Abstract

Tuberculosis remains a fatal disease caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which contains various unique components that affect the host immune system. Trehalose-6,6′-dimycolate (TDM; also called cord factor) is a mycobacterial cell wall glycolipid that is the most studied immunostimulatory component of M. tuberculosis. Despite five decades of research on TDM, its host receptor has not been clearly identified. Here, we demonstrate that macrophage inducible C-type lectin (Mincle) is an essential receptor for TDM. Heat-killed mycobacteria activated Mincle-expressing cells, but the activity was lost upon delipidation of the bacteria; analysis of the lipid extracts identified TDM as a Mincle ligand. TDM activated macrophages to produce inflammatory cytokines and nitric oxide, which are completely suppressed in Mincle-deficient macrophages. In vivo TDM administration induced a robust elevation of inflammatory cytokines in sera and characteristic lung inflammation, such as granuloma formation. However, no TDM-induced lung granuloma was formed in Mincle-deficient mice. Whole mycobacteria were able to activate macrophages even in MyD88-deficient background, but the activation was significantly diminished in Mincle/MyD88 double-deficient macrophages. These results demonstrate that Mincle is an essential receptor for the mycobacterial glycolipid, TDM.

Many pathogens are directly recognized by pattern recognition receptors such as Toll-like receptors (TLRs), RIG-I–like helicases, or NOD-like receptors of the host cells (Akira et al., 2006), most of which sense the characteristic signatures of pathogens. Recently, some members of the C-type lectin family have also been identified as pattern recognition receptors for bacteria or fungi; however, the ligands of most C-type lectin receptors remain unidentified (Robinson et al., 2006).

Among these C-type lectin receptors is Mincle (macrophage inducible C-type lectin, also called Clec4e or Clecsf9), which is expressed in macrophages subjected to several types of stress (Matsumoto et al., 1999). Mincle possesses carbohydrate recognition domain (CRD) within the extracellular region. We recently reported that Mincle is associated with an immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif –containing Fc receptor γ chain (FcRγ) and functions as an activating receptor for damaged self- and non–self-pathogenic fungi (Yamasaki et al., 2008, 2009).

Tuberculosis is caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis that infects one third of the world's population (Hunter et al., 2006). M. tuberculosis contains various unique components that affect the host immune system through both identified and unidentified receptors (Jo, 2008). Among these, the cord factor is the first immunostimulatory component to be identified that might elicit pulmonary inflammation, a characteristic feature of mycobacterial infection (Bloch, 1950; Yamaguchi et al., 1955). In 1956, the chemical structure of the cord factor was established as trehalose-6,6′-dimycolate (TDM; Noll et al., 1956), which is the most abundant glycolipid in the mycobacterial cell wall (Hunter et al., 2006). The long-chain lipids of TDM represent a structural component of the hydrophobic cell wall that is critical for the survival of mycobacteria within the phagosome of host cells (Indrigo et al., 2002). TDM has been shown to possess unique immunostimulatory activity, such as granulomagenesis, adjuvant activity for cell-mediated immune responses, humoral responses, and tumor regression (Hunter et al., 2006). Recently, Marco and TLR are proposed as TDM receptor (Bowdish et al., 2009), whereas other group suggested that FcRγ-coupled receptor(s) are candidates (Werninghaus et al., 2009). Thus, the receptor for TDM is still controversial.

Some C-type lectins are involved in the recognition of M. tuberculosis (Jo, 2008). Mannose receptor expressed on macrophages is reported to mediate phagocytosis of mycobacteria (Kang et al., 2005). Another C-type lectin receptor, DC-SIGN, is known to recognize mycobacteria (Tailleux et al., 2003), but its binding results in the down-regulation of dendritic cell–mediated immune responses (Geijtenbeek et al., 2003). Dectin-1 is reported to recognize mycobacteria through an unknown ligand (Yadav and Schorey, 2006; Rothfuchs et al., 2007). Other C-type lectins could potentially recognize mycobacteria, but the activating lectin receptors for mycobacteria in macrophages have not been clearly identified.

In this study, we show that Mincle is a direct receptor for mycobacterial TDM. We further demonstrate, through Mincle-deficient mice, that Mincle is an essential receptor for TDM-dependent inflammatory responses.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

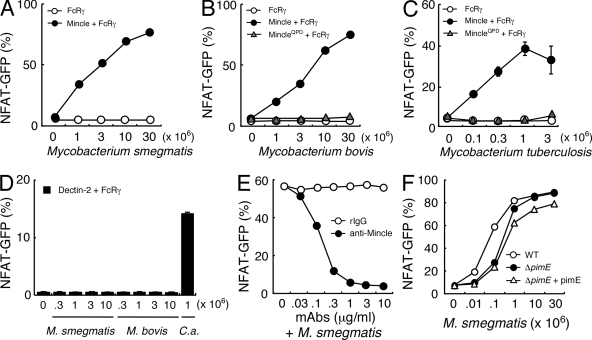

Mincle can recognize mycobacteria

We first investigated whether Mincle recognizes mycobacteria through the use of NFAT-driven GFP reporter cells that express Mincle and its signaling subunit, the FcRγ chain (Yamasaki et al., 2008). The heat-killed mycobacterial species Mycobacterium smegmatis and Mycobacterium bovis Bacille de Calmette et Guerin clearly activated NFAT-GFP in reporter cells expressing FcRγ with Mincle (Fig. 1, A and B). Importantly, the virulent strain M. tuberculosis H37Rv also showed substantial ligand activity against Mincle (Fig. 1 C).

Figure 1.

