Abstract

While the demand for continuing care services in Canada grows, the quality of such services has come under increasing scrutiny. Consideration has been given to the use of public reporting of quality data as a mechanism to stimulate quality improvement and promote public accountability for and transparency in service quality. The recent adoption of the Resident Assessment Instrument (RAI) throughout a number of Canadian jurisdictions means that standardized quality data are available for comparisons among facilities across regions, provinces and nationally. In this paper, we explore current knowledge on public reporting in nursing homes in the United States to identify what lessons may inform policy discussion regarding potential use of public reporting in Canada. Based on these findings, we make recommendations regarding how public reporting should be progressed and managed if Canadian jurisdictions were to implement this strategy.

Abstract

Alors qu'au Canada, la demande pour les services de soins de longue durée connaît une augmentation, la qualité de tels services est de plus en plus examinée en profondeur. L'emploi de la diffusion publique des données sur la qualité a été proposé comme moyen de stimuler l'amélioration de la qualité et de favoriser la transparence et l'obligation publique de rendre des comptes en matière de qualité des services. L'adoption récente de l'instrument d'évaluation du pensionnaire (IEP) par de nombreuses administrations canadiennes implique l'existence de données normalisées sur la qualité, qui peuvent permettre d'effectuer des comparaisons entre établissements aux niveaux régional, provincial et national. Dans cet article, nous examinons les connaissances actuelles sur la diffusion publique d'information des maisons de soins infirmiers aux États-Unis et nous dégageons les leçons qui peuvent éclairer la discussion politique quant à l'utilisation éventuelle d'une telle diffusion au Canada. À partir de ces résultats, nous proposons des recommandations quant au développement et à la gestion de la diffusion publique d'information pour les administrations canadiennes qui souhaitent mettre en place une telle stratégie.

Concern about the quality of care in Ontario's long-term care facilities has received wide news coverage across Canada, and a recent national report documents substandard quality of care (National Advisory Council on Aging 2005). In Alberta, reports of inferior-quality care (Health Quality Council of Alberta 2008; Auditor General Alberta 2005) and a series of tragic injuries and deaths in long-term care facilities have led to the promulgation of new standards by government agencies. In the United States, long-standing concerns about abysmal conditions in long-term care facilities led to sweeping reforms in the late 1980s and since, including mandatory standardized resident assessment and reporting to the federal government on resident care.

The need for continuing care services in Canada is steadily increasing (Statistics Canada 2005). In 2006, the age of 13.7% of Canadians was 65 or greater (Statistics Canada 2006); by 2011 this figure is projected to rise to 14.4% and by 2031, 23.4% of the population is expected to be 65 years or over (Statistics Canada 2005). In Canada, the term “continuing care” refers to the full continuum of chronic care services (known in the United States as the long-term care continuum). Long-term care facilities are nursing homes, although they can also include auxiliary hospitals that function as residential chronic care facilities. Between 2001 and 2011, an estimated 370,849 Canadian seniors will spend some time in a continuing care setting (Statistics Canada 2001). While the need for these services is increasing, the sector is currently facing numerous staffing and resource challenges. For example, 70% of the continuing care workforce has little or no formal education (Auditor General Alberta 2005), although the complexity of care required by residents continues to increase. While attempting to address these challenges, continuing care providers also need to begin exploring new mechanisms to stimulate and encourage continuous quality improvement within facilities to ensure that residents receive the highest quality of care possible.

In Canada, public reporting of quality indicator data is currently being explored as a method of stimulating quality improvement in the healthcare sector. The United States has adopted public reporting in some sectors, including hospitals through the Joint Commission, to help provide accountability, stimulate quality improvement and encourage consumer choice (Mukamel et al. 2007; Marshall et al. 2000). This strategy is based on the assumption that public reporting will promote transparency by informing consumers about the quality of care provided in individual facilities, thereby allowing them to be more involved in their healthcare decisions and at the same time increase accountability and improve performance in the healthcare system (Schauffler and Mordavsky 2001; Marshall et al. 2000). With a largely private healthcare system in the United States, there is also the assumption that public reporting will contribute to competition among healthcare facilities, forcing them to compete on quality in order to attract the largest number of consumers (Stevenson 2006; Mor 2005).

All US nursing homes that accept Medicare and Medicaid funding must publicly report their data through the Nursing Home Compare (NHC) website (http://www.medicare.gov/NHCompare). This website contains information on nursing home characteristics, quality measures and inspection results and makes information accessible to providers so that they can identify potential quality concerns and improve care processes (Harris and Clauser 2002). The NHC website was developed through a series of events related to the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (OBRA) of 1987. This Act mandated the implementation of the Resident Assessment Instrument (RAI) Minimum Data Set (MDS), a standardized assessment tool developed by interRAI, an international research collaborative, to capture essential information about the health, cognitive, sensory, functional and physical status of nursing home residents. The MDS was initially intended for use as a care planning tool but has since been adopted as the basis for a prospective payment system and a research and policy development tool, and is the foundation for the development of quality indicators (Harris and Clauser 2002). In 1998, the Centres for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) launched the NHC website. At that time, the website posted deficiency citations and later expanded to include information on resident characteristics, nursing staff levels and complaint investigation data. The website has since evolved to include information on 14 long-stay and five short-stay quality measures derived using the MDS data.

