The N domain of p97/VCP was crystallized in complex with the UBX domain of FAF1. X-ray diffraction data were collected to 2.60 Å resolution and the crystals belonged to space group C2221.

Keywords: p97, VCP, FAF1, UBX

Abstract

p97/VCP is a multifunctional AAA+-family ATPase that is involved in diverse cellular processes. p97/VCP directly interacts with various adaptors for activity in different biochemical contexts. Among these adaptors are p47 and Fas-associated factor 1 (FAF1), which contain a common UBX domain through which they bind to the N domain of p97/VCP. In the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway, p97/VCP acts as a chaperone that presents client proteins to the proteasome for degradation, while FAF1 modulates the process by interacting with ubiquitinated client proteins and also with p97/VCP. In an effort to elucidate the structural details of the interaction between p97/VCP and FAF1, the p97/VCP N domain was crystallized in complex with the FAF1 UBX domain. X-ray data were collected to 2.60 Å resolution and the crystals belonged to space group C2221, with unit-cell parameters a = 58.24, b = 72.81, c = 132.93 Å. The Matthews coefficient and solvent content were estimated to be 2.39 Å3 Da−1 and 48.4%, respectively, assuming that the asymmetric unit contained p97/VCP N domain and FAF1 molecules in a 1:1 ratio, which was subsequently confirmed by molecular-replacement calculations.

1. Introduction

p97/VCP (valosin-containing protein) is a multifunctional ATPase that belongs to the AAA+ family (ATPases associated with various cellular activities). p97/VCP has been shown to be involved in diverse cellular processes such as nuclear envelope reconstruction, the cell cycle, post-mitotic Golgi reassembly, suppression of apoptosis, DNA damage response and endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation (ERAD; Vij, 2008 ▶). The proteins of the AAA+ family have been classified into two subgroups, type I and type II, on the basis of the number of ATPase domains that they include. The type II proteins contain two ATPase domains, referred to as the D1 and D2 domains, while the type I proteins contain only one ATPase domain, termed D2. In addition to the ATPase domains, less conserved domains are often found at the N-terminus (N domain) or the C-terminus and are implicated in adaptor binding (Dougan et al., 2002 ▶). p97/VCP belongs to the type II subgroup and contains an N domain, a D1 domain and a D2 domain.

p97/VCP directly interacts with various adaptor proteins in different biochemical contexts (Vij, 2008 ▶). Among these adaptor proteins are p47 and FAF1 (Fas-associated factor 1), which contain a common UBX domain through which they bind to the N domain of p97/VCP (Song et al., 2005 ▶; Yuan et al., 2001 ▶). p47 is an essential adaptor for p97-mediated membrane fusion (Kondo et al., 1997 ▶) and FAF1 is involved in the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway (Song et al., 2005 ▶). FAF1 was initially identified as a Fas-associating protein that potentiates Fas-mediated apoptosis (Chu et al., 1995 ▶). Subsequently, FAF1 was also shown to suppress NF-κB signalling (Park et al., 2004 ▶, 2007 ▶) and to modulate protein degradation in the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway (Song et al., 2005 ▶). In the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway, p97/VCP acts as a chaperone that presents client proteins to the proteasome for degradation, while FAF1 modulates the process by interacting with ubiquitinated client proteins through its UBA domain and also with p97/VCP through its UBX domain (Song et al., 2005 ▶; Vij, 2008 ▶). In an effort to elucidate the structural details of the interaction between p97/VCP and FAF1, we have crystallized the p97/VCP N domain in complex with the FAF1 UBX domain.

