Abstract

The incidence of heat illness and heat stroke is greater in older than younger people. In this context, exercise training regimens to increase heat tolerance in older people may provide protection against heat illness. Acute increases in plasma volume (PV) improve thermoregulation during exercise in young subjects, but there is some evidence that changes in PV in response to acute exercise are blunted in older humans. We recently demonstrated that protein–carbohydrate (Pro-CHO) supplementation immediately after a bout of exercise increased PV and plasma albumin content (Albcont) after 23 h in both young and older subjects. We also examined whether Pro-CHO supplementation during aerobic training enhanced thermoregulation by increasing PV and Albcont in older subjects. Older men aged ∼68 years exercised at moderate intensity, 60 min day−1, 3 days week−1, for 8 weeks, at ∼19°C, and took either placebo (CNT; 0.5 kcal, 0 g protein kg−1) or Pro-CHO supplement (Pro-CHO; 3.2 kcal, 0.18 g protein kg−1) immediately after exercise. After training, we found during exercise at 30°C that increases in oesophageal temperature (Tes) were attenuated more in Pro-CHO than CNT and associated with enhanced cutaneous vasodilatation and sweating. We also confirmed similar results in young subjects after 5 days of training. These results demonstrate that post-exercise protein and CHO consumption enhance thermoregulatory adaptations especially in older subjects and provide insight into potential strategies to improve cardiovascular and thermoregulatory adaptations to exercise in both older and younger subjects.

Introduction

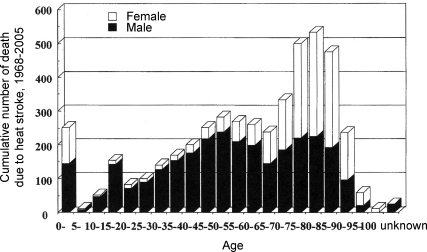

The incidences of heat illness and heat stroke during mid-summer have rapidly increased these two decades as ambient temperatures (Ta) increased globally (Nakai et al. 2007). This tendency was more prominent in the elderly than young adults (Klinenberg, 2003; Nakai et al. 2007) who are less tolerant to heat stress (Kenney, 1997). Nakai et al. (2007) suggested that 1935 older people, aged 70–90 years, died from heat stroke between 1968 and 2005 in Japan, 82% higher than 1065 in younger people, 45–65 years, based on the databases accumulated from the reports by the news papers during the period (Fig. 1). To prevent this, aerobic training is recommended to increase thermoregulatory capacity in both older people (Thomas et al. 1999; Kenney & Munce, 2003) and young adults (Roberts et al. 1977; Ichinose et al. 2005). However, the beneficial effects of training on thermoregulation are generally attenuated in older adults compared with those in young subjects (Ho et al. 1997; Okazaki et al. 2002) although the precise mechanisms remain unknown.

Figure 1. The cumulative number of deaths due to heatstroke from 1968 to 2005 in Japan.

Total number of deaths was 5433 and each column indicates the number in each age bin of 5 years. (Modified from Nakai et al. 2007; used with permission.)

Indeed, we confirmed that cutaneous blood flow and sweat rate responses to exercise remained unchanged on average after 18 weeks of aerobic training in older subjects (Okazaki et al. 2002). However, in this study, we found that the responses were enhanced in a subset of older subjects with increased plasma volume (PV) while reduced in subjects with a blunted PV response to training, suggesting that the attenuated improvement of thermoregulation after aerobic training in older people was due to attenuated PV expansion.

Several studies on the effects of acute PV expansion on thermoregulation in young subjects have suggested that an acute increase in cardiac filling pressure by saline infusion (Nose et al. 1990), head out water immersion (Nielsen et al. 1984), or continuous negative pressure breathing (Nagashima et al. 1998) enhanced cutaneous vasodilatation due to an increased cardiac stroke volume (SV) during exercise in a warm environment. These results suggest that stretching of cardiac wall by PV expansion enhances the sensitivity of thermoregulation via baroreflex mechanisms that facilitate high levels of skin blood flow. On the other hand, there have been few studies, regardless of subject age, demonstrating that PV expansion after aerobic training significantly contributes to the enhanced thermoregulatory sensitivity since central nervous system adaptations to heat stress also occur (Nadel et al. 1974) making it difficult to distinguish the effects of PV expansion from central mechanisms.

