Abstract

In Escherichia coli, programmed cell death is mediated through “addiction modules” consisting of two genes; the product of one gene is long-lived and toxic, whereas the product of the other is short-lived and antagonizes the toxic effect. Here we show that the product of λrexB, one of the few genes expressed in the lysogenic state of bacteriophage λ, prevents cell death directed by each of two addiction modules, phd-doc of plasmid prophage P1 and the rel mazEF of E. coli, which is induced by the signal molecule guanosine 3′,5′-bispyrophosphate (ppGpp) and thus by amino acid starvation. λRexB inhibits the degradation of the antitoxic labile components Phd and MazE of these systems, which are substrates of ClpP proteases. We present a model for this anti-cell death effect of λRexB through its action on the ClpP proteolytic subunit. We also propose that the λrex operon has an additional function to the well known phenomenon of exclusion of other phages; it can prevent the death of lysogenized cells under conditions of nutrient starvation. Thus, the rex operon may be considered as the “survival operon” of phage λ.

Keywords: addiction modules, programmed cell death, protein degradation

The rex operon of bacteriophage λ is responsible for the exclusion of several unrelated phages (for reviews see refs. 1–4). The first described Rex function was the exclusion by the λ prophage of the development of phage T4rII mutants. In fact, the name rex comes from rII exclusion. The phenomenon of T4rII exclusion has a special status in the history of molecular biology and genetics and has been compared with that of the gene causing Mendel’s rough and smooth peas (2). The rex exclusion function requires the products of two adjacent genes, rexA and rexB (5, 6). Parma et al. (3) have shown that λRexB is an inner-membrane protein with four transmembrane domains. They have suggested that λRexB forms ion channels that are activated by λRexA in response to a signal generated during lytic growth and thereby cause cell death. The genes rexA and rexB, together with the cI repressor gene, are located in the immunity region of λ (for review, see ref. 1). The genes rexA and rexB can be expressed coordinately with the cI repressor gene from promoters pRM and pRE (5, 7, 8). However, there is a third promoter, pLIT, that overlaps the region encoding the carboxyl terminus of rexA. Transcription from pLIT results in the synthesis of the lit mRNA, which permits the expression of rexB without that of rexA (5, 7, 9). This shift from coordinate to discoordinate expression of rexB and rexA implies that λrexB may have another function independent of that of rexA (3, 5).

We previously reported (4) another function for the product of λrexB that prevents the in vivo degradation of the short-lived protein λO, known to be involved in λ DNA replication. We suggested that λRexB may act as an inhibitor of the Escherichia coli protease involved in λO degradation. The protease responsible for λO degradation has since been characterized as the ATP-dependent serine protease ClpPX (10, 11). The ClpP proteases form a family in which a proteolytic subunit, ClpP, can associate with at least one of the specificity subunit—ClpA (12–14) or ClpX (10, 11, 15)—that bears the ATPase activity. Besides λO, only a few substrates of the ClpP proteases have been identified. Among these are the short-lived proteins of two “addiction modules” that are subjected to degradation by two different ATP-dependent ClpP proteases (see below).

Addiction modules consist of two genes. In most addiction modules, the product of one gene is long-lived and toxic, whereas the product of the other is short-lived and antagonizes the toxic polypeptide. The cells are addicted to the presence of the short-lived polypeptide because its de novo synthesis is essential for cell survival. Until recently, addiction modules have been found mainly in a number of E. coli extrachromosomal elements (16, 17), among which is the phd-doc module of plasmid prophage P1 (18, 19). Phd serves to prevent host death when the prophage is retained; should the retention mechanism fail, Doc causes death on curing. Doc acts as a cell toxin to which the short-lived Phd protein is an antidote. Phd itself is degraded by the ClpPX serine protease (19). The other member of the ClpP family, the ClpPA serine protease, is responsible for the degradation of protein MazE, the short-lived antidote of another addiction module, mazEF, which we discovered recently (20). This pair of genes also was called chpA (21). The mazEF addiction module consists of two genes, mazE and mazF, located downstream from the relA gene in the rel operon (22). In our work, we have found that MazF is toxic and long-lived, MazE is antitoxic and short-lived, and they are coexpressed. Moreover, the mazEF system has a unique property: its expression is regulated by guanosine 3′,5′-bispyrophosphate (ppGpp), which is synthesized by the RelA protein under conditions of amino acid starvation. These properties suggest that the mazEF addiction module may be responsible for programmed cell death in starving cultures of E. coli (20). As generally viewed for extrachromosomal elements, the addiction module renders the bacterial host addicted to the continued presence of the “disposable” genetic element, the loss of which causes cell death (17). The new concept for the chromosomal addiction module mazEF is that the continued expression of this system is required to prevent cell death (20).

