Abstract

Background

Niacin is widely available over the counter (OTC). We sought to determine the safety of 500 mg immediate release niacin, when healthy individuals use them as directed.

Methods

51 female and 17 male healthy volunteers (mean age 27 years SD 4.4) participated in a randomized placebo-controlled blinded trial of a single dose of an OTC, immediate-release niacin 500 mg (n = 33), or a single dose of placebo (n = 35) on an empty stomach. The outcomes measured were self-reported incidence of flushing and other adverse effects.

Results

33 volunteers on niacin (100%) and 1 volunteer on placebo (3%) flushed (relative risk 35, 95% confidence interval (CI) 6.8–194.7). Mean time to flushing on niacin was 18.2 min (95% CI: 12.7–23.6); mean duration of flushing was 75.4 min (95% CI: 62.5–88.2). Other adverse effects occurred commonly in the niacin group: chills (51.5% vs. 0%, P < .0001), generalized pruritus (75% vs. 0%, P = <.001), gastrointestinal upset (30% vs. 3%, P = .005), and cutaneous tingling (30% vs. 0%, P = <.001). Six participants did not tolerate the adverse effects of niacin and 3 required medical attention.

Conclusion

Clinicians counseling patients about niacin should alert patients not only about flushing but also about gastrointestinal symptoms, the most severe in this study. They should not trust that patients would receive information about these side effects or their prevention (with aspirin) from the OTC packet insert.

Keywords: Over-the-counter, Randomized controlled trial, Niacin

Background

The popularity and availability of over-the-counter health products (OTCs) is of concern. Some OTCs, particularly natural health products, are regarded as agents with minimal toxic potential and are therefore not required to pass the strict authentication processes required of prescription drugs [1,2]. Furthermore, surveys suggest that traditional passive mechanisms of reporting of adverse events are unreliable [3,4]. Indeed, it is possible that the public's perceptions of safety are related to suboptimal reporting of adverse reactions [5]. The apparent safety of these agents may be confirmed by product labels and package inserts that underplay the potential for harm.

Niacin (an OTC vitamin B3 or nicotinic acid) has favorable effects on the lipid profile, but more importantly, there is evidence of its favorable impact on patient important outcomes. In the Coronary Drug Project, patients randomized to receive niacin had a decrease in nonfatal recurrent myocardial infarction and a reduction in all-cause mortality nine years after termination of the trial [6]. In other randomized trials, the combination of niacin and lovastatin reduced cardiovascular risk in patients with coronary artery disease[7], and the combination of niacin and simvastatin produced marked clinical and angiographic benefits in these patients[8,9].

Some studies have suggested that the release of prostaglandin D2 (PGD2) from dermal macrophages probably mediates the cutaneous flushing following niacin use [10,11]. In spite of the known and common association between niacin and flushing and other adverse reactions, the package labels and inserts may not sufficiently warn the buyer of over-the-counter immediate release niacin (Table 1). While minimized by the use of aspirin and ibuprofen,[12,13] this cutaneous flush, along with other reversible adverse effects (such as gastrointestinal upset, pruritus, rash and headache) often leads to discontinuation of therapy [14].

Table 1.

Warnings & Precautionary Statements of Niacin Supplements from Different Vitamin Companies

| Product | Warnings & Precautionary Statements |

| Product 1. 500 mg caplets | Niacin may cause flushing, itching or burning sensations of the skin within twenty minutes after administration. Individuals with a history of ulcer, gallbladder or liver disease should consult their physician before use. |

| Product 2. 500 mg tablets | Temporary flushing, itching or warming of the skin may occur. Do not use in cases of gout, diabetes, liver dysfunction or pregnancy. |

| Product 3. 500 mg tablets | It is important to consult your physician before taking any nicotinic acid product. Do not use in case of pregnancy, gout, diabetes, ulcers or liver dysfunction without medical supervision. Temporary flushing, itching or warming of the skin may occur. |

| Product 4. 500 mg tablets | May cause mild flushing, itching or burning sensation of the skin within twenty minutes after administration. Those individuals with a history of ulcer, gallbladder or liver disease should consult their physician before taking these tablets. |

| Product 5. 500 mg tablets | May cause some flushing, itching or burning skin sensations. In case of a history of ulcers, gallbladder or liver disease, consult a physician. |

