Abstract

Background

To advance the field of disability assessment, additional developmental work is needed. The objective of this study was to determine the potential value of participant recall when evaluating disability over discrete periods of time.

Methods

We studied 491 residents of greater New Haven, Connecticut who were aged 76 years or older. Participants completed a comprehensive assessment that included several new questions on disability in four essential activities of daily living (bathing, dressing, transferring, and walking). Participants were also assessed for disability in the same activities during monthly telephone interviews before and after the comprehensive assessment. Chronic disability was defined as a new disability that was present for at least three consecutive months.

Results

We found that up to half of the incident disability episodes, which would otherwise have been missed, can be ascertained if participants are asked to recall whether they have had disability “at any time” since the prior assessment; that these disability episodes, which are ascertained by participant recall, confer high risk for the subsequent development of chronic disability, with an adjusted hazard ratio of 2.5 (95% confidence interval: 1.1, 5.8); and that participant recall for the absence of disability becomes increasingly inaccurate as the duration of the assessment interval increases, with 2.2%, 6.0%, 6.9% and 9.1% of participants having inaccurate recall at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months, respectively.

Conclusions

Our results demonstrate both the promise and limitations of participant recall and suggest that additional strategies are needed to more completely and accurately ascertain the occurrence of disability among older persons.

INTRODUCTION

In most longitudinal studies, the frame of reference for assessing disability in activities of daily living, such as bathing, dressing, and walking, is “at the present time”, and an incident episode of disability is noted when a nondisabled person reports disability at a subsequent follow-up interview (1). As shown in an earlier report (2), however, incident episodes of disability are often not ascertained by longitudinal studies with assessment intervals longer than three to six months. In an accompaning editorial (3), Guralnik and Ferrucci called for additional developmental work to help advance the field of disability assessment.

An alternative strategy for ascertaining incident episodes of disability is to ask participants to recall whether they have had disability “at any time” since the prior assessment. In the current study, we set out to determine the potential value of participant recall when evaluating disability over discrete periods of time. We used data from a unique longitudinal study that includes monthly assessments of disability in activities of daily living on a large cohort of older persons (2,4).

METHODS

Study population

Participants were members of the Precipitating Events Project, an ongoing longitudinal study of 754 community-living persons, aged 70 years or older, who were initially nondisabled in four essential activities of daily living—bathing, dressing, transferring, and walking (5). The assembly of the cohort has been described in detail elsewhere (5). Among the 1002 persons who were eligible, 75.2% agreed to participate. Participants have completed comprehensive assessments at 18-month intervals and have been interviewed monthly over the phone for the ascertainment of disability, with nearly 100% completion (6). The study protocol was approved by the Human Investigation Committee, and all participants provided verbal informed consent.

The analytic sample for the current study included participants who completed the comprehensive assessment at 72 months, which included several new questions on disability (as described below). Of the 754 participants, 231 (30.6%) had died prior to the 72-month assessment and 27 (3.6%) had dropped out of the study after a median follow-up of 27 months. Of the remaining 496 participants, 3 (0.6%) refused to complete the assessment and 2 (0.4%) had incomplete information on disability, leaving 491 participants in the analytic sample. Compared with these participants, the 263 cohort members who were not included in the analytic sample were (at baseline) older (80.0 vs. 77.5 years; P < 0.001), had more chronic conditions (2.1 vs. 1.6; P < 0.001), and were more likely to be physically frail (59.3% vs. 40.7%; P < 0.001). There were no significant baseline differences according to gender, race/ethnicity, living situation, education, or cognitive status.

Data collection

The research nurses who completed the 72-month assessments were kept blinded to the results of the monthly assessments. As described previously (2,5), the comprehensive assessments and monthly interviews were completed with a designated proxy for participants who had marked cognitive impairment.

