Abstract

Diffuse optical imaging is a non-invasive technique that uses near-infrared light to measure changes in brain activity through an array of sensors placed on the surface of the head. Compared to functional MRI, optical imaging has the advantage of being portable while offering the ability to record functional changes in both oxy- and deoxy-hemoglobin within the brain at a high temporal resolution. However, the reconstruction of accurate spatial images of brain activity from optical measurements represents an ill-posed and underdetermined problem that requires regularization. These reconstructions benefit from incorporating prior information about the underlying spatial structure and function of the brain. In this work, we describe a novel image reconstruction approach which uses surface-based wavelets derived from structural MRI to incorporate high-resolution anatomical and structural prior information about the brain. This surface-based approach is used to approximate brain activation patterns through the reconstruction and presentation of topographical (two-dimensional) maps of brain activation directly onto the folded surface of the cortex. The set of wavelet coefficients is directly estimated by a truncated singular-value decomposition based pseudo-inversion of the wavelet projection of the optical forward model. We use a reconstruction metric based on Shannon entropy which quantifies the sparse loading of the wavelet coefficients and is used to determine the optimal truncation and regularization of this inverse model. In this work, examples of the performance of this model are illustrated for several cases of numerical simulation and experimental data with comparison to functional magnetic resonance imaging.

1. Introduction

Diffuse optical imaging is a non-invasive technique for recording functional brain activity that uses near-infrared light directed into the head from lasers and sensors placed on the surface of the scalp. Over the past few decades, optical imaging has gained interest from the brain imaging community as a complimentary approach to functional MRI (fMRI). In particular, compared to fMRI, optical imaging is less costly, is more portable and can offer an opportunity to study the brain in a wider variety of experimental scenarios since measurements can be recorded without a dedicated room or facility. In addition, optical imaging has the ability to resolve changes in both oxy- and deoxy-hemoglobin within the brain using multiple wavelengths of light.

By organizing optical sensors into a spatially distributed array on the surface of the head, differing regions of the underlying brain can be sampled and then reconstructed into an image of functional activity. However, reconstruction of images from diffuse optical measurements represents an ill-posed and generally underdetermined linear inverse problem (reviewed in Arridge (1999)). Therefore, the accurate reconstruction of spatial images from optical measurements is considerably more difficult and is generally intrinsically lower spatial resolution in comparison to functional MRI. Typically, only a limited number of optical measurements may be experimentally recorded due to the exponential decay of signal intensity as the distance between a light emitter and detector pair increases. This decay limits the separation distance between an optical source and detector pair to around 1–4 cm and results in a depth of penetration of optical signals to only the outer 5–8 mm of the actual brain for typical 3 cm optode spacing (Fukui et al 2003). This also physically limits the number of sensors that can be placed on the surface of the head and restricts the simultaneous number of measurement pair combinations given the typical dynamic range limitations of common photon detectors. Generally, optical imaging is therefore an underdetermined problem where there are more unknown parameters in the volume (brain) than measurements that can be made from the surface of the head. Since each of these optical measurements reflects the integration of the absorption changes along the diffuse path between a source and detector pair, the reconstruction of independent absorption values for each individual point along this path is thereby ill-posed and no single unique solution can be obtained. In part, the measurement of overlapping source and detector combinations using tomographic probe geometries can help to improve the conditioning of this problem (Boas et al 2004) by providing more uniform spatial sensitivity compared to nearest-neighbor only measurement geometries; however, image reconstruction remains ill-posed. Improvements in reconstruction techniques for optical imaging have been offered by a number of groups over recent years (as reviewed by Gibson et al (2005)). In particular, major advances have been made by the incorporation of structural information from anatomical MRI or x-ray tomography that have led to improvements in the estimation of the sensitivity of optical measurements to underlying changes in the brain—termed the optical forward model. To date, several groups have introduced Monte Carlo or finite-element models for the computation of the optical forward model using subject anatomical information to aid in modeling the diffusion of light through realistically complicated tissue structures (Fukui et al 2003, Okada and Delpy 2003, Wang et al 1995, Boas et al 2002, Dehghani et al 2003). These models have led to improvements in the estimation of more precise path length and partial volume corrections for the optical forward model and therefore have provided a more accurate model for analysis and image reconstruction. In addition to the use of structural information in the forward problem, anatomical information has also been introduced into the optical inverse problem—the calculation of an image by inversion of the optical measurement model (Li et al 2005, Intes et al 2004, Pogue et al 1998, Guven et al 2005). For example, anatomical information has been used to restrict the location of non-zero components of the reconstructed image to the brain (cortical-constraint) by masking the superficial layers of the head as a hard constraint (Boas and Dale 2005). Alternatively, structural information has been incorporated as a soft prior to the inverse problem through the use of spatially distributed weighting to bias the reconstruction to the expected regions (Guven et al 2005, Li et al 2005, Yalavarthy et al 2007). However, in general, the mismatch between anatomical and functional spatial resolutions creates a dilemma. Namely, functional neuroimaging data are often obtained at a lower spatial resolution than the resolution of available structural information. In optical imaging, the incorporation of high-resolution anatomical information from MRI into the lower resolution optical inverse model requires that the anatomical mask be down-sampled (resulting in loss of information from the anatomy image) or that the optical image be reconstructed at an artificially high resolution (resulting in a more under-determined model). For instance, structural MRI is often sampled at around a 1–1.5 mm isotropic resolution. However, optical image reconstructions that use this information as a mask or prior require resampling to much lower resolutions (around 5–10 mm or higher). Even for the case of typical functional MRI data (usually sampled at 2–3 mm voxel sizes), we generally know the anatomical boundaries of the brain at an even higher resolution. Adding to this, spatial smoothing kernels as typically used in fMRI can introduce boundary effects at the edges of a mask and can blur proximal regions together (e.g. by smoothing information across distinct brain regions, such as gray/white matter borders or across proximal gyri).

The wavelet transform is an operator capable of representing an image at multiple levels of spatial resolution. This makes it possible to capture both low- and high-resolution spatial features of the image. Wavelets capture the localized spatial frequencies of an image as compared with the Fourier transform which supplies only the global frequency information. This allows wavelets to efficiently represent spatially correlated images, such as the brain activity images typically observed in functional MRI. For this reason, wavelets have been widely used for data and image compression applications. In addition to their use in representing images (or textures), wavelet representations can be used to model the actual physical structure of objects in three dimensions and can be used to approximate the structure of complex objects such as the topographical surface of the brain. Previously, such wavelets have been used by Yu et al to approximate the coordinates of the surface of the brain and to investigate differences in neuroanatomical shapes as they vary with age (Yu et al 2007). Similarly, surface wavelets have also been used by Nain et al (2007) for the purpose of shape representation and segmentation of brain structures. These approaches can be used to represent the actual structure of the brain over several spatial scales from coarse to fine resolution.

The motivation of our current work was to utilize a wavelet representation similar to that presented by Yu et al (2007) to model the anatomical structure of the brain and to use this as the basis for the reconstruction of an image of functional changes on the surface based on diffuse optical imaging data. This approach allows us to model the magnitude of the estimated brain activity signal as an image (texture) on this anatomical structure by reparameterizing the optical inverse problem. For this work, we derive a set of surface-based spherical wavelets (Schröder and Sweldens 1995b) from an extracted high-resolution (~500 μm2) surface mesh of a brain obtained by segmentation. These wavelets are used as a prior informing the model of the structure of the brain. We used this wavelet basis to reparameterize the underlying image of oxy- and deoxy-hemoglobin changes, allowing the direct estimation of the wavelet weights (coefficients) by regularized linear inversion.