In addition to NHC, some US states have designed and maintained state nursing home websites. The websites vary in the type and amount of information that is included, with most sites including a link to the NHC website. Some sites include additional information, such as the name of the administrator at each facility, while other states need to invest more resources into their sites to ensure comprehensive and accurate information is reported (Harrington et al. 2003).

Despite recent efforts to improve quality of care, quality concerns remain prevalent in the continuing care sector in both Canada and the United States. Supporters of public reporting believe that issuing public report cards for continuing care facilities will help improve the overall quality of care. However, nursing homes may defy the standard assumption that public reporting will stimulate competition, and that a reported decrease in quality will result in a decrease in business (Grabowski and Castle 2004). This assumption holds only if supply and demand are balanced, or there is an excess supply of nursing home beds, and if consumers have the option of exercising choice about which nursing home they enter. Later in this paper, we will discuss ways in which this model may fail.

In Canada, transparency in publicly funded healthcare and a growing demand for greater public accountability are two motivating factors supporting public reporting (CHSRF 2007). The Romanow report stated that transparency in provision of care is an important expectation of healthcare organizations (Health Quality Council 2006). Some public reporting is currently being conducted by the provincial and federal governments, advocacy groups, independent agencies and arms-length agencies established by governments (CHSRF 2007). In Ontario, the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (2009) publicly reports information on Ontario's long-term care facilities. The ministry's website allows consumers to compare up to four facilities while looking at the number of citations and unmet standards at each facility, as well as the provincial averages. Although the information is not kept up to date, relevant dates appear on the website. There are also agencies in Canada, such as the Health Quality Council of Saskatchewan and of Alberta, that are independent organizations with legislated mandates to report publicly on quality of care (Health Quality Council 2006). Although forms of public reporting do exist for healthcare in Canada, currently there is no legislation mandating reporting of continuing care quality information.

The discussion and consideration of publicly reporting continuing care data are related to the wealth of data that will soon be available in Canada. The country has recently begun adopting the RAI tools in continuing care facilities throughout multiple jurisdictions. Several provinces have mandated the implementation of the tools, creating a standardized set of variables that could be used to compare facilities across regions, provinces and nationally. This paper explores what is currently known about the use of public reporting in healthcare and nursing homes in the United States to determine what lessons can be learned when implementing a public reporting system.

Methods

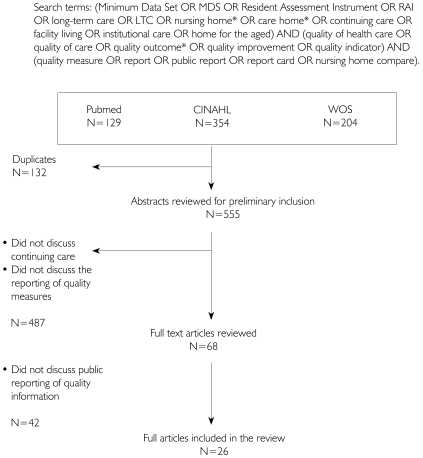

In May 2008, we conducted a comprehensive search to retrieve all literature relevant to the public reporting of nursing home quality of care in the United States and Canada (see Figure 1 for a detailed summary of the search strategy). The following search terms were used in CINAHL Plus with full text (1937 to present), Pubmed (1950 to present) and Web of Science: Minimum Data Set, MDS, Resident Assessment Instrument, RAI, long-term care, LTC, nursing home, care home, continuing care, facility living, institutional care, home for the aged, quality of healthcare, quality of care, quality outcome, quality improvement, quality indicator, quality measure, report, public report, report card, nursing home compare. A research assistant (KD) scanned all abstracts and retrieved relevant papers. Reference lists of relevant papers were scanned for additional papers. We included papers that reported empirical findings from studies of the use of public reporting systems in long-term care, and papers that reported empirical results of surveys about public reporting in nursing homes and long-term care. Descriptive and observational study designs to evaluate public reporting in long-term care were included. Studies conducted to evaluate public reporting in the long-term care setting (n=6) are reported in Table 1. In addition, a number of opinion-based articles (n=16) and select studies conducted to evaluate public reporting in other health sectors (n=4) were retrieved to inform our review.

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart of search and article selection strategy

TABLE 1.

