Abstract

Chemopreventive effects and associated mechanisms of grape seed extract (GSE) against intestinal/colon cancer development are largely unknown. Herein, we investigated GSE efficacy against intestinal tumorigenesis in APCmin/+ mice. Female APCmin/+ mice were fed control or 0.5% GSE (wt/wt) mixed AIN-76A diet for 6 weeks. At the end of the experiment, GSE feeding decreased the total number of intestinal polyps by 40%. The decrease in polyp formation in the small intestine was 42%, which was mostly in its middle (51%) and distal (49%) portions compared with the proximal one. GSE also decreased polyp growth where the number of polyps of 1 to 2 mm in size decreased by 42% and greater than 2 mm in size by 71%, without any significant change in polyps less than 1 mm in size. Immunohistochemical analyses of small intestinal tissue samples revealed a decrease (80%–86%) in cell proliferation and an increase (four- to eight-fold) in apoptosis. GSE feeding also showed decreased protein levels of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) (56%–64%), inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) (58%–60%), and β-catenin (43%–59%) but an increased Cip1/p21-positive cells (1.9- to 2.6-fold). GSE also decreased cyclin D1 and c-Myc protein levels in small intestine. Together, these findings show the chemopreventive potential of GSE against intestinal polyp formation and growth in APCmin/+ mice, which was accompanied with reduced cell proliferation and increased apoptosis together with down-regulation in COX-2, iNOS, β-catenin, cyclin D1, and c-Myc expression, but increased Cip1/p21. In conclusion, the present study suggests potential usefulness of GSE for the chemoprevention of human intestinal/colorectal cancer.

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC), which often results from a combination of genetic predisposition and environmental factors, is a major cause of cancer-related deaths among both men and women in the United States [1]. Substantial evidence from epidemiological and experimental studies indicate that a Western-style diet, high in fat and red meat as well as diet low in fibers and vegetables, increases the risk of CRC [2,3]. Hence, identification of dietary constituents that prevent CRC is important and a major focus of research in recent years. Recently, there has been a keen interest in the protective and therapeutic effects of certain plant chemicals on chronic diseases including cancer. Especially, dietary phytochemicals that consist of a wide variety of biologically active compounds have drawn a great deal of attention from both the scientific community and the general public owing to their demonstrated ability to suppress cancers [4].

One such most notable agent is grape seed extract (GSE), which has shown promising chemopreventive and anticancer effects in various in vitro and in vivo models [5–8]. GSE is a complex mixture of various polyphenols that are generally referred to as proanthocyanidins and has long been marketed in the United States as a dietary supplement owing to multiple health benefits [9,10]. Grape seed proanthocyanidins have been demonstrated to exert a novel spectrum of biological, pharmacological, therapeutic, and chemoprotective properties against oxygen free radicals and oxidative stress [11,12]. In several continuing studies by us and others, GSE has been shown to reduce the incidence of carcinogen-induced mammary tumors in rats and skin tumors in mice and to inhibit the growth of different human cancer cells in vitro and in vivo [13–16]. A recent study from our laboratory has also demonstrated the inhibitory effect of GSE on prostate cancer growth and progression in the transgenic adenocarcinoma of the mouse prostate (TRAMP)model [17]. The aim of the present study was to investigate whether GSE exerts chemopreventive efficacy against the intestinal tumorigenesis in APCmin/+ mouse model.

APCmin/+ mice are considered as a genetically relevant animal model mimicking human intestinal carcinogenesis [18]. These mice carry a germ line nonsense mutation at codon 850 of the mouse homolog of the human adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene and spontaneously develop multiple polyps in the small and large intestines at the age of 10 to 12 weeks [19]. The APC gene is a tumor-suppressor gene, and its mutation has been directly implicated in the development of both human familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) and sporadic CRC [20]. Hence, APCmin/+ mice are considered an ideal experimental model for analysis and prevention of human CRC. Therefore, in this study, we used the APCmin/+ mice model to investigate the inhibitory activity of GSE against intestinal tumorigenesis and the possible mechanisms involved in the inhibitory action.

Materials and Methods

Animals and Treatment Protocol

Six-week-old female APCmin/+mice were purchased from the Jackson laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME) and maintained in the animal house facility at the University of Colorado Denver. Animals were maintained in 12-hour light/dark cycles with free access to water and food (AIN-76A powder diet from Dyets Inc., Bethlehem, PA). After 1 week of acclimatization, animals were randomly divided into two groups of eight animals each and fed AIN-76A control diet or 0.5% GSE (wt/wt) mixed in AIN-76A powder diet using a powder diet feeder, ad libitum for 6 weeks. GSE-standardized preparation, constituting of 89.3% (wt/wt) procyanidins, 6.6% of monomeric flavonols, 2.24% of moisture content, 1.06% of protein, and 0.8% of ash, was a kind gift from its commercial vendor Kikkoman Corp (Noda City, Japan). The animals were weighed weekly once and monitored regularly for any signs of weight loss. At 13 weeks of age, the animals were killed by CO2 followed by cervical dislocation; the intestine was spread onto filter paper, opened longitudinally with fine scissors, and cleaned with sterile ice-cold PBS using a soft brush. The small intestine was divided into three equal parts, namely proximal, middle, and distal, and the large intestine consisted of cecum and colon. All intestinal polyps were counted under a dissecting microscope, and their sizes were measured with a digital caliper.

