Abstract

Skeletal muscle contractions increase superoxide anion in skeletal muscle extracellular space. We tested the hypotheses that 1) after an isometric contraction protocol, xanthine oxidase (XO) activity is a source of superoxide anion in the extracellular space of skeletal muscle and 2) the increase in XO-derived extracellular superoxide anion during contractions affects skeletal muscle contractile function. Superoxide anion was monitored in the extracellular space of mouse gastrocnemius muscles by following the reduction of cytochrome c in muscle microdialysates. A 15-min protocol of nondamaging isometric contractions increased the reduction of cytochrome c in microdialysates, indicating an increase in superoxide anion. Mice treated with the XO inhibitor oxypurinol showed a smaller increase in superoxide anions in muscle microdialysates following contractions than in microdialysates from muscles of vehicle-treated mice. Intact extensor digitorum longus (EDL) and soleus muscles from mice were also incubated in vitro with oxypurinol or polyethylene glycol-tagged Cu,Zn-SOD. Oxypurinol decreased the maximum tetanic force produced by EDL and soleus muscles, and polyethylene glycol-tagged Cu,Zn-SOD decreased the maximum force production by the EDL muscles. Neither agent influenced the rate of decline in force production when EDL or soleus muscles were repeatedly electrically stimulated using a 5-min fatiguing protocol (stimulation at 40 Hz for 0.1 s every 5 s). Thus these studies indicate that XO activity contributes to the increased superoxide anion detected within the extracellular space of skeletal muscles during nondamaging contractile activity and that XO-derived superoxide anion or derivatives of this radical have a positive effect on muscle force generation during isometric contractions of mouse skeletal muscles.

Keywords: contractile function, free radicals, exercise

commoner and colleagues (10) in 1954 reported that skeletal muscle contains free radical species, but the biological importance of this finding was unclear until the early 1980s, when researchers identified a potential link between muscle function and free radical generation (12, 24). Further studies have shown that, in some circumstances, contractile activity of muscle can lead to altered muscle and blood glutathione levels and an increase in protein and DNA oxidation (41, 47). The free radicals produced from skeletal muscle appear to be involved in a number of physiological processes, including excitation-contraction coupling (43) and cell signaling (23). Reactive oxygen species (ROS) can also activate redox-sensitive transcription factors (20, 25). This activation can lead to increased expression of regulatory enzymes such as SOD, cytoprotective proteins such as heat shock proteins (28, 34), and other enzymes, such as inducible and endothelial nitric oxide (NO) synthase (14).

To understand the role of ROS in skeletal muscle, it is essential to identify and quantify specific ROS and establish their sites of production in muscle (22). During and after contractile activity, ROS production may be increased from several cellular sites such as the mitochondrial respiratory chain, NADPH oxidases, and activated phagocytes (22, 25) and also potentially from xanthine oxidase (XO) enzymes. XO and xanthine dehydrogenase (XDH) are isoenzymes of xanthine oxidoreductase, which catalyzes the oxidation of hypoxanthine and xanthine to urate during purine catabolism in mammals. Although XDH preferentially transfers the electrons released during the oxidation process to NAD+, XO utilizes molecular oxygen, thereby generating superoxide anion (17). Treatment with allopurinol or its active metabolite oxypurinol, which blocks XO activity by binding at its active site (55), has been associated with a decrease in the levels of indicators of oxidative damage and markers of muscle damage after exhaustive exercise protocols in humans and rats (14, 16).

Detection of ROS in biological systems is difficult, since these species occur at very low concentrations and react rapidly with cellular components close to their sites of formation, thus having little capacity to accumulate. Since the primary ROS generated by skeletal muscle (superoxide and NO) are found close to their site of synthesis, an assay system that is designed to measure specific primary ROS must have access to this site. One technique that permits this in the interstitial space of tissues is microdialysis (37). We previously used this technique to monitor the extracellular activity of superoxide anion in muscle interstitial space during a protocol of isometric contractile activity (9, 34).

The aim of the present study was to examine the role of XO activity in the contraction-induced increase in superoxide anion detected in the extracellular fluid of mouse skeletal muscle. Having established that XO activity contributes to the contraction-induced increase in extracellular superoxide anion, further studies were undertaken to determine the effects of inhibition of superoxide generation by XO or scavenging of extracellular superoxide on the contractile properties of skeletal muscle.

METHODS

In Vivo Studies

Mice and drug administration.

In the first series of experiments, adult (3 mo old, 30 g body wt) male C57BL/6 mice were randomly divided into three experimental groups that were intravenously injected with 0.2 ml of saline (n = 12), 0.2 ml of vehicle (n = 10), or 0.2 ml of oxypurinol (0.67 mM, n = 12). The vehicle for oxypurinol contained 25 mM NaOH and 92.5 mM NaHCO3 at pH 7.4 (39). Mice were anesthetized with pentobarbitone sodium (7.3 mg/100 g ip). Supplemental doses of anesthetic were administered as required to maintain deep anesthesia, such that mice were not responsive to tactile stimuli throughout the procedure. The drug treatments were administered by intravenous tail vein injection when the mice were fully anesthetized. At 30 min after induction of anesthesia, a microdialysis probe (MAB 3.35.4, Metalant, Stockholm, Sweden), with a molecular mass cutoff of 35 kDa, was placed into the gastrocnemius muscle of the right hindlimb.

These studies were approved by the University of Liverpool animal ethics committee and were performed under UK Home Office guidelines under the UK Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986.

Microdialysis studies.

