Abstract

Background

Benign biliary strictures may be a consequence of surgical procedures, chronic pancreatitis or iatrogenic injuries to the ampulla. Stents are increasingly being used for this indication, however it is not completely clear which stent type should be preferred.

Methods

A systematic review on stent placement for benign extrahepatic biliary strictures was performed after searching PubMed and EMBASE databases. Data were pooled and evaluated for technical success, clinical success and complications.

Results

In total, 47 studies (1116 patients) on outcome of stent placement were identified. No randomized controlled trials (RCTs), one non-randomized comparative studies and 46 case series were found. Technical success was 98,9% for uncovered self-expandable metal stents (uSEMS), 94,8% for single plastic stents and 94,0% for multiple plastic stents. Overall clinical success rate was highest for placement of multiple plastic stents (94,3%) followed by uSEMS (79,5%) and single plastic stents (59.6%). Complications occurred more frequently with uSEMS (39.5%) compared with single plastic stents (36.0%) and multiple plastic stents (20,3%).

Conclusion

Based on clinical success and risk of complications, placement of multiple plastic stents is currently the best choice. The evolving role of cSEMS placement as a more patient friendly and cost effective treatment for benign biliary strictures needs further elucidation. There is a need for RCTs comparing different stent types for this indication.

Background

Benign biliary strictures occur most frequently as a consequence of a surgical procedure of the gallbladder, mainly cholecystectomy, or common bile duct (CBD) [1]. Other causes include inflammatory conditions, such as chronic pancreatitis and sclerosing cholangitis [2]. In addition, cholelithiasis, sphincterotomy and infections of the biliary tract may also lead to a stricture [3]. Benign strictures of the biliary tract are associated with a broad spectrum of signs and symptoms, ranging from subclinical disease with mild elevation of liver enzymes to complete obstruction with jaundice, pruritus and cholangitis, and ultimately biliary cirrhosis [4].

A bilio-digestive anastomosis, or a percutaneously or endoscopically performed dilation with or without stent placement are the most commonly used treatment options for benign biliary strictures[5]. Stent placement in the CBD is an increasingly being used alternative to surgery. Several reports on the nonsurgical management of benign biliary strictures with stents have shown results which are equal to those obtained by surgery [6-12]. The endoscopic management typically consists of dilation and insertion of one or more plastic stents followed by elective stent exchange every 3 months to avoid cholangitis caused by stent clogging [4,13]. An increasing number of plastic stents will progressively dilate a stricture in the CBD or the papilla. The major disadvantages of this method are the need for multiple invasive procedures and the morbidity caused by stent dysfunction resulting in recurrent jaundice and cholangitis.

In malignant biliary strictures, uncovered self-expanding metal stents (uSEMS) have been shown to have a longer stent patency than plastic stents, mainly because of their larger diameter [4,14]. Nonetheless, long-term stent patency is a limiting factor with uSEMS as well, as these devices may obstruct due to epithelial hyperplasia and tissue ingrowth through the stent meshes [15-17]. This process of epithelial hyperplasia causes embedding of the stent into the bile duct mucosa, making removal of uSEMS difficult or even impossible [18]. These drawbacks limit the use of uSEMS in the treatment of benign biliary strictures.

Only limited data comparing the efficacy and safety of different biliary stent types for benign biliary strictures are available. We therefore performed a systematic review of the current literature to assess technical and clinical success, and complications of different stent types for this indication.

Methods

Systematic search

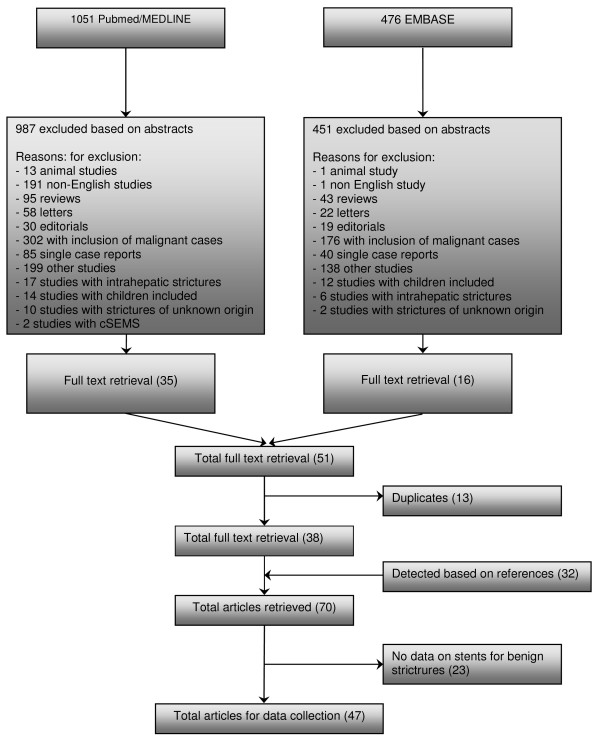

A systematic search of PubMed between January 1966 and March 2008 and EMBASE between January 1980 and March 2008 was performed. In PubMed, the MeSH headings 'cholestasis' and 'obstructive jaundice' were used in combination with the MeSH heading 'stent'. In EMBASE a similar search using the same headings was performed. We detected 1051 abstracts in PubMed and 476 abstracts in EMBASE and these 1527 abstracts were evaluated. All studies reporting on biliary stent placement in patients with benign strictures were included. Non-English language studies, letters, editorials, reviews, animal studies, single case reports, studies with data on covered self-expandable metal stents (cSEMS), studies with results on intrahepatic strictures, studies with strictures of unknown origin and studies in patients with malignant strictures or children were excluded. This resulted in 51 abstracts being retrieved as full text. Thirteen studies were excluded because they were duplicates and 23 studies because they contained no data on stent placement for benign biliary strictures. Another 32 studies were added after manual searching of references in the selected studies. Finally, 47 studies were retrieved for data extraction (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of search history on stents for benign extrahepatic biliary strictures.

Data extraction

Data on study design, number of patients, etiology and location of the stricture, route of stent placement, stent type, follow-up time, previous treatment, median stenting time, technical and clinical success rates, patency rate, complications, stricture recurrence and mortality were extracted.

Definitions

- Stenting time: the time between stent placement and removal. Stenting time in patients treated with uSEMS was defined as the time between stent placement and the moment that further treatment was indicated because of stent obstruction.

- Technical success: technically successful stent placement.

- Clinical success: no need for further treatment after stent placement, relief of symptoms and/or significant decrease in bilirubin level after stent placement.

- Complication: adverse event after stent placement, such as cholangitis, pancreatitis, stent migration or hemorrhage.

- Mortality: procedure-related and stent-related death.

Statistics

The following data were pooled using a fixed effect model: stenting time, technical success rate, clinical success rate, complications and mortality. The number of patients with a single plastic stent, multiple plastic stents and uSEMS were plotted against clinical and technical success rates, resulting in funnel plots, a statistical method used for assessing publication bias [19]. If publication bias is not present, a funnel plot is expected to be roughly symmetrical. The underlying idea is that studies with the largest number of patients estimate clinical and technical success rates more accurately than studies with fewer patients. As it may be difficult to establish publication bias by visual inspection [20], we used the Mann-Whitney U test and Spearman's rank correlation test to determine a correlation between technical and clinical success rates per stent type and the number of patients. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. SPSS software, version 15, (Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA) was used to perform the statistical analysis.