Mincle recognizes mycobacterial species. (A–C) NFAT-GFP reporter cells expressing FcRγ only (FcRγ), Mincle + FcRγ, and MincleEPN→QPD + FcRγ were co-cultured for 18 h with heat-killed M. smegmatis (A), M. bovis (B), or M. tuberculosis H37 Rv (C). Induction of NFAT-GFP was analyzed by flow cytometry. (D) Reporter cells expressing Dectin-2 + FcRγ were stimulated with M. smegmatis, M. bovis, and Candida albicans (C. a.). (E) Reporter cells expressing Mincle + FcRγ were stimulated with 107 M. smegmatis together with anti-Mincle mAb and rat IgG1 as a control. (F) Cells were stimulated with wild-type M. smegmatis (WT), pimE-deficient M. smegmatis (ΔpimE), and pimE-deficient M. smegmatis reconstituted with pimE (ΔpimE + pimE). All data are means ± SD for triplicate assays, and representative results from three independent experiments with similar results are shown.

The recognition of mycobacteria by Mincle was shown to require the Glu-Pro-Asn (EPN) sequence, a putative mannose-binding motif within CRD, as the activity was eliminated by introducing a mutation of EPN into QPD (MincleQPD; Fig. 1, B and C; Drickamer, 1992). However, the similar immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif–coupled C-type lectin Dectin-2 (Sato et al., 2006) was not capable of recognizing mycobacteria (Fig. 1 D), suggesting selective recognition for Mincle. Indeed, activation of NFAT by mycobacteria was completely blocked in the presence of anti-Mincle mAb (Fig. 1 E).

As a putative mannose-binding motif within Mincle was essential for the recognition process (Fig. 1, B and C), we initially assumed that Mincle could recognize terminal α1,2 mannose residues of mycobacterial molecules, such as phosphatidylinositol mannoside (PIM), lipomannan, or lipoarabinomannan (LAM). To examine the contribution of PIM, we used mutant strains of mycobacteria lacking the terminal α1,2 mannose residues. M. smegmatis ΔpimE, a deletion mutant of mannosyl-transferase PimE, lacks mature PIMs (Fig. S1; Morita et al., 2006). However, ΔpimE still retained stimulatory activity at a comparable level to PimE-sufficient strains such as wild-type M. smegmatis and pimE-reconstituted ΔpimE strain (Fig. 1 F). In addition, a mutant M. smegmatis strain deficient in α1,2 mannose of lipomannan and LAM could be recognized normally by Mincle, and purified LAM alone did not activate Mincle-expressing cells (unpublished data).

These results show that mycobacteria can be recognized by Mincle, but their α1,2 mannose-containing glycolipids appears not to be necessary for recognition to occur.

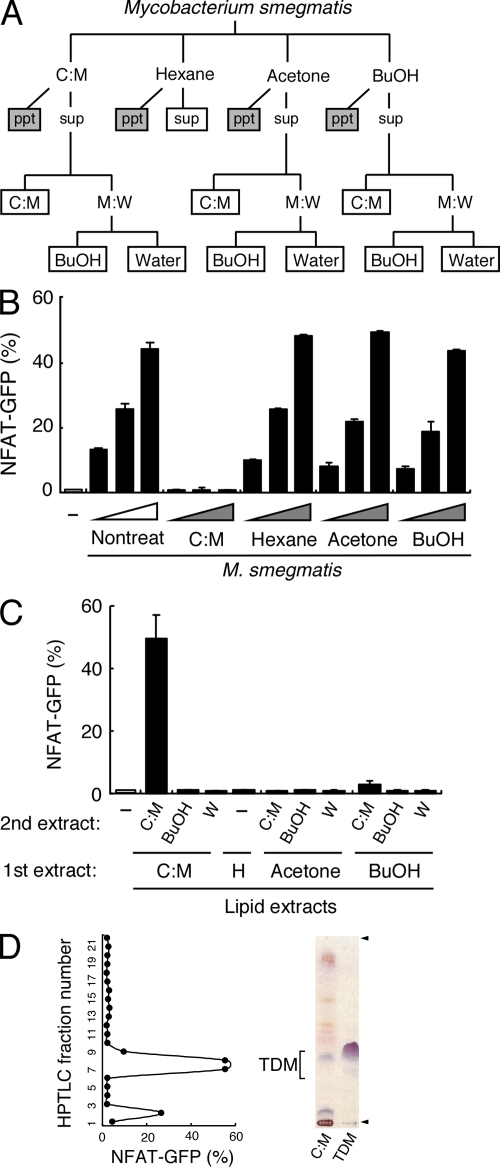

Identification of mycobacterial glycolipids recognized by Mincle

Mycobacteria have a wealth of unique lipids on their cell walls, some of which presumably protect the bacteria from the host's defense system. To examine the contribution of other mycobacterial lipids as a potential candidate for a Mincle ligand, we extracted the lipids from M. smegmatis using various organic solvents (Fig. 2 A). M. smegmatis treated with chloroform:methanol (C:M) selectively lost their Mincle-stimulating activity (Fig. 2 B). Simultaneously, we analyzed the activity of extracted lipid fractions in plate-coated form and found that only the C:M phase after C:M extraction showed strong stimulatory activity (Fig. 2 C). We further analyzed this active fraction by means of high-performance thin-layer chromatography (HPTLC) and separated it into 22 subfractions to identify the active lipid components. Purified extracts from these subfractions showed strong ligand activity peaked at subfractions #7-9 (Fig. 2 D). Orcinol staining revealed a purple-red band at the position corresponding to subfractions #7-9 (Fig. 2 D, left lane), indicating that the ligand contains a sugar moiety. Furthermore, the purple-red band migrated to a position similar to that of purified TDM derived from M. tuberculosis (Fig. 2 D, right lane). From these characteristics, we hypothesized that TDM could be a candidate for the Mincle ligand. Subfraction #2 also showed weak activity, implying that trehalose monomycolate (TMM), a precursor of TDM biosynthesis, could also act as weak ligand, as previously suggested (Sueoka et al., 1995).

Figure 2.

