Abstract

This study presents a multicellular computational model of a rat mesenteric arteriole to investigate the signal transduction mechanisms involved in the generation of conducted vasoreactivity. The model comprises detailed descriptions of endothelial (ECs) and smooth muscle (SM) cells (SMCs), coupled by nonselective gap junctions. With strong myoendothelial coupling, local agonist stimulation of the EC or SM layer causes local changes in membrane potential (Vm) that are conducted electrotonically, primarily through the endothelium. When myoendothelial coupling is weak, signals initiated in the SM conduct poorly, but the sensitivity of the SMCs to current injection and agonist stimulation increases. Thus physiological transmembrane currents can induce different levels of local Vm change, depending on cell's gap junction connectivity. The physiological relevance of current and voltage clamp stimulations in intact vessels is discussed. Focal agonist stimulation of the endothelium reduces cytosolic calcium (intracellular Ca2+ concentration) in the prestimulated SM layer. This SMC Ca2+ reduction is attributed to a spread of EC hyperpolarization via gap junctions. Inositol (1,4,5)-trisphosphate, but not Ca2+, diffusion through homocellular gap junctions can increase intracellular Ca2+ concentration in neighboring ECs. The small endothelial Ca2+ spread can amplify the total current generated at the local site by the ECs and through the nitric oxide pathway, by the SMCs, and thus reduces the number of stimulated cells required to induce distant responses. The distance of the electrotonic and Ca2+ spread depends on the magnitude of SM prestimulation and the number of SM layers. Model results are consistent with experimental data for vasoreactivity in rat mesenteric resistance arteries.

Keywords: intercellular communication, membrane potential, calcium dynamics

focal application of certain vasoactive agents to microvessels may cause significant vasomotor responses, both locally and at relatively distant sites. The distant responses are mediated by intrinsic signal transduction mechanisms within the vascular wall, independent of the diffusion of the stimulating agent, hemodynamic effects, or innervations. These conducted responses have been reported in different vascular beds and species (12, 14, 20, 33, 41) and may play a role in both the rapid and long-term coordination of microvascular function. Vasodilatation initiated locally by increased metabolic demand may be conducted upstream to feed arteries to allow adequate increase in blood flow (42, 43); conducted vasoconstriction may be important in the tubuloglomerular feedback mechanism of renal autoregulation (20); and theoretical simulations suggest that axial communication in the vasculature is required to suppress the generation of large proximal shunts during long-term structural adaptation of microvascular networks (38).

The underlying mechanisms of spreading responses remain poorly understood, but electrotonic transmission of membrane potential changes (ΔVm) and calcium (Ca2+) waves through the endothelium seem to play the major role (46, 48). In some vessels, including in rat mesenteric resistance arteries (RMA), the signal is attenuated away from the stimulus site, and the vasoreactivity observed at a distant site is attributed to Ca2+-independent passive electronic diffusion through gap junctions (20, 47). In other vascular beds, the conducted signal can spread over significant distances with minimal attenuation, and thus facilitating/regenerative mechanisms should be involved (24). A number of hypotheses have been proposed to account for the facilitation of the transmitted signal. One suggestion is that membrane hyperpolarization is enhanced by inwardly rectifying potassium (Kir) channels and/or the sodium-potassium (NaK) pump (8). Alternatively, a wave of nitric oxide (NO) release along the arteriolar endothelium, triggered by a spread of Ca2+, could induce spreading dilatation (4, 10). Remote Ca2+ waves have been reported in hamster feed arteries (10, 50). A regenerative mechanism based on the activation of endothelial voltage-dependent sodium and calcium channels has also been suggested (16).

A number of theoretical studies have been performed to investigate spreading responses. Hirst and Neild (26) modeled a vessel segment as a continuous wire with uniform axial resistance and applied traditional cable theory to determine its electrical properties. Crane et al. (6) used a cable model to simulate the spread of ΔVm in microvascular trees. The results of these simulations suggest that a thick smooth muscle layer could favor electrical conduction, but passive conduction was insufficient to explain the experimental recordings. Haug and Segal (23) predicted with a similar passive cable model that the inhibition of conducted vasodilation by α1- and α2-adrenoceptors can be explained by decreased smooth muscle cell (SMC) membrane resistance or increased myoendothelial resistance. Diep et al. (9) developed a detailed computational model of skeletal muscle resistance artery with discrete SMCs and endothelial cells (ECs). Each cell was treated as a capacitor coupled in parallel with a nonlinear resistor representing ionic conductance. Intercellular gap junctions were represented by ohmic resistances. According to the simulations, the vessel wall was not a syncytium, and electrical stimuli did not spread uniformly. The cells' orientation and coupling resistances were the critical factors in determining the differential electrical communication within and between the endothelium and the smooth muscle.

Previous theoretical studies (6, 9, 23, 26) have focused mostly on the electrical behavior of the vessel and have provided insights into the major aspects of spreading responses. To assist further in the elucidation of mechanisms and parameters of the phenomenon, we developed a more comprehensive computational model of a vessel segment that integrates subcellular components and mechanisms with intercellular signaling between neighboring cells in the vascular wall. Unlike earlier models, it incorporates detailed descriptions of Ca2+ dynamics and plasma membrane electrophysiology in vascular endothelial and SMCs. The discrete cells are coupled by the NO pathway and by homocellular and heterocellular gap junctions permeable to Ca2+, K+, Na+, and Cl− ions, and inositol (1,4,5)-trisphosphate (IP3). The present study focuses on the behavior of rat mesenteric vessels, and it does not account for mechanisms observed in other vessel types. It forms, however, a theoretical framework for developing similar models in other vessel types. The model predicts Vm and Ca2+ responses along the vessel segment under various scenarios of agonist stimulations. It investigates the mechanisms that can enhance or attenuate the transmitted signal in conducted vasoreactivity, the contribution of the intercellular diffusion of second messengers in the phenomenon, and the currents generated by membrane channels. We also examine responses to external current injections and discuss the physiological relevance of experimental protocols of electrical stimulation.

METHODS

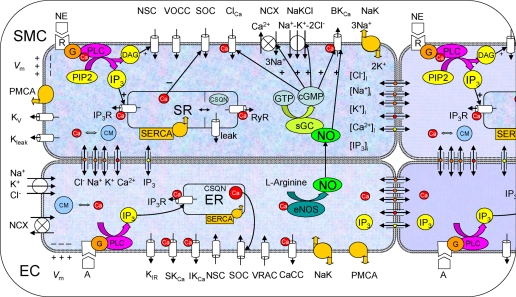

Our laboratory has previously developed detailed mathematical models of plasma membrane electrophysiology and Ca2+ dynamics in isolated EC (44) and SMC (28). Schematics of these models are depicted in Fig. 1. Both cellular models are based primarily on data from RMA. Only the salient features of these models are presented here.

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram of the endothelial cell (EC) and smooth muscle cell (SMC) models. Cells are coupled by nitric oxide (NO) and myoendothelial gap junctions permeable to Ca2+, Na+, K+, and Cl− ions, and inositol (1,4,5)-trisphosphate (IP3). Kir, inward rectifier K+ channel; VRAC, volume-regulated anion channel; SKCa, IKCa, and BKCa: small-, intermediate-, and large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels, respectively; SOC, store-operated channel; NSC, nonselective cation channel; CaCC and ClCa, Ca2+-activated chloride channel; NaK, Na+-K+-ATPase; PMCA, plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase; NCX, Na+/Ca2+ exchanger; NaKCl, Na+-K+-Cl− cotransport; Kv, voltage-dependent K+ channel; Kleak, unspecified K+ leak current; VOCC, voltage-operated Ca2+ channels; SR/ER, sarco/endoplasmic reticulum; IP3R, IP3 receptor; RyR, ryanodine receptor; SERCA, SR/ER Ca2+-ATPase; CSQN, calsequestrin; CM, calmodulin; R, receptor; G, G protein; DAG, diacylglycerol; PLC, phospholipase C; sGC, soluble guanylate cyclase; cGMP, cyclic guanosine monophosphate; Vm, membrane potential; NE, norepinephrine; PIP2, phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate; eNOS, endothelial NO synthase; [Cl−]i, [Na+]i, [K+]i, [Ca2+]i, and [IP3]i: intracellular concentrations.

EC Model

The plasma membrane of the EC includes all of the major channels identified in RMA ECs. Mathematical formulations describe ionic fluxes through the Kir channel, the volume-regulated anion channel, the small- (SKCa) and the intermediate-conductance Ca2+-activated potassium channels (IKCa), the store-operated Ca2+ channel, the nonselective cation channel (NSC), the Ca2+-activated chloride channel, the NaK pump, the plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase pump, the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (NCX), and the Na+-K+-Cl− cotransport (NaKCl). The fluid compartment contains a Ca2+ store that represents the endoplasmic reticulum. Formulations account for Ca2+ release via an IP3 receptor (IP3R)-dependent channel and for Ca2+ sequestration through the sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase pump. Differential equations account for the balance of free and buffered Ca2+ in the store and the cytosol. A novel feature of this model is that it also accounts for the balance of the other major ionic species (Na+, K+, Cl−) and the second-messenger IP3 in the cytosol. Acetylcholine (ACh) stimulation is simulated by IP3 generation. Thus simulation results can also refer to other Ca2+ elevating agonist that act through the IP3 pathway.

The model can capture a number of established features of EC physiology. It exhibits normal whole cell resistivity and physiological resting ionic concentrations. It can also reproduce Ca2+ and Vm responses under a variety of conditions that include blockage of channels, and agonist or extracellular K+ challenges.

