Abstract

The sequence of heterocyclic bases on the interior of the DNA double helix constitutes the genetic code that drives the operation of all living organisms. With this said, it is not surprising that chemical modification of cellular DNA can have profound biological consequences. Therefore, the organic chemistry of DNA damage is fundamentally important to diverse fields including medicinal chemistry, toxicology, and biotechnology. This review is designed to provide a brief overview of the common types of chemical reactions that lead to DNA damage under physiological conditions.

1. Introduction

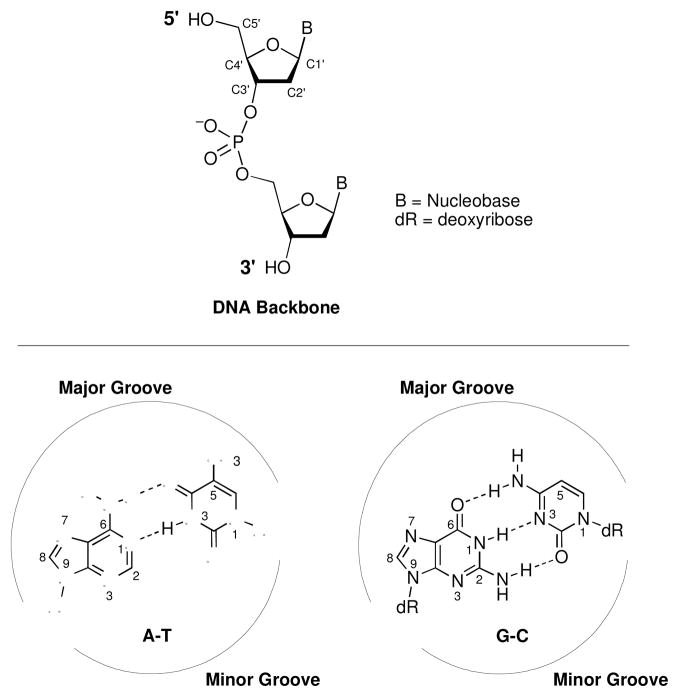

The sequence of heterocyclic bases on the interior of the DNA double helix constitutes the genetic code that drives the operation of all living organisms (Figure 1) (1–4). Accurate readout of DNA sequence is necessary for the expression of functional messenger RNA and, ultimately, proteins in cells (5). In addition, during cell division, faithful replication of DNA is required to produce daughter cells containing exact copies of the genome (6). In light of these facts, it is not surprising that chemical modification of cellular DNA can have profound biological consequences. DNA damage can trigger changes in gene expression, inhibit cell division, or trigger cell death (7–9). In addition, attempts to replicate damaged DNA can introduce errors (mutations) into the genetic code (10). Thus, the organic chemistry of DNA damage is fundamentally important to diverse fields including medicinal chemistry, toxicology, and biotechnology (11–13). This review is designed to provide a brief overview of the most common types of chemical reactions that lead to DNA damage under physiological conditions.

Figure 1.

Structure of DNA

2. Hydrolysis of DNA

2.1 Spontaneous Hydrolysis of the Phosphodiester Backbone Is Very Slow

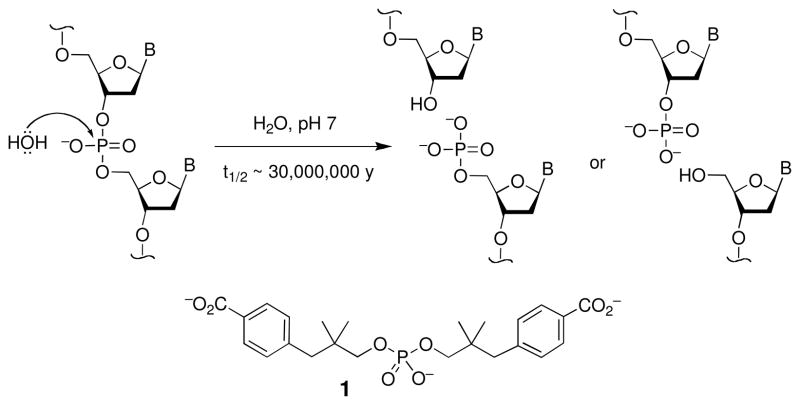

Hydrolysis of the phosphodiester groups in the backbone of DNA is thermodynamically favored (ΔG°′ = −5.3 kcal/mol)(14) but extremely slow (Scheme 1) (15).1 Work with carefully designed model compounds such as 1 indicate that the half-life of phosphodiester hydrolysis is approximately 30,000,000 years under physiologically-relevant conditions (15–18). In short, this means that spontaneous hydrolysis of the phosphodiester linkages in DNA does not occur to a significant extent under biological conditions, although the reaction can be vastly accelerated by various catalysts including phosphodiesterases, lanthanide ions, and transition metal ions (19–23).

Scheme 1.

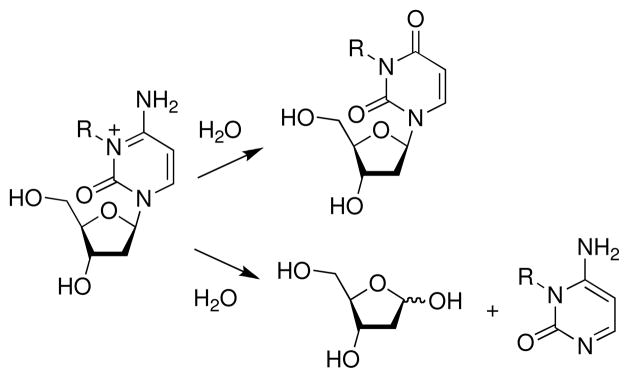

2.2 Hydrolytic Deamination of DNA Bases

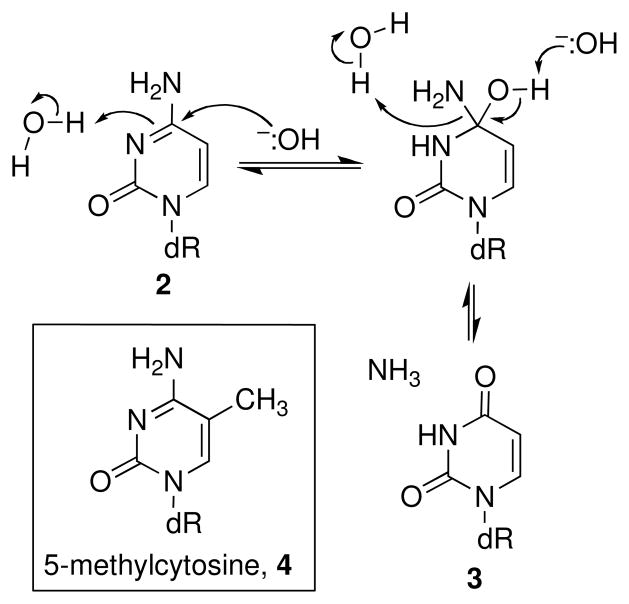

Cytosine residues (2) in DNA can undergo hydrolytic deamination to yield uracil residues 3 (Scheme 2) (24–28). The reaction may proceed either via attack of hydroxide on the neutral nucleobase or attack of water on the N3-protonated base (Scheme 2) (24, 25, 29). Sensitive genetic reversion assays revealed that cytosine deamination occurs in duplex DNA with a half-life of 30,000–85,000 y at pH 7.4, 37 °C (27, 28). In single-stranded DNA, and at base mismatches in duplex DNA, deamination proceeds much faster (t1/2 ~ 200 years) presumably due to increased solvent accessibility of the base (26, 30). Deamination of guanine and adenine residues in DNA is much slower, occurring at only 2–3% the rate of cytosine deamination (31).

Scheme 2.

Methylcytosine residues (4) are mutation hotspots in bacterial and eukaryotic genomes (28). The deamination of 5-methylcytosine residues occurs approximately 2–3 times faster than at unmodified cytosine residues(28); however, the increased mutation frequencies observed at methylcytosine positions is believed to stem, not from increased deamination at these sites, but from the fact that the resulting G-T mismatches are poorly repaired and produce G-C→A-T transitions in one of the daughter cells (28, 32, 33). Mutagenesis resulting from deamination at 5-methylcytosine residues teaches us an important, general lesson: that is, DNA-damage reactions that are terribly slow and low yielding can have profound biological consequences if the resulting lesion is not efficiently repaired and is mutagenic or cytotoxic.

Alkylation of the N3-position of cytosine and reactions that lead to saturation of the 5,6-double bond in cytosine and 5-methylcytosine accelerate deamination (34–41). Activation-induced cytidine deaminases catalyze the conversion of cytosine residues to uracil residues in single-stranded regions of DNA (42, 43). In addition, deamination is an important reaction that is associated with exposure of DNA to nitrosating agents and nitric oxide(44–47).

2.3 Spontaneous Hydrolysis of the Glycosidic Bonds Connecting the Nucleobases to the DNA Backbone

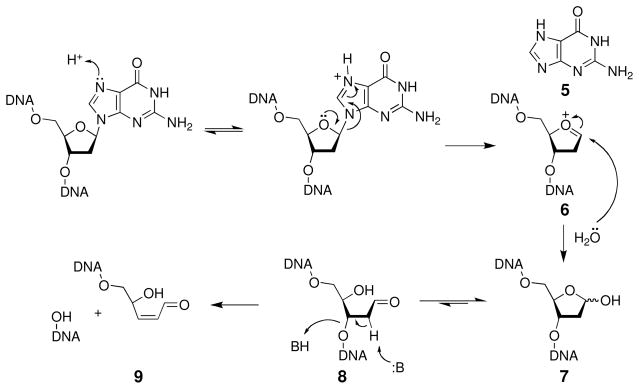

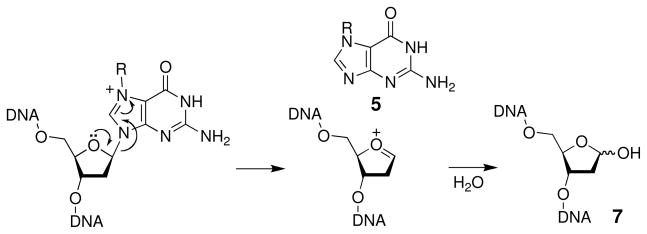

With regard to hydrolytic stability, the glycosidic bonds that hold the nucleobases to the sugar-phosphate backbone are weak points in the structure of DNA (Scheme 3). The pyrimidine bases cytosine and thymine are lost with rate constants of 1.5 × 10−12 s−1 (t1/2 = 14,700 y) while the reaction is faster at the purine bases guanine and adenine, occurring with rate constants of 3.0 × 10−11 s−1 (t1/2 = 730 y) (48, 49). Accordingly, hydrolytic cleavage of the glycosidic bonds in DNA is often referred to as “depurination” because the reaction is much more facile at purines than at pyrimidines. Hydrolysis of the glycosidic bond in 2′-deoxypurines proceeds via a specific acid-catalyzed SN1 reaction mechanism (50, 51). Equilibrium protonation increases the leaving group ability of the base and facilitates unimolecular, rate-limiting C-N bond cleavage that generates the free base 5 and an oxocarbenium ion 6 (Scheme 3). The oxocarbenium ion undergoes subsequent hydrolysis to yield an abasic site 7 (often referred to as an apurinic site or AP site). It is calculated that spontaneous depurination generates about 10,000 abasic sites per cell per day (49). Indeed, steady state levels of 10,000–50,000 abasic sites have been detected in cells (52, 53). Depurination occurs about four times faster in single-stranded DNA than it does in duplex DNA (49).

Scheme 3.