In this paper, we briefly review our data showing that post-exercise protein and carbohydrate (CHO) supplementation during aerobic training enhanced PV expansion and accelerated cardiovascular and thermoregulatory adaptation in older subjects as well as in young subjects. This approach may be useful to increase heat tolerance especially in older people with lower thermoregulatory capacity, and our data reinforce the idea that post-exercise nutrition is critical especially for older humans.

Post-exercise protein and CHO supplementation enhances PV expansion

The exercise-induced PV expansion in young subjects has been suggested to be oncotically mediated and so to rely on a rapid increase in plasma albumin content (Albcont), resulting in drawing fluids into the vascular space so that plasma albumin concentration remains constant (Convertino et al. 1980; Gillen et al. 1991). On the other hand, several previous studies suggested that an increase in Albcont after aerobic training was diminished in older subjects with an attenuated increase in PV (Zappe et al. 1996; Okazaki et al. 2002). Since one of the mechanisms of increased Albcont after aerobic training is likely to be enhanced response of hepatic albumin synthesis to exercise in young subjects (Yang et al. 1998; Nagashima et al. 2000), the lower increase in Albcont after training in older subjects could be caused in part by their blunted response of albumin synthesis to exercise (Gersovitz et al. 1980; Sheffield-Moore et al. 2004) due to a reduced gene expression rate with ageing (Horbach et al. 1984). However, it is also plausible that this is caused by protein intake insufficient for albumin synthesis in older people since they are likely to be habituated to low caloric and protein diets due to minimal daily physical activity (Ministry of Health, 1999). These mechanisms may lead to a reduction in substrate availability for protein synthesis after strenuous exercise in older subjects.

Therefore, we examined if increased PV and Albcont for 23 h after exercise was attenuated in older subjects compared with those in young adult subjects, and if the attenuation was abated by supplementation of protein and CHO immediately after exercise (Okazaki et al. 2009a). To do this, moderately active older aged ∼68 years and young men aged ∼21 years performed two trials: placebo (CNT; 0.5 kcal, 0 g protein per kg body weight) or protein and CHO mixture (Pro-CHO; 3.2 kcal, 0.18 g protein per kg body weight) supplementations immediately after a high-intensity interval exercise for 72 min; 8 sets of 4 min at 70–80% peak oxygen consumption rate  followed by 5 min at 20%

followed by 5 min at 20% . PV and Albcont were measured before exercise, at the end of exercise, every hour from the first 5 hours and at the 23rd hour after exercise. The recoveries of PV and Albcont were generally attenuated in older than young subjects in the CNT trial. However, in the Pro-CHO trial, Albcont recovered more than in the CNT trial in older subjects, and was similar to the recovery in young subjects, and accompanied by a greater increase in PV.

. PV and Albcont were measured before exercise, at the end of exercise, every hour from the first 5 hours and at the 23rd hour after exercise. The recoveries of PV and Albcont were generally attenuated in older than young subjects in the CNT trial. However, in the Pro-CHO trial, Albcont recovered more than in the CNT trial in older subjects, and was similar to the recovery in young subjects, and accompanied by a greater increase in PV.

As for the mechanisms, our data suggest that Pro-CHO supplementation enhanced the post-exercise plasma albumin synthetic rate (Yang et al. 1998; Nagashima et al. 2000; Sheffield-Moore et al. 2004) to increase Albcont, which in turn enhanced the effective colloid osmotic pressure gradient between intra- and extravascular spaces and thereby induced PV expansion (Convertino et al. 1980; Gillen et al. 1991).

The effects of PV expansion by protein and CHO supplementation on cardiovascular and thermoregulatory capacities after training

