Abstract

The devastating Sigatoka disease complex of banana is primarily caused by three closely related heterothallic fungi belonging to the genus Mycosphaerella: M. fijiensis, M. musicola, and M. eumusae. Previous phylogenetic work showing common ancestry led us to analyze the mating-type loci of these Mycosphaerella species occurring on banana. We reasoned that this might provide better insight into the evolutionary history of these species. PCR and chromosome-walking approaches were used to clone the mating-type loci of M. musicola and M. eumusae. Sequences were compared to the published mating-type loci of M. fijiensis and other Mycosphaerella spp., and a novel organization of the MAT loci was found. The mating-type loci of the examined Mycosphaerella species are expanded, containing two additional Mycosphaerella-specific genes in a unique genomic organization. The proteins encoded by these novel genes show a higher interspecies than intraspecies homology. Moreover, M. fijiensis, M. musicola, and M. eumusae contain two additional mating-type-like loci, containing parts of both MAT1-1-1 and MAT1-2-1. The data indicate that M. fijiensis, M. musicola, and M. eumusae share an ancestor in which a fusion event occurred between MAT1-1-1 and MAT1-2-1 sequences and in which additional genes became incorporated into the idiomorph. The new genes incorporated have since then evolved independently in the MAT1-1 and MAT1-2 loci. Thus, these data are an example of the evolutionary dynamics of fungal MAT loci in general and show the great flexibility of the MAT loci of Mycosphaerella species in particular.

In fungi belonging to the Pezizomycotina, sexual development is controlled by a single mating-type locus (MAT). In all heterothallic filamentous ascomycetes studied to date, the mating-type locus contains one of two forms of dissimilar sequences (known as the idiomorph) occupying the same chromosomal position in the genome (23). By convention, mating-type idiomorphs of complementary isolates are termed MAT1-1 and MAT1-2 (32). In contrast, homothallic fungi contain both mating-type genes (either linked or unlinked) in a single genome and even some homothallic Neurospora species exist that contain only a MAT1-1 homologue (20). Until now, the idiomorphs of all heterothallic members of the Dothideomycetes have been characterized by the presence of a single gene. MAT1-1 isolates contain a single gene encoding a protein with an alpha domain (MAT1-1-1), and MAT1-2 isolates a single gene encoding a protein containing a high-mobility group (HMG) domain (MAT1-2-1) (32). Homothallic members of the Dothideomycetes can carry both mating-type genes in their haploid genome, linked or unlinked (37). MAT1-1-1 and MAT1-2-1 encode transcription factors controlling the signal transduction pathway involved in mating identity and development of the sexual cycle (7, 24, 35).

After wheat, rice, and corn, bananas (Musa spp.) are the fourth-most-important staple food crop. Banana production can be severely impaired by a variety of diseases. Currently, the most serious and economically important leaf spot diseases of bananas are caused by different species of the fungal genus Mycosphaerella. The Sigatoka leaf spot disease complex of bananas involves three closely related fungi, Mycosphaerella fijiensis (anamorph Pseudocercospora fijiensis), causing the black Sigatoka disease; M. musicola (anamorph Pseudocercospora musae), responsible for yellow Sigatoka disease; and M. eumusae (anamorph Pseudocercospora eumusae), causing eumusae leaf spot disease (2, 10, 18). Of these, M. fijiensis is currently regarded as the most important pathogen, causing premature ripening of the fruits and yield losses of up to 50% (21).

The chronology of the disease record around the world suggests that, as for their host genus Musa, Southeast Asia is the center of origin for all three pathogens. Yellow Sigatoka was first described on banana in Java in 1902 and was found worldwide throughout the whole banana production area during the 1940s. After its discovery on the Fiji islands in the early 1960s, M. fijiensis spread rapidly across all continents, thereby replacing M. musicola as the main disease agent. The third species, M. eumusae, was recognized as a new constituent of the Sigatoka disease complex in the mid-1990s and is currently still restricted to Southeast Asia and parts of Africa (5, 10, 18, 26). A recent study of the phylogeny of Mycosphaerella species occurring on banana indicated that 20 species of Mycosphaerella or its anamorphs can occur on banana. Several of these species are able to coinfect a single leaf or even lesion. This study also showed that the three major pathogens represent a monophyletic clade and share common ancestry (3). We reasoned that analyzing the structure and organization of the mating-type loci of the primary Mycosphaerella species occurring on banana might provide better insight into the evolutionary history of these species and possibly even into the history of the disease. Therefore, we identified and cloned the mating-type loci of these species and compared them to mating-type loci of other Mycosphaerella spp.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolates.

A list of the Mycosphaerella strains isolated from banana and used in this study is provided in Table 1. Isolates were maintained in a 10% glycerol solution at −80°C, and all are deposited at the Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures (CBS), Utrecht, The Netherlands.

TABLE 1.

List of species and isolates used in this study

| Species | Accession no. for isolatea | Mating type | Origin |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mycosphaerella eumusae | CIRAD670/CBS111438 | MAT1-1 | Vietnam |

| CIRAD485/CBS121381 | MAT1-2 | Thailand | |

| Mycosphaerella fijiensis | CIRAD86/CBS120258 | MAT1-1 | Cameroon |

| CIRAD251/CBS121358 | MAT1-2 | Costa Rica | |

| Mycosphaerella musicola | UQ2003/CBS121374 | MAT1-1 | Australia |

| CIRAD90/CBS121368 | MAT1-2 | Colombia |

Accession numbers are from the Centre de Coopération Internationale en Recherche Agronomique pour le Dévelopment (CIRAD), Montpellier, France, or the University of Queensland (UQ), Australia, and Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures (CBS), Utrecht, The Netherlands.

Isolation and characterization of mating-type loci of Mycosphaerella spp.

Previously published degenerate primers were used to amplify a conserved region within MAT1-1-1 and MAT1-2-1 from different Mycosphaerella species occurring on banana. PCR amplification and sequencing conditions were as previously described (17). Sequence fragments were assembled using SeqMan (Lasergene package; DNAstar, Madison, WI). Nested primer sets were designed based upon contigs corresponding to MAT1-1-1 and MAT 1-2-1 sequences. These primer sets were used in combination with primers provided with a DNA-walking SpeedUp kit (Seegene, Inc., Rockville, MD) to amplify fragments adjacent to the initially cloned fragments. Amplified fragments were purified using GFX PCR DNA and a gel band purification kit (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) and cloned in a pGEM-T vector system I (Promega, Madison, WI). The identities of the cloned fragments were confirmed by sequencing, and subsequent genome-walking steps were performed to obtain the complete idiomorph.

