Abstract

Developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH) is a disabling condition that, depending on geography, can afflict between 20% and 80% of patients with end-stage arthritis of the hip. Despite its prevalence, the etiology of this disease remains unknown. DDH is a complex disorder with both environmental and genetic causes. Based on the literature the candidate genes for the disease are HOXB9, collagen type I α1, and DLX 3. The purpose of our study was to map and characterize the gene or genes responsible for this disorder by family linkage analysis. We recruited one 18-member, multigeneration affected family to provide cheek swabs and blood samples for isolation of DNA. Amplified DNA underwent a total genome scan using GeneChip Mapping 250 K Assay (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA). We observed only one region with a LOD score greater than 1.5: a 4 Mb region on chromosome 17q21.32, yielding a LOD score of 1.82. While a LOD score of 1.82 does not meet the accepted standard for linkage we interpret these data as suggesting the responsible gene could be linked to this region, which includes a cluster of homeobox genes (HOX genes) that are part of the developmental regulatory system providing cells with specific positional identities along the developing joint and spine. Discovering the genetic basis of the disease would be an important step in understanding the etiology of this disabling condition.

Introduction

Developmental dysplasia of the hip, previously known as congenital dislocation of the hip, is a frequently disabling condition characterized by incomplete formation of the acetabulum and/or femur leading to frequent subluxation or dislocation of the hip, suboptimal joint function, and accelerated wear of the articular cartilage resulting in arthritis. This condition affects one in 1000 newborn infants in the United States [34]. The prevalence of the disease is even higher in some parts of the world such as Japan, Italy, and other Mediterranean countries [28]. Because of its high prevalence and the undesirable consequences, a screening program is in place in nearly every country that involves clinical examination of the hip of the newborn [29]. Although relatively accurate for detecting gross dislocation or dislocatable hips, the examination cannot detect milder degrees of hip dysplasia [35]. In fact, the dynamic nature of the condition prompted experts to change its name from the traditional “congenital dislocation of the hip” to “developmental dysplasia of the hip.” The reason behind this change two decades ago was twofold. First, the pathology of the disorder varies per patient and does not consistently result in complete dislocation, but instead in subluxation or dysplasia. Second, should any form of the condition occur, it often happens postnatally and therefore cannot be termed truly congenital [16]. Moreover, many patients affected by the condition do not discover their diagnosis until later years of life when arthritis of the hip is instigated [23]. Over the past 20 years, “developmental dysplasia” has become more widely preferred than the misleading “congenital dislocation,” encompassing a wider spectrum of forms of the condition than earlier [2, 16]. Developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH) is therefore a complex disorder with both environmental [29] and genetic causes.

Although DDH presents with varying intensity in affected individuals, as determined by the degree of femoral head undercoverage, it also may often affect members of a single family [31]. Based on its pattern of presentation in families, the condition is believed to have a strong genetic basis [35]. Genome-wide scans of large affected families have yielded linkage to chromosomes 4q35, 13q22, and 16p, but no gene mutations in these regions have been found [17, 19]. Linkage to chromosome 12q13, where the collagen type 2-α1 and vitamin D receptor are located, was recently excluded as were two polymorphic sites within the COL1A1 gene [28]. A recent genetic association study of 335 affected and 622 control individuals found an association of a GDF5 single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) with DDH [5] (Table 1). Developmental dysplasia of the hip is also seen among dogs, affecting some pedigrees much more commonly. Based on linkage studies in large canine pedigree studies, veterinary researchers have proposed a genetic basis for the disease and have made substantial progress in mapping this disorder [21, 30]. Although no mutations in canine genes have been definitely linked to DDH various genetic loci in large canine pedigrees have been linked to DDH.

Table 1.

