle (light on: 19:00-7:00) and provided laboratory chow and water ad libitum. When a vaginal plug was detected after the mating period, it was designated as gestational day 0 (GD0) or embryonic day 0 (E0). On E8.25, dams were killed by overdose using CO2 gas. The gravid uterus was removed. Decidual tissues and the Reichert membrane were removed carefully and immediately immersed in the PBS containing 4% fetal bovine serum (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), leaving the visceral yolk sac and a small piece of the ectoplacental cone intact. Three embryos bearing 3–5 somites (E8.25 embryo) were placed in a sterile bottle (20 ml) containing a culture medium that consisted of 70% immediately centrifuged heat-inactivated rat serum (Harlan Sprague-Dawley, Inc.,) and 30% PB1 buffer (137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 0.5 mM MgCl2, 8 mM Na2HPO4, 1.47 mM KH2PO4, 0.9 mM CaCl2, 5.6 mM glucose and 0.33 mM sodium pyruvate; pH 7.4). Embryos were then supplemented with penicillin and streptomycin (20 units/ml and 20 microgram/ml, respectively; Sigma). Bottles were gassed at 0 to 22 hr with 5% O2, 5% CO2 and 90% N2 and at 22 to 44 hr with 20% O2, 5% CO2 and 75% N2 in a rotating culture system (B.T.C. Precision Incubator Unit; B.T.C. Engineering, Cambridge, England; 36 rpm) at 37°C. After the pre-culture period (2–4 hr; maximum 4 hr), alcohol exposure was started by transferring the embryos into a medium containing 6 µl/ml of 95% ethanol (approximately 400 mg/dL, or 88 mM) throughout 44 hrs. Before the experiment, the medium alcohol levels in the setting were tested using an Analox alcohol analyzer (Analox Instruments USA, Lunenburg, MA). The control group was cultured in the medium with no ethanol. On Day 2, the culture medium was changed 22 hr after the start of the exposure with the same treatments described above. All cultures were terminated 44 hr from the beginning of treatment. A total of 27 embryos were used in the current; of which 9 were used for MeDIP analysis (control, ALC-NTC and ALC-NT, n = 3 each) in the same run (control, ALC-NTC and ALC-NT, n = 3 each) (see below), and 18 for embryo morphology (control, ALC-NTC and ALC-NT, n = 6 each). A comparable number of control embryos were always included in each batch of culture for each experiment; all arrays were performed in one batch. The concentration of ethanol in the medium over 24 hr was tested at 0, 12 and 22 hr (the timing of medium change) previously, in a separate group not used for vulnerability study.52

Methylated DNA immunoprecipitation (MeDIP)

A total of 9 embryos (control, alcohol with NTC phenotype, and Alcohol with NTO phenotype, n = 3 each) were used for MeDIP analysis. Genomic DNA was extracted from frozen mouse control and alcohol-treated embryos (neural tube open vs. neural tube closed phenotypes) in triplicate using a DNeasy Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Fremont, CA). Briefly, embryos were dounced using a homogenizer on ice and lysed with Proteinase K and tissue lysis buffer for 3 hrs, then precipitated, washed and eluted in elution buffer according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The DNA quality and quantity was assessed using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer with A260 ratio >1.7 and A230 >1.6 considered to be a criteria for quality control. Approximately, 6 µg of genomic DNA from each embryo were sonicated using a Branson sonifier to obtain fragment sizes between 200–1,000 bp (verified on 2% agarose gel; Suppl. Fig. S4). The sonicated DNA, diluted in TE buffer, was heat-denatured for 10 min at 95°C. 20 µl of DNA was removed and stored at −20°C and used as the input DNA sample. The remaining samples were incubated overnight with 5 µg of monoclonal mouse anti 5-methyl cytidine (Eurogentec, SanDiego, CA) in 5X IP Buffer. Then the DNA-antibody mixture was incubated for 2 hr with pre-washed Protein A agarose beads. The mixture was then washed, resuspended and incubated with Proteinase K overnight at 55°C. After phenol and chloroform extraction, DNA was precipitated with 70% ethanol and resuspended in 10 mM Tris-HCl. The final yield was 10–15 ng/µl. 10 ng of input DNA and immunoprecipitated DNA was amplified using Sigma WGA2 Genome Plex kit (Saint Louis, MO) and purified with a Qiaquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Fremont, CA). All the samples were further subjected to quality control analyses by the Nimblegen core facility (Reykjavik, Iceland) and were then labeled with Cy3 (input DNA) and Cy5 (immunoprecipitated DNA) dyes. Labeled input and immunoprecipitated samples were both hybridized to the same 2007-02-27_MM8_CpG island_promoter array (described below) as a two-color experiment and scanned using Nimblescan. The signal intensities for input DNA and immunoprecipitated DNA were used to calculate the ratio of IP/Input DNA.