Immunostaining for Proliferating Cell Nuclear Antigen, Cyclooxygenase-2, Nitric Oxide Synthase, β-Catenin, Cip1/p21, Cyclin D1, and c-Myc

Intestinal tissues were fixed in 10% phosphate-buffered formalin for 10 hours at 4°C, dehydrated in ascending concentrations of ethanol, cleared with xylene, and embedded in PolyFin (Triangle Biomedical Sciences, Durham, NC). Paraffin-embedded tissue blocks were cut with a rotary microtome into 4-µm sections and processed for immunohistochemical staining. Briefly, sections after deparaffinization and rehydration were treated with 0.01 M sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0) in a microwave for 30 minutes at full power for antigen-retrieval. Sections were then quenched of endogenous peroxidase activity by immersing in 3% hydrogen peroxide for 5 minutes at room temperature. The sections were either incubated with mouse monoclonal antiproliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) antibody (1:400 dilutions; Dako, Carpinteria, CA), rabbit polyclonal anti-cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) antibody (1:100 dilutions; Cell Signaling Technologies, San Diego, CA), rabbit polyclonal anti-nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) antibody (1:200 dilutions; Abcam, Inc, Cambridge, MA), rabbit polyclonal anti-β-catenin (1:100 dilutions; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA), rabbit polyclonal anti-Cip1/p21 antibody (1:100 dilutions; Lab Vision Corporation, Fremont, CA), cyclin D1 (1:200 dilutions; Neomarkers, CA), or c-Myc (1:100 dilutions; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) in PBS for 2 hours at room temperature in a humidity-controlled chamber followed by overnight incubation at 4°C. In all the immunohistochemical staining, to rule out the nonspecific staining allowing better interpretation of specific staining at the antigenic site, negatively staining controls were used in which sections were incubated with N-Universal Negative Control mouse or rabbit antibody (Dako) under identical conditions. The sections were then incubated with appropriate biotinylated secondary antibody for 1 hour at room temperature followed by a 30-minute incubation with HRP-conjugated streptavidin. Color development was performed by incubating with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine for 10 minutes at room temperature. The sections were counterstained with Harris hematoxylin, dehydrated, and mounted. The proliferation index was determined as the number of PCNA-positive cells x 100 / total number of cells. Levels of immunostaining of COX-2, iNOS, β-catenin, and c-Myc were quantified as 0, 1+, 2+, 3+, and 4+ representing nil, weak, moderate, strong, and very strong staining, respectively. Cip1/p21 and cyclin D1 were quantified by counting positively stained cells and total number of cells at 10 randomly selected fields from each section at 400x magnifications, and data were presented as percent positive cells.

Terminal Deoxynucleotidyl Transferase dUTP Nick End Labeling Staining for Apoptotic Cells

Apoptotic cells were detected using the Dead End Colorimetric terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) system (Promega, Madison, WI) following the manufacturer's protocol with some modifications. In brief, intestinal tissue sections after deparaffinization and rehydration were permeabilized with proteinase K (30 mg/ml) for 1 hour at 37°C. Thereafter, the sections were quenched of endogenous peroxidase activity using 3% hydrogen peroxide for 10 minutes. After thorough washing with 1x PBS, sections were incubated with equilibration buffer for 10 minutes, and then the terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase reaction mixture was added to the sections, except for the negative control, and incubated at 37°C for 1 hour. The reaction was stopped by immersing the sections in 2x saline-sodium citrate buffer for 15 minutes. Sections were then added with streptavidin-HRP (1:500) for 30 minutes at room temperature, and after repeated washings, sections were incubated with substrate 3,3′-diaminobenzidine until color development (∼10 minutes). Sections were then mounted after dehydration and observed under 400x magnifications for TUNEL-positive cells. The apoptotic index was calculated as number of apoptotic cells x 100 / total number of cells.

Immunohistochemical and Statistical Analyses

All the microscopic immunohistochemical analyses were done using Zeiss Axioscop 2microscope (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany). Pictures were taken by Kodak DC290 camera under 400x magnifications and processed by Kodak Microscopy Documentation System 290 (Eastman Kodak Company, Rochester, NY). The mean ± SE values were obtained from the evaluation of multiple fields in each group. For each animal, 10 representative fields were counted at 400x magnifications, and the data represent the results from eight mice in each group. For the statistical significance of the difference, the data were analyzed using the SigmaStat 2.03 software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL). The statistical significance of difference between control and GSE-treated group was determined by one-way analysis of variance followed by Student's t test. P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Dietary GSE Inhibits Multiplicity and Burden of Intestinal Polyps without Any Toxicity in APCmin/+ Mice