The wavelet based method that we have proposed approximates brain activity by specifically restricting the reconstruction of brain activity to the two-dimensional, folded, surface of the brain by imposing a cortical surface constraint. The introduction of the cortical surface constraint for diffuse optical reconstructions of brain activity is motivated by the observation that the structural anatomy of the brain is organized into two-dimensional layers, with the majority of functionally related neuronal activity concentrated within the first five layers of the brain defined as the cortex (Squire 2008). The cortex of the human brain is specifically the region within 2–4 mm of its surface. As reviewed in Logothetis (2003) this region is where the majority of neural activity related to the performance of tasks occurs as revealed by histology, electrophysiological studies of the brain, and more recently, functional MRI (Harel et al 2006, Ress et al 2007, Jin and Kim 2008a, 2008b, Zhao et al 2006). Recently, this has been confirmed by high-resolution, high-field functional MRI which has revealed that most of the microvascular BOLD (blood oxygen level-dependent) signal is localized to cortical layer IV after masking the larger pial surface veins (Jin and Kim 2008a). A similar assumption of surface-based activations has been previously introduced for regularizing the reconstruction of dipole sources in electroencephalography (EEG) and magnetoencephalography (MEG, Darvas et al 2004) and recently fMRI (Operto et al 2006, 2008, Grova et al 2006) through constraint to the layer IV surface.

Based on this assumption, in this work, we show that reconstructing the optical image directly in the wavelet domain, coupled with prior knowledge of the brain’s anatomy leads to improved image reconstruction. We demonstrate this approach with both numerical simulations and experimental results.

2. Theory

2.1. Diffuse optical brain imaging

Diffuse optical imaging is a non-invasive method used to measure functional brain signals (Jöbsis 1977, Wray et al 1988, Delpy et al 1988). Near-infrared recordings offer both high temporal resolution and sensitivity to oxy- and deoxygenated hemoglobin. However, the reconstruction of accurate images from optical measurements is a difficult inverse problem. A thorough and comprehensive discussion of the theory of optical imaging and its difficulties can be found in the review by Arridge (1999). In this section, we briefly cover some of the theory underlying optical imaging.

In optical imaging, low levels of light (typically 5–10 mW) are directed into the head from a series of light emitters (or source optodes) positions on the scalp. Often this light is coupled from a laser source to the head via fiber optics or by light emitting diodes placed directly on the skin. Similarly, detectors are positioned at distances away from the sources. Light enters the head and diffuses through the tissue since biological tissue is highly scattering. Optical instruments use light within the wavelength region of 650–850 nm, referred to as the ‘near-infrared window’, because at these wavelengths the absorption of tissue is low and light can diffuse centimeters into the tissue. This optical window allows light to penetrate deep enough to sample approximately 5–10 mm of the outermost cortex of the brain (Fukui et al 2003).

The diffuse path traversed by light from a source to a detector position defines the sensitivity of this optical measurement pair to changes in absorption and scattering in the underlying tissue. This is referred to as the optical forward model. The amount of light at a particular wavelength which reaches a detector is reported as optical density (OD) and defined as

| (1) |

where Iλ is the intensity of light exiting the tissue, is the intensity of light sent into the tissue, νλ is the noise error, and i, j refers to a particular source-i and detector-j pair. In most functional optical imaging brain studies light absorption changes ΔOD (rather than absolute optical density) are used since the absolute values of I and require calibration. In contrast, when only changes in the signal from baseline are considered, these factors are removed by normalization. In this case, ΔOD is given as

where 〈Iλ〉 is the mean intensity of the signal at wavelength λ over the baseline period and νλ is the noise error. This normalization removes the need to calibrate the lasers, fiber coupling, detector efficiencies, etc. An assumption that is often made for brain studies is that changes in the absorption of tissue during brain activity are small such that the path of the light (and thus the sensitivity of a measurement pair) is unchanged. This allows a linear approximation to be made and provides the basic equation for optical sensing

| (2) |

Here, is a matrix that describes the sensitivity of a particular measurement pair (i, j) to changes in absorption in the underlying tissue. This is a summation of these underlying changes within the volume into value recorded by the sensor pair. is the change in the absorption coefficient μa at a given wavelength λ, and νλ is the noise error.

During functional brain activation, increases in blood flow, volume and oxygenation result in changes in absorption due to underlying changes in the concentration of oxy- and deoxy-hemoglobin, HbO2 and HbR, respectively. This physiological response changes the absorption properties of the brain. For continuous wave optical systems (such as those used in this study), the effect of potential scattering changes during brain activity can often be ignored. The change in the concentration of the two primary absorbers that change during functional activity, Δ[HbO2] and Δ[HbR], can be related to changes in optical density at multiple wavelengths by the Beer–Lambert expression (Cope et al 1988)

| (3) |

where is the extinction coefficient for a given wavelength for each hemoglobin species at wavelength λ. Optical measurements are made at two or more distinct wavelengths to allow separation of Δ[HbO2] and Δ[HbR]. The overall optical forward model with the hemoglobin spectral priors can be written in the form

| (4) |

We identify the following quantities for y, H and β:

| (5) |

and

| (6) |

and where ν is the noise error. To summarize, equation (4) is the optical imaging forward model and describes the linear relationship between changes in the concentration of HbO2 and HbR in the tissue and the change in optical density recorded at the surface between a set of optical source and detectors. It is this equation which must be inverted in order to reconstruct an image (volume) of the hemodynamic changes in the brain. As aforementioned, the inversion of the optical forward model requires regularization. We will now introduce the theory of surface-derived wavelets before returning to the inverse problem in section 2.4.

2.2. Surface-derived wavelets

Wavelets have attracted attention as a signal or image expansion basis due to their localized resolution in both time/space and frequency. One of the advantages of wavelets is their ability to represent data at multiple resolution levels, making it possible to capture coarse or smooth features of an image (corresponding to low frequency), along with detailed features such as edges and textures (corresponding to higher frequency). In general, discrete wavelet transforms (wavelets based on digital filterbanks) (Daubechies 1992) are generated as a linear combination of translated and scaled versions of a function φ(2j x) (called ‘scaling function’), and its integer shifts, where j is the resolution level at which an image is expanded. Typically, an image is expanded over a range of resolution levels. Such property allows for expanding an image or a signal at multiple resolutions in a fast and efficient way starting with the input data resolution as the highest level of resolution. In this sense, wavelets when used as a spatial basis to support the reconstruction of images (e.g. Zhu et al (1997)) provide an effective means to model objects of various spatial resolutions. For a detailed discussion of wavelets theory and filterbanks the reader is referred to Daubechies (1992).

Surface-based wavelets have been introduced by Schröder and Sweldens (1995a, 1995b), where wavelets were defined from a multiresolution mesh obtained via recursive subdivision of an icosahedron approximating a sphere, as demonstrated in figure 1. The mesh is created by repeatedly subdividing an initial mesh such that each triangle (consult figure 1) resolves into four ‘child’ triangles at each new subdivision level. This is accomplished by defining a midpoint at each edge, followed by connecting the new midpoints together, leading to a higher resolution mesh. The surface wavelet used in this work is defined on the resulting multiresolution mesh.

Figure 1.

Surface mesh at various resolutions obtained via recursive subdivision of an icosahedron approximating a sphere. Meshes shown at resolution levels J = 1, J = 2 and J = 3.

