Abstract

Experimental approaches for identifying T-cell epitopes are time-consuming, costly and not applicable to the large scale screening. Computer modeling methods can help to minimize the number of experiments required, enable a systematic scanning for candidate major histocompatibility complex (MHC) binding peptides and thus speed up vaccine development. We developed a prediction system based on a novel data representation of peptide/MHC interaction and support vector machines (SVM) for prediction of peptides that promiscuously bind to multiple Human Leukocyte Antigen (HLA, human MHC) alleles belonging to a HLA supertype. Ten-fold cross-validation results showed that the overall performance of SVM models is improved in comparison to our previously published methods based on hidden Markov models (HMM) and artificial neural networks (ANN), also confirmed by blind testing. At specificity 0.90, sensitivity values of SVM models were 0.90 and 0.92 for HLA-A2 and -A3 dataset respectively. Average area under the receiver operating curve (AROC) of SVM models in blind testing are 0.89 and 0.92 for HLA-A2 and -A3 datasets. AROC of HLA-A2 and -A3 SVM models were 0.94 and 0.95, validated using a full overlapping study of 9-mer peptides from human papillomavirus type 16 E6 and E7 proteins. In addition, a large-scale experimental dataset has been used to validate HLA-A2 and -A3 SVM models. The SVM prediction models were integrated into a web-based computational system MULTIPRED1, accessible at antigen.i2r.a-star.edu.sg/multipred1/.

Keywords: T-cell epitope, Human Leukocyte Antigen supertype, Promiscuous binding peptide, Support vector machines

1. Introduction

Cellular immunity in vertebrates is mediated by T cells of the immune system which generate highly specific and lasting immune responses to pathogens (Fabbri et al., 2003). T-cell-based immune responses are mediated by antigenic peptides presented by major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules (Pamer and Cresswell, 1998; Yewdell and Bennink, 2001). Antigenic peptides bind MHC molecules and form peptide/MHC complexes. Peptide/MHC complexes shown to be recognized by T cells are called T-cell epitopes. Identifying promiscuous peptides that bind multiple Human Leukocyte Antigen (HLA, human MHC) alleles is a basis for T cell epitope mapping and epitope-based vaccine development (Berzofsky et al., 2001; Srinivasan et al., 2004a; De Groot, 2006). HLA genes are the most polymorphic human genes known (Williams, 2001), with more than 2400 allelic variants identified in the human population as of July 2006 (www.anthonynolan.org.uk/HIG/). Because of the high HLA polymorphism, identifying promiscuous peptides that bind more than one HLA allele is essential for the development of vaccines with a broad and unbiased coverage of the human population. HLA alleles that share sequence similarity and that bind largely overlapping sets of peptides define HLA supertypes (Sette and Sidney, 1999; Doytchinova et al., 2004; Lund et al., 2004). Promiscuous peptides have been reported in the context of HLA supertypes (Threlked et al., 1997; Wilson et al., 2003; Srinivasan et al., 2004b). Epitope-based vaccines show great potential in fighting infectious diseases (Sette et al., 2000; Ada, 2003; Wilson et al., 2003), and they are also investigated for control of cancers, allergy, autoimmunity, and even dementia (Alexander et al., 2002; Durrant and Ramage, 2005; Quintana and Cohen, 2005; Verhagen et al., 2005; Wisniewski and Frangione, 2005; De Groot, 2006).

Experimental validation of peptide binding to HLA molecules is time-consuming and costly, and thus not applicable to large scale screening across multiple HLA alleles. Computational methods are instrumental for systematic large-scale identification of MHC-binding peptides (Schirle et al., 2001; Brusic et al., 2004). One type of methods is structure-based approach that relies on structural conservation observed in 3D structure of peptide–MHC complexes (Schueler-Furman et al., 2000; Bui et al., 2006; Tong et al., 2006). These methods are computationally intensive, and have mainly been applied to MHC molecules with known crystal structures. Data-driven approaches include statistical methods based on experimental peptide binding measurements. These methods include binding motifs (Rammensee et al., 1993), quantitative matrices (Parker et al., 1994; Singh and Raghava, 2003; Reche and Reinherz, 2005; Peters and Sette, 2005), artificial neural networks (ANN) (Honeyman et al., 1998; Christensen et al., 2003), hidden Markov models (HMM) (Mamitsuka, 1998; Brusic et al., 2002), decision trees (Savoie et al., 1999; Segal et al., 2001), discriminant analysis (Mallios, 2001), multivariate regression (Lin et al., 2004), ensemble classifier (Xiao and Segal, 2005), support vector machines (SVM) (Donnes and Elofsson, 2002; Zhao et al., 2003; Bhasin and Raghava, 2004; Riedesel et al., 2004; Bozic et al., 2005; Liu et al., 2006; Cui et al., 2007), and biosupport vector machine which is modified from a conventional support vector machine by introducing a biobasis function so that the non-numerical attributes of amino acids can be recognized without a feature extraction process (Yang and Johnson, 2005). Recently a structure- and sequence-based method was reported, in which residue-based energy terms from the molecular dynamics simulations are used as features to train SVM prediction models for peptide/MHC class I binding (Antes et al., 2006).

SVM-based models showed higher accuracy than other prediction methods in studies of peptide binding to a single HLA molecule. We have employed SVM models with a novel data representation, which captures information of the interaction between a peptide and an HLA molecule and allows the use of a single model for prediction of peptide binding to a multiplicity of alleles that belong to a particular HLA supertype. Earlier we reported the application of HMM (Brusic et al., 2002) and ANN (Zhang et al., 2005b) for prediction of peptide binding to the HLA-A2 supertype. A web-based prediction system, MULTIPRED (Zhang et al., 2005a), was developed using HMM and ANN models. In this study we extended MULTIPRED by applying SVM models. The SVM-MULTIPRED was applied to prediction of HLA class I supertype-specific promiscuous binding peptides in the context of HLA-A2 and -A3. Extensive testing, including blind testing and 10-fold cross-validation, were performed to assess the performance of the prediction models. Validation of the models was conducted using experimental data from human papillomavirus (HPV) type 16 E6 and E7 proteins and a large-scale experimental dataset made available recently by Peters et al. (2006). The performance of the SVM models were compared with that of HMM and ANN models. MULTIPRED1 is the updated version of MULTIPRED (Zhang et al., 2005a). MULTIPRED1 is accessible at antigen.i2r.a-star.edu.sg/multipred1/.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Data and data representation

Nine-mer peptide data were extracted from the MHCPEP database (Brusic et al., 1994), published articles, and a set of HLA non-binding peptides (Brusic, V. unpublished data). The HLA-A2 supertype dataset, named as Dataset1, has 3050 peptides (664 binders and 2386 non-binders) related to 15 alleles (Table 1) of HLA-A2 supertype and the HLA-A3 supertype dataset, named Dataset2, has 2216 peptides (680 binders and 1536 non-binders) related to eight alleles (Table 2) of HLA-A3 supertype. Nine-mer peptides were used in building models because the predominant length of peptides that bind HLA-A2 and -A3 (class I) alleles is nine-amino-acid long (Rammensee et al., 1993). The datasets are available for download at antigen.i2r.a-star.edu.sg/multipred1/data.

