Abstract

The acute phase cytokines IL-1β, IL-6 and TNFα are produced early during inflammatory processes, including ischemia-reperfusion. The appearance and role of these cytokines in the early inflammation following reperfusion of grafts remain poorly defined. This study investigated the role of TNFα in the induction of early leukocyte infiltration into vascularized heart allografts. TNFα and IL-6 mRNA levels reached an initial peak 3 hrs post-transplant and a second peak at 9-12 hrs with equivalent levels in iso- and allo-grafts. A single dose of anti-TNFα mAb given at reperfusion decreased neutrophil and macrophage chemoattractant levels and early neutrophil, macrophage and memory CD8 T cell infiltration into allografts. Anti-TNFα mAb also extended graft survival from 8.6 ± 0.6 days to 14.1 ± 0.8 days. When assessed on day 7 post-transplant, the number of donor-reactive CD8 T cells producing IFN-γ in the spleen was reduced almost 70% in recipients treated with anti-TNFα mAb. Whereas anti-CD154 mAb prolonged survival to day 21, administration of anti-TNFα and anti-CD154 mAb delayed rejection to day 32 and resulted in long-term (> 80 days) survival of 40% of the heart allografts. These data implicate TNFα as an important mediator of early inflammatory events in allografts that undermine graft survival.

Introduction

The imposition of a period of ischemia is an inherent component of solid organ transplantation. Clinical studies as well as those in experimental models have documented the negative impact of ischemic time on the function and long-term survival of allografts. Notably, prolonged ischemic times in kidney transplantation are associated with increased incidence of delayed graft function (1-3). Furthermore, longer cold ischemic times for renal and heart grafts are associated with increased incidence of acute rejection episodes and the development of graft fibrosis and arteriopathy (4).

The reperfusion of ischemic tissues induces an intense inflammatory response in the tissue. This inflammation is initiated by the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that in turn activates the vascular endothelium of the tissue to express adhesion molecules and produce a variety of proinflammatory cytokines (5, 6). These proinflammatory cytokines include the acute phase proteins IL-1, IL-6, TNFα as well as many different neutrophil and macrophage chemoattractants. The activities of acute phase cytokines during inflammatory processes are many. These include activation of the vascular endothelium to mobilize selectins to the luminal membrane as well as the upregulated expression of integrin ligands (7-10). TNFα is also an important factor initiating the activation of interstitial dendritic cells and their emigration from tissue sites of inflammation to the peripheral lymphoid organs draining the inflammatory sites where they activate donor antigen-reactive T cells to become effector T cells (11, 12).

Studies from this laboratory have documented the early expression of neutrophil and macrophage chemoattractant chemokines in cardiac allografts in mouse models and the role of these chemoattractants in directing the infiltration of neutrophils and macrophages into the cardiac allografts within hours after reperfusion (13-15). Similar induction of these chemoattractants is also observed within minutes of reperfusion of clinical renal transplants (16). In murine models, the absence or neutralization of these chemokines inhibit early neutrophil infiltration into cardiac allografts and substantially prolongs graft survival (13, 15). In conjunction with low dose T cell costimulatory blockade, inhibition of early neutrophil mediated graft damage leads to the long-term survival of the allografts (13).

Many laboratories have demonstrated the ability of TNFα-specific antibodies to attenuate tissue inflammation and injury in animal models (17-21). These studies have spearheaded the clinical use of anti-TNFα mAb and TNF-binding proteins for treatment of inflammatory bowel disease and psoriasis (22-25). Many studies have documented a beneficial effect of anti-TNFα antibodies in delaying rejection of organ allografts for 5-10 days in animal models (26-30). However, the mechanisms underlying the effects of TNFα neutralization on components of early inflammatory events in the grafts remain undefined. Considering the critical role of early inflammatory events on allograft outcome and the role of TNFα as a component of ischemia-reperfusion injury, we have tested the impact of anti-TNFα mAb treatment on early inflammatory events in MHC-mismatched heart allografts and how this impacts graft outcome. The results of the current study indicate that administration of a single dose of anti-TNFα mAb at the time of allograft reperfusion attenuates many components of the early post-transplant inflammation including production of neutrophil and macrophage chemoattractants and the infiltration of these leukocyte populations as well as donor-reactive memory CD8 T cells into the allograft within the first 48 hours post-transplant. Furthermore, anti-TNFα mAb treatment inhibits the priming of donor-reactive T cells and extends allograft survival. These results indicate important roles for TNFα in the innate and adaptive alloimmune response to heart allogratts and suggest that neutralization of TNFα during early post-transplant periods may be a beneficial component of strategies to promote better allograft outcomes.

Materials and Methods

Mice

A/J (H-2a) and C57BL/6 (H-2b) mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Adult males, 8 -12 weeks of age/20-25 g, were used throughout this study. All mice were housed and treated in accordance with Animal Care Guidelines established by National Institutes of Health and their use in these studies was approved by the Cleveland Clinic Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Heterotopic Cardiac Transplantation

Heterotopic cardiac transplantation was performed using the method of Corry and coworkers (31). Briefly, donor hearts were harvested and placed in chilled Ringer's solution (Baxter Healthcare Corporation, Deerfield, IL) while the recipient mice were prepared. The donor heart was anastomosed to the recipient abdominal aorta and inferior vena cava using microsurgical techniques. On completion of the anastomoses and organ reperfusion, the heart grafts resumed spontaneous contraction. Ischemic time averaged 20 min, and the overall success rate was > 95%. The strength and quality of cardiac graft impulses were monitored by palpation of the abdomen. Graft failure was defined as the absence of detectable beating and was confirmed visually for each graft by laparotomy.

Antibodies

Anti-TNFα mAb (XT-3.11) and anti-CD154 mAb (MR-1) were obtained from BIO EXPRESS (West Lebanon, NH). Rat anti-mouse Ly-6G mAb (RB6–8C5) was purified from spent culture supernatant using protein G-Sepharose.

Immunohistology

A mid-ventricular portion of the cardiac graft was embedded in OCT compound (Sakura Finetek U.S.A., Torrance, CA), immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen following harvest and 6-μm thick sections were prepared and mounted onto slides. After drying the sections were fixed in acetone for 10 min, immersed in PBS for 10 min and in 0.1% H2O2/PBS for 5 min at room temperature (RT) to eliminate endogenous peroxidase activity. Endogenous biotin activity was blocked with the Biotin Blocking System (DAKO, Carpinteria, CA). After treating with normal rat serum (1:100), slides were stained with 20 μg/ml GK1.5, 53–6.7, or F4/80, or with 10 μg/ml RB6–8C5 in PBS with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 1 hour at RT and then with biotinylated rabbit anti-rat IgG (DAKO Corporation, Carpinteria, CA) diluted 1:300 in PBS for 20 minutes at RT. The slides were developed with DAB (3,3′-diaminobendizine) substrate-chromagen solution (Vector Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame CA) and counter-stained by immersion in hematoxylin for 1 min. After washing in dH2O, slides were cover-slipped and viewed with a light microscope. Representative images were captured and analyzed with Image Pro Plus (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD).

