Abstract

Simultaneous measurements of tissue PCO2 (PtCO2), interstitial H+ concentration ([H+]o), and tissue lactate content were used to examine changes in interstitial concentration ( ) during complete ischemia. In normoglycemic rats (blood glucose of 6–8 mM; neocortical ischemic-induced lactate content 8–12 mmol/kg) [H+]o increased from 7.22 ± 0.02 to 6.79 ± 0.02 pH (n = 3). By contrast, in hyperglycemic rats (blood glucose 18–75 mM; ischemic-induced lactate content 19–31 mmol/kg) [H+]o rose by a significantly larger amount to 6.19 ± 0.02 pH (n = 7), Given that is the predominant interstitial H+ buffer, changes in peak PtCO2 show why peak [H+]o were bimodally distributed compared with lactate content. Between 8 and 12 mmol/kg lactate, when peak PtCO2 rose from 99 to 186 Torr but [H+]o, was constant at 6.79 pH, calculated increased from 11.9 to 21.9 mM. Then after transitional changes, peak PtCO2 and [H+]o remained constant at 389 ± 9 Torr (n = 7) and 6.19 pH despite the fact that tissue lactate ranged from 19 to 31 mmol/kg lactate, respectively; must have remained constant at 12.3 ± 0.7 mM (n = 7). Since ischemic brain continued to produce another 12 more mmol/kg of lactic acid above 19 mmol/kg lactate without further changes in PtCO2 or [H+]o, H+ and must have been heterogeneously compartmented. The continued lactic acid production occurred in a compartment that occupied 36% of neocortical space. This compartment is likely to represent glial cells.

Keywords: pH, bicarbonate, glia, lactate, carbon dioxide, hydrogen ion microelectrode

Excessive Brain Acidosis is thought to worsen the outcome from stroke in humans (29) and animals (23, 30), but the specific cellular mechanisms by which such putative injury occurs remain undefined. Indeed, the absolute magnitude of H+ accumulation that could lead to ischemic brain necrosis in any cell compartment has not been measured. This lack, in part, stems from the complexity of the dynamic and interactive mechanisms by which H+ concentrations are regulated in a multicompartmented system such as the brain.

Both systemic and cellular processes influence H+ regulation in brain. Systemic processes include modifying the flux of volatile H+ buffers (CO2 and NH3) as well as H+-related ionic species across the blood-brain barrier by changes in pulmonary ventilation and cerebral blood flow. Cellular mechanisms include at least three physiological and chemical processes: 1) metabolic production and consumption of acids and bases; 2) cell physicochemical H+ buffers; and 3) ion transport across cell membranes (38). The last-mentioned mechanism has not been studied in ischemic brain. This omission undoubtedly stems from the tendency to regard ischemic brain tissue as a homogenous proteinaceous ionic milieu without compartmentation by intact plasma membranes (37).

We recently provided evidence implying that at least one population of brain cell plasma membranes remains intact during complete ischemia (19). Even under conditions of ischemic brain lactic acidosis that ultimately evolve to brain necrosis (i.e., lactate accumulation to >19 mmol/kg in neocortex; see Ref. 23), membranes appear to remain impermeable to H+ and H+-related ionic species so long as complete ischemia lasts. The finding suggests, therefore, an understanding of the mechanisms by which brain cell plasma membranes regulate H+ under normal and ischemic conditions may reveal important mechanisms through which excessive acidosis destroys brain tissue.

We have proposed that two factors may account for the brain’s ionic impermeability toward H+ during hyperglycemic and complete ischemia. The first factor consists of regulation of brain [H+] via antiports for Na+-H+ and (31, 42) that are arrested during ischemia by the degradation of transmembrane gradients for Na+ and Cl− and sufficient loss of brain stores. The second factor involves a decline in the diffusional permeability of the intact plasma membranes to H+, perhaps because of titration of surface proteins by excess H+. If these postulates are correct, worsening brain acidosis would be confined to the intracellular space bounded by such intact plasma membranes during hyperglycemia ischemia.

In the present study we report simultaneous measurements of interstitial [H+] and tissue PCO2 as well as peak neocortical lactate content during complete brain ischemia in anesthetized rats. The results provide further evidence of continued compartmentation of [H+] during hyperglycemic brain ischemia. In addition, we report a new technique to assess brain total content. As will be shown, the measurements indicate that, during severe ischemia, stores are exhausted from some intact population of brain cells and that the exhaustion occurs at or near a degree of lactate accumulation that previously has been associated with necrosis of all brain cells. Indirect evidence suggests that this unknown population of intact cells represents glia. If correct, the findings imply that brain infarction can be correlated to a loss of plasma membrane H+ regulatory mechanisms as well as intracellular stores in glia, a cell population increasingly recognized as contributing to H+ regulatory mechanisms of brain (13, 26). A preliminary report of some aspects of this work has appeared (16,18, 20)

METHODS

Animal preparation and recording

Male Wistar rats (250–400 g) were anesthetized with halothane (5% induction; 3% maintenance during surgery; 1.5–2.0% during recordings) and spontaneously ventilated with a 30% O2-N2 mixture via an inhalation mask. A tail artery and femoral vein were cannulated, and a 4- to 5-mm diameter craniotomy was made over parietal cortex, 1 mm lateral to the sagittal suture. Then animals were mounted in a standard head holder and warmed to 37°C. Normal (15) Ringer solution at 37°C flowed through a superfusion cup, placed around the craniotomy site, that was fastened in place with 3.5% agar and 150 mM NaCl. H+ ion-selective micropipettes (ISMs) and a tissue PCO2 (PtCO2) semimicroelectrode (Microelectrodes, Londonberry, NH MI-720) were mounted on a Narishige MT-5 micromanipulator, the H+ ISM being placed immediately adjacent but 500 μm deeper than the active surface of the CO2 electrode.

The assembled electrode array was advanced toward the brain so that the PtCO2 electrode recorded from the parietal pial surface while the H+ ISM penetrated 500 μm below in the interstitial space. After calibrations (see below) the superfusion cup was filled with light mineral oil to prevent loss of CO2 from the pial surface. Arterial pH, PO2 (PaO2), and PCO2 (PaCO2) were stabilized and monitored with a Corning 158 blood gas analyzer. Brain carbohydrate stores were adjusted by intraperitoneal injections of 0.93 M D-glucose (8.35 g/kg) or intravenous injection of regular insulin (2.0–6.0 U/kg of U-100 Iletin). Blood glucose was measured with a Glucometer (Miles Laboratories, Naperville, IL). After animals attained the desired blood glucose level, complete ischemia was induced by cardiac arrest from intravenous injection of 0.5 ml of 1 M KCl. When interstitial [H+] ([H+]o) and PtCO2 reached plateaus, animals were quickly decapitated and their heads dropped into liquid N2 for subsequent measurements of lactate content via enzyme fluorometric techniques (43).