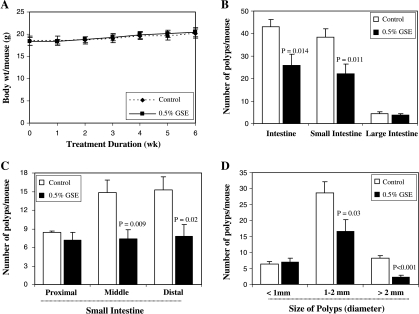

All mice were monitored on a regular basis to investigate if dietary GSE had any effect on body weight gain. Gain in body weights did not differ significantly among the control and GSE-fed groups until the end of the study (Figure 1A). Further, no considerable change in food consumption (g/day per mouse) or histopathologic alterations were found in any organs, including the liver, in mice due to GSE supplementation in diet (data not shown). APCmin/+ mice in the control group observed at 13 weeks of age developed an average of 43 intestinal tumors (polyps) per mouse, and most of these tumors were populated in the small intestine. Dietary feeding of 0.5% GSE for 6 weeks significantly reduced the number of total intestinal polyps by 40% (from 43 per mouse in control to 26 per mouse in GSE-fed group; P = .014). The prominent effect of GSE on the decrease in polyp formation was observed in small intestine (42% decrease, P = .011; Figure 1B). In particular, middle and distal portions of small intestine showed a 51% (P = .009) and 49% (P = .018) decrease in the number of polyps by GSE, respectively (Figure 1C). In size distribution analysis, GSE strongly decreased the number of large size polyps (≥2 mm in size by 71% [P < .001] and 1–2 mm in size by 42% [P = .03]), without any significant change in polyps of less than 1 mm in size (Figure 1D). These results indicate the inhibitory effect of GSE on polyp multiplicity and growth without any toxicity in APCmin/+ mice.

Figure 1.

Effect of dietary feeding of GSE on intestinal tumorigenesis in APCmin/+ mice. Dietary feeding of GSE in AIN-76A diet (A) does not affect body weight gain in APCmin/+ mice and (B) inhibits intestinal polyp formation (C) with the most prominent effect in middle and distal regions of small intestine. (D) GSE also decreases the number of larger polyps (>1 mm) indicating its growth-inhibitory effect on polyps in APCmin/+ mice.

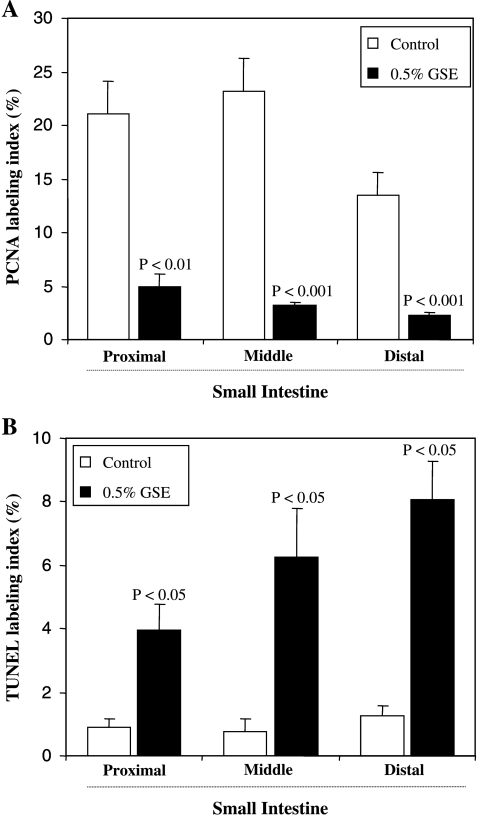

Effects of Dietary GSE on Intestinal PCNA Labeling Index and TUNEL-Positive Cells

To evaluate mechanisms involved in the chemopreventive ability of GSE, we initially assessed its effect on cell proliferation and apoptosis. The PCNA immunostaining and in situ apoptosis detection assays were performed in different portions (proximal, middle, and distal) of the small intestinal tissues from control and GSE-treated groups of mice. PCNA is an auxiliary protein of DNA polymerase-δ and its level of expression correlates cell with proliferation, and therefore, it is used as a marker of cell proliferation [26]. The quantification of PCNA immunohistochemical staining revealed that inhibition of polyp growth by GSE was associated with a strong decrease (80%–86%, P < .01 to P < .001) in cell proliferation in intestinal tissue (Figure 2A). In contrast, the apoptotic cells, as determined by TUNEL-positive cells, were significantly increased (four- to eight-fold, P < .05) in mice treated with 0.5% GSE compared with the control mice (Figure 2B). Overall, these results indicated the antiproliferative and proapoptotic effects of GSE in intestinal tissue, which may, in part, account for its inhibitory effects on polyp multiplicity and growth.

Figure 2.

Modulatory effects of dietary GSE on cell proliferation and apoptosis in intestinal epithelium of APCmin/+ mouse. The percent of (A) PCNA-positive cells and (B) TUNEL-positive cells assessed by quantification of immunohistochemically stained mouse intestinal epithelium in 10 randomly selected fields from each tissue sample are represented. Data are shown as mean ± SE of eight samples in each group.