Results

Study types

From the 47 selected studies, data on outcome of biliary stenting in 1116 patients were extracted (Table 1, 2). Of these, 24 studies reported on single plastic stents [2,21-42], 6 on multiple plastic stents [43-48] and17 on uSEMS [15,16,49-63]. A single plastic stent was compared with multiple plastic stents in one non-randomized study [64]. The remaining studies were all case series, of which 33 were retrospective[16,21-29,31,35-37,39,41-44,47,49-51,53-55,59,60,62,64] and 14 prospective in design[15,30,32,34,38,40,45,48,52,56-58,61,63]

Table 1.

Case series with uncovered SEMS (uSEMS) for benign biliary strictures

| Author | Year | N | Age (years (range)) | Women | Intervention | Route | Etiology stricture | Location obstruction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prospective studies | ||||||||

| Yamaguchi et al [63] | 2006 | 8 | median 65,7 (42-78) | 0 | Streckerstent (2) | ERCP | chronic pancreatitis | CBD |

| O Brien et al [58] | 1998 | 8 | median 59 (26-88) | unknown | Wallstent | ERCP | postoperative/endoscopic (5) | hilair (3) |

| chronic pancreatitis (2) | proximal (5) | |||||||

| idiopathic (1) | ||||||||

| Deviere et al [15] | 1994 | 20 | mean 45 (27-61) | 4 | Wallstent | ERCP | chronic pancreatitis | CBD |

| Mygind et al (75) | 1993 | 2 | unknown | 2 | Z stent | PTC | post operative | CBD (1) |

| CBD and anastomosis (1) | ||||||||

| Maccioni et al [56] | 1992 | 18 | mean 60 (22-76) | 8 | Z stent (17) | PTC | post operative | anastomosis (13) |

| Wallstent (1) | CBD (5) | |||||||

| Foerster et al [52] | 1991 | 7 | median 60 (49-80) | 5 | Wallstent | ERCP (6) | postoperative | anastomosis (2) |

| PTC (1) | CBD (5) | |||||||

| hepatoduodenal fistel (1) | ||||||||

| Retrospective studies | ||||||||

| van Berkel et al [62] | 2004 | 13 | mean 56 (40-79) | 4 | Wallstent | ERCP | chronic pancreatitis | CBD |

| Roumilhac et al [60] | 2003 | 12 | unknown | unknown | Metal stent (12) | ERCP | post OLT | anastomosis (11) |

| Eickhoff et al [51] | 2003 | 6 | median 38 (29-60) | 1 | Wallstent | ERCP | chronic pancreatitis | CBD |

| Kahl et al [55] | 2002 | 3 | mean 48 (21-81) | 1 | Wallstent (3) | ERCP | chronic pancreatitis | CBD |

| Bonnel et al [49] | 1997 | 25 | mean 64 (35-86) | 13 | Z stent | PTC | postoperative | CBD (8) |

| anastomosis (17) | ||||||||

| Rieber et al [59] | 1996 | 8 | mean 42 (17-66) | 3 | Palmaz stent | PTC | post OLT | anastomosis (5) |

| nonanastomotis (3) | ||||||||

| Hausegger et al [53] | 1996 | 20 | mean 62 (36-83) | 7 | Wallstent | PTC | chronic pancreatitis (7) | anastomosis (4) |

| fibrous papillary stenosis (2) | CBD (16) | |||||||

| psc (1) | ||||||||

| post operative (10) | ||||||||

| Chu et al [50] | 1994 | 2 | unknown | unknown | Z stent | PTC | post operative | hilair (1) |

| CBD (1) | ||||||||

| Ivancev et al [54] | 1992 | 2 | 66 and 41 | 2 | Z stent | PTC | post operative | anastomosis (1) |

| CBD (1) | ||||||||

| Rossi et al [16] | 1990 | 17 | mean 60 (22-76) | 7 | Z stent | PTC | postoperative | anastomosis (13) |

| CBD (4) |

Table 2.

Case series with multiple plastic stents and single plastic stents for benign biliary strictures

| Author | Year | N | Age (years (range)) | Women | Intervention | Route | Etiology stricture | Location obstruction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prospective studies | ||||||||

| Holt et al [32] | 2007 | 53 | 48,5 (37-61) | 32 | single plastic stent | ERCP | post OLT | anastomosis |

| Graziadei et al [30] | 2006 | 84 | 53,5 | 21 | single plastic stent | ERCP | post OLT | anastomosis (65) |

| non anastomosis (19) | ||||||||

| Pozsar et al [48] | 2005 | 20 | mean 61,3 (36-81) | 18 | multiple plastic stents | ERCP | post sphincterectomy | distal CBD |

| Kuzela et al [45] | 2005 | 43 | mean 50,3 (37-82) | 25 | multiple plastic stents | ERCP | post operative | hilair |

| Kahl et al [34] | 2003 | 61 | median 47 (21-81) | 15 | single plastic stent | ERCP | chronic pancreatitis (61) | CBD |

| Tocchi et al [38] | 2000 | 20 | mean 57 | 10 | single plastic stent | ERCP | post operative | CBD (3) |

| hilair (17) | ||||||||

| van Milligen et al [40] | 1997 | 16 | median 43 (17-69) | 8 | single plastic stent | ERCP | psc | CBD (10) |

| hiliar (6) | ||||||||

| Retrospective studies | ||||||||

| Pasha et al [47] | 2007 | 25 | mean 46,7 (28-59) | 4 | multiple plastic stents | ERCP | post OLT | anastomosis |

| Elmi et al [28] | 2007 | 15 | 52 year (42-68) | 9 | single plastic stent | ERCP | post OLT | anastomosis |

| Akay et al [21] | 2006 | 11 | 42 (17-60) | 6 | single plastic stent | ERCP | post OLT | anastomosis |

| Sharma et al [37] | 2006 | 8 | median 42 (20-61) | 3 | single plastic stent | ERCP | idiopathic | CBD (6) |

| hilair (2) | ||||||||

| Alazmi et al [22] | 2006 | 143 | unknown | unknown | single plastic stent | ERCP | post OLT | anastomosis |

| Zoepf et al [42] | 2005 | 7 | median 55 (45-65) | unknown | single plastic stent | ERCP | post OLT | anastomosis |

| Cahen et al [25] | 2005 | 58 | median 54 (19-85) | 10 | single plastic stent | ERCP | chronic pancreatitis | CBD |

| Catalano et al [64] | 2004 | 46 | mean 48 (30-71) | 11 | 1 plastic stent (34) | ERCP | chronic pancreatitis | CBD |

| multiple plastic stents (12) | ||||||||

| Morelli et al [46] | 2003 | 25 | mean 48 (18-72) | 9 | multiple plastic stents | post OLT | anastomosis | |

| Hisatsune et al [31] | 2003 | 19 | 45 (14-67) | 9 | single plastic stent | ERCP | post OLT | anastomosis |

| Eickhoff et al [27] | 2001 | 39 | mean 54,7 (32-81) | 7 | single plastic stent | ERCP | chronic pancreatitis (39) | CBD |

| Bourke et al [43] | 2000 | 6 | mean 53 (20-64) | 3 | multiple plastic stents | ERCP | post sphyncterectomy | ampullary |

| Khandekar et al [44] | 2000 | 17 | median 50 (17-68) | 13 | multiple plastic stents | ERCP | post sphyncterectomy (10) | CBD (14) |

| papillotomy (2) | other (3) | |||||||

| post operative (3) | ||||||||

| Vitale et al [41] | 2000 | 25 | mean 46,7 (36-89) | 7 | single plastic stent | ERCP | chronic pancreatitis | CBD |

