Abstract

Aim

The PRISMA-France pilot project is aimed at implementing an innovative case management type integration model in the 20th district of Paris. This paper apprehends the emergence of two polarized views regarding the progression of the model's spread in order to analyze the change management enacted during the process and its effects.

Method

A qualitative analysis was conducted based on an institutional change model.

Results

Our results suggest that, according to one view, the path followed to reach the study's current level of progress was efficient and necessary to lay the foundation of a new health and social services system while according to the other, change management shortcomings were responsible for the lack of progress.

Discussion

While neither of these two views appears entirely justified, analyzing the factors underlying their differences pinpoints some of the challenges involved in managing the spread of an integrated service delivery network. Meticulous preparation for the change management role and communication of the time and effort required for a wholesale institutional change process may be significant factors for a successful integrative endeavor.

Keywords: change management, institutional change, integrated care, networks

Introduction

Background

In recent years, healthcare reforms undertaken by most industrialized countries have been based upon the principle of integration. The fragmentation, which characterizes these complex health and social care systems, as well as the complexification caused by the turn to home care necessitated the development of integration devices to ensure the coherence, efficiency and quality of services [1]. The necessity of these devices is enhanced when they concern the beneficiaries of long-term chronic care, notably frail elderly people [2]. The PRISMA-France pilot study is a research project aimed at evaluating the process of implementing such a device, the PRISMA1 model, in France. The PRISMA model is an integrated service delivery model developed in Quebec, Canada. It is a coordination type integration model that consists of six essential components: a case management process, a single entry point, a standardized multi-client assessment tool, a standardized service planning tool, a shared clinical file and inter-organizational partnership at the strategic, tactical and clinical levels of the organization [3]. The French experiment was initiated through the Ministry of Health and the National Solidarity Fund for Autonomy. The pilot project was assigned to a steering committee and was supported by a multidisciplinary research team. The steering committee was composed of representatives of funding agencies, a public health and geriatric research team based at a Paris hospital and of a project team. The steering committee's first mandate was to create a national strategic consultation panel involving state representatives. The national strategic consultation panel was created and it approved the PRISMA-France study on January 17, 2006. The PRISMA-France pilot study was carried out in the highly complex environment of the French health and social care system. This complexity is inherent to its lengthy evolution and particularly to its financing which is not ensured by a single payer, but rather, by four levels of government: the State, the region, the department and the municipality. Furthermore, an important share of services' costs is absorbed by major health insurance funds who determine their coverage according to individual's professional statuses. The multiplicity of financing sources produces a vast diversity of normative systems, which prescribe access to services, and consequently a highly competitive environment. This ‘free-market’ atmosphere is exacerbated by the politicization of public services created by the determination of the four governmental levels to maintain their prerogatives in the health and social care domain. In the gerontological field, the absence of a pivotal organization responsible for the evaluation of elderly people's needs and consequent service provision adds to the system's fragmentation [4, 5].

Problem statement

With much remaining to be accomplished in terms of integration in both Europe [6] and North America [2], it appears as many countries do not have the knowledge, resources or political push to conduct integrative initiatives. The World Health Organization [7] indicates that “there are many more examples of policies in favour of integrated services than there are of actual implementation”. Since the many countries that have decided to pursue the integration route have historically been developed with a hospital at their core [3], moving to an integrated way of functioning represents a significant change endeavour. Notwithstanding the fact that healthcare policies of various natures fail to be implemented due to lack of managerial expertise [8], the implementation of integrative policies appears particularly complex given that it does not rely on a single provider organization [9]. Hence, as Goodwin et al. [10] exposed in their systematic literature review on the management of networks—which are relevant to the broader objective of integrating services—it is imperative to learn more about the leadership and management required to implement integrated care. The PRISMA-France pilot study provided an opportunity to study the change management strategy used to manage an integrative process. While the pilot study was conducted at three sites deliberately contrasted in terms of services and population density, the study described in this article solely focuses on the change management enacted in one setting, namely the 20th district of the mega-urban Paris setting. The objective of its change managers was to favour the integration of the gerontological health and social care services dispensed on the 20th district by arranging meetings between organizations of the 20th district and fostering the development of a shared language and common processes.

