Abstract

Nakiterpiosin and nakiterpiosinone are two related C-nor-D-homosteroids isolated from the sponge Terpios hoshinota that show promise as anti-cancer agents. We have previously described the asymmetric synthesis and the revision of the relative configuration of nakiterpiosin. We now provide detailed information on the stereochemical analysis that supports our structure revision and the synthesis of the originally proposed and revised nakiterpiosin. In addition, we herein describe a refined approach for the synthesis of nakiterpiosin, the first synthesis of nakiterpiosinone, and preliminary mechanistic studies of nakiterpiosin's action in mammalian cells. Cells treated with nakiterpiosin exhibit compromised formation of the primary cilium, an organelle that functions as an assembly point for components of the Hedgehog signal transduction pathway. We provide evidence that the biological effects exhibited by nakiterpiosin are mechanistically distinct from those of well-established anti-mitotic agents such as taxol. Nakiterpiosin may be useful as an anti-cancer agent in those tumors resistant to existing anti-mitotic agents and those dependent on Hedgehog pathway responses for growth.

Introduction

Terpios is a genus of thin, encrusting sponges that harbor large amounts of symbiotic bacteria.1 These sponges are known to aggressively compete with corals for space by epizoism. During 1981–1985, large patches (up to 1000 m in length) of cyanobacteriosponge Terpios hoshinota were observed in Okinawa. They killed large populations of corals in that region and were referred to as black disease. Uemura and co-workers hypothesized that T. hoshinota could secret toxic compounds and kill the covered corals. In a search for these toxins, they isolated 0.4 mg of nakiterpiosin and 0.1 mg of nakiterpiosinone from 30 kg of the sponges.2 Both compounds inhibited the growth of P388 mouse leukemia cells with IC50 10 ng/mL. The structures of these compounds were originally assigned as 3 and 4 based on NMR experiments (Figure 1). They bear a unique molecular skeleton and several unusual functional groups. To date, they are the only C-nor-D-homosteroids isolated from a marine source. We recently proposed to revise their relative configuration to that shown in 1 and 2 by analyzing the spectroscopic data of their fragments. We further synthesized 1 and 3 and confirmed that the structure of nakiterpiosin should be 1.3 We present herein the details of our synthetic studies and spectroscopic analysis of nakiterpiosin (1) and 6,20,25-epi-nakiterpiosin (3). In addition, we report in this article an improved synthesis of 1, the first synthesis of nakiterpiosinone (2) and the results of our preliminary biological studies of 1.

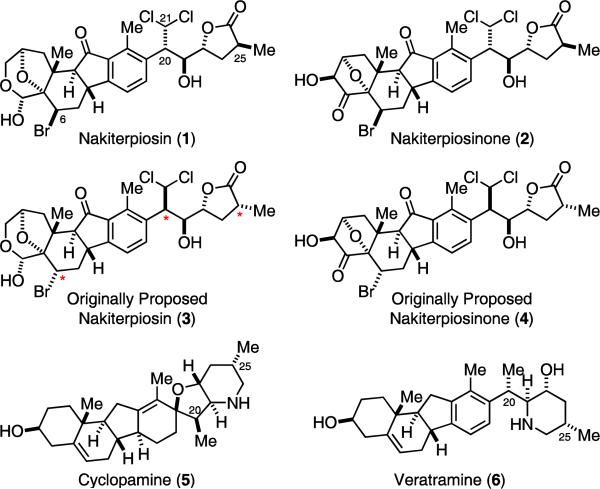

Figure 1.

The structures of C-nor-D-homosteroids 1–6.

C-nor-D-Homosteroids are skeletally rearranged steroids with their C-ring contracted and D-ring expanded by one carbon. The first known, and arguably the best known, members of this family of natural products are cyclopamine (5) and veratramine (6). The discovery of these veratrum alkaloids is a rather interesting story.4 Ranchers in the Rocky Mountain region had long been puzzled by a mysterious birth defect in their sheep. They found that 1–20% of the lambs were born as “chattos (monkey faces)” when the mother sheep grazed in the National Forests in central Idaho during the summer. The Poisonous Plant Research Laboratory of the US Department of Agriculture was contacted in 1954 to investigate this “malformed lamb disease”. After 11 years of work, they found that ewes that grazed on corn lily (Veratrum californicum) on the fourteenth day of gestation would give birth to cyclopic lambs, while the ewes were left unaffected. They further found that 5 was responsible for the one-eye face malformation and 6 led to leg deformity.4a However, it was not until 30 years later that the molecular target of 5 was identified to be Smoothened (Smo).5 Suppression of Hedgehog (Hh) signaling by inhibiting Smo with small molecules has since been pursued as a new strategy for cancer treatment.6 The semi-synthesis of 5 and 6 was first accomplished by Masamune and Johnson in 1967,7a–e and recently by Giannis.7g A formal synthesis was also reported by Kutney in 1975.7f

Revision of the relative stereochemistry

The unique molecular structures and strong P388 growth inhibition activity of nakiterpiosin (1) and nakiterpiosinone (2) prompted us to initiate a research program to explore their laboratory synthesis8 and biological functions. At the onset of this project, we noticed that the C-20 and C-25 configurations of the originally proposed structures for nakiterpiosin and nakiterpiosinone (i.e., 3 and 4)2 were opposite to those of cyclopamine (5), veratramine (6) (Figure 1) and other “normal” steroids. In addition, the C-6 and C-20 configuration of 3 and 4 could not be easily rationalized based on biogenesis analysis.10 We further considered that the reported NOE data of the natural products2 provided little support to the proposed stereochemistry. Most importantly, the 1H NMR spectra of our synthetic intermediates toward 3 displayed significantly different H-6 and H-21 splitting patterns as compared to the natural products. We therefore decided to first study the relative stereochemistry of nakiterpiosin and nakiterpiosinone using model systems.

In order to probe the C-6 stereochemistry of the natural products, we synthesized a series of compounds (7–10)11 that bear the A,B,C-ring systems of nakiterpiosin and nakiterpiosinone. We found that the JH6–H7 of 7 and 9, which bear the same C-6 configuration as nakiterpiosin and nakiterpiosinone, was very different from that of the natural products (Table 1).12 On the other hand, we found that the corresponding C-6 epimers (8 and 10) and the natural products exhibited similar H-6 splitting patterns. We therefore concluded that the C-6 stereocenter of nakiterpiosin and nakiterpiosinone should be (R)-configured.

Table 1.

Probing the C-6 Configuration of Nakiterpiosin and Nakiterpiosinone.

| Nakiterpiosin | Nakiterpiosinone |  |

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JH6–H7a | 2.7 Hz | 2.3 Hz | 12.2 Hz | 3.2 Hz | 11.6 Hz | 3.2 Hz |

| JH6–H7b | 1.4 Hz | 1.4 Hz | 5.6 Hz | 2.8 Hz | 5.5 Hz | 2.8 Hz |

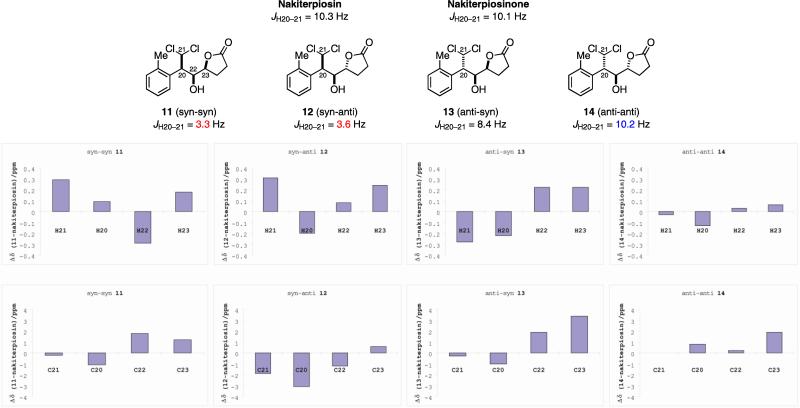

As to the stereochemistry of the side chain of nakiterpiosin and nakiterpiosinone, we first focused on the C-20/C-22/C-23 relative configuration and synthesized all four possible diastereomers (11–14)11 to compare their NMR spectra with those of the natural products. We found that the 3JH–H coupling constants and 1H and 13C chemical shifts of 11 (syn-syn), 12 (syn-anti) and 13 (anti-syn) were considerably different from those of the natural products (Figure 2). In particular, the JH20–H21 of 11 (syn-syn) and 12 (syn-anti) indicated a gauche instead of an anti H-20/H-21 conformation. Only 14 (anti-anti) exhibited similar 1H and 13C NMR spectra compared to those of the natural products.13 We therefore revised the C-20 stereochemistry of nakiterpiosin and nakiterpiosinone to be (S).

Figure 2.

Probing the C-20/C-22/C-23 configurations of nakiterpiosin and nakiterpiosinone.

