Abstract

This study investigated the link between childhood maltreatment and substance use focusing on examining contingencies of self-worth (CSW) as mediators among college students (N = 513). Structural equation modeling indicated that childhood sexual abuse among females was related to lower God’s love CSW, which in turn was related to higher levels of cigarette, marijuana, and other illicit drug use, supporting the mediational role of God’s love CSW. Correlational analyses demonstrated that, for both male and female students, external contingency of appearance was related to higher substance use, whereas internal contingencies of God’s love and virtue were related to lower substance use. The findings highlight the protective role of internal CSW in substance use among females with childhood sexual abuse.

Keywords: emotional abuse, physical neglect, physical abuse, sexual abuse, contingencies of self-worth, substance use

Maltreatment experienced during early stages of development seems to have a profound impact on the individual (Cicchetti & Rogosch, 2002). Prior evidence supports the contention that the maltreating environment has a substantially negative impact on the individual’s capacity to negotiate the progression of developmental tasks and challenges. Maltreated individuals manifest deficits in the competent resolution of the salient tasks of the life course and develop consequent vulnerabilities for psychopathologic conditions. Adolescents with past maltreatment experiences have been found to have greater difficulty with developmental tasks (Cicchetti & Lynch, 1995). These adolescents may not have been able to develop proper problem solving skills and therefore have a greater difficulty making the transition from adolescence to adulthood.

A developmental psychopathology approach allows us to better understand individual traits and environmental factors and how they mutually influence each other throughout the development of the individual (Cicchetti & Rogosch, 1999). It is important to note that while childhood maltreatment may have a deleterious effect on future development, there are other factors that may buffer or ameliorate the negative impact of child maltreatment. For example, some individuals, despite traumatic experiences of childhood abuse and neglect, develop resilience to these negative life events. Knowledge about developmental processes contributing to dysfunction and resilience is critical for understanding pathways to adaptive and maladaptive development (Luthar, Cicchetti, & Becker, 2000).

Childhood Maltreatment Experiences and Substance Abuse

Traumatic experiences during childhood can affect later development in multiple ways. Prior research has demonstrated that maltreatment experiences increase the risk for maladaptive development and involvement in risk behaviors including substance use (Cicchetti & Toth, 2005; Clark, Thatcher, & Maisto, 2004; Harrison, Fulkerson, & Beebe, 1997). Individuals who experienced childhood maltreatment may use substances to escape the negative feelings that are associated with these negative life events. However, most previous research failed to consider differential effects of different subtypes of maltreatment (e.g., Higgins & McCabe, 2001). Available studies have provided some support for differential effects of specific subtypes of maltreatment on the future adjustment of the individual. For example, of the three maltreatment subtypes including emotional abuse, physical abuse, and sexual abuse, childhood emotional abuse has the strongest relations with depression among children (Kim & Cicchetti, 2006) and young adults (Gibb et al., 2001). Similarly, McGee, Wolfe, and Wilson (1997) reported that psychological abuse was the most prominent predictor of college students’ internalizing problems compared to physical abuse, sexual abuse, physical neglect, and exposure to family violence. Dodge, Pettit, and Bates (1997) found that individuals with a history of physical abuse are more likely to show aggressive behaviors.

Research by Trickett and McBride-Chang (1995) has shown that physical, sexual, and physical/sexual combined abuse puts the individual at much greater risk for substance abuse problems later in life. Similarly, Moran, Vuchinich, and Hall (2004) found that all subtypes of maltreatment (emotional, physical, sexual, and physical/sexual combined) were associated with higher rates of substance use (tobacco, alcohol, and illicit drugs) among high school students, with physical abuse and sexual abuse having the strongest effects. In contrast, in a study of the impact of different subtypes of child maltreatment among college students, Arata and her associates found that only physical neglect was correlated with substance use (a composite of alcohol, marijuana, and other illicit drugs) while other maltreatment subtypes, including emotional abuse, emotional neglect, physical abuse, and sexual abuse, were not (Arata, Langhinrichsen-Rohling, Bowers, & O’Farrill-Swails, 2005). Thus, the findings regarding the differential effects of maltreatment subtypes on substance use among adolescents and college students seem to be mixed.

Experiences of Childhood Maltreatment and the Development of Self-Worth

From a developmental psychopathology perspective, abuse and neglect experiences in childhood are viewed to permeate many domains of a child’s development. The child who experiences maltreatment becomes unable to successfully complete certain hierarchically organized, stage-salient tasks (Cicchetti & Rogosch, 1997). Unsuccessful completion of developmental tasks can alter the individual’s development of emotional regulation and idea of self. In particular, maltreated children seem unable to establish an autonomous self apart from the caregiver (Cicchetti & Toth, 2005). There is evidence that experiences of maltreatment in childhood have long-term effects on self-esteem suggesting that maltreatment experiences may make an individual vulnerable to developing a negative view of self.

Previous research has shown lower levels of self-esteem among maltreated children and adults (Bolger, Patterson, & Kupersmidt, 1998; Kim & Cicchetti, 2004; Mullen, Martin, Anderson, Romans, & Herbison, 1996). Bolger and associates found that chronic sexual and physical abuse experienced in childhood presents a higher risk of developing lower self-esteem when compared to the other subtypes. In contrast, Kim and Cicchetti (2006) found that experiences of emotional abuse were stronger predictors of low self-esteem and depression than physical abuse. Furthermore, positive self-esteem played an important role as a protective factor, enhancing healthy development of the individual in the face of childhood maltreatment.

