Summary

The recently solved X-ray crystal structures of archaeal RNA polymerase allows a structural comparison of the transcription machinery among all three domains of life. Archaeal transcription is very simple and all components, including the structures of general transcription factors and RNA polymerase, are highly conserved in eukaryotes. Therefore, it could be a new model for dissection of the eukaryotic transcription apparatus. The archaeal RNA polymerase structure also provides a framework for addressing the functional role that Fe–S clusters play within the transcription machinery of archaea and eukaryotes. A comparison between bacterial and archaeal open complex models reveals likely key motifs of archaeal RNA polymerase for DNA unwinding during the open complex formation.

Introduction

The archaea were once thought as primitive as the other prokaryotic lineage, the bacteria; however, some of their genes, including those encoding DNA replication, RNA transcription and protein translation factors, are now considered to be more closely related to those in eukaryotes. W. Zillig and his colleagues initiated studies of archaeal RNA polymerase (RNAP) and archaeal transcription in the late 70's. They established that the subunit composition of the archaeal RNAP resembles that of eukaryotic RNAP [1–3]. Later, Bell and Jackson provided evidence that archaeal RNAP transcription requires only the eukaryotic-like general transcription factors TBP and TFB, which correspond to the eukaryotic RNAP II (Pol II) general transcription factor TFIIB [4].

The archaeal transcription apparatus can be described as a simplified version of the Pol II counterpart, comprising a Pol II-like enzyme and the general transcription factors TBP, TFB, TFE and TFS (eukaryotic TBP, TFIIB, TFIIEα and TFIIS orthologs, respectively). Remarkably, the transcription regulators found in archaeal genomes are closely related to bacterial factors [5]. Therefore, elucidating the transcription mechanism in archaea, which is a mosaic of bacterial and eukaryotic features, will provide insights into basic transcription mechanisms across all three domains of life. In addition, precise comparisons among cellular RNAP structures could reveal structural elements common to all enzymes and these insights would be useful to analyze components of each enzyme that enable it to perform domain-specific gene expression.

During the past decade, our understanding of cellular transcription processes has been drastically advanced by pioneering X-ray crystallographic studies of bacterial RNAP [6–8] and eukaryotic Pol II [9–12]. However, until recently, the structure of archaeal RNAP had been limited to individual subunits [13,14].

Archaeal RNA polymerase

Two X-ray crystallographic structures of archaeal RNAPs from Sulfolobus solfataricus [15] and Sulfolobus shibatae [16] have been reported. The RNAP from S. solfataricus was reported in 2008. The S. shibatae RNAP structure, reported in 2009, contains all components of Sulfolobus RNAP. This structure identified a new subunit, Rpo13, which is only found in the order Sulfolobales, and is located at a groove between the H subunit and the clamp head domain of the A' subunit. The S. shibatae RNAP structure allowed us to complete the model building and structure refinement of the S. solfataricus RNAP (PDB: 3HKZ, Rwork=27 %, Rfree=34%), which we use in this review (Fig. 1). The new structure contains all components of S. solfataricus RNAP, including the A' subunit jaw and clamp head domains and RpoG and Rpo13 subunits that are missing in the previous structure [15]. The cryo-electron microscopy structure of Pyrococcus furiosus RNAP showed the same overall structure as the X-ray crystal structure [17], but it lacks Rpb8 and Rpo13 subunits. Because of the high sequence conservation among RNAPs from all species in archaea, structural insights derived from the S. solfataricus RNAP can be generalized to the transcription apparatus from this entire domain.

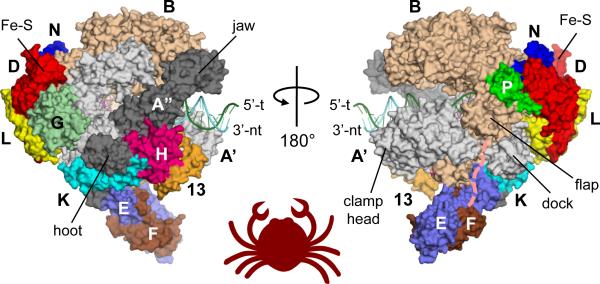

Figure 1.