ELISPOT Assay

Donor-reactive T cells producing IFN-γ were enumerated by ELISPOT assay as previously described (32, 33). Briefly, ELISPOT plates (Immunospot M200 plates; Cellular Technologies Ltd, Cleveland, OH) were coated with IFN-γ specific mAb and blocked with 1% BSA/PBS. CD4+ T cells and CD8+ cells were separated from allograft recipient and naïve mouse spleen cell suspensions by negative selection with a Mouse T Cell CD4 or CD8 Subset Column Kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) and 1 × 106 cells/well were cultured with 3 × 105 mitomycin C-treated spleen cells in HL-1 media. After 24 hours the cells were removed and 4 μg/ml biotin-rat-anti-mouse IFN-γ detection antibody, XMG1.2, was added and incubated overnight at 4° C. Alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-biotin antibody (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) was added for 1.5 hours at RT and the plates were developed with nitroblue tetrazolium chloride (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate substrate (Sigma Chemical Company, St. Louis, MO). The resulting spots were counted on an ImmunoSpot Series 2 Analyzer (Cellular Technologies Ltd., Cleveland, OH).

RNA extraction and quantitative analysis of chemokines

Approximately one-third pieces of harvested heart grafts were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. Total RNA in the heart was extracted using the RNeasy™ Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA) and reverse transcribed using the High-Capacity cDNA Archive Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Quantitative real time PCR was performed on a Prism 7700 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) using specific primers for mouse IL-1β, IL-6, TNFα, KC/CXCL1, MIP-2/CXCL2 and MCP-1/CCL2 and Mrpl 32 as a control (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The comparative CT method for relative quantitation of cytokine gene expression was used where for each sample the expression level of the Mrpl 32 housekeeping gene was subtracted from the expression level for each test cytokine gene. For each test cytokine, the expression level of a single RNA sample prepared from the allograft of a control treated wild-type recipient was used as the calibrator and was arbitrarily set at 1.0 and the expression levels of all other samples were then normalized to the calibrator. Duplicate runs of 3-4 RNA samples per group were tested and the data for each group are expressed as mean test cytokine expression level ± SEM.

Flow cytometry analysis

Absolute numbers of graft infiltrating neutrophils, macrophages, CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells were determined in heart grafts using antibody staining and flow cytometry (33, 34). Approximately, one-third pieces of harvested heart grafts were weighed and incubated in RPMI with 2% fetal calf serum (FCS) for 1 hour. The samples were pushed through a 70 μm cell strainer and the cells collected. Following RBC lysis with ACK Lysing Buffer (GIBCO, Carlsbad, CA) the leukocytes were counted using Trypan blue exclusion and light microscopy. Cell aliquots were preincubated with anti-CD16/CD32 Fc receptor for 5 min to block nonspecific antibody binding and then each sample was incubated for 30 min at 4°C with fluorochrome-labeled anti-mouse CD45 mAb and antibodies to detect specific leukocyte populations. Cells were analyzed using three-color immunofluorescence on a FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). For each sample, 200,000 total events were acquired without gating leukocytes for analysis. The leukocytes were gated using forward scatter and CD45. The data were analyzed using CellQuest software (BD Biosciences). Total numbers of each leukocyte population were calculated by: (the total number of leukocytes counted) × (% of the leukocyte population counted in the CD45+ cells)/100. The data are reported as number of each leukocyte population/mg graft tissue from sham and I/R animals.

Statistical analysis

Analysis of cardiac allograft survival were plotted using Kaplan-Meier cumulative survival curves and differences in survival between groups determined using the Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. Differences between groups for cellular infiltration, ELISPOT numbers and RNA expression levels were evaluated by unpaired Students' t-test using JMP (SAS institute Inc., Cary, NC), and a value of p < 0.05 was considered a significant difference.

Results

Early expression of acute phase cytokines in cardiac grafts

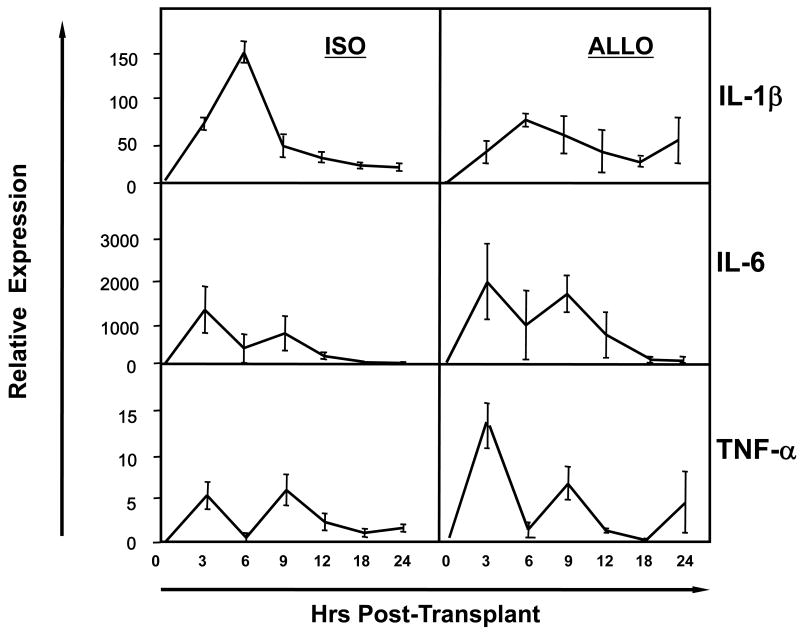

The expression of mRNA encoding acute phase cytokines within the first 24 hrs post-transplant was compared in cardiac iso- and allo-grafts. mRNA levels of IL-1β, IL-6 and TNFα were expressed equivalently in the iso- and allo-grafts through the first 24 hrs post-transplant (Figure 1). mRNA encoding IL-6 and TNFα reached peak levels 3 hrs after reperfusion of the transplant, dipped to background levels 3 hrs later and then rose to a second peak 3 hrs after that. mRNA encoding IL-1β was evident 3 hrs after reperfusion of the grafts but increased to a single peak 3 hours later and then fell to background levels by 9 hrs after reperfusion.

