Abstract

Atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) elicits natriuresis; however, the relative contributions of proximal and distal nephron segments to the overall ANP-induced natriuresis have remained uncertain. This study was performed to characterize the effects of ANP on distal nephron sodium reabsorption determined after blockade of the two major distal nephron sodium transporters with amiloride (5 μg/g body wt) plus bendroflumethiazide (12 μg/g body wt) in male anesthetized C57/BL6 and natriuretic peptide receptor-A gene (Npr1) targeted four-copy mice. The lower dose of ANP (0.1 ng·g body wt−1·min−1, n = 6) increased distal sodium delivery (DSD, 2.4 ± 0.4 vs. 1.6 ± 0.2 μeq/min, P < 0.05) but did not change fractional reabsorption of DSD compared with control (86.3 ± 2.0 vs. 83.9 ± 3.6%, P > 0.05), thus limiting the magnitude of the natriuresis. In contrast, the higher dose (0.2 ng·g body wt−1·min−1, n = 6) increased DSD (2.8 ± 0.3 μeq/min, P < 0.01) and also decreased fractional reabsorption of DSD (67.4 ± 4.5%, P < 0.01), which markedly augmented the natriuresis. In Npr1 gene-duplicated four-copy mice (n = 6), the lower dose of ANP increased urinary sodium excretion (0.6 ± 0.1 vs. 0.3 ± 0.1 μeq/min, P < 0.05) and decreased fractional reabsorption of DSD compared with control (72.2 ± 3.4%, P < 0.05) at similar mean arterial pressures (91 ± 6 vs. 92 ± 3 mmHg, P > 0.05). These results provide in vivo evidence that ANP-mediated increases in DSD alone exert modest effects on sodium excretion and that inhibition of fractional reabsorption of distal sodium delivery is requisite for the augmented natriuresis in response to the higher dose of ANP or in Npr1 gene-duplicated mice.

Keywords: atrial natriuretic peptide, renal sodium reabsorption, distal nephron segments, amiloride, bendroflumethiazide

the natriuresis elicited by atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) has been attributed to inhibition of sodium reabsorption at both proximal (14, 15, 32, 43) and distal nephron segments, including the collecting duct (1, 3, 12, 31, 37, 39, 46). ANP also causes renal vasodilation and increases glomerular filtration rate (GFR), which are usually not sustained (9, 20, 40). Ader et al. (1) reported that the natriuretic effect of ANP in anesthetized rats resulted from an increase in the filtered load of sodium and from a decrease in reabsorption in the distal nephron segments, whereas proximal tubule sodium reabsorption increased in proportion to the filtered load. However, Seino et al. (33) did not find that ANP modifies the distal tubular function or sodium reabsorption in anesthetized rabbits. In human subjects, ANP caused natriuresis without significant effects on inulin clearance or fractional excretion of lithium (4). Biollaz et al. (5) suggested that ANP-induced natriuresis in human subjects was mostly because of inhibition of sodium reabsorption in the distal nephron segments. In ANP gene-knockout mice, sodium reabsorption is higher in medullary collecting ducts than it is in wild-type mice, resulting in an impaired natriuretic response to saline infusions (16). Thus there is support for the importance of both proximal and distal nephron segments in mediating the natriuretic effect of ANP.

There has been a resurgence in interest regarding the potential roles of natriuretic peptide and their receptors in providing a protective effect counteracting excessive activation of the renin-angiotensin system (27, 48, 51). ANP is clearly important in mediating the natriuretic response to blood volume expansion (29, 35). ANP disruption results in a blunting of the acute pressure-natriuresis mechanism at increased levels of renal arterial pressure (AP; see Refs. 25 and 30). Accordingly, it seemed appropriate to revaluate the effects of different doses of ANP on the possible changes in tubular sodium reabsorption. The present experiments were performed in both wild-type and gene-targeted mice overexpressing natriuretic peptide receptor-A gene (Npr1) to obtain in vivo evidence regarding the nephron segment that is primarily responsible for mediating the natriuretic actions of ANP.

The distal nephron segments are ultimately responsible for the fine regulation of sodium excretion, whereas the proximal tubule is responsible for reabsorbing the bulk of the GFR (18, 44). In distal nephron segments, sodium reabsorption is mainly mediated by amiloride (AM) sensitive-epithelial sodium channels (ENaC) and thiazide-sensitive Na+-Cl− cotransporter (NCC). During treatment with AM plus bendroflumethiazide (BFTZ) to block most of sodium transport in distal nephron segments, sodium excretion can be used as a collective measure of sodium delivery to distal nephron segments (18, 21, 49, 50). Sodium reabsorption in distal nephron segments can thus be determined from the difference between urinary sodium excretion during distal blockade and control urinary sodium excretion. For the present study, we determined the effects of two doses of ANP on sodium reabsorption in distal nephron segments using the method previously described (49, 50). The approach utilized provides a noninvasive collective assessment of distal nephron sodium reabsorption that may be particularly useful in screening studies using gene-targeted mice.