DNA and amino acid sequence comparisons and bioinformatics.

Sequence data obtained from genome walking were assembled and edited using the SeqMan and EditSeq programs from the Lasergene 7.2.1 package (DNAstar, Madison, WI). Consensus sequence files were exported to the Vector NTI 10.1 software package (Invitrogen, United States) for further analysis and the creation of graphical maps. Sequence data were analyzed using the basic local alignment search tools (BLAST) at NCBI (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) (1). Open reading frames (ORFs) and intron positions were predicted by comparing the sequence data with known MAT sequences from other filamentous fungi, as well as by means of the FGENESH gene prediction module from the MOLQUEST software package (Softberry, Inc., Mount Kisco, NY) (28) with the Stagonospora nodorum data set as reference. Genomic comparisons to the recently released genomic sequences of the M. graminicola isolate IPO323 and the M. fijiensis isolate CIRAD86 were performed at the respective genome portal sites at the JGI-DOE (http://genome.jgi-psf.org/Mycgr3/Mycgr3.home.html and http://genome.jgi-psf.org/Mycfi1/Mycfi1.home.html). Phylogenetic analyses were performed using the Phylogeny.fr platform (www.phylogeny.fr) and comprised the following steps. Sequences were aligned with T-Coffee (version 6.85), and gaps and poorly aligned regions were removed with Gblocks (version 0.91b), with a minimum length of block after gap cleaning of 10, no gap positions allowed in the final alignment, and a maximum of 8 contiguous nonconserved positions. The phylogenetic tree was reconstructed based upon the maximum likelihood method implemented in the PhyML program using the WAG amino acid substitution model and the NNI tree building algorithm, and the reliability of the branches was assessed by 500 bootstrap replicates (12).

DNA and RNA manipulations.

Basic DNA and RNA manipulations were performed based on standard procedures (29). Escherichia coli strain JM109 (Promega) was used for propagation of constructs. Genomic DNA from axenic cultures grown on agar plates was extracted using a commercial DNA isolation kit (MoBio Laboratories, Carlsbad, CA) according to the vendor's instructions. Total RNA from M. fijiensis isolates (Table 1) grown for 7 days at 25°C in liquid potato dextrose broth was isolated using Trizol reagent (Life Technologies). Reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) was performed on cDNA made using a Superscript III first-strand synthesis system for RT-PCR (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Primers used for RT-PCR were designed to distinguish between genomic DNA and cDNA (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Primers used for RT-PCR and expected sizes of amplicons from the Mycosphaerella fijiensis target genes

| Primer | Sequence | Target gene | Expected size of amplicon from: |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genomic DNA | cDNA | |||

| Mat1F | CATGAGCACGCTGCAGCAAG | MAT1-1-1 | 702 | 547 |

| Mat1R | GTAGCAGTGGTTGACCAGGTCAT | |||

| Mat2F | GGCGCTCCGGCAAATCTTC | MAT1-2-1 | 720 | 616 |

| Mat2R | CTTCTCGGATGGCTTGCGTG | |||

| ORF1F | CTATCCAGCAAGGCCCAG | MATORF1 | 441 | 382 |

| ORF1R | TTCTGCTGCATCTCCTCCA | |||

| ORF2F | CTCACGCATGACACCTCCGA | MATORF2 | 733 | 683 |

| ORF2R | GCGRTTCTGCGTAGTCACATC | |||

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

GenBank accession numbers for the sequences reported are as follows: M. eumusae MAT1-1, GU046393; M. eumusae MAT1-2, GU046394; M. musicola MAT1-1, GU057991; and M. musicola MAT1-2, GU057992.

RESULTS

Cloning and characterization of mating-type loci.

PCR amplification of genomic DNA from M. musicola and M. eumusae MAT1-1 and MAT1-2 isolates using degenerate primers yielded fragments with homology at the nucleotide level to the mating-type genes of other Dothideomycetes. Several subsequent chromosome-walking steps were performed in both the downstream and upstream direction to obtain the full sequence of the mating-type genes, as well as the whole idiomorph.

The predicted gene structures of the cloned MAT1-1-1 and MAT1-2-1 genes of M. eumusae and M. musicola were compared to the published gene structures of the M. fijiensis MAT1-1-1 and MAT1-2-1 genes (GenBank accession numbers DQ787015 and DQ787016, respectively) (6). The predicted MAT1-1-1 genes of the three pathogens were remarkably similar; all encode a protein of 388 amino acids, and in all three species, the ORF was interrupted by three introns of almost identical size (51, 55, and 49 nucleotides in the M. fijiensis and M. musicola MAT-1-1 and 51, 50, and 49 nucleotides in the M. eumusae MAT1-1-1). The first two introns were located in the α-domain comprising areas of MAT1-1-1 at exactly the same positions as described for other MAT1-1-1 genes. The predicted third intron was located downstream from the α-domain. This third intron was absent from the MAT1-1-1 gene from Mycosphaerella graminicola and Septoria passerinii, but its presence and location were identical for the third intron recently described within the MAT1-1-1 gene of several Cercospora species and Passalora fulva (17, 30). BLASTP searches of the predicted MAT1-1-1 of M. eumusae and M. musicola showed that both proteins exhibited the highest similarity to MAT1-1-1 of M. fijiensis, with 94% and 95% identity, respectively. The second-best hits were obtained with MAT1-1-1 of Mycosphaerella pini and P. fulva (69% identity). The predicted MAT1-1-1 sequences of M. eumusae and M. musicola were 94% identical.

The published size of M. fijiensis MAT1-2-1, as well as the published sizes of the introns (33 and 50 nucleotides), deviated from the predicted gene models in M. eumusae and M. musicola. This led us to reevaluate the published model of the M. fijiensis MAT1-2-1 using the same prediction tools used for M. eumusae and M. musicola, resulting in a model corresponding to the other two banana pathogens. The predicted proteins varied in size, being 411 (M. musicola), 423 (M. eumusae), and 433 amino acids (M. fijiensis) in length, but the sizes and positions of the two predicted introns were identical (54 and 50 nucleotides). The positions of the predicted introns corresponded to the positions of these introns in MAT1-2-1 of other Mycosphaerella species. BLASTP searches showed that the MAT1-2-1 proteins of M. eumusae and M. musicola have the highest similarity to the M. fijiensis MAT1-2-1 (89% and 87% identity, respectively). The second-best hits were obtained with the MAT1-2-1 proteins of several Cercospora species (∼60% identity). The predicted amino acid sequences of MAT1-2-1 of M. eumusae and M. musicola were 90% identical.

