Abstract

BACKGROUND

Surrogacy was prohibited in the Netherlands until 1994, at which time the Dutch law was changed from the general prohibition of surrogacy to the prohibition of commercial surrogacy. This paper describes the results from the first and only Dutch Centre for Non-commercial IVF Surrogacy between 1997 and 2004.

METHODS

A prospective study was conducted of all intended parents, and surrogate mothers and their partners (if present), in which medical, psychological and legal aspects of patient selection were assessed by questionnaires and interviews developed for this study.

RESULTS

More than 500 couples enquired about surrogacy by telephone or e-mail. More than 200 couples applied for surrogacy in the Centre, of which, after extensive screening, 35 couples actually entered the IVF programme and 24 completed the treatment, resulting in 16 children being born to 13 women. Recommendations for non-commercial surrogacy are given, including abandoning the 1-year waiting period before adoption, currently dictated by law, avoiding a period of unnecessary psychological distress.

CONCLUSIONS

Our study has shown that non-commercial IVF surrogacy is feasible, with good results in terms of pregnancy outcome and psychological outcome for all parents, and with no legal problems relating to the adoption procedures arising. The extensive screening of medical, psychological and legal aspects was a key element in helping to ensure the safety and success of the procedure.

Keywords: surrogacy, IVF/ICSI outcome, counselling, infertility, assisted reproduction

Introduction

IVF or gestational surrogacy entails fertilization of an ovum from the intended mother by the semen of the intended father by means of IVF, after which the embryo is transferred to the uterus of a surrogate mother. After pregnancy and delivery, the baby is legally adopted by the intended parents, thus providing them with their own genetical offspring.

Surrogacy was first described in the USA in 1985 (Utian et al., 1985), but a guideline on this subject was not issued until 2008 (ACOG, 2008). In Europe, legal surrogacy started in the UK in 1989, after publication of the Warnock report on human fertilization and embryology in 1984 (Brahams, 1984; Wells, 1984; Brinsden et al., 2000; Brinsden, 2003). Surrogacy is now also available in the Netherlands, Finland and Belgium (Söderström-Anttila et al., 2002; Denys et al., 2007), whereas in Greece, its introduction is under discussion (Chliaoutakis et al., 2002). Israel has had guidelines for surrogacy since 1997 (Benshushan and Schenker, 1997).

Surrogacy was prohibited by law in the Netherlands until 1994. In 1986, a nationwide gynaecological cancer patient organization raised the question as to whether it would be possible for patients to have their own genetic offspring after undergoing surgical treatment for gynaecological cancer (Olijf Foundation). A campaign was initiated by some of the gynaecologists involved to bring this subject to the attention of the Dutch gynaecological field and the Dutch government. Finally, in 1994, the law was changed from a general prohibition of surrogacy to a prohibition of commercial surrogacy (IVF Planningsbesluit, 1997). This paved the way for non-commercial IVF surrogacy, which then became possible, under strict circumstances. This change in the law was prepared by the Dutch Minister of Health, after consultation with representatives of the gynaecological cancer patient organization, together with experts in the fields of gynaecology, psychology, law and ethics who provided suggestions for the preparation of guidelines on the subject. As a result of this process, the Minister of Health advised the Dutch Society of Obstetrics and Gynaecology (NVOG) to allow the introduction of non-commercial surrogacy, only under well-documented study circumstances, which should ultimately lead to strict guidelines for the Society's members. This led to the foundation of a single Dutch Centre for Non-commercial IVF Surrogacy in Zaandam, the Netherlands, where a prospective study was carried out between 1997 and 2001. The methods and outcome of all medical, psychological, ethical and legal aspects of referred patients and their babies were described in a thesis in Dutch (Dermout, 2001).

The promising findings led to the continuation of the Centre between 2001 and 2004. This paper gives an account of the experiences encountered during the 7-year period, 1997–2004. The objectives of the present study were to reject or accept the hypothesis that non-commercial IVF surrogacy offered a safe method, in terms of medical, psychological and legal aspects, for a strictly defined group of women to have children under stringent guidelines. No other legal surrogacy procedures were conducted in the Netherlands during this period, and all Dutch gynaecologists referred their patients requesting surrogacy to our Centre.