SMC Model

In RMA SMCs, the following membrane components have been identified and are considered to play the most significant role in the regulation of Vm and ionic homeostasis: the large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel (BKCa), the voltage-dependent K+ channel, the Ca2+-activated chloride channel, the NSC channel, the store-operated Ca2+ channel, the L-type voltage-operated Ca2+ channel, the NaK and plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase pump, the NaKCl, and the NCX. We have also included an unspecified K+ leak current to account for other K+-permeable channels, such as the ATP-sensitive K+ channel. In the same way as for the EC model, we account for the balance of Ca2+, Na+, K+, Cl−, and IP3 in the cytosol, as well as for the stored Ca2+. The sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) contains a sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase pump, and IP3R, and ryanodine receptor-dependent Ca2+ channels. Proteins such as calsequestrin in the SR and calmodulin in the cytosol regulate the concentration of free Ca2+ through buffering. A leak current (leak) is also included to prevent store overload. A detailed kinetic mechanism describes the signal transduction pathway for the formation of IP3 and diacylglycerol following the binding of norepinephrine (NE) to α1-adrenoceptor (receptor). Formation of IP3 leads to the release of stored Ca+2, whereas diacylglycerol provides sustained membrane depolarization through its action on NSC. The model also simulates the effect of the vasodilator, NO. Kinetic equations describe the activation of soluble guanylate cyclase by NO and the formation of cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP). In our model, NO affects BKCa, Ca2+-activated chloride channel, NCX, and NaKCl in a concentration-dependent fashion. The model exhibits physiological whole cell conductance and intracellular ionic concentrations. It also captures documented Ca2+ and Vm responses under various conditions that include NE, NO, and extracellular K+ challenges, or application of channel blockers.

Multicellular Vessel Model

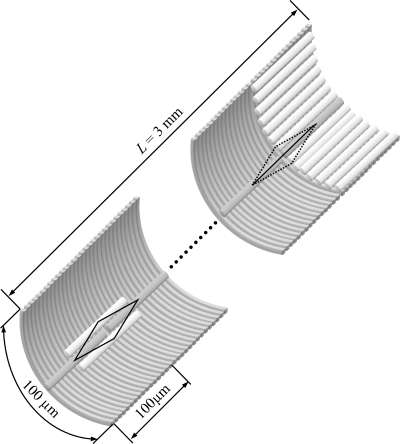

A 3-mm arteriolar segment was constructed through the appropriate arrangement of ECs and SMCs (Fig. 2), similar to the study by Diep et al. (9). We assume a single layer of SMCs is surrounding the ECs. The effect of multiple layers of SMCs on conducted responses is examined in the supplemental data. (The online version of this article contains supplemental data.) The SMCs are aligned perpendicular to the ECs and the vessel axis. The vessel model was reduced to two dimensions (axial and radial) on the assumption that concentration and potential gradients in the circumferential direction are negligible (6). These gradients should be minimal during circumferentially uniform stimulations, but are small even during local stimulation with an intracellular microelectrode (26).

Fig. 2.

Arrangement of ECs and SMCs in the vessel model. Fifteen SMCs overlap each EC, and fifteen ECs overlap each SMC. A serial arrangement of ECs with regular end-to-end couplings is assumed (shown on the right side of the vessel) as equivalent to the overlapping arrangement (shown on the left side). Circumferential symmetry allows us to consider only one SMC and one EC at each discrete position along the vessel. The whole vessel segment is 3 mm long (L), spanning 30 ECs and 450 SMCs in the axial direction.

In this study, we assume that an EC spans 15 SMCs and vice versa. This results in an EC-to-SMC population ratio in the vascular wall of 1:1 and assumes a SMC width equal to 1/15 of the EC length. Representative cell dimensions and population ratios of ECs and SMCs from various tissues are summarized in Supplemental Table S1. The exact cell dimensions can vary significantly between different tissues and with vessel size. An EC length of 100 μm is assumed in this study to translate the number of cells through which a signal is transmitted, into a longitudinal distance. Due to the circumferential symmetry, only one SMC is implemented at each discrete axial position along the vessel (Fig. 2). We assume that each cell is connected with its neighbors in the same layer and with overlapping cells on the other layer. Only one EC at a given axial position is simulated, and identical ECs are assumed in the circumferential direction (Fig. 2). The overlapping arrangement of ECs is simplified and replaced by a serial arrangement with regular end-to-end couplings, as shown in Fig. 2. The ECs' effect on a neighboring SMC is estimated by multiplying the myoendothelial flux into a SMC by 15 (i.e., one for each of the 15 identical ECs that overlap the SMC). The simulated vessel segment is 3 mm long and incorporates 450 ECs and 450 SMCs. (Note that only 30 of the 450 ECs are simulated, since there are 15 identical ECs in each longitudinal position.) An actual vessel segment of the same length should contain a higher number of cells that is dependent on the vessel's diameter. The assumption of circumferential symmetry allows us to significantly reduce the number of simulated cells and thus the number of differential equations.

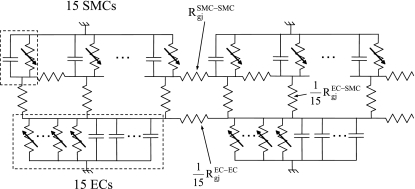

The electrical equivalent of the model vessel is shown in Fig. 3. We assumed electrically sealed ends (26), small intracellular and extracellular resistances, and negligible effect of tight junctions between ECs. The model assumes that the individual ECs and SMCs are isopotential (22) and without intracellular concentration gradients. For spatially uniform endothelial and/or smooth muscle stimulation, the vessel model is equivalent to a two-cell EC/SMC model, a scenario that has been examined elsewhere (29, 30).

Fig. 3.

The electrical analog of the vessel model. Gradients in the circumferential direction are negligible, and each cell is connected with its neighbors on the same layer and with the overlapping cells on the adjacent layer. Fifteen identical ECs are assumed, and the effect of ECs on neighboring SMCs is included by multiplying myoendothelial fluxes into a SMC by 15 times (i.e., resistance decreases 15-fold). Rgj, gap junction resistance.

Intercellular Communication

Cell coupling through gap junctions.

Homocellular gap junctions are present in the endothelium and smooth muscle, but are usually more prevalent in the endothelium (17, 20, 40, 46). Myoendothelial gap junctions, connecting SMCs with ECs, are present in RMA (25, 40), although they may be absent in some other vessels (46). The homo- and heterocellular gap junctions are thought to be nonselective and permeable to ions, as well as to IP3 molecules (3, 5). In this model, all neighboring cells within the smooth muscle or the endothelial layer are connected via homocellular gap junctions, while myoendothelial gap junctions connect overlapping EC and SMCs.

Ionic coupling.

We used a novel approach to account for the electrical coupling of neighboring cells. The detailed balances in intracellular ionic concentrations enable us to partition the total current flow between two cells into currents carried by individual ions (Eq. 1). In this way, current flow and ionic exchange can be monitored simultaneously. The ionic fluxes through the gap junctions are expressed by four independent Goldman-Hodgkin-Katz equations, one for each ionic species (Ca2+, Na+, K+, and Cl−) (Eq. 2) (29, 30):

| (1) |

| (2) |

where Igj is the total ionic current flowing from cell n to m; S = Ca2+, K+, Na+, Cl−; Vgj = Vmn − Vmm is the potential drop across the gap junction that is equal to the difference between Vm of cell n and cell m; [S]in is the intracellular concentration of ion S in cell n; and zs, F, R, and T represent the valence of ion S, the Faraday's constant, the gas constant, and the absolute temperature, respectively. The ionic permeabilities depend on the connexin isoforms participating in channel formation and their phosphorylation state, but such dependencies have not been incorporated in the model at this stage. Instead, the permeability, P, is assumed to be the same for all four ions (i.e., gap junctions are nonselective) and represents resultant behavior of various gap junction channels. This parameter has been arbitrarily assigned in previous studies, but can be estimated from the total gap junction resistance (Rgj), as we have recently described in Ref. 29:

| (3) |

Rgj can be determined experimentally, and some values for different vascular beds exist in the literature. Supplemental Table S2 summarizes different experimental estimates of Rgj, as well as values utilized in previous theoretical studies. The control values utilized in this study are based on this data. Similar simulation results would be obtained if the Goldman-Hodgkin-Katz equations were replaced with an additive model, as described in Ref. 27, in which the fluxes are proportional to a linear combination of concentration and potential differences, and the gap junction permeability.

IP3 coupling.

The IP3 flux through the gap junction was assumed to be proportional to the IP3 concentration difference between the two cells:

| (4) |

The permeability coefficient, pIP3, has not been determined experimentally. Koenigsberger et al. (32) utilized a value for the myoendothelial IP3 permeability of 0.05 s−1, for a gap junctional resistance per SMC of 0.9 GΩ. The value of the IP3 permeability between two overlapping cells utilized in this study (pIP3EC-SMC = 0.0033 s−1) corresponds to the same total cell permeability of the earlier study. (Note: the permeability has to decrease 15-fold to account for the distribution of flux into 15 overlapping cells.) The permeability of IP3 should be inversely proportional to Rgj, because an increase in the number of gap junction channels increases, in the same proportion, both the electrical conductance and permeability for larger molecules. Based on the assumed values for RgjEC-EC and RgjSMC-SMC (Supplemental Table S2), the intercellular permeabilities of IP3 in the endothelial and smooth muscle layers were adjusted accordingly (i.e., pIP3EC-EC = 13.6 s−1; pIP3SMC-SMC = 0.53 s−1). The IP3 permeability is larger in the endothelium than in the smooth muscle due to the smaller endothelial Rgj. The regulation of the macromolecule permeability relative to electrical conductance in gap junction channels is not taken into account.

