Abstract

Scholars have recently become increasingly interested in the role religion plays in the responses to the HIV/AIDS epidemic in sub-Saharan Africa. Here, we present the Malawi Religion Project (MRP), which provides data to examine the relationship between religion and HIV/AIDS through surveys and in-depth interviews with denominational leaders, congregational leaders, and congregation members in three districts of rural Malawi. In the paper, we outline existing perspectives on the religion-HIV/AIDS link, describe the MRP’s design, implementation, and subsequent data; provide initial evidence for a series of general research hypotheses; and describe how these data can be used both to extend explorations of these relationships further and as a model for gathering similar data in other contexts. In particular we highlight the unique possibilities this project provides for analyses that link MRP data to the Malawi Diffusion and Ideational Change Project. These linked data produce a multi-level data set covering individuals, congregations and their communities, allowing empirical research on religion, HIV/AIDS risk, related behaviors, attitudes, and norms.

1. Introduction

Demographers and health policy experts have long recognized the important role of local institutions in engaging salient population and health issues worldwide. Across sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), international efforts to promote family planning, distribute mosquito nets, reduce infectious disease, and combat the spread of HIV and AIDS have mobilized the potential of schools, local clubs, and religious organizations. Despite widespread recognition that religion is a critical aspect of societies in SSA with profound implications for health in this part of the world (Feierman 1985; Oosthuizen 1992), empirical investigations of the impact that religious organizations have in efforts to respond to the HIV/AIDS epidemic in SSA have been scant.

Ideologically-charged discourse on the role religious congregations hold for AIDS in SSA has been plentiful (Ahiante 2003; Green 2003; Kuphunda 2003; Pisani 1999; World Bank 1997), while even-handed, empirically-based assessments of their activities and relevance for AIDS-related outcomes has been limited (for a few exceptions, see Agadjanian 2005; Garner 2000; Lagarde et al. 2000; Takyi 2003). The existing empirical studies of religion and HIV provide important ideas of possible pathways through which religion may be linked to HIV outcomes: via broad-scoped comparisons of associations at country (Garner 2000) or denomination-level (Takyi 2003), the relationship between individuals’ religious affiliation or participation and subsequent HIV-related attitudes and behaviors (Lagarde et al. 2000), and describing leadership activities in prevention and care (Trinitapoli 2006). However, no previous data has combined the ability to examine a broad range of religious communities’ HIV-related activities with the capacity to then link the individuals who participate in those organizations to examine the organizations’ influence on participants’ HIV-related behaviors and outcomes.

This paper describes the background, methods, and selected results from the Malawi Religion Project (MRP) – an effort to systematically study the AIDS-related activities of religious congregations in three districts of rural Malawi. Recognizing both the contributions and limitations of studies that have documented the AIDS-related activities of particular African congregations through ethnography and small-scale studies of congregations belonging to the same religious tradition, the MRP capitalizes on innovations in the sociological study of organizations in both theoretical and methodological terms. This provides data that are equally relevant to scholars of religion in Africa and those interested in the role of religion for shaping key demographic processes. Finally, the MRP provides a model for adding a culturally informed ecological component to an ongoing large-scale demographic survey project. The possible applications of this successful partnership are not only relevant for advancing the study of religious organizations in various parts of the world, but can also be translated to examine the role of any type of localized social institution that may be shaping crucial demographic behaviors and outcomes.

2. Background – Religion and HIV/AIDS

Previous research identifies three types of religious organizations thought to influence the behavior of individuals: congregations, denominational organizations, and religious non-profits (Chaves 2002). Worldwide, religious NGOs and denominational organizations tend to be concentrated in cities, making congregations – the level of participation for most individuals – the natural focal point for a study on religious organizations in a rural area like Malawi. Following the US National Congregations Study, which has paved the way for innovative thinking about the systematic study of congregations on a large scale, we define congregations as “the relatively small-scale, local collectivities and organizations in and through which people engage in religious activity….” (Chaves et al. 1999: 458).

Organizational behavior scholars emphasize the cultures and leadership norms in which organizations operate. This is precisely how the MRP seeks to locate congregations—as organizations that display distinctive cultures and norms (e.g., expectations of congregants’ social, religious, and sexual attitudes and behaviors), yet themselves operate within a larger village normative climate, and perhaps even a climate characterizing a set of villages or an entire district. The presence of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in Malawi, marked by frequent funerals, has led to intense discussions in local networks about possible ways to avoid infection (Watkins 2004). Behavioral changes, however, do not occur within a normative vacuum. There are myths (i.e., stories) and rituals that guide how collectivities adapt to external constraints (Meyer and Rowan 1977). In rural Malawi, where the epidemic has confronted congregations and their leadership, religious leaders look to national denominational leaders for guidance in assessing competing claims (e.g., use condoms, avoid bar girls, etc.) and, in turn, interpret such proposed solutions within the constraints of local norms. Thus, whenever there is widespread organizational ambiguity and uncertainty—and the AIDS crisis clearly provides this—it is likely that local as well as regional and denominational norms guide how congregations respond to the crisis.

In the remainder of this section we outline the general hypotheses that guided the design of the MRP; followed with a detailed description of the MRP; then several preliminary analyses of these data, providing suggestive evidence regarding these hypotheses. From these, we hope to push the discussion about the link between religion and HIV/AIDS in a direction that will encourage in-depth exploration of more nuanced propositions than the broad strokes often required by the scope of the questions previously addressed. In our description of the MRP, we will highlight some of the ways we (and hopefully others) will use these data to address these questions. We also describe several ways that lessons learned from the MRP can inform other researchers interested in gathering culturally relevant data to address similar questions in other contexts.

2.1 How religious leaders engage the epidemic

Based on previous research and a wealth of anecdotal evidence, we expect to find that religious leaders in Malawi are active in engaging the AIDS epidemic (Trinitapoli 2006) – one of the most serious problems currently facing their communities. We expect the messages religious leaders give on the topic to be situated within the overall framework of the ABC campaign: Abstain from sex, Be faithful, use Condoms – that has dominated HIV prevention efforts across SSA. However, we also expect that congregations and their leaders may vary in significant ways on a set of key characteristics that influence responses to the epidemic.

Institutional practices range from tithing to the provision of services, such as organized care of the sick or “funeral committees” to help the families of the deceased, and from individual activities of confession and penance (e.g., in Catholic churches) to public expressions of solidarity such as healing ceremonies. The MRP is designed to examine mechanisms for social support and social control that other scholars have suggested may be particularly important in shaping responses to the epidemic, and to identify other prevention strategies religious leaders are promoting. In other words, while the ABC campaign guides prevention efforts, we hypothesize that the ABCs of HIV prevention are far from exhaustive in terms of understanding the steps individuals in this context actually take to avoid infection and the advice they give to others for doing the same. Likely localized in nature, alternate prevention strategies are, by definition, culturally appropriate ones, thus, the people for whom they are intended may more readily adopt them.

Social control mechanisms include practices like sanctioning members who deviate from doctrines; social support mechanisms include both group prayers for those attempting to resist temptation as well as activities to support those affected by AIDS. The effectiveness of these mechanisms of social support and social control is likely to vary depending on the extent to which members of a congregation are “channeled” into more — or less — exclusive and overlapping sets of relationships within the congregation; relationships that may augment or replace social networks based on extended family, clan, or ethnicity (Mkandawire 2000; Stark and Finke 2000). By “channeling” members into congregational activities (e.g., Bible Study, prayer groups, committees to care for orphans), congregations also increase the density of personal networks and, in turn, the social support of (and social control over) its members (Ellison and George 1994). Without the support of a tight-knit congregation, the influence of individuals’ own religious commitments or moral proscriptions on their personal behavior – so the “moral communities” thesis argues – becomes weak (Stark 1996). Evangelical churches may be distinctive in this sense. Their absorptive pattern has been described in Zimbabwe, where with conversion “the new focus of the believer’s social life becomes the church: an unending round of Bible studies, prayer meetings, choir practices and concerts, revivals, evangelistic activities, weddings,” and the church becomes the believer’s extended family as ties based on kinship diminish (Maxwell 1998: 353–355). Interestingly, an important study of social networks in religious organizations in Mozambique found that doctrines regarding family life did not differ across denominations, but the characteristics of interpersonal networks based in the individual congregations did (Agadjanian 2001).