Figure 1. Pro-inflammatory cytokine expression early after heart transplantation.

Cardiac iso- and A/J allo-grafts were retrieved from groups of 4 C57BL/6 recipients at the indicated times post-transplant, whole cell mRNA was isolated from graft tissue homogenates, and the levels of mRNA encoding acute phase cytokines were determined by quantitative RT-PCR.

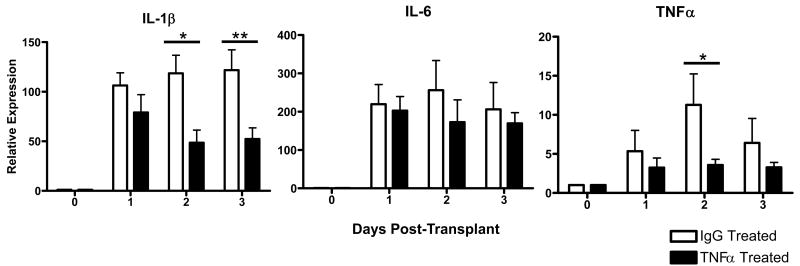

TNFα regulates the intensity of early inflammation in cardiac allografts

The role of TNFα in early inflammation in allografts was investigated. Recipients of cardiac allografts were treated with a single dose of anti-TNFα mAb or with rat IgG as a control at the time of transplant and levels of IL-1β, IL-6 and TNFα mRNA expression in the allografts were monitored at 24 hr intervals post-transplant. Treatment with the single dose of TNFα-specific mAb reduced the levels of TNFα mRNA to near background levels through the first 48 hrs post-transplant (Figure 2). Neutralization of TNFα at the time of allograft ischemia also reduced the expression of IL-1β but not L-6 in the graft. For IL-1β this decrease was most marked 2 and 3 days after reperfusion.

Figure 2. Neutralization of TNFα decreases intra-graft transcription of IL-1β and TNFα.

Groups of 6 cardiac allograft recipients were treated with a single dose of 500 μg anti-TNFα mAb (black bars) or rat IgG (white bars). The A/J allografts were retrieved from C57BL/6 recipients at the indicated times post transplant, whole cell mRNA was isolated from graft tissue homogenates, and the levels of mRNA encoding acute phase cytokines were determined by quantitative RT-PCR. *p< 0.05; **p< 0.01.

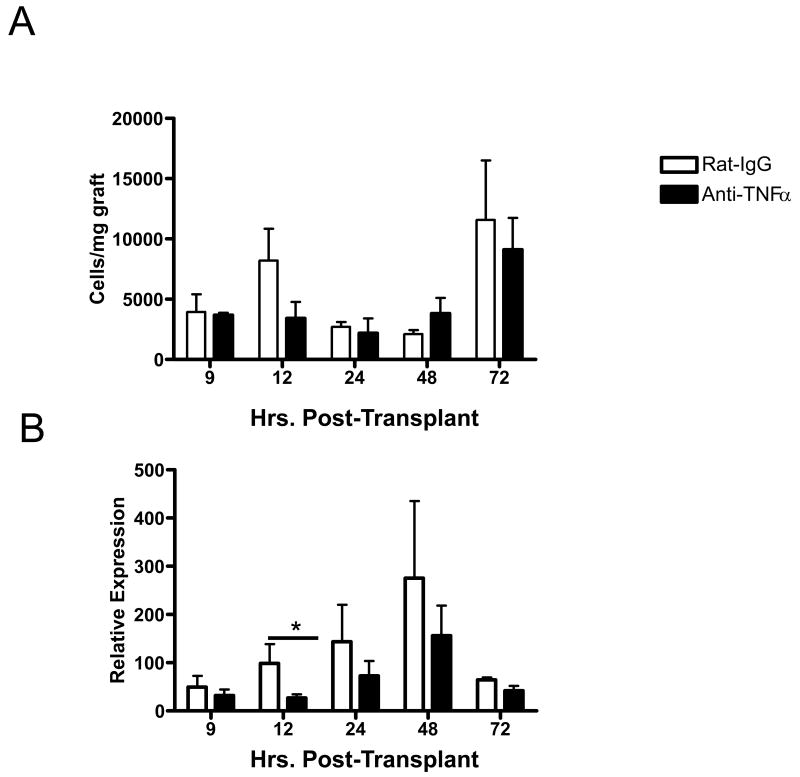

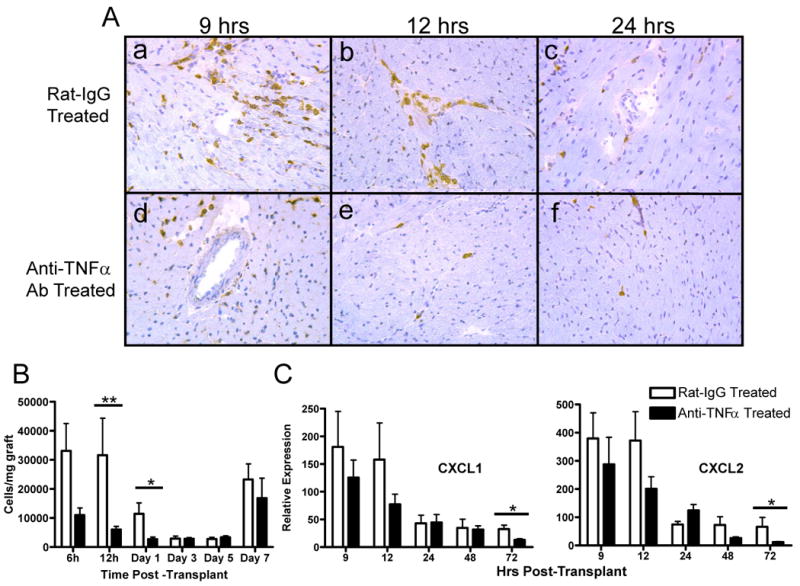

Treatment with the anti-TNFα antibody had an obvious and marked effect in decreasing initial neutrophil infiltration into the allografts at 9 hrs after reperfusion and this infiltration was reduced to near background levels by 12 hrs post-transplant when assessed by immunohistochemical analyses (Figure 3A). When the number of allograft infiltrating neutrophils was directly determined using digestion of the graft followed by flow cytometry analysis of infiltrating leukocytes, the number of infiltrating neutrophils at 12 hours post-transplant was virtually absent (Figure 3B). This decreased neutrophil infiltration was accompanied by modest decreases in levels of the neutrophil chemoattractants CXCL1 and CXCL2 in allografts retrieved from anti-TNFα mAb treated recipients (Figure 3C). Anti-TNFα antibody also had a modest effect in decreasing the numbers of macrophages infiltrating the cardiac allografts at 12 hrs post-transplant and this decrease also was reflected by decreased expression of the macrophage chemoattractant CCL2/MCP-1 in the allograft. Though only significantly decreases were observed at 12 hrs post-transplant, these decreases were maintained through 48 hours post-transplant.