Such wavelets are well suited for describing functions defined on manifolds. Spherical wavelets maintain the multiresolution property of more traditional wavelets, but no longer rely on the conventional translation and dilation of the scaling function in order to obtain lower resolution wavelets. If we define a sequence of spaces  ⊂ L2, then we have

⊂ L2, then we have

| (7) |

The space  may be viewed as a mesh at a given resolution level, where a higher index j corresponds to a higher resolution mesh. Thus, a space

may be viewed as a mesh at a given resolution level, where a higher index j corresponds to a higher resolution mesh. Thus, a space  is a subset of

is a subset of  . Equation (7) indicates that the set of scaling functions {φj,k} (kth scaling function at resolution level j) spanning the space

. Equation (7) indicates that the set of scaling functions {φj,k} (kth scaling function at resolution level j) spanning the space  can be obtained as a linear combination of higher resolution scaling functions φj+1,k. Define

can be obtained as a linear combination of higher resolution scaling functions φj+1,k. Define  as the set of all indices k of the scaling function φj,k at resolution level j. The set

as the set of all indices k of the scaling function φj,k at resolution level j. The set  is equipped with the telescopic property such that

is equipped with the telescopic property such that  is a subset of

is a subset of  . The set

. The set  may be viewed as a general index describing the vertices of the scaling function φj,k at subdivision level j. The scaling function φ is chosen to be interpolating, so that at a given vertex vj,k′ at resolution level j we have

may be viewed as a general index describing the vertices of the scaling function φj,k at subdivision level j. The scaling function φ is chosen to be interpolating, so that at a given vertex vj,k′ at resolution level j we have

A new set of vertices ℳ(j) is then obtained by adding vertices at the midpoints of edges and connecting them with geodesics (curves whose tangent vectors remain parallel if they are transported along it). A complete set of vertices at level j + 1 is given by  , the union of the sets

, the union of the sets  and ℳ(j) (telescopic property of

and ℳ(j) (telescopic property of  ). The interpolation process is depicted in figure 1, where for example given a set of vertices at locations

). The interpolation process is depicted in figure 1, where for example given a set of vertices at locations  (vertices at resolution level j = 1), the higher resolution set

(vertices at resolution level j = 1), the higher resolution set  is obtained by adding new vertices ℳ(1) to the set

is obtained by adding new vertices ℳ(1) to the set  . After N subdivisions, the total number of vertices is 10× 4N +2. Due to the interpolating property of the biorthogonal scaling function φj,k, the corresponding scaling function coefficients λj,k of a function f ∈

. After N subdivisions, the total number of vertices is 10× 4N +2. Due to the interpolating property of the biorthogonal scaling function φj,k, the corresponding scaling function coefficients λj,k of a function f ∈  interpolated at level j icosahedron are simply the values of f at each vertex, or

interpolated at level j icosahedron are simply the values of f at each vertex, or

Define A(j, m), B(j, m) and C(j, m) as the local neighbors of a vertex vj+1,m. Then following (Schröder and Sweldens 1995b), a subdivision scheme is used to obtain the scaling function coefficients λj+1,m:

| (8) |

This is schematically depicted in figure 2.

Figure 2.

Nonseparable filter generating wavelet basis. The local neighborhoods A(j, k), B(j, k) and C(j, k) are subsets of wavelet vertices in  . Their values are used to determine the new coefficient λj+1,m. Also see equation (8).

. Their values are used to determine the new coefficient λj+1,m. Also see equation (8).

The wavelet functions ψj,m are obtained using a lifting algorithm, starting with the scaling function φj,m:

with sj,k,m = Ij+1,m/Ij,k and Ij,k = ∫ φj,k dω, where dω is the area measure of a sphere. This ensures that the wavelet has at least one vanishing moment. Note that while the surface wavelet ψj,m defined on mesh is found as a linear combination of the scaling function, the coefficients sj,k,m vary with the resolution level and are not given by a filter whose coefficients remain constant across the scales. This is the main difference between the classical wavelet and the surface wavelet introduced by Schröder and Sweldens in 1995b. Now we can express a function f ∈ L2 defined on a sphere  in terms of the resulting wavelets and the coarsest scaling function:

in terms of the resulting wavelets and the coarsest scaling function:

| (9) |

where {λ0,k} is the set of scaling function coefficients representing the localized lowpass (smooth) contents of the image, whereas wavelet coefficients γj,m reflect the localized bandpass and highpass frequency features, or details, of the image. The wavelet coefficients of an image are found in two steps recursively. Step 1 consists of finding γj,m for all indices m in the set ℳ(j) (∀ m ∈ ℳ(j)), and is given by

Step 2 yields λj,k given γj,m from Step 1:

| (10) |

| (11) |

In other words, a decomposition step goes from the j + 1 level set of wavelet coefficients {λj+1,l} to the coefficients sets {λj,k} and {γj,k}. The inverse transform (image reconstruction) is similarly obtained in two steps recursively for all indices m in the set ℳ(j). In step 1 the finer resolution coefficient λj+1,k

| (12) |

| (13) |

For reconstruction step 2, λj+1,m is obtained using λj+1,k from step 1:

Thus, a reconstruction step is the reverse of decomposition, where the higher resolution set of coefficients {λj+1,l} is obtained from lower resolution coefficient sets {λj,k} and {γj,k}. For detailed discussion of the decomposition and reconstruction steps consult Schröder and Sweldens (1995b, 1995a).

Note that while strictly speaking the spherical wavelets used in this paper are not orthogonal, it is shown in Yu et al (2007) that the wavelets and their scaled versions in fact approximate orthogonality. This is a useful property since it leads to wavelet which are nearly orthogonal to each other and approximately uncorrelated. In this paper, we implement the forward and inverse wavelet transforms as matrices  and

and  respectively, such that a function f ∈ L2 and its wavelet transform

respectively, such that a function f ∈ L2 and its wavelet transform  are related as in

are related as in  . Conversely, f is recovered from

. Conversely, f is recovered from  via the inverse transform matrix,

via the inverse transform matrix,  , with

, with  .

.

2.3. Wavelet transform of the optical forward model

Returning to the subject of brain optical topography, the optical forward model (described in equation (4)) is the product of a nonsquare sensitivity matrix H and the vector of unknowns β. H sums the absorption changes from points in the tissue to project the optical density change measured at the surface. Typically, this is a problem where the number of measurements (from a surface) is vastly smaller than the number of unknowns (within a volume). We will calculate β (see equation (4)) by first reparameterizing the model using the wavelet transform and then estimating the coefficients  of the wavelet transform of β, given by

of the wavelet transform of β, given by

| (14) |

Rather than directly attempting to estimate the unknowns Δ[HbO2] and Δ[HbR] in β, we first evaluate their respective surface wavelet transforms through this substitution and estimate the resulting wavelet coefficients directly from the inversion of the resulting matrix equation. More specifically, the transform coefficients of the oxy- and deoxy-hemoglobin concentration changes, respectively and , are given by

Writing the oxy- and deoxy-hemoglobin concentration changes in terms of their respective wavelet transforms we obtain

| (15) |

| (16) |

Substituting equations (15) and (16) into equation (6) we have

| (17) |

The inverse transform matrix  can be absorbed into matrix H in equation (5), leading to the equation

can be absorbed into matrix H in equation (5), leading to the equation

| (18) |

where we have

| (19) |

and

| (20) |

We note that the property of near orthogonality of the spherical wavelet described in section 2.2 (as described in Yu et al (2007)) means that the statistical properties of noise remain essentially unchanged in wavelet domain. The motivation for this transformation, which will be further elaborated in the following section, is that the coefficients that we are now trying to estimate ( ) have novel known characteristics. Namely, we have additional prior knowledge based on the general properties of wavelets that the vector of unknowns

) have novel known characteristics. Namely, we have additional prior knowledge based on the general properties of wavelets that the vector of unknowns  will be expected to be a sparse vector with only a small percentage of its coefficients significantly different from zero. This property will be the basis for our regularization criterion and will be further elaborated in section 2.5.

will be expected to be a sparse vector with only a small percentage of its coefficients significantly different from zero. This property will be the basis for our regularization criterion and will be further elaborated in section 2.5.