Here we show that λRexB, which prevents the degradation of the short-lived protein λO, acts similarly on two ClpP degradation systems belonging to two separate addiction modules, the short-lived Phd protein of plasmid prophage P1, which is a substrate for ClpPX, and the short-lived MazE protein of the E. coli rel operon, which is a substrate for ClpPA. Furthermore, λRexB prevents the killing mediated by these two addiction modules. Our results suggest that λRexB interferes with the action of the ClpP proteolytic subunit of the ClpP proteases and thereby prevents programmed cell death in E. coli.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials and Media.

[35S]Methionine (>800 Ci/mmol; 1 Ci = 37 GBq) was obtained from Amersham. Serine hydroxamate was obtained from Sigma. Antibodies to the addiction protein Phd of plasmid prophage P1 were kindly provided by M. Yarmolinsky (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). Bacteria were grown in M9 medium with a mixture of amino acids (20 μg/ml each) except methionine or in Luria–Bertani (LB) medium (23). Plasmid-carrying strains were grown in media containing ampicillin (100 μg/ml), spectinomycin (100 μg/ml), chloramphenicol (50 μg/ml), or kanamycin (25 μg/ml).

Bacterial Strains and Plasmids.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this work and their sources are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Description or relevant genotype | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli strain | ||

| MC4100 | araD139 Δ(argF-lac)205 flbB5301 ptsF25 rpsL150 deoC1 relA1 | 24 |

| XL1-Blue | recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 hsdR17 supE relA1 lac [F′ proAB lacIqZΔM15 Tn10(TetR)] | Stratagene |

| JC7623(λ) | recBCsbcBC(λ) | 25; A. Cohen |

| MC4100lacIq | By conjugation from XL1-Blue | This study |

| SG22098 | clpP∷cat in MC4100 background | 13; S. Gottesman |

| MC4100ΔmazEF | A ΔmazEF derivative of MC4100 | 20 |

| MC4100(λ) | MC4100 lysogenized with λ | This study |

| MC4100(λrexB∷Ω) | MC4100 lysogenized with λrexB∷Ω | This study |

| MC4100(λΔBamΔH1) | MC4100 lysogenized with λΔBamΔH1 | 20 |

| MC4100relA+ | A relA+ derivative of MC4100 | This study |

| MC4100relA+ΔmazEF | A relA+ derivative of MC4100ΔmazEF | This study |

| MC4100relA+(λ) | MC4100relA+ lysogenized with λ | This study |

| MC4100relA+(λrexB∷Ω) | MC4100relA+ lysogenized with λrexB∷Ω | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pGB2 | pSC101-based vector, SpcR/SmR | 26 |

| pGB2ts | pGB2 derivative, thermo-sensitive for replication; SpcR/SmR | 27; M. Yarmolinsky |

| pGB2ts∷phd-doc | Derivative of pGB2ts expressing phd and doc; SpcR/SmR | 18; M. Yarmolinsky |

| pHAL20 | pKK233-3 derivative carrying phd-doc under ptac; AmpR | M. Yarmolinsky |

| pALS13 | pBR322 derivative carrying a truncated relA gene under ptac and a lacIq; AmpR | 28, 29 |

| pRLM74 | pRLM74 carries the 1.5kb AluI fragment of λ which carries λrexB; AmpR | 4; M. McMacken |

| pRS2UAG | pKC30 derivative carrying a UAG mutation in λrexB at position 36231-36233 of λ DNA (31); AmpR | 4 |

| pRS2UAA | pKC30 derivative carrying a UAA mutation in λrexB at position 36231-36233 of λ DNA (31); AmpR | 4 |

| pRS10 | pBR322 derivative carrying λrexB under the pLJT promoter; AmpR, λrexB was subcloned from pRLM74 | This study |

| pRS11 | pBR322 carrying λrexBUAG subcloned from pRS2UAG; AmpR | This study |

| pRS12 | pBR322 carrying λrexBUAA subcloned from pRS2UAA; AmpR | This study |

| pLDG1 | pSU-2718 derivative carrying λrexB under the pLJT promoter; CmR | 4 |

| pLGD1∷Ω | pLGD1 carrying the omega interposon in the λrexB gene | This study |

| pRS14 | pSU-2718 carrying λrexBUAA subcloned from pRS2UAA; CmR | This study |

| pRS15 | pGB2 carrying λrexB under pLJT; SpcR/StrR; λrexB was subcloned from pRLM74 | This study |

| pRSE | pBR322 derivative carrying mazE under λpL; AmpR | 20 |

| pRSE1 | pRSE carrying λrexB under pLJT promoter; AmpR; λrexB was subcloned from pRLM74 | This study |

| pAAC | An E. coli-Streptomyces shuttle vector carrying the omega interposen aacC4 gene confering gentamicin resistance | 30 |

| pHG335 | pKK233-3 derivative carrying λcII under ptac and lacIq; AmpR | A. Oppenheim |

Construction of a λrexB∷Ω Insertion Mutation in a λ Lysogen.