Figure 3. Anti-TNFα mAb treatment diminishes neutrophil infiltration and neutrophil chemokine expression early post transplant.

Cardiac allograft recipients were treated with a single dose of 500 μg anti-TNFα mAb or rat IgG. A. The A/J allografts were retrieved from C57BL/6 recipients at the indicated times post transplant and prepared frozen sections were stained with anti-Gr1 mAb by immunohistochemistry to detect graft infiltrating neutrophils. B. Grafts were retrieved from groups of 4 recipients at the indicated times post-transplant and flow cytometry analyses of anti-CD45 and anti-Gr1 mAb stained cells from digested grafts were performed to determine numbers of neutrophils infiltrating the allografts. C. Grafts were retrieved from groups of 4 recipients at the indicated times post-transplant, whole cell mRNA was isolated from graft tissue homogenates, and the levels of mRNA encoding CXCL1 and CXCL2 were determined by quantitative RT-PCR. *p< 0.05; **p< 0.01.

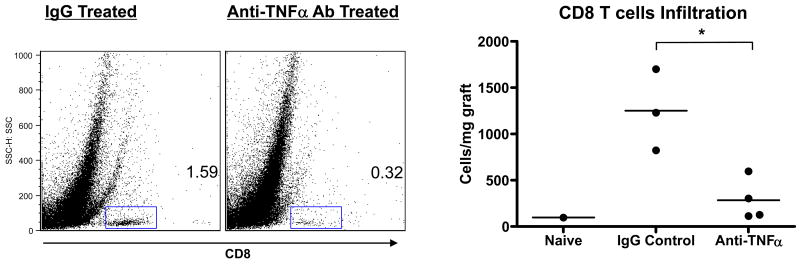

Recent studies from this laboratory have documented the infiltration and proinflammatory activities of memory CD8 T cells with donor-reactivity into cardiac allografts 24-72 hours after reperfusion of the allograft (33). These CD8 T cells mediate the increased neutrophil infiltration and activation in allografts vs. isografts observed at early time points post-transplant. To test the effect of TNFα neutralization on the allograft infiltration of these memory CD8 T cells, groups of cardiac allograft recipients were treated with 500 μg of control IgG or anti-TNFα antibody at the time of transplant and 48 hrs later the allografts were retrieved, digested and stained with anti-CD45 and anti-CD8 mAb to detect the graft infiltrating CD8 T cells (Figure 5). The TNFα neutralization significantly decreased the number of CD8 T cells infiltrating the allografts to almost background levels observed in native hearts.

Figure 5. Anti-TNFα mAb inhibits early infiltration of CD8 T cells into cardiac allografts.

Cardiac allograft recipients were treated with a single dose of 500 μg anti-TNFα mAb or rat IgG. A/J allografts were retrieved from groups of 3-4 C57BL/6 recipients 48 hrs post-transplant, as well as hearts from naïve C57BL/6 mice, and flow cytometry analyses of anti-CD45 and anti-CD8 mAb stained cells from digested grafts were performed to determine numbers of CD8 T cells infiltrating the allografts. *p < 0.05.

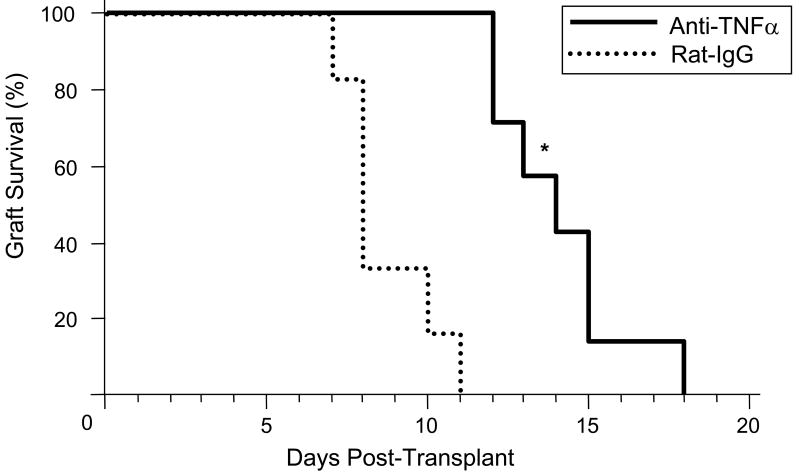

Effect of TNFα neutralization on allograft survival

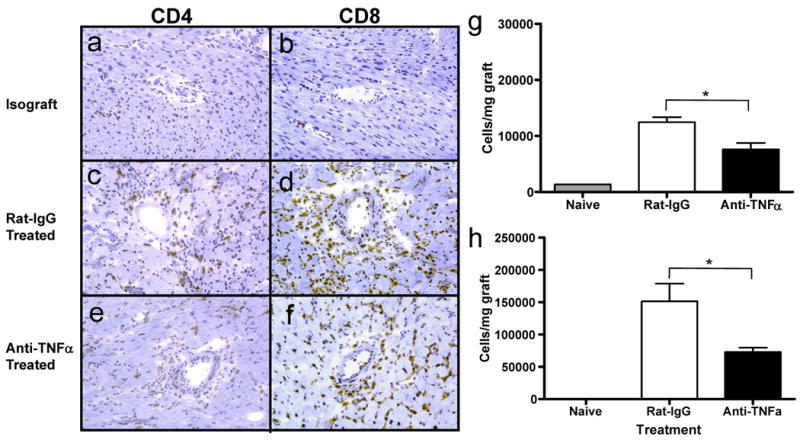

Treatment with a single peri-transplant dose of anti-TNFα mAb resulted in prolongation of cardiac allograft survival up to 7 days longer than the control IgG treated recipients (Figure 6). This prolongation was associated with a marked decrease in CD8 T cell infiltration into the grafts at day 7 post-transplant, the time allografts in the control treated recipients were beginning to reject the allografts (Figure 7). When the number of allograft infiltrating CD4 and CD8 T cells was directly determined by digestion of the graft followed by flow cytometry analysis of infiltrating leukocytes, the TNFα mAb treatment resulted in significant decreases in CD4 T cell infiltration into the allografts and a 60-70% decrease in allograft infiltrating CD8 T cells on day 7 post-transplant (Figure 7g and 7h). In addition to these decreases, lower numbers of graft infiltrating neutrophils and macrophages were also observed at this time point (data not shown).