Monthly telephone interviews

During the monthly interviews, participants were assessed for disability using a set of standard questions that were identical to those used during the comprehensive assessments (2). The stem of each question was, “At the present time, do you need help from another person to (complete the task)?” Response options included “No”, “Yes”, and “Unable to do”. The specific wording for each of the four tasks was, “to bathe (wash and dry your whole body)”, “to dress (like putting on a shirt or shoes, buttoning and zipping)”, “to get in and out of a chair”, and “to walk around your home or apartment”, respectively. Participants who needed help with (or were unable to do) any of the tasks were considered to be disabled. Participants were not asked about eating, toileting, or grooming. Disability in these activities of daily living is uncommon in the absence of disability in bathing, dressing, transferring, or walking (7–9). The reliability of our disability assessment was substantial (kappa=0.75) for reassessments completed within 48 hours and excellent (kappa=1.0) for reassessments performed the same day (2). The accuracy of proxy reports, as compared with reports from cognitively intact participants, was also found to be excellent, with kappa=1.0 (2).

72-month assessment

During the 72-month assessment, data were collected on living situation, ten self-reported, physician-diagnosed chronic conditions (5), cognitive status as assessed by the Folstein Mini-Mental State Exam (10), and physical frailty, as denoted by a timed score of greater than 10 seconds on the rapid gait test (i.e. walk back and forth over a 10-foot course as quickly as possible) (7,8,11). Cognitive impairment was defined as a score of less than 24 on the Mini-Mental State Exam (10).

To address the specific aim of the current study, several new questions, which had not been included in the prior assessments, were added. For each of the four essential activities of daily living, participants who did not need help from another person “at the present time” were asked (as indicated) to recall whether they needed help from another person to (complete the relevant task) “at any time” during the last month, 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months, respectively. Participants were not asked these questions if they needed help “at the present time” since they would have needed help, by definition, “at any time” during each of the four time intervals. Participants who needed help during an earlier time interval were not asked about subsequent intervals for the same reason.

Statistical analysis

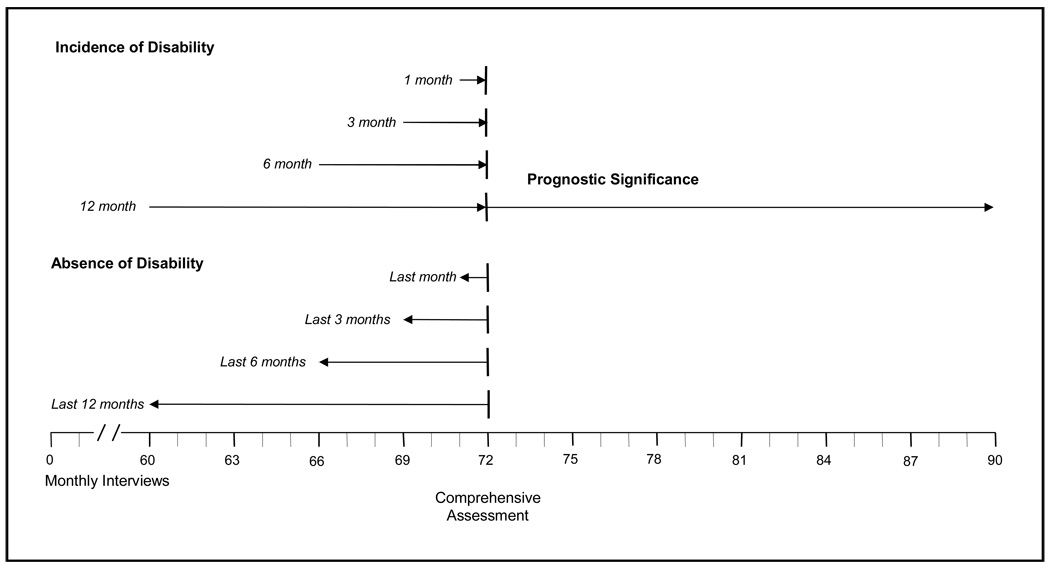

To determine the potential value of participant recall when evaluating disability over discrete periods of time, we performed three sets of analyses. First, we evaluated how often incident episodes of disability, which are missed when disability is assessed “at the present time” (i.e. the usual strategy), can be ascertained if participants are asked to recall whether they have had disability “at any time” since the prior assessment (i.e. the alternative strategy), i.e. during the last month, 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months, respectively. Second, we evaluated the prognostic significance of these incident disability episodes that are ascertained by participant recall, but not by the usual strategy. Third, we evaluated whether older persons can accurately recall the absence of disability over discrete periods of time. Figure 1 provides a schematic diagram for the three sets of analyses, which are described in detail below. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC); and all tests of statistical significance were two-sided.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram for the three sets of analyses. Participants completed a comprehensive assessment at 72 months, which included several new questions on disability in four essential activities of daily living, and were assessed for disability in the same activities during monthly interviews both before and after the comprehensive assessment. For each set of analyses, the arrows denote the direction of follow-up.