Hypothesis 1a: African religious leaders are actively engaging the AIDS epidemic.

Hypothesis 1b: AIDS activism on the part of religious leaders is guided by the tenants of the ABC campaign.

Hypothesis 1c: African religious leaders are also engaging the AIDS epidemic in other, localized ways that are currently unknown to researchers.

2.2 How religious networks shape leaders’ HIV-related strategies

The potential of congregational efforts to combat HIV/AIDS may also be facilitated or hindered by links to national and international denominations. For example, financial support may enable poor rural congregations to develop programs for caring for orphans or “Say No to AIDS” clubs for youth, or to send leaders and elders to national meetings where they are exposed to the hierarchy’s views on AIDS prevention and mitigation. Pentecostal and evangelical Protestant religious organizations in Africa are noted for their international networks (Englund 2003; Hearn 2002), and the recent construction of numerous mosques in Malawi has been funded by governments and individuals in the Arabian Peninsula (Fiedler 2004a; Fiedler 2004b). Such wider networks may, however, be accompanied by denominational officials invested in maintaining doctrinal purity – for example in intolerance of condom use, polygamy, or marital infidelity – and sanction church leaders who stray from official positions. These networks may embed a congregation within a strong hierarchy with particular doctrinal systems that discourage prevention behaviors such as condom use, or one that mandates that local leaders focus exclusively on prohibiting extramarital sex in order to reduce the spread of HIV. However, the remote rural setting of Malawi imposes acute geographical constraints on these networks, limiting opportunities to cultivate external contacts (e.g., denominational leaders and partners, NGO officials and functionaries, etc.) and, presumably, their influence. The existing literature and available data have been simply unable to explore the precise nature of these organizational relationships; the design of the MRP aims to fill that void.

Hypothesis 2: The social networks of religious leaders influence both the extent to which they are involved in HIV prevention and the types of strategies they prioritize.

2.3 From organizational strategies to individual behavior and outcomes

By combining congregational network data with the existing individual level data from the MDICP and data from national level denomination leaders, the MRP features a unique multi-level design that allows researchers to assess coherence of prevention messages across levels of these traditions, as well as examine the differences across various traditions. Among the most promising capabilities of the MRP is the ability to connect congregation and individual level data to assess the strength of associations between formal messages, informal practices, and network size, shape, and strength to the reported AIDS-related behaviors of individuals. We expect to find both that the attitudes and activities of religious leaders matter for members (Lagarde et al. 2000; Trinitapoli and Regnerus 2006), and that some activities are more relevant than others.

Hypothesis 3: The AIDS-related strategies religious leaders promote are relevant for the behaviors of individual members.

3. Project setting

Malawi is a small country in eastern Africa, which has a population of about 12 million, of which nearly 70% live in rural areas. Malawi is a religiously diverse country, its AIDS epidemic is typical of the rest of the region, and religious congregations are a central component of rural life. These factors make rural Malawi an ideal setting for examining the role of religious organizational networks in responding to the AIDS crisis more closely. Like much of the “AIDS-belt” in SSA, the HIV epidemic in Malawi is a generalized one and is marked by frequent perinatal transmission (UNAIDS 2006a), heterosexual contact as the primary route of infection (Schmid et al. 2004), and prevalence estimates suggesting that women are increasingly disproportionately infected (Glynn et al. 2001). Estimates suggest that approximately 14.1% of Malawi’s adult population is infected, with prevalence rates having stagnated since 2000 (NAC 2004; NSO 2005; UNAIDS 2006b; UNAIDS 2007). There is wide variation in HIV prevalence across testing sites (from 2.9% to 35.5%), with urban areas and the south featuring the highest prevalence rates (NAC 2004). This suggests that some areas have been more successful in avoiding HIV than others, but explanations for these differences remain scant.

Figures for Malawi from the World Christian Encyclopedia (Barrett, Kurian and Johnson 2001) estimate that 77% of the population is Christian, 15% Muslim, and most of the remaining 8% practice traditional African religions. Malawi differs only slightly from neighboring countries in its proportion of Christians (e.g., 82% in Zambia, 83% in South Africa), and the proportion of the population who are Muslim is within a similar range (e.g., 10 % in Kenya, 20 % in Tanzania). The major Christian denominations as a percentage of the total Christian population are Roman Catholics (25%), mission Protestants (20%), and African Independent Churches or AICs (17%); groups like evangelicals and Pentecostals are rapidly growing in Malawi, particularly in urban areas, and together account for about 32% of the country’s Christians (Jenkins 2002).

3.1 The Malawi Diffusion and Ideational Change Project

The Malawi Religion Project, described here, is a sister project to the Malawi Diffusion and Ideational Change Project (MDICP). The MDICP is an ongoing longitudinal household survey that examines how ideation, behavior, and risk are shaped through informal discussion networks. These data focus on three distinct rural districts of Malawi: Balaka in the south, Mchinji in the central region, and Rumphi in the north. The MDICP had been initially designed to examine two key empirical questions: the role of social interactions in (1) the acceptance (or rejection) of modern contraceptive methods and of smaller ideal family size; and (2) the diffusion of knowledge of AIDS symptoms and transmission mechanisms and the evaluation of acceptable strategies of protection against HIV. While the MDICP sample was intended to represent the populations in the three sampled regions, and not necessarily all of Malawi, it does closely resemble one nationally representative sample – the Malawi Demographic and Health Survey (MDHS) (NSO 2005) – on several key factors such as age, education, and select indicators of socioeconomic status (Anglewicz et al. 2009; Watkins and Warriner 2003).

Drawn from 119 rural villages, the sample includes roughly 1500 ever married women and 1000 of their spouses in each of the interview years (1998, 2001, 2004, and 2006). Researchers have shown favorable evaluation of these data’s reliability, attrition, and representativeness (Anglewicz et al. 2009; Bignami-Van Assche, Reniers and Weinreb 2003; Watkins and Warriner 2003; Watkins et al. 2003). Analyses of the MDICP data have been used to describe numerous HIV-related issues in Malawi, such as risk perception (Behrman, Kohler, and Watkins 2007; Bignami-Van Assche et al. 2007; Helleringer and Kohler 2005), related behaviors (Kaler 2004; Trinitapoli and Regnerus 2006), infection rates (Obare 2005; Obare et al. 2008), and care giving (Chimwaza and Watkins 2004).

3.2 Religion in the MDICP

Previous work using MDICP data has shown high levels of religious participation in Malawi (Trinitapoli and Regnerus 2006). The survey instrument in Wave III (2004) of the MDICP included an expanded set of measures to more accurately capture the shape of religious life in rural Malawi, and important variations within it. At the same time, the MDICP team fielded two pilot studies aimed at developing better understandings of religion in Malawi by focusing on the organizational level. The survey team piloted a questionnaire to a non random sample of 60 religious leaders in the central district, and conducted participant observations known as ‘sermon reports’ in 116 religious services – 68 in the southern district, and 48 in the north (Trinitapoli 2006). These various data resources have been used to explore individual level models of religion and HIV-related behaviors and outcomes (see section 5.3 below), and were vital for informing the design of the Malawi Religion Project.

4. The Malawi Religion Project design

Based on findings from these pilot projects, the Malawi Religion Project (MRP) was subsequently planned as a large-scale cross sectional, mixed methods data collection project. The principal aim of the MRP is to collect data on religious organizations in order to examine how, as “moral communities,” these organizations influence responses to the epidemic in a sub-Saharan African country with a major HIV/AIDS epidemic. The data collection during summer 2005 included four primary target populations: leaders of local congregations, local congregation members, national level denomination leaders, and leaders of NGOs active in the three sample areas.