A surface representation of the 13-subunit Sulfolobus solfataricus RNAP structure (PDB: 3HKZ). Each subunit is denoted by a unique color and labelled. Various structural features discussed in the text are also labelled (Fe-S: 4Fe-4S cluster binding domain). Template (green) and non-template (cyan) DNA strands are from the S. cerevisiae transcription elongation complex (PDB: 2E2H), superimposed using secondary structure matching between D/L and Rpb3/Rpb11 subcomplexes. A putative pathway of the transcribing RNA is shown by the pink dashed line.

The S. solfataricus RNAP structure revealed a crab claw-like molecule, with a 27 Å wide internal channel (Fig. 1). The molecule is about 130 Å long (from the G subunit to the tip of the B subunit claw), 115 Å tall (from the P subunit to the A” subunit jaw) and 160 Å wide (from the E subunit to the B subunit). The enzyme active site is located on the back wall of the channel, where an essential Mg2+ ion is chelated by three Asp of the absolutely conserved NADFDGD motif in the A' subunit. The overall shape and size of the archaeal RNAP are similar to those of the Pol II from Saccharomyces cerevisiae [12] and Schizosacharomyces pombe [10] (Fig. 2A); the folding of highly conserved segments around the active site are essentially identical.

Figure 2.

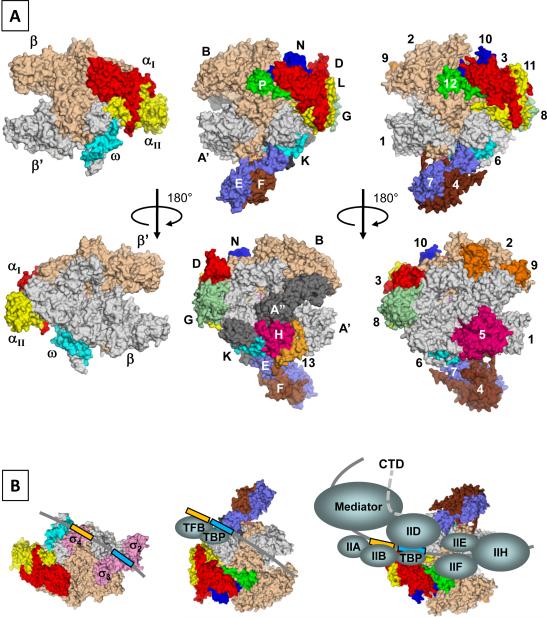

Cellular RNAP structures and transcription pre-initiation complexes from three domains of life. A) Surface representations of cellular RNAP structures from bacteria (left, T. aquaticus core enzyme), archaea (center, S. Solfataricus RNAP) and eukayote (right, S. cerevisiae Pol II). Each subunit is denoted by a unique color and labelled. Orthologous subunits are depicted with the same color. B) Models of PIC in bacteria (left), archaea (center) and eukaryote (right). Bacterial σ factor is colored pink and its three domains are labeled. DNA is depicted with a grey line (transcription start site is at right side). Promoter −10 and −35 elements in bacterial transcription and TATA-box and BRE in archaeal and eukaryotic transcriptions are shown as light blue and light orange boxes, respectively. The Pol II CTD is disordered in the X-ray crystal structure and is depicted as a dashed line.

Function of the protruding stalk

Compared to the bacterial RNAP, archaeal RNAP possesses a characteristic protruding stalk that is formed by a heterodimer of E and F subunits (Fig. 2A). The same heterodimer structure can be found in all three classes of eukaryotic RNAPs – A43/A14 in Pol I [18], Rpb7/Rpb4 in Pol II [10,12] and C25/C17 in Pol III [19] – and their relative positioning of the RNAP core and stalk are also highly conserved, suggesting that the heterodimer was acquired by a core RNAP common ancestor. Although the binding mode of the subcomplex to the core is conserved in archaeal and eukaryotic RNAPs, the relative binding affinities differ. S. solfataricus E/F binds tightly to its core (their interaction is maintained in the presence of 3.5 M urea at 70 °C) suggesting stoichiometric association regardless of growth conditions (Hirata and Murakami, unpublished data). Stable association of the Methanocaldococcus jannaschii E/F to the core RNAP was also reported [20]. In S. cerevisiae, the subcomplex can be readily removed from the core [21], which may be relevant in regulating the relative amounts of 10-subunit versus 12-subunit Pol II during growth transitions. Sub-stoichiometric association of the Rpb7/Rpb4 subcomplex with the core RNAP is specific to S. cerevisiae since the Rpb7/Rpb4 is stoichiometric in S. pombe and humans. However, results from ChIP-on-chip assays indicate that the genome-wide occupancies of Rpb7 (protruding stalk) and Rpb3 (core subunit) in S. cerevisiae cells are essentially identical, suggesting that the Rpb7/Rpb4 subcomplex associates with the core polymerase throughout the transcription in vivo [22].