METHODS

Animals.

Studies were performed on 9- to 12-wk-old male C57/BL6 (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) and Npr1 gene-duplicated mice (24, 28, 51) that were maintained on a 12:12-h light-dark schedule (6:00 A.M. to 6:00 P.M.) at 25°C in the vivarium at Tulane University Health Sciences Center. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Tulane University Health Sciences Center.

Experimental protocol.

On the day of experiment, mice were anesthetized with Inactin (thiobutabarbital sodium) injected intraperitoneally at 200 μg/g body wt. Supplemental doses of anesthesia were administrated as required to maintain a stable plane of anesthesia. Once a stable level of anesthesia was obtained, judged by heart rate and lack of toe reflex, mice were placed on a surgical table (37°C) with servo-control of temperature to maintain body temperature at 37°C. A tracheostomy was performed with PE-90 tubing, and mice were allowed to breathe air enriched with O2 by placing the exterior end of the tracheal cannula inside a small plastic chamber into which humidified 95% O2-5% CO2 was continuously passed. The right carotid artery was cannulated with PE-10 tubing connected to PE-50 tubing for continuous measurement of AP and blood sampling. AP was recorded on a Grass polygraph (Grass Instrument, Quincy, MA) through a Statham pressure transducer (model P23 Db; Statham-Gould, Oxnard, CA). The right jugular vein was catheterized with PE-10 tubing connected to PE-50 tubing for fluid infusion. During surgery, an isotonic saline solution containing 6% BSA (Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO) was infused at a rate of 4 μl/min to maintain euvolemia. The bladder was catheterized with PE-90 tubing via a suprapubic incision for urine collections. After completion of surgery, the intravenous infusion solution was changed to isotonic saline containing 1% BSA and 4.5% polyfructosan (Inutest; Laevosan, Linz/Donau, Austria) and was infused at 4 μl/min. After a 60-min equilibration period, urine samples were collected during three 30-min periods. Following the first two control periods (periods 1 and 2), AM (5 μg/g body wt) and BFTZ (12 μg/g body wt) were administered intravenously to block ENaC and NCC. Period 3 was initiated 15 min after administrating AM and BFTZ. The peak urinary sodium excretion during blockade of the two major sodium transporters in distal nephron segments was used as an estimate of sodium delivery to the distal nephron segments (21, 49, 50). When coupled with urinary sodium excretion measured during the control periods, distal nephron sodium reabsorption was determined from the difference between urinary sodium excretion during distal blockade (period 3) and urinary sodium excretion in the absence of blockade of ENaC and NCC (the average of periods 1 and 2). In acute ANP infusion groups, low-dose ANP (0.1 ng·g body wt−1·min−1, n = 6; Sigma Chemical) and high-dose ANP (0.2 ng·g body wt−1·min−1, n = 6), which were dissolved in the infusion solution of inulin, were started 30 min before the first collection period and maintained throughout the experiment. The control group (n = 10) received inulin infusion for the duration of the experiment. To further address the natriuretic mechanisms induced by ANP infusions, low-dose ANP was infused in Npr1 gene-duplicated four-copy mice (n = 6), which have a gene-duplicated homozygous allele (35, 51). Only the lower dose was used because of hypotension caused by higher doses. The body weights in each group of mice were 25.7 ± 0.8 (control), 24.0 ± 0.5 (low-dose ANP), 25.3 ± 0.6 (high-dose ANP), and 26.8 ± 0.9 (Npr1 4-copy) g. Terminal arterial blood samples were collected from the arterial catheter at the end of the experiment for measurements of plasma inulin and sodium concentrations. To avoid the hypotension that results in mice when even small blood samples are taken, blood was collected only one time at the end of the experiment. In a control group of mice, stability of renal function was assessed. AP, GFR, urine flow, and urinary sodium excretion were measured during three clearance periods without addition of the diuretics after period 2. As shown in Table 1, these values remained stable during the three collection periods. In initial experiments, we compared AP and GFR between mice treated with AM + BFTZ (n = 12) and mice not treated with AM + BFTZ (n = 5). There were no significant differences between untreated control mice and diuretic-treated mice in AP (93 ± 2 vs. 90 ± 3 mmHg, P > 0.05) and GFR (0.19 ± 0.02 vs. 0.20 ± 0.04 ml/min, P > 0.05). Importantly, in each mouse, the ANP infusion was started at the onset of the experiment, and, except for the diuretics given after period 2, no other manipulations were made during the collection periods. Also, there were not any significant differences in GFR in control mice before and after treatment with AM + BFTZ (0.22 ± 0.04 vs. 0.21 ± 0.03 ml/min, P > 0.05).

