Abstract

An essential step in intricate visual processing is the segregation of visual signals into ON and OFF pathways by retinal bipolar cells (BCs). Glutamate released from photoreceptors modulates the photoresponse of ON BCs via metabotropic glutamate receptor 6 (mGluR6) and G protein (Go) that regulates a cation channel. However, the cation channel has not yet been unequivocally identified. Here, we report a mouse TRPM1 long form (TRPM1-L) as the cation channel. We found that TRPM1-L localization is developmentally restricted to the dendritic tips of ON BCs in colocalization with mGluR6. TRPM1 null mutant mice completely lose the photoresponse of ON BCs but not that of OFF BCs. In the TRPM1-L-expressing cells, TRPM1-L functions as a constitutively active nonselective cation channel and its activity is negatively regulated by Go in the mGluR6 cascade. These results demonstrate that TRPM1-L is a component of the ON BC transduction channel downstream of mGluR6 in ON BCs.

Keywords: G protein, retina, photoresponse, glutamate, vision

Segregation of visual signals into ON and OFF pathways originates in BCs, the second-order neurons in the retina (1, 2). ON and OFF BCs express metabotropic glutamate receptors, mGluR6, and ionotropic glutamate receptors (iGluRs), respectively, on their dendrites (3–5). Reduction of glutamate released from photoreceptors by light stimulation depolarizes ON BCs and hyperpolarizes OFF BCs (6–8) mediated through respective glutamate receptors. The mGluR6 couples to a heterotrimeric G protein complex, Go (9, 10). Signals require Goα, which ultimately closes a downstream nonselective cation channel in ON BCs (6, 9, 11–13). However, this transduction cation channel in ON BCs has not been identified, despite intensive investigation.

In our screen to identify functionally important molecules in the retina, we found that TRPM1 is predominantly expressed in retinal BCs. Most members of the TRP superfamily, which are found in a variety of sense organs, are non-voltage-gated cation channels (14–16). The founding member of the TRP family was discovered as a key component of the light response in Drosophila photoreceptors (17). TRPM1, also known as melastatin, was the first member of the melanoma-related transient receptor potential (TRPM) subfamily to be discovered (18, 19). TRPM1 is alternatively spliced, resulting in the production of a long form (TRPM1-L) and a short N-terminal form devoid of transmembrane segments (TRPM1-S) (18, 20). Although mouse TRPM1-S was previously identified as melastatin, mouse TRPM1-L has not been identified (18). The distinct physiological and biological functions of TRPM1 still remain elusive, although some recent evidences including us suggested that TRPM1 might contribute to retinal BC function (21–23). Here, we show that TRPM1-L is the transduction cation channel of retinal ON BCs in the downstream of mGluR6 cascade.

Results

Isolation of Mouse TRPM1-L.

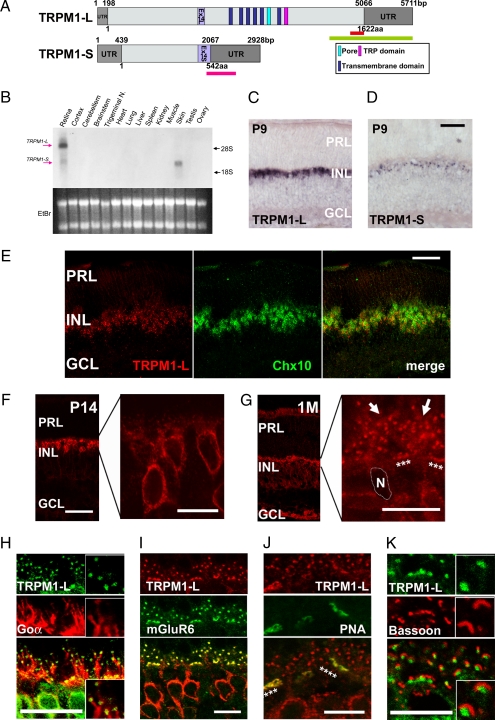

We identified a mouse TRPM1-L cDNA (Fig. 1A) that corresponds to the human TRPM1 long form (20). The mouse TRPM1-L encodes a predicted 1,622-aa protein, containing six transmembrane domains, a pore region, and a TRP domain, as do other major TRP family members (Fig. 1A). Northern blot analysis revealed the presence of both TRPM1-L and -S transcripts in the retina; however, only the latter was detected in the skin (Fig. 1B). In situ hybridization (ISH) showed the presence of substantial TRPM1-L transcripts in the inner nuclear layer (INL) at postnatal stages (Fig. 1C). Faint TRPM1-S signals were detected in the INL at postnatal day 9 (P9) (Fig. 1D). Immunostaining with anti-Chx10 antibody, a pan-BC marker, showed that TRPM1-L signals were located in BCs in the adult retina (Fig. 1E).

Fig. 1.

