Abstract

Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibition (ACEi) ameliorates the development of hypertension and the intrarenal ANG II augmentation in ANG II-infused mice. To determine if these effects are associated with changes in the mouse intrarenal renin-angiotensin system, the expression of angiotensinogen (AGT), renin, ACE, angiotensin type 1 receptor (AT1R) mRNA (by quanitative RT-PCR) and protein [by Western blot (WB) and/or immunohistochemistry (IHC)] were analyzed. C57BL/6J male mice (9–12 wk old) were distributed as controls (n = 10), ANG II infused (ANG II = 8, 400 ng·kg−1·min−1 for 12 days), ACEi only (ACEi = 10, lisinopril, 100 mg/l), and ANG II infused + ACEi (ANG II + ACEi = 11). When compared with controls (1.00), AGT protein (by WB) was increased by ANG II (1.29 ± 0.13, P < 0.05), and this was not prevented by ACEi (ACEi + ANG II, 1.31 ± 0.14, P < 0.05). ACE protein (by WB) was increased by ANG II (1.21 ± 0.08, P < 0.05), and it was reduced by ACEi alone (0.88 ± 0.07, P < 0.05) or in combination with ANG II (0.80 ± 0.07, P < 0.05). AT1R protein (by WB) was increased by ANG II (1.27 ± 0.06, P < 0.05) and ACEi (1.17 ± 0.06, P < 0.05) but not ANG II + ACEi [1.15 ± 0.06, not significant (NS)]. Tubular renin protein (semiquantified by IHC) was increased by ANG II (1.49 ± 0.23, P < 0.05) and ACEi (1.57 ± 0.15, P < 0.05), but not ANG II + ACEi (1.10 ± 0.15, NS). No significant changes were observed in AGT, ACE, or AT1R mRNA. In summary, reduced responses of intrarenal tubular renin, ACE, and the AT1R protein to the stimulatory effects of chronic ANG II infusions, in the presence of ACEi, are associated with the effects of this treatment to ameliorate augmentations in blood pressure and intrarenal ANG II content during ANG II-induced hypertension.

Keywords: angiotensin-converting enzyme, angiotensinogen, renin, lisinopril

angiotensin (ANG) II-induced hypertension in mice, as in other species, is characterized by an increased intrarenal ANG II content to levels greater than can be explained by equilibration with the systemic circulation (13, 24). This observation indicates the presence of active mechanisms augmenting the ANG II concentration in the kidney. Because this organ expresses all components of the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) (16, 18, 22, 23) and there is an augmentation of intrarenal angiotensinogen expression (13, 20) as well as the persistence of renin (13) and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) activities (12, 14) during ANG II-induced hypertension, it has been postulated that endogenous ANG II synthesis is an important mechanism contributing to the augmentation of intrarenal ANG II during ANG II-induced hypertension.

Recently, we subjected chronic ANG II-infused mice to systemic ACE inhibition to determine the role of ACE-derived ANG II formation in the development of hypertension and increased intrarenal ANG II levels observed in this model (12). Our results showed that ANG II-infused mice treated with an ACE inhibitor (ACEi) had markedly attenuated increases in arterial pressure and lower intrarenal ANG II levels when compared with mice treated only with ANG II. Thus it was demonstrated that ACE-derived endogenous ANG II formation plays a cardinal role in the generation of high intrarenal ANG II levels and hypertension in ANG II-infused mice. Although administration of an ACEi reduces the activity of this enzyme systemically, based on the facts that ACE is the main pathway for ANG I conversion to ANG II in the mouse kidney (4) and the presence of systemic renin suppression with sustained intrarenal renin activity during chronic ANG II infusions (13), it was concluded that it is likely that ACE activity in the kidneys, and therefore local ANG II generation in this organ, is a major contributor to the generation of high intrarenal ANG II content in ANG II-induced hypertension.

In the present study, the expressions of ACE and other components of RAS [angiotensinogen, renin, and the angiotensin type 1 receptor (AT1R)] were determined in the kidneys of these mice to gain further insight into the effects of ACEi on the intrarenal RAS during chronic ANG II. The objective was to establish if changes in the expression of the intrarenal RAS are associated with the effects of ACE inhibition to ameliorate the increases of intrarenal ANG II and blood pressure during chronic ANG II infusions.

METHODS

Animal Preparation and Sample Collection

All protocols were approved by the Tulane University Health Sciences Center Animal Care and Use Committee. C57BL/6J male mice (9–12 wk old) were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME) and maintained in a temperature-controlled room in a 12:12-h light-dark cycle with free access to food (Na+ content 0.4%) and water.

Mice were randomly distributed to the following groups: mice chronically infused with ANG II at a rate of 400 ng·kg−1·min−1 via subcutaneously implanted osmotic minipumps (Alzet 1002; Durect, Cupertino, CA) (n = 8); sham-operated mice used as controls (n = 10); mice treated with the ACEi lisinopril [at a dose of 100 mg/l in the drinking water starting 48 h before minipump implantation (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO)] (n = 10); and ANG II-infused mice treated concomitantly with lisinopril (n = 11). Mice were followed for 12 days during which the systolic blood pressure was recorded every 6 days using a Visitech BP2000 system (Visitech Systems, Apex, NC). On day 13, mice were killed by conscious decapitation, and the kidneys were collected and processed as described before (20, 26). To corroborate the effects of the different treatments on the blood pressure, changes in the mean arterial pressure were also assessed by telemetry as previously described (12, 13).