Table 1.

Number of 9-mer peptides related to 15 HLA alleles belonging to A2 supertype in Dataset1

| HLA-A2 allele | Binders | Non-binders | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| A*0201 | 440 | 1999 | 2439 |

| A*0202 | 45 | 25 | 70 |

| A*0203 | 46 | 7 | 53 |

| A*0204 | 23 | 224 | 247 |

| A*0205 | 16 | 40 | 56 |

| A*0206 | 43 | 37 | 80 |

| A*0207 | 4 | 11 | 15 |

| A*0208 | 0 | 4 | 4 |

| A*0209 | 5 | 1 | 6 |

| A*0210 | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| A*0211 | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| A*0214 | 8 | 1 | 9 |

| A*0217 | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| A*6802 | 23 | 31 | 54 |

| A*6901 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Total | 664 | 2386 | 3050 |

Table 2.

Number of 9-mer peptides related to eight HLA alleles belonging to A3 supertype in Dataset2

| HLA-A3 allele | Binders | Non-binders | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| A*0301 | 107 | 89 | 196 |

| A*0302 | 146 | 259 | 405 |

| A*1101 | 142 | 223 | 365 |

| A*1102 | 142 | 211 | 353 |

| A*3101 | 44 | 54 | 98 |

| A*3301 | 35 | 62 | 97 |

| A*3303 | 5 | 0 | 5 |

| A*6801 | 59 | 638 | 697 |

| Total | 680 | 1536 | 2216 |

To model the interaction between a peptide and a HLA molecule, a peptide/HLA interaction is represented by a virtual peptide composed of peptide residues and HLA residues that come in contact with the peptide (Zhang et al., 2005b). The HLA protein sequences were extracted from the IMGT/HLA Sequence Database, release 2.4.0 (http://www.anthonynolan.org.uk/HIG/). To simplify the data representation and eliminate redundant information, we considered only those contact residues that vary across the HLA-A2/A3 alleles appearing in Dataset1/Dataset2, and discarded the residues that are conserved across those HLA-A2/A3 alleles. The contact residues conserve across the alleles will not provide any useful information to feature vectors, as they are same in all feature vectors. There are in total 48 peptide contact residues of which 29 are non-conserved across HLA-A variants (Chelvanayagam, 1996; Brusic et al., 2002). Of 29 non-conserved residues, 12 are non-conserved across the 15 HLA-A2 alleles, see Table 3. By combining the 9-mer peptide and the 12 non-conserved contact residues we defined a virtual peptide. The virtual peptide has 21 amino acids capturing the interaction information between a peptide and a HLA-A2 allele: P1-P2-P3-P4-P5-P6-P7-P8-P9-R9-R62-R63-R66-R70-R73-R74-R95-R97-R99-R152-R156. P denotes peptide residues and R denotes HLA-A contact residues. Of the 29 non-conserved residues, 12 are non-conserved across the eight HLA-A3 alleles, see Table 4. There are 20 amino acids and each of them can be encoded as a binary string of length 20 with a unique position set to “1” and other positions set to “0”. For example, the first two amino acids, alanine (A) and cysteine (C) are encoded by 10000000000000000000 and 01000000000000000000 respectively, and the last amino acid tyrosine (Y) is encoded by 00000000000000000001. A 21-amino-acid-long peptide can be represented as a binary string of length 420.

Table 3.

Non-conserved contact residues across the 15 HLA-A2 alleles appearing in Dataset1

| Positions | 9 | 62 | 63 | 66 | 70 | 73 | 74 | 95 | 97 | 99 | 152 | 156 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A*0201 | F | G | E | K | H | T | H | V | R | Y | V | L |

| A*0202 | F | G | E | K | H | T | H | L | R | Y | V | W |

| A*0203 | F | G | E | K | H | T | H | V | R | Y | E | W |

| A*0204 | F | G | E | K | H | T | H | V | M | Y | V | L |

| A*0205 | Y | G | E | K | H | T | H | L | R | Y | V | W |

| A*0206 | Y | G | E | K | H | T | H | V | R | Y | V | L |

| A*0207 | F | G | E | K | H | T | H | V | R | C | V | L |

| A*0208 | Y | G | E | N | H | T | H | L | R | Y | V | W |

| A*0209 | F | G | E | K | H | T | H | V | R | Y | V | L |

| A*0210 | Y | G | E | K | H | T | H | V | R | F | V | L |

| A*0211 | F | G | E | K | H | I | D | V | R | Y | V | L |

| A*0214 | Y | G | E | K | H | T | H | L | R | Y | V | L |

| A*0217 | F | G | E | K | H | T | H | L | M | F | V | L |

| A*6802 | Y | R | N | N | Q | T | D | I | R | Y | V | W |

| A*6901 | Y | R | N | N | Q | T | D | V | R | Y | V | L |

Table 4.

Non-conserved contact residues across the eight HLA-A3 alleles appearing in Dataset2

| Positions | 9 | 62 | 63 | 70 | 73 | 97 | 114 | 142 | 152 | 156 | 163 | 171 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A*0301 | F | Q | E | Q | T | I | R | I | E | L | T | Y |

| A*0302 | F | Q | E | Q | T | I | R | I | V | Q | T | Y |

| A*1101 | Y | Q | E | Q | T | I | R | I | A | Q | R | Y |

| A*1102 | Y | Q | E | Q | T | I | R | I | A | Q | R | Y |

| A*3101 | T | Q | E | H | I | M | Q | I | V | L | T | Y |

| A*3301 | T | R | N | H | I | M | Q | I | V | L | T | H |

| A*3303 | T | R | N | H | I | M | Q | I | V | L | T | Y |

| A*6801 | Y | R | N | Q | T | M | R | T | V | W | T | Y |

2.2. Support vector machines

SVMs are popular due to attractive features and their promising performance. SVMs implement a simple idea: they map pattern vectors to a high-dimensional feature space where a best separating hyperplane can be constructed (Webb, 2002). It provides a linear separation in an augmented space, by means of defined kernels. A SVM is an implementation of the Structural Risk Minimization (SRM) principle, which minimizes the upper bound on the expected generalization error (Vapnik, 1998). The SRM principle was shown to be superior to traditional Empirical Risk Minimization (ERM) principle, employed by conventional neural networks. SRM minimizes an upper bound on the expected risk, as opposed to ERM that minimizes the error on the training data. This difference enables SVMs to generalize well, which is a statistical learning goal (Gunn, 1998).

