Abstract

Objective:

Individuals visiting a primary care practice were screened to determine the prevalence of depressive disorders. The DSM-IV-TR research criteria for minor depressive disorder were used to standardize a definition for subthreshold symptoms.

Method:

Outpatients waiting to see their physicians at 3 community family medicine sites were invited to complete a demographic survey and the Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders Patient Questionnaire (PRIME-MD PQ). Those who screened positive for depression on the PRIME-MD PQ were administered both the PRIME-MD Clinician Evaluation Guide (CEG) mood module and the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) by telephone. Data were collected over a 2-year period (1996–1998).

Results:

1,752 individuals completed the PRIME-MD PQ with 478 (27.3%) scoring positive for depression. Of these 478 patients, 321 received telephone follow-up using the PRIME-MD CEG mood module and the HDRS. PRIME-MD diagnoses were major depressive disorder (n = 85, 26.5%), dysthymia (n = 31, 9.6%), minor depressive disorder (n = 51, 15.9%), and no depression diagnosis (n = 154, 48.0%). The mean HDRS scores by diagnosis were major depressive disorder (20.3), dysthymia (12.9), minor depressive disorder (11.7), and no depression diagnosis (5.8). Post hoc analyses using Dunnett's C test indicated differences between each of the 4 groups at P ≤ .05, with the exception that dysthymia and minor depressive disorder were not significantly different.

Conclusions:

Minor depressive disorder was more prevalent than dysthymia and had similar symptom severity to dysthymia as measured by the HDRS. More research using standardized definitions and longitudinal studies is needed to clarify the natural course and treatment indications for minor depressive disorder.

An evolving concept of depressive symptoms as being fluid and changing over the course of time rather than being a static state has led to focused study of subthreshold depression.1 In response to reports of family physicians’ missing 30%–50% of cases of depression, some family physicians believe they are seeing milder, more transient forms of subthreshold depression that require neither identification nor treatment.2 However, other authors have reported that subthreshold depression is associated with significant morbidity.3

In the classic study by Wells et al4 of over 20,000 individuals in medical and mental health outpatient settings, depressive symptoms alone in patients without major depressive disorder or dysthymia were associated with significant social dysfunction and disability. Horwath et al5 found that subthreshold symptoms were predictive of first onset of major depressive disorder in 50% of cases 1 year later. Lin's group6 identified the persistence of subthreshold depressive symptoms 7 months after starting antidepressant therapy as a major risk for relapse of major depressive disorder. A growing body of literature suggests that subthreshold depressive symptoms are a variant of mood dysfunction that should be considered for possible preventive and treatment strategies.7–9 However, empirical evidence has yielded mixed results for the effectiveness of treating subthreshold depression.10,11

The conflicting findings surrounding subthreshold depression may be partially explained by the heterogeneity of the condition being studied; many different definitions of subthreshold depression have been used in the past.12 To standardize the assessment of subthreshold depression, the DSM-IV-TR13 has published research criteria for the proposed diagnosis of minor depressive disorder. Rapaport's group14 studied the general population and found a point prevalence rate of 2%–5% for minor depression, while others15 estimate a 5% prevalence of minor depression in the general population. Rates of minor depression in primary care have been reported to be as low as 4.5% and as high as 17%.16 More studies using the standardized definition of minor depressive disorder are needed to clarify the prevalence and severity of this disorder among individuals in primary care settings.

This study explores the prevalence of depression, including minor depressive disorder as defined by DSM-IV-TR research criteria (Table 1), in primary care populations. This is accomplished by using the Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders (PRIME-MD)17 to identify depressive symptoms and diagnoses and the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS)18,19 to assess symptom severity.

Table 1.

DSM-IV-TR Criteria for Minor Depressive Disordera

| • At least 2 (but less than 5) of the symptoms in Criterion A for a major depressive episode have been present during the same 2-week period and represent a change from previous functioning |

| • At least 1 of the symptoms is either: |

| Depressed mood most of the day, nearly every day, or |

| Markedly diminished interest or pleasure in all, or almost all, activities most of the day, nearly every day |

| • There has never been a major depressive episode, and criteria are not met for dysthymic disorder |

| • There has never been a manic episode, a mixed episode, or a hypomanic episode, and criteria are not met for cyclothymic disorder |

Adapted with permission from the American Psychiatric Association.13

Clinical Points

♦ Minor depressive disorder is relatively common among primary care patients, especially the elderly.

♦ Treatment guidelines emphasize the importance of treating depressive symptoms to full remission.