Intrarenal RAS Expression Studies

mRNA expression as determined by quantitative real-time RT-PCR.

RNA ISOLATION.

Whole kidney extracts (5––10 mg) were used to isolate total RNA using a commercial kit following the manufacturer's recommendations including DNase treatment (RNeasy Mini kit; Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Total RNA was then tested for quality and quantity.

QUANTITATIVE RT-PCR.

mRNA (20 ng) was used to coamplify the gene of interest (angiotensinogen, ACE, or AT1aR) and β-actin (used as normalizer) in the same reaction. Primers and Taqman probes specific for mouse angiotensinogen and β-actin have been described before (13). The oligonucleotide sequences for ACE and the AT1aR are as follows: ACE forward primer 5′-CAC TAT GGG TCC GAG TAC AT-3′, reverse primer 5′-ATC ATA GAT GTT GGA CCA GG-3′, probe 5′-CTG CCC ATC TGC TAG GGA ACA T-3′ (5′: 6-FAM 3′: BHQ1); AT1aR: forward primer 5′-AGA ACA CCA ATA TCA CTG TTT G-3′, reverse primer 5′-TAG CTG GTA AGA ATG ATT AGG A-3′, and probe 5′-CAT AGG ACT GGG CCT AAC CAA GAA-3′ (5′: 6-FAM 3′: BHQ1). Each sample was assayed in triplicate in a Stratagene MX 3000P multiplex quantitative PCR system using Stratagene PCR master mix II (Stragagene, La Jolla, CA) with reaction conditions as described elsewhere (13). Assay quality was determined based on standard curve values of R2 ≥ 0.99, Y ≤ 3.9 and an efficiency ≥80 and ≤110%. Quantitative values were extrapolated from individual standard curves for the gene of interest and the normalizer.

Protein expression as determined by Western blot and immunohistochemistry.

PROTEIN ISOLATION.

Renal tissues were homogenized in 500–1,000 μl of lysis buffer (50 mM Tris·HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 0.02% sodium azide, 0.1% lauryl sulfate, 1% Igepal CA-630, and 0.5% sodium deoxycholate) with 1/400 proteinase inhibitor cocktail, 1 mM sodium vanadate, and 2 mM EDTA (all reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich). After homogenization, samples were sonicated and centrifuged to collect the supernatant. Protein concentration was determined using Bradford's method (Bio-Rad protein assay; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

WESTERN BLOTTING.

Five micrograms of protein of each sample were subjected to gel electrophoresis and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes following protocols as described previously (21). Membranes were probed with one of the following primary antibodies: IgG anti-angiotensinogen, a polyclonal rabbit antibody raised against mouse/rat angiotensinogen, 1:200 dilution (code no. 99666; IBL, Takasaki, Japan); IgG anti-ACE, a polyclonal goat antibody raised against the NH2 terminus of ACE, 1:1,000 dilution (SC-12184; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA); IgG anti-AT1R, a rabbit polyclonal antibody against the NH2 terminus of the AT1R, 1:1,000 dilution (SC-1173; Santa Cruz Biotechnology); and IgG anti- β-actin, a mouse monoclonal antibody raised against a peptide derived from 1–100 resides of human β-actin, 1:1,000 dilution (Ab8226; Abcam; Cambridge, MA). Fluorescent-tagged anti-IgG antibodies were used to identify the primary binding (IRDye-labeled antibodies from Li-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE). Fluorescent intensity was collected in two separate channels using an infrared Odyssey system (Licor Biosciences). The intensity of each protein of interest is expressed as arbitrary units (AU) normalized to β-actin detected in the same membrane.

IMMUNOHISTOCHEMISTRY.

Representative 3-μM kidney slices from each mouse were subjected to antigen retrieval and exposed to primary antibodies as follows: for angiotensinogen, a polyclonal rabbit antibody raised against mouse/rat angiotensinogen was used in a dilution of 1:4,000 for 15 min (see above); for ACE, a polyclonal goat antibody against the COOH terminus of ACE was used in a 1:150 dilution for 60 min (SC-12187; Santa Cruz Biotechnology); for AT1R, a rabbit polyclonal antibody was used in 1:250 dilution for 60 min. These protocols were performed to completion in an Autostainer Plus system (DakoCytomation). Immunoreactivity was semiquantitatively evaluated in a blind manner as described elsewhere (21). Briefly, examination was performed using a microscope with ×200 magnification (Olympus BX51-TRF) and an integrated digital camera system (Magnafire SP). In every field, the sum of intensities of positive areas was calculated and averaged by the field area using Image Pro-plus software (Media Cybernetics, Bethesda, MD). The field area was calculated as the total field area minus empty spots in the field. The average of intensities of the 5–20 fields represented the total intensity per slide and therefore per mouse and is expressed as AU normalized against the average in controls.

