Abstract

Background

Despite poor primary healthcare systems, free antiretroviral therapy (ART) has been available in China for over 5 years. Virologic outcomes of Chinese patients receiving ART have not been described at a national level.

Methods

A multi-stage cluster design was used in 8 provinces to randomly sample patients with at least 6 months on first-line ART, stratified by 3 treatment duration groups. Viral load testing and patient interviews were conducted and linked with national treatment database information. Data collected were analyzed for association with viral suppression using multivariable modeling. Adequate viral suppression was defined as viral load less than 400 copies/mL.

Results

Of 5,256 patients on ART, 3,894 patients met eligibility criteria from whom 1,153 were analyzed. Overall, 72% demonstrated viral suppression; of these, 82%, 73%, and 67% of participants on ART for 6–11 months, 12–23 months, and ≥24 months, respectively, showed viral suppression (p<0.001). In a multivariable model, treatment received at locations other than county level hospitals was less likely to achieve viral suppression, with greater odds for inadequate virologic response found at village clinics (odds ratio [OR] 5.4; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.9–10.1), township health centers (OR, 3.1; CI, 1.7–5.6), and public health clinics (OR, 3.1; CI, 1.7–5.6). Patients receiving didanosine-based regimens were more likely to experience an inadequate virologic response than those receiving lamivudine-based regimens (OR, 3.9; CI, 2.7–5.7).

Conclusions

China’s national ART program is largely successful at suppressing viral load. Care received outside of hospitals and regimens containing didanosine were associated with less favorable virologic outcomes.

Keywords: viral load, antiretroviral therapy, resource-limited setting, HIV, China

Introduction

China has approximately 700,000 people infected with HIV spread thinly among the population of more than 1.3 billion [1]. China has confronted considerable challenges managing its HIV epidemic. Previously the HIV epidemic in China was mostly among injection drug users and poor farmers who donated plasma unsafely to illegal vendors [2–4], sexual transmission is now on the rise [5]. In 2003, the Chinese Government implemented the National Free Antiretroviral Treatment Program to emergently provide care to the rural population most heavily affected. It was decentralized and relied upon local clinicians with limited training [6]. Having matured over the last 5 years from an emergency response into a standardized treatment and care program [3, 6], more than 52,000 patients have received antiretroviral therapy (ART) [7].

To achieve universal access, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends decentralization and task shifting of HIV care to non-physician clinicians in resource-limited settings [8–10]. The feasibility of implementing ART in developing countries has been demonstrated, but previous studies of virologic outcome are limited to short treatment duration periods, small numbers of treatment sites, and few treatment regimens. We report here virologic outcomes of patients on first line therapy as well as factors associated with virologic failure in a sample of adult patients receiving ART in 8 provinces in China.

Methods

Patients and ART Regimens

This study was approved by the institutional review board of the China Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (China CDC). In accordance with Chinese [11] and WHO [12] guidelines, initiation and monitoring of ART was based on clinical and immunologic parameters. National guidelines provide for triple therapy with a first-line regimen of stavudine (d4T) or zidovudine (AZT), lamivudine (3TC), and nevirapine (NVP) or efavirenz (EFV). However, early in the treatment program, the supply of 3TC was limited leading to its frequent substitution with didanosine (ddI). Viral load was not routinely tested and second-line therapy was not yet widely available at the time of this study.

HIV care and treatment is provided at a variety of sites within the Chinese health care system which is graded hierarchically based on the level of administrative division in which it is located. County level hospitals and public health clinics are located within county capitals, township health centers in smaller towns, and village clinics in rural settings. In village clinics, township health centers, and public health clinics, care is provided by clinicians often lacking a medical degree or extensive formal medical education [13]. HIV care providers usually receive a structured two months of didactic and practical HIV care training.

National Database

The National Free ART Database, previously described [6, 14], is an ongoing observational database established in 2004 and maintained by the China CDC that contains baseline and follow-up data from patients enrolled in the National Free Antiretroviral Treatment Program, currently covering over 90% of patients on ART in China. For every visit to an HIV healthcare provider, a form is completed and sent to the China CDC via DataFax (Clinical DataFax Systems Inc., Hamilton, Ontario, Canada) for automated entry into the database [15].

Study Design and Sampling Method

A multi-stage cluster design was used to sample patients who received at least 6 months of ART in China. Of 31 province level administrative units in mainland China, 8 provinces were purposively selected representing 88% of Chinese patients on ART. Of the provinces selected, Henan, Shanxi, Anhui, Hubei, Shandong, and Jilin provinces have relatively large populations of former plasma donors, patients who were infected by unsafe donation of plasma to illegal vendors [4]. These provinces were among the first provinces to start the National Free Antiretroviral Treatment Program [6]. Yunnan and Guangxi have high injection drug user and sexually transmitted HIV patient populations and have experienced a rapid scale-up of treatment [6, 16].