λrexB located on pLDG1(Table 1) was inactivated by inserting the ω interposon, which carries the aacC4 gene conferring gentamicin resistance (30). We inserted this ω cassette into the unique NdeI site (after nucleotide 36,113) of λrexB (31). The insertion of the ω cassette was verified by testing for gentamicin resistance and by DNA sequencing. The constructed plasmid bearing λrexB∷Ω, which we called pLDG1∷Ω (Table 1), was then transferred by using recombination to E. coli strain JC7623(λ). λrexB∷Ω lysogens were selected by their resistance to gentamicin. A λrexB∷Ω lysate was used to lysogenize MC4100, and lysogenization was confirmed by using standard procedures (23).

Cloning Procedures.

All recombinant DNA manipulations were carried out by using standard procedures (32). Restriction enzymes and other enzymes used in the recombinant DNA experiments were obtained from New England Biolabs.

ppGpp Induction by a Truncated relA Gene.

Strains were transformed with pALS13 carrying a truncated relA gene under the inducible promoter ptac. They were then grown overnight in LB medium at 30°C to mid-logarithmic phase (OD600 ≈0.4) and shifted to 42°C for 10 min. Isopropyl β-d-thiogalactoside (IPTG) was added to a final concentration of 1 mM for 10 min.

Amino Acid Starvation with Serine Hydroxamate.

Cells grown overnight in LB medium were diluted 1:10 and were again grown in LB at 30°C to mid-logarithmic phase and shifted to 42°C for 10 min. Freshly prepared serine hydroxamate was added to a final concentration of 2.5 mg/ml for 10 min.

RESULTS

λRexB Prevents the Postsegregational Killing Effect Encoded by the P1 Addiction Module.

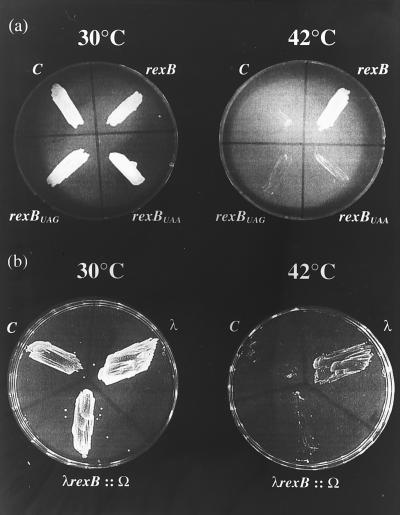

We used plasmid pGB2ts∷phd-doc, a temperature-sensitive vector, for replication carrying phd and doc of the P1 addiction module (18). As previously reported (19) and as confirmed here, cells carrying this plasmid survive at 30°C. At 42°C, however, the vector is lost and wild-type E. coli strain MC4100 cells die (Fig. 1). However, the clpP− and clpX− derivatives survive the loss of the vector (data not shown), probably because the degradation of the P1 antitoxin Phd by the ClpPX protease is prevented (19). In our studies on the effect of λRexB on the P1-addiction system, we used MC4100/pGB2ts:: phd-doc cells grown on LB agar plates at 30°C for 48 hr. They were then transformed with one of the following compatible plasmids: pRS10 (rexB), pRS11 (rexBUAG), or pRS12 (rexBUAA). As shown in Fig. 1a, at 42°C the cells survive when they carry the temperature-sensitive plasmid pGB2ts∷phd-doc together with the compatible plasmid carrying wild-type rexB, but they either die when rexB is absent (“C” quadrants in Fig. 1 images) or when the plasmid carries a nonsense mutation. These results suggest that λRexB prevents the degradation of the P1 Phd protein. As shown in Fig. 1b, at 42°C the cells survive when they are lysogenized with bacteriophage λ. However, they die when the λrexB gene in the lysogens is inactivated by the insertion of the ω interposon (λrexB∷Ω). The blocking of the function of P1 addiction module by λ prophage (immunity λ) was not observed previously (18). It seems, therefore, that the effectiveness of λRexB in preventing the action of the P1 addiction module depends on growth of the culture in solid medium (Fig. 1) rather than in broth (18). Alternatively, the λ prophage described previously (18) might have carried a λrexB defect.

Figure 1.

The effect of λRexB on the P1 addiction system. (a) E. coli strain MC4100 was transformed with pGB2ts or pGB2ts∷phd-doc, and transformants were selected after 48 hr at 30°C on LB agar plates supplemented with spectinomycin (100 μg/ml). The postsegregational killing effect of the phd-doc addiction module was studied by growing the bacteria on LB agar plates at 30°C or 42°C (19). Cells carrying pGB2ts grew at both 30°C and 42°C. On the other hand, wild-type cells carrying pGB2ts∷phd-doc also grew at 30°C but died at 42°C. After testing the P1 addiction system in this way, MC4100/pGB2ts∷phd-doc cells were transformed either with pBR322 (C for control), pRS10 (rexB), pRS11(rexBUAG), or pRS12(rexBUAA). The doubly transformed cells were selected at 30°C on plates containing spectinomycin and ampicillin and subsequently grown at either 30°C or 42°C on LB plates with ampicillin only for 24 hr. The results of last step are shown in a. In b, E. coli MC4100 was lysogenized with λ or with λrexB∷Ω. The cells were then transformed with pGB2ts∷phd-doc. b shows transformed E. coli grown on LB plates for 24 hr at either 30°C or 42°C.