4.1 MRP congregation leaders

The MRP’s design is based on a strategy known as hypernetwork sampling (Chaves et al. 1999; McPherson 1982; Spaeth et al. 1996), which asserts that a random sample of organizations can be derived by listing the organizational affiliations of a random sample of individuals and sampling from the list of named organizations. In Wave III of the MDICP (2004), all respondents were asked to report the name of the congregation they currently attend, the name of its leader, and provide a general description of its location. Defining the sample of congregations was a complex process, since congregations in rural Malawi are frequently hard to identify. Virtually none have a sign bearing the congregation’s name, and many do not meet in their own building at all. It is common, for example, for congregations either to share a building with other congregations or to not have a building. In one of the sites, three established congregations had been meeting under a tree for several years. Congregations are often known by several names (including, but not limited to, the name of the village, the name of the current leader, or the name of the founding leader or mission). As such, the research team refined the congregation list in a multi-stage approach.

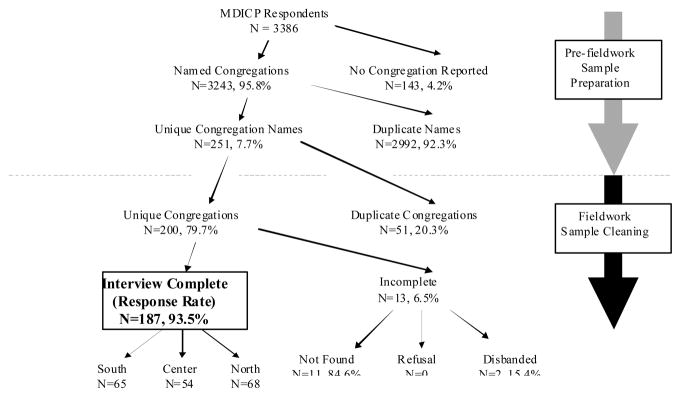

Of the 3386 respondents asked to name the religious congregations in which they regularly participate, 3243 provided valid data on this question. The research team identified all different spellings and similar names within this initial list of congregations, reducing the list to 251 potential unique congregations. This list was then discussed in the field daily by the research team, interview supervisors, interviewers, and scouts (hired locals with intimate knowledge of the research area) to further clarify additional multiple namings or hard-to-identify congregations. Rather than sampling from the list of congregations generated by this procedure, as other studies have done (Chaves 1998; Spaeth et al. 1996), the MRP’s target sample included all the congregations MDICP respondents reported attending (N=200 unique congregations). The research team successfully located and completed surveys and in-depth interviews with leaders for 93.5% of these congregations (N=187, see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

MRP congregations: Sample description

All MRP interviews were conducted in the local language by trained interviewers who were hired in each of the sample locations. The national language of Malawi is Chichewa, however many of the interviews in the south were conducted in Chiyao, and in the north all interviews were conducted in the local language of Chitumbuka. Daily debriefing meetings between the interviewers, interview supervisors, and project coordinators were crucial to the success of this project. The immediate and thorough evaluation of each transcript, as soon as it was completed, allowed the interviewers to conduct callback interviews as necessary when portions of the interview were either not covered, or lacking in sufficient detail.

4.1.1 Surveys with congregation leaders

Each congregation leader participated in a structured interview, completing a 12-page questionnaire that covered six key areas. We asked each leader about (1) what they believe the Bible (or Koran) has to say – if anything – about the HIV/AIDS crisis; (2) the number and types of venues congregation members had for interaction on AIDS-related issues – such as prayer meetings, Bible studies and committees; (3) the impact of AIDS on the congregation (e.g. estimates of AIDS-related deaths among members, estimates of the burdens of care for orphans and the sick by congregation members); and (4) a battery of questions on AIDS-related attitudes and behavior. Utilizing questions that were identical to those included in MDICP-3 allows us to compare leaders’ views with those of their congregation members.3 While this focus on HIV/AIDS is central to the aims of the MRP, the survey also covered several other issues. These focused on (5) the characteristics of the religious organization (e.g., number, gender, and age composition of the membership, the governance of the congregation, sources of income, formal and informal organizational networks); (6) some basic background characteristics of the religious leaders themselves (e.g., age, schooling, basic economic indicators, etc.).

Table 1 relies on these survey data to provide an overview of the religious congregations in the three MRP sample districts. Of the research sites, the southern district has the densest population and is also the most religiously dense, containing almost 40% of the MRP congregations, while just under 30% are located in the central district. The denominational breakdown of the MRP congregations loosely reflects the religious composition of the MDICP, with a few key differences. Since mosques and Catholic churches tend to be larger in size than congregations of other religious traditions, the numerous Muslims and Catholics in the MDICP attend a comparatively small number of mosques and Catholic parishes. African Independent (AIC) and mission Protestant congregations tend to be small and are therefore the most numerous leaders among MRP respondents.

Table 1.

Descriptive overview of religious congregation characteristics (MRP, 2005)

| Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| District | ||||

| Balaka (south) | 0.39 | 0 | 1 | |

| Mchinji (center) | 0.29 | 0 | 1 | |

| Rumphi (north) | 0.37 | 0 | 1 | |

| Denomination | ||||

| Catholic | 0.11 | 0 | 1 | |

| Pentecostal | 0.17 | 0 | 1 | |

| African Independent | 0.20 | 0 | 1 | |

| Muslim | 0.12 | 0 | 1 | |

| Mission Protestant | 0.21 | 0 | 1 | |

| New Mission Protestant | 0.18 | 0 | 1 | |

| Congregational Demographics | ||||

| Congregation Size | 37.39 | 52.81 | 0 | 370 |

| Congregation Age (in years) | 22.12 | 19.79 | 1 | 91 |

| Leader has at least Some Secondary Education | 0.29 | 0.45 | 0 | 1 |

| Leader has Some Religious Training | 0.63 | 0.48 | 0 | 1 |

| Network Ties | ||||

| Helped by NGO | 0.13 | 0.34 | 0 | 1 |

| Ever Visited by Missionaries | 0.37 | 0.48 | 0 | 1 |

| Helped by Mission Work | 0.24 | 0.43 | 0 | 1 |

| Ever Visited by Denominational Leaders | 0.65 | 0.48 | 0 | 1 |

| Isolated Congregation a | 0.23 | 0.42 | 0 | 1 |

| AIDS | ||||

| Leader has Attended AIDS Workshop | 0.47 | 0.50 | 0 | 1 |

| In this Congregation, AIDS is: | ||||

| Not a Problem (0) | 0.11 | 0 | 1 | |

| Somewhat of a Problem (1) | 0.27 | 0 | 1 | |

| A Big Problem (2) | 0.36 | 0 | 1 | |

| The Single Biggest Problem (3) | 0.26 | 0 | 1 | |

| N=187 | ||||

Note: All numbers in Column 1 are mean values.

Congregation has never been visited by any representatives of NGOs, their denomination or the government.

Some other features of the congregations are worth noting: On average, MRP congregations have just fewer than 40 members and have been in existence for over 20 years. While few religious leaders have received any secondary education, over 60% report having attended some type of religious training, such as a Bible workshop or Madrassa. Many congregations have been visited by a denominational leader at some point, but few have been visited or helped by missionaries or NGO leaders, and almost a quarter of the congregations in our sample can be considered “isolated” congregations – never having been visited by any NGO or government leader, denominational authority, or missionary. In contrast, almost half of the religious leaders in this part of the world have ever participated in an AIDS workshop. Just over a quarter report that AIDS is the single biggest problem facing their congregation. Many leaders ranked poverty, poor conditions of the church building, orphans, and transportation difficulties – with members walking long distances to attend weekly services, sometimes in heavy rains – ahead of AIDS when asked about their most pressing troubles. Finally, the content of religious services as reported by the leaders deserves mention. An overwhelming majority of religious leaders in the MRP sample report discussing sexual morality and AIDS on a weekly or almost weekly basis. Only the topic of “morality”, generally speaking, was more common than these two topics, with general messages about illness only slightly less common.