The microdialysis probes were perfused with 50 μM cytochrome c in saline at a flow rate of 4 μl/min (9). Microdialysates were collected every 15 min, resulting in a total of 60 μl of dialysate per collection. After four 15-min baseline collections, the right hindlimb of the anesthetized mouse was subjected to a 15-min period of isometric contractions by electrical stimulation using surface electrodes placed around the upper limb and ankle, as previously described (9, 34). In most experiments, the mouse muscles were stimulated for 15 min with 0.1-ms square-wave pulses at 100 Hz and 30 V for 0.5 s every 5 s (34); in a limited number of experiments, the effect of a protocol of lower-frequency stimulations was examined (0.1-ms square-wave pulses at 59 Hz and 30 V for 0.5 s every 5 s). After the period of contractions, two further 15-min collections of microdialysates were undertaken with the muscles at rest. Mice remained under anesthesia until the end of the experiment and then killed by an overdose of pentobarbitone sodium. Gastrocnemius and liver samples were rapidly dissected, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until analysis.

Measurement of extracellular superoxide.

The reduction of cytochrome c was analyzed by spectrophotometry, as previously described (9, 34). Briefly, cytochrome c samples were diluted 1:5 with distilled water and analyzed using scanning visible spectroscopy. The reduction of cytochrome c was calculated from absorbance at 550 nm compared with absorbance at the isosbestic wavelength of 542 nm. Results are expressed as superoxide equivalents, with a molar extinction coefficient for reduced cytochrome c of 21,000 (9).

Muscle force-frequency relationship.

The force-frequency relationship for extensor digitorum longus (EDL) muscles was analyzed as previously described (27). Mice were anesthetized as previously described, and the knee of the right hindlimb was fixed. The distal tendon of the EDL muscle was exposed and attached to the lever arm of a servomotor (Cambridge Technology). The peroneal nerve was exposed, and stainless steel needle electrodes were placed across the nerve. Stimulation voltage and muscle length were adjusted to produce a maximum twitch force. The muscle length that produced the maximum twitch force is also the optimum muscle length (Lo) for the production of maximum tetanic force (Po). The muscle was electrically stimulated to contract at Lo and optimal stimulation voltage (8–10 V) every 2 min for a total of 500 ms with 0.2-ms pulse width. The frequency of stimulation was increased for each 500-ms stimulus from 10 to 50 Hz and, subsequently, in 50-Hz increments to a maximum of 400 Hz.

In Vitro Studies

In the second series of experiments, adult (3-mo-old) male C57BL/6 mice were killed with an overdose of pentobarbitone sodium, and soleus and EDL muscles were rapidly removed from both limbs in random order. The muscles were mounted at constant length in a tissue bath containing oxygenated, mammalian Ringer solution (mM: 137 NaCl, 5 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgSO4, 1 NaH2PO4, 24 NaHCO3, and 0.025 tubocurarine chloride). The solution was gassed continually with 95% O2-5% CO2 throughout the experiment. Temperature was maintained at 37°C. Muscles were randomly divided into three experimental groups: control with no additions (n = 10), incubated with oxypurinol (final concentration 0.67 mM, n = 10), and incubated with polyethylene glycol-tagged Cu,Zn-SOD (PEG-SOD, final activity 500 U/ml, n = 10). Oxypurinol and PEG-SOD were obtained from Sigma Chemical (Poole, Dorset, UK) and prepared daily in mammalian Ringer solution.

Muscle contractile properties.

The preparation and experimental conditions used for in vitro study of soleus and EDL muscles have been described previously (48). After 1 h of preincubation with oxypurinol (14) or 30 min of preincubation with PEG-SOD (44), Lo for peak twitch force was established for the isolated muscles. All subsequent measurements were made at Lo. Muscles were electrically stimulated between two platinum electrodes with 0.1-ms square-wave pulses of supramaximal voltage. Force production was monitored with a force transducer (Linton Instrumentation) coupled to a storage oscilloscope (type 1425, Gould). Contractile characteristics, including time to peak twitch, twitch half-relaxation time, and peak twitch force were measured. Stimulation frequency was increased in EDL and soleus muscles until Po was obtained; muscles were rested for 2 min between each of these contractions (48). Before a fatigue test, each muscle was rested for 5 min after measurement of Po.

To allow expression of Po as maximum specific tension (N/cm2), the weight and length of each muscle were measured at the end of each experiment, and muscle cross-sectional area was calculated (48).

Fatigue protocol.

Soleus and EDL muscles were electrically stimulated for 5 min with 0.1-ms square-wave pulses at 40 Hz and 60 V for 0.1 s every 5 s. The force generated was measured throughout the fatiguing protocol. At 2 min after the end of the protocol of repeated stimulations, the muscles were electrically stimulated with a single stimulus, and force generation was measured again for calculation of percent recovery (26).

Measurement of XO activity.

XO activity was determined fluorometrically (5). Frozen liver tissue (0.2 g/ml) was homogenized in 0.25 M sucrose, 10 mM DTT, 0.2 mM PMSF, 0.1 mM EDTA, and 50 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.4. Homogenates were centrifuged for 30 min at 15,000 g, and activities were measured in supernatants. The reaction was initiated by addition of pterin (0.010 mmol/l) as a substrate, and XO activity was obtained from the rate of increase in fluorescence due to the conversion of pterin to isoxanthopterin. The reaction was stopped by addition of allopurinol (50 μmol/l). For calibration of the assay, the fluorescence of a standard concentration of isoxanthopterin was measured. Protein concentration of homogenates was determined by the Bradford assay (6).