Materials and Methods

Between 1997 and 2004, all patients opting for surrogacy were registered prospectively and managed according to a strict protocol with regard to screening and selection, treatment and follow-up. All candidates (intended parents and surrogate mothers or parents) were seen in the Dutch Centre for IVF Surrogacy.

The Centre's activities were brought to the attention of fellow colleagues by two papers published in Dutch medical journals, which described the indications and procedures for the referral of possible candidates (Dermout et al., 1998, 2001). Patients could also make an appointment on their own initiative. Since many patients did not match the entrance criteria (below), initial screening by telephone was encouraged, thus avoiding unnecessary consultations. Subjects raised during the initial screening are summarized in Table I. If these requirements were met by the candidates, an appointment for further evaluation and counselling was made.

Table I.

Criteria used in initial screening by telephone of candidates for IVF surrogacy

| Intended mother |

| Absence of a functional uterus, e.g. resulting from cancer treatment or following hysterectomy for other medical reasons, e.g. post-partum haemorrhage or Mayer–Rokitansky–Küster syndrome |

| Contraindications for pregnancy owing to life-threatening medical problems with a fair prognosis, e.g. severe antiphospholipid syndrome or after liver transplantation |

| Age <41 years |

| Intended mother and father |

| No police record (e.g. sexual offence) in view of adoption procedure |

| Surrogate mother |

| Healthy multipara with a normal functioning uterus and an uncomplicated obstetric history |

| Ideological reasons for surrogacy, i.e. non-commercial, which usually means a sister, sister-in-law or good friend as surrogate mother |

| Age <45 years |

Candidates were assessed according to strict guidelines which addressed the medical, psychological and legal aspects. They were all seen at the Centre. After successfully and unambiguously passing the intake assessment, the candidates were enrolled for IVF in one of three selected IVF clinics in the Netherlands (the Reinier de Graaf Hospital in Voorburg, the Academic Medical Centre University Hospital in Amsterdam or the University Hospital in Groningen).

Whenever the entrance criteria were not met or were problematic, cases were discussed with the Centre's Consultation Board. This Board (a team of six gynaecologists from various Dutch medical centres, a professor in psychology, a lawyer and a professor in ethics) discussed the Centre's surrogacy problems in general and those encountered in individual cases. At each meeting with the Consultation Board, all candidates were discussed, including those who were accepted outright by the Centre.

Individual selection criteria are discussed below.

Medical intake

During the first visit, at least the intended mother and the surrogate mother were seen. The medical history of the intended mother was assessed. Whenever necessary, reports from other specialists were requested in order to document her history.

Earlier treatment for gynaecological cancer or a diagnosis of Mayer–Rokitansky–Küster syndrome (being born without a uterus) was considered to be a straight-forward indication for surrogacy (Ben-Rafael et al., 1998; Beski et al., 2000). Sometimes, however, the indication for surrogacy was less clear, e.g. if a previous hysterectomy had been carried out for benign conditions at the patient's own request. Other examples of difficult decisions occurred when surrogacy was requested by women without a previous hysterectomy but with a medical condition that could become aggravated and pose an even greater health threat if combined with pregnancy (e.g. after a second kidney transplantation). In these cases, the question as to whether the hormones needed for the IVF procedure would be tolerated also required consideration. The Centre even received requests from patients who were life-threateningly ill, even without the added risk of pregnancy: after careful consideration by the Consultation Board, virtually all requests of the last named category were denied.

Additional medical tests were performed (e.g. LH/FSH hormone assessment, a Pap smear and screening for sexually transmitted diseases, including human immunodeficiency virus).

The history of the surrogate mother and her date of birth were checked, as was her obstetric history. She should be healthy, have given birth to at least one child, have had normal pregnancies and deliveries and should not be at increased risk of medical or psychological problems.

Psychological intake

At the second appointment, all four candidates (if the surrogate mother had no partner: all three) were interviewed separately, to ensure that all of them agreed with the procedure and to give them the opportunity to speak freely. This appointment also gave the Centre the possibility of uncovering any covert attempts at commercial surrogacy. All the interviews were audio-recorded and could be checked by the psychologist of the Consultation Board whenever this seemed necessary.

After passing the interviews, all four candidates were invited to take a psychological screening test by completing three validated questionnaires: NPV (a personality test), symptom checklist 90 (SCL-90, a complaint and quality-of-life test) and MMQ (Maudsley Marital Questionnaire, a relational and sexual well-being test), and to repeat the SCL-90 and the MMQ 1–4 years after completing the IVF procedure (NPV, 1974; SCL-90, 1986; MMQ).