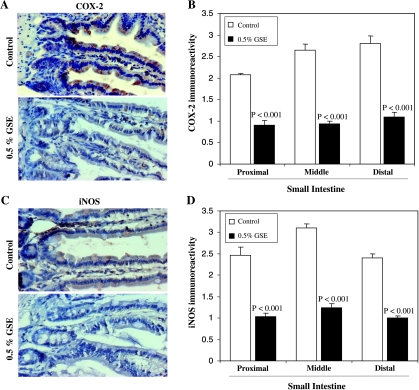

Effect of Dietary GSE on Intestinal COX-2 and iNOS Expression

Microscopic examination for COX-2 staining as shown in Figure 3A indicated a lower immunoreactivity in GSE-treated group. The quantification of immunostaining showed that GSE significantly decreased the expression of COX-2 in small intestine (proximal, middle, and distal portions) by 56% to 64% (P < .001) compared with the control group (Figure 3B). In association with the down-regulation of COX-2, the expression of iNOS in the small intestine was also inhibited by 58% to 60% (P <.001) in the GSE-fed group compared with the control group (Figure 3, C and D). These results suggest the down-regulation of COX-2 and iNOS by GSE in small intestine of APCmin/+ mice, which, in turn, could exert anti-inflammatory and antiproliferative effects to inhibit growth and development of polyps.

Figure 3.

Effects of dietary GSE on COX-2 and iNOS expression levels in intestinal tissues of APCmin/+ mice. Representative photographs for immunohistochemical staining of (A) COX-2 and (C) iNOS-stained cells in APCmin/+ mouse control and GSE-treated groups, respectively, are shown at 400x magnifications. (B) COX-2 and (D) iNOS expression levels were assessed by the quantification of the specific immunostaining of mouse intestinal epithelium in 10 randomly selected fields as described in Materials and Methods. Data are shown as mean ± SE of eight samples in each group.

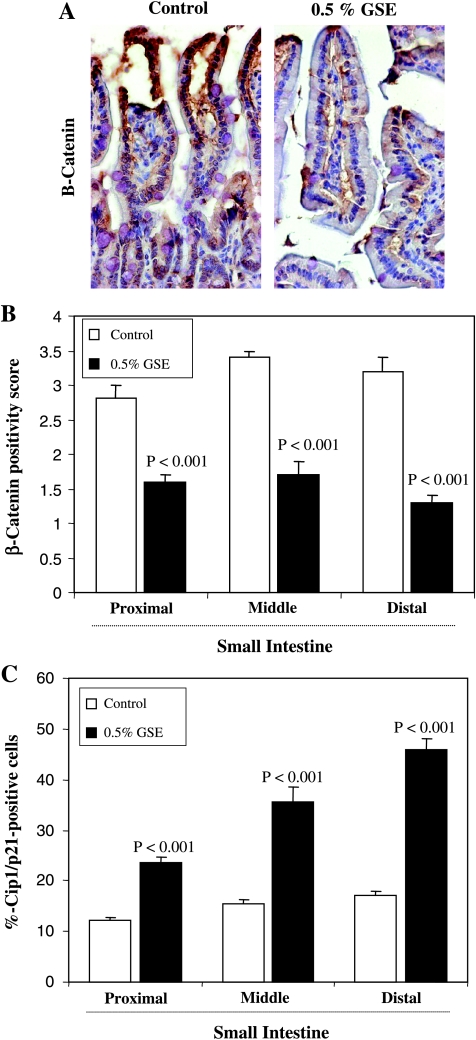

Effect of Dietary GSE on Intestinal β-Catenin and Cip1/p21 Expression

In further studies, we examined the expression levels of β-catenin and Cip1/p21 in different portions (proximal, middle, and distal) of the small intestinal tissues from control and GSE-treated groups of mice by immunostaining. A representative picture of β-catenin immunostaining from each group is shown in Figure 4A. The diffused staining for β-catenin was quantified on the basis of the intensity of immunoreactivity. Dietary administration of 0.5% GSE for 6 weeks showed decreased positivity for β-catenin (43%–59%, P < .001; Figure 4B). Further, an increased immunoreactivity for cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor Cip1/p21 in the small intestine was observed by GSE treatment compared with the control group (data not shown). The quantification of Cip1/p21-positive cells showed a 1.9- to 2.6-fold (P < .001) increase in GSE-treated group compared with the control group (Figure 4C). These observations indicated the likely inhibitory effect of GSE on β-catenin signaling and inhibition of cell cycle regulation through an increase in Cip1/p21 levels.

Figure 4.

Effect of dietary GSE on β-catenin and Cip1/p21 expression levels in intestinal tissue of APCmin/+ mice. Representative photographs for immunohistochemical staining of β-catenin positivity (A) in APCmin/+ mouse control and GSE-treated groups are shown at 400x magnifications. (B) Immunopositivity of β-catenin and (C) Cip1/p21-positive cells were assessed by quantification of immunohistochemically stained mouse intestinal epithelium in 10 randomly selected fields as described in Materials and Methods. Data are shown as mean ± SE of eight samples in each group.