Besides modulating the clamp conformation [23,24] and RNA binding during transcription elongation [25–27] (Fig. 1), a new function of the protruding heterodimer has been revealed. Genetic studies of Thermococcus kodakarensis RNAP have shown that the F subunit coding gene, rpoF, is not required for cell viability and that the mutant enzyme purified from ΔrpoF cells lacks not only F subunit but also E subunit [28]. Furthermore, in vitro, this core RNAP exhibited no discernible differences from wild-type RNAP in promoter-dependent transcription, abortive transcript synthesis, and transcript elongation or termination at any temperature. Interestingly, the core RNAP also lacks the transcription factor TFE that co-purifies with RNAP from wild-type cells [29,30]. In addition, in vitro reconstitution of RNAP has identified the E subunit as being required for TFE functions for archaeal RNAP transcription initiation [31] and elongation [32]. Given these observations, it seems most likely that the protruding heterodimer provide targets for transcription factor binding, and so facilitate RNAP recruitment. Accordingly, ΔrpoF cells were heat sensitive and the expression of a small fraction of the genes, including chaperonin subunit cpkB, was affected [28]. This hypothesis can be applied to eukaryotic RNAPs. The Rpb7/Rpb4 of Pol II has been shown to interact with TFIIF [33]. The extensions formed in Pol I (A43/A14) and in Pol III (C25/C17) interact with polymerase-specific transcription initiation factors that recruit Pol I and Pol III to the appropriate promoters [34,35].

The archaeal transcription initiation process

From a structural perspective, it is interesting to point out that almost all the structural differences between archaeal and eukaryotic RNAPs can be classified as simple addition of Pol II-specific polypeptides – Rpb9, Rpb5 jaw and the Rpb1 C-terminal hepta peptides repeat sequence (Pol II-CTD) – to the archaeal RNAP, rather than changes to the main RNAP architecture. During evolution, it appears likely that the structure of archaeal RNAP has been maintained from the ancestor of archaea and eukaryotes. Furthermore, the simple addition of subunits and domains to its original RNAP structure is sufficient to allow Pol II to communicate with general transcription factors as well as a mediator complex to form a giant transcription pre-initiation complex (PIC) with a total mass of ~2.5 MDa [37], in contrast to the 2 polypeptides – TBP and TFB – required for archaeal transcription [4] (Fig. 2B).

In order to form a transcription-ready open complex from the PIC, RNAP unwinds double-stranded DNA extending from ~11 base pairs upstream to a few base pairs downstream from the transcription start site. This process may require additional protein factor(s), which can vary depending on the organism (Fig. 2B). In bacteria, the σ factor binds to the core RNAP to form the holoenzyme, and is essential for both promoter recognition and DNA unwinding [38]. The primary σ factor utilizes aromatic residues in region 2.3 for this process [39]. In Pol II-dependent transcription, five general transcription factors and a mediator assemble on promoter DNA in order to recruit the RNAP to form the PIC, and TFIIF and TFIIH are known to play several critical roles in open complex formation [37]. The cryo-electron microscopy studies of the Pol II/TFIIF complex identified the structural counterpart of the bacterial σ domain 2, which includes region 2.3, in the Tfg2 subunit of TFIIF [33]. In archaea, TBP and TFB are the only proteins required for PIC formation; these proteins play a role in recruiting RNAP to the promoter. In contrast, the archaeal RNAP is supposed to be inherently equipped with the functional counterpart of σ factor/TFIIF since an additional protein for DNA unwinding is not required.

