Abstract

Prolonged ouabain administration (25 μg·kg−1·day−1 for 5 wk) induces “ouabain hypertension” (OH) in rats, but the molecular mechanisms by which ouabain elevates blood pressure are unknown. Here, we compared Ca2+ signaling in mesenteric artery smooth muscle cells (ASMCs) from normotensive (NT) and OH rats. Resting cytosolic free Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]cyt; measured with fura-2) and phenylephrine-induced Ca2+ transients were augmented in freshly dissociated OH ASMCs. Immunoblots revealed that the expression of the ouabain-sensitive α2-subunit of Na+ pumps, but not the predominant, ouabain-resistant α1-subunit, was increased (2.5-fold vs. NT ASMCs) as was Na+/Ca2+ exchanger-1 (NCX1; 6-fold vs. NT) in OH arteries. Ca2+ entry, activated by sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) Ca2+ store depletion with cyclopiazonic acid (SR Ca2+-ATPase inhibitor) or caffeine, was augmented in OH ASMCs. This reflected an augmented expression of 2.5-fold in OH ASMCs of C-type transient receptor potential TRPC1, an essential component of store-operated channels (SOCs); two other components of some SOCs were not expressed (TRPC4) or were not upregulated (TRPC5). Ba2+ entry activated by the diacylglycerol analog 1-oleoyl-2-acetyl-sn-glycerol [a measure of receptor-operated channel (ROC) activity] was much greater in OH than NT ASMCs. This correlated with a sixfold upregulation of TRPC6 protein, a ROC family member. Importantly, in primary cultured mesenteric ASMCs from normal rats, 72-h treatment with 100 nM ouabain significantly augmented NCX1 and TRPC6 protein expression and increased resting [Ca2+]cyt and ROC activity. SOC activity was also increased. Silencer RNA knockdown of NCX1 markedly downregulated TRPC6 and eliminated the ouabain-induced augmentation; silencer RNA knockdown of TRPC6 did not affect NCX1 expression but greatly attenuated its upregulation by ouabain. Clearly, NCX1 and TRPC6 expression are interrelated. Thus, prolonged ouabain treatment upregulates the Na+ pump α2-subunit-NCX1-TRPC6 (ROC) Ca2+ signaling pathway in arterial myocytes in vitro as well as in vivo. This may explain the augmented myogenic responses and enhanced phenylephrine-induced vasoconstriction in OH arteries (83) as well as the high blood pressure in OH rats.

Keywords: Na+ pumps, Na+/Ca2+ exchange, store-operated Ca2+ entry, receptor-operated Ca2+ entry, arterial myocytes

essential hypertension is an endemic, multifactorial disorder with an enormous impact on morbidity and mortality from cardiovascular and renal complications (40). The pathogenesis of essential hypertension is still poorly understood (14, 58), but the roles of excess dietary salt and NaCl retention are widely recognized (38, 54). A common feature of many animal models of hypertension is an elevated plasma level of endogenous ouabain (20, 29, 69), an adrenocortical hormone (29, 66). Plasma endogenous ouabain also is significantly elevated in ∼50% of patients with essential hypertension and is related to blood pressure (BP) even in the normal population (52, 65, 75). Also, short-term dietary salt loading increases plasma endogenous ouabain levels in humans (50). Moreover, in rodents, the prolonged administration of low doses of ouabain induces sustained BP elevation, termed “ouabain hypertension” (OH) (42, 51, 82).

Endogenous ouabain may play an important role in regulating arterial tone and peripheral vascular resistance (8, 11). Arterial smooth muscle cells (ASMCs) express Na+ pumps with an α1-subunit as well as Na+ pumps with a catalytic α2-subunit (18, 84). In rodents, α1-subunits of Na+ pumps have a very low affinity for ouabain (57). Thus, nanomolar ouabain exerts its vascular effects by preferentially inhibiting the high ouabain-affinity α2-subunit Na+ pumps, which are located in plasma membrane (PM) microdomains at PM-sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) junctions (35). The consequent rise in the local, sub-PM Na+ concentration should, via adjacent Na+/Ca2+ exchangers (NCXs) (37), raise the local cytosolic free Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]cyt) in the junctional space, increase SR Ca2+ stores, and augment ASMC Ca2+ signaling (3, 11).

Ca2+ homeostasis plays a crucial role in the genesis of vascular myogenic tone, and increases in [Ca2+]cyt appear to underlie at least part of the increased peripheral vascular resistance in hypertension (34, 70, 84). Accumulating evidence has indicated that Ca2+ influx through PM store-operated channels (SOCs) and receptor-operated channels (ROCs), along with voltage-gated Ca2+ channels, may play a role in regulating myogenic tone and vasoconstriction (23, 56, 71, 77). C-type transient receptor potential channel proteins TRPC1, TRPC4, and/or TRPC5, mammalian homologs of the Drosophila TRP channel, form the endogenous SOCs that are activated by SR Ca2+ depletion (5, 60, 79, 80). In contrast, TRPC3 and TRPC6, which are components of ROCs, can be activated by diacylglycerols in a store depletion-independent manner (31).

Two recently discovered families of transmembrane proteins, Orai1 [also known as Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ (CRAC) channel modulator] and stromal interacting molecule-1, may also contribute to SOC-mediated Ca2+ entry, mainly in nonexcitable cells (21, 64, 74). The proteins are, however, poorly expressed in native arterial myocytes, but are abundant in cultured ASMCs (6). Recent findings have suggested that Orai1 and stromal interacting molecule-1 are upregulated in aortas from stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats (22).

Interestingly, several groups have reported that Ca2+ homeostasis in ASMCs is influenced not only by direct Ca2+ entry through TRPC channels but also by Na+ entry through these nonselective cation channels. The entering Na+ apparently then also promotes Ca2+ entry through nearby NCX (2, 19, 62, 85).

In view of this profound influence of TRPC channels on ASMC function, it is hardly surprising that these channels have also been implicated in the pathogenesis of various forms of hypertension. For example, TRPC1 and TRPC6 are reportedly involved in hypoxic pulmonary hypertension (46, 76), and TRPC6 upregulation has been implicated in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension (46, 81). Also, in spontaneously hypertensive rats, TRPC3 is upregulated in the vasculature (47).

An important role for circulating ouabain in the pathogenesis of hypertension has now been substantiated (11, 52, 75). Nevertheless, the downstream consequences of ouabain's interaction with Na+ pumps, leading to the elevation of BP, are still not completely understood. Here, we explore the mechanisms that underlie altered Ca2+ homeostasis in mesenteric arteries from OH and control [normotensive (NT)] rats. Our data demonstrate that several key proteins in the pathway from ouabain to augmented Ca2+ signaling, namely, the α2-subunit of Na+ pumps, NCX type 1 (NCX1), TRPC1, and TRPC6, are all upregulated in OH rats. These results also provide further, direct verification of several critical elements in the specific pathway linking salt to hypertension, which was postulated more than three decades ago (8).

METHODS

Ethical approval.

All experiments were carried out according to the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Maryland School of Medicine.

Ouabain-induced hypertension in the rat.

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (130–150 g, Charles River Laboratories, Frederick, MD) were maintained in a temperature- and humidity-controlled room with a 12:12-h light-dark cycle. Rats had free access to tap water and were fed standard rat chow ad libitum. Body weight was measured weekly. After rats had acclimated to the facility and been conditioned to BP measurements, baseline data were obtained over several weeks. Under halothane anesthesia, NT male rats received a subcutaneous controlled time-release pellet (Innovative Research of America, Sarasota, FL) containing either ouabain (1.5 mg/pellet) or vehicle (control). The ouabain pellets were designed to release ∼25 μg ouabain/24 h for 60 days. Systolic and mean BPs were recorded weekly by tail-cuff plethysmography using a commercial photoelectric system (model 29 BP Meter/Amplifier, IITC, Woodland Hill, CA) and a device providing constant rates of cuff inflation and deflation. The average values for BP in each rat were obtained typically from five sequential cuff inflation-deflation cycles.

Dissection of arteries for immunoblot analysis.

The aorta and superior mesenteric artery from a euthanized rat were rapidly removed and placed in ice-cold physiological salt solution 1 (PSS1) of the following composition (in mM): 140 NaCl, 5.36 KCl, 0.34 Na2HPO4, 0.44 K2HPO4, 10 HEPES, 1.2 MgCl2, 1.8 mM CaCl2, and 10 d-glucose (pH 7.2). The arteries were cleaned of fat and connective tissue, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C before protein extraction. Mesenteric arteries or aortas from two to four rats were pooled and homogenized in lysis buffer.