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were carried out using the Statistical Package (SPSS version 11.01). All data are presented as means ± SE. A one-way repeated-measures ANOVA was used to analyze the effects of the contraction protocol on the reduction of cytochrome c. A mixed-design factorial ANOVA was used to examine the effects of the ROS inhibitors. When Mauchley's test of sphericity indicated a minimum level of violation (Greenhouse-Geisser ε >0.75), data were corrected using the Huynh-Feldt ε; however, when sphericity was deemed to be violated (Greenhouse-Geisser ε <0.75), data were corrected using the Greenhouse-Geisser ε. Where a significant F value was observed, Tukey's honestly significantly difference post hoc analysis was performed to identify where the significant differences occurred. Statistical significance was set at 0.05 for all the tests.

RESULTS

Superoxide Anion in Muscle Extracellular Space: Effect of Oxypurinol Administration

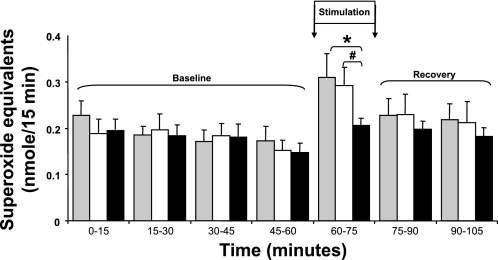

The changes in cytochrome c reduction (presented as superoxide equivalents) in microdialysates from resting and contracting muscle from control mice, mice given an intravenous injection of vehicle, and mice treated with oxypurinol are shown in Fig. 1. The protocol of 180 isometric contractions induced a significant increase in cytochrome c reduction in microdialysates from the mice given saline or vehicle, but prior injection of mice with oxypurinol prevented this contraction-induced increase in the reduction of cytochrome c. XO activity was determined in the liver tissue of mice, since XO activity is known to be high in this tissue (21). Liver XO activity decreased significantly from 2,058.6 ± 388.3 and 1,926.3 ± 356.1 mU/g protein in the saline- and vehicle-treated mice, respectively, to 94.3 ± 36.8 mU/g protein in the oxypurinol-treated mice (n = 6, P < 0.01).

Fig. 1.

Reduction of cytochrome c in microdialysates from gastrocnemius muscle of control, saline-treated mice (gray bars, n = 12), mice treated with vehicle (open bars, n = 10), and mice treated with oxypurinol (solid bars, n = 12). Muscles were stimulated to contract at 60–75 min (Stimulation). Values are means ± SE. *P < 0.05 vs. saline at the same time point. #P < 0.05 vs. vehicle at the same time point.

Effect of Treatment With Oxypurinol or PEG-SOD on Contractile Properties of EDL and Soleus Muscles

Table 1 shows the effect of incubation of EDL or soleus muscles with oxypurinol or PEG-SOD on the maximum tetanic force generated by EDL and soleus muscles. Treatment with oxypurinol caused a significant reduction in the maximum force generation by EDL and soleus muscles. Incubation with PEG-SOD caused a significant reduction in maximum force generation for EDL muscle but had no effect on soleus force generation. Oxypurinol and PEG-SOD treatments significantly reduced the peak twitch force generation by the EDL muscle (data not shown in detail).

Table 1.

Effect of oxypurinol and PEG-SOD on Po generated by EDL and soleus muscles

| Po, mN |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxypurinol |

PEG-SOD |

|||

| Control (n = 9) | Oxypurinol (n = 9) | Control (n = 10) | PEG-SOD (n = 10) | |

| EDL | 381.0±51.0 | 241.8±28.5* | 304.5±43.5 | 201.0±39.6* |

| Soleus | 247.0±39.0 | 163.2±19.2* | 203.7±25.2 | 197.1±20.1 |

Values are means ± SE; n, number of muscles. Control muscles were incubated in mammalian Ringer solution for a period of time equivalent to that of the corresponding test muscles [30 min for polyethylene glycol-tagged Cu,Zn-SOD (PEG-SOD)-treated muscles and 60 min for oxypurinol-treated muscles] before measurement of maximum tetanic force (Po) production. EDL, extensor digitorum longus.

P < 0.05 vs. corresponding control.

Effect of Treatment With Oxypurinol or SOD on Fatigue and Recovery From Fatigue in EDL and Soleus Muscles

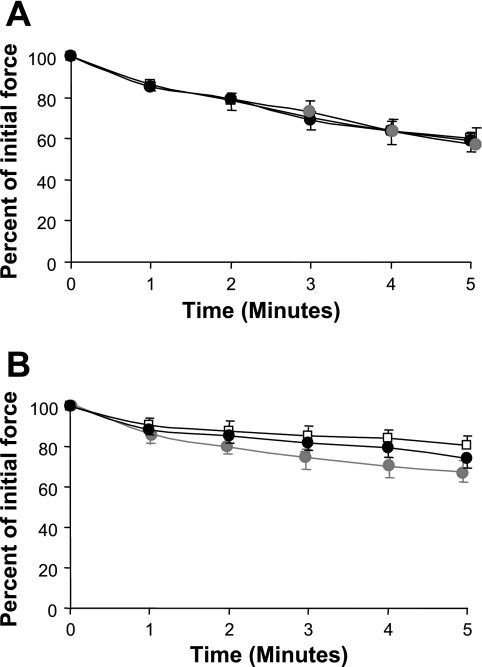

Figure 2 shows the loss of force generation by EDL and soleus muscles over time during repetitive tetanic contractions at 40 Hz. EDL muscles lost a greater proportion of force over 5 min of repeated stimulations than soleus muscles, but the loss of force generation in EDL or soleus muscles was unaffected by exposure to oxypurinol or PEG-SOD. Similarly, neither agent significantly affected the recovery of force at 2 min following contractions (data not shown in detail).