Incidence of Disability

Using data from the monthly interviews, we identified participants who were nondisabled at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months prior to the 72-month assessment, respectively. The corresponding time windows for these “zero-time” assessments of disability were operationalized as 27 – 33 (i.e. 30 ± 3), 86 – 96 (91 ± 5), 172 – 192 (182 ± 10), and 350 – 380 (365 ± 15) days prior to the 72-month assessment. For each of the four time intervals (i.e. 1, 3, 6, and 12 months), we determined the incidence of disability, as ascertained at the 72-month assessment, based first on disability “at the present time”, and second on recall of disability “at any time” since the zero-time assessment. To illustrate, for the 6-month interval, we identified 261 participants who were nondisabled during the monthly interview that was completed 172 to 192 days prior to the 72-month assessment. We then determined the number (%) of these participants who reported at the 72-month assessment that they had disability at the present time and (among the remainder) had disability at any time during the past 6 months. Participants who did not have a monthly interview during the relevant time window were excluded. Our results did not change appreciably after the participants who had proxy assessments at 72 months were omitted from the analysis. We considered using the responses from the monthly interviews to determine the validity of participant recall for disability at any time during the relevant time intervals, but our preliminary analyses revealed that the duration of many of the disability episodes was short relative to the duration of the intervals, indicating that the monthly interviews, which assessed disability at the present time, would make a poor gold standard.

Prognostic Significance

For this set of analyses, we focused on the 12-month time interval since it provided the largest number of participants, thereby enhancing power. Of the 373 participants who were nondisabled during the monthly interview that was completed 12 months prior to the 72-month assessment, 320 had no disability “at the present time” during the 72-month assessment, which served here as zero-time, the time at which prognostic estimations are made (12). Among these participants, who did not have incident disability according to the usual strategy, we compared the time to onset (in days) of chronic disability, defined as a new disability that was present for at least three consecutive months, using data from the monthly interviews (13), between those who reported (i.e. recalled) disability at any time during the past 12 months and those who did not. We chose chronic disability as the primary outcome because it is clinically meaningful (4) and often used to forecast the demand for long-term care services (14–16).

The primary analytic technique was survival analysis; participants were followed for an additional 18 months, i.e. until the next comprehensive assessment at 90 months. The Kaplan-Meier method was used for the unadjusted analysis (17), while the Cox proportional hazards method was used for the multivariable analysis. As in a prior report (18), the covariates for the multivariable analysis included sex (female vs. male), race/ethnicity (Non-Hispanic white vs. other), living situation (alone vs. with others), cognitive impairment (yes vs. no), and physical frailty (yes vs. no), which were each analyzed as a dichotomous variable that was coded as 1 vs. 0, and age, years of education and number of chronic conditions, which were each analyzed as a continuous variable. These factors, most notably slow gait speed (i.e. physical frailty) and cognitive impairment, have been most strongly associated with the development of disability in prior studies (7,19–22). Data on participants without chronic disability were censored at the time of death (n=15) or the last completed interview prior to the end of the follow-up period. Data on disability were available for 99.9% of the 5,509 monthly interviews subsequent to zero-time.

Absence of Disability

Participants were included in these analyses if they reported at the 72-month assessment that they had no disability at the present time and during the relevant time interval (i.e. last month, 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months). For each of the four time intervals, we determined the number (%) of participants who incorrectly recalled having no disability, using data from the monthly interviews as the “gold” standard. To illustrate, recall was considered inaccurate if the participant reported (during the 72-month assessment) no disability at any time during the last month, but had previously reported disability during the telephone interview that was completed within the last month. Telephone interviews completed within 30, 91, 182, and 365 days were considered for each of the four time intervals, respectively.