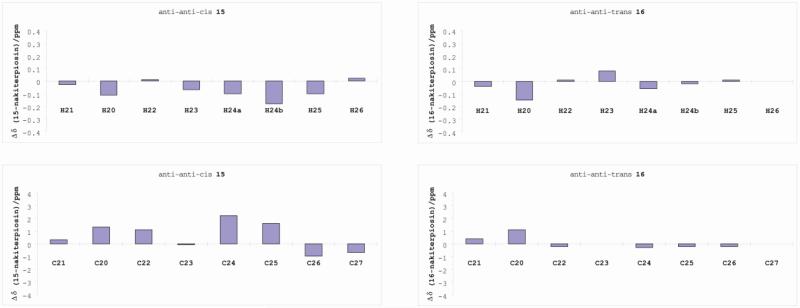

After revising the C-20 stereochemistry, we turned our attention to the C-25 configuration of nakiterpiosin and nakiterpiosinone, synthesizing two model substrates (15 and 16).11 We found that the coupling constants and 1H and 13C NMR chemical shifts of (25S)-16 (anti-anti-trans) but not (25R)-15 (anti-anti-cis) matched well with those of the natural products (Table 2 and Figure 3). In particular, the JH23–H24a, JH23–H24b and JH23–H25 of 15 and those of the natural products were significantly different. We therefore determined that the C-25 stereocenter of nakiterpiosin and nakiterpiosinone should be (S)-configured.

Table 2.

Studies of the C-20/C-22/C-23 configurations of nakiterpiosin and nakiterpiosinone.

| Nakiterpiosin | Nakiterpiosinone |  |

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| JH20-H21 | 10.3 Hz | 10.1 Hz | 10.2 Hz | 10.1 Hz |

| JH23H-24a | 8.2 Hz | 8.2 Hz | 10.0 Hz | 8.0 Hz |

| JH23-H24b | 3.7 Hz | 3.7 Hz | 5.8 Hz | 3.9 Hz |

| JH24aH-25 | 8.4 Hz | 8.2 Hz | 12.1 Hz | 8.3 Hz |

| JH24bH-25 | N/A | 9.2 Hz | 8.8 Hz | 9.4 Hz |

Figure 3.

Probing the C-25 configurations of nakiterpiosin and nakiterpiosinone.

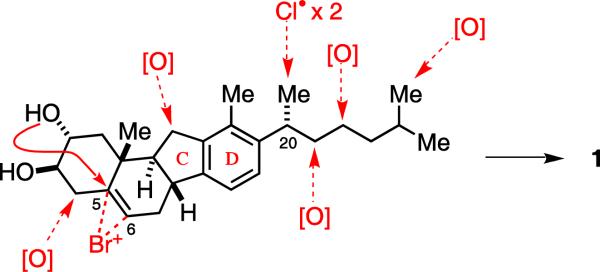

The revised structures of nakiterpiosin and nakiterpiosinone (1 and 2) share the same configurations at the C-20 and C-25 positions with 5 and 6. The C-6 and C-20 configurations are also consistent with the stereochemical outcomes of enzymatic halogenation of the steroid (Figure 4).9 The C-21 chlorine atoms of nakiterpiosin are likely introduced by non-heme iron halogenase through radical chlorination. It is expected that this reaction would lead to retention of the C-20 configuration. On the other hand, the C-6 bromine atom is likely introduced by vanadium-dependent bromoperoxidase through bromoetherification. It is therefore expected that the C-5,6 bromohydrin would exist in an anti stereochemical relationship.

Figure 4.

Biogenetic analysis of nakiterpiosin.

Taken together, we proposed to revise the relative stereochemistry of nakiterpiosin and nakiterpiosinone to 1 and 2. Indeed, we found that the 1H and 13C NMR spectra of our synthetic sample of 1 agreed with those of the natural product. In contrast, those of synthetic 3 and the natural product are significantly different. We thus revised the relative stereochemistry of nakiterpiosin to be that indicated in 1 and 2, which shares the same configuration at the C-20 and C-25 positions with cyclopamine (5) and veratramine (6).

Synthetic plans

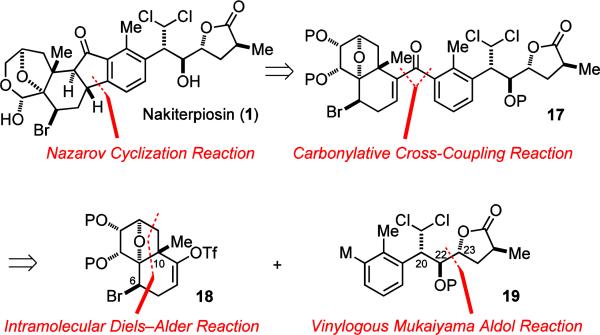

After determining the stereochemistry of nakiterpiosin and nakiterpiosinone to be 1 and 2, we sought to develop a general strategy to target these two steroid derivatives. Our first-generation approach3 is outlined in Figure 5. We opted to construct the central cyclopentanone ring at a late-stage for convergency reasons. We envisioned that a carbonylative cross-coupling reaction14–20 together with a Nazarov cyclization reaction21–23 could be used to effectively assemble this cyclopentanone ring. We recognized that the Nazarov cyclization of vinyl aryl ketone 17 involved a disruption of the aromaticity and therefore required significantly higher activation energy than that of the divinyl systems.22 However, we believed that a suitable set of reaction conditions could be found to realize this highly efficient plan. We also expected that 17 could be used as a versatile intermediate for synthesizing not only 1 but also 2.

Figure 5.

The retrosynthetic analysis of nakiterpiosin.

It should be noted that the carbonylative cross-coupling of 18 and 19 is also considerably challenging because of their sensitive functionalities and congested reaction sites. Compared to the recent advancement in transition metal-catalyzed cross-coupling,24,25 catalytic carbonylative cross-coupling is relatively under-developed.15 Suppression of the direct coupling reactions remains challenging when the more neucleophilic coupling components are used. In general, the Stille and Suzuki carbonylative coupling reactions are more successful because of the slower rate of transmetallation. We later found that the nearly neutral conditions of the Stille carbonylative reaction are crucial to the successful implementation of this strategy to the coupling of highly acid- and base-sensitive 18 and 19.

For the synthesis of the coupling fragments, we envisioned that the electrophilic coupling component 17 could be synthesized by an intramolecular Diels–Alder reaction;26,27 and the nucleophilic coupling component 18 by a vinylogous Mukaiyama aldol reaction.28,29 It should be noted that the intramolecular Diels–Alder reaction of furan derivatives is normally exo-selective and much less kinetically and thermodynamically favored because of the aromaticity of furan and the ring strain of the product.26b The exo selectivity should lead to the desired relative stereochemistry between the oxo bridge and angular methyl group. We planned to use the C-6 stereogenic center to control the diastereoselectivity of this reaction. The use of a substituent group on the tether α to the diene to control the diastereoselectivity was first studied by Roush, Taber and Boeckman.27 Since the C-6 bromine atom resides at the axial position, we anticipated that introduction of the bromine atom to the cycloaddition product with an inversion of configuration would setup the correct C-6 configuration.

In terms of the vinylogous Mukaiyama aldol reaction, we planned to use the C-20 stereocenter to control the installation of the C-22 and C-23 stereocenters. We were able to use this versatile approach to obtain a diverse array of C-20/22/23 diastereomers (11–16: syn-syn, syn-anti, anti-syn, anti-anti) for the previously described model studies.11 The absolute stereochemistry of 18 and 19 were established by the Noyori reduction30 and the Sharpless epoxidation31 reactions.

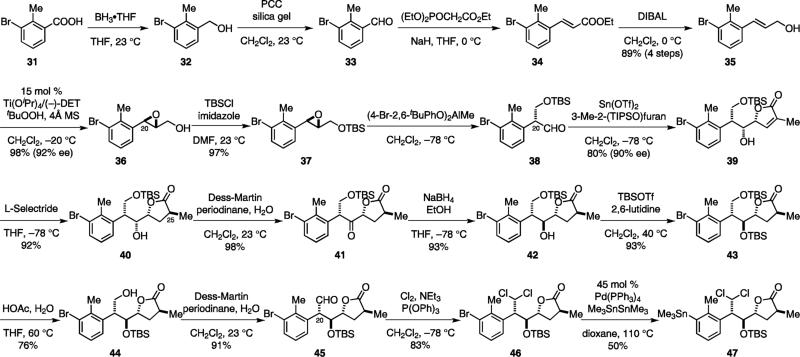

The first generation synthesis of nakiterpiosin

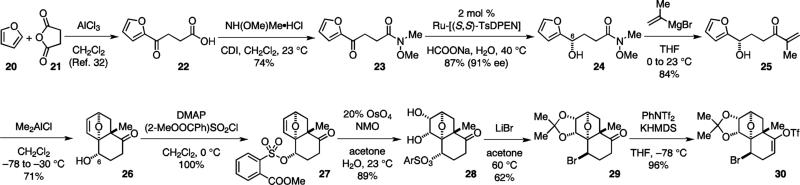

We previously reported our first synthetic approach to 1.3 This sequence commenced with a Friedel–Craft acylation of furan with succinic anhydride32 and the formation of Weinreb amide 23 from acid 22. Subsequently, a Noyori reduction30 was used to set the C-6 stereochemistry. While a significant amount of dehydrated lactone by-product was formed under the conventional NEt3–HCOOH azeotropic conditions,30a,b we found that the in-water protocol developed by Xiao30c–e provided significant enhancement of the reaction rate and allowed low catalyst loading. Alcohol 24 was obtained in 91% ee without the formation of the undesired lactone. The dienenophile was then introduced to 24 by addition of isopropenyl Grignard reagent, giving enone 25, setting the stage for the Diels–Alder cyclization.