2.3 Properties of Abasic Sites Arising from Depurination

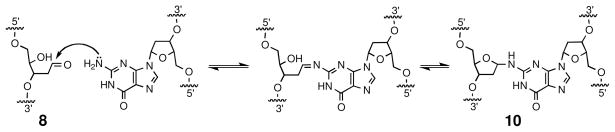

Abasic sites (7, Scheme 3) generated by depurination are cytotoxic and mutagenic (54, 55). This lesion exists as an equilibrium mixture of the ring-closed acetal (7, 99%) and the ring-opened aldehyde (8, 1%) (56). Abstraction of the acidic α-proton adjacent to the aldehyde group in 8 leads to β-elimination of the phosphate residue on the 3′-side of the abasic site. This strand-cleavage reaction occurs with a half-life of 200 h under physiological conditions (pH 7.4, 37 °C) (57, 58). Thermal workup, sodium hydroxide, or treatment with various amines such as piperidine, dimethylethylene diamine, or putrescine facilitate strand cleavage at abasic sites (59–62). Subsequent γ,δ-elimination of the phosphate on the 5′-side of the abasic site 9 is relatively slow under physiological conditions (57) but occurs readily under basic conditions (e.g. 0.05 M NaOH, 37 °C, 2 h) to generate a strand break with 3′- and 5′-phosphate termini (63, 64).

In addition to generating single-strand breaks, the aldehyde residue of the ring-opened form of the abasic site can react with the exocyclic N2-amino group of a guanine residue on the opposing strand to generate an interstrand cross-link 10 at 5′-d(CAp) sites (where Ap = the abasic site, Scheme 4) (65). This is especially intriguing because interstrand DNA crosslinks are highly cytotoxic lesions (66–68).

Scheme 4.

3. Overview: Common Reactions By Which Small Organic Molecules Damage DNA

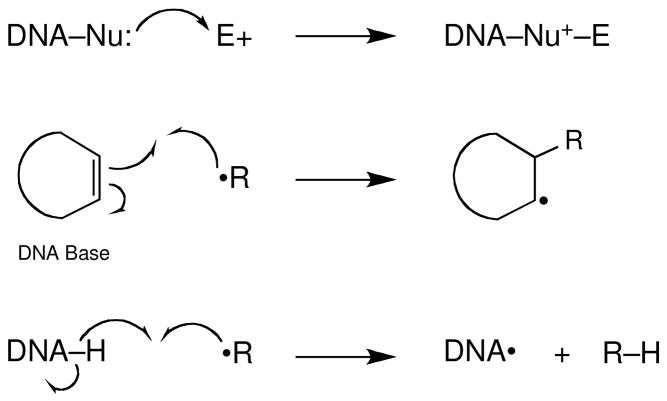

The vast majority of DNA-damage caused by bioactive molecules such as drugs, toxins, and mutagens falls into just two general categories: (1) alkylation of a DNA nucleophile by an electrophile or (2) the reaction of a pi bond or C-H bond in DNA with a radical intermediate (Scheme 5). In the following sections, we will consider the reactions of electrophiles and radicals with DNA and examine the fate of the chemically modified DNA that is generated in these processes.

Scheme 5.

4. DNA Alkylation

4.1 Preferred Alkylation Sites in DNA

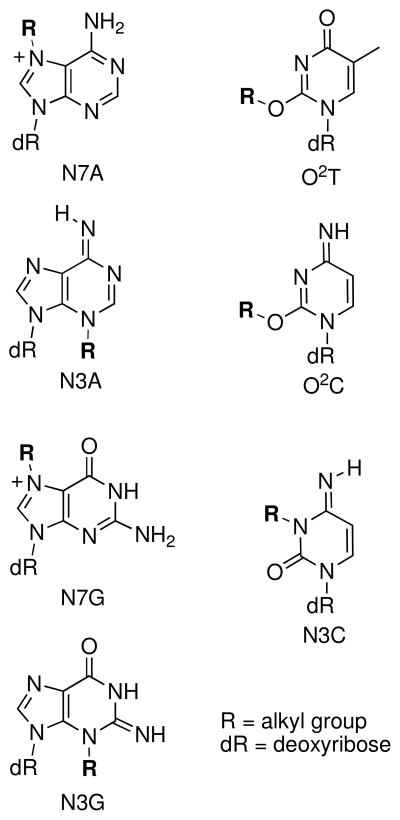

Almost all of the heteroatoms in the double helix have the potential to be alkylated. The preferred sites of alkylation in duplex DNA depend strongly on the nature of the alkylating agent. For example, in the case of diethylsulfate, the preferred sites of reaction follow the order: N7G≫P–O>N3A≫N1A~N7A~N3G~N3C≫O6G (69, 70). In contrast, the preferred sites for alkylation by ethyldiazonium ion follow the order: P–O≫N7G>O2T>O6G>N3A~O2C>O4T>N3G~N3T~N3C~N7A (69, 70). The N7-position of the guanine residue is the most nucleophilic site on the DNA bases and is a favored site of reaction for almost all small, freely-diffusible alkylating agents. The preferences observed at other sites commonly have been rationalized in terms of hard-soft reactivity principles (71). Hard alkylating agents (defined by small size, positive charge, and low polarizability) such as diazonium ions display increased reactivity with hard oxygen nucleophiles in DNA (69, 70, 72–74). On the other hand, soft (large, uncharged, polarizable) alkylating agents like dialkylsulfates favor reactions at the softer nitrogen centers in DNA.2

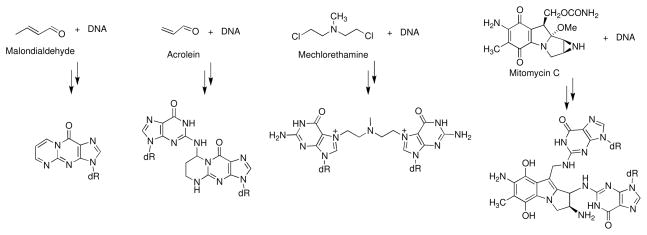

Typically, small diffusible alkylating agents react with DNA at multiple sites; however, connection of a non-selective alkylating agent to noncovalent DNA-binding units can confer sequence and atom-site selectivity to the reaction (75–83). Bifunctional alkylating agents (molecules containing two electrophilic centers) can cross-link two nucleophilic centers in the DNA duplex. Examples of bifunctional DNA alkylating agents shown in Figure 2 include the endogenous lipid peroxidation products malondialdehyde (84) and acrolein (85) and the anticancer drugs mitomycin C (86) and mechlorethamine (87). Cross-links may present special challenges to DNA repair systems and agents that generate cross-links can be exceptionally bioactive (66–68). Accordingly, a significant number of clinically-used anticancer drugs are DNA cross-linking agents (66).

Figure 2.

Reactions of bifunctional electrophiles with DNA

4.2 The Chemical Fate of Alkylated DNA

4.2.1 Alkylated Phosphates Are Chemically Stable

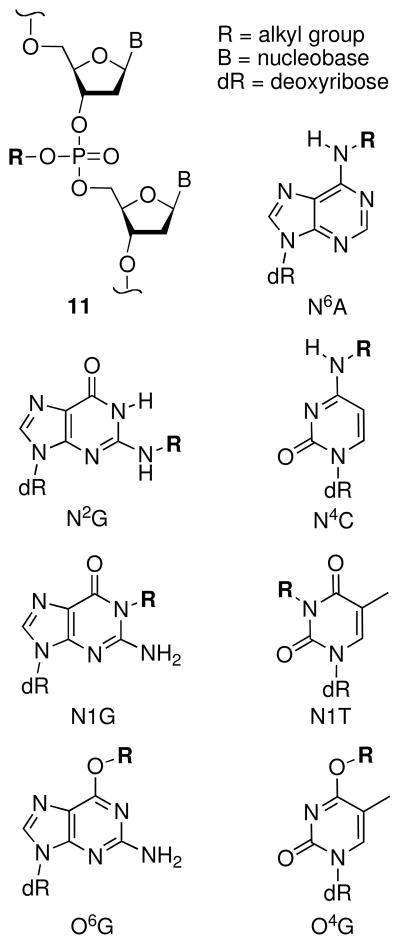

Alkylation of a DNA phosphodiester residue yields a phosphotriester (11, Figure 3). Phosphotriesters undergo hydrolysis about 109-times more rapidly than native DNA phosphodiesters (15). Nonetheless, hydrolysis of phosphotriesters is slow under physiological conditions, and alkylated DNA phosphates are chemically stable both in vitro and in vivo (88, 89).

Figure 3.

Chemically stable lesions resulting from DNA alkylation

4.2.2 Alkylation At Some Positions on the DNA Nucleobases Yields Chemically Stable Adducts

Alkylation at the exocyclic nitrogen atoms N2G, N6A, N4C, the amidic nitrogens at N1-G, N1-T, and the oxygens at O6-G and O4-T yields chemically stable adducts (Figure 3) (90–96). Special attention has been paid to the O6-G and O4-T adducts because these reactions alter the Watson-Crick hydrogen bonding faces of these bases and cause miscoding and mutagenesis during DNA replication (97–99).

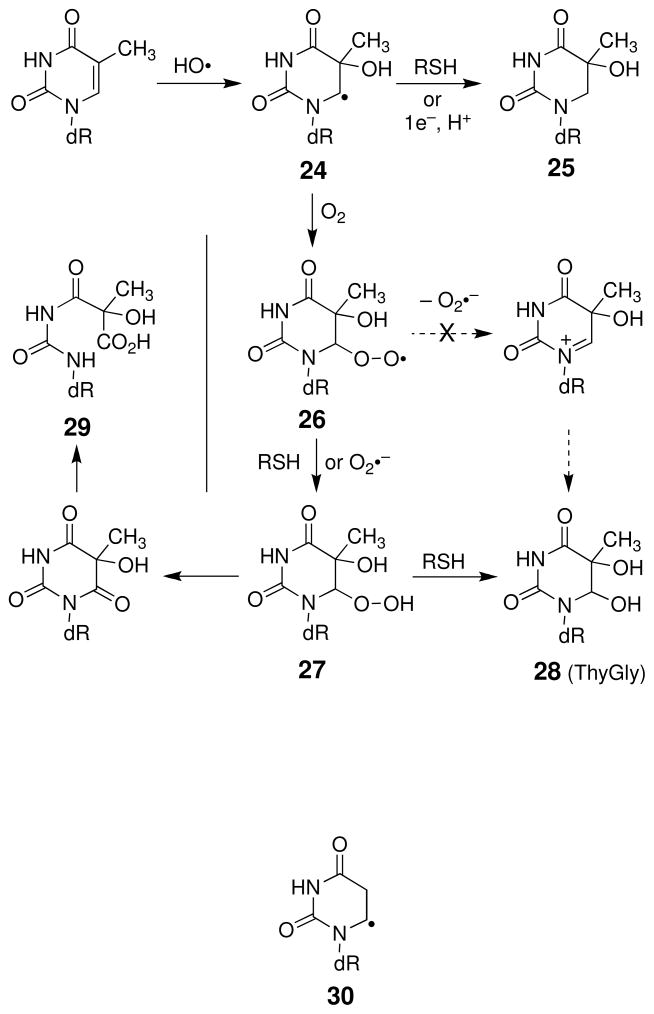

4.2.3 Alkylation of Some Endocyclic Nitrogens on the Nucleobases Yields Labile Lesions That Undergo Deglycosylation or Ring-Opening

Alkylation of the endocyclic nitrogens N7G, N7A, N3G, N3A, N1A, and N3C can destabilize the nucleobases, facilitating deglycosylation and ring-opening reactions (Figure 4). The half-lives for deglycosylation of bases modified with simple alkyl groups in DNA generally follows the trend: N7dA (3 h) > N3dA (24 h) > N7dG (150 h) > N3dG (greater than 150 h) > O2dC (750 h) > O2dT (6300 h) > N3dC (>7700 h) (36, 96, 100–105). The mechanisms for these processes (Scheme 6) mirror that described above for acid-catalyzed deglycosylation reactions (Scheme 3) (106). Studies on the depurination of rates of N7-alkylguanine derivatives indicate that electron-withdrawing groups on the alkyl substituent increase the rate of deglycosylation (103, 107, 108).

Figure 4.

Chemically labile lesions resulting from DNA alkylation

Scheme 6.