Studies evaluating public reporting in the nursing home sector

| Reference | Aims | Design and sample characteristics | Main findings | Methodological strengths or shortcomings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Castle, N. 2005 | To examine administrators' opinions of the Nursing Home Compare (NHC) website initiative and its influence on quality improvement | Design: Cross-sectional survey Sample size: n=324 Subjects: Nursing home administrators Setting: Four states Country: USA Response rate: 68% |

90% had viewed the NHC website. 51% said they would, in the future, use the information for quality improvement purposes. 33% said they were currently using the information for quality improvement purposes. |

Potential for response bias Restricted to four states of USA Administrators' opinions were used as a proxy for those of consumers. |

| Castle, N. and T. Lowe 2005 | To identify which states produce nursing home report cards To compare information contained in the report cards To identify sources of information used in the report cards To examine factors identified as being associated with the usefulness of the report cards |

Design: Exploratory descriptive study Sample size: n=19 states Setting: Nursing home Country: USA |

19 states were identified as having nursing home report cards. Although the data sources did not vary considerably, the information included in the nursing home report cards varied significantly. Across states, there was substantial variation in the method of presentation of the information. Sources of information used in the report cards included annual licensure and recertification inspection reports, MDS data and primary data such as satisfaction survey data. Factors identified to be associated with the utility of report cards included a user-friendly structure, explanatory information and navigation aids, layering information for a diverse audience, using a stepwise approach to minimize complexity in decision-making, explanation about how and why to use quality information in decision-making, large font size and ample white space. |

The researchers undertook evaluations of the utility of the report cards. Thus, the opinions of consumers were not sought in this study. |

| Castle, N., J. Engberg and D. Liu 2007 | To examine changes in quality measure scores over one year To assess whether competition and/or demand have influenced changes in the scores |

Design: Cross-sectional data collected at two time points, a year apart Data sources: The NHC website and the On-line Survey Certification and Recording (OSCAR) system Setting: Nursing home Country: USA |

An average decrease in scores occurred for eight quality measures, while there was an average increase in scores for six quality measures. An average of less than 1% change in the quality measures was reported. An association was found between (a) competition and improved quality measure scores and (b) lower occupancy and improved quality measure scores. |

Changes in quality observed are not necessarily the result of the report card availability. RAI-MDS reporting by facilities may have changed during the year. |

| Grando, T., M. Rantz and M. Maas 2007 | To elicit the opinions of nursing home staff on a quality performance feedback quality improvement intervention | Design: Qualitative exploratory descriptive study Sample size: n=9 nursing homes (six of which had received the intervention) Subjects: Facility staff directly involved in a prior QI Feedback Intervention trial Setting: Nursing homes in one state Country: USA |

Of the six nursing homes that received the feedback intervention, all found the QI Feedback reports useful. The reports helped identify potential quality problems and enabled tracking of the potential problems over time. Accuracy of the QI reports was questioned; this prompted critique of the RAI-MDS assessments undertaken by staff. Willingness of administrators to change practice based on the feedback reports varied. |

This study was conducted in a small number of facilities in one state in the USA. Therefore, generalizing the findings beyond this setting is difficult. |

| Mukamel, D., W. Spector, J. Zinn, L. Huang, D. Weimer and A. Dozier 2007 | To examine nursing home administrators' responses to public reporting through Nursing Home Compare | Design: Cross-sectional survey Sample size: n=724 Subjects: Chief administrators Setting: Nursing homes nationally Country: USA Response rate: 48% |

82% of administrations had viewed their scores on at least one occasion. 69% of respondents reported having viewed their scores for the first and subsequent publications. 60% of respondents believed that quality of care (among other factors) influenced the quality measures. Less than 1% of respondents believed the report card data (quality measures and deficiency citations) were the most important factor in consumer decision-making. In response to publication of quality measures, 63% of respondents reported having investigated their scores, 42% reported having re-prioritized their quality improvement program, and 20% initiated a new quality improvement program and sought assistance from their Quality Improvement Organization (contracted by Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services). |

National sample Potential for self-report bias |

| Stevenson, D. 2006 | To determine whether findings of public reporting in the acute care setting can provide insights for public reporting in the nursing home sector To evaluate the effects of public reporting of nursing home data to date |

Design: Longitudinal observational study, including OSCAR data from pre- and post-release of Nursing Home Compare Data sources: The NHC website and the On-line Survey Certification and Recording (OSCAR) system Setting: Nursing home Country: USA |

Reports of quality data appear to have a very small influence on nursing home occupancy rate. | Absence of a control group Occupancy rate, as a dependent variable, is limited by the capacity for occupancy to change in response to quality. |

Framework used to analyze the literature

We did not find existing frameworks to guide our analysis of this literature, but two dominant themes emerged in the review: issues related to accountability for quality, and issues related to consumer choice. We used these two themes to guide our analysis and to frame the presentation of findings and discussion.