Freshly dissociated ASMCs for Ca2+ imaging.

Myocytes were isolated from rat mesenteric arteries as previously described (6). The superior mesenteric artery was cleaned of fat and connective tissue and digested in low-Ca2+ (0.05 mM) PSS1 containing 2 mg/ml collagenase type XI, 0.16 mg/ml elastase type IV, and 2 mg/ml BSA (fat free) for 35 min at 37°C. After digestion, the tissue was washed three times with low-Ca2+ PSS1 at 4°C. A suspension of single cells was obtained by gently triturating the tissue with a fire-polished Pasteur pipette in low-Ca2+ PSS1. Smooth muscle cells were differentiated by their characteristic elongated morphology. Dispersed cells were directly deposited on glass coverslips for fluorescence microscopy. ASMCs on coverslips were stored at 4°C and used within 4 h. Cells were allowed to settle on the coverslips for 20–30 min before being loaded with fura-2. Freshly dissociated cells that were markedly contracted under resting conditions (<5%) were excluded. At the conclusion of the Ca2+ imaging experiments, the same cells were labeled for smooth muscle α-actin to identify ASMCs (26). In these experiments, nuclei also were identified by labeling for 5 min with a 50 μM solution of 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (24).

Primary cultured ASMCs for Ca2+ imaging and Western blot analysis.

The methods used for the isolation and culture of rat ASMCs have been previously published (26). Briefly, the superior mesenteric artery was isolated under sterile conditions from euthanized male 9- to 10-wk-old Sprague-Dawley rats as described above. The artery was incubated for ∼45 min at 37°C in Ca2+- and Mg2+-free HBSS containing 1 mg/ml collagenase type 2. After the incubation, the adventitia was carefully stripped, and the endothelium was removed (26). ASMCs in the remaining smooth muscle were dissociated by digestion for 35–40 min at 37°C in HBSS containing 1 mg/ml collagenase type 2 and 0.5 mg/ml elastase type IV. Dissociated cells were resuspended and plated on either 25-mm coverslips for use in fluorescent microscopy experiments or on 10-cm culture dishes for Western blot analysis. Plated cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS under a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2-95% air at 37°C. The medium was changed on days 4 and 7. Experiments were performed on subconfluent cultures on days 7 and 8 in vitro if not indicated otherwise. The purity of ASMC cultures was verified by positive staining with smooth muscle-specific α-actin (24, 26). Most of the cells (>99.5%) were α-actin positive. The cells also did not cross react with fibroblast (CD90/Thy-1)-specific and endothelium (factor VIII, von Willebrand)-specific antigens (26).

Ca2+ imaging.

[Ca2+]cyt was measured with fura-2 using digital imaging (6). Primary cultured ASMCs were loaded with fura-2 by an incubation for 35 min in culture medium containing 3.3 μM fura-2 AM (20–22°C, 5% CO2-95% O2). After the dye loading, coverslips were transferred to a tissue chamber mounted on a microscope stage, where the cells were superfused for 15–20 min (35–36°C) with physiological salt solution 2 (PSS2) to wash away the extracellular dye. PSS2 contained (in mM) 140 NaCl, 5.9 KCl, 1.2 NaH2PO4, 5 NaHCO3, 1.4 MgCl2, 1.8 CaCl2, 11.5 glucose, and 10 HEPES (pH 7.4). Cells were studied for 40–60 min during continuous superfusion with PSS2 (35°C).

The imaging system included a Zeiss Axiovert 100 microscope (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY). Dye-loaded cells were illuminated with a diffraction grating-based system (Polychrome V, TILL Photonics). Fluorescent images were recorded with a CoolSnap HQ2 charge-coupled device camera (Photometrics, Tucson, AZ). Image acquisition and analysis were performed with a MetaFluor/MetaMorph Imaging System (Molecular Devices, Downingtown, PA). [Ca2+]cyt was calculated by determining the ratio of fura-2 fluorescent emission (510 nm) excited at 380 and 360 nm, as previously described (6, 24). Intracellular fura-2 was calibrated in situ in freshly dissociated and primary cultured ASMCs (6). Intracellular Ba2+ measurements are shown as fura-2 340-to-380-nm excitation ratios with fluorescent emission at 510 nm (6).

Immunoblot analysis.

Membrane proteins were solubilized in SDS buffer containing 5% 2-mercaptoethanol and were separated by SDS-PAGE as previously described (6). The following antibodies were used: rabbit polyclonal anti-TRPC1, anti-TRPC3, anti-TRPC4, anti-TRPC5, and anti-TRPC6 (Allomone Laboratories, Jerusalem, Israel); mouse monoclonal anti-NCX1 (R3F1, Swant, Bellinzona, Switzerland); rabbit polyclonal anti-Na+ pump α1-subunit isoform (gift of Dr. Thomas Pressley); and rabbit polyclonal anti-Na+ pump α2-subunit isoform (Millipore, Billerica, MA). Gel loading was controlled with polyclonal or monoclonal anti-β-actin antibodies (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). After being washed, membranes were incubated with anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase-conjugated IgG for 1 h at room temperature. The immune complexes on the membranes were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence plus (Amersham BioSciences, Piscattaway, NJ) and exposure to X-ray film (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY). Quantitative analysis of immunoblots was performed using a Kodak DC120 digital camera and 1D Image Analysis Software (Eastman Kodak).

Protein knockdown by short interfering RNA.

Primary cultured ASMCs were transfected with silencer (si)RNA ON-Target plus Smart pool (20 μM) designed against NCX1, TRPC6, or siCONTRL (Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO). The sequences of the TRPC6/siRNA duplexes were as follows: 5′-UUGUGUGCCAGCUGAUUUCUU-3′, 5′-UAAACAUGUAUGCUGGUCCUU-3′, 5′-AAUCCGUACAUAACCUUUAUU-3′, and 5′-AAUGGCGACAGCGAGGACCUU-3′; the sequences of the NCX1/siRNA duplexes were as follows: 5′-CCGAUUCCCUCUACCGUAA-3′, 5′-CAAUAUCAGUCAAGGUAAU-3′, 5′-GGAGAGAGCAGUUCAUUGAU-3′, and 5′-GAAUGUACUGGCUCAUAUU-3′. Twenty-four hours before treatment, ASMCs were placed in the culture medium without antibiotics and further transfected with siRNA using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent in Opti-MEM (Invitrogen). After 24 h of incubation, the medium was aspirated and replaced with DMEM (10% FBS) without siRNA for 48 h before Western blot analysis was performed.

Materials.

FBS was obtained from Atlanta Biologicals (Lawrenceville, GA). All other tissue culture reagents were obtained from GIBCO-BRL (Grand Island, NY). Fura-2 AM and 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole were obtained from Molecular Probes (Invitrogen Detection Technologies, Eugene, OR). 1-Oleoyl-2-acetyl-sn-glycerol (OAG) was purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA). Collagenase type 2 was obtained from Worthington Biochemical (Freehold, NJ). Cyclopiazonic acid (CPA), caffeine (CAF), DMSO, β-actin, smooth muscle α-actin, collagenase type XI, elastase type IV, BSA, nifedipine, ionomycin, penicillin G, and streptomycin were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. All other reagents were analytic grade or the highest purity available.

Statistical analysis.

The numerical data presented in the results are means ± SE from n single cells (one value per cell). Immunoblots were repeated at least four to six times for each protein. The number of animals is presented where appropriate. Data from 6 to 18 rats were obtained for most protocols. Data from five to six transfections were obtained for siRNA protocols. Statistical significance was determined using Student's paired or unpaired t-tests or two-way ANOVA as appropriate. P values of <0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Ca2+ homeostasis in freshly dissociated ASMCs from OH rats.

Sustained hypertension in rats was induced by prolonged in vivo ouabain treatment (Fig. 1A). Baseline BPs were stable in rats over 4 wk of observation. At week 4, all rats received a slow-release implant containing either ouabain or vehicle (control). By week 6 (i.e., 2 wk after the implant), systolic BP increased in the ouabain-implanted (OH) group and remained elevated until death at week 9 (147 ± 3 mmHg in the OH group vs. 118 ± 3 mmHg in NT group, P < 0.05).

Fig. 1.