Fig. 2.

Force production by extensor digitorum longus (A) and soleus (B) muscles incubated in mammalian Ringer solution alone (open symbols, n = 9), oxypurinol (solid symbols, n = 9), and polyethylene glycol-tagged Cu,Zn-SOD (gray symbols, n = 10) during a 5-min fatigue protocol. Values are means ± SE. No significant differences were seen between the different groups of muscles.

Effect of Reduced Muscle Force Generation on Contraction-Induced Generation of Superoxide Anion

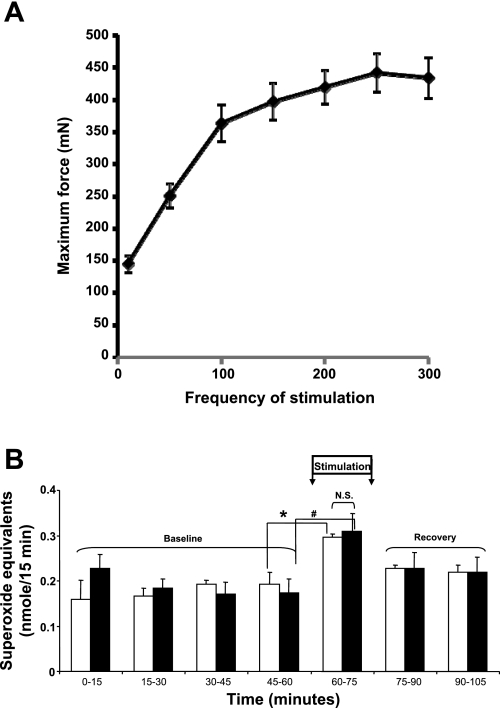

The data presented in Fig. 1 and Table 1 show that exposure of muscle to oxypurinol induced a significant depression in maximum tetanic force generation by EDL and soleus muscles and a reduction in contraction-induced extracellular superoxide anion. It appeared feasible that the effect of oxypurinol to reduce muscle force generation may have been responsible for the reduced superoxide release, rather than any direct effect of oxypurinol on XO activity reducing superoxide release. To examine this possibility, we examined the force-frequency curve for untreated EDL muscles (Fig. 3A) and calculated the stimulation frequency required to produce a force equivalent to that seen in the oxypurinol-treated muscles. A reduction in stimulation frequency to 59 Hz was calculated to generate force equivalent to that achieved at 100 Hz in muscles from oxypurinol-treated mice. The data in Fig. 3B show that the increase in extracellular superoxide anion was unaffected by the frequency of stimulation and, hence, force generation.

Fig. 3.

A: force-frequency relationship for mouse extensor digitorum longus muscles. B: reduction of cytochrome c in microdialysates from gastrocnemius muscle of control mice. Muscles were stimulated to contract at 60–75 min (Stimulation) with a protocol of electrical stimuli at 100 Hz (solid bars) or 59 Hz (open bars). Values are means ± SE (n = 4). *P < 0.05 vs. values obtained immediately before contractile activity (45–60 min). #P < 0.05 vs. values obtained immediately before contractile activity (45–60 min). No differences were seen between reduction in cytochrome c with the two different stimulation protocols. NS, not significant.

DISCUSSION

Role of XO in Superoxide Generation During Muscle Contraction

Hellsten et al. (18) first showed that XO is an important source of ROS generation during exercise and demonstrated that a chronic exercise protocol increased XO activity in human muscle. The enzyme was found to be present mainly in microvascular endothelial cells and infiltrating leukocytes (19). It was subsequently demonstrated that plasma XO activities were higher in rats exercised to exhaustion than in control nonexercised rats (14), and a linear correlation between plasma XO activity and lactate concentration in exercised rats has been described (40). Allopurinol-induced inhibition of XO was also found to reduce markers of muscle damage associated with exhaustive exercise in rats (56) and humans (16), and XO-derived ROS were shown to be important in activating signaling pathways involved in muscle adaptations to exercise (14, 25).

In the present study, the role of XO in superoxide generation in the extracellular space of skeletal muscle in vivo has been examined. The effect of a nondamaging contraction protocol on the reduction of cytochrome c in microdialysates obtained from the gastrocnemius muscle extracellular space has been studied as a measure of net superoxide activity during a contraction protocol. The specificity of this assay for superoxide in muscle dialysates has been confirmed by Close et al. (9). Figure 1 shows that intravenous injection of oxypurinol prevented the contraction-induced increase in the reduction of cytochrome c in skeletal muscle microdialysates. Our results are consistent with data from Stofan et al. (52), who reported a partial reduction in superoxide anion release from the contracting diaphragm treated with oxypurinol. Matuszczak and colleagues (33) also showed a reduction in ROS formation in the cytosol of soleus muscles from allopurinol-treated mice. In addition to the ability to inhibit XO, allopurinol and oxypurinol have weak hydroxyl radical scavenging properties at higher concentrations than those used here (36). Hence, our data support the theory that XO is involved in superoxide radical release into the extracellular fluid during a nondamaging protocol of muscle contractions.

Release of superoxide from cultured muscle cells has been reported (34), but the data presented here suggest that the superoxide responsible for extracellular cytochrome c reduction may also be derived from XO activity in the endothelium of skeletal muscle. It has been suggested that muscle contraction alters the shear stresses applied to the vascular bed of the muscle and that this latter stimulus induces superoxide formation and release (52). Multiple free radical-generating pathways have been reported in skeletal muscle (22), and the present data argue that the XO pathway is important in superoxide formation in the extracellular fluid after a nondamaging protocol of muscle contractions in addition to the acknowledged activity of XO during and after tissue ischemia.