Electrode preparation and calibration

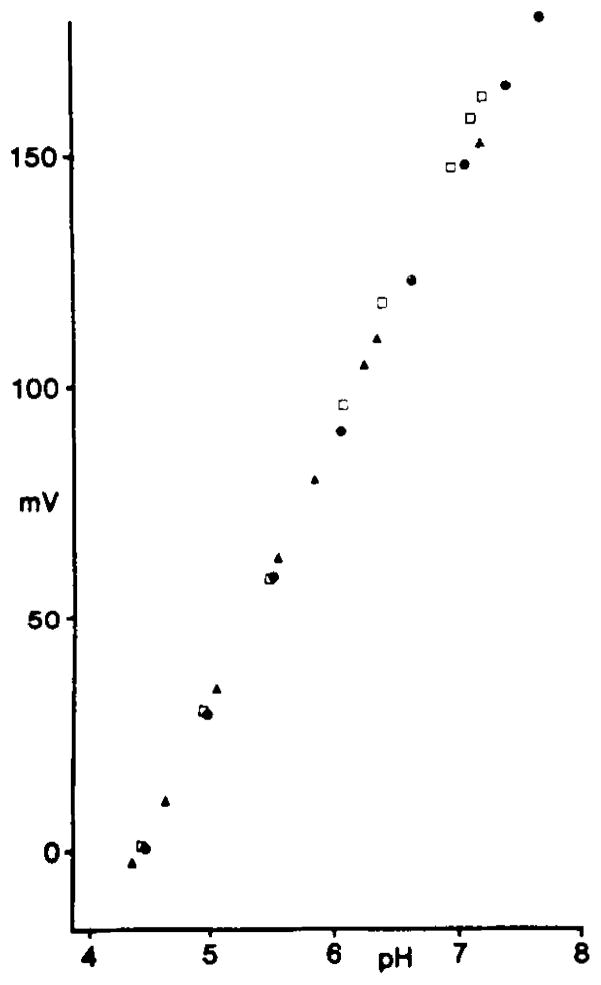

H+ ISMs based on tridodecylamine (1) were constructed, calibrated, and used as previously described (15, 19). We previously mentioned (15) that exposure of the neutral ionophore ligand, tridodecylamine, to CO2 did not appear to influence the behavior of H+ ISMs to changes in [H+], although such CO2 exposure was described in the original construction of these H+ ISMs (1). Here we report this finding in more detail. Potassium phosphate solutions were buffered to different [H+] with sodium hydroxide and then exposed to different PCO2’s to determine if CO2 influenced the linearity of H+ ISM output (Fig. 1). Figure 1 shows 5% or 100% CO2 minimally influenced the H+ electrode output slope compared with solutions equilibrated with room air containing an approximate PCO2 of 0.1 Torr.

FIG. 1.

Response of ion-selective micropipette (ISM) to changes in [H+] at different PCO2’s. Potassium phosphate solutions were buffered to different [H+] with sodium hydroxide and then equilibrated with CO2 at different partial pressures. Solid dots, linearity (correlation coefficient 0.999) and sensitivity (58 mV/decade change in [H+]) of liquid membrane H+ ISMs equilibrated at 25°C with room air (PCO2 ~0.1 Torr); open squares, H+ ISM response after same solutions were equilibrated with 5% CO2-95% O2 (correlation coefficient 0.999; 61 mV/decade change in [H+]); solid triangles, H+ ISM response after solutions were equilibrated with 100% CO2 (correlation coefficient 0.999; 61 mV/decade change in [H+]). These results show that H+ ISMs based on neutral ionophore tridodecylamine are not influenced by PCO2’s that exceed those found in brain in vivo. However, H+ ISMs do show a minor reduction in slope to changes in [H+] when PCO2 is nearly zero.

PtCO2 electrodes (MI-720) were used as supplied from the manufacturer (Microelectrodes). We are unaware of published reports describing this electrode and therefore outline its use and characteristics. The active surface consisted of a thin Teflon membrane. The electrode was filled with 5 mM NaHCO3 and 20 mM NaCl and connected to unity gain, high-performance buffer amplifiers (15). PtCO2 electrodes were calibrated at a place remote from the animal in humidified gas streams of 5% CO2-95% O2 and 100% CO2. For in situ electrode calibration the PtCO2 electrode was placed in the superfusion cup while normal Ringer solution equilibrated with either 5% CO2-95% O2 (7.35 pH at 25°C) or 100% CO2 (6.11 pH at 25°C) flowed through the cup. The PCO2 of the calibration gases (Torr) is described by

| (1) |

where PB is the barometric pressure (Torr), and Pw is the water vapor pressure (Torr) at the specified temperature. Output of the PtCO2 electrode is described by

| (2) |

where C is a constant dependent on the complete electrical system, and A is the slope of the electrode output in millivolts per decade change in PCO2. A is equal to RT/F where R is the gas constant, T is the temperature, and F the Faraday constant. At room temperature the PtCO2 electrode slope (A) was 52 ± 3 (n = 12) mV per decade change in PCO2. PtCO2 response time was defined as the time required for the output of the electrode to reach 95% (t95) of its final value after a step change in PCO2. t95 for the PtCO2 electrode was measured in the following manner. The electrode was placed in a loose-fitting plastic tube (5 cm long and 0.4 cm ID) connected to one port of a three-way stopcock. The other two ports received either humidified 5% CO2-95% O2 or 100% CO2. In this way, gas streams that passed the active surface of the CO2 electrode could be rapidly switched from one concentration to another. Figure 2 shows a typical recording from such measurements. t95 for the MI-720 CO2 electrode lay between 30 and 40 s.

FIG. 2.

Response time of CO2 electrode. CO2 electrode was exposed to low flow stream of humidified 5% CO2-95% O2. This gas was then switched to humidified 100% CO2 (downgoing arrow) and then back to 5% CO2-95% O2 (upgoing arrow) via 3-way stopcock. Time for electrode response to reach 95% of its maximal change was 30–40 s.

Interstitial

[ ] is derived from simultaneous measurements of test solution pH and PCO2. Henderson first described the dissociation of carbonic acid in biological solutions as

| (3) |

which is based on the law of chemical equilibrium and the isohydric principle (5). In 1916, Hasselbalch transformed Eq. 3 into the well-recognized Henderson-Hasselbalch equation (5)

| (4) |

where [ ] is expressed in millimolars, S is a solubility constant for CO2 (mM/mmHg), and K1 is the first ionization constant for carbonic acid. Both S and K1 vary with temperature and osmolality (22, 39) and when corrected for these two physical variables are represented as S′ and , respectively. also varies with pH (22, 39). This, of course, is not characteristic of a true thermodynamic constant but stems from the use of S′PCO2 as a quantity that approximates the sum of aqueous CO2 plus carbonic acid (39). This can be seen more clearly from Eq. 5, a–f. Exposure of a salt solution to CO2 gas [(CO2)g] results in solvation of CO2 according to

| (5a) |

The amount of dissolved CO2 ([CO2]aq) in the solution is given by Henry’s law

| (5b) |

Dissolved CO2 then reacts with water to form carbonic acid

| (5c) |

Carbonic acid goes through a first ionization to form

| (5d) |

In biological systems, PCO2 is commonly used to estimate dissolved [CO2] so that

| (5e) |

Since the carbonic acid concentration is pH dependent, , the apparent first ionization constant, is also pH dependent

| (5f) |

Notice that the second ionization constant, , defined as

| (5g) |

is not pH dependent because no S′PCO2 term is involved in the equation.