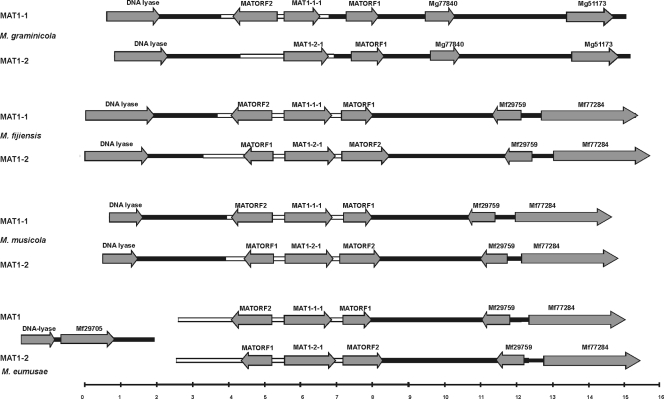

Approximately 12 kb of M. musicola genomic DNA from MAT1-1 and MAT1-2 isolates was obtained by genome walking and subsequently sequenced. BLAST2 analyses (using the BLASTN algorithm with standard settings) of these sequences indicated that in the MAT1-1 and MAT1-2 isolates, 3.9 kb of MAT1-1 and 4.3 kb of MAT1-2 were dissimilar and therefore by definition belonged to the idiomorph. BLASTP and BLASTX analyses of the genomic region upstream of the idiomorph revealed the presence of a DNA lyase gene with highest homology to the M. fijiensis DNA lyase, both at the nucleotide (76% identity over 1,083 nucleotides) and the protein level (67% identity over 312 amino acids). The DNA lyase gene is commonly found upstream from the mating-type loci in other ascomycetes (8, 33, 36). Besides the DNA lyase gene, no other genes could be identified upstream from the mating-type loci (Fig. 1). Analyses of the genomic region downstream from the idiomorph revealed the presence of two putative genes. BLAST comparisons of these gene models with the publicly available genomic sequences of M. fijiensis and M. graminicola indicated that this downstream region in M. musicola was highly syntenous to the corresponding genomic region in M. fijiensis and not to that in M. graminicola (Fig. 1). The two predicted genes were highly homologous to M. fijiensis gene models encoding Mycfi1-29759 (88% identity at the nucleotide and 88% identity at the amino acid level) and Mycf1-77284 (85% identity at the nucleotide and 88% identity at the amino acid level).

FIG. 1.

Organization of mating-type loci of Mycosphaerella graminicola, M. fijiensis, M. musicola, and M. eumusae. Dissimilar sequences (idiomorphs) are indicated by white boxes, and identical sequences by black boxes. Predicted gene models are indicated by arrows. The scale at the bottom shows size in kilobases.

The organization of MAT1-1 and MAT1-2 in isolates of M. eumusae was different (Fig. 1). Approximately 12 kb of genomic DNA containing the mating-type loci from MAT1-1 and MAT1-2 isolates of M. eumusae was sequenced. BLAST2 analyses indicated that in the MAT1-1 and MAT1-2 isolates, at least 5.1 kb of MAT1-1 and 6.1 kb of MAT1-2 sequences were dissimilar and thus belonged to the idiomorph. However, the mating-type loci of M. eumusae are likely to be even larger, as attempts to clone the upstream boundaries of the M. eumusae idiomorph (putatively containing the DNA lyase) by extended genome walking were not successful. A part of the M. eumusae DNA lyase gene was amplified using degenerate primers, and this fragment was extended by genome walking to a 3.7-kb fragment that was identical in the MAT1-1 and MAT1-2 isolates and, thus, did not belong to the idiomorph. Additionally, an attempt to bridge the M. eumusae idiomorph to the flanking regions by long-range PCR between the idiomorph sequence and the DNA lyase gene was not successful. BLASTX comparisons of the M. eumusae region neighboring the DNA lyase against the M. fijiensis genome revealed the presence of a gene highly homologous to a predicted M. fijiensis gene model (Mycf1-29705 protein) encoding an acyl-coenzyme A transferase/carnitine dehydratase (79% identity on the amino acid and 81% identity on the nucleotide level). Interestingly, in M. fijiensis, this gene was located on the same scaffold as the mating-type locus but separated by ∼39 kb from the MAT1-1-1 gene.

Similar to the situation in M. musicola, the genomic region downstream from the idiomorph of M. eumusae was highly syntenous with the corresponding genomic region in M. fijiensis. This region contained two predicted genes highly homologous to M. fijiensis gene models for Mycf1-29759 (88% identity on the nucleotide and 90% identity on the amino acid level) and Mycf1-77284 (84% identity on the nucleotide and 82% identity on the amino acid level).

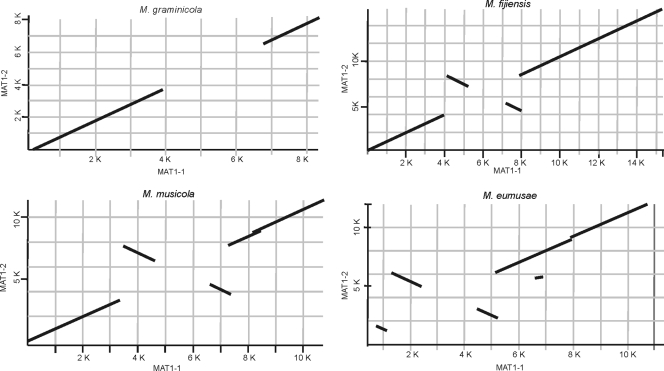

A BLAST2 pairwise alignment of the MAT1-1 and MAT1-2 idiomorphs, extended with sequences flanking the idiomorphs, revealed the presence of two inverted regions within the idiomorphs. These inversions were present in M. fijiensis (as described before [6]), M. musicola, and M. eumusae but were clearly absent from the M. graminicola idiomorph (Fig. 2). The inverted regions present within the M. musicola idiomorphs were homologous to the inverted regions present within the M. fijiensis idiomorphs. The same pairwise alignment of the MAT1-1 and MAT1-2 idiomorphs of M. eumusae revealed a more complicated pattern that included three inverted regions. Two of these inversions shared high similarity with the inversions observed in M. musicola and M. fijiensis, whereas the other (an ∼1.3-kb inversion) was restricted to M. eumusae (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Pairwise comparison of mating-type loci of Mycosphaerella graminicola, M. fijiensis, M. musicola, and M. eumusae. MAT1-1 and MAT1-2 and flanking regions of M. graminicola, M. fijiensis, M. musicola, and M. eumusae were analyzed by BLAST2. Plots show the presence of inverted regions with high levels of identity within the idiomorphs of the banana pathogens. The MAT1-1 sequences are plotted on the x axis, and the MAT1-2 sequences are plotted on the y axis. Numbers indicate the size of the analyzed fragments in kilobases.