Summary of findings of genetic studies of nonsyndromic DDH and early-onset hip osteoarthritis

| Author (year) | Type of study | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Rouault et al. (2009) [27] | Pilot candidate locus association study | HOXB9 and COL1A1 association with DDH not supported in study of small regional French population |

| Dai et al. (2008) [5] | Candidate locus association study of 335 CDH subjects, 622 control subjects with candidate region | Significant association of GDF5 SNP with CDH |

| Rubini et al. (2008) [28] | Linkage exclusion | COL2A1 and vitamin D receptor excluded from linkage to DDH |

| Mabuchi and Nakamura (2006) [19] | Whole genome linkage | DDH in one large Japanese family linked to chromosome 13q |

| Loughlin et al. (2006) [18] | Candidate locus association study | Calmodulin promoter polymorphism not associated with DDH in UK white population |

| Jiang et al. (2005) [11] | Linkage exclusion | Two polymorphic sites within the COL1A1 gene found not to be linked to DDH in 81 small Chinese families |

| Mototani et al. (2005) [22] | Candidate locus association study | A functional polymorphic SNP in promoter of the Calmodulin gene found to be associated with hip osteoarthritis in Japanese population |

| Jiang et al. (2003) [12] | Candidate locus linkage study | Association of one allele of one microsatellite marker (D17S1820) on chromosome 17q21 with CDH phenotype in 101 Chinese families |

| Granchi et al. (2002) [7] | Candidate locus association study | Pilot study suggests Type II collagen and vitamin D receptor polymorphism might be associated with risk of osteoarthritis in patients with DDH |

| Ingvarrson et al. (2001) [10] | Whole genome linkage study of large Icelandic family | Locus on chromosome 16p linked to early osteoarthritis of the hip |

| Cilliers and Beighton (1990) [4] | Whole genome linkage of large Africaaner family | Premature (Beukes) degenerative osteoarthritis of the hip mapped to 11 cM region on chromosome 4q35 |

DDH = developmental dysplasia of the hip; CDH = congenital dislocation of the hip; SNP = single nucleotide polymorphism.

The familial inheritance patterns and a higher concordance rate between identical twins (41.4%) compared with that between fraternal twins (2.8%) strongly support genetic transmission among humans [34, 35]. There is another reason to believe that a single-gene or multiple-gene mutation may be implicated in this condition. Developmental dysplasia of the hip can be associated with other conditions such as clubfoot, renal malformations, and cardiac anomalies [13]. In fact, DDH is not uncommonly part of a syndrome affecting multiple systems in the body [13]. A majority of the patients with DDH, however, have an isolated condition with unilateral or bilateral hip disease.

Based on the strong evidence of a genetic contribution to the etiology of DDH, we wondered, without making any assumptions about where potentially causative mutations reside, whether we could identify a genetic haplotype that was uniquely shared by all affected members and not present in unaffected members of the family in this study, elucidating the etiology of their disorder.

Patients and Methods

Our institutional prospective database on joint arthroplasty was used to identify patients with DDH. Initially, our electronic database of over 22,000 patients undergoing hip arthroplasty was scanned to identify patients with DDH (International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision [ICD-9] codes 745.30 and 755.63). We identified 234 patients. We believed some patients with DDH undergoing THA might have been coded under end-stage arthritis (ICD-9 code 715.15). Relying on the notion that most patients with DDH require THA at a younger age, as the next step, we identified all patients younger than age 45 in the database institution. This resulted in the identification of an additional 2450 patients. The radiographs of all 2684 patients were then reviewed and appropriate measurements made to confirm or refute the diagnosis of DDH. After radiographic review, 435 of the approximately 22,000 patients (or about 2%) were believed to have DDH. All of these patients were contacted and ask to return for followup to obtain blood samples and/or buccal swabs for analysis. To date, 130 patients from 28 families have returned and donated DNA samples. At the time of this writing, the analysis had been completed in one 18-member, multigeneration family whose proband is severely affected with DDH. All 18 family members consented to study participation and were evaluated both clinically and radiographically by the senior author (JP). Before the initiation of this study, Institutional Review Board approval was obtained.