The molecular analysis and expression of mouse TRPM1-L. (A) Schematic diagrams of full-length mouse TRPM1-L and TRPM1-S genes and their ORFs. Light gray boxes represent ORF, and light purple boxes indicate exon 14 (L and S). Green and pink bars indicate sequences used for TRPM1-L- or TRPM1-S-specific probes, respectively. The red bar indicates amino acid sequence used for generating anti-TRPM1-L antibody. (B) Northern blot analysis of mouse TRPM1 transcription in adult mouse tissues. The sizes of TRPM1-L and TRPM1-S transcripts are ≈6 kb and 3 kb, respectively. Both TRPM1-L and -S transcripts were detected in the retina; however, only the TRPM1-S transcript was detected in the skin. (Lower) Ethidium bromide staining of RNA. Each lane contains ≈10 μg of total RNA. Trigeminal N., trigeminal nucleus. (C and D) ISH analysis of mouse TRPM1 in the postnatal retina. TRPM1-L-specific signal was detected in the INL at P9 (C). TRPM1-S was detected in the INL at P9 (D). PRL, photoreceptor layer; INL, inner nuclear layer; GCL, ganglion cell layer. (Scale bar: 100 μm.) (E) ISH of TRPM1-L mRNA and following immunostaining of anti-Chx10 antibody, a pan-BC marker. (Scale bar: 50 μm.) (F and G) Immunostaining with an antibody against TRPM1-L exhibited TRPM1-L signals in cell bodies of retinal BCs at P14 (F) and at dendritic tips of retinal BCs (stars and arrows) at 1 M (G). N, nucleus of a BC. (Scale bars: 50 μm.) (H–K) Confocal images of OPLs double-labeled with anti-TRPM1-L antibody and other retinal markers. TRPM1-L-positive puncta were localized at the tips of Goα distribution (H). TRPM1-L-positive puncta were colocalized with mGluR6 staining (I). Continuous puncta marked with TRPM1-L were colocalized with PNA (stars) (J). TRPM1-L-positive puncta were surrounded by synaptic ribbons stained with bassoon (K). (Scale bars: 10 μm.)

Localization of TRPM1-L on Dendritic Tips of ON BCs.

Next, we raised an antibody against TRPM1-L (Fig. S1) and examined the localization of TRPM1-L (Fig. 1 F–K and Fig. S1). At P14, TRPM1-L was found diffusely in BC somata (Fig. 1F). At 1 month after birth, TRPM1-L localized to the dendritic tips in the outer plexiform layer (OPL) (Fig. 1G, arrows and stars). This labeling was not observed in the TRPM1 null mutant (TRPM1−/−) mice (Fig. 2D and Fig. S1 B–E). To identify the subtypes of BCs expressing TRPM1-L, we coimmunostained BCs with anti-TRPM1 antibody and several adult retinal BC markers (Fig. 1 H–K and Fig. S1 B–E). Punctated TRPM1-L signals were localized at the tips of Goα-expressing and mGluR6-expressing dendrites (Fig. 1 H and I, and Table S1). We also coimmunostained TRPM1-L with PNA that binds to glycoconjugates associated with the cell membrane and the intersynaptic matrix of cone terminals. The continuous punctated TRPM1-L signals appeared in register with the PNA signals, suggesting that TRPM1-L is localized adjacent to cone photoreceptors as well as to rod photoreceptors (Fig. 1J, indicated by stars, and Table S1). Actually, TRPM1-L was not expressed in photoreceptor terminals because the punctated TRPM1-L signals did not colocalize with bassoon, a marker for the presynaptic photoreceptor structures (Fig. 1K and Table S1). We did not observe distinct colocalization of TRPM1-L with OFF-BC markers (Fig. S2).

Fig. 2.