Legal intake

In collaboration with the Centre for Surrogacy, three lawyers from different firms were trained in the aspects of IVF surrogacy (Schoots et al., 2004). The Centre carried out the legal intake assessment using a list of 99 items which were discussed with the intended and surrogate mother/parents. These criteria have been listed earlier (Dermout, 2001). In summary, the list addressed the child (e.g. what to do in the case of multiple pregnancies or birth defects) and the surrogate mother (e.g. complications during pregnancy or delivery, agreements about smoking, drinking and working, and the expected support by the intended parents to the surrogate mother). Furthermore, the list addressed various legal matters (visiting the lawyer, starting the adoption procedure, making a will in order to cover all eventualities), financial aspects (multiple insurances, a settlement about pregnancy-related costs to be paid by the intended parents) and other practicalities (what to tell the respective parents, children, friends and colleagues; whether or not surrogacy should be revealed to the future child) and finally what to do in the case of an unforeseen legal conflict (mediation or otherwise). After all these items had been discussed and agreed upon, couples were referred to one of the lawyers to sign the legal contract between the intended and surrogate parents before the IVF procedure was started.

As soon as the IVF procedure resulted in a positive pregnancy test, the Centre contacted the lawyer of the Child Care and Protection Board, the authority from which permission is required to enable adoption in the Netherlands. In the last weeks of pregnancy, the legal procedure was started, thus enabling the prospective parents to officially adopt the child at exactly 1 year after birth, as dictated by current Dutch law. The baby was handed over to the intended parents directly after delivery as a foster child, until adoption could take place at 1 year after birth.

Results

Of more than 500 enquiries made by telephone calls, e-mails and during some appointments, more than 300 intended mothers were rejected outright because they failed to meet the basic requirements. These cases concerned non-serious requests, merely informative enquiries, those without a surrogate mother, single intended mothers without a partner and infertile couples with a previous history of unsuccessful IVF treatments. These telephone calls were given a time limit and the e-mails were answered by a standard response explaining why the requirements for entrance were not met.

Eventually, 202 couples remained for official initial intake at the Centre. Of these, 97 were not accepted because of failure to meet the basic requirements (Table I), leaving 105 intended parents.

Medical reasons for dropping out

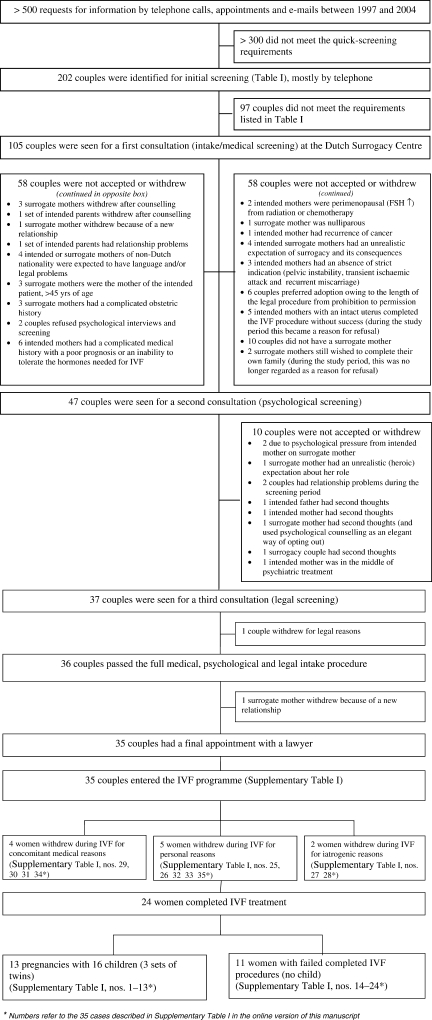

Between 1997 and 2004, 105 sets of intended parents, together with 105 surrogate mothers and 83 partners (408 candidates in total) visited the Centre with a request for surrogacy, having passed the initial screening (Fig. 1). Of these 105 couples, 58 withdrew or were not accepted after the medical intake for various reasons (summarized in Table I), leaving 47 couples for the second appointment for the psychological intake and counselling procedure.

Figure 1.

