Abstract

Nanowire/nanotube biosensors have stimulated significant interest; however the inevitable device-to-device variation in the biosensor performance remains a great challenge. We have developed an analytical method to calibrate nanowire biosensor responses that can suppress the device-to-device variation in sensing response significantly. The method is based on our discovery of a strong correlation between the biosensor gate dependence (dIds/dVg) and the absolute response (absolute change in current, ΔI). In2O3 nanowire based biosensors for streptavidin detection were used as the model system. Studying the liquid gate effect and ionic concentration dependence of strepavidin sensing indicates that electrostatic interaction is the dominant mechanism for sensing response. Based on this sensing mechanism and transistor physics, a linear correlation between the absolute sensor response (ΔI) and the gate dependence (dIds/dVg) is predicted and confirmed experimentally. Using this correlation, a calibration method was developed where the absolute response is divided by dIds/dVg for each device, and the calibrated responses from different devices behaved almost identically. Compared to the common normalization method (normalization of the conductance/resistance/current by the initial value), this calibration method was proved advantageous using a conventional transistor model. The method presented here substantially suppresses device-to-device variation, allowing the use of nanosensors in large arrays.

Keywords: Nanowire, nanobiosensor, calibration method, sensing mechanism

Introduction

Biological sensors based on nanowire/nanotube field effect transistors (FETs) are one of the most promising applications of bionanotechnology. As a proof of their promising capabilities, nanowire/nanotube sensors have been used to detect a large variety of biological molecules, ranging from proteins to nucleotide sequences;1–15 to monitor enzymatic activities;16 and to observe cellular signaling/responses,17–19 with sensitivity and response time comparable or better than conventional techniques (ELISA). An important challenge holding back the practical application of nanobiosensors to bio-analytical measurements is the device-to-device variation in the device properties such as conductance, threshold voltage, and transconductance. This variation exists between devices on different substrates as well as between devices within an array on a single substrate.20, 21 This results in unreliable detection, making quantitative analysis difficult. This challenge must be addressed to bridge the gap between academic research and practical use of the technology.

While effort has been devoted to the fabrication of more uniform devices,5, 9, 22–40 there have been few reports tackling the problem with a data analysis approach. Recently it was reported that the Langmuir isotherm model can be used to calibrate the sensor performance of carbon nanotube biosensors.41 While this method is effective in reducing response discrepancies, it requires testing of several different analyte concentrations for each device to use Langmuir fitting, developing a unique calibration curve for each device. We report herein an analytical method to calibrate nanowire biosensors, which gives significantly suppressed device-to-device variation in sensing response. We use the correlation between the biosensor gate dependence and the absolute responses (absolute change in current, ΔI) as the basis of the calibration method. In2O3 nanowire FET based biosensors for streptavidin were used as a model system, to demonstrate that an electrostatic interaction is the dominant sensing mechanism. We developed a calibration method involving dividing the absolute response by dIds/dVg for each device, which markedly improved the device-to-device variation, as verified by the much reduced coefficient of variance (CV) from 59% for the absolute response to 25% for the calibrated response, respectively. The superiority of this calibration method to the common normalization method is shown mathematically using a conventional transistor model, and experimentally confirmed. Our method is a significant step forward toward the broader application of nanowire biosensors.