NO/cGMP pathway.

The EC (44) and SMC (28) models were modified to include a description for myoendothelial communication through the NO/cGMP pathway, as previously described (29). Simultaneous measurements of Ca2+ and NO in agonist-stimulated ECs indicate that NO production is regulated by cytosolic calcium (2, 11, 36). EC may also release NO in a Ca2+-independent fashion, under some conditions, but such release is not accounted by the model at this stage (1). Thus we assumed that the relative NO production rate depends only on EC Ca2+ concentration with a sigmoidal function. Once released by the endothelium, NO can freely diffuse across cell membranes and reach the SM to exercise its vasodilatory action. Theoretical models of NO transport in arterioles (49) predict that the concentration of the endothelium-derived NO in the smooth muscle is proportional to the EC NO release rate, and the concentration profile is relatively flat in the smooth muscle in the absence of significant extravascular scavenging. Equations and parameters that relate EC intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) to the NO levels in the smooth muscle are presented in Ref. 29. The concentration of the endothelium-derived NO in the smooth muscle can affect SMC [Ca2+]i and Vm by modifying four cellular components, as described earlier (Fig. 1).

Length Constants

A blood vessel can be approximated from the electrical point of view as a cable with certain membrane and internal conductances (7, 26). In a passive linear cable with infinite length, the steady-state spread of a local potential change is attenuated exponentially:

| (5) |

where x is the distance along the vessel from the stimulus site, and ΔVm,max is the maximum ΔVm at the local site [i.e., ΔVm(x = 0)]. The constant (λ), referred to as the cable length constant, characterizes the attenuation and quantifies the extent of spread of voltage changes and the distance that information can be transmitted. If the cable's length (L) is finite (i.e., comparable to λ), the attenuation is not exponential. In a segment with sealed ends, the ΔVm profile is described by the following equation:

| (6) |

where y is the location of the stimulus site (i.e., 0 < y < L). Equation 6 is fitted to SMC ΔVm profiles predicted during current and ACh stimulation, and the length constants λel and λel,ACh, respectively, are estimated.

In a similar fashion, a length constant can be defined for the attenuation of the EC Ca2+ spread along the vessel axis following stimulation and an increase of intracellular Ca2+ at the local site. Fitting the Ca2+ profile with an exponential function yields an apparent length constant for the Ca2+ spread (λCa):

| (7) |

where Δ[Ca2+]i,max is the EC Ca2+ elevation at the ACh stimulation site {i.e., Δ[Ca2+]i(x = 0)}. The exponential function was used because the Ca2+ spread in the endothelium was much smaller than the length of the vessel examined, and despite the fact the Ca2+ spread is affected by the diffusion of IP3 in a nonlinear fashion.

Numerical Methods

Each EC and SMC was modeled with 11 and 26 differential equations, respectively, and the vessel segment was described by a system of 12,030 differential equations (i.e., 30 ECs × 11 equations/EC + 450 SMCs × 26 equations/SMC). The equations were coded in Fortran 90 and solved numerically using Gear's backward differentiation formula method for stiff systems (IMSL Numerical Library routine). The maximum time step was 4 ms, and the tolerance for convergence was 0.0005. Equationss 6 and 7 were fitted in their corresponding domains to the predicted profiles using the least squares method. Both the length constant and the maximum local response were optimized in the fittings.

RESULTS

To examine possible differences in mechanisms and properties of spreading responses induced by agonist and electrical stimulations and the physiological relevance of the latter, we performed simulations with both types of stimuli. Simulations with blocked Kir channels and with multiple layers of SMCs are presented in the Supplement.

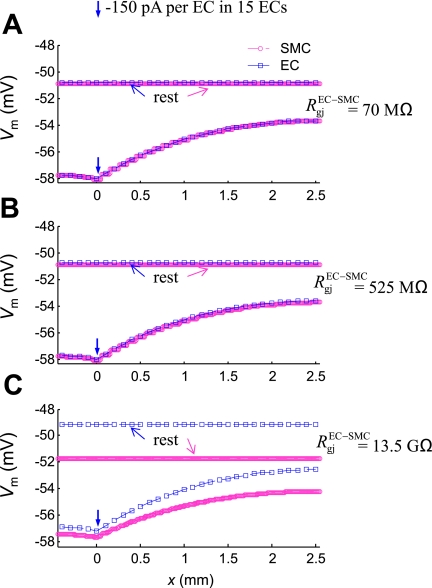

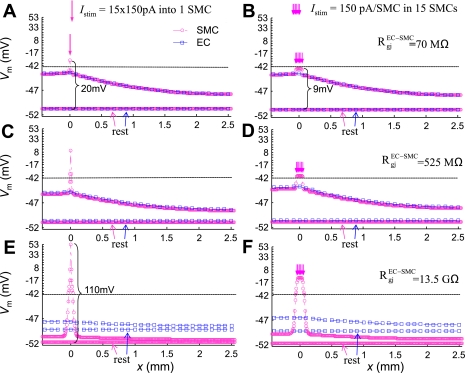

Electrical Stimulation

In Fig. 4, a hyperpolarizing current (−150 pA per EC) was injected for 3 s into the ECs located at x = 0. (Note that, due to circumferential symmetry, the current was injected to every EC located at x = 0). The circles and squares represent Vm in SMCs and ECs, respectively, as a function of their location along the longitudinal direction (x). The maximum ΔVm occurred at the local site and was attenuated with distance. The Vm profile is fitted well by Eq. 6 with an apparent length constant, λel = 1.6 mm (see Supplemental Fig. S1, solid line). [Note that a simple exponential function does not adequately fit the profile and overestimates the length constant.] Low and intermediate values for RgjEC-SMC of 70 MΩ or 525 MΩ (i.e., equivalent to 4.7 MΩ and 35 MΩ per single SMC, respectively) (40) result in almost identical EC and SMC Vm. Despite the significant difference in the two resistances, there was no observable difference in the Vm profile (Fig. 4, A and B). A high RgjEC-SMC of 13.5 GΩ [i.e., equivalent to 900 MΩ per single SMC (54)] affects the resting EC and SM Vm, but does not affect λel (Fig. 4C). Overall, a significant increase in RgjEC-SMC had only a moderate effect on the conduction of signals initiated in the endothelium.

Fig. 4.

The effect of myoendothelial Rgj on EC (□) and SMC (○) Vm in the 3-mm-long vessel at rest and at time t = 3 s, after injection of a hyperpolarizing current (−150 pA per EC, for 3 s) into the ECs located at x = 0. Simulations are shown for a low RgjEC-SMC = 70 MΩ (A), an intermediate RgjEC-SMC = 525 MΩ (B), and high RgjEC-SMC = 13.5 GΩ (C).

In a series of simulations, the vessel was also stimulated locally at the SM side. Figure 5 presents SMC Vm as a function of longitudinal distance for two different stimulation protocols, utilizing three different values for RgjEC-SMC. A significant depolarizing current (15 × 150 pA) was injected into a single SMC located at y = 500 μm (Fig. 5, A, C, and E). Alternatively, all SMCs connected to the same EC were stimulated by current injection (150 pA per SMC) (Fig. 5, B, D, and F) (similar to the arteriolar-segment voltage-clamp protocol presented in Ref. 9). Contrary to the EC stimulation in Fig. 4, there was a biphasic response when the vessel was stimulated from the SM side. The stimulated cell(s) exhibited significant depolarization that was more pronounced when RgjEC-SMC was high (20 mV in Fig. 5A vs. 110 mV in Fig. 5E) and when the same total current was injected in a single vs. a series of SMCs (20 mV in Fig. 5A vs. 9 mV in Fig. 5B). Away from the stimulus site, the length constant of the electrotonic spread was maintained in all four scenarios and was similar to the length constant observed during the EC stimulation (λel = 1.6 mm). The amplitude of distant depolarization, however, decreased as the RgjEC-SMC value increased (i.e., at x = 2.5 mm, there is 3-mV depolarization in Fig. 5A vs. 0.5 mV in Fig. 5E).

Fig. 5.

EC (□) and SMC (○) Vm in the 3-mm-long vessel at rest and at t = 3 s, after injection of a depolarizing current. 15 × 150 pA were injected for 3 s into either a single SMC (A, C, and E) or to 15 SMCs (B, D, and F). Simulations are shown for a low RgjEC-SMC = 70 MΩ (A and B), an intermediate RgjEC-SMC = 525 MΩ (C and D), and a high RgjEC-SMC = 13.5 GΩ (E and F). A large depolarization at the local site is predicted that becomes more pronounced as RgjEC-SMC increases, and when the same total current is injected into one vs. many SMCs.