Theory and methods

Theory

Two distinct but complementary theoretical models were employed to analyze the change process revealed by the PRISMA France pilot study. Hinnings et al.'s [11] institutional model of change was utilized to delimit the various phases of the pilot study's process, while Greenhalgh et al.'s [12] conceptual framework for the spread of innovations in service organizations was employed to define the change management approach adopted by the change managers of the PRISMA France pilot study.

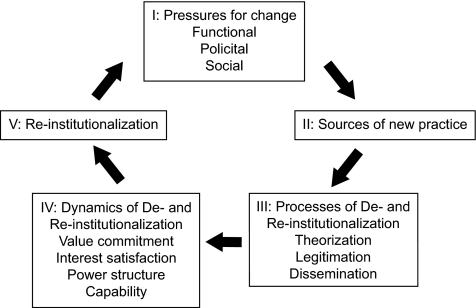

To begin with, the foundation of Hinnings et al.'s [11] institutional model of change is the notion that an institution is a “socially constructed, routine-reproduced programs or rules system” [13, p. 149] and, therefore, that institutional change is the “movement from one institutionally prescribed and legitimated pattern of practices to another” [11, p. 304]. The model is notable for its focus on innovation in organizational fields, which are “sets of diverse organizations engaged in a similar function that, in the aggregate, constitute an area of institutional life” [11, p. 305]. It draws from a social constructivist perspective and stipulates that change involves processes of de- and re-institutionalization initiated by deviations from a coded prescription of reality that must be legitimized. These coded prescriptions of reality are composed of institutional archetypes generated from outside the organization and associated with the demands of powerful actors, such as the state. To summarize, Hinnings et al.'s model (Figure 1) suggests that institutional change involves an event that destabilizes established practices (stage I), a state of instability which allows the entry and operation of entrepreneurs (stage II), the theorization, legitimation and dissemination of their new ideas (stage III), conflicts and disputes based upon organizational dynamics (commitment to the values embodied by the innovation, extent to which the innovation serves their interests, level of engagement of the most powerful actors, technical and social ability to implement the change) regarding the formalization of new practices (stage IV) and the achievement of a certain degree of stability which may be considered re-institutionalization (stage V).

Figure 1.

Institutional model of change [11].

The selection of this model to analyze the change process in the PRISMA-France pilot project was appropriate since it involved numerous organizations in the Paris health and social services system rather than just one. The frequent referral by Hinnings et al. [11] to the institutional nature of changes in the health and social services field and more particularly to the archetypal magnitude of changes brought about by the spread of integrated service designs was another reason for its use. Hence, in this paper the Paris health and social services system is considered an organizational field, the PRISMA model a new institutional archetype, and the actions of the managers of the institutional change as aimed at delegitimizing the current institutional archetype, legitimizing the new archetype and disseminating its components.

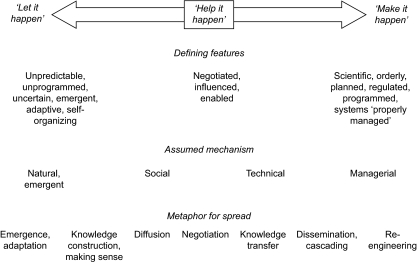

Secondly, Greenhalgh et al.'s [12] conceptual framework for the spread of innovations in service organizations features three main categories of spread: a) ‘let it happen’, which is essentially emergent and ‘unprogrammed’; b) ‘help it happen’, which is essentially social and negotiated; and c) ‘make it happen’, which is essentially programmed and managed (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Greenhalgh et al.'s [12] conceptual framework for the spread of innovations in service organizations.

These three categories initially influenced the choice of the PRISMA-France change managers' approach and, hence, were utilized to analyze the change management they enacted and the response of the innovation's adopters. As a matter of fact, the individuals responsible for adopting and using the innovation were named ‘adopters’, while the individuals responsible for conceiving, promoting and managing the innovation's implementation were named ‘change managers’. The term ‘adopters’ refers to the strategic and tactical level organizations of the 20th district of Paris. The grouping of strategic level organizations, named consultation panel, was comprised of representatives of State and departmental organizations responsible for the financing and steering of the Parisian gerontological field, and of representatives of health insurance funds. The grouping of tactical level organizations, named services' coordination committee, was comprised of the managers of the health and social care organizations responsible for the provision of services to the elderly population. The change managers of the PRISMA-France pilot study were the PRISMA-France steering committee, comprised of representatives of the PRISMA-France pilot-study's funding agencies and of the geriatric research team mandated to implement the model, and the PRISMA-France project team, composed of a head of project, a project leader and a local coordinator for the 20th district. The steering committee was responsible for the implementation's strategy, while the project team was responsible for the implementation's operationalization. The change managers were mandated by the study's financing agencies to lead the implementation process.