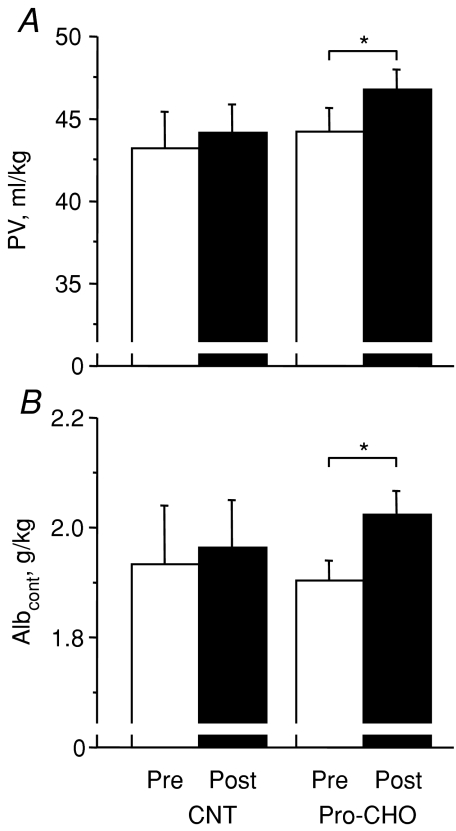

Next, we examined the effects of the protein and CHO supplementation during aerobic training on PV and cardiovascular and thermoregulatory responses to exercise in older subjects (Okazaki et al. 2009b). Healthy older men aged ∼68 years were divided into two groups: placebo (CNT; 0.5 kcal and 0 g protein kg−1) and protein and CHO mixture (Pro-CHO; 3.2 kcal and 0.18 g protein kg−1) supplementations. Subjects in both groups performed an exercise training for 8 weeks; cycling exercise, 60–75% , 60 min day−1, 3 days week−1 at Ta of ∼19°C and ∼43% relative humidity (RH) and took the respective supplement immediately after each day of exercise. After training, as shown in Fig. 2, PV and Albcont remained unchanged in the CNT group, confirming previous results from us after 18 weeks of aerobic training in older men (Okazaki et al. 2002) and others (Zappe et al. 1996; Stachenfeld et al. 1998; Takamata et al. 1999). On the other hand, in the Pro-CHO group, both PV and Albcont increased significantly by 6%.

, 60 min day−1, 3 days week−1 at Ta of ∼19°C and ∼43% relative humidity (RH) and took the respective supplement immediately after each day of exercise. After training, as shown in Fig. 2, PV and Albcont remained unchanged in the CNT group, confirming previous results from us after 18 weeks of aerobic training in older men (Okazaki et al. 2002) and others (Zappe et al. 1996; Stachenfeld et al. 1998; Takamata et al. 1999). On the other hand, in the Pro-CHO group, both PV and Albcont increased significantly by 6%.

Figure 2. Plasma volume (PV) (A) and albumin content (Albcont) (B) before (Pre) and after (Post) 8 weeks of aerobic training in older men.

CNT, placebo intake group; Pro-CHO, protein and carbohydrate supplement intake group. Means and s.e.m. bars are presented for 7 subjects. *P < 0.05. (Modified from Okazaki et al. 2009b; used with permission from the American Physiological Society.)