METHOD

Outpatients waiting to see their primary care physicians at 3 community family medicine sites were invited to participate in this study. The first practice was in a rural setting and served patients who were primarily from the lower middle class. The second practice was in an urban setting, and the third practice was in a suburban setting. These latter 2 practices served patients who were in the lower to upper middle classes. Participants were excluded if they were under 18 years of age or unable to read and speak English. Institutional review board approval from the participating institutions was obtained. After consenting to participate, subjects completed a demographic survey and the PRIME-MD Patient Questionnaire (PQ)17 in the waiting room. The demographic survey had questions about age, gender, education, race, smoking (“how many cigarettes do you smoke per day?”), and drinking (“how many alcoholic drinks do you have per week?”). Data were collected over a 2-year period (1996–1998).

The PRIME-MD PQ is a self-administered 1-page questionnaire consisting of 26 yes/no questions about the presence of symptoms and signs during the past month. The questionnaire serves as an initial screen for 5 general groups of mental disorders commonly found in the general population. The 2 screening questions for depression on the PRIME-MD PQ are (question 18) “During the past month, have you often been bothered by having little interest or pleasure in doing things?” and (question 19) “During the past month, have you often been bothered by feeling down, depressed, or hopeless?”

The PRIME-MD Clinician Evaluation Guide (CEG) is a structured interview form with 5 modules, with completion of each one triggered by positive responses to specific screening questions on the PRIME-MD PQ. Individuals who screened positive for depression upon completing the PRIME-MD PQ in this study were contacted by telephone and administered the CEG mood module and the HDRS. The 17 questions on the PRIME-MD CEG mood module allow the clinician to reach DSM-IV-TR depression diagnoses. Although the initial prompt on the CEG explores symptoms experienced during the preceding 2 weeks, the algorithm also includes questions about the longitudinal course of symptoms that can result in diagnoses such as dysthymia. The CEG diagnoses for the mood disorders module have been shown to have excellent positive predictive value with satisfactory specificity and sensitivity.20

The HDRS19 is a 17-item questionnaire. Scores of 0–10 suggest no depression, scores of 11–17 are indicative of mild depression, and a rating of 18–24 suggests moderate depression.

The CEG and HDRS were administered by a team of 2 paid research assistants who were trained and supervised by the fourth author (M.K.S.), an experienced psychiatrist. Training activities included observation by the assistants of the trainer doing a telephone interview and role playing the interview with each other and the supervisor, as well as being observed and monitored by the trainer. Research assistants were allowed to do the telephone interviews on their own only when the supervising psychiatrist judged them to be ready.

RESULTS

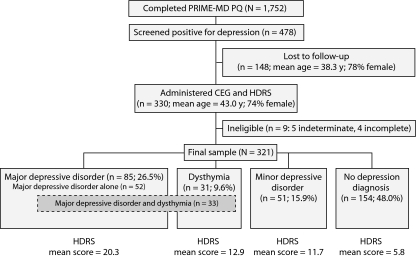

The PRIME-MD PQ was completed by 1,752 patients, with 478 (27.3%) of these individuals screening positive for depression. Eighty percent of the individuals who were approached to complete the PRIME-MD PQ while waiting to see their physicians agreed to participate in this phase of the study. The sample of 1,752 subjects was primarily female (71.1%) and employed full-time (53.7%), with a mean age of 42.7 years. Figure 1 represents the flow of subjects through the study and their final classification based on PRIME-MD PQ responses.

Figure 1.

Flow of Study Participants Through Screening With the PRIME-MD PQ and Telephone Assessment With the PRIME-MD CEG Mood Module and the HDRS

Abbreviations: HDRS = Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, PQ = Patient Questionnaire, PRIME-MD CEG = Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders Clinician Evaluation Guide.

Of the 478 individuals who screened positive for depression, 330 (69%) were able to be contacted by telephone and received telephone follow-up with the CEG mood module and the HDRS. However, of these 330 participants, 5 had a PRIME-MD depression diagnosis that was indeterminate and 4 had missing HDRS scores, resulting in a final sample of 321 subjects (67.1%). There were no significant differences between the 330 individuals contacted by telephone and the 148 positive screening nonparticipants in their gender (χ2 = 0.73, P > .39; 74% of those screened positive for depression were female), employment status (χ2 = 1.39, P > .23; 70.8% of those who screened positive were employed), or age (χ2 = 3.07, P = .08; 13% of those who screened positive were aged 60 years or older). No individuals who screened negative for depression were contacted by telephone for follow-up with the CEG and HDRS.