Niacin is widely available over-the-counter and can be easily purchased in settings where trained healthcare professionals are not available to provide advice or warn of adverse effects. We undertook a randomized trial of immediate-release niacin in healthy volunteers in order to document the adverse effects of niacin when taken as directed by the package label by a healthy individual. In this study, we evaluated the incidence, duration, tolerability and severity of flushing and other adverse effects following the ingestion of 500 mg of immediate release niacin.

Methods

The institutional review board of the Canadian College of Naturopathic Medicine approved the protocol, and all participants gave written informed consent prior to study inclusion. We adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki during all phases of study conduct.

Participants

We recruited healthy volunteers from a student population through lecture announcements. To be eligible for this study, participants should be 20–60 years of age and be able to comprehend and complete the intake and informed consent forms. In addition, they should be able to complete a 12-hour pre-trial fast, to abstain from food, caffeine, and alcohol during the study, and to avoid all medications known to influence gastric acid secretion. Participants with history of liver disease, gout, gastrointestinal disease, diabetes mellitus, and intolerance to niacin were excluded. Participants did not receive remuneration for participation.

Study Design

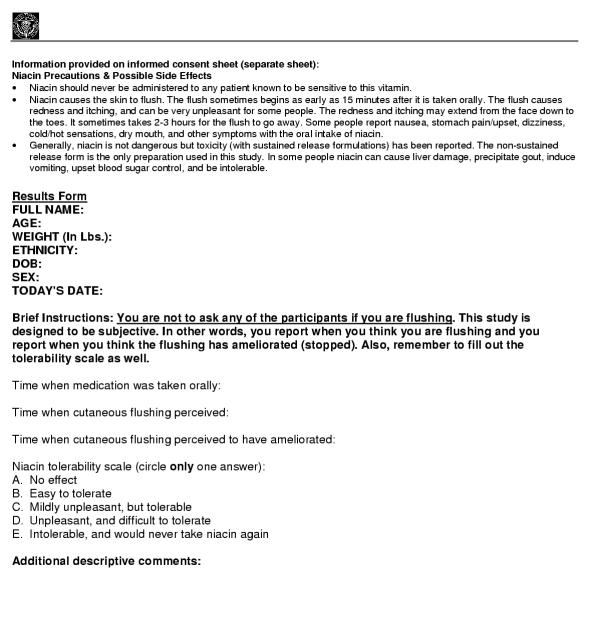

Enrolled participants attended the research center the morning of the trial. That morning, we blindly allocated patient pairs to receive niacin or placebo by coin toss. All study personnel were blind to treatment allocation and had no way of influencing whether a participant would receive niacin or placebo. After clocks were synchronized and placed around the study location, we asked all participants to ingest the study drug at the same time. Then we asked them to record time of ingestion of the study medication, perceived onset and cessation of flushing, to record other adverse effects noted, and to judge the overall tolerability of the study drug on a 5-point Likert-type scale (See Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Results form.

Study drugs

Jamieson laboratories Inc. provided 500-mg immediate release niacin in a white, oblong, bisect caplet. We independently confirmed caplet content using high performance liquid chromatography. Most over-the-counter niacin products suggest 500 mg of niacin as a starting dose. The placebo was matched to the study drug for taste, color, and size, and contained microcrystalline cellulose, silicon dioxide, dicalcium phosphate, magnesium stearate, and stearic acid.