AT1R analysis was extended to semiquantification of AT1R immunoreactivity of glomeruli (g), tubules/interstitium (t/i), and vascular structures (bv) since it has been shown that they can be differentially regulated during chronic ANG II infusions (16). Because there are several subpopulations of renin-expressing cells in the kidney that respond differently during ANG II-dependent hypertension (25, 26), we chose not to analyze mRNA and protein expression in total kidney extracts. Instead, a detailed immunohistochemistry analysis was performed as follows: paraffin-embedded kidney sections (3 μM) were immunostained by the immunoperoxidase technique by sequential incubation with normal blocking rabbit serum, an anti-renin primary antibody (rabbit renin polyclonal antibody generously provided by Dr. Tadashi Inagami, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN) at 1:4,000 concentration for 90 min, a biotin-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse secondary antibody for 30 min, and a rabbit horseradish peroxidase Polymer kit (Biocare Medical), followed by 0.1% 3,3′-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (Sigma) to visualize peroxidase activity. Intensities of renin immunoreactivities (ratio of the sum of density of positive cells per area) in collecting duct cells were semiquantified in up to 20 different microscopic fields per tissue section from three to four mice per mice group. Images were captured with a Nikon digital camera (DS-U2/L2 USB) attached to a Nikon Eclipse 50i microscope and analyzed using the NIS Elements AR version 3.0 (Nikon, Melville, NY). The results are expressed in intensity densitometric units (AU) of the relative intensity normalized to the renin immunostaining average of the sham group. In addition, total number of glomeruli with positive juxtaglomerular renin immunoreactivity were screened and expressed relative to the total number of glomeruli count per mouse kidney section, and the results are expressed in percentages.

Statistical Analyses

All data are presented as means ± SE. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's post tests were applied. A value of P < 0.05 was regarded as significant.

RESULTS

The effects of ANG II infusions and ACEi on mean arterial pressure (MAP) and intrarenal and plasma ANG II concentrations have been reported previously (12). Briefly, when compared with 24-h MAP values and intrarenal ANG II values in controls (110 ± 1.0 mmHg and 524 ± 60 fmol/g, respectively), chronic ANG II infusions caused significant increases (141 ± 3.7 and 998 ± 143, P < 0.05 for each). These changes were ameliorated by the combination of ANG II plus the ACEi [114 ± 7.4 and 484 ± 102, not significant (NS) for each vs. controls]. ACEi alone did not cause any significant changes in these parameters (102 ± 3.0 and 397.3 ± 80, NS).