Results

A large proportion of the literature on public reporting discusses the healthcare sector in general, particularly reporting on acute care hospitals. A small proportion is specific to long-term care, and we largely restricted our analysis to this literature, including discussion about public reporting in other healthcare sectors only as background. All the research conducted to examine the influence of public reporting in long-term care that we located has been undertaken in the United States. The overall findings related to use and impact of public reporting are inconclusive. Although Nursing Home Compare receives over 100,000 hits per month, there is no mechanism to identify who is accessing the data or to determine how the information is being used (Stevenson 2006; Mor 2005).

The effect of public reporting on the quality of care

Recent studies show mixed results with respect to the effect of public reporting of long-term care facility performance data on quality improvement and consumer choice (Mukamel et al. 2007). One study reported that a considerable number of facilities have shown an increase in their quality measure scores (high scores signify potential quality problems) since the launch of NHC (Castle et al. 2007). There is evidence to suggest, however, that the use of facility feedback reports can lead to improved quality of care. Grando and colleagues (2007) found that the use of feedback reports with nursing home staff helped with benchmarking and tracking. They also found that additional support in the form of consultation with advanced practice nurses helped the staff to learn and implement best practices based on the information in the report. These results suggest that there is potential for public reporting to eventually translate into increased quality of care, provided that the staff are accessing the reports and have access to a consultant to assist with the establishment and implementation of best practices.

The effect of public reporting on accountability

Two studies surveying nursing home administrators following the launch of NHC found a small impact of public reporting on accountability (Mukamel et al. 2007; Castle 2005). In a survey conducted by Mukamel and colleagues (2007), 69% of the surveyed facilities reported consistently checking their scores on the NHC website. Forty-two per cent of facilities indicated that they had changed their priorities or existing quality assurance programs based on the data that they had seen, and 20% were more motivated to start new quality programs. In a survey conducted by Castle (2005), 33% of surveyed administrators were using information posted on the NHC website, and 51% planned to use the information to assist with their quality improvement plans in the future.

Reaction to public reporting by providers

When data are reported publicly, providers appear to be more concerned about certain aspects of the information, particularly the quality of data used in reporting. Several concerns have been expressed regarding the NHC website. Mukamel and colleagues (2007) found that nursing home administrators were undecided about whether the data reported on the NHC website were a valid measure of the quality of care provided in their respective facilities. Other concerns have been expressed regarding the validity of the data being used to calculate the measures (Mukamel et al. 2007; Castle 2005). However, 60% of the administrators believed the quality indicators were influenced, at least in part, by the quality of care provided. Administrators responding to Castle's (2005) survey were critical of the risk adjustment methods used, but the majority of their concerns related to a lack of understanding of how the risk adjustment was conducted. They were also averse to posting of the deficiency citations on the website.

Use of publicly reported information for consumer choice

The evidence regarding the use of publicly reported data by long-term care consumers is scant. Castle's (2005) study of nursing home administrators found that although administrators reported that the information on NHC was very helpful for their purposes, they did not believe it would be as relevant to or beneficial for consumers. They were also concerned about the ease of use, understandability and interpretability of the information for consumers. The administrators were not confident that the NHC information would have utility for consumers choosing a facility. Moreover, they were skeptical about whether NHC information had been used by potential residents of their facilities and even more skeptical about whether such information had discouraged potential residents. Similar to the findings of Castle, Mukamel and colleagues (2007) found that administrators perceived the quality report card information to have minimal influence on consumer choice, and 74% of administrators reported that they had never received an inquiry about the quality scores of their facility.

Stevenson (2006) evaluated the effect of public reporting on nursing home choice by consumers. To do so, he compared occupancy rates of nursing homes prior to and following public reporting of information on NHC. He hypothesized that differences in occupancy rate trends between nursing homes with relatively better or worse quality scores would be observed if consumers were using the publicly reported data. Overall, Stevenson found that public reporting of quality information had a minor effect on nursing home occupancy rates.

Castle and colleagues (2007) undertook a study to examine whether nursing home quality scores were influenced by competition or excess supply over a one-year period. While changes in the scores, overall, reflected improvement in quality, the improvement was relatively small. Associations were found between improved scores and high competition, low occupancy and interaction among competition and occupancy rates. Thus, market pressures appeared to influence nursing home quality scores.

Issues related to the method of public reporting

Following their evaluation of the content of nursing home report cards across 19 US states, Castle and Lowe (2005) identified a number of characteristics associated with the utility of such reports. They recommended against the provision of ratings only for individually selected facilities, an approach that requires the consumer to undertake time-consuming retrieval of information from a number of facilities in order to make comparisons. They argued for the provision of benchmark data to enable consumers to make comparisons according to relative quality. They also recommended the inclusion of explanatory information, navigation aids and tools to facilitate comparisons among nursing homes and according to region and state averages. Explanation about how and why to use quality information in decision-making, along with links or reference to additional resources that can assist in choosing a nursing home, was considered useful to some consumers. Layering of information for a range of audiences and use of a stepwise approach to information retrieval was suggested in order to minimize complexity in decision-making. Reporting excessive amounts of information was discouraged. Finally, Castle and Lowe (2005) recommended the report be presented in a user-friendly manner, divided into concise sections, and that a large font size and judicious use of white space be employed.