All consenting individuals had an anteroposterior and a cross-leg lateral radiograph of the hip performed as a routine. Other radiographs such as the faux profile to assess anterior coverage or abduction views to assess joint congruity were also performed in patients with DDH contemplating joint preservation surgery. Radiographs for each subject were measured by one of four experienced orthopaedic surgeons with the senior author (JP) confirming measurements for each subject. Analog radiographs were measured manually using an electronic goniometer, and digital radiographs were measured using software with an incorporated angle measurement system. Radiographic diagnosis of dysplasia was made based on standard definition [8, 24, 25]. Individuals were deemed to have DDH if one or more of the following was present: (1) Tönnis angle greater than 10° and/or (2) center-edge angle less than 20° [6]. Other measurements included the extrusion index, extent of lateral and superior migration of the femoral head, femoral neck angle, and posterior and anterior acetabular coverage (Table 2) [26]. The diagnosis of DDH was based on these parameters. Patient 001 was the proband in this study. This patient had a hip replaced because of DDH. The preoperative radiographs demonstrated severe arthritis that prevented us from making some of the measurements accurately. Individuals with acetabular retroversion and abnormal extrusion indices that differed from the norm by one standard deviation (Table 3) were categorized as “possible” dysplasia for the purpose of statistical analysis. No family members had been diagnosed with DDH at birth, but rather were diagnosed later in life.

Table 2.

Radiographic evaluation performed on members of the affected family*

| Family member | Age (years) | Shenton’s line | Center edge angle | Tönnis (degrees) | Extrusion index (mm) | Anterior acetabular coverage | Posterior acetabular coverage | Femoral neck angle | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Left | Right | Left | Right | Left | Right | Left | Right | Left | Right | Left | Right | Left | Right | ||

| 001 | 39 | ||||||||||||||

| 009 | 11 | D† | D | 12° | 18° | 24° | 24° | 16 | 16 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 140° | 150° |

| 011 | 42 | D | ND‡ | 3° | 6° | 20° | 24° | 28 | 28 | 15% | 10% | 40% | 20% | 142° | 146° |

| 004 | 6 | ND | ND | 25° | 25° | 8° | 12° | 14 | 15 | 20% | 30% | 70% | 50% | 134° | 132° |

| 005 | 18 | ND | ND | 25° | 26° | 12° | 12° | 16 | 16 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 136° | 136° |

| 006 | 41 | ND | ND | 32° | 28° | 12° | 12° | 18 | 18 | 30% | 30% | 60% | 70% | 130° | 126° |

| 008 | 13 | ND | ND | 28° | 32° | 10° | 6° | 14 | 14 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 154° | 148° |

| 014 | 64 | ND | ND | 18° | 22° | 0° | 0° | 14 | 18 | 20% | N/A | 80% | 60% | 133° | 134° |

| 007 | 28 | ND | ND | 24° | 22° | 12° | 10° | 10 | 10 | 20% | 30% | 70% | 50% | 144° | 144° |

| 010 | N/A | ND | ND | 26° | 22° | 5° | 5° | 3 | 0 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 143° | 161° |

| 002 | 45 | ND | ND | 26° | 26° | 8° | 16° | 10 | 10 | 20% | 20% | 80% | 80% | 138° | 134° |

| 012 | 49 | ND | ND | 17° | 24° | 0° | 0° | 3 | 3 | 15% | 20% | 70% | 80% | 132° | 130° |

| 013 | N/A | ND | ND | 22° | 22° | 22° | 16° | 5 | 6 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 132° | 130° |

| 003 | 49 | ND | ND | 22° | 20° | 14° | 16° | 10 | 10 | 30% | 20% | 70% | 70% | 124° | 124° |

| 016 | 61 | N/A | ND | 32° | 30° | 0° | 2° | 6 | 6 | 30% | 30% | 70% | 70% | 126° | 130° |

| 020 | 66 | ND | ND | 32° | 32° | 12° | 9° | 12 | 12 | 20% | 20% | 60% | 60% | 138° | 142° |

* The diagnosis of developmental dysplasia of the hip was made based on these measurements. (Affected members of this family are bold.); †disrupted; ‡nondisrupted; D = disrupted, ND = nondisrupted; N/A = not available.

Table 3.