Ca2+ homeostasis in freshly dissociated mesenteric artery smooth muscle cells (ASMCs) from normotensive (NT) and ouabain-induced hypertensive (OH) rats. A: development of OH in a representative group of rats. NT male rats received a pellet containing either ouabain (n = 7 rats) or vehicle (control; n = 8 rats) at the beginning of week 4 (horizontal bar). OH = P < 0.01 vs. vehicle-treated rats (ANOVA). B: phenylephrine (PE)-induced Ca2+ transients in ASMCs from NT and OH rats. Representative records show the time course of cytosolic free Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]cyt) changes induced by 1 μM PE. C: summarized resting [Ca2+]cyt levels (181 NT cells and 198 OH cells) and peak PE-induced Ca2+ transients (56 NT cells and 49 OH cells) in ASMCs from 7 OH and 8 NT rats. ***P < 0.001 vs. ASMCs from NT rats. D: representative fura-2 fluorescent images (a and a′) and pseudocolor Ca2+ images showing resting [Ca2+]cyt (b and b′) in freshly dissociated ASMCs from NT (a and b) and OH (a′ and b′) rats. Data in B were recorded from the circled cells in a and a′. F360, fluorescence at 360-nm excitation.

Freshly dissociated OH rat mesenteric artery myocytes had significantly higher resting [Ca2+]cyt than did NT myocytes (112 ± 2 vs. 95 ± 3 nM, P < 0.001; Fig. 1, B–D). Furthermore, activation by 1 μM phenylephrine, in physiological media, induced augmented Ca2+ signals in OH rat ASMCs. Both the peak initial response, believed to be the result of inositol (1,4,5)-trisphosphate-mediated SR Ca2+ release, and the later, more sustained Ca2+ signal, perhaps mediated by Ca2+ entry through ROCs and/or SOCs (59), were greater in OH than NT rat ASMCs (Fig. 1, B–D). In subsequent experiments, we investigated the possible mechanisms that contributed to this altered Ca2+ homeostasis and augmented signaling.

Na+ pumps and Na+/Ca2+ exchangers in OH rat artery smooth muscle.

Previously published evidence has suggested that Na+ pumps α2-subunits and NCX1 mediate the effects of low-dose ouabain on smooth muscle Ca2+ signaling and vasoconstriction (18, 84). But what happens to these transporters under the influence of chronic in vivo ouabain administration? As shown in Fig. 2, A and B, the response to tonic low-dose ouabain, which inhibits arterial Na+ pump α2-subunits with an apparent half-maximal effect (EC50) at 660 pM (83), is a large increase in the expression of the target Na+ pump α2-subunits: to ∼250% of the level in NT mesenteric arteries. In contrast, the expression of Na+ pump α1-subunits, which constitute ∼80% of the total Na+ pump population in ASMCs (18, 84) and which have very low affinity for ouabain (57), was not altered in OH arteries (Fig. 2, C and D).

Fig. 2.

Expression of Na+ pump α1- and α2-subunit isoforms and Na+/Ca2+ exchanger type 1 (NCX1) in arterial myocytes from NT and OH rats. A–H: Western blot analysis of Na+ pump α2-subunits (A and B), Na+ pump α1-subunits (C and D), and NCX1 (E–H) protein expression in smooth muscle cell membranes from mesenteric arteries (A–F) and aortas (G and H) of NT and OH rats. A, C, E, and G: representative blots. All lanes were loaded with 30 μg membrane protein. Summarized data (B, D, F, and H) were normalized to the amount of β-actin and are expressed as means ± SE from 5 (B), 7 (D), 4 (F), and 5 (H) immunoblots (total of 22 rats). ***P < 0.001 vs. NT ASMCs.

NCX1, presumably the next protein in the ouabain-Na+ pump α2-subunit-Ca2+ signaling pathway (11), is, like the α2-subunit, markedly upregulated (by ∼5- to 6-fold) in the OH rat mesenteric artery and aorta (Fig. 2, E–H). Upregulation of the α2-subunit would be expected to counteract the inhibitory effect of ouabain on Na+ pump α2-subunits and reduce the buildup of the Na+ concentration in the tiny spaces between the plasma membrance and junctional SR (3). Nevertheless, because NCX1 normally mediates Ca2+ entry, rather than exit, in ASMCs of arteries with tone (34), upregulation of this transporter should tend to accelerate Ca2+ entry and promote net Ca2+ gain.

SR Ca2+ stores and SOC-mediated Ca2+ entry in OH rat artery smooth muscle.

If Ca2+ entry is increased and [Ca2+]cyt is elevated in OH rat ASMCs, it is logical to ask whether ASMC SR Ca2+ stores are also increased. To address this question, Ca2+ transients were evoked by unloading the SR Ca2+ stores with either 10 mM CAF (which opens SR ryanodine-sensitive Ca2+ channels) or 10 μM CPA [which inhibits sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA)] (27). Ca2+-free media were used to avoid complications from Ca2+ entry. While the CPA-evoked Ca2+ transients were only marginally (and not significantly) increased in OH arterial myocytes (Fig. 3, A and B), CAF-evoked transients were double the amplitude of those in NT artery myocytes (Fig. 3, C and D). This difference between CPA- and CAF-evoked responses is not surprising in view of our evidence that 1) rat mesenteric artery myocytes possess two functionally distinct types of SR Ca2+ stores (6) and 2) the CPA-sensitive store is quite small in freshly dissociated ASMCs (6).

Fig. 3.

Cyclopiazonic acid (CPA)- and caffeine (CAF)-induced Ca2+ transients, store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE), and transient receptor potential protein TRPC1/4/5 expression in freshly dissociated myocytes from NT and OH rats. A–D: CPA-evoked (A and B) and CAF-evoked (C and D) Ca2+ transients (“Ca2+ release”) and subsequent SOCE in mesenteric artery myocytes. A and C: representative original [Ca2+]cyt data. CPA (10 μM) and CAF (10 mM) were applied in Ca2+-free (where indicated) and Ca2+-containing solutions. Nifedipine (10 μM) was added 10 min before the recordings shown and was maintained throughout the experiment. B and D: summarized data showing CPA- or CAF-induced transient Ca2+ peaks in the absence of extracellular Ca2+ and the secondary rise in [Ca2+]cyt when Ca2+ was added back (SOCE). Data in B are from 86 NT and 82 OH myocytes from a total of 12 rats; data in D are from 93 NT and 118 OH myocytes from a total of 10 rats. E–J: Western blot analysis of TRPC1 (E and F), TRPC5 (G and H), and TRPC4 (I and J) protein expression (30 μg protein/lane) in ASMCs from NT and OH rats. E, G, and I: representative immunoblots. TRPC1 and TRPC5 data are from mesenteric arteries; TRPC4 data are from the aorta because mesenteric arteries do not express this protein. Summarized data from 8 (F), 4 (H), and 4 (J) Western blots (total of 16 rats) were normalized to the amount of β-actin. All bars indicate means ± SE. *P < 0.05 and ***P < 0.001 vs. NT ASMCs.

The Ca2+ transients evoked by restoration of external Ca2+ are often used to detect the activity of SOCs, which apparently play an important role in SR store refilling (60). In both CAF- and CPA-treated cells, these Ca2+ transients, a manifestation of store-operated Ca2+ entry, were significantly greater in OH than NT myocytes (Fig. 3, A–D). The implication is that SOC activity is augmented in OH myocytes. Whether this was simply due to increased entry through an unchanged number of channels or to an increase in the number of channels available was tested by immunoblot analysis. The results revealed that TRPC1 expression in OH mesenteric arteries was 2.8-fold that in NT arteries (Fig. 3, E and F). In contrast, the expression of TRPC5, also a component of SOCs, was unaltered (Fig. 3, G and H). TRPC4, a protein component of SOCs in other cell types, is not expressed in rat mesenteric arteries (6). TRPC4 is, however, expressed in the rat aorta, but its expression level was unaltered in OH rats (Fig. 3, I and J).

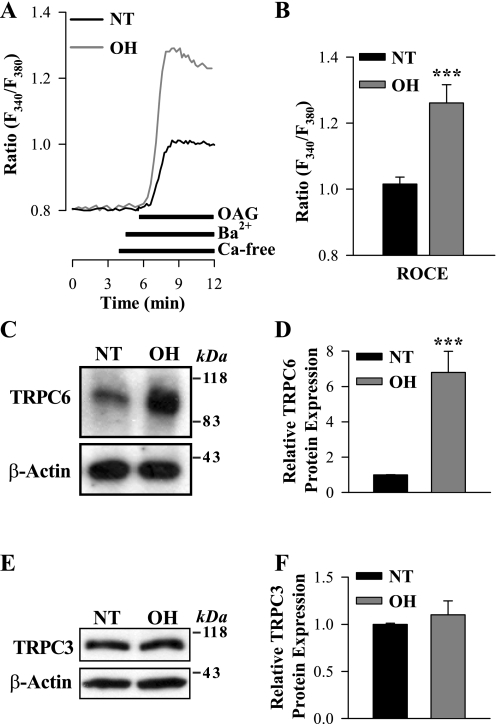

ROCs and ROC-mediated Ca2+ entry in OH rat artery smooth muscle.