MeDIP microarray

NimbleGen MM8 promoter plus CpG island tiling array has a total density of 385,000 probes that represent 19,530 mouse promoters and CpG islands per slide. In this array platform, each probe contains ~50 oligonucleotides with ~50 bp gaps within the promoter and CpG island regions. These promoter and CpG islands largely overlap with transcription starting sites of RefSeq genes, covering, by average, 1.3-kb upstream and 0.5-kb downstream of the transcription starting site of 18,340 autosomal genes. In order to avoid biases due to false assigned promoters in intergenic regions, our analysis mainly focused on these well-annotated promoters.

Data analysis

Both average-level and probe-level analyses were performed. In the average-level analysis, we focused on the regulatory regions near transcription start sites (from 1,300-bp upstream and 500-bp downstream of the transcription start sites). This approach avoided noise caused by distal oligonucleotides residing in the upstream intergenic regions and provided a more focused analysis of the region where most transcription factors bind, while allowing our results to be compared with other studies focused on human promoters.54 To closely evaluate methylation patterns in relationship to GC content within regions showing methylation changes, we further examined the GC content of differentially methylated promoter regions at the two-consecutive probe level (the region that encompasses two differentially methylated consecutive probes and their immediate upstream and downstream regions not covered by any other probe, ~250-bp). Regions with over 50% GC content and 0.6 CpG observed to expected ratio were considered as high-CpG regions and others were considered as low-CpG regions.

The probe-level analysis was extended to the entire gene-related promoter and CpG island regions covered by the NimbleGen array, from 1,300-bp upstream to 500-bp downstream of the transcription start site, which ensured characterization of methylation patterns in distal regulatory regions without diluting the signals in the core promoter with increased noise levels. Since sheared DNA fragments ranged from 200–1,000 bp, and each probe covers approximately 50 bp, our conservative analysis used two consecutive probes on the NimbleGen CpG island array (covering 150–200 bp). Using a linear mixed model, we identified DNA regions with increased/decreased methylation levels based on the signal intensities of two consecutive probes between control and alcohol-treated samples. Depending on the NimbleGen probe selection, each promoter or CpG island contains more than one consecutive probe pair. By average, there are 17 probe pairs for each gene. We identified genes that contained no less than one DNA region (two consecutive probes) with increased/decreased methylation levels within 1,300-bp upstream and 500-bp downstream of transcription start sites.