For each province, the national treatment database was queried for counties with at least 50 patients receiving ART. Two of these counties were randomly selected, except for Shandong and Jilin provinces in which 3 and 9 counties were sampled respectively due to the lower number of patients on ART in each county. Patients who were on ART for less than 6 months, aged less than 15, terminated treatment, had died, were lost-to-follow-up, or moved away from their treatment center were excluded. Three treatment duration groups were established: 6–11, 12–23, and ≥24 months. For each county, stratified sampling was used according to the minimum sample size derived from power calculation in order to select a fixed proportion of subjects within each treatment duration group. If a particular county did not have enough patients to fill each of the 3 treatment duration groups, all patients from that county were included.

Data collection

Subjects were enrolled from April to June 2007. After informed consent was obtained, a study-specific patient questionnaire was administered by trained research assistants eliciting demographic, ART care condition, and adherence data. Blood samples were collected and tested for CD4 cell count at county and provincial laboratories. Samples were also sent for viral load testing at 8 provincial laboratories using either the COBAS Amplicor HIV-1 Monitor (Roche Diagnostic Systems, Branchburg, N.J.) or NucliSens EasyQ HIV-1 (BioMerieux, Marcy L’Etoile, France). Data from the National Free ART Database was also used for analysis.

Definitions

Immunologic failure was defined according to WHO guidelines (i.e., CD4 count <100 after 6 months on ART, below baseline, or <50% of peak) [12]. Adequate viral suppression was defined as a viral load of less than 400 copies per mL. Viral load between 400 and 1,000 was defined as indeterminate and 1,001 to 10,000 as probable virologic failure [17]. Definite virologic failure was defined as greater than 10,000 copies per mL according to WHO guidelines [12].

Statistical analysis

An intent-to-treat analysis of treatment regimen was used restricting analysis to initial treatment regimen. Baseline characteristics were compared using the Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables and the Pearson χ2 statistic for dichotomous and categorical variables. Hypothesis testing was 2-sided with α = 0.05. Univariate comparisons were performed on 14 variables. Variables with p<0.2 were retained for multivariable modeling using stepwise selection. Clinical judgment was used to force potential confounders such as age, gender, and treatment duration into final models. Multivariable logistics regression models were run with all patients and stratified separately by treatment duration and by regimen. Results were reported as the multivariate-adjusted odds ratio (AOR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) for the association between predictor variables and failure to reach adequate viral suppression. Sensitivity analyses were conducted with removal of indeterminate viral load results. Data were analyzed using SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Patient Selection and Characteristics

The 24 selected counties had provided ART to 5,256 patients of whom 926 (18%) were excluded because they received ART for less than 6 months, 23 (0.4%) because they were below 15 years of age, and 3 (<0.1%) because they were not receiving ART for free. Of 4,304 patients remaining, 237 (6%) patients were known to have died, 52 (1%) terminated ART, 84 (2%) were lost-to-follow-up, and 37 (1%) moved away.

From the remaining 3,894 eligible patients, 1,170 (30%) were selected using stratified random sampling as described above. Data from 1,153 patients were available for analysis. Baseline demographic characteristics at the time of ART initiation are shown in Table 1. The median age was 39 years (interquartile range [IQR] 34–46) and 56% of patients were male. Reported transmission routes were 59% history of plasma donation, 8% injection drug use, 25% sexual transmission, and 8% other.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients by treatment duration group among a stratified random sample of patients in 8 provinces in China, 2007

| Demographic and clinical characteristics | Treatment duration group, months |

All patients (N=1153) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6–11 | 12–23 | ≥24 | p | ||

| (N=210) | (N=416) | (N=527) | |||

| At treatment initiation | |||||

| Age in years, Median (IQR) | 38.5 (33–45) | 38.5 (33–45.5) | 40 (35–46) | 0.03 | 39 (34–46) |

| Male, N (%) | 124 (59.1) | 246 (59.1) | 274 (52.0) | 0.07 | 644 (55.9) |

| Transmission route, N (%) | |||||

| Former plasma donation | 67 (33.8) | 174 (43.8) | 404 (80.0) | <0.001 | 645 (58.5) |

| Injection drug use | 24 (12.1) | 54 (13.6) | 13 (2.6) | 91 (8.3) | |

| Sex | 85 (42.9) | 138 (34.8) | 56 (11.0) | 279 (25.3) | |

| Primary school education or below, N (%) | 94 (44.8) | 199 (47.8) | 317 (60.2) | <0.001 | 610 (52.9) |

| Married or cohabiting, N (%) | 170 (81.0) | 319 (76.7) | 452 (85.8) | 0.002 | 941 (81.6) |