Mincle recognizes mycobacterial trehalose-6,6′-dimycolate. (A) Schematic diagram of delipidation of M. smegmatis. Delipidated bacteria (gray boxes) and lipid extracts (open boxes) were applied for ligand assays in B and C, respectively. (B and C) Heat-killed M. smegmatis treated with C:M, hexane, acetone, or 1-butanol (BuOH; B), and plate-coated lipid extract (C) were co-cultured with reporter cells expressing Mincle + FcRγ. (D) C:M phase of C:M extract was analyzed by HPTLC and divided into 22 subfractions. Each subfraction was coated onto a plate to stimulate reporter cells. Purified TDM was used as a reference (right lane). Arrowheads show the origin and solvent front. Data are means ± SD for triplicate assays (B and C) or means for duplicate assays (D). Representative results from three independent experiments with similar results are shown.

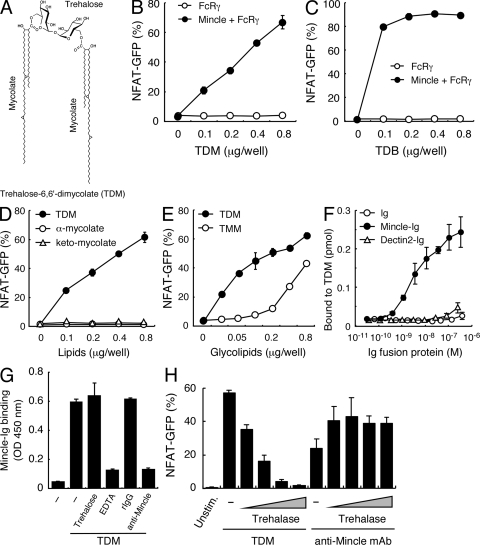

TDM as a Mincle ligand

Indeed, we found that purified TDM, the structure of which is shown in Fig. 3 A, dramatically activated Mincle-expressing cells in plate-coated form (Fig. 3 B). The TDM analogue trehalose dibehenate (TDB), which is also used as a synthetic adjuvant, was a strong ligand for Mincle, as well (Fig. 3 C).

Figure 3.

Purified TDM is recognized by Mincle. (A) Chemical structure of TDM. α-Mycolate (shown), methoxy-mycolate, and keto-mycolate are the major subclasses of mycolate found in M. tuberculosis TDM. (B and C) Reporter cells were stimulated with the indicated amount of plate-coated TDM (B) or TDB (C). (D) Reporter cells were stimulated with the indicated amount of TDM, methyl α-mycolate (α-mycolate), or methyl keto-mycolate (keto-mycolate). (E) Reporter cells were stimulated with the indicated amount of TDM and TMM. (F) ELISA-based detection of TDM by Mincle-Ig. hIgG1-Fc (Ig), Mincle-Ig, and Dectin2-Ig were incubated with 0.1 nmol/0.32 cm2 of plate-coated TDM. Bound protein was detected with anti–hIgG-HRP followed by the addition of colorimetric substrate. (G) Effect of trehalose (100 µg/ml), EDTA (10 mM), rat IgG (10 µg/ml), and anti-Mincle mAb (10 µg/ml) on TDM recognition by Mincle-Ig. ELISA-based detection was performed as in E. (H) Reporter cells were stimulated with TDM, which was treated with trehalase as described in Materials and methods. Cells were also stimulated with plate-coated anti-Mincle mAb treated with trehalase as a negative control. All data are means ± SD for triplicate assays and representative results from three independent experiments with similar results are shown.

TDM consists of a trehalose moiety and two mycolate chains (Fig. 3 A), but purified mycolate did not itself activate Mincle-expressing cells (Fig. 3 D). To examine whether TMM also possesses ligand activity or not, we generated TMM by partial alkaline deacylation of TDM. As shown in Fig. 3 E, TMM could potentially activate Mincle-expressing cells, albeit less potent than TDM. Soluble trehalose had no stimulatory activity, and a large excess of trehalose did not block TDM-mediated NFAT activation (unpublished data). Thus, a combination of both the sugar and lipid moieties appears to be critical for the ligand activity of TDM.

Next, to verify the direct interaction between Mincle and TDM, we prepared soluble Mincle protein (Mincle-Ig). As detected by anti-hIgG, Mincle-Ig, but not other control proteins such as Ig or Dectin2-Ig, selectively binds to plate-coated TDM (Fig. 3 F). This biochemical data provides further proof that TDM is a direct Mincle ligand. This binding was blocked by EDTA and anti-Mincle mAb but not by excess trehalose, suggesting that Mincle recognizes specific glycolipid structures in a cation-dependent manner (Fig. 3 G).

It was recently proposed that TDM on mycobacterial cell wall could be converted into glucose monomycolate (GMM) in the host cell environment (Matsunaga et al., 2008). To test the hypothesis that this conversion may be of advantage to mycobacteria in escaping from Mincle-mediated recognition, we attempted to mimic the conversion in vitro by using trehalase, which hydrolyzed trehalose into two glucose units (Asano et al., 1996). Intriguingly, the trehalase treatment impaired the ligand activity of TDM (Fig. 3 H). Note that this enzymatic treatment did not grossly disrupt Mincle-mediated responses because stimulation by plate-coated anti-Mincle mAb was not affected by the trehalase treatment (Fig. 3 H). This finding is consistent with the idea that mycobacteria convert TDM into GMM upon infection into host, presumably to escape from Mincle-mediated host immunity (Fig. S2; Matsunaga et al., 2008). Intriguingly, it has also been reported that as a possible counterdefense, host cells present this GMM on group1 CD1 molecules in human to provoke TCR-mediated acquired immune responses against mycobacteria (Moody et al., 1997; Matsunaga et al., 2008). Importantly, we found that TDM is recognized by human Mincle as well as murine Mincle (unpublished data).

Collectively, these results suggest that, among various mycobacterial components, Mincle is specific for the ester linkage of a fatty acid to trehalose.

Mincle is essential for TDM-dependent macrophage activation

TDM also activated macrophages to produce nitric oxide (NO), which is critical for direct killing of mycobacteria. However, NO production was almost completely suppressed in Mincle−/− macrophages (Fig. 4 A). In contrast, LPS induced a similar response in Mincle−/− cells to that in WT cells. Inducible NO synthase (iNOS) is the enzyme responsible for production of NO. The transcriptional induction of iNOS by TDM stimulation was also completely suppressed in Mincle−/− mice (Fig. 4 B).