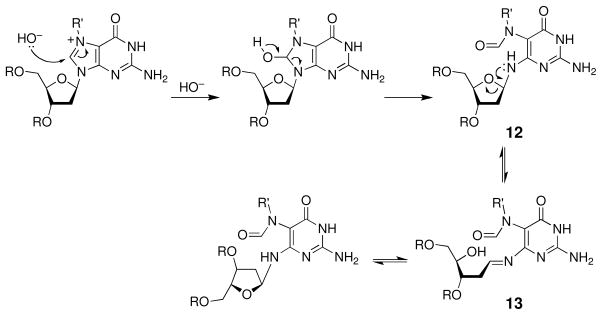

Alternatively, attack of water at the C8-position of an N7-alkylguanine residue initiates a ring-opening reaction that yields the corresponding 5-(alkyl)formamidopyrimidine (FAPy) derivative 12 (Scheme 7) (103, 109–116). In general, the ring-opening reaction that yields alkyl-FAPy derivatives is slow compared to the competing depurination reaction under physiological conditions (103, 117), although basic conditions (e.g. pH 10, 37 °C, 4 h) can be used to generate alkyl-FAPy lesions from N7-alkylguanine lesions in oligonucleotides (116, 118). Nonetheless, FAPy lesions are formed in vivo and are persistent lesions found in animals following exposure to alkylating agents (119–121) In this regard, it may be important that the glycosidic bond in alkyl-FAPy residues is stable at neutral pH (122). Deglycosylation of FAPy residues occurs only slowly, with an estimated (103, 123) half-life of about 1500 h in single-stranded DNA at pH 7.5 and 37 °C. The deglycosylation reaction is pH-dependent, however, and at pH 6.5, complete deglycosylation of 5-methyl-FAPy in an oligonucleotide was observed over 48 h (122). The stereochemistry of the attachment between the FAPy base and the deoxyribose sugar residue undergoes anomerization via an imine intermediate 13 (Scheme 7) (122, 124, 125). The half-life of this process is 3.5 h for the FAPy derivative of deoxyguanosine in a nucleoside derivative (123, 126) and 16 h for the FAPy derivative of aflatoxin B1 in a single-stranded DNA oligomer (124).

Scheme 7.

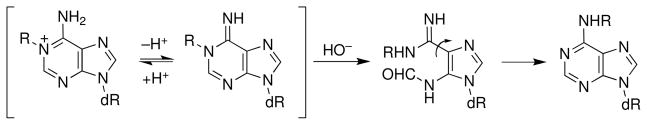

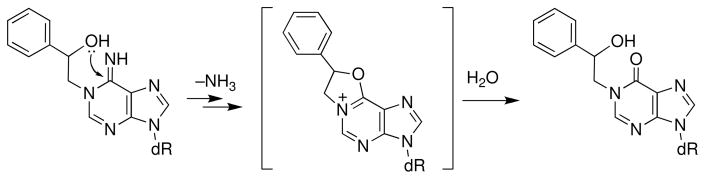

Adenine residues alkylated at the N1-position are also prone to hydrolytic ring opening. In this case, however, ring-opening initiates a Dimroth rearrangement reaction that leads to an apparent migration of the alkyl group from the N1 position to the exocyclic N6-position of the nucleobase (Scheme 8) (127). The Dimroth rearrangement occurs with a half-life of approximately 150 h at pH 7 in the context of the nucleotide, 1-methyl-2′-deoxyadenosine-5′-phosphate (101). Importantly, this rearrangement can occur even when the adducted base is stacked within the DNA double helix (128).

Scheme 8.

4.2.4 Alkylation at Some Endocyclic Nitrogens Accelerates Deamination

Alkylation of the N3-position of cytosine (Scheme 9) vastly accelerates deamination of the nucleobase. For example, deamination of 3-methyl-2′-deoxycytidine, occurring with a half-life of 406 h, proceeds 4000 times faster than the same reaction in the native nucleoside (36). Alkylation of the endocyclic nitrogen in deoxycytidine also facilitates deglycosylation (t1/2 = 7700 h, lower pathway in Scheme 9), but, in the context of the nucleoside, the deamination reaction is approximately 20 times faster and predominates (36). Alkylation at the N1-position of 2′-deoxyadenosine nucleosides typically leads to a Dimroth rearrangement rather than deamination (129); however, the hydroxyl group of N1-styrene adducts facilitates deamination via intramolecular attack on C6 of the adducted base (Scheme 10) (130–132).

Scheme 9.

Scheme 10.

5. Reactions of Radicals with DNA

5.1 Abstraction of Hydrogen Atoms from the 2′-Deoxyribose Sugars of DNA: General Features

Abstraction of hydrogen atoms from the sugar-phosphate backbone of DNA generates 2-deoxyribose radicals that lead to final strand damage products via complex reaction cascades (133–137). In the case of highly reactive species such as the hydroxyl radical (HO•), the relative amounts of direct strand cleavage stemming from hydrogen atom abstraction at each position of the deoxyribose sugars is dictated by steric accessibility of the deoxyribose hydrogens, rather than their C-H bond strengths (133–138). The steric accessibility of the deoxyribose hydrogens in DNA follows the trend: H5′ > H4′ ≫ H3′ ~ H2′ ~ H1′ (138). Here we will summarize DNA strand damage arising from hydrogen atom abstraction at the C1′ and C4′ positions of deoxyribose. These examples were selected because they are perhaps the best characterized pathways and are illustrative of the general types of reactions that stem from radical-mediated damage to the deoxyribose units of DNA. A number of excellent reviews provide more comprehensive coverage of radical-mediated strand damage reactions (133–137).

5.2 Alkali-labile Strand Damage Stemming from Abstraction of the C1′-Hydrogen Atom

Though sequestered deep in the minor groove of duplex DNA (138), the C1′-hydrogen atom is an important reaction site for a variety of agents including Cu(o-phenanthroline)2, neocarzinostatin, esperamicin, dynemicin, tirapazamine, and radiation (134, 139). In addition, some base radical adducts efficiently abstract the C1′-hydrogen atom (140).

In cells, 2-deoxyribose radicals generally are expected to react with either molecular oxygen, present at 60–100 μM, or thiols such as glutathione which are present at 1–10 mM. The C1′-radical abstracts a hydrogen atom from thiols with a rate constant of 1.8 × 106 M−1 s−1 in duplex DNA (141). This reaction has the potential to generate either the natural β-anomer (a “chemical repair” reaction) or the mutagenic α-anomer. Greenberg’s group showed that, in duplex DNA, the C1′-radical reacts with 2-mercaptoethanol to yield a 6:1 ratio of the natural β-anomer over the α-anomer (141).

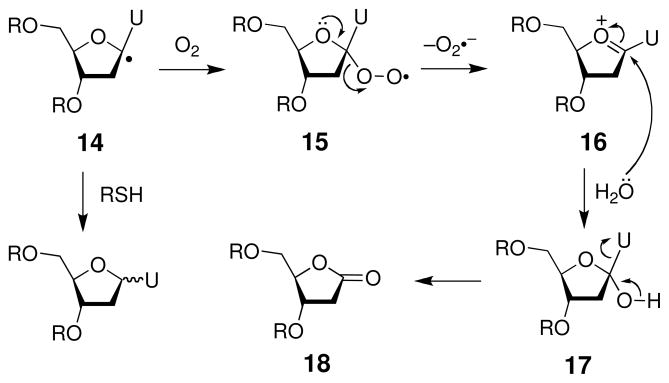

Molecular oxygen reacts with the C1′ radical (14) with a rate constant of 1 × 109 M−1 s−1 to yield the peroxyl radical 15 (Scheme 11) (142). The peroxyl radical ejects superoxide radical anion (pKa of the relevant conjugate acid HOO• is 5.1) with a rate constant of 2 × 104 s−1 to generate the carbocation 16 (142) that, in turn, is attacked by water to give the presumed C1′-alcohol intermediate 17. Loss of the DNA base yields the 2-deoxyribonolactone abasic site 18. The ratio of rate constants kO2/kRSH = 1100 (143). This means that at normal cellular concentrations of oxygen (~70 μM) and thiol (5 mM) more than 90% of the radical will be trapped by molecular oxygen.

Scheme 11.

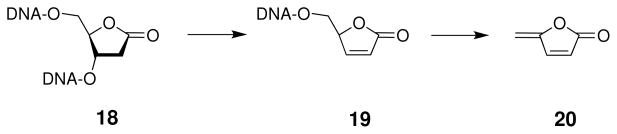

The 2-deoxyribonolactone lesion 18 does not rapidly yield direct strand cleavage (“frank strand breaks”) under physiological conditions (144–146). Rather, 18 is a base-labile lesion that is efficiently converted into a strand break upon treatment with piperidine (0.1 M, 20 min, 90 °C) or hydroxide (at pH 10, 37 °C, the t1/2 for the cleavage reaction is 15 min in a single stranded oligomer) (144, 145). Under physiologically-relevant conditions, α,β-elimination of the 3′-phosphate residue slowly yields strand cleavage with a half-life of between 38–54 h in double-stranded DNA, depending on the identity of the base that opposes the lactone abasic site (Scheme 12) (144–146). The resulting 3′-ene-lactone intermediate 19 subsequently undergoes rapid γ,δ-elimination to give the methylene lactone byproduct (20) and an oligonucleotide with a 3′-phosphate residue (145, 146). The transient ene-lactone (19) has been trapped by a variety of chemical reagents (144). In addition, the 2-ribonolactone and the ene-lactone form covalent crosslinks with DNA-binding proteins (147, 148).

Scheme 12.

5.3 Direct Strand Cleavage Initiated by Abstraction of the 4′-Hydrogen Atom

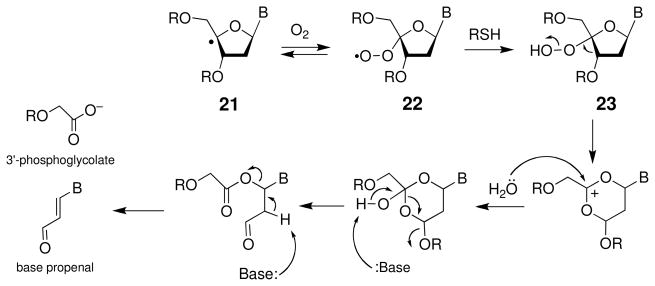

Abstraction of the 4′-hydrogen atom from the sugar-phosphate backbone of duplex DNA is a major reaction for hydroxyl radical (HO•), tirapazamine, bleomycin, and several enediynes (136, 139, 149). The C4′ radical 21 abstracts hydrogen atoms from biological thiols with a rate constant of about 2 × 106 M−1 s−1 in single-stranded DNA (150). In duplex DNA, this chemical repair reaction yields a 10:1 ratio of natural:unnatural stereochemistry at the C4′ center (151). Reaction of the C4′ radical 21 with molecular oxygen yields the peroxyl radical 22, with a presumed rate constant of about 2 × 109 M−1 s−1 (Scheme 13) (150). Reaction of the peroxyl radical with thiol, occurring with a rate constant of k ≤ 200 M−1 s−1 (152), yields the hydroperoxide 23. This intermediate has been observed directly by MALDI mass spectroscopy in a single-stranded 2′-deoxyribonucleotide in which a single C4′ radical was generated at a defined site (153). In the case of agents such as bleomycin, peroxynitrite, and the enediynes, the hydroperoxide (23) is thought to yield direct strand cleavage via a Criegee rearrangement, followed by hydrolysis and fragmentation reactions that generate the 5′-phosphate, 3′-phosphoglycolate, and base propenal end products (Scheme 13) (153). The base propenals generated in this reaction act as “malondialdehyde equivalents” that can go forward to cause further damage DNA via covalent modification of guanine residues (Scheme 14) (154, 155).

Scheme 13.

Scheme 14.