λRexB Prevents the ClpPX-Dependent Degradation of P1 Phd Protein.

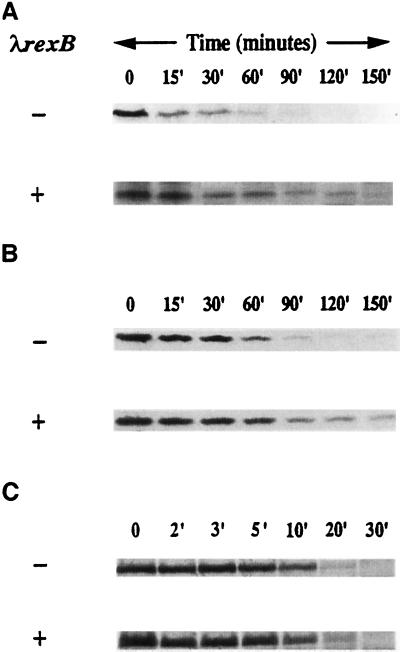

It was recently shown that the addiction protein Phd of plasmid prophage P1 is a substrate of the E. coli ClpPX protease (19). This finding enabled us to prove directly our assumption that λRexB prevents the postsegregational killing effect encoded by the P1 addiction module (Fig. 1) by preventing Phd degradation. We studied the effect of λRexB on the lifetime of Phd (Fig. 2A). As a source of Phd, we used plasmid pHAL20, which carries the phd-doc genes under the tac promoter. phd expression was induced by IPTG (in a lacIq strain), and a pulse–chase experiment was carried out at 41°C. Fig. 2A shows that Phd is degraded with a half-life of about 15 min, and this Phd degradation is partially prevented by λRexB. The protein is partially stabilized even during the period from 60 to 150 min. Furthermore, the stabilization effect of λrexB on Phd is manifested in trans (Fig. 2A). These results suggest that λRexB partially inhibits the ClpPX-dependent degradation of Phd protein of the P1 addiction module.

Figure 2.

The effect of λRexB on the in vivo stability of P1 Phd (A), E. coli MazE (B), and λCII (C). (A) Phd. A culture of E. coli MC4100 (lacIq) was transformed with pHAL20 that carries phd-doc under the control of ptac (upper) or together with the compatible plasmid pRS15 carrying λrexB under its own promoter pLIT (lower). Freshly transformed cells were grown in M9 medium overnight at 30°C, and then were diluted 1:10 and grown for another hour at 37°C. The cultures were shifted to 41°C, and Phd induction was carried out by the addition of 1 mM IPTG for 15 min. A pulse–chase experiment was done as described by us previously (20). Cells were lysed and immunoprecipitated with antibodies to Phd by using the procedure we described (4). The samples were applied to discontinuous (10–16%) SDS/PAGE gels and analyzed by autoradiography; Phd was identified according to its molecular weight and immunoprecipitation with antibodies directed against Phd. (B) MazE. E. coli MC4100 (λΔBamΔH1) carrying the temperature-sensitive λ repressor cI857 was transformed with pRSE carrying mazE under the control of the λpL promoter (upper) or with pRSE1 also carrying the λrexB gene under the control of its own promoter pLIT (lower). Cell growth, pulse–chase procedure, cell lysis, gel used, and MazE identification was performed as described (20). (C) λCII. A culture of E. coli MC4100 was transformed with pHG335 that carries λcII under the control of the ptac promoter (upper) or together with the compatible plasmid pRS15 carrying λrexB under its own promoter pLIT (lower). Freshly transformed cells were grown in M9 medium to mid-logarithmic phase at 30°C. The cultures were shifted to 42°C, and λCII induction was carried out by the addition of 1 mM IPTG for 15 min. Cells were labeled for 1 min and chased as described for P1 Phd above. Samples were precipitated with 10% trichloroacetic acid on ice, washed with cold acetone, resuspended in 60 mM Tris/2% SDS/0.7% 2-mercaptoethanol/10% glycerol/0.1% bromophenol blue, and applied to 15% SDS/PAGE gels. λCII position on the gel was determined as described for MazE above.

λRexB Prevents the ClpPA-Dependent Degradation of MazE Protein Encoded by the E. coli rel Addiction Module.