| Initial regimen, N (%) | |||||

| AZT/d4T+3TC+NVP/EFV | 160 (76.2) | 280 (67.3) | 148 (28.1) | <0.001 | 588 (51.0) |

| AZT/d4T+ddI+NVP/EFV | 49 (23.3) | 108 (26.0) | 373 (70.8) | 530 (46.0) | |

| Baseline CD4 count /ul, median (IQR) | 101 (36–178) | 122.5 (41–200) | 126.5 (43–208) | 0.03 | 119 (40–199) |

| Active opportunistic infection symptoms, N (%) | 107 (51.0) | 258 (62.0) | 382 (72.6) | <0.001 | 747 (64.8) |

| Anemic at baseline, N (%) | 68 (32.9) | 137 (34.3) | 141 (28.3) | 0.13 | 346 (31.3) |

| Have used Chinese medicine, N (%) | 31 (14.8) | 43 (10.3) | 173 (32.8) | <0.001 | 247 (21.4) |

| At time of investigation | |||||

| Type of treatment center, N (%) | |||||

| Village clinic | 23 (11.0) | 77 (18.5) | 163 (30.9) | <0.001 | 263 (22.8) |

| Township health center | 57 (27.1) | 89 (21.4) | 167 (31.7) | 313 (27.1) | |

| Public health clinic | 48 (22.9) | 121 (29.1) | 164 (31.1) | 333 (28.9) | |

| County level hospital or above | 82 (39.0) | 129 (31.0) | 33 (6.3) | 244 (21.2) | |

| Have missed ART dose in last 7 days, N (%) | 13 (6.2) | 42 (10.2) | 43 (8.2) | 0.22 | 98 (8.5) |

| Have switched regimen, N (%) | 18 (8.6) | 67 (16.1) | 208 (39.5) | <0.001 | 293 (25.4) |

| Positive health beliefs of ART, N (%) | 193 (91.9) | 374 (89.9) | 506 (96.0) | <0.001 | 1073 (93.1) |

| Travel time to clinic, N (%) | |||||

| <1 hour | 143 (68.1) | 273 (65.8) | 402 (76.3) | 0.005 | 818 (71.0) |

| ≥1 hour, < half day | 52 (24.8) | 102 (24.6) | 88 (16.7) | 242 (21.0) | |

Note. ART, antiretroviral therapy; IQR, interquartile range; AZT, zidovudine; d4T, stavudine; 3TC, lamivudine; NVP, nevirapine; EFV, efavirenz; ddI, didanosine.

Treatment Conditions and Outcomes

Median time on ART was 22.8 months (IQR 14.2–35.6) with a median duration of 9.1 months in the 6–12 month group, 18.9 months in the 12–24 month group, and 35.9 months in the ≥24 month group. Initial regimens consisted of NVP or EFV, plus AZT or d4T, plus ddI or 3TC, with 3% on other regimens. In total, 51% of patients were started on 3TC-based regimens and 46% on ddI-based regimens with 3TC use increasing in those initiating ART more recently. In the ≥24 month group, ddI was used in 91%, 82%, 51%, and 15% of regimens at village clinics, township health centers, public health clinics, and county-level or above hospitals, respectively (p<0.001). In the 6–11 month strata, ddI use continued in village and township health centers with 61% and 56% patients starting a ddI-based regimen but declined at public health clinics and county-level hospitals to 4% and 1%, respectively.

Median baseline CD4 cell count was 119 (interquartile range [IQR] 40–199) cells per mm3 with data missing for 21% of participants. Treatment locations were divided between 23% village clinics, 27% township health centers, 29% public health clinics, and 21% county level hospitals. Self-reported 100% adherence in the previous week was 92%.