Results and Discussion

Variation of as-made biosensors

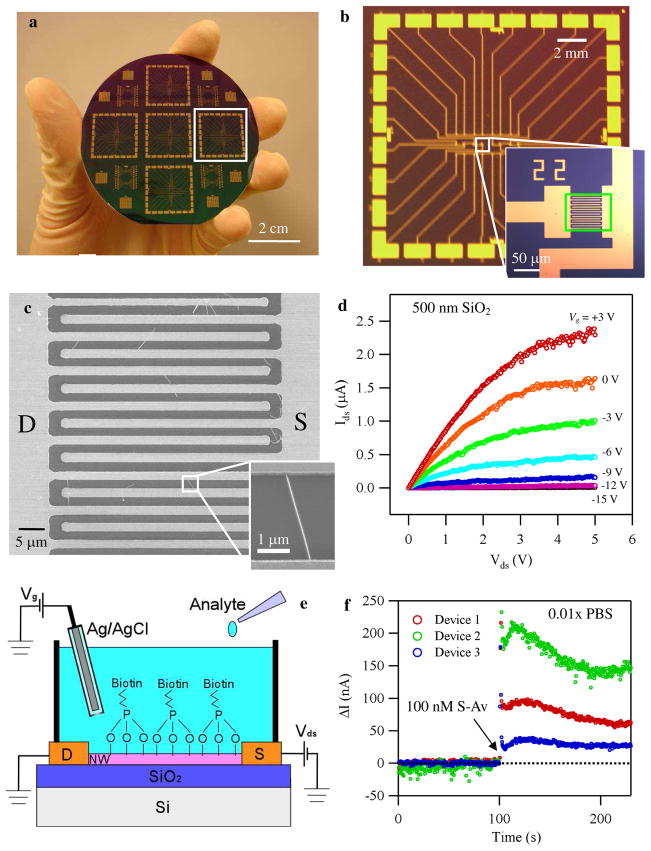

Our sensing devices based on indium oxide nanowires were fabricated following a previously developed procedure.4, 42, 43 The only deviation from this procedure is a novel design of interdigitated source and drain electrodes that resulted in high yield (Figure 1a–c). Details of the fabrication are in the method section. We note that this procedure allows inexpensive and scalable fabrication with an uniformity similar to the one obtained with an aid of Langmuir-Blodgett assembly.20 The uniformity of our device in terms of threshold voltage is shown in Figure S1. Figure 1a shows the photograph of a complete 3″ wafer with multiple biosensor chips. Figure 1b shows one of the chips and the inset displays a typical device with interdigitated electrodes, which serve to increase the effective channel width and subsequently the probability of contacting multiple nanowires for each device. In this design, we used three different effective channel widths of 480, 780, and 2600 μm, with fixed channel length of 2.5 μm. Typically one device of 780 μm channel width contains about 10 nanowires in the channel as shown in Figure 1c. The inset shows a magnified SEM image of one nanowire in the channel. The use of multiple nanowires per sensor offers high device yield (~70%) and small device-to-device variation (Figure S1). The above described procedure also allows for device fabrication on unconventional substrates, such as polyethylene terephthalate and glass. Moreover, biocompatible, FDA-approved materials such as parylene can be used as the substrate, allowing for in-vivo, flexible sensors.

Figure 1.

a) An optical micrograph of a 3″ wafer with multiple biosensor chips. b) A photograph of one chip with an inset showing an optical image of the interdigitated electrodes. c) A SEM image of multiple In2O3 nanowires between the source and drain electrodes. The inset is a magnified image of an individual nanowire. d) Ids-Vds plots under different Vg. e) Schematic diagram of the sensing setup illustrating an FET biosensor device operated by the liquid gate. f) Typical plots of the change in current versus time for three devices which were exposed to streptavidin (S-Av) of 100 nM at t = 100 s in 0.01× PBS. Vds of 0.2 V and Vg of 0.6 V were used for the measurement.

The transistor properties of the devices were characterized, with the Si substrate as a back gate and 500 nm SiO2 as a dielectric layer. Plots of drain-source (D-S) current (Ids) versus D-S voltage (Vds) under different gate voltage (Vg) for a typical transistor are shown in Figure 1d. The device exhibited a MOSFET like transistor behavior, and the linear regime can be well described by the conventional MOSFET equation (Eq.1, see also Figure S2);

| (1) |

where e is the elementary charge, μ is the device mobility, ε is the permitivity of vacuum, εr is the permitivity of SiO2, A is the area of the channel, d is the spacing of the capacitor, L is the channel length, VT is the threshold voltage, and gm is the transconductance of the device. The linearity of Ids at small Vds confirms the negligible contact resistance. The on/off ratio of this device reached ~105. By carefully optimizing the density of NWs, we have demonstrated that about 70% of the devices showed an on/off ratio > 102. Only those were used in the following experiments.

Throughout this paper, we employed liquid gate measurements, in order to characterize and evaluate our devices under conditions as close as possible to the active sensing condition. This method was developed previously to gain insights on how biomolecules interact with sensors.44 Our experimental setup for active measurements using the liquid gate configuration is schematically illustrated in Figure 1e. A device-under-test was fitted with a Teflon cell and the cell was then filled with 1 ml of phosphate buffered saline (PBS) solution. An Ag/AgCl reference electrode was inserted in the buffer that served as a liquid gate.45 We confirmed that the leakage current is negligible compared to the current through the nanowires via control experiments (Figure S3 and ref. 44).46 For real-time biosensing experiments, after establishing a baseline, analyte solutions of interest were added to the buffer, and the change of the device characteristics was monitored over time. We note that for some of the measurements done below (Figure 1f, 2b, and 5a), continuous mixing of the buffer was performed by applying a constant continuous flow of air to the surface of the buffer solution in order to 1) minimize the mechanical/electrical perturbation to the system due to the addition of the analytes and 2) accelerate the mixing of the solutions.

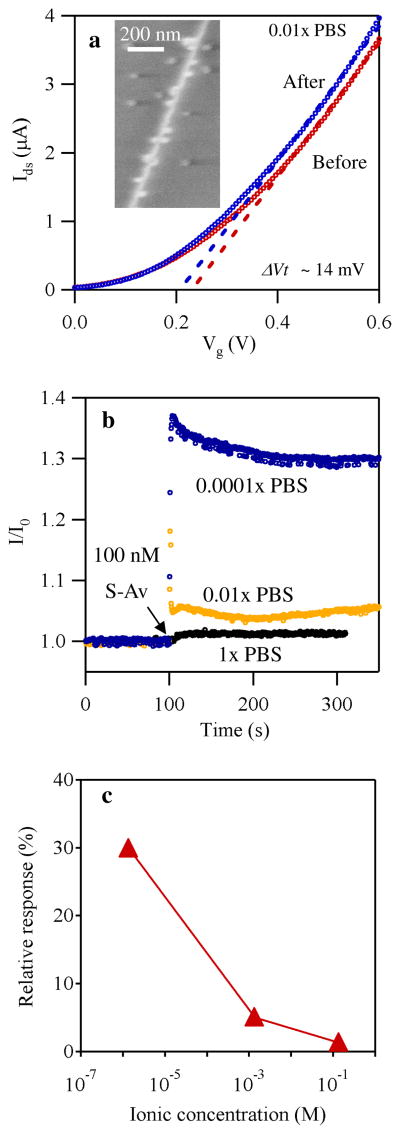

Figure 2.