Figure 6. Anti-TNFα mAb Treatment Prolongs Allograft Survival.

Groups of 5 C57BL/6 mice received cardiac allografts from A/J donors and the recipients were treated with a single dose of 500 μg anti-TNFα mAb or rat IgG at the time of graft reperfusion. Grafts were monitored daily by palpation and rejection was confirmed visually by laparatomy. *p < 0.05.

Figure 7. Anti TNFα mAb treatment impairs CD4 and CD8 infiltration into cardiac allografts.

C57BL/6 mice received cardiac allografts from A/J donors and were treated with a single dose of 500 μg anti-TNFα mAb or rat IgG at the time of graft reperfusion. Frozen sections of A/J cardiac allografts were prepared at day 7 post transplant, were stained with anti-CD4 (a,c,e) or with anti-CD8 (b,d,f) mAb, and were imaged at 100× magnification. Numbers of infiltrating CD4 (g) and CD8 (h) T cells were determined by staining cell suspensions prepared from each allograft in groups of 5 recipients with anti-CD45 mAb plus either anti-CD4 or anti-CD8 mAb and analyzing the cells by flow cytometry. *p < 0.05.

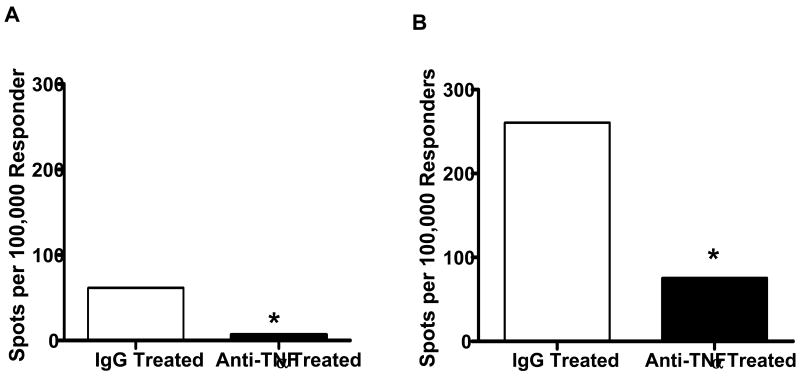

To investigate mechanisms that might account for the decreased CD8 T cell infiltration into the allografts, the levels of donor-reactive CD8 T cell priming to IFN-γ producing cells in the spleens of control IgG vs. anti-TNFα mAb treated recipients were enumerated by ELISPOT. At day 7 post-transplant, numbers of donor-reactive CD8 T cells producing IFN-γ were approximately 30% those observed in the spleens of the control treated recipients (Figure 8). TNFα neutralization at the time of transplantation also decreased the number of donor-reactive CD4 T cells producing IFN-γ at this time point.

Figure 8. Anti-TNFα mAb treatment decreases the development of donor-reactive CD4 and CD8 T cells producing IFN-γ in the allograft recipient spleen.

Groups of 3 C57BL/6 mice received cardiac allografts from A/J donors and were treated with a single dose of 500 μg anti-TNFα mAb or rat IgG at the time of graft reperfusion. On day 7 post-transplant CD4 and CD8 T cell populations were purified from prepared spleen cell suspensions and the number of donor-reactive (A) CD4 and (B) CD8 T cells producing IFN-γ in each allograft recipient group was determined by ELISPOT assay. Numbers of A/J-reactive T cells producing IFN-γ in the spleens of naïve mice was less than 20 spots per 105 stimulator cells. *p < 0.01.

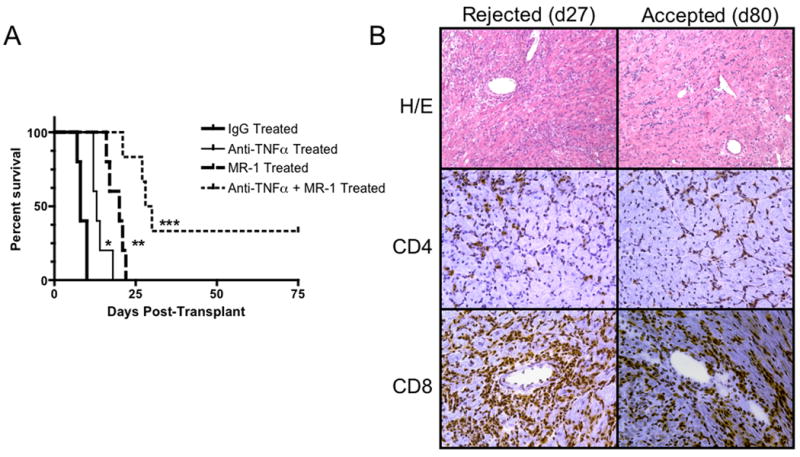

Finally, the potential synergy between anti-TNFα mAb treatment and short-term, low-dose costimulatory blockade with anti-CD154 mAb was tested. Allograft recipients were treated with the single dose of anti-TNFα mAb on the day of transplantation with or without anti-CD154 mAb on days 0, 1 and 2. Treatment with anti-CD154 mAb alone extended allograft survival slightly longer than treatment with anti-TNFα mAb alone (Figure 9A). However, the combined treatment promoted survival of 40% of the allografts greater than 80 days. Rejecting allografts from recipients treated with anti-TNFα mAb plus anti-CD154 mAb had the intense infiltration of CD8 T cells typically observed in the acute cell mediated rejection of these grafts (Figure 9B). In contrast, surviving allografts at day 80 post-transplant had slightly lower levels of CD8 T cell infiltration and almost no neutrophils (Figure 9B and data not shown).

Figure 9. Anti-TNFα mAb synergizes with low dose co-stimulation blockade to promote increased cardiac allograft survival.

Groups of 5-9 C57BL/6 mice received cardiac allografts from A/J donors and were treated with a single dose of 500 μg anti-TNFα mAb or rat IgG at the time of graft reperfusion, 250 μg anti-CD154 mAb on days 0, 1,and 2, or the anti-TNFα plus the anti-CD154 mAb. A. Grafts in each group were monitored daily by palpation and rejection was confirmed visually by laparotomy. B. Histological analysis of cardiac allografts retrieved form recipients treated with anti-TNFα plus anti-CD154 mAb that were rejected on day 28 post-transplant vs. long-term surviving allografts that were retrieved at day 80 post-transplant. Sections of each of the grafts were prepared, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin, with anti-CD4 mAb, or with anti-CD8 mAb. Images were viewed at 100× magnification. *p < 0.002 vs. control group; **p ≤ 0.02 vs. control and anti-TNFα mAb treated groups; *** p ≤ 0.02 vs. all other groups.