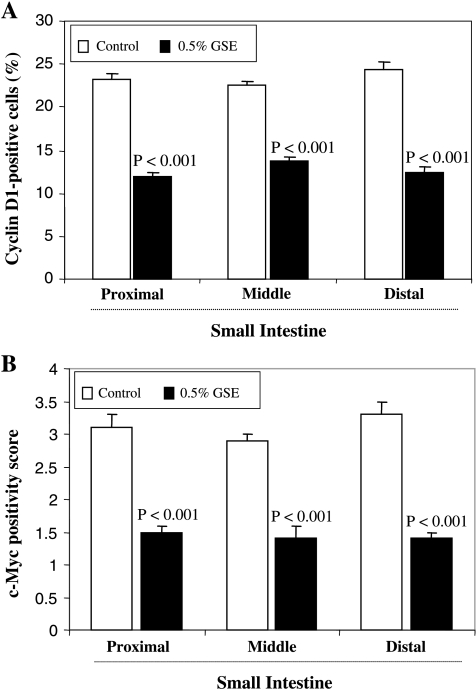

Effect of Dietary GSE on Intestinal Cyclin D1 and c-Myc Expression

To further confirm the effect of GSE on β-catenin pathway and its subsequent potential role in inhibition of cell cycle progression and cell proliferation, we examined the expression levels of β-catenin signaling targets, cyclin D1, and c-Myc that mediate cell cycle progression and cell proliferation (Figure 5). Intestinal sections were immunohistochemically analyzed for cyclin D1 and c-Myc using specific antibodies (staining data not shown). The quantification of the staining showed that dietary administration of 0.5% GSE for 6 weeks significantly decreased the number of cyclin D1-positive cells (39%–49%, P < .001) as well as c-Myc immunoreactivity (52%–58%, P < .001) in the small intestine (proximal, middle, and distal portions) compared with the control group. These results further support the effect of GSE on β-catenin signaling and its association with the inhibition of cell proliferation during polyp growth in the intestine.

Figure 5.

Effect of dietary GSE cyclin D1 and c-Myc expression levels in intestinal tissue of APCmin/+ mice. (A) Cyclin D1-positive cells and (B) immunopositivity of c-Myc were assessed by quantification of immunohistochemically stained mouse intestinal epithelium in 10 randomly selected fields as described in Materials and Methods. Data are shown as mean ± SE of eight samples in each group.

Discussion

APCmin/+ mice are heterozygous for a truncating mutation in the APC tumor-suppressor gene and provide a model of FAP and sporadic colorectal cancers [21]. Designated as a gatekeeper in colorectal tumorigenesis, mutation of APC leading to the deregulation of the Wnt signal transduction pathway is one of the earliest events in colorectal neoplasia [22,23]. Normally, in the absence of Wnt stimulation, β-catenin is targeted for degradation by a cytoplasmic complex containing APC, axin, and glycogen synthase kinase 3β. Therefore, mutation of APC gene increases cytoplasmic accumulation and nuclear translocation of β-catenin [24]. In the nucleus, the transcription factor, T-cell factor/lymphoid enhancer factor, are transactivated by β-catenin leading to an increased expression of genes that regulate cell proliferation and apoptosis [25,26]. Hence, the APCmin/+ mouse model is unique in which tumors appear spontaneously in the gastrointestinal tract, rather than induction by a carcinogen. Therefore, this model is particularly advantageous for testing chemopreventive agents targeted against early-stage lesions and relevant to the design of human chemoprevention clinical trials because an adequate number of adenomas grow to a grossly detectable size within a few months [19]. The concept of dietary chemoprevention is usually applied in the context of protecting normal cells from initiating events that introduce oncogenic mutations. It is a well-known fact that carcinogenesis represents a progression of cellular changes, and agents that disrupt this progression at any point can be considered chemopreventive [27,28]. In recent years, cancer prevention by dietary phytochemicals has received considerable attention.

The present study, using APCmin/+ mice, for the first time demonstrated that dietary administration of 0.5% GSE suppressed intestinal tumorigenesis, especially the large tumors and tumors in middle and distal portions of the small intestine. Further, the decrease in tumor number and size by GSE was accompanied by antiproliferative and proapoptotic effects together with down-regulation of iNOS, COX-2 and β-catenin, cyclin D1, and c-Myc levels and by an increase in Cip1/p21 protein level. These molecular changes suggest that the inhibition of β-catenin signaling could be one of the possible underlying mechanisms of antitumorigenic activity of GSE. The protective effect of GSE against intestinal tumorigenesis through inhibition of cell proliferation and induction of apoptosis correlates with the earlier reports on other naturally occurring dietary phytochemicals against tumor formation in APCmin/+ mouse model [29,30].

Many cancer susceptibility genes produce defects in the regulation of cell proliferation, differentiation, or apoptosis. It is well known that disruption of the balance between cell proliferation and cell death is the most important biological impetus leading to neoplasia [31]. One approach to cancer prevention and treatment could be to bypass these defects through alternate mechanisms or by modifying the defective mechanisms using naturally occurring or synthetic compounds. The proposed mechanisms of chemopreventive effects of GSE in the present study include the inhibition of the intestinal tumorigenesis by reduction in cell proliferation and enhancement of apoptosis.

Colon cancer development is often characterized in an early stage by a hyperproliferation of the epithelium leading to the formation of adenomas. In this multistep process, an early intervention should inhibit enhanced cell proliferation of transformed cells and, more importantly, the induction of the apoptotic pathway to delete the cells carrying mutations. Inhibition of apoptosis is a major mechanism in colon carcinogenesis and contributes to the development of colon tumor from the premalignant colonic epithelial cells [32]. Thus, identifying the mechanisms and approaches that upregulate the apoptotic processes will provide useful strategies for regulating colon tumor growth. Apoptosis is now considered to be an important target in identifying chemopreventive agents against colon cancer. This has been supported by several chemopreventive agents that have been shown to inhibit colon tumor growth by enhancing apoptosis [33]. The increase in intestinal epithelial cell apoptosis in the present study strengthens our belief that GSE-induced apoptosis could be important in controlling intestinal tumorigenesis. Our previous study in the cell culture showed that GSE increases cleaved levels of caspase-3 and poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase in human CRC cells [34]. However, further studies are needed to explore the GSE-induced intestinal cell apoptosis in APCmin/+ mice.