a) Ids versus Vg using the liquid gate before (red) and after (blue) exposure to streptavidin of 100 nM in 0.01× PBS. b) Plots of current versus time in PBS of different levels of dilution. The devices were exposed to 100 nM streptavidin at t = 100 s. Vds of 0.2 V and Vg of 0.6 V were used for the measurement. c) Relative responses extracted from Figure 2b plotted against the logarithm of the ionic concentration.

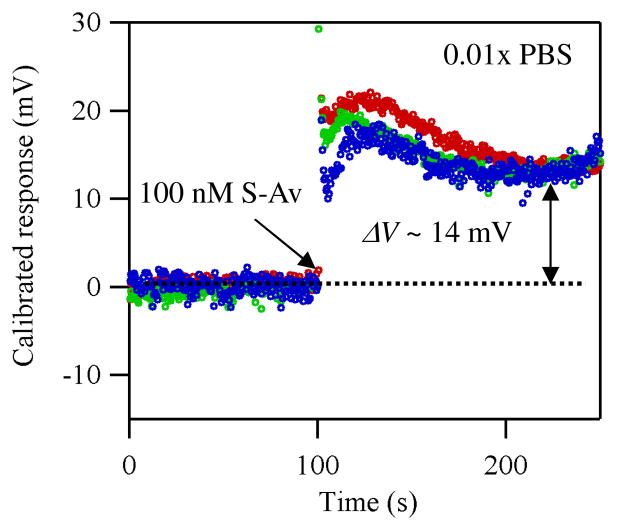

Figure 5.

Plots of the calibrated response using the data shown in Figure 1d.

We used streptavidin (S-Av) as the analyte and biotin as the receptor, since the system has been studied extensively.47, 48 Biotin was attached to the nanowire surface through previously developed chemical procedure for our In2O3 nanowire biosensors.4 A typical result of a real-time biosensing measurement is shown in Figure 1f, where three devices functionalized with biotin were exposed to a solution of 100 nM streptavidin at t = 100 s in 0.01× PBS. The change upon exposure, in terms of the absolute change in Ids (ΔI), was 210, 95, and 35 nA for devices 2, 1, and 3, respectively. Clearly, there is a significant device-to-device variation.

Elucidation of Sensing Mechanism

We first investigated the physics leading to sensing signals for our In2O3 nanowire biosensors using biotin and streptavidin (S-Av) as a receptor/analyte model system. The change in the Ids-Vg characteristics upon exposure to streptavidin (100 nM) was examined.44 The experiment was carried out in 0.01× PBS. Figure 2a shows typical Ids-Vg curves from a device before and after exposure to a solution of 100 nM streptavidin, where a clear difference was observed indicating successful sensing. The direction of the response is consistent with previous reports, which suggested that streptavidin contains amine base groups closer to the binding pocket, resulting in bringing positive charges close to the nanowires.3, 49 We found that the change of the Ids-Vg after the binding can be described as a parallel shift of the Ids-Vg by ~14 mV (Figure S4). These observations were consistently reproduced over a large number of devices. Based on the observations, we attributed doping of nanowires by the analytes as the dominant sensing mechanism for In2O3 nanowire biosensors in the conditions used here, since under other possible mechanisms proposed before, such as change in dielectric constant and mobility, it must be accompanied with a change in the transconductance.44, 50 We note that the observed shifts in the Ids-Vg are not due to device instability over time or a perturbation caused by adding a liquid, as verified by repeatedly measuring the Ids-Vg and monitoring the change of on-current (Ids at Vg = 0.6 V) over time. The change in Ids-Vg curves was only observed with the introduction of streptavidin (Figure S5), while the current was stable before the introduction of streptavidin. We also note that there was no change when PBS was added to the solution. Furthermore, we have conducted a control experiment to confirm the binding of streptavidin, in which the nanowires with biotin were exposed to a solution of streptavidin tagged with 10 nm Au nanoparticles. The inset in Figure 2a is a typical SEM image of an In2O3 nanowire after the exposure, showing the binding of streptavidin molecules with the gold particles onto the nanowires.

