Abstract

Genes encoding key enzymes of the ectoine biosynthesis pathway in the halotolerant obligate methanotroph Methylomicrobium alcaliphilum 20Z have been shown to be organized into an ectABC-ask operon. Transcription of the ect operon is initiated from two promoters, ectAp1 and ectAp2 (ectAp1p2), similar to the σ70-dependent promoters of Escherichia coli. Upstream of the gene cluster, an open reading frame (ectR1) encoding a MarR-like transcriptional regulator was identified. Investigation of the influence of EctR1 on the activity of the ectAp1p2 promoters in wild-type M. alcaliphilum 20Z and ectR1 mutant strains suggested that EctR1 is a negative regulator of the ectABC-ask operon. Purified recombinant EctR1-His6 specifically binds as a homodimer to the putative −10 motif of the ectAp1 promoter. The EctR1 binding site contains a pseudopalindromic sequence (TATTTAGT-GT-ACTATATA) composed of 8-bp half-sites separated by 2 bp. Transcription of the ectR1 gene is initiated from a single σ70-like promoter. The location of the EctR1 binding site between the transcriptional and translational start sites of the ectR1 gene suggests that EctR1 may regulate its own expression. The data presented suggest that in Methylomicrobium alcaliphilum 20Z, EctR1-mediated control of the transcription of the ect genes is not the single mechanism for the regulation of ectoine biosynthesis.

Mineralization of small saline and soda lakes can vary significantly depending on the season and weather conditions. The ability to rapidly adjust intracellular concentrations of key osmolytes (also known as compatible solutes) to changes in external salinity is an important property of microorganisms inhabiting these biotopes (8, 18, 34). Ectoine (1,4,5,6-tetrahydro-2-methyl-4-pyrimidine carboxylic acid) was found to be a major compatible solute in many halophilic or halotolerant bacteria isolated from alkaline, moderately hypersaline environments (14). This organic solute can be synthesized de novo or taken up from the environment when available (15, 18). The biochemistry and genetics of ectoine synthesis have been described for several bacteria (15, 28, 29, 32). However, little is known about the transcriptional regulation of the ectoine biosynthetic pathway. Comprehensive analysis of the ectoine gene cluster ectABC in Chromohalobacter salexigens showed four putative transcription initiation sites upstream of the ectA start codon. Two σ70-dependent, one σS-dependent, and one σ32-dependent promoter were identified and shown to be involved in ectABC transcription in this bacterium (6). Transcription of the ectA, ectB, and ectC genes from Marinococcus halophilus was initiated from three individual σ70/σA-dependent promoter sequences located upstream of each gene (3). In Bacillus pasteurii, the ectABC genes are organized in a single operon preceded by a typical σA-dependent promoter region (21).

The halotolerant obligate methanotroph Methylomicrobium alcaliphilum 20Z is capable of growth at a salinity as high as 2 M NaCl (19). It was demonstrated that in response to the elevated salinity of the growth medium, M. alcaliphilum cells accumulate ectoine as a major osmoprotective compound (20). The ectoine biosynthesis pathway in M. alcaliphilum 20Z is similar to the pathway employed by halophilic/halotolerant heterotrophs and involves three specific enzymes: diaminobutyric acid (DABA) aminotransferase (EctB), DABA acetyltransferase (EctA), and ectoine synthase (EctC) (7, 21, 24, 30, 32, 49). In M. alcaliphilum 20Z, the ectoine biosynthetic genes were shown to be organized in the ectABC-ask operon containing the additional ask gene, encoding aspartokinase (32). Here we describe the transcriptional organization of the ectoine biosynthetic genes in M. alcaliphilum 20Z. We identify a new MarR-like transcriptional regulator (EctR1) and show that EctR1 represses the expression of the ectABC-ask operon from the ectAp1 promoter by binding at the putative −10 sequence. These results demonstrate the presence of a new, previously uncharacterized regulatory system for ectoine biosynthesis in the salt-tolerant methanotroph.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

The M. alcaliphilum and Escherichia coli strains, plasmids, and primers used in this study are listed in Tables S1 and S2 in the supplemental material. M. alcaliphilum strains were grown at 30°C under a methane-air atmosphere (1:1) or in the presence of 0.5% (vol/vol) methanol in a mineral salt medium containing 1%, 3%, or 6% NaCl (17, 19). Escherichia coli strains were routinely cultivated at 37°C in Luria-Bertani medium (2). The following antibiotic concentrations were used: tetracycline (Tet), 12.5 μg ml−1; kanamycin (Kan), 100 μg ml−1; ampicillin (Amp), 100 μg ml−1.

Identification of the ectR1 gene.

Inverse PCR was used to amplify the upstream region of the ectABC-ask operon. Approximately 200 ng of the M. alcaliphilum DNA was digested with BstACI, and the resulting fragments were self-ligated overnight at 16°C in 100 μl of reaction mixture with 2 U T4 DNA ligase, followed by precipitation in ethanol. An aliquot of ligation products was used as a template in PCR with primers 20PROr and TraX (see Table S2 in the supplemental material), designed on the basis of previously identified sequences of the ectoine biosynthesis genes in M. alcaliphilum 20Z (GenBank accession no. DQ016501). The resulting PCR product of ∼1 kb was sequenced using the same primers.

Construction of an ectR1 mutant.

Genomic fragments containing the ectR1 upstream (724-bp) and downstream (607-bp) flanks were PCR amplified, cloned into pCR2.1 (Invitrogen), excised by AatII/KpnI (ectR1 upstream flank) or SacI/SacII (ectR1 downstream flank), and then subcloned into pCM184 (26) using appropriate restriction sites (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). The resulting plasmid (pEBP01) was transformed into E. coli S17-1, and the resulting donor strain was mated with wild-type M. alcaliphilum in a biparental mating. Biparental matings were performed at 30°C for 48 h on mating medium (MM), consisting of mineral salt medium (as described in reference 17, except that the carbonate salts were removed and the pH was adjusted to 7.6) supplemented with 10% nutrient broth (BD Difco) and methanol (5 mM) and containing 0.3% NaCl. Cells were then washed with sterile medium and plated on selective medium, consisting of alkaline mineral medium (pH 9.5) containing 3% NaCl and supplemented with methanol (50 mM) and, if needed, Kan (100 μg ml−1). High pH and high salinity were used for E. coli counterselection. The Kanr recombinants were selected on methanol plates and checked for resistance to Tet (25 μg ml−1). Tet-sensitive (Tets) recombinants were chosen as possible double-crossover recombinants. Double-crossover mutants were further verified by diagnostic PCR with primers specific to the insertion sites.

Construction of an ect-promoter fusion.