Table 1.

Time control

| AP, mmHg | GFR, ml/min | UF, μl/min | UNaV, μeq/min | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Period 1 | 93±2 | 0.18±0.03 | 3.4±0.8 | 0.18±0.04 |

| Period 2 | 92±2 | 0.20±0.06 | 3.5±0.9 | 0.19±0.06 |

| Period 3 | 91±2 | 0.18±0.04 | 3.7±0.3 | 0.19±0.07 |

Values are means ± SE; n = 5 mice in each group. AP, arterial pressure; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; UF, urine flow; UNaV, urinary sodium excretion.

Urine and plasma inulin measurements.

Urine and plasma inulin concentrations were measured using standard colorimetric techniques as reported previously (35, 49, 50). GFR was calculated as the ratio of urine and plasma inulin concentrations times urine flow. GFR was calculated three times during the three collection periods based on the inulin excretion rates during each period.

Urine and plasma sodium measurements.

Urine output was determined gravimetrically assuming a density of 1 g/ml. Urine and plasma sodium concentrations were measured using flame photometry (Flame Photometer IL 973; Instrumentation Laboratory, Lexington, MA).

Calculations.

UNaVc is the urinary sodium excretion during control periods (the average of periods 1 and 2). UNaVAM+BFTZ (distal sodium delivery) indicates the urinary sodium excretion following administration of AM + BFTZ (period 3). Sodium reabsorption in distal nephron segments (distal sodium reabsorption) was determined from the UNaVAM+BFTZ − UNaVc. Fractional reabsorption of distal sodium delivery was then determined from (UNaVAM+BFTZ − UNa Vc)/UNaVAM+BFTZ.

Statistical analysis.

The statistical analysis was performed by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's multiple-comparison test using the GraphPad PRISM program (GraphPad, San Diego, CA). The results are presented as means ± SE. Significance was set at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Arterial pressure.

As shown in Fig. 1, there were no significant differences in AP among the control (92 ± 3 mmHg) and ANP-infused groups before administration of AM + BFTZ (92 ± 6 mmHg, P > 0.05; 97 ± 3 mmHg, P > 0.05). There were no significant differences in AP among the control (91 ± 3 mmHg) and ANP-infused groups during administration of AM + BFTZ (93 ± 6 mmHg, P > 0.05; 97 ± 4 mmHg, P > 0.05). In addition, AP in Npr1 gene-duplicated four-copy mice under anesthesia before (91 ± 6 mmHg, P > 0.05) and after (88 ± 6 mmHg, P > 0.05) administration of AM + BFTZ appeared to trend slightly lower, but the differences were not statistically significant. AP remained stable during the three clearance periods.

Fig. 1.

Mean arterial pressure in anesthetized mice during control conditions and during acute atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) infusions. Values are given as means ± SE.

GFR.

As shown in Fig. 2, GFR values during low-dose ANP (0.22 ± 0.01 ml/min, P > 0.05) or high-dose ANP (0.26 ± 0.05 ml/min, P > 0.05) were not significantly different from each other or from GFR in control mice (0.22 ± 0.04 ml/min). Although slightly lower, GFR was not significantly different in Npr1 gene-duplicated four-copy mice compared with control (0.16 ± 0.02 ml/min, P > 0.05).

Fig. 2.

Effects of acute ANP infusions on glomerular filtration rate (GFR). Values, which represent the average of periods 1 and 2, are given as means ± SE. P < 0.05, compared with control (*) and compared with low-dose ANP (†).

Urine flow and urinary sodium excretion.

As shown in Table 2, urine flow values before and during administration of AM + BFTZ during low-dose ANP (1.9 ± 0.4 μl/min, P > 0.05; 1.8 ± 0.3 μl/min, P > 0.05; 6.9 ± 0.9 μl/min, P > 0.05) or the higher ANP dose (3.5 ± 0.5 μl/min, P > 0.05; 3.4 ± 0.4 μl/min, P > 0.05; 9.2 ± 0.8 μl/min, P > 0.05) were not significantly different from urine flow in control mice (2.4 ± 0.3 μl/min; 2.6 ± 0.3 μl/min; 6.3 ± 0.7 μl/min). Compared with control mice, urine flows were not significantly different in Npr1 gene-duplicated four-copy mice before and during administration of AM + BFTZ (3.9 ± 0.9 μl/min, P > 0.05; 3.3 ± 0.6 μl/min, P > 0.05; 6.5 ± 0.9 μl/min, P > 0.05). Urinary sodium excretion rates in the low-dose ANP group before administration of AM + BFTZ (0.38 ± 0.13 μeq/min, P > 0.05; 0.28 ± 0.06 μeq/min, P > 0.05) were not significantly different from urinary sodium excretion rates in control mice (0.31 ± 0.07 and 0.25 ± 0.05 μeq/min); however, urinary sodium excretion rates were significantly higher in the group infused with the higher-dose ANP before administration of AM + BFTZ (0.82 ± 0.14 μeq/min, P < 0.01; 0.95 ± 0.16 μeq/min, P < 0.001). In Npr1 gene-duplicated four-copy mice, urinary sodium excretion rate was significantly higher before administration of AM + BFTZ (0.65 ± 0.12 μeq/min, P < 0.05; 0.57 ± 0.09 μeq/min, P < 0.05). In response to AM + BFTZ, sodium excretion increased significantly in all four groups.