Among the final sample, 52 individuals met criteria for major depressive disorder only, and an additional 33 met criteria for both major depressive disorder and dysthymia. For purposes of analysis and discussion, the latter group was included in the major depressive disorder category.

There was a difference in mean HDRS scores corresponding to the CEG mood module diagnoses in the final sample (F = 98.91, P < .001). Post hoc analysis indicated that the only mean HDRS group scores that were not significantly different were for those individuals with dysthymia and minor depressive disorder (Table 2). Applying the rate of 15.9% for minor depressive disorder found in the 321 subjects who completed the study to the 148 subjects who screened positive for depression but were lost to follow-up yields the estimate that a total of 76 individuals in the original sample of 1,752 would have been diagnosed with minor depressive disorder. Thus, from these results, one can extrapolate a base rate of 4.3% in the general population.

Table 2.

PRIME-MD CEG Mood Module Diagnoses and HDRS Scores for 321 Primary Care Outpatients

| HDRS Scorea |

||||

| Diagnosis | n | % | Mean | SD |

| Major depressive disorder | 85 | 26.5 | 20.3 | 7.1 |

| Dysthymic disorder | 31 | 9.6 | 12.9 | 7.1 |

| Minor depressive disorder | 51 | 15.9 | 11.7 | 5.1 |

| No depression diagnosis | 154 | 48.0 | 5.8 | 4.7 |

F = 117.22, P < .001. Post hoc analyses using Dunnett's C test indicated that each of the 4 groups was significantly different at P ≤ .05, except for dysthymia and minor depressive disorder.

Abbreviations: HDRS = Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, PRIME-MD CEG = Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders Clinician Evaluation Guide.

Because we did not have information about those who did not participate in the CEG telephone screening, a weighting strategy using gender, age, and employment status of those screening positive was used to estimate the rate of depression in the entire positively screened sample.21,22 This analysis resulted in a rate of 15.3% for minor depressive disorder (compared to the 15.9% found with the unweighted data). Applying the rate of 15.3% for minor depressive disorder in those who screened positive for depression yields an estimate of a total of 73 individuals in the original sample of 1,752 who would have been diagnosed with minor depressive disorder. Thus, from these results, one can extrapolate a base rate of 4.2% in the general population.

There were significant differences among the 4 CEG mood module diagnostic categories of major depressive disorder, dysthymia, minor depressive disorder, and no depression diagnosis when the variables of age, smoking, and perceived stress were examined. Comparing individuals younger than 60 years old (n = 270) to subjects 60 years or older (n = 44), there were differences in depression categories (χ2 = 11.89, P < .008). The older group had more minor depressive disorder (31.8% vs 13.3%) and less major depressive disorder (13.6% vs 28.9%) when compared to subjects less than 60 years of age. When smokers and nonsmokers were compared in the 4 diagnostic categories, there was a difference between groups (χ2 = 18.67, P < .001), with 50.0% of individuals with major depressive disorder, 32.3% with dysthymia, 25.5% with minor depressive disorder, and 23.3% with no depression diagnosis who smoked.

There were no significant differences among the 4 CEG depression categories in the percentage of those employed (χ2 = 2.83, P > .41; 70.2% of the total group were employed), gender (χ2 = 2.71, P > .43; 76% of the total group were female), or the use of alcohol (χ2 = 7.32, P > .07; 33.5% of the total group were alcohol drinkers).

The analysis for experiencing stress over the last 4 weeks (a 5-point scale from 1 = none to 5 = severe) indicated a difference in stress between groups with 1-way analysis of variance (F = 10.45, P < .001). Post hoc tests indicated that the major depressive disorder group (mean = 4.38) experienced more stress than either those with minor depressive disorder (mean = 3.76) or no depression diagnosis (mean = 3.70). The group with dysthymia (mean = 4.07) was not significantly different from any of the other 3 groups. There were no significant differences across diagnostic categories for variables of gender, employment status, or alcohol use.

DISCUSSION

Using DSM-IV-TR research criteria in this study, minor depressive disorder appears to be a significant disorder in terms of both its frequency—11/2 times more prevalent than dysthymia alone—and its severity as measured by the HDRS. The extrapolated prevalence of 4.2% is at the lower end of the range reported in earlier studies.3,16,23 However, because our study design did not include follow-up interviews of anyone who screened negative for depression by the PRIME-MD PQ, this calculation may underestimate the prevalence of minor depressive disorder because false negatives were not included in the estimate.