Discussion

Reperfusion of ischemic tissues induces a rapid and potent inflammatory response. This inflammatory response is initiated by the rapid production of ROS and their induction of acute phase proinflammatory cytokines (5, 6). These inflammatory events are followed by increased or induced expression of adhesion molecules on the vascular endothelial cells and the production of chemoattractants that direct the infiltration of leukocytes into the ischemic tissue. Identification of the acute phase cytokines as early components of ischemia-reperfusion injury has led several investigators to test the effects of neutralization on the injury induced. Administration of anti-TNFα antibodies has decreased infarct size and improved contractile function when given before or following imposition of cardiac ischemia in rat, rabbit, and dog models (19-21). Anti-TNFα antibodies also attenuated ischemic injury of kidneys and liver in rodent models that was accompanied by decreased neutrophil infiltration and activation in the ischemic organs (17, 18).

In solid organ transplantation ischemia-reperfusion injury has a direct effect on graft outcome. Grafts from cadaveric donors have increased incidence of delayed graft function and acute rejection episodes than those from living donors and prolonged ischemic times also have a direct effect on the levels of inflammation and long-term graft outcome (1-4). Studies from this laboratory have documented the rapid production of neutrophil and macrophage chemoattractants in heterotopically transplanted heart iso- and allo-grafts in murine models (14, 15, 35). This early inflammatory response is quickly followed by neutrophil infiltration into the grafts and neutrophil-dependent infiltration of donor-reactive CD8 memory T cells into the allografts (33, 36). The infiltrating neutrophil and CD8 memory T cell populations quickly increase the intensity of inflammation within the allograft. The impact of this early inflammation is indicated by the decreased infiltration of donor-antigen primed T cells and prolonged heart allograft survival when neutrophil infiltration into the allograft is inhibited (13, 15). Considering TNFα as an important component of ischemia-reperfusion injury, the current studies were directed to investigating the role of TNFα in these early post-transplant inflammatory events and to test if neutralization of TNFα would attenuate this inflammation and improve cardiac allograft outcome.

Many studies have tested the ability of peri-transplant administration of anti-TNFα polyclonal or monoclonal antibodies to prolong the survival of cardiac allografts in rodent models. These studies have documented a modest prolongation of allograft survival in anti-TNFα antibody treated recipients that was associated with delayed T cell infiltration into the allografts (26, 27, 37, 38). However, the mechanisms underlying this prolongation and the delayed T cell graft infiltration have remained unclear. Similar to these previous studies, administration of a single dose of anti-TNFα mAb at the time of transplant resulted in an approximate doubling of complete MHC-mismatched cardiac allograft survival and was accompanied by a delay in T cell infiltration into the allografts. Importantly, the results of the current study indicate that this neutralization has multiple effects on the innate and adaptive response to the heart allograft.

First, neutralization of TNFα has a marked effect in attenuating the early inflammatory response observed during reperfusion of the cardiac allografts. This includes down modulation of its own expression as well as IL-1 but not IL-6. In addition, the expression of neutrophil chemoattractant chemokines and neutrophil infiltration into the allografts through the first 24 hours post-transplant are markedly decreased. Early TNFα neutralization also deceased the expression of the macrophage chemoattractant CCL2 and macrophage infiltration into the allografts. These observations are in line with others demonstrating the key role of TNFα in the early inflammation caused by reperfusion of ischemic tissues and the ability to attenuate ischemic injury by neutralizing TNFα (17–21.) Although ROS generated during reperfusion of ischemic tissues induces the production of these chemokines and TNFα, these results indicate that TNFα directly induces the chemokines that recruit innate leukocyte populations into the graft. Attenuation of the early inflammation in the allograft was also accompanied by the absence of early CD8 T cell infiltration into the allograft. Previous studies from this laboratory have documented that these CD8 T cells have a memory phenotype, are reactive to donor class I MHC molecules, and produce IFN-γ in allo- but not iso-grafts within 24 hours of allograft reperfusion (33). Furthermore, these early graft infiltrating memory CD8 T cells are important contributors to the establishment of an inflammatory milieu in the allograft that facilitates the infiltration of effector T cells primed in the spleen into the allograft. Overall, the current studies document the important role of TNFα in initiating and amplifying the early inflammatory components in the cardiac allografts that undermine graft survival.

Second, peri-transplant administration of a single dose of anti-TNFα antibody has a profound effect in inhibiting alloreactive T cell priming. At the time allografts were rejected in control treated recipients, the magnitude of the donor-reactive CD8 T cell response was reduced by a third in recipients treated with the anti-TNFα mAb. A similar reduction was observed for the donor-reactive CD4 T cell compartment. This inhibition is likely to account for the reduced infiltration of T cells into allografts of recipients treated with TNFα neutralizing antibodies in previous studies. Interstitial dendritic cell emigration from tissue inflammatory sites is promoted by TNFα (39, 40) suggesting that this as a mechanism accounting for the decreased effector CD4 and CD8 T cell priming in the anti-TNFα mAb treated recipients. TNFα also upregulates class I and class II MHC antigens (30, 41) so that neutralization in allograft recipients may decrease the immunogenicity of the graft dendritic cells as well as the antigenicity of the graft itself. Recent studies in rodent models and in humans with rheumatoid arthritis or Crohn's disease have indicated that neutralization of TNFα with antibodies such as Infliximab is followed by the appearance of CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ T regulatory cell populations implicating TNFα in a counter-regulatory mechanism that attenuates Treg activities (42-45). It is possible that TNFα neutralization in cardiac allograft recipients increases Treg activity and that this underlies, at least in part, the decreased priming of donor-reactive CD4 and CD8 T cell populations in the antibody-treated recipients. However, the strong Treg mediated regulation invoked in C57BL/6 recipients of B6.H-2bm12 cardiac allografts that restricts the magnitude and duration of donor-reactive CD4 T cell priming is suggestive that the transplant induced TNFα is unlikely to mediate this counter regulation in the heart allograft recipients (46). Nevertheless, a much more extensive and focused investigation into this possibility is warranted to test the effect of transplant induced TNFα on the activities of Tregs in attenuating donor-specific T cell responses.