Figure 4.

Lack of TDM-mediated activation in Mincle-deficient macrophages. (A) BMMφ from Mincle+/− and Mincle−/− were primed with IFN-γ (10 ng/ml) and stimulated with plate-coated TDM or LPS (10 ng/ml) as a control. Culture supernatants were collected at 48 h and concentration of NO was measured. (B) IFN-γ–primed BMMφ were stimulated with plate-coated TDM for 36 h as in A, and mRNA expression of iNOS was analyzed by real-time PCR. (C and D) IFN-γ–primed BMMφ were stimulated with plate-coated TDM (C) or TDB (D) for 24 h. Culture supernatants were collected and concentrations of TNF and MIP-2 were determined by ELISA. All data are means ± SD for triplicate assays and representative results from three independent experiments with similar results are shown.

The crucial role of TNF has been reiterated by the recent observation of patients suffering from the reactivation of latent tuberculosis infection upon anti-TNF therapy for autoimmune diseases (Winthrop, 2006). TDM stimulation induced the production of TNF and MIP-2 (also called CXCL2), which are potent chemoattractant factors for inflammatory cells. However, these cytokines were not produced upon TDM stimulation in the absence of Mincle (Fig. 4 C). Similarly, TDB-induced cytokine production was also eliminated in Mincle−/− macrophages (Fig. 4 D).

We have previously reported that Mincle transduces signal through the FcRγ–CARD9 signaling axis (Yamasaki et al., 2008). In line with these observations, it was recently reported that TDM and TDB activates macrophage in an FcRγ- and CARD9-dependent manner (Werninghaus et al., 2009). Thus, Mincle is an essential receptor for macrophage activation elicited by TDM and TDB.

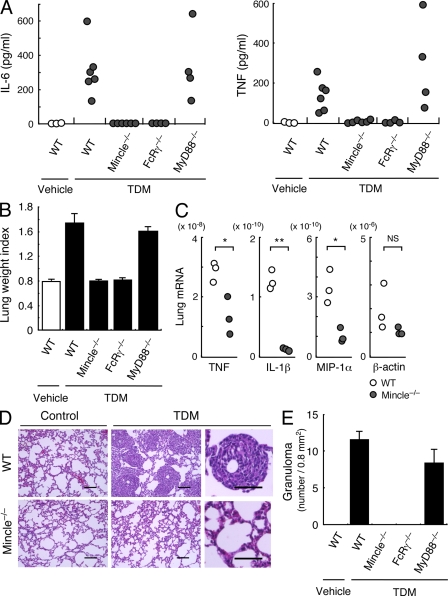

TDM-induced lung granuloma formation requires Mincle

In vivo administration of TDM is capable of inducing inflammatory symptoms characteristic of tuberculosis (Yamaguchi et al., 1955; Hunter et al., 2006). Single injection of TDM into mice induced the robust production of inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6 and TNF, in sera. However, these were completely eliminated in Mincle−/− mice (Fig. 5 A). FcRγ is an essential signaling subunit for Mincle (Yamasaki et al., 2008). Indeed, FcRγ−/− mice did not detectably respond to TDM in vivo (Fig. 5 A). In contrast, TDM was able to induce cytokine production in MyD88−/− mice, suggesting that TLRs are not essential for TDM recognition (Fig. 5 A; Werninghaus et al., 2009), although potential roles of TLR2 and TLR4 have been proposed (Bowdish et al., 2009). TDM also induced inflammatory lung swelling as assessed by lung weight index (LWI), but this was totally dependent on the Mincle–FcRγ axis (Fig. 5 B and Fig. S3). In concert with the acute lung inflammation, the up-regulation of mRNA for inflammatory cytokines/chemokines upon TDM treatment was severely impaired in Mincle−/− mice (Fig. 5 C). In addition, TDM induced thymic atrophy in mice, and was also Mincle dependent (Fig. S4).

Figure 5.

Mincle is essential for TDM-induced inflammation in vivo. (A) Mincle+/+, Mincle−/−, FcRγ−/− and Myd88−/− mice were injected intravenously with an oil-in-water emulsion containing TDM (150 µg). Emulsion without TDM was injected as a vehicle control. At day 1 after injection, IL-6 and TNF concentrations in sera were determined by ELISA. Each symbol represents an individual mouse. (B) Lungs of TDM-injected mice were removed at day 7 and inflammatory intensity was evaluated by calculation of LWI. (C) Proinflammatory mediator mRNA levels in lungs at day 7 after TDM administration were evaluated by real-time PCR. Relative expression levels are shown as 2−Ct. Each symbol represents an individual mouse. Ct, cycle threshold. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.001. NS, not significant. (D) Histology of the lungs from untreated (control) and TDM-injected (TDM) mice was examined by hematoxylin-eosin staining at day 7. Bar, 0.1 mm. (E) Number of lung granulomas. Granuloma in lungs from mice injected with TDM was counted as described in Materials and methods. Data are means ± SD for the mean number for at least three independent mice. Representative results from two independent experiments with similar results are shown.

Granulomas are complex aggregates of immune cells, and are widely believed to constrain mycobacterial infection by physically surrounding the infecting bacteria (Adams, 1976). TDM alone dramatically induced granuloma formation, which is a characteristic of mycobacterial infection at day 7 after administration (Fig. 5 D). Strikingly, no granuloma formation was observed in the lungs of TDM-treated Mincle−/− mice (Fig. 5 D). Quantitative analysis on multiple sections revealed that granuloma was completely eliminated in Mincle−/− and FcRγ−/− mice, but was induced normally in MyD88−/− mice (Fig. 5 E). Thus, Mincle is a critical receptor for TDM-induced granuloma formation, most likely through the production of inflammatory cytokines/chemokines to recruit inflammatory cells (Welsh et al., 2008).

These results show that Mincle is an essential receptor for TDM-mediated inflammatory responses in vivo.