It has been shown that the conversion of the intramolecular furan Diels–Alder reaction is highly dependent on the relative basicity of the reactant and product, and the stoichiometry of the Lewis acids.26b We found that, for the reaction of 25, 2.5 equiv of Me2AlCl provided the best yield of 26 (Table 3), indicating that the reaction was driven by the complexation of Me2AlCl to 26. The reaction proceeded with good stereochemical control and gave only the desired exo product with an equatorial hydroxyl group. When the C-6 hydroxyl group of 25 was protected as a TES ether, the reaction proceeded with the opposite enantiomeric preference and provided the exo product with an axial TES ether group.11

Table 3.

Influence of the Lewis acid on the intramolecular Diels–Alder reaction of 25.

| Entry | Lewis Acid | Equivalent | 25:26 | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Me2AlCl | 2.5 | 0:100 | |

| 2 | Me2AlCl | 1.0 | 30:70 | |

| 3 | Me2AlCl | 0.1 | 100:0 | |

| 4 | MeAlCl2 | 1.0 | 15:85 | with decomposition |

| 5 | MeAlCl2 | 0.1 | 100:0 |

Since the cycloaddition product 26 was not stable and underwent a retro-Diels–Alder reaction upon gentle heating or exposure to other Lewis acids, we dihydroxylated the olefin before the introduction of the bromine atom to prevent the retro-Diels–Alder reaction. The steric congestion around the C-6 position necessitated the use of an electron-deficient aryl sulfonate group (27) for 6-OH activation. Thus, treatment of 28 with lithium bromide in warm acetone allowed the introduction of the bromine atom with inversion of configuration and concomitant acetonide protection to give 29. The use of an electron-deficient sulfonate was crucial to the success of this SN2 reaction. 4-Toluenesulfonate (Ts) was unreactive and 4-nitrophenylsulfonate (Ns) was less reactive under these reaction conditions. The absolute and relative configurations of 29 were confirmed by X-ray analysis.11 Finally, enol triflate installation completed the synthesis of the electrophilic coupling component 30.

The synthesis of the nucleophilic coupling component started with reduction of acid 31 to aldehyde 33 followed by Horner–Wadsworth–Emmons reaction and reduction of the resulting ester to afford 35. Asymmetric installation of the C-20 stereocenter was achieved by Sharpless epoxidation with 92% ee.31 The resulting alcohol was protected as a TBS ether and then subjected to the pinacol-type rearrangement using Yamamoto's conditions.33 Previously, we reported that aldehyde 38 was obtained with significant erosion of enantiomeric purity (71% ee).3 We have since determined that the loss of ee occurred during workup of the reaction and purification of 38 by column chromatography. Quenching the reaction with 1 N HCl aqueous solution instead of sodium fluoride afforded 38 with 90% ee. Aldehyde 38 should be used directly without purification. We have also found that while low conversions were observed when catalytic amounts of the Yamatomo's aluminum salt were used for the reaction of 37, only 5 mol % of Cr(TPP)(OTf)33e was needed to drive this reaction to completion. However, a signification amount of ketone was also obtained (aldehyde:ketone=3:1).

The previously reported problem of the subsequent vinylougous Mukaiyama aldol reaction has also been solved. The bismuth(III) triflate-catalyzed reaction between purified 38 (71% ee) and 3-methyl-2-(triisopropoxy)furan yielded 39 with only 56% conversion, 11:1 dr and 60% ee.3 We recently found that two equivalents of tin(II) triflate promoted this reaction with 83% conversion. Alcohol 39 was obtained from crude 38 as the only diastereomer in 80% isolated yield and 90% ee. For large scale reactions, we found that boron trifluoride diethyl etherate was a more economical Lewis acid. Full conversion could be obtained and no loss of ee was observed. It provided 39 in comparable yields despite having a diastereoselectivivity of only 4:1. Results from the survey of fourteen different Lewis acids can be found in the Supporting Information.

We previously used the Crabtree catalyst29b,34 to direct the hydrogenation of 39 and set the desired C-25 configuration of 40 with moderate diastereoselectivity (dr 6:1). We later found that 40 could be obtained as the only diastereomer by conjugate reduction with L-Selectride. Overall, these new protocols are much more cost-effective and provide significantly improved yield and stereoselectivity of the desired products.

To invert the C-22 configuration, we oxidized 40 with Dess–Martin periodinane, and reduced the resulting ketone with sodium borohydride. We then protected the C-22 alcohol as a TBS ether, selectively removed the C-21 TBS protecting group and oxidized the primary alcohol. Introduction of the C-21 gem-dichloride was achieved by reacting aldehyde 45 with Cl2/P(OPh)3.35 The hydrazone method developed by Myers36 was not compatible with the other functional groups of 45. The relative and absolute stereochemistry of 46 was determined by single crystal X-ray analysis after TBS deprotection.11 The synthesis of the nucleophilic coupling component 47 was concluded by a palladium-catalyzed stannylation of 46. Despite of the high catalyst loading and moderate yield, this protocol continues to be the best conditions for the introduction of the trimethylstannane to 47.

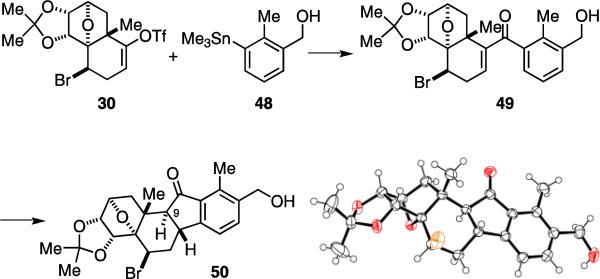

After establishing the routes to both cross-coupling fragments, our next goal was to realize the carbonylative coupling and Nazarov cyclization strategy to assemble the C-ring of 1 and 2. We used several model systems carrying a simplified side-chain on the E-ring to study these two key reactions. We found that the carbonylative coupling of 30 and 48 could be achieved with a modified Stille's protocol to afford 49.16 After an extensive survey of the reaction conditions, we conclude that Pd(PPh3)4 is the best promoter, copper(I) chloride additive37 is crucial and DMSO is the ideal solvent for this reaction. The use of catalytic amounts of Pd(PPh3)4 gave only small amounts of the desired product. No reaction occurred when using Pd(OAc)2 in combination with AsPh3, P(furyl)3, PCy3 and P(t-Bu)3 under otherwise identical conditions. The use of Pd(OAc)2/P(OMe)3 led mainly to decomposition. It is also worth noting that 49 was highly sensitive to both acids and bases. Addition of lithium chloride, prolonged heating and employment of base-promoted carbonylative Suzuki coupling protocols led to the elimination of the bromine atom.

The sensitive nature and aromaticity of 49 made the implementation of the Nazarov cyclization strategy challenging. Normally, the Lewis acid-promoted Nazarov cyclization of aryl vinyl ketones requires harsh reaction conditions or activated substrates.22 Indeed, exposure of 49 to various Lewis acids only resulted in substrate decomposition. However, we found that irradiation of a solution of 49 in acetonitrile at 350 nm readily delivered the desired annulation product 50 in its enol form, which tautomerized to the ketone form as a 1:1 mixture of C-9 diastereomers upon addition of ammonium chloride. Treating this mixture with diisopropylamine in warm methanol gave the desired diastereomer 50, the structure of which was confirmed by X-ray analysis.11 The reaction can also be carried out in methanol to directly give the C-9 diastereomeric mixture of 50 with slightly lower yield. The photo-Nazarov cyclization reaction of aryl vinyl ketones was first reported by Smith and Agosta.23c Subsequent mechanistic studies by Leitich and Schaffner revealed the reaction mechanism to be a thermal electrocyclization induced by photolytic enone isomerization.23d,e The mildness of the reaction conditions and the selective activation of the enone functional group was key to the success of this reaction.

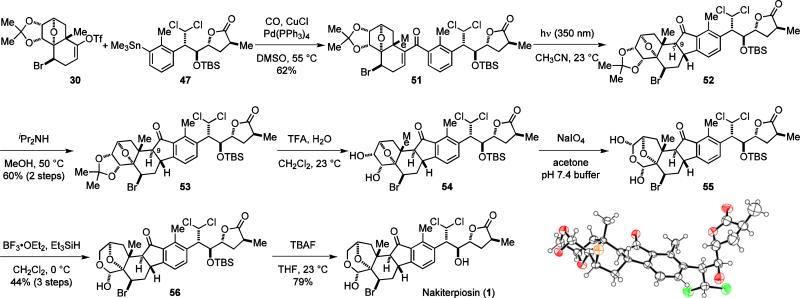

To complete the synthesis of 1, we carried out the carbonylative coupling of 30 and 47 under the optimized conditions to give 51, which was effectively transformed to 53 upon photolysis and C-9 epimerization (Scheme 4). The previous stereochemical issues of 51 are now solved (99.5% ee and dr 10:1) because 47 could be prepared with high enantiomeric purity.

Scheme 4.

Completion of the synthesis of nakiterpiosin (1).