The cable length constant can be affected by the gap junction resistances in the endothelial and smooth muscle layers. Some experimental values for homocellular Rgj have been reported in different vascular beds (Supplemental Table S2), but literature values vary significantly for the interendothelial Rgj (RgjEC-EC). Table 1 summarizes model predictions for λel utilizing different values for the homocellular gap junction resistances. For these simulations, the endothelium was stimulated with current injection similar to Fig. 4. An RgjEC-EC in the lower range of the previously reported values (i.e., 3.3 MΩ) yields a cable length constant that is consistent with experiments in RMA (47). Based on this observation, we utilized this value for RgjEC-EC in this study. Disruption of the endothelial gap junctions (i.e., RgjEC-EC = ∞) reduced the length constant by 20-fold, whereas disruption of the smooth muscle gap junctions (i.e., RgjSMC-SMC = ∞) had no significant effect on λel. In order for the SM layer to conduct changes in Vm similarly to the endothelium, RgjSMC-SMC has to be reduced to a value 152 times smaller than RgjEC-EC. This is due to the SMCs' perpendicular orientation relative to the vessel's axis and the number of SMCs assumed to span the length of an EC. Thus the endothelium is the major pathway for the electrotonic communication in the model. The estimated λel does not depend significantly on the magnitude and polarity of the injected current, provided that the resulting ΔVm remains within physiological range. Thus the vessel behaves similar to a linear cable in the physiological range of Vm, in agreement with experiments (Fig. 3 in Ref. 26).

Table 1.

Predicted electrical length constant, λel (mm)

|

RgjSMC-SMC, MΩ |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RgjEC-EC, MΩ | 3.3/15 × 15 | 3.3/15 | 3.3 | 84.7 | ∞ |

| 3.3 | 1.6 | 1.6 | |||

| 17.5 | 0.67 | ||||

| 31.8 | 0.5 | ||||

| ∞ | 1.45 | 0.46 | 0.23 | 0.07 | |

Rgj, gap junction resistance; EC, endothelial cell; SMC, smooth muscle cell; ∞, infinity.

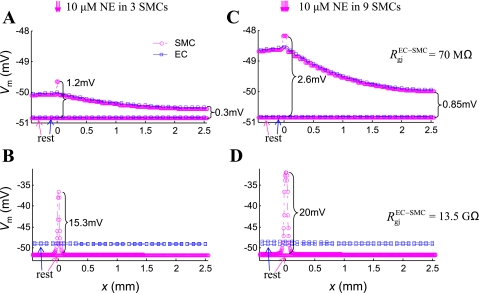

NE and ACh Stimulation

Figure 6 presents the ΔVm along the vessel, after 6 s of localized NE application. (Supplemental Fig. S2 shows corresponding simulations in the model with three layers of SMCs). In Fig. 6, A and B, three adjacent SMCs were stimulated with saturating concentration of NE (10 μM). In the model, NE generates a depolarizing current through activation of the NSC channels (Fig. 1). Simulations were performed for low (Fig. 6A) and high (Fig. 6B) RgjEC-SMC. The same stimulus had a significantly higher impact on the SMCs at the local site, if the SM was not well coupled to the endothelium (1.2 mV hyperpolarization in Fig. 6A vs. 15.3 mV in Fig. 6B). In both cases, the predicted effect of NE away from the stimulus site was small. In the first case (Fig. 6A), ΔVm were conducted effectively along the vessel, but the distant response was small, because the total NE-induced transmembrane current was insufficient. In the second case (Fig. 6B), the NE-induced transmembrane current did not diffuse to other cells and produced a large local ΔVm. This change, however, was poorly conducted to distant sites. In Fig. 6, C and D, nine adjacent SMCs were stimulated with a saturating concentration of NE (10 μM). When the cells were sufficiently coupled with ECs (i.e., low RgjEC-SMC), local and distant responses to NE were amplified as a result of the increased number of stimulated cells (Fig. 6C).

Fig. 6.

EC (□) and SMC (○) Vm in the 3-mm-long vessel at rest and at t = 6 s, after local NE application. SMCs are stimulated for 6 s with a saturating concentration of NE (10 μM). A: three adjacent cells are stimulated, and a strong myoendothelial coupling is assumed (RgjEC-SMC = 70 MΩ). B: three SMCs are stimulated, and a weak myoendothelial coupling is assumed (RgjEC-SMC = 13.5 GΩ). C: nine SMCs are stimulated, and a strong myoendothelial coupling is assumed (RgjEC-SMC = 70 MΩ). D: nine SMCs are stimulated, and a weak myoendothelial coupling is assumed (RgjEC-SMC = 13.5 GΩ). The same agonist stimulus has a significantly larger effect at the local site, if the SM is poorly coupled to the endothelium.

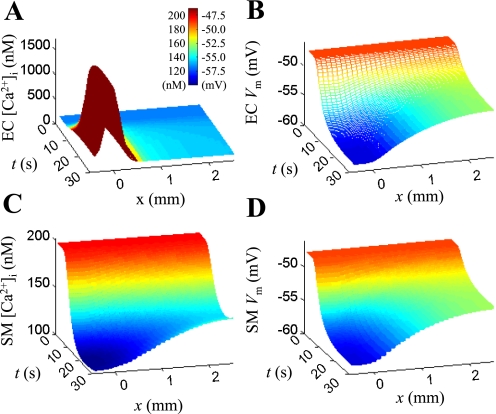

Figure 7 shows a representative ACh-induced conducted response. (Supplemental Fig. S3 shows corresponding simulations in the model with three layers of SMCs.) The simulation scenario mimics the experimental protocol from an earlier study of conducted vasoreactivity in RMA (47). The difference between the in silico and the in vitro study is that a sustained local application of the agonist is simulated here. In experiments, transient focal stimulation is utilized to limit the diffusion of agonist away from the local site. Figure 7 shows the endothelial Ca2+ concentration (A), the endothelial Vm (B), the smooth muscle Ca2+ concentration (C), and the smooth muscle Vm (D) as a function of time and distance from the stimulation site. First, a continuous and uniform prestimulation of the vessel with 200 nM of NE is simulated until a steady-state is reached (t = 0). This results in an elevation of the SM Ca2+ along the entire vessel to ∼200 nM. At time t = 2 s, ACh is applied locally to 15 ECs located at distance y = 400–500 μm from the inlet of the arteriole. The concentration of ACh is not specified, but it is assumed that it increases the IP3 release rate (QGIP3,ss) from 0 to 0.55 nM/ms. IP3 generation increases the [Ca2+]i in the ECs (Fig. 7A). In response to the elevation of [Ca2+]i, the SKCa and IKCa channels open and hyperpolarize the cell (Fig. 7B). This hyperpolarization spreads rapidly to neighboring ECs and SMCs via gap junctions (Fig. 7, B and D). Hyperpolarization of the SMCs closes the voltage-operated Ca2+ channels and reduces intracellular calcium (Fig. 7C).

Fig. 7.

Model responses to local acetylcholine (ACh) stimulation in a vessel prestimulated with 200 nM of NE and with RgjEC-SMC = 525 MΩ. From time t = 2 s, the ECs at position x = 0 are continuously stimulated with ACh [IP3 release rate (QIP3,ss) = 0.55 nM/ms]. A: endothelial [Ca2+]i as a function of time and distance from stimulus site. B: endothelial Vm as a function of time and distance from stimulus site. C: smooth muscle [Ca2+]i as a function of time and distance from stimulus site. D: smooth muscle Vm as a function of time and distance from stimulus site.

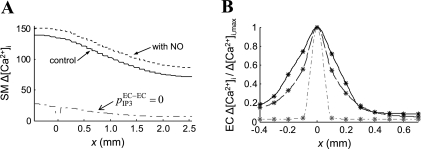

Figure 8A depicts relative Ca2+ changes in the SM along the vessel calculated from Fig. 7C. A 100% change denotes a reduction of Ca2+ concentration to its resting value before NE prestimulation (i.e., from SMC NE [Ca2+]i = 200 nM to SMC rest [Ca2+]i = 130 nM). The model predicts significant Ca2+ change throughout the vessel segment. Incorporation of the NO pathway in the simulations (Fig. 8A; dashed line) increased slightly the smooth muscle Ca2+ reduction at the local and at the distant site. The NO/cGMP pathway activates at the local site BKCa channels in SMCs (Fig. 1), which generate hyperpolarizing currents. Because the myoendothelial coupling is strong, these currents are transmitted and enhance SM hyperpolarization at distant sites as well. The result is higher Ca2+ reduction (i.e., relaxation). Inhibition of the interendothelial IP3 diffusion impaired significantly the ACh-induced SM Ca2+ reduction (Fig. 8A, dashed-dotted line). The inhibition of IP3 diffusion abolishes EC Ca2+ spread (Fig. 8B), which reduces the number of ECs with open SKCa and IKCa channels. Consequently, the total hyperpolarizing current generated at the local site is smaller, and the SM relaxation is impaired.

Fig. 8.

A: predicted changes in SM [Ca2+]i during local ACh application in a vessel prestimulated with NE. 100% change indicates a reduction in [Ca2+]i to the resting value before NE application. The figure shows simulations with (dotted line) and without (solid line) contribution from the NO, and after inhibition of endothelial IP3 diffusion (pIP3EC-EC = 0). B: normalized steady-state endothelial Ca2+ profiles during local stimulation with ACh. Under control conditions (solid line), the Ca2+ spread was limited to ∼300 μm (three ECs). Inhibition of axial IP3 diffusion (pIP3EC-EC = 0) practically abolished the Ca2+ spread. One hundred-fold greater permeability of the endothelial gap junctions to Ca2+ extended Ca2+ spread to <400 μm.

Figure 8B investigates the endothelial Ca2+ spread along the vessel. The difference between the basal prestimulation level and the poststimulation steady-state value of EC Ca2+ (i.e., Fig. 7A; t = 0 and t = 30 s) is depicted as a function of the distance (x) from the stimulation site. Ca2+ changes are normalized by the maximum change at the local site. Under control conditions (solid line), significant Ca2+ elevation was observed only within 300 μm from the stimulus site (apparent length constant, λCa = 0.17 mm). Inhibition of axial IP3 diffusion (i.e., pIP3EC-EC = 0, dash-dotted line) practically abolishes the Ca2+ spread. In simulation with EC gap junctions impermeable to IP3 and 100 times more permeable to Ca2+ than control (i.e., pIP3EC-EC = 0; pCaEC-EC = 100P, dashed line), Ca2+ spread is also limited (i.e., <400 μm, λCa = 0.15 mm).