Reduction of Superoxide Anion in the Extracellular Space and Muscle Force Generation in Nonfatigued Muscles

Contractile activity of skeletal muscle may lead to oxidation of many biomolecules, indicated by altered muscle and blood glutathione levels and an increase in protein, DNA, and lipid oxidation (41, 47). Several studies have examined whether increasing the intracellular levels of antioxidants within a muscle cell can provide protection against oxidation and reduce muscle fatigue (49), but Reid and co-workers (44) also demonstrated that, in nonfatigued skeletal muscle, ROS appear to have a positive effect on excitation-contraction coupling and are obligatory for optimal contractile function. Specifically, they demonstrated that addition of catalase and SOD resulted in a diminished in vitro muscle contractile performance in unfatigued muscle (44). Furthermore, addition of strong synthetic reducing agents or antioxidants such as DTT (2), N-acetylcysteine (29), and DMSO (45, 46) to skeletal muscle in an organ bath resulted in a reduction in skeletal muscle force production. These data have been supported by other studies where exposure to an ROS-generating system (XO and hypoxanthine) or hydrogen peroxide resulted in an increase in low-frequency-stimulated force generation by the nonfatigued diaphragm (44). The data in Table 1 show that prevention of superoxide generation by inhibition of XO activity depressed skeletal muscle force production in EDL and soleus muscles. Maximum tetanic force generation by EDL muscles was depressed by ∼57% and in soleus muscle by ∼38% after incubation with oxypurinol. Incubation of the muscles with PEG-SOD (Table 1) caused a 34% decrease in tetanic force generation by EDL muscles but had no effect on force generation by soleus muscles. Although these data may suggest that PEG-SOD is more effective in preventing superoxide-induced effects on muscle force production in type II fibers, they may also reflect an inability of the added PEG-SOD to compete for superoxide in the presence of other potential reactants such as NO, the concentrations of these reactants may vary between different muscle types.

Other workers have studied the effect of antioxidants on force generation by skeletal muscle and demonstrated a reduction in submaximal force generation of nonfatigued muscle at low frequencies of stimulation, but no similar effects on maximal tetanic force generation have been reported, except where very high (and potentially toxic) concentrations of antioxidants were used (8, 29, 42, 44). It is not immediately clear why the data reported here differ from those previously reported, but the published data are derived from multiple models and none are identical to the model studied here. In particular, there are differences in the muscle type (diaphragm, gastrocnemius, EDL, or soleus muscles), the species (rats, mice, or dogs), the nature and concentration of the antioxidant, and the temperature and incubation periods. Thus a variety of factors may have contributed to the different effects.

The temperature and the duration of the incubation period may be important aspects. Thus, in the present study, mouse muscle was studied at 37°C, whereas some previous data were obtained at lower temperatures. Muscle-derived ROS activities have been reported to be diminished at room temperature (3), and antioxidants that inhibit fatigue at 37°C have been reported to have no effect at 23°C (13). Our experimental model utilized an extended duration of exposure of the muscle to antioxidants at 37°C compared with most other studies.

Variations in the concentrations of antioxidant used might also explain some of the differences observed in our study. There is no consensus regarding the concentration of oxypurinol necessary to inhibit XO in skeletal muscle, but our protocol differs from that used by other authors. In the present experiments, the muscles were incubated with 0.67 mM oxypurinol, which was observed previously to inhibit XO activity in rats (39). We also determined the XO activity in the present study and found a significant decrease after this protocol of administration. In comparison, Stofan et al. (52) injected rats with oxypurinol (50 mg/kg ip) 12 h before the study, and an additional dose of oxypurinol (50 mg/l) was added to the diaphragmatic perfusate used during the in vitro experiments. These authors did not measure the XO activity. Supinski and colleagues (54) examined fatigue and free radical-mediated lipid peroxidation in the rat diaphragm during loaded breathing by administration of oxypurinol and showed no effect of oxypurinol on maximal diaphragm force generation in an in situ diaphragm preparation. Oxypurinol (50 mg/kg) was again administered on the day before the study, and an additional 50 mg/kg was given after 30 min of equilibration of the in situ model. The effects of allopurinol were also studied by Barclay and Hansel (4), who used in vitro and in situ models to examine mouse soleus and canine gastrocnemius-plantaris preparations. In the canine experiments, the authors determined the effect of 1 mM allopurinol on the fatigue rate of blood-perfused canine gastrocnemius in situ but saw no significant effect of allopurinol. In a later study, Matuszczak et al. (33) gave allopurinol to mice (50 mg·kg−1·day−1) and also observed no loss of maximum force generation by the soleus muscle. For studies of PEG-SOD, we examined the effect of 500 U/l on isolated muscles, whereas Callahan and colleagues (8) gave PEG-SOD by intraperitoneal injection at 2,000 U/kg to rats and also incubated skinned muscle fibers isolated from the diaphragm with 2,000 U/l PEG-SOD. Callahan et al. did not observe an effect on maximum tetanic force generation with either treatment protocol.