With the central C-ring in place, the remaining task was to assemble the A-ring of 1. We first removed the acetonide protecting group of 53 and cleaved the diol of 54 to afford bis-hemiacetal 55. Selective reduction of the less hindered hemiacetal of 55 followed by TBS deprotection38 concluded the synthesis of 1. A single crystal suitable for X-ray analysis11 was recently obtained by evaporating the solvent from a 30% ethyl acetate/hexanes solution of 1, allowing unambiguous determination of its relative and absolute configuration.

To confirm our proposal for the structure revision of 1, we compared the 1H and 13C NMR spectra of our synthetic 1 with those of the natural product.2 We were pleased to find that the difference in chemical shift for all peaks was within 0.03 ppm for the 1H and 0.2 ppm for the 13C signals, and the splitting pattern for all 1H signals was also consistent with those of the natural product. While the optical rotation of the natural product was not reported, the Mosher esters analysis of our synthetic 1 was consistent with the reported data of the natural product. The ΔδSR of H-4 was found to be +0.03 ppm in the 4-Mosher ester of 1, compared to +0.04 ppm for that of H-4 in the 4,22-di-Mosher ester of the natural product. We have also determined that nakiterpiosin (1) was levorotatory in methanol with [α]20D –33° (c 0.067, MeOH).

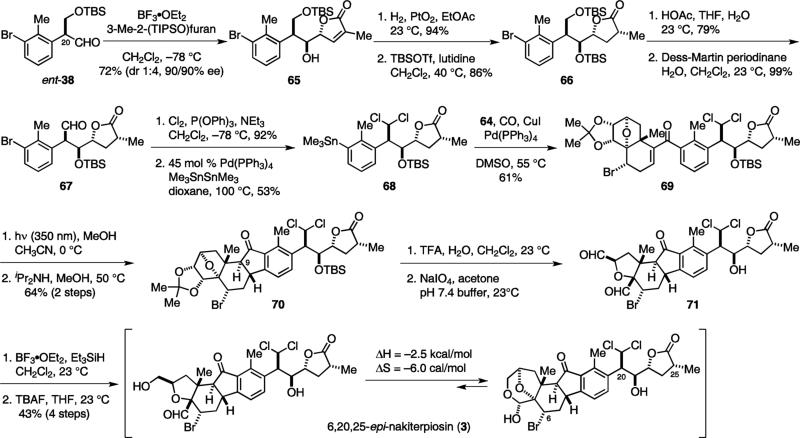

The second generation synthesis of nakiterpiosin

While the sequence shown in Scheme 4 successfully delivered 1, it required a further six steps after the convergent fragment coupling reaction. We anticipated that all the functional groups of 1 could tolerate the carbonylative coupling and photo-Nazarov cyclization reactions. We therefore decided to perform the C-ring construction on a fully elaborated system to improve the overall efficiency of the synthesis of 1 (Scheme 5).

Scheme 5.

An improved synthesis of nakiterpiosin (1).

Taking ketone 29, we introduced the A-ring functionality using the chemistry previously described to generate 10. We then protected the hemi-acetal and installed the triflate to give 57. We also removed the TBS protecting group of 47 prior to the carbonylative coupling. Pleasingly, the fragment coupling and photo-Nazarov cyclization proceeded in good yields. Subsequent TES deprotection provided 1 with significantly improved efficiency. However, it was unfortunate that photolysis of des-TES-58 resulted in significant amounts of decomposition.

Synthesis of 6,20,25-epi-nakiterpiosin

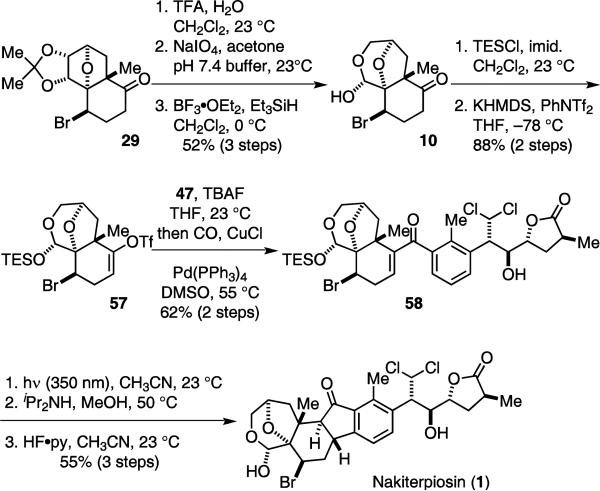

To unambiguously determine the relative stereochemistry of nakiterpiosin, we also synthesized its originally proposed structure (6,20,25-epi-nakiterpiosin, 3) and compared the NMR spectra of 3 with the natural product. Several approaches were explored in an attempt to introduce the C-6 bromine atom. We first sought to use the C-6 bromine atom as the stereochemical controlling element for the intramolecular Diels–Alder reaction and set its equatorial configuration. However, nucleophilic substitution of the C-6 hydroxyl group of 24 under various conditions failed to deliver the desired product. The use of a chelating leaving group39 did not result in retention of configuration and an SN2 instead of SNi reaction occurred. Equally fruitless was the effort to replace the hydroxyl group of 26 or its derivatives with a bromine atom through radical chemistry. Eventually, we found that the desired C-6 configuration could be set through isomerization of vinyl bromide 62 (Scheme 6).

Scheme 6.

Synthesis of 64 (6-epi-30).

Starting from 26, the olefin was first dihydroxylated and the resulting diol was protected as an acetonide. The C-6 hydroxyl group of 59 was then protected and the ketone group reduced to afford 60. Subsequent TBS protection, TES deprotection and alcohol oxidation provided 61. The vinyl bromide was then introduced by the Barton–Myers method to give 62.36,40 Removal of the TBS protecting group and alcohol oxidation under Dess-Martin conditions induced olefin isomerization to yield enone 63. Finally, conjugate reduction yielded a crystalline ketone, allowing unambiguous assignment of the C-6 configuration.11 Conversion of the ketone to enol triflate furnished the electrophilic coupling component 64 (6-epi-30).

To set the syn-anti-cis configuration of the side-chain, an anti selective vinylogous aldol reaction was need. Despite the fact that efforts to reverse the syn selectivity failed, we found that a useful amount of the desired diastereomer could be obtained with Lewis acids boron trifluoride diethyl etherate, zirconium(IV) chloride, ytterbium(III) triflate or scandium(III) triflate.11 Reaction of ent-38 and 3-methyl-2-(triisopropoxy)furan gave syn-anti-65 as the minor diastereomer (syn-syn:syn-anti=4:1). The C-25 configuration was then set by catalytic hydrogenation using Adams’ catalyst without debromination. Protection of the alcohol as a TBS ether gave the desired syn-anti-cis-66.

Following the protocols previously described for the synthesis of 47, the gem-dichloromethyl and stannyl groups were then introduced to provide 68. The relative stereochemistry of 68 was confirmed by X-ray analysis on a racemic sample after removal of the TBS protecting group.11 Its carbonylative coupling with 64 and the subsequent photolysis reaction proceeded uneventfully to yield 70. Interestingly, cleavage of the diol gave 71 as a bis-aldehyde instead of bis-acetonide. Nevertheless, reduction of 71 with Et3SiH in the presence of BF3•OEt2 induced the acetal formation. After TBS deprotection, 6,20,25-epi-nakiterpiosin (3) was obtained as an equilibrium mixture of the C-4 aldehyde and hemiacetal forms. Through variable-temperature NMR experiments, we determined the ΔH and ΔS of this equilibrium to be –2.5 kcal/mol and –6.0 cal/mol respectively.11 By comparing the 1H and 13C NMR spectra of 1, 3 and the natural product,2 we confirmed that the structure of nakiterpiosin should be 1 instead of 3 (Tables 5, Figures 6 and Figure 7).

Table 5.

Selected 1H NMR chemical shifts and coupling constants of nakiterpiosin.

| natural sample* | synthetic 1† | synthetic 3‡ | natural sample* | synthetic 1† | synthetic 3‡ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 4.70 (dd) | 4.71 (dd) | 4.74 (dd) | 21 | 6.32 (d) | 6.32 (d) | 6.66 (d) |

| J = 2.7, 1.4 Hz | J = 3.4, 2.5 Hz | J = 12.3, 5.1 Hz | J = 10.3 Hz | J = 10.0 Hz | J = 3.6 Hz | ||

| 7a | 2.28 (m) | 2.29 (ddd) | 2.22 (ddd) | 22 | 4.39 (dd) | 4.41 (dd) | 4.52 (dd) |

| J = 13.7, 12.7, 3.4 Hz | J = 12.3, 12.0, 12.0 Hz | J = 8.0, 3.8 Hz | J = 7.9, 3.2 Hz | J = 10.2, 2.3 Hz | |||

| 7b | 2.74 (ddd) | 2.75 (ddd) | 2.94 (ddd) | 24a | 1.71 (ddd) | 1.72 (ddd) | 2.00 (m) |

| J = 13.4, 2.7, 1.4 Hz | J = 13.7, 2.5, 2.3 Hz | J = 12.0, 5.1, 2.7 Hz | J = 12.8, 8.4, 8.2 Hz | J = 13.2, 8.2, 8.1 Hz | |||

| 8 | 3.58 (m) | 3.55 (ddd) | 3.03 (ddd) | 24b | 2.28 (m) | 2.29 (ddd) | 2.00 (m) |

| J = 12.7, 9.4, 2.3 Hz | J = 12.0, 9.1, 2.7 Hz | J = 13.2, 4.8, 3.9 Hz |

Recorded at 800 MHz as reported by Uemura et al. (Ref 2).