Among the 338 participants who were classified as not disabled at 72 months, only 16 (4.7%) of the comprehensive assessments were completed by a proxy, and only 96 (2.3%) of the monthly interviews in the year prior to the 72-month assessment were completed by a proxy. Our results did not change appreciably after the 16 participants who had proxy assessments at 72 months were omitted from the analysis.

RESULTS

The characteristics of the participants, at the time of the 72-month assessment, are shown in Table 1. The majority of participants were female, white, and did not live alone; and about half were physically frail. There was a wide range of ages, education, and scores on the Mini-Mental State Exam, although the majority of participants completed high school and were cognitively intact. The most common chronic conditions were hypertension and arthritis. Disability was reported “at the present time” by 153 (31.2%) of the participants.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Participants at 72 Months

| Characteristic* | N=491 |

|---|---|

| Age, years | |

| Median | 83 |

| Range | 77 – 103 |

| Female | 325 (66.2) |

| Non-Hispanic white | 439 (88.4) |

| Lives alone | 192 (39.1) |

| Education†, years | |

| Median | 12 |

| Range | 0 – 17 |

| Chronic conditions‡ | |

| Hypertension | 319 (65.0) |

| Arthritis | 255 (51.9) |

| Cancer | 112 (22.8) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 96 (19.6) |

| Chronic lung disease | 96 (19.6) |

| Myocardial infarction | 89 (18.3) |

| Stroke | 61 (12.4) |

| Fractures other than hip since age 50 | 57 (11.6) |

| Congestive heart failure | 42 (8.6) |

| Hip fracture | 40 (8.2) |

| Mini-Mental State Exam Score | |

| Median | 26 |

| Range | 0 – 30 |

| Physical frailty§ | 227 (46.5) |

| Disability at present time | 153 (31.2) |

Data are presented as No. (%) unless otherwise indicated.

17 years denotes postgraduate education.

Presented in descending order according to prevalence.

As defined in the Methods.

Table 2 shows the incidence of disability in activities of daily living for the four time intervals according to how disability was ascertained at the 72-month assessment. Of the 89 participants who were nondisabled 1 month (i.e. 27 to 33 days) prior to the 72-month assessment, 6 (6.7%) reported disability at the present time at the 72-month assessment, and 1 (who was nondisabled at the present time) reported disability at any time during the month preceding the 72-month assessment. As expected, the incidence of disability at the present time increased as the duration of the interval preceding the 72-month assessment increased, from 6.7% for 1 month to 14.2% for 12 months. Similarly, the incidence of disability based on recall, i.e. “at any time during interval”, increased progressively as the duration of the interval preceding the 72-month assessment increased, from 1.1% for 1 month to 12.9% for 12 months, so that nearly half (48/101 or 47.5%) of the participants with incident disability for the 12-month interval were ascertained by “at any time during interval”.

Table 2.

Incidence of Disability in Activities of Daily Living

| Interval prior to 72-month assessment* |

Number of participants nondisabled at start of interval† |

Ascertainment of disability at 72-month assessment‡ |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| At present time |

At any time during interval§ |

Total | |||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | ||

| 1 month | 89 | 6 | 6.7 | 1 | 1.1 | 7 | 7.9 |

| 3 months | 133 | 13 | 9.8 | 7 | 5.3 | 20 | 15.0 |

| 6 months | 261 | 36 | 13.8 | 16 | 6.1 | 52 | 19.9 |

| 12 months | 373 | 53 | 14.2 | 48 | 12.9 | 101 | 27.1 |

As described in the text, the corresponding time windows for the zero-time assessments of disability were operationalized as 27 – 33, 86 – 96, 172 – 192, and 350 – 380 days prior to the 72-month assessment. Time windows are wider for longer intervals than for shorter intervals to accommodate likely reductions in precision when recalling more distant events.

Participants were included only if they had a monthly interview during the corresponding time window. As the duration of the time window increased, the number of participants increased, reflecting the greater opportunity for interviews to have been completed within the wider time windows.