The results described above show that “doping” is the dominant mechanism behind the generation of a sensing signal. Such doping can be classified into two categories: charge transfer50 and electrostatic interaction.44 The former depends on the alignment of the chemical potential between the analyte and the sensor51 as well as on the charge transfer resistance.52 In contrast, the electrostatic interaction does not require the direct transfer of carriers through the interface, and has a characteristic screening length (Debye length, λD) associated with the dielectric properties of the environment through which the electrostatic interaction takes place (buffer and In2O3 nanowire in our case).53, 54 To establish which type of doping is at the origin of the sensing mechanism for our biosensors, the device response to 100 nM streptavidin was tested in buffers with three different electrolyte concentrations, thus different Debye lengths. Figure 2b shows Ids versus time plots in 1× PBS (black, λD=0.7nm), 0.01× PBS (yellow, λD=7nm), and 0.0001x PBS (blue, λD=70nm), when the device was exposed to 100 nM streptavidin solution at t = 100 s. The extracted relative response is plotted versus ionic concentration in Figure 2c. The strong dependence of the responses to the ionic concentration indicates that the sensing is done by electrostatic interaction rather than charge transfer for our In2O3 nanowires.

Correlation between Transistor Performance and Biosensor Performance

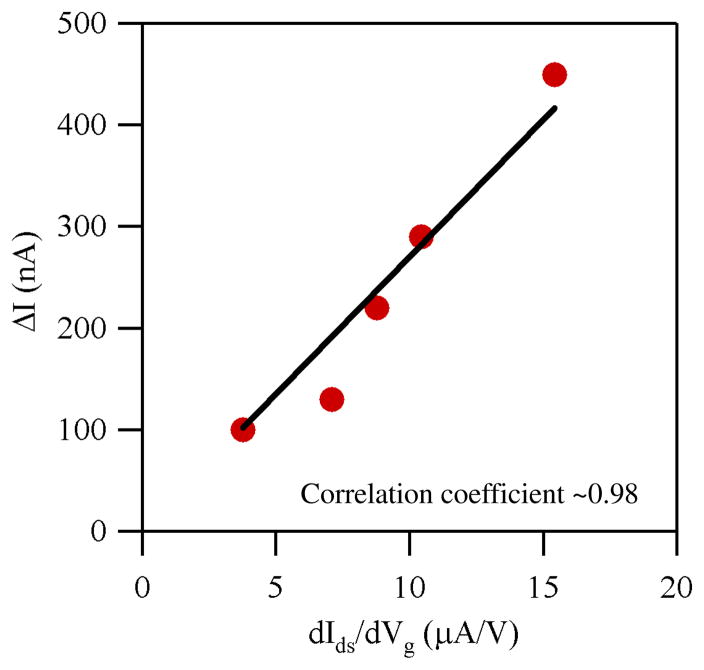

Based on the device characteristics described above, we propose a metric to predict/calibrate the biosensor performance in terms of the absolute response (ΔI). The metric dIds/dVg will correlate the absolute response (ΔI) with the change in effective gate voltage induced by binding of biomolecules. The correlation of dIds/dVg to the device sensitivity was investigated as follows: Ids-Vg measurements were performed on several devices using a liquid gate in 0.01× PBS, and dIds/dVg determined at Vds = 200 mV. The devices were then exposed to 100 nM streptavidin, and the Ids-Vg measurement was performed again. The absolute response (ΔI) for each device was calculated, and correlated to dIds/dVg by linear fitting. Data points at Vg = 0.6 V were used for the analysis here. Shown in Figure 3 is a plot of the absolute response versus dIds/dVg with a linear fitting (black solid line) for five different devices. The fitting yielded a correlation coefficient of ~0.98, proving the solid correlation between those two values. We note that a similar analysis at different gate voltages also revealed consistent results. This correlation was used to calibrate the sensor responses as shown in the next section.

Figure 3.

Plots of absolute response versus dIds/dVg for five devices. The solid line represents the fitting assuming a linear correlation, which yielded a correlation coefficient of ~0.98.

While it is not the main point of this paper, we note that the correlation can be also used to predict the behavior of a given transistor as a biosensor. As a consequence, a feedback loop can be used to design improved biosensors with shorter feedback time. In addition, the results indicate one can tune the magnitude of the response of a biosensor by applying an appropriate gate voltage to maximize the value of dIds/dVg. In fact, the plot of dIds/dVg versus the absolute response revealed a clear correlation between them, and the gate voltage that gives the maximum dIds/dVg gives the maximum absolute response (Figure S6). Further discussions can be found in the supporting information.