Table 2.

UF and UNaV

|

Period 1 |

Period 2 |

Period 3 (A + B) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UF, μl/min | UNaV, μeq/min | UF, μl/min | UNaV, μeq/min | UF, μl/min | UNaV, μeq/min | |

| Control | 2.4±0.3 | 0.31±0.07 | 2.6±0.3 | 0.25±0.05 | 6.3±0.7 | 1.48±0.19 |

| Low-dose ANP | 1.9±0.4 | 0.38±0.13 | 1.8±0.3 | 0.28±0.06 | 6.9±0.9 | 2.26±0.44† |

| High-dose ANP | 3.5±0.5 | 0.82±0.14* | 3.4±0.4‡ | 0.95±0.16§ | 9.2±0.8 | 2.78±0.25* |

| Npr1 4-copy | 3.9±0.9 | 0.65±0.12† | 3.3±0.6 | 0.57±0.09† | 6.5±0.9 | 1.92±0.15 |

Values are means ± SE. ANP, atrial natriuretic peptide; Npr1, gene coding for natriuretic peptide receptor-A. Shown are data for UF and UNaV in control, ANP-infused mice, and Npr1 gene-duplicated 4-copy mice before and during administration of amiloride plus bendroflumethiazide (A + B) during period 3.

Compared with control, P < 0.05,

P < 0.01, and

P < 0.001.

Compared with low-dose ANP, P < 0.05.

Distal sodium delivery and sodium reabsorption in distal nephron segments.

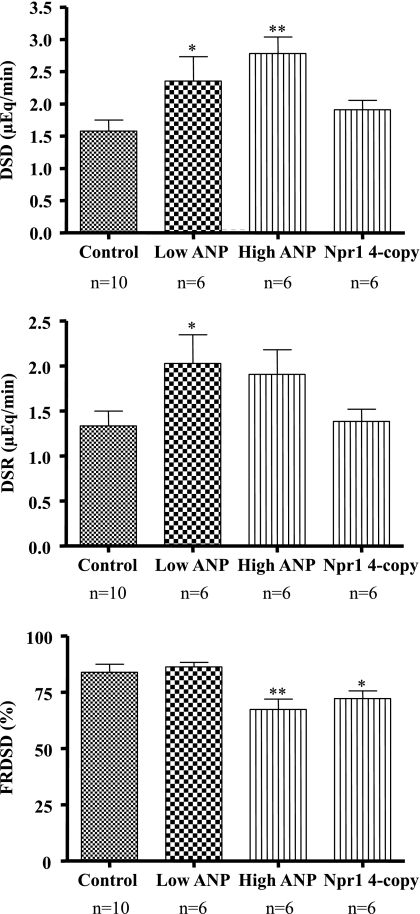

As shown in Fig. 3, estimated distal sodium delivery values were higher in both groups infused with ANP compared with control [2.4 ± 0.4 (P < 0.05) and 2.8 ± 0.3 (P < 0.01) vs. 1.6 ± 0.2 μeq/min], suggesting similar degrees of inhibition in the segments proximal to the distal nephron. However, distal nephron sodium reabsorption rate was significantly higher in the low-dose ANP group (2.0 ± 0.3 μeq/min, P < 0.05), but not in the high-dose ANP group (1.9 ± 0.3 μeq/min, P > 0.05) compared with control (1.3 ± 0.2 μeq/min). In Npr1 gene-duplicated four-copy mice, distal sodium delivery (1.9 ± 0.1 μeq/min, P > 0.05) and distal nephron sodium reabsorption rate were not significantly higher (1.4 ± 0.1 μeq/min, P > 0.05). Importantly, low-dose ANP did not change fractional reabsorption of distal sodium delivery (86.3 ± 2.0%, P > 0.05) compared with control (83.9 ± 3.6%). However, fractional reabsorption of distal sodium delivery was significantly lower in the group infused with the higher-dose ANP (67.4 ± 4.5%, P < 0.01) and in Npr1 gene-duplicated four-copy mice (72.2 ± 3.4%, P < 0.05).

Fig. 3.