4.1.2 MRP network data

One of the MRP’s primary aims is to inquire into the relationships congregations have with other congregations, larger denominational organizations, and the few other formal organizations that do exist in these rural settings. Previous research suggests that these intra organizational relationships are meaningful for shaping congregational responses to the present HIV epidemic, but the specifics of the relationships are difficult to hypothesize. For example, Catholic parishes in Malawi may not be equally resistant to condom use as a method of HIV prevention, despite denominational edicts forbidding their use. Congregations with close ties to the archdiocese may be especially unlikely to promote condoms, while a nearby Catholic parish that is run by a lay person, visited only bi-annually by a local priest, and has no ties to Church hierarchy, may deal with condoms quite differently.

The survey and interview data from MRP congregation leaders explicitly gathered data on networks, collecting information about the connections between the sample congregations and (a) other congregations (whether within or outside their own denomination), (b) their denominations, and (c) other community organizations (e.g., NGOs). Using an open-list format, leaders list names of individuals with whom they have contact in separate modules: personal friendship networks, individuals with whom they discuss “issues of religious belief or church doctrine,” and individuals with whom they discuss topics pertaining to HIV/AIDS. We also asked leaders and members specifically about congregational activities that involved cooperation across religious organizations – things such as joint services, revivals or choir festivals.

In addition to network components of the survey, we also coded all in-depth interview transcripts (member, congregational leaders, and national leaders) to identify additional network ties.4 The network information derived from these qualitative interview sections provide an opportunity for the respondents’ most salient relationships to be identified as network nominations, rather than relying solely on the research teams’ preconceived notions of what constitutes relevant ties. Listing network ties this way produces ego-network data, but the additional information provided for each contact (almost always the partner’s position and the organization they lead, and sometimes the contact’s name) allowed for these ties to be connected into (nearly) complete networks representing friendships, doctrinal conversations, and HIV/AIDS conversations in each of the three sample sites.5

Table 2 highlights the network partnerships that congregational leaders report drawing on when developing messages for their congregations – separately for general doctrinal and HIV-specific messages. This table demonstrates that local connections are relatively common (e.g., ties to other congregational leaders and local villagers), while relationships with representatives located outside of the local context (e.g., denominational or NGO officials) are comparatively infrequent. These locational differences are true both for discussions regarding general religious topics as well as for relationships specifically covering issues related to HIV/AIDS.

Table 2.

Religious leaders’ discussion partners (MRP, 2005)

| Has Tie Type | Mean # of Partners | Std. Dev. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Leader has discussions about Doctrine with | |||

| Anyone (outside the congregation) | 0.86 | ||

| Other Villagers | 0.57 | 1.5 | 1.7 |

| Congregational Leaders | 0.61 | 1.4 | 1.6 |

| Denominational Leaders | 0.45 | 1.0 | 1.4 |

| NGO Officials | 0.15 | 0.3 | 0.9 |

| Leader has discussions about HIV/AIDS with | |||

| Anyone (outside the congregation) | 0.72 | ||

| Other Villagers | 0.61 | 1.7 | 1.8 |

| Congregational Leaders | 0.53 | 1.5 | 1.4 |

| Denominational Leaders | 0.44 | 0.9 | 1.2 |

| NGO Officials | 0.22 | 0.4 | 0.8 |

| N=187 | |||

Note: All numbers in Column 1 represent the proportion of leaders who report at least one partner of each specified type. The mean value (Column 2) and standard deviation (Column 3) refer to how many of the specified tie type the leader reports.

4.1.3 In-depth interviews with congregation leaders

The survey instrument was similar to a traditional survey but also included a number of suggested probes near relevant survey questions throughout the questionnaire, and additional in-depth interview questions. These additional in-depth interview sections addressed four main themes: the leader’s personal religious history, a description of the congregational leadership and its history, recounting any major problems faced by the congregations, and (if it had not already been extensively addressed in the other three qualitative sections or the survey) HIV/AIDS-related topics specifically. This format generated interviews that reflect what the religious leaders think is important about their congregations, villages, and religious communities. Unlike a traditional survey or interview, where the researchers’ agenda controls the conversation, this format allowed the respondents to tell us about their congregations, their religious beliefs and practices, and AIDS-related concerns in their own voices. These additional components of the conversation, along with the qualifications respondents attached to their survey responses, provide rich and unique data that is necessary for a richer description of variation across congregations and denominations than is possible on a survey alone. It also provided an opportunity for the research team to learn from and refine the development of survey instruments for use in future studies. These interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed in their entirety (including the survey portion to capture additional probes). For each of these religious leaders, the interview and survey was conducted in a single location, with the bulk of time devoted to the unstructured interviews.

4.2 Interviews with national religious leaders

In MRP interviews, each congregation reported their denominational affiliation. These were subsequently recoded into a set of six categories based on salient historical and contemporary distinctions (Steensland et al. 2000): Catholic, Muslim, Pentecostal, AIC, mission Protestant (including Presbyterian, Anglican, Baptist) and new mission Protestant (including Seventh Day Adventist, Church of Christ, Jehovah’s Witness).6 In the summers of 2005–06, MRP researchers approached the highest ranking official for each denomination represented in the MRP congregations. In total we conducted 48 interviews with 45 different leaders, representing 44 denominations or organizations. Where possible, the team interviewed the president (or equivalent; e.g., General Secretary, or director) of each denomination, and each of the main inter-denomination and interfaith organizations represented in Malawi. Several of the included denominations (e.g., CCAP, Church of Christ and New Apostles) do not have national level coordinating organizations, so we interviewed regional leaders (e.g., Synod General Secretary; N=7). In other cases where the president was not available (N=16), we interviewed vice presidents or department heads (e.g., HIV/AIDS coordinator). We successfully recruited at least one national level leader for all but one of the denominations represented in the MRP. These interviews were conducted in English by Malawian and American researchers. Table 3 summarizes the coverage by religious tradition, of the leaders represented in the MRP at both the national denominational and local congregational levels, along with the corresponding number of MDICP respondents from which these organizations were identified. The differences across these levels reflect substantial variations in congregational size across the various traditions (see discussion of Table 1 above).

Table 3.

Religious coverage: MDICP respondents (2004), congregation and national leader interviews (2005–06)

| Catholic | Pente-costal | African Independent | Muslim | Mission Protestant | New Mission Protestant | Other a | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MRP National Leaders | ||||||||

| Total | 2 | 6 | -b | 9 | 11 | 10 | 10 | 48 |

| 0.04 | 0.13 | 0.19 | 0.23 | 0.21 | 0.21 | |||

| MRP Congregational Leaders | ||||||||

| North | 5 | 18 | 17 | 2 | 12 | 17 | - | 71 |

| 0.07 | 0.25 | 0.24 | 0.03 | 0.17 | 0.24 | |||

| Center | 10 | 6 | 19 | 1 | 12 | 10 | - | 58 |

| 0.17 | 0.10 | 0.33 | 0.02 | 0.21 | 0.17 | |||

| South | 7 | 9 | 5 | 19 | 17 | 8 | - | 65 |

| 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.08 | 0.29 | 0.26 | 0.12 | |||

| Total | 22 | 33 | 41 | 22 | 41 | 35 | - | 194 |

| 0.11 | 0.17 | 0.21 | 0.11 | 0.21 | 0.18 | |||

| MDICP Respondents | ||||||||

| North | 126 | 126 | 279 | 6 | 337 | 153 | 3 | 1030 |

| 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.27 | 0.01 | 0.33 | 0.15 | 0.00 | ||

| Center | 279 | 32 | 199 | 11 | 253 | 205 | 5 | 984 |

| 0.28 | 0.03 | 0.20 | 0.01 | 0.26 | 0.21 | 0.01 | ||

| South | 136 | 44 | 24 | 735 | 77 | 44 | 1 | 1061 |

| 0.13 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.69 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.00 | ||

| Total | 541 | 202 | 502 | 752 | 667 | 402 | 9 | 3075 |

| 0.18 | 0.07 | 0.16 | 0.24 | 0.22 | 0.13 | 0.00 | ||

Notes: All numbers are frequency counts and row proportions.