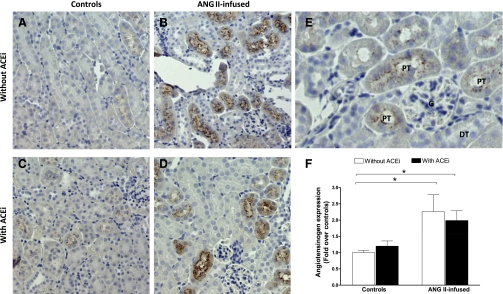

Intrarenal Angiotensinogen Expression

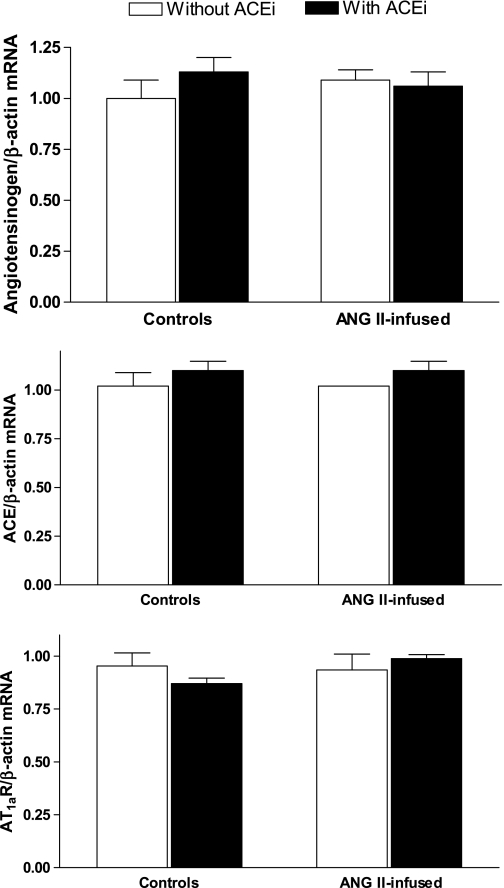

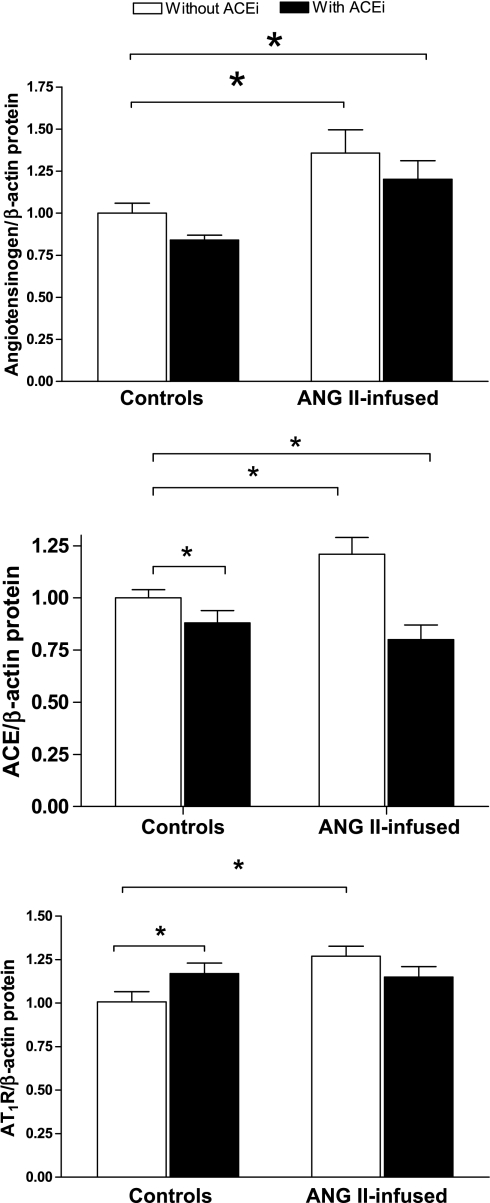

No significant differences were observed in the mRNA expression of angiotensinogen in the kidney homogenates among the different groups (Fig. 1, top). When compared with controls (1.00 ± 0.09), neither ACE inhibition (1.13 ± 0.07, NS) nor chronic ANG II infusions (1.09 ± 0.05, NS) had a significant effect on angiotensinogen mRNA expression. This was also the case for the combination of ANG II plus ACEi (1.06 ± 0.07, NS). On the other hand, angiotensinogen protein expression in kidney homogenates, as quantified by Western blot (Fig. 2, top), was significantly increased by ANG II infusions alone when compared with controls (1.31 ± 0.14 vs. 1.00 ± 0.05, P < 0.05), and this effect was not prevented by coadministration of ACEi (ANG II + ACEi, 1.20 ± 0.11, P < 0.05). ACEi alone did not have an effect on angiotensinogen expression (0.84 ± 0.03, NS). The immunohistochemistry analysis demonstrates that angiotensinogen is primarily expressed in proximal tubules (Fig. 3, A–F, and see Fig. 3E for a magnification). Furthermore, the semiquantitative analysis confirms that, when compared with control mice (Fig. 3A), there was a strong upregulation of angiotensinogen caused by ANG II infusions (2.26 ± 0.52, P < 0.05, Fig. 3B) that was not prevented by concomitant ACE inhibition (1.99 ± 0.30-fold over controls, P < 0.05, Fig. 3D). ACEi alone did not have an effect on angiotensinogen expression (1.20 ± 0.16, NS, Fig. 3C).

Fig. 1.

Effects of chronic ANG II infusions (400 ng·kg−1·min−1) with or without angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibition on mouse intrarenal angiotensinogen (top), ACE (middle), and angiotensin type 1a receptor (AT1aR, bottom) mRNA expression as determined by quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR). ACEi, ACE inhibitor (lisinopril, 100 mg/l in the drinking water). *P < 0.05.

Fig. 2.

Effects of chronic ANG II infusions with or without ACE inhibition on mouse intrarenal angiotensinogen (top), ACE (middle), and AT1aR (bottom) protein expression as determined by Western blot. *P < 0.05.

Fig. 3.

Immunohistochemistry analysis of the effect of chronic ANG II infusions with or without ACE inhibition on intrarenal angiotensinogen expression. Images are representative of controls (A), ANG II-infused mice (400 ng·kg−1·min−1) (B), mice treated only with an ACEi (lisinopril, 100 mg/l; C), and ANG II-infused mice cotreated with an ACEi (D). Also shown are magnifications of positive-stained proximal tubules next to a glomerulus and distal tubules negative for angiotensinogen staining (E) and the semiquantitative analysis. PT, proximal tubule; G, glomerulus; DT, distal tubule. *P < 0.05.

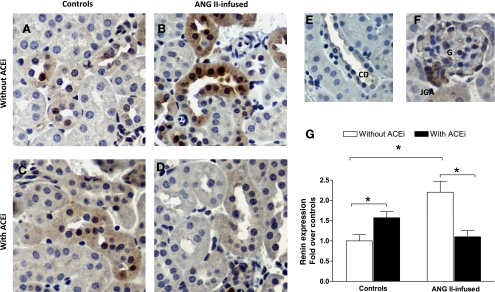

Intrarenal Renin Expression

Renin immunoreactivity (Fig. 4) was observed throughout the kidney in cortex and medulla specifically in the juxtaglomerular apparatus, glomeruli, connecting tubules and collecting ducts, and to a much lesser extent in the brush border of proximal tubule cells (Fig. 4, E and F). In analyzing juxtaglomerular renin, the percentage of glomeruli with juxtaglomerular renin immunoreactivity was significantly reduced by ANG II infusions (17.03 ± 7.54%, P < 0.05) when compared with controls (38.62 ± 3.22%). In turn, ACE inhibition caused an increase in the percentage of glomeruli positive for juxtaglomerular renin (71.52 ± 2.83%, P < 0.05). On the other hand, the combination of ANG II infusions and ACEi was not statistically different from controls (45.93 ± 8.84%, NS), but it was higher than that observed in mice treated only with ANG II.

Fig. 4.

Immunohistochemistry analysis of the effect of chronic ANG II infusions with or without ACE inhibition on collecting duct renin expression. Images are representative of controls (A), ANG II-infused mice (400 ng·kg−1·min−1) (B), mice treated only with an ACEi (lisinopril, 100 mg/l; C), and ANG II-infused mice cotreated with an ACEi (D). Also shown are magnifications of positive-stained collecting ducts (E), a glomerulus with a juxtaglomerular apparatus (F), and the results of the semiquantitative analysis (G). CD, collecting duct; JGA, juxtaglomerular apparatus. *P < 0.05.