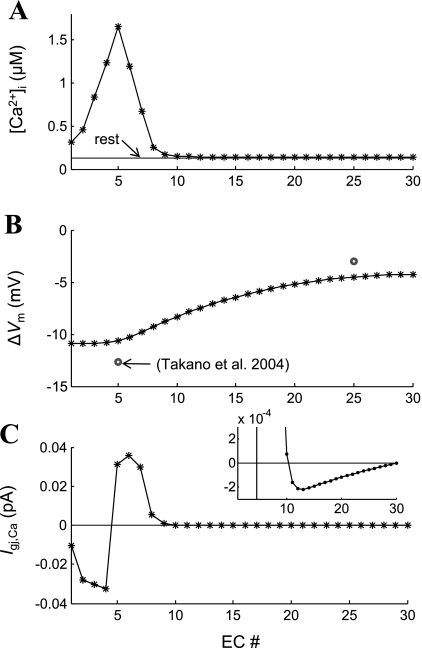

Figure 9 examines the IP3-independent Ca2+ electrodiffusion through the endothelial gap junctions. Figure 9, A and B, shows the poststimulation steady-state Ca2+ and ΔVm, respectively, in ECs along the vessel's axis for the simulations presented in Fig. 7 (t = 30 s). The Ca2+ flux between neighboring cells is presented as Ca2+ current (Fig. 9C). A positive current denotes Ca2+ ions flowing to the right, and a negative current to the left. There is a maximum 500 nM difference in [Ca2+]i and a maximum 0.5-mV difference in Vm between neighboring ECs at the local site. Under these conditions, the concentration gradient dominates the electrochemical gradient, and Ca2+ ions move away from the stimulated EC. The Ca2+ current through the gap junctions between the fifth and the sixth EC is 0.03 pA. Away from the stimulation site, the concentration difference between neighboring cells decreases, and so does the Ca2+ current. Interestingly, after the 10th EC, a very weak Ca2+ current flows toward the stimulation site (i.e., the current becomes negative) as the electrical field dominates the electrochemical gradient across the gap junction (Fig. 9C, inset).

Fig. 9.

Endothelial Ca2+ electrodiffusion during local ACh stimulation. IP3 release rate is increased in the fifth EC simulating local ACh stimulation. A: endothelial [Ca2+]i profile is shown as a function of the number of cells from the inlet of the vessel. B: predicted hyperpolarization following stimulation (*) is presented next to experimental data from Ref. 47 (○). C: intercellular Ca2+ current presenting Ca2+ flux between neighboring ECs (Igj,Ca). Positive values denote Ca2+ flow from the left to the right. Inset shows data at 100-fold higher resolution. Small Ca2+ fluxes toward the stimulation site appear after the 10th EC.

Effect of Stimulus Strength on Vm and Ca2+ Spread

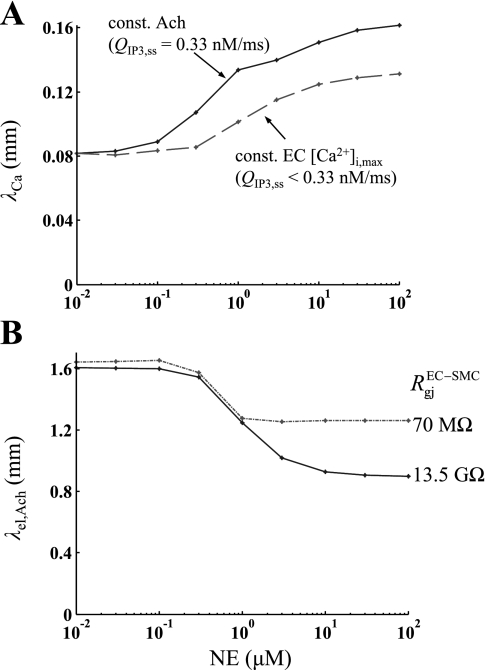

We investigated if the strength of agonist stimulation can affect the rate of decay of the conducted signal. Figure 10 examines the effect of NE prestimulation on the Ca2+ and electrotonic spread. The model vessel was stimulated uniformly with different concentrations of NE before local stimulation of the endothelium with ACh. Figure 10 shows the predicted length constants for the endothelial Ca2+ spread (λCa) (A) and for the SM Vm attenuation λel,ACh (B), for NE concentrations varying from 10−2 to 102 μM. In Fig. 10A, the stimulating ACh concentration was either held constant (solid line) or was modified to produce the same local [Ca2+]i increase at each NE concentration (dashed line). The λCa can increase significantly with increasing levels of NE prestimulation. This effect is reduced but is not abolished if the same local Ca2+ transient is preserved at each NE concentration (dotted line). On the contrary NE prestimulation can reduce λel,ACh and thus the electrotonic spread (Fig. 10B). The significance of this effect is increased for high myoendothelial gap junction resistance (solid line). Large NE prestimulation also reduces the magnitude of the SMC ΔVm (data not shown). For endothelium initiated responses, as the concentration of ACh increases so does the local Δ[Ca2+]i, ΔVm, and λCa, but not λel,ACh (data not shown).

Fig. 10.

A: the length constant of Ca2+ (λCa) decrease from the site of local ACh stimulation is shown for different levels of NE prestimulation. ACh stimulus strength was either held constant (QIP3,ss = 0.33 nM/ms) (solid line) or was adjusted to produce the same local Ca2+ response at each prestimulation level (dashed line). B: the length constant of Vm attenuation (λel,ACh) is shown for vessel prestimulation with different NE concentrations. ACh stimulus strength was held constant (QIP3,ss = 0.33 nM/ms), and simulations were repeated for a weak (RgjEC-SMC = 13.5 GΩ) or a strong (RgjEC-SMC = 70 MΩ) myoendothelial coupling. NE prestimulation increases the EC Ca2+ spread, but reduces Vm spread.

DISCUSSION

Role of Gap Junctions in Vm Spread

Gap junctions composed of specific connexins are central to the propagation of dilations (18, 53). Electrotonic conduction of ΔVm through gap junctions is considered to be the major mechanism of spreading responses in a number of vascular beds (20). The endothelium, rather than the SM, seems to be the major conducting pathway in RMAs, as supported by experiments with disrupted endothelial layer (47). Model simulations with electrical and agonist stimuli confirm these findings. Simulations demonstrate that the cable length constant, λel, is inversely proportional to the square root of RgjEC-EC. (Note: in a passive linear cable, the length constant exhibits the same dependence on axial resistance). The exact value of RgjEC-EC in RMA is not known. However, a value of 3.3 MΩ was estimated by Lidington et al. (34) for rat skeletal muscle. Based on this value, the predicted λel was in close agreement with the experimental λel value determined in guinea pig small-intestine arterioles (26), hamster feed arteries (15), and with dilatation data from RMA (20, 47). After disruption of the endothelial gap junctions, the ability of the model vessel to carry spreading responses was minimized, as indicated by a large decrease in λel (Table 1).

Myoendothelial gap junction resistance plays also an important role in the model's behavior. Sandow and Hill (40) provided an estimate for RgjEC-SMC in proximal RMA, based on morphological observations. A resistance value of 70 MΩ per gap junction and two gap junctions per SMC was reported (corresponding to 35 MΩ per SMC). The estimate of Yamamoto et al. (54) in guinea pig mesenteric arteries was significantly higher (i.e., 900 MΩ per single SMC). The incidence of myoendothelial gap junctions may vary between vascular beds and may even be significantly smaller in proximal rather than in distal RMA (40). For these reasons, a wide range of values were utilized in the model (i.e., RgjEC-SMC = 70–13,500 MΩ cell to cell resistance or 4.7–900 MΩ total myoendothelial resistance per SMC).

In simulations utilizing high RgjEC-SMC, conduction of a signal initiated in SMCs was limited compared with a signal initiated in ECs (Figs. 4C vs. 5, E and F). Such differential electrical communication is consistent with responses seen and simulated in some vascular beds, for example, in hamster feed arteries of the retractor muscle (43) and in Ref. 9. Experimental data suggest, however, that, in RMA, the endothelial and smooth muscle layers function as an electrical syncytium, and ΔVm initiated in the ECs and SMCs are conducted similarly (47). Thus a value of RgjEC-SMC in the lower range of Supplemental Table S2 is more likely in RMA. Indeed, for RgjEC-SMC between 70 and 525 MΩ, similar hyperpolarization/depolarization appear away from the stimulus site, regardless of whether the vessel is stimulated in the endothelium or smooth muscle side (at x = 2.5 mm, ΔVm = ∼3 mV in Fig. 4, A and B, and Fig. 5, B and D). However, even for low RgjEC-SMC, there is a difference between stimulation in the two sides of the vessel wall. There is a significant local ΔVm when the current is injected in the SMC(s) that attenuates rapidly over the next few SMCs. This change is more pronounced if the same current is injected in a single vs. an array of neighboring cells (Figs. 5, A–D), because, in the latter case, the effective resistance between the stimulus site and the endothelium is smaller.