Calibration of Sensor Response

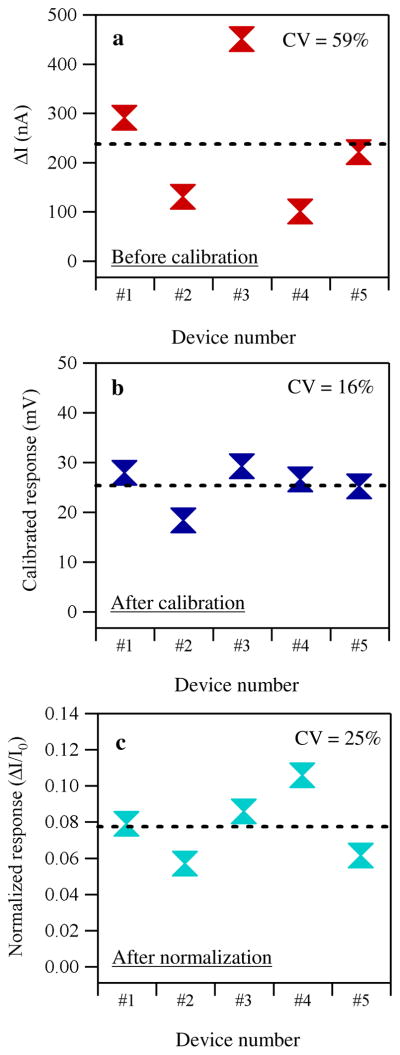

The metric dIds/dVg can be used to calibrate the sensor response. We have found that this calibration is achieved by dividing the absolute responses (ΔI) by dIds/dVg, which is hereafter referred to as “calibrated response.” As an example, Figure 4a shows absolute responses plotted against the device identification numbers together with an average of the responses before the calibration. By performing the calibration, we significantly reduce the device-to-device variation as shown in Figure 4b. The improvement was statistically verified by calculating the coefficient of variation (CV) for each set of data, where CV is defined as follows:

| (2) |

where σ is the standard deviation and μ is the mean. CV was reduced from 59% for the absolute response to 16% for the calibrated response, confirming the much reduced device-to-device variation after calibration. For comparison, we also performed the conventional normalization method, where the current/resistance/conductance was normalized by the initial value. The result is shown in Figure 4c. CV of the normalized response is 25%, which is slightly higher than that of calibrated response. This is as expected according to the analysis shown below.

Figure 4.

a) Plots of the absolute responses for five devices versus the device identification number before the calibration. b) Same plots after the calibration. The vertical axis was switched to the calibrated response. c) Same plots after the conventional normalization. The vertical axis is the normalized response.

We also performed the same calibration on the data shown in Figure 1d to show that the method works for real-time measurements. Figure 5 shows the plots of the resultant calibrated responses. It is clear that the large device-to-device variation observed in Figure 1d is significantly reduced by the calibration, confirming the applicability of our method to real-time biosensing. We note that the calibrated responses (change) of ~14 mV for the real-time measurement are consistent with the number observed for the Ids-Vg measurement (~14 mV).

The physical meaning of this calibration is to translate the response (change) in current to responses (change) in voltage that is delivered by the analyte. This translation leads to an advantage of our calibration method compared to the conventional method where the change was normalized by the initial conductance/current/resistance, as shown below. Applying the conventional MOSFET model (Eq.1),55 Ids before/after the exposure to proteins can be expressed as follows:

| (3a) |

| (3b) |

where the characters with subscript 1 are for the parameters before exposure to biomolecules, and subscript 2 for the device after exposure to biomolecules. Our metric dIds/dVg can be expressed as:

| (4) |

When electrostatic interaction is the dominant sensing mechanism, Iafter can be written as:

| (5) |

where ΔV is the equivalent gating voltage (potential) induced by the biomolecules. Using these equations, we can express the normalized response (ΔI/I0) as follows:

| (6a) |

while the calibrated response (ΔI/(dIds/dVg)) can be expressed as follows:

| (6b) |

As can be seen in the equations (6a and b), the normalized response is still affected by VT1, which is subject to device-to-device variation. On the other hand, the calibrated response is no longer a function of the device performance, and it only depends on the equivalent gate potential induced by the biomolecules (ΔV). Therefore, our calibration method is superior to the conventional normalization since it excludes the device-to-device variation in terms of threshold voltage variation. Indeed, this was experimentally confirmed by us, as the normalized response showed larger CV (25%) than that of the calibrated responses (19%) as previously shown in Figure 4. Our method is a powerful tool for calibrating the sensor response of biosensors, especially for devices in which it is more challenging to get uniform VT, such as carbon nanotube biosensors. We note that biosensing experiments are usually carried out with small Vds (i.e., in the linear regime) to avoid electrochemical reaction which may be induced by large Vds; however, the method works as long as Ids is linearly dependent on Vg within small variation (equivalent ΔV induced by binding of biomolecules). Even for the saturation regime, while Ids is proportional to Vg2 over a large range, the Ids-Vg within small variation of Vg can still be approximated with a linear curve.