To determine whether ROC-mediated Ca2+ entry also is increased in mesenteric ASMCs from OH rats, freshly dissociated myocytes were stimulated with the cell-permeable diacylglycerol analog OAG. OAG opens TRPC3 and TRPC6 channels in a PKC-independent manner (31). SOCs have high Ca2+ selectivity and, unlike ROCs, are virtually impermeable to other alkaline-earth cations, such as Ba2+ (73). Therefore, to distinguish ROCs from SOCs, we measured Ba2+ entry. Ba2+ is not transported by SERCA or PM Ca2+ pumps (44). In the presence of extracellular Ba2+, 80 μM OAG induced significantly larger elevations of cytosolic Ba2+ (fura-2 340-to-380-nm ratio; see methods) in myocytes from OH rats than in those from NT rats (Fig. 4, A and B). This evidence of greatly increased ROC-mediated Ca2+ entry correlated with more than sixfold augmentation of the expression of TRPC6 (Fig. 4, C and D), an obligatory component of endogenous ROCs in a variety of cell types, including vascular myocytes (31, 33). The expression of TRPC3, which also belongs to the TRPC3/6/7 subfamily of diacylglycerol-activated ROCs, however, was not significantly affected in ASMCs from OH rats (Fig. 4, E and F); mRNA for TRPC7 was not detected in rat mesenteric artery smooth muscle (30) and, therefore, was not studied.

Fig. 4.

1-Oleoyl-2-acetyl-sn-glycerol (OAG)-induced [receptor-operated channel (ROC)-mediated] Ba2+ entry and TRPC3/6 protein expression in freshly dissociated ASMCs from NT and OH rats. A: representative records showing the time course of the fura-2 fluorescence ratio [fluorescence at 340-to-380-nm excitation (F340/F380)] signals induced by 80 μM OAG in freshly dissociated ASMCs from NT and OH rats. Extracellular Ca2+ was replaced by 1 mM Ba2+ during the period indicated on the graph. Nifedipine (10 μM) was applied 10 min before the trace shown and was maintained throughout the experiment. B: summarized data showing the OAG-induced, ROC-mediated Ba2+ entry [ROC-mediated Ca2+ entry (ROCE)] in 78 NT and 91 OH rat mesenteric ASMCs. Each bar corresponds to data from 8 rats. C–F: Western blot analysis of TRPC6 and TRPC3 expression in ASMCs from NT and OH rats. C and E: representative immunoblots (15 μg protein/lane). Summarized data from 9 (D) and 10 (F) immunoblots (total of 18 rats) were normalized to β-actin. ***P < 0.001 vs. NT ASMCs.

In vitro replication of the actions of in vivo ouabain in primary cultured ASMCs.

The aforementioned effects of in vivo ouabain administration on NCX1, SOCs, and ROCs in arterial myocytes might be the direct result of ouabain's interaction with Na+ pump α2-subunits or, alternatively perhaps, the consequence of the elevated BP or some other in vivo factor(s). To explore this issue, we tested the effects of prolonged treatment with nanomolar ouabain on primary cultured ASMCs from NT rats. Indeed, after a 72-h exposure to 100 nM ouabain, NCX1 expression in ASMCs was threefold higher than in untreated cells (Fig. 5, A and B).

Fig. 5.

Effect of 100 nM ouabain on NCX1 and TRPC1 expression, resting [Ca2+]cyt, and SOCE in cultured normal ASMCs. A and B: Western blot analysis of NCX1 expression in control (untreated) myocytes and ASMCs treated with 100 nM ouabain for 72 h. B: summarized data (19 immunoblots) were normalized to the amount of β-actin. C: representative records showing the time course of changes in [Ca2+]cyt in control and ouabain-treated ASMCs when 10 μM CPA was applied in Ca2+-free and Ca2+-containing solutions. Nifedipine (10 μM) was added 10 min before the records shown and was maintained throughout the experiment. D: summarized data showing resting [Ca2+]cyt and the CPA-induced transient Ca2+ peak in the absence of extracellular Ca2+ and the secondary rise in [Ca2+]cyt when Ca2+ was added back (SOCE) in control myocytes and ASMCs treated with 100 nM ouabain for 72 h. Resting [Ca2+]cyt data are from 36 control myocytes and 54 ouabain-treated ASMCs. SOCE was studied in 83 control myocytes and 61 ouabain-treated ASMCs. E and F: Western blot analysis of TRPC1 expression in control (untreated) myocytes and ASMCs treated with 100 nM ouabain for 72 h. F: summarized data from 6 immunoblots were normalized to the amount of β-actin. *P < 0.05 and ***P < 0.001 vs. control ASMCs.

In vitro exposure of cultured NT rat mesenteric ASMCs to 100 nM ouabain for 72 h modestly, but significantly, elevated resting [Ca2+]cyt and augmented the SOC-mediated Ca2+ entry evoked by depleting SR Ca2+ stores with CPA (Fig. 5, C and D). This was associated with a small, but not significant, increased in TRPC1 expression (Fig. 5, E and F). Neither TRPC4 nor TRPC5 expression was affected by the ouabain treatment (not shown).

Under these same conditions, however, ouabain greatly augmented OAG-activated ROC-mediated Ca2+ entry in the cultured myocytes. In fact, 10 nM ouabain had an effect equal to that of 100 nM ouabain (Fig. 6, A–C), as expected, because the EC50 for ouabain is ∼0.66 nM (83). This increase in ROC-mediated Ca2+ entry correlated with a large, time-dependent increase in TRPC6 expression, so that the TRPC6 level nearly doubled by 72 h (Fig. 6, D and E).

Fig. 6.

OAG-induced (ROC-mediated) Ba2+ entry and TRPC6 protein expression in cultured ouabain-treated ASMCs. A and B: representative records showing the time course of the fura-2 fluorescence ratio (F340/F380) signal induced by 80 μM OAG in control myocytes and ASMCs treated with 10 (A) or 100 nM (B) ouabain. Extracellular Ca2+ was replaced by 1 mM Ba2+ during the period indicated on the graph. Nifedipine (10 μM) was applied 10 min before the trace shown and was maintained throughout the experiment. C: summarized data showing the OAG-induced, ROC-mediated Ba2+ entry (ROCE) in control myocytes (n = 124) and in ASMCs treated with 10 (n = 58) or 100 nM (n = 80) ouabain for 72 h. D: Western blot analysis of TRPC6 expression in control (untreated) myocytes and ASMCs treated with 100 nM ouabain for 48 or 72 h. E: summarized data from 19 immunoblots were normalized to the amount of β-actin. *P < 0.05 and ***P < 0.001 vs. control.

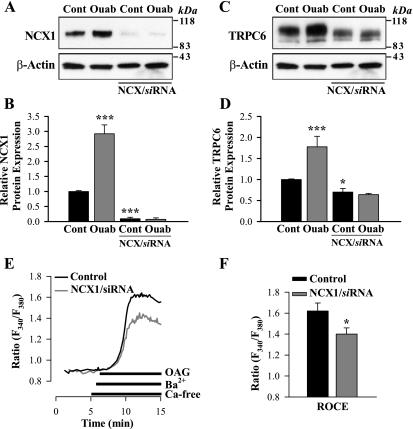

Are NCX1 expression and TRPC6 expression interrelated?

The preceding section demonstrates that many of the effects of in vivo ouabain administration on arterial smooth muscle can be mimicked in vitro, in cultured cells. This may enable us to elucidate the possible underlying mechanisms. As a first step, siRNA transfection methods were used to determine whether suppression of either NCX1 or TRPC6 affected the expression of the other protein. As anticipated, NCX1 siRNA markedly downregulated NCX1 expression and abolished the effect of 100 nM ouabain on NCX1 expression (Fig. 7, A and B). But NCX1 siRNA also significantly reduced TRPC6 expression (by ∼25%) and abolished its augmentation by ouabain (Fig. 7, C and D) but did not affect α2-subunit expression (not shown). ROC-mediated Ba2+ entry was significantly decreased under these conditions (Fig. 7, E and F).

Fig. 7.