Recently, we found an E. coli chromosomally encoded substrate of the ATP-dependent ClpPA protease; this is MazE, the short-lived antitoxic protein of the E. coli rel addiction module (20). Here we studied the effect of λRexB on the lifetime of MazE in vivo. Fig. 2B shows that MazE is degraded with a half-life of about 30 min and that MazE degradation is partially prevented by the presence of the λrexB gene on the MazE-encoding plasmid. Here too, as in the case of PhD, MazE is partially stabilized even during the period from 60 to 150 min. In addition, the stabilization effect of λRexB on the MazE protein is seen in trans when the mazE and λrexB genes are carried on two different plasmids (data not shown). The pulse–chase experiment shown in Fig. 2B was carried out by using an E. coli strain lysogenized with λcI857. In this system, MazE, expressed from a multicopy plasmid and regulated by the strong promoter λpL, is degraded at 42°C. Though we assume that λRexB is expressed from the lysogen, it did not appear to protect MazE from degradation. Stabilization of MazE by λRexB is seen, however, when λrexB, like mazE, is carried on a multicopy plasmid. Thus, we have concluded that a certain balance between the amounts of E. coli MazE and λRexB proteins is required for stabilization to occur.

The results described in Fig. 2 A and B show that λRexB partially stabilizes Phd and MazE, which are substrates of the ATP-dependent ClpP proteolytic family. We further asked whether λRexB may stabilize a substrate of yet another ATP-dependent E. coli protease. As shown in Fig. 2C, this is not the case, because λRexB does not prevent the FtsH(HflB)-dependent degradation of λCII. Under our experimental conditions, λCII is degraded with a half-life of about 10 min. This degradation is unaffected by the presence of λrexB on a compatible plasmid.

λRexB Prevents E. coli mazEF-Mediated Cell Death.

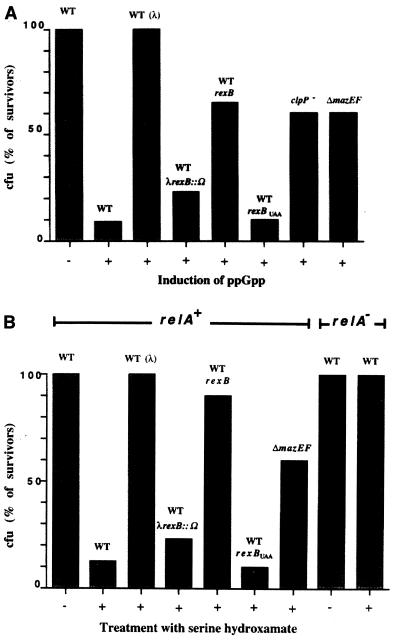

Finally, we asked whether λRexB, through its stabilization of MazE, may prevent the mazEF-mediated cell death induced by ppGpp (20). As before (28), we modulated the cellular level of ppGpp by using an IPTG-inducible truncated relA gene. The results are summarized in Fig. 3A. As shown, only 10% of the cells survived after abrupt induction by ppGpp under our experimental conditions. This effect is mazEF-mediated and clpP-dependent; cell survival is increased to 60% when the strain is deleted for mazEF or mutated to clpP−. In the presence of a plasmid-carrying λrexB gene, however, up to 65% of the cells survived in the wild-type strain. We further found that the presence of λrexBUAA, a λrexB allele that carries an ochre mutation, does not prevent ppGpp toxicity. Thus, it seems that the product of λrexB is responsible for the significant (6-fold) decrease in cell killing. This conclusion was further confirmed in an E. coli strain lysogenized with phage λ. When lysogenized with wild-type λ, ppGpp toxicity was completely prevented (100%). However, ppGpp toxicity is not prevented in a λ lysogen in which rexB is inactivated by the insertion of the ω interposon.

Figure 3.

The effect of λRexB on the E. coli mazEF programmed cell death induced by ppGpp (A) and by amino acid starvation with serine hydroxamate (B). (A) The experiment includes E. coli strains MC4100, MC4100(λ), MC4100(λrexB∷Ω), MC4100/pLDG1 (carrying λrexB), MC4100/pRS14 (carrying λrexBUAA), MC4100 clpP∷cat (SG22098), and MC4100ΔmazEF. ppGpp induction was carried out by using truncated relA gene as described in Materials and Methods. (B) The experiments included the relA+ derivatives of E. coli strain MC4100, MC4100(λ), MC4100ΔmazEF, MC4100(λrexB∷Ω), MC4100/pLDG1 (carrying λrexB), and MC4100/pRS14 (carrying λrexBUAA). We included MC4100relA− as a control. Amino acid starvation was carried out by treating the cells with serine hydroxamate as described in Materials and Methods. In A and B, cell survival was measured by colony-forming ability, and the data presented are the mean of at least five independent experiments.