The mating-type loci of members of the Sigatoka disease complex contain additional genes.

The inverted regions observed within the M. fijiensis idiomorph were analyzed in more detail by using BLASTX analysis and the FGENESH gene prediction module. These analyses predicted the presence of two putative genes, designated MATORF1 and MATORF2, respectively. The M. fijiensis MATORF1 is located downstream on the same strand as MAT1-1-1, whereas MATORF2 is found upstream from the MAT1-1-1 gene on the opposite DNA strand in a head-to-head orientation. The MATORF1 and MATORF2 homologs present within the M. fijiensis MAT1-2 idiomorph are present in an inverted order; MATORF1 is located upstream from MAT1-2-1 and MATORF2 downstream from MAT1-2-1 (Fig. 1), thus giving rise to the inverted regions observed in the pairwise alignments.

Analysis of the mating-type loci of M. musicola and M. eumusae and the published idiomorph of M. graminicola indicated the presence of orthologs of these new genes in all of these species, although not in all mating types (Fig. 1 and Table 3). Furthermore, within the available idiomorph sequences of the related S. passerinii (GenBank accession numbers AF483193 and AF483194), partial MATORF1 and MATORF2 genes could be distinguished (16). The idiomorphs of M. graminicola and S. passerinii are very similar, with MATORF2 lacking in both MAT1-2 idiomorphs and MATORF1 located outside the idiomorphs (Fig. 1).

TABLE 3.

Comparison of the organization of the newly identified MATORF1 and MATORF2 genes in both idiomorphs of Mycosphaerella graminicola, M. fijiensis, M. eumusae, and M. musicola

| Species |

MATORF1a |

MATORF2a |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene size (nt) | Intron size(s) (nt) | Protein size (aa) | Gene size (nt) | Intron size(s) (nt) | Protein size (aa) | |

| M. eumusae MAT1-1 | 791 | 59 | 243 | 1,135 | 49 | 361 |

| M. eumusae MAT1-2 | 818 | 59 | 252 | 1,145 | 50 | 364 |

| M. fijiensis MAT1-1 | 791 | 59 | 243 | 1,136 | 50 | 361 |

| M. fijiensis MAT1-2 | 818 | 59 | 252 | 1,315 | 50, 77 | 395 |

| M. graminicola MAT1-1 | 901 | 53, 53 | 264 | 1,226 | 56, 49, 57 | 354 |

| M. graminicola MAT1-2 | 910 | 53, 53 | 267 | |||

| M. musicola MAT1-1 | 791 | 59 | 243 | 1,135 | 49 | 361 |

| M. musicola MAT1-2 | 818 | 59 | 252 | 1,145 | 50 | 364 |

nt, nucleotides; aa, amino acids.

A directed BLASTX search identified only a single sequence with homology to each ORF. The single hit with MATORF2 (e-value, 5e-21), as well as the single hit with MATORF1 (e-value, 6e-7), corresponded to recently published unknown genes (GenBank accession numbers DQ659350 and DQ659351, respectively) found within the idiomorph of Passalora fulva, a species that also belongs to the Mycosphaerellaceae (30).

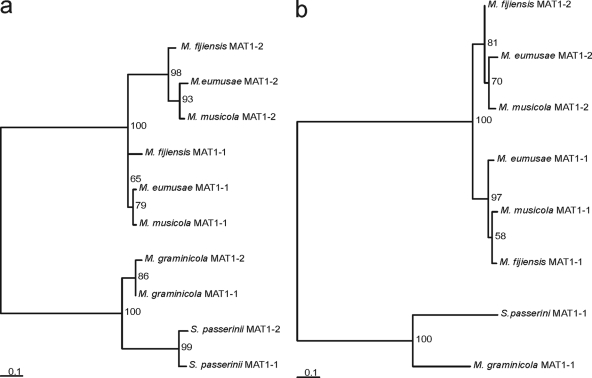

A phylogenetic comparison of the deduced proteins encoded by the MATORF1 and MATORF2 genes revealed that the interspecies homology between the three banana pathogens was greater than the intraspecies homology. Thus, MATORF1 from an M. fijiensis MAT1-1 isolate exhibited higher homology to MATORF1 from an M. eumusae or M. musicola MAT1-1 isolate (88% and 84% amino acid identities, respectively) than to MATORF1 from an M. fijiensis MAT1-2 isolate (64% identity). The same phenomenon was observed for MATORF2. This contrasted with the situation in M. graminicola and S. passerinii, where the intraspecies homology was clearly the highest (Fig. 3; also see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

FIG. 3.

Phylogram of the predicted amino acid sequences of MATORF1 and MATORF2. The phylograms are based upon the maximum likelihood method implemented in the PhyML program. Analyses were performed for MATORF1 (a) and MATORF2 (b) from both idiomorphs of Mycosphaerella eumusae, M. fijiensis, M. musicola, M. graminicola, and Septoria passerinii. Bootstrap support values from 500 replicates are shown as percentages at the nodes. Scale bars indicate the number of substitutions per site.

MATORF1 and MATORF2 are expressed in a mating-type-dependent fashion.

