Abstract

Background

Tissue plasticity and a substantial regeneration capacity based on stem cells are the hallmark of several invertebrate groups such as sponges, cnidarians and Platyhelminthes. Traditionally, Acoela were seen as an early branching clade within the Platyhelminthes, but became recently positioned at the base of the Bilateria. However, little is known on how the stem cell system in this new phylum is organized. In this study, we wanted to examine if Acoela possess a neoblast-like stem cell system that is responsible for development, growth, homeostasis and regeneration.

Results

We established enduring laboratory cultures of the acoel Isodiametra pulchra (Acoela, Acoelomorpha) and implemented in situ hybridization and RNA interference (RNAi) for this species. We used BrdU labelling, morphology, ultrastructure and molecular tools to illuminate the morphology, distribution and plasticity of acoel stem cells under different developmental conditions. We demonstrate that neoblasts are the only proliferating cells which are solely mesodermally located within the organism. By means of in situ hybridisation and protein localisation we could demonstrate that the piwi-like gene ipiwi1 is expressed in testes, ovaries as well as in a subpopulation of somatic stem cells. In addition, we show that germ cell progenitors are present in freshly hatched worms, suggesting an embryonic formation of the germline. We identified a potent stem cell system that is responsible for development, homeostasis, regeneration and regrowth upon starvation.

Conclusions

We introduce the acoel Isodiametra pulchra as potential new model organism, suitable to address developmental questions in this understudied phylum. We show that neoblasts in I. pulchra are crucial for tissue homeostasis, development and regeneration. Notably, epidermal cells were found to be renewed exclusively from parenchymally located stem cells, a situation known only from rhabditophoran flatworms so far. For further comparison, it will be important to analyse the stem cell systems of other key-positioned understudied taxa.

Background

The question how adult organisms maintain their tissue homeostasis or perform wound healing and regeneration after injury touches different biological and medical research areas. The two main invertebrate model organisms, Drosophila melanogaster and Caenorhabditis elegans are largely post-mitotic and therefore cannot serve as model systems for tissue renewal nor for the biology of somatic stem cells. Vertebrate stem cell systems have been addressed because of their medical relevance, but the accessibility of these stem cell systems is limited. Flatworms are well known for their remarkable totipotent stem cell system. These stem cells (so called neoblasts) are the sole source for cell renewal during homeostasis, development and regeneration [1-8], and give rise to all cell types including germ cells [9,10]. A basal member of the Platyhelminthes - the Acoela - became separated from other flatworms [11-20] by molecular phylogeny and were placed as a sistergroup to all Bilateria [16,19,20], associated with the Deuterostomes [17] or located within the Lophotrochozoa [18]. Already 20 years ago, the question whether acoel flatworms are "Kingpins of Metazoan evolution or specialized offshoot" [21] has been raised by summarizing data of a century of morphological analyses where Acoelomorpha have been associated to the phylum Platyhelminthes [22]. By contrast, recent data on the distribution and proliferation of stem cells and the specific mode of epidermal replacement could constitute for a possible synapomorphy between the Acoela and the major group of flatworms, the Rhabditophora [19]. Like rhabditophoran flatworms, certain acoels exhibit tremendous capacity to regenerate lost body parts [23,24] or show modes of asexual reproduction such as reverse-polarity budding [25,26].

Despite the growing interest in acoel phylogeny, knowledge on the developmental biology of this taxon is limited. Few reports described the embryonic muscle development [27], the characteristic spiral duet cleavage [28], while others examined their stem cell system and showed that acoels possess also neoblasts which resemble stem cells of rhabditophoran flatworms [19,29,30]. However, very little is known on the cellular and molecular basis that is driving homeostasis, asexual reproduction and regeneration in these organisms. Research on acoels has been hampered by the availability of an acoel species that can be cultured and used as a suitable model system. Here we present the acoel Isodiametra pulchra (Acoela, Acoelomorpha) as an adequate species to address developmental and evolutionary questions. I. pulchra has several advantages to perform these analyses: (1) long term laboratory cultures can be maintained, (2) the animals are small in size (1 mm), (3) reproduce rapidly (one egg per animal per day the whole year through), (4) have a very short embryonic development (36 hours) [27], (5) a short generation time (one month), (6) 14.000 ESTs have been sequenced (Ladurner and Agata, unpubl.), and (7) in situ hybridization and RNA interference protocols are established (see below).

The last decennia, the stem cell system of flatworms has been characterized on a molecular level [31-35]. Some of the well characterized stem cell regulatory genes in flatworms belong to the piwi-like gene family [33,34,36,37]. In most organisms studied so far, PIWI is a germline specific marker, essential in spermatogenesis, meiosis and germ cell maintenance where it is involved in transposon regulation [38-42]. An exception herein are rhabditophoran flatworms, sponges and cnidarians where piwi-like genes have been shown to play an extended role in somatic stem cells [33,36,37,43-45].

Here we show that in I. pulchra, piwi is also expressed in a subpopulation of somatic neoblasts. Next, we report on the morphology of stem cells, their distribution and differentiation capacity in this acoel species. Furthermore, we studied the function of the stem cell system during homeostasis, development, regeneration, hydroxyurea treatment, starvation and after irradiation using histology, electron microscopy, BrdU labelling, in situ hybridization and RNA interference. To summarize, these data provide new insides how stem cell systems might have been developed during animal evolution.

Results

Morphology, distribution, and differentiation of stem cells in Isodiametra pulchra

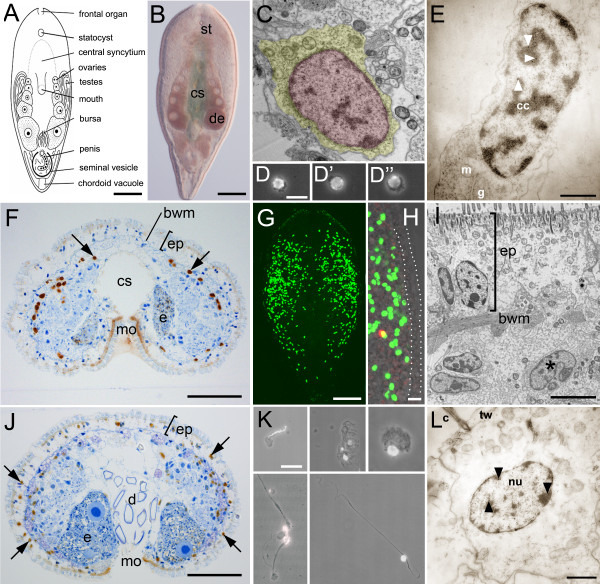

In order to describe the stem cell system of acoels, we first addressed the morphology of Isodiametra pulchra (Figures. 1A, B) neoblasts. They are small in size and possess a high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio with only a thin rim of cytoplasm (Figures. 1C, D). The nucleus consists of mostly uncondensed chromatin with few smaller clumps of condensed chromatin (Figure. 1C). When animals were macerated into a single cell suspension after a 30 min BrdU pulse, only cells with a neoblast morphology were labelled (n = 198) (Figure. 1D). On ultrastructural level, all cells that incorporated BrdU were small in size and possessed a thin rim of cytoplasm (Figures. 1E). These data suggest that neoblasts were the only dividing cells.

Figure 1.

The stem cell system of Isodiametra pulchra (A, B). Morphology (C-E), distribution (F-I), and differentiation (J-L) of neoblasts. (A) Schematic drawing. (B) Differential interference contrast image. (C) Typical neoblast with nucleus (red) and thin rim of cytoplasm (yellow). (D-D") Macerated BrdU labelled cells show typical neoblast like morphology (E) BrdU labelled neoblast, as shown by immunogold staining after a 30 min BrdU pulse; arrowheads point to gold particles (F) histological cross section; brown spots are BrdU labelled S-phase cells. (G, H) Confocal projection overview (G) and detail of lateral body margin (H) after 30 min BrdU pulse; the red spot in (H) is a mitotic figure. Note that S-phase cells were lacking in the epidermis (between dotted lines). (I) Electron microscopic image of a posterio-lateral body margin. (J) Histological section, 10 days after the initial BrdU pulse. Some of the neoblasts underwent differentiation into epidermal cells (arrows); (K) BrdU labelled cells, differentiated after 10 days chasing time. Differentiating spermatid (top left), epidermal cells (top middle), parenchymal cell (top right), nerve cells (bottom left), and a muscle cell (bottom right) (L) BrdU labelled differentiated epidermal cell after 10 days chasing; arrowheads point to gold particles. bwm, body wall musculature; c, cilium; cc, condensed chromatin; cs, central syncytium; d, diatoms; e, egg; de, developing eggs; ep, epidermis; g, golgi; m mitochondria; mo, mouth opening; n nucleolus; st, statocyst; tw, terminal web. Scale bars (A, B, G) 100 μm; (C, E, L) 1 μm; (D, H; K) 10 μm; (F, J) 25 μm; (I) 5 μm.

We next addressed the distribution of somatic stem cells in adults. BrdU labelling and ultrastructural analyses revealed a solely parenchymal distribution of S-phase cells (Figures. 1F-I). The majority of stem cells were located along the lateral sides of the animal, fewer cells were present also closer to the midline (Figures. 1F, G). Anterior to the statocyst, proliferating cells were almost completely absent. Notably, proliferating cells were never found in the epidermis of BrdU labelled animals (n = 300+) (Figures. 1F-I). These observations were further confirmed by ultrastructural investigations (Figure. 1I). Our data indicate that all epidermal cells were exclusively renewed from parenchymally located neoblasts.

We further followed the differentiation potential of BrdU labelled stem cells (Figures. 1J-L) in I. pulchra. BrdU pulse-chase experiments (Figures. 1K, L) revealed the differentiation of neoblasts into various cell types after a 10 days chase period (Figures. 1J-L). As mentioned above, all BrdU labelled cells exhibited a stem cell phenotype after 30 min BrdU exposure. After 10 days chasing time however, only 6.5% of labelled cells possessed stem cell morphology (11 out of 167) while 93.5% possessed a differentiated cell phenotype (156 out of 167).