5.4 Reactions of Radicals with the Nucleobases

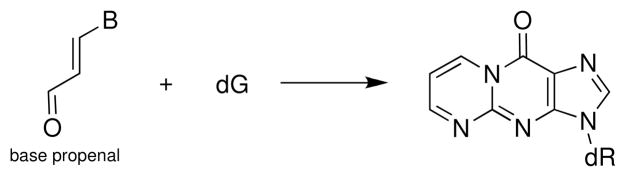

Radicals react readily with the heterocyclic bases of DNA. For example, over 90% of the hydroxyl radicals generated by γ-radiolysis react at the nucleobases in polyU (see page 340 of ref. (156)). A large number of base damage products arising from the reaction of hydroxyl radical with DNA have been characterized (Figure 5) (157–162). These products arise via hydrogen atom abstraction or, more commonly, addition of hydroxyl radical to the pi bonds of the bases (Scheme 5). Here we consider the formation of several common DNA base damage products arising from reactions at thymidine and deoxyguanosine. The pathways described here produce some of the most prevalent oxidative base damage products and also illustrate the general types of reactions that commonly occur following the attack of radicals on the nucleobases.

Figure 5.

Oxidatively-damaged nucleobases

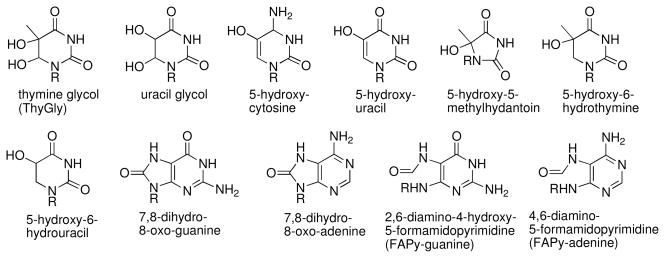

5.5 Addition of Radicals to C5 of Thymine Residues: Generation of Thymine Glycol

Radicals such as HO• readily add to the carbon-carbon pi bond of thymine residues (163). Addition of hydroxyl radical to the C5-position thymine residues generates the C6-thymidine radical (24, Scheme 15) (133). (To a lesser extent, hydroxyl radical also adds to the C6-position of thymine residues (133), but reactions stemming from this pathway will not be discussed here). The base radical adduct (24) resulting from addition of HO• at C5 may be reduced by reagents such as thiols or superoxide radical to yield the 5-hydroxy-6-hydrothymine residue (25, Scheme 15) (133, 164). Alternatively, reaction with molecular oxygen produces the peroxyl radical 26. Based upon model reactions involving the uracil free base (165), it has been proposed that ejection of superoxide radical anion from 26, followed by subsequent attack of water, generates thymine glycol (28) (133). However, recent studies did not detect production of superoxide from the structurally-related peroxyl radical derived from 5,6-dihydro-2′-deoxyuridin-6-yl (30). It was concluded that the rate for superoxide elimination is less than 10−3 s−1 (166). This suggests that, in biological systems, the peroxyl radical 26 may instead abstract a hydrogen atom from thiols to give the hydroperoxide 27 which, in turn, is expected to undergo further thiol-mediated reduction to yield thymine glycol 28. Thymine glycol is one of the major products stemming from oxidative damage of DNA (157–161). In the absence of thiol, the hydroperoxide 27 undergoes slow decomposition (t1/2 = 1.5–10 h for the nucleoside in water, with the trans isomer decomposing more rapidly than the cis) to generate the ring-opened lesion 29 as the major product and thymine glycol 28 as a minor product (Scheme 15) (167).

Scheme 15.

5.6 Addition of Radicals to Guanine Residues: Generation of FAPy-G and 8-Oxo-G Residues

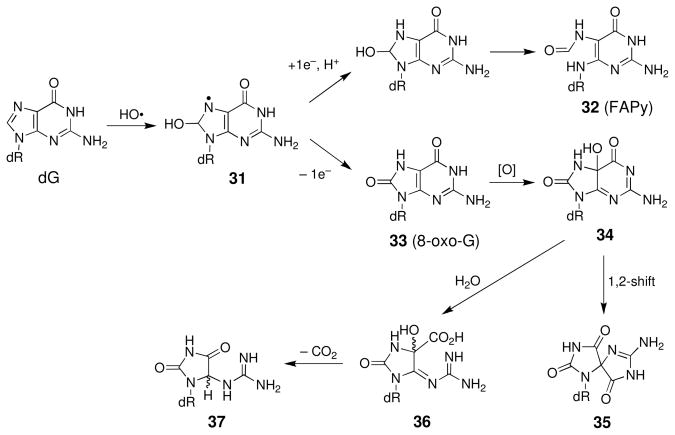

Guanine is a major target for oxidative damage by radicals (157, 168, 169). A major pathway for the reaction of radicals with guanine residues involves addition to the C8-position (Scheme 16) (157, 170, 171) This process yields a “redox ambivalent” nucleobase radical 31 that can undergo either one-electron reduction or oxidation (157, 164, 171). Reduction leads to a ring-opened formamidopyrimidine (FAPy) lesion (32, Scheme 16) that is chemically stable in DNA under physiological conditions and is mutagenic (172–175). On the other hand, oxidation of the base radical adduct 31 yields 8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanosine (33, 8-oxo-G). The 8-oxo-G lesion has been incorporated into synthetic 2′-deoxyoligonucleotides (176), but is prone to oxidative decomposition under biologically-relevant conditions (157, 177). For example, two-electron oxidation of 8-oxo-G (33) yields 5-hydroxy-8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanosine (34) (178). This compound can decompose to yield the spiroaminodihydantoin (35) via a 1,2-shift (178). Alternatively, hydrolysis of 34 generates the ureidoimidazoline (36), which undergoes decarboxylation to the guanidinohydantoin 37 (178). In nucleosides, guanidinohydantoin formation is favored at pH values < 7, while formation of the spiroaminohydantoin (35) is favored at pH values ≥ 7 (178–180). In the context of duplex DNA, oxidative degradation of 8-oxo-G residues, yields the guanidinohydantoin residue (37) as the major product (177) although this lesion may be prone to further decomposition to products such as imidazolone and oxazolone (181, 182). Guanidinohydantoin (37), spiroaminodihydantoin (35), and 8-oxo-G (33) are mutagenic lesions in duplex DNA (182–186).

Scheme 16.

5.7 Tandem Lesions

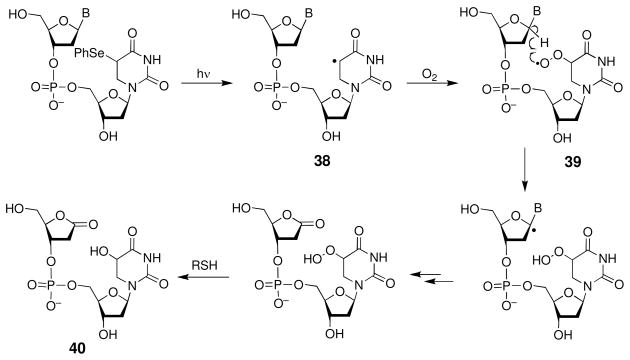

In some cases, initially-generated DNA radicals can undergo secondary reactions within the duplex. The resulting “tandem lesions”, comprised of cross-links or multiple adjacent damage sites, may present special challenges to DNA replication and repair systems (187, 188). For example, 5,6-dihydrothymidine radical (38, Scheme 17), in the presence of molecular oxygen, generates the corresponding peroxyl radical (39) that abstracts the C1′-hydrogen atom from the sugar residue on the 5′-side to produce a tandem lesion 40 consisting of a damaged pyrimidine base adjacent to a 2-deoxyribonolactone residue (189, 190).

Scheme 17.

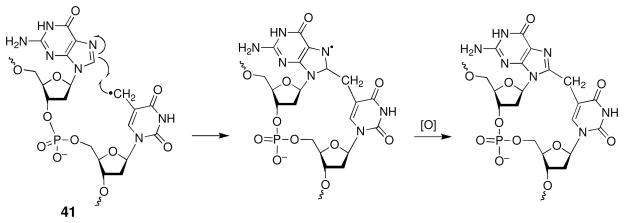

The 5-(2′-deoxyuridinyl)methyl radical (41, Scheme 18) generates intrastrand cross-links with adjacent purine residues (191, 192). This reaction is favored at 5′-GT sites (191). The 5-(2′-deoxycytidinyl)methyl radical can cross-link with guanine residues in a similar manner (193). The 5-(2′-deoxyuridinyl)methyl radical 41 has also been shown to forge an interstrand cross-link with the opposing deoxyadenosine (194, 195).

Scheme 18.

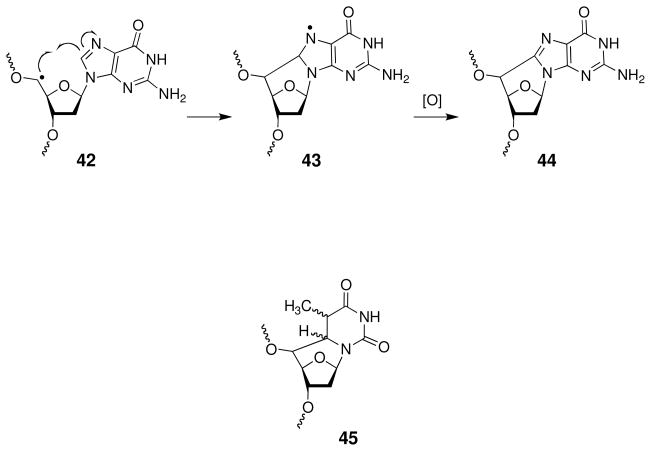

Under low oxygen conditions, C5′-sugar radicals can react with the base residue on the same nucleotide. In purine nucleotides, the carbon-centered radical 42 can add to the C8-position of the nucleobase (Scheme 19). Oxidation of the intermediate nucleobase radical 43 yields the 8,5′-cyclo-2′-deoxypurine lesion 44 (161, 164, 187, 188, 196–199). Similarly, in pyrimidine nucleotides, the C5′-radical can add to the C6-position of nucleobase. Reduction of the resulting radical intermediate yields the 5′,6-cyclo-5,6-dihydro-2′-deoxypyrimidine lesion 45 (200–202). The cyclolesions are chemically stable in DNA and may present special challenges to cellular repair systems (161, 164, 187, 188, 196–202).

Scheme 19.

6. Conclusion

Francis Crick wrote, “DNA is such an important molecule that is almost impossible to learn too much about it” (203). Indeed, today, more than 50 years after the primary chemical structure of DNA was established (1), there is a continuing need to develop our understanding of biologically-relevant DNA chemistry. Characterization of the chemical reactions of endogenous cellular chemicals, anticancer drugs, and mutagens with cellular DNA is important because the biological responses engendered by any given DNA-damaging agent are ultimately determined by the chemical structure of the damaged DNA. Improvements in methodologies for the detection and characterization of DNA damage such as LC/MS, high field NMR, and the synthesis of non-natural 2′-deoxyoligonucleotides have continued to drive the field forward (143, 204–207). DNA-damaging agents can elicit a wide variety of cellular responses including cell cycle arrest, up-regulation of DNA repair systems, apoptosis, or mutagenesis (7–13); however, the relationships between the structure of damaged DNA and the biological responses that ensue are not yet well understood. Advances in this area have the potential to yield both fundamental and practical advances in cell biology, predictive toxicology, and anticancer drug development.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to current and past research group members for helpful discussions on the topic of nucleic acid chemistry. I also acknowledge support from the NIH (CA 83925 and CA 119131) during the writing of this review.

Footnotes

In the interest of brevity, many of the reaction mechanisms shown in this review are schematic in nature. For example, protonation, deprotonation, and proton transfer steps may not be explicitly depicted or may not distinguish specific acid-base catalysis from general acid-base catalysis. In some cases, arrows indicating electron movement are used simply to direct the reader’s attention to sites where the “action” is occurring rather than to illustrate complete sequences of bond-making and bond-breaking.

Fishbein and coworkers provided an excellent discussion of the mechanistic origin of hard-soft acid base effects in DNA alkylation reactions. On page 1466 of reference 74, these authors note that “the low degree of covalency in the transition state for SN2 substitution on primary diazonium ions means that electrostatic stabilization of the transition state by the nucleophile will become a dominant interaction and this gives rise to enhanced oxygen atom alkylation by primary diazonium ions”.