The loss of contractile function that was observed after exposure to oxypurinol in electrically stimulated EDL and soleus muscles or PEG-SOD in EDL muscles suggests that these agents alter processes within the intact muscle cell. In this study, any intracellular effect of the SOD is likely to have been indirect, because the molecular mass of PEG-SOD restricts it to extracellular distribution. XO is located in the skeletal muscle endothelium. Reid and colleagues (44) examined how addition of SOD and catalase to the extracellular medium might influence intracellular processes mediated by ROS. They proposed that the enzyme substrates hydrogen peroxide and superoxide anions can cross cell membranes; hence, their rapid removal by exogenous enzymes would establish an extracellular “sink” for these endogenous oxidants, maintaining a gradient for diffusion from the cytosol and preventing diffusion back into the cell. In support of this postulate, the present study has shown that nonfatigued muscles release superoxide to the extracellular fluid and that incubation with oxypurinol or PEG-SOD (9) lowered the extracellular superoxide. Other research groups have shown that incubation of nonfatigued muscles with SOD or catalase lowered the activities of ROS measured in the muscle cytosol by a nonspecific indicator (42).

The mechanisms involved in the modulation of force generation by ROS are not fully established, but published data indicate that the variation of force in response to shifts in the redox balance may be mediated by changes in myofibrillar calcium sensitivity (2) and/or a reduction in calcium release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (1, 57). The proteins that determine the calcium sensitivity of the contractile process are troponin and the regulatory myosin light chain (7, 35). It is also possible that superoxide generated during contractile activity acts to decrease NO bioavailability in untreated muscles; hence, when superoxide generation is inhibited by oxypurinol or SOD, NO bioavailability is increased, with beneficial effects on contractile function. To test this possibility, we used the microdialysis technique to determine the NO levels in muscle extracellular space during the contractile protocol, but treatment with oxypurinol had no effect on microdialysate NO levels (data not shown in detail).

Reduction of Superoxide Anion in the Extracellular Space and Force Generation in Muscles Subjected to Repeated Stimulation of Contractions

Muscle contractions increase ROS production, and it has been suggested that the increased generation of these species influences the intracellular redox state to induce a more oxidizing environment. Furthermore, these perturbations may result in oxidative modifications in contractile proteins that depress contractile function. In previous studies, SOD and catalase and other agents that reduce ROS (N-acetylcysteine, DMSO, DTT, allopurinol, and desferoxamine) have been reported to slow the loss of contractile force that occurs during repeated electrical stimulation of contractions in muscle preparations in vitro and in situ (4, 49, 53). These findings have not been universally observed: Shrier et al. (50) reported no effect of SOD, PEG-conjugated catalase, or desferoxamine on skeletal muscle fatigue. To explain these contradictory results, Reid et al. (42) proposed that the effects of ROS scavengers depend on the fatigue protocol used and that fatigue is delayed by these agents during contractile protocols using submaximal activation patterns but not when contraction is at maximal or near-maximal intensities (42). These authors suggested that low-frequency fatigue in vitro mimics the metabolic changes produced by peripheral fatigue in vivo: glycogen stores and phosphocreatine levels are depleted, intracellular pH falls, and Pi levels rise. Acidosis and increased Pi each inhibit actin-myosin interaction, precipitating contractile failure, and this type of fatigue is also associated with oxidative stress (51). In contrast, high-frequency fatigue was attributed to failure of impulse propagation across the sarcolemma; force declines rapidly under these conditions and recovers within seconds to minutes after the end of contractions. Previous work indicates that this latter form of fatigue is not mediated by ROS intermediates (42). Our data show that prevention of the contraction-induced formation of superoxide anions in the muscle extracellular space with the administration of oxypurinol or scavenging of the extracellular superoxide with PEG-SOD did not prevent the loss of muscle force generation that occurs with repeated stimulation at 40 Hz for 0.1 s every 5 s.

We also examined the possibility that the decreased generation of force by muscle after treatment with oxypurinol might account for the decrease in extracellular superoxide anion produced by the contracting muscle. Control muscles were electrically stimulated with a decreased stimulation frequency that produced a force generation equivalent to that in the oxypurinol-treated group, but no differences in the stimulation-induced increase in cytochrome c reduction were seen between the two stimulation protocols (Fig. 3). Some previous data also indicate that the release of superoxide from muscle cells is activated by contractions but not directly related to the frequency of stimulation (38), and the present data are in general agreement with this.

Perspectives and Significance

We conclude that XO is a source of the elevated superoxide anion detected in skeletal muscle extracellular space during nondamaging contractions, since intravenous administration of oxypurinol prevented the contraction-induced increase in cytochrome c reduction in microdialysates from the gastrocnemius muscle. Selective inhibition of XO-induced superoxide generation by treatment with oxypurinol also caused a significant decrease in the maximum tetanic force generated by EDL or soleus muscles. Similar data were obtained after treatment of EDL muscles with PEG-SOD. Despite the decreased force generation by nonfatigued, oxypurinol-treated muscles compared with untreated controls, neither pretreatment with PEG-SOD nor pretreatment with oxypurinol delayed the development of fatigue in soleus and EDL muscles subjected to repeated stimulation over 5 min. There has been considerable debate about whether XDH and/or oxidase enzymes are as abundant in human muscle as in rodent tissue, but the enzymes are acknowledged to be present in endothelial cells from humans and rodent models (18, 19). The efficacy of allopurinol against muscle damage in some models of exercise-induced muscle damage in humans (16) indicates that even if the enzyme location is limited to endothelial cells in humans, they are able to influence human muscle function. A number of studies have recently suggested that dietary supplementation with agents that prevent ROS formation or scavenge these species does not improve, or may reduce, exercise performance (11, 15, 30–32), and the data presented here indicating a positive effect of XO-derived superoxide anions on muscle force generation are in agreement with these studies.

GRANTS

The authors thank the Wellcome Trust (Grant 073263/Z/03) for financial support.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interests are declared by the author(s).