Effects of acute ANP infusions on distal sodium delivery (DSD), distal sodium reabsorption (DSR), and fractional reabsorption of DSD (FRDSD) in control and ANP-infused mice. Values are means ± SE. P < 0.05 compared with control, *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

Although the natriuretic effects of ANP are well established, the responses have been attributed to inhibition of sodium reabsorption at proximal nephron segments (14, 15, 32, 43) and/or decreases in the collecting duct segments (1, 3, 12, 31, 37, 39, 46). However, in vivo evidence regarding the segment predominantly responsible for the actual natriuretic response has remained uncertain. The present study provides in vivo evidence that inhibition of fractional reabsorption of distal sodium delivery is requisite in mediating substantive ANP-induced natriuresis.

Previous studies using the lithium clearance method have shown that ANP inhibits proximal sodium reabsorption and limits the increase in proximal reabsorption associated with increases in filtered load in anaesthetized rats (6, 14). At physiological concentrations, ANP decreases proximal reabsorption, in part, by counteracting angiotensin-stimulated sodium reabsorption (15). ANP can produce a natriuresis in the absence of changes in GFR and elicits increases in absolute and fractional sodium deliveries to the end-descending limb in young rats (32). In contrast, Capasso et al. (8) reported that the enhancement of renal sodium excretion induced by ANP is not related to a direct inhibition of sodium transport in the proximal tubule. Because the inner medullary collecting duct (IMCD) is considered to be the final arbiter of renal sodium excretion (44), ANP-induced inhibition of luminal sodium entry in the IMCD appears to contribute to the marked natriuretic effect of this hormone in vivo (46). Several studies have shown similar results that ANP inhibits sodium reabsorption at distal tubule (12) and collecting duct segments (12, 39), but the quantitative importance of this effect has not been established under in vivo conditions.

In the present study, acute ANP infusions at doses of 0.1 or 0.2 ng·g body wt−1·min−1 did not significantly influence AP. Higher doses of ANP were not used to avoid the confounding effects of decreases in AP that occur with higher doses. At these doses, we did not observe significant differences in GFR between control and ANP-infused groups. We also did not find any effects of AM and BFTZ on GFR. Thus ANP inhibited net sodium reabsorption without increasing whole kidney GFR (23). Paul et al. (30) reported that ANP-(8–33) infusion (∼0.15 μg·kg−1·min−1) led to natriuresis without affecting systemic blood pressure or renal hemodynamics in dogs. Furthermore, ANP infusions increased GFR at AP around 80 mmHg (30). ANP infusions also led to the dilation of afferent arterioles (40), which may be the major mechanism for increased GFR. Caron and Kramp (9) found that GFR was transiently elevated in rats after an intravenous injection of 1 μg ANP. Wang et al. (42) reported that GFR did not change during acute ANP infusions (0.5 ng·g body wt−1·min−1) in rats, but there was a significant decrease in systemic blood pressure. Likewise, rat pro-ANP-(1–30) infusions (30 ng/min after a bolus of 10 ng) for 240 min did not change GFR in rats (11). Thus most of the data suggest that effects of ANP on GFR may be related to the dose and administration method, but that the natriuretic effects are not dependent on increases in GFR.

Although both ANP doses used in the present study increased distal sodium delivery, we found that urinary sodium excretion was significantly augmented only in the group given the higher dose of ANP. In Npr1 gene-duplicated four-copy mice, urinary sodium excretion was also significantly higher with low-dose ANP infusions, suggesting that the overexpression of Npr1 augments natriuresis induced by ANP infusions. Paul et al. (29) reported that rat ANP-(103–126) infusions (0.2 μg·kg−1·min−1) led to natriuresis in rats, and a positive relationship was observed between urinary sodium excretion and plasma ANP concentration. However, it was reported that acute ANP infusions (0.5 ng·g body wt−1·min−1) induced a rapid increase in urine flow that peaked 10 min after the initiation of ANP infusion and returned to the baseline level by 25 min after the initiation of ANP infusion (42). Furthermore, acute ANP infusions significantly increased urinary sodium excretion and peaked 15 min after the onset of ANP infusion and declined gradually after the peak but remained elevated compared with control (42). Of note, several studies have shown that diuresis and natriuresis induced by ANP are transient when ANP is given as continuous infusions or as repeated bolus injections in humans and animals because resistance to the diuretic and natriuretic actions of ANP develops after relatively brief periods of ANP infusion (7, 13, 41). This phenomenon may be related to the mechanism that the subcellular localization of ENaC increases after 90 min of ANP infusion (42). It is also known that ANP binding to Npr1 increases cellular cGMP production, which activates cGMP-dependent protein kinases, cGMP-dependent phosphodiesterases, and cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channels as effector molecules (26, 27). The activation of these three effector molecules elicits vasodilation and inhibits sodium reabsorption (27). Increased intracellular cGMP may regulate sodium, and perhaps calcium, uptake in nephron segments proximal to the IMCD (22). Luminal ANP also decreases chloride reabsorption in mouse cortical thick ascending limb and medullary thick ascending limb (2). Inoue et al. (17) reported that ANP causes diuresis and natriuresis, at least in part by inhibiting the vasopressin 2 receptor-mediated action of vasopressin in the collecting ducts. Inhibition of basolateral Na+-K+-ATPase, probably via the stimulation of PGE2 synthesis, may also be involved in the natriuresis induced by ANP (45).