Patient flow in Dutch study of IVF surrogacy with reasons for refusal or withdrawal.

Psychological reasons for dropping out

Among the 47 couples visiting the psychological interview, another 10 couples were denied surrogacy or withdrew their request after screening.

The psychological tests (NPV, MMQ and SLC-90) were used for documentation purposes only, both before and after the procedure. It was not possible to ‘fail’ these tests. The psychological selection was based on the interviews alone.

Legal reasons for dropping out

Thirty-seven couples entered the legal screening procedure. Only one couple withdrew because of the legal consequences of surrogacy. Because the procedure for surrogacy was new in the Netherlands, at the start of this programme in 1997, the list of legal items was gradually extended from 22 to 99 items in a self-learning process during the study period. The remaining 36 couples were ready for referral to a specialized lawyer for signing a final contract. Just before visiting the lawyer, one surrogate mother withdrew from the procedure because of objections from her new partner, whom she had met during the screening period.

Thirty-five couples visited one of the Centre's lawyers. After the extensive legal preparation in the Surrogacy Centre, no couples decided to stop after consulting the lawyers, so all 35 couples started the IVF programme (Supplementary Table SI).

Of the surrogate mothers, 10 (29%) were sisters, 7 (20%) were sisters-in-law and 18 (51%) were friends of the intended mother, whereas 31 (89%) of the surrogate mothers had a partner and 4 (11%) were single.

During the IVF procedures, another 11 couples left the study. Twenty-four couples eventually went through a full IVF programme.

Medical outcome

Indications and outcomes of these 35 cases are described in Supplementary Table SI. Of the 24 couples undergoing the complete IVF programme, 16 children were born to 13 women: 7 boys and 9 girls, including three sets of twins. Eleven women who completed IVF or cryo-embryo transfer treatments did not achieve an ongoing pregnancy. The three sets of twins were born at 31, 36 and 36 weeks gestation, whereas all other children were born between 37 and 41 weeks. All fetal weights were in the normal range for gestational age. One twin girl was born with severe congenital malformations (hydrocephalus and spina bifida), detected in the 20th gestational week. No problems were encountered in accepting these twins, probably as a result of the intensive screening programme which also addressed the unfortunate possibility of handicapped children, together with the legal aspects involved. Both girls were warmly welcomed by the intended parents and adopted a year later.

Psychological follow-up study

One to 4 years after the initial psychological tests, all candidates entering the IVF programme, whether successful or not, were asked to complete the SCL-90 and the MMQ once again. This showed that neither the prospective nor the surrogate parents had experienced major negative or harmful consequences, even if no child was born. The couples with a child were somewhat happier than those couples without a child. Just having the opportunity to become pregnant, even if unsuccessful, softened the pain of being born without a uterus (Mayer–Rokitansky–Küster syndrome) or the pain of losing one's uterus and fertility as a result of cancer treatment.

Legal outcome

In all 16 instances, the Child Care and Protection Board gave a positive recommendation on future adoption by the intended parents. This advice was followed by the court in all cases, thereby successfully completing the adoption procedure after exactly 1 year.

Discussion

A search of the literature revealed a few retrospective surrogacy studies which had collected data from several institutions in one region or country (Israel: Schenker, 1997; Ohio USA: Goldfarb et al., 2000; Australia: Stafford-Bell and Copeland, 2001; Finland: Söderström-Anttila et al., 2002). We could not find any prospective study or any nationwide study, similar to ours. We also found interesting articles about attitudes towards surrogacy in countries which had not yet performed the procedure (Chliaoutakis, 2002; Chliaoutakis et al., 2002; Poote and vd Akker, 2009). In our opinion, these theoretical studies do not always reflect the reality of surrogacy. There is a difference among candidates, especially surrogate mothers, between talking about surrogacy and actually becoming involved. During our study, a lot of surrogate mothers offered their help, but later on (realizing all the consequences after intake and the extensive screening), a lot of them withdrew. That is one of the reasons for the large reduction from 500 to 105 couples in the beginning (Fig. 1), and some of the 12 dropouts in the official screening part.

Some previous findings are completely the opposite to our findings, such as Chliaoutakis et al.'s statement (in their Table II) that surrogacy is generally more acceptable in the case of strangers than it is in the case of family members (Chliaoutakis et al., 2002). In our study, none of our couples experienced problems in their social environment after telling family, friends and colleagues.