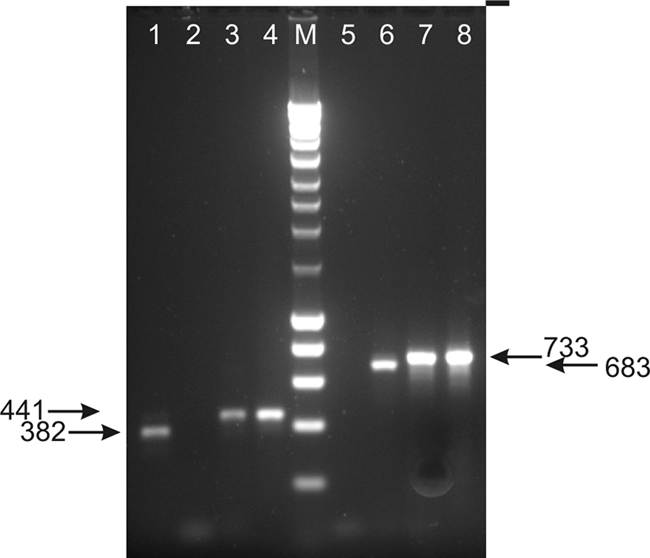

RT-PCR experiments were performed on M. fijiensis isolates of opposite mating type to determine whether MATORF1 and MATORF2 are expressed and thus encode functional genes. Attempts to cross the complementary isolates CIRAD251 and CIRAD86 were unsuccessful. Therefore, the expression could only be analyzed under conditions nonconducive for mating. No fragments indicative of expression of MAT1-1-1 or MAT1-2-1 were observed. However, RT-PCR performed on RNA isolated from the MAT1-2 isolate CIRAD251 yielded a fragment corresponding to the expected size of an expressed MATORF1 protein. Similarly, a fragment with the expected size of an expressed MATORF2 protein was detected in RNA isolated from the MAT1-1 isolate CIRAD86 (Fig. 4). These fragments were cloned, and sequence analysis confirmed their proper identities, as well as the predicted intron boundaries. This RT-PCR experiment was performed on two independently generated RNA samples. In both experiments, the expression of MATORF1 was restricted to the MAT1-2 isolate, and the expression of MATORF2 was limited to the MAT1-1 isolate.

FIG. 4.

RT-PCR analysis of MATORF1 and MATORF2 expression in Mycosphaerella fijiensis. The isolates used were the MAT1-1 isolate CIRAD86 and the M. fijiensis MAT1-2 isolate CIRAD251. PCR with primer combinations ORF1F/ORF1R (lanes 1 to 4) and ORF2F/ORF2R (lanes 5 to 8) was performed on cDNA derived from CIRAD251 (lanes 1 and 5), cDNA derived from CIRAD86 (lanes 2 and 6), genomic DNA from CIRAD251 (lanes 3 and 7), and genomic DNA from CIRAD86 (lanes 4 and 8). The lane labeled M contains a DNA marker. The numbers to left and right show nucleotide sizes of amplified fragments.

Members of the Sigatoka disease complex contain additional loci of fused mating-type-like genes.

The RT-PCR experiments did not reveal any expression of the M. fijiensis mating-type genes MAT1-1-1 and MAT1-2-1, but these experiments did yield a surprising result. Negative control reactions performed on genomic DNA of CIRAD86 (MAT1-1) using MAT1-2-1-specific primers sometimes yielded a fragment. Similarly, PCR using MAT1-1-1-specific primers irregularly produced an amplicon in MAT1-2 isolates. This was investigated in more detail.

Primers Mat2F and Mat2R were used to amplify part of MAT1-2-1 from a MAT1-2 isolate. This sequence was compared to the genome sequence of the M. fijiensis MAT1-1 isolate CIRAD86 by BLAST analysis. Surprisingly, this MAT1-2-1-specific sequence gave a significant hit with sequences on scaffold 15 of the genome sequence of this MAT1-1 isolate (>90% identity in 336 bp). Additionally, Mat1F and Mat1R were used to amplify part of MAT1-1-1 from a MAT1-1 isolate and the sequence was compared to the M. fijiensis genome sequence. As expected, this BLAST analysis gave a hit with the M. fijiensis MAT1-1-1 locus on scaffold 2, but it also gave a significant hit with sequences on scaffold 10 (>90% identity in 452 bp).

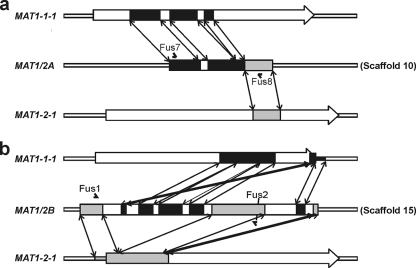

The M. fijiensis genome sequences surrounding these areas of scaffold 10 and scaffold 15 were analyzed in more detail. This revealed the presence of two genomic regions sharing extensive homology (>90% identity on nucleotide level) with parts of both the MAT1-1-1 and MAT1-2-1 genes of M. fijiensis. These two fusion loci, composed of both MAT1-1-1 and MAT1-2-1 sequences, were designated MAT1/2A and MAT1/2B. Both MAT1/2A and MAT1/2B were unique in their composition and showed a distinct pattern of MAT1-1-1 and MAT1-2-1 sequences. There was no sequence similarity between the two fused mating-type loci (Fig. 5). Neither was there any sequence similarity between the sequences flanking the two fusion loci. No clear gene models could be annotated for either fusion region. A partial α-domain was only distinguishable in MAT1/2A, whereas no HMG domain region was detectable in either MAT1/2A or MAT1/2B.

FIG. 5.

Schematic overview of the organization and composition of the Mycosphaerella fijiensis MAT1/2A and MAT1/2B fusion loci. Indicated are the areas sharing >90% nucleotide identity between the Mycosphaerella fijiensis MAT1/2A (a) and MAT1/2B (b) fusion loci and the M. fijiensis mating-type genes MAT1-1-1 and MAT1-2-1. MAT1-1-1 sequences and their corresponding positions in MAT1/2A and MAT1/2B are marked in black. MAT1-2-1 sequences and corresponding locations in MAT1/2A and MAT1/2B are marked in gray. Double-ended arrows mark the positions of corresponding homologous stretches. The positions and names of the primers used to amplify the fusion loci from M. eumusae and M. musicola are marked with carets.