Here we consider the binary classification task in which we have a set of training patterns {xi, i= 1,…n} assigned to one of two classes, ω1 and ω2, with corresponding labels g(x)=0. In this study, xi is a binary string representing a 9-mer peptide and class ω1 and ω2 correspond to HLA binders and non-binders. The linear discriminate function is:

| (1) |

with decision rule

| (2) |

All training points are correctly classified if

There may be more than one separating hyperplanes. The maximal margin classifier determines the hyperplane for which the margin – the distance to two parallel hyperplanes on each side of the separating hyperplane – is the largest. The assumption is that the larger the margin, the better the generalization error of the linear classifier defined by the separating hyperplane. To aid generalization, a margin, b>0, is introduced. Solution must satisfy the condition:

| (3) |

Without loss of generality, a value b=1 may be taken, defining canonical hyperplane:

| (4) |

The distance between each of these two hyperplanes and the separating hyperplane, g(x)=0, is 1/|w| and is termed margin. Maximizing the margin means that we seek a solution that minimize |w| subject to the constraints

| (5) |

A standard approach to optimization problems that have equality and inequality constraints is the Lagrange formalism (Fletcher, 1987). This formalism leads to the primal form of the objective function, Lp, given by

| (6) |

where {αi, i=1,…n;αi ≥0} are the Lagrange multipliers. The solution to the problem of minimizing wTw subject to constraints (5) is equivalent to determining the saddle point of the function Lp, at which Lp is minimized with respect to w and w0 and maximized with respect to the αi. Differentiating Lp with respect to w and w0 and equating to zero yields:

Substituting into Eq. (6) gives the dual form of the Lagrangian:

which is maximized with respect to the αi subject to:

The support vector algorithm may be applied in a transformed feature space, φ(x), using a nonlinear function. The discriminate function shown in Eq. (1) now changes to:

Acceptable kernels must be expressible as an inner product in a feature space, or k(x,y) = φT(x) φ(y). Frequently used kernels are polynomial:

and radial basis (Gaussian) kernel:

Both polynomial and Gaussian kernels have been tried in our experiments.

2.3. Training, testing and validation

Training of support vector machines was carried out using SVMlight (Joachims, 1999). An input to this package is a binary vector indicating whether a particular amino acid is presented at a particular position and a label with value 1 or 0 indicating if the peptide is a HLA binder or non-binder. Three kernel functions were examined (linear, polynomial and radial basis), and three existing parameters were optimized (trade-off c, power d for polynomial kernel, and parameter g for radial kernel). SVM models with kernels and parameter settings were trained and evaluated for each of HLA-A2 and -A3 dataset. Parameter values used during this process were the following: c (trade-off between training error and margin) was varied from 0.01 to 20, d (degree in polynomial kernel) from 1 to 10 and g (as shown in Gaussian kernel) from 0.001 to 1. Models that showed the best performance (one for each supertype) were used for final testing and validation. Although by default threshold 0 represents the separating hyperplane, data available are often imbalanced and not randomly distributed. Moving the decision boundary, which is equivalent to choosing a different threshold, is often used for remedying the imbalanced training-data problem (Wu and Chang, 2003). In our experiments, the decision boundary (threshold) was chosen using the performance measures of the SVM models.

The predictive performance was assessed using sensitivity (SE) and specificity (SP), and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis. TP is the number of true positives (experimental binders predicted as binders), FP the number of false positives (experimental non-binders predicted as binders), TN the number of true negatives (experimental non-binders predicted as non-binders) and FN the number of false negatives (experimental binders predicted as non-binders), SE=TP/(TP+FN) indicates the percentage of correctly predicted binders; SP = TN/(TN+FP) stands for the percentage of correctly predicted non-binders. The ROC curve is a plot of SE against (1-SP) at various classification thresholds (Swets, 1988). The area under the ROC curve (AROC) is a measure for the overall prediction performance. Values of AROC<0.7 represent poor predictions; AROC>0.8 represents good and AROC>0.9 represents excellent predictions, while AROC=0.5 represents random guessing (Swets, 1988). The statistical significance of the comparisons was assessed by t-test. The t-test assesses whether the means of two groups are statistically different from each other (Pagano and Gauvreau, 2000) and is suitable for evaluation of statistical differences for small number of measurements (30 or less in a sample).

Cross-validation is a method for error rate estimation. It implements a simple idea: the dataset of size n samples is partitioned into two parts, the model parameters are estimated using one set and the goodness-of-fit criterion evaluated on the second set. The cross-validation estimates the goodness-of-fit, which identifies how well a statistical model fits a set of observations. In our experiments, 10-fold cross-validation was performed to evaluate the performance of the classifiers. The dataset was randomly divided into 10 sets with approximately equal size. For each “fold”, the classifier is trained using all but one of the 10 groups and then tested on the remaining “unseen” group. This procedure is repeated for each of the 10 groups. The final AROC is calculated by micro-averaging the results obtained from the 10 runs (TP, TN, FP, and FN were summed up before the calculation of AROC).

In addition to cross-validation, we also performed blind testing for the assessment of the performance of SVM models for prediction of promiscuous HLA-A2 and -A3 binding peptides. For testing purposes, a model was built for each allele. The test set for each model included all peptides related to the allele, while the training set consisted of all peptides related to other HLA alleles from the same supertype. Thus prediction of peptides that bind one HLA allele was performed without any prior knowledge of the peptides binding or not binding to this allele. Because the actual prediction model incorporates all data, the testing results are likely to represent an underestimate of the actual performance. We trained five HLA-A2 and seven HLA-A3 models — the selected molecules are shown in Tables 5 and 6. Other alleles were not used for testing, as there was insufficient experimental data related to them for testing to be valid. The performance of SVM was compared to performances of existing methods, HMM and ANN models.

Table 5.