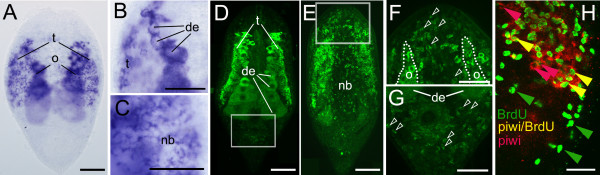

Ipiwi1 expression in adults, during regeneration and during development

Next, we analyzed the expression dynamics of piwi-like genes in Isodiametra pulchra in adults, during development, regeneration, starvation and after irradiation. From I. pulchra, we have isolated two piwi-like genes, ipiwi1 and ipiwi2 (Additional files 1 and 2, Figures. S1, S2), both comprising the conserved Piwi and Paz domains (Additional file 3, Figure. S3), which are characteristic for members of the Piwi/Ago family [46,47]. Comparable to most organisms studied so far, ipiwi2 appeared to have a germ line specific expression (Additional file 4, Figures. S4A-C). Interestingly, ipiwi1 showed in addition to the germ line, an expression pattern extended to somatic stem cells (Figure. 2), a situation only known from rhabditophoran flatworms, sponges and cnidarians [33,36,37,43-45]. Therefore we focussed in this study on ipiwi1. To localize Ipiwi1 protein, we have generated a specific polyclonal antibody (Additional file 4, Figure. S4F).

Figure 2.

Ipiwi1 mRNA expression (A-C) and protein localization (D-G) and BrdU/ipiwi1 (H) double labelling in I. pulchra. (A) Whole mount ipiwi1 in situ hybridization of an adult specimen. (B) Detail of developing eggs (de) and testes (t). (C) Dorsal focal plane showing ipiwi1 mRNA expressed in neoblasts (open arrowheads). (D, E) Confocal projections of Ipiwi1 protein localisation in testes and developing eggs (D) and in neoblasts (nb) (E). (F) Detail of the anterior region of (E) demonstrating Ipiwi1 positive cells (open arrowheads). (G) Detail of the posterior region of (D) demonstrating Ipiwi1 positive cells (open arrowheads). (H) Double staining of stem cells in S-phase (green) and ipiwi1 positive cells (red). Confocal projection (1,02 μm) shows the presence of BrdU-only labelled cells (green arrows), ipiwi1-only labelled cells (red arrows) as well as BrdU/piwi double labelled stem cells (yellow arrows). In all figures, anterior is to the top. Scale bars (A, D, E) 100 μm; (B, C, F-H) 50 μm.

In adult animals, ipiwi1 mRNA and protein were localized in a subpopulation of somatic stem cells and gonads (Figure. 2) while the sense probe did not show any signal (Additional file 4, Figure. S4D). Ipiwi1 positive cells in testes comprised two bands on the lateral sides of the animal which consisted of spermatogonia and spermatocytes (Figures. 2A, B, D). All stages of female germ cells expressed ipiwi1 including oogonia, oocytes and mature eggs (Figures. 2A, B, D). We further localized ipiwi1 mRNA expression in neoblasts in the region posterior to the statocyst but not in the posterior end of the animal (Figures. 2A, C). In contrast, few Ipiwi1 protein positive cells were also found anterior to the statocyst (Figures. 2E, F) and in the tail region (Figure. 2G). These data suggest that Ipiwi1 protein functions also in differentiating neoblasts, a situation similar to triclad flatworms [33,34,37]. Double labelling of ipiwi1 with BrdU revealed ipiwi1-only labelled cells, BrdU-only labelled cells as well as ipiwi1/BrdU double labelled stem cells (Figure. 2H). These data suggest that ipiwi1 was restricted to only a subpopulation of neoblasts.

The process of regeneration in acoel flatworms was earlier examined on both morphological and immunohistochemical level but no molecular analyses have been performed to date [23,24,26,30,48,49]. Here we show ipiwi1 expression dynamics during successive stages of tail regeneration (Figure. 3, Additional file 5, Figure. S5) (this species is not able to perform anterior regeneration). One hour after initial amputation, ipiwi1 could not be detected at the regeneration site (Figures. 3A, A'). 10 hours postamputation however, a small rim of ipiwi1 positive cells became visible below the epidermis (Figures. 3B, B'). At 25 hours after amputation, ipiwi1 was upregulated within the small blastema (Figures. 3C, C'). From 48 to 68 hours of regeneration, ipiwi1 expression was detected in neoblasts that were organized in a ring-shaped structure (Figures. 3D-F') and outlining the subsequent developing reproductive organs. Ipiwi1 expression was upregulated only locally within the regeneration blastema but not in anterior regions of the animals (Additional file 5, Figure. S5). As regeneration proceeded, blastemal cell differentiation was paralleled by a gradual decrease in ipiwi1 expression (Figures. 3F-G').

Figure 3.

Ipiwi1 mRNA expression (A-G) and protein localization (A'-G') during posterior regeneration. One hour after cutting (A, A'), ipiwi1 expression could not be detected at the regeneration site. After 10 hours, ipiwi1 was upregulated below the epidermis (arrows) (B, B'). At 25 hours postamputation (C, C') a significant proportion of cells within the regeneration blastema were ipiwi1 positive. From 48 hours onwards ipiwi1 expression and protein were present in the differentiating genital blastema (open arrows in D-F'). (G, G') After 76 h, ipiwi1 expression reached default levels. Scale bars 50 μm.

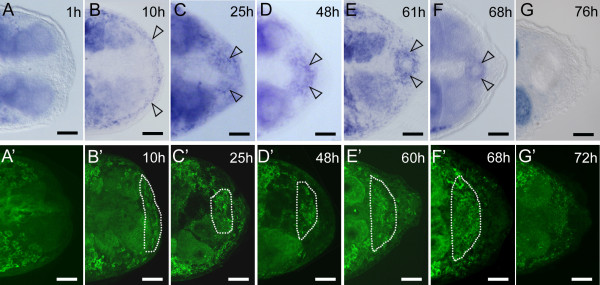

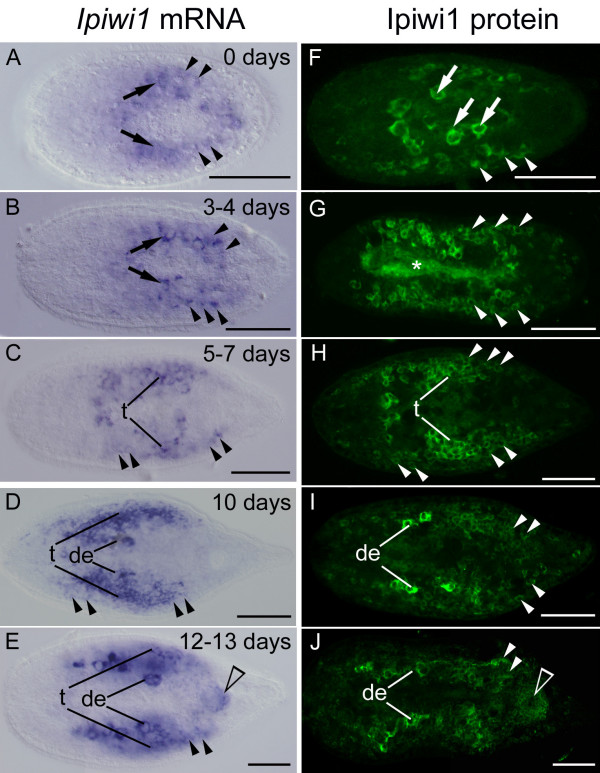

We next examined the expression of ipiwi1 throughout different stages of postembryonic development (Figure. 4). In freshly hatched I. pulchra, small parenchymally located somatic neoblasts and several larger ipiwi1 positive primordial germ cells were present in the central region of the animal (Figures. 4A, F). Those larger ipiwi1 positive cells gave rise to testes and ovaries and we confirmed the nature of these cells by double-labelling with an I. pulchra specific nanos probe (De Mulder, unpublished). The presence of primordial germ cells in freshly hatched I. pulchra suggested an embryonic segregation of the germ line in this species. The number of ipiwi1 positive cells increased up to four days post hatching (Figures. 4B, G) and distinct ipiwi1 stained testes were present after one week (Figures. 4C, H). Chains of developing eggs could be discerned after 10 days of postembryonic development (Figures. 4D, I). The number of ipiwi1 expressing somatic stem cells gradually increased during postembryonic development. A ring shaped structure of ipiwi1 positive cells accounted for the genital blastema (Figure. 4E), a structure identical to the differentiating genital blastema after 42 hours to 68 hours of regeneration (compare with Figure. 3G). The critical role of neoblasts became apparent by treatment with ipiwi1 dsRNA during development. The functional knock-down of ipiwi1 in developing worms resulted in a lethal phenotype (see below).

Figure 4.

Ipiwi1 expression (A-E) and Ipiwi1 protein (F-J) during postembryonic development of I. pulchra. In freshly hatched animals, a subset of somatic neoblasts was visible as small piwi expressing cells (arrowheads) beside six to eight larger strongly stained primordial germ cells (that also express nanos, see text) (arrows in A, B, F). Until day seven neoblast number increased, PGCs multiplied and gave rise to testes and ovaries. At day seven testes and developing eggs could be observed (C, H). At days 10 and 12, a chain of developing eggs was present medially and testes were present along the lateral margin (D, E, I, J). Note the accumulation of ipiwi1 in the genital blastema (open arrowhead in E, J) which gives rise to the genital organs. A similar genital blastema was observed during regeneration (see Figure. 4). In all pictures, anterior is to the left. t, testes; de, developing eggs; (asterisk) autofluorescence of digested diatoms in the central syncytium. Scale bars 100 μm.

Manipulation of the acoel stem cell system by hydroxyurea, radiation, and starvation

The inhibition of DNA-synthesis by hydroxyurea (HU) leads to an arrest of proliferating cells in the S-phase of the cell cycle and a pause of cell cycle progression [50] by inhibition of the ribonucleotide reductase [51]. We have applied hydroxyurea treatment for 18 days to halt the cell proliferation of stem cells and germ cells. After three to five days of HU treatment ipiwi1 expression of neoblasts was abolished and the number of somatic S-phase cells was drastically reduced (Figures. 5A-F). After 10 days, ipiwi1 expression persisted only in mature eggs and no ipiwi1 expression could be detected in the region of the testes (Figures. 5G, H). These results indicated that germ cell proliferation was interrupted but differentiation of oogonia was still possible. Moreover, the faster cell turnover in the testes resulted in an earlier reduction of ipiwi1 expressing cells (Figures. 5E, F). After 15 days of HU treatment ipiwi1 expression and cell proliferation of somatic stem cells were completely eradicated (Figures. 5I, J). The decrease in cell proliferation in the ovaries became apparent by the reduction in the production of eggs. Controls produced the following average number of eggs per animal per day: 1.07 at the start of the experiment, 0.99 after three days, 1.009 after five days, 1.45 after 10 days, 1.45 after 15 days (n = 287). In the HU treatment group egg numbers decreased from 1.09 at the start of the experiment to 0.79 after three days, 0.31 after five days, 0.017 after 10 days, and no eggs were laid anymore after 15 days HU treatment. These data demonstrate that we can use HU to manipulate and study stem cell- and germ cell development in I. pulchra.

