Abstract

Assessment of accuracy of self-reported reason for colorectal cancer (CRC) testing has been limited. We examined the accuracy and correlates of self-reported reason (screening or diagnosis) for having a sigmoidoscopy (SIG) or colonoscopy (COL). Patients who had received at least one SIG or COL within the past five years were recruited from a large multispecialty clinic in Houston, TX, between 2005 and 2007. We calculated concordance, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, sensitivity, and specificity between self-reported reason and the medical record (gold standard). Logistic regression was performed to identify correlates of accurate self-report. Self-reported reason for testing was more accurate when the SIG or COL was done for screening, rather than diagnosis. In multivariable analysis for SIG, age was positively associated with accurately reporting reason for testing while having two or more CRC tests during the study period (compared with only one test) was negatively associated with accuracy. In multivariable analysis, none of the correlates was statistically associated with COL although a similar pattern was observed for number of tests. Determining the best way to identify those who have been tested for diagnosis, rather than screening, is an important next step.

Keywords: colorectal cancer, medical audit, validation studies

INTRODUCTION

It has become increasingly difficult to obtain medical records for research since the implementation of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) in 1996 (1). Many researchers now rely on self-report, ascertained from mail surveys or interviews, for health-related information. Self-reported health behaviors are often compared with medical or administrative records to examine accuracy. Overall, self-reported colorectal cancer (CRC) testing behaviors have been shown to be reasonably accurate (2, 3). Less is known, however, about the accuracy of self-reported reason for testing.

Qualitative studies have underscored that patients are confused about the definition of screening when asked to report the reason for a test (4). From a public health standpoint, being able to distinguish whether a test is done for screening (i.e., a test to identify “previously unrecognized disease or a disease precursor” (5, p., 336) or for diagnosis (i.e., a test to evaluate the cause of signs or symptoms or to follow-up an earlier abnormal test) is important in order to assess patients’ knowledge and understanding of the need for a CRC test and to monitor trends in screening behaviors. For example, we know from several decades of research on cancer screening adherence that a common reason given for not being screened is not having symptoms (6, 7). From a clinical perspective, it is important for patients to understand the reason for a test in order to better communicate with their healthcare provider about their medical history.

Only four published studies have examined the accuracy of self-reported reason for CRC testing (8–11). These studies were limited in the measures of agreement they assessed, and none examined correlates of accurate self-reported reason for testing. To fill this gap, we examined the accuracy and correlates of self-reported reason for CRC testing using multiple measures of agreement in a racially-diverse sample of patients from a large multispecialty clinic in Houston, TX, who had received at least one recent endoscopy: sigmoidoscopy (SIG) or colonoscopy (COL).

METHODS

We used data from a randomized controlled trial designed to evaluate the reliability and validity of a self-report questionnaire of CRC testing behaviors using three modes of survey administration: mail, phone, or face-to-face (3). Self-reported data were compared with information in the medical record and administrative databases, hereafter referred to as the combined medical record. To be eligible to participate in the trial, patients must have been English-speaking, aged 51–74 years, and have been receiving primary care at the study clinic for at least 5 years. Patients with a history of CRC were excluded. From September 2005 through August 2007, 1,040 patients were recruited for the parent study, and 857 completed a baseline questionnaire. Further details on recruitment, eligibility, and study design of the trial are described elsewhere (3).