Feelings of Self-Worth and Substance Use

Substance abuse among college students in the U.S. is currently a well-acknowledged problem. With lethal binge drinking and drug overdoses occurring at alarmingly high rates, studying the risk and resilience factors that bring students to overindulge is becoming an important task (Knight et al., 2002).There has been much speculation as to the driving force for these young adults to engage in risky behaviors. Many have postulated that students choose to use drugs and/or alcohol as an escape from the daily pressures of college life. As suggested above, students who display low feelings of self-worth may be particularly vulnerable to substance use as a way of escaping their negative feelings. Empirical studies on the role of self-esteem in substance use yield inconclusive results. Some researchers have found a significant inverse relationship between the level of self-esteem and rates of substance use. Glindemann and his colleagues found that undergraduate students who tested for low self-esteem scored higher levels overall on a Blood Alcohol Concentration (BAC) breathalyzer test given at a party (Glindemann, Geller, & Fortney, 1999). Pullen (1994) studied predictors of alcohol abuse among 300 college students and found that self-esteem was the second strongest predictor following family abuse of alcohol. In addition, there is evidence that the risk of substance use among adolescents may be enhanced more by lower perceived control rather than self-esteem alone (Wills, 1994). Other studies on substance use among adolescents indicate no significant relationship between low self-esteem and substance use problems. Labouvie and McGee (1986) found no evidence of a self-evaluation score predicting a composite substance use score among adolescents. McGee and Williams (2000) reported a weak relationship between low self-esteem and rate of adolescents’ substance use and concluded that low self-esteem may not play an explanatory role in substance use behavior.

A series of studies on the contingencies of self-worth (CSW) by Crocker and her associates have demonstrated that the link between self-worth and behavior depends less on high vs. low levels of self-worth but rather on where individuals stake their self-worth (e.g., Crocker, Luhtanen, Cooper, & Bouvrette, 2003). Luhtanen and Crocker (2005) reported that whereas the level of self-esteem did not uniquely predict alcohol use among first year college students, the CSW did. More specifically, individuals basing self-worth on appearance reported higher rates of alcohol use, whereas individuals basing self-worth on virtue or God’s love showed restrained or abstinent alcohol use. Further findings by Crocker (2002) indicate that external contingencies are vulnerable to threat (because they need to be constantly maintained) and often produce negative emotional reactions that may lead the individual to seek out the positive feelings that alcohol has to offer.

The Present Study

Prior research has demonstrated that early experiences of abuse and neglect are associated with later health risk behaviors. This is the first study that investigates the role of self-worth contingencies in the link between childhood maltreatment experiences and later substance use behaviors. This study examined contingencies of self-worth as a process variable to obtain a better understanding of the pathway from earlier maltreatment experiences to later substance use. This study also investigated the differential impact of different maltreatment subtypes, including emotional abuse, physical neglect, physical abuse, and sexual abuse, regarding college students’ current substance use.

It was hypothesized that self-worth characteristics may play a mediating role in the development of substance use problems among participants with childhood maltreatment experiences. It was predicted that individuals who base self-worth on external factors (e.g., appearance) will show higher rates of substance use compared to those who rely on internal basis for self-worth (e.g., being a good person). Given that gender differences have been reported to effect vulnerability to maltreatment experiences (Kim & Cicchetti, 2004), the current study examined gender differences in the impact of childhood maltreatment on self-worth contingencies and substance use problems.

Method

Participants

Participants consisted of 513 students from a southeastern university. Age ranged from 18 to 27 years (M = 19.46, SD = 1.34). Of these 513 students, 337 (66%) were females and 176 (34%) were males. For ethnicity, about 423 (83%) categorized themselves as Caucasian, 42 (8%) as Asian, 20 (4%) as African American, 13 (2%) as Hispanic, and 15 (3%) as Other. All participants received research credit for their participation.

Measures

The Family Biography and Life Events Questionnaire

The 4 questions pertaining to the frequency of each of four maltreatment experiences (i.e. emotional abuse, physical neglect, physical abuse, and sexual abuse) were taken from a larger measure, the Family Biography and Life Events Questionnaire, which consisted of 43 items regarding the participant’s previous life experiences (Rich, Gingerich, & Rosen, 1997). The participant was asked to identify whether or not they had experienced each form of abuse or neglect by rating the frequency of maltreatment experiences that occurred during childhood (prior to 14 years of age) on a 6-point scale ranging from 0 (never) to 5 (over twenty times). They were also asked to rate the level of severity of each maltreatment subtype experienced on a scale of 1 (extremely severe) to 5 (not at all severe). The severity scores were reverse coded so that higher numbers indicated greater intensity of maltreatment experiences, and 0 was assigned to those who did not experience the specific maltreatment subtype.

Contingencies of Self-Worth Scale

The Contingencies of Self-Worth Scale consists of 35 items that measure an individual’s basis of self-worth (Crocker & Wolfe, 2001). It includes statements regarding seven different internal and external sources of individual self-worth (e.g., I feel worthwhile when I have God’s love). The participant was asked to rate each statement on a 7-point scale that ranged from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”. Five external contingencies include family support (perceived love and support felt by the individual from his or her family), competition (being superior to others), appearance, academic competence (grades or evaluations by teachers), and approval from others. Two contingencies, virtue and feelings of God’s love, have internal bases: Believing that one is a good person inside, regardless of exterior qualities, is an important part of positive feelings of self-worth, as well as believing in God, which may offer feelings of being a good person and worthy of being loved. In the current sample, each subscale had high internal consistency: α= .78 for family support, α = .85 for competition, α = .77 for appearance, α = .96 for God’s love, α = .79 for academic competence, α = .79 for virtue, and α = .78 for others’ approval.