Mitchell et al. (22) determined S′ and for human cerebrospinal fluid at different temperatures and pH values. Their values are in close agreement with those given for S′ (34) and (35) of brain homogenates at comparable temperature and pH. However, since the spectrum of these experimental values for S′ and were insufficient for use in total CO2 measurements (see below), which were done at room temperature (20°C), or for in vivo calculations under ischemic conditions (pH ~6), we fitted the experimental data of Mitchell et al. (22) to the following curves in order to extrapolate their data to our experimental conditions

| (6) |

where t is in degrees Celsius (correction coefficient is >0.999).

| (7) |

with a correlation coefficient of 0.963. Changes in due to temperature fluctuations are small and can be predicted from the effect of temperature on the standard free-energy equation for (6). S′ and were not corrected for osmolality because no information is available as to how brain interstitial osmolality might vary under ischemic conditions.

Total CO2 and total calculations

Determination of brain total CO2 (tCO2) has traditionally been performed using the Van Slyke technique (44). According to this method, frozen samples of brain are placed in a closed container after which excess strong acid is added to liberate all carbonic acid buffer species as CO2 gas. The latter is absorbed onto some material that is then weighed to reflect the amount of trapped CO2. This procedure has two serious drawbacks. First, it requires hours to trap all the liberated CO2. Second, the technique for handling brain samples is very sensitive to error because CO2 or water vapor from the environment can deposit onto brain samples frozen with liquid N2 and handled near −79°C temperature. For this reason, an elaborate and expensive cold box system with a controlled atmospheric environment has been used (14).

We report here an inexpensive and rapid method for determination of tCO2 that is reproducible (±0.2 mM determined from 10 consecutive measurements of a standard -based Ringer solution), sensitive (>±0.1 mM as estimated from equivalent voltage sensitivity of recording system), and accurate (see Fig. 4). The method used the MI-720 CO2 electrode (Microelectrodes). Rats were anesthetized with halothane and ventilated spontaneously. Arterial blood gases were stabilized, and after 60–70 min at a specific PaCO2, heads were frozen with liquid N2 by the method of Pontén and Siesjö (27). Animals were then decapitated and their heads stored at −80°C. Small pieces (10–20 mg) of cerebral cortex were dissected from whole brain at −25°C. Total brain samples (20–100 mg) were placed in individual 10-ml closed plastic containers for 2–5 h of equilibration at −25°C. If samples were used before this period of equilibration, tCO2 values were consistently elevated from those obtained by Kjällquist et al. (14). This may have resulted because of deposition of environmental CO2 onto frozen samples whose temperatures were still below −79°C (freezing point for CO2) during initial freezing and handling. There was no detectable difference (i.e., <0.1 mM) in comparable tCO2 values measured after 2–5 h at −25°C. Therefore, this delay did not allow time for significant loss of endogenous tCO2 stores to occur from the samples. The experimenter wore a surgical mask at all times to prevent condensation of water vapor onto the frozen brain samples.

FIG. 4.

Comparison of rat neocortical total CO2 (tCO2) content to arterial PCO2 (PaCO2). Rats were anesthetized with halothane and spontaneously ventilated. PaCO2 levels were stabilized by varying halothane from 1.5 to 2.5% while arterial pH and PaO2 were within normal limits. After 1 h at desired PaCO2 level, rat brains were frozen by method of Pontén and Siesjö (27) and processed for tCO2 measurements (see text and Fig. 3). Open squares, new data determined by method described here; solid dots, data of Kjällquist et al. (14) determined by traditional Van Slyke technique. Both sets of data fit line described by equation shown, with correlation coefficient of 0.988. Individually, data show correlation coefficients of 0.989 (solid dots) and 0.948 (open squares) to similar lines.

To measure tCO2, 300 μl of 150 mM sodium fluoride (previously adjusted to pH 7 with sodium hydroxide) was placed in a 10-ml test tube. A brain sample (20–100 mg) was then added to the tube immediately followed by 2 ml of light mineral oil. Next, 100 μl of 1 M HCl was gently added to the aqueous layer. Finally, the active surface of the CO2 electrode was carefully lowered into the aqueous phase. Then, as the entire system warmed back to room temperature and HCl penetrated the sample to liberate CO2 gas, electrode output rose to a peak over 15–30 min (Fig. 3). Immediately before each tCO2 measurement the CO2 electrode was calibrated as shown in Fig. 3. Figure 4 shows the relation of tCO2 to PaCO2 and illustrates the similarity of our results compared with those of Kjällquist et al. (14) who used the traditional Van Slyke technique. When both sets of data are combined, tCO2 can be related to PaCO2 by

FIG. 3.

Response of CO2 electrode during total CO2 (tCO2) measurement. Three hundred microliters of 150 mM sodium fluoride was placed in a test tube. Approximately 100 mg of frozen (−25°C) rat neocortex was then added to tube and immediately covered by 2 ml of light mineral oil. Then 100 μl of 1 M HCl was injected into aqueous phase. Next CO2 electrode was calibrated in a humidified 5% and 100% CO2 gas stream and subsequently placed into aqueous phase of sample (indicated by “sample” above). PCO2 dropped initially and then slowly reached a peak value over 15–25 min as brain was titrated to CO2 and sample returned to room temperature. Here a 110-mg sample of neocortex (from animal with arterial PCO2 of 90 Torr) produced a final PCO2 of 95 Torr. This is consistent with tCO2 of 19.9 mmol/kg neocortex (see text for details of calculations and Fig. 4 for tCO2 comparison to arterial PCO2).

| (8) |

with a correlation coefficient of 0.988. tCO2 (mmol/kg) can be used to estimate neocortical total content (mmol/kg) as previously described (38)

| (9) |

where S′PtCO2 represents dissolved CO2 and arterial is calculated by the Henderson-Hasselbalch equation from arterial pH and PaCO2. Brain blood volume is estimated to be 0.03 of the total brain volume, and 0.8 is a conversion factor to change liters to kilogram of brain (38).

RESULTS

Rats were divided into two groups, one with a blood glucose of 6–8 mM (normoglycemic) and the other with a blood glucose of 18–75 mM (hyperglycemic). Preischemic blood (Table 1) and brain (Table 2) physiological variables were similar in all animals. Table 1 shows that animals were normoxic and normothermic and had normal hematocrits; the mild respiratory acidosis and slightly low systolic blood pressure level reflect that animals had adequate levels of halothane anesthesia.

TABLE 1.

Blood physiological variables

| Preischemia |

||

|---|---|---|

| Normoglycemia | Hyperglycemia | |

| n | 3 | 7 |

| pH | 7.29±0.03 | 7.23±0.02 |

| PaCO2, Torr | 64±9 | 67±3 |

| PaO2, Torr | 98±5 | 111±6 |

| Glucose, mM | 6–8 | 18–75 |

| Hematocrit, % | 40±1 | 44±1 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 102±1 | 99±1 |

| Rectal temperature, °C | 37±0.5 | 37±0.5 |

Values are means ± SE. PaO2, arterial PO2; PaCO2, arterial PCO2.