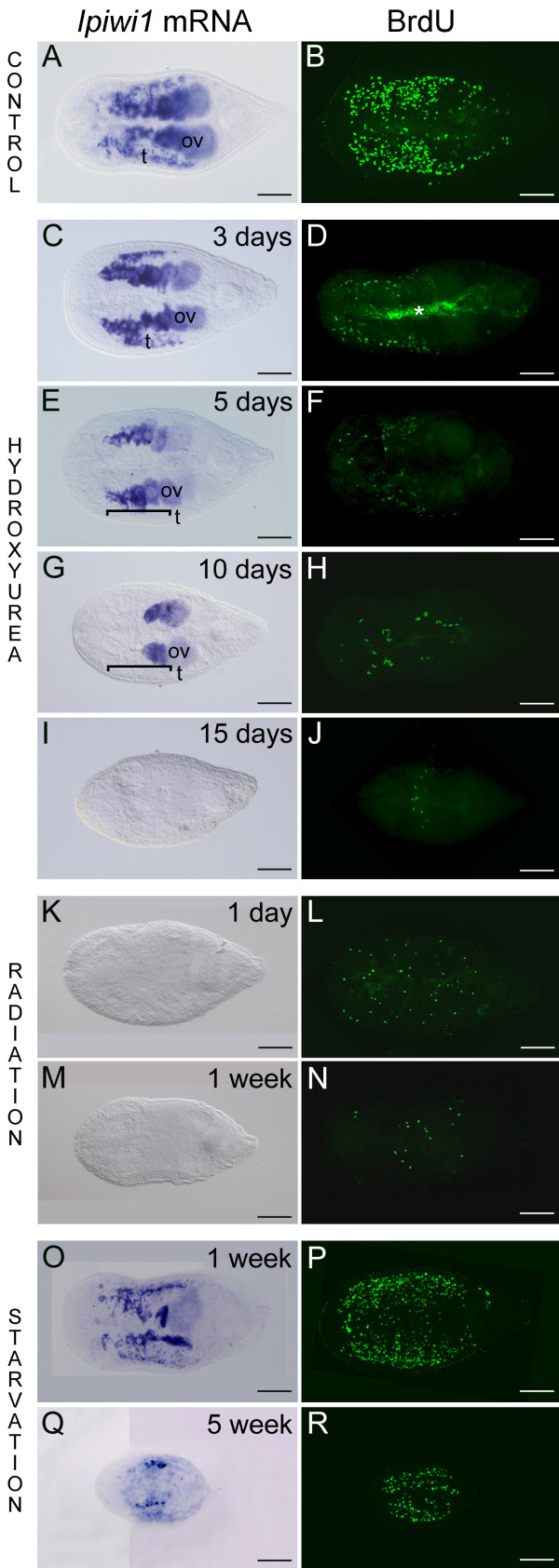

Figure 5.

Ipiwi1 mRNA expression and cell proliferation (BrdU) in controls (A, B), during hydroxyurea treatment (C-J), after irradiation (K-N), and during starvation (O-R). (C) Upon three days HU treatment ipiwi1 mRNA could not be detected in neoblasts but was still present in testes (t) and ovaries (ov). (E) At five days of HU treatment ipiwi1 mRNA was present in all cells of the ovaries (ov) but not in testes (t, bracket indicates region of testes). (G) After 10 days ipiwi1 mRNA remained only in mature eggs; (t, testes; bracket indicates region of testes) (G). After 15 days no ipiwi1 mRNA could be detected (I) The number of S-phase cells strongly decreased during hydroxyurea treatment (D, F, H) and only single S-phase cells were found after 15 days (J). Irradiation (K-N) resulted in a complete elimination of ipiwi1 expression (K, M) and a strong reduction in the number of S-phase cells after one day (L) and one week (N) post irradiation. During starvation (O-R), ipiwi1 expression and protein localization were weakly reduced after one week (O, P). After five weeks of food deprivation, dramatic degrowth led to a strong reduction of Ipiwi1 mRNA and BrdU (Q, R). In all figures, anterior is to the left. t, testes; o, ovaries. Asterisk marks autofluorescence of diatoms within the gut. Scale bars 100 μm.

Radiation is a widely used method in flatworm research to selectively destroy the stem cell system, which in turn stops maintenance of physiological homeostasis, cell renewal and regenerative capability [10,52-54]. In order to study the effect of irradiation on stem cell gene expression in acoels, we performed irradiation experiments with I. pulchra. We found that ipiwi1 expression was completely abolished one and seven days after irradiation, while the expression of the housekeeping gene ipefα (Isodiametra pulchra elongation factor alpha) persisted (Figures. 5K, M and Additional file 4, Figures. S4G-I). Furthermore, neoblast proliferation was drastically reduced one day and one week after irradiation (Figures. 5L, N). These results confirmed that in I. pulchra neoblasts can be eliminated by irradiation. Notably, few cells were still detectable by BrdU incorporation at one day (Figure. 5L) and one week (Figure. 5N) postradiation. It is possible that certain cells conduct intensified DNA repair which could lead to the incorporation of BrdU [55]. Another possibility is that certain stem cells were in a less radiosensitive phase of the cell cycle during radiation and started to divide and to incorporate BrdU. However, our results suggest that neither DNA repair nor the presence of radio resistant stem cells were able to reconstitute the entire stem cell population since irradiation led to death of the animals.

To date, nothing is known of the effect of starvation on the stem cell system of acoels. For this reason, we examined the expression dynamics of ipiwi1 during starvation in I. pulchra (Figures. 5O-R). After prolonged starvation the number of ipiwi1 positive cells was diminished, animals were drastically reduced in size and completely devoid of reproductive organs on morphological level. In I. pulchra, small ipiwi1 positive germ cells remained even after several weeks of starvation (Figures. 5Q, R). After refeeding, animals regrew again to adult stage within one month. These results suggest that degrowth of the animals, the reduction of reproductive organs, and the plasticity of the stem cell system during starvation is a feature how I. pulchra deals with food deprivation.

Ipiwi1 RNA interference in adults, during regeneration and during development

In order to examine the function of piwi-like genes in Isodiametra pulchra, we applied RNA interference in adults, during development and regeneration. We examined the effect of the loss of ipiwi1 mRNA and protein by whole mount in situ hybridization of ipiwi1, the expression of the vasa-like gene ipvasa, by Ipiwi1 protein localization, and by BrdU labelling after 7 and 21 days of ipiwi1 dsRNA application. We confirmed the specificity of ipiwi1 and ipiwi2 dsRNA probes for silencing their respective target (Additional file 6, Figure. S6).

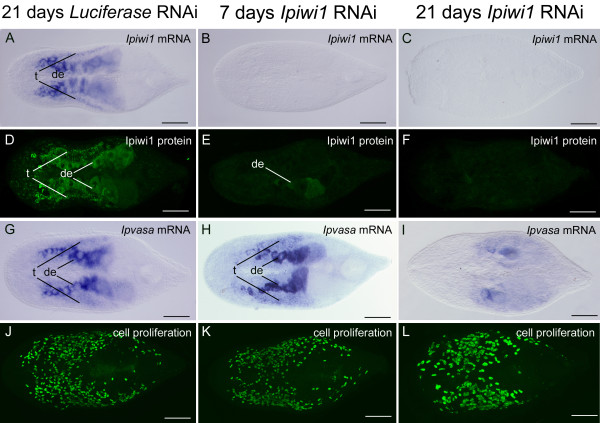

In adults, luciferase dsRNA was applied as control and no noticeable mock effects were observed regarding ipiwi1 expression, BrdU incorporation and animal morphology (Figures. 6A, D, G, J). In contrast, ipiwi1 RNAi treatment led to an elimination of ipiwi1 mRNA and protein after seven and 21 days (Figures. 6B, C, E, F). Ipiwi1 RNAi resulted in a subsequent reduction in ipvasa expression after three weeks of treatment (Figures. 6H, I). Remarkably, ipiwi1 knock-down had at that time no apparent effect on stem cell proliferation and the phenotype of the animals (Figures. 6K, L).

Figure 6.

Influence of Ipiwi1 RNAi on adult I. pulchra at seven and 21 days of ipiwi1 dsRNA treatment. RNAi with luciferase control dsRNA did not show any effect on the level of i piwi1 expression (A), Ipiwi1 protein (D), ipvasa expression (G) or cell proliferation (J). Ipiwi1 mRNA was abrogated after seven days or 21 days of RNAi (B, C). Ipiwi1 protein was strongly reduced after seven days of ipiwi1 RNAi (E) and was completely eliminated after 21 days of ipiwi1 RNAi (F). Ipvasa expression was still prominent after seven days of ipiwi1 RNAi (H) and became significantly reduced after 21 days of ipiwi1 dsRNA treatment (I). Cell proliferation remained high up to 21 days of ipiwi1 dsRNA treatment (K, L). The specimen in figure 7L was processed for in situ hybridization before immunocytochemistry and therefore the nuclei appear larger. This protocol however did not alter cell number. In all figures, anterior is to the left. (t) testes; (de), developing eggs. Scale bars 100 μm.

A comparable role of ipiwi1 was observed during regeneration (Additional file 7, Figure. S7). Animals were cut twice - at one and two weeks of ipiwi1 RNAi treatment respectively - and were analyzed after 21 days, i.e. seven days after the final amputation. Ipiwi1 dsRNA treated regenerates lacked Ipiwi1 mRNA and protein (Additional file 7, Figures. S7B, D), had reduced ipvasa expression (Additional file 7, Figures. S7E, F), but preserved normal cell proliferation (Additional file 7, Figures. S7K, L), and were able to rebuild the missing body parts. However, these animals were unable to produce viable offspring. Taken together, these results suggest that Ipiwi1 is not involved - fulfils a redundant function - in the regulation of stem cell maintenance in adult and regenerating animals, but is crucial for offspring development.