Outcome Measures

Our primary outcome was incidence of flushing. Secondary outcomes included tolerability, time to onset of flushing, duration of flushing, additional adverse effects and the total number of serious adverse effects requiring medication for relief. Participants reported duration of flushing when they felt the flushing had discontinued.

Statistical Analyses

Data analysts were not blind to allocation. We estimated the sample size required to have 90% power to detect a difference in the incidence of flushing of 90% or greater between niacin and placebo (alpha = 0.05). We used the Mantel-Haenszel procedure to compare the proportion of participants with flushing in both groups, using a two-tailed P value < .05 as the threshold for significance. Additionally, we performed linear regression to explore whether age, gender, weight or ethnicity predicted tolerability.

Results

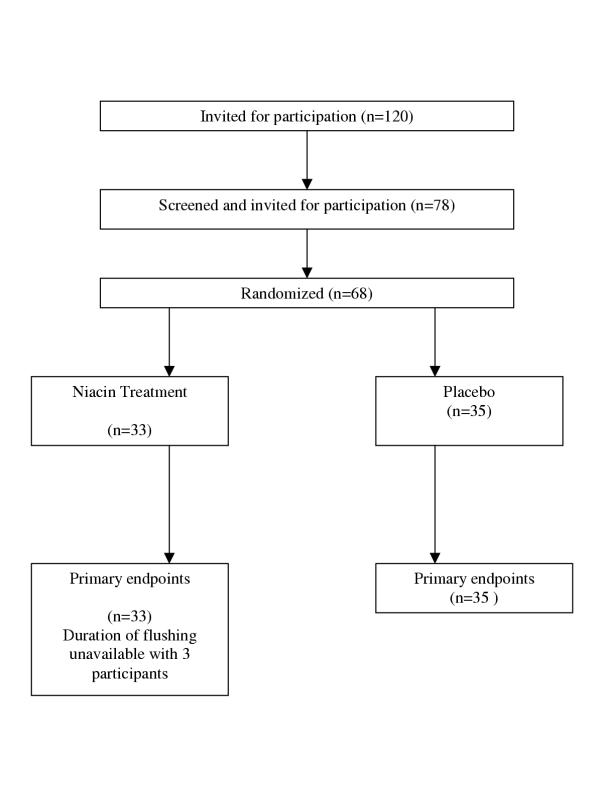

Participant flow is illustrated in Figure 2 and participant characteristics are noted in Table 2. A total of 33 participants in the niacin group (100%) and one (3%) in the placebo group reported cutaneous flushing (P < .0001). The mean time to onset of cutaneous flushing was 18.2 minutes (95% confidence interval 12.7–23.6) and the mean duration of flushing was 75.4 minutes (95% confidence interval 62.5–88.2) in the niacin arm. The single patient in the placebo arm flushed 35 minutes after taking the placebo pill but did not report the duration. Table 3 summarizes participants' tolerability of niacin and placebo pills. Table 4 outlines the adverse drug reactions by group.

Figure 2.

Flow of participants throughout the trial.

Table 2.

Study Participants

| Niacin (n = 33) | Placebo (n = 35) | |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 27.2 (5.23) | 26.4 (3.32) |

| Sex: Male | 7 | 10 |

| Female | 26 | 25 |

| Weight, kg, mean (SD) | 64.05 (11.15) | 64.7 (11.29) |

| Ethnicity: | ||

| Caucasian | 24 | 24 |

| Black | 1 | 1 |

| Middle Eastern | 0 | 2 |

| Hispanic | 1 | 1 |

| East Asian | 5 | 5 |

| South Asian | 2 | 2 |

SD, standard deviation

Table 3.

Reported tolerability of niacin and placebo

| Tolerability, No. (%) | Niacin (n = 33) | Placebo (n-35) |

| No effect | 0 (0) | 34 (97.1) |

| Easy to tolerate | 2 (6.1) | 1 (2.9) |

| Mildly unpleasant, but tolerable | 14 (42.4) | 0 (0) |

| Unpleasant, and difficult to tolerate | 11 (33.3) | 0 (0) |

| Intolerable, and would never take niacin again | 6 (18.2) | 0 (0) |

Table 4.