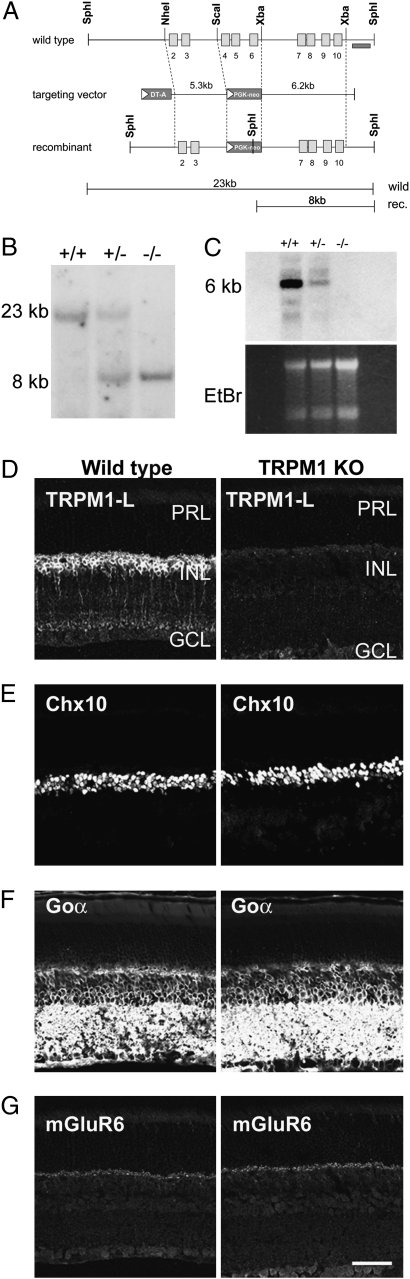

Generation of TRPM1−/− mouse by targeted gene disruption. (A) Strategy for the targeted deletion of TRPM1 gene. The open boxes indicate exons. Exons 4–6 were replaced with the PGK-neo cassette. The probe used for Southern blot analysis is shown as a dark bar. (B) Southern blot analysis of genomic DNA. SphI-digested genomic DNA was hybridized with a 3′ outside probe, detecting 23-kb WT and 8-kb mutant bands. (C) Northern blot analysis of total RNA extracted from the retina derived from WT, TRPM1+/−, and TRPM1−/− mice using cDNA probe derived from exons 3–9. (D–G) Immunostaining of WT and TRPM1−/− retinal sections at 1 M. The TRPM1-L signal in the INL of WT mouse retina disappeared in the TRPM1−/− mouse retina (D). Immunohistochemical analysis using antibodies to Chx10 [pan-BC nuclei marker (E)], Goα [ON BC dendrite marker (F)], and mGluR6 [ON BC dendrite tip marker (G)] showed no obvious difference between WT and TRPM1−/− mice retinas. PRL, photoreceptor layer; INL, inner nuclear layer; GCL, ganglion cell layer. (Scale bar: 50 μm.)

TRPM1–L Is Required for the Photoresponse of ON BCs.

To address a possible role of TRPM1 in ON BC function, we generated TRPM1 null mutant (TRPM1−/−) mice by targeted gene disruption (Fig. 2A). We used Southern blots to confirm the exons 4–6 deletion (Fig. 2B). Northern blot analysis showed that no substantial transcripts were detected in TRPM1−/− retinas (Fig. 2C). Although TRPM1-S is expressed in the skin, TRPM1−/− mice were indistinguishable from wild-type (WT) littermates in appearance, including coat color. In TRPM1−/− mice, immunoreactivity to TRPM1-L was essentially undetectable (Fig. 2D). In contrast, no substantial reduction of retinal BC markers including Chx10, Goα, and mGluR6 was observed in TRPM1−/− mouse retinas at 1 month (Fig. 2 E–G).

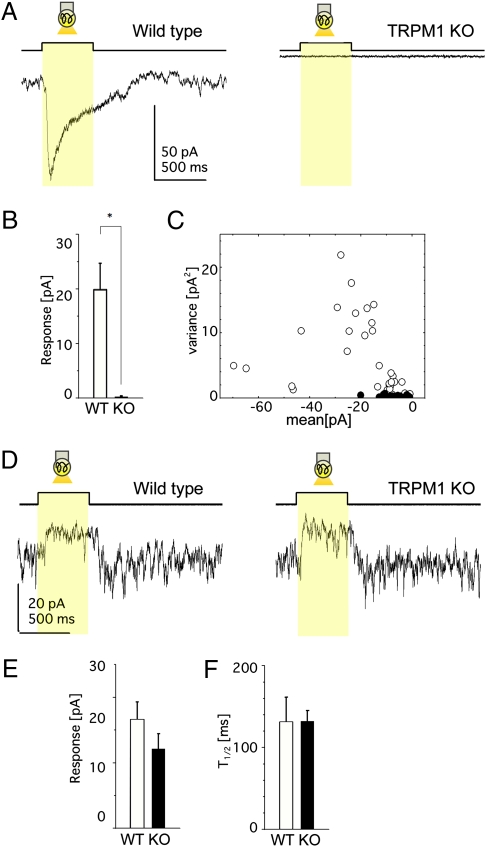

To examine whether TRPM1-L can function as a transduction cation channel in rod and cone ON BCs, we applied whole-cell recording techniques to BCs in mouse retinal slices (Fig. 3). Under the whole-cell voltage clamp, light stimulation induced an inward current in ON BCs of WT mice (Fig. 3A, WT), reflecting the opening of transduction cation channels via mGluR6 deactivation (11, 13, 24, 25). On the other hand, neither rod BCs nor cone ON BCs of TRPM1−/− mice evoked photoresponses (Fig. 3A, TRPM1 KO). Collected data showed significant differences in the amplitude of photoresponses between WT and TRPM1−/− mice (Fig. 3B). Membrane current fluctuations of ON BCs in the dark were much smaller in TRPM1−/− mice than in WT mice (Fig. 3A), suggesting that there are no functional transduction cation channels in ON BCs of TRPM1−/− mice (Fig. 3C). On the other hand, light stimulation of cone OFF BCs in both WT and TRPM1−/− mice evoked photoresponses (Fig. 3D). We detected no significant differences in either the amplitude of the light responses (Fig. 3E) or the time for half-maximal amplitude after the light was turned off (T1/2) (Fig. 3F).

Fig. 3.