The objective of this study was to analyze the change management approach enacted by the change managers and its effects on the integrative change process.

Methods

Employing a multiple case study methodology, data of various natures were collected in each of the study's three settings [14]. However, the results presented in this article strictly concern a share of the extensive qualitative data body that was collected in the Paris setting between June 2006 and February 2009. During this period, the research team collected data using semi-structured interviews with strategic and tactical level adopters, as well as recorded all meetings of the strategic level consultation panel and tactical level services' coordination committee. Two types of data were analyzed: transcripts of meetings of the strategic level adopters (n=11) and transcripts of interviews with individual strategic level adopters (n=2) and with individual tactical level adopters (n=5). The decision to analyze both types of data was based upon the temporal triangulation concept that seeks to reveal the similarities and dissimilarities of data produced in different contexts [15]. The entirety of meeting transcriptions of the strategic consultation panel available at the time of the analysis was utilized, while only the interviews with the most involved and knowledgeable individual members of the strategic and tactical levels, which included questions related to the project's management, were utilized. These interviews included questions aimed at understanding the adopters' appreciation of the implementation's progression and of its management by the change managers. Data were analyzed using the framework approach [16] which guided our analysis towards answering the study's objective, i.e. to understand the change management approach enacted by the change managers and its effects on the integrative change process. The concepts of Hinnings' model orientated the analysis regarding the change process's progression while Greenhalgh's framework directed the analysis of the change management approach. The analysis of these data was performed by the primary author of the article and yielded many categories whose composition were verified by the second and last authors. Interview transcriptions and meeting transcriptions were analyzed in the same fashion. The first author of this paper was mandated by the PRISMA-France project team to analyze its management practices in order to learn from its experience and was thus free to analyze the data. The results presented in this paper were discussed amongst the authors but were not censored by the authors who were both judge and party. All quotes were originally obtained in French, translated by the primary author of this paper and verified by a translator. Each quote is identified as being from members of the strategic or tactical level organizations.

Results—How and why did polarized views of the change process emerge

Overview of the PRISMA-France pilot project in light of the institutional model of change

The PRISMA-France pilot project, like any institutional change initiative, arose out of an organizational field that was under demographic and social pressure to change. The split between the health and social aspects was considered the primary shortcoming of the French health and social services system. Coordination efforts to link these parallel worlds were judged too fragile; it was the good will of individuals rather than the strength of the structure that kept the train on the track. What makes the PRISMA-France study particularly interesting is that the new idea it aims to implement was previously theorized in another context. Hence, the efforts of the PRISMA-France change managers are dedicated to ‘re-theorizing’ an existing model, i.e. transforming a previously polished new idea into a different form adapted to the Paris context. This particular aspect warranted legitimizing the experimental value of a model that emerged from a different system. In fact, most of the first two years of the study were dedicated to re-theorizing and legitimizing four essential components of the model (inter-organizational partnership, case management, single entry point, and standardized multi-client assessment tool) in the Paris context. Thus, the PRISMA-France pilot project is still in the early stages of its de-institutionalization and re-institutionalization process since only partial acknowledgment of the need to improve services to the elderly and a tentative belief that the PRISMA model may bring about such improvements were achieved. In the eyes of the adopters, the model has acquired variable levels of legitimacy to be tested, but is still far from being accepted as the natural arrangement for all organizations within their field.