The denominator for these rates included participants who were nondisabled at the start of the relevant interval.

Participants were asked to recall the occurrence of disability during the relevant interval only if they were not disabled at the present time.

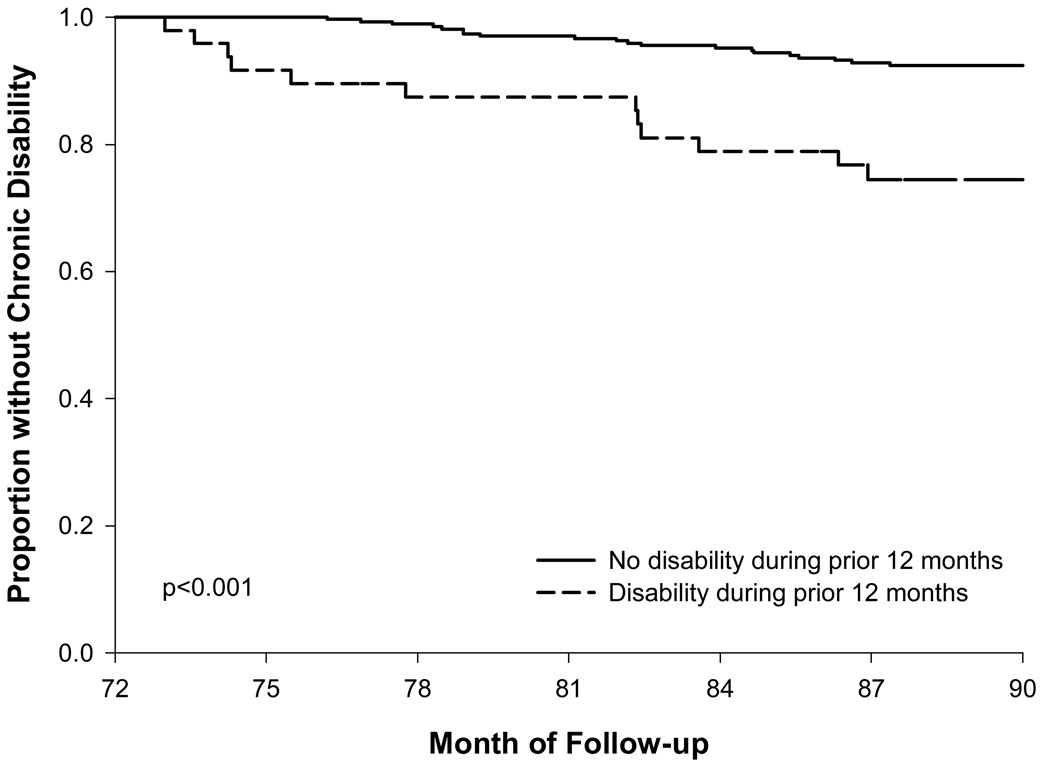

Figure 2 provides Kaplan-Meier curves for the development of chronic disability according to whether participants, who were nondisabled at the 72-month assessment, reported (i.e. recalled) disability at any time during the 12 months prior to the 72-month assessment. Higher rates of chronic disability were observed for participants who reported disability at any time during the prior 12 months than for those who did not. In the fully adjusted Cox proportional hazards model, reporting disability at any time during the prior 12 months was significantly associated with the development of chronic disability, with a hazard ratio of 2.5 (95% confidence interval: 1.1, 5.8).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curves for the development of chronic disability according to whether participants, who were nondisabled at the 72-month assessment, reported disability at any time during the 12 months prior to the 72-month assessment. These reports were based on participant recall during the 72-month assessment, as described in the text. There were 272 participants with no disability and 48 participants with disability during the prior 12 months. The Log-rank test was used for statistical comparisons.

Table 3 provides the number (%) of participants who incorrectly recalled having no disability for each of the four time intervals prior to the 72-month assessment. As the duration of the interval increased, the percentage of participants with inaccurate recall increased in a graded manner, from 2.2% for 1 month to 9.4% for 12 months.

Table 3.