The 352-bp fragment containing the ectR1-ectA intergenic region was amplified by PCR (the primers are shown in Table S2) and cloned into the pCR2.1 vector. The fragments were subsequently excised by PstI and BamHI and then cloned into the pTSGex promoter probe vector (42), resulting in a construct (pEBP1) containing the respective DNA fragments upstream of the promoterless reporter gene gfp. The resulting constructs were transformed into E. coli S17-1 (39) and then transferred into M. alcaliphilum 20Z and the EBPR01 mutant via conjugation using plasmid pRK2073 as a helper (11). After 48 h of incubation on MM, cells were plated on selective medium, consisting of alkaline mineral medium (pH 9.5) containing 3% NaCl and supplemented with methanol (25 mM), Tet (25 μg ml−1), and, if needed, Kan (100 μg ml−1).

Fluorescence measurements.

Validation of the ectAp1p2-gfp reporter system and fluorimetry-based gene expression analysis were performed on wild-type and mutant strains of M. alcaliphilum grown on alkaline mineral medium (19) supplemented with methanol (25 mM), Tet (25 μg ml−1), and 1, 3, or 6% NaCl to mid-exponential phase (optical density at 600 nm [OD600], 0.5 to 0.6). After growth, the cultures were centrifuged at 4,500 × g for 15 min at 21°C. Cells were washed once with the corresponding medium without Tet and were resuspended in the same medium at an OD600 of approximately 0.4 to 0.5. Fluorescence measurements were carried out with a Shimadzu RF-5301PC fluorimeter as described previously (42). Green fluorescent protein (GFP) UV excitation was conducted at 405 nm, and emissions were monitored at 509 nm. Promoter activities were calculated as previously described (27) by plotting fluorescence versus OD600.

Enzymatic assays.

Wild-type or mutant strains of M. alcaliphilum were grown to mid-exponential phase (OD600, 0.5 to 0.6) in alkaline mineral medium (14) containing 1%, 3%, or 6% NaCl and supplemented with methanol (25 mM). Cells were collected by centrifugation at 4,500 × g for 15 min at 4°C. Extracts were prepared, and diaminobutyric acid acetyltransferase activity was measured, as previously described (32).

RNA isolation and primer extension assay.

To determine the first transcribed nucleotides for the ectABC-ask operon, primer extension assays were performed using RNA isolated from salt-stressed cells. M. alcaliphilum 20Z was grown to an OD600 of 0.4 in the presence of 1% (wt/vol) NaCl. Expression of the ectABC-ask operon was induced by addition of NaCl up to a final concentration of 6% (wt/vol) followed by incubation for 1 h. RNA was isolated as described previously (32). RNA (10 μg) was mixed with deoxynucleoside triphosphates (1 mmol) and 2 pmol of 32P-end-labeled primer ST2 (see Table S2 in the supplemental material), which anneals to the ectA gene from position +6 to position +30, in a total volume of 12 μl. The mixture was heated for 5 min at 70°C and then quickly chilled on ice. Actinomycin D (final concentration, 1 μg/ml), 4 μl (5×) reaction buffer for RevertAid H Minus Moloney murine leukemia virus (M-MuLV) reverse transcriptase (Fermentas, Lithuania), and 40 U of RiboLock RNase inhibitor (Fermentas) were subsequently added. The mixture was incubated at 50°C for 1 min before the addition of 200 U of RevertAid H Minus M-MuLV reverse transcriptase (Fermentas). The primer extension reaction was conducted at 43°C for 60 min and was stopped by enzyme inactivation at 70°C for 15 min. The primer extension products were precipitated by ethanol. The same primer (ST2) was used to produce sequence ladders by using the fmol DNA cycle sequencing system (Promega) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. Primer extension products and sequence ladders were separated on a 6% urea-polyacrylamide sequencing gel. To determine the transcription start site for the ectR1 gene, a primer extension reaction was carried out as described above using RNA obtained from cells grown with 1% (wt/vol) NaCl and 32P-end-labeled primer TSR1 (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). Dried sequencing gels were visualized using a Cyclone Storage Phosphor system (Packard Instruments Co.).

The ability of the E. coli transcriptional system to recognize the promoter sequence of the ect operon of M. alcaliphilum 20Z was demonstrated by primer extension analysis. The primer extension reaction was performed using RNA extracted from E. coli XL1-Blue cells transformed with recombinant plasmid pHSGectABC, carrying the nucleotide sequence from bp 301 upstream of the ectA gene to bp 173 downstream of the ectC gene, and grown in M9 minimal medium with 4% NaCl and glucose (32, 38).

Northern blotting.

Northern blot analyses of the ectR1 gene and ectABC-ask operon transcripts were performed as described previously (36). RNA was isolated from M. alcaliphilum cells grown either with 1% or 6% NaCl or with salt stressed cells. Total RNA was separated on a formaldehyde-containing agarose gel and was transferred to a positively charged nylon membrane (Hybond-N+; Amersham Biosciences) using a Trans-Blot SD semidry electrophoretic transfer cell (Bio-Rad) according to the manufacturer's instruction. Hybridization was performed under high-stringency conditions (50°C, 50% formamide) with gene-specific 32P-labeled probes for the ectR1 and ask genes, which had been prepared by PCR using [α-32P]dATP with oligonucleotide pairs ectR1C-20PROr and AspIF-RPHy (see Table S2 in the supplemental material), respectively. Double-stranded DNA probes were denatured at 100°C for 5 min before hybridization.

Heterologous expression of EctR1 and purification of the recombinant protein.

The ectR1 gene was amplified by PCR from chromosomal M. alcaliphilum 20Z DNA by using Pfu DNA polymerase (Fermentas, Lithuania) and primers ectR1N and ectR1C (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). The amplified fragment (556 bp) was digested by NdeI and HindIII and was ligated into the pET-22b(+) vector (Novagen), resulting in the pETectR1-his construct.

E. coli BL21(DE3) cells transformed with pETectR1-his were grown overnight in 2 ml of LB medium containing ampicillin (100 μg/ml). The overnight culture was placed in 200 ml of fresh LB medium with ampicillin and was grown at 37°C to an OD600 of 0.3 to 0.5. Protein expression was then induced with 0.5 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). After 3 h of incubation, cells were harvested by centrifugation and disrupted by sonication in 5 ml lysis buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 500 mM NaCl, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) in an MSE (United Kingdom) sonifier. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 15,000 × g and 4°C for 30 min. EctR1-His6 was purified with a QIAexpress nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid Fast Start kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Fractions were collected and analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by Coomassie blue staining. The fractions with the majority of EctR1-His6 were combined and dialyzed overnight at 4°C against 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) buffer containing 400 mM NaCl and were then stored at 4°C. Protein concentrations were determined by the Lowry assay (37).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA).