Although administration of anti-TNFα mAb had a modest effect on cardiac allograft survival, coupling the antibody with a short course of CD40L costimulatory blockade was quite effective in promoting allograft survival. The TNFα mAb not only extended allograft survival in anti-CD40L mAb treated recipients but also led to the long-term survival of 40% of the allografts. It is worth noting, however, that long-term surviving allografts with strong beating were clearly infiltrated with CD8 T cells. Whether these infiltrating CD8 T cells are expressing effector functions that would promote graft rejection, are quiescent, or are inhibiting rejection of the grafts is currently unknown. These results are reminiscent of recent studies indicating that conjunctive therapy directed at neutrophil mediated graft damage and costimulatory blockade is very effective in promoting long-term survival of MHC-mismatched heart allografts (13). In rat models, use of anti-TNFα antibody in combination with low dose cyclosporine A extended the survival of heart allografts and in combination with an anti-CD4 non-depleting antibody resulted in the long-term survival of 60% of MHC-mismatched small bowel transplants (26, 29, 47).

In summary, the results of this study have indicated the efficacy of a single dose of peri-transplant anti-TNFα mAb in attenuating the level of early inflammatory events in cardiac allografts. This inflammation has an adverse effect on allograft survival through directly promoting tissue damage and directing donor antigen-primed T cells into the graft. The administration of anti-TNFα antibody also had a marked effect on the priming of donor-reactive T cells and in combination with a low dose costimulatory blockade promoted the long-term survival of the allografts. Currently, reagents directed at neutralizing TNFα or the TNFα receptor are in clinical use for treatment of inflammatory bowel disease and psoriasis (22-25). The current study suggests that these reagents should have some efficacy in attenuating early ischemia-reperfusion induced inflammation in transplants and this potential use should be considered.

Figure 4. Anti-TNFα mAb treatment decreases macrophage infiltration and macrophage chemokine expression early post transplant.

Cardiac allograft recipients were treated with a single dose of 500 μg anti-TNFα mAb or rat IgG. A. A/J allografts were retrieved from groups of 3 C57BL/6 recipients at the indicated times post-transplant and flow cytometry analyses of anti-CD45 and anti-F4/80 mAb stained cells from digested grafts were performed to determine numbers of macrophages infiltrating the allografts. B. Grafts were retrieved from groups of 6 recipients at the indicated times post-transplant, whole cell mRNA was isolated from graft tissue homogenates, and the levels of mRNA encoding CCL2 were determined by quantitative RT-PCR. *p < 0.05.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the NIH (RO1-AI40459) and from the Roche Organ Transplant Research Foundation (60495086) to RLF. ADS was supported in part by NIH T32 GM07250 and the Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine MSTP.