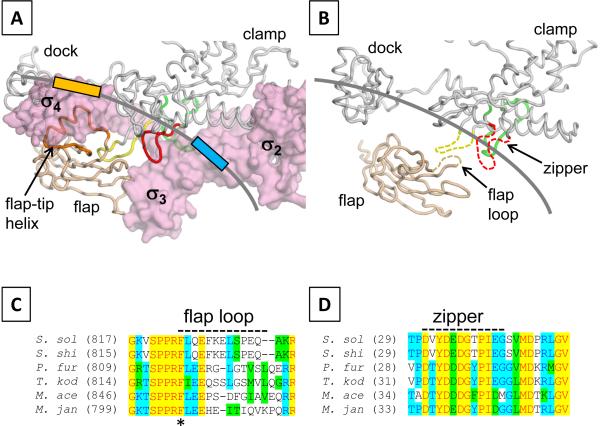

In the promoter open complex, both bacterial and archaeal RNAPs form a transcription bubble of similar size [38,40]. Therefore, both bacterial and archaeal promoter-RNAP complexes may have a similar trajectory of promoter DNA from −11 to the transcription start site. The position of promoter DNA in the bacterial holoenzyme is well defined in the X-ray crystal structure of holoenzyme and fork-junction DNA complex [7]; we used this structure as a guide for positioning promoter DNA in the archaeal RNAP (Fig. 3B). Bacterial RNAP has a unique motif – the flap tip helix – for σ domain 4 binding in the middle of the β subunit flap (Fig. 3A). There is no flap tip helix in the archaeal RNAP; instead, it contains a flexible loop (residues 819–830), which faces to promoter DNA around the –10 region and is ideally positioned near the upstream edge of the transcription bubble (Fig. 3B). The sequence of the flap loop is highly conserved in all archaeal RNAPs, including an absolutely conserved aromatic residue (F819), suggesting that the flap loop plays an important role in DNA opening in archaeal transcription. The importance of the flap for forming the open complex is further strengthened by two lines of results; 1) the position of the flap domain is buttressed by subunit P, which fills a gap between subunit D and the flap domain (Fig. 1A) and 2) RNAP reconstituted without the P subunit is less active relative to the wild-type enzyme [41]. Another important feature of the archaeal PIC model is that the “zipper” in the A' subunit is also positioned around −12 (Fig. 3B), suggesting that the zipper may be involved in DNA binding. The amino acid sequence of zipper is also highly conserved in all archaeal RNAPs (Fig. 3D). There is an interesting correlation between bacterial and archaeal RNAPs; the bacterial zipper sequence is also highly conserved and it is used for interacting with a newly identified promoter sequence, the Z-element, positioned between −22 and −18 bases (N. Zenkin, personal communication).

Figure 3.

Structural basis of DNA unwinding by the archaeal RNAP. A) View of the bacterial RNAP holoenzyme structure. The orientation of this view is the same as in Fig. 2B. The σ surface is rendered transparent. The α-carbon backbone of β subunit flap (light brawn) and of the β' subunit clamp and dock (gray) are shown as a worm. Zipper (red), lid (yellow), rudder (green) and flap-tip helix (orange) are indicated. The position of promoter DNA is shown as a gray line with −35 (light orange) and −10 (light blue) elements. B) View of the archaeal RNAP structure. The α-carbon backbone of the B subunit flap domain (light brawn) and of the A' subunit clamp and dock domains (gray) are shown as a worm. Disordered regions are indicated as dashed lines. The position of promoter DNA is according to A). C) Sequence alignment of the flap loop region of the archaeal B subunit. A disordered flap loop is indicated as a dashed line. An asterisk indicates the absolutely conserved Phe residue. D) Sequence alignment of the zipper region of the archaeal A' subunit. The disordered zipper is indicated as a dashed line.