A DNA fragment of 213 bp, corresponding to the ect promoter region, was amplified by PCR using primer RT20Z and 32P-end-labeled primer F1. One picomole of the labeled DNA fragment (10,000 cpm) was incubated for 15 min at room temperature in 20 μl of binding buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 10 mM MgCl2, 200 mM KCl) with increasing amounts of pure EctR1-His6 (from 1 to 320 pmol) and 0.5 μg of sheared herring sperm DNA (Sigma). For the competition assay, unlabeled DNA was added to the reaction mixture after incubation with the labeled fragment. Samples were analyzed by native gel (6% polyacrylamide) electrophoresis in 1× Tris-borate-EDTA buffer (36).

DNase I footprinting.

A DNA fragment containing the promoter regions of the ectR1 gene and the ectABC-ask operon was amplified using a combination of an unlabeled primer (F1) and primer RT20Z labeled with T4 polynucleotide kinase and [γ-32P]dATP. The PCR product was purified from a 6% native polyacrylamide gel by the “crush-and-soak” method (36). Labeled PCR products (about 2 pmol) were incubated at room temperature with 4 μg of purified EctR1-His6 in a 30-μl reaction mixture containing binding buffer (see above), 20 μg/ml bovine serum albumin (BSA), and 0.25 μg of sonicated herring sperm DNA. After 20 min of incubation, 0.1 mM CaCl2 and 0.8 U DNase I (Fermentas, Lithuania) were added. The DNase I digestion reaction proceeded for 1 min at room temperature and was terminated by the addition of 100 μl of stop solution (192 mM sodium acetate, 50 mM EDTA, 0.14% SDS, 1 μg glycogen). DNA fragments were extracted by phenol-chloroform and precipitated with ethanol. Samples were separated alongside Maxam-Gilbert (G+A) chemical sequencing ladders (36) by 6% polyacrylamide-8 M urea gel electrophoresis.

Size exclusion chromatography.

Gel filtration chromatography of recombinant EctR1 was performed on an Ultrogel AcA 44 column (1.5 cm by 60 cm; LKB, Sweden) equilibrated with 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) containing 200 mM KCl and 10 mM MgCl2 at a flow rate of 0.2 ml/min. For analysis of the EctR1-His6-DNA complexes, 80 pmol of EctR1-His6 was incubated for 20 min at room temperature with 1 pmol of the 32P-end-labeled double-stranded oligonucleotide RBS, obtained by annealing complementary primers RBS1 and RBS2 (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). Gel filtration chromatography of the EctR1-His6-DNA complexes was performed as indicated. Radioactive fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and native PAGE to verify the presence of EctR1-His6 and EctR1-His6-DNA complexes, respectively. The apparent molecular masses of EctR1-His6 and EctR1-His6-DNA complexes were estimated using the partition coefficient Kav, calculated as (Ve − V0)/(Vt − V0) versus the log of the molecular masses of the standard proteins (RNase A, 13.7 kDa; chymotrypsinogen A, 25 kDa; DNase, 31 kDa; ovalbumin, 45 kDa; BSA, 66 kDa). V0 and Ve are the void and elution volumes, respectively, and Vt is the total column volume.

General DNA manipulations.

Chromosomal DNA from M. alcaliphilum 20Z was prepared as described previously (17). Isolation of plasmid DNA from E. coli and transformations were carried out by standard techniques as described previously (36). Restriction endonucleases, T4 DNA ligase, T4 polynucleotide kinase, and Taq and Pfu DNA polymerases were obtained from NBI Fermentas (Lithuania) and were used according to the manufacturer's instructions. DNA fragments were purified using “Wizard SV Gel and PCR Clean-Up System” columns (Promega) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Nucleotide sequences were determined by using an automatic ABI Prism DNA sequencer, model 310 (Perkin-Elmer). DNA and peptide sequence homologies were analyzed using BLAST (http://au.expasy.org/sprot/). Sequence alignment was performed using Vector NTI, version 9 (Invitrogen). The secondary structure of EctR1 was predicted using the PSIPRED Protein Structure Prediction server (http://bioinf.cs.ucl.ac.uk/psipred/psiform.html). Multiple alignments were done using the Clustal X program (45).

RESULTS

Identification of a new gene upstream of the ectABC-ask operon in M. alcaliphilum 20Z.

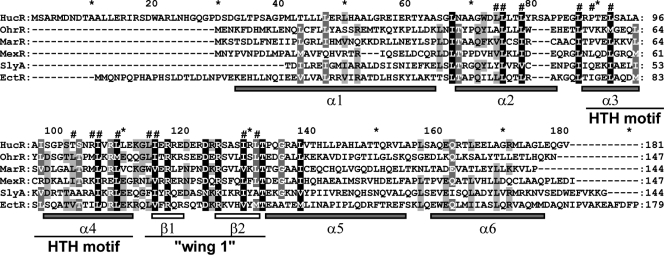

In M. alcaliphilum 20Z, the ectoine biosynthesis genes are organized in the ectABC-ask operon (32). A partial sequence of an additional open reading frame (orf1), in reverse orientation relative to the ectABC-ask cluster, was identified upstream of the ectA gene. The whole sequence of orf1 was determined by using inverse PCR. A BLAST search suggested that the orf1 region encodes a putative MarR-type transcriptional regulator. Multiple sequence alignments of the predicted protein with characterized MarR regulators indicated that Orf1 has the highest identities with OhrR (20.5%), MarR (15%), and EmrR (19.6%) from E. coli (10, 13, 23, 25, 41, 43, 44), PecS (18.6%) from Erwinia chrysanthemi strain 3937 (33), MexR (17.8%) from Pseudomonas aeruginosa (12, 31, 40), and SlyA (15.6%) from Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (41, 48). Downstream of the orf1 stop codon (38 bp), a stem-loop-like structure that might function as a rho-independent terminator (with a calculated free energy of −12.4 kcal/mol) was found. In view of the opposite orientation of orf1 with respect to the ectABC-ask operon and the sequence homology of the gene product with MarR family regulators, orf1 was tentatively designated ectR1 (for “ectoine biosynthesis regulator”). The predicted EctR1 protein consists of 180 amino acids and has a molecular mass of 20.6 kDa and a pI of 7.17. An amino acid sequence similar to that of the conserved DNA binding domain (a winged helix-turn-helix [HTH] motif) of the MarR family of transcriptional regulators was identified in the central part of putative EctR1 (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Multiple sequence alignment of M. alcaliphilum 20Z EctR1 and representative MarR family members: SlyA, a regulator of virulence factors from Enterococcus faecalis (NCBI accession no. 1LJ9_A) (41); OhrR, a repressor of an organic hydroperoxide resistance determinant from Bacillus subtilis (13); MarR, a regulator of multiple antibiotic resistance from E. coli (P27245) (1); MexR, a multidrug efflux system transcriptional repressor from Pseudomonas aeruginosa (AAO40258) (22); and HucR, a repressor of the uricase genes from Deinococcus radiodurans (2FBK_A) (47). The alignment was generated using Clustal X, and the amino acid numbering was based on the HucR sequence. Number signs (#) above the sequence indicate residues identified from the MarR crystal structure as forming the hydrophobic core of the monomeric DNA binding domain (1). The HTH DNA-binding motif and flanking “wing 1” region identified from the MarR crystal structure are indicated below the alignment. Shaded and open bars represent alpha-helices and beta-sheets, respectively.