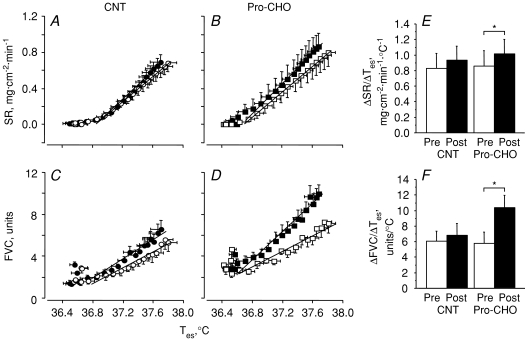

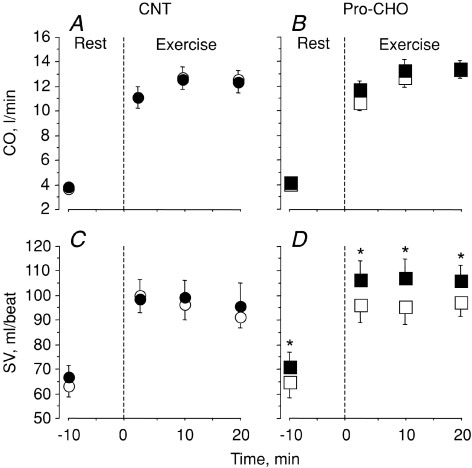

Regarding thermoregulatory response to exercise, as shown in Fig. 3, after training, the sensitivity of chest sweat rate (ΔSR/ΔTes) and forearm skin vascular conductance (ΔFVC/ΔTes) in response to increased oesophageal temperature (Tes) during exercise at 60% pre-training  , at 30°C of Ta and 50% of RH remained unchanged in the CNT group, confirming the results in our previous study (Okazaki et al. 2002). On the other hand, in the Pro-CHO group, the responses were significantly enhanced by 18% and 80%, respectively. Moreover, as shown in Fig. 4, after training, SV during exercise remained unchanged in the CNT group while it increased significantly by ∼10% in the Pro-CHO group. Furthermore, although an increase in heart rate (HR) during prolonged exercise in the heat was reduced in both groups, the reduction was more in the Pro-CHO group than in the CNT group. In addition, thermal strain calculated as the increase in Tes from before to 20 min exercise was significantly attenuated in the Pro-CHO group but did not change in the CNT group. Thus, in older men, although cardiovascular and thermoregulatory adaptation after aerobic training is generally attenuated compared to young subjects, post-exercise protein and CHO supplementation during aerobic training appears to normalize these responses by increasing PV.

, at 30°C of Ta and 50% of RH remained unchanged in the CNT group, confirming the results in our previous study (Okazaki et al. 2002). On the other hand, in the Pro-CHO group, the responses were significantly enhanced by 18% and 80%, respectively. Moreover, as shown in Fig. 4, after training, SV during exercise remained unchanged in the CNT group while it increased significantly by ∼10% in the Pro-CHO group. Furthermore, although an increase in heart rate (HR) during prolonged exercise in the heat was reduced in both groups, the reduction was more in the Pro-CHO group than in the CNT group. In addition, thermal strain calculated as the increase in Tes from before to 20 min exercise was significantly attenuated in the Pro-CHO group but did not change in the CNT group. Thus, in older men, although cardiovascular and thermoregulatory adaptation after aerobic training is generally attenuated compared to young subjects, post-exercise protein and CHO supplementation during aerobic training appears to normalize these responses by increasing PV.

Figure 3. Thermoregulatory responses to exercise before and after 8 weeks of aerobic training in older men.

A–D, chest sweat rate (SR) (A and B) and forearm skin vascular conductance (FVC) (C and D) responses to increased oesophageal temperature (Tes) during exercise in a warm environment (30°C ambient temperature, 50% relative humidity) before (open symbols) and after (filled symbols) training. E and F represent sensitivity of an increase in SR (ΔSR/ΔTes) and FVC (ΔFVC/ΔTes) at a given increase in Tes determined for each subject before (Pre) and after (Post) training. Exercise intensity was 60% of pre-training peak oxygen consumption rate. CNT, placebo intake group; Pro-CHO, protein and carbohydrate supplement intake group. Means and s.e.m. bars are presented for 7 subjects. *P < 0.05. (From Okazaki et al. 2009b; used with permission from the American Physiological Society.)

Figure 4. Cardiac output (CO) (A and B) and stroke volume (SV) (C and D) during rest and exercise in a worm environment (30°C ambient temperature, 50% relative humidity) before (open symbols) and after (filled symbols) 8 weeks of aerobic training in older men.

Exercise intensity was 60% of pre-training peak oxygen consumption rate. CNT, placebo intake group; Pro-CHO, protein and carbohydrate supplement intake group. Means and s.e.m. bars are presented for 7 subjects. *P < 0.05 compared with before training. (From Okazaki et al. 2009b; used with permission from the American Physiological Society.)

We recently examined whether this would occur also in young men using a similar experimental protocol as in older subjects although the aerobic training period was 5 days (Goto et al. 2007). Young men aged ∼23 years were divided into two groups: placebo (CNT; 0.9 kcal and 0 g protein kg−1), and protein and CHO mixture (Pro-CHO; 3.6 kcal and 0.36 g protein kg−1) supplementations. Subjects in both groups performed 5 consecutive days of exercise training (cycling exercise, ∼70% , 30 min day−1, at 30°C of Ta and 50% of RH) and took the respective supplement immediately after each day of exercise. After training, we found that PV and Albcont in the Pro-CHO group increased by ∼8% and ∼10%, respectively, which were significantly higher than ∼4% in the CNT group. During exercise, we found that the increases in HR and Tes during exercise were attenuated after training in both groups but significantly more in the Pro-CHO group than in the CNT group. Moreover, ΔSR/ΔTes and ΔFVC/ΔTes in the Pro-CHO group increased by 44% and 56%, respectively, after training, much higher than the 10% and 19% in the CNT group. In addition, after training, SV increased in both groups but more prominently in the Pro-CHO group than in the CNT group. Thus, thermoregulatory and aerobic adaptations to aerobic training were also enhanced by Pro-CHO supplementation in younger subjects, similarly to in older subjects.