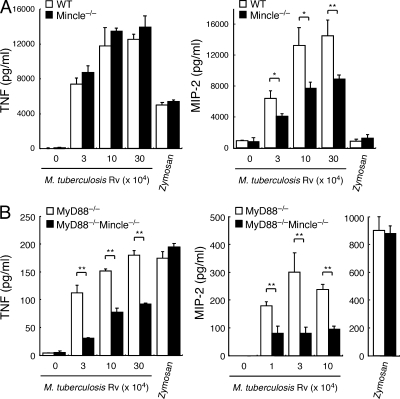

Role of Mincle in response to whole mycobacteria

Finally we investigated the role of Mincle in response to whole mycobacteria using virulent strain, M. tuberculosis H37Rv. Heat-killed mycobacteria induced vigorous production of TNF and MIP-2 in macrophages, whereas Mincle deficiency did not detectably impair the production of TNF and only partially impaired MIP-2 production (Fig. 6 A). This is probably because whole mycobacteria possess many immunostimulatory components other than TDM, including TLR ligands (Jo, 2008). Indeed, cytokine production was markedly decreased, but was substantially induced in MyD88−/− macrophages (Fig. 6 B; Fremond et al., 2004). However, the level of these cytokines was significantly reduced in MyD88−/−Mincle−/− double-deficient macrophages when compared with MyD88−/− macrophages (Fig. 6 B). In contrast, the response to zymosan, which is known to be recognized by Dectin-1 and TLR2, in MyD88−/− macrophages was the same as that in MyD88−/−Mincle−/− cells (Fig. 6). These results suggest that Mincle plays a major role in TLR-independent recognition of mycobacteria. The remaining production of cytokines by mycobacteria observed in MyD88−/−Mincle−/− macrophages (Fig. 6 B) may reflect a possible contribution of the NOD-like receptor family NOD2, which was reported to recognize mycobacteria through muramyl dipeptide (Coulombe et al., 2009).

Figure 6.

Mincle is responsible for the TLR-independent pathway of anti-mycobacterium responses. (A and B) BMMφ from WT, Mincle−/− (A), MyD88−/−, and MyD88−/−Mincle−/− (B) mice were stimulated with indicated number of heat-killed M. tuberculosis H37Rv. Cells were also stimulated with zymosan as a positive control. At day 2 after stimulation, production of TNF and MIP-2 in supernatants was determined. Data are means ± SD for triplicate assays and representative results from three independent experiments with similar results are shown. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

Concluding remarks

TDM (also called cord factor) is an essential component that permits the survival of mycobacteria within the host cells (Indrigo et al., 2002), whereas it is barely present in vertebrates. It would therefore be a reasonable strategy for the host to recognize TDM as a signal of mycobacterial infection. In this study, we identified C-type lectin Mincle as an essential receptor for TDM.

It was demonstrated that cyclopropane within mycolate chain of TDM is critical for its immunostimulatory activity (Rao et al., 2005). However, TDB, which lacks the cyclopropane in the carbon chain, is still capable of activating macrophages and Mincle-expressing cells (Fig. 3 C and Fig. 4 D; Werninghaus et al., 2009). On the other hand, it has been suggested that specific configuration of TDM is necessary to exert its activity (Retzinger et al., 1981). Therefore the “kink” in the carbon chain of TDM may contribute to the optimal presentation of polar head to Mincle, rather than as a direct binding site for Mincle. It could be hypothesized that two Mincle receptors recognize one disaccharide head of TDM, presumably together with a proximal region of mycolate, although further structural analysis is needed to clarify this issue.

TDM has been known to induce lung granuloma in vivo, and we demonstrated that it is totally dependent on Mincle. We have recently found that Mincle also senses dead cells and recruits inflammatory cells (Yamasaki et al., 2008). Because the presence of necrotic cells in the center of a granuloma is a characteristic feature of tuberculosis (Adams, 1976), both TDM and dead cells may contribute cooperatively to the formation of granuloma through Mincle-mediated secretion of inflammatory cytokines/chemokines. The physiological role of Mincle during virulent infection is a critical issue that needs to be clarified and is now under investigation using Mincle−/− mice, as the contribution of TDM in the virulence of mycobacteria is still controversial (Hunter et al., 2006). Given its potent granuloma-inducing capacity, Mincle might also be involved in diseases characterized by granulomas.

Recent studies have suggested that T cells can respond to TDM, despite little evidence of CD1-mediated TDM presentation (Guidry et al., 2004; Otsuka et al., 2008). Mincle is also expressed in T cells upon activation (unpublished data), and some T cell populations use FcRγ (Ohno et al., 1994). It is tempting to speculate that such T cells may directly recognize TDM to produce T cell–specific cytokines, such as IFN-γ or IL-17, in a “TCR-independent” but “Mincle-dependent” manner.

We recently discovered that Mincle also recognizes the pathogenic fungus Malassezia (Yamasaki et al., 2009). Our current findings could suggest that Mincle uniquely recognizes glycolipid through the motifs that have generally been considered as mannose-binding motifs. We therefore speculate that the Mincle–Malassezia interaction might be mediated by unique fungal glycolipids similar to TDM. Interestingly, Malassezia species among other fungi uniquely require lipid for their growth (Schmidt, 1997).

TDM and its synthetic analogue, TDB, have been extensively studied because they are effective adjuvants (Azuma and Seya, 2001). It is believed that TDM accounts for part of the effect of CFA (Billiau and Matthys, 2001). Identification of the host receptor for TDM/TDB will provide valuable information related to the design of vaccine adjuvants, because rational screening of synthetic Mincle ligands is now feasible and could potentially lead to the development of an ideal synthetic adjuvant. Such a synthetic Mincle ligand could allow efficient vaccination against tuberculosis, other infectious diseases, and cancers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

Mincle-deficient mice were used as C57BL/6 and 129 mixed genetic background (Yamasaki et al., 2009). MyD88-deficient mice were purchased from Oriental Yeast. FcRγ-deficient mice on a C57BL/6 background were provided by T. Saito (RIKEN, Yokohama, Japan; Park et al., 1998). C57BL/6 mice were obtained from Japan Clea or Kyudo. All mice were maintained in a filtered-air laminar-flow enclosure and given standard laboratory food and water ad libitum. Animal protocols were approved by the committee of Ethics on Animal Experiment, Faculty of Medical Sciences, Kyushu University.