TRPM1-L is essential for ON BC photoresponses. (A–C) Data from ON BCs in the retinal slice preparation. (A) Photoresponses of ON BCs from WT (Left) and TRPM1−/− (Right) mice (holding potential at –62 mV). Each trace illustrates the average of three responses. (B) Mean ± SEM of photoresponses from WT (15 cells, 12 mice) and TRPM1−/− (9 cells, 8 mice) mice. *, P < 0.05. (C) The variance against the mean (the leak current not subtracted) of the dark membrane current fluctuations obtained from WT (open circles: 34 traces, 15 cells) and TRPM1−/− (filled circles: 26 traces, 9 cells) mice. (D–F) Data from OFF BCs in the retinal slice preparation. (D) Photoresponses of OFF BCs from WT (Left) and TRPM1−/− (Right) mice under similar recording conditions as in A. Each trace illustrates the average of two responses. No significant difference in the response amplitude (WT, 5 cells; TRPM1−/−, 6 cells) (E) or in the time for half-maximal amplitude after the termination of light stimulation (T1/2) (WT, 5 cells; TRPM1−/−, 6 cells) (F).

Functional Coupling Between TRPM1-L and mGluR6.

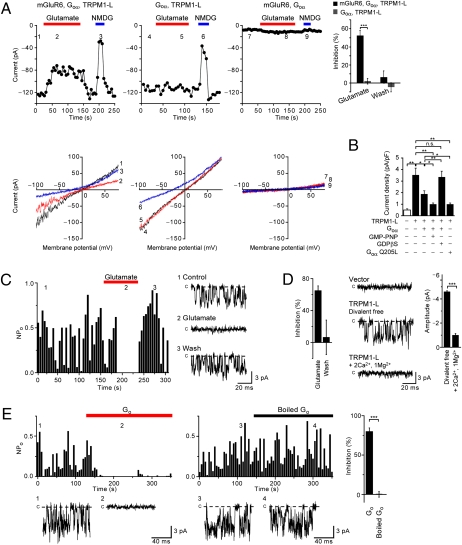

To examine whether or not TRPM1-L is modulated by mGluR6 activation, we measured ionic currents in TRPM1-L-trasnfected CHO cells under whole-cell voltage clamp. We measured the amplitude of the inward current at −100 mV, which was plotted against time to examine the effects of glutamate and N-methyl-D-glucamine (NMDG+), an impermeant cation. In the CHO cells expressing mGluR6, Goα, and TRPM1-L, constitutively active inward currents were observed, whereas in Goα-transfected CHO cells stably expressing mGluR6 but not TRPM1-L (n = 11), a whole-cell current was negligible (Fig. 4A). The I–V relationship of the inward currents was almost linear with a reversal potential (Vrev) of ∼0 mV (0.92 mV, n = 15), indicating that, like most TRP channels, TRPM1-L may be a nonselective cation channel (Fig. 4A). In fact, replacement of extracellular cations with NMDG+ resulted not only in the reduction of the current but also in a shift of Vrev toward hyperpolarizing potential (ΔVrev = −23.7 mV, n = 15) (Fig. 4A). Constitutively active currents were detected even by the replacement of extracellular cations with either Na+, K+, Ca2+, or Mg2+, supporting the idea that TRPM1-L is a constitutively active nonselective cation channel (26) (Fig. S3A). In CHO cells expressing mGluR6, Goα, and TRPM1-L, constitutively active cationic currents were suppressed by the addition of 1 mM glutamate to the bath solution (Fig. 4A). Although in CHO cells cotransfected with Goα and TRPM1-L, whole-cell currents with similar I–V relationships were detected, application of glutamate did not affect the whole-cell current (in 11 of 11 cells). A calculated average suppression ratio of inward current (Vh = −100 mV) by 1 mM glutamate administration was 52.7% (n = 15) in CHO cells expressing mGluR6, Goα, and TRPM1-L, whereas the average suppression ratio in CHO cells coexpressing Goα and TRPM1-L was 2.1% (n = 11) (Fig. 4A). The effects of glutamate were reversible (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

Functional coupling of TRPM1-L with mGluR6 is mediated by Go protein in CHO cells. (A) mGluR6 activation inhibits cationic currents by TRPM1-L in CHO cells. Effects of 1 mM glutamate and replacement of extracellular Na+ with NMDG+ on whole-cell currents recorded in cells expressing different combinations of constructs as indicated above each plot at −100 mV (Upper) in the 180-ms voltage ramp (applied every 5 s) from +80 mV to −100 mV (Vh = −60 mV) before (1, 4, 7) and during (2, 5, 8) glutamate application and replacement of extracellular Na+ with NMDG+ (3, 6, 9) (Lower). The bar graphs represent suppression ratios of currents at ≃100 mV during and after activation of mGluR6 in CHO cells expressing mGluR6, Goα, and TRPM1-L (n = 15) or Goα and TRPM1-L (n = 11). (B) Inhibitory effects of Goα constructs on Na+ currents via TRPM1-L (–60 mV). (C) Suppression of single TRPM1-L channel activity (NPO) at −60 mV by activation of mGluR6 in excised outside-out patches. The bar graph shows the averaged NPO suppression ratio (n = 10). (D) Extracellular divalent cations reduce the single-channel current amplitude of TRPM1-L in outside-out patches. The bar graph at the right represents average single TRPM1-L channel amplitudes in divalent cation-free (n = 29) or Ca2+- and Mg2+-containing (n = 11) solution. (E) Inhibition of NPO of TRPM1-L by intracellular treatment of Go protein in inside-out patches. The bar graphs show averaged NPO suppression ratio by intracellular application of activated (n = 16) and boiled (n = 14) Go protein. Data represent the mean ± SEM. n.s., not significant. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