The semiquantitative analysis of collecting duct renin expression (Fig. 4G) demonstrated that, when compared with control mice (normalized as 1.00 ± 0.15, Fig. 4A), collecting duct renin expression in ANG II-infused mice was increased significantly (2.20 ± 0.28, P < 0.05, Fig. 4B). ACE inhibition also caused a significant increase in collecting duct renin (1.57 ± 0.15, P < 0.05, Fig. 4C). However, ANG II-infused mice cotreated with an ACEi failed to display a significant increase in collecting duct renin (1.10 ± 0.15, NS, Fig. 4D).

Intrarenal ACE Expression

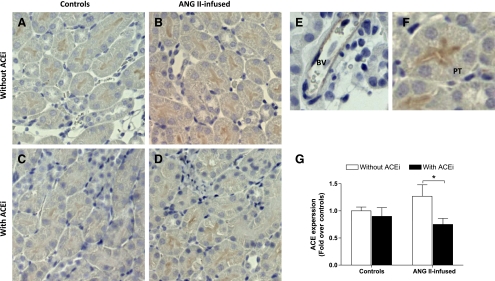

No significant differences were observed in the mRNA expression of ACE in the kidney homogenates from the different groups (Fig. 1, middle). Neither chronic ANG II infusions (0.80 ± 0.13 vs. 1.00 ± 0.08 in controls, NS) nor ACE inhibition (1.10 ± 0.05 vs. 1.00 ± 0.08 in controls, NS) had an effect on ACE mRNA expression. This was also the case for the combination of ANG II plus ACEi (0.95 ± 0.09, NS). However, ACE protein expression compared with control mice by Western blot (1.00 ± 0.06, 195-kDa band) was significantly increased by chronic ANG II infusions (1.21 ± 0.08, P < 0.05). In turn, ACE inhibition significantly reduced ACE expression when administered alone (0.88 ± 0.07, NS vs. controls) or in combination with ANG II (0.80 ± 0.07, NS vs. controls). When the latter group was compared with mice receiving only ANG II, a significant difference was observed. Immunohistochemistry analysis (Fig. 5) performed using an antibody targeted against tissue ACE demonstrated predominant expression in the brush border of proximal tubules and the endothelium of arterioles (Fig. 5, E and F). The semiquantitative analysis of ACE immunoreactivity did not show any significant differences between ANG II-infused mice (1.21 ± 0.14, NS, Fig. 5B), ACEi-treated mice (0.94 ± 0.10, NS, Fig. 5C), or ANG II-infused mice treated with the ACEi (0.83 ± 0.07, NS, Fig. 5D) vs. controls (1.00 ± 0.11, Fig. 5A). However, there was a significant difference in ACE expression between ANG II-infused mice and mice treated with the combination of ANG II plus the ACEi.

Fig. 5.

Immunohistochemistry analysis of the effect of chronic ANG II infusions with or without ACE inhibition on ACE expression. Images are representative of controls (A), ANG II-infused mice (400 ng·kg−1·min−1) (B), mice treated only with an ACEi (lisinopril, 100 mg/l; C), and ANG II-infused mice cotreated with an ACEi (D). Also shown are magnifications of a blood vessel (E) and a proximal tubule (F) and the results of the semiquantitative analysis (G). BV, blood vessel. *P < 0.05.

Intrarenal AT1R Expression

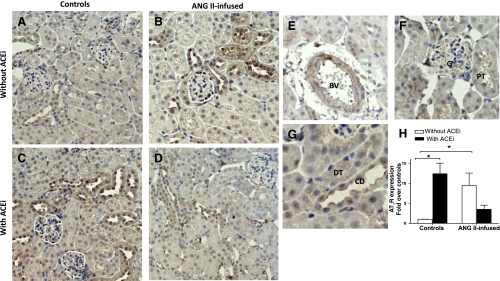

No significant differences were observed in the mRNA expression of the AT1aR [the predominant form of the AT1R in the mouse kidney (3)] in tissue homogenates from the different groups (Fig. 1, bottom). When compared with controls (normalized as 1.00 ± 0.06), neither ANG II infusions (0.96 ± 0.10, NS) nor ACE inhibition (0.91 ± 0.03 vs. 1.00, NS) had an effect on AT1aR mRNA expression. This was also the case for the combination of ANG II plus ACEi (1.04 ± 0.02, NS). When AT1R protein expression was compared by Western blot, chronic ANG II infusions caused a significant increase (1.27 ± 0.06, P < 0.05) vs. controls (normalized as 1.00 ± 0.06). ACE inhibition also augmented AT1R expression (1.17 ± 0.06, P < 0.05). However, the combination of ANG II infusions and ACEi did not cause any significant changes when compared with controls (1.15 ± 0.06, NS). With the use of immunohistochemistry (Fig. 6), AT1R expression was observed extensively throughout the kidneys (Fig. 6, A–D) on glomeruli and proximal tubules cells (Fig. 6F), interstitial cells and, more strongly, on blood vessels (Fig. 6E), distal tubules, and collecting ducts (Fig. 6G). The semiquantitative analysis (Fig. 6H) demonstrated that, when compared with controls (normalized as 1.00 ± 0.20, Fig. 6A), chronic ANG II infusions cause a significant increase in AT1R expression (9.47 ± 2.65, P < 0.05, Fig. 6B); ACEi also strongly induced AT1R expression (12.41 ± 2.65-fold over controls, P < 0.05, Fig. 6C). However, the combination of ANG II plus the ACEi failed to induce such changes (3.5 ± 1.04, NS, Fig. 6D). This same pattern of changes was observed when analyzing glomerular staining and tubule/interstitium staining or blood vessels. When compared with controls (normalized as 1), ANG II caused significant increases as follows: 4.93 ± 1.64 (glomeruli), 4.98 ± 1.7 (t/i), and 3.8 ± 1.1 (bv). ACEi also induced AT1R expression: 6.73 ± 1.4 (glomeruli), 6.13 ± 1.3 (t/i), and 4.77 ± 0.86 (bv). In turn, the combination of ANG II plus the ACEi did not cause any significant changes: 2.87 ± 0.7 (glomeruli), 2.73 ± 0.7 (t/i), and 2.96 ± 0.5 (bv).