In addition, while we still have an ill-posed problem of finding the vector β (or equivalently  ), the multiresolution property of wavelets (the ability to reconstruct the transformed function at various levels of resolution) provides a tradeoff between degrees-of-freedom and spatial smoothness of the resulting image. A restricted lower resolution representation of the image (β) can be obtained by removing levels (rows) from the wavelet matrix (

), the multiresolution property of wavelets (the ability to reconstruct the transformed function at various levels of resolution) provides a tradeoff between degrees-of-freedom and spatial smoothness of the resulting image. A restricted lower resolution representation of the image (β) can be obtained by removing levels (rows) from the wavelet matrix ( ) to create a non-square matrix operator (

) to create a non-square matrix operator ( , wavelet transform matrix with J levels of resolution). Thus, the wavelet transform matrix can be used as a smoothing kernel allowing for a tradeoff between spatial resolution and degrees-of-freedom in the model. Note that unlike smoothing kernel in three dimensions, smoothing by the wavelet kernel is specifically on the surface of the brain, which means that it follows the contours of the brain rather than leaping between proximal gyri. This is in contrast to a traditional smoothing kernel as used in fMRI. When resolution levels are removed from the wavelet matrix, the resulting smoothing kernel is no longer a square matrix. Thus, the mathematical condition of perfect reconstruction (image information fully preserved in wavelet domain) using the wavelets is theoretically only possible when all levels of the inverse wavelet transform matrix are included and only in the case (

, wavelet transform matrix with J levels of resolution). Thus, the wavelet transform matrix can be used as a smoothing kernel allowing for a tradeoff between spatial resolution and degrees-of-freedom in the model. Note that unlike smoothing kernel in three dimensions, smoothing by the wavelet kernel is specifically on the surface of the brain, which means that it follows the contours of the brain rather than leaping between proximal gyri. This is in contrast to a traditional smoothing kernel as used in fMRI. When resolution levels are removed from the wavelet matrix, the resulting smoothing kernel is no longer a square matrix. Thus, the mathematical condition of perfect reconstruction (image information fully preserved in wavelet domain) using the wavelets is theoretically only possible when all levels of the inverse wavelet transform matrix are included and only in the case ( ) is a square matrix.

) is a square matrix.

2.4. Inversion procedure for the wavelet model

In equation (4), the image reconstruction process is described as a problem of estimating an optimal solution (in some sense) of an underdetermined system of linear equations (more unknowns than variables), an ill-posed problem. The inversion of the non-square matrix  can be approximated using a singular value decomposition (SVD, Ribes and Schmitt 2008). The SVD of a matrix

can be approximated using a singular value decomposition (SVD, Ribes and Schmitt 2008). The SVD of a matrix  (or H) is given by

(or H) is given by

| (21) |

where U and V are matrices with orthonormal columns, and Σ is a diagonal matrix containing the singular values in nonincreasing order. The SVD decomposition makes it possible to estimate a stable pseudoinverse matrix using a subset of the singular values. The pseudoinverse matrix is found from

| (22) |

for some N0 ≤ Ns where U = (u1, u2, …, uNs), V = (v1, v2, …, vNs), and Σ = diag (σ1, σ2, …, σNs), with σ1 ≥ σ2 ≥ … ≥ σNs. Ns is the total number of singular values representing the original data and N0 is the reduced number of components used in the approximation. In our model, we use SVD decomposition for the purpose of estimating the (regularized) pseudoinverse matrix

of matrix  of equation (19).

of equation (19).

Having found the pseudoinverse

with the appropriate N0 determined from sparsity criterion (as will be discussed in section 2.5), the wavelet coefficients  (and therefore Δ[HbO2] and Δ[HbR]) are computed from the inverse wavelet transform of

(and therefore Δ[HbO2] and Δ[HbR]) are computed from the inverse wavelet transform of  , given by

, given by  .

.

2.5. Sparsity criterion

The substitution of the wavelet transform expression into the optical forward model to produce equation (18) allows us to directly solve for the wavelet coefficients and then use these to calculate Δ[HbO2] and Δ[HbR] by equations (15) and (16), respectively. This substitution offers several advantages over direct estimation of Δ[HbO2] and Δ[HbR] in β. In particular, we will define a metric to evaluate the optimal regularization of the truncated SVD model in equation (22) based on a property of wavelet coefficients known as sparsity.

We define a vector of unknowns  as a sparse vector when only a small percentage of its coefficients significantly differs from zero. This feature means that most of the wavelet coefficients are negligibly small, which makes wavelet representations useful for both compression and denoising of images. Figure 3 depicts the value and population density of the wavelet representation of an arbitrary example of a surface image that demonstrates this property. Here, as an example, we have used equation (14) to take the wavelet transform of an image of an atlas-based segmentation of a brain showing labels of various functional regions obtained using the FreeSurfer program (described in Fischl et al (1999)). The wavelet transform of this arbitrary image demonstrates the general property of sparsity. In figure 3(A), the value of these wavelet coefficients are plotted in ascending order. The distribution of wavelet coefficients can be represented as a heavy-tailed function or as a sum of two Gaussian distributions representing the population of ‘non-zero’ and ‘near-zero’ coefficients as shown in figure 3(B). As demonstrated in this figure, the majority of these wavelet coefficients are very close to zero. In fact, the basis of wavelet compression techniques is to truncate these low values to zero allowing the image to be approximated as a sparse data set requiring less memory for storage. Since sparsity relates how efficiently an image can be modeled via wavelets, various metrics to define sparsity have previously been introduced as a way of quantifying wavelet encoding as discussed in Hurley and Rickard (2008). In addition, since wavelets are an efficient means to model images with various scales of spatial coherence, sparsity metrics have also been used to characterize the amount of spatial coherence and compare images. For example, natural images will have a larger sparsity metric compared to an image of random noise (Field 1999).

as a sparse vector when only a small percentage of its coefficients significantly differs from zero. This feature means that most of the wavelet coefficients are negligibly small, which makes wavelet representations useful for both compression and denoising of images. Figure 3 depicts the value and population density of the wavelet representation of an arbitrary example of a surface image that demonstrates this property. Here, as an example, we have used equation (14) to take the wavelet transform of an image of an atlas-based segmentation of a brain showing labels of various functional regions obtained using the FreeSurfer program (described in Fischl et al (1999)). The wavelet transform of this arbitrary image demonstrates the general property of sparsity. In figure 3(A), the value of these wavelet coefficients are plotted in ascending order. The distribution of wavelet coefficients can be represented as a heavy-tailed function or as a sum of two Gaussian distributions representing the population of ‘non-zero’ and ‘near-zero’ coefficients as shown in figure 3(B). As demonstrated in this figure, the majority of these wavelet coefficients are very close to zero. In fact, the basis of wavelet compression techniques is to truncate these low values to zero allowing the image to be approximated as a sparse data set requiring less memory for storage. Since sparsity relates how efficiently an image can be modeled via wavelets, various metrics to define sparsity have previously been introduced as a way of quantifying wavelet encoding as discussed in Hurley and Rickard (2008). In addition, since wavelets are an efficient means to model images with various scales of spatial coherence, sparsity metrics have also been used to characterize the amount of spatial coherence and compare images. For example, natural images will have a larger sparsity metric compared to an image of random noise (Field 1999).

Figure 3.

Sparsity of wavelet representation: panel (A) shows the ordered coefficients resulting from the wavelet transform of the cortex. Panel (B) shows the corresponding heavy-tailed histogram of the coefficients, reflecting the near-zero and the non-zero wavelet coefficients. The significant near-zero population reflects the sparsity of wavelet representation.

In section 2.4, we discussed SVD matrix decomposition as a tool (along with wavelets in section 2.2) for regularizing ill-posed problems and in equation (22) we defined the truncated SVD inversion of the optical imaging model using the first N0 singular values. To this end, we use measures of sparsity as a metric for choosing the appropriate number of singular values N0. Our sparsity measure is based on works by Burg (1978) and Ables (1974), where the information-quantifying criterion is referred to as maximum entropy method (MEM). In Skillingand Bryan (1984), it is suggested that MEM provides a consistent and robust technique of image estimation starting with incomplete data. MEM as a sparsity measure for image reconstruction is further discussed in Starck et al (1998). The reader is referred to Rao and Kreutz-Delgado (1999) for a discussion of finding the best basis selection of an underdetermined system of equations using sparsity measure as an indicator for optimal solution. One interpretation of this approach is that sparsity is used to select underlying set of parameters that represent the most natural image obtained from the ill-posed inversion.