Effects of NCX1/silencer (si)RNA and ouabain on NCX1 and TRPC6 expression and OAG-induced (ROC-mediated) Ba2+ entry in cultured ASMCs. A–D: Western blot analysis of NCX1 (A and B) and TRPC6 (C and D) expression in control (untreated) ASMCs and cells treated with 100 nM ouabain for 72 h under control conditions and after 77 h of treatment with NCX1/siRNA. B and D: summarized data from 9 (B) and 14 (D) immunoblots. E: representative records showing the time course of the fura-2 fluorescence ratio (F340/F380) signal induced by 80 μM OAG in a control ASMC and a cell treated with NCX1/siRNA. Extracellular Ca2+ was replaced by 1 mM Ba2+ during the period indicated on the graph. Nifedipine (10 μM) was applied 10 min before the trace shown and was maintained throughout the experiment. F: summarized data showing the OAG-induced, ROC-mediated Ba2+ entry (ROCE) in 42 control myocytes and in 38 cells treated with NCX1/siRNA. *P < 0.05 and ***P < 0.001 vs. control (untreated) cells.

When TRPC6 expression was knocked down by TRPC6 siRNA in cultured ASMCs (Fig. 8, A and B), ROCE (i.e., ROC-mediated Ba2+ entry) was, of course, also greatly reduced (Fig. 8, C and D). Indeed, the OAG-induced increase in the fura-2 fluorescence ratio, indicative of Ba2+ entry through ROCs, declined by ∼90% (Fig. 8C). Furthermore, although NCX1 expression in the absence of ouabain was unaffected, the ouabain-induced increase in NCX1 expression was markedly suppressed by TRPC6 siRNA (Fig. 8, E and F). This raises the possibility that either TRPC6 expression, per se, or the resulting increase in resting [Ca2+]cyt and/or ROC-mediated Ca2+ entry is required to enable ouabain to augment NCX1 expression.

Fig. 8.

Effects of TRPC6/siRNA on TRPC6 and NCX1 expression and OAG-induced (ROC-mediated) Ba2+ entry in cultured ASMCs. A and B: Western blot analysis of TRPC6 expression in control (untreated) ASMCs and cells treated with 100 nM ouabain for 72 h under control conditions and after 77 h of treatment with TRPC6/siRNA. B: summarized data from 11 immunoblots were normalized to β-actin. C: representative records showing the time course of the fura-2 fluorescence ratio (F340/F380) signal induced by 80 μM OAG in a control ASMC and a cell treated with TRPC6/siRNA. Extracellular Ca2+ was replaced by 1 mM Ba2+ during the period indicated on the graph. Nifedipine (10 μM) was applied 10 min before the trace shown and was maintained throughout the experiment. D: summarized data showing the OAG-induced, ROC-mediated Ba2+ entry (ROCE) in 48 control myocytes and in 45 cells treated with TRPC6/siRNA. E and F: Western blot analysis showing NCX1 expression in control (untreated) ASMCs and cells treated with 100 nM ouabain for 72 h under control conditions and after 77 h of treatment with TRPC6/siRNA. F: summarized data from 7 immunoblots were normalized to β-actin. ***P < 0.001 vs. control.

Selective inhibition of TRPC6 also did not affect Na+ pump α2-subunit expression (not shown).

DISCUSSION

The results described in this report show the effects of ouabain in vivo and in vitro on the expression of membrane proteins that affect arterial myocyte Na+ and Ca2+ metabolism. The results, taken together, provide strong experimental support for the proposed sequence of steps leading from prolonged ouabain administration to augmented Ca2+ signaling, as shown in Fig. 9, and, therefore, to augmented vascular contractile responses. This complements evidence for the early steps obtained from molecular engineering studies in mice (summarized in Ref. 11).

Fig. 9.

Diagram of the pathway linking ouabain with Na+ pump α2-subunits, NCX1, TRPC1, and TRPC6 expression, upregulation of [Ca2+]cyt and Ca2+ signaling, and their likely effects on vascular tone and blood pressure. Several known interactions, including those elucidated in this report, are indicated by solid arrows (outside the boxes). Links that have not been clarified and that require further investigation are indicated by dashed arrows. To focus on this proposed pathway, a variety of feedback regulatory mechanisms have been omitted. [Na+]cyt, cytosolic free Na+ concentration.

Na+ pump α2-subunits and NCX1 are upregulated in OH rat arterial myocytes.

The first step is the direct interaction between ouabain and the ASMC high-ouabain affinity Na+ pump α2-subunits. Nanomolar ouabain inhibits Na+ pump α2-subunits with an EC50 of 0.5–1 nM (83, 84), but such low concentrations have no effect on the other Na+ pumps (α1-subunits) present in rat arterial myocytes [EC50 > 10 μM (57)]. Thus, it is not surprising that the myocytes respond by selectively upregulating Na+ pump α2-subunits (Fig. 2, A and B) to try to compensate for the ouabain-induced reduction in pump activity. This parallels a recent report (78) showing that the chronic inhibition of NCX in cardiac myocytes induces a compensatory upregulation of NCX1 in those cells.

The data from the OH rat myocytes demonstrate that the Na+ pump α2-subunits are the specific target of the circulating ouabain [in humans, the range of plasma levels is between ∼0.1 and 1 nM (50)]. These results complement studies on mice which show that the high-ouabain affinity binding site on the Na+ pump α2-subunit is essential for ouabain-induced and ACTH-induced forms of hypertension (17, 18, 48).

In arterial myocytes, Na+ pump α2-subunits colocalize with NCX1 in PM microdomains at PM-SR junctions (35, 67, 68). Inhibition of Na+ pump α2-subunits would therefore be expected to increase the cytosolic free Na+ concentration in the local sub-PM spaces and reduce the Na+ electrochemical gradient, thereby driving Ca2+ into the cells via NCX1. Indeed, the expression of these exchangers is also markedly elevated in OH rat ASMCs (Fig. 2, E–H), although the mechanism(s) by which this occurs is(are) not yet understood. Nevertheless, it is noteworthy that this simultaneous upregulation of Na+ pump α2-subunits and NCX1 in ASMCs differs strikingly from observations in hypertensive hearts. In both renovascular hypertension (49) and mineralocorticoid-salt hypertension (63), Na+ pump α2-subunits are upregulated but NCX1 is downregulated in cardiac myocytes. Whether or how this difference between cardiac and vascular smooth muscles in the hypertensive models might relate to the apparently different roles of NCX1 in the heart [primarily mediates Ca2+ extrusion (7, 15)] and in ASMCs [primarily mediates Ca2+ entry (34, 41)] is not clear.

It is noteworthy that mineralocorticoid hypertension in rats and humans is associated with elevated plasma endogenous ouabain (29, 43, 65). This begs the following question: “Is the pathway shown in Fig. 9 upregulated in the arteries of humans and animals with mineralocorticoid-salt hypertension?” Available evidence (cited in the next section) has indicated that the answer may be affirmative in rodent models.

Ca2+ homeostasis is altered in OH rat arterial myocytes.

Arterial contractility is augmented in many forms of hypertension, including OH. Some of the functional changes have been attributed to vascular structural remodeling and artery narrowing (53, 55) and increased arterial stiffness (13). Nevertheless, substantial evidence has also pointed to dynamic increases in contraction that may be associated directly with Ca2+ dysregulation, such as enhanced responses to stretch and to vasoconstrictors (12, 83).

Based on this evidence for arterial functional change, we studied Ca2+ homeostasis in OH rat artery myocytes. Indeed, freshly dissociated myocytes exhibit Ca2+ dysregulation: elevated resting [Ca2+]cyt and augmented CAF-releasable Ca2+ stores and phenylephrine-evoked Ca2+ signals (Figs. 1, B–D, and 3, C and D). The myocytes also exhibited increased SOC- and ROC-mediated Ca2+ entry (Figs. 3, A–D, and 4, A and B). Immunoblots indicated that the latter effects are a consequence of upregulated TRPC1 and TRPC6 expression, respectively (Figs. 3, E and F, and 4, C and D). The upregulated TRPC6 and increased ROC-mediated Ca2+ entry are, in fact, reflected by the augmented phenylephrine-evoked vasoconstriction of intact OH rat arteries, especially at high phenylephrine concentrations (83), where the role of ROCs is more prominent (59). The increased basal [Ca2+]cyt, as well as the increased TRPC6 (16, 32, 77), may contribute to the augmented myogenic reactivity of OH rat arteries (83). Indeed, mineralocorticoid-salt hypertension (4), in which endogenous ouabain has been implicated (29, 43), and human idiopathic pulmonary hypertension (81) are associated with upregulation of TRPC6. Thus, the biochemistry and physiology appear to be directly linked. In other words, upregulation of the pathway shown in Fig. 9 may provide a molecular explanation for the observed augmentation of vascular contractile responses in hypertension (12, 83). This concept is underscored by the evidence that, in human primary pulmonary hypertension as well, NCX1 (85) and TRPC6 (81) are both upregulated.