References

- 1.Koo DD, Welsh KI, Roake JA, Morris PJ, Fuggle SV. Ischemia/reperfusion injury in human kidney transplantation: an immunohistochemical analysis of changes after reperfusion. Am J Pathol. 1998;153:557–576. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65598-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ojo AO, Wolfe RA, Held PJ, Port FK, Schmouder RL. Delayed graft function: risk factors and implications for renal allograft survival. Transplantation. 1997;63:968–974. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199704150-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Terasaki PI, Cecka JM, Gjertson DW, Takemoto S. High survival rates of kidney transplants from spousal and living unrelated donors. N Eng J Med. 1995;333:333–336. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199508103330601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Land W, Messmer K. The impact of ischemia/reperfusion injury on specific and nonspecific, early and late chronic events after organ transplantation. Transplant Rev. 1996;10:236–253. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Devarajan P. Update on mechanisms of ischemic acute kidney injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:1503–1520. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006010017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lefer AM, Tsao PS, Lefer DJ, Ma XL. Role of endothelial dysfunction in the pathogenesis of reperfusion injury after myocardial ischemia. FASEB J. 1991;5:2029–2034. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.5.7.2010056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Linas SL, Whittenburg D, Parsons PE, Repine JE. Ischemia increases neutrophil retention and worsens acute renal failure: role of oxygen metabolites and ICAM-1. Kidney Int. 1995;48:1584–1591. doi: 10.1038/ki.1995.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rabb H, Mendiola CC, Saba SR, Dietz J, Smith CW, Bonventre JV, et al. Antibodies to ICAM-1 protect kidneys in severe ischemic reperfusion injury. Biochem Biophys Res Com. 1995;211:67–73. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rabb H, O'Meara YM, Maderna P, Coleman P, Brady HR. Leukocytes, cell adhesion molecules and ischemic acute renal failure. Kidney Int. 1997;51:1463–1468. doi: 10.1038/ki.1997.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takada M, Nadeau KC, Shaw GD, Marquette KA, Tilney NL. The cytokine-adhesion molecule cascade in ischemia/reperfusion injury of the rat kidney. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:2682–2690. doi: 10.1172/JCI119457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hancock WW, Wang L, Ye Q. Chemokine-directed dendritic cell trafficking in allograft rejection. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2003;8:35–39. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Larsen CP, Morris PJ, Austyn JM. Migration f dendritic leukocytes from cardiac allografts into host spleens: a novel route for initiation of rejection. J Exp Med. 1990;171:307–314. doi: 10.1084/jem.171.1.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.El-Sawy T, Belperio JA, Strieter RM, Remick DG, Fairchild RL. Inhibition of polymorphonuclear leukocyte-mediated graft damage synergizes with short-term costimulatory blockade to prevent cardiac allograft rejection. Circulation. 2005;112:320–331. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.516708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.El-Sawy T, Miura M, Fairchild R. Early T cell response to allografts occurring prior to alloantigen priming up-regulates innate mediated inflammation and graft necrosis. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:147–157. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)63283-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morita K, Miura M, Paolone DR, Engeman TM, Kapoor A, Remick DG, et al. Early chemokine cascades in murine cardiac grafts regulate T cell recruitment and progression of acute allograft rejection. J Immunol. 2001;167:2979–2984. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.5.2979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Araki M, Fahmy N, Zhou L, Kumon H, Krishnamurthi V, Goldfarb D, et al. Expression of IL-8 during reperfusion of renal allografts is dependent on ischemic time. Transplantation. 2006;81:783–788. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000198736.69527.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Colletti LM, Remick DG, Burtch GD, Kunkel SL, Strieter RM, Campbell DA. Role of tumor necrosis factor-α in the pathophysiologic alterations after hepatic ischemia/reperfusion injury in the rat. J Clin Invest. 1990;85:1936–1943. doi: 10.1172/JCI114656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Daemen MARC, van de Ven MWCM, Heineman E, Buurman WA. Involvement of endogenous interleukin-10 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in renal ischemia-reperfusion injury. Transplantation. 1999;67:792–800. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199903270-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gurevitch J, Frolkis I, Yuhas Y, Lifschitz-Mercer B, Berger E, Paz Y, et al. Anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha improves myocardial recovery after ischemia and reperfusion. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;30:1554–1561. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(97)00328-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li D, Zhao L, Liu M, Du X, Ding W, Zhang J, et al. Kinetics of tumor necrosis factor alpha in plasma and the cardioprotective effect of a monoclonal antibody to tumor necrosis factor alpha in acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 1999;137:1145–1152. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(99)70375-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schulz R, Aker S, Belosjorow S, Heusch G. TNFalpha in ischemia/reperfusion injury and heart failure. Basic Res Cardiol. 2004;99:8–11. doi: 10.1007/s00395-003-0431-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chaudhari U, Romano P, Mulcahy LD, Dooley LT, Baker DG, Gottlieb AB. Efficacy and safety of infliximab monotherapy for plaque-type psoriasis: a randomized trial. Lancet. 2001;357:1842–1847. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)04954-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gottlieb AB, Chamian F, Masud S, Cardinale I, Abello MV, Lowes MA, et al. TNF inhibition rapidly down-regulates multiple proinflammatory pathways in psoriasis plaques. J Immunol. 2005;175:2721–2729. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.4.2721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Present DH, Rutgeerts P, Targan S, Hanauer SB, Mayer L, van Hogezand RA, et al. Infliximab for the treatment of fistulas in patients with Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1398–1405. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199905063401804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Targan SR, Hanauer SB, van Deventer SJ, Mayer L, Present DH, Braakman T, et al. A short-term study of chimeric monoclonal antibody cA2 to tumor necrosis factor alpha for Crohn's disease. Crohn's Disease cA2 study group. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1029–1035. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199710093371502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bolling SF, Kunkel SL, Lin H. Prolongation of cardiac allograft survival in rat by anti-TNF and cyclosporine combination therapy. Transplantation. 1992;53:283–286. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199202010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Imagawa DK, Millis JM, Olthoff KM, Seu P, Dempsey RA, Hart J, et al. Anti-tumor necrosis factor antibody enhances allograft survival in rats. J Surg Res. 1990;48:345–348. doi: 10.1016/0022-4804(90)90072-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin H, Chensue SW, Strieter RM, Remick DG, Gallagher KP, Bolling SF, et al. Antibodies against tumor necrosis factor prolong cardiac allograft survival in the rat. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1992;11:330–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seu P, Imagawa DK, Wasef E, Olthoff KM, Hart J, Stephens S, et al. Monoclonal anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha antibody treatment of rat cardiac allografts: synergism with low-dose cyclosporine and immunohistological studies. J Surg Res. 1991;50:520–528. doi: 10.1016/0022-4804(91)90035-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wei RQ, Schwartz CF, Lin H, Chen GH, Bolling SF. Anti-TNF antibody modulates cytokine and MHC expression in cardiac allografts. J Surg Res. 1999;81:123–128. doi: 10.1006/jsre.1998.5303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Corry RJ, Winn HJ, Russell PS. Primarily vascularized allografts of hearts in mice. Transplantation. 1973;16:343–350. doi: 10.1097/00007890-197310000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nozaki T, Rosenblum JM, Ishii D, Tanabe K, Fairchild RL. CD4 T cell-mediated rejection of cardiac allografts in B cell-deficient mice. J Immunol. 2008;181:5257–5263. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.8.5257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schenk AD, Nozaki T, Rabant M, Valujskikh A, Fairchild RL. Donor-reactive CD8 memory T cells infiltrate cardiac allografts within 24-h posttransplant in naive recipients. Am J Transplant. 2008;8:1652–1661. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02302.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Afanasyeva M, Georgakopoulos D, Belardi DF, Ramsundar AC, Barin JG, Kass DA, et al. Quantitative analysis of myocardial inflammation by flow cytometry in murine autoimmune myocarditis: correlation with cardiac function. Am J Pathol. 2004;164:807–815. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63169-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.El-Sawy T, Fahmy NM, Fairchild RL. Chemokines: directing leukocyte infiltration into allografts. Curr Opin Immunol. 2002;14:562–568. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(02)00382-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schenk AD, Gorbacheva V, Rabant M, Fairchild RL, Valujskikh A. Effector functions of donor-reactive CD8 memory T cells are dependent on ICOS induced during division in cardiac grafts. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:64–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02460.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Coito AJ, Binder J, Brown LF, de Sousa M, Van de Water L, Kupiec-Weglinski JW. Anti-TNFα treatment down-regulates the expression of fibronectin and decreases cellular infiltration of cardiac allografts in rats. J Immunol. 1995;154:2949–2958. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Imagawa DK, Millis JM, Olthoff KM, Seu P, Dempsey RA, Hart J, et al. The role of tumor necrosis factor in allograft rejection. II. Evidence that antibody therapy against tumor necrosis factor-alpha and lymphotoxin enhances cardiac allograft survival in rats. Transplantation. 1990;50:189–193. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199008000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cumberbatch M, Dearman RJ, Kimber I. Langerhans cells require signals from both tumour necrosis factor-alpha and interluekin-1-beta for migration. Immunology. 1997;92:388–395. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1997.00360.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Enk AH, Katz SI. Early molecular events in the induction phase of contact sensitivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:1398–1402. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.4.1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chang RJ, Lee SH. Effects of interferon-γ and tumor necrosis factor-α on the expression of Ia antigen on a murine macrophage cell line. J Immunol. 1986;137:2853–2856. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Deepe GS, Jr, Gibbons RS. TNF-α antagonism generates a population of antigen-specific CD4+CD25+ T cells that inhibit protective immunity in murine histoplasmosis. J Immunol. 2008;180:1088–1097. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.2.1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Valencia X, Stephens G, Goldbach0-Mansky R, Wilson M, Shevach EM, Lipsky PE. TNF downmodulates the function of human CD4+CD25hi T-regulatory cells. Blood. 2006;108:253–261. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-11-4567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nadkarni S, Mauri C, Ehrenstein MR. Anti-TNF-α therapy induces a distinct regulatory T cell population in patients with rheumatoid arthritis via TGF-β. J Exp Med. 2007;204:33–39. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ricciardelli I, Lindley KJ, Londer M, Quaratino S. Anti tumour necrosis-α therapy increases the number of FOXP3+ regulatory T cells in children affected by Crohn's disease. Immunology. 2008;125:178–183. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2008.02839.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schenk S, Kish DD, He C, El-Sawy T, Chiffoleau E, Chen C, et al. Alloreactive T cell responses and acute rejection of single class II MHC disparate heart allografts is under strict regulation by CD4+CD25+ T cells. J Immunol. 2005;174:3741–3748. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.6.3741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Langrehr JM, Gube K, Hammer MH, Lehmann M, Polenz D, Pascher A, et al. Short-term anti-CD4 plus anti-TNF-α receptor treatment in allogeneic small bowel transplantation results in long-term survival. Transplantation. 2007;84:639–646. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000280552.85779.d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]