Identification of the ectABC-ask and ectR1 transcription units and the effect of medium salinity on their expression.

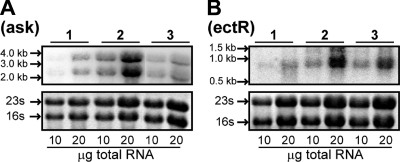

To determine the sizes and expression levels of the ect operon and ectR1 gene transcripts, we used Northern hybridization with probes corresponding to the 3′-proximal sequences of the ask and ectR1 genes. For this purpose, RNA was extracted from M. alcaliphilum 20Z cells grown in mineral medium with either 1% NaCl, 6% NaCl, or salt-stressed cells. Cells defined as “salt-stressed cells” were grown with 1% NaCl to an OD600 of 0.5 to 0.6 and were then incubated for 1 h at a higher salinity (6% NaCl). With the probe corresponding to the ask gene, two radiolabeled bands at about 4 and 2.3 kb were detected (Fig. 2A). The length of the 4-kb transcript was sufficient to carry the ectA, ectB, ectC, and ask genes on a polycistronic message. The presence of a 2.3-kb RNA band indicated that the ectC and ask genes (1,908-bp fragment) might be cotranscribed as an additional transcriptional unit from the promoter region located upstream of the ectC gene.

FIG. 2.

Northern blot analysis of ectABC-ask operon and ectR1 gene mRNAs. Total RNA was prepared either from M. alcaliphilum 20Z cells grown with 1% NaCl (lanes 1) or 6% NaCl (lanes 3) or with cells exposed for 1 h to an osmotic upshift from 1% NaCl to a final salt concentration of 6% NaCl (lanes 2). Increasing amounts of total RNA were resolved on a denaturing agarose gel, blotted onto a Hybond-N+ membrane, and hybridized with [α32P]dATP-labeled ask (A) or ectR1 (B) gene-specific probes. RNA ladders are indicated by arrows. rRNA (lower panels) was detected by ethidium bromide staining.

For the ectR1 probe, a single hybridization band was found under all growth conditions tested. The molecular size of the transcript (Fig. 2B) was calculated to be approximately 0.8 kb, which was larger than the expected length of a monocistronic transcript of the ectR1 gene (543 bp).

The abundance of the ectABC-ask transcripts was 30-fold higher in salt-stressed cells than in cells grown at 1% NaCl (Fig. 2). In cells of M. alcaliphilum 20Z grown at 6% NaCl, the level of ectABC-ask mRNA increased about 13-fold. The levels of transcription of ectR1 in salt-stressed cells and in cells grown at 6% NaCl also increased (5- and 3-fold, respectively).

Most halophilic/halotolerant heterotrophic bacteria prefer the accumulation of exogenous osmoprotectants to de novo synthesis. In general, the addition of an osmoprotectant (or its precursor) to the growth medium represses the biosynthesis of an endogenous solute (8, 18, 34). We examined the effect of exogenously provided organic solutes on the expression of the ectABC-ask operon by M. alcaliphilum 20Z during an osmotic upshift. Cultures grown at 1% NaCl were supplemented with ectoine (1 mM) or glycine betaine (1 mM) and were stressed by salt addition up to 6% NaCl. The activity of DABA acetyltransferase, an indicator of the induction of the ectoine biosynthesis pathway, was monitored after 1 and 3 h of incubation at high salinity. Cells incubated either alone or with added osmoprotectants demonstrated similar rates of l-diaminobutyric acid conversion (see Table S3 in the supplemental material). Thus, the addition of exogenous solutes has no noticeable effect on the induction of the ectoine biosynthesis pathway in M. alcaliphilum 20Z.

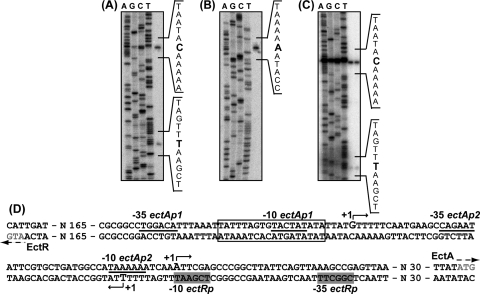

Identification of transcriptional start sites of the ectABC-ask operon and the ectR1 gene.

To map the transcriptional start sites of the ectABC-ask operon and the ectR1 gene, primer extension reactions were conducted with total-RNA samples isolated from salt-stressed cells. Two transcripts were detected (Fig. 3A). The start sites of the transcripts were mapped at bp 118 and bp 69 upstream of the ectA gene. This observation suggested that the ect operon is transcribed from two promoters, ectAp1 and ectAp2 (Fig. 3D). The potential ectAp1 promoter elements, TACTAT for the −10 and TGGACA for the −35 site with 16-bp spacing, match well with the consensus sequences (TATAAT and TTGACA) for a promoter recognized by the primary vegetative sigma factor, σ70 of E. coli (16). Moreover, ectAp1 displayed a TG motif as an upstream extension of the −10 box (35). The putative −10 sequence (TAAAAA) of ectAp2 showed identity to the σ70-dependent consensus for E. coli, while the putative −35 sequence (CAGAAT) matched two of the six nucleotides (Fig. 3D).

FIG. 3.

Determination of transcriptional start sites for the ectABC-ask operon and the ectR1 gene. Primer extension analyses were carried out with total RNA prepared from M. alcaliphilum 20Z cells (A and B) and E. coli cells (C) using primers complementary to the ectA (A and C) and ectR1 (B) genes as indicated in Materials and Methods. Primer-extended products were separated by electrophoresis under denaturing conditions alongside the products of sequencing reactions with the same primers. (D) Sequence of the ectR1-ectA intergenic region. Bent arrows indicate the transcriptional initiation sites of the ectABC-ask operon and the ectR1 gene. Putative promoter elements (−10 and −35 boxes) for the ectAp1 and ectAp2 promoters of the ectABC-ask operon are underlined. Putative −10 and −35 elements for the promoter of the ectR1 gene are shaded. The translational start codons for the ectA and ectR1 genes are indicated by arrows. The inverted repeat of the EctR1 binding site (see below) is boxed.