Substance Use Scale

The four items of the substance use measure used a standard quantity-frequency index (QFI) derived from Armor and Polich (1982) and asked about frequency of alcohol use (beer, wine, wine coolers, hard liquor, or mixed drinks) in the past 6 months (“How often did you usually drink alcohol in the past 6 months?”), and the typical frequency of his or her cigarette, marijuana, and other illicit drug use (e.g., “How often do you smoke cigarettes?”). Responses were made on a seven-point scale for alcohol use with response points ranging from 0 (never) to 7 (everyday). Responses were made on a six-point scale for cigarette, marijuana, and other illicit drug use (such as glue/inhalant) ranging from 0 (never used) to 5 (usually use everyday).

Procedure

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained for the study. Participants were recruited from a variety of undergraduate psychology courses and received credit towards a course requirement for their participation (regardless of whether or not they fully completed the survey). The participants were asked to complete a confidential online survey and were allowed to participate from any computer (i.e. home, office, or school) in a self-paced, anonymous fashion.

Results

Table 1 shows descriptive statistics of maltreatment subtypes, contingencies of self-worth, and substance use separately for male and female students. For maltreatment variables, rate (%) and severity (0–5) of each subtype are reported. Female students were more likely to have experienced emotional maltreatment in childhood compared to male students, χ2 (1, N = 502) = 2.90, p = .05. There was no difference between male and female students regarding physical neglect, χ2 (1, N = 506) = .34, ns, and physical abuse, χ2 (1, N = 512) = 1.17, ns. Mean differences in maltreatment severity scores revealed greater severity in emotional (t = −2.16, p < .05) and physical abuse (t = −1.98, p < .05) among females than males. There was no significant gender difference with regard to severity scores of physical neglect (t = .17, ns). Female students were more likely to have experienced sexual abuse (6.2 % for females vs. 0.6 % for males) and report greater severity of sexual abuse experiences (M = .03 for males and M = .16 for females). However, because the cell size for males (n = 1) was less than the requirement of a minimum cell expectation of five, a chi-square test and a t-test were not performed for sexual abuse (Mantel & Fleiss, 1980).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Maltreatment, Contingences of Self-Worth, and Substance Use

| Male (N=176)a | Female (N=337)a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | M (SD) | N (%) | M (SD) | |

| Maltreatment Experiences | ||||

| Emotional Abuse | 35 (20) | .53 (1.13) | 90 (27) | .77 (1.36) |

| Physical Neglect | 8 (5) | .11 (.52) | 12 (4) | .10 (.52) |

| Physical Abuse | 22 (13) | .28 (.83) | 54 (16) | .45 (1.06) |

| Sexual Abuse | 1 (1) | .03 (.39) | 20 (6) | .16 (.63) |

| M | SD | M | SD | |

| CSWs | ||||

| Family Support | 5.50 | 0.90 | 5.74 | 0.84 |

| Competition | 5.34 | 0.91 | 5.16 | 0.88 |

| Appearance | 4.79 | 0.98 | 5.36 | 0.87 |

| God's Love | 4.23 | 1.86 | 4.28 | 1.81 |

| Academic Competence | 5.51 | 0.86 | 5.75 | 0.72 |

| Virtue | 5.26 | 0.82 | 5.28 | 0.92 |

| Others' Approval | 4.01 | 1.10 | 4.53 | 1.00 |

| Substance Use | ||||

| Alcohol | 3.10 | 1.91 | 3.17 | 1.80 |

| Cigarettes | 1.01 | 1.30 | 1.15 | 1.41 |

| Marijuana | 0.91 | 1.23 | 0.93 | 1.15 |

| Other drugs | 0.16 | 0.54 | 0.20 | 0.60 |

Note: Sample size varies across variables (N=165~176 for males and N=324~337 for females) due to missing data.

As for self-worth contingencies and substance use, gender differences were tested by a series of t-tests with a Bonferroni-based correction to control for Type I errors across multiple CSW variables (i.e., dividing the per comparison alpha level by the number of outcome variables; α =.01 for both self-worth contingencies and substance use). Female students had higher levels of contingencies on family support, t (508) = −3.04, p < .01, appearance, t (508) = − 6.78, p < .01, academic competence, t (508) = −3.22, p < .01, and approval of others, t (508) = − 5.39, p < .01. However, males and females did not differ in terms of the contingencies of competition, t (508) = 2.10, p = .04, God’s love, t (508) =−.31, p = .76, and virtue, t (349) =−.31, p = .76. Male and female students did not differ in reported alcohol use rates, t (509) =−.42, p = .68, cigarette use, t (511) = −1.09, p = .27, marijuana use, t (509) =−.23, p = .82, and other illicit drugs, t (511) =−.58, p = .56.