Recorded at 600 MHz.

Recorded at 500 MHz.

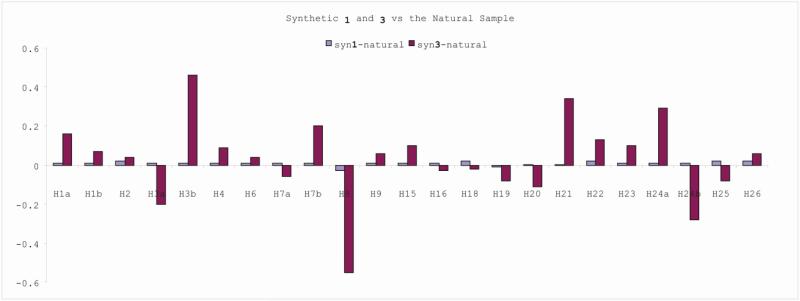

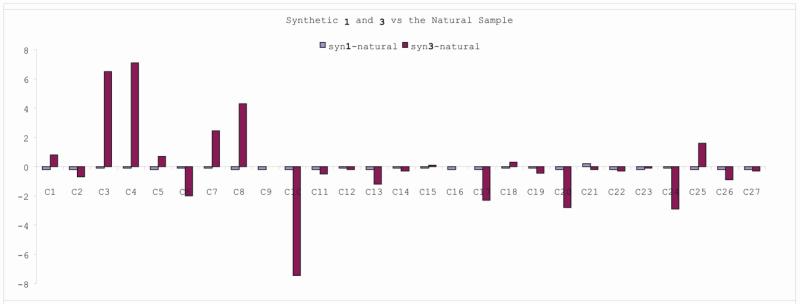

Figure 6.

Difference in the chemical shifts of the 1H NMR spectra of 1, 3 and the natural product.

Figure 7.

Difference in the chemical shifts of the 13C NMR spectra of 1, 3 and the natural product.

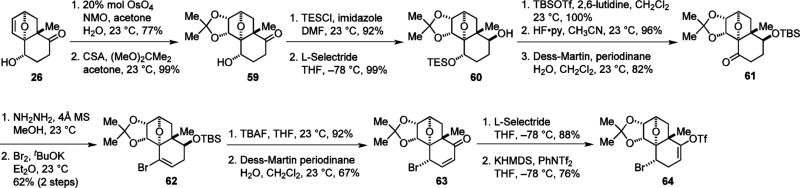

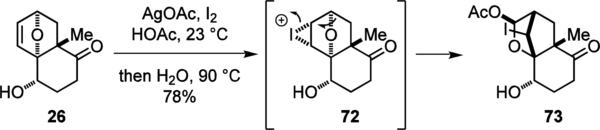

Synthesis of nakiterpiosinone

After completion of the synthesis of nakiterpiosin (1), we turned our attention to the related steroid nakiterpiosinone (2). Initially, we planned to selectively oxidize the C-4 hydroxyl group of diol 28 or 54 to accomplish this goal. However, we encountered considerable difficulties in utilizing this strategy to synthesize 2. First, despite being able to selectively protect the C-3 hydroxyl group and oxidize the C-4 hydroxyl group of 28, we were not able to perform C-3 epimerization without considerable decomposition. Next, our attempts to introduce a C-3 hydroxyl group to the more hindered β-face of 26 by Prévost–Woodward dihydroxylation41 was complicated by the Wagner-Meerwein rearrangement of the [2.2.1] bicyclic system (Scheme 8).42,43 Equally unsuccessful was the oxidation of diol 28 to diketone due to diol cleavage or decomposition.44 We therefore sought to install the C-3 stereocenter by an alternative approach.

Scheme 8.

Rearrangement of the [2.2.1] bicyclic system.

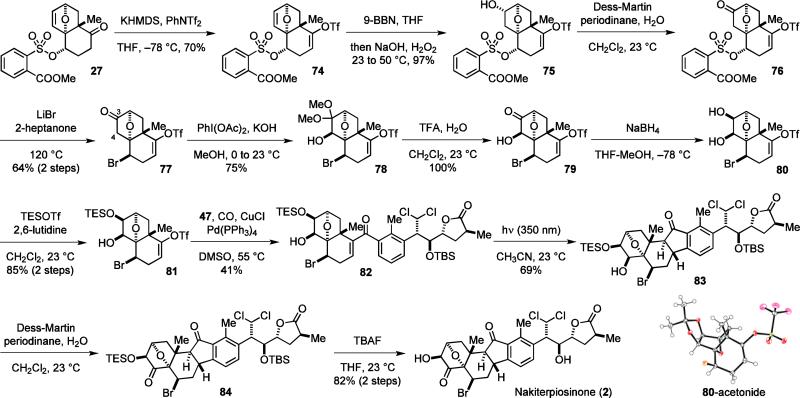

Since the β-face of the A-ring of 2 is significantly less hindered than its α-face, we decided to set the desired C-3 stereochemistry by reduction of the corresponding ketone (Scheme 9). Starting from 27, the enol triflate was first installed and the olefin of 74 was hydroborylated with 9-BBN to afford alcohol 75 as the only regioisomer after oxidative cleavage of the borane. Subsequently, the alcohol was oxidized to the ketone and the bromine atom was introduced. The nucleophilic bromination reaction of 76 was much more difficult than 28. Nevertheless, 77 could be obtained in good yield when reacting 76 with lithium bromide in 2-heptanone at 120 °C.

Scheme 9.

Synthesis of nakiterpiosinone (2).

We next found α-oxidation of ketone 77 to be particularly challenging. Oxidation by the Rubottom method, Davis reagent or selenium(IV) oxide was unsuccessful.45 However, reaction of 77 with PhI(OAc)2 under basic conditions gave 78 in good yield.46 While oxidation of the C-4 ketone regioisomer of 77 may deliver the desired protected hydroxyketone directly, we found that hydroborylation of 74 with the complementary regioselectivity did not proceeded with good efficiency. Deprotection of the dimethyl acetal of 78, and subsequent reduction of the resulting ketone (79) gave cis-diol 80 with the desired C-3 configuration. The structure of 80 was confirmed by analyzing its acetonide derivative by X-ray. Selective protection of the C-3 hydroxyl group of 80 afforded the electrophilic coupling component 81. Carbonylative coupling of 81 with 47 and the following photo-Nazarov cyclization proceeded smoothly to give 83. Interestingly, ketone 83 with the desired 9S configuration was obtained directly as the only diastereomer. Finally, oxidation of the hydroxyl group and removal of the TES and TBS protecting groups concluded the synthesis of 2. The 1H NMR spectrum of 2 agreed with that of the natural product,2b,11 confirming the structure of nakiterpiosinone to be 2.

Biological studies of nakiterpiosin

Uemura and co-workers initially reported that nakiterpiosin (1) and nakiterpiosinone (2) inhibited the growth of P388 mouse leukemia cells with an IC50 of 10 ng/mL.2 However, the limited amount of material that can be isolated from the sponge has hampered further efforts to investigate the anti-cancer potential of these compounds. Having resolved the re-supply issue through total synthesis, we are now pursuing further mechanistic studies focused on the anti-cell proliferative properties associated with 1.

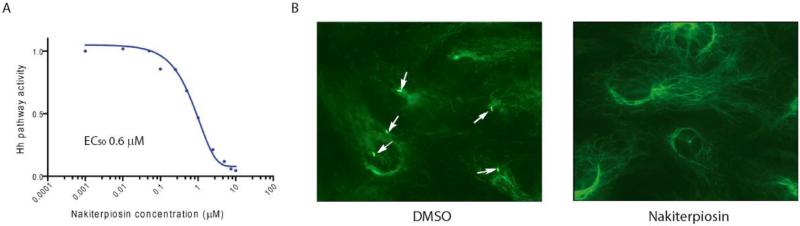

The steroid skeleton of 1 is related to that of cyclopamine (5), a potent Hedgehog (Hh) pathway antagonist. Cyclopamine (5) inhibits Hh signaling by influencing the movement of Smoothened (Smo),5a–c a seven-pass transmembrane protein, in and out of the primary cilium.,5d,e The primary cilium is a microtubule-based assembly point organelle for Hh pathway components.47 Indeed, 1 suppressed Hh signaling at sub-micromolar concentrations in NIH3T3 mouse fibroblasts (Figure 8A). Surprisingly, as part of our efforts to evaluate the effects of 1 on the movement of Smo with respect to the primary cilium, we observed that cell populations treated with nakiterpoisin show a loss of the primary cilium (Figure 8B).

Figure 8.

Effects of nakiterpiosin on Hh signaling and primary cilia. (A) The Hh pathway response of Light2 cells (NIH3T3 cells with a Hh-specific firefly luciferase reporter) in the presence of nakiterpiosin. (B) NIH3T3 cells treated with nakiterpiosin showing a compromised ability to form primary cilia, as detected by anti-acetylated tubulin antibody.