In our work we consider the Shannon diversity measure ℋ, as described in Hurley and Rickard (2008), of an estimated set of coefficients β̂ of length Nβ at a given number N0 of singular values:

| (23) |

As described in Hurley and Rickard (2008), this equation describes a modified version of the Shannon diversity measure mℋ. Hurley described normalizing equation (23) to the norm of matrix β whose columns consist of the measurements of the vector β for all values of N0 from 1 to Ns. As more components are included in the truncated SVD inversion, the information in the resulting image increases. Typically, if one is to construct a curve of ℋ versus N0, the diversity of the image initially increases but then levels to a near constant value matching the information content of the data. That is, once a specific number of singular values have been included in the inverse model, the information in the image negligibly increases with the addition of higher components of the SVD. Since the reconstruction of optical images is under-determined, we will seek the solution for which the image has the most information modeled by the least number of eigenvalues. In light of this, we proposed the further modified Shannon diversity metric by progressively penalizing for the usage of the available degrees of freedom N0, as given in equation (24):

| (24) |

where β is a matrix whose columns contain β̂ obtained at various values of N0. The diversity measure mℋ is evaluated for all values of N0 up to Ns, the total number of singular values . The Shannon diversity measure and its modified version can be viewed as measures of the amount of nonredundant information in a signal, in our case the pseudoinverse of the nonsquare matrix found via SVD. By choosing to reconstruct an image using the inverse model corresponding to a peak in the Shannon diversity curve, we are presenting a reconstruction that represents to some extent an optimal balance between the regularization imposed by the truncated SVD method and the information content of the resulting image.

3. Methods

An overview of the processing stream used to construct the surface-wavelet model is given in figure 4. In this section, we will describe the methodology for each of the major steps in this operation. A summary of the variables and definitions used in our model is given in table 1.

Figure 4.

A schematic depiction of the steps involved in the construction of the surface wavelets and reconstruction of optical tomography images is shown above. The individual components of this analysis scheme are each described in the sections of the text.

Table 1.

Summary of the variables and definitions used in this text.

| Parameter or variable | Role |

|---|---|

| Optical imaging | |

| OD | optical density |

| λ | wavelength |

| I | light intensity |

| sensitivity matrix | |

| μa | absorption coefficient |

| ε | extinction coefficient |

| HbO2 | oxyhemoglobin |

| HbR | deoxyhemoglobin |

| H | sensitivity matrix |

| β | vector of HbO2 and HbR images |

| Wavelet transform | |

| ψj,m | mth wavelet, level j |

| φj,k | kth scaling function at resolution level j |

|

space spanned by φ at j th resolution |

∋ k ∋ k

|

index set of k at level j |

| ℳ(j) ∋ m | index set of m at level j |

| vj,k | kth vertex at level j |

|

wavelet transform matrix |

| λi,j | scaling function coefficient |

| γj,m | wavelet coefficient |

|

wavelet transform of β |

|

wavelet transform of f |

| Sparsity | |

| Ns | total number of singular values |

| nSV | number of singular values chosen for reconstruction |

| ℋ | Shannon diversity measure |

| mℋ | modified Shannon normalized diversity measure |

3.1. Definition of brain surface mesh

The first step in the construction of our model is the extraction of the anatomical surface and the generation of a telescoping series of surface meshes from structural images of the brain. The term telescopic refers to the feature that this series of surface meshes will be generated at differing spatial resolutions with the property that each level of resolution is derived from the mesh immediately below and above it. Using anatomical MRI information (further detailed in section 3.4), a complete surface mesh of the cortex of the brain was constructed using the FreeSurfer segmentation and inflation tools as described in Fischl et al (1999). For this, the T1-weighted structural MRI image is first segmented into CSF (cerebral spinal fluid), gray and white matter layers using the FreeSurfer automated segmentation tool (recon-all). The resulting collection of volumes was manually verified and confirmed to be free of artifacts as described in the manual for FreeSurfer. This segmentation routine generated a tessellated surface of the brain which contained approximately 150 000 node elements and 300 000 face elements (a face defines a set of connections between vertices) for each of the two hemispheres of the brain. Next, the FreeSurfer tools are used to expand this surface generating an inflated surface and finally a fully spherical surface as described in Fischl et al (1999). These transformations were also manually checked and found free of artifacts. As a feature of this transformation, these three surfaces (the brain, the inflated brain and the sphere surface) have equivalent (one-to-one) mapping of vertices and identical face vector variables, although only the brain surface has vertices with physically interpretable real-world (x/y/z) coordinates. As described in Yu et al (2007), because of the equivalence between the sphere and brain surfaces, we performed the remeshing procedure for the basis of our surface wavelets using the sphere surface with a direct analogy to the method of generating the telescoping series described in figure 1. Briefly, as described in (Schröder and Sweldens 1995b), an icosahedral basis was generated for the coarsest meshes using vertices on the sphere. This initial mesh was upsampled using a midpoint interpolation remeshing scheme and the nearest position on the FreeSurfer generated spherical mesh was found. This process was continued until an arbitrarily high resolution mesh was obtained. The left and right hemispheres were remeshed separately. For this work, we generated a total of five mesh levels which contained a total of approximately 30, 100, 450, 1800 and 7000 nodes and 60, 200, 900, 3600 and 14 000 faces for each of the two hemispheres. These five levels represented the brain at a resolution of approximately 290, 110, 40, 15 and 4 mm2, respectively. In our model, the resolution of the largest mesh (4 mm2) is higher then even fMRI data are typically recorded and therefore, we believe this to be more than sufficient for the purpose of optical reconstruction here. The series of telescoping meshes generated by this procedure is shown in figure 5, where a spherical mesh is depicted at increasing resolutions. At each resolution level we show the corresponding inflated brain surface and the true surface. At resolution level 1, a crude version of the original surface image is recovered. As the resolution increases, more details of the brain surface are recovered. At the highest level of the resolution the image is fully recovered.

Figure 5.

Mesh defined on a sphere at various resolution levels, J = 1, …, 5, and corresponding brain reconstruction at a given mesh for both true surface and partially inflated surface. For J = 1 we recover only a crude version of the original image. As J increases we recover more details. With J = 5 the image is fully recovered.

3.2. Calculation of the optical forward model

After segmentation of the anatomical MRI volume as described in section 3.1, a boundary element mesh for the surface of the head, skull, and CSF layers was generated using the MNE (minimum norm estimator) toolkit extension to the FreeSurfer tools (http://www.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu). The vertices from the four nested boundary-element surfaces (skin, skull, CSF and brain mesh obtained at the highest submeshing level) were combined with additional uniformly sampled interior points and tessellated into a volumetric finite element mesh using the TetGen program (http://tetgen.berlios.de/). The final mesh contained around 65 000 nodes and 400 000 elements.

For numerical simulation studies, the set of optical source and detector pairs was positioned on the outer surface of the head. We used a semi-automated position refinement algorithm based on a connected spring-relaxation model as described in Huppert (2007) to match the appropriate spacing between the source and detector pairs. For the data we will show from experimental studies, the location of the optical sensors was initially found from vitamin E fidicual markers placed on the probe and located via the structural MRI. Since there is a slight offset in the location of the vitamin E markers due to the thickness of the head probe materials, once the initial position of the fibers had been found, the spring-relaxation code was used to adjust the positions. Once the position of each optical source and detector was obtained, the optical forward model was computed using the finite element solver NIRFAST (Dehghani et al 2003). The optical properties for the differing layers used in the NIRFAST model are given in table 2 (Strangman et al 2003).

Table 2.

Optical absorption and scattering properties used in the calculation of the optical forward model.

| 830 nm | 830 nm | 690 nm | 690 nm | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue label | μA mm−1 |

|

μA mm−1 |

|

||

| Skin | 0.0191 | 0.66 | 0.0159 | 0.80 | ||

| Skull | 0.0136 | 0.86 | 0.0101 | 1.00 | ||

| CSF | 0.0026 | 0.01 | 0.0004 | 0.01 | ||

| Gray matter | 0.0186 | 1.11 | 0.1780 | 1.25 | ||

| White matter | 0.0186 | 1.11 | 0.1780 | 1.25 |

3.3. Description of numerical simulation methods

In order to initially examine the performance of this model, we generated a series of numerical simulations to model the expected optical signals. For various portions of the results section, we will show data from simulations in the visual cortex region. The probe position that was used to generate these simulations is shown in figure 6.