We investigated the effect of Go activation on the TRPM1-L current by measuring a whole-cell current in TRPM1-expressing CHO cells transfected either with wild-type of Goα (Goα) or a constitutively active mutant of Goα (Goα-Q205L). Analysis of the reduced currents upon replacement of extracellular Na+ with NMDG+ demonstrated that the current density obtained in TRPM1-L-transfected cells (3.53 pA/pF, n = 8) was considerably larger than that in vector-transfected control cells (0.50 pA/pF, n = 6) and that in TRPM-L- and Goα-cotransfected cells (1.89 pA/pF, n = 14) (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, intracellular application of GMP-PNP (1 mM), an unhydrolyzable analog of GTP, to TRPM1-L- and Goα-cotransfected cells resulted in a remarkable decrease of current density (1.00 pA/pF, n = 22), whereas intracellular application of GDPβS (1 mM), an unhydrolyzable analog of GDP, restored the current density to a level comparable to that in TRPM1-L-transfected cells (3.35 pA/pF, n = 9) (Fig. 4B). We also observed suppression of current density in TRPM1-L- and Goα-Q205L-cotransfected cells to a level comparable to that in TRPM1-L- and Goα-cotransfected cells intracellularly perfused with GMP-PNP (1.00 pA/pF, n = 36) (Fig. 4B). We confirmed that the expression level of TRPM1-L protein was not significantly affected by Goα expression with a pull-down assay of biotinylated membrane proteins (Fig. S3B). These results suggest that TRPM1-L channel function is negatively regulated by Go activation.

To confirm that TRPM1-L channel activity is regulated via Go proteins in the mGluR6 signal cascade, we performed single-channel recordings in the outside-out patch mode (Fig. 4C). In mGluR6-stably expressed CHO cells transfected with both TRPM1-L and Goα, constitutively active currents, whose single-channel conductance was 76.70 pS and open probability (NPO) was 0.48, were obtained in 41 cells out of 129 cells. These currents showed a Vrev of ∼0 mV (6.86 mV, n = 21). By contrast, similar single-channel currents were absent in cells expressing both mGluR6 and Goα but not TRPM1-L (n = 32) (Fig. S3C). We next examined whether these single-channel currents were regulated by the mGluR6 signal cascade. Analyses of time-dependent changes in NPo demonstrated a reversible suppression of NPo by 1 mM glutamate application (in 7 of 16 cells) (Fig. 4C). The average NPo suppression ratio was 65.0% (n = 7). The average amplitude of single-channel currents in TRPM1-L-transfected cells was −4.60 pA (n = 30), and that in 2 mM Ca2+- and 1 mM Mg2+-containing solution was significantly reduced to −1.01 pA (n = 10) (Fig. 4D).

To demonstrate more directly that TRPM1-L is regulated by Go protein, the effect of addition of the purified Go protein from the intracellular side on TRPM1-L activity was tested in the excised inside-out patch mode (Fig. 4E). We confirmed that the purified Go protein contains mainly Goα by Western blotting and silver staining (27, 28). In TRPM1-L-transfected cells, we detected similar single-channel currents (−4.60 pA, n = 43) as observed in Fig. 4C. Application of the purified Go protein gradually but strongly suppressed NPo (by 80.2%, in 16 of 16 cells) within 60 s, whereas administration of heat-denatured Go protein failed to suppress NPo (by 0.6%, in 14 of 14 cells) with GMP-PNP (Fig. 4E).

Discussion

Recently, it was suggested that TRP channels have a possible function in retinal BCs (22, 23). Bellone et al. (22) reported that TRPM1 may be responsible for horse congenital stationary night blindness (CSNB), from their observation that TRPM1 expression was decreased in CSNB (LP/LP) Appaloosa horses among five genes within the LP candidate region of the equine genome. Although mutations of TRPM1 in LP/LP horse were not identified, they even speculated that TRPM1 might be a transduction cation channel in retinal ON BCs. Shen et al. (23) investigated whether or not TRPV1 is a retinal ON BC transduction channel. ON BCs responded to TRPV1 agonists; however, photoresponses of ON BCs in TRPV1−/− mice were normal. Based on the absence of the dark-adapted ERG b-wave in the Trpm1tm1Lex mutant mouse, they speculated that ON BC function would be disrupted in these mice (23). We also examined the optokinetic responses (OKRs) and electroretinograms (ERGs) of 2-month-old WT and TRPM1−/− mice. Optokinetic deficiencies similar to those of mice lacking mGluR6 (29) were observed in TRPM1−/− mice. It is interesting that the OFF pathway did not compensate for the loss of the ON pathway in spatial processing. In contrast to this result, patients lacking mGluR6 receptors were behaviorally normal, suggesting some OFF pathway redundancy and/or compensation (30). The ERG b-wave, originating mainly from the rod BCs, in TRPM1−/− mice was not present. In the light-adapted state, the ERG b-wave was severely depressed or absent leaving only the ERG a-wave in the TRPM1−/− mouse (21). These ERG results suggested that both the function of rod and cone BCs, and the signal transmission from rod and cone photoreceptors to BCs were severely impaired in TRPM1−/− mice.