In a relA+ strain, but not in a relA− strain, the activation of the synthesis of ppGpp is governed by amino acid starvation that can be achieved by the application of the serine analogue serine hydroxamate (33). Here we used serine hydroxamate to examine the effect of amino acid starvation, and thereby ppGpp induction, on cell viability. The results are shown in Fig. 3B. As shown, in a relA+ derivative but not in a relA− derivative of strain MC4100, treatment with serine hydroxamate decreases cell survival to 10% under our experimental conditions. In other respects, the effect of serine hydroxamate on cell viability was similar to that of ppGpp induction, except for one difference (compare Fig. 3 A and B). λrexB on a plasmid protects better (90%) in cells treated with serine hydroxamate than in the ppGpp-induced cells (65%). The reason for this difference is not yet clear. Because in the serine hydroxamate system the protection by λrexB on a plasmid is similar to that of a λ lysogen, we assume that no other phage functions are involved in this protection. In addition, in a λ lysogen rexB completely prevents cell death, whereas only partial protection (60%) was observed in a ΔmazEF strain. This result suggests the existence of another ClpP-dependent chromosomal addiction module. A possible candidate is chpB (21). However, there is no evidence yet that the chpB module is inducible by either ppGpp or serine hydroxamate.

DISCUSSION

In previous work (4), we described an additional function for the product of the bacteriophage λ rexB gene—prevention of the in vivo degradation of the short-lived λ replication protein O , which is a substrate for the ClpPX protease (10, 11, 15). The results we have reported here show that the product of λrexB acts similarly on two other short-lived proteins that are degraded by proteases belonging to the ClpP family. One of these is the addiction protein Phd of plasmid prophage P1, which has recently been described as a substrate of the ClpPX protease (19). The stabilization of Phd by λrexB in vivo is shown here, both directly (Fig. 2A) and functionally: the presence of λrexB prevents the postsegregational killing effect encoded by P1 (Fig. 1). According to the results of our experiments, λrexB only partially affects Phd stabilization (Fig. 2A), whereas it completely antagonizes postsegregational killing (Fig. 1). Thus, it seems that even by partially preventing the degradation of Phd, λRexB can efficiently antagonize the toxic protein Doc encoded by P1 and thereby prevents host death on curing of the plasmid. The product of λrexB also prevents the in vivo degradation of the short-lived MazE protein (Fig. 2B). This protein is encoded by the mazE gene, which is located downstream from relA in the E. coli rel operon (22). We recently reported (20) that MazE is a substrate of the ClpPA protease. As in the case of Phd, the product of λrexB has only a partial stabilizing effect on MazE. However, as in the case of Phd, the stabilizing effect of MazE has functional consequences, preventing the rel mazEF-mediated cell death induced by ppGpp (Fig. 3). All of the experiments illustrated in Figs. 1–3 were carried out at elevated temperatures, because we observed that at high temperatures (41–42°C), both the killing effect of the phd-doc and mazEF systems and the degradation of Phd and MazE are increased (data not shown). This temperature dependency may be related to the heat-shock inducibility of ClpP (34).

Our result suggests that it is the presence of the product of λrexB, and not just the presence of the gene alone, that inhibits the in vivo degradation of the antitoxin proteins Phd and MazE. We base our assumption on two lines of evidence: (i) nonsense mutations in λrexB permit both the postsegregational killing by the phd-doc system (Fig. 1) and the ppGpp-induced killing mediated by the mazEF system (Fig. 3) and (ii) the stabilization effect of λrexB on Phd (Fig. 2A) and MazE (data not shown), as well as the anti-death action in both phd-doc and mazEF systems (Figs. 1 and 3), are manifested in trans.

λRexB and the E. coli ClpP Family of Proteases.

Our results show that λRexB prevents the degradation of proteins that are substrates of either the ClpPX protease (λO and P1 Phd) or the ClpPA protease (E. coli MazE). The ClpP proteases form a family in which the proteolytic subunit ClpP is associated with one of the subunits, ClpA or ClpX, each of which has its own specificity, as well as ATPase activity (see Introduction). In contrast, as shown in Fig. 2C, the degradation of the short-lived protein CII of bacteriophage λ is not prevented by the product of λrexB. λCII is degraded by the ATP-dependent protease FtsH (HflB; refs. 35–37). Therefore, our results suggest that λRexB specifically acts against the ClpP family of proteases and not as a general antagonist of ATP-dependent proteases.

How does λRexB inhibit the ClpP family of proteases? λRexB may interact either directly or indirectly with the proteolytic subunit of the ClpP protease or with either ClpA or ClpX, which are closely related (38). Alternatively, the λRexB protein itself may be degraded by the ClpP family of proteases. Thus, in excess it may competitively inhibit the degradation of other substrates of the ClpP family such as λO, Phd, and MazE. This assumption is supported by our experiments indicating that a balance between the amount of E. coli MazE and λRexB is required for the stabilization to occur (see Results). A similar competition model has recently been suggested (39) to explain the stabilization of λCII (40) and σ32 (41) by λCIII. In this case, λCII (36, 37) and σ32 (35), as well as λCIII (39), are substrates of the FtsH (HflB) protease.

λrexB as Anti-Cell Death Gene and its Role in the Life Cycle of Phage λ.