2. Experimental procedures

2.1. Protein overproduction and purification

The gene region encoding the human p97/VCP N domain (residues 21–196) was amplified by polymerase chain reaction from its cDNA (KRIBB, Republic of Korea) and ligated into a modified pET vector (a gift from Dr K. K. Kim, Sungkyunkwan University, Republic of Korea). The nucleotide sequence of the insert was confirmed by sequencing. The constructed expression vector was designed to produce the p97/VCP N domain fused to His-tagged thioredoxin, which can be cleaved off by TEV protease. The overproduced fusion protein thus contains the following sequences from the N-terminus: (hexahistidine tag)–(thioredoxin)–(TEV recognition site, ENLYFQG)–(p97/VCP N domain, residues 21–196). After TEV protease cleavage, the extra sequence Gly-Ser, which was translated from a BamHI site, remained attached to the N-terminal end of the p97/VCP N domain (residues 21–196). Escherichia coli strain Rosetta2 (DE3) cells were transformed with the expression vector and were cultured with shaking at 310 K in Luria–Bertani medium containing 30 µg ml−1 kanamycin. When the OD600 reached 0.6, the culture was cooled to 298 K and protein overproduction was induced by adding isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) to a final concentration of 0.5 mM. Cells were incubated at 298 K for an additional 16 h after IPTG induction and were then harvested by centrifugation at 5000 rev min−1 for 30 min (Hanil Supra 22K with rotor 11, Republic of Korea). The human FAF1 UBX domain (residues 571–650) was cloned and overproduced in the same manner, except that Gly-Ser-Glu-Phe remained attached to the N-terminal end after TEV protease cleavage.

The harvested cells were resuspended in working buffer [20 mM Tris–HCl, 5%(v/v) glycerol, 0.1 mM TCEP, 100 mM sodium chloride pH 8.0] containing 10 mM imidazole and 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. The resuspended cells were lysed by sonication with a VCX500 ultrasonic processor (Sonics & Materials, USA) and the cell lysate was centrifuged at 15 000 rev min−1 for 30 min (Hanil Supra 22K with rotor 7, Republic of Korea). The supernatant was filtered through a membrane filter with 0.45 µm pore size (Advantec, Japan). The sample was then loaded onto a HisTrap column (GE Healthcare Bioscience, USA) and the bound protein was eluted with a 0–0.5 M imidazole gradient. The eluted sample was passed through a HiPrep desalting column (GE Healthcare Bioscience, USA) to remove imidazole and was then treated with TEV protease (van den Berg et al., 2006 ▶) in a 1:100 molar ratio at 293 K overnight. The sample was again loaded onto a HisTrap column to retain the cleaved fusion partner containing the His tag. The unbound flowthrough was collected and concentrated by centrifugal ultrafiltration (Amicon Ultra, Millipore, USA). Gel filtration was then performed on a Superdex 200 column (GE Healthcare Bioscience, USA) pre-equilibrated with working buffer. The purity of the protein was judged by SDS–PAGE. Both the p97/VCP N domain and the FAF1 UBX domain were purified using the protocol described above. The separately purified FAF1 UBX and p97/VCP N domains were mixed in a 1:1 ratio and concentrated to 27 mg ml−1. The concentrated sample was aliquoted and stored at 203 K. The protein concentration was determined by measuring the absorbance at 280 nm, employing a calculated extinction coefficient of 0.50 mg−1 ml cm−1 (http://www.expasy.org).

2.2. Crystallization and X-ray data collection

Crystallization conditions were initially screened using commercial screening kits from Hampton Research, Emerald BioSystems and Qiagen. Crystals were grown by the hanging-drop vapour-diffusion method. 2 µl protein solution was mixed with an equal volume of reservoir solution and the mixture was equilibrated against 0.5 ml reservoir solution at 295 K. Refinement of the reservoir-solution composition was carried out by varying the concentrations of the component chemicals. Crystals were soaked for 1–2 s in a 10 µl droplet of a cryoprotective solution, which consisted of well solution with an additional 10%(v/v) glycerol, and were then flash-cooled in liquid nitrogen before data collection.

X-ray diffraction data were collected at 100 K on beamline 6C1 of Pohang Light Source, Republic of Korea. The intensity data were processed, merged and scaled with the HKL-2000 program suite (Otwinowski & Minor, 1997 ▶).