In Table 2, the bivariate correlations among the variables are presented separately for males and females. The results of the correlation analyses were consistent when dichotomous scores were used (maltreatment subtype presence = 1 and absence = 0) or frequency scores instead of severity scores. Therefore, the results of the main analyses are presented using severity scores (continuous variables). As can be seen in Table 2, for male students, emotional abuse was positively, yet moderately, correlated with virtue CSW. Sexual abuse among male students was negatively correlated with academic competence CSW, and positively correlated with alcohol and cigarette use. However, it should be noted that there was only one male student who reported sexual abuse experience in the current sample. With respect to the associations between CSW and substance use among male students, correlation results indicated that appearance CSW was positively correlated with alcohol and marijuana use. Finally, God’s love and virtue CSWs were negatively correlated with cigarette, marijuana, and other illicit drug use.

Table 2.

Bivariate Correlations among Childhood Maltreatment, Self Worth Contingencies, and Substance Use for Males and Females

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Emotional Abuse | .05 | .40* | .31* | −.04 | .08 | −.07 | −.00 | .04 | .19* | −.04 | .03 | −.04 | −.11 | −.02 | |

| 2. Physical Neglect | .34* | −.03 | −.02 | −.02 | .12 | −.06 | −.00 | .08 | .07 | .14 | −.12 | −.11 | −.12 | −.06 | |

| 3. Physical Abuse | .54* | .21* | .43* | −.08 | −.03 | −.07 | .07 | −.14 | .07 | −.10 | .07 | .09 | .00 | .01 | |

| 4. Sexual Abuse | .19* | −.01 | .31* | −.13 | −.08 | −.08 | −.03 | −.17* | −.01 | .00 | .16* | .24* | .01 | −.02 | |

| 5. Family Support | −.11* | −.18* | −.11* | −.07 | .34* | .13 | .30* | .41* | .31* | .18* | .06 | −.05 | −.09 | −.11 | |

| 6. Competition | .03 | .13* | .04 | −.08 | .16* | .42* | .02 | .55* | .24* | .22* | .08 | −.03 | −.10 | .05 | |

| 7. Appearance | .08 | −.00 | .06 | .03 | .23* | .35* | .02 | .38* | −.09 | .43* | .33* | .10 | .19* | .14 | |

| 8. God’s Love | −.12* | −.07 | −.10 | −.13* | .19* | .07 | −.06 | .05 | .20* | −.07 | −.14 | −.16* | −.20* | −.16* | |

| 9. Academic Competence | .11* | .10 | .08 | −.02 | .33* | .37* | .41* | .05 | .18* | .17* | .11 | −.03 | −.04 | .03 | |

| 10. Virtue | .04 | −.01 | −.07 | −.09 | .33* | .09 | .03 | .32* | .32* | .02 | −.14 | −.25* | −.24* | −.22* | |

| 11. Others’ Approval | −.02 | .07 | .01 | −.03 | .14* | .23* | .49* | .04 | .30* | .11* | .08* | −.01 | .11 | −.00 | |

| 12. Alcohol Use | .05 | .01 | .00 | −.01 | .07 | .05 | .17* | −.18* | .06 | −.19* | .12* | .47* | .48* | .30* | |

| 13. Cigarette Use | .11* | .03 | .09 | .13* | −.01 | .06 | .20* | −.24* | .08 | −.23* | .04 | .46* | .61* | .44* | |

| 14. Marijuana Use | .08 | .06 | .10 | .12* | −.04 | .04 | .16* | −.29* | .03 | −.23* | −.00 | .50* | .67* | .51* | |

| 15. Other Drug Use | .09 | .05 | .11* | .16* | −.02 | .02 | .14* | −.17* | .03 | −.15* | .03 | .22* | .51* | .49* |

Note:Correlations of males are above the diagonal and correlations of females are below the diagonal.

p<.05

For female students (see Table 2), emotional abuse was negatively correlated with family support and God’s love CSWs and positively correlated with academic competence CSW. Emotional abuse was also correlated with higher levels of smoking cigarettes. Both physical neglect and physical abuse were negatively correlated with family support CSW, and physical neglect was positively correlated with competition CSW. Finally, sexual abuse was negatively correlated with God’s love CSW, and further correlated with higher levels of substance use including cigarettes, marijuana, and other illicit drugs.

In order to test possible gender by maltreatment interactions and provide protection against an inflated Type I error rate due to multiple statistical tests, a multivariate General Linear Model (GLM) analysis was performed. In the GLM analysis, the main effects of maltreatment subtypes, gender, and the interaction effects between maltreatment subtypes and gender were investigated for the four substance use outcomes involving alcohol, cigarette, marijuana, and other illicit drug use. As can be seen in Table 3, the main effect of sexual abuse (severity), Wilks’ Lambda F (4, 466) = 4.11, p < .05, and the interaction between sexual abuse and gender, Wilks’ Lambda F (4, 466) = 3.71, p < .05, were significant. Because there was only one male who reported sexual abuse experience in the current sample, further analysis regarding the link between sexual abuse and substance use was focused only on females.

Table 3.

F-Values and Significance Levels for Multivariate Analyses of Gender and maltreatment subtypes (severity) for Adolescent Depressive Symptoms.

| Predictor Variables | Multivariate F | df | Alcohol | Cigarette | Marijuana | Other Drug |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | .31 | 4, 466 | .01 | .29 | .92 | .64 |

| Emotional Abuse | 1.11 | 4, 466 | .34 | 2.27 | 2.87 | .01 |

| Physical Neglect | .78 | 4, 466 | 2.41 | 1.37 | 2.23 | .72 |

| Physical Abuse | .08 | 4, 466 | .08 | .12 | .30 | .05 |

| Sexual Abuse | 4.11* | 4, 466 | 3.80(*) | 8.61* | .11 | .13 |

| Gender × Emotional Abuse | 1.49 | 4, 466 | 1.36 | 5.02* | 2.83 | .15 |

| Gender × Physical Neglect | .57 | 4, 466 | .89 | .62 | 2.11 | .24 |

| Gender × Physical Abuse | .17 | 4, 466 | .15 | .05 | .01 | .26 |

| Gender × Sexual Abuse | 3.71* | 4, 466 | 3.67 | 3.99* | .08 | 1.49 |

Note. Multivariate test is Wilks’ Lambda.

p < .05;

p < .05.