REFERENCES

- 1.Abramson JJ, Salama G. Critical sulfhydryls regulate calcium release from sarcoplasmic reticulum. J Bioenerg Biomembr 21: 283– 294, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andrade FH, Reid MB, Allen DG, Westerblad H. Effect of hydrogen peroxide and dithiothreitol on contractile function of single skeletal muscle fibres from the mouse. J Physiol 509: 565– 575, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arbogast S, Reid MB. Oxidant activity in skeletal muscle fibers is influenced by temperature, CO2 level, and muscle-derived nitric oxide. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 287: R698– R705, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barclay JK, Hansel M. Free radicals may contribute to oxidative skeletal muscle fatigue. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 69: 279– 284, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beckman JS, Parks DA, Pearson JD, Marshall PA, Freeman BA. A sensitive fluorometric assay for measuring xanthine dehydrogenase and oxidase in tissues. Free Radic Biol Med 6: 607– 615, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem 72: 248– 254, 1976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brenner B. Effect of Ca2+ on cross-bridge turnover kinetics in skinned single rabbit psoas fibers: implications for regulation of muscle contraction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 85: 3265– 3269, 1988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Callahan LA, Nethery D, Stofan D, DiMarco A, Supinski G. Free radical-induced contractile protein dysfunction in endotoxin-induced sepsis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 24: 210– 217, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Close GL, Ashton T, McArdle A, Jackson MJ. Microdialysis studies of extracellular reactive oxygen species in skeletal muscle: factors influencing the reduction of cytochrome c and hydroxylation of salicylate. Free Radic Biol Med 39: 1460– 1467, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Commoner B, Townsend J, Pake GE. Free radicals in biological materials. Nature 174: 689– 691, 1954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coombes JS, Powers SK, Rowell B, Hamilton KL, Dodd SL, Shanely RA, Sen CK, Packer L. Effects of vitamin E and α-lipoic acid on skeletal muscle contractile properties. J Appl Physiol 90: 1424– 1430, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davies KJ, Quintanilha AT, Brooks GA, Packer L. Free radicals and tissue damage produced by exercise. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 107: 1198– 1205, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diaz PT, Brownstein E, Clanton TL. Effects of N-acetylcysteine on in vitro diaphragm function are temperature dependent. J Appl Physiol 77: 2434– 2439, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gomez-Cabrera MC, Borras C, Pallardo FV, Sastre J, Ji LL, Vina J. Decreasing xanthine oxidase-mediated oxidative stress prevents useful cellular adaptations to exercise in rats. J Physiol 567: 113– 120, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gomez-Cabrera MC, Domenech E, Romagnoli M, Arduini A, Borras C, Pallardo FV, Sastre J, Vina J. Oral administration of vitamin C decreases muscle mitochondrial biogenesis and hampers training-induced adaptations in endurance performance. Am J Clin Nutr 87: 142– 149, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gomez-Cabrera MC, Pallardo FV, Sastre J, Vina J, Garcia-del-Moral L. Allopurinol and markers of muscle damage among participants in the Tour de France. JAMA 289: 2503– 2504, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harris CM, Sanders SA, Massey V. Role of the flavin midpoint potential and NAD binding in determining NAD versus oxygen reactivity of xanthine oxidoreductase. J Biol Chem 274: 4561– 4569, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hellsten Y, Ahlborg G, Jensen-Urstad M, Sjodin B. Indication of in vivo xanthine oxidase activity in human skeletal muscle during exercise. Acta Physiol Scand 134: 159– 160, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hellsten Y, Frandsen U, Orthenblad N, Sjodin B, Richter EA. Xanthine oxidase in human skeletal muscle following eccentric exercise: a role in inflammation. J Physiol 498: 239– 248, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hollander J, Fiebig R, Gore M, Ookawara T, Ohno H, Ji LL. Superoxide dismutase gene expression is activated by a single bout of exercise in rat skeletal muscle. Pflügers Arch 442: 426– 434, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huh K, Yamamoto I, Gohda E, Iwata H. Tissue distribution and characteristics of xanthine oxidase and allopurinol oxidizing enzyme. Jpn J Pharmacol 26: 719– 724, 1976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jackson MJ. Free radicals generated by contracting muscle: by-products of metabolism or key regulators of muscle function? Free Radic Biol Med 44: 132– 141, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jackson MJ. Free radicals in skin and muscle: damaging agents or signals for adaptation? Proc Nutr Soc 58: 673– 676, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jackson MJ, Edwards RH, Symons MC. Electron spin resonance studies of intact mammalian skeletal muscle. Biochim Biophys Acta 847: 185– 190, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ji LL, Gomez-Cabrera MC, Steinhafel N, Vina J. Acute exercise activates nuclear factor (NF)-κB signaling pathway in rat skeletal muscle. FASEB J 18: 1499– 1506, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones DA, Howell S, Roussos C, Edwards RH. Low-frequency fatigue in isolated skeletal muscles and the effects of methylxanthines. Clin Sci (Lond) 63: 161– 167, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kayani AC, Close GL, Jackson MJ, McArdle A. Prolonged treadmill training increases HSP70 in skeletal muscle but does not affect age-related functional deficits. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 294: R568– R576, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khassaf M, McArdle A, Esanu C, Vasilaki A, McArdle F, Griffiths RD, Brodie DA, Jackson MJ. Effect of vitamin C supplements on antioxidant defence and stress proteins in human lymphocytes and skeletal muscle. J Physiol 549: 645– 652, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khawli FA, Reid MB. N-acetylcysteine depresses contractile function and inhibits fatigue of diaphragm in vitro. J Appl Physiol 77: 317– 324, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Malm C, Svensson M, Ekblom B, Sjodin B. Effects of ubiquinone-10 supplementation and high intensity training on physical performance in humans. Acta Physiol Scand 161: 379– 384, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Malm C, Svensson M, Sjoberg B, Ekblom B, Sjodin B. Supplementation with ubiquinone-10 causes cellular damage during intense exercise. Acta Physiol Scand 157: 511– 512, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marshall RJ, Scott KC, Hill RC, Lewis DD, Sundstrom D, Jones GL, Harper J. Supplemental vitamin C appears to slow racing greyhounds. J Nutr 132: 1616S– 1621S, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matuszczak Y, Arbogast S, Reid MB. Allopurinol mitigates muscle contractile dysfunction caused by hindlimb unloading in mice. Aviat Space Environ Med 75: 581– 588, 2004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McArdle A, Pattwell D, Vasilaki A, Griffiths RD, Jackson MJ. Contractile activity-induced oxidative stress: cellular origin and adaptive responses. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 280: C621– C627, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Metzger JM, Moss RL. Myosin light chain 2 modulates calcium-sensitive cross-bridge transitions in vertebrate skeletal muscle. Biophys J 63: 460– 468, 1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moorhouse PC, Grootveld M, Halliwell B, Quinlan JG, Gutteridge JM. Allopurinol and oxypurinol are hydroxyl radical scavengers. FEBS Lett 213: 23– 28, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Obata T. Use of microdialysis for in-vivo monitoring of hydroxyl free-radical generation in the rat. J Pharm Pharmacol 49: 724– 730, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pattwell DM, McArdle A, Morgan JE, Patridge TA, Jackson MJ. Release of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species from contracting skeletal muscle cells. Free Radic Biol Med 37: 1064– 1072, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pereda J, Sabater L, Cassinello N, Gomez-Cambronero L, Closa D, Folch-Puy E, Aparisi L, Calvete J, Cerda M, Lledo S, Vina J, Sastre J. Effect of simultaneous inhibition of TNF-α production and xanthine oxidase in experimental acute pancreatitis: the role of mitogen activated protein kinases. Ann Surg 240: 108– 116, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Radak Z, Asano K, Inoue M, Kizaki T, Oh-Ishi S, Suzuki K, Taniguchi N, Ohno H. Superoxide dismutase derivative reduces oxidative damage in skeletal muscle of rats during exhaustive exercise. J Appl Physiol 79: 129– 135, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Radak Z, Kaneko T, Tahara S, Nakamoto H, Ohno H, Sasvari M, Nyakas C, Goto S. The effect of exercise training on oxidative damage of lipids, proteins, and DNA in rat skeletal muscle: evidence for beneficial outcomes. Free Radic Biol Med 27: 69– 74, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reid M, Haak K, Francheck K. Reactive oxygen in skeletal muscle. I. Intracellular oxidant kinetics and fatigue in vitro. J Appl Physiol 73: 1797– 1804, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reid MB. Redox modulation of skeletal muscle contraction: what we know and what we don't. J Appl Physiol 90: 724– 731, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reid MB, Khawli FA, Moody MR. Reactive oxygen in skeletal muscle. III. Contractility of unfatigued muscle. J Appl Physiol 75: 1081– 1087, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reid MB, Moody MR. Dimethyl sulfoxide depresses skeletal muscle contractility. J Appl Physiol 76: 2186– 2190, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sams WM, Jr, Carroll NV, Crantz PL. Effect of dimethylsulfoxide on isolated-innervated skeletal, smooth, and cardiac muscle. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 122: 103– 107, 1966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sastre J, Asensi M, Gasco E, Pallardo FV, Ferrero JA, Furukawa T, Vina J. Exhaustive physical exercise causes oxidation of glutathione status in blood: prevention by antioxidant administration. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 263: R992– R995, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Segal SS, Faulkner JA. Temperature-dependent physiological stability of rat skeletal muscle in vitro. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 248: C265– C270, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shindoh A, Dimarco A, Thomas A. Effect of N-acetylcysteine on diaphragm fatigue. J Appl Physiol 68: 2107– 2113, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shrier I, Hussain S, Magder S. Failure of oxygen radical scavengers to modify fatigue in electrically stimulated muscle. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 69: 1470– 1475, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Smith MA, Reid MB. Redox modulation of contractile function in respiratory and limb skeletal muscle. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 151: 229– 241, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stofan DA, Callahan LA, Di MA, Nethery DE, Supinski GS. Modulation of release of reactive oxygen species by the contracting diaphragm. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 161: 891– 898, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Supinski G, Nethery D, Stofan D, DiMarco A. Effect of free radical scavengers on diaphragmatic fatigue. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 155: 622– 629, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Supinski G, Nethery D, Stofan D, Szweda L, DiMarco A. Oxypurinol administration fails to prevent free radical-mediated lipid peroxidation during loaded breathing. J Appl Physiol 87: 1123– 1131, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Truglio JJ, Theis K, Leimkuhler S, Rappa R, Rajagopalan KV, Kisker C. Crystal structures of the active and alloxanthine-inhibited forms of xanthine dehydrogenase from Rhodobacter capsulatus. Structure 10: 115– 125, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vina J, Gomez-Cabrera MC, Lloret A, Marquez R, Minana JB, Pallardo FV, Sastre J. Free radicals in exhaustive physical exercise: mechanism of production and protection by antioxidants. IUBMB Life 50: 271– 277, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Xiong H, Buck E, Stuart J, Pessah IN, Salama G, Abramson JJ. Rose bengal activates the Ca2+ release channel from skeletal muscle sarcoplasmic reticulum. Arch Biochem Biophys 292: 522– 528, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]