Adverse events reported

| Adverse Event | Niacin (n = 33) | Placebo (n = 35) | P-value |

| Composite of pruritus (head. neck, extremities or torso): | 25 (75%) | 0 | <0.001 |

| Composite of tingling (head, torso): | 10 (30%) | 0 | <0.001 |

| Unpleasant warmth or flushing: | 33 (100%) | 1 | <0.001 |

| Nausea | 10 (30%) | 1 (3%) | .005 |

| Vomiting | 4 (12%) | 0 | .005 |

| Stomach cramps | 2 (6%) | 0 | NS |

| Vertigo | 4 (12%) | 0 | .05 |

| Difficult breathing | 2 (6%) | 0 | NS |

| Chills* | 17 (52%) | 0 | < .0001 |

| Pass stool | 3 (9%) | 0 | NS |

| Heart palpitations | 5 (15%) | 0 | .0228 |

| Other | 4 (12%) | 1 (3%) | NS |

* Chills are defined as shivering accompanied by the sensation of coldness and pallor of the skin.

Three participants (2 female, 1 male) in the niacin group withdrew from the study because of the severity of adverse drug reactions. Emergency unblinding of these participants was necessary. Two of these individuals vomited and the other had severe stomach cramping and nausea. These participants were given either antihistamine drugs, ibuprofen or bismuth salicylate. Additionally, one participant required a small amount of food to relieve gastrointestinal upset. All participants requiring medical attention received medical care until they reported returning to normal health. We did not identify predictors of tolerability related to age, ethnicity, sex or weight.

Discussion

This randomized placebo-controlled blinded trial of a single dose of immediate release niacin demonstrates the association between OTCs and important adverse effects (flushing, chills, and gastrointestinal side effects), severe enough in 9% of these young healthy volunteers to necessitate medical attention. The severity of the adverse effects and the relative frequency of them following a single dose of the product could not have been predicted from reviewing the product information available at the point of retail.

Our study used random allocation of participants and blinding to limit bias in the ascertainment of treatment effects, particularly since participants self-reported the adverse effects of treatment. We studied young healthy volunteers instead of older patients with comorbidities, a group more representative of those likely to use niacin to treat dyslipidemia. However, the development of intolerable side effects in 1 out of 5 young healthy volunteers likely underestimates the impact of adverse effects among older patients with comorbidities. Our study is of brief duration and only ascertained the effect of a single dose of niacin in a fasting state. Longer-term niacin use has been associated with liver disease, an outcome that we did not set out to investigate [15]. Patients may be able to tolerate niacin's adverse effects with continued use, dose titration, switch to sustained-release preparations, pre-treatment with low-dose aspirin, or ingesting niacin with a meal. Given the findings of our study, clinicians considering niacin should begin with low-dose or time-released niacin to determine tolerability. However, while clinicians are generally aware of these strategies to limit the side effects of niacin, individuals buying immediate release niacin over-the-counter may not know how to prevent them.

We know of two other randomized trials specifically studying the adverse effects of 500 mg immediate-release niacin and testing the use of aspirin and ibuprofen to prevent them [12,13]. None of those studies used controls not receiving niacin and, therefore, provide limited inferences as to the true relative risk of adverse effects with immediate release niacin. Furthermore, they did not set out to investigate the extent to which aspirin pre-treatment reduced the impact of gastrointestinal side effects, the most severe and distressing adverse effect in our study.