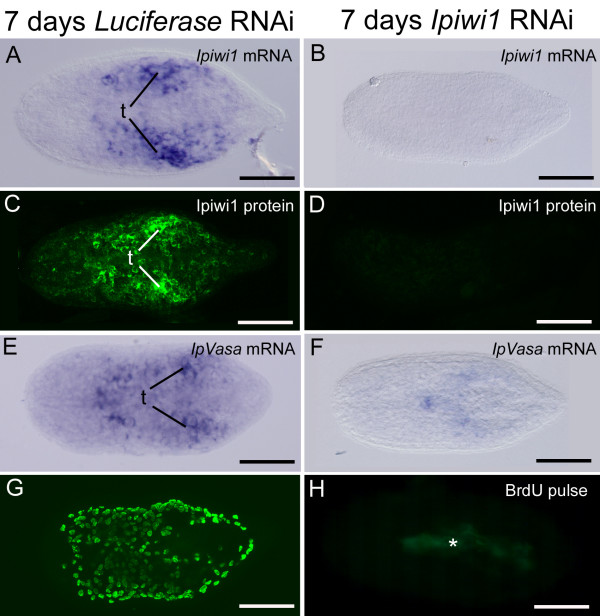

Finally, we wanted to address whether ipiwi1 had an essential function during development of I. pulchra. Therefore we eliminated ipiwi1 already in developing eggs of adult worms to abolish maternal ipiwi1 mRNA. As such, the term development used here includes all stages from a maturating egg within an adult, to embryonic and postembryonic stages. Eggs from adult worms, which were treated with ipiwi1 dsRNA for two weeks died without hatching. Embryos collected from one week ipiwi1 dsRNA treated adults hatched, but had abrogated ipiwi1 mRNA (Figure. 7B) and Ipiwi1 protein (Figure. 7D). They also did not retain ipvasa expression (Figure. 7F), completely lacked proliferating cells (Figure. 7H), and juveniles died within the first week of postembryonic development. These data suggest that ipiwi1 has an essential function during development.

Figure 7.

Effect of ipiwi1 RNAi on development of I. pulchra after seven days of ipiwi1 dsRNA treatment. As a control, RNAi with luciferase dsRNA was performed which did not lead to any change in ipiwi1 or ipvasa mRNA expression (A, E), Ipiwi1 protein (C) or cell proliferation (G). After seven days of ipiwi1 RNAi treatment, ipiwi1 and ipvasa mRNA and protein were drastically reduced (B, D, F) and cell proliferation had completely stopped (H). All ipiwi1 knock-down juveniles died before eight days of postembryonic development. In all figures, anterior is to the left. Autofluorescence of diatoms is marked with an asterisk. (t) testes. Scale bars 100 μm.

Discussion

Acoels possess a potent stem cell system that is responsible for development, homeostasis, growth and regeneration

In recent years it has been shown that flatworms can serve as suitable model systems for understanding basis mechanisms of stem cell biology, regeneration, and aging [2,56-59]. Here we characterized the stem cell system of the acoel Isodiametra pulchra and clearly illustrated that I. pulchra possesses neoblast-like proliferating cells, earlier also described for the acoels Convolutriloba longifissura and Convoluta naikaiensis [29,30]. Epidermal cells as well as all other cell types from the three germ layers were exclusively renewed from these mesodermally located stem cells. A similar mode of tissue homeostasis and epidermal replacement is known from rhabditophoran Platyhelminthes such as macrostomids [2,60-63], triclads [5,6,52,64-67] and neodermata [68-73]. Within the Bilateria, a stem cell population crucial for development, tissue homeostasis and regeneration is hitherto only known from Acoela and Rhabditophora. In the cnidarian Hydra, I-cells serve as stem cells for most tissues, whereas two epithelial cell lineages guarantee for epithelial tissue homeostasis [74]. Likewise, in other taxa with high regeneration capacity such as sponges [45], several stem cell populations ensure tissue specific homeostasis.

In basal metazoan taxa with high regeneration and transdifferentiation capacity such as sponges and cnidarians, piwi-like genes play a role in the regulation of gonadal and somatic stem cells [43,45]. Notably, studies on the expression of piwi-like genes of key positioned taxa such as catenulids, nemertodermatids, gnathostomulids, gastrotrichs are lacking. Here we showed that in the adult I. pulchra ipiwi1 is expressed in a subpopulation of somatic stem cells and in germ cells. Regarding the crucial phylogenetic position of acoels, our data give evidence that piwi expression extended to somatic stem cells might have persisted from basal Bilateria to higher organisms including ascidians and human blood cells [75,76].

Since I. pulchra is not able to regenerate a new head, we focussed in the current study on posterior regeneration. During the first days, ipiwi1 expression was locally upregulated underneath the wound epithelia. As regeneration proceeded, differentiation of the tissue was paralleled by decrease of piwi expression. Notably there was an apparent similarity between piwi expression dynamics during formation of the genital organs during development and regeneration. Such a local piwi upregulation was also found during regeneration in triclads [34], as well as during regeneration and development in Macrostomum lignano [77].

During the development of animals with sexual reproduction, a biological decision has to be made to separate soma (body cells) from the germline (gametes). However, in some phyla, such as sponges, cnidarians, acoels and rhabditophoran flatworms, the border between those two lineages is not clearly made and germ cells can be formed de novo from somatic stem cells (reviewed in [78]). Here we show that in the acoel I. pulchra, germ cell precursors are already present in freshly hatched worms, suggesting an embryonic formation of the germline. Although in flatworms it was initially supposed that the germline is formed postembryonically [79,80], several publications recently showed the presence of germ cells in late embryos or freshly hatched worms [3,77,81]. However, despite the fact that germ cells might be already present in late embryos of I. pulchra and some rhabditophoran flatworms they maintain somatic neoblasts during adulthood which retain the capacity to differentiate into germ cells [82,83].

Ipiwi1 expression dynamics following stem cell depletion by HU treatment, irradiation and starvation

In I. pulchra, prolonged HU treatment resulted in a drastic decline in stem cell proliferation and ipiwi1 expression. The faster elimination of ipiwi1 expression and BrdU in somatic stem cells and testes, compared to ovaries could be explained by the faster cell turnover in these tissues [84]. Notably, after 10 days of HU treatment, few cells were still able to incorporate BrdU. These cells might be gonadal cells or slow cycling neoblasts, activated upon stem cell depletion [60]. In triclad flatworms hydroxyurea was applied to detect fast and slow cycling neoblasts [85]. In the parasitic platyhelminth Schistosoma mansoni it was found that both sexes were sensitive to hydroxyurea treatment [86]. Interestingly, it was shown that hydroxyurea had no effect on metamorphosis of miracidia [87]. In the cnidarian Hydra HU was used to reduce the number of interstitial cells [88] and to follow nerve cell and nematocyte differentiation [89]. To conclude, our data demonstrate that we can use HU to manipulate and study stem cell- and germ cell development in I. pulchra.

Since neoblasts are the only proliferating cells in rhabditophoran flatworms, radiation is a commonly used method to confirm stem cell specific gene expression [4,53,84,90-92]. In this study, we showed that a similar situation was observed after depleting the stem cell population of acoels by radiation. Radiation drastically reduced the expression of ipiwi1, confirming his stem cell specific expression. One week post radiation, few cells were still able to incorporate BrdU. Further experiments will reveal if these cells are activated slow cycling neoblasts or gonadal stem cells which were shown to possess higher radio tolerance in rhabditophoran flatworms [84].

Food deprivation resulted in degrowth of I. pulchra. During prolonged starvation, animals successively decreased in body size, possessed reduced gonads, and showed a diminished proliferation activity. After refeeding however, animals regrew again to adult size. Comparably, some annelids [93], nemerteans [94] and rhabditophoran flatworms [6] are able to starve for months and undergo degrowth during that period. The terrestrial triclad Arthurdendyus triangulatus undergoes natural periods of growth and degrowth correlated with the availability of its prey - the earthworm [95-97]. Upon starvation, adult animals resorb their tissues and deplete body reserves [98] and cannot be distinguished from juvenile animals [99]. The striking cellular responses of freshwater triclads to degrowth include the reduction of cell proliferation, a decrease in cell numbers, and autophagy [100-103]. Similar observations of growth and degrowth were found in the macrostomid flatworm M. lignano [84,104]. We conclude that degrowth, and the reduction of reproductive organs are features how I. pulchra deals with food deprivation.

Ipiwi1 function is essential for acoel development

In order to analyse the function of piwi-like genes in acoels, we established a non-invasive RNAi protocol by soaking. Ipiwi1 RNA interference during development resulted in a lethal phenotype, demonstrating the crucial role of ipiwi1 during development. Although ipiwi1 is expressed in a subpopulation of somatic stem cells and in germ cells no visible phenotype could be observed after prolonged RNAi treatment regarding homeostasis and regeneration. The absence of a clear phenotype could be explained by the fact that other piwi-like genes might compensate for Ipiwi1 function. At the moment, we cannot exclude this possibility since the genome of I. pulchra is not yet available and screening with several different degenerated primers did not result in the isolation of additional piwi-like genes. We can exclude a redundancy with ipiwi2 since ipiwi1/ipiwi2 double RNAi did not lead to a more severe phenotype (data not shown).

Although redundant piwi-like genes might exist in I. pulchra, it is intriguing that redundancy would act during homeostasis and regeneration, but not during development. These observations indicate that stem cells might be differentially regulated and expression of different piwi-like genes might vary during development and homeostasis [77]. Further characterization of all piwi-like genes might clarify if we deal with different stem cell populations or if stem cells are differentially regulated.

Conclusions

In this study, we presented the acoel Isodiametra pulchra as suitable model organism to address developmental questions in this understudied phylum. We established stable laboratory cultures of I. pulchra with unlimited availability of offspring the whole year through, and developed a whole mount ISH protocol and a simplified RNAi method by soaking.