Furthermore, to understand DNA methylation patterns in genomic regions with different CpG densities, promoters were classified into three categories, adopting similar criteria as used in mouse embryonic stem cells.53 Classification was performed according to the CpG content of the promoter within extended regulatory regions of 1,300 bp upstream and 500 bp downstream of the transcription start site; it is recently understood that the effect of CpG methylation is likely to extend beyond the core of promoter regions54,55 and core promoter regions from 500 bp upstream and 200 bp downstream of the transcription start site were also analyzed. High-density CpG promoters (HCP), containing at least one 500-bp region with GC content ≥0.55 and CpG observed to the expected ratio ≥0.6; low-density CpG promoters (LCP), containing no 500-bp interval with CpG observed to the expected ratio ≥0.4; and intermediate-density CpG promoters (ICP) that lie in between HCP and LCP, and are neither HCPs nor LCPs (Fig. 1A). A summarized methylation level was calculated for each gene based on the average signal intensity of all the probes within the gene’s regulatory region, from −1,300 bp to +500 bp (Average level analysis). We considered promoters with DNA methylation levels higher than 1.3-fold of the genome-wide median methylation level as hypermethylated promoters. This threshold is also similar to that used in the MeDIP-chip analysis of human fibroblast.54 Promoters with DNA methylation levels lower than 1.3-fold of the genome-wide median methylation level were considered as hypomethylated promoters.54

Sequenom mass ARRAY EpiTYPER methylation detection

Epityper DNA methylation anlaysis is based on bisulfite conversion of DNA, PCR amplification, followed by in vitro transcription and analysis of cleaved products by Mass Spectrometry (MALDI-TOF). The primers were designed using MethPrimer (www.urogene.org/methprimer) for 33 gene promoter regions with 48 amplicons (103–625 bp with median target length of 400 bp) covering on average of 9 CpGs per amplicon (Suppl. S5). In brief, DNA was isolated as described above for MeDIP analysis from a single embryo with or without alcohol treatment (n = 3 each). The methylation detection was carried in Sequenom facility at San Diego, CA. Approximately 1 µg of DNA from each sample was treated with sodium bisulfite using the EZ DNA methylation kit (ZymoResearch, CA) according to manufacturer’s protocol, and amplification was done using the primers with the T7 promoter tag on the reverse primer. The in vitro transcription was done, followed by site-specific cleavage using MassCLEAVE biochemistry. MassARRAY compact MALDI-TOF mass was used to acquire spectral peaks and converted into methylation ratios using EpiTYPER software.66 Two statistical criteria were used to identify genes validated by sequenom; one with genes showing methylation difference of greater than 10% in at least one CpG probe; furthermore, another criteria was the methylation change in same direction of all CpG probes tested for that gene amplicon.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Sharmila Bapat, National Centre for Cell Science, Pune, INDIA, and Drs. Curt Balch and Fang Fang, Indiana University, for their contribution to the experimental design, Ms. Lijun Ni for the embryonic culture, and Mr. Mingxiang Teng for assistance in Sequenom statistical analysis. This study is supported by NIH AA016698 and P50 AA07611 (Genetics of FAS component) to F.C.Z. Dr. David Crabb is the director of the P50 center grant. Y.L. and K.P.N. are co-investigators in this funded study.

Footnotes

Supplementary materials can be found at: www.landesbioscience.com/supplement/LiuEPI4-7-Sup.pdf