A noteworthy aspect of this comparison between arterial function and these molecular underpinnings is the relatively modest alterations in the function of small arteries (83) from some of the same OH rats that were used for the cellular and biochemical studies described above. Here, we report a relatively robust enhancement of NCX1, TRPC6, and even TRPC1 expression. This contrasts with the seemingly modest augmentation of myogenic reactivity and phenylephrine-evoked responses and the apparently insignificant augmentation (perhaps due to the low number of arteries studied) of contractions evoked by the release of SR Ca2+ stores in intact small arteries (83). How can these ostensibly disparate observations be reconciled? The answer likely lies in the fact that, in intact arteries, numerous other factors also influence the [Ca2+]cyt level and contractility. Nevertheless, consideration of Poiseuille's equation (45) reminds us that even a modest 5% augmentation of constriction in a 100-μm-diameter artery will increase the resistance to flow by >20%–a large effect when translated into total peripheral resistance and blood pressure.

Treatment of cultured ASMCs with nanomolar ouabain mimics observations on ASMCs from OH rats.

Another key observation made in this study is that, when primary cultured normal rat mesenteric ASMCs are exposed to low-dose ouabain, in vitro, they, too, upregulate components of the pathway shown in Fig. 9. Specifically, they increase NCX1 and TRPC6 expression and elevate resting [Ca2+]cyt. The TRPC6 overexpression is reflected, functionally, by the significantly augmented ROC-mediated Ba2+ entry, similar to observations in freshly dissociated OH rat arterial myocytes. Although TRPC1 was marginally, but not significantly, upregulated in the cultured cells, SOC-mediated Ca2+ entry did modestly increase (Fig. 5, C–F). These effects on cultured myocytes show that the downstream effects are triggered by ouabain itself and not by the increase in BP or by other circulating factors. It is noteworthy that, during cell culture, the expression of TRPC channels and SOC-mediated Ca2+ entry correlated with [Ca2+]cyt (24, 28). Therefore, the increased basal [Ca2+]cyt in ouabain-treated ASMCs may contribute to the upregulation of TRPCs. The effect of ouabain treatment was, however, specific only for TRPC6; other TRPC proteins were not changed under these conditions.

Importantly, this in vitro replication of the in vivo effects of ouabain presents the opportunity to explore the mechanisms that underlie these effects of ouabain on myocytes. Accordingly, to determine if the upregulated TRPC6 is a consequence of the augmented expression of NCX1, we tested the effect of NCX1/siRNA on TRPC6 expression. The results (Fig. 7) demonstrated that marked knockdown of NCX1 not only abolished the TRPC6 response to ouabain but even reduced basal TRPC6 expression by about one-third. Conversely, when TRPC6 expression was downregulated by TRPC6/siRNA, NCX1 expression was no longer influenced by ouabain (Fig. 8). These results imply a mutual interaction between NCX1 and TRPC6 and, thus, between the regulation of Ca2+ homeostasis by NCX1 and regulation of Ca2+ (and Na+) entry through ROCs, which are nonselective cation channels (1, 16, 33).

These considerations bear on the specific sequence of steps shown in Fig. 9. It seems clear that prolonged ouabain administration acting via Na+ pump α2-subunits initiates the upregulation of NCX1 and TRPC6 (and TRPC1). The siRNA data support the view that NCX1 lies upstream of TRPC6. The situation is complex because TRPC6 channels are relatively nonselective Ca2+-permeable channels and mediate substantial Na+ entry (1, 16, 62). The influx of Na+ might depolarize the cells and activate L-type Ca2+ channels in addition to promoting Ca2+ entry via NCX1 (2, 19, 62). This downstream role of NCX1 might explain why knockout of TRPC6 suppresses the effect of ouabain on NCX1 (Fig. 8).

The aforementioned effects should not be confused with the rapid (within seconds) increase in vascular tone induced by the short-term application of low-dose ouabain to arteries with myogenic tone (83, 84). The latter vasoconstrictor effect is apparently mediated by acute Na+ pump α2-subunit inhibition and the consequent rapid Na+ gradient-driven entry of Ca2+ via NCX. These acute effects clearly do not depend on the amplification of the Ca2+ signaling pathway through protein synthesis, which appears to be the response to prolonged Na+ pump α2-subunit inhibition.

Conclusions.

In summary, this report describes several novel observations on freshly dissociated myocytes from OH rat arteries and on the effects of low-dose ouabain on normal rat cultured arterial myocytes. These findings bear on the functional changes observed in isolated, intact OH rat arteries and, perhaps more generally, on the function of arteries in various types of hypertension. First, we showed that several molecular entities involved in Na+ and Ca2+ homeostasis and signaling (Na+ pump α2-subunits, NCX1, TRPC1, and TRPC6) are upregulated in OH rat mesenteric arteries. This is consistent with accumulating evidence linking high-ouabain affinity Na+ pumps, NCX1, SOCs, and ROCs to local control, at PM-SR junctions, of Na+ and Ca2+ homeostasis and Ca2+ signaling (3, 9, 10, 25, 36, 72).

Second, we found that the molecular sequence of events triggered by prolonged infusion of ouabain in vivo (Fig. 9) is mimicked by a 72-h exposure of ASMCs to ouabain in vitro. This makes it convenient to explore, with molecular tools, the specific mechanisms that underlie ouabain's augmentation of Ca2+ signaling. In the first such study, we demonstrated a mutual interaction between NCX1 and TRPC6 (and ROC-mediated Ca2+ entry). Considerable evidence has indicated that circulating endogenous ouabain is increased in several forms of salt-dependent hypertension (29, 39, 43) and in as many as half of all patients with essential hypertension (61, 65). Thus, our new findings may have broad implications for elucidating the pathogenesis of the elevated BP in these conditions.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants NS-048263 (to V. A. Golovina) and P01-HL-078870 Project 1 (to M. P. Blaustein) and Project 2 (to V. A. Golovina) and Core B (to J. M. Hamlyn) and by funds from the University of Maryland School of Medicine.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest are declared by the author(s).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. W. Gil Wier for comments on the manuscript and Katherine Frankel for assistance with the preparation of the manuscript.

Present address of M. V. Pulina: Dept. of Medicine, Div. of Cardiology, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, NY 10021.

Present address of R. Berra-Romani: School of Medicine, Benemèrita Universidad Autònoma de Puebla, 72000 Puebla, México.