In this study, we show that TRPM1-L is essential for the light-evoked response of ON BCs and that TRPM1-L meets the criteria for the transduction cation channel as follows. (i) Immunohistochemical experiments revealed that TRPM1-L is specifically expressed in ON BCs, especially at the dendritic tips in colocalization with mGluR6. (ii) Retinal slice patch recordings from the TRPM1−/− mice show that photoresponses disappear in ON BCs but remain intact in OFF BCs. Other cellular properties of the ON BCs were unaffected in the TRPM1−/− mice (e.g., leak and calcium currents), suggesting that compensatory changes or general cellular malfunction did not occur in TRPM1−/− mice. (iii) Application of patch-clamp techniques to the TRPM1-expressing cells found that TRPM1-L is a nonselective cation channel and that the TRPM1-L activity is negatively regulated by the glutamate-activated mGluR6–Goα signaling cascade. Thus, we clearly demonstrate that TRPM1-L is a component of the transduction cation channel in the mGluR6 cascade of retinal ON BCs.

Materials and Methods

Molecular Cloning and Construction of Mouse TRPM1-L Expression Vector.

We screened the UniGene databases by Digital Differential Display (DDD) and found UniGene Cluster Mm.58616, which contains ESTs (expressed sequence tags) enriched in the eye and the skin. Represented EST sequences encoded TRPM1-S (melastatin, trpm1 short form). We screened a mouse P0-P3 retinal cDNA library using a 1,703-bp fragment of the mouse melastatin cDNA (283-1991 bp of #AF047714) and isolated the mouse TRPM1 long form (TRPM1-L). TRPM1-L cDNA was subcloned into a modified pCAGGS vector (31).

Immunohistochemistry.

Mouse eye cups were fixed, cryoprotected, embedded, frozen, and sectioned 20 μm thick. For immunostaining, we used the following primary antibodies: anti-Goα antibody (mouse monoclonal, Chemicon, #MAB3073), anti-bassoon antibody (mouse monoclonal, Stressgen, #VAM-PS003), and anti-Chx10 antibody [rabbit polyclonal, our production (32)].

Antibody Production.

A cDNA encoding a C-terminal portion of mouse TRPM1-L (residues 1554–1622 aa, TRPM1-L-C) was subcloned into pGEX4T-1 (Amersham). We confirmed, either by immunohistochemistry or Western blotting, that the signals detected by this antibody in the retina disappeared in TRPM1−/− mice (Fig. S1). The antibody against mGluR6 was raised in Guinea Pigs with synthetic peptides [KKTSTMAAPPKSENSEDAK] (853-871, GenBank #NP_775548.2). We confirmed that the signals detected by this antibody in the retina disappeared in mGluR6−/− mice and by preincubation with 5.7 μg/mL synthetic peptides as molar ratio 1:100 with antibody.

Generation of TRPM1-Null Mutant Mice.

We deleted exons 4–6 of the TRPM1 gene to produce the targeting construct for the targeted gene disruption of TRPM1. The linearized targeting construct was transfected into TC1 embryonic stem cell line (33).

Retinal Slice Preparation and Recordings.

Adult (postnatal day <28) 129Sv/Ev (WT) mice were dark adapted for ≈20 min, and retinal slices were prepared as described in ref. 34. At the end of perforated patch recordings, the patch membrane was ruptured to introduce Lucifer yellow from the patch pipette into the cell and then its morphology was examined by epifluorescence microscopy (35–37). The extracellular solution contained 120 mM NaCl, 3.1 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgSO4, 23 mM NaHCO3, 0.5 mM KH2PO4, and 6 mM D-glucose (pH adjusted to 7.6 with 95% O2/5% CO2 at 36°C). The pipette solution for recordings consisted of 105 mM CsCH3SO3, 0.5 mM CaCl2, 5 mM EGTA, 20 mM Hepes, 10 mM TEA-Cl, 5.5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM ATP disodium salt, 0.5 mM GTP disodium salt, and 0.25% Lucifer yellow dipotassium salt (pH adjusted to 7.6 with CsOH). For perforated patch recordings, 0.5 mg/mL amphotericin B (Sigma) was added to the pipette solution. The retinal slice was diffusely illuminated (2.3 × 104 photons·μm−2·s−1) by a light-emitting diode (emission maximum at 520 nm) from underneath the recording chamber.

Recombinant Expression and Current Recording in CHO Cells.