The other category represents those who represent interfaith and inter-denominational religious organizations (for national leaders), and those individuals who reported no religious affiliation (for MDICP respondents).

For African Independent Churches, we were unable to identify the existence of any national level coordinating leaders. Combining the interviews with local leaders and our attempts to find such leaders, we believe this was not simply a failure to locate/recruit such leaders, but accurately reflects that these congregations do not have such positions, which is consistent with the organizational structure of AIC churches in Malawi.

The interviews with national leaders included five main sections: (1) the history of the religious organization in Malawi and an overview of its organizational structure; (2) doctrinal related issues, particularly those which are distinct to the particular denomination, compared to others in Malawi; (3) the intended and actual collaborations of the denomination with other organizations, including congregations within the denomination, other denominations, NGOs, government, and other international organizations; (4) a summary of the individual leader’s personal religious history; and (5) a discussion of some of the primary problems facing the denomination and how the organization attempts to resolve such problems, with a particular focus on how issues of HIV/AIDS are addressed.

4.3 Interviews with female congregation members

The data from congregation members was gathered through semi structured interviews from a stratified random sample of previous female MDICP respondents (N=110). Female respondents were stratified by congregation; from each congregation where more than 4 MDICP respondents reported attending, one woman was randomly selected to participate in the MRP’s in-depth interview. These interviews focused on five primary themes: personal religious history, congregational norms and discipline, HIV/AIDS, religion and HIV/AIDS, and family planning, with an added interest in the respondent’s outlook for the future in all of these areas. Pairing congregational leader data with congregational member data helps us compare perspectives and assess potential over-reporting among leaders of behaviors that may be socially desirable in this context, like preaching about AIDS, caring for orphans, or sponsoring micro-credit endeavors.

5. Preliminary findings

Early analyses of these data indicate the presence of wide gaps between national denominational authorities – to whom external intervention efforts are targeted – and the local congregation leaders who are often supposed to implement them (adams 2007). Despite these gaps, leaders are actively addressing HIV in these communities (Trinitapoli 2006), and these messages appear to have an influence over the AIDS-related behavior of individuals who hear them (Trinitapoli and Regnerus 2006). Below we present some descriptive findings from the components of the MRP data, which serve to (1) give a general idea of MRP data, (2) provide initial evidence for the hypotheses that guided the MRP design (described in Section 2), and (3) inform the construction of more specific hypotheses that these data can be used to answer. Further, while we are currently conducting (or plan to in the future) many of the analytic extensions these point to, we also acknowledge that Malawi is a single example of religious involvement in AIDS interventions in SSA. As such, we hope that these preliminary analyses can also be used to guide similar efforts – both in new data collection efforts and analytic strategies – in projects outside of Malawi.

5.1 Religious leader engagement

Table 4 presents an overview of the topics religious leaders in rural Malawi formally address in their weekly religious services, listed in the order of descending frequency. Over 88% of religious leaders report preaching about morality (generally) on a weekly basis, and over 70% report addressing sexual morality, AIDS, and illness (generally) on a weekly basis as well. Religious leaders in this region are much less likely to discuss political issues than health-related issues from the pulpit. The bivariate relationships reveal surprisingly few denominational differences in the overall messages about these topics, although there are differences in the frequency with which they are discussed. Leaders of Pentecostal churches are significantly less likely than mission Protestant and AIC leaders to frequently discuss AIDS from the pulpit. Catholic leaders are substantially less likely than leaders in other denominations to report frequently addressing death and the afterlife, but are the most likely to report discussing political issues with frequency.

Table 4.

Proportion of religious leaders who report addressing select issues

| General Morality | Sexual Morality | General Illness | AIDS | Death/Afterlife | Political Issues | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Catholic | 0.90 | 0.52 c,f | 0.62 | 0.67 | 0.38 b,d,e,f | 0.19 d,f |

| Pentecostal | 0.91 | 0.69 | 0.63 | 0.50 c,e | 0.84 a,c | 0.13 f |

| African Independent | 0.89 | 0.79 a | 0.79 | 0.79 b | 0.63 b | 0.11 |

| Muslim | 0.77 | 0.73 | 0.59 e | 0.73 | 0.73 a | 0.05 a |

| Mission Protestant | 0.90 | 0.75 | 0.78 d | 0.85 b | 0.70 a | 0.08 f |

| New Mission Protestant | 0.88 | 0.79 a | 0.74 | 0.74 | 0.76 a | 0.00 a,b,e |

| Total | 0.88 | 0.73 | 0.71 | 0.72 | 0.69 | 0.09 |

| N=187 | ||||||

Notes: Letters denote significant difference (p<0.05) from:

Catholics,

Pentecostals,

AICs,

Muslims,

Mission Protestants,

New Mission Protestants.

5.2 Networks

Table 5 depicts denominational differences in congregational leaders’ reported conversation partners for discussions specifically pertaining to HIV/AIDS. The vast majority (72%) of MRP congregational leaders are engaged in discussions of HIV-related topics with leaders of other organizations, and most (60%) of the nominated ties indicate these conversations take place specifically with other religious leaders.7 At each level of leadership, Muslim leaders are more isolated than their Christian counterparts with respect to the flow of AIDS-related information, raising important questions about the position of Muslims in diffusion processes that demographers have identified as crucial for conveying information about prevention and treatment.

Table 5.

Frequency of reporting AIDS-discussion partners, by religious tradition

| Any | Congregational Leaders | Denominational Leaders | NGO Officials | Other Villagers | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Catholic | 71 | 48 | 52 d | 33 d | 57 d |

| Pentecostal | 81 d | 59 d | 34 | 19 | 63 d |

| African Independent | 69 | 56 d | 50 d | 22 | 61 d |

| Muslim | 45 b,f | 23 b,c,e,f | 13 a,c,e,f | 5 a,e | 27 a,b,c,d,e |

| Mission Protestant | 70 | 55 d | 55 d | 33 d | 65 d |

| New Mission Protestant | 85 d | 67 d | 53 d | 22 | 78 d |

| Total | 72 | 53 | 44 | 22 | 61 |

| N=187 | |||||

Notes: Letters denote significant difference (p<0.05) from:

Catholics,

Pentecostals,

AICs,

Muslims,

Mission Protestants,

New Mission Protestants.

5.2.1 Network influences on preaching about HIV-relevant topics

As millions of dollars are being funneled through religious organizations in SSA, with the aim of curbing the spread of HIV in the region, it is important to cultivate a more thorough understanding of the factors that lead to the approaches religious leaders take – whether they are openly addressing AIDS or serving as a barrier to religious organizations’ involvement with the epidemic. MRP data provide the opportunity to examine the networked relationships among religious organizations in rural Malawi and explore the influence interorganizational relationships have over religious leaders in our sample areas, shaping their strategies for engaging the epidemic. Examining these pathways of message development can illuminate our understanding of both their content and impact. Identifying who talks about AIDS reveals important information about those few who do not – whose silence may represent a failure to mobilize cultural resources capable of reducing the spread of the disease. We utilize the reports of religious leaders to predict the presence of two types of messages at the congregational level – messages about HIV explicitly and sexual morality more generally.

Table 6 presents logistic regression for whether or not religious leaders preach regularly about AIDS (Model 1) and sexual morality (Model 2) in their sermons. The primary variable of interest in these models is whether religious leaders discuss AIDS with other religious leaders – this combines the first column from Table 3 for congregation and denomination leader AIDS-ties. These models demonstrate that the informal conversations religious leaders have with other religious leaders in their local communities have a strong, positive association with formally directing attention to AIDS-related topics in their congregational leadership capacities. These local relationships even appear to have more influence than formal channels or targeted training efforts (i.e., internationally sponsored AIDS workshops) over whether or not leaders address AIDS directly or sexual morality in general. Leaders who perceive AIDS as a serious problem in their community are substantially more likely than others to preach about it regularly, suggesting that religious efforts to address the problem of AIDS occurs primarily in response to the needs of the community – and not as a preemptive prevention effort.