Preclinical and clinical studies suggest that COX-2 is involved in chronic inflammation and plays a crucial role in colon adenoma development [35]. Mutations of the APC gene have been notably linked with the overexpression of the COX-2 gene in a majority of colon cancers [36]. COX enzymes play a central role in the conversion of arachidonic acid to prostaglandins. One of the COX-2 reaction products, prostaglandin E2, is known to lead to the induction of cell proliferation and the inhibition of apoptosis that favor tumor development [37]. In colon carcinogenesis, overexpression of COX-2 has been observed in aberrant crypt foci, adenomas, and adenocarcinomas, suggesting its contribution to the growth of precursor lesions and tumors and their further progression [38]. Thus, suppression of COX activity is suggested to be one of the potential mechanisms for inhibition of carcinogenesis. Recent reports suggest that in addition to COX-2, iNOS may contribute to tumor development or acceleration of the early stage of tumorigenesis [39]. The elevated expression of iNOS has also been reported in carcinogen-induced rat colon cancers [40]. Moreover, elevated levels of iNOS have been detected in most adenomas and dysplastic lesions, suggesting that iNOS plays an important role in colon carcinogenesis [40]. In the current study, dietary administration of GSE reduced intestinal COX-2 and iNOS levels, and this may account for lowering the number of intestinal adenomas. Because inhibition of COX-2 and iNOS expression results in decreased cell proliferation and increased apoptosis [41], the reduction of COX-2 and iNOS expressions in the present study might contribute to the modulatory effects of GSE on cell proliferation and apoptosis.

Mutations in APC or β-catenin reported in many of human and experimental colon tumors either repress the degradation of β-catenin or accumulate cellular β-catenin that leads to the activation of oncogenic pathways [42]. β-Catenin signaling induces colonic hyperproliferation through the regulation of its target molecules, including Cip1/p21, cyclin D1, and c-Myc [42,43]. Active β-catenin/wnt signaling decreases Cip1/p21 level but increases cyclin D1 level, preventing cells from entering G1 arrest or differentiation, thereby allowing cells to proliferate [44]. In addition to interactions with cyclin-CDK complexes, Cip1/p21 has also been reported to inhibit cell cycle progression through the interaction with PCNA [45]. PCNA has been found in Cip1/p21-cyclin-CDK complexes and Cip1/p21 blocks the ability of PCNA to activate DNA polymerase delta, the principal replicative DNA polymerase [46]. Further, the disruption of Cip1/p21 expression leads to decreased cell death, suggesting its role in proapoptotic function [47,48]. In a recent study, apoptosis of colonic epithelial cells was reduced in mice deficient for Cip1/p21 after treatment with the colon carcinogen azoxymethane [49]. Conditional inactivation of c-Myc in APCmin/+ mice is found to suppress APC-dependent intestinal tumorigenesis along with an increase in apoptosis [50]. These studies suggest that GSE-mediated decrease in β-catenin together with an increase in Cip1/p21 and a decrease in cyclin D1 and c-Myc levels in the present study could contribute to both apoptosis and antiproliferative effects during inhibition of intestinal tumorigenesis. A recent report from our laboratory also suggests that GSE inhibits in vitro and in vivo growth of human colorectal carcinoma cells through an up-regulation of Cip1/p21 [34].

In summary, the present investigation has provided the first evidence for inhibition of intestinal tumorigenesis by dietary feeding of GSE in APCmin/+ mouse model. The suppression of proliferation and stimulation of apoptosis could involve the down-regulation of COX-2, iNOS, and β-catenin, cyclin D1 and c-Myc expression, and an up-regulation of Cip1/p21 as possible mechanisms by which GSE inhibits intestinal tumorigenesis in this animal model. These findings together with our earlier studies suggest that chemoprevention using dietary GSE could be a promising approach for colon cancer prevention in high-risk individuals, such as FAP carriers.

Abbreviations

- GSE

grape seed extract

- APC

adenomatous polyposis coli

Footnotes

This work was supported by grant RO1 AT003623 from the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine and the Office of Dietary Supplement, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD.