| Kiehne et al [35] | 2000 | 14 | (36-89) | 2 | single plastic stent | chronic pancreatitis | CBD | |

| Farnbacher et al [29] | 2000 | 31 | 50 (24-71) | 3 | single plastic stent | ERCP | chronic pancreatitis | CBD |

| Rossi et al [36] | 1998 | 15 | mean 44 (28-55) | 6 | single plastic stent | ERCP | post OLT (15) | anastomosis |

| De Masi et al [26] | 1998 | 53 | unknown | unknown | single plastic stent | ERCP | iatrogenic (39) | CBD (20) |

| gallstones (8) | hilair (30) | |||||||

| Aru et al [23] | 1997 | 8 | mean 44 | 7 | single plastic stent | ERCP | post operative | CBD (7) |

| hilair (1) | ||||||||

| van Milligen et al [39] | 1996 | 25 | median 42 (21-74) | 13 | single plastic stent | ERCP | psc | CBD (19) |

| hilair (3) | ||||||||

| Itani et al [33] | 1995 | 5 | unknown | unknown | single plastic stent | ERCP | chronic pancreatitis | CBD |

| Barthet et al [24] | 1994 | 19 | mean 49 | 1 | single plastic stent | ERCP | chronic pancreatitis | CBD |

| Deviere et al [2] | 1990 | 25 | mean 42 (34-69) | 1 | single plastic stent | ERCP | chronic pancreatitis | CBD |

Patients

Fourty seven studies evaluated 786 patients treated with a single plastic stent (7-11.5 Fr.), 148 with multiple plastic stents (10-11.5 Fr.) and 182 with uSEMS.

Indications for stent placement included a biliary stricture secondary to liver transplantation (n = 417, 37%), chronic pancreatitis (n = 380, 34%), surgery (n = 170, 16%), and other causes (n = 149,13%).

Most strictures were located in the CBD (47%), followed by anastomotic strictures (40%), hilar strictures (11%) and other locations (2%) (Table 3, 4).

Table 3.

Results on route, previous treatment, treatment time, technical success, clinical success and complications in case series with uncovered SEMS (uSEMS) for benign biliary strictures

| Author | Intervention | Follow up (range) | Previous treatment | Technical success | Clinical succes | Treatment time Stentpatency | Total complications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prospective studies | |||||||

| Yamaguchi et al [63] | Streckerstent (2) | > 5 years (7.4 year) | plastic stent placement | 100% | 62,50% | unknown | 25% |

| Wallstent (6) | |||||||

| O Brien et al [58] | Wallstent | mean 64,5 months (26-81) | plastic stent placement (5) | 100% | unknown | median 35 months (7-57) | 75 |

| Tesdal et al [69] | Wallstent (11) | mean 63,8 months | balloon dilatation (19) | 100% | unknown | mean 30,2 months | 64,50% |

| Palmazstent (9) | median 80,5 (2-116) | ||||||

| Streckerstent(4) | |||||||

| Deviere et al [15] | Wallstent | mean 33 months (24-42) | plastic stent placement (11) | 100% | 90% | 3 and 6 months (2/20) | 10 |

| Mygind et al (75) | Z stent | 4 and 7 months | balloon dilatation | 100% | 100% | unknown | unknown |

| Maccioni et al [56] | Z stent (17) | mean 37 months (30-41) | percutaneous dilatation | 83,30% | 55,50% | unknown | 38,80% |

| Wallstent (1) | |||||||

| Foerster et al [52] | Wallstent | mean 32,7 weeks (21-53) | laparotomy (2) | 100% | 100% | 8 months until now | 14% |

| Retrospective studies | |||||||

| van Berkel et al [62] | Wall stent | mean 50 months (6 d -86 months) | none | 100% | 69% | 60 months | 15,40% |

| Roumhilac et al [60] | SEMS (12) | median 37 months (18-53) | plastic stent treatment for 1 year | 100% | 100% | no stent obstruction | unknown |

| Eickhoff et al [51] | Wallstent | median 58 months (22-29) | plastic stent placement | 100% | unknown | median 20 months (10-38) | 83,40% |

| Kahl et al [55] | Wallstent (3) | median 37 months (18-53) | plastic stent treatment for 1 year | 100% | 100% | no stent obstruction | unknown |

| Bonnel et al [49] | Z stent | mean 55 months (9-84) | surgery (17) | 18 one approach | 72% | 36% | |

| T tube (8) | 7 two approaches | ||||||

| Rieber et al [59] | Palmaz stent | mean 18 months (1,5-43) | balloon dilatation | 100% | 62% occlusion | ||

| post PTBD | occlussion time 1,5-2,5-24 months |

||||||

| Hausegger et al [53] | Walsltent | mean 31,2 months (3-78) | balloon dilatation | 100% | unknown | 73% (6 months) | 50,00% |

| 38% (36 months) | |||||||

| 19% (end follow up) | |||||||

| 3-3-3-4-5-11-24-2-36-55 | |||||||

| Chu et al [50] | Z stent | unknown | plastic stents | unknown | 0% | ||

| PTBD | |||||||

| Ivancev et al [54] | Z stent (2) | 9 and 14 months | balloon dilatation | 100% | 50% | 50% (5 months) | 50% |

| Rossi et al [16] | Z stent | mean 8 months (4-12) | baloon dilatition | 100% | 82,40% | unknown | 11,80% |

Table 4.

Results on route, previous treatment, treatment time, technical success, clinical success and complications in case series with multiple plastic stents and single plastic stents for benign biliary strictures

| Author | Intervention | Follow up (range) | Previous treatment | Technical success | Clinical succes | Treatment time Stentpatency |

Total complications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prospective studies | |||||||

| Holt et al [32] | single plastic stent | 18 months | balloon dilatation | 92% | 69% | 11,3 months (7-14) | 69,70% |

| Graziadei et al [30] | single plastic stent | mean 39,8 (0,3-98) | balloon dilatation | unknown | 77% anastomosis | unknown | 5-424 procedures |

| 0% non anastomosis | |||||||

| Pozsar et al [48] | multiple stent placement | mean 61,3 (36-81) | dilatation | unknown | 90% | median 9 months (3-22) | 37,70% |

| Kuzela et al [45] | multiple stent placement | median 16 months (1-42) | none | 100% | 100% | 1 year | 12% |

| after stent placement | (planned) | ||||||

| Tocchi et al [38] | single plastic stent | mean 89,7 months | none | 100% | 80% | unknown | 0% |

| Kahl et al [34] | single plastic stent | median 40 months (18-66) | none | 100% | 31,1% (1 year) | 1 year (19) | 34,40% |

| 26,2% (40 months) | rest unknown | ||||||

| van Milligen et al [40] | single plastic stent | median 19 months (7-27) | none | 100% | 81% | median 9 days | 7% |

| Retrospective studies | |||||||

| Pasha et al [47] | multiple plastic stent | median 21,5 months (5,4-31,2) | diliatation | unknown | 88% (intend to treat) | median 4,6 months (1,1-11,9) | 27% |

| Elmi et al [28] | single plastic stent | 535 days (22-1301) | balloondilatation | Unknown | 87% | 192 days (18-944) | 22,2% (procedure) |

| sphincterectomy | |||||||

| Akay et al [21] | single plastic stent | 22 months (SD 13 months) | balloondilatation | 75% | 55% | 3 months (6) | 12% |