Figure 6.

Top left: optical probe used in numerical examples for simulated brain activity in the occipital cortex. The optical sensitivity (forward model) is shown on the pial surface of the brain. Bottom left: schematic of the optical probe design. A time-multiplexing scheme was used for the experimental data in which three states (laser position 1 only, laser position 2 only, and laser positions 3 and 4) were sequentially switched. Top right: sensitivity (forward) model of the optical measurement at the inflated surface of the brain. Bottom right: inflated MR image showing the sulci and gyri structures corresponding to the optical forward model. Optical sensitivity can be observed to be lower in the sulci regions.

The probe used for simulated measurements from the visual cortex (figure 6) measurements was an example of an overlapping probe design (Boas et al 2004). For each simulation, one or two areas of hemodynamic changes were simulated either on the surface of the cortex (section 4.2) or as three-dimensional perturbations within the volume of the brain (section 4.3) and projected through the optical forward model. Additional random noise was added to the observation vector as noted. We used a sample structural MRI obtained from one of our experimental subjects (see section 3.4) for the calculation of the optical forward model for these numerical simulations.

3.4. Experimental methods

As a further example to demonstrate the performance of our model, we collected simultaneous functional MRI and optical imaging data for two example tasks; a simple visual mapping experiment using the overlapping optical probe (shown in figure 6) and a reading task using the lateral probe (shown in figure 7). These two probes were used to demonstrate the performance of the model with an overlapping (tomographic) probe geometry (visual study) and a simpler nearest-neighbor probe geometry (lateral cortex measurements). While previous work by Boas et al (2004) and Joseph et al (2006) had shown that overlapping optical measurements provide more uniform sensitivity and depth sensitivity, currently most studies still utilize the simpler and easier to acquire nearest-neighbor type probe. Thus, we have chosen to present an example of both to demonstrate the versatility of our approach. In the visual mapping task, the subject viewed a simple full-field checkerboard pattern which switched contrast at 4 Hz for a 20 s on/off blocked design. The checkerboard was projected onto a screen at the head of the MRI magnet and was viewed by the subject using a 45° angled mirror. In the reading task, the subject was presented with passages from the reading comprehension portion of the GRE (Graduate Record Exam) standard test. The subject silently reads each passage at a self-paced rate. Each passage took between 90 and 264 s to complete (a total of 11 passages were read).

Figure 7.

Top left: location and sensitivity (forward model) for the optical probe used for experimental measurements of brain activity in the reading task. Bottom left: schematic of the probe. Top right: the optical forward model (sensitivity) for the probe shown on the inflated surface of the brain. Bottom right: MR image showing the sulci and gyri structures.

Concurrent optical and fMRI signals were recorded. For optical recordings, we used a continuous wave optical instrument (CW6; TechEn Inc., Milford, MA) (Joseph et al 2006). The data collection rate of this instrument was software selectable at a rate up to 50 Hz. Two wavelengths (830 nm and 690 nm) were recorded. A few 10 m long fiber optic cables were used for collection of the optical data inside the MRI scanner. Vitamin E was used to mark the location of the optical probes for registration with the structural MRI and calculation of the optical forward model. For the reading task, data were collected at 4 Hz and processed in real time as described in Abdelnour and Huppert (2009). For the visual study, data were collected at 30 Hz. To collect overlapping measurements, a time-division switching scheme was used as described in Boas et al (2004). Three states of optical source–detector combinations were recorded (state 1, only laser 1 on; state 2, only laser 2 on; state 3, lasers 3; and 4 on as depicted in figure 6). The detector gains were adjusted for each of the three states. A complete state cycle was switched at 1Hz with a 90% duty cycle (each state was on for 300 ms). Data were linearly interpolated prior to further analysis as previously described in Joseph et al (2006). Both sets of optical data were low-pass (<0.5Hz) filtered and converted to optical density changes. A box-car general linear model was used to determine the functional contrast for each channel using linear regression. The mean contrast for each channel was used for image reconstruction by the wavelet reconstruction model. Structural and functional MRI was collected using a 3T Siemens TRIO scanner using a 12-channel SENSE head coil. The standard Siemens structural sequence (MPRAGE; 4.3 min; TE = 3.52 ms; TR = 2300 ms; FA = 9°; 256 × 256 × 192 voxels; 0.94 × 0.94 × 1.6 mm resolution) was used to collect anatomical information. A T2-BOLD (blood oxygen level-dependent) sequence (Gradient Echo; TE = 32 ms; TR = 1250 ms; FA = 90°; 64 × 64 × 16; 3.5 × 3.5 × 3.5 mm resolution). fMRI data were analyzed using a box-car general linear model and contrast maps were calculated using a T-test. All studies were approved by local IRB at the University of Pittsburgh.

4. Results

In order to examine and validate this proposed model, in this section we will first show a series of numerical examples of simulations of optical measurements under various conditions. Each of these examples is used to emphasize a different aspect of the model including the scaling properties of the wavelet filterbank, the performance of the modified Shannon entropy metric for determining the optimal regularization of the model, and the robustness of the model to additive random noise in the observation space. Finally, we will show experimental examples of this model with comparison to concurrently measured functional MRI.

4.1. Point-spread function of the wavelet model

One of the main advantages of the use of wavelets is the ability to model a signal at various levels of spatial resolution. Each of the levels of the wavelet model approximates the image at different spatial scales. In particular, as more levels of wavelets are used, a higher resolution image can be modeled. Thus, there is a tradeoff between a higher resolution image and the number of degrees-of-freedom of the model. In figure 8, we demonstrate the point-spread function of the wavelet model when evaluated from the various levels J. When all five levels of the model are used (denoted J = 5), there is perfect recovery of the point object since the wavelet basis forms a complete basis at the mesh resolution. As the higher levels are removed, a broader point-spread function is revealed. For this model, the resolution reduces from 4 mm2 for the J = 5 case, to 294 mm2 at J = 1. The multiscale property of the wavelet model makes it possible to restrict the degrees of freedom of the estimated β vector, for example by recovering an image at up to J = 4 only by removing the columns of the wavelet matrix corresponding to high frequency (edge features). The flexibility offered by the multiresolution feature of the wavelet model favorably compares with the regularization methods where Gaussian filtering is used for smoothing. Gaussian filtering has fixed resolution in general and thus lacks feature selectivity offered by wavelets approach.

Figure 8.

‘Truth’ image of the spread function response, and the recovered image at various levels of resolution J. Level J = 1 corresponds to the lowest resolution (294 mm2), while level J = 5 leads to full recovery (perfect reconstruction) and the highest resolution (4 mm2).

4.2. Performance of the surface-texture reconstruction model

Numerical simulations were preformed to evaluate the performance of the surface-based wavelet reconstruction model. A simulated activity pattern was generated in the primary visual cortex (co-localized changes of +5 μM oxy-hemoglobin and −2 μM deoxy-hemoglobin) and projected through the optical forward model for the visual probe shown in figure 6. Using the wavelet spatial basis, a truncated singular value decomposition pseudo-inversion was performed. As representative of the results, in figures 9 (oxy-hemoglobin) and 10 (deoxy-hemoglobin), we show the images reconstructed using the first 5, 9, 22, 28 and 40 (full) singular values. As more singular values are used for the inverse model, more focal details of the image reconstruction and less partial volume errors are observed. In particular, when few singular values are used, the magnitude of the recovered activations is underestimated. However, as even more singular values are added, artifacts at the edges of the probe become more apparent as the model becomes less regularized. Although in this simulated case, we have the luxury of a direct comparison to the truth image and can see that the image reconstruction using approximately 28 singular values is desirable, in the realistic case, we do not know ground truth.

Figure 9.

Oxyhemoglobin images recovered at various numbers of singular values, N0. N0 = 28 was determined to give the optimal reconstruction based on the Shannon diversity metric.