Despite the ethical and religious ramifications, the Dutch government was willing to allow non-commercial IVF surrogacy under strict conditions within this study.

Of all the couples who visited the Centre for the first consultation, 33% (35/105) were accepted for the IVF programme. As a result of the rigorous screening programme, the majority of candidates for surrogacy were not accepted or withdrew, i.e. 67% (n = 70) of those visiting the Centre after the initial screening, mostly by telephone. Some candidates not meeting the criteria managed to get through the initial screening procedure, probably by withholding information, but were later found to be unsuitable when interviewed face to face during their first visit. Of the 105 couples visiting the Centre, 55% (n = 58) were not accepted for medical reasons and 10% (n = 10) were rejected for psychological reasons. One couple withdrew after the appointment for legal counselling (<1%) and one surrogate mother withdrew even later in the process, just before the IVF procedure (<1%). Of those who were not accepted (n = 70), the Centre refused 75% (n = 53), whereas 24% of couples (n = 17) withdrew because of serious reservations which developed after having been counselled. The lawyers did not turn any candidates down.

Medical aspects

It remains debatable whether or not the criteria, as applied in our programme, were the right ones or, arguably, were perhaps too strict, or even paternalistic. It was painful refusing three well-motivated women because of their age (>45 years), who volunteered as surrogate mothers for their own daughters, all former cancer patients. This decision would probably have been different now, in view of the more recent discussions about age and motherhood in general.

The arguments for refusal in the case of a previous hysterectomy for benign conditions are debatable. Hysterectomies performed for strict medical reasons were usually accepted as indications, e.g. when performed for post-partum haemorrhage. The Centre was reluctant to offer its services to women who merely intended to avoid being pregnant for dubious (possibly ill-motivated) reasons, e.g. extreme fear of delivery, or because of a pregnancy's supposedly deleterious impact on their body and future career, e.g. in professional fashion models. Concerns about the inappropriate use of surrogacy have been addressed earlier in the Warnock report and other publications (Brahams, 1984; Warnock, 1984; Wells, 1984; Chliaoutakis et al., 2002).

These cases were all extensively discussed with the Consultation Board. This also emphasizes the importance of one nationwide Consultation Board, especially if there is more than one surrogacy centre in a country. This Board should give guidance on shifting social opinions or when the development of new technologies requires adaptation of the clinical indications for surrogacy.

Psychological aspects

At the start of the surrogacy programme, we only invited the two women and the intended father for interviews. It soon became apparent that exclusion of the surrogate mother's partner was a mistake. Though not strictly required for medical or technical reasons, the partner (‘surrogate father’) was a key stakeholder in the entire process. Obviously, his support was essential for both the surrogate mother and the intended parents. If the partner had reservations, there was a higher withdrawal rate before or during the IVF procedure. This phenomenon also occurred whenever surrogate mothers embarked on new relationships during the process. During the study period, four withdrawals occurred when a single surrogate mother met a new partner.

The children from our study cohort are now between 5 and 11 years of age. A psychological survey with interviews on the medical, social and psychological aspects of the children and all parents is scheduled for the near future.

Legal aspects

When the Centre started, no legal procedures for surrogacy were available. With the Centre's growing experience, the list of legal items gradually extended during the first year. The reason for also discussing these items with the candidates in the Centre, and not only at the lawyers, was to emphasize the reality and seriousness of the entire undertaking. Up to that stage of the procedure, it all had seemed just an altruistic, almost unreal, adventure for many couples. Serious and even painful subjects which could easily be avoided earlier, e.g. an unexpected illness or death of one of the candidates, now needed to be addressed and to be arranged for properly. As a consequence, more serious discussions between the couples took place.

Another observation made during the study concerns the waiting period of 1 year between birth and adoption. This was deemed far too long by most couples. It represents a period of unnecessary psychological distress, while its purpose is completely unclear. In our strong opinion, this 1-year waiting period, which is dictated by law, should be abandoned, thus enabling immediate adoption after birth. This seems well justified in view of the rigorous screening procedure all future parents undergo as part of the programme. This would also create clarity should both intended parents die during the first year, i.e. while the surrogate parents are still the child's lawful and official parents. Our psychological survey showed that <50% of surrogate parents were willing and able to raise the child under such circumstances, as parenthood was not their intention from the very beginning. The legal procedure of our programme requires that the intended parents arrange guardianship and make a will to cover these eventualities. This would become unnecessary if adoption was arranged immediately after birth.