Data on mean, SD, and range of normal values of radiographic measurements [25]

| Variable | Mean | SD | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Center edge angle | 23.5° | 7.8° | 0°–44° |

| Tönnis (degrees) | 10.8° | 7.6° | −7°–32° |

| Extrusion index (mm) | 8.4 | 2.6 | 2–15 |

| Femoral neck angle | 137.3° | 9.0° | 110°–154° |

SD = standard deviation.

Cheek swab or serum DNA gathered from family members was isolated using the QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit and amplified using the REPLI-g Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to protocol. Amplified DNA was then processed according to the GeneChip Mapping 250 K Assay Kit as recommended by the manufacturer (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA). Briefly, after Nsp I digestion, fragmented DNA was ligated to adaptor followed by PCR amplification. The PCR product was hybridized to the GeneChip Mapping 250 K Nsp Array and processed with the Fluidics Station and the GeneChip Scanner 3000 (Affymetrix). To eliminate uninformative markers and spurious calls, the following filters were applied to the data set. SNPs were selected for analysis that (1) generated calls for each family member; (2) had confidence scores less than 0.3 (confidence scores are inversely related to reliability); (3) were polymorphic with a minor allele frequency of 0.2 or more; and (4) did not generate inheritance errors. This filtering process brought the original 262,314 SNPs down to 6840.

Model-based and model-free multipoint LOD score analysis was performed using the software MERLIN Version 1.1.2 (www.sph.umich.edu/csg/abecasis/Merlin/). In the model-based analysis, to account for the diagnostic uncertainty in DDH, we divided individuals into two liability classes with different genetic penetrances (Table 4). Multipoint model-based LOD score analysis over the entire human genome, excluding the sex chromosomes, was performed.

Table 4.

Genetic penetrance classes

| Liability class | Individuals in each class | Homozygous for normal allele | Heterozygous | Homozygous for mutated allele |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1, 9, 11 | 0 | 0.8 | 0.8 |

| 2 | 4, 5, 6, 8, 13, 14 | 0.001 | 0.8 | 0.8 |

Penetrance is the probability of a given individual to be affected given that he or she carries zero, one, or two copies of the disease allele. Liability Class 1 contains individuals with three or more radiographic signs of DDH (1, 9, and 11). We have assigned a 0% probability of affection to individuals in this liability class if they have two normal alleles, and conservatively, we have assigned an 80% penetrance to carriers of one or two mutated alleles. Liability Class 2 contains individuals with one or two radiographic signs of DDH (4, 5, 6, 8, 13, and 14). Individuals in this class who happen to be carriers of the mutated allele (either homozygotes or heterozygotes) have the same probability of being affected of 0.8. If an individual has no mutated allele, we assume a probability of affection equal to the incidence of the disorder in the overall population, one per 1000 live births, or 0.001.

The analysis conducted assumes autosomal-dominant transmission of the affected allele. We reanalyzed the family using model-free analysis that makes no assumptions about the mode of transmission of this disorder. Individuals with any sign of DDH were included in this analysis (1, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9, 11, 13, and 14). Results of this analysis produced a linked region on chromosome 17 identical to that found by the model-based analysis using two liability classes as mentioned but with a lower maximum LOD score (data not shown).