Blind testing on five HLA-A2 alleles: numbers of peptides in training and testing sets

| HLA-A2 allele | Training data | Testing data | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Binders | Non-binders | Binders | Non-binders | |

| A*0201 | 224 | 378 | 440 | 1999 |

| A*0202 | 619 | 2361 | 45 | 25 |

| A*0204 | 641 | 2162 | 23 | 224 |

| A*0205 | 648 | 2346 | 16 | 40 |

| A*0206 | 621 | 2349 | 43 | 37 |

Table 6.

Blind testing on seven HLA-A3 alleles: numbers of peptides in training and testing sets

| HLA-A3 allele | Training data | Testing data | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Binders | Non-binders | Binders | Non-binders | |

| A*0301 | 573 | 1447 | 107 | 89 |

| A*0302 | 534 | 1277 | 146 | 259 |

| A*1101 | 538 | 1313 | 142 | 223 |

| A*1102 | 538 | 1325 | 142 | 211 |

| A*3101 | 636 | 1482 | 44 | 54 |

| A*3301 | 645 | 1474 | 35 | 62 |

| A*6801 | 621 | 898 | 59 | 638 |

Stratified 10-fold cross-validation was performed on peptides related to A*0201 and A*0302 molecules. In stratified 10-fold cross-validation, the dataset is randomly divided into 10 sets with approximately equal size and class distributions. And the peptides in the training data that were similar (only one amino acid different) to any peptide from the test set were removed.

A set of 240 9-mer peptides of HPV type 16 E6 and E7 proteins with experimentally identified binding affinity were used for model validation (Kast et al., 1994). Experiments revealed that there are four 9-mer peptides, E6-7, E6-18, E6-26 and E6-52, bind to A*0201 in HPV E6 and seven A*0201 9-mer binders, E7-7, E7-11, E7-12, E7-66, E7-82, E7-85 and E7-86 in HPV E7. There are nine 9-mer peptides, E6-7, E6-33, E6-42, E6-59, E6-75, E6-89, E6-93, E6-125 and E6-143, that bind A*0301 in HPV E6 and one weak A*0301 binder, E7-89 in HPV E7. The training datasets were checked for the duplicate 9-mers peptides pertaining to E6 and E7 proteins and were removed. After removing duplicates, there were 3027 9-mer peptides (651 binders and 2376 non-binders) and 2164 9-mer peptides (653 binders and 1511 non-binders) in the training datasets for HLA-A2 and HLA-A3 models respectively. The comparative performance with other servers for prediction of promiscuous HLA class I peptides was not possible because of unmatched allelic variants that are covered by models in different servers.

A large experimental dataset of quantitative MHC– peptide binding data was recently made available (Peters et al., 2006). Using this dataset, they compared the performance of different bioinformatics approaches, including MULTIPRED ANN and HMM models, in predicting MHC binding peptides. The performance of these models has been reported in Tables 2 and 3 of the paper. We used the same dataset for evaluation of our HLA-A2/A3 SVM models. In the Peters dataset, the IC50 value used to separate binders and non-binders is 500 nM, whereas in the Dataset1 and Dataset2, the IC50 value used to separate binders and non-binders is 5000 nM. The difference in the threshold setting results in some discrepancy between our datasets and the Peters dataset. Some identical peptides between Dataset1, Dataset2 and the Peters dataset have been classified into different classes. The binding affinities of such peptides in Dataset1 and Dataset2 were modified to the binding affinities in the Peters dataset and these overlapping peptides were removed from the test sets. The number of 9-mer peptides in the Peters dataset related to HLA-A2/A3 alleles, the number of overlapping 9-mer peptides between Dataset1/Dataset2 and the Peters dataset and the number of non-overlapping peptides used for testing of the HLA-A2/A3 SVM models are shown in Tables 7 and 8 respectively. The testing datasets are available for download at antigen.i2r.a-star.edu.sg/multipred1/data.

Table 7.

Number of 9-mer peptides in the Peters dataset related to HLA-A2 alleles; number of overlapping peptides between Dataset1 and the Peters dataset; number of non-overlapping peptides (binders/non-binders) used for testing of the HLA-A2 SVM model

| A*0201 | A*0202 | A*0203 | A*0206 | A*6802 | A*6901 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Peters dataset | 3089 | 1447 | 1443 | 1437 | 1434 | 833 |

| Overlapping | 240 | 54 | 48 | 47 | 47 | 0 |

| Non-overlapping | 2849 (1024/1825) | 1393 (611/782) | 1395 (600/795) | 1390 (480/910) | 1387 (387/1000) | 833 (86/747) |

Table 8.

Number of 9-mer peptides in the Peters dataset related to HLA-A3 alleles; number of overlapping peptides between Dataset2 and the Peters dataset; number of non-overlapping peptides (binders/non-binders) used for testing of the HLA-A3 SVM model

| A*0301 | A*1101 | A*3101 | A*3301 | A*6801 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Peters dataset | 2094 | 1985 | 1869 | 1140 | 1141 |

| Overlapping | 97 | 102 | 71 | 70 | 69 |

| Non-overlapping | 1997(452/1545) | 1883(618/1265) | 1798(399/1399) | 1070(161/909) | 1072(455/617) |

2.4. Comparison of prediction methods

The performance of the SVM method was compared to the previously reported MULTIPRED models based on HMM (Brusic et al., 2002) and ANN (Zhang et al., 2005b). All models were retrained with the current dataset and assessed using the same train/test partitions.