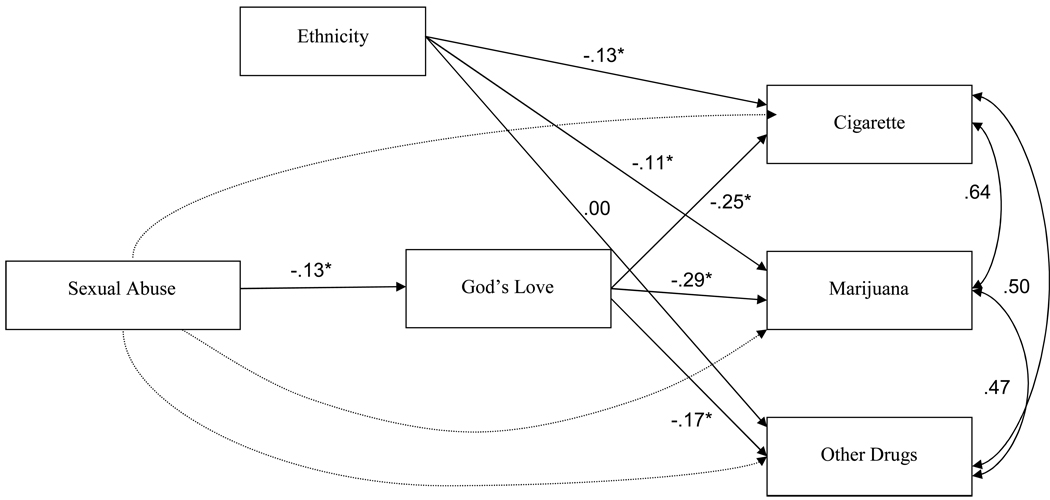

The results of correlation analyses hinted that childhood sexual abuse not only directly contributed to substance use (cigarette, marijuana, and other illicit drug use) among female students, but also indirectly contributed through its association with the God’s love CSW (God’s love CSW was negatively correlated with cigarette, marijuana, and other illicit drug use). In order to probe structural relations of childhood sexual abuse, the God’s love CSW, and female students’ cigarette, marijuana, and other illicit drug use, a mediational model was tested by structural equation modeling using Amos 7.0 program (Arbuckle, 2006) with a maximum likelihood estimation method. As shown in Figure 1, the model estimated both direct associations between sexual abuse (predictor, an exogenous variable) and three substance use outcomes (endogenous variables of cigarette, marijuana, and other illicit drug use), and indirect associations through the God’s love CSW (mediator, an endogenous variable). Ethnicity (coded as Caucasian = 0 vs. minority = 1) was included as a potential demographic covariate (an endogenous variable) to control for any variances that could be explained by ethnicity for substance use outcomes. About 15% (n = 52) of the female respondents belonged to ethnic minority groups.

Figure 1.

Structural model for the relation of child maltreatment and contingencies of self-worth to female students’ substance use. * p < .05.

The best fitting model for childhood sexual abuse, God’s love CSW, and substance use among female students was identified by comparing a full model (including both indirect and direct effects) to an indirect-effect only model. Model fit for the indirect-effect only model was not significantly worse than that of the full model, Δχ2 = 7.10, Δdf = 3, p = .07, suggesting that the effect of childhood abuse on substance use was mediated completely through God’s love CSW. A close examination of the parameter estimates revealed that experiencing childhood sexual abuse was related to lower levels of God’s love CSW, which in turn were predictive of higher levels of cigarette, marijuana, and other illicit drug use. In addition, ethnic minority students were less likely to smoke cigarettes and marijuana than Caucasian students. The squared multiple correlations for the substance use variables in the indirect-only model indicated that the indirect effect of childhood sexual abuse mediated through God’s love accounted for 8% of the variance in smoking cigarettes, 10% of the variance in marijuana use, and 3% of the variance in other illicit drug use.

Discussion

The main objective of this study was to identify pathways between differential maltreatment experiences in childhood and later substance use problems among college students focusing on the role of seven dimensions of CSW (family support, competition, appearance, academic competence, approval from others, God’s love, and virtue) as a mediational mechanism. In addition, gender differences were examined in these pathways. Each of the CSW dimensions was classified as to whether or not it was considered an internal versus an external base. CSWs that are external rather than internal, or dependent on others rather than on one’s own behavior, are much more vulnerable to threat on a day-to-day basis because they constantly require earning the approval of another person, winning an award, or outdoing a competitor. Consequently, external CSWs keep people constantly engaged in the effort to prove that they are worthwhile, and therefore seem to be associated with greater costs (Crocker, 2002).