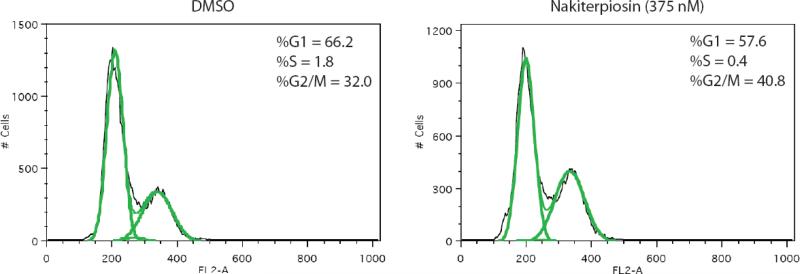

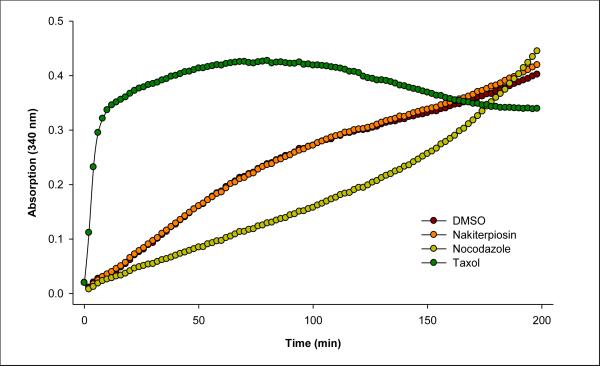

Because the formation and retraction of the primary cilium is cell cycle- and microtubule-dependent,48 we suspected 1 to be an anti-mitotic agent. Indeed, flow cytometry experiments suggested that 1 induces cell cycle arrest in the G2/M-phase (Figure 9). We first determined the cell growth IC50 of 1 in HeLa cells to be 375 nM. Subsequently, we incubated the HeLa cells with 1 at this concentration for 16 h and found the population of cells in the G2/M phase to be significantly increased as compared to the DMSO control. Since the most common mechanism for G2/M arrest is the targeting of microtubule assembly, and it was reported that JK184, a microtubule depolymerizing agent,49 effectively regulates Hh signaling, we next examined the effect of 1 on microtubule dynamics. However, we found that, in contrast to taxol and nocodazole, tubulin polymerization was not influenced in the presence of 5 μM of 1 in an in vitro assay (Figure 10). Taken together, these results suggested that 1 may be useful in tumors resistant to existing anti-mitotic chemotherapeutic agents. Lastly, given the frequency of mutations in Smo that render it resistant to Hh pathway antagonists currently under clinical development,5c considerable effort is being devoted to the identification of small molecules that act upstream or downstream of Smo.50 The ability of 1 to block Hh pathway responses suggests that it may be particularly useful against Hh-dependent tumors.

Figure 9.

The DNA profiles of nakiterpiosin treated HeLa cells.

Figure 10.

The in vitro tubulin polymerization assays.

Summary

Through extensive spectroscopic analysis and convergent total synthesis, we have established the stereochemistry of nakiterpiosin (1) and nakiterpiosinone (2). Our synthetic route provides 1 in 21 steps with 5% overall yield along the longest linear sequence. Our preliminary biological studies show that 1 is anti-mitotic and has functions distinct from those of other well-established anti-mitotic agents such as taxol. Nakiterpiosin may be an alternative chemotherapeutic against tumors resistant to anti-tubulin agents and dependent on Hh signaling.

Supplementary Material

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of the electrophilic coupling component 30.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of the nucleophilic coupling component 47.

Scheme 3.

Model studies for the carbonylative coupling/Nazarov cyclization strategy.

Scheme 7.

Synthesis of the 6,20,25-epi-nakiterpiosin (3).

Acknowledgment

Financial support are provided by the NIH (Grant NIGMS R01-GM079554 to C.C., NHLBI R01-HL089966 to L.J.H., and NIGMS R01-GM076398 to L.L.), the Welch Foundation (I-1596 to C.C.), and UT Southwestern. L.L. is a Virginia Murchison Linthicum Scholar in Medical Research and C.C. a Southwestern Medical Foundation Scholar in Biomedical Research. We thank Prof. John MacMillan and Dr. Ana Paula Espindola for assistance in NMR experiments, Dr. Vincent Lynch (UT Austin) and Dr. Radha Akella for X-ray analysis, and Dr. Michael G. Roth for helpful discussions. We also thank Prof. Daisuke Uemura (Keio University) for providing a copy of the 1H and 13C NMR spectra of the natural products.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Complete Refs. 6e and 6g, 1H and 13C NMR spectra of 2, calculation of the thermodynamic properties of 3, details of the optimization of reaction parameters, experimental procedures, crystallographic data, and characterization data. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.a Plucer-Rosario G. Coral Reefs. 1987;5:197–200. [Google Scholar]; b Rützler K, Smith KP. Sci. Mar. 1993;57:381–393. [Google Scholar]; c Rützler K, Smith KP. Sci. Mar. 1993;57:395–403. [Google Scholar]; d Liao M-H, Tang S-L, Hsu C-M, Wen K-C, Wu H, Chen W-M, Wang J-T, Meng P-J, Twan W-H, Lu C-K, Dai C-F, Soong K, Chen C-A. Zool. Stud. 2007;46:520. [Google Scholar]; e Lin W.-j., M.S. Thesis. National Sun Yat-sen University, Kaohsiung; Taiwan, R.O.C.: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.a Teruya T, Nakagawa S, Koyama T, Suenaga K, Kita M, Uemura D. Tetreahedron Lett. 2003;44:5171–5173. [Google Scholar]; b Teruya T, Nakagawa S, Koyama T, Arimoto H, Kita M, Uemura D. Tetreahedron. 2004;60:6989–6993. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gao S, Wang Q, Chen C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:1410–1412. doi: 10.1021/ja808110d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.a Binns W, James LF, Keeler RF, Balls LD. Cancer Res. 1968;28:2323–2326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Keeler RF. Lipids. 1978;13:708–715. doi: 10.1007/BF02533750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c James LF. J. Nat. Toxins. 1999;8:63–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.a Cooper MK, Porter JA, Young KE, Beachy PA. Science. 1998;280:1603–1607. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5369.1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Incardona JP, Gaffield W, Kapur RP, Roelink H. Development. 1998;125:3553–3562. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.18.3553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Chen JK, Taipale J, Cooper MK, Beachy PA. Gen. Dev. 2002;16:2743–2748. doi: 10.1101/gad.1025302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Wang Y, Zhou Z, Walsh CT, McMahon AP. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009;106:2623–2628. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812110106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Rohatgi R, Milenkovic L, Corcoran RB, Scott MP. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009;106:3196–3201. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813373106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.a Scalesa SJ, Sauvage F. J. d. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2009;30:303–312. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Epstein EH. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2008;8:743–754. doi: 10.1038/nrc2503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Rubin LL, de Sauvage FJ. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery. 2006;5:1026–1033. doi: 10.1038/nrd2086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Romer J, Curran T. Cancer Res. 2005;65:4975–4978. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Yauch RL. Science. 2009;326:572–574. doi: 10.1126/science.1179386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Yauch RL, Gould SE, Scales SJ, Tang T, Tian H, Ahn CP, Marshall D, Fu L, Januario T, Kallop D, Nannini-Pepe M, Kotkow K, Marsters JC, Rubin LL, de Sauvage FJ. Nature. 2008;455:406–410. doi: 10.1038/nature07275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Tremblay MR. J. Med. Chem. 2008;51:6646–6649. doi: 10.1021/jm8008508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.a Masamune T, Takasugi M, Murai A, Kobayashi K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1967;89:4521–4523. [Google Scholar]; b Masamune T, Takasugi M, Murai A. Tetrahedron. 1971;27:3369–3386. [Google Scholar]; c Johnson WS, deJongh HAP, Coverdale CE, Scott JW, Burckhardt U. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1967;89:4523–4524. [Google Scholar]; d Johnson WS, Cox JM, Graham DW, Whitlock HW., Jr. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1967;89:4524–4526. [Google Scholar]; e Masamune T, Mori Y, Takasugi M, Murai A, Ohuchi S, Sato N, Katsui N. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1965;38:1374–78. doi: 10.1246/bcsj.38.1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Kutney JP, Cable J, Gladstone WAF, Hanssen HW, Nair GV, Torupka EJ, Warnock WDC. Can. J. Chem. 1975;53:1796–1817. [Google Scholar]; g Giannis A, Heretsch P, Sarli V, Stößel A. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:7911–7914. doi: 10.1002/anie.200902520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.For synthetic studies of nakiterpiosin, see: Ito T, Ito M, Arimoto H, Takamura H, Uemura D. Tetrahedron. 2007;48:5465–5469.Takamura H, Yamagami Y, Ito T, Ito M, Arimoto H, Kadota I, Uemura D. Heterocycles. 2009;77:351–364.

- 9.For a review of structure revisions of natural products through synthetic studies, see: Nicolaou KC, Snyder SA. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005;44:1012–1044. doi: 10.1002/anie.200460864.