3. Results

3.1. Cross-validation results

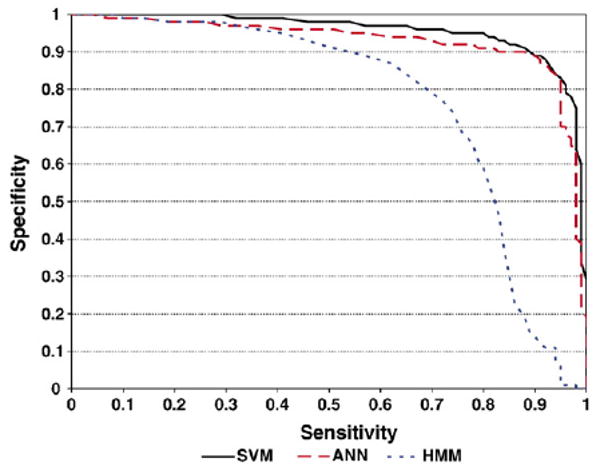

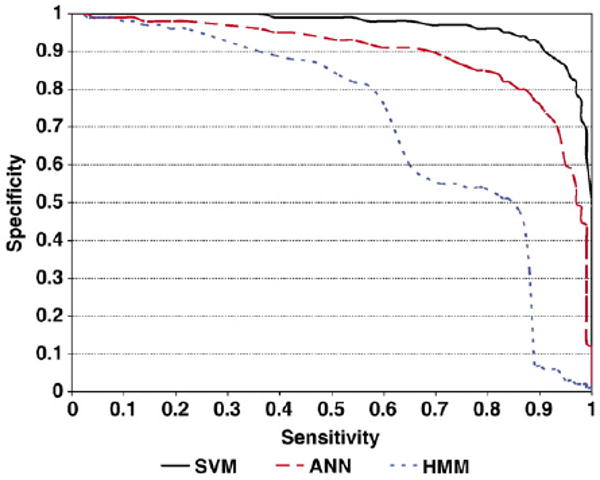

Ten-fold cross-validation was performed on all three methods. The AROC of ANN models is 0.93 for HLA-A2 dataset and 0.89 for HLA-A3 dataset. The AROCof HMM models are 0.77 for HLA-A2 dataset and 0.71 for HLA-A3 dataset. The AROC of SVM models are 0.95 for HLA-A2 dataset and 0.97 for HLA-A3 dataset. The sensitivities of the models were calculated at three levels: SP values of 0.8, 0.9 and 0.95 (Tables 9 and 10). For both HLA-A2 and HLA-A3 datasets, SVM models are of the highest sensitivity. Especially when specificity threshold is high (at 0.95), the sensitivity of SVM models is markedly higher that that of ANN and HMM models. The AROC values of the models in predicting peptides binding to HLA-A2/A3 alleles are listed in Tables 11 and 12. “Average” is the average of the AROC values for the individual tests and “Std. dev” is the standard deviation of the measurements. SVM models perform the best on all alleles with average AROC=0.914 for HLA-A2 alleles and AROC =0.951 for HLA-A3 alleles. Figs. 1 and 2 show the specificity and sensitivity relationship in 10-fold cross-validation.

Table 9.

Sensitivities and (prediction thresholds) for 10-fold cross-validation on Dataset1 using SVM, ANN and HMM models

| Specificity | Sensitivity | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| SVM | ANN | HMM | |

| 0.80 | 0.96 (−0.82) | 0.95 | 0.69 |

| 0.90 | 0.90 (−0.52) | 0.84 | 0.55 |

| 0.95 | 0.76 (−0.02) | 0.55 | 0.42 |

The values are given for three levels of specificity, 0.8, 0.9 and 0.95.

Table 10.

Sensitivities and (prediction thresholds) for 10-fold cross-validation on Dataset2 using SVM, ANN and HMM models

| Specificity | Sensitivity | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| SVM | ANN | HMM | |

| 0.80 | 0.97 (−0.65) | 0.86 | 0.56 |

| 0.90 | 0.92 (−0.30) | 0.66 | 0.36 |

| 0.95 | 0.84 (−0.05) | 0.41 | 0.24 |

The values are given for three levels of specificity, 0.8, 0.9 and 0.95.

Table 11.

AROC values for 10-fold cross-validation on Dataset1 using SVM, ANN and HMM models

| HLA-A2 allele | SVM | ANN | HMM |

|---|---|---|---|

| A*0201 | 0.96 | 0.94 | 0.90 |

| A*0202 | 0.83 | 0.65 | 0.80 |

| A*0204 | 0.94 | 0.83 | 0.87 |

| A*0205 | 0.96 | 0.91 | 0.82 |

| A*0206 | 0.88 | 0.81 | 0.84 |

| Average | 0.914 | 0.828 | 0.846 |

| Std. dev | 0.057 | 0.113 | 0.039 |

Table 12.

AROC values for 10-fold cross-validation on Dataset2 using SVM, ANN and HMM models

| HLA-A3 allele | SVM | ANN | HMM |

|---|---|---|---|

| A*0301 | 0.96 | 0.87 | 0.93 |

| A*0302 | 0.92 | 0.84 | 0.84 |

| A*1101 | 0.98 | 0.91 | 0.91 |

| A*1102 | 0.96 | 0.89 | 0.85 |

| A*3101 | 0.89 | 0.72 | 0.66 |

| *3301 | 0.96 | 0.65 | 0.54 |

| A*6801 | 0.99 | 0.95 | 0.93 |

| Average | 0.951 | 0.833 | 0.809 |

| Std. dev | 0.034 | 0.108 | 0.151 |

Fig. 1.

Sensitivity vs. specificity in 10-fold cross-validation on Dataset1 using SVM, ANN and HMM models.

Fig. 2.

Sensitivity vs. specificity in 10-fold cross-validation on Dataset2 using SVM, ANN and HMM models.

3.2. Blind testing results

The AROC values of the prediction models in blind testing are shown in Tables 13 and 14. The AROC values of predictions for peptide binding to A*0201, A*0204, A*0205, A*0301, A*1101, A*1102, A*3301, A*6801 were equal to or higher than 0.90. Overall, predictions models performed well (Aroc=0.892 for HLA-A2 alleles and AROC=0.924 for HLA-A3 alleles). The significance of these results is that training sets in this particular assessment did not include any of the peptides from test sets which contain all the peptides related with an allele at one time. The results corroborate that this method can be used for prediction of good or excellent accuracy of peptide binding to complete supertypes, even for those alleles where no binding data are available.

Table 13.

AROC values for blind testing on HLA-A2 dataset using SVM, ANN and HMM models

| HLA-A2 allele | SVM | ANN | HMM |

|---|---|---|---|

| A*0201 | 0.90 | 0.87 | 0.93 |

| A*0202 | 0.81 | 0.76 | 0.73 |

| A*0204 | 0.93 | 0.88 | 0.92 |

| A*0205 | 0.97 | 0.93 | 0.94 |

| A*0206 | 0.85 | 0.91 | 0.88 |

| Average | 0.892 | 0.87 | 0.88 |

| Std.dev. | 0.063 | 0.066 | 0.087 |

Table 14.