Based on previous findings of the significant link between childhood maltreatment and later substance use (e.g., Moran et al., 2004; Trickett & McBride-Chang, 1995), it was expected that four maltreatment subtypes would be related to different types of substance use problems. Consistent with previous findings regarding gender differences in maltreatment experiences (e.g., Kim & Cicchetti, 2006; McGee et al., 1997; Moran et al., 2004), this study’s findings suggested that sexual abuse is far more prevalent in females than in males. Among females, sexual abuse experiences predicted increased rates of cigarette, marijuana, and other illicit drug use, mediated through lower levels of God’s love CSW. More importantly, basing one’s self worth on God’s love served as a protective mechanism against substance use in females. This finding provides important implications for research on the roles of contingencies of self-worth among individuals with early traumatic experiences.

The finding of the negative association between sexual abuse and God’s love CSW can be, at least partially, explained by the correspondence hypothesis (Granqvist & Dickie, 2005). The correspondence hypothesis proposes that individuals who have experienced secure, as opposed to insecure, childhood attachments have established the foundations on which a corresponding relationship with God could be built. According to this view, maltreated individuals, who are more likely to have insecure attachment relationships with their primary attachment figures, are less likely to view God as loving and caring compared to nonmaltreated individuals. In line with the correspondence hypothesis, empirical studies have reported negative effects of child maltreatment on religiosity demonstrating that victims of abuse tend to have more negative views on God (e.g., Finkelhor, Hotaling, Lewis, & Smith, 1989; Hall, 1995; Kennedy & Drebing, 2002). In particular, Bierman (2005) examined the effects of physical and emotional abuse on religiosity among adults and found that abuse perpetrated by fathers during childhood was related to decreases in religiosity. It is plausible that the image of God as a father led victims of abusive fathers to distance themselves from religion. In light of the results from the relevant empirical research on maltreatment and views of God, the current finding of the negative association between childhood sexual abuse and God’s love CSW suggests that female survivors of childhood sexual abuse were more likely to have negative views of God and were less likely to derive their feelings of self-worth through the belief that they were loved, valued, and unique in the eyes of God.

This is the first study to examine the relative impact of CSW dimensions in the link between different types of childhood maltreatment experiences and later substance use. Results indicated that God’s love CSW had the strongest protective effect among females who had been sexually abused. It is expected that individuals who regard God’s love as their internal source of self-esteem have strong religious faith. The strong effect of God’s love CSW on substance use is consistent with prior investigations that indicate religiosity as a protective factor for substance use and other health risk behaviors. More specifically, empirical findings have documented that religiosity is associated with lower levels of cigarette, alcohol, marijuana, and illicit drug use among adolescents and young adults (e.g., Brown, Schulenberg, Bachman, O’Malley, & Johnston, 2001; Kliewer & Murrelle, 2007; Miller, Davies, & Greenwald, 2000; Wallace, Brown, Bachman, & Laveist, 2003; Wills, Yaeger, & Sandy, 2003).

The associations between differential maltreatment experiences and the dimensions of CSW are rather complicated. The risk factor of childhood maltreatment is not always related to higher levels of external contingencies. Male students with emotional abuse during childhood were higher on the internal contingency of virtue. Those males who experienced having their emotional needs unmet early in life may have learned to rely on intrinsic aspects of the self (i.e., virtue) for their self-worth feelings. In contrast, female students with emotional abuse were higher on the external contingency of academic competence. Those individuals who suffered from being thwarted of their basic emotional needs by their caregivers early in life may derive their self-esteem from school grades and evaluations by professors. In addition, female students who experienced childhood emotional abuse reported significantly lower levels of God’s love CSW. Consistent with the correspondence hypothesis, individuals whose parents or caregivers were insensitive to the need for positive regard could not feel accepted in early years may have developed negative views of their parents or caregivers. These individuals may have further extended such negative views to God and subsequently became less inclined to base their self-esteem on God’s love and care.

Furthermore, females who experienced emotional abuse, physical neglect, or physical abuse earlier in their lives were less likely to base their feelings of self-worth on family support. Children who experience parental maltreatment do not receive the support necessary to develop a worthy sense of self and are more likely to develop a sense of inner badness (Harter, 1998). The detrimental effect of maltreatment on the development of secure attachment with a caregiver is expected to contribute to low global self-esteem due to feelings of inadequacy and incompetence (Fischer & Ayoub, 1994; Harter, 1998). Females who suffered from emotional and physical abuse in a maltreating home may have learned not to rely on perceived approval or love from family members for their feelings of self-worth.

In general, the findings of linking CSWs and substance use support the proposition by Pyszczynski, Greenberg, and Goldenberg (2003) that individuals who base their self-esteem on core, abstract, unique features of self show better functioning than individuals who base their self-esteem on more conditional, external bases. Indeed, empirical findings from prior studies have demonstrated that external CSWs are positively related and internal CSWs are negatively related to maladjustment outcomes among adolescents and young adults including alcohol and drug use, depression, and aggression (e.g., Burwell & Shirk, 2006; Crocker, 2002; Luhtanen & Crocker, 2005; Sargent, Crocker, & Luhtanen, 2006). The current data showed that both male and female students whose self-esteem was staked upon their evaluation of physical appearance were prone to engaging in substance use. More specifically, the external CSW of appearance was related to higher rates of alcohol, cigarette, marijuana, and other illicit drug use among female students, and alcohol and marijuana use among male students. The external CSW of others’ approval was related to higher alcohol use among female students. This finding suggests that those who possessed fragile, appearance-based self-worth were dependent upon external validation and thus were vulnerable to threatened egotism as they felt judged by others on the basis of superficial characteristics. This may have resulted in a negative self-relevant affect that then led those individuals to resort to substance use to cope with such affect and negative feelings about themselves (Luhtanen & Crocker, 2005).