Bacteria.

M. smegmatis strain mc2155 were cultured in Middlebrook 7H9 broth as previously described (Morita et al., 2005). M. bovis Bacille de Calmette et Guerin were cultured in Middlebrook 7H9 supplemented with Middlebrook ADC enrichment and 0.05% Tween-80. M. smegmatis ΔpimE, which is a mutant deficient in mannosyltransferase PimE, lacks α1,2-mannose moiety of PIM. M. smegmatis and M. bovis were heat-killed by pasteurization at 63°C for 40 min. Virulent strain M. tuberculosis H37Rv was autoclaved before use. Candida albicans (IFM No. 54349) was provided by T. Gonoi (Chiba University, Chiba, Japan).

Delipidation.

M. smegmatis was delipidated with C:M (2:1), hexane, acetone, or 1-butanol (BuOH). Insoluble fractions were collected as delipidated bacteria. Soluble fractions were further partitioned by C:M:W (8:4:3; vol/vol) into lower organic phase (C:M) and upper aqueous phase (M:W). Upper aqueous phase (M:W) was further partitioned by 1-butanol:water (1:1; vol/vol) into upper butanol phase (BuOH) and lower aqueous phase (water). Each fraction was dried, resuspended in DMSO relative to the original cell pellet weight, and tested as lipid extracts (Morita et al., 2005).

Reagent.

TDM, Methyl α-mycolate, Methyl keto-mycolate, and LAM were purchased from Nakalai tesque and TDB was obtained from Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc. D-Trehalose dihydrate (T3663), Trehalase (T8778), LPS (L4516), and zymosan (Z4250) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. For stimulation of reporter cells and bone marrow–derived macrophages (BMMφ), TDM and TDB dissolved in chloroform at 1 mg/ml were diluted in isopropanol and added on 96-well plates at 20 µl/well, followed by evaporation of the solvent as previously described (Ozeki et al., 2006). For generation of TMM, TDM was partially acylated with 0.4 M NaOH for 10 min, and the amount of TDM and TMM was determined by orcinol staining on HPTLC. Corresponding fraction to TDM and TMM was collected and used for assay.

Cells.

2B4-NFAT-GFP reporter cells expressing WT Mincle or MincleQPD (E169Q/N171D) mutant and BMMφ were prepared as previously described (Yamasaki et al., 2008). BMMφ pretreated with 10 ng/ml IFN-γ for 4 h and reporter cells were stimulated with various bacteria and bacterial cell wall components. Activation of NFAT-GFP was monitored by flow cytometry. The levels of cytokines were determined by ELISA. NO production was measured by Griess assay.

Antibodies.

Anti-Mincle mAbs were established as described previously (Yamasaki et al., 2008) and clone 1B6 (IgG1, κ) was used in this study. HRP-conjugated anti–human IgG (109–035-088) was from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories.

Ig fusion protein.

The extracellular domain of Mincle (a.a. 46–214) and Dectin2 (a.a. 43–209) was fused to hIgG1 Fc region and prepared as described previously (Yamasaki et al., 2009).

Trehalase treatment.

0.8 µg TDM was coated on a 96-well plate as described in the Reagents section, followed by incubation with 1 to 10 mU/ml of Trehalase in 10 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 5.9) at 37°C for 6 h.

Quantitative RT-PCR.

Total RNA was isolated from stimulated BMMφ or lungs of TDM-administrated mice subjected to real-time PCR (Applied Biosystems). Sequence of gene-specific primers is available upon request.

Administration of TDM.

TDM was prepared as oil-in-water emulsion consisting of mineral oil (9%), Tween-80 (1%), and saline (90%) as previously described (Numata et al., 1985). 100 µl of emulsion containing 150 µg of TDM was injected intravenously into 6–11-wk-old mice. Emulsion without TDM was injected as a vehicle control. At day 7, thymocyte number was calculated and lungs were weighed and fixed in 10% formaldehyde for hematoxylin-eosin staining. A part of lungs was frozen for quantitative RT-PCR. LWI was calculated as described (Guidry et al., 2004). The number of granulomas was determined by counting focal mononuclear cell infiltrations in randomized 10 microscopic fields (0.8 mm2) per mouse.

Statistics.

An unpaired two-tailed Student's t test was used for all the statistical analyses.

Online supplemental material.

Fig. S1 shows schematic structure of PIM in M. smegmatis mutant. Fig. S2 shows schematic representation of hypothetical evolutional struggle between mycobacteria and host immunity. Fig. S3 shows lack of TDM-induced pulmonary inflammation in Mincle−/− mice. Fig. S4 shows impaired TDM-induced thymic atrophy in Mincle−/− mice. Online supplemental material is available at http://www.jem.org/cgi/content/full/jem.20091750/DC1.

Acknowledgments

We thank Y. Fukui, H. Hara, R. Kakutani, and Y. Miyake for discussion; A. Suzuki, and M. Tanaka, H. Koseki, and T. Hasegawa for embryonic engineering; T. Saito for providing FcRγ-deficient mice; Y. Esaki, A. Oyamada and M. Sakuma for technical assistance; and Y. Nishi and H. Yamaguchi for secretarial assistance. We also thank N. Kinoshita (Laboratory for Technical Support, Medical Institute of Bioregulation, Kyushu University) for histochemical staining.

This work was supported by Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (S) and Takeda Science Foundation.