3. Results and discussion

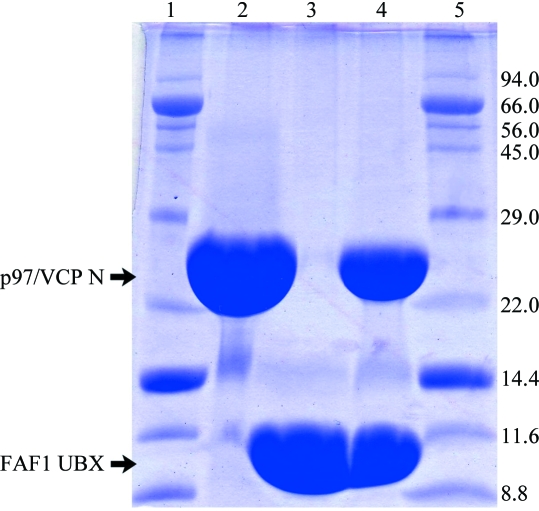

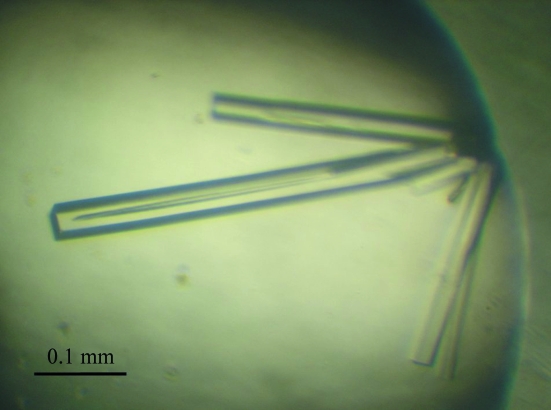

The human p97/VCP N domain and the FAF1 UBX domain were separately overproduced in E. coli and purified. The purity of each protein sample was >95% as judged by SDS–PAGE (Fig. 1 ▶). The two proteins were mixed in a 1:1 ratio and the complex was concentrated to 27 mg ml−1 and subjected to initial crystallization trials using commercial screening kits. Rod-shaped crystals of 200–500 µm in the longest dimension grew in two months using condition No. 85 of the Qiagen Classic Suite II (Fig. 2 ▶). The crystals were reproduced using the seeding technique with a reservoir solution of the same composition. The microseeding procedure increased the crystal reproducibilty and shortened the time required for crystallization to less than one week. The refined composition of the reservoir solution was 25%(m/v) polyethylene glycol 3350, 0.2 M magnesium chloride and 0.1 M Tris–HCl pH 8.5.

Figure 1.

Purified samples of the human p97/VCP N domain and the FAF1 UBX domain. The purified p97/VCP N domain is in lane 2, the FAF1 UBX domain is in lane 3 and the mixture used for crystallization is in lane 4. Size markers are in lanes 1 and 5. Molecular masses are given in kDa.

Figure 2.

Crystals of the human p97/VCP N domain complexed with the FAF1 UBX domain.

The crystals diffracted to 2.60 Å resolution on beamline 6C1 at Pohang Light Source, Republic of Korea. The crystals belonged to the C-centred orthorhombic system, with unit-cell parameters a = 58.24, b = 72.81, c = 132.93 Å. Systematic absences of reflections were not clear enough to distinguish between C222 and C2221 as the correct space group, but subsequent molecular-replacement calculations gave a solution with the choice of space group C2221. If one 1:1 complex between the p97/VCP N domain and the FAF1 UBX domain was assumed to be present in the asymmetric unit, the Matthews coefficient was 2.39 Å3 Da−1 and the corresponding solvent content was 48.4% (Matthews, 1968 ▶). The diffraction data set containing 9050 unique reflections is 99.1% complete with a redundancy of 5.9 and an R merge of 5.0%. Table 1 ▶ summarizes the data-collection statistics.