The transcriptional start site of the ectR1 gene was assigned to a position 250 bp upstream of the ATG translational initiation site. The sequence of the putative −10 box (TCGAAT) exhibited similarity with the −10 consensus sequence of the E. coli σ70-recognized promoter, while the putative −35 site of the ectR1p promoter does not resemble that of E. coli (Fig. 3B and D).

The primer extension analysis was also performed by using total RNA isolated from E. coli cells containing plasmid pHSG:ectABC, carrying the sequence of the ectABC genes and their promoter region. Two transcriptional start sites identical to those obtained from M. alcaliphilum 20Z were revealed (Fig. 3C). Hence, the ectAp1 and ectAp2 promoters are recognized by transcriptional systems in both strains M. alcaliphilum 20Z and E. coli XL1-Blue.

Null mutations in the ectR1 gene result in overexpression of the ectABC-ask operon.

In order to elucidate the function of EctR1 in the regulation of the ect operon, we constructed an ectR1 gene insertion mutant via allelic exchange. The growth rate of the ectR1 knockout strain (designated EBPR01) was similar to that of the wild type at 1, 3, and 6% NaCl, thus indicating that EctR1 is most likely not essential for activation of ect operon transcription in response to elevated salinity.

We further tested the expression of the ectoine biosynthesis genes in the ectR1 mutant via transcriptional fusions to a promoterless reporter gene, gfp. The ectA promoter region (352 bp) was amplified by PCR and cloned into the pTSGex vector. The plasmid carrying the ectAp1p2-gfp fusion was introduced into both wild-type M. alcaliphilum 20Z and EBPR01, and the resulting strains were assayed for gfp expression. At all salt concentrations tested, the activities of the ectAp1p2 promoter region were 2- to 3-fold higher in the strain lacking ectR1 than in the wild type (Table 1). The activities of DABA acetyltransferase, a key enzyme of the ectoine biosynthesis pathway, followed the same pattern: they were 2- to 6-fold higher in strain EBPR01 (Table 1). Thus, the mutation in the ectR1 gene resulted in derepression of the ect operon. The data indicated that, like most MarR family proteins, EctR1 acts as a negative transcriptional regulator. However, the expression of the ect operon was activated in response to high osmolarity of the growth medium in the mutant strain, thus indicating that EctR1 is not the sole regulator of the system.

TABLE 1.

Activities of the ectAp1p2-gfp promoter fusion and diaminobutyric acid acetyltransferase in wild-type and ectR1 mutant strains of M. alcaliphilum

| Salinity of the growth medium (% NaCl) | Activity with the indicated strain |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

ectAp1p2-gfp (RFU OD600−1 h−1)a |

DABA-acetyltransferase (nmol min−1 mg of protein−1) |

|||

| Wild type | EBPR01 | Wild type | EBPR01 | |

| 1 | 22 ± 2.3 | 65 ± 9 | 5 ± 1.2 | 33 ± 5.3 |

| 3 | 40 ± 5 | 95 ± 15 | 57 ± 7 | 200 ± 23 |

| 6 | 130 ± 25 | 220 ± 22 | 83 ± 11 | 150 ± 18 |

RFU, relative fluorescence units.

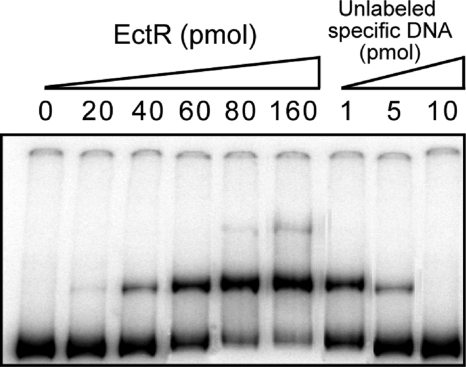

EctR1-His6 specifically binds to DNA fragments containing the ectAp1, ectAp2, and ectR1p promoters.

The coding region of ectR1 was cloned into the pET-22b(+) expression vector, and the resulting C-terminally His-tagged protein was overexpressed in E. coli. The recombinant protein, EctR1-His6, was purified to high homogeneity (data not shown). The molecular mass of EctR1 estimated by SDS-PAGE was about 23 kDa, which is in reasonable agreement with the predicted size (22.039 kDa) deduced from the amino acid sequence. To prove the specific binding of EctR1 to the promoter region of the ectABC-ask operon, an electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) was performed. A clear DNA shift was observed when 40 to 160 pmol of EctR1-His6 and 1 pmol of an end-labeled DNA fragment (213 bp) containing the ectAp1, ectAp2, and ectR1p promoters were used. Sixty picomoles of EctR1-His6 shifted about half of the DNA probe (Fig. 4). Incubation of EctR1 with unlabeled specific DNA fragments (at a 10-fold molar ratio) abolished the retardation of labeled DNA. These results suggested a specific interaction between EctR1 and the promoter regions of the ectABC-ask and ectR1 genes.

FIG. 4.

Binding of recombinant EctR1 to the promoter regions of the ectR1 gene and ect operon. EMSAs of the labeled DNA fragment (1 pmol) from nucleotide +231 to +18 relative to the translational start codon of ectA were performed with purified EctR1-His6 in the presence of 0.5 μg sheared herring sperm DNA. The leftmost lane represents the labeled DNA probe alone. Increasing amounts of EctR1-His6 (20, 40, 60, 80, and 160 pmol) were added to the probe. For the competition assay, an unlabeled specific DNA was added to the reaction mixture after incubation with the labeled fragment. Unlabeled DNA was added at 1-, 5-, and 10-molar-ratio excesses (three rightmost lanes) to a lane containing 80 pmol of the purified EctR1-His6 protein.

EctR1 specifically binds as a dimer to the ectAp1 promoter.

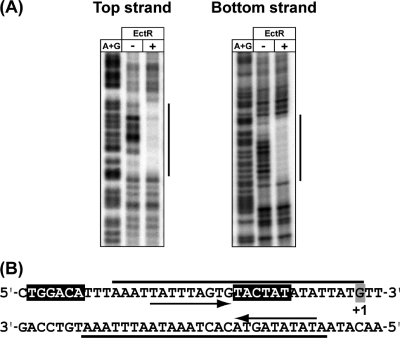

In order to locate the EctR1 binding site, DNase I footprinting assays were performed. As shown in Fig. 5, EctR1 protected an area (31 bp) covering positions from bp −30 to bp +1 relative to the transcription start site from ectAp1. Hence, the protected region included the putative −10 motif of this promoter. Sequence analysis of the EctR1-protected region evidenced the imperfect inverted repeat (TATTTAGT-GT-ACTATATA) with 2 bp separating each half of the pseudopalindrome.