References

- 1.Todd AR. Chemical structure of the nucleic acids. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1954;40:748–755. doi: 10.1073/pnas.40.8.748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Watson JD, Crick FHC. A structure for deoxyribose nucleic acid. Nature. 1953;171:737–738. doi: 10.1038/171737a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Venter JC. The sequence of the human genome. Science. 2001;291:1304–1351. doi: 10.1126/science.1058040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pennisi E. DNA’s cast of thousands. Science. 2003;300:282–285. doi: 10.1126/science.300.5617.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, Raff M, Roberts K, Walter P. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 4. Garland Science; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alberts B. DNA replication and recombination. Nature. 2003;421:431–435. doi: 10.1038/nature01407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou BBS, Elledge SJ. The DNA damage response: putting checkpoints in perspective. Nature. 2000;408:433–439. doi: 10.1038/35044005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Norbury CJ, Hickson ID. Cellular responses to DNA damage. Ann Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2001;41:367–401. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.41.1.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rouse J, Jackson SP. Interfaces between the detection, signaling, and repair of DNA damage. Science. 2002;297:547–551. doi: 10.1126/science.1074740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guengerich FP. Interactions of carcinogen-bound DNA with individual DNA polymerases. Chem Rev. 2006;106:420–452. doi: 10.1021/cr0404693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gates KS. Covalent Modification of DNA by Natural Products. In: Kool ET, editor. Comprehensive Natural Products Chemistry. Pergamon; New York: 1999. pp. 491–552. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wolkenberg SE, Boger DL. Mechanisms of in situ activation for DNA-targeting antitumor agents. Chem Rev. 2002;102:2477–2495. doi: 10.1021/cr010046q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hurley LH. DNA and its associated processes as targets for cancer therapy. Nature Rev Cancer. 2002;2:188–200. doi: 10.1038/nrc749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dickson KS, Burns CM, Richardson JP. Determination of the free-energy change for repair of a DNA phosphodiester bond. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:15828–15831. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M910044199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schroeder GK, Lad C, Wyman P, Williams NH, Wolfenden R. The time required for water attack at the phosphorus atom of simple phosphodiesters and of DNA. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:4052–4055. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510879103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williams NH, Wyman P. Base catalysed phosphate diester hydrolysis. Chem Comm. 2001:1268–1269. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cassano AG, Anderson VE, Harris ME. Evidence for direct attack by hydroxide in phosphodiester hydrolysis. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:10964–10965. doi: 10.1021/ja020823j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iche-Tarrat N, Barthelat JC, Rinaldi D, Vigroux A. Theoretical studies of hydroxide-catalyzed P-O cleavage reactions of neutral phosphate triesters and diesters in aqueous solution: examination of the change induced by H/Me substitution. J Phys Chem B. 2005;109:22570–22580. doi: 10.1021/jp0550558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Williams NH, Takasaki B, Wall M, Chin J. Structure and nuclease activity of simple dinuclear metal complexes: quantitative dissection of the role of metal ions. Acc Chem Res. 1999;32:485–493. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen W, Kitamura Y, Zhou JM, Sumaoka J, Komiyama M. Site-specific DNA hydrolysis by combining Ce(IV)/EDTA with monophosphate-bearing oligonucleotides and enzymatic ligation of the scission fragments. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:10285–10291. doi: 10.1021/ja048953a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Galburt EA, Stoddard BL. Catalytic mechanisms of restriction and homing endonucleases. Biochemistry. 2002;41:13851–13860. doi: 10.1021/bi020467h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nomura A, Sugiura Y. Sequence-specific and hydrolytic cleavage of DNA by zinc finger mutants. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:15374–15375. doi: 10.1021/ja045663l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sreedhara A, Freed JD, Cowan JA. Efficient Inorganic Deoxyribonucleases. Greater than 50-Million-Fold Rate Enhancement in Enzyme-Like DNA Cleavage. 2000;122:8814–8824. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shapiro R, Danzig M. Acidic hydrolysis of deoxycytidine and deoxyuridine derivatives. The general mechanism of deoxyribonucleoside hydrolysis. Biochemistry. 1972;11:23–29. doi: 10.1021/bi00751a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shapiro R, Klein RS. The deamination of cytidine and cytosine by acidic buffer solutions. Mutagenic implications. Biochemistry. 1966;5:2358–2362. doi: 10.1021/bi00871a026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lindahl T, Nyberg B. Heat-induced deamination of cytosine residues in deoxyribonucleic acid. Biochemistry. 1974;13:3405–3410. doi: 10.1021/bi00713a035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frederico LA, Kunkel TA, Shaw BR. A sensitive genetic asssay for detection of cytosine deamination: determination of rate constants and the activation energy. Biochemistry. 1990;29:2532–2537. doi: 10.1021/bi00462a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shen JC, Rideout WM, Jones PA. The rate of hydrolytic deamination of 5-methylcytosine in double-stranded DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:972–976. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.6.972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garrett ER, Tsau J. Solvolyses of cytosine and cytidine. J Pharm Sci. 1972;61:1052–1061. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600610703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Frederico LA, Kunkel TA, Shaw BR. Cytosine deamination in mismatched base pairs. Biochemistry. 1993;32:6523–6530. doi: 10.1021/bi00077a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karran P, Lindahl T. Hypoxanthine in deoxyribonucleic acid: generation of heat-induced hydrolysis of adenine residues and release in free form by a deoxyribonucleic acid glycosylase in calf thymus. Biochemistry. 1980;19:6005–6011. doi: 10.1021/bi00567a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lutsenko E, Bhagwat AS. Principle causes of hot spots for cytosine to thymine mutations at sites of cytosine methylation in growing cells. A model, its experimental support and implications. Mutation Res. 1999;437:11–20. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5742(99)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Duncan BK, Miller JH. Mutagenic deamination of cytosine residues in DNA. Nature. 1980;287:560–561. doi: 10.1038/287560a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dong M, Wang C, Deen WM, Dedon PC. Absence of 2′-deoxyoxanosine and presence of abasic sites in DNA exposed to nitric oxide at controlled physiological concentrations. Chem Res Toxicol. 2003;16:1044–1055. doi: 10.1021/tx034046s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shapiro R, Yamaguchi H. Nucleic acid reactivity and conformation. I. Deamination of cytosine by nitrous acid. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1972;281:501–506. doi: 10.1016/0005-2787(72)90150-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sowers LC, Sedwick WD, Ramsay Shaw B. Hydrolysis of N3-methyl-2′-deoxycytidine: model compound for reactivity of protonated cytosine residues in DNA. Mutation Res. 1989;215:131–138. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(89)90225-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peng W, Shaw BR. Accelerated deamination of cytosine residues in UV-induced cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers leads to CC-to-TT transitions. Biochemistry. 1996;35:10172–10181. doi: 10.1021/bi960001x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yebra MJ, Bhagwat AS. A cytosine methyltransferase converts 5-methylcytosine in DNA to thymine. Biochemistry. 1995;34:14752–14757. doi: 10.1021/bi00045a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zingg JM, Shen JC, Yang AS, Rapoport H, Jones PA. Methylation inhibitors can increase the rate of cytosine deamination by (cytosine-5)-DNA methyltransferase. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:3267–3275. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.16.3267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen H, Shaw BR. Kinetics of bisulfite-induced cytosine deamination in single-stranded DNA. Biochemistry. 1993;32:3535–3539. doi: 10.1021/bi00065a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shapiro R, DiFate V, Welcher M. Deamination of cytosine derivatives by bisulfite. Mechanism of the reaction. J Am Chem Soc. 1974;96:906–912. doi: 10.1021/ja00810a043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pham P, Bransteitter R, Goodman MF. Reward versus risk: DNA cytidine deaminases triggering immunity and disease. Biochemistry. 2005;44:2703–2715. doi: 10.1021/bi047481+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Samaranayake M, Bujnicki JM, Carpenter M, Bhagwat AS. Evaluation of molecular models for the affinity maturation of antibodies: roles of cytosine deamination by AID and DNA repair. Chem Rev. 2006;106:700–719. doi: 10.1021/cr040496t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kosaka H, Wishnok JS, Miwa M, Leaf CD, Tannenbaum SR. Nitrosation by stimulated macrophages, inhibitors, enhancers, and substrates. Carcinogenesis. 1989;10:563–566. doi: 10.1093/carcin/10.3.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wink DA, Kasprzak KS, Maragos CM, Elespuru RK, Misra M, Dunams TM, Cebula TA, Koch WH, Andrews AW, Allen JS. DNA deaminating ability and genotoxicity of nitric oxide and its progenitors. Science. 1991;254:1001–1003. doi: 10.1126/science.1948068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wuenschell GE, O’Connor TR, Termini J. Stability, miscoding potential, and repair of 2′-deoxyxanthosine in DNA: Implications for nitric oxide-induced mutagenesis. Biochemistry. 2003;42:3608–3616. doi: 10.1021/bi0205597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lucas LT, Gatehouse D, Shuker DEG. Efficient nitroso group transfer from N-nitrosoindoles to nucleotides and 2′-deoxyguanosine at physiological pH. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:18319–18326. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.26.18319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lindahl T, Karlstrom O. Heat-induced depyrimidination of deoxyribonucleic acid in solution. Biochemistry. 1973;12:5151–5154. doi: 10.1021/bi00749a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lindahl T, Nyberg B. Rate of depurination of native deoxyribonucleic acid. Biochemistry. 1972;11:3610–3618. doi: 10.1021/bi00769a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zoltewicz JA, Clark DF, Sharpless TW, Grahe G. Kinetics and mechanism of acid-catalyzed hydrolysis of some purine nucleosides. J Am Chem Soc. 1970;92:1741–1750. doi: 10.1021/ja00709a055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stivers JT, Jiang YJ. A mechanistic perspective on the chemistry of DNA repair glycosylases. Chem Rev. 2003;103:2729–2759. doi: 10.1021/cr010219b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nakamura J, Walker VE, Upton PB, Chiang SY, Kow YW, Swenberg JA. Highly sensitive apurinic/apyrimidinic site assay can detect spontaneous and chemically induced depurination under physiological conditions. Cancer Res. 1998;58:222–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nakamura J, Swenberg JA. Endogenous apurinic/apyrimidinic sites in genomic DNA of mammalian tissues. Cancer Res. 1999;59:2522–2526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Auerbach P, Bennett RAO, Bailey EA, Krokan HE, Demple B. Mutagenic specificity of endogenously generated abasic sites in Saccharomyces cerevisiae chromosomal DNA. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:17711–17716. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504643102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Boiteux S, Guillet M. Abasic sites in DNA: repair and biological consequences in Saccaromyces cerevisiae. DNA Repair. 2004;3:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wilde JA, Bolton PH, Mazumdar A, Manoharan M, Gerlt JA. Characterization of the equilibrating forms of the abasic site in duplex DNA using 17O-NMR. J Am Chem Soc. 1989;111:1894–1896. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lindahl T, Andersson A. Rate of chain breakage at apurinic sites in double-stranded deoxyribonucleic acid. Biochemistry. 1972;11:3618–3623. doi: 10.1021/bi00769a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Crine P, Verly WG. A study of DNA spontaneous degradation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1976;442:50–57. doi: 10.1016/0005-2787(76)90174-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McHugh PJ, Knowland J. Novel reagents for chemical cleavage at abasic sites and UV photoproducts in DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:1664–1670. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.10.1664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sugiyama H, Fujiwara T, Ura A, Tashiro T, Yamamoto K, Kawanishi S, Saito I. Chemistry of thermal degradation of abasic sites in DNA. mechanistic investigation on thermal DNA strand cleavage of alkylated DNA. Chem Res Toxicol. 1994;7:673–683. doi: 10.1021/tx00041a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Maxam AM, Gilbert W. Sequencing End-Labeled DNA with Base-Specific Chemical Cleavages. Methods Enzymol. 1980;65:499. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(80)65059-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mattes WB, Hartley JA, Kohn KW. Mechanism of DNA strand breakage by piperidine at sites of N7 alkylation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1986;868:71–76. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(86)90088-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bailly V, Derydt M, Verly WG. δ-Elimination in the repair of AP (apurinic/apyrimidinic) sites in DNA. Biochem J. 1989;261 doi: 10.1042/bj2610707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bailly V, Verly WG. Possible roles of β-elimination and δ-elimination reactions in the repair of DNA containing AP (apurinic/apyrimidinic) sites in mammalian cells. Biochem J. 1988;253:553–9. doi: 10.1042/bj2530553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dutta S, Chowdhury G, Gates KS. Interstrand crosslinks generated by abasic sites in duplex DNA. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:1852–1853. doi: 10.1021/ja067294u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rajski SR, Williams RM. DNA cross-linking agents as antitumor drugs. Chem Rev. 1998;98:2723–2795. doi: 10.1021/cr9800199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Noll DM, Mason TM, Miller PS. Formation and repair of interstrand crosslinks in DNA. Chem Rev. 2006;106:277–301. doi: 10.1021/cr040478b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Schärer OD. DNA interstrand crosslinks: natural and drug-induced DNA adducts that induce unique cellular responses. ChemBioChem. 2005;6:27–32. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200400287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Beranek DT. Distribution of methyl and ethyl adducts following alkylation with monofunctional alkylating agents. Mutation Res. 1990;231:11–30. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(90)90173-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Singer B, Grunberger D. Molecular biology of mutagens and carcinogens. Plenum; New York: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lo TL. Hard soft acids bases (HSAB) principle in organic chemistry. Chem Rev. 1975;75:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Moschel RC, Hudgins WR, Dipple A. Selectivity in nucleoside alkylation and aralkylation in relation to chemical carcinogenesis. J Org Chem. 1979;44:3324–3328. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Loechler EL. A violation of the Swain-Scott principle, and NOT SN1 versus SN2 reaction mechanisms, explains why carcinogenic alkylating agents can form different proportions of adducts at oxygen versus nitrogen in DNA. Chem Res Toxicol. 1994;7:277–280. doi: 10.1021/tx00039a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lu X, Heilman JM, Blans P, Fishbein JC. The structure of DNA dictates purine atom site selectivity in alkylation by primary diazonium ions. Chem Res Toxicol. 2005;18:1462–1470. doi: 10.1021/tx0501334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yang XL, Wang AHJ. Structural studies of atom-specific anticancer drugs acting on DNA. Pharm Ther. 1999;83:181–215. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(99)00020-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Fidder A, Moes GWH, Scheffer AG, ver der Schans GP, Baan RA, de Jong LPA, Benschop HP. Synthesis, characterization, and quantitation of the major adducts formed between sulfur mustard and DNA of calf thymus and human blood. Chem Res Toxicol. 1994;7:199–204. doi: 10.1021/tx00038a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zang H, Gates KS. Sequence specificity of DNA alkylation by the antitumor natural product leinamycin. Chem Res Toxicol. 2003;16:1539–1546. doi: 10.1021/tx0341658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Asai A, Hara M, Kakita S, Kanda Y, Yoshida M, Saito H, Saitoh Y. Thiol-mediated DNA alkylation by the novel antitumor antibiotic leinamycin. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:6802–6803. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mehta P, Church K, Williams J, Chen FX, Encell L, Shuker DEG, Gold B. The design of agents to control DNA methylation adducts. Enhanced major groove methylation of DNA by an N-methyl-N-nitrosourea functionalized phenyl neutral red intercalator. Chem Res Toxicol. 1996;9:939–948. doi: 10.1021/tx960007n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Vasquez KM, Narayanan L, Glazer PM. Specific mutations induced by triplex-forming oligonucleotides in mice. Science. 2000;290:530–533. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5491.530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wang YD, Dziegielewski J, Wurtz NR, Dziegielewska B, Dervan PB, Beerman TA. DNA crosslinking and biological activity of a hairpin polyamide-chlorambucil conjugate. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:1208–1215. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dickinson LA, Burnett R, Melander C, Edelson BS, Arora PS, Dervan PB, Gottesfeld JM. Arresting Cancer Proliferation by Small-Molecule Gene Regulation. Chem Biol. 2004;11:1583–1594. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Povsic TJ, Dervan PB. Sequence-specific alkylation of double-helical DNA by oligonucleotide-directed triple-helix formation. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:9428–9430. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Chaudhary AK, Nokubo M, Reddy GR, Yeola SN, Morrow JD, Blair IA, Marnett LJ. Detection of endogenous malondialdehyde-deoxyguanine adducts in human liver. Science. 1994;265:1580–1582. doi: 10.1126/science.8079172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