To answer the question of whether the presence of these loci was restricted to MAT1-1 isolates of M. fijiensis or whether they would also be present in M. fijiensis MAT1-2 isolates, primers were designed based upon the sequences of the predicted MAT1/2A and MAT1/2B fusion loci (Fig. 5). Furthermore, these primers were also used on MAT1-1 and MAT1-2 strains from the other two main constituents of the Sigatoka disease complex, M. musicola and M. eumusae. This led to the amplification of fragments corresponding to the MAT1/2A and MAT1/2B fusion loci from both MAT1-1 and MAT1-2 isolates from all three banana pathogens. In all three species, the MAT1/2A and MAT1/2B fusion loci found in MAT1-1 and MAT1-2 isolates were identical. The organization of both the MAT1/2A and the MAT1/2B fusion loci was highly conserved between the three Mycosphaerella species examined (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Finally, the released genome sequence of the related M. graminicola was searched for the presence of these fusion loci. Neither the MAT1/2A nor the MAT1/2B fusion locus was found within the M. graminicola genome.

DISCUSSION

Expansion of the mating-type locus.

Since the initial characterization of the idiomorphs of Cochliobolus heterostrophus (31), mating-type loci have been characterized for many other Dothideomycetes. Until now, a single gene per idiomorph has been found in all species examined (11). This is in contrast to the situation in Sordariomycetes and Leotiomycetes, where the mating-type loci often contain additional genes besides the MAT1-1-1 and MAT1-2-1 genes (11). However, our results clearly show that the mating-type loci of the three main constituents of the Sigatoka disease complex and other Mycosphaerella species deviate from the typical dothideomycetous pattern. First, the idiomorphs show an expansion in size compared to the idiomorphs of other Dothideomycetes or even other Mycosphaerellaceae (4, 16, 30, 31, 33). The idiomorph of M. graminicola is 2.8 kb, whereas the sizes of the M. fijiensis idiomorphs are 3.9 kb and 4.4 kb and the sizes of the M. musicola idiomorphs are 3.9 and 4.3 kb (Fig. 1). The failed attempts to obtain the 5′ flanking region of the M. eumusae MAT1-1 and MAT1-2 loci by chromosome walking indicate that the sizes of these idiomorphs are at least 5.1 and 6.1 kb, respectively. Second, in comparison to the other Dothideomycetes, the Mycosphaerella idiomorphs contain additional genes (MATORF1 and MATORF2) and exhibit a novel organization (Fig. 1). Homologs of MATORF2 were also identified in the published MAT1-1 idiomorphs of M. graminicola and S. passerinii, previously thought to adhere to the one gene per idiomorph rule (16, 33). Moreover, in these species, a homolog of MATORF1 was found outside the MAT1-1 and MAT1-2 idiomorphs.

The pattern of an expanded mating-type locus concomitant with the incorporation of flanking regions and genes inside the mating-type loci has also been described for Coccidioides immitis, C. posadasii, and, most strikingly, Cryptococcus neoformans (15, 19). It is suggested that the expansion of mating-type loci by the incorporation of adjacent genes could represent a step in the evolution toward sex chromosomes (14, 19). In C. neoformans, the idiomorph is greatly expanded (>100 kb) and contains extensive rearrangements of genes between the mating types. For instance, the C. neoformans RP041α and RP041a genes are highly similar (97%) but are organized in opposite directions. This is strikingly similar to the observed similarity and inversion of MATORF1 and MATORF2 in the mating-type loci of M. eumusae, M. fijiensis, and M. musicola.

Presence and expression of MATORF1 and MATORF2.

The newly identified MATORF1 and MATORF2 are found only in the Mycosphaerellaceae. BLAST analyses indicated the presence of a homolog only in Passalora fulva, which also belongs to the Mycosphaerellaceae. A reexamination of the published mating-type loci of S. passerinii and M. graminicola, both members of the Mycosphaerellaceae (34), also revealed the presence of these ORFs (Fig. 1). Furthermore, additional studies aimed at the characterization of mating-type loci of the homothallic M. musae revealed the presence of MATORF2 in close association with a mating-type gene (unpublished data). Analysis of the proteins encoded by MATORF1 and MATORF2 indicated the presence of several conserved protein motifs with no known counterparts present in the databases (data not shown). These motifs might be used to design specific primers that can be used to test whether these genes are indeed specific for the Mycosphaerellaceae and potentially might yield a Mycosphaerellaceae-specific barcode.

The results of the RT-PCR experiments showed that both MATORF1 and MATORF2 of M. fijiensis are expressed and thus are not pseudogenes. A striking feature is the observed mating-type-dependent expression of these genes: MATORF1 is expressed in the MAT1-2 isolate and MATORF2 in the MAT1-1 isolate. This mating-type-dependent expression was observed under conditions nonconducive for mating. It would be interesting to see if and how the expression of MATORF1 and MATORF2 is regulated during mating. Such studies could also validate the predicted gene models for MAT1-1-1 and MAT1-2-1. Unfortunately, several attempts to cross complementary isolates in vitro proved unsuccessful. The mating-type-dependent expression can be well explained by the genomic organization within the idiomorphs and the assumptions that MATORF2 and MAT1-1-1 are under the control of a bidirectional promoter and that a similar-acting bidirectional promoter region is controlling MATORF1 and MAT1-2-1 (Fig. 1). To address this properly, promoter studies need to be performed. It is not clear whether the location of MATORF1 and MATORF2 near the mating-type genes is meaningful in relation to a function in sexual development or mating. Currently, experiments are under way to generate MATORF1/MATORF2 knockout mutants to assess their function.

In contrast to the situation in M. graminicola and S. passerinii, the interspecies homology of both MATORF1 and MATORF2 in the three banana pathogens examined was higher than the intraspecies homology. This looks like an example of trans-specific polymorphism (polymorphisms that are maintained in populations through speciation events) and confirms the common evolutionary history for M. eumusae, M. fijiensis, and M. musicola (3). trans-specific polymorphisms are distinguished by alleles from a species being less related to alternate alleles from the same species than to alleles from other species (22, 25). This is regularly found to occur on self-incompatibility loci (such as mating-type loci) and has recently been shown for the pheromone receptors pr-MatA1 and pr-MatA2 in Microbotryum spp. (13). trans-specific polymorphisms are considered to be maintained primarily by balancing selection (25). We hypothesize that after the incorporation of MATORF1 and MATORF2 into the mating-type region of an ancestor species, balancing selection exerted strong pressure, as mating can only occur between individuals with different idiomorphs. Consequently, after speciation, the intraspecies homology is lower than the interspecies homology.

Members of the Sigatoka disease complex contain additional loci of fused mating-type-like genes.