Limitations of the research

When positive results have been observed, it has often been difficult to attribute the changes to public reporting. It is possible that these changes are occurring independently of the NHC website and are the result of internal quality improvement initiatives (Castle et al. 2007). Another possibility is that scores improve because staff become more proficient at completing RAI-MDS assessments. While it is very difficult to find appropriate comparison groups for nationally implemented policy, one general criticism of most of the public reporting studies is that they fail to include a control group, making it difficult to credit public reporting with the change (Schneider and Lieberman 2001).

Discussion

In our review of the use of public reporting of quality indicators in long-term care facilities, we found that there were two primary reasons for public reporting: first, accountability, in holding facilities publicly accountable for the quality of care they provide; and second, consumer choice, providing information to consumers to assist them in choosing a facility for care. The evidence on the effectiveness of public reporting in long-term care for either purpose is still unclear. We address these issues as they could apply to consideration of public reporting in Canada. We also draw on evidence on public reporting of quality information in other healthcare sectors, highlighting areas where they may inform public reporting in the long-term care sector.

Consumer choice

Although the apparent primary motivation behind Nursing Home Compare is to provide information to help consumers choose a nursing home, there is little evidence that it achieves its aim. Further, the quality measures were developed to identify potential quality problems and have not undergone consumer testing for their utility in a public report card (Castle and Lowe 2005). Similar findings to those from long-term care have emerged from research conducted in other healthcare settings. Early studies from the 1980s and 1990s found that public reporting of acute care hospital performance data had little impact on quality improvement and consumer choice (Laschober et al. 2007). Some studies concluded that the impact of public reporting has been assumed but has yet to be demonstrated (Werner and Asch 2005), while others have concluded that public reporting has had a positive impact (Werner and Asch 2005; Laschober et al. 2007). Several concerns have been reported in studies in other healthcare settings relating to the interpretation of the quality measures and the fear that consumers will use them as direct indicators of quality of care instead of their intended use as indicators for potential quality problems (Mor et al. 2003; Marshall et al. 2000).

Consistent with findings from research in long-term care, some studies in other settings suggest that when data are available, consumers are not using publicly reported information to make healthcare decisions. One study of health plan insurers, purchasers and consumers found that when health plan information was made public, consumers did not use the information to select their health plans (Schauffler and Mordavsky 2001). Other studies have demonstrated that the public tends to rely on alternative sources such as trusted professionals, friends and family when making important health-related decisions (Schneider and Lieberman 2001; Marshall et al. 2000). Schneider and Lieberman (2001) concluded that public reporting has had minimal impact on consumer choice, but has potential to stimulate quality improvement.

Overall, public reporting in healthcare in the United States may have resulted in some quality improvements, but it has not generated the “consumer choice” response that was expected (Schneider and Lieberman 2001). In order for public reporting to work, consumers have to believe that quality varies across facilities and that they have a choice in their care provider (Mor et al. 2003). However, the process of selecting a hospital or nursing home is usually not characterized by free consumer choice. This factor may decrease the role of publicly reported information in the facility selection process (Stevenson 2006).

In the ideal as constructed through microeconomic theory, free markets are characterized by fully informed consumers exercising free and independent choice under minimal constraints. Most nursing home markets in the United States and Canada are not competitive. Most consumers of nursing home beds come from a hospitalization immediately prior to entering a nursing home. In this case, the consumer and his or her family members or proxies generally exercise little or no choice. Hospitals are usually under extreme pressure to move long-term care patients out of hospital beds. In the United States, this situation is related both to excess demand for hospital beds and also to the prospective payment system used by Medicare and many insurers, in which a hospital is paid a fixed sum based on the Diagnosis Related Group into which the patient falls. There is enormous economic incentive for hospitals to discharge patients. As a result, consumers – patients and their families – find that they have little choice about accepting a nursing home bed in order to be discharged from acute care (Mukamel and Spector 2003). The fact that most nursing home care is not paid for through the same funding mechanism as acute care in the United States creates a significant disconnection between the payment incentives facing hospitals and those facing long-term care facilities. Most US consumers entering long-term care from acute care may have their initial stay in a nursing home paid for by Medicare, the funding system for Americans over 65 years of age. However, this payment typically lasts for at most 100 days, often much less, and is dependent on restorative or rehabilitation potential. For consumers whose needs cannot be met by relatively quick rehabilitation, a long-term care stay transitions through private payment into the Medicaid system, which is a joint federal–state system of funding, at much lower levels than Medicare or private pay. As a result, for most new residents of long-term care, issues of choice become largely subjugated to issues of necessity.