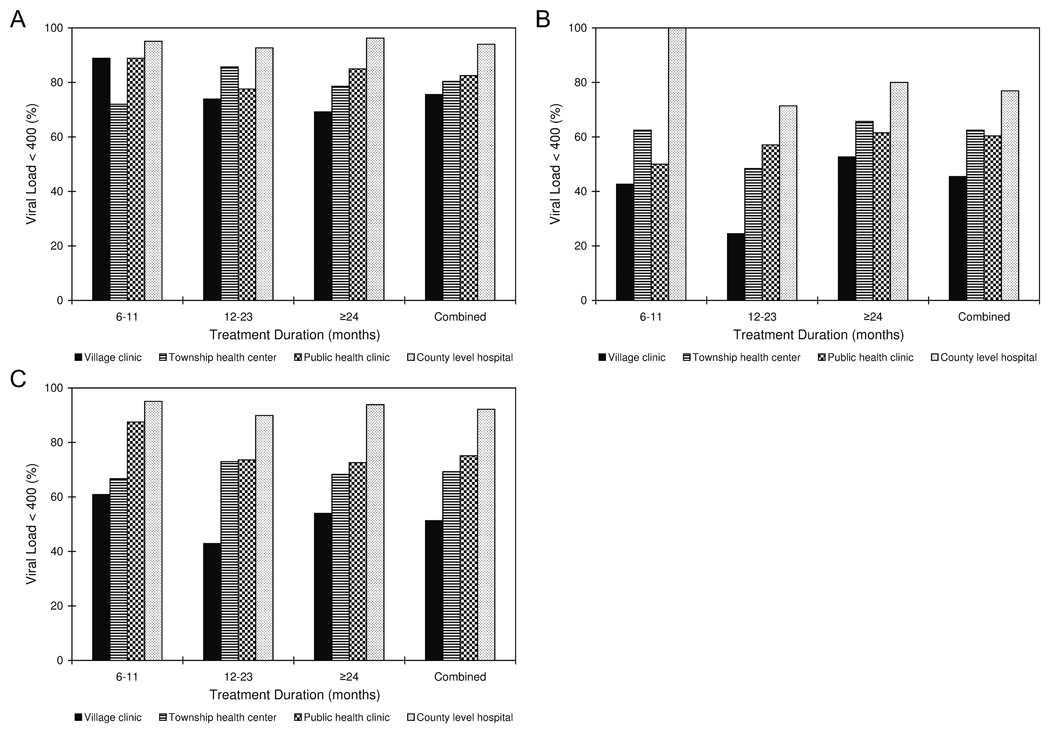

Viral suppression (HIV viral load < 400 copies/mL) stratified by duration on ART was 82%, 73%, and 67% for participants on ART for 6–11 months, 12–23 months, and ≥24 months, respectively. Probable virologic failure (HIV viral load 1,001–10,000 copies/mL) was found in 6%, 8%, and 12% of patients and definite virologic failure (HIV viral load > 10,000 copies/mL) was found in 10%, 14%, and 18% of patients, among the same 3 treatment duration strata. For 4% of patients, viral load was indeterminate (400–1,000 copies/mL). Virologic outcomes by time on first line ART regimen and treatment facility are shown in Figure 1A for patients receiving 3TC-based regimens, Figure 1B for patients receiving ddI-based regimens, and Figure 1C for the whole study population. At the time of viral load testing, 18%, 13%, and 14% of subjects in the 6–11 month, 12–23 month, and ≥24 month groups, respectively, demonstrated immunologic failure. Discordance between immunologic and virologic responses is shown in Table 2. Combined, 66% of patients achieved both a virologic and immunologic response, 6% virologic alone, 20% immunologic alone, and 9% no response.

Figure 1.

Virologic response divided by treatment duration and facility type for patients with initial regimens containing lamivudine (A), for patients with initial regimens containing didanosine (B), and for the whole study population (C) among a stratified random sample of patients in 8 provinces in China, 2007

Table 2.

Discordance of immunologic and virologic responses to ART by treatment duration group among a stratified random sample of patients in 8 provinces in China, 2007

| Treatment Duration Group, months |

Complete viral suppression (VL+/CD4+) N (%) |

Virologic suppresion Only (VL+/CD4−) N (%) |

Immunologic suppresion Only (VL−/CD4+) N (%) |

No suppression (VL−/CD4−) N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6–11 | 151 (72) | 21 (10) | 22 (11) | 16 (8) |

| 12–23 | 289 (70) | 14 (3) | 73 (16) | 40 (10) |

| ≥24 | 323 (61) | 28 (5) | 131 (25) | 44 (8) |

| Total | 763 (66) | 63 (6) | 226 (20) | 100 (9) |

Note. Immunologic response was defined according to WHO guidelines as after 6 months of treatment a CD4 count of greater than 100, baseline, and 50% of peak. Virologic response was defined as a viral load of less than 400 copies per mL after 6 months.

VL, viral load suppression; CD4, CD4 count response

Predictors of Viral Suppression

Five treatment characteristics were included in the age and gender adjusted multivariate modeling: ART duration, ART regimen, site type, regimen switch, and missed pills in the last 7 days. Adjusted odds ratios for failure to reach viral suppression are shown in Table 3. Care received at county level hospitals was superior to that received elsewhere with adjusted odds ratios for failure to reach viral suppression of 5.4 (95% CI, 2.9–10.1) for village clinics, 3.1 (1.7–5.6) for public health clinics, and 3.1 (CI, 1.7–5.6) for township health centers. Patients receiving ddI-based regimens experienced inadequate virologic response more frequently than those receiving 3TC-based regimens (AOR, 3.9; CI, 2.7–5.7). Missing pills in the last 7 days was also associated with inadequate virologic response (AOR, 1.9; CI, 1.2–3.0). Patients in longer treatment duration groups showed an insignificant trend towards higher failure.

Table 3.