TABLE 2.

Brain physiological variables

| Normoglycemia (n = 3) |

Hyperglycemia (n = 7) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preischemia | Ischemia | Preischemia | Ischemia | |

| pHo | 7.22±0.02 | 6.79±0.02 | 7.22±0.02 | 6.19±0.02 |

| [H+]o, nM | 60±2 | 164±8 | 61±2 | 657±3 |

| PtCO2, Torr | 74±9 | 99–186 | 80±3 | 389±9 |

| Lactate, mmol/kg brain | 7.54–12.12 | 19.31–30.89 | ||

| , mM | 28.5±2.7 | 11.9–21.9 | 31.3±1.6 | 12.3±0.7 |

| , mmol/kg brain | 14.2±0.3 | 13.2–11.8 | 14.2±0.3 | 6.3±0.2 |

| tCO2, mmol/kg brain | 16.8±1.4 | 17.2±0.3 | ||

Values are means ± SE. PtCO2, tissue PCO2; tCO2, total CO2; subscript o, interstitial; subscript t, total.

Preischemic rat brain PtCO2 levels (Table 2) were slightly higher (6–7 Torr) than expected from predictions based on arteriovenous PCO2 values (7) or a recent PtCO2 microelectrode study (11). On the other hand, the differences between PtCO2 and PaCO2 reported here are in close agreement to those where brain PtCO2 was measured with a mass spectrometer-based electrode (33). The higher PtCO2 values found with our surface electrode (Table 2) or by means of mass spectroscopy (33) may have occurred because of tissue compression (and resultant diminished blood flow and CO2 accumulation) from the relatively large electrodes that were used. Should actual preischemic PtCO2 be 6–7 Torr lower than reported here, potential error in peak PtCO2 levels would be <20 Torr because the millivolt change in PtCO2 electrode output would be unaffected (Eq. 2; Fig. 6). Similarly, such an error in PtCO2 would mean a concomitant error of <1 mM in peak values (Eq. 4; Fig. 8). The resolution of both the [H+]o and PtCO2 measurements is better than 1 mV or 0.02 pH and 2 Torr, respectively.

FIG. 6.

Comparison of peak changes in interstitial [H+] ([H+]o) and tissue PCO2 (PtCO2,) with lactate production during complete ischemia. Top graph: peak change in [H+]o measured with ion-selective micropipette compared with lactate assessed by enzyme fluorometric techniques from neocortex frozen at peak change in [H+]o. Brain lactate content was modulated by preischemic systemic treatment with insulin or glucose. Peak [H+]o was bimodally distributed. A: in normoglycemia, when blood glucose ranged from 6 to 8 mM and lactate ranged from 7.54 to 12.12 mol/kg, [H+]o rose to constant peak of 6.79 ± 0.02 (n = 3). B and C: transition zone shaded by diagonal lines to reflect variability of peak [H+]o levels there. Black dots, simultaneous [H+]o and PtCO2 measurements; triangles, [H+]o data from analogous experiments in Ref. 19. D: under hyperglycemic conditions, when blood glucose ranged from 18 to 75 mM and lactate ranged from 19.81 to 30.89 mmol/kg, peak [H+]o rose by constant but larger amount to reach peak level of 6.19 ± 0.02 pH (n = 7). These results indicate that [H+]o was at steady state but not equilibrium with some acid-producing brain cell compartment between 8 and 13 and 19 and 31 mmol/kg lactate. Bottom graph: simultaneous peak PtCO2, measurements. During normoglycemia (A) and mild hyperglycemia (B), peak PtCO2, values rose linearly with peak lactate content. However, between 17 and 19 mmol/kg lactate, peak PtCO2 rose abruptly and reached peak of 389 ± 9 Torr that persisted through 31 mmol/kg lactate. Constancy of peak value of PtCO2 after 19 mmol/kg lactate indicates that was probably exhausted from some ischemic brain cell pool, even though this pool continued to generate another 12 mM of lactic acid.

FIG. 8.

Interstitial peak changes after complete ischemia. Black dots, direct calculations from peak values of [H+]o and total PCO2 (PtCO2 shown by black dots in Fig. 6. A: during normoglycemic ischemia, peak rose from 11.9 to 21.9 rnM between-8 and 13 mmol/kg lactate when [H+]o was constant at 6.79 ± 0.02 pH and peak PtCO2, was linearly rising. B and C: peak began to fall when peak [H+]o and PtCO2 changed abruptly. D: , then remained constant at 12.3 ± 0.7 mM between 19 and 31 mmol/kg lactate when [H+]o and PPtCO2, were also constant.

Ischemic changes in [H+]o and PtCO2

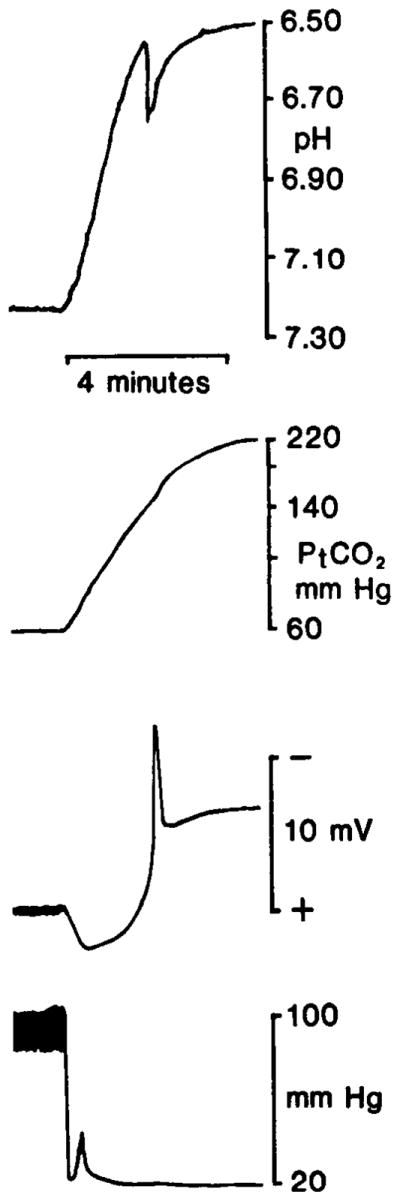

[H+]o and PtCO2 rose as soon as blood pressure fell in all animals (Fig. 5). No correlative change in PtCO2 was seen when the [H+]o showed a characteristic alkaline-going transient (15) that occurs at the time of anoxic depolarization (8). This means that, as previously speculated, fluctuations in PtCO2 are unlikely to contribute to this calcium-sensitive alkaline spike (15). Peak levels of [H+]o were bimodally distributed in relation to lactate content (Fig. 6). In spite of the fact that preischemic blood glucoses ranged from 6 to 8 mM and ischemic brain lactate contents ranged from 8 to 12 mmol/kg in normoglycemic animals, [H+]o always rose from 7.22 ± 0.02 pH by a constant amount to 6.79 ± 0.02 pH (n = 3) (Table 2). Similarly, although preischemic blood glucoses ranged from 18 to 75 mM and ischemic brain lactates ranged from 19 to 31 mmol/kg in hyperglycemic animals, [H+]o rose from 7.22 ± 0.02 pH by a constant but larger amount to 6.19 ± 0.02 pH (n = 7) (Table 2). Peak changes in Pt&, followed a somewhat different pattern. Initially, peak PtCO2 rose linearly with lactate content until the latter reached 17 mmol/kg (Fig. 6). Peak PtCO2 then rose abruptly to 389 ± 9 Torr (n = 7) by 19 mmol/kg lactate and remained constant through 31 mmol/kg lactate.