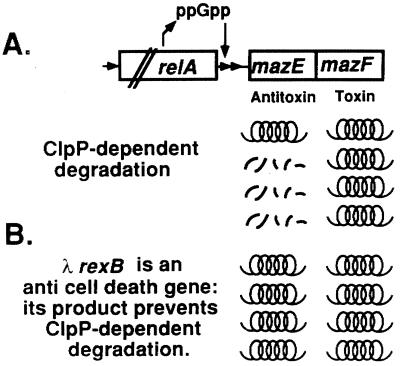

We have previously suggested (20) that the rel mazEF addiction module may be responsible for programmed cell death in starved E. coli cells (Fig. 4A). The results we report here further support this model, in which mazEF programmed cell death is induced by the signal molecule ppGpp (Fig. 3A), which in turn is regulated by amino acid starvation (Fig. 3B). Thus, the stabilization by λRexB of addiction proteins, which are substrates of the ClpP proteases (like MazE or PhD), suggests that the product of λrexB has an additional role previously undescribed, as an anti-cell death protein. Our model for the antagonistic effect of λRexB on rel mazEF programmed cell death is illustrated in Fig. 4B.

Figure 4.

A model for the E. coli rel mazEF-mediated cell death (A) and the anti-death effect of λRexB (B). (A) Under conditions of nutritional starvation, the level of ppGpp increases. During amino acid starvation, this increase in the cellular level of ppGpp is achieved by the interaction of the product of relA with uncharged tRNA (33). ppGpp inhibits the coexpression of mazE and mazF. MazF is a long-lived toxic protein, whereas MazE is an antitoxic labile protein that is degraded by the ClpPA protease. Therefore, when the cellular level of ppGpp is increased, the concentration of MazE is decreased more rapidly than that of MazF, and thus MazF can exert is toxic effect and cause cell death (20). (B) λRexB antagonizes the ClpP family of proteases. As a result, it inhibits the degradation of the antitoxic protein MazE and thereby prevents cell death.

rex as a Phage λ “Survival Operon.”

Most of our knowledge of the λrex operon and its role in the life cycle of bacteriophage λ has been based on research directed toward the understanding of the Rex exclusion phenomenon, in which the development of several unrelated phages is restricted by the combined action of the two λrex operon products, λRexA and λRexB (see Introduction). Rex exclusion-mediated cell death has been described as an altruistic behavior on the part of the infected cells; by committing suicide in response to infection, the bacterium may protect its nearest neighbors (3), which are likely to include its identical siblings. Accordingly, the role of the λrex operon in the life of phage λ is to trigger a cell-death program that enables λ to survive by winning in competition with other phages. Phenomenologically, it is similar to the strategy of exclusion used by many other parasitic DNA elements including prophages and plasmids (42). In this article, we have described another role for one of the genes, λrexB, of the rex operon for the life of λ. Its product, λRexB, prevents programmed cell death mediated by the E. coli chromosomal addiction module rel mazEF that is regulated by the signal molecule ppGpp and thus by amino acid starvation. The mazEF addiction module enables λ lysogens to survive under conditions of nutrient stress such as amino acid starvation (Fig. 3). Thus, the λrex operon may have at least two functions for the life cycle of λ, exclusion of other phages and prevention of death of the infected cells under conditions of nutrient starvation. The first function is permitted by the action of the products of both λrexA and λrexB and takes place only when a λ-lysogenized host is infected by another phage(s). The second function requires λRexB only and takes place in cells lysogenized with λ. Thus, the λrex operon can be considered the survival operon of phage λ. This operon ensures the survival in nature of phage λ, both in its struggle against infection by other phages (43) and in its dependence on the survival of its host even when λ itself is faced with conditions of nutrient stress.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. M. Yarmolinsky for kindly supplying us with bacterial strains plasmids and antibodies against Phd protein. We thank Dr. S. Gottesman for kindly supplying us with bacterial strains and Dr. A. Oppenheim and Dr. J.-L. Pernodet for plasmids. We also thank F. R. Warshaw-Dadon (Jerusalem) for her critical reading of this manuscript. This research was supported by a grant of the United States-Israel Binational Science Foundation awarded to H.E.-K.

ABBREVIATIONS

- ppGpp

guanosine 3′,5′-bispyrophosphate

- IPTG

isopropyl β-d-thiogalactoside

- LB

Luria–Bertani

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the Proceedings Office.