Association of clinical and treatment characteristics with inadequate viral response for subjects in four separate logistic regression models for each treatment duration group among a stratified random sample of patients in 8 provinces in China, 2007

| Characteristic | All patients |

6–11 months |

12–23 months |

≥ 24 months |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % with VL > 400 |

Multivariate analysis, AOR (95% CI) |

P | % with VL > 400 |

Multivariate analysis, AOR (95% CI) |

P | % with VL > 400 |

Multivariate analysis, AOR (95% CI) |

P | % with VL > 400 |

Multivariate analysis, AOR (95% CI) |

P | |

| Initial treatment regimen | ||||||||||||

| AZT/d4T+3TC+NVP/EFV | 14.1 | Ref | 10.6 | Ref | 15.4 | Ref | 15.5 | Ref | ||||

| AZT/d4T+ddI+NVP/EFV | 44.3 | 3.9 (2.7–5.7) | <0.01 | 42.9 | 5.7 (2.6–12.8) | <0.01 | 59.3 | 5.6 (3.1–10.0) | <0.01 | 40.2 | 2.3 (1.3–4.2) | <0.01 |

| Other | 22.9 | 1.0 (0.4–2.9) | 0.98 | * | 21.4 | 1.0 (0.3–3.6) | 0.89 | 33.3 | 1.5 (0.1–16.2) | 0.76 | ||

| Treatment site | ||||||||||||

| County level hospital or above | 7.8 | Ref | NS | 10.1 | Ref | 6.1 | Ref | |||||

| Township health center | 30.7 | 3.1 (1.7–5.6) | <0.01 | … | 27 | 2.4 (1.0–5.7) | 0.04 | 31.7 | 3.3 (0.7–15.2) | 0.13 | ||

| Public health clinic | 24.9 | 3.1 (1.7–5.6) | <0.01 | … | 26.4 | 3.2 (1.4–7.0) | 0.01 | 27.4 | 3.6 (0.8–16.3) | 0.10 | ||

| Village clinic | 48.7 | 5.4 (2.9–10.1) | <0.01 | … | 57.1 | 5.9 (2.5–14.0) | <0.01 | 46 | 6.5 (1.4–29.9) | 0.02 | ||

| Self reported adherence in last 7 days | ||||||||||||

| No missed pills | 26.8 | Ref | 15.7 | Ref | NS | NS | ||||||

| Missed pills | 42.9 | 1.9 (1.2–3.0) | 0.01 | 53.8 | 4.9 (1.2–19.7) | 0.02 | … | … | ||||

| Ever switched regimens | ||||||||||||

| Not switched | NS | NS | NS | 25.4 | Ref | |||||||

| Switched | … | … | … | 45.2 | 2.1 (1.4–3.1) | <0.01 | ||||||

| Treatment duration, months | ||||||||||||

| 6–11 | 18.1 | Ref | NA | NA | NA | |||||||

| 12–23 | 27.2 | 1.5 (0.9–2.4) | 0.08 | … | … | … | ||||||

| ≥ 24 | 33.2 | 0.9 (0.5–1.4) | 0.57 | … | … | … | ||||||

Note. AOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; VL, viral load; AZT, zidovudine; d4T, stavudine; 3TC, lamivudine; NVP, nevirapine; EFV, efavirenz; ddI, didanosine; Ref, referent; NA, the covariate was not considered for modeling;

only one patient in group; NS, the covariate was either statistically insignificant or deleted from the model selection procedure

When results were stratified into individual models for each treatment duration group, compared to treatment at county level hospitals, treatment at all other facilities in the 12–23 month group and villages in the ≥ 24 month group was associated with failure to reach viral suppression. Compared to 3TC-based regimens, ddI-based regimens showed significantly increased AORs for failure to achieve viral suppression in all three treatment duration groups. Less than 100% adherence was associated with failure to achieve viral suppression only for the 6–11 month treatment group. Having changed regimens was associated with failure in the ≥24 month group.

Further stratification by drug regimen continued to demonstrate association of treatment facility and virologic success. Compared to patients receiving care in county level hospitals, adjusted odds ratios for failure to reach viral suppression, among patients receiving 3TC-based regimens, were 5.3 (CI, 2.1–13.3) for village clinics, 3.4 (1.6–6.9) for public health clinics, and 4.3 (CI, 2–9.4) for township health centers, and among those receiving ddI-based regimens, were 8.3 (CI, 2.1–33.5) for village clinics, 4.4 (CI 1.1–18.0) for public health clinics, and 3.9 (CI, 0.97–15.5) for township health centers.

The above associations continued to show significant relationships upon additional multivariate modeling adjusting for baseline CD4 count for the subset of patients with existing data, with the exception of regimen switch in the ≥24 month model. Upon sensitivity analysis, when indeterminate results were removed, all above findings maintained significant relationships except for facility type and treatment outcome association in the ≥24 month model and public health clinic inferiority in the ddI model.