In the present study, sodium reabsorption in distal nephron segments was effectively inhibited during administration of AM + BFTZ although we cannot be certain that we elicited complete inhibition of the distal sodium transporters. The fractional urinary sodium excretion rates varied from <1% during control conditions to >4% during dual distal nephron blockade with AM + BFTZ, suggesting effective blockade of distal nephron transport function. This value is consistent with current concepts regarding the sodium load to distal nephron segments. In our original experiments, we tested various doses and determined the maximal dose that would inhibit distal sodium reabsorption without also increasing the distal sodium delivery to values suggestive of proximal inhibition. We also considered the possibility that our dose of AM might cause inhibition of Na+/H+ exchanger (NHE) 3. However, the dose of AM in this study would be expected to lead to plasma concentrations much lower than those shown to inhibit NHE3. Furthermore, if the dose of AM used also inhibited the NHE isoform, NHE3, in proximal tubules, we would have expected much greater increases in urinary sodium excretion. In other studies using AM, AM did not affect Li+ clearance in rats (36) and slightly increased fractional Li+ excretion in dogs (34). However, the effect of AM to increase Li+ excretion may be because of inhibition of distal Li+ uptake in rats (19). These data suggest that the dose of AM used does not affect proximal sodium reabsorption. Furthermore, BFTZ did not increase Li+ clearance in rats (38). From these data, it can be concluded that inhibition of sodium reabsorption in response to AM + BFTZ occurs primarily at distal nephron segments. Therefore, sodium excretion during dual blockade provides a collective measure of distal sodium delivery to distal nephron segments (21, 49, 50). We found that the low-dose ANP increased distal sodium delivery, indicating inhibition at earlier nephron segments but also increased distal nephron sodium reabsorption in response to the increased load compared with control. In contrast, high-dose ANP increased distal sodium delivery and blunted the increase in distal nephron sodium reabsorption. Thus the low-dose ANP did not affect fractional reabsorption of distal sodium delivery, which limited the magnitude of the natriuresis, whereas the high-dose ANP decreased fractional reabsorption of distal sodium delivery and led to the augmented natriuresis in this group. These results help explain the lack of sustained natriuresis in response to low-dose ANP and the differences between the effects of low-dose and high-dose ANP. In Npr1 gene-duplicated four-copy mice, the low-dose ANP decreased fractional reabsorption of distal sodium delivery, suggesting that the augmented natriuresis induced by ANP infusions is mediated by overexpression of Npr1 via inhibition of distal sodium reabsorption. Importantly, while we agree that previous studies have shown actions of ANP on multiple nephron segments, the present results provide the hierarchy of these actions and provide in vivo evidence to support the critical role of reduced fractional sodium reabsorption in distal nephron segments in the mediation of ANP-induced increases in sodium excretion.