FIG. 5.

EctR1-His6 binding site at the ectAp1 promoter region of the ectABC-ask operon. (A) The DNA probes, labeled at the 5′ end of either the top strand or the bottom strand, were incubated with purified EctR1-His6 and treated with DNase I. The samples were run on a 6% polyacrylamide sequencing gel with a Maxam-Gilbert (A+G) sequencing reaction. (B) Nucleotide sequences of the ectAp1 promoter region of the ectABC-ask operon. Regions protected by EctR1, as determined by the DNase I protection assay, are indicated by lines. Arrows represent the inverted-repeat sequences found in the EctR1 binding site. The transcription start site from the ectAp1 promoter is shaded. Putative −10 and −35 sequences for the promoter are shown on a black background.

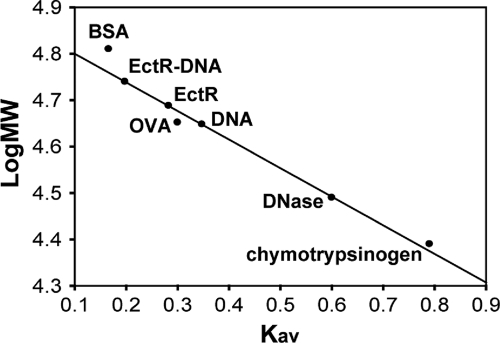

The oligomerization state of the EctR1 protein was analyzed by gel filtration. EctR1 was eluted as a 40-kDa protein, suggesting that it is most likely present as a homodimer in free solution (Fig. 6). A complex of EctR1 plus DNA was also eluted at the position corresponding to a homodimer, indicating that EctR1 binds to DNA as a dimer and that DNA binding does not induce changes in the oligomerization of the protein. This oligomerization state is consistent with the crystallographic and biochemical data for other MarR homologs that have been demonstrated to form homodimers (1, 4, 22, 46).

FIG. 6.

Gel filtration analysis of the EctR1-His6 and EctR1-His6-DNA complexes. Gel filtration chromatography was performed on an Ultrogel AcA 44 column equilibrated with 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0) containing 200 mM KCl and 10 mM MgCl2 at a flow rate of 0.2 ml/min. The apparent molecular masses were estimated using the log of the molecular masses of the standard proteins versus the coefficient Kav, calculated as (Ve − V0)/(Vt − V0), where V0 and Ve are the void and elution volumes, respectively, and Vt is the total column volume. Standard proteins: RNase A (13.7 kDa), chymotrypsinogen A (25 kDa), DNase (31 kDa), ovalbumin (OVA) (45 kDa), and BSA (66 kDa).

Overall, the data presented indicate that EctR1 binds at the ectAp1 promoter region and thereby may repress the transcription of the ectABC-ask operon.

DISCUSSION

We previously reported that in the halotolerant obligate methanotroph M. alcaliphilum 20Z, genes encoding enzymes for biosynthesis of the compatible solute ectoine are organized into the ectABC-ask operon (32). The ectABC-ask operon is transcribed from two σ70-like promoters. Similar σ70 promoters drive the expression of ectoine gene clusters in a variety of halophilic species, such as Chromohalobacter salexigens, Bacillus pasteurii, and Marinococcus halophilus (6, 21, 24), and thus, such an organization of transcriptional machinery is not unique for the methanotrophic bacterium.

A gene (designated ectR1) encoding a transcriptional regulator belonging to the MarR family was identified upstream of the ectABC-ask operon in M. alcaliphilum 20Z. We showed that deletion of the ectR1 gene results in derepression of the ectoine biosynthesis genes at different salt concentrations in the growth medium, thus indicating that EctR1 acts as a negative regulator of the ectABC-ask operon. This finding was further supported by the DNase I footprinting assay data. We found that the EctR1 binding site overlaps with the putative −10 element of the ectAp1 region of the ect operon, resulting in complete blocking of the promoter and thus suggesting steric inhibition of RNA polymerase recruitment. However, very low DNA binding activity (160 pmol of protein per 1 pmol of DNA) of the recombinant EctR1 preparation was detected. We suppose that an unknown mechanism (modification or metabolic signal interactions) may regulate the DNA binding ability of EctR1 depending on the medium osmolarity, but the respective systems for posttranslational modification that are present in M. alcaliphilum 20Z may be absent in E. coli.

The salt-dependent activation of expression of the ect operon observed for the ectR1-impaired strain also indicated that M. alcaliphilum 20Z may possess a complex regulatory system that involves multiple layers of responses. At present, we may only speculate that regulation of the ect genes involves a dynamic balance between repression by the EctR1 regulator and, most likely, activation mediated by a specific, yet unknown component(s). Characterization of the additional regulatory components of the transcriptional control system of the ectABC-ask operon is currently under way.

The MarR family includes a diverse group of regulators that can be classified into three general categories in accordance with their physiological functions: (i) regulation of response to environmental stress, (ii) regulation of virulence factors, and (iii) regulation of aromatic catabolic pathways (48). To our knowledge, EctR1 is the first example of a MarR-like regulator that controls osmoresponse genes. Like other members of the MarR family, EctR1 is located in an orientation opposite that of the controlled gene cluster, has a conservative winged helix-turn-helix motif, and binds to DNA as a homodimer. The EctR1 binding site contains two imperfect inverted repeats with 2 bp separating the two halves of the pseudopalindrome. The centers of the palindrome half-sites are separated by 10 bp, thus indicating that the positioning of each subunit of the EctR1 homodimer occurs on the same face of the DNA helix. This mode of EctR1-DNA binding is similar to that for other members of the MarR family proteins, such as HucR and MexR (12, 47), but different from that for E. coli MarR, which binds to DNA on different faces of the double helix (25).

The levels of both ectABC-ask and ectR1 transcription correlate with the salinity of the growth medium. Since the EctR1 binding site is located between the ectR1 transcription and translation start sites, EctR1 may repress its own expression via inhibition of the elongation process. Autoregulation has been observed for many transcriptional regulators, such as MarR (25), CinR (9), EmrR (10, 23), and HucR (47). In particular, HucR represses the transcription of its own gene and that of genes involved in the catabolism of uric acid (47). This repression is relieved by the binding of uric acid to the repressor, reducing its DNA binding ability. In the case of M. alcaliphilum 20Z, it was demonstrated that cells grown in a medium without NaCl accumulate small concentrations of ectoine (20); thus, ectoine is always present in the cytoplasm and most likely does not alter the DNA binding ability of EctR1. Moreover, the addition of exogenous ectoine or glycine betaine to the growth medium did not affect the induction of enzymes involved in the ectoine biosynthesis pathway.