When comparing prevalence rates of minor depressive disorder, it may also be important to consider the age distribution of the population. This study's finding of significantly more minor depressive disorder (31.8%) and less major depressive disorder (13.6%) among elderly individuals who screened positive for depression has been reported previously.24,25 Bruce et al26 outlined a successful treatment intervention for older individuals with major depression and minor depression accompanied by suicidal ideation. This is important, given the fact that suicide completion rates are highest in late life; the elderly should be carefully screened and monitored for depression.

The current study is limited by the final return rate of 67.1% due to the difficulty in reaching individuals by telephone to administer the CEG and HDRS. A limitation of the PRIME-MD in this study was that initial screening with the PRIME-MD PQ yielded a false-positive rate for depression of nearly 50%. However, previous studies using the same 2 PRIME-MD PQ questions to screen for depression have demonstrated a positive predictive value for major depression of 33% when used in written form27 and 18% when verbally administered.28 (The positive predictive value for major depressive disorder only in this study was 26.5%.) The positive predictive value (for PRIME-MD PQ questions 18 and 19) for combined major depression, dysthymia, and minor depression in these 2 previous studies27,28 was not reported. Arroll and colleagues28 defended the use of a depression screening instrument with a low positive predictive value (18%) in a “low prevalence” setting because of the ability a physician has to gather further data (the reference standard) or refer the individual to another health professional.

Another potentially useful technique to screen for depression in primary care settings may be to ask individuals a single question about their perceived level of stress over the preceding 4 weeks. Additional research would be needed to establish an appropriate threshold to identify individuals with dysthymia and minor depressive disorder as well as those with major depressive disorder. Physicians may also want to more closely monitor depression in individuals who smoke cigarettes, given the association between depression and smoking. Knowing an individual's longitudinal course of depressive symptoms and current symptomatology could potentially facilitate more effective interventions in health behaviors such as smoking.

The current model of the minor depressive disorder group was indicative of mild depression and, interestingly, was very similar to the mean HDRS score of the group with dysthymia. This finding of similar symptom severity between minor depressive disorder and dysthymia is consistent with the report of Rucci et al29 that individuals with subthreshold depression experience significant psychological distress and disability that mirrors the lower quality-of-life indices seen in dysthymia.

The current longitudinal model used to understand major depressive disorder is one of fluidity, with phases of subthreshold symptoms and minor depressive episodes punctuating relatively symptom-free periods. Because of the cumulative effects of untreated depression, treatment guidelines stress the importance of treating depressive symptoms to remission when they occur.30

The present study suggests that minor depressive disorder is relatively common among primary care patients, especially the elderly. Because of the psychological distress associated with minor depressive disorder, it is important to identify and follow such individuals with a “watchful eye.” Among the more medically frail older population, coexisting depressive symptoms may also interfere with adherence to treatment recommendations for a variety of medical illnesses. Identification of minor depressive disorder in this population is important for primary care physicians to pursue. Gilbody et al31 in a recent review caution that depression screening cannot stand alone, but needs to be part of a comprehensive system-based approach, including careful patient follow-up and use of well-trained case managers.

Potential conflicts of interest: None reported.

Funding/support: Support for this research was received from the Ohio Academy of Family Physicians Foundation, Columbus, Ohio.