FIG. 5.

Interstitial [H+] ([H+]o) and tissue PCO2 (PtCO2) changes recorded simultaneously during complete ischemia. Typical recording of [H+]o (top trace) and accompanying DC signal (3rd trace from top) is shown from double-barreled H+ ISM positioned 500 μm down in parietal cortex. PtCO2, (2nd truce from top) was recorded from overlying pial surface. Animals were pretreated with systemic insulin or glucose to modulate brain preischemic carbohydrate stores and ischemic brain lactate content. In this case, preischemic blood glucose was 20 mM. After cardiac arrest, brain lactate content reached a peak of 16.95 mol/kg neocortex. Both [H+]o and PtCO2 rose as soon as blood pressure fell from cardiac arrest (bottom trace). In this case, [H+]o began at 7.25 pH and reached a peak of 6.47 pH after ~5 min of ischemia while PtCO2 began at 63 Torr and reached a peak of 220 Torr over same period. Characteristic alkaline-going transient in [H+]o that occurs after cardiac arrest shows no relation to PtCO2 record but is precisely correlated with large negative DC shift of anoxic depolarization (3rd trace from top). Latter is known to occur when massive amounts of Na+ leave interstitial space.

Titration of brain H+ buffers is generally thought to occur simultaneously in response to an acid load (37). Comparison of changes in PtCO2 to lactate generated during brain ischemia suggests that this may not always be true. If the change in PtCO2 is plotted against lactate content, a graph as shown in Fig. 7 is seen. The linearly rising portion of this graph can be described by a straight line [ΔPtCO2 = 11.9 (lactate) − 42.33] with a correlation coefficient of 0.976. This line can then be extrapolated to zero change in PtCO2 to suggest that 3.6 mmol/kg lactate accumulated before a change in PtCO2 was seen. Preischemic lactate content is ~1 mmol/kg in anesthetized and spontaneously breathing animals (19). Hence, ~2.6 mmol/kg lactic acid was generated before a change in PtCO2 occurred. This means that 2.6 mmol/kg of some other H+ buffer was first exhausted before brain was titrated. Phosphocreatine (PCr) is a storage form of ATP that phosphorylates ADP via creatine kinase (Crk) according to

FIG. 7.

Changes in tissue PCO2 (PtCO2) compared with lactate content during complete ischemia. Amount of lactate generated in complete ischemia before brain stores began to be titrated can be estimated by extrapolating above data to zero change in PtCO2. Five data points (black dots) between 8 and 17 mmol/kg lactate fit straight line (correlation coefficient 0.976) that is described by: PtCO2 = 11.9 (lactate) −42.3. This equation describes a line that intercepts Y-axis at 3.6 mmol/kg lactate. However, since normal preischemic lactate content is ~1 mmol/kg neocortex (see Ref. l9), this equation predicts that 2.6 mmol/kg lactate were generated in complete ischemia before began to be titrated to CO2. Therefore, at least at start of accumulation of excess H+ during ischemia, physicochemical H+ buffers can be used in succession rather than simultaneously as is most often assumed to occur. Identity of this initial H+ physicochemical buffer remains unknown, However, depletion of high-energy phosphates (PCr/ATP) would account for H+ buffering of ~2 mmol/kg lactic acid, and therefore PCr/ATP H+ buffering seems a likely source to account for first 2.6 mmol/kg of lactic acid generated.

| (10) |

This reaction has a free energy of zero, and therefore a rise in ADP or [H+] will promote formation of ATP and creatine (Cr) (36). However, since ATP hydrolysis is associated with release of H+ on a mole for mole basis, net H+ titration via PCr stores should be equivalent to PCr content minus ATP content. PCr stores are ~5 mmol/kg and ATP stores are ~3 mmol/kg in rat brain (19, 36). Hence, PCr should buffer ~2 mM of excess lactic acid. The considerations suggest that PCr first buffers excess lactic acid before begins to do the same after an accumulation of ~2–3 mmol/kg lactate.

Changes in brain

CO2 is a highly diffusible gas in tissues and crosses intact membranes rapidly (21). Therefore, PtCO2 will rise when stores are titrated in any isolated compartment of a closed system, such as the brain during complete ischemia. PtCO2, measurements when combined with simultaneous measurements of [H+]o during complete ischemia allow one to predict remaining (according to Eq. 3 or 4). In addition, the amount of neutralized by lactic acidosis can be predicted from changes in PtCO2, (where [ ] lost is equal to the change in PtCO2, times S′). We will deal with these two variables separately.

Changes in PtCO2, suggest how [H+]o could remain constant between 8 and 12 and 19 and 31 mmol/kg lactate (Fig. 6). Between 8 and 12 mmol/kg lactate, when PtCO2, rose linearly but [H+]o remained constant, calculated (Eq. 3 or 4) must have increased from 11.9 to 21.9 mM (Fig. 8). Then, after transitional changes (between 12 and 19 mmol/kg lactate), [H+]o and PtCO2, remained constant; at that point, must have remained constant at 12.3 ± 0.7 mM (Fig. 8; n = 7; Table 2). Above 19 mmol/kg lactate, must have been exhausted in any cells that continued to produce lactic acid if additional intracellular H+ buffers in such cells were less plentiful than and if such additional buffers possessed ionization equilibrium constants less than or near that of the system. These considerations imply that H+ and H+-related ionic species (such as ) may remain heterogeneously distributed between acid- and nonacid-producing compartments during hyperglycemic and complete ischemia.

PtCO2 (Fig. 6) and , measurements can be used to estimate the pH and size of the unknown compartment, respectively. If stores in the unknown compartment were exhausted to <l mM (as discussed above) while PtCO2, was 389 Torr, pH can be predicted from Eq. 3 or 4 to be <5.2 in the compartment that continued to generate lactic acid >19 mmol/kg lactate. Also, the amount of lost during complete ischemia is equal to the measured change in PtCO2, multiplied by S′ and 0.8 (a multiplication factor to convert mM to mmol/kg) (Fig. 9). Accordingly, since 6.3 mmol/kg , remained in brain tissue at lactate values >19 mmol/kg lactate (Fig. 9; Table 2), the size of the unknown compartment can be estimated. If remaining was distributed homogeneously, the size of the unknown compartment lacking would be ~36% of neocortical space; e.g., 6.3 mmol/kg brain is equivalent to 7.9 mM and 7.9 mM/12.3 mM is equal to 64%, representing the size of the space containing the remaining where the [ ] is 12.3 mM.