Polarized views

Polarized views and opinions regarding the progress made by the PRISMA-France pilot project emerged. The first view, held by strategic as well as tactical level adopters, considers the time required (January 2006–July 2008) to lay the foundations of the PRISMA project as having been used steadily and efficiently. The time was not excessive because adopters worked continuously: “Even if it is true that it's taking a long time, (…) we never stopped.” [tactical] The slowness of the decisional process and getting bogged down in political debates are recognized as sources of inefficiency, but according to this view are still beneficial since they allowed learning and advancement: “With the amount of time we spent working on this, we still made some progress, at least in our own minds.” [tactical] Achieved through discussions that recognized the ambitions of each organization, the current progress was defined as pragmatic and tangible: “It's always the same people, it's always the same subjects, it's always progressive, it's always anchored in reality.” [strategic] Those holding this view consider the creation of a legal structure, which was the most time-consuming aspect, as a necessity without which it would have been impossible to launch the experimental case management practices. The legal issues relating to the potential liability of an employee put to the disposition of the project and practising as a case manager would have been too significant to avoid the creation of such a structure. According to this view, the major efforts made to lay the groundwork of the experiment generated frustration, but also and above all maturation.

According to the second view, held mainly by tactical level adopters, the delays required to launch the project were unpredictable and unproductive. Similarly to those who hold the opposing view, these adopters think that the process is evolving slowly, but are frustrated by the study's lack of progress: “It's frustrating! We're still waiting to know how it will start and feel that the decision-makers are very remote” [tactical]. They cannot understand the time and effort required to develop the legal structure and they think it stifled the dynamic of the change process which fed off the organizations' initial commitment: “I have a hard time understanding why it takes 6 months to come up with this document (…) Now we're paying for it because everybody feels, I think, when we talk amongst each other… It stopped the momentum that was there.” [tactical] The implications of the issues addressed by the legal structure are not contested by the adherents of this view, but they think a more pragmatic solution was viable. The delay required to create the legal structure is partly attributable to the organizational field leaders and strategic level members' difficulty recognizing the added value of the PRISMA model, but mostly to their desire to maintain their status: “This legal constraint exists, but it is also used by some to keep their power (…) there is a complicated leadership game being played in the district.” [tactical] From this perspective, the concrete problems generated by a less programmed pilot project would have offered superior legitimizing conditions: “You must start small for problems to arise gradually and when it happens, I have the impression that even more problems arise.” [tactical] Furthermore, working to get things underway more quickly would have fostered the commitment of the genuinely engaged organizations and identified the ones involved for the wrong reasons: “First, you do, then you evaluate what they have done, to make things transparent, that is the goal of a pilot project.” [tactical]

Enactment and experience of a ‘help it happen’ change management approach

The most committed change managers of the PRISMA-France pilot study acknowledged the value of a negotiated spread and promised to enact a ‘help it happen’ change management approach. In fact, the majority of participants, whether affiliated to the strategic or tactical level, viewed the pilot study as being managed from a ‘help it happen’ position: “We have the impression that there is a mastery of the whole [process] which ensures that spontaneity is relatively controlled without being destroyed.” [strategic] The ‘bottom-up’ inclination of the change managers was recognized: “We always tried to progress through discussion, by consulting one another and having to negotiate some points…” [tactical] Being driven by an experimental mechanism designed more to learn from the Paris reality than to force it to change, one strategic level adopter thought the change managers managed this confrontation in a non-directive but reassuring way: “You mother us a lot (…) you respect our prerogatives, you respect each of our professional traditions, you don't make any promises on our behalf and you don't push anyone to do so”.

The value of the ‘help it happen’ management approach was appreciated by strategic and tactical level adopters: “We need a framework that provides general guidance to prevent people going off in all directions, that defines the basics and then lets people organize themselves locally.” [tactical] The management approach enacted by the PRISMA-France change managers was considered a motivating mechanism as well as a means to achieve local adaptation. By reducing the workload of the adopters of the PRISMA model, which is especially important in the early stages of a project, the management approach favoured the beginnings of a minimal investment that has the potential to grow: “It was a way of getting everyone, from the top and the bottom, to dip their toes in the water, (…) to taste the benefits…” [strategic].