AROC values for blind testing on HLA-A3 dataset using SVM, ANN and HMM models

| HLA-A3 allele | SVM | ANN | HMM |

|---|---|---|---|

| A*0301 | 0.93 | 0.89 | 0.94 |

| A*0302 | 0.86 | 0.84 | 0.86 |

| A*1101 | 0.96 | 0.91 | 0.91 |

| A*1102 | 0.96 | 0.86 | 0.86 |

| A*3101 | 0.87 | 0.69 | 0.66 |

| A*3301 | 0.92 | 0.63 | 0.58 |

| A*6801 | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.95 |

| Average | 0.924 | 0.83 | 0.8229 |

| Std.dev. | 0.044 | 0.144 | 0.120 |

The AROC values for A*0202, A*1102, A*3101 and A*3301 prediction models were improved markedly using SVM models (Tables 13 and 14), This might be explained by the fact that sets of peptides related to these molecules are relatively small (less than 100 peptides). SVM are known to outperform other prediction methods on smaller datasets. HMM performed better on A*0201 and A*0301 (however, SVM still has reasonably high AROC values for these two molecules), and both HMM and ANN models of A*0206 molecule performed better then the corresponding SVM model.

T-test was applied to determine whether the difference in SVM, HMM and ANN predictive performance is statistically significant. The results showed that the performance of SVM is statistically better than the performances of other two methods on HLA-A3 alleles (P<0.05). However, the same conclusion could not be drawn for HLA-A2 alleles. This might be due either to similar performance of studied predictive models or to the imbalance in the HLA-A2 dataset. SVM often do not perform the best on imbalanced datasets (Wu and Chang, 2003), and HLA-A2 Dataset1 is imbalanced in two ways: binders/non-binders ratio is close to 1:4, and peptides related to A*0201 present 80% (2439 of 3050), while peptides related to all other alleles present only 20% of the total dataset. The HLA-A3 Dataset2 is more balanced in both aspects, and in this case we observed statistically better performance of SVM than other prediction methods.

3.3. Validation using HPV E6 and E7 proteins

The AROC values of SVM, HMM, and ANN predictions for HPV E6 and E7 proteins are shown in Table 15. Overall, SVM models show better performance on prediction of peptides derived as a full overlapping set from viral proteins E6 and E7 than ANN and HMM. SVM show the highest AROC for HLA-A3 supertype predictions, and SVM and ANN show the same excellent performance on predictions for HLA-A2 supertype.

Table 15.

AROC values for predictions on HPV E6 and E7 proteins using SVM, ANN and HMM models

| SVM | ANN | HMM | |

|---|---|---|---|

| A2 AROC | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.88 |

| A3 AROC | 0.95 | 0.80 | 0.91 |

In summary, we report the improved overall performance of SVM models for prediction of peptide binding to multiple molecules of HLA-A3 supertype, and at least as good performance for HLA-A2 as supported it with exhaustive testing. We have shown that SVM models can predict peptide binding to HLA-A2 and HLA-A3 molecules with good performance, including those alleles for which no experimental binding data are currently available.

3.4. Validation using the Peters dataset

The AROC values of HLA-A2 SVM model for predictions of binding peptides for HLA-A2 supertype alleles (A*0201, A*0202, A*0203, A*0206, A*6802 and A*6901) using the Peters dataset (Table 16) show marked improvement for all studied alleles. We note that HLA-A2 SVM model performs well in predicting A*6901 binding peptides (AROC=0.81) although only four peptides related to A*6901 were used for model training. In addition, HLA-A2 SVM model showed better performance in predicting peptides binding to all HLA-A2 alleles than all the external tools evaluated in (Peters et al., 2006) and is equal or better for three of five studied HLA-A3 alleles than the best external tool. We note that only five A*3301-related peptides were in Dataset2 for training of HLA-A3 SVM model.

Table 16.

AROC values of SVM models for predictions of binding peptides for HLA-A2 and -A3 supertypes using the Peters dataset

| HLA-A* | 0201 | 0202 | 0203 | 0206 | 6802 | 6901 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SVM AROC | 0.91 | 0.83 | 0.82 | 0.79 | 0.74 | 0.81 | |

| ANN AROC | 0.88 | 0.79 | 0.79 | 0.74 | <0.64 | – | |

| HLA-A* | 0301 | 1101 | 3101 | 3301 | 6801 | ||

| SVM AROC | 0.87 | 0.89 | 0.83 | 0.79 | 0.76 | ||

| ANN AROC | 0.85 | 0.87 | <0.83 | <0.81 | <0.77 | ||

AROC values of ANN MULTIPRED are taken from Peters et al. (2006).

In Dataset2, there were 697 peptides related to A*6801 with 8.5% of them being binders and 91.5% being non-binders. To understand why HLA-A3 SVM model performed poorly in predicting peptide binding to A*6801, we performed additional analysis at the peptide sequence level. The poor performance of the HLA-A3 SVM model in predicting peptides binding to A*6801 was because the limited number of binders in training dataset do not represent the diverse pattern of A*6801 binding motif. For example, in the training data all binders had K or R at the anchor position 9, while Y, which is present in some binders in the Peters dataset was not represented in the training data. This emphasizes the need for use of representative datasets for development of MHC-binding prediction servers. While the accuracy of predictions will improve by adding new data to the training sets, it is important to note that about a quarter of MHC class I binding peptides lack canonical binding motifs (A. Sette, personal communication). These peptides are underrepresented in the current datasets, which are used both for training and testing, and therefore the values of accuracy of predictive methods are likely to be somewhat lower than reported, across all comparative studies.

3.5. MULTIPRED1 — an online computational system for prediction of promiscuous HLA binding peptides

Previously we developed MULTIPRED (Zhang et al., 2005a), a web-based computational system for prediction of peptide binding to multiple molecules belonging to HLA class I A2, A3 and class II DR supertypes. It uses HMM and ANN as predictive engines. With SVM models integrated, an updated version of the system – MULTIPRED1 – was developed.

In MULTIPRED1, the prediction scores produced by SVM models were rescaled to map them into the range from one to nine. The mapping of scores was done according to equation, ScoreN=(Score − Scoremin)/(Scoremax−Scoremin)×8+1, where ScoreN denotes the normalized score, Score denotes the raw prediction score produced by SVM models, and Scoremax and Scoremin denote the possible minimum and maximum values of the raw scores respectively. The values for Scoremax and Scoremin were obtained through extensive testing. More than 650 randomly selected protein sequences from the NCBI protein database (contained more than 220,000 9-mer peptides) were used for prediction using the SVM models. Since the testing data contains huge number of 9-mer peptides, the highest and lowest predicted score from the testing data were taken as reasonable maximum and minimum scores for normalization.

4. Discussion and conclusion

Throughout training and testing, we examined different kernels (linear, radial basis and polynomial) and optimized SVM parameters (trade-off c, parameter g for radial basis kernel and degree d for polynomial kernel). The models that had the best performances (in terms of the highest average blind testing AROC value for molecules within a given supertype) were: Gaussian kernel with g=0.1 and c=0.5 for HLA-A2 and Gaussian kernel with g=0.1 and c=2 for HLA-A3 supertype.