FIG. 9.

Changes in neocortical total content compared with lactate content during complete ischemia. Dashed lines, preischemic neocortical , content of 14.2 ± 0.3 mmol/kg (n = 12) that is characteristic for rats anesthetized and spontaneously breathing with arterial PCO2’s as shown in Table 1. Graph shows result of subtracting calculated lost from conversion to CO2 during ischemia from preischemic level of 14.2 mmol/kg. Such calculations show that, above 19 mmol/kg lactate, 6.3 ± 0.2 mmol/kg of , were left in ischemic neocortices in spite of continued accumulation of lactate to 31 mmol/kg.

DISCUSSION

Previously, studies of brain during complete ischemia (37) considered the organ to behave as a homogeneous proteinaceous ionic milieu, but this no longer seems likely. In this study we used simultaneous measurements of PtCO2, and [H+]o as well as measurements of to illustrate peak changes in the behavior of carbonic acid buffer species during brain ischemia. Our results suggest that both and H+ remain heterogeneously distributed within brain during (hyperglycemic) complete ischemia with lactate accumulation >19 mmol/kg. Such a distribution for these ions must exist between ischemic interstitial space and some population of intact cells that continue to generate lactic acid.

Heterogeneous distribution of H+ and in ishernia

The finding of an ischemic-bimodal distribution for [H+]o in comparison to a progressively climbing tissue lactate content (Fig. 6) led us to propose a model for ischemic brain H+ homeostasis (19). This model emphasizes for the first time the possible activity of plasma membranes during ischemia. Briefly stated, the model has four components under normal conditions. First, excess H+ ultimately leaves neurons via Na+-H+ or antiports (31, 42) or as CO2. Second, glial cells handle excess H+ similarly except that Na+-H+ and antiport systems are segiegated to different sides of the glial cells, the first facing capillaries and the second facing the neurons (13). In this way, the acceleration of CO2 hydration by carbonic anhydrase (32) will promote loss of H+ to blood via Na+-H+ antiport and return of to the interstitial space and neurons via antiport (13). Third, antiport can be directed inward or outward, as in erythrocytes (4), in order to neutralize excess H+ to CO2 on either side of the glial cell membrane. Fourth, power to complete Na+-H+ exchange (and perhaps exchange; see Refs. 31,42) comes from the Na+ gradient, which is maintained by Na+-K+-ATPase and a selective plasma membrane impermeability to Na+.

During complete ischemia with the absence of blood flow, the model can be conceptualized as a three-compartment system, consisting of neurons, glia, and the interstitial space, where each compartment is bounded by plasma membranes as described above. [Na+]o drops by ~106 mM during complete ischemia (9), and neurons (and probably glia) are depolarized (8). Thus the combination of a diminished transmembrane Na+ gradient and the absence of membrane polarization may prevent egress of excess H+ from acidotic brain cells via Na+-H+ antiport (19). Instead, only antiport would be expected to shuttle H+ across compartment boundaries, although there is also known to be a drop in [Cl−]o to ~72 mM (9). Finally, when , stores are sufficiently exhausted in hyperglycemic ischemia, excess H+ would have no means of leaving intact brain cells, thus leaving only intracellular physicochemical H+ buffers to lessen rising [H+]. The PtCO2,-[H+]o results reported here support this model with one refinement.

Measurements of tCO2, and estimated loss of compared with the amount of lactic acid generated (Fig. 9) allow us to propose that the remaining in brain, if distributed homogeneously, would be confined to 64% of the neocortical space under hyperglycemic conditions. Estimates of the relative volumes of neurons, glia, and the interstitial space in rat neocortex suggest that the three compartments account, respectively, for 52.5, 32.5, and 15% of the whole (10). Since some remains in the interstitial space at and above 19 mmol/kg lactate (i.e., [H+]o is 6.18–6.19 pH while PtCO2 is 389 Torr), the interstitial space would have to equilibrate with a compartment the size of intraneuronal space to account for an of 12.3 mM, if remaining were homogeneously distributed. A homogeneous distribution is the most economical assumption, and if true, would mean that [H+] would be the same in both interstitial and intraneuronal space (i.e., 6.18–6.19 pH) at 19–31 mmol/kg lactate because PtCO2 should also be equivalent in both compartments. [H+] in the unknown compartment, which may be glia, is likely to be significantly more acidic than interstitial space. The latter conclusion stems from the observation that lactic acid was generated above a level of 19 mmol/kg lactate in a brain space in which stores were exhausted and PtCO2 was 389 Torr. Therefore, [H+] in this compartment was >5.2 pH while intraneuronal [H+]o was presumably 6.18–6.19 pH (i.e., identical to [H+]o,). Note that at this point considerable remained in the neocortex. In fact, if all stores were neutralized to CO2, PtCO2, would have risen to ~636 Torr (PtCO2 = tCO2/0.8 S′, where tCO2 is 17.2 mmol/kg at PaCO2 of 67 Torr).

The unchanging level of [H+]o at 6.18–6.19 pH during hyperglycemic and complete ischemia originally led us to assume that all brain cells might be impermeable either to excess H+ or their ionic determinants (40) >19 mmol/kg lactate (19). In light of the plateau of peak PtCO2 at 389 Torr (Fig. 6), we must now refine this assumption to suggest that excess H+ is likely to be confined to 36% of total neocortical space, a volume that is close to that of glial space. We speculate that acid accumulation of glia exceeds a pH of 5.2 when lactate exceeds 19 mmol/kg. This level of lactate accumulation previously has been correlated with infarction of brain after nearly complete ischemia (29). Recently, astrocytes in culture were shown to be irreversibly injured when exposed to solutions of 5.2 pH for 10 min (25), a value consistent with our calculations.

Implications toward glial function

Restriction of excess H+ to glial space above 19 mmol/kg lactate has important implications toward the physiological and biochemical behavior of ischemic brain. Such a restriction implies that anaerobic glycolysis ceases above 19 mmol/kg lactate in neurons. This follows because no further fall in or rise in PtCO2 occurred after this level of lactate accumulation, although remained in 64% of neocortical space. Cessation of neuronal lactic acid production might result from exhaustion of neuronal glucoses stores or a lack of glucose transport out of glia or into neurons. The mechanism of glucose transport across glial and neuron to membranes, although thought to occur via facilitated diffusion, remains speculative (2). In addition, why should such transport stop at 19 mmol/kg lactate? Alternatively, glucose utilization could stop because acidosis inhibited glycolytic enzymes (36). Such an interpretation would require postulating a different [H+] sensitivity of glycolytic enzymes in neurons compared with glial cells.