RNA polymerase is a new member of the iron-sulfur (Fe-S) cluster protein family

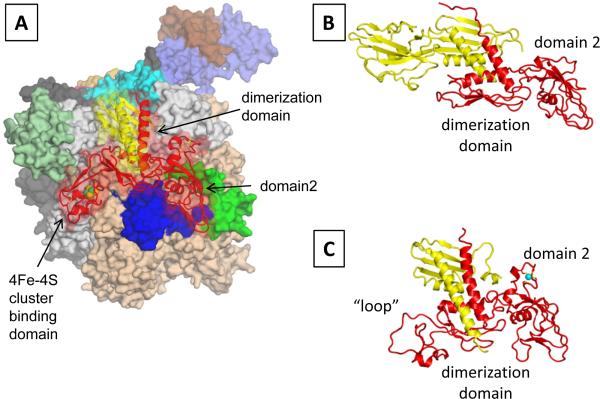

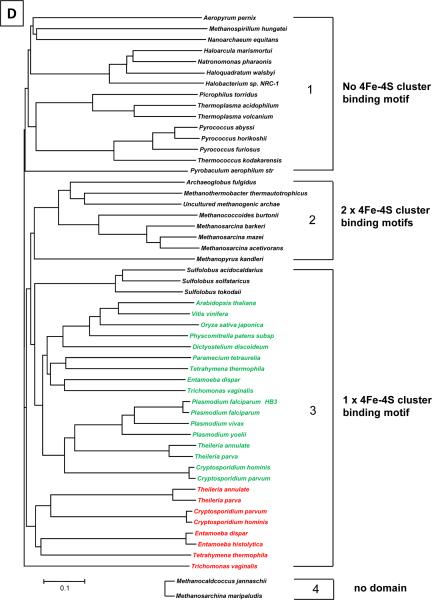

The archaeal D subunit associates with the L subunit to form a stable heterodimer (D/L subconplex, Fig. 4A), which plays an important role in the RNAP assembly [42]. The D subunit has three distinct domains; two of them, including the dimerization domain and domain 2, possess highly conserved amino acid sequences and three-dimensional structures not only in archaea but also in all life forms (Fig. 4). The X-ray crystal structure of D/L subcomplex of S. solfataricus RNAP revealed that the third domain of the D subunit (residues 167–222) possesses a 4Fe-4S cluster binding motif that chelates a 3Fe-4S cluster [15]. Three Cys residues (C183, C203 and C209) provide ligands for the 3Fe-4S cluster; one additional C206 is positioned nearby suggesting that the cluster may exist as 4Fe-4S in vivo. The 4Fe-4S cluster-binding domain is unique to S. solfataricus RNAP; the corresponding region in the Rpb3 of Pol II forms a loosely packed domain (called the `loop', Fig. 4C) [9] while there is no corresponding domain in the bacterial α subunit [43] (Fig. 4B). Interestingly, the 4Fe-4S cluster-binding domain is not conserved in all archaeal RNAPs. In fact, amino acid residues holding the Fe-S cluster in the D subunit characterize a specific evolutionary lineage of archaea. Phylogenetic analysis classifies the D subunit into 4 groups based on the numbers of 4Fe-4S cluster-binding motifs found in this region (Fig. 4D): 1) no Fe-S cluster-binding motif (Thermococcus and Pyrococcus genera and Halobacterium), 2) two 4Fe-4S cluster-binding motifs (Archaeoglobus fulgidus and certain methanogens), 3) one 4Fe-4S cluster-binding motif (Sulfolobus genera), and 4) no amino acid residues (Methanococcus genera). The Fe-S cluster in the S. solfataricus D subunit (1 Fe-S cluster, group 1) is oxygen stable whereas the Fe-S cluster in the A. fulgidus D subunit (2 Fe-S clusters, group 2) is oxygen-labile (Hirata and Murakami, in preparation).

Figure 4.

A) Molecular surface representation of the archaeal RNAP structure. The D/L subcomplex surface is rendered transparent, revealing the cartoon model including Fe-S cluster (green and yellow balls) inside. Three domains of D subunit are indicated. B) Ribbon representation of the bacterial α subunit homodimer (αI: red; αII: yellow). C) Ribbon representation of the yeast Pol II Rpb3/Rpb11 subcomplex (Rpb3: red; Rpb11: yellow). D) Phylogenetic relationship of lineage specific insertion of the archaeal D subunit and the eukaryotic Rpb3 (Pol II) and AC40 (Pol I and III) subunits. The tree was generated using a sequence found between domain 2 and dimerization domain of these subunits. All available archaeal D subunit sequences (black) are presented in this tree and grouped (from 1 to 4) based on number of 4Fe-4S cluster-binding motifs present in the sequence. Eukaryotic Rpb3 (red) and AC40 (green) are shown only if these species contain a 4Fe-4S cluster-binding motif.

What is the function (or functions) of the Fe-S cluster in archaeal RNAP? In the S. solfataricus RNAP structure, the Fe-S cluster is located 45 Å from its catalytic center (Fig. 1) and, therefore, it is unlikely to be involved in RNA synthesis. A recombinant D subunit variant, which cannot chelate the Fe-S cluster forms aggregates even when it was co-expressed with L subunit, suggesting that the cluster may play a role in the structural integrity of the D subunit. Since formation of the D/L subcomplex is essential for archaeal RNAP assembly, it is possible that the Fe-S cluster may be involved as a sensor for detecting oxidative stress or iron availability in cells, which may regulate RNAP production at the level of de novo assembly. Alternatively, the Fe-S cluster may regulate the interaction with transcription factor bound on the promoter DNA depending on the oxidation state of the Fe-S cluster since, like the bacterial RNAP α-subunit C-terminal domain [44], the D subunit Fe-S cluster faces upstream DNA when RNAP binds to the promoter (Fig. 2B).