| 6 months (1) | |||||||

| 9 months (1) | |||||||

| 12 months (3) | |||||||

| Sharma et al [37] | single plastic stent | median 19 months (4-52) | balloondilatation | 100% | 100% | median 19 months | 18% |

| Alazmi et al [22] | single plastic stent | mean 28 months (1-114) | balloondilatation | 6,60% | 82% | unknown | unknown |

| Zoepf et al [42] | single plastic stent | median 9,5 months (1-36) | sometimes dilatation | 100% | 85,60% | median 8 months (2-26) | 18,60% |

| Cahen et al [25] | single plastic stent | median 45 months (0-182) | sphincterectomy | 100% | 38% | median 274 days (3-2706) | 52% |

| pancreatic duct stenting | |||||||

| Catalano et al [64] | single plastic stent (34) | mean 4,2 years (1 plastic stent) | unknown | 100% | 24% 1 stent | 21 months | 42,7% (single plastic stent) |

| multiple plastic stent (12) | mean 3,9 years (mulitple stents) | 92% multiple stents | 14 months | 8,3% (multiple plastic stent) | |||

| Morelli et al [46] | multiple plastic stent | mean 54 weeks (5 wks - 103 mo) | diliatation | 88% | 90% | unknown | 3,70% |

| Hisatsune et al [34] | single plastic stent | mean 26 months(15-44) | none | 79% | 93% | mean 637 days (487-933) | 43% |

| Eickhoff et al [31] | single plastic stent | median 58 months (2-146) | balloon dilatation | 100% | 31% | mean 9 months (1-144) | 43% |

| nasobiliary drainage | |||||||

| Bourke et al [43] | multiple plastic stent | median 26,5 months (24-32) | dilatation | unknown | 100% | median 12,5 months | 33% |

| Author | Intervention | Follow up (range) | Previous treatment | Technical success | Clinical succes |

Treatment time Stentpatency |

Total complications |

| Khandekar et al [44] | multiple plastic stent | median 720 days | sometimes dilatation | Unknown | 100% | median 140 days (30-1080) | unknown |

| Vitale et al [41] | single plastic stent | 32 months (13-76) | balloon dilatation | Unknown | 80% | mean 13,3 months | unknown |

| Khiene et al [35] | single plastic stent | 1-5 years | none | 100% | 7,40% | unknown | 85,70% |

| Farnbacher et al [29] | single plastic stent | 24 months (2-76) | none | 100% | 13% | 24 months (2-76 months) | 72% |

| Rossi et al [36] | single plastic stent | 1 year | dilatation | 100% | 83,30% | 1 year | 33,30% |

| De Masi et al [26] | single plastic stent | 6-84 months | unknown | Unknown | 71,40% | 24 months | 52,70% |

| Aru et al [23] | single plastic stent | unknown | unknown | 100% | 25% | unknown | unknown |

| van Millegen et al [39] | single plastic stent | mean 29 months (2-120) | dilatation nasobiliary drain |

84% | 76% | 1 stent period (17) | 30,5%(procedure) |

| 2 stent period (2) | |||||||

| 3 stent period (3) | |||||||

| Itani et al [33] | single plastic stent | mean 7 months | dilatation | 100% | 80% | 4 months (2) | unknown |

| 1 change 4 months (2) | |||||||

| 15 months (1) | |||||||

| Barthet et al [24] | single plastic stent | mean 18 months (13-48) | none | 100% | 42% | mean 10 months | 10,50% |

| Deviere et al [2] | single plastic stent | mean 14 months (4-72) | dilatation | 100% | 12% | unknown | 72% |

In the majority of patients with chronic pancreatitis, a single plastic stent was placed (85%), followed by uSEMS (15%) and multiple plastic stents (0%). Similarly, single plastic stents were placed in 82% of patients with a biliary stricture after liver transplantation, followed by uSEMS (22%) and multiple plastic stents (13%). In patients with a biliary stricture after a surgical procedure uSEMS (50%) were placed most frequently followed by multiple plastic stents (35%) and a single plastic stent (15%).

Comparison between different stent types

The median stenting time was not different between multiple plastic stents (11.3 (range 4.6-13) months) and single plastic stents (10.5 (0.3-24) months). Median stenting time was 20 (4.5-60) months for uSEMS.

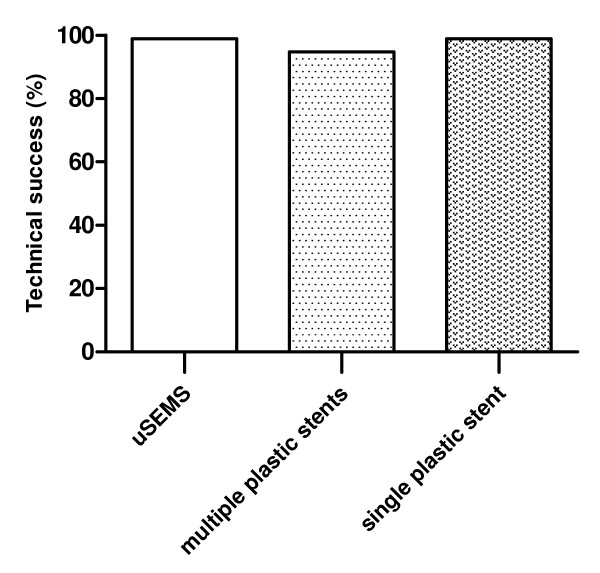

The technical success rate was not different between different stent types (98,9% for uSEMS and 94.8% for single plastic stents, 94.0% for multiple plastic stents) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Technical success of uncovered SEMS (uSEMS), multiple plastic stents and single plastic stents for benign biliary strictures.

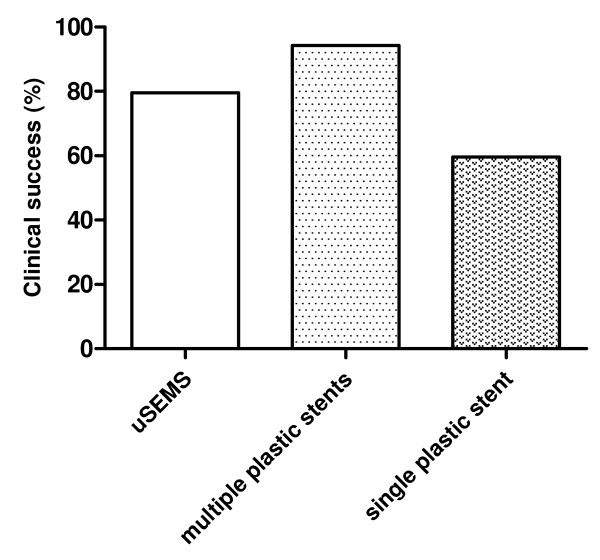

The clinical success rate for all patients was highest after placement of multiple plastic stents (94,3%) followed by uSEMS (79.5%) and single plastic stents (59,6%) (Figure 3). Clinical success rate in chronic pancreatitis patients was highest for uSEMS (80.4%) and lowest for single plastic stents (35.9%). Multiple plastic stents had the best clinical performance for strictures following liver transplantation (89.0%) and surgery (81.3%), whereas uSEMS (69% and 62.3%, respectively) showed the worst clinical results in these situations (Table 5).

Figure 3.

Clinical success of uncovered SEMS (uSEMS), multiple plastic stents and single plastic stents for benign biliary strictures.

Table 5.