Whole-cell and patch recordings were performed on CHO cells at room temperature (22-25°C) with an EPC-9 (Heka Electronic) or Axopatch 200B (Axon Instruments) patch-clamp amplifier as described in ref. 24. For whole-cell recordings, the Na+-based bath solution contained 145 mM NaCl, 10 mM Hepes, 10 mM D-glucose, and 10 mM D-mannitol (pH adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH). The pipette solution contained 145 mM CsCl, 2.86 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 5 mM EGTA, and 10 mM Hepes (pH adjusted to 7.4 with CsOH). The free Ca2+ concentration of this solution was calculated to be 200 nM as computed with Maxchelator (38). The suppression ratio (%) in Fig. 4A was calculated according to the following equation: suppression ratio (%) = 100 × {1 − (IGlu − INMDG)/(ICtl − INMDG)}, where ICtl and IGlu are whole-cell current observed before and during 1 mM glutamate application at −100 mV, respectively. INMDG represents the current observed during NMDG+-replacement of extracellular cations with NMDG+. Single-channel recordings were performed in the excised inside-out or outside-out configuration. Activity plots of open probability (NPO; N is the number of channels in the patch and PO is the single-channel open probability) recorded from inside-out and outside-out patches, as calculated for a series of 500-ms test pulses to −60 mV and plotted as a vertical bar on the activity histogram. The NPO of single channels was calculated by dividing the total time spent in the open state by the total time of continuous recording (500 ms) in the patches containing active channels. The amplitude of single-channel currents was measured as the peak-to-peak distance in Gaussian fits of the amplitude histogram. For outside-out recordings, the extracellular side was exposed to a bath solution containing 140 mM KCl, 10 mM Hepes, 5 mM D-glucose, and 25 mM D-mannitol (pH adjusted to 7.4 with KOH). To observe the effects of extracellular divalent cations, 2 mM CaCl2 and 1 mM MgCl2 were added to bath solution. The pipette solution was composed of 145 mM CsCl, 2.86 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 5 mM EGTA, and 10 mM Hepes (pH adjusted to 7.4 with CsOH). The suppression ratio (%) in Fig. 4C was calculated according to the following equation: suppression ratio (%) = 100 × {1 − NPO Glu/NPO Ctl}, where NPO Ctl and NPO Glu indicate mean NPO of six traces obtained before and during 1 mM glutamate application, respectively. For inside-out recordings, the intracellular side was exposed to a Cs+-based bath solution consisting of 145 mM CsCl, 2.86 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 5 mM EGTA, and 10 mM Hepes (pH adjusted to 7.4 with CsOH), and an extracellular (pipette) solution that contained 140 mM KCl, 10 mM Hepes, 5 mM D-glucose, and 25 mM D-mannitol (pH adjusted to 7.4 with KOH) was used. Purified Go protein was activated by 100 nM GMP-PNP for 30 min at 4°C (Go) or denaturated by boiling for 10 min at 95°C (Boiled Go) before use. The suppression ratio (%) in Fig. 4E was calculated according to the following equation: suppression ratio (%) = 100 × {1 − NPO Go/NPO Ctl}, where NPO Ctl and NPO Go indicate mean NPO of six traces obtained before and during activated or boiled Go protein application.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. M. Okazawa, N. Wada, T. Doi, M. Wakamori, S. Kiyonaka, N. Kajimura, and J. Usukura for technical advice and M. Kadowaki, H. Tsujii, Y. Kawakami, M. Joukan, K. Sone, and S. Kennedy for technical assistance. This work was supported by a Grant for Molecular Brain Science (to T.F.), Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) (to T.F.) and (C) (to C.K.) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan, PREST program from Japan Science and Technology Agency (to C.K.), and grants from the Takeda Science Foundation, the Uehara Memorial Foundation, and the Mochida Memorial Foundation (to T.F.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Database deposition: The nucleotide sequence for the mouse TRPM1-L gene has been deposited in the GenBank database (accession no. AY180104).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0912730107/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Dowling JE. The Retina: An Approachable Part of the Brain. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard Univ Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeVries SH, Baylor DA. Synaptic circuitry of the retina and olfactory bulb. Cell. 1993;72(Suppl):139–149. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(05)80033-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nomura A, et al. Developmentally regulated postsynaptic localization of a metabotropic glutamate receptor in rat rod bipolar cells. Cell. 1994;77:361–369. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90151-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haverkamp S, Grünert U, Wässle H. Localization of kainate receptors at the cone pedicles of the primate retina. J Comp Neurol. 2001;436:471–486. doi: 10.1002/cne.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morigiwa K, Vardi N. Differential expression of ionotropic glutamate receptor subunits in the outer retina. J Comp Neurol. 1999;405:173–184. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19990308)405:2<173::aid-cne3>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de la Villa P, Kurahashi T, Kaneko A. L-glutamate-induced responses and cGMP-activated channels in three subtypes of retinal bipolar cells dissociated from the cat. J Neurosci. 1995;15:3571–3582. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-05-03571.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Masu M, et al. Specific deficit of the ON response in visual transmission by targeted disruption of the mGluR6 gene. Cell. 1995;80:757–765. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90354-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Euler T, Schneider H, Wässle H. Glutamate responses of bipolar cells in a slice preparation of the rat retina. J Neurosci. 1996;16:2934–2944. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-09-02934.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weng K, et al. Functional coupling of a human retinal metabotropic glutamate receptor (hmGluR6) to bovine rod transducin and rat Go in an in vitro reconstitution system. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:33100–33104. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.52.33100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vardi N. Alpha subunit of Go localizes in the dendritic tips of ON bipolar cells. J Comp Neurol. 1998;395:43–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nawy S. The metabotropic receptor mGluR6 may signal through G(o), but not phosphodiesterase, in retinal bipolar cells. J Neurosci. 