The present study describes an in vivo approach to obtain a collective and quantitative index of distal nephron sodium reabsorption that allows overall assessment of distal nephron transport in intact kidneys. Although we are providing only an estimated index of distal nephron sodium reabsorption, it is also a quantitative index of the collective distal sodium delivery and distal sodium reabsorption of the total nephron population, which is not possible from micropuncture or isolated perfused tubule experiments. By minimizing the extent of surgical manipulations, more robust values for renal function can be obtained. This technique is particularly applicable to studies in transgenic mice that may have alterations in sodium transport in distal nephron segments that need to be quantified (47). This technique will be helpful to elucidate the role of increased distal nephron sodium reabsorption in the pathophysiology of hypertension. Furthermore, this approach may be useful in translation studies by providing a technique to assess distal transport function in patients with disorders of sodium excretion. Such data would thus provide the rationale for considering the use of these diuretics that primarily inhibit distal nephron sodium reabsorption such as those used in the present study.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants HL-18426, HL-62147, and P20RR-0117659 from the Institutional Development Award Program of NCRR.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest are declared by the authors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Edward Au and Subhankar Das for providing Npr1 gene-duplicated four-copy mice.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ader JL, Tran-Van T, Praddaude F. Nephron sites of the natriuretic effect of intrarenal infusion of atrial natriuretic peptide in the rat. Am J Hypertens 3: 870–872, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bailly C. Effect of luminal atrial natriuretic peptide on chloride reabsorption in mouse cortical thick ascending limb: inhibition by endothelin. J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 1791–1797, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barreto-Chaves ML, Mello-Aires M. Effect of luminal angiotensin II and ANP on early and late cortical distal tubule HCO3− reabsorption. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 271: F977–F984, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bijlsma JA, Koomans HA, Dorhout Mees EJ. Effects of nitrendipine on sodium balance during changes in sodium intake and low-dosage ANP. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 17: 192–198, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biollaz J, Bidiville J, Diézi J, Waeber B, Nussberger J, Brunner-Ferber F, Gomez HJ, Brunner HR. Site of the action of a synthetic atrial natriuretic peptide evaluated in humans. Kidney Int 32: 537–546, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burnett JC, Jr, Opgenorth TJ, Granger JP. The renal action of atrial natriuretic peptide during control of glomerular filtration. Kidney Int 30: 16–19, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campbell HT, Lightfoot BO, Sklar AH. Four-hour atrial natriuretic peptide infusion in conscious rats: effects on urinary volume, sodium, and cyclic GMP. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 189: 317–324 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Capasso G, Rosati C, Giórdano DR, De Santo NG. Atrial natriuretic peptide has no direct effect on proximal tubule sodium and water reabsorption. Pflügers Arch 415: 336–341, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caron N, Kramp R. Measurement of changes in glomerular filtration rate induced by atrial natriuretic peptide in the rat kidney. Exp Physiol 84: 689–696, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davis CL, Briggs JP. Effects of atrial natriuretic peptide on renal medullary solute gradients. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 253: F679–F684, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dietz JR, Scott DY, Landon CS, Nazian SJ. Evidence supporting a physiological role for proANP-(1-30) in the regulation of renal excretion. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 280: R1510–R1517, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fried TA, Osgood RW, Stein JH. Tubular site(s) of action of atrial natriuretic peptide in the rat. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 255: F313–F316, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garcia R, Cantin M, GEnest J, Gutkowska J, Thibault G. Body fluids and plasma atrial peptide after its chronic infusion in hypertensive rats. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 185: 352–358, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harris PJ, Skinner SL, Zhuo J. The effects of atrial natriuretic peptide and glucagon on proximal glomerulo-tubular balance in anaesthetized rats. J Physiol 402: 29–42, 1988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harris PJ, Thomas D, Morgan TO. Atrial natriuretic peptide inhibits angiotensin-stimulated proximal tubular sodium and water reabsorption. Nature 326: 697–698, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Honrath U, Chong CK, Melo LG, Sonnenberg H. Effect of saline infusion on kidney and collecting duct function in atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) gene “knockout” mice. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 77: 454–457, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Inoue T, Nonoguchi H, Tomita K. Physiological effects of vasopressin and atrial natriuretic peptide in the collecting duct. Cardiovasc Res 51: 470–480, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khan O, Riazi S, Hu X, Song J, Wade JB, Ecelbarger CA. Regulation of the renal thiazide-sensitive Na-Cl cotransporter, blood pressure, and natriuresis in obese Zucker rats treated with rosiglitazone. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 289: F442–F450, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kirchner KA. Effect of diuretic and antidiuretic agents on lithium clearance as a marker for proximal delivery. Kidney Int Suppl 28: S22–S25, 1990 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lanese DM, Yuan BH, Falk SA, Conger JD. The effects of atriopeptin III on isolated rat afferent and efferent arterioles. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 261: F1102–F1109, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Majid DS, Navar LG. Blockade of distal nephron sodium transport attenuates pressure natriuresis in dogs. Hypertension 23: 1040–1045, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCoy DE, Guggino SE, Stanton BA. The renal cGMP-gated cation channel: its molecular structure and physiological role. Kidney Int 48: 1125–1133, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McGowan JA, Pitts TO, Rose ME, Puschett JB. The effects of atrial natriuretic peptide on whole-kidney and proximal straight tubular function in the rabbit. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 185: 62–68, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oliver PM, John SW, Purdy KE, Kim R, Maeda N, Goy MF, Smithies O. Natriuretic peptide receptor 1 expression influences blood pressures of mice in a dose-dependent manner. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 2547–2551, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O'Tierney PF, Komolova M, Tse MY, Adams MA, Pang SC. Altered regulation of renal interstitial hydrostatic pressure and the renal renin-angiotensin system in the absence of atrial natriuretic peptide. J Hypertens 26: 303–311, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pandey KN. Biology of natriuretic peptides and their receptors. Peptides 26: 901–932, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pandey KN. Emerging roles of natriuretic peptides and their receptors in pathophysiology of hypertension and cardiovascular regulation. J Am Soc Hypertens 2: 210–226, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pandey KN, Oliver PM, Maeda N, Smithies O. Hypertension associated with decreased testosterone levels in natriuretic peptide receptor-A gene-knockout and gene-duplicated mutant mouse models. Endocrinology 140: 5112–5119, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paul RV, Ferguson T, Navar LG. ANF secretion and renal responses to volume expansion with equilibrated blood. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 255: F936–F943, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Paul RV, Kirk KA, Navar LG. Renal autoregulation and pressure natriuresis during ANF-induced diuresis. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 253: F424–F431, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rouch AJ, Chen L, Troutman SL, Schafer JA. Na+ transport in isolated rat CCD: effects of bradykinin, ANP, clonidine, and hydrochlorothiazide. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 260: F86–F95, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roy DR. Effect of synthetic ANP on renal and loop of Henle functions in the young rat. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 251: F220–F225, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seino M, Abe K, Nushiro N, Omata K, Yoshinaga K. Interaction of atrial natriuretic peptide and amiloride on renal hemodynamics through renal kallikrein and kinins in anesthetized rabbits. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 13, Suppl 6: S39–S42, 1989 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shalmi M, Bech Laursen J, Plange-Rhule J, Christensen S, Atherton J, Bie P. Lithium clearance in dogs: effects of water loading, amiloride and lithium dosage. Clin Sci (Lond) 82: 635–640, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shi SJ, Vellaichamy E, Chin SY, Smithies O, Navar LG, Pandey KN. Natriuretic peptide receptor A mediates renal sodium excretory responses to blood volume expansion. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 285: F694–F702, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shirley DG, Walter SJ, Sampson B. A micropuncture study of renal lithium reabsorption: effects of amiloride and furosemide. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 263: F1128–F1133, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sonnenberg H, Honrath U, Chong CK, Wilson DR. Atrial natriuretic factor inhibits sodium transport in medullary collecting duct. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 250: F963–F966, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spannow J, Thomsen K, Petersen JS, Haugan K, Christensen S. Influence of renal nerves and sodium balance on the acute antidiuretic effect of bendroflumethiazide in rats with diabetes insipidus. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 282: 1155–1162, 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van de Stolpe A, Jamison RL. Micropuncture study of the effect of ANP on the papillary collecting duct in the rat. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 254: F477–F483, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Veldkamp PJ, Carmines PK, Inscho EW, Navar LG. Direct evaluation of the microvascular actions of ANP in juxtamedullary nephrons. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 254: F440–F444, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Waldhausl W, Vierhapper H, Nowotny P. Prolonged administration of human atrial natriuretic peptide in health men: evanescent effects on diuresis and natriuresis. J Clin Endocrinal Metab 62: 956–959, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang W, Li C, Nejsum LN, Li H, Kim SW, Kwon TH, Jonassen TE, Knepper MA, Thomsen K, Frokiaer J, Nielsen S. Biphasic effects of ANP infusion in conscious, euvolumic rats: roles of AQP2 and ENaC trafficking. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 290: F530–F541, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Winaver J, Burnett JC, Tyce GM, Dousa TP. ANP inhibits Na+-H+ antiport in proximal tubular brush border membrane: role of dopamine. Kidney Int 38: 1133–1140, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zeidel ML. Hormonal regulation of inner medullary collecting duct sodium transport. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 265: F159–F173, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zeidel ML. Regulation of collecting duct Na+ reabsorption by ANP 31–67. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 22: 121–124, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zeidel ML, Kikeri D, Silva P, Burrowes M, Brenner BM. Atrial natriuretic peptides inhibit conductive sodium uptake by rabbit inner medullary collecting duct cells. J Clin Invest 82: 1067–1074, 1988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang J, Lee MY, Cavalli M, Chen L, Berra-Romani R, Balke CW, Bianchi G, Ferrari P, Hamlyn JM, Iwamoto T, Lingrel JB, Matteson DR, Wier WG, Blaustein MP. Sodium pump alpha2 subunits control myogenic tone and blood pressure in mice. J Physiol 569: 243–256, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang Q, Saito Y, Naya N, Imagawa K, Somekawa S, Kawata H, Takeda Y, Uemura S, Kishimoto I, Nakao K. The specific mineralocorticoid receptor blocker eplerenone attenuates left ventricular remodeling in mice lacking the gene encoding guanylyl cyclase-A. Hypertens Res 31: 1251–1256, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhao D, Dale Seth M, Navar LG. Enhanced distal nephron sodium reabsorption in chronic angiotensin II-infused mice. Hypertension 54: 120–126, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhao D, Navar LG. Acute angiotensin II infusions elicit pressure natriuresis in mice and reduce distal fractional sodium reabsorption. Hypertension 52: 137–142, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhao D, Vellaichamy E, Somanna NK, Pandey KN. Guanylyl cyclase/natriuretic peptide receptor-A gene disruption causes increased adrenal angiotensin II and aldosterone levels. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 293: F121–F127, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]