Number and Percentage of Participants with Inaccurate Recall for the Absence of Disability Over Discrete Periods of Time*

| Interval prior to 72-month assessment |

Number of participants with no disability at 72 months and during preceding interval |

Number of participants with inaccurate recall |

Percentage of participants with inaccurate recall |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 month | 318 | 7 | 2.2 |

| 3 months | 317 | 19 | 6.0 |

| 6 months | 303 | 21 | 6.9 |

| 12 months | 286 | 27 | 9.4 |

As determined during the 72-month assessment. The monthly telephone interviews served as the “gold standard”, as described in the text.

DISCUSSION

We have previously demonstrated that disability among older persons is a complex and highly dynamic process, characterized by frequent transitions between states of independence and disability (4,6,23,24). The inherent complexity of disability has historically not been well appreciated or understood, largely because prior longitudinal studies have almost invariably included long intervals, ranging from six months to six years, between disability assessments (7,25–34). The availability of monthly data has allowed us to evaluate questions about the assessment of disability that cannot be easily addressed by other epidemiologic studies (2,13,18,35).

The objective of the current study was to determine the potential value of participant recall when evaluating disability over discrete periods of time. We found that up to half of the incident disability episodes, which would otherwise have been missed, can be ascertained if participants are asked to recall whether they have had disability “at any time” since the prior assessment; that these disability episodes, which are ascertained only by participant recall, confer high risk for the subsequent development of chronic disability, even after accounting for potential confounders; and that participant recall for the absence of disability becomes increasingly inaccurate as the duration of the assessment interval increases. These results demonstrate both the promise and limitations of participant recall and suggest that additional strategies are needed to more completely and accurately ascertain the occurrence of disability among older persons.

In most longitudinal studies, the occurrence of a specific event, such as a myocardial infarction, is ascertained by asking participants to recall whether they have experienced the event since their last interview. For disease-specific events, these reports can often be confirmed through review of medical records. In contrast, an incident episode of disability is usually noted when a nondisabled person reports disability “at the present time” during a subsequent follow-up assessment (1). When we asked nondisabled participants whether they had experienced disability at any time over four discrete intervals, we found that the percentage of participants with inaccurate recall was low for 1-month intervals (i.e. about 2%), but increased progressively over longer intervals, such that nearly 10% of known disability episodes were not recalled over the course of 12 months, which is a common assessment interval for studies of disability. Even over the course of only 3 months, the percentage of participants with inaccurate recall was 6.0. These values are likely conservative for two reasons. First, because the study participants had been answering questions about disability every month for six years, they may have been more likely to recall prior episodes of disability. Second, because the “gold” standard was based on disability at the present time, as ascertained during the monthly interviews, episodes of disability occurring between the monthly interviews may have been missed. For this reason, we could not formally evaluate whether older persons can accurately recall the presence of disability over discrete periods of time.

Nonetheless, we found that participants often recalled episodes of disability that would not have otherwise been ascertained by the usual strategy of asking about disability “at the present time”. The ascertainment of disability by participant recall was substantial, representing about a third of the incident episodes at 3 and 6 months and nearly half at 12 months. These values are likely underestimates since participants who needed help during an earlier time interval were not asked about and, hence, were not included in the analyses of subsequent intervals. The current study provides strong evidence that ascertaining these incident episodes of disability is clinically important since they confer more than a 2-fold adjusted elevation in risk for the development of chronic disability, a major determinant for the use of long-term care services (14–16). Although an extended discussion is beyond the scope of the current manuscript, there may be circumstances when assessing disability at the present time is indicated, e.g. when the goal is to establish temporal precedence between a time-varying exposure and the onset of disability (36).

The assessment of disability poses many challenges, including the reliance on self-reported information (37). While we have previously demonstrated that our monthly assessments of disability are highly reliable and accurate (2), we did not formally evaluate the reliability of the questions that were added to our disability assessment at 72 months. We have previously reported, however, that the inter-rater reliability for our assessment of disability lasting at least 90 days, which used a similar set of procedures, was high (13). In the current study, our results did not change appreciably after participants who had proxy assessments of disability were omitted.