In contrast, internal contingencies of God’s love and virtue were related to lower rates of substance use for both male and female students. More specifically, there was evidence that basing one’s self-worth on God’s love or virtue was a protective mechanism against alcohol, cigarette, marijuana, and other illicit drug use among female students, whereas it protected male students from using cigarette, marijuana, and other illicit drug. This finding suggests that virtue and religious faith served as more stable and internally based self-worth contingencies that were not easily influenced by others or situations, and were related to lower levels of substance use among college students. Given that excessive substance use or illicit drug use are generally viewed negatively, individuals whose self-worth feelings are staked on religious beliefs or on being a virtuous (moral, principled) person are more likely to refrain from or limit substance use to protect their self-esteem (Luhtanen & Crocker, 2005). This study’s findings expand previous research by illuminating differential associations between the CSW dimensions and different types of substance use.

Some limitations of this study should be noted. First, by only using retrospective self-reports as a means for gathering data on maltreatment histories, the data were subject to selective memory and biased reporting. Future studies need to consider including other means of verifying the childhood maltreatment experiences reported (e.g. Child Protective Service records). A second limitation is that the sample consisted of college students. Replication with more diverse populations is essential to assure generalizability of the findings. Finally, the current data were cross-sectional and thus directionality in the relationship between CSW and substance use cannot be verified. However, there is evidence that CSW was related to changes in college students’ alcohol use (e.g., Luhtanen & Crocker, 2005). A prospective longitudinal study would add substantially to the understanding of the causal mechanisms in the link between CSW and substance use.

Investigating the processes by which childhood maltreatment experiences are related to later development outcomes will advance our knowledge regarding the factors that are involved in the development of maladaptation and psychopathology. The current findings emphasize the important role of CSWs in the link between maltreatment experiences and health risk behaviors. By illustrating the mediating role of CSWs in linking childhood maltreatment experiences to substance use among young adults, this study’s findings offer valuable insights for successful intervention strategies to individuals with substance use problems.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (K01-MH068491).

Contributor Information

Jungmeen Kim, Assistant Professor of Psychology at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg, VA..

Sarah Williams, graduate student in the Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences, University of Louisville, Louisville, KY..

References

- Arata CM, Langhinrichsen-Rohling J, Bowers D, O'Farrill-Swails L. Single versus multi-type maltreatment: An examination of the long-term effects of child abuse. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma. 2005;11(4):29–52. [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL. Amos 7.0 Updated to the Amos User’s Guide. Chicago: Small Waters Corporation; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Armor DJ, Polich JM. Measurement of alcohol consumption. In: Pattison EM, Kaufman E, editors. Encyclopedic handbook of alcoholism. New York: Gardner Press; 1982. pp. 72–81. [Google Scholar]

- Bierman A. The effects of childhood maltreatment on adult religiosity and spirituality: Rejecting God the father because of abusive fathers? Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2005;44:349–359. [Google Scholar]

- Bolger KE, Patterson CJ, Kupersmidt JB. Peer relationships and self-esteem among children who have been maltreated. Journal of Child Development. 1998;69(4):1171–1197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TN, Schulenberg J, Bachman JG, O'Malley PM, Johnston LD. Are risk and protective factors for substance use consistent across historical time?: National data from the high school classes of 1976 through 1997. Prevention Science. 2001;2(1):29–43. doi: 10.1023/a:1010034912070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burwell R, Shirk SR. Self processes in adolescent depression: The role of self-worth contingencies. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2006;16:479–490. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Lynch M. Failures in the expectable environment and their impact on individual development: The case of child maltreatment. Developmental Psychopathology: Risk, disorder and adaptation. 1995;2:32–71. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA. The role of self-organization in the promotion of resilience in maltreated children. Development and Psychopathology. 1997;9:797–815. doi: 10.1017/s0954579497001442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA. Psychopathology as risk for adolescent substance use disorders: A developmental psychopathology perspective. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1999;28(3):355–365. doi: 10.1207/S15374424jccp280308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA. A developmental psychopathology perspective on adolescence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70(1):6–20. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.1.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Toth SL. Child maltreatment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2005;1:409–438. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark DB, Thatcher DL, Maisto SA. Adolescent neglect and alcohol use disorders in two-parent families. Child Maltreatment. 2004;9(4):357–370. doi: 10.1177/1077559504269533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crocker J. The costs of seeking self-esteem. Journal of Social Issues. 2002;58(3):597–615. [Google Scholar]

- Crocker J, Luhtanen RK, Cooper ML, Bouvrette A. Contingencies of self-worth in college students: Theory and measurement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;85(5):894–908. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.5.894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crocker J, Wolfe CT. Contingencies of self-worth. Psychological Review. 2001;108(3):593–623. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.108.3.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Pettit GS, Bates JE. How the experience of early physical abuse leads children to become chronically aggressive. In: Cicchetti D, Toth S, editors. Rochester Symposium on Developmental Psychopathology: Vol. 8. The effects of trauma. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press; 1997. pp. 263–268. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Hotaling GT, Lewis IA, Smith C. Sexual abuse and its relationship to later sexual satisfaction, marital status, religion, and attitudes. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1989;4:379–399. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer KW, Ayoub C. Affective splitting and dissociation in normal and maltreated children: Developmental pathways for self in relationships. In: Cicchetti D, Toth S, editors. Disorders and dysfunctions of the self. Rochester Symposium on Developmental Psychopathology. Vol. 5. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press; 1994. pp. 149–222. [Google Scholar]