Current vs. Voltage-clamp Stimulations

Our simulation results are in agreement with model results presented by Diep et al. (9). This earlier study investigated spreading responses after ECs or SMCs were clamped at a given Vm ( ΔVm,max = 15 mV), rather than current clamp used in the present study. Their model predicted that SM-initiated responses conducted poorly along the vessel, and a substantial voltage response in the endothelium could only be generated when a sufficient number of SMCs were clamped simultaneously. The authors attributed this behavior to poor coupling of the SMC with adjacent cells and their perpendicular orientation to the vessel axis. Our simulations using the same effective myoendothelial resistance (Fig. 5, E and F) show similar trends for SM-initiated responses. Our simulations, however, point out that a larger total injected current is required to clamp an EC vs. a SMC or many vs. few SMCs, to a given Vm. When the resistivity with neighboring cells is high, a large ΔVm of the stimulated cell can be achieved with a relatively small injected current (i.e., the current does not diffuse and causes a larger depolarization/hyperpolarization; Figs. 5A vs. 5E). Thus, if the same Vm clamp is applied to an EC and a SMC, the injected current will be higher in the well-coupled endothelium. The two studies combined suggest that distal responses are more sensitive to the total current injected at the local site and less to the achieved membrane depolarization/hyperpolarization at the local site.

Both the current and the voltage clamp, however, introduce a bias in evaluating conduction when applied to cells with different gap junction connectivity. A voltage clamp will favor conducted responses in well-coupled systems (i.e., a higher stimulating current is introduced). A current clamp will overestimate conduction in poorly coupled systems (i.e., by not accounting for the effect of Vm on agonist-induced transmembrane currents). Simulations presented in Fig. 6 are independent of the bias introduced by the choice of the stimulation protocol (i.e., voltage or current clamp). Simulations of agonist-induced reactivity are physiologically more relevant and differ from both voltage and current clamps. They can also be utilized to predict how many cells need to be stimulated in vivo to produce an observable effect at distant sites. Simulations show that a saturating concentration of NE applied to three SMCs induces a small response away from the stimulus site (Fig. 6A). The ability of the SM to initiate a conducted electrotonic signal increases as the myoendothelial coupling increases (Fig. 6, A vs. B) and when more SMCs are stimulated (Fig. 6, C vs. A). Interestingly, the local Vm response to NE depends significantly on the myoendothelial connectivity, and SMCs that are not well coupled produce significantly higher local depolarization to NE. Thus, as coupling decreases, the ability of the SMCs to generate a distant signal decreases, but the sensitivity of these cells to agonist stimulation locally increases.

In vascular beds, where SMCs are not well coupled with neighboring ECs and SMCs, the stimulation of a few SMCs can produce large, localized changes in arteriolar tone. On the other hand, stimulation of a number of ECs or SMCs has the potential to generate spreading responses and regulate vasoactivity over larger vascular segments (9). The physiological importance of the vessel's ability for SMC-initiated localized constriction needs to be further investigated. For example, what is the difference in the regulation of blood supply by a strong, local constriction instead of a weaker, spreading constriction over a larger vascular segment?

Physiological Relevance of Stimulatory Protocols

Figure 6 demonstrates that saturating concentrations of agonist can impose different levels of maximum depolarization depending on the homo/heterocellular connectivity of the cells and the number of the stimulated cells. Thus the physiological relevance of a voltage-clamp stimulation protocol is difficult to assess and should be different in intact vessels from isolated cells. In isolated SMCs, saturating NE concentration should depolarize Vm up to −40 to −30 mV, and thus voltage clamps in that range are considered physiological for isolated SMCs. As the homo- and heterocellular coupling of the SMC with neighboring cells increases, the maximum physiological value should decrease. In addition, model simulations with saturating concentration of agonist in either layer reveal maximum transmembrane currents in the order of a few tens of picoamperes (i.e., determined mostly by the maximum conductance of KCa channels in ECs and the NSC in SMCs). Since the level of homo- and heterocellular coupling affects agonist-induced ΔVm, the maximum transmembrane currents that occur in vivo will be affected as well. Thus, for both the voltage and the current clamp, the maximum physiological magnitude will depend on the connectivity of the stimulated cell.

These considerations suggest supraphysiological current injections per single EC in Figs. 4 and 5 and potentially in the majority of experimental studies of conducted vasoreactivity that utilize current injection in a single cell with intracellular microelectrodes. The use of a significant intracellular current injection (hundreds of picoamperes) in experimental studies is necessary to evoke robust responses, e.g., 1–3 nA in vessels 25–60 μm in diameter (26). Similar total current is predicted by the model. Because of circumferential symmetry, in a vessel with 42 μm diameter, 150 pA per EC will correspond to a total injected current of 3 nA (∼20 ECs in the circumferential direction).

Although such voltage clamps and current injections remain a useful experimental approach to characterize the electrical behavior of a vessel segment, this comparison suggests that, in vivo, multiple cells need to be stimulated to generate a significant conducted response.

Role of EC Ca2+ Spread

In hamster feed arteries, the conduction of hyperpolarization was augmented during ACh stimulation compared with electric current stimulation (15). This augmentation was indicated by an increase in the length constant from λel = 1.2 mm to λel,ACh = 1.9 mm. In the model, stimulation with ACh did not significantly increase the length constant (λel ≈ λel,ACh ≈ 1.6 mm). This lack of facilitation was due to limited endothelial Ca2+ spread following ACh stimulation (Figs. 7 and 8B). However, the limited but considerable ACh-induced Ca2+ spread amplified significantly the hyperpolarization at the local and distant sites. Elevation of Ca2+ in ECs near the stimulation site activates SKCa and IKCa channels, which contribute to the total current generated at the local site. Because the maximum current generated by individual cells is limited, EC Ca2+ spread increases the ability of focal stimuli to induce conducted response with physiologically relevant magnitude. The amplification of the current is approximately equal to the ratio of the distance of Ca2+ spread to the length of the stimulation site. In the simulations, inhibition of EC IP3 and Ca2+ spread impaired the SMC relaxation (Fig. 8A) by reducing local hyperpolarization from 10.7 to 3 mV. EC Ca2+ spread can also increase the number of BKCa channels in SMCs activated by the NO/cGMP pathway (Fig. 1) and further enhance the total hyperpolarizing current. However, this may have a small effect on the relaxation in the presence of strong endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor, and negligible NO effects on conducted responses have been reported in RMAs (52).

The predicted endothelial Ca2+ spread agrees with experimental studies on RMAs (47, 52) and certain other vessel types (12, 19, 46). For example, Fig. 5 in Ref. 47 shows that a noticeable EC Ca2+ increase appears only within a distance of 500 μm from the ACh stimulation site. On the other hand, studies in other vessels reported significant NO- and endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor-dependent components of the conducted response and suggested EC Ca2+ increase at remote sites (4, 13, 16, 43). These findings have been challenged by others (19, 51). Recently distant EC Ca2+ waves were observed in hamster feed arteries (10, 50) and transgenic mice cremaster muscle arterioles (48). Our simulations do not negate the possibility of different signal transduction mechanisms in spreading responses in various vessel types.

IP3-mediated Ca2+ Spread vs. Direct Interendothelial Ca2+ Diffusion

The mechanism responsible for the generation of a propagating Ca2+ wave along the endothelium remains unclear. In the model, the limited yet noticeable endothelial Ca2+ spread was mediated by axial IP3 diffusion and subsequent Ca2+ release from the stores. The relative importance of IP3 and Ca2+ diffusion depends on the assumed values for the gap junction permeabilities of the two species (pIP3EC-EC and PCaEC-EC. These parameters have not been experimentally determined, and previous theoretical studies have used arbitrary values. In this study, PCaEC-EC was inversely related to Rgj (Eq. 3).

For the control value of Rgj, direct Ca2+ diffusion (<0.04 pA in Fig. 9C) was much smaller compared with other transmembrane Ca2+ fluxes (∼1 pA) and thus had a negligible effect on the global [Ca2+]i. PCaEC-EC has to increase 100-fold to result in noticeable direct Ca2+ spread, but even then it was limited to 400 μm (Fig. 8B). The predicted contributions of IP3 and Ca2+ agree with the experimental data, which indicate that direct Ca2+ communication via homocellular gap junctions is not essential for Ca2+ waves (39). Some theoretical models of IP3-mediated intercellular Ca2+ waves have assumed negligible direct intercellular Ca2+ diffusion (31, 45). In mice cremaster muscle arterioles, Ca2+ waves were significantly faster than can be accounted for by the diffusion of IP3 or Ca2+, suggesting an underlying active mechanism [e.g., a regenerative release of IP3 triggered by ACh (48)].

Effect of Intercellular and Transmembrane Potential Gradients

Inhibition of endothelial KCa channels unmasked Ca2+-dependent, slow-conducted vasodilatation in hamster feed arteries (10). We used the model to examine if blocking conducted hyperpolarization can facilitate direct Ca2+ waves along the vessel axis and tested the hypothesis that the physiological Vm gradient inhibits longitudinal Ca2+ diffusion. The predicted intercellular Vm gradients (Fig. 9) agree with experimental recordings (47). Near the stimulation site, the electrical field across the gap junctions had a minimal effect on the Ca2+ spread, and the Ca2+ concentration gradient was the major determinant of a rather limited intercellular Ca2+ flux. The electrical field becomes dominant only far away and can reverse the diffusion of Ca2+ in a direction toward the stimulus site. The magnitude of this electrically driven intercellular Ca2+ flux is minimal and cannot affect [Ca2+]i.