Our assessment of disability did not include eating, toileting or grooming. While these omissions could lead to an underestimate of disability severity, they would have had relatively little effect on our ascertainment of disability. Our participants included nondecedents who completed the comprehensive assessment at 72 months. While the use of a “residual” cohort could affect the generalizability of our findings, it is unlikely to threaten their validity. Generalizability is enhanced by low attrition for reasons other than death and the completeness of follow-up for disability, as assessed during the monthly interviews (38).

Our results raise important questions about the assessment of disability, which for most older persons is a reversible event, more similar to falls and delirium than to progressive disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease. In their editorial, Guralnik and Ferrucci suggested that an assessment interval of six months may be sufficient (3). Based on our results, the ascertainment of disability would be more complete if older persons were asked to recall whether they had disability at any time since the last assessment. Given the complexity and recurrent nature of disability, additional developmental work is greatly needed to more accurately ascertain the onset and duration of disability among older persons.

Acknowledgments

We thank Denise Shepard, BSN, MBA, Andrea Benjamin, BSN, Paula Clark, RN, Shirley Hannan, RN, Barbara Foster, Alice Van Wie, BSW, Patricia Fugal, BS, and Amy Shelton, MPH for assistance with data collection; Wanda Carr and Geraldine Hawthorne for assistance with data entry and management; Peter Charpentier, MPH for development of the participant tracking system; Linda Leo-Summers, MPH for assistance with Figure 1 and Figure 2; and Joanne McGloin, MDiv, MBA for leadership and advice as the Project Director.

Funding/Support:

The work for this report was funded by grants from the National Institute on Aging (R37AG17560, R01AG022993). The study was conducted at the Yale Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center (P30AG21342). Dr. Gill is the recipient of a Midcareer Investigator Award in Patient-Oriented Research (K24AG021507) from the National Institute on Aging.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wiener JM, Hanley RJ, Clark R, Van Nostrand JF. Measuring the activities of daily living: comparisons across national surveys. J Gerontol. 1990;45:S229–S237. doi: 10.1093/geronj/45.6.s229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gill TM, Hardy SE, Williams CS. Underestimation of disability among community-living older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:1492–1497. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L. Underestimation of disability occurrence in epidemiological studies of older persons: is research on disability still alive? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:1599–1601. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hardy SE, Gill TM. Recovery from disability among community-dwelling older persons. JAMA. 2004;291:1596–1602. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.13.1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gill TM, Desai MM, Gahbauer EA, Holford TR, Williams CS. Restricted activity among community-living older persons: incidence, precipitants, and health care utilization. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:313–321. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-5-200109040-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hardy SE, Dubin JA, Holford TR, Gill TM. Transitions between states of disability and independence among older persons. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;161:575–584. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gill TM, Williams CS, Tinetti ME. Assessing risk for the onset of functional dependence among older adults: the role of physical performance. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1995;43:603–609. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1995.tb07192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gill TM, Richardson ED, Tinetti ME. Evaluating the risk of dependence in activities of daily living among community-living older adults with mild to moderate cognitive impairment. J Gerontol Med Sci. 1995;50A:M235–M241. doi: 10.1093/gerona/50a.5.m235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rodgers W, Miller B. A comparative analysis of ADL questions in surveys of older people. J Gerontol Psychol Sci. 1997;52 Spec No:21–36. doi: 10.1093/geronb/52b.special_issue.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state.” A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gill TM, Allore H, Holford TR, Guo Z. The development of insidious disability in activities of daily living among community-living older persons. Am J Med. 2004;117:484–491. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feinstein AR, editor. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 1985. Clinical epidemiology: the architecture of clinical research. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gill TM, Gahbauer EA. Overestimation of chronic disability among elderly persons. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:2625–2630. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.22.2625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spillman BC, Kemper P. Lifetime patterns of payment for nursing home care. Med Care. 1995;33:280–296. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199503000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fried TR, Bradley EH, Williams CS, Tinetti ME. Functional disability and health care expenditures for older persons. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:2602–2607. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.21.2602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guralnik JM, Alecxih L, Branch LG, Wiener JM. Medical and long-term care costs when older persons become more dependent. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:1244–1245. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.8.1244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaplan EL, Meier PM. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Soc. 1958;53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gill TM, Kurland BF. Prognostic effect of prior disability episodes among nondisabled community-living older persons. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;158:1090–1096. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Pieper CF, et al. Lower extremity function and subsequent disability: consistency across studies, predictive models, and value of gait speed alone compared with the short physical performance battery. J Gerontol Med Sci. 2000;55A:M221–M231. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.4.m221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Studenski S, Perera S, Wallace D, et al. Physical performance measures in the clinical setting. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:314–322. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gill TM, Williams CS, Richardson ED, Tinetti ME. Impairments in physical performance and cognitive status as predisposing factors for functional dependence among nondisabled older persons. J Gerontol Med Sci. 1996;51A:M283–M288. doi: 10.1093/gerona/51a.6.m283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stuck AE, Walthert JM, Nikolaus T, Bula CJ, Hohmann C, Beck JC. Risk factors for functional status decline in community-living elderly people: a systematic literature review. Soc Sci Med. 1999;48:445–469. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00370-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gill TM, Kurland B. The burden and patterns of disability in activities of daily living among community-living older persons. J Gerontol Med Sci. 2003;58:70–75. doi: 10.1093/gerona/58.1.m70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gill TM, Allore HG, Hardy SE, Guo Z. The dynamic nature of mobility disability in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:248–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guralnik JM, Fried LP, Simonsick EM, Kasper JD, Lafferty ME, editors. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Aging; 1995. NIH Pub. No. 95-4009); 1995. The Women’s Health and Aging Study: Health and Social Characteristics of Older Women with Disability. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Strawbridge WJ, Kaplan GA, Camacho T, Cohen RD. The dynamics of disability and functional change in an elderly cohort: results from the Alameda County Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40:799–806. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb01852.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beckett LA, Brock DB, Lemke JH, et al. Analysis of change in self-reported physical function among older persons in four population studies. Am J Epidemiol. 1996;143:766–778. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a008814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Katz S, Branch LG, Branson MH, Papsidero JA, Beck JC, Greer DS. Active life expectancy. N Engl J Med. 1983;309:1218–1224. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198311173092005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chaves PH, Garrett ES, Fried LP. Predicting the risk of mobility difficulty in older women with screening nomograms: the Women’s Health and Aging Study II. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:2525–2533. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.16.2525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crimmins EM, Saito Y, Reynolds SL. Further evidence on recent trends in the prevalence and incidence of disability among older Americans from two sources: the LSOA and the NHIS. J Gerontol Soc Sci. 1997;52B:S59–S71. doi: 10.1093/geronb/52b.2.s59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seeman TE, Bruce ML, McAvay GJ. Social network characteristics and onset of ADL disability: MacArthur studies of successful aging. J Gerontol Soc Sci. 1996;51B:S191–S200. doi: 10.1093/geronb/51b.4.s191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vita AJ, Terry RB, Hubert HB, Fries JF. Aging, health risks, and cumulative disability. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1035–1041. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199804093381506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clark DO, Stump TE, Hui SL. Predictors of mobility and basic ADL difficulty among adults aged 70 years and older. J Aging Health. 1998;10:422–440. doi: 10.1177/089826439801000402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Greiner PA, Snowdon DA, Schmitt FA. The loss of independence in activities of daily living: the role of low normal cognitive function in elderly nuns. Am J Public Health. 1996;86:62–66. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.1.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gill TM, Allore H, Hardy SE, Holford TR, Han L. Estimates of active and disabled life expectancy based on different assessment intervals. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60:1013–1016. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.8.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gill TM, Allore HG, Holford TR, Guo Z. Hospitalization, restricted activity, and the development of disability among older persons. JAMA. 2004;292:2115–2124. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.17.2115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ferrucci L, Guralnik JM, Studenski S, et al. Designing randomized, controlled trials aimed at preventing or delaying functional decline and disability in frail, older persons: a consensus report. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:625–634. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Szklo M. Population-based cohort studies. Epidemiol Rev. 1998;20:81–90. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a017974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]