Discussion

This is the first study in China to evaluate virologic suppression among a nationally selected sample of adult HIV-infected patients on ART. The findings demonstrate virologic success for the majority of adults receiving ART and show that initial regimen choice and type of care delivery site significantly affected virologic outcomes in 8 provinces in China. Overall, 72% of patients sampled demonstrated viral suppression with lower rates seen among those with longer treatment duration. Patients who were started on regimens containing ddI instead of 3TC experienced less favorable outcomes. Treatment delivered at county hospitals showed better virologic outcomes than that delivered elsewhere, with those patients treated at rural village health care facilities having the highest rate of virologic failure.

Virologic outcomes in this study compared favorably to those reported elsewhere. In studies of ART from developing countries worldwide, virologic control variably defined as viral load less than 200–500 has ranged from 72 to 90% at 6 months [18–20], 50 to 86% at 12 months [18, 19, 21–24], and for one study 81% at greater than 24 months [19]. An early clinical trial in developed countries using an AZT+ddI+NVP regimen only reduced viral load to under 400 in 50% of patients after one year of therapy [25]. Combined analysis of triple combination therapy trials shows non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor regimens to reduce viral load to less than 400 in 77% of patients at 24 weeks and 73% at 48 weeks [26].

In the current study, ddI-based regimens consistently demonstrated less favorable outcomes than those containing 3TC. Few existing studies have directly compared ddI and 3TC containing regimens [27]. While one trial showed superiority of AZT+3TC over ddI+d4T containing regimens [28], another showed no difference in virologic response between AZT+3TC+EFV and ddI+3TC+EFV regimens [29]. The few patients (9%) in this study reporting any missed pills in the last week demonstrated worse outcomes, consistent with prior work showing increased virologic failure with adherence under 95% [30]. Baseline CD4 count failed to predict virologic failure in a multivariable model of this population.

Our findings show that patients who received care in rural village clinics were significantly more likely to fail to achieve viral suppression than those in county-level hospitals staffed by trained physicians. Patients treated at public health clinics and township health centers also had less favorable outcomes, but this relationship did not reach statistical significance in models stratified by treatment duration. Although 3TC use was higher in county level hospitals suggesting confounding of treatment facility and regimen, when patients were compared only with others receiving the same treatment regimen, treatment facility remained significantly associated with virological outcome.

Since its inception in 2003, China’s HIV treatment program has been decentralized to village and township health centers in close proximity to the largely rural HIV-infected patient population. Task shifting to provision of ART by non-physicians and decentralization to rural clinics has been promoted by the WHO with excellent clinical outcomes in prior studies in the developing world [9, 24]. However, previous virologic outcome studies involving nonphysician clinicians have been limited to small geographic regions that received extensive support and training [31]. Task shifting is most successful when community health workers or nurses receive regular supervision from experienced ART providers [24]. Scaling up such oversight in China is challenging as there are over 3,700 sites of ART delivery spread across a large country. Regimen choice in China has expanded such that ddI is now used in less than 10% of initial ART regimens. Future efforts will focus on strengthening training programs for HIV care providers to improve the quality of care in remote clinics.

Determining viral load in a representative sample of HIV-infected patients on first-line ART is important for managing a maturing national treatment program. Excellent clinical and immunologic outcomes observed over short periods cannot capture the subtleties of treatment success and failure that virologic outcomes provide. Patients with discordant immunologic and virologic outcomes, accounting for 26% in this study, have shown significantly higher mortality in prior studies [32, 33]. If monitoring for treatment failure by clinical and immunologic criteria alone, some patients may be switched too early [34] and others too late [35] leading to drug resistance [36, 37].

The present study was limited by its cross-sectional nature. Only patients on therapy for greater than 6 months were considered; early failure and mortality were not studied. The ten percent of patients missing due to mortality, treatment termination, and loss to follow up likely introduce selection bias. However, their numbers are likely insufficient to alter the conclusions derived from multivariable modeling. If such missing patients are all considered failures, the overall projected virologic suppression rate of patients on therapy longer than 6 months would be 65%, thus confirming the overall high virologic suppression rate. Patients with indeterminate viral loads of 400–1,000 copies per mL could not be retested in this study, but were considered failures to maintain a conservative estimation of virologic suppression. Although cross-sectional assessment of virologic suppression is inherently inferior to longitudinal evaluation, where the availability of antiretroviral therapy predates that of viral load testing, cross-sectional evaluation may provide valuable insight in such situations where longitudinal study is impossible.