In some EC types, hyperpolarization itself can increase [Ca2+]i by increasing the driving force for Ca2+ entry (35, 37). Therefore, it was speculated that conducted hyperpolarization could trigger Ca2+ transients that can activate NO release and dilate the vessel at distant sites (4). However, there is no direct evidence for the existence of such mechanism in spreading responses. It is also not clear if such hyperpolarization-induced Ca2+ changes would be adequate for distant dilatation (19). Our laboratory has previously investigated the controversial effect of Vm on [Ca2+]i in the isolated EC model (44) and showed that resting and plateau Ca2+ levels were rather insensitive to ΔVm. The magnitude of hyperpolarization associated with conducted responses in the model could not elicit a large Ca2+ transient. Consequently, conducted hyperpolarization did not trigger an endothelial Ca2+ wave and did not induce NO release, activation of SKCa and IKCa channels, or facilitated spreading responses.

Effect of Stimulus Strength

Simulation results (Fig. 10) indicate that the length constants of the Ca2+ and Vm spread may depend on the concentration of the applied agonist or the presence of other stimuli. These effects cannot be predicted in simplified cable models. The cable length constant depends on axial and radial resistances. Thus it can be modulated by agents that change the gap junction and cell membrane resistances. In the model, prestimulation with NE reduced λel,ACh by opening NSC channels and reducing SM membrane resistance (Fig. 10B). Haug and Segal (23) reported that activation of α1- and α2-adrenoceptors in feed arteries of the hamster retractor muscle inhibits conducted vasodilation. Using a cable model, they also showed that decreased SM membrane resistance or increased myoendothelial resistance could account for the inhibition. Gustafsson and Holstein-Rathlou (21) showed experimentally that angiotensin II increased the electrical length constant in RMA. They hypothesized that this was a result of increased cell-to-cell coupling or membrane resistance. Increased membrane resistance could result from agonist-induced inhibition of potassium channels in SMCs, but this mechanism was not incorporated into the model due to lack of appropriate direct experimental evidence. Our data suggest that SM prestimulation can significantly affect the radial resistivity of a vessel, which, in turn, can alter the observed distance of electrical conduction.

Experimentation with hamster feed arteries led Uhrenholt et al. (50) to hypothesize that SM tone could increase basal EC [Ca2+]i and sensitize the endothelium for Ca2+ wave propagation. A similar phenomenon was observed in the model by an increase in the length constant of the EC Ca2+ spread following SM prestimulation (Fig. 10A). NE prestimulation generated IP3 in the SM, which diffused to the ECs. The presence of a basal, subthreshold concentration of IP3 sensitized the endothelium to IP3 and ACh. This is due to the nonlinearity of store Ca2+ release (i.e., Ca2+ released from the stores is a sigmoidal function of IP3 concentration). Following NE stimulation and EC sensitization, the same concentration of ACh induces a larger Ca2+ response and an IP3-dependent Ca2+ wave with a larger λCa (Fig. 10A, solid line). Even imposing the same increase in IP3 at the local site gives a more dramatic Ca2+ increase in neighboring cells (sensitized by prestimulation). The result is an IP3-dependent Ca2+ wave with a larger λCa in the presence of NE (Fig. 10A, dashed line). Figure 10A also indicates that, at a given NE concentration, λCa increases with stronger ACh stimulation. On the other hand, the electrical length constant, λel,ACh, does not depend on the concentration of the stimulating agent (i.e., ACh) (data not shown), indicating that the vessel can be approximated from an electrical point of view as a linear cable.

The Effect of Multiple Layers of SMCs

The addition of multiple layers of SMCs into the vessel model did not change qualitatively the mechanisms and properties of conducted responses. However, multiple layers of SMCs increase radial current leak from ECs to SMCs, which reduces the magnitude and length constant of the responses conducted through the endothelium. For example, three layers of SMCs reduced the length constant and the maximum hyperpolarization in ACh-induced response by 36 and 20%, respectively (Fig. 9B vs. Supplemental Fig. S3B). In case of SM stimulation by NE or the NO/cGMP pathway, the additional layers of SMCs can generate more current and compensate for the increased radial leak at the distant sites (Supplemental Fig. S3, A and B vs. C and D). To allow effective current diffusion from the stimulated SMCs to the endothelium, the myoendothelial and radial SMC-to-SMC resistances should be low (Supplemental Fig. S2). Increasing the number of SMC layers does not eliminate the need for endothelium in mediating spreading responses. It follows from the symmetry that, if a single layer of SMCs conducts local stimulation poorly, then addition of another layer with identical parameters and stimulation will have no effect. This is because the net axial and radial resistances decrease in the same proportions and the cable length constant does not change.

Spread of Relaxation

The model does not include at this stage a description for Ca2+-induced force development and for the resulting changes in vessel diameter. Assuming that constriction and relaxation are proportional to Ca2+ changes in the smooth muscle, a preliminary comparison can be made between our simulation results and experimental data on spreading relaxations. SMC Ca2+ profiles predicted by the model and the actual relaxation profile obtained from RMA (47) show significant responses at distances 1.5 mm away from the stimulus site. The mechanical/dilatation length constant, determined by fitting an exponential to diameter changes, is typically between 1 and 2 mm, depending on the vessel type (20). The model gives SM Ca2+ and hyperpolarization profiles with length constants in the range of 0.9–1.6 mm (Fig. 10), depending on the NE prestimulation level.

Model Limitations

The model captures the major aspects of conducted responses in RMA and makes predictions about the parameters that can affect the transmission of information along the vessel. However, the study does not account for behavior seen in other vessels, such as Ca2+ waves over considerably greater distances and spreading vasodilation in the absence of ΔVm. The simulation results do not negate these experimental findings, and they suggest different type and expression levels of ion channels and Ca2+ handling machinery in those vessels. Spreading vasoreactivity depends also on vessel size. Single and multiple layers of SMCs were incorporated into the model to simulate arterioles and resistance arteries, but quantitative information for the subcellular components at each vessel size is not available.

The predictions are further limited by the uncertainty in a number of parameter values and by a number of simplifying assumptions. The EC length depends on the vessel type and size, and a representative value was chosen for this study. More general predictions can be made if the reported distances are normalized with respect to the assumed EC's length. The assumed arrangement of ECs may also influence spreading responses. ECs may overlap and form tortuous conduction pathways. The assumed circumferential symmetry and the regular end-to-end EC coupling may lead to an overestimate of the length constants. [Notice, however, that the overlapping arrangement of ECs is equivalent to the serial arrangement (both depicted in Fig. 2), if no current is leaking from the endothelium.] Circumferential heterogeneity would also arise from coupling each SMC to different underlying ECs, and it was reported that, on average, only two ECs are coupled to the same SMC (40). In Ref. 9, this was simulated by randomly connecting each SMC with 2 out of 16 underlying ECs. However, this heterogeneity in the myoendothelial coupling should have a negligible effect on axial signaling. The number of ECs coupled to each SMC was accounted for in this model by distributing the total gap junction permeability equally to all of the underlying cells in contact.

The RgjEC-EC is a critical parameter for conducted responses and has not been determined in RMA. Simulation results suggest RgjEC-EC close to the lower end of previously reported values. The permeability of gap junctions to IP3 is not known. In this study, pIP3EC-SMC, pIP3EC-EC, and pIP3SMC-SMC were assumed to be inversely proportional to RgjEC-SMC, RgjEC-EC, and RgjSMC-SMC, respectively. In an earlier study, pIP3EC-SMC = 0.05 s−1, and RgjEC-SMC = 900 MΩ per SMC were assumed, and the same product for these two values was maintained here. Although this parameter does not directly affect the axial communication, the excessive myoendothelial IP3 diffusion at larger pIP3EC-SMC may indicate that the pIP3 × Rgj product and/or the EC and SMC models are inaccurate.

Limitations in the isolated EC and SMC models have been discussed previously (28, 44). Uncertainty in parameter values and the absence of spatial resolution in the EC and SMC models present two of the most serious limitations. Parameters that affect transmembrane currents in particular can have an impact on predictions regarding passive and facilitated conduction, while parameters affecting the intracellular balance of IP3 and Ca2+ can determine the predicted Ca2+ spread. The lack of subcellular resolution may be acceptable from the electrical point of view (real cells are essentially isopotential), but the intercellular Ca2+ waves may depend on spatial distribution of ryanodine receptors and/or IP3Rs and Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release from the SR along the cells. A multicellular SM model with intracellular Ca2+ waves was proposed recently to study synchronization (27), but the development of EC and SMC models with Ca2+ waves, sparks, or pulsars is restricted by the absence of relevant tissue-specific parameter values.

Conclusions

A computational model of a vessel segment was developed to investigate spreading responses in RMAs and arterioles. The study advances previous theoretical work by using detailed models of EC and SMC and by accounting for changes in the concentration of intracellular species. Simulation results corroborate experimental findings that spreading vasorelaxation in RMAs mainly reflects Ca2+-independent, passive conduction of hyperpolarization along the endothelium. The model predicts that intercellular IP3 diffusion is more important than direct intercellular Ca2+ diffusion, and it can play a role in modulating spreading responses. Endothelial IP3 diffusion mediated limited but significant Ca2+ spread that amplified total current generated at the local site. The length constant of voltage or Ca2+ propagation depends on the presence and concentrations of stimulating agonists. Simulations demonstrate that intercellular uncoupling attenuates conducted responses but sensitizes cells to local agonist and electrical stimuli. Voltage clamp is a more appropriate experimental analog of local agonist stimulation in cells that are weakly coupled and current clamp in cells that are well coupled. Overall, the mechanisms that modulate conducted vasoreactivity are complex and are often difficult to assess using a reductionist approach and qualitative syllogisms. The development of detailed computational models holds promise for the elucidation of nonlinear interactions between system components and their potential effect on signal transmission.