We report that Gaussian kernel performs best on both HLA-A2 and -A3 molecules. This is in contrast to the report by (Zhao et al., 2003), where linear kernel showed the best performance for T-cell epitopes prediction. However, their model was trained only for a single allele (A*0201) and their dataset contained a smaller number of peptides (203). Our results also differ from those reported by Donnes and Elofsson (2002), who trained a different SVM model, including different selection of kernels and parameters, for each allele. These results indicate that future improvements of SVM performance will likely be driven by the increase of datasets, rather than optimization of kernel function and SVM parameters. The main difference between this work and other studies that employed SVM for prediction of HLA binders is that each SVM model built is for prediction of peptides that bind molecules from an entire supertype (HLA-A2 or -A3). In addition, our models can predict peptide binding to HLA-A2 and -A3 alleles for which no binding data are available. For example, HLA-A2 SVM model performs reasonably well in predicting A*6901 binding peptides (AROC =0.81) when validated using the Peters dataset in spite of only four A*6901-related peptides being used for training the model. However, the limited number of peptides in training dataset may affect the performance of the prediction models, as in the case of A*6801.

Development of epitope-based vaccines is progressing rapidly. Selection of peptides for candidate subunit vaccines is one of the greatest obstacles in the development of vaccines with broad and non-ethnically-biased coverage of the human population. Computational systems that can predict promiscuous peptides complement experimental approaches for overcoming this obstacle.

Acknowledgments

This project has been funded in part (GLZ, JTA, and VB) with the USA Federal funds from the NIAID, NIH, Department of Health and Human Services, under Grant No.5U19 AI56541 and Contract No.HHSN266200400085C.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ada G. Progress towards achieving new vaccine and vaccination goals. Intern Med J. 2003;33:297. doi: 10.1046/j.1445-5994.2003.00365.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander C, Kay AB, Larche M. Peptide-based vaccines in the treatment of specific allergy. Curr Drug Targets Inflamm Allergy. 2002;1:353. doi: 10.2174/1568010023344562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antes I, Siu SW, Lengauer T. DynaPred: a structure and sequence based method for the prediction of MHC class I binding peptide sequences and conformations. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:e16. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berzofsky JA, Ahlers JD, Belyakov IM. Strategies for designing and optimizing new generation vaccines. Nat Rev Immunol. 2001;1:209. doi: 10.1038/35105075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhasin M, Raghava GP. Prediction of CTL epitopes using QM, SVM and ANN techniques. Vaccine. 2004;22:3195. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozic I, Zhang GL, Brusic V. Predictive vaccinology: optimisation of predictions using support vector machine classifiers. Lect Notes Comput Sci. 2005;3578:375. [Google Scholar]

- Brusic V, Rudy G, Harrison LC. MHCPEP, a database of MHC-binding peptides. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:3663. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.17.3663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brusic V, Petrovsky N, Zhang G, Bajic VB. Prediction of promiscuous peptides that bind HLA class I molecules. Immunol Cell Biol. 2002;80:280. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.2002.01088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brusic V, Bajic VB, Petrovsky N. Computational methods for prediction of T-cell epitopes — a framework for modeling, testing and applications. Methods. 2004;34:436. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bui HH, Schiewe AJ, von Grafenstein H, Haworth IS. Structural prediction of peptides binding to MHC class I molecules. Proteins. 2006;63:43. doi: 10.1002/prot.20870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chelvanayagam G. A roadmap for HLA-A, HLA-B, and HLA-C peptide binding specificities. Immunogenetics. 1996;45:15. doi: 10.1007/s002510050162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen JK, Lamberth K, Nielsen M, Lundegaard C, Worning P, Lauemoller SL, Buus S, Brunak S, Lund O. Selecting informative data for developing peptide–MHC binding predictors using a comment by committee approach. Neural Comput. 2003;15:2931. doi: 10.1162/089976603322518803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui J, Han LY, Lin HH, Zhang HL, Tang ZQ, Zheng CJ, Cao ZW, Chen YZ. Prediction of MHC-binding peptides of flexible lengths from sequence-derived structural and physicochemical properties. Mol Immunol. 2007;44:866. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Groot AS. Immunomics: discovering new targets for vaccines and therapeutics. Drug Discov Today. 2006;11:203. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(05)03720-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnes P, Elofsson A. Prediction of MHC class I binding peptides, using SVMHC. BMC Bioinformatics. 2002;3:25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-3-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doytchinova IA, Guan P, Flower DR. Identifying human MHC supertypes using bioinformatic methods. J Immunol. 2004;172:4314. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.7.4314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durrant LG, Ramage JM. Development of cancer vaccines to activate cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2005;5:555. doi: 10.1517/14712598.5.4.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabbri M, Smart C, Pardi R. T lymphocytes. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2003;35:1004. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(03)00037-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher R. Practical Methods of Optimization. John Wiley and Sons Inc.; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Gunn SR. Image Speech and Intelligent Systems Group. ISIS Technical Report. University of Southampton; 1998. Support vector machines for classification and regression. [Google Scholar]