As aforementioned, one of the properties of the wavelet model is the compression of information onto only a few wavelet coefficients while the majority of the remaining coefficients are near zero (sparse loading). This property is quantifiable by metrics such as the Shannon diversity value described in section 2.5. The Shannon diversity metric provides a means to select the optimal regularization level in the truncated SVD pseudo-inversion. The diversity of the estimated wavelet coefficients was calculated for each level of regularization and is shown in figure 11(B). The normalized reconstruction error (root mean of the squared difference between the recovered and truth images) is also plotted (figure 11(A)). The Shannon diversity metric has three clear peaks at 5, 9 and 28 singular values (reconstructions at these positions were depicted in figures 9 and 10). This represents the density of information (e.g. entropy per singular value) in the image reconstruction. Using this as a basis to judge the optimal reconstruction level, we select 28 singular values as the optimal reconstruction level. In figure 11(A), there is a minimum in the curve of the reconstructed error between 21 and 27 singular values. Small errors near the edges of the probe (as shown in figure 6) appear around 27 singular values, which cause the overall error metric to increase. However, the recovered target has more uniform contrast and correctly defined boundaries at this level of regularization, which agrees with the estimate from the Shannon entropy metric that 28 singular values are near optimal.

Figure 11.

Reconstruction error (figure 11(A)), as a function of N0, and the modified Shannon diversity metric as a function of N0 corresponding to the simulation in section 4.2. The points ‘*’ indicate the singular values where the images were reconstructed (also see figures 9 and 10).

Figure 10.

Deoxy-hemoglobin images recovered at various numbers of singular values, N0 for the same simulation presented in figure 9.

4.3. Comparison of wavelet-, surface- and volume-based reconstructions

Again using the visual cortex as a model, we simulated two separate regions of activation. An oxy-hemoglobin only (+10 μM) change was simulated in the left hemisphere and a deoxy-hemoglobin change (−2.5 μM) was simulated in the right hemisphere. In this case, the positioning of oxy-hemoglobin only and deoxy-hemoglobin only changes on opposite hemispheres allows us to examine cross-talk in the reconstruction. Both regions were simulated as three-dimensional spheres with a radius of 12 mm. These regions were simulated at a depth of 6 mm below the surface of the brain in volume space on the finite element grid. Measurements were then calculated using the full three-dimensional optical forward model. We preformed three separate image reconstructions using

the wavelet/surface model;

restricting activity only to the surface but not using the wavelet model;

reconstructing a cortically-constrained volumetric image without using the wavelet model (e.g. Boas and Dale (2005)). For the wavelet model, we used the full five levels of the model (J = 5) such that the surface-based models with and without the wavelet substitution contained the same number of degrees of freedom (2, 700 degrees-of-freedom total; 1, 350 per oxy- and deoxy-hemoglobin).

The volumetric model had considerably more degrees of freedom (20, 100 degrees-of-freedom total). The optimal regularization level for the wavelet model was selected from the Shannon diversity metric (nSV = 28). Since the diversity metric does not apply for the non-wavelet models, we selected the number of singular values for the surface- and volume-based images based on comparison to the truth image by minimizing the mean-squared error to the original image. In other words, we tried to obtain the best possible scenario of these models for comparison to the wavelet based method. Note that in the non-wavelet reconstructions, our use of the match to the original (truth) image as the criterion for regularization is unrealistic since this image is generally unknown. However, this provides justifiable grounds for comparison of the wavelet method. In the wavelet-based reconstructions, we are using the Shannon diversity to select the optical regularization point in the truncated SVD inverse model. In figure 12, we show the image reconstruction results for these three models along with the simulated truth images. For the truth images (figure 12(A)) and volumetric reconstruction (figure 12(D)), the estimated activation pattern was projected to the nearest vertex points on the surface (maximum intensity projection along the surface norm) for display and comparison to the surface based methods.

Figure 12.

Image recovery with cross-talk. Panel (A) shows simulated active regions, oxy-hemoglobin (+10 μM) on the left hemisphere, and deoxy-hemoglobin (−2.5 μM) on the right hemisphere. Panel (B) shows the recovered images using surface wavelets and truncated SVD. Panel (C) shows the images surface-based reconstructed using truncated SVD (no wavelets). Panel (D) shows the recovered images using volume-based reconstruction.

For all three reconstruction methods, we see that the location of the oxy-hemoglobin activation is fairly accurate. The amplitude of the surface wavelet and surface reconstructions is fairly accurate as well. However, the volumetric-based reconstruction is substantially underestimated. This is the result of the truncated SVD inversion procedure, which tends to underestimate the image when only a few singular values are used despite the imposition of the cortical constraint to the model. For the surface (no wavelets) and volumetric reconstructions, the deoxy-hemoglobin recovery was notably worse than for oxy-hemoglobin with substantial cross-talk. Because we have used a forward model with spectral priors to simultaneously model both hemoglobin species, only a single level of regularization can be used as imposed by truncated SVD inversion. Since deoxy-hemoglobin changes are smaller than oxy-hemoglobin (both in our simulation and in real data), we found that truncated SVD inversion tended to favor better oxy-hemoglobin images.

The image reconstruction using the wavelet representation (figure 12(B)) gave the best approximation to the truth image. This was despite the fact that the truth simulation was generated as a volume object and our image reconstruction approximates this using only the surface. This is not particularly surprising given that the surface constrained model had almost 90% less degrees of freedom. As expected, due to the surface approximation, the magnitude of the recovered image was underestimated by about 10–20% (values of around 9 μM and −2 μM were recovered for oxy- and deoxy-hemoglobin compared to the simulation values of 10 μM and −2.5 μM). The wavelet model shows a slight spatial smoothing of the images, particularly toward the bottom of the probe. However, the center locations of the activations (denoted by a dotted line in the figure) are fairly accurate. At the lower portion of the image on the left hemisphere, there was a slight cross-talk error in the reconstruction of deoxy-hemoglobin. However, cross-talk at the center of the activation patterns was minimal.

The direct surface reconstruction model without wavelets (figure 12(C)) also had approximately the correct location for the reconstructed oxy- and deoxy-hemoglobin activations. However, the spatial uniformity and extent of the recovered patterns were smaller than the actual simulated area (an artifact of the ill-posed nature of this reconstruction). The magnitude of these images was close to correct and similar to the wavelet-based methods. In comparison to the wavelet model, there was substantially more cross-talk in the deoxy-hemoglobin image on the right hemisphere due to oxy-hemoglobin. This was around a 15% error. In the final case of the volume-based image reconstruction (figure 12(D)), the resulting images were the poorest. This is due to the very high number of degrees of freedom of this model and the consequent requirement for high over-regularization via the inverse procedure needed to constrain the model. Despite this, the activations were qualitatively in the correct locations although the amplitudes were underestimated by almost an order of magnitude. The cross-talk in the deoxy-hemoglobin image was rather large (around 30% error; +0.53 μM artifact seen on the left hemisphere due to oxy-hemoglobin cross-talk), which made the crosstalk artifact on the left hemisphere larger than the recovered deoxy-hemoglobin image on the right. In the volume-based reconstruction, the recovered images were substantially below the correct values (around 1.8 μM and −0.23 μM compared to the simulated 10 μM and −2.5 μM for oxy- and deoxy-hemoglobin, respectively).

Figure 13 shows the singular value spectra from the forward model using wavelets at levels J = 4 and J = 5, surface-based reconstruction without surface wavelets and volume-based reconstruction. The condition of the wavelet and direct surface models is very comparable, but much better conditioned than the volume method as seen in the span of the eigenvalues of the SVD of the forward models. The available eigenvalues for truncated SVD inversion are dictated by the number of singular values that are above a given noise level (or precision of the model). Thus, the surface and surface-wavelet models would be expected to tolerate higher levels of noise compared to the volume-based reconstruction.

Figure 13.