Fig. 6.

Immunohistochemistry analysis of the effect of chronic ANG II infusions with or without ACE inhibition on AT1R expression. Images are representative of controls (A), ANG II-infused mice (400 ng·kg−1·min−1) (B), mice treated only with an ACEi (lisinopril, 100 mg/l; C), and ANG II-infused mice cotreated with an ACEi (D). Also shown are magnification of different structures (E–G), and the results of the semiquantitative analysis (H). *P < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

In our previous study, it was shown that ACE inhibition reduces the increases in blood pressure and intrarenal ANG II content observed in ANG II-infused mice. Novel findings from this report demonstrate that these effects are associated with changes in the intrarenal RAS, since treatment with an ACEi ameliorated the actions of chronic ANG II infusions to induce the expression of components of the intrarenal RAS, in particular collecting duct renin, ACE, and the AT1R.

These observations are important because it is likely that most of the endogenous ANG II generation during ANG II-induced hypertension in mice occurs in the kidneys. In support of this, it has been reported that, while plasma renin activity is suppressed, intrarenal angiotensinogen is increased while kidney renin (13) and ACE (12) activities are maintained. Furthermore, in this study, it was observed that the expression of ACE, collecting duct renin, and the AT1R are also augmented. Regardless of what factor(s) might be regulating the expression of the various components of the intrarenal RAS during chronic ANG II infusions with or without ACE inhibition, the effects appear to be mostly posttranscriptional since no significant changes were observed at the mRNA levels of any of the explored genes.

With reference to intrarenal angiotensinogen, the present results confirm that chronic ANG II infusions increase its protein abundance (13, 19, 20). Previously, we reported that chronic ANG II infusions increase mouse intrarenal angiotensinogen mRNA. The reason for our failure to confirm such finding may be due to the fact that, for the present analysis, total kidney extracts were used instead of just cortex extracts as in the previous study (13), causing a reduced sensitivity to changes in angiotensinogen mRNA. We also observed that concomitant ACE inhibition failed to prevent angiotensinogen protein augmentation during chronic ANG II infusions. This suggests that the increases in circulating ANG II caused by the infusion are sufficient to augment angiotensinogen protein expression. Another possibility is that chronic ANG II infusions increase the intrarenal concentrations of other factors, like interleukin-6 (29) and free oxygen radicals (17) that modulate angiotensinogen expression and that act independently of ACE inhibition. It is also probable that angiotensinogen originating from the liver accumulates in the kidney and that this effect is not prevented by ACE inhibition. In any case, the presence of an augmented angiotensinogen demonstrates that the effects of ACE inhibition are not due to the lack of substrate for generation of ANG I.

Several studies have demonstrated that renin is expressed in other cell populations besides the juxtaglomerular apparatus in the kidney (25–28). In agreement with these reports, we observed renin expression in glomeruli, connecting tubule cells, and collecting duct cells. With regards to the last two cell populations, and considering the limitations of our technique as well as the presence of renin staining in the medulla, at the moment we can only conclude that renin is present in collecting ducts. Our immunohistochemistry analysis, although semiquantitative in nature, also reported changes in renin expression. In accord to what has been published, in response to ACE inhibition we observed an increased juxtaglomerular renin (2) and collecting duct renin (10). In the case of juxtaglomerular renin, it has been suggested that this effect is mediated by the loss of ANG II negative feedback and/or reductions in blood pressure (7, 11). Whether these mechanisms operate in the same fashion in collecting duct renin has yet to be determined. Although chronic ANG II infusions suppress juxtaglomerular renin (26), they enhance collecting duct renin expression. This dissociation has been observed in other models of ANG II-dependent hypertension (25, 26) and might be important in view of the findings reported by Zhao et al. (31). These authors recently demonstrated that, in ANG II-infused mice there is an enhanced distal sodium reabsorption associated with increased urinary ANG II concentrations that is independent of aldosterone. Therefore, the presence of an increased collecting duct renin expression might be a key factor for local generation of ANG II that in turn causes the observed increases in distal sodium reabsorption.