The amplification of fragments from an M. fijiensis MAT1 isolate using MAT1-2-1-specific primers, as well as from an M. fijiensis MAT2 isolate using MAT1-1-1-specific primers, revealed the presence of two loci containing both MAT1-1-1 and MAT1-2-1 sequences. Homologs of these loci were also present in M. eumusae and M. musicola. Furthermore, preliminary results of PCR amplification with a specific primer set for the fused mating-type loci reveal that these loci are also present in other closely related Pseudocercospora spp. from banana, viz., P. longispora, P. indonesiana, and P. assamensis, which, based on organismal gene phylogeny, display the same pattern of evolutionary history (3). Attempts to amplify the fused mating-type loci from genomic DNA isolated from other Mycosphaerella species occurring on banana, e.g., the homothallic species M. musae and M. thailandica and the heterothallic M. citri (data not shown), or an in silico analysis of the publicly available genome of the related M. graminicola were unsuccessful. These results suggest that the presence of these loci is restricted to a monophyletic clade of Mycosphaerella spp. occurring on banana. This clade contains the three major banana pathogens and the three above-mentioned Pseudocercospora spp. It is doubtful that MAT1/2A and MAT1/2B are true genes since no clear gene models could be predicted. However, if the fusion loci comprise functional genes, they will probably not function as mating-type genes, as no HMG box domains and only a partial α-domain (in MAT1/2A) were present.

The presence of additional MAT loci has been described in the homothallic euascomycete Neosartorya fischeri, where a MAT2 region, including flanking nonfunctional DNA lyase (APN1) and cytoskeleton assembly control (SLA2) sequences, became incorporated into a genome already containing a functional MAT1 region, thereby resulting in a homothallic mating system (27). However, the apparent MAT1/MAT2 recombinations that resulted in two distinct shuffled MAT1/2 fusion loci in the banana pathogens are novel findings. An explanation for the observed presence and structure of the MAT1/2 fusion loci could be the occurrence of unequal crossover events within the idiomorph of a heterothallic ancestor. These crossover events might have occurred within the inverted regions present within the idiomorphs, and thus, within MATORF1 and MATORF2.

Evolution of the Mycosphaerella MAT loci.

Taken as a whole, these data suggest great evolutionary dynamics acting at the MAT loci of Mycosphaerella species. This evolutionary flexibility might underlie the huge diversity of this fungal genus that comprises several thousands of species (9).

Based upon the results obtained, we propose the following working model for the evolution of the Mycosphaerella MAT loci. In a hypothetical Mycosphaerella ancestor, both MATORF1 and MATORF2 were present adjacent to the idiomorphs. In a MAT1-2 ancestor of the M. graminicola/S. passerinii lineage, MATORF2 was deleted. This deletion resulted in sequence divergence between the MAT1-1 and MAT1-2 idiomorphs, and thus, MATORF2 became incorporated into the MAT1-1 idiomorph.

In the “banana” Mycosphaerella lineage, an inversion of MAT1-1 or MAT1-2 plus flanking genes occurred. This expanded the area of nonhomology between the MAT1-1 and MAT1-2 strains. Consequently, the former non-MAT genes MATORF1 and MATORF2 became incorporated into the idiomorphs, and both genes have since undergone independent evolution in the MAT1-1 and MAT1-2 loci. A subsequent inversion of MAT1-1-1 or MAT1-2-1 would then result in the MAT organization observed in the banana pathogens. In the “banana” lineage, multiple additional recombination events resulted in the occurrence of the two additional nonfunctional fused mating-type loci. Finally, this common ancestor gradually split into M. fijiensis, M. eumusae, and M. musicola, which have undergone further minor modifications at the MAT locus (the extension in size in M. eumusae). Currently, the organization of MAT loci of additional Mycosphaerella species is being characterized to test this scenario of MAT locus evolution.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Marizeth Groenewald, Ewald Groenewald, and Lisette Haazen are thanked for technical help and scientific discussions. We acknowledge the Dutch Mycosphaerella group for valuable discussions.

Mahdi Arzanlou was funded by the Ministry of Science, Research, and Technology of the Islamic Republic of Iran.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 13 November 2009.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://ec.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A. Schaffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang, W. Miller, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arzanlou, M., E. C. A. Abeln, G. H. J. Kema, C. Waalwijk, J. Carlier, I. de Vries, M. Guzman, and P. W. Crous. 2007. Molecular diagnostics for the Sigatoka disease complex of banana. Phytopathology 97:1112-1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arzanlou, M., J. Z. Groenewald, R. A. Fullerton, E. C. A. Abeln, J. Carlier, M. F. Zapater, I. W. Buddenhagen, A. Viljoen, and P. W. Crous. 2008. Multiple gene genealogies and phenotypic characters differentiate several novel species of Mycosphaerella and related anamorphs on banana. Persoonia 20:19-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barve, M. P., T. Arie, S. S. Salimath, F. J. Muehlbauer, and T. L. Peever. 2003. Cloning and characterization of the mating type (MAT) locus from Ascochyta rabiei (teleomorph: Didymella rabiei) and a MAT phylogeny of legume-associated Ascochyta spp. Fungal Genet. Biol. 39:151-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carlier, J., M. F. Zapater, F. Lapeyre, D. R. Jones, and X. Mourichon. 2000. Septoria leaf spot of banana: a newly discovered disease caused by Mycosphaerella eumusae (anamorph Septoria eumusae). Phytopathology 90:884-890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Conde-Ferraez, L., C. Waalwijk, B. Canto-Canche, G. H. J. Kema, P. W. Crous, A. C. James, and E. C. A. Abeln. 2007. Isolation and characterization of the mating type locus of Mycosphaerella fijiensis, the causal agent of black leaf streak disease of banana. Mol. Plant Pathol. 8:111-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coppin, E., R. Debuchy, S. Arnaise, and M. Picard. 1997. Mating types and sexual development in filamentous ascomycetes. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 61:411-428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cozijnsen, A. J., and B. J. Howlett. 2003. Characterisation of the mating-type locus of the plant pathogenic ascomycete Leptosphaeria maculans. Curr. Genet. 43:351-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crous, P. W., A. Aptroot, J.-C. Kang, U. Braun, and M. J. Wingfield. 2000. The genus Mycosphaerella and its anamorphs. Stud. Mycol. 45:107-121. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crous, P. W., and X. Mourichon. 2002. Mycosphaerella eumusae and its anamorph Pseudocercospora eumusae spp. nov.: causal agent of eumusae leaf spot disease of banana. Sydowia 54:35-43. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Debuchy, R., and B. G. Turgeon. 2006. Mating-type structure, evolution and function in Euascomycetes, p. 293-323. In U. Kues and R. Fischer (ed.), The Mycota, vol. 1. Growth, differentiation and sexuality, 2nd ed. Springer, Berlin, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dereeper, A., V. Guignon, G. Blanc, S. Audic, S. Buffet, F. Chevenet, J. F. Dufayard, S. Guindon, V. Lefort, M. Lescot, J. M. Claverie, and O. Gascuel. 2008. Phylogeny.fr: robust phylogenetic analysis for the non-specialist. Nucleic Acids Res. W465-W469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Devier, B., G. Aguileta, M. E. Hood, and T. Giraud. 2009. Ancient trans-specific polymorphism at pheromone receptor genes in Basidiomycetes. Genetics 181:209-223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fraser, J. A., and J. Heitman. 2004. Evolution of fungal sex chromosomes. Mol. Microbiol. 51:299-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fraser, J. A., J. E. Stajich, E. J. Tarcha, G. T. Cole, D. O. Inglis, A. Sil, and J. Heitman. 2007. Evolution of the mating type locus: insights gained from the dimorphic primary fungal pathogens Histoplasma capsulatum, Coccidioides immitis, and Coccidioides posadasii. Eukaryot. Cell 6:622-629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goodwin, S. B., C. Waalwijk, G. H. J. Kema, J. R. Cavaletto, and G. Zhang. 2003. Cloning and analysis of the mating-type idiomorphs from the barley pathogen Septoria passerinii. Mol. Genet. Genomics 269:1-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Groenewald, M., J. Z. Groenewald, T. C. Harrington, E. C. A. Abeln, and P. W. Crous. 2006. Mating type gene analysis in apparently asexual Cercospora species is suggestive of cryptic sex. Fungal Genet. Biol. 43:813-825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones, D. R. 2003. The distribution and importance of the Mycosphaerella leaf spot diseases of bananas, p. 25-41. In L. Jacome, P. Lepoivre, R. Marin, R. Ortiz, R. A. Romero, and J. V. Escalant (ed.), Mycosphaerella leaf spot diseases of bananas: present status and outlook. INIBAP, San José, Costa Rica.