Panel (A) shows the singular values resulting from the singular value decomposition of the various reconstruction models. Panel (B) depicts the cumulative sum of the singular values for reconstruction models using wavelets, surface reconstruction without wavelets and volume reconstruction.

4.4. Noise tolerance

As a final numerical test of our model, we examined image reconstruction in the presence of randomized noise in the measurement space. For this example, we simulated activity in the visual cortex using the probe shown in figure 6. The simulated activation had a radius of 12 mm and was placed on the surface of the brain. We added various levels of normal-distributed white noise to the observation vector and preformed reconstructions of the model and preformed reconstructions as before. In figure 14, we show the Shannon diversity curves for the selection of the optimal truncation point of the inverse model at signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of 1:1 through no noise (SNR = ∞). The SNR was defined as the ratio of the standard deviation of the signal (change in optical density) across the spatial channels divided by the standard deviation of the additive noise across the channels, given by σβ/σn, where σβ is the standard deviation of the oxy/deoxy hemoglobin signal and σn is the standard deviation of the additive noise.

Figure 14.

Image recovery in the presence of noise. As the signal-to-noise ratio decreases, less singular values above the noise level are available for image reconstruction.

The quality of the image reconstruction by truncated SVD pseudo-inversion is determined in part by the number of singular values that are above the specific noise floor. When the singular values from the decomposition of the forward model are less than the noise level, reconstruction at and above this number of components is highly susceptible to the noise. One of the advantages of the wavelet-based method as noted in the previous section is that the singular value spectrum loads a higher fraction of the information in the first few components. Wavelet representation leads to relatively few coefficients preserving a high percentage of information (images features). Since the wavelet model is more sparsely represented compared to direct reconstruction of a surface or volume image, an accurate image can be represented with less singular values. In other words, the optimal reconstruction is achieved using less singular values. Thus, the wavelet model is more tolerant to increased random noise.

In the reconstructed images presented in figure 14, a peak in the Shannon diversity curve at nSV = 28 can be observed. At this level of truncation, images reconstructed from a the simulated measurements at a SNR of 5:1 and above gave almost identical reconstructions which closely matched the simulated truth image in both spatial extent and magnitude. Deoxy-hemoglobin results (not shown) were similar. At a SNR of only 1 : 1, the peak in the entropy curve at nSV = 28 was not identifiable because the singular value at this point was lower than the noise floor. Nevertheless, reconstruction at nSV = 28 still yields reasonable results. The recovered images here were notably more noisy and started to show signal on the left hemisphere and near the top of the probe. We note that by our Shannon entropy metric, for this low SNR, the optimal truncation would not have been as apparent. Instead, the peak at nSV = 7 would have been chosen by this metric. At nSV = 7, the reconstructed images use lower frequency spatial wavelets and result in a smoothing of the image similar to the results presented in figures 9 and 10.

4.5. Experimental comparison of the optical reconstruction method with fMRI

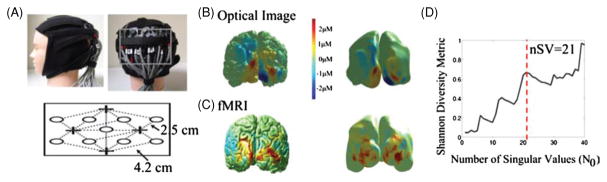

Having examined our model using numerical testing, we applied this method to the reconstruction of experimental data from two case studies of concurrent NIRS and fMRI from the visual and lateral regions of the brain. In the first example, we recorded activation using the visual cortex NIRS probe (as was shown in figure 6) during a flashing checkerboard presentation. The location of the optical probe was obtained from the vitamin E fidicual markers in the MRI structural image. Note that this was the same placement as had been previously used in the simulations. The average NIRS activation magnitudes obtained from the box-car general linear model were used for image reconstruction following the same truncated SVD pseudo-inversion procedure. The experimental results from the optical and fMRI experiments are presented in figure 15. The wavelet reconstructions were preformed to a resolution level of J = 5. In figures 15(B) and (C), we show the results from the optical reconstruction via wavelet regularization and the corresponding fMRI BOLD patterns projected onto the surface. For comparison, we also show the same images on the inflated brain surfaces. This highlights the spatial smoothing effect of the wavelets which is most apparent on this surface. The optical reconstruction provided qualitatively similar pattern to the fMRI. In agreement with the expectation from simulation, the Shannon diversity metric (shown in figure 15(D)) does have peaks at 8, 13 and 21 singular values that are apparent above the noise floor effect. 21 components were used for this reconstruction as shown in figure 15(B).

Figure 15.

(A) Optical imaging with a visual probe, (B) optical images as projected on the MR structural image as a prior, (C) fMRI shown as a full 240 000 node surface and (D) modified Shannon diversity metric as a function of the number of singular values. Images reconstructed at nSV = 21 as the optimal choice for the experimental data based on the modified Shannon diversity metric.

In a second example, we show concurrent NIRS and fMRI results from a reading task. NIRS signals were measured using the lateral probe (shown in figures 16(A) and (B)) during silent reading of a paragraph. This task gave activations in Broca’s area as seen by fMRI (figure 16(C)). The corresponding area was observed using the optical wavelet reconstruction method (figure 16(B)). In this case, since a nearest-neighbor measurement geometry was used, the resulting optical image has notably lower spatial resolution compared to the fMRI, as is even more apparent as presented on the inflated brain surfaces. Similar to the visual study, the Shannon diversity metric had a distinct peak. The reconstructions were preformed at nSV = 11.

Figure 16.

(A) Optical imaging with a lateral probe, (B) optical images as projected on the MR structural image as a prior, (C) fMRI shown as a full 240 000 node surface and (D) modified Shannon diversity metric as a function of the number of singular values. Images reconstructed at nSV = 11.

5. Discussion

Accurate image reconstruction of diffuse optical data has long been a difficult inverse problem. In this work, we have proposed a novel reconstruction method using a wavelet-based basis set defined from the extracted anatomical surface of the brain. In this approach, we approximate the optical signal as originating near the outer surface of the brain, while we perform a two-dimensional (topographic) reconstruction of oxy- and deoxy-hemoglobin changes directly onto the folded surface of the cortex. This approximation is motivated by both our knowledge of the anatomy and functional organization of the human cortex and by the specific characteristics of the optical signal and inverse problem. While this is an approximation to the full optical tomography (volumetric) problem, this approach has many advantages that we believe justifies this assumption. In particular, in this paper, we have demonstrated that our surface-wavelet approach produces much more reliable lateral localization of brain activity compared to both surface-constrained and volumetric reconstructions without the wavelet kernel. The wavelet matrix also provides a means to model a range of spatial scales allowing a tradeoff between lateral spatial resolution and degrees of freedom of the inverse model. In effect, this model acts as a spatial smoothing operation, but unlike the traditional Gaussian smoothing kernels previously used in optical (Huppert et al 2008) and fMRI analysis, the wavelet-based smoothing is constrained to the cortical surface which prevents blurring across proximal but not directly connected regions. For example, this smoothing occurs along the ridges of gyri, but avoids bridging across gyri. This provides a means to incorporate high-resolution anatomical information into image reconstruction and adds an informal prior that functional activation areas tend to be localized within gyri. Finally, we have introduced a reconstruction metric motivated by the nature of the wavelets themselves. From theory, the estimated wavelet coefficients of the transform of a natural image are expected to exhibit sparse loading characteristics (e.g. most of the values are zero or near zero). We introduced the Shannon diversity metric and truncated SVD pseudo-inversion procedure as a means of inverting our model. In the absence of noise, this provided an extremely robust metric to select the optimal inverse model. With the addition of noise, this approach still provided accurate reconstructions up to the point where the singular values of the SVD of the forward model dropped below the noise floor. In addition, although our inverse model was equally under-determined compared the equivalent non-wavelet models (e.g. underlying forward transform of comparable condition), because of the nature of the wavelet model accurate reconstructions could be obtained using less components of the SVD inverse model. This was the result of more information loaded into the first few components compared to the non-wavelet models. This resulted in our model being less sensitive to additive measurement noise.