Results

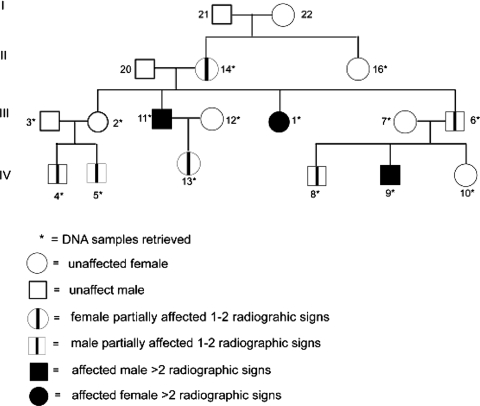

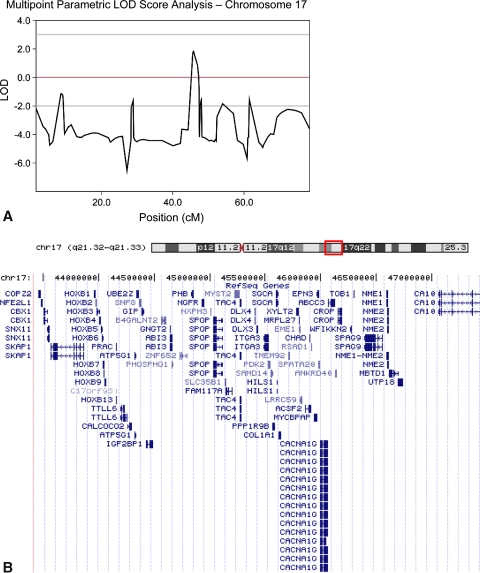

Based on the data in one family of 18 members in three generations, the DDH phenotype had an autosomal-dominant transmission (Fig. 1). X-linked inheritance was ruled out based on male-to-male transmission of the disease in this pedigree. The maximum multipoint LOD score (1.82) occurred at SNP rs16949053, located 45,844,439 base pairs from the p-term of chromosome 17, with a score of 1.82 (Fig. 2A). The region of positive LOD score extended from rs2597165 to rs996379 for approximately 4 Mb.

Fig. 1.

This pedigree illustrates one large family showing transmission of the disease through three generations. Symbols are explained in the figure key.

Fig. 2A–B.

(A) This graph shows the multipoint parametric analysis of the human chromosome 17. The maximum LOD score is 1.8221 at SNP rs16949053 located 45,844,439 base pairs from p- term of chromosome 17. (B) This figure shows an ideogram of chromosome 17 with the box depicting the approximate location of the candidate region. Below this is an enlarged view of the 4.0-Mb candidate region showing the position of the 73 transcripts contained in the region [14]. Reprinted with permission from http://genome.ucsc.edu/cite.html.

The second largest LOD score, on chromosome 16, was 1.38 at rs11866385 at position 10,016,159. However, the two flanking markers both had negative LOD scores, thus limiting the positive LOD score region to a very small interval of approximately 470 Kb. No other genomic region yielded LOD scores greater than 0.5.

Discussion

The focus of our study is to map and characterize the gene or genes responsible for this disorder by family linkage analysis. We therefore asked whether we could find a genetic haplotype that was uniquely shared by all affected members and not present in unaffected members of the family in this study, elucidating the etiology of their disorder.

Important limitations to this study include both the relatively small family size as well as the diagnostic uncertainty, both of which limit statistical power. A LOD score of 1.82 does not meet the accepted standard for linkage. Therefore, these findings should be viewed conditionally. As elaborated subsequently, the value of our study is that it provides supportive evidence for the biologic importance of this candidate region found to be significant in canine studies and in studies by other investigators studying DDH-affected families in China.

The linkage analysis of one multigeneration affected family in this study has demonstrated that DDH does indeed show genetic inheritance with an autosomal-dominant mode of transmission. Furthermore, the mutated gene for the condition appears linked to a region 4 Mb in size on chromosome 17q21. The fact that a genome scan of all human chromosomes produces just one plausible candidate region adds credence to the notion that a DDH-causing mutation resides there for this family. Indeed, there are a number of attractive candidate genes in this region (Fig. 2B). These genes were chosen among all genes (approximately 70 genes; see Fig. 2B) within the chromosome 17q21 region defined by our data on the basis of whether their known function might explain the biologic origins of DDH. The entire HOXB cluster of homeobox genes is contained in the proximal end of this region. The HOXB cluster encodes genes that are part of the developmental regulatory system that provides cells with specific positional identities along the developing spine. One gene in particular, HOXB9, is expressed in human embryo from 5 to 9 weeks, a period that coincides with primordial hip girdle formation [1]. In addition to appropriate temporal expression, it is expressed in the lumbar, sacral, and caudal regions of the forming provertebra during this time [15]. PAX1, another transcription factor responsible for the development of the hip girdle in the chicken, is known to interact with several members of the HOX gene family [20].