Overview of technical and clinical success of uncovered SEMS (uSEMS), multiple plastic stents and single plastic stents for benign biliary strictures

| Single plastic stent | USEMS | Multiple plastic stents | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Technical success | Clinical success | Technical success | Clinical success | Technical success | Clinical success | |

| (mean) | (mean) | (mean) | (mean) | (mean) | (mean) | |

| All indications | 94,10% | 61.3% | 98,50% | 62,40% | 97,60% | 87,50% |

| Post operative | 86,6,% | 64,90% | 97,60% | 59,60% | 100 | 87,60% |

| Chronic pancreatitis | 100% | 36,60% | 100% | 80,40% | NA | NA |

| Post OLT | 97,20% | 81% | 100% | 50% | 88% | 89% |

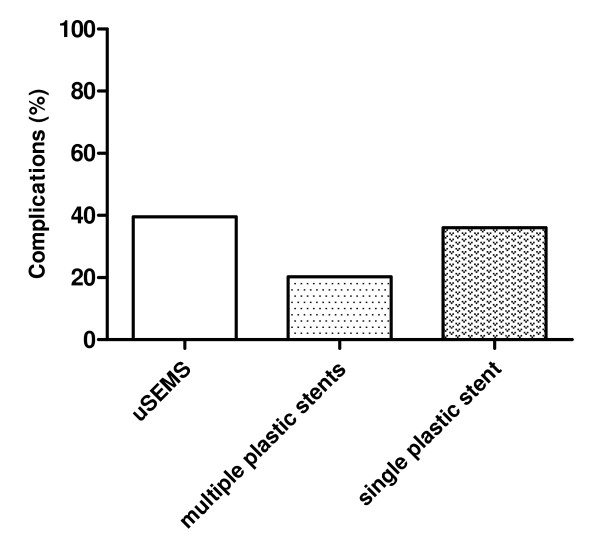

Complications occurred most frequently with uSEMS (39.5%), followed by a single plastic stent (36.0%) and multiple plastic stents (20.3%) (Figure 4). The most frequently reported complications included cholangitis, pancreatitis, stent migration and hemorrhage.

Figure 4.

Complications of uncovered SEMS (uSEMS), multiple plastic stents and single plastic stents for benign biliary strictures.

No stent-related mortality was reported with placement of multiple plastic stents, whereas 7 (0.9%) patients died as a consequence of single plastic stent placement. Following uSEMS placement, 2 (1.1%) patients died of a stent-related cause. In all these cases, the cause of death was a septic complication due to cholangitis.

Publication bias

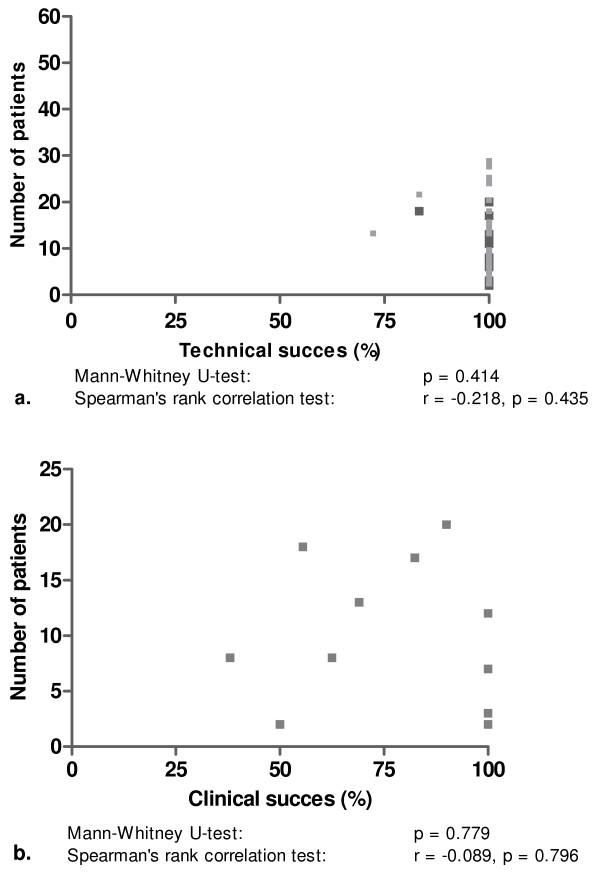

Plotting the total number of patients with uSEMS against technical and clinical success showed that publication bias was not present (Figure 5). This was confirmed with Spearman's rank correlation test for technical (r-0.218, p = 0.435) and clinical success (r-0.089, p = 0.796) against the number of included patients. The same was found when technical success and clinical success rates in publications with ≤ 8 or >8 patients were compared (p = 0.414 and p = 0.779, respectively).

Figure 5.

Numbers of patients with a benign biliary stricture vs. reported results for technical success (a) and clinical success (b) of uncovered self-expanding metal stent placement.

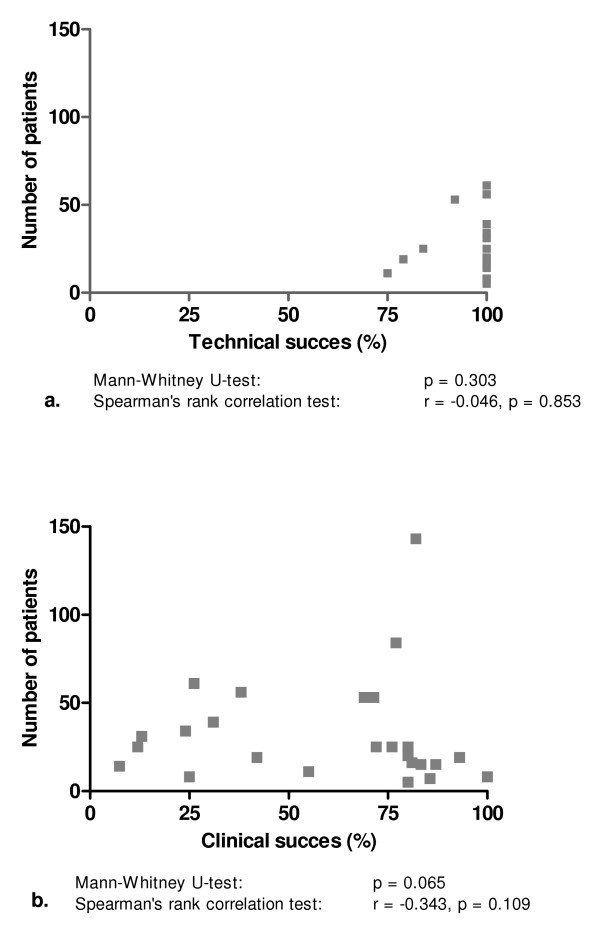

We also plotted the number of patients with a single plastic stent against technical and clinical success and again found no evidence of publication bias (Figure 6). Similarly, no evidence of bias was found when the clinical success in publications with ≤ 20 or >20 included patients were compared (p = 0.065). For clinical success, this was confirmed with Spearman's rank correlation test (r-0.343, p = 0.109). For technical success, however, Spearman's rank correlation test suggested publication bias (r-0.046, p = 0.109). On the other hand, no evidence of bias was found when publications with ≤ 20 or >20 patients were compared (p = 0.303).

Figure 6.

Numbers of patients with a benign biliary stricture vs. reported results for technical success (a) and clinical success (b) of single plastic stent placement.

As the number of publications on multiple plastic stents (n = 6) in benign biliary stricture was low, it was not possible to make funnel plots for this stent type.

Discussion

This review shows that the most optimal nonsurgical treatment of benign extrahepatic biliary strictures has been demonstrated with multiple plastic stent placement. These results confirm that dilation with a large diameter dilator, i.e. multiple plastic stents, for a prolonged period is the most effective way to relieve benign strictures. It is however important to note that these results were mainly based on case series with often small patient numbers included.