Summarizing all data we can conclude that (1) acoel neoblasts are the only proliferating cells in Isodiametra pulchra, (2) acoel stem cells show a characteristic morphology on the light and electron microscopical level, (3) neoblasts are exclusively located parenchymally with a lack of proliferating cells in the epidermis, (4) cell renewal for tissue homeostasis, during growth and regeneration is based exclusively on parenchymal stem cells, (5) piwi expression in I. pulchra is, in addition to the germline, present in a subpopulation of somatic neoblasts, (6) I. pulchra exhibits a high plasticity upon starvation accompanied by substantial degrowth and the reduction of reproductive organs. Refeeding leads to a full restoration of size and reproduction, (7) irradiation leads to the elimination of neoblasts and finally to the death of the animals, (8) functional knock-down of Ipiwi1 reveals an essential role of Ipiwi1 during development.

Methods

Animal culture

Isodiametra pulchra (Acoela, Acoelomorpha) was kept in petri dishes with nutrient-enriched f/2 artificial sea water [105] and fed ad libitum with diatoms (Nitzschia curvilineata). Climate chamber conditions were 20°C and 60% humidity with 14/10 hours day/night cycle.

Cloning of piwi-like genes and sequence analysis

Partial Sequences of Ipiwi1 and Ipiwi2 were obtained from an EST project (Ladurner and Agata, unpublished). Concatenation of five EST's resulted in the full length ORF of Ipiwi1 (accession number Ipiwi1 [EMBL:AM942741]); while another clone represented a partial sequence of Ipiwi2. Full length sequence of Ipiwi2 was obtained by 5'RACE-PCR using a SMART RACE cDNA amplification kit (BD Bioscience) with the sequence specific primers 5'-GAATTGGCTCATGCGGGTCAGTC-3' and 5'-GGAAGTCCTCCCGCATCTTGTCC-3'. The revealed PCR product was cloned using a pGEM-T vector system I (Promega) and sequenced by MWG (Germany). Nested primers were made in the newly obtained sequence: 5'-CTCGAACTTCAGCAACCGCATGA-3', 5'-GTTCTGGCATGGAAGG-GGATTGG-3' and 5'-GGGAGGGCTGAAATCGACATGGTA-3' and used for nested PCR with the I. pulchra cDNA phage library as template. The obtained PCR product was cloned into a pCR II-TOPO vector (Invitrogen) and sequenced by GATC (Konstanz, Germany). The accession number of Ipiwi2 is [EMBL:AM942742].

Whole mount in situ hybridization

Whole mount in situ hybridization was carried out as described previously for M. lignano (Pfister et al. 2007), except for the proteinase K treatment (7 min for I. pulchra). Riboprobes were generated using the DIG RNA labelling KIT SP6/T7 (Roche), following the manufacturers protocol.

Template DNA for producing DIG-labelled probe was made by standard PCR (primer couple for Ipiwi1: 5'-CATGCTGGAGATGGGCAAGATCAC-3' and 5'-GGTGCCGGAGATTTCATTGCTCTC-3; for Ipiwi2: 5'-GCATGAGCCAATTCATC-AGTCGAG-3' and 5'-GGCAGCTCACCGTCATTCATCTCT-3'; for IpVasa: 5'-ACCCACGAAGGCATCAACTTC-3' and 5'-TCGCATCTCTTCTTCATCTCG-3' [EMBL_FN298396]); for IpEfα 5'-GTCAGTATTGTCGTCATTGGCC-3' and 5-'GCTCCATTCTTTAAACCAGGGC-3' ([EMBL_FN298397]) which produced ISH probes for Ipiwi1 (826 bp), Ipiwi2 (865 bp), Ipvasa (882 bp) and IpEfα (624 bp). During hybridization riboprobes were used at working concentrations of 0,05 for Ipiwi1 and Ipvasa and 0,1 ng/μl for Ipiwi2 and IpEfα, respectively. Pictures were made using a Leica DM5000 microscope and a Pixera Penguin 600CL digital camera.

Immunohistochemistry

Antibody stainings were performed as previously described (Ladurner et al., 2005) with the following modifications: animals were fixed for only 30 min with 4% PFA at room temperature (RT). Multiple PBS-T (0,1%) washes (3 × 5 min, 1 h at RT) were followed by 30 min blocking in PBS-BSA-T (1%) (RT). Primary antibody was incubated overnight in PBS-BSA-T (4°C) (1/1000 for Ipiwi1). After washing with PBS-T (0,1%) (3 × 5 min), specimen were incubated in secondary antibody (1/200 FITC-swine-anti-rabbit, 1 h RT, DAKO) and washed again 3 × 5 min in PBS-T. Specimen were mounted with Vectashield (VECTAR) and analyzed with a Leica DM5000. Confocal images were made with a Zeiss LSM 510.

To localize Ipiwi1 proteins, we have generated a specific polyclonal antibody (Additional file 4, Figures. S4). Primary polyclonal Ipiwi1 antibody was produced by GenScript (GenScript Corp, NJ, USA). The following peptide was used for immunisation: DREERPRFINDENV(C) (aa 98-111).

Electron microscopy and immunogold labelling were performed according to Bode et al.[60]

Double labelling of S-phase cells (BrdU) and Ipiwi1 expressing cells (in situ hybridization) Preceding fixation, animals were pulsed for 30 min with 5 mM BrdU to label neoblasts in S-phase [61]. In situ hybridization was performed as described above, except for color development, which was carried out with Fast Red, in order to obtain fluorescent staining (Sigma, F4648). After in situ hybridization, animals were rinsed in ddH2O and further processed through the BrdU staining protocol [61] except for protease XIV treatment, which was done at a final concentration of 0,1 mg/ml for 20 minutes at 37°C.

Single cell maceration

In order to prevent algae contamination, animals were starved for 2 days. For each maceration, 3 adult animals were BrdU pulsed for 30 min (5 mM in F/2), washed twice with culture medium and directly further processed (BrdU pulse) or left for 10 days under standard culture conditions in the dark (BrdU pulse-chase). Specimens were gradually relaxed for 5 min in 7,14% MgCl2 and dissociated in CMF/1% trypsin solution for 1 hour at 37°C. During maceration, animals/cells were carefully mixed every 15 minutes. Cells were pelleted, supernatant was removed, and cells were resuspended in 200 μl PFA (4% in PBS) and fixed for 40 min at room temperature. Cells were transferred on coated slides (DAKO, S2024), and dried for 10 minutes. 6 × 5 min PBS-T (0,1%) washing steps were performed, followed by 45 min incubation in 2 N HCl (37°C). After 3 × 5 min PBS-T washes, unspecific staining was blocked during 30 min, in PBS-BSA (1%)-Triton (0,1%). Primary antibody was used in a final concentration of 1/800 in PBS-BSA-T (mouse anti BrdU, Roche) and incubated overnight at 4°C. The next day, cells were washed 3 × 5 min in PBS-T and incubated for 1 hour in secondary antibody (goat anti mouse FITC; 1/200, DAKO). Excessive antibody was removed by 5 × 5 min incubation in PBS-T and cells were mounted in Vectashield. Pictures were taken using a Leica DM5000 microscope.

Western blot

Animals were starved for 1 day. Total protein of 650 animals was extracted in 100 μl 2× Slab/100 μl PBS and loaded onto 12% acrylamide gels (90 min, 150 V). Protein was blotted on polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (90 min, 25 V) (Immobilon-P; Millipore) and blocked for 2 h with PBS (pH 7,4) containing 0.3% Tween 20, 1% skimmed milk powder. Blots were incubated overnight at 4°C in primary antibody with a final concentration of 1 μg/ml for Ipiwi1. After washing the blots for 3 × 10 min in PBS-Tween (0,3%), membranes were incubated with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-mouse immunoglobulin (1/10,000 Sigma, 2 h, RT). Finally, after several washing steps (8 × 10 min), immunocomplexes were detected using nitro blue tetrazolium: 5-bromo-4- chloro-3 indolyl phosphate (LifeTechnology).

Post embryonic development, regeneration, and starvation

About 1000 staged eggs were collected of I. pulchra. During the whole postembryonic development (19 days), 50 juveniles were fixed each day and stored in methanol until further processed for ISH and immunohistochemistry.

To obtain regenerating animals, 500 I. pulchra were cut at the tail region. Every day, 40 animals were fixed and stored in methanol (-20°C) until further processed for ISH and immunohistochemistry respectively.

During starvation, worms were kept in petri dishes filled with culture media (f/2) without food. Medium was changed twice a week. Every week, a batch of 50 animals was fixed and stored in MeOH until further processing.

Hard X-ray irradiation

Intact worms were exposed to 60 Gray, using a linear Accelerator (8 MeV, 400 cGy/min; Radio-Oncology, Medical Hospital, Innsbruck). Animals were fixed one hour, one day, one week, two weeks and three weeks postirradiation and examined for piwi expression and BrdU incorporation.

Hydroxyurea treatment

A batch of 400 adults (30 - 40 days old) was treated with 2,8 mM hydroxyurea, a specific inhibitor of DNA synthesis (HU, Sigma H-8627) [106]. During the whole treatment (18 days), animals were kept continuously in the dark and HU medium was changed daily. Every second day, a batch of worms was pulsed for 30 min with BrdU (5 mM in F/2), relaxed and fixed for in situ hybridisation, as described earlier.

RNA interference

An RNA interference protocol by soaking was newly developed for I. pulchra using a dsRNA probe generated by an in vitro transcription system (T7 RibomaxTM Express RNAi System, Promega). The dsRNA probe used for RNAi overlaps completely with the ISH probes for ipiwi1 (bp 1304 - bp 2131) (Additional file 1, Figure. S1) and ipiwi2 (865 bp) (Additional file 1, Figure. S2). As a negative control for RNA interference, a 1002 bp Luciferase fragment was used (pGEM-luc Vector (Promega). dsRNA was diluted in f/2 culture medium to a final concentration of 3 ng/μl and supernatant was changed every 12 hours. Throughout the whole experiment, animals were fed ad libitum in 24 well plates (25 animals per well). Specimens were examined for BrdU incorporation, piwi mRNA and protein expression as well as the influence of piwi RNAi on vasa expression after 7 days and 21 days treatment. Survival, reproducibility and regeneration capacity were followed during the whole experiment (d = 21).