- Gibb BE, Alloy LB, Abramson LY, Rose DT, Whitehouse WG, Donovan, et al. History of childhood maltreatment, negative cognitive styles, and episodes of depression in adulthood. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2001;25:425–446. [Google Scholar]

- Glindemann KE, Geller ES, Fortney JN. Self-esteem and alcohol consumption: A study of college drinking behavior in a naturalistic setting. Journal of Alcohol and Drug Education. 1999;45(1):60–71. [Google Scholar]

- Granqvist P, Dickie JR. Attachment and Spiritual Development in Childhood and Adolescence. In: Roehlkepartain EC, King PE, Wagener LM, editors. The handbook of spiritual development in childhood and adolescence. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2005. pp. 197–210. [Google Scholar]

- Hall TA. Spiritual effects of childhood sexual abuse in adult Christian women. Journal of Psychology and Theology. 1995;23:129–134. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison PA, Fulkerson JA, Beebe TJ. Multiple substance use among adolescent physical and sexual abuse victims. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1997;21(6):529–539. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(97)00013-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harter S. The effects of child abuse on the self-system. Journal of Aggression Maltreatment, & Trauma. 1998;2:147–169. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins D, McCabe M. Multiple forms of child abuse and neglect: Adult retrospective reports. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2001;6:547–578. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy P, Drebing CE. Abuse and religious experience: A study of religiously committed evangelical adults. Mental Health, Religion and Culture. 2002;5:225–237. [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Cicchetti D. A longitudinal study of child maltreatment, mother-child relationship quality and maladjustment: The role of self-esteem and social competence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2004;32(4):341–354. doi: 10.1023/b:jacp.0000030289.17006.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Cicchetti D. Longitudinal trajectories of self-system processes and depressive symptoms among maltreated and nonmaltreated children. Child Development. 2006;77(3):624–639. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00894.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliewer W, Murrelle L. Risk and protective factors for adolescent substance use: Findings from a study in selected Central American countries. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2007;40(5):448–455. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.11.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight JR, Wechsler H, Kuo M, Seibring M, Weitzman ER, Schuckit MA. Alcohol abuse and dependence among U.S. college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63(3):263–270. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labouvie EW, McGee CR. Relation of personality to alcohol and drug use in adolescence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1986;54:289–293. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.54.3.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luhtanen RK, Crocker J. Alcohol use in college students: Effects of level of self-esteem, narcissism, and contingencies of self-worth. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19(1):99–103. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.1.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS, Cicchetti D, Becker B. The construct of resilience: A critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Development. 2000;71(3):543–562. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantel N, Fleiss J. Minimum expected cell size requirements for the Mantel-Haenszel one-degree-of-freedom chi-square test and a related rapid procedure. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1980;112(1):129–134. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGee R, Williams S. Does low self-esteem predict health compromising behaviors among adolescents? Journal of Adolescence. 2000;23:569–582. doi: 10.1006/jado.2000.0344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGee RA, Wolfe DA, Wilson SK. Multiple maltreatment experiences and adolescent behavior problems: Adolescents' perspectives. Development and Psychopathology. 1997;9:131–149. doi: 10.1017/s0954579497001107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller L, Davies M, Greenwald S. Religiosity and substance use and abuse among adolescents in the National Comorbidity Survey. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39(9):1190–1197. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200009000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran PB, Vuchinich S, Hall NK. Associations between types of maltreatment and substance use during adolescence. Journal of Child Abuse and Neglect. 2004;28:565–574. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullen PE, Martin JL, Anderson JC, Romans SE, Herbison GP. The long-term impact of the physical, emotional, and sexual abuse of children: A community study. Journal of Child Abuse and Neglect. 1996;20(1):7–21. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(95)00112-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pullen LM. The relationships among alcohol abuse in college students and selected psychological/demographic variables. Journal of Alcohol and Drug Education. 1994;40(1):36–50. [Google Scholar]

- Pyszczynski T, Greenberg J, Goldenberg J. Freedom in the balance: On the defense, growth, and expansion of the self. In: Leary M, Tangney J, editors. Handbook of self and identity. New York: Guildford Press; 2003. pp. 314–343. [Google Scholar]

- Rich DJ, Gingerich KJ, Rosen LA. Childhood emotional abuse and associated psychopathology in college students. Journal of College Student Psychotherapy. 1997;11(3):13–28. [Google Scholar]

- Sargent JT, Crocker J, Luhtanen RK. Contingencies of self-worth and depressive symptoms in college students. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2006;25(6):628–646. [Google Scholar]

- Trickett PK, McBride-Chang C. The developmental impact of different forms of child abuse and neglect. Developmental Review. 1995;15:311–337. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace JM, Brown TN, Bachman JG, Laveist TA. The influence of race and religion on abstinence from alcohol, cigarettes and marijuana among adolescents. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2003;64(6):843–848. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA. Self-esteem and perceived control in adolescent substance use: Comparative tests in concurrent and prospective analyses. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1994;8(4):223–234. [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Yaeger AM, Sandy JM. Buffering effect of religiosity for adolescent substance use. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2003;17(1):24–31. doi: 10.1037/0893-164x.17.1.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]