The authors have no conflicting financial interests.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used:

- C:M

- chloroform:methanol

- CRD

- carbohydrate recognition domain

- HPTLC

- high-performance thin-layer chromatography

- iNOS

- inducible NO synthase

- LAM

- lipoarabinomannan

- LWI

- lung weight index

- Mincle

- macrophage inducible C-type lectin

- NO

- nitric oxide

- PIM

- phosphatidylinositol mannoside

- TDB

- trehalose dibehenate

- TDM

- trehalose-6,6′-dimycolate

- TLR

- Toll-like receptor

- TMM

- trehalose monomycolate

References

- Adams D.O. 1976. The granulomatous inflammatory response. A review. Am. J. Pathol. 84:164–192 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akira S., Uematsu S., Takeuchi O. 2006. Pathogen recognition and innate immunity. Cell. 124:783–801 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asano N., Kato A., Matsui K. 1996. Two subsites on the active center of pig kidney trehalase. Eur. J. Biochem. 240:692–698 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0692h.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azuma I., Seya T. 2001. Development of immunoadjuvants for immunotherapy of cancer. Int. Immunopharmacol. 1:1249–1259 10.1016/S1567-5769(01)00055-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billiau A., Matthys P. 2001. Modes of action of Freund's adjuvants in experimental models of autoimmune diseases. J. Leukoc. Biol. 70:849–860 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloch H. 1950. Studies on the virulence of tubercle bacilli; isolation and biological properties of a constituent of virulent organisms. J. Exp. Med. 91:197–218 10.1084/jem.91.2.197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowdish D.M., Sakamoto K., Kim M.J., Kroos M., Mukhopadhyay S., Leifer C.A., Tryggvason K., Gordon S., Russell D.G. 2009. MARCO, TLR2, and CD14 are required for macrophage cytokine responses to mycobacterial trehalose dimycolate and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000474 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulombe F., Divangahi M., Veyrier F., de Léséleuc L., Gleason J.L., Yang Y., Kelliher M.A., Pandey A.K., Sassetti C.M., Reed M.B., Behr M.A. 2009. Increased NOD2-mediated recognition of N-glycolyl muramyl dipeptide. J. Exp. Med. 206:1709–1716 10.1084/jem.20081779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drickamer K. 1992. Engineering galactose-binding activity into a C-type mannose-binding protein. Nature. 360:183–186 10.1038/360183a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fremond C.M., Yeremeev V., Nicolle D.M., Jacobs M., Quesniaux V.F., Ryffel B. 2004. Fatal Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection despite adaptive immune response in the absence of MyD88. J. Clin. Invest. 114:1790–1799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geijtenbeek T.B., Van Vliet S.J., Koppel E.A., Sanchez-Hernandez M., Vandenbroucke-Grauls C.M., Appelmelk B., Van Kooyk Y. 2003. Mycobacteria target DC-SIGN to suppress dendritic cell function. J. Exp. Med. 197:7–17 10.1084/jem.20021229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidry T.V., Olsen M., Kil K.S., Hunter R.L., Jr., Geng Y.J., Actor J.K. 2004. Failure of CD1D−/− mice to elicit hypersensitive granulomas to mycobacterial cord factor trehalose 6,6′-dimycolate. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 24:362–371 10.1089/107999004323142222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter R.L., Olsen M.R., Jagannath C., Actor J.K. 2006. Multiple roles of cord factor in the pathogenesis of primary, secondary, and cavitary tuberculosis, including a revised description of the pathology of secondary disease. Ann. Clin. Lab. Sci. 36:371–386 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Indrigo J., Hunter R.L., Jr., Actor J.K. 2002. Influence of trehalose 6,6′-dimycolate (TDM) during mycobacterial infection of bone marrow macrophages. Microbiology. 148:1991–1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo E.K. 2008. Mycobacterial interaction with innate receptors: TLRs, C-type lectins, and NLRs. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 21:279–286 10.1097/QCO.0b013e3282f88b5d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang P.B., Azad A.K., Torrelles J.B., Kaufman T.M., Beharka A., Tibesar E., DesJardin L.E., Schlesinger L.S. 2005. The human macrophage mannose receptor directs Mycobacterium tuberculosis lipoarabinomannan-mediated phagosome biogenesis. J. Exp. Med. 202:987–999 10.1084/jem.20051239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto M., Tanaka T., Kaisho T., Sanjo H., Copeland N.G., Gilbert D.J., Jenkins N.A., Akira S. 1999. A novel LPS-inducible C-type lectin is a transcriptional target of NF-IL6 in macrophages. J. Immunol. 163:5039–5048 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsunaga I., Naka T., Talekar R.S., McConnell M.J., Katoh K., Nakao H., Otsuka A., Behar S.M., Yano I., Moody D.B., Sugita M. 2008. Mycolyltransferase-mediated glycolipid exchange in Mycobacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 283:28835–28841 10.1074/jbc.M805776200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moody D.B., Reinhold B.B., Guy M.R., Beckman E.M., Frederique D.E., Furlong S.T., Ye S., Reinhold V.N., Sieling P.A., Modlin R.L., et al. 1997. Structural requirements for glycolipid antigen recognition by CD1b-restricted T cells. Science. 278:283–286 10.1126/science.278.5336.283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita Y.S., Velasquez R., Taig E., Waller R.F., Patterson J.H., Tull D., Williams S.J., Billman-Jacobe H., McConville M.J. 2005. Compartmentalization of lipid biosynthesis in mycobacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 280:21645–21652 10.1074/jbc.M414181200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita Y.S., Sena C.B., Waller R.F., Kurokawa K., Sernee M.F., Nakatani F., Haites R.E., Billman-Jacobe H., McConville M.J., Maeda Y., Kinoshita T. 2006. PimE is a polyprenol-phosphate-mannose-dependent mannosyltransferase that transfers the fifth mannose of phosphatidylinositol mannoside in mycobacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 281:25143–25155 10.1074/jbc.M604214200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noll H., Bloch H., Asselineau J., Lederer E. 1956. The chemical structure of the cord factor of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 20:299–309 10.1016/0006-3002(56)90289-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Numata F., Nishimura K., Ishida H., Ukei S., Tone Y., Ishihara C., Saiki I., Sekikawa I., Azuma I. 1985. Lethal and adjuvant activities of cord factor (trehalose-6,6′-dimycolate) and synthetic analogs in mice. Chem. Pharm. Bull. (Tokyo). 