- 10.For reviews of halogenated natural product biosynthesis, see: Vaillancourt FH, Yeh E, Vosburg DA, Garneau-Tsodikova S, Walsh CT. Chem. Rev. 2006;106:3364–3378. doi: 10.1021/cr050313i.Neumann CS, Fujimori DG, Walsh CT. Chem. Biol. 2008;15:99–109. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2008.01.006.Butler A, Walker JV. Chem. Rev. 1993;93:1937–1944.

- 11.For details, see Supporting Information.

- 12.The chemical shift of H-6 in 7–10 and the residual H2O are too close in CD3OD for the accurate measurement of the coupling constants. We therefore recorded their 1H NMR spectra in CDCl3. We reasoned that the rigid polycyclic ring systems of 7–10 will adopt similar conformations as the natural products even in different solvents. Therefore, the coupling constants should not be significantly influenced by the NMR solvents.

- 13.The 13C NMR spectrum of nakiterpiosin was mis-referenced by ca. –2 ppm in the original reports. We adjusted the reported data by +2.0 ppm in this article.

- 14.For a review of palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions in natural product synthesis, see: Nicolaou KC, Bulger PG, Sarlah D. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005;44:4442–4489. doi: 10.1002/anie.200500368.

- 15.For reviews of carbonylative coupling reactions, see: Brennführer A, Neumann H, Beller M. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:4114–4133. doi: 10.1002/anie.200900013.Barnard CFJ. Organometallics. 2008;27:5402–5422.Skoda-Földes R, Kollár L. Curr. Org. Chem. 2002;6:1097–1119.Brunet J-J, Chauvin R. Chem. Soc. Rev. 1995;24:89–95.

- 16.For the development of carbonylative Stille coupling, see: Tanaka M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1979;20:2601–2602.Beletskaya IP. J. Organomet. Chem. 1983;250:551–564.Baillargeon VP, Stille JK. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1983;105:7175–7176.Sheffy FK, Godschalx JP, Stille JK. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1984;106:4833–4840.Goure WF, Wright ME, Davis PD, Labadie SS, Stille JK. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1984;106:6417–6422.Crisp GT, Scott WJ, Stille JK. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1984;106:7500–7506.Merrifield JH, Godschalx JP, Stille JK. Organometallics. 1984;3:1108–1112.Echavarrent AM, Stille JK. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988;110:1557–1565.

- 17.For further examples of carbonylative Stille coupling, see: Smith AB, III, Cho YS, Ishiyama H. Org. Lett. 2001;3:3971–3974. doi: 10.1021/ol016888t.Ceccarelli S, Piarulli U, Gennari C. J. Org. Chem. 2000;65:6254–6256. doi: 10.1021/jo0004310.Kang S-K, Ryu H-C, Lee S-W. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1. 1999:2661–2663.Xiang AX, Watson DA, Ling T, Theodorakis EA. J. Org. Chem. 1998;63:6774–6775. doi: 10.1021/jo981331l.Angle SR, Fevig JM, Knight SD, Marquis RW, Overman LE. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993:3966–3976.

- 18.For examples of carbonylative Negishi coupling, see: Wang Q, Chen C. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008;49:2916–2921.Jackson RFW, Turner D, Block MH. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1. 1997:865–870.Yasui K, Fugami K, Tanaka S, Tamaru Y. J. Org. Chem. 1995;60:1365–1380.Tamaru Y, Ochiai H, Yoshida Z.-i. Tetrahedron Lett. 1984;25:3861–3864.Tamaru Y, Ochiai H, Yamada Y, Yoshida Z.-i. Tetrahedron Lett. 1983;24:3869–3872.

- 19.For examples of carbonylative Suzuki coupling, see: O'Keefe BM, Simmons N, Martin SF. Org. Lett. 2008;10:5301–5304. doi: 10.1021/ol802202j.Dai M, Liang B, Wang C, You Z, Xiang J, Dong G, Chen J, Yang Z. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2004;346:1669–1673.Ishiyama T, Kizaki H, Hayashi T, Suzuki A, Miyaura N. J. Org. Chem. 1998;63:4726–4731.Ishikura M, Terashima M. J. Org. Chem. 1994;59:2634–2637.Suzuki A. Pure Appl. Chem. 1994;66:213–222.Kondo T, Tsuji Y, Watanabe Y. J. Organomet. Chem. 1988;345:397–403.Wakita Y, Yasunaga T, Akita M, Kojima M. J. Organomet. Chem. 1986;301:C17–C20.

- 20.For examples of other types of carbonylative coupling reactions, see: Myeong SK, Sawa Y, Ryang M, Tsutsumi S. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1965;38:330–331.Heck RF. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1968;90:5546–5548.Yamamoto T, Kohara T, Yamamoto A. Chem. Lett. 1976:1217–1220.Kobayashi T, Tanaka M. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1981:333–334.Rour JM, Negishi E.-i. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1985;107:8289–8291.Hatanaka Y, Fukushima S, Hiyama T. Tetrahedron. 1992;48:2113–2126.Satoh T, Itaya T, Okuro K, Miura M, Nomura M. J. Org. Chem. 1995;60:7267–7271.Gagnier SV, Larock RC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:4804–4807. doi: 10.1021/ja0212009.Lee PH, Lee SW, Lee K. Org. Lett. 2003;5:1103–1106. doi: 10.1021/ol034167j.Ahmed MSM, Mori A. Org. Lett. 2003;5:3057–3060. doi: 10.1021/ol035007a.Behenna DC, Stockdill JL, Stoltz BM. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:4077–4080. doi: 10.1002/anie.200700430.Neumann H, Sergeev A, Beller M. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:4887–4891. doi: 10.1002/anie.200800994.

- 21.For reviews of Nazarov cyclization reactions, see: Frontier AJ, Collison C. Tetrahedron. 2005;61:7577–7606.Pellissier H. Tetrahedron. 2005;61:6479–6517.Tius MA. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2005:2193–2206.Habermas KL, Denmark SE, Jones TK. Org. React. 1994;45:1–158.

- 22.For examples of Nazarov cyclization of vinyl aryl ketones, see: Marcus AP, Lee AS, Davis RL, Tantillo DJ, Sarpong R. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:6379–6383. doi: 10.1002/anie.200801542.He W, Herrick IR, Atesin TA, Caruana PA, Kellenberger CA, Frontier AJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:1003–1011. doi: 10.1021/ja077162g.Liang G, Xu Y, Seiple IB, Trauner D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:11022–11023. doi: 10.1021/ja062505g.

- 23.For the development of photo-Nazarov cyclization reactions, see: Crandall JK, Haseltine RP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1968;90:6251–6253.Noyori R, Katô M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1968;9:5075–5077.Smith AB, III, Agosta WC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1973;95:1961–1968.Leitich J, Heise I, Werner S, Krüger C, Schaffner K. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A: Chem. 1991;57:127–151.Leitich J, Heise I, Rust J, Schaffner K. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2001:2719–2726.

- 24.For reviews of transition metal-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions, see: Molander GA, Ellis N. Acc. Chem. Res. 2007;40:275–286. doi: 10.1021/ar050199q.Frisch AC, Beller M. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005;44:674–688. doi: 10.1002/anie.200461432.Netherton MR, Fu GC. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2004;346:1525–1532.Cárdenas D. J. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2003;42:384–387. doi: 10.1002/anie.200390123.Littke AF, Fu GC. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002;41:4176–4211. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20021115)41:22<4176::AID-ANIE4176>3.0.CO;2-U.Luh T-Y, Leung M.-k., Wong K-T. Chem. Rev. 2000;100:3187–3204. doi: 10.1021/cr990272o.

- 25.For reviews of transition metal-catalyzed C–H activation reactions, see: Chen X, Engle KM, Wang D-H, Yu J-Q. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:5094–5115. doi: 10.1002/anie.200806273.Li C-J. Acc. Chem. Res. 2009;42:335–344. doi: 10.1021/ar800164n.Lewis JC, Bergman RG, Ellman JA. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008;41:1013–1025. doi: 10.1021/ar800042p.Park YJ, Park J-W, Jun C-H. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008;41:222–234. doi: 10.1021/ar700133y.Alberico D, Scott ME, Lautens M. Chem. Rev. 2007;107:174–238. doi: 10.1021/cr0509760.Seregin IV, Gevorgyan V. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2007;36:1173–1193. doi: 10.1039/b606984n.Yu J-Q, Giri R, Chen X. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2006;4:4041–4047. doi: 10.1039/b611094k.Dick AR, Sanford MS. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:2439–2463.Daugulis O, Zaitsev VG, Shabashov D, Pham Q-N, Lazareva A. Synlett. 2006:3382–3388.Goj LA, Gunnoe TB. Curr. Org. Chem. 2005;9:671–685.Ritleng V, Sirlin C, Pfeffer M. Chem. Rev. 2002;102:1731–1769. doi: 10.1021/cr0104330.Dyker G. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1999;38:1698–1712. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19990614)38:12<1698::AID-ANIE1698>3.0.CO;2-6.

- 26.For reviews, see: Takao K.-i., Munakata R, Tadano K.-i. Chem. Rev. 2005;105:4779–4807. doi: 10.1021/cr040632u.Keay BA, Hunt IR. Adv. Cycloaddit. 1999;6:173–210.Roush WR. In: Advances in Cycloaddition. Curran DP, editor. Vol. 1992. Jai Press; Greenwich: 1990. pp. 1991–1146.Craig D. Chem. Soc. Rev. 1987;16:187–238.