The potential importance of glia toward maintaining brain acid-base homeostasis under normal and ischemic conditions has been recognized in the past (13, 36). However, H+-related changes in glial plasma membrane function during ischemia have not been stressed and could account for the PtCO2 and [H+]o results reported here. Under normoglycemic conditions (Figs. 6A and 8A) [H+]o remained constant in the face of rising PtCO2 and . We believe that this resulted from net secretion of to the interstitial space from astroglia. Net secretion of changed to net absorption (Figs. 6, B and C, and 8, B and C), perhaps as glial lactic acid production became predominant. Finally, net absorption and titration of stopped at 19 mmol/kg lactate. Why absorption should stop before all is neutralized to CO2, in spite of continued lactic acid production, remains unclear. However, evidence indicates that acid extrusion from barnacle muscle is reduced from 2.5 to <0.05 nM/min when [H+10 is raised from 8.6 to 6.8 pH (3). If a similar phenomenon occurs in glia, acid extrusion might stop completely when [H+]o rose from its preischemic level of 7.22 to 6.18–6.19 pH.

Several pieces of evidence support these postulated aspects of glial cell function during hyperglycemic ischemia. First, astrocytes maintain impermeable plasma membranes to diffusion of Na+ and Cl− when exposed to [K+]0 of 54 mM in tissue culture and might also maintain an impermeability to Na+ and Cl− in vivo during ischemia when [K+]0 is known to rise to similar levels (45). Second, membrane electrical resistance of glia does not change during spreading depression (41) in spite of interstitial ion concentration changes (24) similar to those that occur during ischemia (9). Therefore, although probably depolarized during ischemia, glia may also maintain membrane electrical resistance (and concurrently, impermeability to ionic diffusion) during ischemia (19). Finally, we speculate that intraglial pH can fall to <5.2 pH. We previously provided evidence that ischemic brain can generate an interstitial pH (pHo) as low as 5.4 (17). Under severely hyperglycemic conditions (blood glucose 17–75 mM) pHo fell to 6.1–6.2 after 30 min of near complete ischemia. With recirculation, pHo then fell abruptly to as low as 5.4. Brain is known to swell with reperfusion from severe incomplete ischemia (l2), and membrane permeability of edematous acid-producing cells may rise. If so, increased plasma membrane permeability to H+ or its ionic determinants (15, 19,40) could cause the second fall in pHo to 5.4. Finally, since pHo did not fall below ~6.1–6.2 during 30 min of incomplete ischemia, membrane impermeability to H+ or its ionic determinants either in glial cells or some other less likely compartment must persist for this time period.

Deterioration of the cooperative interaction between glial cells and neurons with respect to glucose utilization and waste (i.e., H+ and CO2) removal via membrane transport mechanisms may be a fundamental step in the pathogenesis of irreversible injury of brain from ischemia (23). The present results show an abrupt deterioration in acid-base homeostasis at a range of lactate accumulation (13–19 mmol/kg) that previously has been correlated with the transition from a selective loss of vulnerable neurons (28) to brain infarction (30). Furthermore, our results implicate glia as both the final site of continued acid production and the repository of its lethal accumulation in ischemic brain.

FIG. 10.

Schematic of heterogeneous distribution of H+ and during hyperglycemic and complete ischemia. In complete ischemia, absence of blood flow prevents egress of excess CO2 and H+-related ionic species from brain to blood. Thus brain can be regarded as 3-compartment system consisting of neurons, glia, and interstitial space (ISS) where each compartment is bounded by plasma membranes. Movement of excess H+ across such membranes is likely to occur via some combination of electroneutral Na+-H+ (1 and 3) and (2 and 4) exchange transport. Both transport systems may be powered by transmembrane Na+ gradient under normal conditions. In ischemia, large drop in interstitial [Na+] and [Cl−] occurs, probably through entry of Na+ and Cl− into neurons. Diminished interstitial [Na+] may prevent egress of excess H+ via Na+-H+ antiport in neurons (1) and glia (3). Furthermore, loss of membrane potential and fall in membrane resistence in neurons (shown by dashed line to neuronal membrane) during ischemia may indicate that small ions (such as ) equilibrate between neuronal and interstitial space. If so, [H+] would be same in both compartments because highly permeable CO2 can be expected to be similar throughout all brain compartments. Support for this latter assumption comes from total measurements, which show that , after hyperglycemic and complete ischemia is distributed in 64% of neocortical space, if it is distributed homogeneously (shown by diagonal lines). This volume is nearly equivalent to ISS plus neuronal space. , measurements further suggest that, above 19 mmol/kg lactate, continued anaerobic glycolysis occurred in compartment that occupied 36% of neocortical space, had exhausted its stores, and therefore may have had an internal pH of <5.2 and was surrounded by membranes that were impermeable to H+ and H+-related ionic species. This compartment is likely to be glia. Why glial antiport (4) should stop before all is titrated to CO2 is unknown but may be related to [H+] sensitivity of antiport as well as continued integrity of glial plasma membranes.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Charles Nicholson for helpful discussions about hydrogen homeostasis in brain.

This study was supported by the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke Grants NS-19108, NS-00346, and RR-05396-23 and by Teacher Investigator Development Award NS-00767 to R. P. Kraig.

Footnotes

pH is taken here to equal the negative logarithm of the [H+] instead of the more technically correct equation of pH to a millivolt standard (31). This is done to allow comparison of biological pH measurements to [H+], which we feel is a more informative biological variable.