Clinicians should consider sharing information with their patients about the relative safety of OTCs. However, when clinicians turn to the literature to learn about the safety of OTCs they will find very little reliable evidence [16]. The vast majority of information regarding adverse drug reactions is derived from case reports (30%) [17]. Controlled trials investigating therapy often report adverse drug reactions yet are often underpowered to provide robust estimates of the risk for rare but severe adverse drug reactions [17]. Additionally, not all clinical drug trials provide data on the frequency of adverse effects nor are likely to mention this in an abstract [18]. Thus, searching databases for information on adverse drug reactions has many limitations [19,20]. The post-marketing voluntary reporting process is haphazard and unreliable, particularly when physicians do not personally observe these reactions [21]. In certain situations, consumers, clinicians, and policymakers could benefit from rigorous trials designed and powered to detect and characterize common and acute adverse effects of commonly used medications (or OTCs). However, in most situations (i.e., when products exhibit rare but severe adverse effects with long-term use), reliable and precise safety information will remain simply unattainable.

Our study highlights the trade-off involved in policy decisions to make health products available in retail stores without mediation of a health professional, such as a pharmacist. This study suggests potentially important economic considerations, not only from widespread unregulated consumption of these products, but also from resource utilization to treat their adverse effects. For instance, does the public know to consider safety issues when buying yet another vitamin? (Niacin is identified as a vitamin, vitamin B3) It may be possible to implement regulation, which ensure product labels contain detailed information regarding potential adverse effects. Further debate about the public health implications of expanding the pool of OTCs and keeping natural health products unregulated is long overdue.

While the adverse effects observed in this trial may be well known from clinical experiences, it is possible that niacin would have difficulties passing licensure from a regulatory body. This study additionally addresses the public perception that natural health products are natural, and thus safe. When considering the risk-benefit profile of common statins to niacin, the stains have evidence of safety and efficacy above niacin [22,23].

Conclusions

In summary, this study (1) demonstrates the need for randomized trials to inform policy and patient choice about the safety of OTCs; (2) underscores the adverse public health impact of OTCs; and (3) likely underestimates the impact of adverse effects of OTCs in patients with comorbidities.

Competing interests

None declared.

Author contributions

EM designed the study and wrote the manuscript

JP conceptualized the study, enrolled participants, assisted in design and co-wrote the manuscript.

GR assisted in participants enrolment, dealt with emergency procedures and co-wrote the manuscript.

JG assisted in trial planning, randomization, analysis and co-wrote the manuscript.

BR assisted in trial planning, ethics review and analysis.

VM assisted in analysis and co-wrote the manuscript.

DJ assisted in analysis and co-wrote the manuscript.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

This study received no external funding. Jamieson Laboratories donated the study drug and placebo. They had no role in study design, data analysis, and they have not received the study results.

Contributor Information

Edward Mills, Email: emills@ccnm.edu.

Jonathan Prousky, Email: jprousky@ccnm.edu.

Gannady Raskin, Email: graskin@ccnm.edu.

Joel Gagnier, Email: j.gagnier@utoronto.ca.

Beth Rachlis, Email: brachlis@ccnm.edu.

Victor M Montori, Email: montori.victor@mayo.edu.

David Juurlink, Email: david.juurlink@ices.on.ca.

References

- FDA Center for Food Safety & Applied Nutrition Dietary Supplements. http://vm.cfsan.fda.gov/~dms/supplmnt.html Dec.10, 2002.

- HealthCanada. Dept of Justice. Food and Drugs Act. ( RS 1985, c F-27 )