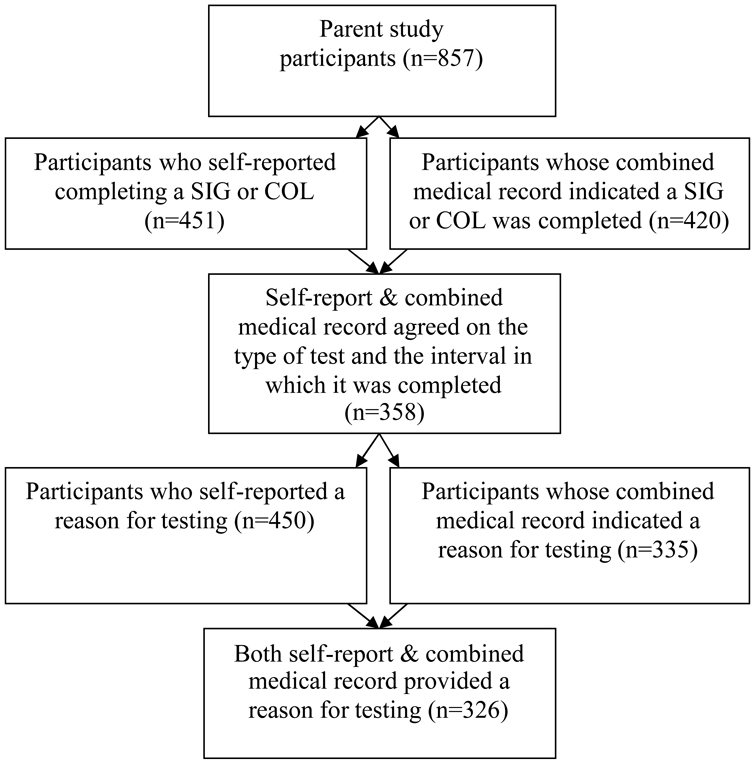

Data for this study consisted of 326 of the 857 patients who completed a baseline questionnaire (Figure 1). To be included in these analyses: 1) self-report and the combined medical record must have agreed that an endoscopy was done during the same time interval (i.e., within the past 5 years for SIG and COL), and 2) self-report and the combined medical record both provided a reason for testing. Only the most recent test was counted for patients with more than one of the same endoscopic procedures (e.g., more than one SIG during the study period). Twelve of the 326 patients in our study had received both endoscopic procedures; as such, they are included in both the SIG and COL analyses. Although a 10-year interval is recommended for COL, a 5-year interval was used in the parent study because of the difficulty identifying a sufficient number of patients who had received care at the clinic for 10+ years.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram showing how the sample of participants was chosen

Data were available for SIG (n=145) and COL (n=193). Although data were available from the parent study on barium enemas (BE) and fecal occult blood tests (FOBT), they were not evaluated in this analysis due to sample size constraints (BE) and because the reason for FOBT was not consistently recorded in the medical record. Reason for CRC testing was dichotomized as screening (part of a routine exam or checkup, or reasons unrelated to symptoms or an earlier abnormal test) or diagnostic (because of a symptom or health problem or follow-up to an earlier abnormal test).

Descriptive statistics included cross-tabulations and the following measures of agreement: concordance, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, sensitivity, and specificity. Predictive values were provided because we were interested in whether self-report was clinically useful as an accurate measure of reason for testing. Logistic regression was conducted to explore the association between concordance and the following variables: sex (female/male), age (continuous), marital status (not married/married), race/ethnicity (Non-HispanicWhite/African American/Hispanic), education (less than high school/high school/GED or some college/college degree+), and number of CRC tests that a patient had during the five-year study period (1 test/2+ tests; tests could include FOBT, BE, SIG and/or COL). Concordance with regard to reason for testing was dichotomized as agreement (coded one) between self-report and the combined medical record or as disagreement (coded zero). Measures of agreement and correlates of accurate self-reported reason for testing were calculated separately for SIG and COL. In univariable logistic regression models, we used a p-value of 0.25 to identify correlates for inclusion in multivariable analyses (12). Variables in the multivariable model were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05. SPSS Version 17 was used for all analyses.

RESULTS

The characteristics of our study sample were comparable to those of the parent study. The mean age of study participants was 58.5 years, and women comprised the majority of the sample (69%). The study sample was 59% non-Hispanic White, 25% African American, 10% Hispanic (10%), 6% other. The majority of participants reported receiving at least a college degree (57%), and most were married (78%). About 61% had received only one CRC test (i.e., FOBT, SIG, COL, or BE) during the study period.

Frequency distributions by test type are shown in Table 1; measures of agreement are shown in Table 2. Concordance between self-report and the combined medical record on reason for testing was 92% for SIG and 78% for COL. SIG and COL had high positive predictive values (97% and 80%, respectively), meaning that the majority of patients correctly reported having a SIG and/or COL for screening. Fewer patients could accurately report having a diagnostic SIG or COL, as shown by negative predictive values of 27% and 71%, respectively. Sensitivity of self-reports was >90% for SIG and COL; specificity was approximately 43% for both SIG and COL (Table 2).

Table 1.

Frequency of self-reported and combined medical record reason for colorectal cancer testing by test type

| SIG | COL | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CMR Screening |

CMR Diagnostic |

Total | CMR Screening |

CMR Diagnostic |

Total | |||

| SR Screening | 130 | 4 | 134 | SR Screening | 126 | 32 | 158 | |

| SR Diagnostic | 8 | 3 | 11 | SR Diagnostic | 10 | 25 | 35 | |

| Total | 138 | 7 | 145 | Total | 136 | 57 | 193 | |

NOTE: Abbreviations: SR= self-report, CMR= combined medical record, SIG= sigmoidoscopy, and COL=colonoscopy

Table 2.