EctR1 orthologs are present in other halophilic bacteria. In the ectoine- and 5-hydroxyectoine-producing species Salibacillus salexigens, in the DNA segment following the ectD (ectoine hydroxylase) gene, a partial reading frame whose deduced product showed similarity to MarR-type regulators was found (5). However, this reading frame, which is cotranscribed with ectD, was disrupted by two stop codons. Our analysis of the DNA fragment containing the ectoine biosynthetic genes (NCBI accession no. EU315063) in the methanol-utilizing bacterium Methylophaga alcalica showed the presence of an open reading frame with high homology to the ectR1 gene of M. alcaliphilum 20Z (73% identity of translated amino acids). Moreover, a simple NCBI BLAST search revealed several ectR1-like genes located immediately upstream of the ectoine gene cluster in 17 halophilic bacterial species. Between them, the open reading frames of an Oceanospirillum sp. (EAR60187), Nitrosococcus oceani (ABA57535), Saccharophagus degradans (ABD80450), a Reinekea sp. (ZP_01114878), and an Oceanobacter sp. (EAT11341) showed the highest identities of translated amino acid sequences with M. alcaliphilum EctR1 (35.5, 42.2, 45.6, 51.7, and 55.1%, respectively). These results indicate the presence of an EctR-mediated regulatory system controlling ectoine biosynthesis at the transcriptional level in diverse halophilic/halotolerant bacteria.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Tanya Ivashina and Marina Zakharova (G.K. Skryabin Institute of Biochemistry and Physiology of Microorganisms, RAS, Pushchino, Moscow Region, Russia) for valuable suggestions and helpful discussions; Ekaterina Latypova, Linda M. Sauter, and Elizabeth C. Skovran for insightful revision of the manuscript; and Ján Kormanec (Institute of Molecular Biology, Slovak Academy of Sciences, Bratislava, Slovak Republic) and Steven Lindow (Department of Plant and Microbial Biology, University of California) for providing plasmids.

This study was supported by grants from the Russian Foundation for Basic Research (07-04-01064, 07-04-12053-ofi-a), the Ministry of Education and Science (RF RNP 2.1.1/605, Russian State Contract 02.740.11.0296, CRDF Rub1-2946-PU-09), and the U.S. National Science Foundation (MCB-0842686).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 6 November 2009.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alekshun, M. N., S. B. Levy, T. R. Mealy, B. A. Seaton, and J. F. Head. 2001. The crystal structure of MarR, a regulator of multiple antibiotic resistance, at 2.3 Å resolution. Nat. Struct. Biol. 8:710-714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atlas, R. M., and L. C. Parks. 1997. Handbook of microbiological media, 2nd ed. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL.