GRANTS

This work was supported in part by American Heart Association Grant NSDG 0435067N and by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant SC1HL095101.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest are declared by the author(s).

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- 1. Ayajiki K, Kindermann M, Hecker M, Fleming I, Busse R. Intracellular pH and tyrosine phosphorylation but not calcium determine shear stress-induced nitric oxide production in native endothelial cells. Circ Res 78: 750–758, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Blatter LA, Taha Z, Mesaros S, Shacklock PS, Wier WG, Malinski T. Simultaneous measurements of Ca2+ and nitric oxide in bradykinin-stimulated vascular endothelial cells. Circ Res 76: 922–924, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brink PR, Ricotta J, Christ GJ. Biophysical characteristics of gap junctions in vascular wall cells: implications for vascular biology and disease. Braz J Med Biol Res 33: 415–422, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Budel S, Bartlett IS, Segal SS. Homocellular conduction along endothelium and smooth muscle of arterioles in hamster cheek pouch: unmasking an NO wave. Circ Res 93: 61–68, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Christ GJ, Spray DC, el-Sabban M, Moore LK, Brink PR. Gap junctions in vascular tissues. Evaluating the role of intercellular communication in the modulation of vasomotor tone. Circ Res 79: 631–646, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Crane GJ, Hines ML, Neild TO. Simulating the spread of membrane potential changes in arteriolar networks. Microcirculation 8: 33–43, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Crane GJ, Neild TO. An equation describing spread of membrane potential changes in a short segment of blood vessel. Phys Med Biol 44: N217–N221, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Crane GJ, Neild TO, Segal SS. Contribution of active membrane processes to conducted hyperpolarization in arterioles of hamster cheek pouch. Microcirculation 11: 425–433, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Diep HK, Vigmond EJ, Segal SS, Welsh DG. Defining electrical communication in skeletal muscle resistance arteries: a computational approach. J Physiol 568: 267–281, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Domeier TL, Segal SS. Electromechanical and pharmacomechanical signalling pathways for conducted vasodilatation along endothelium of hamster feed arteries. J Physiol 579: 175–186, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dong XH, Komiyama Y, Nishimura N, Masuda M, Takahashi H. Nanomolar level of ouabain increases intracellular calcium to produce nitric oxide in rat aortic endothelial cells. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 31: 276–283, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dora KA, Xia J, Duling BR. Endothelial cell signaling during conducted vasomotor responses. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 285: H119–H126, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Doyle MP, Duling BR. Acetylcholine induces conducted vasodilation by nitric oxide-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 272: H1364–H1371, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Duling BR, Berne RM. Propagated vasodilation in the microcirculation of the hamster cheek pouch. Circ Res 26: 163–170, 1970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Emerson GG, Neild TO, Segal SS. Conduction of hyperpolarization along hamster feed arteries: augmentation by acetylcholine. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 283: H102–H109, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Figueroa X, Chen CC, Campbell KP, Damon DN, Day KH, Ramos S, Duling BR. Are voltage-dependent ion channels involved in the endothelial cell control of vasomotor tone? Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 293: H1371–H1383, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Figueroa XF, Isakson BE, Duling BR. Connexins: gaps in our knowledge of vascular function. Physiology (Bethesda) 19: 277–284, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Figueroa XF, Paul DL, Simon AM, Goodenough DA, Day KH, Damon DN, Duling BR. Central role of connexin40 in the propagation of electrically activated vasodilation in mouse cremasteric arterioles in vivo. Circ Res 92: 793–800, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fleming I. Bobbing along on the crest of a wave: NO ascends hamster cheek pouch arterioles. Circ Res 93: 9–11, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gustafsson F, Holstein-Rathlou N. Conducted vasomotor responses in arterioles: characteristics, mechanisms and physiological significance. Acta Physiol Scand 167: 11–21, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gustafsson F, Holstein-Rathlou NH. Angiotensin II modulates conducted vasoconstriction to norepinephrine and local electrical stimulation in rat mesenteric arterioles. Cardiovasc Res 44: 176–184, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Haas TL, Duling BR. Morphology favors an endothelial cell pathway for longitudinal conduction within arterioles. Microvasc Res 53: 113–120, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Haug SJ, Segal SS. Sympathetic neural inhibition of conducted vasodilatation along hamster feed arteries: complementary effects of alpha1- and alpha2-adrenoreceptor activation. J Physiol 563: 541–555, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hermsmeyer RK, Thompson TL. Vasodilator coordination via membrane conduction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 293: H1320–H1321, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hill CE, Hickey H, Sandow SL. Role of gap junctions in acetylcholine-induced vasodilation of proximal and distal arteries of the rat mesentery. J Auton Nerv Syst 81: 122–127, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hirst GD, Neild TO. An analysis of excitatory junctional potentials recorded from arterioles. J Physiol 280: 87–104, 1978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jacobsen JC, Aalkjaer C, Nilsson H, Matchkov VV, Freiberg J, Holstein-Rathlou NH. A model of smooth muscle cell synchronization in the arterial wall. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 293: H229–H237, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kapela A, Bezerianos A, Tsoukias NM. A mathematical model of Ca2+ dynamics in rat mesenteric smooth muscle cell: agonist and NO stimulation. J Theor Biol 253: 238–260, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kapela A, Bezerianos A, Tsoukias NM. A mathematical model of vasoreactivity in rat mesenteric arterioles: I. Myoendothelial communication. Microcirculation 4: 1–20, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kapela A, Silva H, Bezerianos A, Tsoukias N. Mathematical model of endothelium-smooth muscle interaction in regulating microcirculatory tone (Abstract). FASEB J 20: A283, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 31. Keener JP, Sneyd J. Mathematical Physiology. New York: Springer, 1998, p. viii, 766 [Google Scholar]

- 32. Koenigsberger M, Sauser R, Beny JL, Meister JJ. Role of the endothelium on arterial vasomotion. Biophys J 88: 3845–3854, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Krogh A, Harrop GA, Rehberg PB. Studies on the physiology of capillaries. III. The innervation of the blood vessels in the hind legs of the frog. J Physiol 56: 179–189, 1922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lidington D, Ouellette Y, Tyml K. Endotoxin increases intercellular resistance in microvascular endothelial cells by a tyrosine kinase pathway. J Cell Physiol 185: 117–125, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Luckhoff A, Busse R. Calcium influx into endothelial cells and formation of endothelium-derived relaxing factor is controlled by the membrane potential. Pflügers Arch 416: 305–311, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mizuno O, Kobayashi S, Hirano K, Nishimura J, Kubo C, Kanaide H. Stimulus-specific alteration of the relationship between cytosolic Ca(2+) transients and nitric oxide production in endothelial cells ex vivo. Br J Pharmacol 130: 1140–1146, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nilius B, Viana F, Droogmans G. Ion channels in vascular endothelium. Annu Rev Physiol 59: 145–170, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pries AR, Secomb TW, Gaehtgens P. Structural adaptation and stability of microvascular networks: theory and simulations. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 275: H349–H360, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sanderson MJ, Charles AC, Boitano S, Dirksen ER. Mechanisms and function of intercellular calcium signaling. Mol Cell Endocrinol 98: 173–187, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sandow SL, Hill CE. Incidence of myoendothelial gap junctions in the proximal and distal mesenteric arteries of the rat is suggestive of a role in endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor-mediated responses. Circ Res 86: 341–346, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Segal SS. Microvascular recruitment in hamster striated muscle: role for conducted vasodilation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 261: H181–H189, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Segal SS. Regulation of blood flow in the microcirculation. Microcirculation 12: 33–45, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Segal SS, Welsh DG, Kurjiaka DT. Spread of vasodilatation and vasoconstriction along feed arteries and arterioles of hamster skeletal muscle. J Physiol 516: 283–291, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Silva HS, Kapela A, Tsoukias NM. A mathematical model of plasma membrane electrophysiology and calcium dynamics in vascular endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 293: C277–C293, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sneyd J, Charles AC, Sanderson MJ. A model for the propagation of intercellular calcium waves. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 266: C293–C302, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Takano H, Dora KA, Garland CJ. Spreading vasodilatation in resistance arteries. J Smooth Muscle Res 41: 303–311, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Takano H, Dora KA, Spitaler MM, Garland CJ. Spreading dilatation in rat mesenteric arteries associated with calcium-independent endothelial cell hyperpolarization. J Physiol 556: 887–903, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Tallini YN, Brekke JF, Shui B, Doran R, Hwang SM, Nakai J, Salama G, Segal SS, Kotlikoff MI. Propagated endothelial Ca2+ waves and arteriolar dilation in vivo: measurements in Cx40BAC GCaMP2 transgenic mice. Circ Res 101: 1300–1309, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Tsoukias NM, Popel AS. A model of nitric oxide capillary exchange. Microcirculation 10: 479–495, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Uhrenholt TR, Domeier TL, Segal SS. Propagation of calcium waves along endothelium of hamster feed arteries. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 292: H1634–H1640, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Welsh DG, Tran NN, Plane F, Sandow S. Are voltage-dependent ion channels involved in the endothelial cell control of vasomotor tone? Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 293: H2007, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Winter P, Dora KA. Spreading dilatation to luminal perfusion of ATP and UTP in rat isolated small mesenteric arteries. J Physiol 582: 335–347, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Wolfle SE, Schmidt VJ, Hoepfl B, Gebert A, Alcolea S, Gros D, de Wit C. Connexin45 cannot replace the function of connexin40 in conducting endothelium-dependent dilations along arterioles. Circ Res 101: 1292–1299, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]