Financial aspects

Non-commercial surrogacy implies that the prospective parents compensate the surrogate mother for her expenses, e.g. costs of IVF, pregnancy, delivery (if not covered by health insurance), adoption procedure, insurance, costs of lawyers etc. This pilot study, carried out after a request by the nationwide gynaecological cancer patient organization, was not funded; the screening and intakes were done on an ideological basis by the gynaecologist and the psychologist of that organization (the first and the second authors of this article). Some patients with insurance excluding IVF had to pay for these procedures. Costs, therefore, ranged between €0 and €10 000 per couple. In the UK, costs reportedly vary between €0 and €18 000, with an average of €5144 (Peeraer, 2006). In the USA, in case of commercial surrogacy, costs may even be as high as €91 000–119 000.

In view of the principle that healthcare should be accessible for all, the choice between non-commercial and commercial surrogacy, evidently, is in favour of the first alternative.

Main finding of the thesis

The main findings of the original thesis were that non-commercial IVF surrogacy is of benefit to both the intended and the surrogate parents in terms of pregnancy outcome and psychological outcome. The psychological findings were analysed before the IVF procedure was started and again at least 1 year after the IVF procedures. A summary in English of the conclusions of this thesis is available (Dermout, 2001).

After our prospective study, we recommend that these procedures are restricted to a number of dedicated centres, with a central data-collection point and a nationwide Consultation Board on Surrogacy.

It is our strong belief, that ‘commercial’ surrogacy should be prohibited in order to prevent its abuse, and that non-commercial surrogacy should be an ‘ultimum remedium’. Legal, non-commercial surrogacy will prevent candidates from going to other countries or down illegal paths. Such solutions will be of no benefit to either the intended or the surrogate parents. These routes also have social implications. Arrangements have to be made for their own children should a trip abroad be required, and a solution for the absence from work must be sought, especially if the IVF procedure has to be repeated several times before the surrogate mother becomes pregnant. Other countries could apply different criteria for IVF surrogacy. The language barrier may be very troublesome because the procedures are complicated. Health insurance companies can refuse to pay for treatment abroad. In the case of commercial procedures, costs are likely to be excessively high. This has been confirmed in a recent article (Gamble et al., 2009).

After the study was closed in 2001, no guarantees for proper financial compensation for these special IVF procedures could be given. As a consequence, the first Dutch Centre for Surrogacy had to close its doors in 2004 owing to the lack of support from the IVF clinics. Because of the good results of the pilot study, the Free University Medical Centre in Amsterdam decided to restart the surrogacy programme in 2006, thereby initiating the second Dutch Centre for IVF Surrogacy. Our pilot study, however, has paved the way for more financial support, and nowadays, financial agreements with insurance companies have been made, which hopefully will provide a sound basis for further continuation of non-commercial surrogacy in the Netherlands.

In conclusion, our findings illustrate that non-commercial surrogacy is feasible, with good results in terms of pregnancy outcome and psychological outcome for all parents and with the absence of legal problems related to the adoption procedure. In achieving these results, the extensive screening on medical, psychological and legal aspects was a key element in helping to ensure the procedure's safety: safety for the prospective parents, the surrogate parents and the children, in medical, psychological and legal terms.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary data are available at http://humrep.oxfordjournals.org/.