The 4Fe-4S cluster-binding motif is not limited to archaeal RNAPs. Several eukaryotic genomes, including those of plants and protozoa, encode 4Fe-4S cluster-binding motifs within Rpb3 in Pol II and AC40 in Pol I and III; these subunits are the archaeal D subunit orthologs (Fig. 4D). There is only one 4Fe-4S cluster-binding motif found in the eukaryotic RNAPs. The identification of the Fe-S cluster in an RNAP subunit raises several intriguing questions, including why only certain cellular RNAPs possess an Fe-S cluster and what is the relationship between the presence of an Fe-S cluster in the RNAPs and the environments the cell lives in. The archaeal RNAP structure along with available genetics [45,46] and powerful in vitro RNAP reconstitution [47,48] may provide new insights into the biological function of Fe-S cluster within the archaeal and eukaryotic transcription machineries.

Conclusions

One of the keys to understanding the mechanism of an enzymatic reaction is to have a simple and robust system that can be probed in vitro. Studies on bacterial transcription are the most advanced because the RNAP can be assembled from recombinant subunits with full activity [49]. The same in vitro reconstitution strategy can be applied to the archaeal RNAP [47,48] but not to any eukaryotic RNAPs. Furthermore, a comprehensive and automatic analysis of amino acid substitutions in archaeal RNAP is possible due to a recently developed robotic in vitro assembly platform, so called RNAP factory [50,51]. Biochemical studies, as well as current X-ray crystallographic studies, have established that structural and functional similarities between archaeal RNAP and eukaryotic Pol II exist on many levels. Therefore, archaeal RNAP could be an excellent model system for dissecting the molecular basis of eukaryotic transcription.

Acknowledgements

We thank to L. B. Rothman-Denes for critical reading of the manuscript. All figures were prepared using PyMOL (http://pymol.sourceforge.net/). This work was supported by the Pew Scholars Program in the Biomedical Sciences.