, 30 min day−1, at 30°C of Ta and 50% of RH) and took the respective supplement immediately after each day of exercise. After training, we found that PV and Albcont in the Pro-CHO group increased by ∼8% and ∼10%, respectively, which were significantly higher than ∼4% in the CNT group. During exercise, we found that the increases in HR and Tes during exercise were attenuated after training in both groups but significantly more in the Pro-CHO group than in the CNT group. Moreover, ΔSR/ΔTes and ΔFVC/ΔTes in the Pro-CHO group increased by 44% and 56%, respectively, after training, much higher than the 10% and 19% in the CNT group. In addition, after training, SV increased in both groups but more prominently in the Pro-CHO group than in the CNT group. Thus, thermoregulatory and aerobic adaptations to aerobic training were also enhanced by Pro-CHO supplementation in younger subjects, similarly to in older subjects.

Regarding the mechanisms for improved cardiovascular and thermoregulatory responses by the protein and CHO supplementation in both age groups, the increased PV after training with the supplementation would enhance venous return to the heart to increase cardiac filling pressure. This would further enhance SV and thermoregulatory responses by stretching the cardiopulmonary mechanoreceptors as suggested in young subjects with an acute increase in PV (Nielsen et al. 1984; Nose et al. 1990; Nagashima et al. 1998), and thereby reduce cardiovascular and thermal strain during exercise by permitting greater increases in skin blood flow. Thus, our results clearly demonstrate that cardiovascular and thermoregulatory capacities increase with PV expansion after training in addition to neural adaptations seen in the thermoregulatory centre in the hypothalamus to repeated heat exposure during training (Nadel et al. 1974).

In conclusion, aerobic training with post-exercise protein and CHO supplementation increases PV and therefore cardiovascular and thermoregulatory capacities in both elderly and young. These results provide new insight into a regimen of training and dietary manipulations to improve cardiovascular and thermoregulatory capacity more than exercise alone and prevent heat disorders in older people. They also highlight the benefits of optimizing post-exercise nutrition in both younger and older subjects.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by grants from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan, the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare of Japan (Comprehensive Research on Ageing and Health), and from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