In Canada, the issue is less the payment system and more the reality of excess demand for hospital and long-term care beds. In most Canadian jurisdictions, there is a severe shortage of acute hospital beds. As a result, when an acute care patient is deemed no longer in need of acute care, there is considerable pressure to discharge them from acute care as quickly as possible. For many older Canadians, this requires long-term care placement. Most jurisdictions in Canada also have an acute shortage of long-term care beds, and as a result, consumers being discharged into long-term care are forced to take the first available bed, rather than exercise choice in selecting a long-term care facility. While there may be opportunities to transfer among facilities after entering long-term care, in practice, this is seldom an option, as most long-term care facilities are under constant pressure for their beds.

Given that the decision to be placed in a continuing care facility is rarely one of free will, a key group that needs to be targeted in this process is hospital discharge planners. It is often the hospital discharge planner who plays the largest role in determining which facility best suits the resident. It is important that this group be aware of the publicly reported information and that they share it with residents and their families (Angelelli et al. 2006). That said, in order for discharge planners to start relying on this information, they will need to be assured that data posted on the website is current and accurate. This means that the website would need to be updated as soon as changes occur in a facility (e.g., number of vacancies).

Accountability and quality improvement

If public reporting is to influence quality of care, the information has to be readily available, consumers have to be using the information in choosing facilities, and facilities need to be rewarded for high-quality performance (Galvin and McGlynn 2003). Decision-makers and facility leadership also have to be aware of the information, be able to trust its validity, and be able to access, understand and take action based on it (Stevenson 2006). Studies in long-term care and hospital settings have shown that public reporting has helped initiate change in attention to quality, quality improvement programs, documentation and staff involvement in quality improvement and quality scores (Laschober et al. 2007; Castle 2005). However, it seems unlikely that all these improvements can be attributed to public reporting. In a study of hospital quality improvement directors, 56% indicated that public reporting is at the very least partially responsible for their improvements, but 47% indicated that the changes would have taken place regardless of the public reporting. Seventy-five per cent of the quality improvement directors did credit public reporting for the improved documentation observed at the sites (Laschober et al. 2007).

In a study of the impact of public reporting on quality improvement in hospitals in Wisconsin, researchers found that when data are publicly reported, hospital staff exhibit greater concern for the validity of the data than when the report is being distributed only internally (Hibbard et al. 2003). In the same study, respondents from hospitals for which data were publicly reported perceived that the reports affected the public image of their hospital and reported being involved in a higher number of quality improvement activities (Hibbard et al. 2003). Concerns were also voiced about the quality and consistency of coding and the lack of transparency of the risk adjustment methods in relation to public reporting (Hibbard et al. 2003). NHC does risk-adjust some of their quality measures in an attempt to address this concern, but many providers question or do not understand the risk-adjustment methods.

Potential negative consequences of public reporting

Once the data have been made public, it is likely that providers will respond to the reports in one of three ways: (a) denial, (b) taking actions that lead to dysfunctional or unintended consequences or (c) adoption of worthwhile quality improvement activities (Marshall et al. 2004). There has been little research exploring the potential negative consequences of public reporting, and at this point, it is difficult to determine whether the potential benefits outweigh the potential negative consequences. There is also apprehension related to accurate capture of the case mix of clients and being subject to penalties for admitting residents with higher care needs. One concern is that facilities will begin exhibiting biased selection of residents or “cherry-picking,” meaning that facilities become selective of the residents admitted to ensure that their quality measure scores remain low (Mor et al. 2003; Stevenson 2006). There is also a concern that facilities will be penalized for accurate documentation and assessment of their clients (Mor et al. 2003). For example, a facility that is reporting high pain levels may have staff that are skilled in pain assessment and may be providing optimal care to residents experiencing pain. Therefore, their scores on a pain quality measure would be appropriately high. Other possible negative consequences include adverse impacts on staff morale and a tendency for the media to focus on the negative information that is reported. On a positive note, the survey of nursing home administrators conducted by Mukamel and colleagues (2007) suggests that dysfunctional and unintended consequences are not prominent.

Recommendations

Releasing information publicly has shown some improvement in some areas, but not consistently across all measures. Until more consistent results are observed, public reporting should not be used at the policy level as the only mechanism for quality improvement. Overall, the results on public reporting in the United States are inconclusive and inconsistent; however, some lessons can be drawn from the US experience.

If Canadian jurisdictions were to implement public reporting systems, reporting should probably begin internally at the facility level prior to public release of the information, a conclusion we draw from the findings of Hibbard and colleagues (2003). This approach would allow the facilities and staff a period of time to adjust to the reporting and address concerns that may arise during the process. These authors also recommend that preliminary reports be shared with facilities prior to releasing the information publicly, and that all stakeholders collaborate during the report development process. Once the report is released publicly, it is important that potential users, including consumers and the media, be educated on how to interpret the report and to ensure that there is a mutual understanding of what is meant by quality and of the measures being used (CHSRF 2007; Mor et al. 2003; Laschober et al. 2007). Indeed, the work of Arling and colleagues (2005) on nursing home quality indicators led them to conclude that consumers and providers may have different needs in regard to the type of information included in the reports. Therefore, it may be necessary to develop separate reports targeted towards specific audiences.