-

85.Cho Y-J, Kim H-Y, Huang H, Slutsky A, Minko IG, Wang H, Nechev LV, Kozekov ID, Kozekova A, Tamura P, Jacob J, Voehler M, Harris TM, Lloyd RS, Rizzo CJ, Stone MP. Spectroscopic Characterization of Interstrand Carbinolamine Cross-Links Formed in the 5′-CpG-3′ Sequence by the Acrolein-Derived

-OH-1,N 2-Propano-2′-deoxyguanosine. DNA Adduct. 2005;127:17686–17696. doi: 10.1021/ja053897e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

-OH-1,N 2-Propano-2′-deoxyguanosine. DNA Adduct. 2005;127:17686–17696. doi: 10.1021/ja053897e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] - 86.Tomasz M. Mitomycin C: small, fast and deadly (but very selective) Chem Biol. 1995;2:575–579. doi: 10.1016/1074-5521(95)90120-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Millard JT, Raucher S, Hopkins PB. Mechlorethamine cross-links deoxyguanosine residues at 5′-GNC sequences in duplex DNA fragments. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:2459–2460. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Le Pla RC, Guichard Y, Bowman KJ, Gaskell M, Farmer PB, Jones GDD. Further development of 32-P-postlabeling for the detection of alkylphosphotriesters: evidence for the long-term nonrandom persistence of ethyl-phosphotriester adducts in vivo. Chem Res Toxicol. 2004;17:1491–1500. doi: 10.1021/tx049798g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Beranek DT, Weis CC, Swenson DH. A comprehensive quantitative analysis of methylated and ethylated DNA using high-pressure liquid chromatography. Carcinogenesis. 1980;1:595–606. doi: 10.1093/carcin/1.7.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bernadou J, Blandin M, Meunier B. A one step synthesis of O6-methyl-2′-deoxyguanosine. Nucleosides & Nucleotides. 1983;2:459–464. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Guy A, Molko D, Wagrez L, Teoule R. Chemical synthesis of oligonucleotides containing N6-methyladenine residues in the GATC site. Helv Chim Acta. 1986;69:1034–40. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Perrino FW, Blans P, Harvey S, Gelhaus SL, McGrath C, Akman SA, Jenkins S, LaCourse WR, Fishbein JC. The N2-ethylguanine and the O6-ethyl- and O6-methylguanine lesions in DNA: contrasting responses from the “bypass” DNA polymerase nu and the replicative DNA polymerase alpha. Chem Res Toxicol. 2003;16:1616–1623. doi: 10.1021/tx034164f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wilds CJ, Noronha AM, Robidoux S, Miller PS. Mispair-aligned N3T-alkyl-N3T interstrand cross-linked DNA: synthesis and characterization of duplexes with interstrand cross-links of variable lengths. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:9257–9265. doi: 10.1021/ja0498540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Spratt TE, Campbell CR. Synthesis of oligonucleotides containing analogs of O6-methylguanine and reaction with O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase. Biochemistry. 1994;33:11364–11371. doi: 10.1021/bi00203a035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Fischhaber PL, Gall AS, Duncan JA, Hopkins PB. Direct demonstration in synthetic oligonucleotides that N,N′-bis(2-chloroethyl)-nitrosourea cross-links N1 of deoxyguanosine to N3 of deoxycytidine on opposite strands of duplex DNA. Cancer Res. 1999;17:4363–4368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Singer B, Kroger M, Carrano M. O2- and O4-Alkyl Pyrimidine Nucleosides: Stability of the Glycosyl Bond and of the Alkyl Group as a Function of pH. Biochemistry. 1978;17:1246–1250. doi: 10.1021/bi00600a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bignami M, O’Driscoll M, Aquilina G, Karran P. Unmasking a killer: DNA O6-methylguanine and the cytotoxicity of methlylating agents. Mutat Res. 2000;462:71–82. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5742(00)00016-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ellison KS, Dogliotti E, Connors E, Basu AK, Essigmann JM. Site-specific mutagenesis by O6-alkylguanines located in the chromosomes of mammalian cells: influence of the mammalian O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltranferase. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:8620–8624. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.22.8620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Pauly GT, Moschel RC. Mutagenesis by O6-methyl-, O6-ethyl, and O6-benzylguanine and O4-methylthymine in human cells: effects of O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase and mismatch repair. Chem Res Toxicol. 2001;14:894–900. doi: 10.1021/tx010032f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Loeb LA, Preston BD. Mutagenesis by apurinic/apyrimidinic sites. Ann Rev Genet. 1986;20:201–230. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.20.120186.001221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Lawley PD, Brookes P. Further studies on the alkylation of nucleic acids and their constituent nucleotides. Biochem J. 1963;89:127–138. doi: 10.1042/bj0890127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lawley PD, Warren W. Removal of minor methylation products 7-methyladenine and 3-methylguanine from DNA of E. coli treated with dimethyl sulfate. Chem-Biol Interact. 1976;12:211–220. doi: 10.1016/0009-2797(76)90100-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Gates KS, Nooner T, Dutta S. Biologically relevant chemical reactions of N7-alkyl-2′-deoxyguanosine adducts in DNA. Chem Res Toxicol. 2004;17:839–856. doi: 10.1021/tx049965c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Shipova K, Gates KS. A fluorimetric assay for the spontaneous release of an N7-alkylguanine residue from duplex DNA. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2005;15:2111–2113. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.02.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Nooner T, Dutta S, Gates KS. Chemical properties of the leinamycin 2′-deoxyguanosine adduct. Chem Res Toxicol. 2004;17:942–949. doi: 10.1021/tx049964k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Guthrie RD, Jencks WP. IUPAC recommendations for the representation of reaction mechanisms. Accounts Chem Res. 1989;22:343–349. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Moschel RC, Hudgins WR, Dipple A. Substituent-induced effects on the stability of benzylated guanosines: model systems for the factors influencing the stability of carcinogen-modified nucleic acids. J Org Chem. 1984;49:363–372. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Muller N, Eisenbrand G. The influence of N7-substitutents on the stability of N7-alkylated guanosines. Chem-Biol Int. 1985;53:173–181. doi: 10.1016/s0009-2797(85)80094-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Lawley PD, Brookes P. Acidic dissociation of 7,9-dialkylguanines and its possible relation to mutagenic properties of alkylating agents. Nature. 1961;192:1081–2. doi: 10.1038/1921081b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Haines JA, Reese CB, Todd L. Methylation of guanosine and related compounds with diazomethane. J Chem Soc. 1962:5281. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Townsend LB, Robins RK. Ring cleavage of purine nucleosides to yield possible biogenetic precursors of pteridines and riboflavin. J Am Chem Soc. 1963;85:242–243. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Box HC, Lilgam KT, French JB, Potienko G, Alderfer JL. 13-C-NMR characterization of alkylated derivatives of guanosine, adenosine, and cytidine. Carbohydrates, Nucleosides, Nucleotides. 1981;8:189. [Google Scholar]