Other attractive candidates in this region include collagen type I-α1 (COL1A1) and DLX3 (Distal-less homeobox 3). A polymorphism in the collagen type I-α1 gene might influence hip development [11]. Bone fragility and in its more severe forms, blue sclera and short stature, characterize various forms of osteogenesis imperfecta that are the result of mutations in this major component of connective tissue [3]. Other mutations in COL1A1 result in Ehlers-Danlos syndrome characterized by laxity of the skin and joints. Still other polymorphisms in the first intron of COL1A1 are correlated to bone mass and osteoporotic fracture [32].

Although polymorphisms in the PCOL2 and Sp1 transcription factor binding sites of the COL1A1 gene do not appear associated with DDH in the Chinese population, COL1A1 mRNA and protein expression in the hip capsule of DDH-affected children was reportedly decreased compared with age- and gender-matched controls [11, 33]. These observations suggest that polymorphisms other than PCOL2 and Sp1 may be influencing COL1A1 expression in these affected individuals. DLX3 is a member of a family of transcription factors, including Runx2, that regulate the expression of osteocalcin during fetal mouse development [9].

Our findings help confirm those of Jiang et al. in 2003 who found after analyzing 101 members of Chinese families, that the DDH locus was associated with a marker (D17S1820) that is included in our chromosome 17 candidate region [12]. Additional support for the biologic importance of this region in the etiology of DDH comes from recent studies by Marschall and Distl, in which a quantitative trait locus for hip dysplasia on canine chromosome 9 is syntenic to chromosome 17q21 on the human genome where our candidate gene locus resides [21]. In addition to analyzing the results of a second multigenerational family, we are in the process of sequencing one of a number of these candidate genes.

In a small pilot genetic association study, Rouault and coinvestigators recently found no association of DDH with HOXB9 and COL1A1 in a small regional French population in which the incidence of this disorder was elevated [27]. Although an intriguing preliminary observation, the limited geographic sampling of this study does not preclude either of the genes playing a causative role in other populations. It is highly probable that DDH is genetically heterogeneous because hip formation involves the activation of numerous genes during development. Indeed, similar contradictory results have surfaced in the past that can be explained by population differences or small sample size and limited statistical power to detect genetic association. Recently, a polymorphism in the Calmodulin (CALM) promoter is associated with hip osteoarthritis in the Japanese population and decreases transcription of the gene in vitro and in vivo [22]. In a subsequent study, the CALM promoter polymorphism was excluded in a UK white population [18].

Our data suggest the presence of a disease-associated mutation/polymorphism in a region of chromosome 17q21 in the affected members of the family in this study. Because our finding, that of Jiang et al. [12] in the Chinese population, and those of the investigators studying the canine hip dysplasia [21] coincide, it is possible to hypothesize that mutations in candidate genes in this region could play a more prevalent role in causing susceptibility to this disorder.

We have chosen to compensate for the diagnostic uncertainty of DDH in this study by using reduced penetrance and creating liability classes. Penetrance is the proportion of individuals with a mutation causing a particular disorder who exhibit clinical symptoms of that disorder. The use of liability classes in this study allows for the retention of the statistical power generated by our severely affected family members [1, 9, 11] but still accounts for the diagnostic uncertainty of other possibly affected members.

We identified a single genetic locus linked to DDH in one multigeneration North American family. Our evidence suggests this locus is on human chromosome 17q21. We have identified a few potential candidate genes and are actively searching for mutations in a number of them by automated DNA sequence analysis. Identification of mutations or susceptibility-inducing polymorphisms in asymptomatic individuals with DDH might allow implementation of appropriate care in the future.

Acknowledgments

We thank Stephanie Barr, BS, for contributing to data collection; Javad Mortazavi, MD, Camilo Restrepo, MD, Orhan Bican, MD, and S. Mehdi Jafari, MD, for measuring radiographs for diagnostic purposes; and Charlene Williams, PhD, Kathryn Scott, BS, and Mark Bowser, BS, for contributing to data analysis.