In the kidneys, ACE is mainly expressed in the vasculature and in the brush border of proximal tubule cells (1). In response to ACE inhibition, rats and humans display an increase in kidney ACE content (5). However, we did not observe either ACE mRNA or ACE protein increases in ACEi-treated mice. The reasons for these differences are unknown, but may be due to interspecies differences, dose, or length of ACE inhibition. In analyzing ANG II effects on ACE expression, Harrison-Bernard et al. (16) reported an increase in proximal tubule ACE binding in ANG II-infused rats. Vio and Jeanneret (30) reported that in several models of hypertension and kidney injury there is an increased total ACE that is explained by augmentations in proximal tubule ACE and also interstitial ACE. In agreement with these findings, our Western blot results confirm an increase in total ACE expression in ANG II-infused mice. However, our immunohistochemistry data show that ACE expression is strongest in the brush border of proximal tubule cells with little or no ACE in the interstitium even after chronic ANG II infusions.

In response to ACE inhibition, we observed a significant increase in total AT1R protein; this has been long recognized as a compensatory mechanism for the reduction in ANG II generation and has been explained by the low levels of ANG II upregulating AT1R expression (8, 32). However, we observed that chronic ANG II infusions also increase intrarenal AT1R expression. This paradoxical increase of intrarenal AT1Rs in mice has also been observed in other models of ANG II-dependent hypertension like Ren-2 transgenic rats (33). Furthermore, ANG II-infused rats display sustained total AT1R expression (15, 16) that, although not higher, also supports the notion of a maintained AT1R expression during ANG II-dependent hypertension. Regulation of the AT1R in the kidneys during chronic ANG II infusions plays a fundamental role because their presence is cardinal for the development of hypertension in this model (6).

The results from this study illustrate the complexity of actions of ACEi on the intrarenal RAS as they prevent upregulation of ACE, collecting duct renin, and the AT1R observed in ANG II-infused mice. In the case of ACE, modulating its expression seems to be independent of ANG II (5). Therefore, the absence of ACE upregulation in ANG II-infused mice cotreated with the ACEi may be due to accumulation of a different ACE substrate. Another possibility is that, by blocking local ANG II production, ANG I can be used to generate ANG-(1–7) that in turn averts ACE upregulation. In support of this, Ferrario et al. (9) demonstrated that, during chronic ACE inhibition, Lewis rats display an increased ACE2 activity and higher urinary ANG-(1–7). These observations may be also pertinent to the effects of ACE inhibition on the expression of collecting duct renin and the intrarenal AT1R. Although these effects are difficult to explain, they emphasize the need for a better understanding of the mechanisms controlling the activity and expression of the intrarenal RAS.

In summary, the results presented here demonstrate that chronic ANG II infusions increase collecting duct renin, ACE, and the AT1R expression in the mouse kidney. Furthermore, ACE inhibition ameliorates the effects of chronic ANG II infusions to induce the expression of these RAS components. Such effects help to explain that, in addition to reductions on ACE activity, ACE inhibition effectively reduces ANG II-induced increases in blood pressure and intrarenal ANG II content during chronic ANG II infusions.