- Honeyman MC, Brusic V, Stone NL, Harrison LC. Neural network-based prediction of candidate T-cell epitopes. Nat Biotechnol. 1998;16:966. doi: 10.1038/nbt1098-966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joachims T. Making Large-Scale SVM Learning Practical Advances in Kernel Methods — Support Vector Learning. MIT Press; Cambridge: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kast WM, Brandt RM, Sidney J, Drijfhout JW, Kubo RT, Grey HM, Melief CJ, Sette A. Role of HLA-A motifs in identification of potential CTL epitopes in human papillomavirus type 16 E6 and E7 proteins. J Immunol. 1994;152:3904. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Z, Wu Y, Zhu B, Ni B, Wang L. Toward the quantitative prediction of T-cell epitopes: QSAR studies on peptides having affinity with the class I MHC molecular HLA-A*0201. J Comput Biol. 2004;11:683. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2004.11.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W, Meng X, Xu Q, Flower DR, Li T. Quantitative prediction of mouse class I MHC peptide binding affinity using support vector machine regression (SVR) models. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:182. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund O, Nielsen M, Kesmir C, Petersen AG, Lundegaard C, Worning P, Sylvester-Hvid C, Lamberth K, Røder G, Justesen S, Buus S, Brunak S. Definition of supertypes for HLA molecules using clustering of specificity matrices. Immunogenetics. 2004;55:797. doi: 10.1007/s00251-004-0647-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallios RR. Predicting class II MHC/peptide multi-level binding with an iterative stepwise discriminant analysis meta-algorithm. Bioinformatics. 2001;17:942. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.10.942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamitsuka H. Predicting peptides that bind to MHC molecules using supervised learning of hidden Markov models. Proteins. 1998;33:460. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0134(19981201)33:4<460::aid-prot2>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagano M, Gauvreau K. Principles of Biostatistics. Duxbury Thomson Learning; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Pamer E, Cresswell P. Mechanisms of MHC class I-restricted antigen processing. Annu Rev Immunol. 1998;16:323. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker KC, Bednarek MA, Coligan JE. Scheme for ranking potential HLA-A2 binding peptides based on independent binding of individual peptide side-chains. J Immunol. 1994;152:163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters B, Sette A. Generating quantitative models describing the sequence specificity of biological processes with the stabilized matrix method. BMC Bioinformatics. 2005;6:132. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-6-132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters B, Bui HH, Frankild S, Nielson M, Lundegaard C, Kostem E, Basch D, Lamberth K, Harndahl M, Fleri W, Wilson SS, Sidney J, Lund O, Buus S, Sette A. A community resource benchmarking predictions of peptide binding to MHC-I molecules. PLoS Comput Biol. 2006;2:e65. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0020065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quintana FJ, Cohen IR. DNAvaccines coding for heat-shock proteins (HSPs): tools for the activation of HSP-specific regulatory T cells. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2005;5:545. doi: 10.1517/14712598.5.4.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rammensee HG, Falk K, Rotzschke O. Peptides naturally presented by MHC class I molecules. Annu Rev Immunol. 1993;11:213. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.11.040193.001241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reche PA, Reinherz EL. PEPVAC: a web server for multi-epitope vaccine development based on the prediction of supertypic MHC ligands. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W138. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riedesel H, Kolbeck B, Schmetzer O, Knapp EW. Peptide binding at class I major histocompatibility complex scored with linear functions and support vector machines. Genome Inform. 2004;15:198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savoie CJ, Kamikawaji N, Sasazuki T, Kuhara S. Use of BONSAI decision trees for the identification of potential MHC class I peptide epitope motifs. Pac Symp Biocomput. 1999;182 doi: 10.1142/9789814447300_0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schirle M, Weinschenk T, Stevanovic S. Combining computer algorithms with experimental approaches permits the rapid and accurate identification of T cell epitopes from defined antigens. J Immunol Methods. 2001;257:1. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(01)00459-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schueler-Furman O, Altuvia Y, Sette A, Margalit H. Structure-based prediction of binding peptides to MHC class I molecules: application to a broad range of MHC alleles. Protein Sci. 2000;9:1838. doi: 10.1110/ps.9.9.1838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal MR, Cummings MP, Hubbard AE. Relating amino acid sequence to phenotype: analysis of peptide-binding data. Biometrics. 2001;57:632. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2001.00632.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sette A, Sidney J. Nine major HLA class I supertypes account for the vast preponderance of HLA-A and -B polymorphism. Immunogenetics. 1999;50:201. doi: 10.1007/s002510050594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sette A, Chesnut R, Livingston B, Wilson C, Newman M. HLA-binding peptides as a therapeutic approach for chronic HIV infection. IDrugs. 2000;3:643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh H, Raghava GP. ProPred1: prediction of promiscuous MHC Class-I binding sites. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1009. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan KN, Brusic V, August JT. New technologies for vaccine development. Drug Dev Res. 2004a;62:383. [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan KN, Zhang GL, Khan AM, August JT, Brusic V. Prediction of class I T-cell epitopes: evidence of presence of immunological hot spots inside antigens. Bioinformatics. 2004b;20:I297. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swets J. Measuring the accuracy of diagnostic systems. Science. 1988;240:1285. doi: 10.1126/science.3287615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Threlked SC, Wentworth PA, Kalams SA, Wilkes BM, Ruhl DJ, Keogh E, Sidney J, Southwood S, Walker BD, Sette A. Degenerate and promiscuous recognition by CTL of peptides presented by the MHC class I, A3-like superfamily; implications for vaccine development. J Immunol. 1997;159:1648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong JC, Zhang GL, Tan TW, August JT, Brusic V, Ranganathan S. Prediction of HLA-DQ3.2β ligands: evidence of multiple registers in class II binding peptides. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:1232. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vapnik VN. Statistical Learning Theory. Wiley; New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Verhagen J, Taylor A, Akdis M, Akdis CA. Targets in allergy-directed immunotherapy. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2005;9:217. doi: 10.1517/14728222.9.2.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb A. Statistical Pattern Recognition. 2nd. Wiley; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Williams TM. Human leukocyte antigen gene polymorphism and the histocompatibility laboratory. J Mol Diagnostics. 2001;3:98. doi: 10.1016/S1525-1578(10)60658-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson C, McKinney D, Anders M, MaWhinney S, Forster J, Crimi C, Southwood S, Sette A, Chesnut R, Newman M, Livingston B. Development of a DNA vaccine designed to induce cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses to multiple conserved epitopes in HIV-1. J Immunol. 2003;171:5611. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.10.5611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisniewski T, Frangione B. Immunological and anti-chaperone therapeutic approaches for Alzheimer disease. Brain Pathol. 2005;15:72. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2005.tb00102.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G, Chang EY. Adaptive feature-space conformal transformation for imbalanced-data learning. Proceedings of the Twentieth International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML-2003); Washington, DC. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Y, Segal MR. Prediction of genomewide conserved epitope profiles of HIV-1: classifier choice and peptide representation. Stat Appl Genet Mol Biol. 2005;4:25. doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang ZR, Johnson FC. Prediction of T-cell epitopes using biosupport vector machines. J Chem Inf Model. 2005;45:1424. doi: 10.1021/ci050004t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yewdell JW, Bennink JR. Cut and trim: generating MHC class I peptide ligands. Curr Opin Immunol. 2001;13:13. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(00)00175-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang GL, Khan AM, Srinivasan KN, August JT, Brusic V. MULTIPRED: a computational system for prediction of promiscuous HLA binding peptides. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005a;33:W172. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang GL, Khan AM, Srinivasan KN, August JT, Brusic V. Neural models for predicting viral vaccine targets. J Bioinform Comput Biol. 2005b;3:1207. doi: 10.1142/s0219720005001466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Pinilla C, Valmori D, Martin R, Simon R. Application of support vector machines for T-cell epitopes prediction. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1978. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]