When the report has been developed and is being shared with the public, it should be available to a broad audience and should be released on a consistent basis (Hibbard et al. 2003). The information must be accurate and timely, and users should be aware that the report is being released. To assist with proper interpretation of the data and to ensure that the information is being used to improve quality, supplemental information should be included as a component of the report. For the public, the reports should include explanations about why performance on an indicator reflects quality of care in a facility, as well as an explanation as to why lower scores are preferred (Marshall et al. 2004). It would also be beneficial to include information on the meaning of differences among provider, state and national averages as well as define what is considered an acceptable deviation from the mean (Mor 2005). For facilities, report cards should be accompanied by information on techniques and methods that may be helpful to improve scores on the quality measures where they are not performing well (Mukamel et al. 2008).

Recommendations for policy makers

Our primary recommendation to Canadian policy makers, based on our review of the literature, is that accountability, rather than consumer choice, should be the main motivator for considering reporting quality information in long-term care. We recommend that reporting begin with a period – possibly as long as two to three years – of internal reporting within the long-term care sector, with benchmarked reports to stimulate appropriate competition. Following this period, public reporting may make sense.

Recommendations for researchers

It is clear from our review of the US literature on public reporting in long-term care that there are gaps in our knowledge about how this works in practice, and how it could work if well designed, either for promoting consumer choice, or for increasing accountability and stimulating quality improvement. We believe that further research is needed to explore how best to design reporting systems, whether public or internal to an industry or facility, to motivate quality improvement. We also believe that further research on the dimensions of consumer choice in this sector – particularly as the number of long-term and acute care beds increase in a community along with the potential for consumer choice – is critically needed. Our interpretation of the state of the science in this area is that it is still significantly underdeveloped, and the opportunities that will emerge in Canada over the next several years, as MDS data become widely available, make Canada an ideal environment for conducting this research. The links to public payment for long-term care services are also better aligned within Canada than in the United States, and we believe that this factor offers the potential to explore issues of the effect of reporting on long-term care quality on consumer choice.

Future research

Future research in the area of public reporting should include mechanisms to monitor and evaluate the process to determine whether the effects are long-lasting and result in overall improvement in quality measure scores. Future studies should also focus on developing indicators that provide information that is valued by the consumer, and on testing the impact of the measures upon healthcare choices (Schauffler and Mordavsky 2001).

Conclusion

It is difficult to derive strong lessons about the use of public reporting for continuing care in Canada from lessons learned in the United States and reported in the published, peer-reviewed literature. One conclusion that can be drawn is that public reporting cannot be relied upon as the only mechanism for quality improvement (Mukamel et al. 2008; Schneider and Lieberman 2001). Although public reporting has been ongoing in healthcare for well over 20 years, and for several years in long-term care, its impact on consumer choice and quality improvement remains largely unknown. The available evidence is mixed, and as yet, the literature is still developing. Canadian jurisdictions can learn from the US experience in developing public reporting processes. If policy makers in Canada want to see a large positive effect from public reporting, they should ensure that sufficient time and effort are invested in the development and implementation of reporting mechanisms and the education of, and dissemination to, industry and the public. Moving too quickly to public reporting can lead to distrust between providers and policy makers, and may result in attempts to “game” the reporting system. This result could prompt facilities to refuse admission to prospective residents who might make an institution's quality measures look worse.

Acknowledgements

The Institute for United States Policy Studies, University of Alberta, Edmonton, provided funding for this work. Dr. Hutchinson is supported by CIHR and AHFMR fellowships. Dr. Sales holds a CIHR Canada Research Chair in Interdisciplinary Healthcare Teams.

Contributor Information

Alison M. Hutchinson, Postdoctoral Fellow, Faculty of Nursing, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB.

Kellie Draper, Research Assistant, Faculty of Nursing, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB.

Anne E. Sales, Professor, Faculty of Nursing, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB.

References

- Angelelli J., Grabowski D., Mor V. Effect of Educational Level and Minority Status on Nursing Home Choice After Hospital Discharge. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96(7):1249–53. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.062224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arling G., Kane R., Lewis T., Mueller C. Future Development of Nursing Home Quality Indicators. Gerontologist. 2005;45(2):147–56. doi: 10.1093/geront/45.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auditor General Alberta. Edmonton: Author; 2005. May, Report of the Auditor General on Seniors Care and Programs. Issue brief no. 0-7785-3717-X. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Health Services Research Foundation (CHSRF) Ottawa: Author; 2007. Sep, Public Reporting on the Quality of Healthcare: Emerging Evidence on Promising Practices for Effective Reporting. [Google Scholar]