Measures of agreement between self-reports and medical records with regards to reason for colorectal cancer testing, stratified by test type

| Concordance1 | Positive Predictive Value2 |

Negative Predictive Value3 |

Sensitivity4 | Specificity5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SIG | 91.7% | 97.0% | 27.3% | 94.2% | 42.9% |

| COL | 78.2% | 79.8% | 71.4% | 92.7% | 43.9% |

NOTE: Concordance is the proportion of patients who correctly reported receiving a CRC test for screening or for diagnosis compared with the medical record.

Positive predictive value is the number of patients correctly reporting receipt of a screening CRC test over all patients reporting receipt of screening CRC test.

Negative predictive value is the number of patients correctly reporting receipt of a diagnostic CRC test over all patients reporting receipt of a diagnostic CRC test.

Sensitivity is the number of patients correctly reporting receipt of a CRC test for screening over all patients who had a screening CRC test according to the combined medical record.

Specificity is the number of patients correctly reporting receipt of a CRC test for diagnosis over all patients who had a diagnostic CRC test according to the combined medical record.

Abbreviations: SIG= sigmoidoscopy, COL=colonoscopy

Using our criterion of p < 0.25 in univariable analysis, we identified three correlates for inclusion in multivariable analysis: age (SIG and COL models), number of tests (SIG and COL models), and race/ethnicity (COL model). Age was positively associated with accurately reporting the reason for SIG (p = 0.07) and inversely associated for COL (p = 0.19). Compared with patients who had only one SIG during the study period, patients who had a SIG plus one or more additional CRC tests (i.e., FOBT, COL, and/or BE) were less likely to accurately report the reason for having a SIG (p < 0.01). The same pattern was observed for COL (p = 0.23). Lastly, compared to non-Hispanic Whites, African Americans were more likely to accurately report the reason for having a COL (p = 0.18).

Age and number of tests were significant at p < 0.05 in the multivariable SIG model (OR = 1.20, 95% CI 1.01–1.43 and OR = 0.05, 95% CI 0.01–0.44, respectively); however, number of tests was substantially skewed. Of the 12 patients who did not accurately report the reason for SIG, eleven had two or more CRC tests. For COL, although the patterns were similar to the univariable estimates, none of the correlates were significant at the 0.05 level in multivariable analysis: age (OR = 0.97, 95% CI 0.91–1.03), number of tests (2+ compared with 1 test; OR = 0.62, 95% CI 0.30–1.28), and race/ethnicity (African Americans compared with non-Hispanic Whites; OR = 2.00, 95% CI 0.76–5.22).

DISCUSSION

Using the combined medical record as the gold standard, the majority of patients who reported getting a CRC test for screening were correct. Fewer correctly reported getting a CRC test for diagnosis, suggesting that some patients may not be informed by their healthcare provider or understand the reason for the test. Participants in our study were better able to report the reason for obtaining SIG than COL (92% vs. 78%), perhaps because COL is recommended for both screening and diagnosis, while SIG is more frequently recommended for screening. Data from the combined medical record showed that diagnostic testing is more common for COL than SIG (30% vs. 5%, respectively).

Given our relatively small sample size and because this is the first study to examine correlates of accurately reporting reason for CRC testing, the associations we observed need to be confirmed and further explored in future studies. The positive association between age and correctly reporting reason for SIG could be due to more experience with the healthcare system as one ages, thus resulting in greater awareness of one’s medical history. Our finding that having two or more CRC tests during the five-year study period decreased the likelihood of accurately reporting the reason for the most recent SIG or COL may indicate that patients become confused about the reason when they have multiple tests in a relatively short period of time.

Positive and negative predictive values, sensitivity, and specificity were not examined in any other studies, limiting our ability to compare our results with other studies. Additionally, no other studies assessed correlates of accurate self-reported CRC testing. The concordance estimates observed in our sample, specifically 92% for SIG and 78% for COL, were comparable or slightly better than the estimates found by Hall et al. (>70% for SIG), Gordon et al. (76% for SIG and COL), and Schenck et al. (65% for endoscopy) (9–11). Khoja et al. (8) did not report concordance or provide the data to calculate it.

In this paper, we aimed to answer the question: can we rely on self-reported reason for CRC testing? Based on our data, the answer is: it depends. If the goal is to identify individuals who have received a CRC test for screening, self-report is a reasonable choice. Self-report may not be a good choice, however, for clinicians who want to ascertain a patient’s CRC testing history or for researchers trying to identify individuals who received a CRC test for diagnosis.