Footnotes

Each author certifies that he or she has no commercial associations (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

Each author certifies that his or her institution approved the human protocol for this investigation, that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research, and that informed consent for participation in the study was obtained.

References

- 1.Anonymous. HXB9_HUMAN UniProtKB Swiss. Available at: http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P17482#section_comments. Accessed July 1, 2009.

- 2.Brand RA. 50 years ago in CORR: congenital dislocation of the hip—its causes and effects. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:1015–1016. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0167-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Byers PH, Steiner RD. Osteogenesis imperfecta. Annu Rev Med. 1992;43:269–282. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.43.020192.001413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cilliers HJ, Beighton P. Beukes familial hip dysplasia: an autosomal dominant entity. Am J Med Genet. 1990;36:386–390. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320360403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dai J, Shi D, Zhu P, Qin J, Ni H, Xu Y, Yao C, Zhu L, Zhu H, Zhao B, Wei J, Liu B, Ikegawa S, Jiang Q, Ding Y. Association of a single nucleotide polymorphism in growth differentiate factor 5 with congenital dysplasia of the hip: a case-control study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2008;10:R126. doi: 10.1186/ar2540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Delaunay S, Dussault RG, Kaplan PA, Alford BA. Radiographic measurements of dysplastic adult hips. Skeletal Radiol. 1997;26:75–81. doi: 10.1007/s002560050197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Granchi D, Stea S, Sudanese A, Toni A, Baldini N, Giunti A. Association of two gene polymorphisms with osteoarthritis secondary to hip dysplasia. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;403:108–117. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200210000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harris WH. Etiology of osteoarthritis of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1986;213:20–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hassan MQ, Javed A, Morasso MI, Karlin J, Montecino M, Wijnen AJ, Stein GS, Stein JL, Lian JB. Dlx3 transcriptional regulation of osteoblast differentiation: temporal recruitment of Msx2, Dlx3, and Dlx5 homeodomain proteins to chromatin of the osteocalcin gene. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:9248–9261. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.20.9248-9261.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ingvarsson T, Stefansson SE, Gulcher JR, Jonsson HH, Jonsson H, Frigge ML, Palsdottir E, Olafsdottir G, Jonsdottir T, Walters GB, Lohmander LS, Stefansson K. A large Icelandic family with early osteoarthritis of the hip associated with a susceptibility locus on chromosome 16p. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:2548–2555. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200111)44:11<2548::AID-ART435>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiang J, Ma HW, Li QW, Lu JF, Niu GH, Zhang LJ, Ji SJ. Association analysis on the polymorphisms of PCOL2 and Sp1 binding sites of COL1A1 gene and the congenital dislocation of the hip in Chinese population [in Chinese] Zhonghua Yi Xue Yi Chuan Xue Za Zhi. 2005;22:327–329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jiang J, Ma HW, Lu Y, Wang YP, Wang Y, Li QW, Ji SJ. Transmission disequilibrium test for congenital dislocation of the hip and HOXB9 gene or COL1AI gene [in Chinese] Zhonghua Yi Xue Yi Chuan Xue Za Zhi. 2003;20:193–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karapinar L, Surenkok F, Ozturk H, Us MR, Yurdakul L. The importance of predicted risk factors in developmental hip dysplasia: an ultrasonographic screening program [in Turkish] Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 2002;36:106–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kent WJ, Sugnet CW, Furey TS, Roskin KM, Pringle TH, Zahler AM, Haussler D. The human genome browser at UCSC. Genome Res. 2002;12:996–1006. doi: 10.1101/gr.229102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kessel M. Respecification of vertebral identities by retinoic acid. Development. 1992;115:487–501. doi: 10.1242/dev.115.2.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klisic PJ. Congenital dislocation of the hip—a misleading term: brief report. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1989;71:136. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.71B1.2914985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Loughlin J, Mustafa Z, Irven C, Smith A, Carr AJ, Sykes B, Chapman K. Stratification analysis of an osteoarthritis genome screen-suggestive linkage to chromosomes 4, 6, and 16. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;65:1795–1798. doi: 10.1086/302685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Loughlin J, Sinsheimer JS, Carr A, Chapman K. The CALM1 core promoter polymorphism is not associated with hip osteoarthritis in a United Kingdom Caucasian population. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2006;14:295–298. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2005.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mabuchi A, Nakamura S, Takatori Y, Ikegawa S. Familial osteoarthritis of the hip joint associated with acetabular dysplasia maps to chromosome 13q. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;79:163–168. doi: 10.1086/505088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Malashichev Y, Borkhvardt V, Christ B, Scaal M. Differential regulation of avian pelvic girdle development by the limb field ectoderm. Anat Embryol (Berl) 2005;210:187–197. doi: 10.1007/s00429-005-0014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marschall Y, Distl O. Mapping quantitative trait loci for canine hip dysplasia in German Shepherd dogs. Mamm Genome. 2007;18:861–870. doi: 10.1007/s00335-007-9071-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mototani H, Mabuchi A, Saito S, Fujioka M, Iida A, Takatori Y, Kotani A, Kubo T, Nakamura K, Sekine A, Murakami Y, Tsunoda T, Notoya K, Nakamura Y, Ikegawa S. A functional single nucleotide polymorphism in the core promoter region of CALM1 is associated with hip osteoarthritis in Japanese. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:1009–1017. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murphy SB, Ganz R, Muller ME. The prognosis in untreated dysplasia of the hip. A study of radiographic factors that predict the outcome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77:985–989. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199507000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murphy SB, Kijewski PK, Millis MB, Harless A. Acetabular dysplasia in the adolescent and young adult. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990;261:214–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nelitz M, Guenther KP, Gunkel S, Puhl W. Reliability of radiological measurements in the assessment of hip dysplasia in adults. Br J Radiol. 1999;72:331–334. doi: 10.1259/bjr.72.856.10474491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reynolds D, Lucas J, Klaue K. Retroversion of the acetabulum. A cause of hip pain. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1999;81:281–288. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.81B2.8291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rouault K, Scotet V, Autret S, Gaucher F, Dubrana F, Tanguy D, Yaacoub El Rassi C, Fenoll B, Ferec C. Do HOXB9 and COL1A1 genes play a role in congenital dislocation of the hip? Study in a Caucasian population. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2009;17:1099–1105. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2008.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rubini M, Cavallaro A, Calzolari E, Bighetti G, Sollazzo V. Exclusion of COL2A1 and VDR as developmental dysplasia of the hip genes. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:878–883. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0120-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stein-Zamir C, Volovik I, Rishpon S, Sabi R. Developmental dysplasia of the hip: risk markers, clinical screening and outcome. Pediatr Int. 2008;50:341–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2008.02575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Todhunter RJ, Bliss SP, Casella G, Wu R, Lust G, Burton-Wurster NI, Williams AJ, Gilbert RO, Acland GM. Genetic structure of susceptibility traits for hip dysplasia and microsatellite informativeness of an outcrossed canine pedigree. J Hered. 2003;94:39–48. doi: 10.1093/jhered/esg006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tonnis D, Heinecke A. Acetabular and femoral anteversion: relationship with osteoarthritis of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999;81:1747–1770. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199912000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Uitterlinden AG, Burger H, Huang Q, Yue F, McGuigan FE, Grant SF, Hofman A, Leeuwen JP, Pols HA, Ralston SH. Relation of alleles of the collagen type Ialpha1 gene to bone density and the risk of osteoporotic fractures in postmenopausal women. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1016–1021. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199804093381502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang EB, Zhao Q, Li LY, Shi LW, Gao H. Expression of COL1a1 and COL3a1 in the capsule of children with developmental dislocation of the hip [in Chinese] Zhongguo Dang Dai Er Ke Za Zhi. 2008;10:493–496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weinstein SL. Natural history of congenital hip dislocation (CDH) and hip dysplasia. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1987;225:62–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilkinson JA. Etiologic factors in congenital displacement of the hip and myelodysplasia. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;281:75–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]