Complication rates were also lowest for multiple plastic stents, followed by single plastic stents and uSEMS. The low complication rate of multiple plastic stents is most likely due to the practice of exchanging multiple plastic stents at 3-months intervals. This was found to be uncommon after single plastic stent placement. In the latter, cholangitis as a result of stent clogging occurred more frequently. Due to their larger luminal diameter, placement of uSEMS seems an attractive alternative for single or multiple plastic stents in benign biliary strictures, however uSEMS have the disadvantage that tissue hyperplasia through uncovered stent meshes may occur, leading to stent obstruction [15,16,65]. Based on clinical success and complication rates, placement of multiple plastic stents has therefore still the best treatment profile for treatment of benign biliary strictures.

Our findings are in line with results of stent placement for specific causes of benign biliary obstruction, particularly those following liver transplantation or a surgical procedure. Only for patients with strictures due to chronic pancreatitis, uSEMS were found to give good results with regard to clinical success. The number of studies that included patients with this indication and were treated with multiple plastic stents was low. The reason for this is likely that biliary obstruction due to chronic pancreatitis often has a protracted course, requiring multiple procedures if plastic stents are used [66].

An exception to the overall poor results of endoscopic treatment with single plastic stents in patients with chronic pancreatitis was reported by Vitale et al. [41], who achieved stricture resolution with single plastic stents in 80% of patients. Calcifications in the pancreatic head were found in only 4 of 25 patients in this study, which may well explain the high success rate. Calcifications in the pancreatic head have been suggested to be a strong predictor of failure of CBD stenting [34]. As these calcifications are often associated with a firm fibrotic component due to the inflammatory reaction in chronic pancreatitis [67], it can be expected that these strictures are more difficult to dilate. Patients with chronic pancreatitis but without calcifications are more likely to have a stricture secondary to edema and to have less pronounced fibrosis. These strictures may subside over time and therefore only require temporary treatment. This explains why single plastic stent placement for CBD strictures in this patient category was found to be successful (78).

It should be noted that the disappointing results of uSEMS placement, particularly in patients with biliary strictures following liver transplantation or a surgical procedure, are probably affected by selection bias. In most studies, the included population consisted of patients in whom the initial treatment, mostly plastic stent placement, had already failed. As a consequence, these patients were probably more difficult to treat and less responsive to dilation.

We found that the median stenting time was not different between multiple and single plastic stent placement (11.3 vs.10.5 months, respectively).uSEMS functioned clinically well for a median time of 20 months (0.5-60) before a reintervention, mostly for stent obstruction, was needed. Reported reinterventions included placement of a new stent within the occluded uSEMS, percutaneous biliary drainage, endoscopic removal of sludge, or surgical or endoscopic removal of the stent.

A problem with uSEMS is that they tend to embed into the mucosa of the CBD, leading to mucosal hyperplasia. This is an unwanted side effect, as removal of uSEMS in this situation is difficult, if not impossible. Removal may however be indicated when uSEMS are malpositioned or obstructed, or have (partially) migrated [18,68]. Recently, cSEMS have been introduced. These devices have the benefit that removal is possible as the risk of embedding into the biliary wall is reduced or even negligible. This capacity combined with the larger diameter of cSEMS makes stepwise dilation, as is performed with multiple plastic stents, unnecessary and may thus reduce the number of procedures [69]. The clinical experience with cSEMS for benign biliary strictures is until now only limited [66,69,69]. cSEMS can achieve a luminal diameter that is comparable to that of multiple plastic stents and uSEMS, but due to their covering have the advantage that fewer procedures for recurrent obstruction are required. In the future, cSEMS are likely to be a more patient-friendly and cost-effective treatment option for benign biliary strictures. Until now, cSEMS placement for benign biliary strictures is still associated with relatively high complication rates (39.6%) [66,69,69]. In our opinion, new covered stents and refinements of existing covered stents are needed before large scale introduction of cSEMS for this indication can be recommended.

This review has several limitations which should be taken into account before concluding that a particular stent type is favorable in patients with a benign biliary stricture. First, no randomized trials and only one comparative trial have been conducted. This may be due to the fact that (multiple) plastic stents have an acceptable technical and clinical success rate in daily clinical practice. Moreover, uSEMS placement has not been shown to be more successful than multiple plastic stents in case series.

Secondly, several types of plastic stents were used in different studies. Results on individual plastic stent types in patients with benign biliary strictures are not available. From trials in patients with malignant biliary strictures, it is however known that different plastic stents types have varying luminal patencies, due to the stent material and/or the stent diameter [70-73]. Particularly, plastic stents with a diameter of 10 French (Fr.) have been shown to be remain patent for a significantly longer period than 8 Fr. stents (median 32 vs. 12 weeks) [71].

Finally, there was a wide variety in treatment protocols in the various studies with plastic stents. In some studies, stent exchange was performed at 3-month intervals, while in other studies stents were only exchanged when they became occluded. Besides, the number of plastic stents used for multiple stenting varied between 2 and 4 among patients. This could both have affected clinical success rates, but also complication rates in patients treated with plastic stents.

The strength of this review is that all available data on the use of plastic stents and SEMS for the treatment of biliary strictures was evaluated. To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest review on the use of different types of stents in patients with a benign biliary stricture, with pooled data on 1116 treated patients. We also showed that the reported results, particularly those of single plastic stents and uSEMS, were not affected by publication bias, making an overestimation of the clinical success rate and/or an underestimation of the complication rate of a particular stent type unlikely.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this systematic review shows that, based on clinical success and risk of complications, placement of multiple plastic stents is currently the best choice. The evolving role of cSEMS placement as a more patient friendly and cost effective treatment for benign biliary strictures needs further elucidation. There is a need for RCTs comparing different stent types for this indication.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

PB: literature search, data interpretation, writing of the manuscript. FV: data interpretation, manuscript editing. PS: data interpretation, manuscript editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Contributor Information

Petra GA van Boeckel, Email: p.g.a.vanboeckel@umcutrecht.nl.

Frank P Vleggaar, Email: f.p.vleggaa@umcutrecht.nl.

Peter D Siersema, Email: p.d.siersema@umcutrecht.nl.

References

- Lillemoe KD, Melton GB, Cameron JL, Pitt HA, Campbell KA, Talamini MA. et al. Postoperative bile duct strictures: management and outcome in the 1990s. Ann Surg. 2000;232(3):430–41. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200009000-00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deviere J, Devaere S, Baize M, Cremer M. Endoscopic biliary drainage in chronic pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1990;36(2):96–100. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5107(90)70959-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judah JR, Draganov PV. Endoscopic therapy of benign biliary strictures. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13(26):3531–9. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i26.3531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warshaw AL, Schapiro RH, Ferrucci JT Jr, Galdabini JJ. Persistent obstructive jaundice, cholangitis, and biliary cirrhosis due to common bile duct stenosis in chronic pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 1976;70(4):562–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roslyn JJ, Ferdinand FD. Current therapy in gastroenterology and liver disease. 4. 1994. Biliary strictures and neoplasms; pp. 613–8. [Google Scholar]