33:4544–4555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno H., Ono S., Hirayama N., Shimada S., Saito T. 1994. Preferential usage of the Fc receptor γ chain in the T cell antigen receptor complex by γ/δ T cells localized in epithelia. J. Exp. Med. 179:365–369 10.1084/jem.179.1.365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otsuka A., Matsunaga I., Komori T., Tomita K., Toda Y., Manabe T., Miyachi Y., Sugita M. 2008. Trehalose dimycolate elicits eosinophilic skin hypersensitivity in mycobacteria-infected guinea pigs. J. Immunol. 181:8528–8533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozeki Y., Tsutsui H., Kawada N., Suzuki H., Kataoka M., Kodama T., Yano I., Kaneda K., Kobayashi K. 2006. Macrophage scavenger receptor down-regulates mycobacterial cord factor-induced proinflammatory cytokine production by alveolar and hepatic macrophages. Microb. Pathog. 40:171–176 10.1016/j.micpath.2005.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S.Y., Ueda S., Ohno H., Hamano Y., Tanaka M., Shiratori T., Yamazaki T., Arase H., Arase N., Karasawa A., et al. 1998. Resistance of Fc receptor- deficient mice to fatal glomerulonephritis. J. Clin. Invest. 102:1229–1238 10.1172/JCI3256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao V., Fujiwara N., Porcelli S.A., Glickman M.S. 2005. Mycobacterium tuberculosis controls host innate immune activation through cyclopropane modification of a glycolipid effector molecule. J. Exp. Med. 201:535–543 10.1084/jem.20041668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Retzinger G.S., Meredith S.C., Takayama K., Hunter R.L., Kézdy F.J. 1981. The role of surface in the biological activities of trehalose 6,6′-dimycolate. Surface properties and development of a model system. J. Biol. Chem. 256:8208–8216 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson M.J., Sancho D., Slack E.C., LeibundGut-Landmann S., Reis e Sousa C. 2006. Myeloid C-type lectins in innate immunity. Nat. Immunol. 7:1258–1265 10.1038/ni1417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothfuchs A.G., Bafica A., Feng C.G., Egen J.G., Williams D.L., Brown G.D., Sher A. 2007. Dectin-1 interaction with Mycobacterium tuberculosis leads to enhanced IL-12p40 production by splenic dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 179:3463–3471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K., Yang X.L., Yudate T., Chung J.S., Wu J., Luby-Phelps K., Kimberly R.P., Underhill D., Cruz P.D., Jr., Ariizumi K. 2006. Dectin-2 is a pattern recognition receptor for fungi that couples with the Fc receptor gamma chain to induce innate immune responses. J. Biol. Chem. 281:38854–38866 10.1074/jbc.M606542200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt A. 1997. Malassezia furfur: a fungus belonging to the physiological skin flora and its relevance in skin disorders. Cutis. 59:21–24 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sueoka E., Nishiwaki S., Okabe S., Iida N., Suganuma M., Yano I., Aoki K., Fujiki H. 1995. Activation of protein kinase C by mycobacterial cord factor, trehalose 6-monomycolate, resulting in tumor necrosis factor-alpha release in mouse lung tissues. Jpn. J. Cancer Res. 86:749–755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tailleux L., Schwartz O., Herrmann J.L., Pivert E., Jackson M., Amara A., Legres L., Dreher D., Nicod L.P., Gluckman J.C., et al. 2003. DC-SIGN is the major Mycobacterium tuberculosis receptor on human dendritic cells. J. Exp. Med. 197:121–127 10.1084/jem.20021468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh K.J., Abbott A.N., Hwang S.A., Indrigo J., Armitige L.Y., Blackburn M.R., Hunter R.L., Jr., Actor J.K. 2008. A role for tumour necrosis factor-alpha, complement C5 and interleukin-6 in the initiation and development of the mycobacterial cord factor trehalose 6,6′-dimycolate induced granulomatous response. Microbiology. 154:1813–1824 10.1099/mic.0.2008/016923-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werninghaus K., Babiak A., Gross O., Hölscher C., Dietrich H., Agger E.M., Mages J., Mocsai A., Schoenen H., Finger K., et al. 2009. Adjuvanticity of a synthetic cord factor analogue for subunit Mycobacterium tuberculosis vaccination requires FcRγ-Syk-Card9–dependent innate immune activation. J. Exp. Med. 206:89–97 10.1084/jem.20081445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winthrop K.L. 2006. Risk and prevention of tuberculosis and other serious opportunistic infections associated with the inhibition of tumor necrosis factor. Nat. Clin. Pract. Rheumatol. 2:602–610 10.1038/ncprheum0336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav M., Schorey J.S. 2006. The beta-glucan receptor dectin-1 functions together with TLR2 to mediate macrophage activation by mycobacteria. Blood. 108:3168–3175 10.1182/blood-2006-05-024406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi M., Ogawa Y., Endo K., Takeuchi H., Yasaka S., Nakamura S., Yamamura Y. 1955. Experimental formation of tuberculous cavity in rabbit lung. IV. Cavity formation by paraffine oil extract prepared from heat killed tubercle bacilli. Kekkaku. 30:521–524 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamasaki S., Ishikawa E., Sakuma M., Hara H., Ogata K., Saito T. 2008. Mincle is an ITAM-coupled activating receptor that senses damaged cells. Nat. Immunol. 9:1179–1188 10.1038/ni.1651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamasaki S., Matsumoto M., Takeuchi O., Matsuzawa T., Ishikawa E., Sakuma M., Tateno H., Uno J., Hirabayashi J., Mikami Y., et al. 2009. C-type lectin Mincle is an activating receptor for pathogenic fungus, Malassezia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 106:1897–1902 10.1073/pnas.0805177106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]