REFERENCES

- 1.Albert AP, Large WA. Signal transduction pathways and gating mechanisms of native TRP-like cation channels in vascular myocytes. J Physiol 570: 45–51, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arnon A, Hamlyn JM, Blaustein MP. Na+ entry via store-operated channels modulates Ca2+ signaling in arterial myocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 278: C163–C173, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arnon A, Hamlyn JM, Blaustein MP. Ouabain augments Ca2+ transients in arterial smooth muscle without raising cytosolic Na+. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 279: H679–H691, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bae YM, Kim A, Lee YJ, Lim W, Noh YH, Kim EJ, Kim J, Kim TK, Park SW, Kim B, Cho SI, Kim DK, Ho WK. Enhancement of receptor-operated cation current and TRPC6 expression in arterial smooth muscle cells of deoxycorticosterone acetate-salt hypertensive rats. J Hypertens 25: 809–817, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beech DJ, Muraki K, Flemming R. Non-selective cationic channels of smooth muscle and the mammalian homologues of Drosophila TRP. J Physiol 559: 685–706, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berra-Romani R, Mazzocco-Spezzia A, Pulina MV, Golovina VA. Ca2+ handling is altered when arterial myocytes progress from a contractile to a proliferative phenotype in culture. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 295: C779–C790, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bers DM. Cardiac excitation-contraction coupling. Nature 415: 198–205, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blaustein MP. Sodium ions, calcium ions, blood pressure regulation, and hypertension: a reassessment and a hypothesis. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 232: C165–C173, 1977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blaustein MP, Juhaszova M, Golovina VA. The cellular mechanism of action of cardiotonic steroids: a new hypothesis. Clin Exp Hypertens 20: 691–703, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blaustein MP, Wier W. Local sodium, global reach: filling the gap between salt and hypertension. Circ Res 101: 959–961, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blaustein MP, Zhang J, Chen L, Song H, Raina H, Kinsey SP, Izuka M, Iwamoto T, Kotlikoff MI, Lingrel JB, Philipson KD, Wier WG, Hamlyn JM. The pump, the exchanger, and endogenous ouabain: signaling mechanisms that link salt retention to hypertension. Hypertension 53: 291–298, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bohr DF, Dominiczak AF, Webb RC. Pathophysiology of the vasculature in hypertension. Hypertension 18: III69–III75, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Briones AM, Xavier FE, Arribas SM, Gonzalez MC, Rossoni LV, Alonso MJ, Salaices M. Alterations in structure and mechanics of resistance arteries from ouabain-induced hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 291: H193–H201, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cain AE, Khalil RA. Pathophysiology of essential hypertension: role of the pump, the vessel, and the kidney. Semin Nephrol 22: 3–16, 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dibb KM, Graham HK, Venetucci LA, Eisner DA, Trafford AW. Analysis of cellular calcium fluxes in cardiac muscle to understand calcium homeostasis in the heart. Cell Calcium 42: 503–512, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dietrich A, Chubanov V, Kalwa H, Rost BR, Gudermann T. Cation channels of the transient receptor potential superfamily: their role in physiological and pathophysiological processes of smooth muscle cells. Pharmacol Ther 112: 744–760, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dostanic-Larson I, Van Huysse JW, Lorenz JN, Lingrel JB. The highly conserved cardiac glycoside binding site of Na,K-ATPase plays a role in blood pressure regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 15845–15850, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dostanic I, Paul RJ, Lorenz JN, Theriault S, Van Huysse JW, Lingrel JB. The α2-isoform of Na-K-ATPase mediates ouabain-induced hypertension in mice and increased vascular contractility in vitro. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 288: H477–H485, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fellner SK, Arendshorst WJ. Angiotensin II-stimulated Ca2+ entry mechanisms in afferent arterioles: role of transient receptor potential canonical channels and reverse Na+/Ca2+ exchange. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 294: F212–F219, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ferrandi M, Manunta P, Rivera R, Bianchi G, Ferrari P. Role of the ouabain-like factor and Na-K pump in rat and human genetic hypertension. Clin Exp Hypertens 20: 629–639, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feske S, Gwack Y, Prakriya M, Srikanth S, Puppel SH, Tanasa B, Hogan PG, Lewis RS, Daly M, Rao A. A mutation in Orai1 causes immune deficiency by abrogating CRAC channel function. Nature 441: 179–185, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giachini FR, Chiao CW, Carneiro FS, Lima VV, Carneiro ZN, Dorrance AM, Tostes RC, Webb RC. Increased activation of stromal interaction molecule-1/Orai-1 in aorta from hypertensive rats: a novel insight into vascular dysfunction. Hypertension 53: 409–416, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gibson A, McFadzean I, Wallace P, Wayman CP. Capacitative Ca2+ entry and the regulation of smooth muscle tone. Trends Pharmacol Sci 19: 266–269, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Golovina VA. Cell proliferation is associated with enhanced capacitative Ca2+ entry in human arterial myocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 277: C343–C349, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Golovina VA. Visualization of localized store-operated calcium entry in mouse astrocytes. Close proximity to the endoplasmic reticulum. J Physiol 564: 737–749, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Golovina VA, Blaustein MP. Preparation of primary cultured mesenteric artery smooth muscle cells for fluorescent imaging and physiological studies. Nat Protoc 1: 2681–2687, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Golovina VA, Blaustein MP. Spatially and functionally distinct Ca2+ stores in sarcoplasmic and endoplasmic reticulum. Science 275: 1643–1648, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Golovina VA, Platoshyn O, Bailey CL, Wang J, Limsuwan A, Sweeney M, Rubin LJ, Yuan JX. Upregulated TRP and enhanced capacitative Ca2+ entry in human pulmonary artery myocytes during proliferation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 280: H746–H755, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hamlyn JM, Blaustein MP, Bova S, DuCharme DW, Harris DW, Mandel F, Mathews WR, Ludens JH. Identification and characterization of a ouabain-like compound from human plasma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 88: 6259–6263, 1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hill AJ, Hinton JM, Cheng H, Gao Z, Bates DO, Hancox JC, Langton PD, James AF. A TRPC-like non-selective cation current activated by α1-adrenoceptors in rat mesenteric artery smooth muscle cells. Cell Calcium 40: 29–40, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hofmann T, Obukhov AG, Schaefer M, Harteneck C, Gudermann T, Schultz G. Direct activation of human TRPC6 and TRPC3 channels by diacylglycerol. Nature 397: 259–263, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Inoue R, Jensen LJ, Shi J, Morita H, Nishida M, Honda A, Ito Y. Transient receptor potential channels in cardiovascular function and disease. Circ Res 99: 119–131, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Inoue R, Okada T, Onoue H, Hara Y, Shimizu S, Naitoh S, Ito Y, Mori Y. The transient receptor potential protein homologue TRP6 is the essential component of vascular α1-adrenoceptor-activated Ca2+-permeable cation channel. Circ Res 88: 325–332, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Iwamoto T, Kita S, Zhang J, Blaustein MP, Arai Y, Yoshida S, Wakimoto K, Komuro I, Katsuragi T. Salt-sensitive hypertension is triggered by Ca2+ entry via Na+/Ca2+ exchanger type-1 in vascular smooth muscle. Nat Med 10: 1193–1199, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Juhaszova M, Blaustein MP. Distinct distribution of different Na+ pump α subunit isoforms in plasmalemma. Physiological implications. Ann NY Acad Sci 834: 524–536, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Juhaszova M, Blaustein MP. Na+ pump low and high ouabain affinity α subunit isoforms are differently distributed in cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 1800–1805, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Juhaszova M, Shimizu H, Borin ML, Yip RK, Santiago EM, Lindenmayer GE, Blaustein MP. Localization of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger in vascular smooth muscle and in neurons and astrocytes. Ann NY Acad Sci 779: 318–335, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kahle KT, Rinehart J, Giebisch G, Gamba G, Hebert SC, Lifton RP. A novel protein kinase signaling pathway essential for blood pressure regulation in humans. Trends Endocrinol Metab 19: 91–95, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kaide J, Ura N, Torii T, Nakagawa M, Takada T, Shimamoto K. Effects of digoxin-specific antibody Fab fragment (Digibind) on blood pressure and renal water-sodium metabolism in 5/6 reduced renal mass hypertensive rats. Am J Hypertens 12: 611–619, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kaplan NM. Clinical Hypertension Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kashihara T, Nakayama K, Matsuda T, Baba A, Ishikawa T. Role of Na+/Ca2+ exchanger-mediated Ca2+ entry in pressure-induced myogenic constriction in rat posterior cerebral arteries. J Pharm Sci 110: 218–222, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kimura K, Manunta P, Hamilton BP, Hamlyn JM. Different effects of in vivo ouabain and digoxin on renal artery function and blood pressure in the rat. Hypertens Res 23, Suppl: S67–S76, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Krep H, Price DA, Soszynski P, Tao QF, Graves SW, Hollenberg NK. Volume sensitive hypertension and the digoxin-like factor. Reversal by a Fab directed against digoxin in DOCA-salt hypertensive rats. Am J Hypertens 8: 921–927, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kwan CY, Putney JW., Jr Uptake and intracellular sequestration of divalent cations in resting and methacholine-stimulated mouse lacrimal acinar cells. Dissociation by Sr2+ and Ba2+ of agonist-stimulated divalent cation entry from the refilling of the agonist-sensitive intracellular pool. J Biol Chem 265: 678–684, 1990 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Levy MN, Pappano AJ. Cardiovascular Physiology (9th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Mosby, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lin MJ, Leung GP, Zhang WM, Yang XR, Yip KP, Tse CM, Sham JS. Chronic hypoxia-induced upregulation of store-operated and receptor-operated Ca2+ channels in pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells: a novel mechanism of hypoxic pulmonary hypertension. Circ Res 95: 496–505, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu D, Yang D, He H, Chen X, Cao T, Feng X, Ma L, Luo Z, Wang L, Yan Z, Zhu Z, Tepel M. Increased transient receptor potential canonical type 3 channels in vasculature from hypertensive rats. Hypertension 53: 70–76, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lorenz JN, Loreaux EL, Dostanic-Larson I, Lasko V, Schnetzer JR, Paul RJ, Lingrel JB. ACTH-induced hypertension is dependent on the ouabain-binding site of the α2-Na-K-ATPase subunit. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 295: H273–H280, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Magyar CE, Wang J, Azuma KK, McDonough AA. Reciprocal regulation of cardiac Na-K-ATPase and Na+/Ca2+ exchanger: hypertension, thyroid hormone, development. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 269: C675–C682, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Manunta P, Hamilton BP, Hamlyn JM. Salt intake and depletion increase circulating levels of endogenous ouabain in normal men. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 290: R553–R559, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Manunta P, Rogowski AC, Hamilton BP, Hamlyn JM. Ouabain-induced hypertension in the rat: relationships among plasma and tissue ouabain and blood pressure. J Hypertens 12: 549–560, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Manunta P, Stella P, Rivera R, Ciurlino D, Cusi D, Ferrandi M, Hamlyn JM, Bianchi G. Left ventricular mass, stroke volume, and ouabain-like factor in essential hypertension. Hypertension 34: 450–456, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Martinez-Lemus LA, Hill MA, Meininger GA. The plastic nature of the vascular wall: a continuum of remodeling events contributing to control of arteriolar diameter and structure. Physiology (Bethesda) 24: 45–57, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Meneton P, Jeunemaitre X, de Wardener H, MacGregor G. Links between dietary salt intake, renal salt handling, blood pressure, and cardiovascular diseases. Physiol Rev 85: 679–715, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mulvany MJ. Small artery remodeling in hypertension. Curr Hypertens Rep 4: 49–55, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ng LC, Gurney AM. Store-operated channels mediate Ca2+ influx and contraction in rat pulmonary artery. Circ Res 89: 923–929, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.O'Brien WJ, Lingrel JB, Wallick ET. Ouabain binding kinetics of the rat alpha two and alpha three isoforms of the sodium-potassium adenosine triphosphate. Arch Biochem Biophys 310: 32–39, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Oparil S, Zaman MA, Calhoun DA. Pathogenesis of hypertension. Ann Intern Med 139: 761–776, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pacaud P, Loirand G, Bolton TB, Mironneau C, Mironneau J. Intracellular cations modulate noradrenaline-stimulated calcium entry into smooth muscle cells of rat portal vein. J Physiol 456: 541–556, 1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Parekh AB, Putney JW., Jr Store-operated calcium channels. Physiol Rev 85: 757–810, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pierdomenico SD, Bucci A, Manunta P, Rivera R, Ferrandi M, Hamlyn JM, Lapenna D, Cuccurullo F, Mezzetti A. Endogenous ouabain and hemodynamic and left ventricular geometric patterns in essential hypertension. Am J Hypertens 14: 44–50, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Poburko D, Liao CH, Lemos VS, Lin E, Maruyama Y, Cole WC, van Breemen C. Transient receptor potential channel 6-mediated, localized cytosolic [Na+] transients drive Na+/Ca2+ exchanger-mediated Ca2+ entry in purinergically stimulated aorta smooth muscle cells. Circ Res 101: 1030–1038, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ramirez-Gil JF, Trouve P, Mougenot N, Carayon A, Lechat P, Charlemagne D. Modifications of myocardial Na+,K+-ATPase isoforms and Na+/Ca2+ exchanger in aldosterone/salt-induced hypertension in guinea pigs. Cardiovasc Res 38: 451–462, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Roos J, DiGregorio PJ, Yeromin AV, Ohlsen K, Lioudyno M, Zhang S, Safrina O, Kozak JA, Wagner SL, Cahalan MD, Velicelebi G, Stauderman KA. STIM1, an essential and conserved component of store-operated Ca2+ channel function. J Cell Biol 169: 435–445, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rossi G, Manunta P, Hamlyn JM, Pavan E, De Toni R, Semplicini A, Pessina AC. Immunoreactive endogenous ouabain in primary aldosteronism and essential hypertension: relationship with plasma renin, aldosterone and blood pressure levels. J Hypertens 13: 1181–1191, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shah JR, Laredo J, Hamilton BP, Hamlyn JM. Different signaling pathways mediate stimulated secretions of endogenous ouabain and aldosterone from bovine adrenocortical cells. Hypertension 31: 463–468, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shelly DA, He S, Moseley A, Weber C, Stegemeyer M, Lynch RM, Lingrel J, Paul RJ. Na+ pump α2-isoform specifically couples to contractility in vascular smooth muscle: evidence from gene-targeted neonatal mice. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 286: C813–C820, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Song H, Lee MY, Kinsey SP, Weber DJ, Blaustein MP. An N-terminal sequence targets and tethers Na+ pump α2 subunits to specialized plasma membrane microdomains. J Biol Chem 281: 12929–12940, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tamura M, Harris TM, Phillips D, Blair IA, Wang YF, Hellerqvist CG, Lam SK, Inagami T. Identification of two cardiac glycosides as Na+-pump inhibitors in rat urine and diet. J Biol Chem 269: 11972–11979, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Thompson LP, Bruner CA, Lamb FS, King CM, Webb RC. Calcium influx and vascular reactivity in systemic hypertension. Am J Cardiol 59: 29A–34A, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tosun M, Paul RJ, Rapoport RM. Coupling of store-operated Ca2+ entry to contraction in rat aorta. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 285: 759–766, 1998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.van Breemen C, Chen Q, Laher I. Superficial buffer barrier function of smooth muscle sarcoplasmic reticulum. Trends Pharmacol Sci 16: 98–105, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Venkatachalam K, Ma HT, Ford DL, Gill DL. Expression of functional receptor-coupled TRPC3 channels in DT40 triple receptor InsP3 knockout cells. J Biol Chem 276: 33980–33985, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Vig M, Peinelt C, Beck A, Koomoa DL, Rabah D, Koblan-Huberson M, Kraft S, Turner H, Fleig A, Penner R, Kinet JP. CRACM1 is a plasma membrane protein essential for store-operated Ca2+ entry. Science 312: 1220–1223, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wang JG, Staessen JA, Messaggio E, Nawrot T, Fagard R, Hamlyn JM, Bianchi G, Manunta P. Salt, endogenous ouabain and blood pressure interactions in the general population. J Hypertens 21: 1475–1481, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Weigand L, Foxson J, Wang J, Shimoda LA, Sylvester JT. Inhibition of hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction by antagonists of store-operated Ca2+ and nonselective cation channels. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 289: L5–L13, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Welsh DG, Morielli AD, Nelson MT, Brayden JE. Transient receptor potential channels regulate myogenic tone of resistance arteries. Circ Res 90: 248–250, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Xu L, Kappler CS, Mani SK, Shepherd NR, Renaud LS, Snider P, Conway SJ, and Menick DR. Chronic administration of KB-R7943 induces upregulation of cardiac NCX1. J Biol Chem 284: 27265–27272, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Xu SZ, Beech DJ. TrpC1 is a membrane-spanning subunit of store-operated Ca2+ channels in native vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ Res 88: 84–87, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Xu SZ, Boulay G, Flemming R, Beech DJ. E3-targeted anti-TRPC5 antibody inhibits store-operated calcium entry in freshly isolated pial arterioles. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 291: H2653–H2659, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yu Y, Fantozzi I, Remillard CV, Landsberg JW, Kunichika N, Platoshyn O, Tigno DD, Thistlethwaite PA, Rubin LJ, Yuan JX. Enhanced expression of transient receptor potential channels in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 13861–13866, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yuan CM, Manunta P, Hamlyn JM, Chen S, Bohen E, Yeun J, Haddy FJ, Pamnani MB. Long-term ouabain administration produces hypertension in rats. Hypertension 22: 178–187, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zhang J, Hamlyn JM, Karashima EH, Raina H, Mauban JR, Izuka M, Berra-Romani R, Zulian A, Wier WG, Blaustein MP. Low-dose ouabain constricts small arteries from ouabain hypertensive rats: implications for sustained elevation of vascular resistance. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 297: H1140–H1150, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zhang J, Lee MY, Cavalli M, Chen L, Berra-Romani R, Balke CW, Bianchi G, Ferrari P, Hamlyn JM, Iwamoto T, Lingrel JB, Matteson DR, Wier WG, Blaustein MP. Sodium pump α2 subunits control myogenic tone and blood pressure in mice. J Physiol 569: 243–256, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zhang S, Dong H, Rubin LJ, Yuan JX. Upregulation of Na+/Ca2+ exchanger contributes to the enhanced Ca2+ entry in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells from patients with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 292: C2297–C2305, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]