- Davids PH, Rauws EA, Coene PP, Tytgat GN, Huibregtse K. Endoscopic stenting for post-operative biliary strictures. Gastrointest Endosc. 1992;38(1):12–8. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5107(92)70323-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumonceau JM, Deviere J, Delhaye M, Baize M, Cremer M. Plastic and metal stents for postoperative benign bile duct strictures: the best and the worst. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;47(1):8–17. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5107(98)70292-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geenen DJ, Geenen JE, Hogan WJ, Schenck J, Venu RP, Johnson GK. et al. Endoscopic therapy for benign bile duct strictures. Gastrointest Endosc. 1989;35(5):367–71. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5107(89)72836-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huibregtse K, Katon RM, Tytgat GN. Endoscopic treatment of postoperative biliary strictures. Endoscopy. 1986;18(4):133–7. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1018353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MT, Sherman S, Lehman GA. Endoscopic management of benign strictures of the biliary tree. Endoscopy. 1995;27(3):253–66. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1005681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smits ME, Rauws EA, van Gulik TM, Gouma DJ, Tytgat GN, Huibregtse K. Long-term results of endoscopic stenting and surgical drainage for biliary stricture due to chronic pancreatitis. Br J Surg. 1996;83(6):764–8. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800830612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitale GC, George M, McIntyre K, Larson GM, Wieman TJ. Endoscopic management of benign and malignant biliary strictures. Am J Surg. 1996;171(6):553–7. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(96)00031-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman JJ, Burgemeister L, Bruno MJ, Rauws EA, Gouma DJ, Tytgat GN. et al. Long-term follow-up after biliary stent placement for postoperative bile duct stenosis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54(2):154–61. doi: 10.1067/mge.2001.116455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davids PH, Groen AK, Rauws EA, Tytgat GN, Huibregtse K. Randomised trial of self-expanding metal stents versus polyethylene stents for distal malignant biliary obstruction. Lancet. 1992;340(8834-8835):1488–92. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)92752-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deviere J, Cremer M, Baize M, Love J, Sugai B, Vandermeeren A. Management of common bile duct stricture caused by chronic pancreatitis with metal mesh self expandable stents. Gut. 1994;35(1):122–6. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.1.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi P, Bezzi M, Salvatori FM, Maccioni F, Porcaro ML. Recurrent benign biliary strictures: management with self-expanding metallic stents. Radiology. 1990;175(3):661–5. doi: 10.1148/radiology.175.3.2343110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Berkel AM, Cahen DL, van Westerloo DJ, Rauws EA, Huibregtse K, Bruno MJ. Self-expanding metal stents in benign biliary strictures due to chronic pancreatitis. Endoscopy. 2004;36(5):381–4. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-814319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahaleh M, Tokar J, Le T, Yeaton P. Removal of self-expandable metallic Wallstents. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60(4):640–4. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5107(04)01959-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger M, Davey SG, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629–34. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terrin N, Schmid CH, Lau J. In an empirical evaluation of the funnel plot, researchers could not visually identify publication bias. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58(9):894–901. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akay S, Karasu Z, Ersoz G, Kilic M, Akyildiz M, Gunsar F. et al. Results of endoscopic management of anastomotic biliary strictures after orthotopic liver transplantation. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2006;17(3):159–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alazmi WM, Fogel EL, Watkins JL, McHenry L, Tector JA, Fridell J. et al. Recurrence rate of anastomotic biliary strictures in patients who have had previous successful endoscopic therapy for anastomotic narrowing after orthotopic liver transplantation. Endoscopy. 2006;38(6):571–4. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-925027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aru GM, Davis CR Jr, Elliott NL, Morris SJ. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in the treatment of bile leaks and bile duct strictures after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. South Med J. 1997;90(7):705–8. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199707000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barthet M, Bernard JP, Duval JL, Affriat C, Sahel J. Biliary stenting in benign biliary stenosis complicating chronic calcifying pancreatitis. Endoscopy. 1994;26(7):569–72. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1009041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahen DL, van Berkel AM, Oskam D, Rauws EA, Weverling GJ, Huibregtse K. et al. Long-term results of endoscopic drainage of common bile duct strictures in chronic pancreatitis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;17(1):103–8. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200501000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Masi ME, Fiori E, Lamazza A, Ansali A, Monardo F, Lutzu SE. et al. Endoscopy in the treatment of benign biliary strictures. Ital J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;30(1):91–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eickhoff A, Jakobs R, Leonhardt A, Eickhoff JC, Riemann JF. Endoscopic stenting for common bile duct stenoses in chronic pancreatitis: results and impact on long-term outcome. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;13(10):1161–7. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200110000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmi F, Silverman WB. Outcome of ERCP in the management of duct-to-duct anastomotic strictures in orthotopic liver transplant. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52(9):2346–50. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9142-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farnbacher MJ, Rabenstein T, Ell C, Hahn EG, Schneider HT. Is endoscopic drainage of common bile duct stenoses in chronic pancreatitis up-to-date? Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95(6):1466–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.02078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graziadei IW, Schwaighofer H, Koch R, Nachbaur K, Koenigsrainer A, Margreiter R. et al. Long-term outcome of endoscopic treatment of biliary strictures after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2006;12(5):718–25. doi: 10.1002/lt.20644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hisatsune H, Yazumi S, Egawa H, Asada M, Hasegawa K, Kodama Y. et al. Endoscopic management of biliary strictures after duct-to-duct biliary reconstruction in right-lobe living-donor liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2003;76(5):810–5. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000083224.00756.8F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt AP, Thorburn D, Mirza D, Gunson B, Wong T, Haydon G. A prospective study of standardized nonsurgical therapy in the management of biliary anastomotic strictures complicating liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2007;84(7):857–63. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000282805.33658.ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itani KM, Taylor TV. The challenge of therapy for pancreatitis-related common bile duct stricture. Am J Surg. 1995;170(6):543–6. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(99)80012-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahl S, Zimmermann S, Genz I, Glasbrenner B, Pross M, Schulz HU. et al. Risk factors for failure of endoscopic stenting of biliary strictures in chronic pancreatitis: a prospective follow-up study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(11):2448–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.08667.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiehne K, Folsch UR, Nitsche R. High complication rate of bile duct stents in patients with chronic alcoholic pancreatitis due to noncompliance. Endoscopy. 2000;32(5):377–80. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-9004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi AF, Grosso C, Zanasi G, Gambitta P, Bini M, De CL. et al. Long-term efficacy of endoscopic stenting in patients with stricture of the biliary anastomosis after orthotopic liver transplantation. Endoscopy. 1998;30(4):360–6. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1001283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma BC, Agarwal N, Agarwal A, Sakhuja P, Sarin SK. Idiopathic benign strictures of the extrahepatic bile duct: results of endoscopic therapy. Digestive Endoscopy. 2006. pp. 277–81. [DOI]