- Barnes J, Mills SY, Abbot NC, Willoughby M, Ernst E. Different standards for reporting ADRs to herbal remedies and conventional OTC medicines: face-to-face interviews with 515 users of herbal remedies. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;45:496–500. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1998.00715.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eland IA, Belton KJ, van Grootheest AC, Meiners AP, Rawlins MD, Stricker BH. Attitudinal survey of voluntary reporting of adverse drug reactions. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1999;48:623–627. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1999.00060.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Improving ADR reporting. Lancet. 2002;360:1435. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11485-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canner PL, Berge KG, Wenger NK, Stamler J, Friedman L, Prineas RJ, Friedewald W. Fifteen year mortality in Coronary Drug Project patients: long-term benefit with niacin. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1986;8:1245–1255. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(86)80293-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashyap ML, McGovern ME, Berra K, Guyton JR, Kwiterovich PO, Harper WL, Toth PD, Favrot LK, Kerzner B, Nash SD, Bays HE, Simmons PD. Long-term safety and efficacy of a once-daily niacin/lovastatin formulation for patients with dyslipidemia. Am J Cardiol. 2002;89:672–678. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(01)02338-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown BG, Zhao XQ, Chait A, Fisher LD, Cheung MC, Morse JS, Dowdy AA, Marino EK, Bolson EL, Alaupovic P, Frohlich J, Albers JJ. Simvastatin and niacin, antioxidant vitamins, or the combination for the prevention of coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1583–1592. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SoRelle R. Niacin-simvastatin combination benefits patients with coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2001;104:E9050–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrow JD, Parsons W. G., 3rd, Roberts L. J., 2nd. Release of markedly increased quantities of prostaglandin D2 in vivo in humans following the administration of nicotinic acid. Prostaglandins. 1989;38:263–274. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(89)90088-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrow JD, Awad JA, Oates JA, Roberts L. J., 2nd. Identification of skin as a major site of prostaglandin D2 release following oral administration of niacin in humans. J Invest Dermatol. 1992;98:812–815. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12499963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jungnickel PW, Maloley PA, Vander Tuin EL, Peddicord TE, Campbell JR. Effect of two aspirin pretreatment regimens on niacin-induced cutaneous reactions. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12:591–596. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.07118.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn RT, Ford MA, Rindone JP, Kwiecinski FA. Low-Dose Aspirin and Ibuprofen Reduce the Cutaneous Reactions Following Niacin Administration. Am J Ther. 1995;2:478–480. doi: 10.1097/00045391-199506000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenney JM, Proctor JD, Harris S, Chinchili VM. A comparison of the efficacy and toxic effects of sustained- vs immediate-release niacin in hypercholesterolemic patients. Jama. 1994;271:672–677. doi: 10.1001/jama.271.9.672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clementz GL, Holmes AW. Nicotinic acid-induced fulminant hepatic failure. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1987;9:582–584. doi: 10.1097/00004836-198710000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst E, Pittler MH. Risks associated with herbal medicinal products. Wien Med Wochenschr. 2002;152:183–189. doi: 10.1046/j.1563-258X.2002.01112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aronson JK, Derry S, Loke YK. Adverse drug reactions: keeping up to date. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2002;16:49–56. doi: 10.1046/j.1472-8206.2002.00066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bracchi R. Drug companies should report side effects in terms of frequency. Bmj. 1996;312:442. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7028.442b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards JE, McQuay HJ, Moore RA, Collins SL. Reporting of adverse effects in clinical trials should be improved: lessons from acute postoperative pain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1999;18:427–437. doi: 10.1016/S0885-3924(99)00093-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derry S, Kong Loke Y, Aronson JK. Incomplete evidence: the inadequacy of databases in tracing published adverse drug reactions in clinical trials. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2001;1:7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-1-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueiras A, Tato F, Fontainas J, Takkouche B, Gestal-Otero JJ. Physicians' attitudes towards voluntary reporting of adverse drug events. J Eval Clin Pract. 2001;7:347–354. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2753.2001.00295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yim BT, Chong PH. Niacin-ER and lovastatin treatment of hypercholesterolemia and mixed dyslipidemia. Ann Pharmacother. 2003;37:106–115. doi: 10.1345/aph.1C161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capuzzi DM, Morgan JM, Weiss RJ, Chitra RR, Hutchinson HG, Cressman MD. Beneficial effects of rosuvastatin alone and in combination with extended-release niacin in patients with a combined hyperlipidemia and low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:1304–1310. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(03)00318-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]