Previous presentation: Parts of this study were presented at the 28th Annual Meeting of the North American Primary Care Research Group, November 4–7, 2000, Amelia Island, Florida.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the help of Sadik Khuder, PhD (College of Medicine, University of Toledo, Ohio), in data analysis and Carol Brikmanis, MA (Department of Psychiatry, University of Toledo, Ohio), in preparing this article. Dr Khuder and Ms Brikmanis report no financial or other relationships relevant to the subject of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Forsell Y. A three-year follow-up of major depression, dysthymia, minor depression and subsyndromal depression: results from a population-based study. Depress Anxiety. 2007;24(1):62–65. doi: 10.1002/da.20231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hegel MT, Oxman TE, Hull JG, et al. Watchful waiting for minor depression in primary care: remission rates and predictors of improvement. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28(3):205–212. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2006.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lavretsky H, Kurbanyan K, Kumar A. The significance of subsyndromal depression in geriatrics. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2004;6(1):25–31. doi: 10.1007/s11920-004-0034-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wells KB, Stewart A, Hays RD, et al. The functioning and well-being of depressed patients: results from the Medical Outcomes Study. JAMA. 1989;262(7):914–919. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Horwath E, Johnson J, Klerman GL, et al. Depressive symptoms as relative and attributable risk factors for first-onset major depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49(10):817–823. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820100061011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin EH, Katon WJ, VonKorff M, et al. Relapse of depression in primary care: rate and clinical predictors. Arch Fam Med. 1998;7(5):443–449. doi: 10.1001/archfami.7.5.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.da Silva Lima AF, de Almeida Fleck MP. Subsyndromal depression: an impact on quality of life? J Affect Disord. 2007;100(1-3):163–169. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kessler RC, Zhao S, Blazer DG, et al. Prevalence, correlates, and course of minor depression and major depression in the National Comorbidity Survey. J Affect Disord. 1997;45(1-2):19–30. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(97)00056-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pincus HA, Davis WW, McQueen LE. ‘Subthreshold’ mental disorders: a review and synthesis of studies on minor depression and other ‘brand names’. Br J Psychiatry. 1999;174:288–296. doi: 10.1192/bjp.174.4.288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fortney J, Rost K, Zhang M, et al. The relationship between quality and outcomes in routine depression care. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52(1):56–62. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wells K, Sherbourne C, Duan N, et al. Quality improvement for depression in primary care: do patients with subthreshold depression benefit in the long run? Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(6):1149–1157. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.6.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sadek N, Bona J. Subsyndromal symptomatic depression: a new concept. Depress Anxiety. 2000;12(1):30–39. doi: 10.1002/1520-6394(2000)12:1<30::AID-DA4>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fourth Edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. Text Revision. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rapaport MH, Judd LL, Schettler PJ, et al. A descriptive analysis of minor depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(4):637–643. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.4.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sadock BJ, Sadock VA. Kaplan & Sadock's Synopsis of Psychiatry: Behavioral Sciences/Clinical Psychiatry. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fogel J, Eaton WW, Ford DE. Minor depression as a predictor of the first onset of major depressive disorder over a 15-year follow-up. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;113(1):36–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00654.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Kroenke K, et al. Utility of a new procedure for diagnosing mental disorders in primary care: the PRIME-MD 1000 study. JAMA. 1994;272(22):1749–1756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hamilton M. Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. Br J Soc Clin Psychol. 1967;6(4):278–296. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1967.tb00530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boyer P, Bisserbe J-C, Weiller E. How efficient is a screener? a comparison of the PRIME-MD patient questionnaire with the SDDS-PC screen. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 1998;7(1):27–32. [Google Scholar]

- 21.An A, Watts D. Nashville, TN: 1998. New SAS Procedures for Analysis of Sample Survey Data. Presented at the 23rd annual meeting of the SAS Users Group International Conference. March 22–25. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dunn G, Pickles A, Tansella M, et al. Two-phase epidemiological surveys in psychiatric research. Br J Psychiatry. 1999;174:95–100. doi: 10.1192/bjp.174.2.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Backenstrass M, Frank A, Joest K, et al. A comparative study of nonspecific depressive symptoms and minor depression regarding functional impairment and associated characteristics in primary care. Compr Psychiatry. 2006;47(1):35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2005.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lynch D, McGinnis R, Nagel R, et al. Depression and associated physical symptoms: comparison of geriatric and non-geriatric family practice patients. J Ment Health Aging. 2002;8(1):29–35. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xavier FMF, Ferraza MPT, Argimon I, et al. The DSM-IV ‘minor depression’ disorder in the oldest-old: prevalence rate, sleep patterns, memory function and quality of life in elderly people of Italian descent in Southern Brazil. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;17(2):107–116. doi: 10.1002/gps.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bruce ML, Ten Have TR, Reynolds CF, 3rd, et al. Reducing suicidal ideation and depressive symptoms in depressed older primary care patients: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291(9):1081–1091. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.9.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Whooley MA, Avins AL, Miranda J, et al. Case-finding instruments for depression: two questions are as good as many. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12(7):439–445. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.00076.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arroll B, Khin N, Kerse N. Screening for depression in primary care with two verbally asked questions: cross sectional study. BMJ. 2003;327(7424):1144–1146. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7424.1144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rucci P, Gherardi S, Tansella M, et al. Subthreshold psychiatric disorders in primary care: prevalence and associated characteristics. J Affect Disord. 2003;76(1-3):171–181. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00087-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Judd LL, Marston MG. Major Depressive Disorder (MDD): A New Paradigm. Pennsylvania, PA: University of Pennsylvania; 2007. pp. 1–17. Strecker Monograph. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gilbody S, Sheldon T, House A. Screening and case-finding instruments for depression: a meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2008;178(8):997–1003. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.070281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]