- 113.Chetsanga CJ, Bearie B, Makaroff C. Alkaline opening of imidazole ring of 7-methylguanosine 1. Analysis of the resulting pyrimidine derivatives. Chem-Biol Int. 1982;41:217–233. doi: 10.1016/0009-2797(82)90091-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Chetsanga CJ, Bearie B, Makaroff C. Alkaline opening of imidazole ring of 7-methyguanosine. 1 Analysis of the resulting pyrimidine derivatives. Chem-Biol Interact. 1982;41:217–233. doi: 10.1016/0009-2797(82)90091-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Hecht SM, Adams BL, Kozarich JW. Chemical transformations of 7,9-disubstituted purines and related heterocycles. Selective reduction of imines and immonium salts. J Org Chem. 1976;13:2303–2311. doi: 10.1021/jo00875a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Humphreys WG, Guengerich FP. Structure of formamidopyrimidine adducts as determined by NMR using specifically 15-N labeled guanosine. Chem Res Toxicol. 1991;4:632–636. doi: 10.1021/tx00024a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Hendler S, Furer E, Srinivasan PR. Synthesis and chemical properties of monomers and polymer containing 7-methylguanine and an investigation of their substrate or template properties form bacterial deoxyribonucleic acid or ribonucleic acid polymerases. Biochemistry. 1970;9:4141–4153. doi: 10.1021/bi00823a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Mao H, Deng Z, Wang F, Harris TM, Stone MP. An intercalated and thermally stable FAPY adduct of aflatoxin B1 in a DNA duplex: Structural refinement from 1H NMR. Biochemistry. 1998;37:4374–4387. doi: 10.1021/bi9718292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Croy RG, Wogan GN. Temporal patterns of covalent DNA adducts in rat liver after single and multiple doses of aflatoxin B1. Cancer Res. 1981;41:197–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Beranek DT, Weiss CC, Evans FE, Chetsanga CJ, Kadlubar FF. Identification of N5-methyl-N5-formyl-2,5,6-triamino-4-hydroxypyrimidine as a major adduct in rat liver DNA after treatment with the carcinogens, N,N-dimethylnitrosamine or 1,2-dimethylhydrazine. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1983;110:625–631. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(83)91195-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Kadlubar FF, Beranek DT, Weiss CC, Evans FE, Cox R, Irving CC. Characterization of the purine ring-opened 7-methylguanine and its persistence in rat bladder epithelial DNA after treatment with the carcinogen N-methylnitrosourea. Carcinogenesis. 1984;5:587–592. doi: 10.1093/carcin/5.5.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Kristov PP, Brown KL, Kozekov ID, Stone MP, Harris TM, Rizzo CJ. Site-specific synthesis and characterization of oligonucleotides containing an N6-(2-deoxy-D-erythro-pentofuranosyl)-2,6-diamino-3,4-dihydro-4-oxo-5-N-methylformamidopyrimidine lesion, the ring-opened product from N7-methylation of deoxyguanosine. Chem Res Toxicol. 2008;21:2324–2333. doi: 10.1021/tx800352a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Greenberg MM, Hantosi Z, Wiederholt CJ, Rithner CD. Studies on N4-(2-Deoxy-D-pentofuranosyl)-4,6-diamino-5-formamidopyrimidine (Fapy-dA) and N6-(2-Deoxy-D-pentofuranosyl)- 6-diamino-5-formamido-4-hydroxypyrimidine (Fapy-dG) Biochemistry. 2001;40:15856–15861. doi: 10.1021/bi011490q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Brown KL, Deng JZ, Iyer RS, Voehler MW, Stone MP, Harris CM, Harris TM. Unraveling the aflatoxin-FAPY conundrum: structural basis for differential replicative processing of isomeric forms of the formamidopyrimidine-type DNA adduct of aflatoxin B1. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:15188–15199. doi: 10.1021/ja063781y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Patro JN, Haraguchi K, Delaney MO, Greenberg MM. Probing the configurations of formamidopyrimidine lesions Fapy-dA and Fapy-dG in DNA using endonuclease IV. Biochemistry. 2004;43 doi: 10.1021/bi049035s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Bergdorf LT, Carrel T. Synthesis, stability, and conformation of the formamidopyrimidine G DNA lesion. Chem Eur J. 2002;8:293–301. doi: 10.1002/1521-3765(20020104)8:1<293::aid-chem293>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Fujii T, Itaya T. The Dimroth rearrangement in the adenine series: a review updated. Heterocycles. 1998;48:359–390. [Google Scholar]

- 128.Barlow T, Takeshita J, Dipple A. Deamination and Dimroth rearrangement of deoxyadenosine-styrene oxide adducts in DNA. Chem Res Toxicol. 1998;11:838–845. doi: 10.1021/tx980038d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Macon JB, Wolfenden R. 1-Methyladenosine Dimroth rearrangement and reversible reduction. Biochemistry. 1968;7:3453–3458. doi: 10.1021/bi00850a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Barlow T, Ding J, Vouros P, Dipple A. Investigation of hydrolytic deamination of 1-(2-hydroxy-1-phenylethyl)adenosine. Chem Res Toxicol. 1997;10:1247–1249. doi: 10.1021/tx970091m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Koskinnen M, Hemminki K. Separate deamination mechanisms for isomeric styrene oxide induced N1-adenine adducts. Org Lett. 1999;1:1233–1235. doi: 10.1021/ol9909031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Barlow T, Dipple A. Formation of deminated products in styrene oxide reactions with deoxycytidine. Chem Res Toxicol. 1999;12:883–886. doi: 10.1021/tx990070n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Breen AP, Murphy JA. Reactions of oxyl radicals with DNA. Free Rad Biol Med. 1995;18:1033–1077. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(94)00209-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Greenberg MM. Investigating nucleic acid damage processes via independent generation of reactive intermediates. Chem Res Toxicol. 1998;11:1235–1248. doi: 10.1021/tx980174i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Pogozelski WK, Tullius TD. Oxidative strand scission of nucleic acids: routes initiated by hydrogen atom abstraction from the sugar moiety. Chem Rev. 1998;98:1089–1107. doi: 10.1021/cr960437i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Pratviel G, Bernadou J, Meunier B. Carbon-hydrogen bonds of DNA sugar units as targets for chemical nucleases and drugs. Angew Chem Int Ed Eng. 1995;34:746–769. [Google Scholar]

- 137.von Sonntag C, Hagen U, Schon-Bopp A, Schulte-Frohlinde D. Radiation-induced strand breaks in DNA: chemical and enzymatic analysis of end groups and mechanistic aspects. Adv Radiat Biol. 1981;9:109–142. [Google Scholar]

- 138.Balasubramanian B, Pogozelski WK, Tullius TD. DNA strand breaking by the hydroxyl radical is governed by the accessible surface areas of the hydrogen atoms of the DNA backbone. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:9738–9743. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.17.9738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Chowdhury G, Junnutula V, Daniels JS, Greenberg MM, Gates KS. DNA strand damage analysis provides evidence that the tumor cell-specific cytotoxin tirapazamine produces hydroxyl radical and acts as a surrogate for O2. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:12870–12877. doi: 10.1021/ja074432m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Carter KN, Greenberg MM. Tandem lesions are the major products resulting from a pyrimidine nucleobase radical. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:13376–13378. doi: 10.1021/ja036629u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Hwang JT, Greenberg MM. Kinetics and stereoselectivity of thiol trapping of deoxyuridin-1′-yl in biopolymers and their relationship to the formation of premutagenic alpha-deoxynucleotides. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:4311–4315. [Google Scholar]

- 142.Emmanuel CJ, Newcomb M, Ferreri C, Chatgilialoglu C. Kinetics of 2′-deoxyuridin-1′-yl radical reactions. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:2927–2928. [Google Scholar]

- 143.Greenberg MM. Elucidating DNA damage and repair processes by independently generating reactive and metastable intermediates. Org Biomol Chem. 2007;5:18–30. doi: 10.1039/b612729k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Hwang JT, Tallman KA, Greenberg MM. The reactivity of the 2-deoxyribonolactone lesion in single-stranded DNa and its implication in reaction mechanisms of DNA damage and repair. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:3805–3810. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.19.3805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Roupioz Y, Lhomme J, Kotera M. Chemistry of the 2-deoxyribonolactone lesion in oligonucleotides: cleavage kinetics and products analysis. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:9129–9135. doi: 10.1021/ja025688p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Zheng Y, Sheppard TL. Half-life and DNA strand scission products of 2-deoxyribonolactone oxidative DNA damage lesions. Chem Res Toxicol. 2004;17:197–207. doi: 10.1021/tx034197v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Kroeger KM, Hashimoto M, Kow YW, Greenberg MM. Cross-linking of 2-deoxyribonolactone and its beta-elimination product by base excision repair enzymes. Biochemistry. 2003;42:2449–2455. doi: 10.1021/bi027168c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Hashimoto M, Greenberg MM, Kow YW, Hwang JT, Cunningham RP. The 2-deoxyribonolactone lesion produced in DNA by neocarzinostatin and other damaging agents forms cross-links with the base-excision repair enzyme endonuclease III. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:3161–3162. doi: 10.1021/ja003354z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Junnotula V, Sarkar U, Sinha S, Gates KS. Initiation of DNA strand cleavage by 1,2,4-benzotriazine 1,4-dioxides: mechanistic insight from studies of 3-methyl-1,2,4-benzotriazine 1,4-dioxide. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:XXXX–XXXX. doi: 10.1021/ja8049645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Dussy A, Meggers E, Giese B. Spontaneous cleavage of 4′-DNA radicals under aerobic conditions: apparent discrepancy between trapping rates and cleavage products. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:7399–7403. [Google Scholar]

- 151.Giese B, Dussy A, Meggers E, Petretta M, Schwitter U. Conformation, lifetime, and repair of 4′-DNA radicals. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:11130–11131. [Google Scholar]

- 152.Hildebrand K, Schulte-Frohlinde D. Time-resolved EPR studies on the reaction rates of peroxyl radicals of poly(acrylic acid) and of calf thymus DNA with glutathione. Re-examination of a rate constant for DNA. Int J Radiat Biol. 1997;71:377–385. doi: 10.1080/095530097143996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Giese B, Beyrich-Graf X, Erdmann P, Petretta M, Schwitter U. The chemistry of single-stranded 4′-DNA radicals: influence of the radical precursor on anaerobic and aerobic strand cleavage. Chem Biol. 1995;2:367–375. doi: 10.1016/1074-5521(95)90217-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Dedon PC, Plastaras JP, Rouzer CA, Marnett LJ. Indirect mutagenesis by oxidative DNA damage: formation of the pyrimidopurinone adduct of deoxyguanosine by base propenal. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:11113–11116. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.19.11113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Plastaras JP, Riggins JN, Otteneder M, Marnett LJ. Reactivity and mutagenicity of endogenous DNA oxopropenylating agents: base propenals, malondialdehyde, and N-oxopropenyllysine. Chem Res Toxicol. 2000;13:1235–1242. doi: 10.1021/tx0001631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.von Sonntag C. Free-Radical-Induced DNA Damage and Its Repair. Springer-Verlag; Berlin: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 157.Burrows CJ, Muller JG. Oxidative nucleobase modifications leading to strand scission. Chem Rev. 1998;98:1109–1151. doi: 10.1021/cr960421s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Gajewski E, Rao G, Nackerdien Z, Dizdaroglu M. Modification of DNA bases in mammalian chromatin by radiation-generated free radicals. Biochemistry. 1990;29:7876–7882. doi: 10.1021/bi00486a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Wallace SS. Biological consequences of free radical-damaged DNA bases. Free Rad Biol Med. 2002;33:1–14. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)00827-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Dizdaroglu M. Chemical determination of oxidative DNA damage by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Methods Enzymol. 1994;234:3–16. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(94)34072-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Dizdaroglu M, Jaruga P, Birincioglu M, Rodriguez H. Free radical-induced damage to DNA: mechanisms and measurement. Free Rad Biol Med. 2002;32:1102–1115. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)00826-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Evans MD, Dizdaroglu M, Cooke MS. Oxidative DNA damage and disease: induction, repair, and significance. Mutation Res. 2004;567:1–61. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2003.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Jovanovic SV, Simic MG. Mechanism of OH radical reactions with thymine and uracil derivatives. J Am Chem Soc. 1986;108:5968–5972. doi: 10.1021/ja00279a050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Birincioglu M, Jaruga P, Chowdhury G, Rodriguez H, Dizdaroglu M, Gates KS. DNA Base Damage by the Antitumor Agent 3-Amino-1,2,4-benzotriazine 1,4-Dioxide (Tirapazamine) J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:11607–11615. doi: 10.1021/ja0352146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Schuchmann MN, von Sonntag C. The radiolysis of uracil in oxygenated aqueous solutions. A study by product analysis and pulse radiolysis. J Chem Soc Perkin. 1983;2:1525–1531. [Google Scholar]