Competing interests

The authors declare to have no competing financial or other interest in relation to their work.

Authors' contributions

KDM contributed to conception and design of the project, contributed to acquisition of all data, analysed and interpreted the data and was involved in drafting the manuscript. DP, AKG, and MH significantly contributed to ISH establishment and GK initially participated in piwi isolation. MW and BE contributed in regeneration experiments. WS and MT participated in transmission electron microscopy and sectioning. GB contributed in piwi results and manuscript drafting. PL has designed the study, was involved in the radiation experiments, interpreted results, and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1: Nucleotide sequence and predicted protein product of Ipiwi1. Conserved PAZ and PIWI domains highlighted in blue (PAZ) and green (PIWI). The piwi box within the piwi domain is marked in red. Start and stop codon are underlined and marked in bold. ISH primers are underlined within the sequence. Accession number for Ipiwi1 (AM942741).

Figure S2: Nucleotide sequence and predicted protein product of Ipiwi2. Conserved PAZ and PIWI domains are highlighted in blue (PAZ) and green (PIWI). The piwi box within the piwi domain is marked in red. Start and stop codon are underlined and marked in bold. ISH primers are underlined within the sequence. Accession number for Ipiwi2 (AM942742).

Figure S3:. Alignment of predicted piwi-like genes from I. pulchra with piwi-like genes from other species. (A) Amino acid alignment of the conserved PAZ domain. (B) Amino acid alignment of the conserved PIWI domain. The PIWI box is highlighted in purple. Amino acids indicated with green asterisks are supposed to create a binding pocket for the 5'phosphate group of binding RNA. Red asterisks indicate putative RNase active site carboxylate residues. Amino acids indicated in purple can distinguish members of the piwi and argonaute subfamily. The Genbank accession numbers: Isodiametra pulchra Ipiwi1 (AM942741); Isodiametra pulchra Ipiwi2 (AM942742); Macrostomum lignano Macpiwi (AM942740); Schmidtea mediterranea Smedwi1 (DQ186985) Smedwi2 (DQ186986); Dugesia japonica DjPiwi1 (AJ865376); Podocoryne carnea Cniwi (AAS01181); Caenorhabditis elegans PRG1 (NP492121); Drosophila melanogaster DmPiwi (AF104354); Strongylocentrotus purpuratus Seawi (AY014899); Homo sapiens Hiwi (AF104260).

Figure S4: Ipiwi2 expression, Ipiwi1 and Ipiwi2 control sense probes, Ipiwi1 Western Blot and radiation controls. Ipiwi2 whole mount in situ hybridization (A) with detail of expression in testes (t) (B) and in developing eggs (de) (C). (D) Ipiwi1 sense control. (E) Ipiwi2 sense control. (F) Western blot of Ipiwi1 polyclonal antibody, showing a signal at the expected size (100 kDa). (G-I) Hard X ray radiation of 60 Gray did not result in a significant downregulation of the housekeeping gene Isodiametra pulchra elongation factor alpha (IpEfα). IpEfα Control (G); IpEfα expression after one day (H) and one week (I) postirradiation. Scale bars 100 μm in (A, D, E, G, H, I), 50 μm in (B) and 25 μm in (C).

Figure S5: . Overview of Ipiwi1 expression and dynamics during posterior regeneration in Isodiametra pulchra. This whole mount overview clearly demonstrates that Ipiwi1 is only locally upregulated within the regeneration blastema (for details see Figure. 4). Expression of Ipiwi1 mRNA (A-I) and protein localization (J-R). One hour after cutting (A; J) and up to five hours postamputation (B, K) Ipiwi1 could not be detected at the regeneration site by in situ hybridization. Ipiwi1 was upregulated in the regeneration blastema (arrow) after 10 hours (C, L) and 25 hours postamputation (D, M). From 42 hours onwards Ipiwi1 remained downregulated in the regeneration blastema (E-R) and Ipiwi1 expression and protein were only present in the differentiating genital blastema (open arrows in E-Q). Scale bars 100 μm.

Figure S6: Specificity of the dsRNA silencing of Ipiwi1 and Ipiwi2. RNA interference of Ipiwi1 resulted in the elimination of Ipiwi1 mRNA within 7 days (A) but ipiwi2 remained present (C). Likewise, RNA interference using Ipiwi2 dsRNA resulted in the elimination of ipiwi2 transcripts (D) but ipiwi1 was not affected (B). Scale bars 100 μm.

Figure S7:. Effect of Ipiwi1 RNAi on the regeneration of I. pulchra after 21 days of Ipiwi1 dsRNA treatment. RNAi with luciferase dsRNA did not show any effect on Ipiwi1 or Ipvasa mRNA expression (A, E), Ipiwi1 protein (C) or cell proliferation (G). After 21 days of Ipiwi1 dsRNA treatment ipiwi1 expression was eliminated both on mRNA (B) as well as on protein level and only weak ipvasa mRNA could be detected in remnant eggs (F). Notably, cell proliferation was not affected up to 21 days of ipiwi1 dsRNA treatment (H). (de) developing eggs; (t) testes. Scale bars 100 μm.

Contributor Information

Katrien De Mulder, Email: K.mulder@Hubrecht.eu.

Georg Kuales, Email: Georg.Kuales@uibk.ac.at.

Daniela Pfister, Email: Daniela.Pfister@uibk.ac.at.

Maxime Willems, Email: Maxime.Willems@UGent.be.

Bernhard Egger, Email: Bernhard.Egger@uibk.ac.at.

Willi Salvenmoser, Email: Willi.Salvenmoser@uibk.ac.at.

Marlene Thaler, Email: m.thaler@smt.zeiss.com.

Anne-Kathrin Gorny, Email: Anne.Gorny@uibk.ac.at.

Martina Hrouda, Email: Martina.Hrouda@ky8.ecs.kyoto-u.ac.jp.

Gaëtan Borgonie, Email: Gaetan.Borgonie@UGent.be.

Peter Ladurner, Email: peter.ladurner@uibk.ac.at.

Acknowledgements

The authors want to thank S Tyler and M Hooge (University of Maine) for original I. pulchra culture, RM Rieger and B Hobmayer (University of Innsbruck) for helpful discussions and Prof K Agata (Kyoto University, Japan) for the I. pulchra EST-library collaboration. Finally, we want to thank I Philipp and F Marx for help in the lab and Paul Eichberger for radiation experiments. This work was supported by a predoctoral FWO grant to KDM (Belgium), an IWT doctoral grant to MW, the EU Marie Curie Research Training Network Zoonet (BE), and a FWF grant 18099 to PL (Austria).

References

- Agata K, Umesono Y. Brain regeneration from pluripotent stem cells in planarian. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2008;363:2071–2078. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.2260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladurner P, Egger B, De Mulder K, Pfister D, Kuales G, Salvenmoser W. In: stem cells: from hydra to man. 1. Bosch TC, editor. Vol. 1. Springer; 2008. The stem cell system of the basal flatworm Macrostomum lignano; pp. 75–94. [Google Scholar]

- Pfister D, De Mulder K, Hartenstein V, Kuales G, Borgonie G, Marx F. Flatworm stem cells and the germ line: developmental and evolutionary implications of macvasa expression in Macrostomum lignano. Dev Biol. 2008;319:146–159. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.02.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhoffer GT, Kang H, Sanchez AA. Molecular analysis of stem cells and their descendants during cell turnover and regeneration in the planarian Schmidtea mediterranea. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:327–339. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handberg-Thorsager M, Fernandez E, Salo E. Stem cells and regeneration in planarians. Front Biosci. 2008;13:6374–6394. doi: 10.2741/3160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellettieri J, Sanchez AA. Cell turnover and adult tissue homeostasis: from humans to planarians. Annu Rev Genet. 2007;41:83–105. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.41.110306.130244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salo E, Baguna J. Regeneration in planarians and other worms: New findings, new tools, and new perspectives. J Exp Zool. 2002;292:528–539. doi: 10.1002/jez.90001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez AA. Stem cells and the Planarian Schmidtea mediterranea. C R Biol. 2007;330:498–503. doi: 10.1016/j.crvi.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baguna J, Salo E, Auladell C. Regeneration and pattern-formation in planarians .3. Evidence that neoblasts are totipotent stem-cells and the source of blastema cells. Development. 1989;107:77–86. [Google Scholar]