- 27.For the development of tether-controlled diastereoselective intramolecular Diels–Alder reactions, see: Roush WR. J. Org. Chem. 1979;44:4008–4010.Roush WR, Hall SE. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1981;103:5200–5211.Roush WR, Kageyama M, Riva R, Brown BB, Warmus JS, Moriarty KJ. J. Org. Chem. 1991;56:1192–1210.Taber DF, Gunn BP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1979;101:3992–3993.Taber DF, Saleh SA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1980;102:5085–5088.Boeckman RK, Jr., Napier JJ, Thomas EW, Sato RI. J. Org. Chem. 1983;48:4152–4154.Boeckman RK, Jr., Barta TE. J. Org. Chem. 1985;50:3421–3423.

- 28.For reviews, see: Brodmann T, Lorenz M, Schäckel R, Simsek S, Kalesse M. Synlett. 2009:174–192.Hosokawa S, Tatsuta K. Mini-Rev. Org. Chem. 2008;5:1–18.Denmark SE, Heemstra J, John R, Beutner GL. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005;44:4682–4698. doi: 10.1002/anie.200462338.Casiraghi G, Zanardi F, Appendino G, Rassu G. Chem. Rev. 2000;100:1929–1972. doi: 10.1021/cr990247i.Rassu G, Zanardi F, Battistinib L, Casiraghi G. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2000;29:109–118.

- 29.For examples of the vinylogous Mukaiyama aldol reaction of 2-siloxyfuran, see: Ollevier T, Bouchard J-E, Desyroy V. J. Org. Chem. 2008;73:331–334. doi: 10.1021/jo702085p.Evans DA, Dunn TB, Kværø L, Beauchemin A, Raymer B, Olhava EJ, Mulder JA, Juhl M, Kagechika K, Favor DA. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:4698–4703. doi: 10.1002/anie.200701520.López CS, Álvarez R, Vaz B, Faza ON, Lera Á. R. d. J. Org. Chem. 2005;70:3654–3659. doi: 10.1021/jo0501339.Kong K, Romo D. Org. Lett. 2006;8:2909–2912. doi: 10.1021/ol060534q.Evans DA, Kozlowski MC, Murry JA, Burgey CS, Campos KR, Connell BT, Staples RJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:669–685.Evans DA, Burgey CS, Kozlowski MC, Tregay SW. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:686–699.Casiraghi G, Colombo L, Rassu G, Spanu P. J. Org. Chem. 1991;56:6523–6527.Rassu G, Spanu P, Casiraghi G, Pinna L. Tetrahedron. 1991;47:8025–8030.Jefford CW, Jaggi D, Boukouvalas J. Tetrahedron Lett. 1987;28:4037–4040.

- 30.a Hashiguchi S, Fujii A, Takehara J, Ikariya T, Noyori R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:7562–7563. [Google Scholar]; b Fujii A, Hashiguchi S, Uematsu N, Ikariya T, Noyori R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:2521–2522. [Google Scholar]; c Wu X, Li X, Hems W, King F, Xiao J. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2004;2:1818–1821. doi: 10.1039/b403627a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Wu X, Li X, King F, Xiao J. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005;44:3407–3411. doi: 10.1002/anie.200500023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Ohkuma T, Utsumi N, Tsutsumi K, Murata K, Sandoval C, Noyori R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:8724–8725. doi: 10.1021/ja0620989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.a Katsuki T, Sharpless KB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1980;102:5974–5976. [Google Scholar]; b Gao Y, Klunder JM, Hanson RM, Masamune H, Ko SY, Sharpless KB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987;109:5765–5780. [Google Scholar]; c Katsuki T, Martin VS. Org. React. 1996;48:1–300. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen L, Yin B.-l., Xu H.-h., Chiu M.-h., Wu Y.-l. Chin. J. Chem. 2004;22:92–99. [Google Scholar]

- 33.a Maruoka K, Ooi T, Yamamoto H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989;111:6431–6432. [Google Scholar]; b Maruoka K, Ooi T, Nagahara S, Yamamoto H. Tetrahedron. 1991;47:6983–6998. [Google Scholar]; c Maruoka K, Ooi T, Yamamoto H. Tetrahedron. 1992;48:3303–3312. [Google Scholar]; d Maruoka K, Murase N, Bureau R, Ooi T, Yamamoto H. Tetrahedron. 1994;50:3663–3672. [Google Scholar]; e Suda K, Kikkawa T, Nakajima S.-i., Takanami T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:9554–9555. doi: 10.1021/ja047104k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.a Crabtree R. Acc. Chem. Res. 1979;12:331–337. [Google Scholar]; b Crabtree RH, Davis MW. Organometallics. 1983;2:681–682. [Google Scholar]

- 35.a Spaggiari A, Vaccari D, Davoli P, Torre G, Prati F. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:2216–2219. doi: 10.1021/jo061346g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Hoffmann RW, Bovicelli P. Synthesis. 1990:657–659. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Furrow ME, Myers AG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004:5436–5445. doi: 10.1021/ja049694s. For an example of the use of the original Barton-Pross-Sternhell protocol, see: Kropp PJ, Pienta NJ. J. Org. Chem. 1983;48:2084–2090.

- 37.a Han X, Stoltz BM, Corey EJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:7600–7605. [Google Scholar]; b Farina V, Kapadia S, Krishnan B, Wang C, Liebeskind LS. J. Org. Chem. 1994;59:5905–5911. [Google Scholar]; c Liebeskind LS, Fengl RW. J. Org. Chem. 1990;55:5359–5364. [Google Scholar]; d Marino JP, Long JK. J. Org. Chem. 1988;110:7916–7917. [Google Scholar]

- 38.For a convenient workup method, see: Kaburagi Y, Kishi Y. Org. Lett. 2007;9:723–726. doi: 10.1021/ol063113h.

- 39.a Lepore SD, Mondal D. Tetrahedron. 2007;63:5103–5122. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2007.03.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Braddock DC, Pouwer RH, Burton JW, Broadwith P. J. Org. Chem. 2009;74:6042–6049. doi: 10.1021/jo900991z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barton DHR, O'Brien RE, Sternhell S. J. Chem. Soc. 1962:470–476. [Google Scholar]

- 41.a Emmanuvel L, Shaikh TMA, Sudalai A. Org. Lett. 2005;7:5071–5074. doi: 10.1021/ol052080n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Woodward RB, Brutcher FV., Jr. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1958;80:209–211. [Google Scholar]

- 42.a Winstein S, Trifan DS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1949;71:2953. [Google Scholar]; b Winstein S, Trifan DS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1952;74:1147–1154. [Google Scholar]; c Winstein S, Trifan DS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1952;74:1154–1160. [Google Scholar]; d Winstein S, Clippinger E, Howe R, Vogelfanger E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1965;87:376–377. [Google Scholar]; e Keay BA, Rogers C, Bontront J-L. J. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1989:1782–1784. [Google Scholar]

- 43.a Grob CA. Acc. Chem. Res. 1983;16:426–431. [Google Scholar]; b Brown HC. Acc. Chem. Res. 1983;16:432–440. [Google Scholar]; c Olah GA, Prakash GKS, Saunders M. Acc. Chem. Res. 1983;16:440–448. [Google Scholar]; d Walling C. Acc. Chem. Res. 1983;16:448–454. [Google Scholar]

- 44.a Burns NZ, Baran PS. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:205–208. doi: 10.1002/anie.200704576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Moorthy JN, Singhal N, Senapati K. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2007;5:767–771. doi: 10.1039/b618135j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.a Rubottom GM, Vazquez MA, Pelegrina DR. Tetrahedron Lett. 1974;15:4319–4322. [Google Scholar]; b Hassner A, Reuss RH, Pinnick HW. J. Org. Chem. 1975;40:3427–3429. [Google Scholar]; c Davis FA, Chen BC. Chem. Rev. 1992;92:919–934. [Google Scholar]; d Ruano JLG, Alemán J, Fajardo C, Parra A. Org. Lett. 2005;7:5493–5496. doi: 10.1021/ol052250w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e White JD, Wardrop DJ, Sundermann KF. Org. Syn. 2002;79:125–129. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moriarty RM, Prakash O. Acc. Chem. Res. 1986;19:244–250. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Eggenschwiler JT, Anderson KV. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2007;23:345–373. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.23.090506.123249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.a Quarmby LM, Parker JDK. J Cell Biol. 2005;169:707–710. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200503053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Rieder CL, Jensen CG, Jensen LC. J. Ultrastruct. Res. 1979;68:173–185. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5320(79)90152-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cupido T, Rack PG, Firestone AJ, Hyman JM, Han K, Sinha S, Ocasio CA, Chen JK. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:2321–2324. doi: 10.1002/anie.200805666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hyman JM, Firestone AJ, Heine VM, Zhao Y, Ocasio CA, Han K, Sun M, Rack PG, Sinha S, Wu JJ, Solow-Cordero DE, Jiang J, Rowitch DH, Chen JK. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009;106:14132–14137. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907134106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.