References

- 1.Bartolomei MS. Epigenetics: role of germ cell imprinting. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2003;518:239–245. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-9190-4_21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheng LC, Tavazoie M, Doetsch F. Stem cells: from epigenetics to microRNAs. Neuron. 2005;46:363–367. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kondo T. Epigenetic alchemy for cell fate conversion. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2006;16:502–507. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meshorer E. Chromatin in embryonic stem cell neuronal differentiation. Histol Histopathol. 2007;22:311–319. doi: 10.14670/HH-22.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Surani MA, Hayashi K, Hajkova P. Genetic and epigenetic regulators of pluripotency. Cell. 2007;128:747–762. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tang HL, Zhu JH. Epigenetics and neural stem cell commitment. Neurosci Bull. 2007;23:241–248. doi: 10.1007/s12264-007-0036-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang B, Pan X, Anderson TA. MicroRNA: a new player in stem cells. J Cell Physiol. 2006;209:266–269. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kiefer JC. Epigenetics in development. Dev Dyn. 2007;236:1144–1156. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cavalli G. Chromatin and epigenetics in development: blending cellular memory with cell fate plasticity. Development. 2006;133:2089–2094. doi: 10.1242/dev.02402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhao X, Pak C, Smrt RD, Jin P. Epigenetics and Neural developmental disorders: Washington DC, September 18 and 19, 2006. Epigenetics. 2007;2:126–134. doi: 10.4161/epi.2.2.4236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gardiner-Garden M, Frommer M. CpG islands in vertebrate genomes. J Mol Biol. 1987;196:261–282. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90689-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takai D, Jones PA. Comprehensive analysis of CpG islands in human chromosomes 21 and 22. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:3740–3745. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052410099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bird AP, Taggart MH, Nicholls RD, Higgs DR. Non-methylated CpG-rich islands at the human alpha-globin locus: implications for evolution of the alpha-globin pseudogene. EMBO J. 1987;6:999–1004. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb04851.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Larsen F, Gundersen G, Lopez R, Prydz H. CpG islands as gene markers in the human genome. Genomics. 1992;13:1095–1107. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(92)90024-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feinberg AP. Methylation meets genomics. Nat Genet. 2001;27:9–10. doi: 10.1038/83825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lander ES, Linton LM, Birren B, Nusbaum C, Zody MC, Baldwin J, et al. Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature. 2001;409:860–921. doi: 10.1038/35057062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Venter JC, Adams MD, Myers EW, Li PW, Mural RJ, Sutton GG, et al. The sequence of the human genome. Science. 2001;291:1304–1351. doi: 10.1126/science.1058040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Waterston RH, Lindblad-Toh K, Birney E, Rogers J, Abril JF, Agarwal P, et al. Initial sequencing and comparative analysis of the mouse genome. Nature. 2002;420:520–562. doi: 10.1038/nature01262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miranda TB, Jones PA. DNA methylation: the nuts and bolts of repression. J Cell Physiol. 2007;213:384–390. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones PA, Takai D. The role of DNA methylation in mammalian epigenetics. Science. 2001;293:1068–1070. doi: 10.1126/science.1063852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Falls JG, Pulford DJ, Wylie AA, Jirtle RL. Genomic imprinting: implications for human disease. Am J Pathol. 1999;154:635–647. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65309-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Riggs AD. Pfeifer GP X-chromosome inactivation and cell memory. Trends Genet. 1992;8:169–174. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(92)90219-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kafri T, Ariel M, Brandeis M, Shemer R, Urven L, McCarrey J, et al. Developmental pattern of gene-specific DNA methylation in the mouse embryo and germ line. Genes Dev. 1992;6:705–714. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.5.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Monk M, Boubelik M, Lehnert S. Temporal and regional changes in DNA methylation in the embryonic, extraembryonic and germ cell lineages during mouse embryo development. Development. 1987;99:371–382. doi: 10.1242/dev.99.3.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Howlett SK, Reik W. Methylation levels of maternal and paternal genomes during preimplantation development. Development. 1991;113:119–127. doi: 10.1242/dev.113.1.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sanford JP, Clark HJ, Chapman VM, Rossant J. Differences in DNA methylation during oogenesis and spermatogenesis and their persistence during early embryogenesis in the mouse. Genes Dev. 1987;1:1039–1046. doi: 10.1101/gad.1.10.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dunlevy LP, Burren KA, Chitty LS, Copp AJ, Greene ND. Excess methionine suppresses the methylation cycle and inhibits neural tube closure in mouse embryos. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:2803–2807. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dunlevy LP, Burren KA, Mills K, Chitty LS, Copp AJ, Greene ND. Integrity of the methylation cycle is essential for mammalian neural tube closure. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2006;76:544–552. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Biniszkiewicz D, Gribnau J, Ramsahoye B, Gaudet F, Eggan K, Humpherys D, et al. Dnmt1 overexpression causes genomic hypermethylation, loss of imprinting, and embryonic lethality. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:2124–2135. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.7.2124-2135.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Siedlecki P, Zielenkiewicz P. Mammalian DNA methyltransferases. Acta Biochim Pol. 2006;53:245–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abel EL, Hannigan JH. Maternal risk factors in fetal alcohol syndrome: provocative and permissive influences. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 1995;17:445–462. doi: 10.1016/0892-0362(95)98055-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Autti-Ramo I, Fagerlund A, Ervalahti N, Loimu L, Korkman M, Hoyme HE. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders in Finland: clinical delineation of 77 older children and adolescents. Am J Med Genet A. 2006;140:137–143. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Manning MA, Eugene Hoyme H. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: a practical clinical approach to diagnosis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2007;31:230–238. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2006.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Streissguth AP, O’Malley K. Neuropsychiatric implications and long-term consequences of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Semin Clin Neuropsychiatry. 2000;5:177–190. doi: 10.1053/scnp.2000.6729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goodlett CR, Horn KH. Mechanisms of alcohol-induced damage to the developing nervous system. Alcohol Res Health. 2001;25:175–184. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goodlett CR, Horn KH, Zhou FC. Alcohol teratogenesis: mechanisms of damage and strategies for intervention. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2005;230:394–406. doi: 10.1177/15353702-0323006-07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Riley EP, Thomas JD, Goodlett CR, Klintsova AY, Greenough WT, Hungund BL, et al. Fetal alcohol effects: mechanisms and treatment. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:110–116. doi: 10.1097/00000374-200105051-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mason JB, Choi SW. Effects of alcohol on folate metabolism: implications for carcinogenesis. Alcohol. 2005;35:235–241. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2005.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Haycock PC, Ramsay M. Exposure of Mouse Embryos to Ethanol During Preimplantation Development: Effect on DNA Methylation in the H19 Imprinting Control Region. Biol Reprod. 2009 doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.108.074682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cravo ML, Camilo ME. Hyperhomocysteinemia in chronic alcoholism: relations to folic acid and vitamins B(6) and B(12) status. Nutrition. 2000;16:296–302. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(99)00297-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.LaBaume LB, Merrill DK, Clary GL, Guynn RW. Effect of acute ethanol on serine biosynthesis in liver. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1987;256:569–577. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(87)90614-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Garro AJ, McBeth DL, Lima V, Lieber CS. Ethanol consumption inhibits fetal DNA methylation in mice: implications for the fetal alcohol syndrome. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1991;15:395–398. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1991.tb00536.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bielawski DM, Zaher FM, Svinarich DM, Abel EL. Paternal alcohol exposure affects sperm cytosine methyltransferase messenger RNA levels. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002;26:347–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Feng J, Chang H, Li E, Fan G. Dynamic expression of de novo DNA methyltransferases Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b in the central nervous system. J Neurosci Res. 2005;79:734–746. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.MacDonald JL, Gin CS, Roskams AJ. Stage-specific induction of DNA methyltransferases in olfactory receptor neuron development. Dev Biol. 2005;288:461–473. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.09.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Setoguchi H, Namihira M, Kohyama J, Asano H, Sanosaka T, Nakashima K. Methyl-CpG binding proteins are involved in restricting differentiation plasticity in neurons. J Neurosci Res. 2006;84:969–979. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Takizawa T, Nakashima K, Namihira M, Ochiai W, Uemura A, Yanagisawa M, et al. DNA methylation is a critical cell-intrinsic determinant of astrocyte differentiation in the fetal brain. Dev Cell. 2001;1:749–758. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00101-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Green ML, Singh AV, Zhang Y, Nemeth KA, Sulik KK, Knudsen TB. Reprogramming of genetic networks during initiation of the Fetal Alcohol Syndrome. Dev Dyn. 2007;236:613–631. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miller LC, Chan W, Litvinova A, Rubin A, Comfort K, Tirella L, et al. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders in children residing in Russian orphanages: a phenotypic survey. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30:531–538. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Poggi SH, Goodwin KM, Hill JM, Brenneman DE, Tendi E, Schninelli S, Spong CY. Differential expression of c-fos in a mouse model of fetal alcohol syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:786–789. doi: 10.1067/s0002-9378(03)00841-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xu Y, Liu P, Li Y. Impaired development of mitochondria plays a role in the central nervous system defects of fetal alcohol syndrome. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2005;73:83–91. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ogawa T, Kuwagata M, Ruiz J, Zhou FC. Differential teratogenic effect of alcohol on embryonic development between C57BL/6 and DBA/2 mice: a new view. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29:855–863. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000163495.71181.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fouse SD, Shen Y, Pellegrini M, Cole S, Meissner A, Van Neste L, et al. Promoter CpG methylation contributes to ES cell gene regulation in parallel with Oct4/Nanog, PcG complex, and histone H3 K4/K27 trimethylation. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:160–169. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Weber M, Hellmann I, Stadler MB, Ramos L, Paabo S, Rebhan M, Schubeler D. Distribution, silencing potential and evolutionary impact of promoter DNA methylation in the human genome. Nat Genet. 2007;39:457–466. doi: 10.1038/ng1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mikkelsen TS, Ku M, Jaffe DB, Issac B, Lieberman E, Giannoukos G, et al. Genome-wide maps of chromatin state in pluripotent and lineage-committed cells. Nature. 2007;448:553–560. doi: 10.1038/nature06008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Saxonov S, Berg P, Brutlag DL. A genome-wide analysis of CpG dinucleotides in the human genome distinguishes two distinct classes of promoters. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:1412–1417. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510310103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rollins RA, Haghighi F, Edwards JR, Das R, Zhang MQ, Ju J, Bestor TH. Large-scale structure of genomic methylation patterns. Genome Res. 2006;16:157–163. doi: 10.1101/gr.4362006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Barr H, Hermann A, Berger J, Tsai HH, Adie K, Prokhortchouk A, et al. Mbd2 contributes to DNA methylation-directed repression of the Xist gene. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:3750–3757. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02204-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Abate P, Varlinskaya EI, Cheslock SJ, Spear NE, Molina JC. Neonatal activation of alcohol-related prenatal memories: impact on the first suckling response. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002;26:1512–1522. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000034668.93601.8F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dominguez E, Madrigal JA, Layrisse Z, Cohen SB. Fetal natural killer cell function is suppressed. Immunology. 1998;94:109–114. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1998.00489.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Faas AE, Sponton ED, Moya PR, Molina JC. Differential responsiveness to alcohol odor in human neonates: effects of maternal consumption during gestation. Alcohol. 2000;22:7–17. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(00)00103-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Akamatsu W, Fujihara H, Mitsuhashi T, Yano M, Shibata S, Hayakawa Y, et al. The RNA-binding protein HuD regulates neuronal cell identity and maturation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:4625–4630. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407523102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tabuchi K, Blundell J, Etherton MR, Hammer RE, Liu X, Powell CM, Sudhof TC. A neuroligin-3 mutation implicated in autism increases inhibitory synaptic transmission in mice. Science. 2007;318:71–76. doi: 10.1126/science.1146221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mill J, Tang T, Kaminsky Z, Khare T, Yazdanpanah S, Bouchard L, et al. Epigenomic profiling reveals DNA-methylation changes associated with major psychosis. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82:696–711. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.van Maele-Fabry G, Delhaise F, Picard JJ. Evolution of the developmental scores of sixteen morphological features in mouse embryos displaying 0 to 30 somites. Int J Dev Biol. 1992;36:161–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ehrich M, Nelson MR, Stanssens P, Zabeau M, Liloglou T, Xinarianos G, et al. Quantitative high-throughput analysis of DNA methylation patterns by base-specific cleavage and mass spectrometry. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:15785–15790. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507816102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.