- Brondsted HV. Planarian regeneration. Oxford: Pergamon Press; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Sempere L, Martinez P, Cole C, Baguna J, Peterson K. Phylogenetic distribution of microRNAs supports the basal position of acoel flatworms and the polyphyly of Platyhelminthes. Evol Dev. 2007;9:409–415. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-142X.2007.00180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Trillo I, Riutort M, Fourcade HM, Baguna J, Boore JL. Mitochondrial genome data support the basal position of Acoelomorpha and the polyphyly of the Platyhelminthes. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2004;33:321–332. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2004.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telford MJ, Lockyer AE, Cartwright-Finch C, Littlewood DT. Combined large and small subunit ribosomal RNA phylogenies support a basal position of the acoelomorph flatworms. Proc Biol Sci. 2003;270:1077–1083. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2003.2342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Trillo I, Paps J, Loukota M, Ribera C, Jondelius U, Baguna J. A phylogenetic analysis of myosin heavy chain type II sequences corroborates that Acoela and Nemertodermatida are basal bilaterians. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:11246–11251. doi: 10.1073/pnas.172390199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson KJ, Eernisse DJ. Animal phylogeny and the ancestry of bilaterians: inferences from morphology and 18S rDNA gene sequences. Evol Dev. 2001;3:170–205. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-142x.2001.003003170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Trillo I, Riutort M, Littlewood DT, Herniou EA, Baguna J. Acoel flatworms: earliest extant bilaterian Metazoans, not members of Platyhelminthes. Science. 1999;283:1919–1923. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5409.1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philippe H, Brinkmann H, Martinez P, Riutort M, Baguna J. Acoel flatworms are not Platyhelminthes: Evidence from phylogenomics. Plos One. 2007. p. e717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Dunn CW, Hejnol A, Matus DQ, Pang K, Browne WE, Smith SA. Broad phylogenomic sampling improves resolution of the animal tree of life. Nature. 2008;452:745–749. doi: 10.1038/nature06614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger B, Steinke D, Tarui H, De Mulder K, Arendt D, Borgonie G. To be or not to be a flatworm: the acoel controversy. Plos One. 2009;4(5):e5502. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallberg A, Curini-Galletti M, Ahmadzadeh A, Jondelius U. Dismissal of Acoelomorpha: Acoela and Nemertodermatida are separate early bilaterian clades. Zoologica scripta. 2007;36:509–523. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-6409.2007.00295.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JPS, Tyler S, Rieger RM. Is the Turbellaria polyphyletic. Hydrobiologia. 1986;132:13–21. doi: 10.1007/BF00046223. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers U. Das phylogenetisch System der Platyhelminthes. Stuttgart: Gustav Fisher; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Steinböck O. Regenerations- und Konplantationsversuche an Amphiscolops spec. (Turbellaria acoela) Roux's Arch Dev Biol. 1963;154:308–353. doi: 10.1007/BF00582080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinböck O. Regenerationsversuche mit Hofstenia giselae Steinb. (Turbellaria acoela) Roux's Arch Dev Biol. 1967;158:394–458. doi: 10.1007/BF01380539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikes JM, Bely AE. Radical modification of the A-P axis and the evolution of asexual reproduction in Convolutriloba acoels. Evol Dev. 2008;10:619–631. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-142X.2008.00276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Åkesson B, Gschwentner R, Hendelberg J, Ladurner P, Müller J, Rieger R. Fission in Convolutriloba longifissura : asexual reproduction in acoelous turbellarians revisited. Acta Zoologica. 2001;82:231–239. doi: 10.1046/j.1463-6395.2001.00084.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ladurner P, Rieger R. Embryonic muscle development of Convoluta pulchra (Turbellaria-Acoelomorpha, Platyhelminthes) Dev Biol. 2000;222:359–375. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry JQ, Martindale MQ, Boyer BC. The unique developmental program of the acoel flatworm, Neochildia fusca. Dev Biol. 2000;220:285–295. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hori I, Hikosaka-Katayama T, Kishida Y. Cytological approach to morphogenesis in the planarian blastema. III. Ultrastructure and regeneration of the acoel turbellarian Convoluta naikaiensis. Submicrosc Cytol Pathol. 1999;31:247–258. [Google Scholar]

- Gschwentner R, Ladurner P, Nimeth K, Rieger R. Stem cells in a basal bilaterian. S-phase and mitotic cells in Convolutriloba longifissura (Acoela, Platyhelminthes) Cell Tissue Res. 2001;304:401–408. doi: 10.1007/s004410100375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvetti A, Rossi L, Deri P, Batistoni R. An MCM2-related gene is expressed in proliferating cells of intact and regenerating planarians. Dev Dyn. 2000;218:603–614. doi: 10.1002/1097-0177(2000)9999:9999<::AID-DVDY1016>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata N, Umesono Y, Orii H, Sakurai T, Watanabe K, Agata K. Expression of vasa(vas)-related genes in germline cells and totipotent somatic stem cells of planarians. Dev Biol. 1999;206:73–87. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.9130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddien PW, Oviedo NJ, Jennings JR, Jenkin JC, Sanchez AA. SMEDWI-2 is a PIWI-like protein that regulates planarian stem cells. Science. 2005;310:1327–1330. doi: 10.1126/science.1116110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo T, Peters AH, Newmark PA. A Bruno-like gene is required for stem cell maintenance in planarians. Dev Cell. 2006;11:159–169. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solana J, Lasko P, Romero R. Spoltud-1 is a chromatoid body component required for planarian long-term stem cell self-renewal. Dev Biol. 2009;328:410–421. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.01.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi L, Salvetti A, Lena A, Batistoni R, Deri P, Pugliesi C. DjPiwi-1, a member of the PAZ-Piwi gene family, defines a subpopulation of planarian stem cells. Dev Genes Evol. 2006;216:335–346. doi: 10.1007/s00427-006-0060-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palakodeti D, Smielewska M, Lu YC, Yeo GW, Graveley BR. The PIWI proteins SMEDWI-2 and SMEDWI-3 are required for stem cell function and piRNA expression in planarians. RNA. 2008;14:1174–1186. doi: 10.1261/rna.1085008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houwing S, Berezikov E, Ketting RF. Zili is required for germ cell differentiation and meiosis in zebrafish. EMBO J. 2008;27:2702–2711. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das PP, Bagijn MP, Goldstein LD, Woolford JR, Lehrbach NJ, Sapetschnig A. Piwi and piRNAs act upstream of an endogenous siRNA pathway to suppress Tc3 transposon mobility in the Caenorhabditis elegans germline. Mol Cell. 2008;31:79–90. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung WJ, Okamura K, Martin R, Lai EC. Endogenous RNA interference provides a somatic defense against Drosophila transposons. Curr Biol. 2008;18:795–802. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Donnell KA, Boeke JD. Mighty Piwis defend the germline against genome intruders. Cell. 2007;129:37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klattenhoff C, Theurkauf W. Biogenesis and germline functions of piRNAs. Development. 2008;135:3–9. doi: 10.1242/dev.006486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seipel K, Yanze N, Schmid V. The germ line and somatic stem cell gene cniwi in the jellyfish Podocoryne carnea. Int J Dev Biol. 2004;48:1–7. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.15005568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denker E, Manuel M, Leclere L, Le GH, Rabet N. Ordered progression of nematogenesis from stem cells through differentiation stages in the tentacle bulb of Clytia hemisphaerica (Hydrozoa, Cnidaria) Dev Biol. 2008;315:99–113. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funayama N. In: Stem cells, from Hydra to man. Bosch TC, editor. Springer; 2008. Stem cell system of sponge; pp. 17–35. [Google Scholar]

- Carmell MA, Xuan Z, Zhang MQ, Hannon GJ. The Argonaute family: tentacles that reach into RNAi, developmental control, stem cell maintenance, and tumorigenesis. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2733–2742. doi: 10.1101/gad.1026102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerutti L, Mian N, Bateman A. Domains in gene silencing and cell differentiation proteins: the novel PAZ domain and redefinition of the Piwi domain. Trends Biochem Sci. 2000;25:481–482. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(00)01641-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger B, Gschwentner R, Rieger R. Free-living flatworms under the knife: past and present. Dev Genes Evol. 2007;217:89–104. doi: 10.1007/s00427-006-0120-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaerber C, Salvenmoser W, Rieger R, Gschwentner R. The nervous system of Convolutriloba (Acoela) and its patterning during regeneration after asexual reproduction. Zoomorphology. 2007;126:73–87. doi: 10.1007/s00435-007-0039-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shin JH, Mori C, Shiota K. Involvement of germ cell apoptosis in the induction of testicular toxicity following hydroxyurea treatment. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1999;155:139–149. doi: 10.1006/taap.1998.8593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koc A, Wheeler LJ, Mathews CK, Merrill GF. Hydroxyurea arrests DNA replication by a mechanism that preserves basal dNTP pools. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279:223–230. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303952200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higuchi S, Hayashi T, Hori I, Shibata N, Sakamoto H, Agata K. Characterization and categorization of fluorescence activated cell sorted planarian stem cells by ultrastructural analysis. Dev Growth Differ. 2007;49:571–581. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169X.2007.00947.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddien PW, Bermange AL, Murfitt KJ, Jennings JR, Sanchez AA. Identification of genes needed for regeneration, stem cell function, and tissue homeostasis by systematic gene perturbation in planaria. Dev Cell. 2005;8:635–649. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wollf E, Dubois F. Sur la migration des cellules de regeneration chez les planaires. Rev Suisse Zool. 1948;55:218–227. [Google Scholar]

- Zahradka K, Slade D, Bailone A, Sommer S, Averbeck D, Petranovic M. Reassembly of shattered chromosomes in Deinococcus radiodurans. Nature. 2006;443:569–573. doi: 10.1038/nature05160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agata K. Regeneration and gene regulation in planarians. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2003;13:492–496. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2003.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez AA. The case for comparative regeneration: learning from simpler organisms how to make new parts from old. J Reg Med. 2000;1:31–36. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi L, Salvetti A, Batistoni R, Deri P, Gremigni V. Planarians, a tale of stem cells. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:16–23. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-7426-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouton S, Willems M, Braeckman BP, Egger B, Ladurner P, Scharer L. The free-living flatworm Macrostomum lignano : a new model organism for ageing research. Exp Gerontol. 2009;44:243–249. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2008.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bode A, Salvenmoser W, Nimeth K, Mahlknecht M, Adamski Z, Rieger RM. Immunogold-labeled S-phase neoblasts, total neoblast number, their distribution, and evidence for arrested neoblasts in Macrostomum lignano (Platyhelminthes, Rhabditophora) Cell Tissue Res. 2006;325:577–587. doi: 10.1007/s00441-006-0196-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladurner P, Rieger R, Baguna J. Spatial distribution and differentiation potential of stem cells in hatchlings and adults in the marine platyhelminth macrostomum sp.: a bromodeoxyuridine analysis. Dev Biol. 2000;226:231–241. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieger R, Legnitit A, Ladurner P, Reiter D, Asch E, Salvenmoser W. Ultrastructure of neoblasts in microturbellaria: significance for understanding stem cells in free living Platyhelminthes. Invert Reprod Dev. 1999;35:127–140. [Google Scholar]