Conclusions

In summary, we have performed a comprehensive study on In2O3 nanowire biosensors, and successfully developed a calibration method to reduce the device-to-device variation in the sensor responses. The method is based on a correlation we found between the absolute responses and the gate dependence of the biosensors measured by means of a liquid gate. Our study of the sensing mechanism of In2O3 nanowire biosensors using streptavidin as a model analyte first revealed that electrostatic interaction is the dominant sensing mechanism, similar to other nanowire biosensors (mostly based on silicon nanowires). Based on the sensing mechanism, we proposed that there is a strong correlation between the responses of the biosensors and gate dependence of the devices, and the correlation was confirmed experimentally. Lastly, using the correlation, we developed a data analysis method to calibrate the sensor performance by dividing the absolute response by the gate dependence of each device. Then we successfully reduced the device-to-device variation in the sensor response as verified by the reduced CV from 59% before the calibration to 19% after the calibration. We believe our method will be useful for other nanowire and nanotube FET-based sensor arrays, making multiplexed sensor arrays a practical solution for measuring/monitoring multiple analytes (biomarkers) simultaneously.

Method

In2O3 nanowires were grown on a Si/SiO2 substrate using the laser ablation method and dispersed in isopropanol by sonication. The suspension of nanowires in isopropanol was dropped onto a Si/SiO2 substrate, typically a 3″ wafer, generating a random distribution of nanowires, with roughly 1 nanwires per 100 μm2. The thickness of the SiO2 capping layer was 500 nm, unless otherwise stated. Following that was deposition of metal contacts using photolithography and lift-off technique. A bilayer of 10 nm Cr and 40 nm Au was used as the contact for our case.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge financial support from the L.K. Whittier Foundation, the National Institute of Health, and the National Science Foundation (CCF-0726815 and CCF-0702204).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. Distribution of threshold voltage of In2O3 nanowire transistors, simulation of In2O3 nanowire transistor behavior through conventional MOSFET equation, measurement of leakage, change of Ids-Vg before/after the exposure to streptavidin, new feedback loop for designing new nanobiosensors, stability of the Ids-Vg measurements using liquid gate, and tuning of the magnitude of absolute responses by gate voltage. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Cui Y, Wei QQ, Park HK, Lieber CM. Nanowire Nanosensors for Highly Sensitive and Selective Detection of Biological and Chemical Species. Science. 2001;293:1289–1292. doi: 10.1126/science.1062711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen RJ, Bangsaruntip S, Drouvalakis KA, Kam NWS, Shim M, Li YM, Kim W, Utz PJ, Dai HJ. Noncovalent Functionalization of Carbon Nanotubes for Highly Specific Electronic Biosensors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:4984–4989. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0837064100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Star A, Gabriel JCP, Bradley K, Gruner G. Electronic Detection of Specific Protein Binding Using Nanotube FET Devices. Nano Lett. 2003;3:459–463. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li C, Curreli M, Lin H, Lei B, Ishikawa FN, Datar R, Cote RJ, Thompson ME, Zhou CW. Complementary Detection of Prostate-Specific Antigen Using In2O3 Nanowires and Carbon Nanotubes. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:12484–12485. doi: 10.1021/ja053761g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bunimovich YL, Shin YS, Yeo WS, Amori M, Kwong G, Heath JR. Quantitative Real-Time Measurements of DNA Hybridization with Alkylated Nonoxidized Silicon Nanowires in Electrolyte Solution. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:16323–16331. doi: 10.1021/ja065923u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patolsky F, Zheng G, Lieber CM. Nanowire Sensors for Medicine and the Life Sciences. Nanomedicine. 2006;1:51–65. doi: 10.2217/17435889.1.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patolsky F, Zheng GF, Lieber CM. Nanowire-Based Biosensors. Anal Chem. 2006;78:4260–4269. doi: 10.1021/ac069419j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Star A, Tu E, Niemann J, Gabriel JCP, Joiner CS, Valcke C. Label-Free Detection of DNA Hybridization Using Carbon Nanotube Network Field-Effect Transistors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:921–926. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504146103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stern E, Klemic JF, Routenberg DA, Wyrembak PN, Turner-Evans DB, Hamilton AD, LaVan DA, Fahmy TM, Reed MA. Label-Free Immunodetection with CMOS-Compatible Semiconducting Nanowires. Nature. 2007;445:519–522. doi: 10.1038/nature05498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Curreli M, Zhang R, Ishikawa FN, Chang HK, Cote RJ, Zhou C, Thompson ME. Real-Time, Label-Free Detection of Biological Entities Using Nanowire-Based FETs. IEEE Trans Nanotechnol. 2008;7:651–667. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tang XW, Bansaruntip S, Nakayama N, Yenilmez E, Chang YL, Wang Q. Carbon Nanotube DNA Sensor and Sensing Mechanism. Nano Lett. 2006;6:1632–1636. doi: 10.1021/nl060613v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abe M, Murata K, Kojima A, Ifuku Y, Shimizu M, Ataka T, Matsumoto K. Quantitative Detection of Protein Using a Top-Gate Carbon Nanotube Field Effect Transistor. J Phys Chem C. 2007;111:8667–8670. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang GJ, Zhang G, Chua JH, Chee RE, Wong EH, Agarwal A, Buddharaju KD, Singh N, Gao ZQ, Balasubramanian N. DNA Sensing by Silicon Nanowire: Charge Layer Distance Dependence. Nano Lett. 2008;8:1066–1070. doi: 10.1021/nl072991l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim A, Ah CS, Yu HY, Yang JH, Baek IB, Ahn CG, Park CW, Jun MS, Lee S. Ultrasensitive, Label-Free, and Real-Time Immunodetection Using Silicon Field-Effect Transistors. Appl Phys Lett. 2007;91:103901–103903. [Google Scholar]