GRANTS

This study was supported by National Institute of Health Grants P20RR-017659 from the Institutional Award (IdeA) program of NCRR, HL-26371, DK-072408, and 1K99DK-083455.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest are declared by the authors.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alhenc-Gelas F, Baussant T, Hubert C, Soubrier F, Corvol P. The angiotensin converting enzyme in the kidney. J Hypertens Suppl 7: S9–S14, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barrett GL, Morgan TO, Smith M, Alcorn D, Aldred P. Effect of converting enzyme inhibition on renin synthesis and secretion in mice. Hypertension 14: 385–395, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burson JM, Aguilera G, Gross KW, Sigmund CD. Differential expression of angiotensin receptor 1A and 1B in mouse. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 267: E260–E267, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campbell DJ, Alexiou T, Xiao HD, Fuchs S, McKinley MJ, Corvol P, Bernstein KE. Effect of reduced angiotensin-converting enzyme gene expression and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition on angiotensin and bradykinin peptide levels in mice. Hypertension 43: 854–859, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Costerousse O, Allegrini J, Clozel JP, Menard J, Alhenc-Gelas F. Angiotensin I-converting enzyme inhibition but not angiotensin II suppression alters angiotensin I-converting enzyme gene expression in vessels and epithelia. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 284: 1180–1187, 1998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crowley SD, Gurley SB, Herrera MJ, Ruiz P, Griffiths R, Kumar AP, Kim HS, Smithies O, Le TH, Coffman TM. Angiotensin II causes hypertension and cardiac hypertrophy through its receptors in the kidney. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 17985–17990, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crowley SD, Gurley SB, Oliverio MI, Pazmino AK, Griffiths R, Flannery PJ, Spurney RF, Kim HS, Smithies O, Le TH, Coffman TM. Distinct roles for the kidney and systemic tissues in blood pressure regulation by the renin-angiotensin system. J Clin Invest 115: 1092–1099, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Douglas JG. Angiotensin receptor subtypes of the kidney cortex. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 253: F1–F7, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferrario CM, Jessup J, Gallagher PE, Averill DB, Brosnihan KB, Ann Tallant E, Smith RD, Chappell MC. Effects of renin-angiotensin system blockade on renal angiotensin-(1–7) forming enzymes and receptors. Kidney Int 68: 2189–2196, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gilbert RE, Wu LL, Kelly DJ, Cox A, Wilkinson-Berka JL, Johnston CI, Cooper ME. Pathological expression of renin and angiotensin II in the renal tubule after subtotal nephrectomy. Implications for the pathogenesis of tubulointerstitial fibrosis. Am J Pathol 155: 429–440, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gomez RA, Lynch KR, Chevalier RL, Everett AD, Johns DW, Wilfong N, Peach MJ, Carey RM. Renin and angiotensinogen gene expression and intrarenal renin distribution during ACE inhibition. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 254: F900–F906, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gonzalez-Villalobos RA, Satou R, Seth DM, Semprun-Prieto LC, Katsurada A, Kobori H, Navar LG. Angiotensin-converting enzyme-derived angiotensin II formation during angiotensin II-induced hypertension. Hypertension 53: 351–355, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gonzalez-Villalobos RA, Seth DM, Satou R, Horton H, Ohashi N, Miyata K, Katsurada A, Tran DV, Kobori H, Navar LG. Intrarenal angiotensin II and angiotensinogen augmentation in chronic angiotensin II-infused mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 295: F772–F779, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guan S, Fox J, Mitchell KD, Navar LG. Angiotensin and angiotensin converting enzyme tissue levels in two-kidney, one clip hypertensive rats. Hypertension 20: 763–767, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harrison-Bernard LM, El-Dahr SS, O'Leary DF, Navar LG. Regulation of angiotensin II type 1 receptor mRNA and protein in angiotensin II-induced hypertension. Hypertension 33: 340–346, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harrison-Bernard LM, Zhuo J, Kobori H, Ohishi M, Navar LG. Intrarenal AT1 receptor and ACE binding in ANG II-induced hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 282: F19–F25, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hsieh TJ, Fustier P, Wei CC, Zhang SL, Filep JG, Tang SS, Ingelfinger JR, Fantus IG, Hamet P, Chan JS. Reactive oxygen species blockade and action of insulin on expression of angiotensinogen gene in proximal tubular cells. J Endocrinol 183: 535–550, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ingelfinger JR, Jung F, Diamant D, Haveran L, Lee E, Brem A, Tang SS. Rat proximal tubule cell line transformed with origin-defective SV40 DNA: autocrine ANG II feedback. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 276: F218–F227, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kobori H, Harrison-Bernard LM, Navar LG. Enhancement of angiotensinogen expression in angiotensin II-dependent hypertension. Hypertension 37: 1329–1335, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kobori H, Harrison-Bernard LM, Navar LG. Expression of angiotensinogen mRNA and protein in angiotensin II-dependent hypertension. J Am Soc Nephrol 12: 431–439, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kobori H, Prieto-Carrasquero MC, Ozawa Y, Navar LG. AT1 receptor mediated augmentation of intrarenal angiotensinogen in angiotensin II-dependent hypertension. Hypertension 43: 1126–1132, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koike G, Krieger JE, Jacob HJ, Mukoyama M, Pratt RE, Dzau VJ. Angiotensin converting enzyme and genetic hypertension: cloning of rat cDNAs and characterization of the enzyme. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 198: 380–386, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moe OW, Ujiie K, Star RA, Miller RT, Widell J, Alpern RJ, Henrich WL. Renin expression in renal proximal tubule. J Clin Invest 91: 774–779, 1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Navar LG, Nishiyama A. Why are angiotensin concentrations so high in the kidney? Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 13: 107–115, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prieto-Carrasquero MC, Botros FT, Pagan J, Kobori H, Seth DM, Casarini DE, Navar LG. Collecting duct renin is upregulated in both kidneys of 2-kidney, 1-clip goldblatt hypertensive rats. Hypertension 51: 1590–1596, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prieto-Carrasquero MC, Harrison-Bernard LM, Kobori H, Ozawa Y, Hering-Smith KS, Hamm LL, Navar LG. Enhancement of collecting duct renin in angiotensin II-dependent hypertensive rats. Hypertension 44: 223–229, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rohrwasser A, Ishigami T, Gociman B, Lantelme P, Morgan T, Cheng T, Hillas E, Zhang S, Ward K, Bloch-Faure M, Meneton P, Lalouel JM. Renin and kallikrein in connecting tubule of mouse. Kidney Int 64: 2155–2162, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rohrwasser A, Morgan T, Dillon HF, Zhao L, Callaway CW, Hillas E, Zhang S, Cheng T, Inagami T, Ward K, Terreros DA, Lalouel JM. Elements of a paracrine tubular renin-angiotensin system along the entire nephron. Hypertension 34: 1265–1274, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Satou R, Gonzalez-Villalobos RA, Miyata K, Ohashi N, Katsurada A, Navar LG, Kobori H. Costimulation with angiotensin II and interleukin 6 augments angiotensinogen expression in cultured human renal proximal tubular cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 295: F283–F289, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vio CP, Jeanneret VA. Local induction of angiotensin-converting enzyme in the kidney as a mechanism of progressive renal diseases. Kidney Int Suppl S57–S63, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhao D, Seth DM, Navar LG. Enhanced distal nephron sodium reabsorption in chronic angiotensin II-infused mice. Hypertension 54: 120–126, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhuo J, Alcorn D, McCausland J, Casley D, Mendelsohn FA. In vivo occupancy of angiotensin II subtype 1 receptors in rat renal medullary interstitial cells. Hypertension 23: 838–843, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhuo J, Ohishi M, Mendelsohn FA. Roles of AT1 and AT2 receptors in the hypertensive Ren-2 gene transgenic rat kidney. Hypertension 33: 347–353, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]