1999;19:2938–2944. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-08-02938.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dhingra A, et al. Light response of retinal ON bipolar cells requires a specific splice variant of Galpha(o) J Neurosci. 2002;22:4878–4884. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-12-04878.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shiells RA, Falk G. Glutamate receptors of rod bipolar cells are linked to a cyclic GMP cascade via a G-protein. Proc Biol Sci. 1990;242:91–94. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1990.0109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramsey IS, Delling M, Clapham DE. An introduction to TRP channels. Annu Rev Physiol. 2006;68:619–647. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.68.040204.100431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clapham DE. TRP channels as cellular sensors. Nature. 2003;426:517–524. doi: 10.1038/nature02196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Owsianik G, Talavera K, Voets T, Nilius B. Permeation and selectivity of TRP channels. Annu Rev Physiol. 2006;68:685–717. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.68.040204.101406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Montell C. Physiology, phylogeny, and functions of the TRP superfamily of cation channels. Sci STKE. 2001;2001:re1. doi: 10.1126/stke.2001.90.re1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duncan LM, et al. Down-regulation of the novel gene melastatin correlates with potential for melanoma metastasis. Cancer Res. 1998;58:1515–1520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kraft R, Harteneck C. The mammalian melastatin-related transient receptor potential cation channels: an overview. Pflugers Arch. 2005;451:204–211. doi: 10.1007/s00424-005-1428-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hunter JJ, et al. Chromosomal localization and genomic characterization of the mouse melastatin gene (Mlsn1) Genomics. 1998;54:116–123. doi: 10.1006/geno.1998.5549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koike C, et al. The functional analysis of TRPM1 in retinal bipolar cells. Neurosci Res. 2007;58(Suppl 1):S41. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bellone RR, et al. Differential gene expression of TRPM1, the potential cause of congenital stationary night blindness and coat spotting patterns (LP) in the Appaloosa horse (Equus caballus) Genetics. 2008;179:1861–1870. doi: 10.1534/genetics.108.088807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shen Y, et al. A transient receptor potential-like channel mediates synaptic transmission in rod bipolar cells. J Neurosci. 2009;29:6088–6093. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0132-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nawy S, Jahr CE. Suppression by glutamate of cGMP-activated conductance in retinal bipolar cells. Nature. 1990;346:269–271. doi: 10.1038/346269a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilson M, Tessier-Lavigne M, Attwell D. Noise analysis predicts at least four states for channels closed by glutamate. Biophys J. 1987;52:955–960. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(87)83288-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu XZ, Moebius F, Gill DL, Montell C. Regulation of melastatin, a TRP-related protein, through interaction with a cytoplasmic isoform. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:10692–10697. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191360198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Asano T, Semba R, Ogasawara N, Kato K. Highly sensitive immunoassay for the alpha subunit of the GTP-binding protein go and its regional distribution in bovine brain. J Neurochem. 1987;48:1617–1623. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1987.tb05710.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saitoh O, Kubo Y, Miyatani Y, Asano T, Nakata H. RGS8 accelerates G-protein-mediated modulation of K+ currents. Nature. 1997;390:525–529. doi: 10.1038/37385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ueda Y, Iwakabe H, Masu M, Suzuki M, Nakanishi S. The mGluR6 5′ upstream transgene sequence directs a cell-specific and developmentally regulated expression in retinal rod and ON-type cone bipolar cells. J Neurosci. 1997;17:3014–3023. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-09-03014.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dryja TP, et al. Night blindness and abnormal cone electroretinogram ON responses in patients with mutations in the GRM6 gene encoding mGluR6. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:4884–4889. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501233102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Niwa H, Yamamura K, Miyazaki J. Efficient selection for high-expression transfectants with a novel eukaryotic vector. Gene. 1991;108:193–199. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90434-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koike C, et al. Function of atypical protein kinase C lambda in differentiating photoreceptors is required for proper lamination of mouse retina. J Neurosci. 2005;25:10290–10298. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3657-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Deng C, Wynshaw-Boris A, Zhou F, Kuo A, Leder P. Fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 is a negative regulator of bone growth. Cell. 1996;84:911–921. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81069-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matsui K, Hasegawa J, Tachibana M. Modulation of excitatory synaptic transmission by GABA(C) receptor-mediated feedback in the mouse inner retina. J Neurophysiol. 2001;86:2285–2298. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.86.5.2285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ghosh KK, Bujan S, Haverkamp S, Feigenspan A, Wässle H. Types of bipolar cells in the mouse retina. J Comp Neurol. 2004;469:70–82. doi: 10.1002/cne.10985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Berntson A, Taylor WR. Response characteristics and receptive field widths of on-bipolar cells in the mouse retina. J Physiol. 2000;524:879–889. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00879.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Euler T, Masland RH. Light-evoked responses of bipolar cells in a mammalian retina. J Neurophysiol. 2000;83:1817–1829. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.83.4.1817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Berlin JR, Bassani JW, Bers DM. Intrinsic cytosolic calcium buffering properties of single rat cardiac myocytes. Biophys J. 1994;67:1775–1787. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80652-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.