Supplementary Material

References

- ACOG Committee Opinion. Number 397. Surrogate motherhood. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:465–470. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181666017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Rafael Z, Bar-Hava I, Levy T, Orvieto R. Simplifying ovulation induction for surrogacy in women with Mayer Rokitansky Küster Hauser syndrome. Hum Reprod. 1998;6:1470–1471. doi: 10.1093/humrep/13.6.1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benshushan A, Schenker JG. Legitimizing surrogacy in Israel. Hum Reprod. 1997;12:1832–1834. doi: 10.1093/humrep/12.8.1832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beski S, Gorgy A, Venkat G, Craft IL, Edmonds K. Gestational surrogacy: a feasible option for patients with Rokitansky syndrome. Hum Reprod. 2000;11:2326–2328. doi: 10.1093/humrep/15.11.2326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brahams D. Warnock report on human fertilisation and embryology. Lancet. 1984;2:239–239. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)90535-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinsden PR. Gestational surrogacy. Hum Reprod Update. 2003;9:483–91. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmg033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinsden PR, Appleton TC, Murray E, Hussei M, Akagbosu F, Marcus SF. Treatment by in vitro fertilization with surrogacy: experience of one British centre. Br Med J. 2000;320:924–929. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7239.924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chliaoutakis JE. A relationship between traditionally motivated patterns and gamete donation and surrogacy in urban areas of Greece. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:2187–2191. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.8.2187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chliaoutakis JE, Koukouli S, Papadakaki M. Using attitudinal indicators to explain the public's intention to have recourse to gamete donation and surrogacy. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:2995–3002. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.11.2995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denys K, Stuyver I, Dhont M. Hoogtechnologisch draagmoederschap in Vlaanderen. Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2007;63:1021–1029. [Google Scholar]

- Dermout SM. Ph.D. Thesis. University of Groningen; 2001. De eerste logeerpartij, hoogtechnologisch draagmoederschap in Nederland. copy of English abstract 'the first sleepover', sylvia@dermout.nl. [Google Scholar]

- Dermout SM, vd Wiel HBM, Jansen CAM, Heintz APM. Stand van zaken van hoogtechnologisch draagmoederschap in Nederland. Ned Tijdschr Obstet Gynaecol. 1998;111:332–333. abstract. [Google Scholar]

- Dermout SM, Bleker OP, Heintz APM, Jansen CAM, vd Wiel HBM. Hoogtechnologisch draagmoederschap in Nederland. Ned Tijdschr Obstet Gynaecol. 2001;14:200. [Google Scholar]

- Gamble N, Ghevaert LLP, Poole AE. Crossing the line: the legal and ethical problems of foreign surrogacy. Reprod Biomed. 2009;19:151–152. doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)60064-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldfarb JM, Austin C, Peskin B, Lisbona H, Desai N, de Mola JR. Fifteen years experience with an in-vitro fertilization surrogate gestational pregnancy programme. Hum Reprod. 2000;15:1075–1078. doi: 10.1093/humrep/15.5.1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IVF Planningsbesluit. Gezondheidsraad, advies aan Minister van Volksgezondheid, publicatienummer 1997/03. 2000.

- MMQ. Matrimony and Relationship Questionnaire, Maudsley Marital Questionnaire. Arindell; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- NPV. Dutch Personality Questionnaire. Lisse: Swets & Zeitlinger; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Olijf Foundation. Dutch patient society of gynecological cancer sufferers. 1986. www.olijf.nl .

- Peeraer M. ‘Acht handen op één buik’, surrogacy. 2006. Antenne 50-4.

- Poote AE, vd Akker OBA. British women's attitudes to surrogacy. Hum Reprod. 2009;24:139–145. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenker JG. Assisted reproduction practice in Europe: legal and ethical aspects. Hum Reprod Update. 1997;3:173–184. doi: 10.1093/humupd/3.2.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoots M, vanArkel J, Dermout SM. Draagmoederschap, afstamming, adoptie. Wetsaanpassing in verband met draagmoederschap? Tijdschr Familie Jeugdrecht. 2004;7/8:189–194. [Google Scholar]

- SCL-90. The Complaint Questionnaire. 1986 Derogatis et Arrindell, Etterna, Swets Test Services, Lisse. [Google Scholar]

- Söderström-Anttila V, Blomqvist T, Foudila T, Hippeläinen M, Kurunmäki H, Siegberg R, Tulppala M, Tuomi-Nikula M, Vilska S, Hovatta O. Experience of in vitro fertilization surrogacy in Finland. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2002;81:747–752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stafford-Bell MA, Copeland CM. Surrogacy in Australia: implantation rates have implications for embryo quality and uterine receptivity. Reprod Fertil Dev. 2001;13:99–104. doi: 10.1071/rd00044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utian WH, Sheean L, Goldfarb JM. Successful pregnancy after in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer from an infertile woman to a surrogate. N Engl J Med. 1985;313:1351–1352. doi: 10.1056/nejm198511213132112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- British House of Common; 1984. Warnock Committee's report on human reproduction, fertilization and embryology. July. [Google Scholar]

- Wells WT. Warnock report on human fertilization and embryology. Lancet. 1984;2:531–532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.