Table 1. Summary of data-collection statistics.

Values in parentheses are for the highest resolution shell.

| Space group | C2221 |

| Unit-cell parameters (Å) | a = 58.24, b = 72.81, c = 132.92 |

| Resolution (Å) | 50.00–2.60 (2.69–2.60) |

| No. of measured reflections | 53406 |

| No. of unique reflections | 9050 |

| Rmerge† (%) | 5.0 (30.0) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.1 (97.1) |

| 〈I/σ(I)〉 | 26.3 (4.2) |

| Redundancy | 5.9 (5.5) |

R

merge =

, where I(hkl) is the intensity of reflection hkl,

, where I(hkl) is the intensity of reflection hkl,  is the sum over all reflections and

is the sum over all reflections and  is the sum over i measurements of reflection hkl.

is the sum over i measurements of reflection hkl.

Structure solution was attempted using molecular replacement with Phaser in the CCP4 program suite (Collaborative Computational Project, Number 4, 1994 ▶; McCoy et al., 2007 ▶). Two search models were used for the two domains: the p97/VCP N domain part (residues 23–196) was taken from the crystal structure of p97/VCP ND1 in complex with p47 UBX (PDB code 1s3s; Dreveny et al., 2004 ▶) and an NMR structure of the FAF1 UBX domain (residues 571–650; PDB code 1h8c; Buchberger et al., 2001 ▶) was used. Both domains were successfully located in the asymmetric unit and the correct space group was proven to be C2221 rather than C222. Model building and structure refinement are under way.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the Korea Healthcare Technology R&D Project, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (A080930). The authors thank the staff of Pohang Light Source beamline 6C1.

References

- Berg, S. van den, Lofdahl, P. A., Hard, T. & Berglund, H. (2006). J. Biotechnol.121, 291–298. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Buchberger, A., Howard, M. J., Proctor, M. & Bycroft, M. (2001). J. Mol. Biol.307, 17–24. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Chu, K., Niu, X. & Williams, L. T. (1995). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 92, 11894–11898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Collaborative Computational Project, Number 4 (1994). Acta Cryst. D50, 760–763.

- Dougan, D. A., Mogk, A., Zeth, K., Turgay, K. & Bukau, B. (2002). FEBS Lett.529, 6–10. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Dreveny, I., Kondo, H., Uchiyama, K., Shaw, A., Zhang, X. & Freemont, P. S. (2004). EMBO J.23, 1030–1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kondo, H., Rabouille, C., Newman, R., Levine, T. P., Pappin, D., Freemont, P. & Warren, G. (1997). Nature (London), 388, 75–78. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Matthews, B. W. (1968). J. Mol. Biol.33, 491–497. [DOI] [PubMed]

- McCoy, A. J., Grosse-Kunstleve, R. W., Adams, P. D., Winn, M. D., Storoni, L. C. & Read, R. J. (2007). J. Appl. Cryst.40, 658–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Otwinowski, Z. & Minor, W. (1997). Methods Enzymol.276, 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Park, M. Y., Jang, H. D., Lee, S. Y., Lee, K. J. & Kim, E. (2004). J. Biol. Chem.279, 2544–2549. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Park, M. Y., Moon, J. H., Lee, K. S., Choi, H. I., Chung, J., Hong, H. J. & Kim, E. (2007). J. Biol. Chem.282, 27572–27577. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Song, E. J., Yim, S. H., Kim, E., Kim, N. S. & Lee, K. J. (2005). Mol. Cell. Biol.25, 2511–2524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Vij, N. (2008). J. Cell. Mol. Med.12, 2511–2518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Yuan, X., Shaw, A., Zhang, X., Kondo, H., Lally, J., Freemont, P. S. & Matthews, S. (2001). J. Mol. Biol.311, 255–263. [DOI] [PubMed]