A problem with assessing the accuracy of self-reported reason for testing is limitations of the “gold standard”, i.e., medical or administrative records. Billing codes to capture reason for testing may not be available and physicians may not record the reason for the test in the medical record, resulting in missing data. To increase accuracy and completeness, we used multiple record sources to measure reason for the test. Although it is possible that some CRC tests, particularly COL, were recorded as diagnostic for insurance purposes, this explanation is unlikely because of legislation requiring insurance providers to cover the costs of CRC screening. The 2008 Colorectal Cancer Legislation Report Card (13) found that half of all U.S. states, including Texas, have legislation in place mandating coverage of specific CRC tests for screening. In Texas, mandated coverage for CRC screening began for most health plans on January 1, 2002, prior to data collection for this study (14). Thus, it is unlikely that CRC tests were misclassified as diagnostic for insurance purposes.

Knowing the limitations of such databases, Haque et al. (15) constructed an automated data algorithm to distinguish between CRC tests obtained for screening vs. diagnosis. Similar to our findings, compared with the medical record, the algorithm missed most of the diagnostic endoscopies, but performed well for tests obtained for screening purposes. Using data algorithms to distinguish between tests obtained for screening vs. diagnosis is time consuming, and as shown by Haque et al. (15), not always accurate. Future studies should assess the accuracy of self-reported reason for testing in other populations and settings, as well as explore how the accuracy of patients’ self-reported reason for CRC testing (especially for diagnosis) could be improved through better patient-provider communication. Providing information to patients regarding why specific CRC tests are recommended/ordered may facilitate patients’ understanding of the prescribed course of action and may result in better recall of one’s CRC testing history when requested for research or clinical purposes.

Acknowledgements

We thank Anthony Greisinger and the Kelsey-Seybold Clinic staff for supporting this project. This work was supported in part by PRC SIP 19-04 U48 DP000057. Jan Eberth, Arica White, and Peter Abotchie are the recipients of National Cancer Institute Cancer Education and Career Development Predoctoral Fellowships (R25-CA057712).

REFERENCES

- 1.Shen J, Samson L, Washington E, Johnson P, Edwards C, Malone A. Barriers of HIPAA regulation to implementation of health services research. J Med Syst. 2006;30:65–69. doi: 10.1007/s10916-006-7406-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Partin MR, Grill J, Noorbaloochi S, et al. Validation of self-reported colorectal cancer screening behavior from a mixed-mode survey of veterans. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:768–776. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vernon SW, Tiro JA, Vojvodic RW, et al. Reliability and validity of a questionnaire to measure colorectal cancer screening behaviors: does mode of survey administration matter? Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:758–767. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vernon SW, Meissner H, Klabunde C, Rimer BK, Ahnen DJ, Bastani R, et al. Measures for ascertaining use of colorectal cancer screening in behavioral, health services, and epidemiologic research. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13(6):898–905. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Last JM. A dictionary for public health. New York: Oxford University Press; 2007. p. 336. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vernon SW. Participation in colorectal cancer screening: a review. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89(19):1406–1422. doi: 10.1093/jnci/89.19.1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klabunde CN, Vernon SW, Nadel MR, Breen N, Seeff LC, Brown ML. Barriers to colorectal cancer screening: a comparison of reports from primary care physicians and average-risk adults. Medical Care. 2005;43(9):939–944. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000173599.67470.ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khoja S, McGregor SE, Hilsden RJ. Validation of self-reported history of colorectal cancer screening. Can Fam Physician. 2007;53:1192–1197. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hall HI, Van Den Eeden SK, Tolsma DD, et al. Testing for prostate and colorectal cancer: comparison of self-report and medical record audit. Prev Med. 2004;39:27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gordon NP, Hiatt RA, Lampert DI. Concordance of self-reported data and medical record audit for six cancer screening procedures. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:566–570. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.7.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scheck AP, Klabunde CN, Warren JL, Peacock S, Davis WW, Hawley ST, et al. Data sources for measuring colorectal endoscopy use among Medicare enrollees. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16(10):2118–2127. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hosmer D, Lemeshow S. Applied Logistic Regression. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2000. p. 95. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Colorectal Cancer Legislation Report Card. Los Angeles, CA: National Colorectal Cancer Research Alliance; 2008. [cited 2008 November 14]. Available from: http://www.eifoundation.org/national/nccra/report_card/pdf/report_card_2008.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coverage Mandate: Colorectal Cancer Screening. Austin, TX: Texas Medical Association; 2007. [cited 2008 November 14]. Available from: http://www.texmed.org/Template.aspx?id=1719. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haque R, Chiu V, Mehta KR, Geiger AM. An automated data algorithm to distinguish screening and diagnostic colorectal cancer endoscopy exams. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2005:116–118. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgi049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]