- 19.Lengeler, K. B., D. S. Fox, J. A. Fraser, A. Allen, K. Forrester, F. S. Dietrich, and J. Heitman. 2002. Mating-type locus of Cryptococcus neoformans: a step in the evolution of sex chromosomes. Eukaryot. Cell 1:704-718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin, X., and J. Heitman. 2007. Mechanisms of homothallism in fungi and transitions between heterothallism and homothallism, p. 35-57. In J. Heitman, J. Kronstad, J. W. Taylor, and L. A. Casselton (ed.), Sex in fungi. Molecular determination and evolutionary implications. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 21.Marin, D. H., R. A. Romero, M. Guzman, and T. B. Sutton. 2003. Black Sigatoka: an increasing threat to banana cultivation. Plant Dis. 87:208-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.May, G., F. Shaw, H. Badrane, and X. Vekemans. 1999. The signature of balancing selection: fungal mating compatibility gene evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96:9172-9177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Metzenberg, R. L., and N. L. Glass. 1990. Mating type and mating strategies in Neurospora. Bioessays 12:53-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nolting, N., and S. Poggeler. 2006. A MADS box protein interacts with a mating-type protein and is required for fruiting body development in the homothallic ascomycete Sordaria macrospora. Eukaryot. Cell 5:1043-1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Richman, A. 2000. Evolution of balanced genetic polymorphism. Mol. Ecol. 9:1953-1963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rivas, G. G., M. F. Zapater, C. Abadie, and J. Carlier. 2004. Founder effects and stochastic dispersal at the continental scale of the fungal pathogen of bananas Mycosphaerella fijiensis. Mol. Ecol. 13:471-482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rydholm, C., P. S. Dyer, and F. Lutzoni. 2007. DNA sequence characterization and molecular evolution of MAT1 and MAT2 mating-type loci of the self-compatible ascomycete mold Neosartorya fischeri. Eukaryot. Cell 6:868-874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Salamov, A. A., and V. V. Solovyev. 2000. Ab initio gene finding in Drosophila genomic DNA. Genome Res. 10:516-522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 30.Stergiopoulos, I., M. Groenewald, M. Staats, P. Lindhout, P. W. Crous, and P. J. G. M. De Wit. 2007. Mating-type genes and the genetic structure of a world-wide collection of the tomato pathogen Cladosporium fulvum. Fungal Genet. Biol. 44:415-429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Turgeon, B. G., H. Bohlmann, L. M. Ciuffetti, S. K. Christiansen, G. Yang, W. Schafer, and O. C. Yoder. 1993. Cloning and analysis of the mating-type genes from Cochliobolus heterostrophus. Mol. Gen. Genet. 238:270-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Turgeon, B. G., and O. C. Yoder. 2000. Proposed nomenclature for mating type genes of filamentous ascomycetes. Fungal Genet. Biol. 31:1-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Waalwijk, C., O. Mendes, E. C. P. Verstappen, M. A. de Waard, and G. H. J. Kema. 2002. Isolation and characterization of the mating-type idiomorphs from the wheat septoria leaf blotch fungus Mycosphaerella graminicola. Fungal Genet. Biol. 35:277-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ware, S. B., E. C. P. Verstappen, J. Breeden, J. R. Cavaletto, S. B. Goodwin, C. Waalwijk, P. W. Crous, and G. H. J. Kema. 2007. Discovery of a functional Mycosphaerella teleomorph in the presumed asexual barley pathogen Septoria passerinii. Fungal Genet. Biol. 44:389-397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wirsel, S., B. Horwitz, K. Yamaguchi, O. C. Yoder, and B. G. Turgeon. 1998. Single mating type-specific genes and their 3′ UTRs control mating and fertility in Cochliobolus heterostrophus. Mol. Gen. Genet. 259:272-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yokoyama, E., M. Arakawa, K. Yamagishi, and A. Hara. 2006. Phylogenetic and structural analyses of the mating-type loci in Clavicipitaceae. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 264:182-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yun, S. H., M. L. Berbee, O. C. Yoder, and B. G. Turgeon. 1999. Evolution of the fungal self-fertile reproductive life style from self-sterile ancestors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96:5592-5597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.