- 3.Bestvater, T., P. Louis, and E. A. Galinski. 2008. Heterologous ectoine production in Escherichia coli: by-passing the metabolic bottle-neck. Saline Systems 4:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brooun, A., J. J. Tomashek, and K. Lewis. 1999. Purification and ligand binding of EmrR, a regulator of a multidrug transporter. J. Bacteriol. 181:5131-5133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bursy, J., A. J. Pierik, N. Pica, and E. Bremer. 2007. Osmotically induced synthesis of the compatible solute hydroxyectoine is mediated by an evolutionarily conserved ectoine hydroxylase. J. Biol. Chem. 282:31147-31155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calderón, M. I., C. Vargas, F. Rojo, F. Iglesias-Guerra, L. N. Csonka, A. Ventosa, and J. J. Nieto. 2004. Complex regulation of the synthesis of the compatible solute ectoine in the halophilic bacterium Chromohalobacter salexigens DSM 3043T. Microbiology 150:3051-3063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cánovas, D., C. Vargas, M. I. Calderon, A. Ventosa, and J. J. Nieto. 1998. Characterization of the genes for the biosynthesis of the compatible solute ectoine in the moderately halophilic bacterium Halomonas elongata DSM 3043. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 21:487-497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ciulla, R. A., M. R. Diaz, B. F. Taylor, and M. F. Roberts. 1997. Organic osmolytes in aerobic bacteria from Mono Lake, an alkaline, moderately hypersaline environment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:220-226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dalrymple, B. P., and Y. Swadling. 1997. Expression of a Butyrivibrio fibrisolvens E14 gene (cinB) encoding an enzyme with cinnamoyl ester hydrolase activity is negatively regulated by the product of an adjacent gene (cinR). Microbiology 143:1203-1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.del Castillo, I., J. M. Gomez, and F. Moreno. 1990. mprA, an Escherichia coli gene that reduces growth-phase dependent synthesis of microcins B17 and C7 and blocks osmoinduction of proU when cloned on a high-copy-number plasmid. J. Bacteriol. 172:437-445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ditta, G., T. Schmidhauser, F. Yakobson, P. Lu, X. Liang, D. Finlay, D. Guiney, and D. Helinski. 1985. Plasmids related to the broad host range vector, pRK290, useful for gene cloning and monitoring gene expression. Plasmid 13:149-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Evans, K., L. Adewoye, and K. Poole. 2001. MexR repressor of the mexAB-oprM multidrug efflux operon of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: identification of MexR binding sites in the mexA-mexR intergenic region. J. Bacteriol. 183:807-812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fuangthong, M., and J. D. Helmann. 2002. The OhrR repressor senses organic hydroperoxides by reversible formation of a cysteine-sulfenic acid derivative. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99:6690-6695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Galinski, E. A. 1995. Osmoadaptation in bacteria. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 37:272-328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Galinski, E. A., and H. G. Trüper. 1994. Microbial behavior in salt-stressed ecosystems. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 15:95-108. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hawley, D. K., and W. R. McClure. 1983. Compilation and analysis of Escherichia coli promoter DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 11:2237-2254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kalyuzhnaya, M. G., V. N. Khmelenina, S. Kotelnikova, L. Holmquist, K. Pedersen, and Y. A. Trotsenko. 1999. Methylomonas scandinavica sp. nov., a new methanotrophic psychrotrophic bacterium isolated from deep igneous rock ground water of Sweden. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 22:565-572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kempf, B., and E. Bremer. 1998. Uptake and synthesis of compatible solutes as microbial stress responses to high-osmolarity environments. Arch. Microbiol. 170:319-330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khmelenina, V. N., M. G. Kalyuzhnaya, N. G. Starostina, N. E. Suzina, and Y. A. Trotsenko. 1997. Isolation and characterization of halotolerant alkaliphilic methanotrophic bacteria from Tuva soda lakes. Curr. Microbiol. 35:257-261. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khmelenina, V. N., M. G. Kalyuzhnaya, V. G. Sakharovsky, N. E. Suzina, Y. A. Trotsenko, and G. Gottschalk. 1999. Osmoadaptation in halophilic and alkaliphilic methanotrophs. Arch. Microbiol. 172:321-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuhlmann, A. U., and E. Bremer. 2002. Osmotically regulated synthesis of the compatible solute ectoine in Bacillus pasteurii and related Bacillus spp. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:772-783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lim, D., K. Poole, and N. C. J. Strynadka. 2002. Crystal structure of the mexR repressor of the mexRAB-oprM multidrug efflux operon of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Biol. Chem. 277:29253-29259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lomovskaya, O., K. Lewis, and A. Matin. 1995. EmrR is a negative regulator of the Escherichia coli multidrug resistance pump EmrAB. J. Bacteriol. 177:2328-2334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Louis, P., and E. A. Galinski. 1997. Characterization of genes for the biosynthesis of the compatible solute ectoine from Marinococcus halophilus and osmoregulated expression in Escherichia coli. Microbiology 143:1141-1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martin, R. G., and J. L. Rosner. 1995. Binding of purified multiple antibiotic resistance repressor protein (MarR) to mar operator sequences. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 92:5456-5460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marx, C. J., and M. E. Lidstrom. 2002. Broad-host-range cre-lox system for antibiotic marker recycling in gram-negative bacteria. Biotechniques 33:1062-1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miller, W. G., and S. E. Lindow. 1997. An improved GFP cloning cassette designed for prokaryotic transcriptional fusions. Gene 191:149-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mustakhimov, I. I., O. N. Rozova, A. S. Reshetnikov, V. N. Khmelenina, J. C. Murrell, and Y. A. Trotsenko. 2008. Characterization of the recombinant diaminobutyric acid acetyltransferase from Methylophaga thalassica and Methylophaga alcalica. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 283:91-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ono, H., K. Sawada, N. Khunajakr, T. Toa, M. Yamamoto, M. Hiramoto, A. Shinmyo, M. Takano, and Y. Murooka. 1999. Characterization of biosynthetic enzymes for ectoine as a compatible solute in a moderately halophilic eubacterium, Halomonas elongata. J. Bacteriol. 181:91-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peters, P., E. A. Galinski, and H. G. Trüper. 1990. The biosynthesis of ectoine. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 71:157-162. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Poole, K., K. Tetro, Q. Zhao, S. Neshat, D. E. Heinrichs, and N. Bianco. 1996. Expression of the multidrug resistance operon mexA-mexB-oprM in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: mexR encodes a regulator of operon expression. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:2021-2028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reshetnikov, A. S., V. N. Khmelenina, and Y. A. Trotsenko. 2006. Characterization of the ectoine biosynthesis genes of haloalkalotolerant obligate methanotroph “Methylomicrobium alcaliphilum 20Z.” Arch. Microbiol. 184:286-297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reverchon, S., W. Nasser, and J. Robert-Baudouy. 1994. pecS: a locus controlling pectinase, cellulase and blue pigment production in Erwinia chrysanthemi. Mol. Microbiol. 11:1127-1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roberts, M. F. 4 August 2005. Organic compatible solutes of halotolerant and halophilic microorganisms. Saline Systems 1:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ross, W., K. K. Gosink, J. Salomon, K. Igarashi, C. Zou, A. Ishihama, K. Severinov, and R. L. Gourse. 1993. A third recognition element in bacterial promoters: DNA binding by the α-subunit of RNA polymerase. Science 262:1407-1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sambrook, J., and D. W. Russell. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 37.Schacterle, G. R., and R. L. Pollack. 1973. A simplified method for the quantitative assay of small amounts of protein in biologic material. Anal. Biochem. 51:654-655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schäfer, A., A. Tauch, W. Jäger, J. Kalinowski, C. Thierbach, and A. Pühler. 1994. Small mobilizable multi-purpose cloning vectors derived from the Escherichia coli plasmids pK18 and pK19: selection of defined deletions in the chromosome of Corynebacterium glutamicum. Gene 145:69-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Simon, R., U. Priefer, and A. Pühler. 1983. A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in Gram-negative bacteria. Biotechnology 1:784-791. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Srikumar, R., C. J. Paul, and K. Poole. 2000. Influence of mutations in the mexR repressor gene on expression of the MexA-MexB-OprM multidrug efflux system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 182:1410-1414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stapleton, M. R., V. A. Norte, R. C. Read, and J. Green. 2002. Interaction of the Salmonella typhimurium transcription and virulence factor SlyA with target DNA and identification of members of the SlyA regulon. J. Biol. Chem. 277:17630-17637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Strovas, T. J., and M. E. Lidstrom. 2009. Population heterogeneity in Methylobacterium extorquens AM1. Microbiology 155:2040-2048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sukchawalit, R., S. Loprasert, S. Atichartpongkul, and S. Mongkolsuk. 2001. Complex regulation of the organic hydroperoxide resistance gene (ohr) from Xanthomonas involves OhrR, a novel organic peroxide-inducible negative regulator, and posttranscriptional modifications. J. Bacteriol. 183:4405-4412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sulavik, M. C., L. F. Gambino, and P. F. Miller. 1995. The MarR repressor of the multiple antibiotic resistance (mar) operon in Escherichia coli: prototypic member of a family of bacterial regulatory proteins involved in sensing phenolic compounds. Mol. Med. 1:436-446. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thompson, J. D., T. J. Gibson, F. Plewniak, F. Jeanmaugin, and D. G. Higgins. 1997. The Clustal X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:4876-4882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tropel, D., and J. R. van der Meer. 2004. Bacterial transcriptional regulators for degradation pathways of aromatic compounds. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 68:474-500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wilkinson, S. P., and A. Grove. 2004. HucR, a novel uric acid-responsive member of the MarR family of transcriptional regulators from Deinococcus radiodurans. J. Biol. Chem. 279:51442-51450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wilkinson, S. P., and A. Grove. 2006. Ligand-responsive transcriptional regulation by members of the MarR family of winged helix proteins. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 8:51-62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhao, B., W. Lu, L. Yang, B. Zhang, L. Wang, and S. S. Yang. 2006. Cloning and characterization of the genes for biosynthesis of the compatible solute ectoine in the moderately halophilic bacterium Halobacillus dabanensis D-8T. Curr. Microbiol. 53:183-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.