References

- 1.Ammann D, Lanter F, Steiner RA, Schulthero P, Shijo Y, Simon W. Neutral carrier based hydrogen in a selective microelectrode for extra and intracellular studies. Anat Chem. 1981;53:2267–2269. doi: 10.1021/ac00237a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bachelard HS. Transport of hexoses and monocarboxylic acids. In: Lajtha A, editor. Handbook of Neurochemistry. Metabolic Turnover in the Nervous System. 2. Vol. 5. New York: Plenum; 1983. pp. 339–354. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boron WF, McCormick WC, Roos A. pH regulation in barnacle muscle fibers: dependence on intracellular and extra-cellular pH. Am J Physiol. 1979;237:C185–C193. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1979.237.3.C185. Cell Physiol. 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cabantchik ZI, Knauf PA, Rothstein A. The anion transport system of the red blood cell. Biochem Biophys Acta. 1978;515:239–302. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(78)90016-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen JJ, Kassirer JP. Acid-Base. Boston, MA: Little, Brown; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Edsall JT, Wyman J. Biophysical Chemistry. New York: Academic; 1958. p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gleichman V, Ingvar DH, Lübbers DW, Siesjö BK. Tissue PO2 and P CO2 of the cerebral cortex related to blood gas tensions. Acta Physiol Scand. 1962;55:127–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1962.tb02425.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grossman RG, Williams VF. Electrical activity and ultra structure of cortical neurons and synapses in ischemia. In: Brierley JB, Meldrum BS, editors. Brain Hypoxia. New York: Lippincott; 1971. pp. 61–75. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hansen AJ. Extracellular in concentrations during cerebral ischemia. In: Zeuthen T, editor. The Application of Ion-Selective Microelectrodes. New York: Elsevier/North-Holland; 1981. pp. 239–254. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hertz L, Schousboe A. Ion and energy metabolism of the brain of the cellular level. In: Pfeiffer CC, Smythies JR, editors. International Review of Neurobiology. Vol. 18. New York: Academic; 1975. pp. 141–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hogg RJ, Pucacco LR, Carter NW, Laptook AR, Kokko JP. In situ PCO2 in the renal cortex, liver, muscle, and brain of the New Zealand White Rabbit. Am J Physiol. 1984;247:F491–F498. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1984.247.3.F491. (Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol. 16) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kalimo H, Rehncrona S, Soberfeldt B, Olson Y, Seisjö BK. Brain lactic acidosis and ischemic cell damage. 2. Histopathology. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1981;1:313–327. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1981.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kimelberg HK, Bourke RS, Steig PE, Barron KO, Hirata H, Pelton EW, Nelson LR. Swelling of astroglia after injury to the central nervous system: mechanisms and consequences. In: Grossman RG, Gildenberg PL, editors. Head Injury: Basic And Clinical Aspects. New York: Raven; 1982. pp. 31–44. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kjällquist A, Nardini M, Siesjö BK. The regulation of extra- and intracellular acid-base parameters in the rat brain during hyper- and hypocapnia. Acta Physiol Scand. 1969;76:485–494. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1969.tb04495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kraig RP, Ferreira-Filho CR, Nicholson C. Alkaline and acid transients in the cerebellar microenvironment. J Neurophysiol. 1983;49:831–850. doi: 10.1152/jn.1983.49.3.831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kraig RP, Pulsinelli WA, Plum F. Carbonic acid buffer behavior in brain during complete ischemia (Abstract) Soc Neurosci Abst. 1984;10:888. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kraig RP, Pulsinelli WA, Plum E. Peak forebrain [H+]o in severe hyperglycemic ischemia (Abstract) Stroke. 1985;16:143. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kraig RP, Pulsinelli WA, Plum F. Heterogeneous distribution of hydrogen and bicarbonate ions during complete brain ischemia. In: Hossman KA, Siesjö BK, Welsch FA, Kogure K, editors. Progress in Brain Research. Mechanisms of Ischemic Brain Injury. Vol. 63. Amsterdam: Elsevier/North-Holland; 1985. pp. 155–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kraig RP, Pulsinelli WA, Plum F. Hydrogen ion buffering in brain during complete ischemia. Brain Res. 1985;342:281–290. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)91127-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kraig RP, Pulsinelli WA, Plum F. Behavior of brain bicarbonate ions during complete ischemia (Abstract) J Cereb, Blood Flow Metab. 1985;5:S227–S228. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krogh A. The rate of diffusion of gases through animal tissues, with some remarks on the coefficient of invasion. J Physiol Lond. 1919;51:391–403. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1919.sp001838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mitchell RA, Herbert DA, Carman CT. Acid-base constants and temperature coefficients for cerebrospinal fluid. J Appl Physiol. 1965;20:27–30. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1965.20.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Myers RE. Lactic acid accumulation as a cause of brain edema and cerebral necrosis resulting from oxygen deprivation. In: Korbkin R, Guilleminault G, editors. Advances in Perinatal Neurology. New York: Spectrum; 1979. pp. 85–114. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nicholson C, Kraig RP. The behavior of extracellular ions during spreading depression. In: Zeuthen T, editor. The Application of Ion-Selective Microelectrodes. New York: Elsevier/North-Holland; 1981. pp. 217–238. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Norenberg MD, Mozes LW, Gregorios JB. Effect of lactic acid on primary astrocyte cultures (Abstract) J Neuropath Exp Neurol. 1985;44:38. doi: 10.1097/00005072-198507000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Plum F. What causes infarction of ischemic brain? Neurology. 1983;33:222–233. doi: 10.1212/wnl.33.2.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pontén U, Siesjö BK. A method for the determination of the total carbon dioxide content of frozen tissues. Acta Physiol Scand. 1964;60:297–308. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1964.tb02893.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pulsinelli WA, Duffy TE. Regional energy balance in rat brain after transient forebrain ischemia. J Neurochem. 1983;40:1500–1503. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1983.tb13599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pulsinelli WA, Levy DE, Sigsbee B, Scherer P, Plum F. Increased damage after ischemic stroke in patients with hyperglycemia with or without established diabetes mellitus. Am J Med. 1983;74:540–544. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(83)91007-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pulsinelli WA, Waldman S, Rawlinson D, Plum F. Moderate hyperglycemia augments ischemic brain damage: a neuropathologic study in the rat. Neurology. 1982;32:1239–1246. doi: 10.1212/wnl.32.11.1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roos A, Boron WF. Intracellular pH. Physiol Rev. 1981;61:296–434. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1981.61.2.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sapirstein VS. Carbonic anhydrase. In: Lajtha A, editor. Handbook of Neurochemistry. 2. Vol. 4. New York: Plenum; 1983. pp. 385–402. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seylaz J, Pinard E, Meric P, Correze JL. Local cerebral PCO2, PCO2, and blood flow measurements by mass spectrometry. Am J Physiol. 1983;245:H513–518. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1983.245.3.H513. Heart Circ. Physiol. 14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Siesjö BK. The solubility of carbon dioxide in cerebral cortical tissue from rat at 37.5°C. With a note on the solubility of carbon dioxide in 0.16M NaCl and cerebrospinal fluid. Acta Physiol Scand. 1962;55:325–341. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1962.tb02447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Siesjö BK. The bicarbonate/carbonic acid buffer system of the cerebral cortex of cats, as studied in tissue homogenates. II. The pK1 of carbonic acid at 37.5°C, and the relation between carbon dioxide tension and pH. Acta Neurol Scand. 1962;38:121–141. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1962.tb01083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Siesjö BK. Bruin Energy Metabolism. New York: Wiley; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Siesjö BK. Brain acid-base metabolism in health and disease. In: Bes A, Paoletti R, Siesjö BK, editors. Cerebral Ischemia. Amsterdam: Excerpta Med; 1984. pp. 157–165. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Siesjö BK, Messeter K. Factors determining intracellular pH. In: Siesjö BK, Sorenson SC, editors. Ion Homeostasis of the Brain. Copenhagen: Munksgaard; 1971. pp. 244–262. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Siggaard Andersen O. The first dissociation exponent of carbonic acid as a function of pH. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1962;14:587–597. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stewart P. How to Understand Acid-Base. New York: Elsevier; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sugaya E, Takato M, Noda Y. Neuronal and glial activity during spreading depression in cerebral cortex of cat. J Neurophysiol. 1975;38:822–841. doi: 10.1152/jn.1975.38.4.822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thomas RC. Experimental displacement of intracellular pH and the mechanisms of its subsequent recovery. J Physiol Land. 1984;354:3P–22P. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vannucci RL, Duffy TE. Influence of birth on carbohydrate and energy metabolism in rat brain. Am J Physiol. 1974;226:933–940. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1974.226.4.933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Van Slyke DD. On the measurement of buffer values and on the relationship of buffer value to the dissociation constant of the buffer and the concentration and reaction of the buffer solution. J Biof Chem. 1925;52:525–570. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Waltz W, Hertz L. Intracellular ion changes of astrocytes in response to extracellular potassium. J Neurosci Res. 1983;10:411–423. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490100408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]