References

- 1.Court D, Oppenheim A B. In: The Bacteriophage lambda II. Hendrix R W, Roberts J W, Stahl F W, Weisberg R A, editors. Plainview, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press; 1983. pp. 251–276. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Snyder L, Kaufman G. In: Molecular Biology of Bacteriophage T4. Drake J W, Kreuzer K N, Mosig G, Hall D H, Eiserling F A, Black L W, Spicer E K, Kutter E, Carlson K, Miller E S, editors. Washington, DC: Am. Soc. Microbiol.; 1994. pp. 391–396. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parma D H, Snyder M, Sobolevski S, Nawroz M, Brody E, Gold L. Genes Dev. 1992;6:497–510. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.3.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schoulaker-Schwarz R, Dekel-Gorodetsky L, Engelberg-Kulka H. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:4996–5000. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.11.4996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Landsman J, Kroger M, Hobom G. Gene. 1982;20:11–24. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(82)90083-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matz K, Schmandt M, Gussin G N. Genetics. 1982;102:319–327. doi: 10.1093/genetics/102.3.319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hayes S, Szybalski W. Mol Gen Genet. 1973;126:257–290. doi: 10.1007/BF00269438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Belfort M. J Virol. 1978;28:270–278. doi: 10.1128/jvi.28.1.270-278.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hayes S, Bull H J, Tulloch J. Gene. 1997;189:35–42. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00824-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gottesman S, Clark W P, deCrecy-Layard V, Maurizi M R. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:22618–22626. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wojtkowiak D, Georgopoulos C, Zylicz M. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:22609–22617. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Katayama Y, Gottesman S, Pumphrey J, Rudikoff S, Clark W P, Maurizi M R. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:15226–15236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gottesman S, Clark W P, Maurizi M R. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:7886–7893. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maurizi M R, Clark W P, Kim S H, Gottesman S. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:12546–12552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bejarano I, Klemes Y, Schoulaker-Schwarz R, Engelberg-Kulka H. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:7720–7723. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.23.7720-7723.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jensen R B, Gerdes K. Mol Microbiol. 1995;17:205–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_17020205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yarmolinsky M B. Science. 1995;267:836–837. doi: 10.1126/science.7846528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lehnherr H, Maguin E, Jafri S, Yarmolinsky M B. J Mol Biol. 1993;233:414–428. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lehnherr H, Yarmolinsky M B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:3274–3277. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.8.3274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aizenman E, Engelberg-Kulka H, Glaser G. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:6059–6063. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.12.6059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Masuda Y, Miyakwa K, Nishimura Y, Ohtsubo E. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:6850–6856. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.21.6850-6856.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Metzger S, Ben-Dror I, Aizenman E, Schreiber G, Toone M, Friesen J D, Cashel M, Glaser G. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:15699–15704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller J H. Experiments in Molecular Genetics. Plainview, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Casadaban M J, Cohen S N. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:4530–4533. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Horii Z I, Clark A J. J Mol Biol. 1973;80:327–344. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(73)90176-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Churchward G, Belin D, Nagamine Y. Gene. 1984;31:165–171. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(84)90207-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clerget M. New Biol. 1991;3:780–788. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schreiber G, Metzger S, Aizenman E, Roza S, Cashel M, Glaser G. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:3760–3767. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Svitil A L, Cashel M, Zyskind J W. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:2307–2311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blondelet-Rouault M-H, Weiser J, Lebrihi A, Branny P, Pernodet J-L. Gene. 1997;190:315–317. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00014-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Daniels D L, Schroeder J L, Szybalski W, Sanger F, Coulson A, Hony G F, Hill D F, Petersen G B, Blattner F R. In: The Bacteriophage Lambda II. Hendrix R W, Roberts J W, Stahl F W, Weisberg R A, editors. Plainview, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press; 1983. pp. 519–676. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. 2nd Ed. Plainview, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cashel M, Gentry D R, Hernandez V Z, Vinella D. In: Escherichia coli and Salmonella: Cellular and Molecular Biology. Neidhardt F C, Curtiss R I I I, Ingraham J L, Ling E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W R, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Washington, DC: Am. Soc. Microbiol.; 1996. pp. 1458–1496. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krohe H E, Simonm L D. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:6026–6034. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.10.6026-6034.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tomoyasu T, Gamer J, Bakau B, Kanemori M, Mori M, Rutman A, Oppenheim A B, Yura T, Yamanaka K, Niki H, et al. EMBO J. 1995;14:2551–2560. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07253.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kihara A, Akiyama Y, Ito K. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:5544–5549. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.11.5544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shotland Y, Koby S, Teff D, Mansur N, Oren D A, Tatematsu K, Tomoyasu T, Kessel M, Bakau B, Ogura T, et al. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:1303–1310. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.4231796.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gottesman S, Maurizi M R, Wickner S. Cell. 1997;91:435–438. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80428-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Herman C, Thevenet D, D’Ari R, Bouloc P. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:358–363. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.2.358-363.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hoyt M A, Knight D M, Das A, Miller H I, Echols H. Cell. 1982;31:565–573. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90312-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bahl H, Echols H, Straus D B, Court D, Crowl R, Georgopoulos C P. Genes Dev. 1987;1:57–64. doi: 10.1101/gad.1.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Snyder L. Mol Microbiol. 1995;15:415–420. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02255.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shub D A. Curr Biol. 1994;4:555–556. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00124-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]