Table 6.

Logistic regression of congregation leaders’ likelihood of preaching regularly about…

| I. Sexual Morality | II. AIDS | |

|---|---|---|

| Discusses AIDS with other Religious Leader | 3.04** (1.20) | 4.25** (1.83) |

| Religious Leader has Attended an AIDS workshop | 1.19 (0.49) | 1.09 (0.45) |

| Leader’s Evaluates Scope of AIDS Problem as Big | 1.27 (0.50) | 3.36 ** (1.40) |

| Congregation Leader has Some Secondary Education | 1.75 (0.79) | 0.98 (0.44) |

| Congregational Size - Number of Regularly Attending Adults | 1.00 (0.00) | 1.00 (0.00) |

| Tradition a | ||

| Pentecostal | 3.24 (2.16) | 0.91 (0.61) |

| AIC | 6.23 ** (4.12) | 4.34 * (3.05) |

| Muslim | 5.55 * (4.42) | 3.32 (2.78) |

| Mission Protestant | 3.69 * (2.36) | 5.99 * (4.40) |

| New Mission Protestant | 5.87 * (4.03) | 3.48 (2.45) |

| District b | ||

| South | 1.08 (0.56) | 0.68 (0.38) |

| North | 0.52 (0.25) | 0.53 (0.27) |

| Intercept | 0.37 (0.25) | 0.35 (0.25) |

| −2 Log Likelihood | −98.05 | −91.07 |

| χ2 | 21.77 *** | 39.48 ** |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.10 | 0.18 |

| N=185 | ||

Notes: p<0.01,

p<0.05,

Numbers presented are Odds Ratios and (standard errors).

Omitted category is Roman Catholic.

Omitted category is Central district.

5.3 Individual religion – Linking people to places

Data collected in Wave II of MDICP (2001) provided early glimpses into the relationship between religion and HIV risk at the individual level, and found that risk behaviors and the perception of risk vary by both religious affiliation and participation among married men (Trinitapoli and Regnerus 2006). The findings from this early and broad empirical assessment of the relationship between religion and HIV risk highlighted the salience of religiosity over denominational differences, and engendered a host of questions about the ways in which religion might shape the sexual behavior of individuals in the context of sub-Saharan Africa. In response, the MRP – along with an expanded focus on religion in Waves III-IV of the MDICP – was motivated by these findings to take a more systematic look into the role religious organizations play in individuals’ experiences related to HIV. Table 7 presents some basic descriptors of MDICP-3 respondents’ religious participation. This table shows that for MDICP-3 respondents, similar to elsewhere in SSA, religious participation is extremely high – with roughly two-thirds of the sample attending religious services at least weekly, and virtually everyone identifying with a local religious congregation. Religious participation far exceeds levels of participation in any other comparable civic activities (Yeatman and Trinitapoli 2008).

Table 7.

Descriptive overview of individual religious characteristics (MDICP-3, 2004)

| Characteristic | Proportion |

|---|---|

| Religious Tradition | |

| Catholic | 0.18 |

| Pentecostal | 0.07 |

| African Independent | 0.16 |

| Muslim | 0.24 |

| Mission Protestant | 0.22 |

| New Mission Protestant | 0.13 |

| None | 0.01 |

| Attend Religious Service within the Last… | |

| Week | 0.63 |

| Month | 0.88 |

| Participation in other Religious Activities | |

| Choir | 0.17 |

| Visiting the Sick | 0.24 |

| Revival Meeting | 0.10 |

| Membership in other non-Religious Groups | |

| Farmers’ Group | 0.31 |

| AIDS Group | 0.07 |

| Finance Group | 0.04 |

| N=3243 | |

Analyses of these later waves of MDICP data allow increasingly detailed analyses of individuals’ religious participation and its influence on a variety of demographic outcomes. As described above, the MRP provides unique opportunities to study what religious organizations are actually doing with respect to HIV and other outcomes, along with exploring the influences on those strategies. While these provide valuable insights into the link between religion and HIV previously unavailable, one of the primary strengths of the MRP design is the ability to link the organizational data from the MRP to the individual level data from MDICP-3. We assigned each MDICP respondent to his or her congregation by hand, using five key pieces of information from MDICP-3 records to make the link: congregation name, leader’s name, congregation village/location, respondent’s village, and religious tradition. In a majority of cases, the identity of the named congregation was clear. Given the low rates of literacy in our research sites, spelling irregularities and the use of multiple names by a single congregation were the most common problems faced in identifying the named congregation. A dummy variable indicating relative difficulty in assigning the respondent to the named congregation was created, and data quality analyses revealed that difficulty of assignment varied by religious involvement.8

Of the 3,243 individual respondents in MDICP-3 who identified a congregation where they participate, all but 31 were successfully matched to one of the MRP congregations. Approximately 20 MDICP respondents on average are linked to each MRP congregation (range 1–168).9 Using these congregation links, Table 8 presents the congregation level variance (with no other controls) on a variety of demographic and HIV-relevant outcomes reported by MDICP respondents. In this population, congregation level variance is a meaningful source of variation for multiple dimensions of life including sexual behavior, socio-demographic characteristics, and even religiosity (not shown). This highlights the importance of linking across these multiple levels of data to conduct multi-level analyses to explore whether these associations arise from the organizational environments religious organizations provide, or derive from other sources. Preliminary analyses using these linked MDICP-MRP data show that individuals who are frequently exposed to messages about AIDS within their congregation show: higher odds of reported abstinence among unmarried adolescents, higher rates of reported condom use among sexually active respondents, and lower odds of testing positive for HIV (Trinitapoli 2009). These data can be further examined via combined organizational and individual level analyses to explore the means by which such differences arise. A similar strategy to the one used here could be applied to link individuals to other (non-religious) local institutions (e.g., schools, cooperatives, etc.) that are thought to influence demographic phenomena.

Table 8.

Congregation level variance on individual level outcomes (MDICP-3, 2004)

| Variable | Description | Rho | Na |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic | |||

| Household Goods | Index: household owns mattress, radio, bicycle, pit latrine | 0.12 ** | 3101 |

| Education† | Ever attended secondary school (0–1) | 0.31 ** | 3101 |

| Value Crops (logged) | Logged sum; market value of crops produced last year | 0.05 ** | 3101 |

| Value Livestock (logged) | Logged sum; market value of animals owned by household | 0.14 ** | 3101 |

| HIV Prevention | |||

| A† | Never married persons; never had sex (0–1) | 0.05 ** | 615 |

| B† | Married persons; no extramarital partner in past year (0–1) | 0.04 ** | 2486 |

| C† | Sexually active persons; ever used condom (0–1) | 0.11 ** | 2887 |

| Number of Partners | Lifetime number of sexual partners, recoded to 95th percentile (0–20) | 0.08 ** | 3101 |

| Attitudes | |||

| Worried about HIV | How worried are you about catching HIV? (0–4) | 0.01 | 3101 |

| Against Premarital sex† | Reports sex between unmarried persons is never acceptable, even if the couple loves each other | 0.02 | 3101 |

| Divorce for Unfaithfulness† | Believes it is acceptable for a married woman to leave her spouse if he is unfaithful (0–1) | 0.06 ** | 3101 |

Notes: p<0.01,

Each calculation uses OLS or logistic (†) regression with no other controls.

The smaller number of observations in this table result from using listwise deletion, so that rho’s are calculated only for observations that have all data points included in the table.