References

- 1.Prangishvilli D, Zillig W, Gierl A, Biesert L, Holz I. DNA-dependent RNA polymerase of thermoacidophilic archaebacteria. Eur J Biochem. 1982;122:471–477. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1982.tb06461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huet J, Schnabel R, Sentenac A, Zillig W. Archaebacteria and eukaryotes possess DNA-dependent RNA polymerases of a common type. EMBO J. 1983;2:1291–1294. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1983.tb01583.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schnabel R, Thomm M, Gerardy-Schahn R, Zillig W, Stetter KO, Huet J. Structural homology between different archaebacterial DNA-dependent RNA polymerases analyzed by immunological comparison of their components. EMBO J. 1983;2:751–755. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1983.tb01495.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bell SD, Jaxel C, Nadal M, Kosa PF, Jackson SP. Temperature, template topology, and factor requirements of archaeal transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:15218–15222. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Geiduschek EP, Ouhammouch M. Archaeal transcription and its regulators. Mol Microbiol. 2005;56:1397–1407. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04627.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang G, Campbell EA, Minakhin L, Richter C, Severinov K, Darst SA. Crystal structure of Thermus aquaticus core RNA polymerase at 3.3 A resolution. Cell. 1999;98:811–824. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81515-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murakami KS, Masuda S, Campbell EA, Muzzin O, Darst SA. Structural basis of transcription initiation: an RNA polymerase holoenzyme-DNA complex. Science. 2002;296:1285–1290. doi: 10.1126/science.1069595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murakami KS, Masuda S, Darst SA. Structural basis of transcription initiation: RNA polymerase holoenzyme at 4 A resolution. Science. 2002;296:1280–1284. doi: 10.1126/science.1069594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cramer P, Bushnell DA, Kornberg RD. Structural basis of transcription: RNA polymerase II at 2.8 angstrom resolution. Science. 2001;292:1863–1876. doi: 10.1126/science.1059493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spahr H, Calero G, Bushnell DA, Kornberg RD. Schizosacharomyces pombe RNA polymerase II at 3.6-A resolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:9185–9190. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903361106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang D, Bushnell DA, Huang X, Westover KD, Levitt M, Kornberg RD. Structural basis of transcription: backtracked RNA polymerase II at 3.4 angstrom resolution. Science. 2009;324:1203–1206. doi: 10.1126/science.1168729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Armache KJ, Mitterweger S, Meinhart A, Cramer P. Structures of complete RNA polymerase II and its subcomplex, Rpb4/7. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:7131–7134. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413038200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Todone F, Brick P, Werner F, Weinzierl RO, Onesti S. Structure of an archaeal homolog of the eukaryotic RNA polymerase II RPB4/RPB7 complex. Mol Cell. 2001;8:1137–1143. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00379-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yee A, Booth V, Dharamsi A, Engel A, Edwards AM, Arrowsmith CH. Solution structure of the RNA polymerase subunit RPB5 from Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:6311–6315. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.12.6311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hirata A, Klein BJ, Murakami KS. The X-ray crystal structure of RNA polymerase from Archaea. Nature. 2008;451:851–854. doi: 10.1038/nature06530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Korkhin Y, Unligil UM, Littlefield O, Nelson PJ, Stuart DI, Sigler PB, Bell SD, Abrescia NG. Evolution of Complex RNA Polymerases: The Complete Archaeal RNA Polymerase Structure. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:e102. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kusser AG, Bertero MG, Naji S, Becker T, Thomm M, Beckmann R, Cramer P. Structure of an archaeal RNA polymerase. J Mol Biol. 2008;376:303–307. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.08.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuhn CD, Geiger SR, Baumli S, Gartmann M, Gerber J, Jennebach S, Mielke T, Tschochner H, Beckmann R, Cramer P. Functional architecture of RNA polymerase I. Cell. 2007;131:1260–1272. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jasiak AJ, Armache KJ, Martens B, Jansen RP, Cramer P. Structural biology of RNA polymerase III: subcomplex C17/25 X-ray structure and 11 subunit enzyme model. Mol Cell. 2006;23:71–81. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grohmann D, Hirtreiter A, Werner F. RNAP subunits F/E (RPB4/7) are stably associated with archaeal RNA polymerase: using fluorescence anisotropy to monitor RNAP assembly in vitro. Biochem J. 2009;421:339–343. doi: 10.1042/BJ20090782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Edwards AM, Kane CM, Young RA, Kornberg RD. Two dissociable subunits of yeast RNA polymerase II stimulate the initiation of transcription at a promoter in vitro. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:71–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jasiak AJ, Hartmann H, Karakasili E, Kalocsay M, Flatley A, Kremmer E, Strasser K, Martin DE, Soding J, Cramer P. Genome-associated RNA polymerase II includes the dissociable Rpb4/7 subcomplex. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:26423–26427. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803237200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bushnell DA, Kornberg RD. Complete, 12-subunit RNA polymerase II at 4.1-A resolution: implications for the initiation of transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:6969–6973. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1130601100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Armache KJ, Kettenberger H, Cramer P. Architecture of initiation-competent 12-subunit RNA polymerase II. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:6964–6968. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1030608100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen CY, Chang CC, Yen CF, Chiu MT, Chang WH. Mapping RNA exit channel on transcribing RNA polymerase II by FRET analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:127–132. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811689106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ujvari A, Luse DS. RNA emerging from the active site of RNA polymerase II interacts with the Rpb7 subunit. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:49–54. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Andrecka J, Lewis R, Bruckner F, Lehmann E, Cramer P, Michaelis J. Single-molecule tracking of mRNA exiting from RNA polymerase II. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:135–140. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703815105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hirata A, Kanai T, Santangelo TJ, Tajiri M, Manabe K, Reeve JN, Imanaka T, Murakami KS. Archaeal RNA polymerase subunits E and F are not required for transcription in vitro, but a Thermococcus kodakarensis mutant lacking subunit F is temperature-sensitive. Mol Microbiol. 2008;70:623–633. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06430.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Santangelo TJ, Cubonova L, James CL, Reeve JN. TFB1 or TFB2 is sufficient for Thermococcus kodakaraensis viability and for basal transcription in vitro. J Mol Biol. 2007;367:344–357. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.12.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Micorescu M, Grunberg S, Franke A, Cramer P, Thomm M, Bartlett M. Archaeal transcription: function of an alternative transcription factor B from Pyrococcus furiosus. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:157–167. doi: 10.1128/JB.01498-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ouhammouch M, Werner F, Weinzierl RO, Geiduschek EP. A fully recombinant system for activator-dependent archaeal transcription. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:51719–51721. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400446200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grunberg S, Bartlett MS, Naji S, Thomm M. Transcription factor E is a part of transcription elongation complexes. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:35482–35490. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707371200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chung WH, Craighead JL, Chang WH, Ezeokonkwo C, Bareket-Samish A, Kornberg RD, Asturias FJ. RNA polymerase II/TFIIF structure and conserved organization of the initiation complex. Mol Cell. 2003;12:1003–1013. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00387-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peyroche G, Milkereit P, Bischler N, Tschochner H, Schultz P, Sentenac A, Carles C, Riva M. The recruitment of RNA polymerase I on rDNA is mediated by the interaction of the A43 subunit with Rrn3. EMBO J. 2000;19:5473–5482. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.20.5473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kassavetis GA, Letts GA, Geiduschek EP. The RNA polymerase III transcription initiation factor TFIIIB participates in two steps of promoter opening. EMBO J. 2001;20:2823–2834. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.11.2823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ream TS, Haag JR, Wierzbicki AT, Nicora CD, Norbeck AD, Zhu JK, Hagen G, Guilfoyle TJ, Pasa-Tolic L, Pikaard CS. Subunit compositions of the RNA-silencing enzymes Pol IV and Pol V reveal their origins as specialized forms of RNA polymerase II. Mol Cell. 2009;33:192–203. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thomas MC, Chiang CM. The general transcription machinery and general cofactors. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2006;41:105–178. doi: 10.1080/10409230600648736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Murakami KS, Darst SA. Bacterial RNA polymerases: the wholo story. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2003;13:31–39. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(02)00005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schroeder LA, Gries TJ, Saecker RM, Record MT, Jr., Harris ME, DeHaseth PL. Evidence for a tyrosineadenine stacking interaction and for a short-lived open intermediate subsequent to initial binding of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase to promoter DNA. J Mol Biol. 2009;385:339–349. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hausner W, Thomm M. Events during initiation of archaeal transcription: open complex formation and DNA-protein interactions. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:3025–3031. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.10.3025-3031.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reich C, Zeller M, Milkereit P, Hausner W, Cramer P, Tschochner H, Thomm M. The archaeal RNA polymerase subunit P and the eukaryotic polymerase subunit Rpb12 are interchangeable in vivo and in vitro. Mol Microbiol. 2009;71:989–1002. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06577.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goede B, Naji S, von Kampen O, Ilg K, Thomm M. Protein-protein interactions in the archaeal transcriptional machinery: binding studies of isolated RNA polymerase subunits and transcription factors. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:30581–30592. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605209200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang G, Darst SA. Structure of the Escherichia coli RNA polymerase alpha subunit amino-terminal domain. Science. 1998;281:262–266. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5374.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lawson CL, Swigon D, Murakami KS, Darst SA, Berman HM, Ebright RH. Catabolite activator protein: DNA binding and transcription activation. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2004;14:10–20. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2004.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sato T, Fukui T, Atomi H, Imanaka T. Improved and versatile transformation system allowing multiple genetic manipulations of the hyperthermophilic archaeon Thermococcus kodakaraensis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:3889–3899. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.7.3889-3899.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Albers SV, Driessen AJM. Conditions for gene disruption by homologous recombination of exogenous DNA into the Sulfolobus solfataricus genome. Archaea. 2007;2:145–149. doi: 10.1155/2008/948014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Naji S, Gruenberg S, Thomm M. The Rpb7 orthologue E' is required for transcriptional activity of a reconstituted archaeal core enzyme at low temperatures and stimulates open complex formation. J Biol Chem. 2007 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611674200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Werner F, Weinzierl RO. A recombinant RNA polymerase II-like enzyme capable of promoter-specific transcription. Mol Cell. 2002;10:635–646. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00629-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zalenskaya K, Lee J, Gujuluva CN, Shin YK, Slutsky M, Goldfarb A. Recombinant RNA polymerase: inducible overexpression, purification and assembly of Escherichia coli rpo gene products. Gene. 1990;89:7–12. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90199-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tan L, Wiesler S, Trzaska D, Carney HC, Weinzierl RO. Bridge helix and trigger loop perturbations generate superactive RNA polymerases. J Biol. 2008;7:40. doi: 10.1186/jbiol98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kaplan CD, Kornberg RD. A bridge to transcription by RNA polymerase. J Biol. 2008;7:39. doi: 10.1186/jbiol99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]