The National Free Antiretroviral Treatment Program in China has demonstrated reduced HIV-related mortality [4, 7, 14]. In this study, virologic outcomes, previously unreported on a national level were shown to be equal or superior to those reported in developing and even developed countries when similar methods were used. As the National Free Antiretroviral Treatment Program continues to further expand, intensive efforts will be required to ensure an increased drug supply and improved training and supervision, especially in rural segments of the health care system. Owing in part to the results of this study, financial support is now provided for free annual viral load testing nationwide.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge first and foremost the work of Chinese HIV healthcare providers for their tireless patient care and completion of forms necessary for maintenance of the National Free ART Database, without which this study could not have been completed. We would also like to acknowledge the work of research assistants involved in completing patient interviews. We thank the personnel from the Henan, Shanxi, Anhui, Hubei, Shandong, Jilin, and Guangxi Centers for Disease Control and the Yunnan HIV/AIDS Care Center for help in implementing this study. We also thank Drs. Jon Kaplan, Ray Chen, Elizabeth Marum, Thomas Warne, and Myron Cohen for thoughtful comments on an earlier version of the manuscript.

Financial support. The applied research program on AIDS prevention and treatment of the China Ministry of Health (WA-2006-03); U.S. National Institutes of Health, ICOHRTA grant (U2R TW006918); Doris Duke Charitable Foundation; UNC Center for AIDS Research; cooperative agreement from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Global AIDS Program (GAP) to the China CDC.

The U.S. sponsors were involved in the analysis and interpretation of the data and preparation, review, and approval of the manuscript through co-authors. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The corresponding author, Fujie Zhang, had full access to all study data and takes responsibility for its integrity and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Footnotes

Summary: Virologic outcomes of patients receiving HIV treatment in China has not been reported. Data from a multi-stage cluster selection of patients in eight provinces showed superior virologic outcomes for patients receiving lamivudine containing regimens and care in more advanced facilities.

Potential conflicts of interest. P.C. has received a research grant from Tibotec (REACH Initiative). Y.M, D.Z., L.Y., M.B., M.R., Y.Z., Z.D., X.W., and F.Z. No conflict.

References

- 1.UNAIDS/WHO Working Group on Global HIV/AIDS and STI Surveillance. Epidemiological Fact Sheets on HIV and AIDS. [Accessed 24 Dec 2008]; 2008 Update. Available at: http://www.who.int/globalatlas/predefinedReports/EFS2008/full/EFS2008_CN.pdf.

- 2.Xu JQ, Wang JJ, Han LF, et al. Epidemiology, clinical and laboratory characteristics of currently alive HIV-1 infected former blood donors naive to antiretroviral therapy in Anhui Province, China. Chin Med J (Engl) 2006;119:1941–1948. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu Z, Sullivan SG, Wang Y, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Detels R. Evolution of China's response to HIV/AIDS. Lancet. 2007;369:679–690. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60315-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qian HZ, Vermund SH. Editorial commentary: antiretroviral therapy for former plasma donors in China: saving lives when HIV prevention fails. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:834–836. doi: 10.1086/590940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Watts J. Sex, drugs, and HIV/AIDS in China. Lancet. 2008;371:103–104. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60087-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang F, Haberer JE, Wang Y, et al. The Chinese free antiretroviral treatment program: challenges and responses. AIDS. 2007;21 Suppl 8:S143–S148. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000304710.10036.2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang F, Dou Z, Ma Y, et al. Five Year Outcomes of the China National Free Antiretroviral Treatment Program. Ann Intern Med. 2009 doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00003. [in press]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization. Towards universal access: scaling up priority HIV/AIDS interventions in the health sector: progress report 2008. [Accessed 4 May 2009]; Available at: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/towards_universal_access_report_2008.pdf.

- 9.World Health Organization. Task Shifting: Global Recommendations and Guidelines. [Accessed 2 December 2008]; Available at: http://www.who.int/healthsystems/TTR-TaskShifting.pdf.

- 10.Samb B, Celletti F, Holloway J, Van Damme W, DeCock KM, Dybul M. Rapid expansion of the health workforce in response to the HIV epidemic. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2510–2514. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb071889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang F, editor. National Free HIV Antiretroviral Treatment Handbook. 2nd ed. Beijing: People's Medical Publishing House; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization. Antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection in adults and adolescents: recommendations for a public health approach. – 2006 rev. [Accessed 30 April 2009]; Available at: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/artadultguidelines.pdf. [PubMed]