6. Summary

The MRP provides an in-depth look at the structure and content of religious organizations in rural areas of three districts of Malawi – in general and with a specific emphasis on their efforts to respond to prevalent HIV/AIDS in their communities. These data provide the first opportunity to systematically investigate what religious communities are doing in response to the HIV epidemic in sub-Saharan Africa, and how they arrive at those strategies. Perhaps the greatest advantage is the capacity for these data to then be combined with the MDICP to conduct multi-level analyses that examine how these strategies actually translate into individual-level beliefs, behaviors, and trajectories of infection. The preliminary analyses here demonstrate that religious leaders in this area are actively engaging the epidemic, but do so in particularized ways that both are informed by and differentiated from internationally mandated guidelines (e.g., ABCs) (H1), are nested within networks that appear to shape how these efforts are constructed (H2), and have some influence over the way the members of their congregation are experiencing the epidemic (H3).

6.1 Limitations

It is also important to note several limitations of the collected MRP data. In pointing these out, we hope both to highlight the ways that these data should be used so as not to overextend interpretations of findings herein, and to inform strategies for handling similar issues in future studies that are interested in examining related questions.

Evaluations of MDICP data have minimized concern about the role of social desirability bias in shaping responses to survey questions about AIDS-related issues in this context (Anglewicz et al. 2009; Bignami-Van Assche 2003; Bignami-Van Assche, Reniers and Weinreb 2003). It remains unclear if the nature of the data in the MRP raises a different set of data quality issues. In the case of the targeted network data in the leader interviews, we found that religious leaders were more willing to provide “positional” identification of network contacts (e.g., relying on a description naming a specific congregation’s leader or a particular village’s chief) than to personally identify their ties (i.e., actually list names). This suggests that future work in similar settings may be more successful in gathering network data that represents the links between organizations than the links between individuals within those organizations. Interestingly, the unstructured portions of the interview rarely demonstrated this type of reluctance. When a respondent was telling a story that highlighted network relationships, they frequently provided identifying information (positional or personal, but rarely both) for the contacts they named in this way. This apparent oddity further highlights the important benefits of using qualitative methods to supplement collecting network data.

Something that initially appeared to be a problem for gathering the intended network data, actually provided an important insight into the structure of religious participation in Malawi. While attempting to differentiate between various levels of religious organization, it became clear that in both Chichewa and Chitumbuka, one word – mpingo – simultaneously refers to what, in English, we refer to separately as congregations and denominations. While the distinction between these various levels of organization is clear in western settings (Chaves 2002), it is much less well-defined in Malawi. Mpingo not only refers to multiple levels of organization simultaneously, but also represents the reality that among our respondents, these were often thought of as equal and undifferentiated sections of the same religious organization. For example, distinctions between a village’s local Catholic outpost (led by a lay woman), its local overseeing parish (governed by an ordained priest), the work of Catholic Relief Services, and activities sponsored by the Diocese, were particularly unclear to members and leaders alike.

Perhaps the most important thing to note is that while we contend that Malawi provides a particularly suitable environment for examining the questions addressed here, this study does represent three rural districts in one country. Any extensions beyond this specific context should be considered suggestive, and only to the extent that the diversity represented in Malawi corresponds to the contexts of interest.

6.2 Conclusion

This latter point highlights one of the final roles we anticipate this paper serving. The experiences we describe above from the MRP provide useful considerations for future data collection projects interested in exploring similar questions in other contexts. In the description of the MRP above, we provide early evidence for several new insights into the link between religion and HIV/AIDS in SSA that were unavailable in previous research. We hope that what we have done here inspires additional work into the specific ways that religion shapes HIV/AIDS – both using our data, to dig deeper into the questions we have begun to examine here, and in similar studies conducted elsewhere in SSA.

Figure 1.

Malawi map with MDICP & MRP research locations highlighted

Acknowledgments

Data for this research was supported by NIH Grants 1R01-HD050142 and 5R01-HD041713, Susan Watkins (PI), and was gathered in collaboration with a team of researchers also including Monica Manda, Sydney Lungu, Joel Phiri, Mark Regnerus, Chikondi Singano, Alex Weinreb and Sara Yeatman. The first author was supported by the Health and Society Scholars Program of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and a grant from the Society for the Scientific Study of Religion. The second author was supported by grants from the Religious Research Association, and an NICHD center grant (5R24-HD42849) made to the Population Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin. Any remaining errors are the sole responsibility of the first author and cannot be attributed to any of the other researchers or the funding organizations.

Footnotes

Some leaders may themselves be in the MDICP-3 sample.

For example, one primary component of the unstructured qualitative interviews asks the respondent to provide an account of their personal religious history. Within this section of the interview, respondents frequently describe their educational experiences and give accounts of various training seminars they have attended. In some of these interviews respondents mention other individuals with whom they were in school and whether they are still in contact with those individuals today. In some instances those relationships describe significant contributions to the interpersonal contexts within which the respondent constructs their doctrine or HIV-related beliefs and attitudes. Leaders made similar mentions of network relationships in sections of the interviews focused on congregational structure and the prevailing problems the congregations faced. Each such mentioned connection was additionally coded as a network linkage. These ties from the qualitative interviews are flagged in a way that identifies them as coming from a different data source, so that researchers can conduct analyses with or without these ties, as they deem appropriate. The findings presented in this paper focus only on those ties derived from the MRP’s survey components.

This process is able to more readily identify links that exist between representatives of particular religious congregations, if not explicitly between individuals.

While these categories are not the same as those used by Steensland et al (2000), they reflect a translation of the coding strategy they used, into the Malawian context. The strategy takes into account the historical period in which the various religious traditions were first established in the region (adams and Trinitapoli 2008).

The 60% figure is not found directly in Table 4. Rather it combines all nominated HIV/AIDS discussion partners and compares those with congregation and denomination leaders to other sources. As such, the 60% figure may be an undercount if other sources (e.g., NGOs) are actually also representatives of religious organizations.

In other words, respondents who reported attending infrequently were less likely to have provided clear information allowing us to identify the congregation they sometimes attend, while those who attend frequently tended to provide very clear information.

These numbers are smaller than the mean and range values reported in Table 1 because the MDICP sample only represents a sample of the area populations where these congregations are located. Thus MRP congregations draw participants from the area, who are not MDICP respondents.

Contributor Information

jimi adams, Email: jimi.adams@asu.edu.

Jenny Trinitapoli, Email: jennytrini@pop.psu.edu.

References

- adams j. Sociology. Ohio State University; Columbus, OH: 2007. Religion networks and HIV in rural Malawi. [Google Scholar]

- adams j, Trinitapoli J. Reconceptualizing sociological analyses of religion in sub-Saharan Africa. Annual Meetings of the Society for the Scientific Study of Religion; Louisville, KY. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Agadjanian V. Religion, social milieu and the contraceptive revolution. Population Studies. 2001;55(2):135–148. doi: 10.1080/00324720127691. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Agadjanian V. Gender, religious involvement and HIV/AIDS prevention in Mozambique. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;61(7):1529–1539. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahiante A. HIV/AIDS: Clergymen’s response to stigmatization. Africa News Service 2003 [Google Scholar]