References

- 1.Hisamuddin IM, Yang VW. Molecular genetics of colorectal cancer: an overview. Curr Colorectal Cancer Rep. 2006;2:53–59. doi: 10.1007/s11888-006-0002-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sesink AL, Termont DS, Kleibeuker JH, Van Der Meer R. Red meat and colon cancer: dietary haem, but not fat, has cytotoxic and hyperproliferative effects on rat colonic epithelium. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:1909–1915. doi: 10.1093/carcin/21.10.1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Larsson SC, Wolk A. Meat consumption and risk of colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:2657–2664. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martínez ME. Primary prevention of colorectal cancer: lifestyle, nutrition, exercise. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2005;166:177–211. doi: 10.1007/3-540-26980-0_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Durak I, Cetin R, Devrim E, Ergüder IB. Effects of black grape extract on activities of DNA turn-over enzymes in cancerous and non cancerous human colon tissues. Life Sci. 2005;76:2995–3000. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eng ET, Ye J, Williams D, Phung S, Moore RE, Young MK, Gruntmanis U, Braunstein G, Chen S. Suppression of estrogen biosynthesis by procyanidin dimers in red wine and grape seeds. Cancer Res. 2003;63:8516–8522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharma G, Tyagi AK, Singh RP, Chan DC, Agarwal R. Synergistic anti-cancer effects of grape seed extract and conventional cytotoxic agent doxorubicin against human breast carcinoma cells. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2004;85:1–12. doi: 10.1023/B:BREA.0000020991.55659.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhao J, Wang J, Chen Y, Agarwal R. Anti-tumor-promoting activity of a polyphenolic fraction isolated from grape seeds in the mouse skin two-stage initiation-promotion protocol and identification of procyanidin B5-3′-gallate as the most effective antioxidant constituent. Carcinogenesis. 1999;20:1737–1745. doi: 10.1093/carcin/20.9.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hayasaka Y, Waters EJ, Cheynier V, Herderich MJ, Vidal S. Characterization of proanthocyanidins in grape seeds using electrospray mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2003;17:9–16. doi: 10.1002/rcm.869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kennedy JA, Hayasaka Y, Vidal S, Waters EJ, Jones GP. Composition of grape skin proanthocyanidins at different stages of berry development. J Agric Food Chem. 2001;49:5348–5355. doi: 10.1021/jf010758h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bagchi D, Bagchi M, Stohs S, Ray SD, Sen CK, Preuss HG. Cellular protection with proanthocyanidins derived from grape seeds. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;957:260–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb02922.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Faria A, Calhau C, de Freitas V, Mateus N. Procyanidins as antioxidants and tumor cell growth modulators. J Agric Food Chem. 2006;54:2392–2397. doi: 10.1021/jf0526487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ye X, Krohn RL, Liu W, Joshi SS, Kuszynski CA, McGinn TR, Bagchi M, Preuss HG, Stohs SJ, Bagchi D. The cytotoxic effects of a novel IH636 grape seed proanthocyanidin extract on cultured human cancer cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 1999;196:99–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim H, Hall P, Smith M, Kirk M, Prasain JK, Barnes S, Grubbs C. Chemoprevention by grape seed extract and genistein in carcinogen-induced mammary cancer in rats is diet dependent. J Nutr. 2004;134:3445S–3452S. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.12.3445S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singletary KW, Meline B. Effect of grape seed proanthocyanidins on colon aberrant crypts and breast tumors in a rat dual-organ tumor model. Nutr Cancer. 2001;39:252–258. doi: 10.1207/S15327914nc392_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singh RP, Tyagi AK, Dhanalakshmi S, Agarwal R, Agarwal C. Grape seed extract inhibits advanced human prostate tumor growth and angiogenesis and upregulates insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3. Int J Cancer. 2004;108:733–740. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raina K, Singh RP, Agarwal R, Agarwal C. Oral grape seed extract inhibits prostate tumor growth and progression in TRAMP mice. Cancer Res. 2007;67:5976–5982. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Corpet DE, Pierre F. Point: From animal models to prevention of colon cancer. Systematic review of chemoprevention in min mice and choice of the model system. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2003;12:391–400. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Su LK, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Preisinger AC, Moser AR, Luongo C, Gould KA, Dove WF. Multiple intestinal neoplasia caused by a mutation in the murine homolog of the APC gene. Science. 1992;256:668–670. doi: 10.1126/science.1350108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Polakis P. The adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) tumor suppressor. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1332:F127–F147. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(97)00008-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Lessons from hereditary colorectal cancer. Cell. 1996;87:159–170. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81333-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Powell SM, Zilz N, Beazer-Barclay Y, Bryan TM, Hamilton SR, Thibodeau SN, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. APC mutations occur early during colorectal tumorigenesis. Nature. 1992;359:235–237. doi: 10.1038/359235a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paul S, Dey A. Wnt signaling and cancer development: therapeutic implication. Neoplasma. 2008;55:165–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rubinfeld B, Albert I, Porfiri E, Fiol C, Munemitsu S, Polakis P. Binding of GSK3β to the APC-β-catenin complex and regulation of complex assembly. Science. 1996;272:1023–1026. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5264.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sparks AB, Morin PJ, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. Mutational analysis of the APC/β-catenin/Tcf pathway in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 1998;58:1130–1134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morin PJ, Sparks AB, Korinek V, Barker N, Clevers H, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. Activation of β-catenin-Tcf signaling in colon cancer by mutations in β-catenin or APC. Science. 