- 15.So HM, Park DW, Jeon EK, Kim YH, Kim BS, Lee CK, Choi SY, Kim SC, Chang H, Lee JO. Detection and Titer Estimation of Escherichia Coli Using Aptamer-Functionalized Single-Walled Carbon-Nanotube Field-Effect Transistors. Small. 2008;4:197–201. doi: 10.1002/smll.200700664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Besteman K, Lee JO, Wiertz FGM, Heering HA, Dekker C. Enzyme-Coated Carbon Nanotubes as Single-Molecule Biosensors. Nano Lett. 2003;3:727–730. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patolsky F, Timko BP, Yu GH, Fang Y, Greytak AB, Zheng GF, Lieber CM. Detection, Stimulation, and Inhibition of Neuronal Signals with High-Density Nanowire Transistor Arrays. Science. 2006;313:1100–1104. doi: 10.1126/science.1128640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stern E, Steenblock ER, Reed MA, Fahmy TM. Label-Free Electronic Detection of the Antigen-Specific T-Cell Immune Response. Nano Lett. 2008;8:3310–3314. doi: 10.1021/nl801693k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang CW, Pan CY, Wu HC, Shih PY, Tsai CC, Liao KT, Lu LL, Hsieh WH, Chen CD, Chen YT. In Situ Detection of Chromogranin a Released from Living Neurons with a Single-Walled Carbon-Nanotube Field-Effect Transistor. Small. 2007;3:1350–1355. doi: 10.1002/smll.200600723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jin S, Whang DM, McAlpine MC, Friedman RS, Wu Y, Lieber CM. Scalable Interconnection and Integration of Nanowire Devices without Registration. Nano Lett. 2004;4:915–919. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patolsky F, Zheng GF, Lieber CM. Fabrication of Silicon Nanowire Devices for Ultrasensitive, Label-Free, Real-Time Detection of Biological and Chemical Species. Nature Protocols. 2006;1:1711–1724. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith PA, Nordquist CD, Jackson TN, Mayer TS, Martin BR, Mbindyo J, Mallouk TE. Electric-Field Assisted Assembly and Alignment of Metallic Nanowires. Appl Phys Lett. 2000;77:1399–1401. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang Y, Duan XF, Wei QQ, Lieber CM. Directed Assembly of One-Dimensional Nanostructures into Functional Networks. Science. 2001;291:630–633. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5504.630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tao A, Kim F, Hess C, Goldberger J, He RR, Sun YG, Xia YN, Yang PD. Langmuir-Blodgett Silver Nanowire Monolayers for Molecular Sensing Using Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy. Nano Lett. 2003;3:1229–1233. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rao SG, Huang L, Setyawan W, Hong SH. Large-Scale Assembly of Carbon Nanotubes. Nature. 2003;425:36–37. doi: 10.1038/425036a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim Y, Minami N, Zhu WH, Kazaoui S, Azumi R, Matsumoto M. Langmuir-Blodgett Films of Single-Wall Carbon Nanotubes: Layer-by-Layer Deposition and in-Plane Orientation of Tubes. Jpn J Appl Phys. 2003;42:7629–7634. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsukruk VV, Ko H, Peleshanko S. Nanotube Surface Arrays: Weaving, Bending, and Assembling on Patterned Silicon. Phys Rev Lett. 2004;92:65502–65505. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.92.065502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Han S, Liu XL, Zhou CW. Template-Free Directional Growth of Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes on a- and R-Plane Sapphire. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:5294–5295. doi: 10.1021/ja042544x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kocabas C, Hur SH, Gaur A, Meitl MA, Shim M, Rogers JA. Guided Growth of Large-Scale, Horizontally Aligned Arrays of Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes and Their Use in Thin-Film Transistors. Small. 2005;1:1110–1116. doi: 10.1002/smll.200500120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang YH, Maspoch D, Zou SL, Schatz GC, Smalley RE, Mirkin CA. Controlling the Shape, Orientation, and Linkage of Carbon Nanotube Features with Nano Affinity Templates. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:2026–2031. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511022103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee M, Im J, Lee BY, Myung S, Kang J, Huang L, Kwon YK, Hong S. Linker-Free Directed Assembly of High-Performance Integrated Devices Based on Nanotubes and Nanowires. Nature Nanotechnol. 2006;1:66–71. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2006.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu XL, Han S, Zhou CW. Novel Nanotube-on-Insulator (Noi) Approach toward Single-Walled Carbon Nanotube Devices. Nano Lett. 2006;6:34–39. doi: 10.1021/nl0518369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yu GH, Cao AY, Lieber CM. Large-Area Blown Bubble Films of Aligned Nanowires and Carbon Nanotubes. Nature Nanotechnol. 2007;2:372–377. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2007.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li XL, Zhang L, Wang XR, Shimoyama I, Sun XM, Seo WS, Dai HJ. Langmuir-Blodgett Assembly of Densely Aligned Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes from Bulk Materials. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:4890–4891. doi: 10.1021/ja071114e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fan ZY, Ho JC, Jacobson ZA, Razavi H, Javey A. Large-Scale, Heterogeneous Integration of Nanowire Arrays for Image Sensor Circuitry. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:11066–11070. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801994105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heo K, Cho E, Yang JE, Kim MH, Lee M, Lee BY, Kwon SG, Lee MS, Jo MH, Choi HJ, Hyeon T, Hong S. Large-Scale Assembly of Silicon Nanowire Network-Based Devices Using Conventional Microfabrication Facilities. Nano Lett. 2008;8:4523–4527. doi: 10.1021/nl802570m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li MW, Bhiladvala RB, Morrow TJ, Sioss JA, Lew KK, Redwing JM, Keating CD, Mayer TS. Bottom-up Assembly of Large-Area Nanowire Resonator Arrays. Nature Nanotechnol. 2008;3:88–92. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2008.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fan ZY, Ho JC, Jacobson ZA, Yerushalmi R, Alley RL, Razavi H, Javey A. Wafer-Scale Assembly of Highly Ordered Semiconductor Nanowire Arrays by Contact Printing. Nano Lett. 2008;8:20–25. doi: 10.1021/nl071626r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Monica AH, Papadakis SJ, Osiander R, Paranjape M. Wafer-Level Assembly of Carbon Nanotube Networks Using Dielectrophoresis. Nanotechnol. 2008;19:85303–85307. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/19/8/085303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Agarwal A, Buddharaju K, Lao IK, Singh N, Balasubramanian N, Kwong DL. Silicon Nanowire Sensor Array Using Top-Down CMOS Technology. Sens Actuators, A. 2008;145:207–213. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abe M, Murata K, Ataka T, Matsumoto K. Calibration Method for a Carbon Nanotube Field-Effect Transistor Biosensor. Nanotechnol. 2008;19:45505–45508. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/19/04/045505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li C, Zhang D, Han S, Liu X, Tang T, Lei B, Liu Z, Zhou C. Synthesis, Electronic Properties, and Applications of Indium Oxide Nanowires. Molecular Electronics Iii. 2003;1006:104–121. doi: 10.1196/annals.1292.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lei B, Li C, Zhang D, Tang T, Zhou C. Tuning Electronic Properties of In2o3 Nanowires by Doping Control. Appl Phys A. 2004;79:439–442. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heller I, Janssens AM, Mannik J, Minot ED, Lemay SG, Dekker C. Identifying the Mechanism of Biosensing with Carbon Nanotube Transistors. Nano Lett. 2008;8:591–595. doi: 10.1021/nl072996i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Minot ED, Janssens AM, Heller I, Heering HA, Dekker C, Lemay SG. Carbon Nanotube Biosensors: The Critical Role of the Reference Electrode. Appl Phys Lett. 2007;91:93507–93509. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ishikawa FN, Chang HK, Curreli M, Liao HI, Olson CA, Chen PC, Zhang R, Roberts RW, Sun R, Cote RJ, Thompson ME, Zhou C. Label-Free, Electrical Detection of the SARS Virus N-Protein with Nanowire Biosensors Utilizing Antibody Mimics as Capture Probes. ACS Nano. 2009;3:1219–1224. doi: 10.1021/nn900086c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bayer EA, Benhur H, Wilchek M. Isolation and Properties of Streptavidin. Methods in Enzymology. 1990;184:80–89. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)84262-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Green NM. Avidin and Streptavidin. Methods in Enzymology. 1990;184:51–67. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)84259-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bradley K, Briman M, Star A, Gruner G. Charge Transfer from Adsorbed Proteins. Nano Lett. 2004;4:253–256. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gruner G. Carbon Nanotube Transistors for Biosensing Applications. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2006;384:322–335. doi: 10.1007/s00216-005-3400-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li C, Zhang DH, Lei B, Han S, Liu XL, Zhou CW. Surface Treatment and Doping Dependence of In2o3 Nanowires as Ammonia Sensors. J Phys Chem B. 2003;107:12451–12455. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chidsey CED. Free-Energy and Temperature-Dependence of Electron-Transfer at the Metal-Electrolyte Interface. Science. 1991;251:919–922. doi: 10.1126/science.251.4996.919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stern E, Wagner R, Sigworth FJ, Breaker R, Fahmy TM, Reed MA. Importance of the Debye Screening Length on Nanowire Field Effect Transistor Sensors. Nano Lett. 2007;7:3405–3409. doi: 10.1021/nl071792z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nair PR, Alam MA. Screening-Limited Response of Nanobiosensors. Nano Lett. 2008;8:1281–1285. doi: 10.1021/nl072593i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sze SM. Semiconductor Devices: Physics and Technology. 2. Wiley; 2001. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.