- 13.Anand S, Fan VY, Zhang J, et al. China's human resources for health: quantity, quality, and distribution. Lancet. 2008;372:1774–1781. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61363-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang F, Dou Z, Yu L, et al. The effect of highly active antiretroviral therapy on mortality among HIV-infected former plasma donors in China. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:825–833. doi: 10.1086/590945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taylor WD, Bosch EG. The datafax project [abstract P-45] Controlled Clin Trials. 1990;11:296. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lu L, Jia M, Ma Y, et al. The changing face of HIV in China. Nature. 2008;455:609–611. doi: 10.1038/455609a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mee P, Fielding KL, Charalambous S, Churchyard GJ, Grant AD. Evaluation of the WHO criteria for antiretroviral treatment failure among adults in South Africa. AIDS. 2008;22:1971–1977. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32830e4cd8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spacek LA, Shihab HM, Kamya MR, et al. Response to antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected patients attending a public, urban clinic in Kampala, Uganda. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:252–259. doi: 10.1086/499044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boileau C, Nguyen VK, Sylla M, et al. Low prevalence of detectable HIV plasma viremia in patients treated with antiretroviral therapy in Burkina Faso and Mali. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;48:476–484. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31817dc416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tuboi SH, Harrison LH, Sprinz E, Albernaz RK, Schechter M. Predictors of virologic failure in HIV-1-infected patients starting highly active antiretroviral therapy in Porto Alegre, Brazil. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;40:324–328. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000182627.28595.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Djomand G, Roels T, Ellerbrock T, et al. Virologic and immunologic outcomes and programmatic challenges of an antiretroviral treatment pilot project in Abidjan, Cote d'Ivoire. AIDS. 2003;17 Suppl 3:S5–S15. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200317003-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tuboi SH, Brinkhof MW, Egger M, et al. Discordant responses to potent antiretroviral treatment in previously naive HIV-1-infected adults initiating treatment in resource-constrained countries: the antiretroviral therapy in low-income countries (ART-LINC) collaboration. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;45:52–59. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318042e1c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fielding KL, Charalambous S, Stenson AL, et al. Risk factors for poor virological outcome at 12 months in a workplace-based antiretroviral therapy programme in South Africa: a cohort study. BMC Infect Dis. 2008;8:93. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-8-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bedelu M, Ford N, Hilderbrand K, Reuter H. Implementing antiretroviral therapy in rural communities: the Lusikisiki model of decentralized HIV/AIDS care. J Infect Dis. 2007;196 Suppl 3:S464–S468. doi: 10.1086/521114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Montaner JS, Reiss P, Cooper D, et al. A randomized, double-blind trial comparing combinations of nevirapine, didanosine, and zidovudine for HIV-infected patients: the INCAS Trial. Italy, The Netherlands, Canada and Australia Study. JAMA. 1998;279:930–937. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.12.930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bartlett JA, Fath MJ, Demasi R, et al. An updated systematic overview of triple combination therapy in antiretroviral-naive HIV-infected adults. AIDS. 2006;20:2051–2064. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000247578.08449.ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carr A, Amin J. Efficacy and tolerability of initial antiretroviral therapy: a systematic review. AIDS. 2009;23:343–353. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32831db232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shafer RW, Smeaton LM, Robbins GK, et al. Comparison of four-drug regimens and pairs of sequential three-drug regimens as initial therapy for HIV-1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2304–2315. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Berenguer J, Gonzalez J, Ribera E, et al. Didanosine, lamivudine, and efavirenz versus zidovudine, lamivudine, and efavirenz for the initial treatment of HIV type 1 infection: final analysis (48 weeks) of a prospective, randomized, noninferiority clinical trial, GESIDA 3903. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:1083–1092. doi: 10.1086/592114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bisson GP, Rowh A, Weinstein R, Gaolathe T, Frank I, Gross R. Antiretroviral failure despite high levels of adherence: discordant adherence-response relationship in Botswana. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;49:107–110. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181820141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stringer JS, Zulu I, Levy J, et al. Rapid scale-up of antiretroviral therapy at primary care sites in Zambia: feasibility and early outcomes. JAMA. 2006;296:782–793. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.7.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moore DM, Hogg RS, Yip B, et al. Discordant immunologic and virologic responses to highly active antiretroviral therapy are associated with increased mortality and poor adherence to therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;40:288–293. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000182847.38098.d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tan R, Westfall AO, Willig JH, et al. Clinical outcome of HIV-infected antiretroviral-naive patients with discordant immunologic and virologic responses to highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;47:553–558. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31816856c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kantor R, Diero L, Delong A, et al. Misclassification of first-line antiretroviral treatment failure based on immunological monitoring of HIV infection in resource-limited settings. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:454–462. doi: 10.1086/600396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bennett DE, Bertagnolio S, Sutherland D, Gilks CF. The World Health Organization's global strategy for prevention and assessment of HIV drug resistance. Antivir Ther. 2008;13 Suppl 2:1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cozzi-Lepri A, Phillips AN, Ruiz L, et al. Evolution of drug resistance in HIV-infected patients remaining on a virologically failing combination antiretroviral therapy regimen. AIDS. 2007;21:721–732. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3280141fdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hosseinipour M, van Oosterhout JJ, Weigel R, et al. Resistance profile of patients failing first line ART in Malawi when using clinical and immunologic monitoring [abstract TUAB0105]. Geneva. Program and abstracts of the XVII International AIDS Conference (Mexico City); International AIDS Society; 2008. [Google Scholar]