1997;275:1787–1790. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5307.1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. Colorectal cancer and the intersection between basic and clinical research. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1994;59:517–521. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1994.059.01.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Singh RP, Tyagi AK, Dhanalakshmi S, Agarwal R, Agarwal C. Grape seed extract inhibits advanced human prostate tumor growth and angiogenesis and upregulates insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3. Int J Cancer. 2004;108:733–740. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shen G, Khor TO, Hu R, Yu S, Nair S, Ho CT, Reddy BS, Huang MT, Newmark HL, Kong AN. Chemoprevention of familial adenomatous polyposis by natural dietary compounds sulforaphane and dibenzoylmethane alone and in combination in ApcMin/+ mouse. Cancer Res. 2007;67:9937–9944. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bobe G, Wang B, Seeram NP, Nair MG, Bourquin LD. Dietary anthocyanin-rich tart cherry extract inhibits intestinal tumorigenesis in APC (Min) mice fed suboptimal levels of sulindac. J Agric Food Chem. 2006;54:9322–9328. doi: 10.1021/jf0612169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakano R. Apoptosis: gene-directed cell death. An overview. Horm Res. 1997;48:2–4. doi: 10.1159/000191292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huerta S, Goulet EJ, Livingston EH. Colon cancer and apoptosis. Am J Surg. 2006;191:517–526. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Juan ME, Planas JM, Ruiz-Gutierrez V, Daniel H, Wenzel U. Antiproliferative and apoptosis-inducing effects of maslinic and oleanolic acids, two pentacyclic triterpenes from olives, on HT-29 colon cancer cells. Br J Nutr. 2008;26:1–8. doi: 10.1017/S0007114508882979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kaur M, Singh RP, Gu M, Agarwal R, Agarwal C. Grape seed extract inhibits in vitro and in vivo growth of human colorectal carcinoma cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:6194–6202. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sinicrope FA. Targeting cyclooxygenase-2 for prevention and therapy of colorectal cancer. Mol Carcinog. 2006;45:447–454. doi: 10.1002/mc.20232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dimberg J, Hugander A, Sirsjö A, Söderkvist P. Enhanced expression of cyclooxygenase-2 and nuclear beta-catenin are related to mutations in the APC gene in human colorectal cancer. Anticancer Res. 2001;21:911–915. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang DY, Wu J, Ye F, Xue L, Jiang S, Yi J, Zhang W, Wei H, Sung M, Wang W, et al. Inhibition of cancer cell proliferation and prostaglandin E2 synthesis by Scutellaria baicalensis. Cancer Res. 2003;63:4037–4043. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ferrández A, Prescott S, Burt RW. COX-2 and colorectal cancer. Curr Pharm Des. 2003;9:2229–2251. doi: 10.2174/1381612033454036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nosho K, Yoshida M, Yamamoto H, Taniguchi H, Adachi Y, Mikami M, Hinoda Y, Imai K. Association of Ets-related transcriptional factor E1AF expression with overexpression of matrix metalloproteinases, COX-2 and iNOS in the early stage of colorectal carcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis. 2005;26:892–899. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Takahashi M, Mutoh M, Kawamori T, Sugimura T, Wakabayashi K. Altered expression of beta-catenin, inducible nitric oxide synthase and cyclooxygenase- 2 in azoxymethane-induced rat colon carcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:1319–1327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Watanabe K, Kawamori T, Nakatsugi S, Wakabayashi K. COX-2 and iNOS, good targets for chemoprevention of colon cancer. Biofactors. 2000;12:129–133. doi: 10.1002/biof.5520120120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Herbst A, Kolligs FT. Wnt signaling as a therapeutic target for cancer. Methods Mol Biol. 2007;361:63–91. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-208-4:63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Koornstra JJ, Rijcken FE, Oldenhuis CN, Zwart N, van der Sluis T, Hollema H, deVries EG, Keller JJ, Offerhaus JA, Giardiello FM, et al. Sulindac inhibits β-catenin expression in normal-appearing colon of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer and familial adenomatous polyposis patients. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:1608–1612. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van de Wetering M, Sancho E, Verweij C, de Lau W, Oving I, Hurlstone A, van der Horn K, Batlle E, Coudreuse D, Haramis AP, et al. The β-catenin/TCF-4 complex imposes a crypt progenitor phenotype on colorectal cancer cells. Cell. 2002;111:241–250. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01014-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Waga S, Hannon GJ, Beach D, Stillman B. The p21 inhibitor of cyclin-dependent kinases controls DNA replication by interaction with PCNA. Nature. 1994;369:574–578. doi: 10.1038/369574a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang H, Xiong Y, Beach D. Proliferating cell nuclear antigen and p21 are components of multiple cell cycle kinase complexes. Mol Biol Cell. 1993;4:897–906. doi: 10.1091/mbc.4.9.897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hingorani R, Bi B, Dao T, Bae Y, Matsuzawa A, Crispe IN. CD95/Fas signaling in T lymphocytes induces the cell cycle control protein p21cip-1/WAF-1, which promotes apoptosis. J Immunol. 2000;164:4032–4036. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.8.4032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.O'Reilly MA. Redox activation of p21Cip1/WAF1/Sdi1: a multifunctional regulator of cell survival and death. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2005;7:108–118. doi: 10.1089/ars.2005.7.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Poole AJ, Heap D, Carroll RE, Tyner AL. Tumor suppressor functions for the Cdk inhibitor p21 in the mouse colon. Oncogene. 2004;23:8128–8134. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ignatenko NA, Holubec H, Besselsen DG, Blohm-Mangone KA, Padilla-Torres JL, Nagle RB, de Alboránç IM, Guillen-R JM, Gerner EW. Role of c-Myc in intestinal tumorigenesis of the ApcMin/+ mouse. Cancer Biol Ther. 2006;5:1658–1664. doi: 10.4161/cbt.5.12.3376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]