- Palmberg I. Stem cells in microturbellarians. Protoplasma. 1990;158:109–120. doi: 10.1007/BF01323123. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi T, Asami M, Higuchi S, Shibata N, Agata K. Isolation of planarian X-ray-sensitive stem cells by fluorescence-activated cell sorting. Dev growth differ. 2006;48:371–380. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169X.2006.00876.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hori I. Cytological approach to morphogenesis in the planarian blastema. II. The effect of neuropeptides. J Submicrosc Cytol Pathol. 1997;29:91–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen KJ. Cytological studies on the planarian neoblast. Zeitschr Zellforsch. 1959;50:799–817. doi: 10.1007/BF00342367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita M. Structure and function of the reticular cell in the planarian Dugesia dorotocephala. Hydrobiologia. 1995;305:189–196. doi: 10.1007/BF00036385. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Willms K, Merchant MT, Gomez M, Robert L. Taenia solium : germinal cell precursors in tapeworms grown in hamster intestine. Arch Med Res. 2001;32:1–7. doi: 10.1016/S0188-4409(00)00259-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AG, McKerr G. Tritiated thymidine ([3H]-TdR) and immunocytochemical tracing of cellular fate within the asexually dividing cestode Mesocestoides vogae (syn. M. corti) Parasitology. 2000;121(Pt 1):105–110. doi: 10.1017/S0031182099006010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson MK, Eriksson K. Never ending growth and a growth factor. I. Immunocytochemical evidence for the presence of basic fibroblast growth factor in a tapeworm. Growth Factors. 1992;7:327–334. doi: 10.3109/08977199209046415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meuleman EA, Holzmann PJ, Peet RC. The development of daughter sporocysts inside the mother sporocyst of Schistosoma mansoni with special reference to the ultrastructure of the body wall. Z Parasitenkd. 1980;61:201–212. doi: 10.1007/BF00925512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson MK. Studies on cytodifferentiation in the neck region of Diphyllobothrium dendriticum Nitzsch, 1824 (Cestoda, Pseudophyllidea) Z Parasitenkd. 1976;50:323–329. doi: 10.1007/BF02462976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meuleman EA, Holzmann PJ. The development of the primitive epithelium and true tegument in the cercaria of Schistosoma mansoni. Z Parasitenkd. 1975;45:307–318. doi: 10.1007/BF00329820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bode HR. The interstitial cell lineage of hydra: a stem cell system that arose early in evolution. J Cell Sci. 1996;109:1155–1164. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.6.1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma AK, Nelson MC, Brandt JE, Wessman M, Mahmud N, Weller KP. Human CD34(+) stem cells express the hiwi gene, a human homologue of the Drosophila gene piwi. Blood. 2001;97:426–434. doi: 10.1182/blood.V97.2.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown FD, Keeling EL, Le AD, Swalla BJ. Whole body regeneration in a colonial ascidian, Botrylloides violaceus. J Exp Zoolog B Mol Dev Evol. 2009;312:885–900. doi: 10.1002/jez.b.21303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Mulder K, Pfister D, Kuales G, Egger B, Salvenmoser W, Willems M. Stem cells are differentially regulated during development, regeneration and homeostasis in flatworms. Dev Biol. 2009;334:198–212. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agata K, Nakajima E, Funayama N, Shibata N, Saito Y, Umesono Y. Two different evolutionary origins of stem cell systems and their molecular basis. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2006;17:503–509. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zayas RM, Hernandez A, Habermann B, Wang Y, Stary JM, Newmark PA. The planarian Schmidtea mediterranea as a model for epigenetic germ cell specification: analysis of ESTs from the hermaphroditic strain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:18491–18496. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509507102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Zayas RM, Guo T, Newmark PA. Nanos function is essential for development and regeneration of planarian germ cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:5901–5906. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609708104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handberg-Thorsager M, Salo E. The planarian nanos-like gene Smednos is expressed in germline and eye precursor cells during development and regeneration. Dev Genes Evol. 2007;217:403–411. doi: 10.1007/s00427-007-0146-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddien PW, Sanchez AA. Fundamentals of planarian regeneration. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2004;20:725–757. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.010403.095114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger B, Ladurner P, Nimeth K, Gschwentner R, Rieger R. The regeneration capacity of the flatworm Macrostomum lignano - on repeated regeneration, rejuvenation, and the minimal size needed for regeneration. Dev Genes Evol. 2006;216:565–577. doi: 10.1007/s00427-006-0069-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfister D, De Mulder K, Philipp I, Kuales G, Hrouda M, Eichberger P. The exceptional stem cell system of Macrostomum lignano : screening for gene expression and studying cell proliferation by hydroxyurea treatment and irradiation. Front Zool. 2007;4:9. doi: 10.1186/1742-9994-4-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salo E, Baguna J. Regeneration and pattern formation in planarians. I. The pattern of mitosis in anterior and posterior regeneration in Dugesia (G) tigrina, and a new proposal for blastema formation. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1984;83:63–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denhollander JE, Erasmus DA. Schistosoma-mansoni - DNA-synthesis in males and females from mixed and single-sex infections. Parasitology. 1984;88:463–476. doi: 10.1017/S0031182000054731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azzi A, Cosseau C, Grunau C. Schistosoma mansoni: developmental arrest of miracidia treated with histone deacetylase inhibitors. Exp Parasitol. 2009;121:288–291. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2008.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heimfeld S, Bode HR. Growth regulation of the interstitial cell population in hydra. III. Interstitial cell density does not control stem cell proliferation. Dev Biol. 1986;116:51–58. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(86)90042-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heimfeld S, Bode HR. Growth regulation of the interstitial cell population in hydra. IV. Control of nerve cell and nematocyte differentiation by amplification of non-stem interstitial cells. Dev Biol. 1986;116:59–68. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(86)90043-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi L, Salvetti A, Marincola FM, Lena A, Deri P, Mannini L. Deciphering the molecular machinery of stem cells: a look at the neoblast gene expression profile. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R62. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-4-r62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orii H, Sakurai T, Watanabe K. Distribution of the stem cells (neoblasts) in the planarian Dugesia japonica. Dev Genes Evol. 2005;215:143–157. doi: 10.1007/s00427-004-0460-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvetti A, Rossi L, Lena A, Batistoni R, Deri P, Rainaldi G. DjPum, a homologue of Drosophila Pumilio, is essential to planarian stem cell maintenance. Development. 2005;132:1863–1874. doi: 10.1242/dev.01785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Åkesson B, Rice SA. New Dorvillea species (Polychaeta, Dorvilleidae) with obligate asexual reproduction. Zoologica scripta. 1992;21:351–362. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-6409.1992.tb00337.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coe W. Regeneration in nemerteans. J Exp Zool. 1929;54:411–459. doi: 10.1002/jez.1400540304. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baird J, McDowell SDR, Fairweather I, Murchie AK. Reproductive structures of Arthurdendyus triangulatus (Dendy): Seasonality and the effect of starvation. Pedobiologia. 2005;49:435–442. doi: 10.1016/j.pedobi.2005.05.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blackshaw RP. Life cycle of the earthworm predator Artioposthia triangulata (Dendy) in northern Ireland. Soil Biol Biochem. 1997;29:245–249. doi: 10.1016/S0038-0717(96)00090-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blackshaw RP. The planarian Artioposthia triangulata (Dendy) feeding on earthworms in soil columns. Soil Biol Biochem. 1997;29:299–302. doi: 10.1016/S0038-0717(96)00093-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blackshaw RP. The effect of starvation on size and survival of the terrestrial planarian Artioposthia-triangulata (Dendy) (Tricladida, Terricola) Ann Appl Biol. 1992;120:573–578. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7348.1992.tb04917.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boag B, Neilson R, Scrimgeour CM. The effect of starvation on the planarian Arthurdendyus triangulatus (Tricladida : Terricola) as measured by stable isotopes. Biology and fertility of soils. 2006;43:267–270. doi: 10.1007/s00374-006-0108-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Estevez C, Felix DA, Aboobaker AA, Salo E. Gtdap-1 promotes autophagy and is required for planarian remodeling during regeneration and starvation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:13373–13378. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703588104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oviedo NJ, Newmark PA, Sanchez AA. Allometric scaling and proportion regulation in the freshwater planarian Schmidtea mediterranea. Dev Dyn. 2003;226:326–333. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baguna J, Romero R. Quantitative analysis of cell types during growth, degrowth and regeneration in the planarians Dugesia mediterranea and Dugesia tigrina. Hydrobiologia. 1981;84:181–194. doi: 10.1007/BF00026179. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baguna J. Mitosis in the intact and regenerating planarian Dugesia mediterranea n.sp. I. Mitotic studies during growth, feeding and starvation. J Exp Zool. 1976;195:53–64. doi: 10.1002/jez.1401950106. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nimeth KT, Mahlknecht M, Mezzanato A, Peter R, Rieger R, Ladurner P. Stem cell dynamics during growth, feeding, and starvation in the basal flatworm Macrostomum sp. (Platyhelminthes) Dev Dyn. 2004;230:91–99. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RA, Berges RA, Harrison PJ, Watanabe MM. In: Algal culturing techniques. Anderson RA, editor. Burlington: Elsevier academic press; 2005. Appendix A- Recipes for freshwater and seawater media; enriched natural seawater media; p. 507. [Google Scholar]

- Karon M, Benedict WF. Chromatid breakage: differential effect of inhibitors of DNA synthesis during G 2 phase. Science. 1972;178:62. doi: 10.1126/science.178.4056.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1: Nucleotide sequence and predicted protein product of Ipiwi1. Conserved PAZ and PIWI domains highlighted in blue (PAZ) and green (PIWI). The piwi box within the piwi domain is marked in red. Start and stop codon are underlined and marked in bold. ISH primers are underlined within the sequence. Accession number for Ipiwi1 (AM942741).

Figure S2: Nucleotide sequence and predicted protein product of Ipiwi2. Conserved PAZ and PIWI domains are highlighted in blue (PAZ) and green (PIWI). The piwi box within the piwi domain is marked in red. Start and stop codon are underlined and marked in bold. ISH primers are underlined within the sequence. Accession number for Ipiwi2 (AM942742).

Figure S3:. Alignment of predicted piwi-like genes from I. pulchra with piwi-like genes from other species. (A) Amino acid alignment of the conserved PAZ domain. (B) Amino acid alignment of the conserved PIWI domain. The PIWI box is highlighted in purple. Amino acids indicated with green asterisks are supposed to create a binding pocket for the 5'phosphate group of binding RNA. Red asterisks indicate putative RNase active site carboxylate residues. Amino acids indicated in purple can distinguish members of the piwi and argonaute subfamily. The Genbank accession numbers: Isodiametra pulchra Ipiwi1 (AM942741); Isodiametra pulchra Ipiwi2 (AM942742); Macrostomum lignano Macpiwi (AM942740); Schmidtea mediterranea Smedwi1 (DQ186985) Smedwi2 (DQ186986); Dugesia japonica DjPiwi1 (AJ865376); Podocoryne carnea Cniwi (AAS01181); Caenorhabditis elegans PRG1 (NP492121); Drosophila melanogaster DmPiwi (AF104354); Strongylocentrotus purpuratus Seawi (AY014899); Homo sapiens Hiwi (AF104260).