- Castle N. Nursing Home Administrators' Opinions of the Nursing Home Compare Website. Gerontologist. 2005;45(3):299–308. doi: 10.1093/geront/45.3.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castle N., Lowe T. Report Cards and Nursing Homes. Gerontologist. 2005;45(1):48–67. doi: 10.1093/geront/45.1.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castle N., Engberg J., Liu D. Have Nursing Home Compare Quality Measure Scores Changed Over Time in Response to Competition? Quality & Safety in Health Care. 2007;16(3):185–91. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2005.016923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvin R., McGlynn E. Using Performance Measurement to Drive Improvement: A Road Map for Change. Medical Care. 2003;41(1 Suppl):I48–60. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200301001-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabowski D., Castle N. Nursing Homes with Persistent High and Low Quality. Medical Care Research & Review. 2004;61(1):89–115. doi: 10.1177/1077558703260122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grando T., Rantz M., Maas M. Nursing Home Staffs' Views on Quality Improvement Interventions – A Follow-up Study. Journal of Gerontological Nursing. 2007;33(1):40–47. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20070101-08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington C., Collier E., O'Meara J., Kitchener M., Simon L., Schnelle J. Federal and State Nursing Facility Websites: Just What the Consumer Needs? American Journal of Medical Quality. 2003;18(1):21–37. doi: 10.1177/106286060301800105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris Y., Clauser S. Achieving Improvement through Nursing Home Quality Measurement. Health Care Financing Review. 2002;23(4):5–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Quality Council. Saskatoon: Author; 2006. Mar, Public Disclosure of Information on Quality of Health Care. Discussion paper. [Google Scholar]

- Health Quality Council of Alberta. Highlights of the Long-Term Care Resident and Family Experience Surveys. Calgary: Author; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hibbard J., Stockard J., Tusler M. Does Publicizing Hospital Performance Stimulate Quality Improvement Efforts? Health Affairs. 2003;22(2):84–94. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.22.2.84. Project Hope. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laschober M., Maxfield M., Felt-Lisk S., Miranda D. Hospital Response to Public Reporting of Quality Indicators. Health Care Financing Review. 2007;28(3):61–76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall M., Romano P., Davies H. How Do We Maximize the Impact of the Public Reporting of Quality of Care? International Journal for Quality in Health Care. 2004;16(Suppl. 1):i57–63. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzh013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall M., Shekelle P., Leatherman S., Brook R. The Public Release of Performance Data: What Do We Expect to Gain? A Review of the Evidence. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;283(14):1866–74. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.14.1866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mor V. Improving the Quality of Long-Term Care with Better Information. Milbank Quarterly. 2005;83(3):333–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00405.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mor V., Berg K., Angelelli J., Gifford D., Morris J., Moore T. The Quality of Quality Measurement in US Nursing Homes. Gerontologist. 2003;43:37–46. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.suppl_2.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukamel D., Spector W. Quality Report Cards and Nursing Home Quality. Gerontologist. 2003;43:58–66. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.suppl_2.58. Spec. no. 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukamel D., Spector W., Zinn J., Huang L., Weimer D., Dozier A. Nursing Homes' Response to the Nursing Home Compare Report Card. Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2007;62(4):S218–25. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.4.s218. Journals of Gerontology: Series B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukamel D., Weimer D., Spector W., Ladd H., Zinn J. Publication of Quality Report Cards and Trends in Reported Quality Measures in Nursing Homes. Health Services Research. 2008;43(4):1244–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2007.00829.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Advisory Council on Aging. Ottawa: Author; 2005. NACA Demands Improvement to Canada's Long-Term Care Institutions. Press release. [Google Scholar]

- Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. Reports on Long-Term Care Homes. 2009. Jun 15, Retrieved October 16, 2009. < http://www.health.gov.on.ca/english/public/program/ltc/26_reporting.html>.

- Schauffler H., Mordavsky J. Consumer Reports in Health Care: Do They Make a Difference? Annual Review of Public Health. 2001;22:69–89. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.22.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider E., Lieberman T. Publicly Disclosed Information about the Quality of Health Care: Response of the US Public. Quality in Health Care. 2001;10(2):96–103. doi: 10.1136/qhc.10.2.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. 2001 Census. 2001. Retrieved October 16, 2009. < http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/english/census01/home/Index.cfm>.

- Statistics Canada. Population Projections for Canada, Provinces and Territories, 2005–2031. Ottawa: Author; 2005. Catalogue no. 91-520-XIE. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. Ottawa: Author; 2006. Portrait of the Canadian Population in 2006, by Age and Sex, 2006 Census. Catalogue no. 97-551-XIE. [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson D. Is a Public Reporting Approach Appropriate for Nursing Home Care? Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law. 2006;31(4):773–810. doi: 10.1215/03616878-2006-003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner R., Asch D. The Unintended Consequences of Publicly Reporting Quality Information. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2005;293(10):1239–44. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.10.1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]