- Anglewicz P, adams j, Obare F, Watkins SC, Kohler H-P. The Malawi Diffusion and Ideational Change Project 2004–2006: Data collection, data quality and analysis of attrition. Demographic Research. 2009;20(21):503–540. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2009.20.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett DB, Kurian GT, Johnson TM. World Christian Encyclopedia: A comparative survey of churches and religions in the Modern World. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Behrman JR, Kohler H-P, Watkins SC. Social networks HIV/AIDS and risk perceptions. Demography. 2007;44(1):1–33. doi: 10.1353/dem.2007.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bignami-Van Assche S. Are we measuring what we want to measure? An analysis of individual consistency in survey response in rural Malawi. Demographic Research. 2003;S1(3):77–108. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2003.S1.3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bignami-Van Assche S, Chao LW, Anglewicz P, Chilongozi D, Bula A. The validity of self-reported likelihood of HIV infection among the general population in rural Malawi. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2007;83:35–40. doi: 10.1136/sti.2006.020545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bignami-Van Assche S, Reniers G, Weinreb AA. An assessment of the KDICP and MDICP Data Quality: Interviewer Effects, Question Reliabilty and Sample Attrition. Demographic Research. 2003;S1(2):31–76. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2003.S1.2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chaves M. National congregations study. Tuscon, Arizona: University of Arizona: Department of Sociology; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Chaves M. Religious organizations - data resources and research opportunities. American Behavioral Scientist. 2002;45(10):1523–1549. doi: 10.1177/0002764202045010005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chaves M, Konieczny ME, Beyerlein K, Barman E. The national congregations study: Background, methods, and selected results. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1999;38(4):458–476. doi: 10.2307/1387606. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chimwaza A, Watkins SC. Giving care to people with symptoms of AIDS in rural sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS Care. 2004;16(7):795–807. doi: 10.1080/09540120412331290211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison CG, George LK. Religious involvement, social ties, and social support in a southeastern community. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1994;33(1):46–61. doi: 10.2307/1386636. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Englund H. Christian independency and global membership: Pentecostal extraversions in Malawi. Journal of Religion in Africa. 2003;33(1):83–111. doi: 10.1163/157006603765626721. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feierman S. Struggles for control: The social roots of health and healing in Modern Africa. African Studies Review. 1985;28(23):73–147. doi: 10.2307/524604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiedler K. Islamization in Malawi: Perceptions and reality. 2004a [unpublished manuscript]. [Google Scholar]

- Fiedler K. The process of religious diversification in Malawi: A reflection on method and a first attempt at synthesis. 2004b [unpublished manuscript]. [Google Scholar]

- Garner RC. Safe sects? Dynamic religion and AIDS in South Africa. Journal of Modern African Studies. 2000;38(1):41–69. doi: 10.1017/S0022278X99003249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glynn JR, Carael M, Auvert B, Kahindo M, Chege J, Musonda R, Kaona F, Buve A and the Study Group on the Heterogeneity of HIV Epidemics in African Cities. Why do young women have a much higher prevalence of HIV than young men? A study in Kisumu, Kenya and Ndola, Zambia. Aids. 2001;15:51–60. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200108004-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green EC. USAID/Washington and The Synergy Project. TvT Associates; Washington DC: 2003. Faith-based organizations: Contributions to HIV prevention. [Google Scholar]

- Hearn J. The ‘Invisible’ NGO: US Evangelical Missions in Kenya. Journal of Religion in Africa. 2002;32(1):32–60. doi: 10.1163/15700660260048465. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Helleringer S, Kohler H-P. Social networks, perceptions of risk, and changing attitudes towards HIV/AIDS: New evidence from a longitudinal study using fixed-effects analysis. Population Studies. 2005;59(3):265–282. doi: 10.1080/00324720500212230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins P. The Next Christendom: The Rise of Global Christianity. New York: Oxford University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kaler A. AIDS-Talk in everyday life: The presence of HIV/AIDS in men’s informal conversation in southern Malawi. Social Science & Medicine. 2004;59(2):285–297. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuphunda S. Religious institutions empowered in sensitising people about HIV/AIDS. Africa News Service 2003 [Google Scholar]

- Lagarde E, Enel C, Seck K, Gueye A, Piau JP, Pison G, Delaunay V, Ndoye I, Mboup S. Religion and protective behaviours towards AIDS in rural Senegal. AIDS. 2000;14:2027–2033. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200009080-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell D. Delivered from the spirit of poverty? Pentecostalism, prosperity and modernity in Zimbabwe. Journal of Religion in Africa. 1998;28(3):350–373. [Google Scholar]

- McPherson JM. Hypernetwork sampling: Duality and differentiation among voluntary organizations. Social Networks. 1982;3(4):225–249. doi: 10.1016/0378-8733(82)90001-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer JW, Rowan B. Institutionalized organizations: Formal structure as myth and ceremony. The American Journal of Sociology. 1977;83(2):340–363. doi: 10.1086/226550. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mkandawire O. The Living Waters Church: A historical, cultural and theological approach: A study of church growth. 2000 [unpublished manuscript] [Google Scholar]

- National Aids Commission. Estimating national HIV prevalence in Malawi from sentinel surveillance data: Technical report. Lilongwe, Malawi: POLICY Project; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- National Statistical Office. Malawi Demographic and Health Survey 2004. Calverton, MD: ORC Macro; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Obare F. The effect of non-response on population-based HIV prevalence estimates: The case of rural Malawi. (SNP Working Papers No. 7) Population Studies Center, University of Pennsylvania; Philadelphia, PA: 2005. http://www.pop.upenn.edu/networks. [Google Scholar]

- Obare F, Fleming P, Anglewicz P, Thornton R, Martinson F, Kapatuka A, Poulin M, Watkins S, Kohler H-P. Acceptance of repeat population-based voluntary counseling and testing for HIV in rural Malawi. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2008;85:139–144. doi: 10.1136/sti.2008.030320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oosthuizen GC. The Healer-Prophet in Afro-Christian Churches. Leiden, New York and Köln: E.J. Brill; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Pisani E. Joint united national program for HIV/AIDS. Geneva: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Schmid GP, Buvé A, Mugyenyi P, Garnett GP, Hayes RJ, Williams BG, Calleja JG, De Cock KM, Whitworth JA, Kapiga SH, Ghys PD, Hankins C, Zaba B, Heimer R, Boerma JT. Transmission of HIV-1 infection in sub-Saharan Africa and effect of elimination of unsafe injections. Lancet. 2004;363(9407):482–488. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15497-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spaeth JL, O’Rourke DP. Design of the national organizations study. In: Kalleberg AL, Knoke D, Marsden PV, Spaeth JL, editors. Organizations in America: Analyzing their structures and human resource practices. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1996. pp. 23–44. [Google Scholar]

- Stark R. Religion as context: Hellfire and delinquency one more time. Sociology of Religion. 1996;57(2):163–173. doi: 10.2307/3711948. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stark R, Finke R. Catholic religious vocations: Decline and revival. Review of Religious Research. 2000;42(2):125–145. doi: 10.2307/3512525. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steensland B, Park JZ, Regnerus MD, Robinson LD, Wilcox WB, Woodberry RD. The measure of American religion: Toward improving the state of the art. Social Forces. 2000;79(1):291–318. doi: 10.2307/2675572. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Takyi BK. Religion and women’s health in Ghana: Insights into HIV/AIDS preventive and protective behavior. Social Science and Medicine. 2003;56(6):1221–1234. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00122-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trinitapoli J. Religious responses to aids in sub-Saharan Africa: An examination of religious congregations in rural Malawi. Review of Religious Research. 2006;47(3):253–270. [Google Scholar]

- Trinitapoli J. Religious teachings and influences on the ABCs of HIV prevention in Malawi. Social Science and Medicine. 2009;69(2):199–209. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trinitapoli J, Regnerus MD. Religion and HIV risk behaviors among married men: Initial results from a study in rural sub-Saharan Africa. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2006;45(4):505–528. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-5906.2006.00325.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS. 2006 Report on the global AIDS epidemic: A UNAIDS 10th anniversary special edition. Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS and World Health Organization; Geneva. 2006a. [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS. AIDS epidemic update: Special report on HIV/AIDS. Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) and World Health Organization; Geneva. 2006b. [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS. AIDS epidemic update. Joint Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) and World Health Organization; Geneva. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins SC. Navigating the AIDS epidemic in rural Malawi. Population and Development Review. 2004;30(4):673–705. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2004.00037.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins SC, Warriner I. How do we know we need to control for selectivity? Demographic Research. 2003;S1(4):109–142. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2003.S1.4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins SC, Behrman JR, Kohler H-P, Zulu EM. Introduction to “Research on Demographic Aspects of HIV/AIDS in Rural Africa”. Demographic Research. 2003;S1(1):1–30. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2003.S1.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Confronting AIDS: Public priorities in a global epidemic. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Yeatman SE, Trinitapoli J. Beyond denomination: The relationship between religion and family planning in rural Malawi. Demographic Research. 2008;19(55):1851–1882. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2008.19.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]