- Tocchi A, Mazzoni G, Liotta G, Costa G, Lepre L, Miccini M. et al. Management of benign biliary strictures: biliary enteric anastomosis vs endoscopic stenting. Arch Surg. 2000;135(2):153–7. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.135.2.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Milligen de Wit AW, van BJ, Rauws EA, Jones EA, Tytgat GN, Huibregtse K. Endoscopic stent therapy for dominant extrahepatic bile duct strictures in primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;44(3):293–9. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5107(96)70167-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Milligen de Wit AW, Rauws EA, van BJ, Mulder CJ, Jones EA, Tytgat GN. et al. Lack of complications following short-term stent therapy for extrahepatic bile duct strictures in primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;46(4):344–7. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5107(97)70123-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitale GC, Reed DN Jr, Nguyen CT, Lawhon JC, Larson GM. Endoscopic treatment of distal bile duct stricture from chronic pancreatitis. Surg Endosc. 2000;14(3):227–31. doi: 10.1007/s004640030046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoepf T, Maldonado-Lopez EJ, Hilgard P, Schlaak J, Malago M, Broelsch CE. et al. Endoscopic therapy of posttransplant biliary stenoses after right-sided adult living donor liver transplantation. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3(11):1144–9. doi: 10.1016/S1542-3565(05)00850-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourke MJ, Elfant AB, Alhalel R, Scheider D, Kortan P, Haber GB. Sphincterotomy-associated biliary strictures: features and endoscopic management. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52(4):494–9. doi: 10.1067/mge.2000.108970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khandekar S, Disario JA. Endoscopic therapy for stenosis of the biliary and pancreatic duct orifices. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52(4):500–5. doi: 10.1067/mge.2000.108715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuzela L, Oltman M, Sutka J, Hrcka R, Novotna T, Vavrecka A. Prospective follow-up of patients with bile duct strictures secondary to laparoscopic cholecystectomy, treated endoscopically with multiple stents. Hepatogastroenterology. 2005;52(65):1357–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morelli J, Mulcahy HE, Willner IR, Cunningham JT, Draganov P. Long-term outcomes for patients with post-liver transplant anastomotic biliary strictures treated by endoscopic stent placement. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58(3):374–9. doi: 10.1067/S0016-5107(03)00011-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasha SF, Harrison ME, Das A, Nguyen CC, Vargas HE, Balan V. et al. Endoscopic treatment of anastomotic biliary strictures after deceased donor liver transplantation: outcomes after maximal stent therapy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66(1):44–51. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pozsar J, Sahin P, Laszlo F, Topa L. Endoscopic treatment of sphincterotomy-associated distal common bile duct strictures by using sequential insertion of multiple plastic stents. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62(1):85–91. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5107(05)00547-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnel DH, Liguory CL, Lefebvre JF, Cornud FE. Placement of metallic stents for treatment of postoperative biliary strictures: long-term outcome in 25 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997;169(6):1517–22. doi: 10.2214/ajr.169.6.9393155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu KM, Lai EC. Expandable metallic biliary stents. Aust N Z J Surg. 1994;64(12):836–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1994.tb04559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eickhoff A, Jakobs R, Leonhardt A, Eickhoff JC, Riemann JF. Self-expandable metal mesh stents for common bile duct stenosis in chronic pancreatitis: retrospective evaluation of long-term follow-up and clinical outcome pilot study. Z Gastroenterol. 2003;41(7):649–54. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-40548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foerster EC, Hoepffner N, Domschke W. Bridging of benign choledochal stenoses by endoscopic retrograde implantation of mesh stents. Endoscopy. 1991;23(3):133–5. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1010639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hausegger KA, Kugler C, Uggowitzer M, Lammer J, Karaic R, Klein GE. et al. Benign biliary obstruction: is treatment with the Wallstent advisable? Radiology. 1996;200(2):437–41. doi: 10.1148/radiology.200.2.8685339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivancev K, Petersen B, Hall L, Ho P, Benner K, Rosch J. Percutaneous hepaticoneojejunostomy and choledochocholedochal reanastomosis using metallic stents: technical note. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 1992;15(4):256–60. doi: 10.1007/BF02733935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahl S, Zimmermann S, Glasbrenner B, Pross M, Schulz HU, McNamara D. et al. Treatment of benign biliary strictures in chronic pancreatitis by self-expandable metal stents. Dig Dis. 2002;20(2):199–203. doi: 10.1159/000067487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccioni F, Rossi M, Salvatori FM, Ricci P, Bezzi M, Rossi P. Metallic stents in benign biliary strictures: three-year follow-up. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 1992;15(6):360–6. doi: 10.1007/BF02734119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mygind T, Hennild V. Expandable metallic endoprostheses for biliary obstruction. Acta Radiol. 1993;34(3):252–7. doi: 10.3109/02841859309175363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien SM, Hatfield AR, Craig PI, Williams SP. A 5-year follow-up of self-expanding metal stents in the endoscopic management of patients with benign bile duct strictures. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;10(2):141–5. doi: 10.1097/00042737-199802000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieber A, Brambs HJ, Lauchart W. The radiological management of biliary complications following liver transplantation. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 1996;19(4):242–7. doi: 10.1007/BF02577643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roumilhac D, Poyet G, Sergent G, Declerck N, Karoui M, Mathurin P. et al. Long-term results of percutaneous management for anastomotic biliary stricture after orthotopic liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2003;9(4):394–400. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2003.50052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tesdal IK, Adamus R, Poeckler C, Koepke J, Jaschke W, Georgi M. Therapy for biliary stenoses and occlusions with use of three different metallic stents: single-center experience. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1997;8(5):869–79. doi: 10.1016/S1051-0443(97)70676-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Berkel AM, Cahen DL, van Westerloo DJ, Rauws EA, Huibregtse K, Bruno MJ. Self-expanding metal stents in benign biliary strictures due to chronic pancreatitis. Endoscopy. 2004;36(5):381–4. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-814319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi T, Ishihara T, Seza K, Nakagawa A, Sudo K, Tawada K. et al. Long-term outcome of endoscopic metallic stenting for benign biliary stenosis associated with chronic pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12(3):426–30. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i3.426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalano MF, Linder JD, George S, Alcocer E, Geenen JE. Treatment of symptomatic distal common bile duct stenosis secondary to chronic pancreatitis: comparison of single vs. multiple simultaneous stents. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60(6):945–52. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5107(04)02275-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Berkel AM, Cahen DL, van Westerloo DJ, Rauws EA, Huibregtse K, Bruno MJ. Self-expanding metal stents in benign biliary strictures due to chronic pancreatitis. Endoscopy. 2004;36(5):381–4. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-814319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantu P, Hookey LC, Morales A, Le MO, Deviere J. The treatment of patients with symptomatic common bile duct stenosis secondary to chronic pancreatitis using partially covered metal stents: a pilot study. Endoscopy. 2005;37(8):735–9. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-870130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witt H, Apte MV, Keim V, Wilson JS. Chronic pancreatitis: challenges and advances in pathogenesis, genetics, diagnosis, and therapy. Gastroenterology. 2007;132(4):1557–73. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trentino P, Falasco G, d'orta C, Coda S. Endoscopic removal of a metallic biliary stent: case report. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59(2):321–3. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5107(03)02685-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahaleh M, Behm B, Clarke BW, Brock A, Shami VM, De La Rue SA. et al. Temporary placement of covered self-expandable metal stents in benign biliary strictures: a new paradigm? (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67(3):446–54. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.06.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coene PP, Groen AK, Cheng J, Out MM, Tytgat GN, Huibregtse K. Clogging of biliary endoprostheses: a new perspective. Gut. 1990;31(8):913–7. doi: 10.1136/gut.31.8.913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speer AG, Cotton PB, MacRae KD. Endoscopic management of malignant biliary obstruction: stents of 10 French gauge are preferable to stents of 8 French gauge. Gastrointest Endosc. 1988;34(5):412–7. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5107(88)71407-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Berkel AM, van MJ, van VH, Groen AK, Huibregtse K. A scanning electron microscopic study of biliary stent materials. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;51(1):19–22. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5107(00)70380-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tringali A, Mutignani M, Perri V, Zuccala G, Cipolletta L, Bianco MA. et al. A prospective, randomized multicenter trial comparing DoubleLayer and polyethylene stents for malignant distal common bile duct strictures. Endoscopy. 2003;35(12):992–7. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-44601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]