- 166.Carter KN, Greenberg MM. Independent generation and study of 5,6-dihydro-2′-deoxyuridin-6-yl, a member of the major family of reactive intermediates formed in DNA from the effects of gamma-radiolysis. J Org Chem. 2003;68:4275–4280. doi: 10.1021/jo034038g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Wagner JR, van Lier JE, Berger M, Cadet J. Thymidine hydroperoxides: structural assignment, conformational features, and thermal decomposition in water. J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116:2235–2242. [Google Scholar]

- 168.Steenken S, Jovanovic SV. How Easily Oxidizable Is DNA? One-Electron Reduction Potentials of Adenosine and Guanosine Radicals in Aqueous Solution. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:617–618. [Google Scholar]

- 169.Lewis FD, Letsinger RL, Wasielewski MR. Dynamics of photoinduced charge transfer and hole transport in synthetic DNA hairpins. Acc Chem Res. 2001;34:159–170. doi: 10.1021/ar0000197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170.Candeias LP, Steenken S. Reaction of HO. with Guanine Derivatives in Aqueous Solution: Formation of Two Different Redox-Active OH-Adduct Radicals and Their Unimolecular Transformation Reactions Properties of G(-H) Chem Eur J. 2000;6:475–484. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1521-3765(20000204)6:3<475::aid-chem475>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171.Douki T, Spinelli S, Ravanat JL, Cadet J. Hydroxyl radical-induced degradation of 2′-deoxyguanosine under reducing conditions. J Chem Soc Perkin. 1999;2:1875–1880. [Google Scholar]

- 172.Wiederholt CJ, Greenberg MM. Fapy-dG instructs Klenow Exo- to misincorporate deoxyadenosine. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:7278–7279. doi: 10.1021/ja026522r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 173.Haraguchi K, Delaney MO, Wiederholt CJ, Sambandam A, Hantosi Z, Greenberg MM. Synthesis and characterization of oligodeoxynucleotides containing formamidopyrimidine lesions and nonhydrolyzable analogues. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:3263–3269. doi: 10.1021/ja012135q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 174.Haraguchi K, Greenberg MM. Synthesis of Oligonucleotides Containing Fapy⋄dG (N6- (2-Deoxy-a,b-D-erythro-pentofuranosyl)-2,6- diamino-4-hydroxy-5-formamidopyrimidine) J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:8636–8637. doi: 10.1021/ja0160952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 175.Delaney MO, Weiderholt CJ, Greenberg MM. Fapy-dA induces nucleotide misincorporation tranlesionally by a DNA polymerase. Angew Chem. 2002;41:771–3. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020301)41:5<771::aid-anie771>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 176.Bodepudi V, Shibutani S, Johnson F. Synthesis of 2′-deoxy-7,8-dihydro-8-oxo-guanosine and 2′-deoxy-7,8-dihydro-8-oxoadenosine and their incorporation into oligomeric DNA. Chem Res Toxicol. 1992;5:608–617. doi: 10.1021/tx00029a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 177.Burrows CJ, Muller JG, Kornyushyna O, Luo W, Duarte V, Leipold MD, David SS. Structure and potential mutagenicity of new hydantoin products from guanosine and 8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanine oxidation by transition metals. Environ Health Perspect Supp. 2002;110:713–717. doi: 10.1289/ehp.02110s5713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 178.Luo W, Muller JG, Rachlin EM, Burrows CJ. Characterization of Hydantoin Products from One-Electron Oxidation of 8-Oxo-7,8-dihydroguanosine in a Nucleoside Model. Chem Res Toxicol. 2001;14:927–938. doi: 10.1021/tx010072j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 179.Luo W, Muller EM, Burrows CJ. Characterization of spiroiminodihydantoin as a product of one-electron oxidation of 8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanosine. Org Lett. 2000;2:613–616. doi: 10.1021/ol9913643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 180.Ye Y, Muller JG, Luo W, Mayne CL, Shallop AJ, Jones RA, Burrows CJ. Formation of 13C-, 15N, and 18O-labeled guanidinohydantoin from guanosine oxidation with singlet oxygen. Implications for structure and mechanism. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:13926–13927. doi: 10.1021/ja0378660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 181.Matter B, Malejka-Giganti D, Cxallany AS, Tretyakova N. Quantitative analysis of the oxidative DNA lesion, 2,2-diamino-4-(2-deoxy-beta-D-erythro-pentofuranosyl)amino-5-(2H)-oxazolone (oxazolone), in vitro and in vivo by isotope dilution-capilliary HPLC-ESI-MS/MS. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:5449–5460. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 182.Neeley WL, Essigmann JM. Mechanisms of formation, genotoxicity, and mutation of guanine oxidation products. Chem Res Toxicol. 2006;19:491–505. doi: 10.1021/tx0600043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 183.Kuchino Y, Mori F, Kasai H, Inoue H, Iwai S, Miura K, Ohtsuka E, Nishimura S. Misreading of DNA templates containing 8-hydroxyguanosine at the modified base and at adjacent residues. Nature. 1987;327:77–79. doi: 10.1038/327077a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 184.Kornyushyna O, Berges AM, Muller JG, Burrows CJ. In vitro nucleotide misinsertion opposite the oxidized guanosine lesions spiroiminohydantoin and guanidinohydantoin and DNA synthesis past the lesions using Escherichia coli DNA polymerase I (Klenow fragment) Biochemistry. 2002;41:15304–15314. doi: 10.1021/bi0264925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 185.Henderson PT, Delaney JC, Muller JG, Neeley WL, Tannenbaum SR, Burrows CJ, Essigmann JM. The hydantoin lesions formed from oxidation of 7,8-dihydro-8-oxoguanine are potent sources of replication errors in vivo. Biochemistry. 2003;42:9257–9262. doi: 10.1021/bi0347252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 186.Shibutani S, Takeshita M, Grollman AP. Insertion of specific bases during DNA synthesis past the oxidation damaged base 8-oxodG. Nature. 1991;349:431–434. doi: 10.1038/349431a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 187.Brooks PJ, Wise DS, Berry DA, Kosmoski JV, Smerdon MJ, Somers RL, Mackie H, Spoonde AY, Ackerman EJ, Coleman K, Tarone RE, Robbins JH. The oxidative lesion 8,5′-cyclo-2′-deoxyadenosine is repaired by the nucleotide excision repair pathway and blocks gene expression in mammalian cells. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:22355–22362. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002259200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 188.Kuraoka I, Bender C, Romieu A, Cadet J, Wood R, Lindahl T. Removal of oxygen free-radical-induced 5′,8-purine cyclodeoxynucleosides from DNA by the nucleotide excision repair pathway in human cells. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:3832–3837. doi: 10.1073/pnas.070471597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 189.Greenberg MM, Barvian MR, Cook GP, Goodman BK, Matray TJ, Tronche C, Venkatesan H. DNA damage induced via 5,6-dihydrothymid-5-yl in single-stranded oligonucleotides. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:1828–1839. [Google Scholar]

- 190.Tallman KA, Greenberg MM. Oxygen-dependent DNA damage amplification involving 5,6-dihydrothymidin-5-yl in a structurally minimal system. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:5181–5187. doi: 10.1021/ja010180s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 191.Bellon S, Ravanat JL, Gasparutto D, Cadet J. Cross-linked thymine-purine base tandem lesions: synthesis, characterization, and measurement in gamma-irradiated DNA. Chem Res Toxicol. 2002;15:598–606. doi: 10.1021/tx015594d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 192.Box HC, Budzinski EE, Dawdzik JB, Wallace JC, Iijima H. Tandem lesions and other products in X-irradiated DNA oligomers. Radiat Res. 1998;149:433–439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 193.Zhang Q, Wang Y. Generation of 5-(2′-deoxycytidyl)methyl radical and the formation of intrastrand cross-link lesions in oligodeoxyribonucleotides. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:1593–1603. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 194.Ding H, Greenberg MM. gamma-Radiolysis and hydroxyl radical produce interstrand cross-links in DNA involving thymidine. Chem Res Toxicol. 2007;20:1623–1628. doi: 10.1021/tx7002307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 195.Ding H, Majumdar A, Tolman JR, Greenberg MM. Multinuclear NMR and kinetic analysis of DNA interstrand cross-link formation. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:17981–17987. doi: 10.1021/ja807845n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 196.Dizdaroglu M, Jaruga P, Rodriguez H. Identification and quantification of 8,5′-cyclo-2′-deoxyadenosine in DNA by LC/MS. Free Rad Biol Med. 2001;30:774–784. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00464-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 197.Romieu A, Gasparutto D, Molko D, Cadet J. Site-specific introduction of (5′S)-5′-8-cyclo-2′-deoxyadenosine into oligodeoxyribonucleotides. J Org Chem. 1998;63:5245–5249. [Google Scholar]

- 198.Jaruga P, Birincioglu M, Rodriguez H, Dizdaroglu M. Mass spectrometric assays for the tandem lesion 8,5′-cyclo-2′-deoxyguanosine in mammalian DNA. Biochemistry. 2002;41:3703–3711. doi: 10.1021/bi016004d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 199.Kuraoka I, Robins P, Masutani C, Hanaoka F, Gasparutto D, Cadet J, Wood RD, Lindahl T. Oxygen free radical damage to DNA: Translesion synthesis by human DNA polymerase n and resistance to exonuclease action at cyclopurine deoxynucleoside residues. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:49283–49288. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107779200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 200.Muller E, Gasparutto D, Jaquinod M, Romieu A, Cadet J. Chemical and biochemical properties of oligonucleotides that contain 5′S, 6S-cyclo5,6-dihydro-2′-deoxyuridine and 5′S, 6S-cyclo-5,6,-dihydrothymidine, two main radiation-induced degradation products of pyrimidine 2′-deoxyribonucleosides. Tetrahedron. 2000;56:8689–8701. [Google Scholar]

- 201.Muller E, Gasparutto D, Cadet J. Chemical synthesis and biochemical properties of oligonucleotides that contain the (5′S,5S,6S)-5′,6-cyclo-5-hydroxy-5,6-dihydro-2′-deoxyuridine DNA lesion. ChemBioChem. 2002;3:534–542. doi: 10.1002/1439-7633(20020603)3:6<534::AID-CBIC534>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 202.Romieu A, Gasparutto D, Cadet J. Synthesis and characterization of oligodeoxyribonucleotides containing the two 5R and 5S diastereomers of 5′S, 6S-5′,6-cyclo-5,6-dihydrothymidine; radiation-induced tandem lesions of thymidine. J Chem Soc Perkin. 1999;1:1257–1263. [Google Scholar]

- 203.Crick FHC, Wang JC, Bauer WR. Is DNA really a double helix? J Mol Biol. 1979;129:449–457. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(79)90506-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 204.Sturla SJ. DNA adduct profiles: chemical approaches to addressing the biological impact of DNA damage from small molecules. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2007;11:293–299. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2007.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 205.Cadet J, Douki T, Gasparutto D, Ravanat JL. Oxidative damage to DNA: formation measurement and biochemical features. Mutat Res. 2003;531:5–23. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2003.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 206.Jaruga P, Gueldal K, Dizdaroglu M. Measurement of formamidopyrimidines in DNA. Free Rad Biol Med. 2008;45:1601–1609. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 207.Butenandt J, Burgdorf LT, Carell T. Synthesis of DNA lesions and DNA-lesion-containing oligonucleotides for DNA-repair studies. Synthesis. 1999:1085–1105. [Google Scholar]