References

- Convertino VA, Brock PJ, Keil LC, Bernauer EM, Greenleaf JE. Exercise training-induced hypervolemia: role of plasma albumin, rennin, and vasopressin. J Appl Physiol. 1980;48:665–669. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1980.48.4.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gersovitz M, Munro HN, Udall J, Young VR. Albumin synthesis in young and elderly subjects using a new stable isotope methodology: response to level of protein intake. Metabolism. 1980;29:1075–1086. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(80)90219-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillen CM, Lee R, Mack GW, Tomaselli CM, Nishiyasu T, Nadel ER. Plasma volume expansion in humans after a single intense exercise protocol. J Appl Physiol. 1991;71:1914–1920. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1991.71.5.1914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goto M, Kamijo Y, Okazaki K, Masuki S, Miyagawa K, Nose H. Protein and carbohydrate supplementation during 5-day aerobic training enhanced improvement of thermoregulation in young men. FASEB J. 2007;21:A1296. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00577.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho CW, Beard JL, Farrell PA, Minson CT, Kenney WL. Age, fitness, and regional blood flow during exercise in the heat. J Appl Physiol. 1997;82:1126–1135. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1997.82.4.1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horbach GJ, Princen HM, Van Der Kroef M, Van Bezooijen CF, Yap SH. Changes in the sequence content of albumin mRNA and in its translational activity in the rat liver with age. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1984;783:60–66. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(84)90078-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichinose T, Okazaki K, Masuki S, Mitono H, Chen M, Endoh H, Nose H. Ten-day endurance training attenuates the hyperosmotic suppression of cutaneous vasodilation during exercise but not sweating. J Appl Physiol. 2005;99:237–243. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00813.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenney WL. Thermoregulation at rest and during exercise in healthy older adults. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 1997;25:41–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenney WL, Munce TA. Invited review: aging and human temperature regulation. J Appl Physiol. 2003;95:2598–2603. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00202.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klinenberg E. Review of heat wave: social autopsy of disaster in Chicago. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:666–667. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200302133480721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health Labour, and Welfare, Japan, Study Circle for Health and Nutrition Information. Recommended Dietary Allowances for Japanese, 6th Revision. Dietary Reference Intakes [in Japanese] Tokyo: Daiichi-Shuppan Co. Ltd.; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Nadel ER, Pandolf KB, Roberts MF, Stolwijk JA. Mechanisms of thermal acclimation to exercise and heat. J Appl Physiol. 1974;37:515–520. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1974.37.4.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagashima K, Cline GW, Mack GW, Shulman GI, Nadel ER. Intense exercise stimulates albumin synthesis in the upright posture. J Appl Physiol. 2000;88:41–46. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.88.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagashima K, Nose H, Takamata A, Morimoto T. Effect of continuous negative-pressure breathing on skin blood flow during exercise in a hot environment. J Appl Physiol. 1998;84:1845–1851. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.84.6.1845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakai S, Shin-ya H, Yoshida T, Yorimoto A, Inoue Y, Morimoto T. Proposal of new guidelines for prevention of heat disorders during sports and daily activities based on age, clothing and heat acclimatization. Jpn J Fitness Sports Med. 2007;56:437–444. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen B, Rowell LB, Bonde-Petersen F. Cardiovascular responses to heat stress and blood volume displacements during exercise in man. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. 1984;52:370–374. doi: 10.1007/BF00943365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nose H, Mack GW, Shi XR, Morimoto K, Nadel ER. Effect of saline infusion during exercise on thermal and circulatory regulations. J Appl Physiol. 1990;69:609–616. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1990.69.2.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okazaki K, Hayase H, Ichinose T, Mitono H, Doi T, Nose H. Protein and carbohydrate supplementation after exercise increases plasma volume and albumin content in older and young men. J Appl Physiol. 2009a;107:770–779. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.91264.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okazaki K, Ichinose T, Mitono H, Chen M, Masuki S, Endoh H, Hayase H, Doi T, Nose H. Impact of protein and carbohydrate supplementation on plasma volume expansion and thermoregulatory adaptation by aerobic training in older men. J Appl Physiol. 2009b;107:725–733. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.91265.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okazaki K, Kamijo Y, Takeno Y, Okumoto T, Masuki S, Nose H. Effects of exercise training on thermoregulatory responses and blood volume in older men. J Appl Physiol. 2002;93:1630–1637. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00222.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts MF, Wenger CB, Stolwijk JA, Nadel ER. Skin blood flow and sweating changes following exercise training and heat acclimation. J Appl Physiol. 1977;43:133–137. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1977.43.1.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheffield-Moore M, Yeckel CW, Volpi E, Wolf SE, Morio B, Chinkes DL, Paddon-Jones D, Wolfe RR. Postexercise protein metabolism in older and younger men following moderate-intensity aerobic exercise. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2004;287:E513–E522. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00334.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stachenfeld NS, Mack GW, DiPietro L, Morocco TS, Jozsi AC, Nadel ER. Regulation of blood volume during training in post-menopausal women. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1998;30:92–98. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199801000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takamata A, Ito T, Yaegashi K, Takamiya H, Maegawa Y, Itoh T, Greenleaf JE, Morimoto T. Effect of an exercise-heat acclimation program on body fluid regulatory responses to dehydration in older men. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 1999;277:R1041–R1050. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1999.277.4.R1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas CM, Pierzga JM, Kenney WL. Aerobic training and cutaneous vasodilation in young and older men. J Appl Physiol. 1999;86:1676–1686. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.86.5.1676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang RC, Mack GW, Wolfe RR, Nadel ER. Albumin synthesis after intense intermittent exercise in human subjects. J Appl Physiol. 1998;84:584–592. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.84.2.584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zappe DH, Bell GW, Swartzentruber H, Wideman RF, Kenney WL. Age and regulation of fluid and electrolyte balance during repeated exercise sessions. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 1996;270:R71–R79. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1996.270.1.R71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]