On the other hand, many shortcomings of the change management approach enacted by the change managers were underlined. First, the initial opacity of the management approach employed was criticized: “The whole picture, or at least parts of it, are starting to be visible (…) We finally see that the methods, the organization have been anticipated from an experimental standpoint.” [strategic] While the value of the ‘help it happen’ approach was progressively recognized, it appears that the adopters were not prepared to appreciate that the approach's most valuable principle is to ensure they recover advocacy on the change process. This seemed to have prevented the adopters from acknowledging that with the ‘help it happen’ approach, the pace of advancement is partly dependent on the quality of their investment, as acknowledged by one strategic level adopter: “You made us all play our own role, we are on a timetable that suits us. I think that the tactical level people are in a hurry to get to work, but at the same time they don't want to work under any old conditions.” [strategic]

Secondly, conceptualization difficulties of adopters, such as understanding the meaning of the fundamental concept of integration, were attributed to inconsistencies in training or supervision: “The ‘troops’, it's understandable, were not involved in all the planning. Their supervision wavered frequently, it's only natural [tactical]”. Adopters did, however, recognize that some grey areas resulted from their lack of investment in the project: “Even then, I noticed that some things that were said in meetings are still being questioned today.” [tactical] Furthermore, adopters blamed the change managers for not giving enough feedback or communicating the progress achieved by the change process. Adopters thought the success achieved should have been promoted across all organizational levels: “It's a matter of support, convincing people, knowing how to highlight everything that is positive.” [strategic]

Finally, while the adopters recognized that the primary value of the change management approach was its openness to local adaptation, they thought this adaptation process could have been guided more wisely. They thought the change managers could have reduced delays and avoided a loss of motivation by developing their knowledge of issues relating to organizational integration before being confronted with the possibilities and limitations of the Paris context. The time taken to create the legal structure was partly attributed to a lack of pre-retheorizing preparation: “I don't want to blame anyone, but I have to say that it could have been thought out better in advance…” [tactical] From this standpoint, it appears that the ‘change managers’ planned the clinical deployment of the model much more than the spread process required to attain this stage: “There was some planning, I think, on the part of the professionals and elderly people, but probably not enough consideration of the legal aspects and one another's responsibilities in the venture.” [tactical]

In fact, in many instances, the adopters requested more ‘top-down’ influence in order to prevent further shilly-shallying: “The role of the pilot of the local level is to say: Ok, here we are, we've talked enough, we heard you, we took in consideration some of your observations and comments, today we finalize things.” [strategic] The change managers did not capitalize on situations where the adopters may have accepted a more directive approach: “PRISMA is a national project with different levels. We are at the local level; there are things that we apply without losing our professional soul or convictions.” [tactical] By doing so, the change managers could have prevented some of the lingering shilly-shallying.

Influential institutional dynamics

This section is devoted to the organizational dynamics which may have mediated the adopters' response to the institutional change process as managed by its change managers. The ‘institutional dynamics’, i.e. dynamics that apply to clusters of organizations or overarch the organizational field, are discussed in this section.

In regards to commitment to the project and conception of its interests, various motives underpinned the involvement of the organizational entrepreneurs. On the positive side, organizations expressed the value of using their experimental involvement to learn from each other in a total quality process and to develop inter-organizational relationships: “On the positive side of things, it gave us other opportunities to meet and talk to each other, that's always fun, but it was a bit too costly in terms of time.” [tactical] Each organization had its own agenda, was committed to the PRISMA-France pilot project for its own reasons, but seemed mostly interested in protecting itself from the possibility of being excluded from the initial testing of a new institutional archetype: “They clearly see the intellectual value of participating and the ‘protection interest’ of participating in the project, so they will do it without additional resources.”2 [strategic]

These attractions, however, were counterbalanced by some negative conditions. First and foremost, as indicated above, while integration relies on the acknowledgment of the need to work together for the benefit of all, organizations in the Paris health and social services system were limited by self-promotion and the desire to maintain their status. The inclination of the organizations to protect their territories, and thus their funding, rather than share them is inherent in the competitive environment in which they operate. This ‘open’ health and social services market fuels the greed of the organizations involved and is the main adversary of integration. The institutionalization of competition diminishes the organizations' conception of the PRISMA-France pilot project as serving their interests and makes them less interested in change than concerned about maintaining their reason for being: “I think that everybody's fear is maybe to lose this recognition, saying: We, as a structure, won't be recognized anymore for what we are doing today because we will be subsumed in the whole.” [tactical] Furthermore, the gerontological field is rife with new projects that are not always consistent with one another, which reduces the desire of organizations to invest in them properly: “With this flood of things we don't even read about them anymore…. We have one thing, then it is invalidated by another thing two weeks later, which is itself invalidated two weeks after that!” [strategic]. With rising scepticism adding to the organizations' tentativeness with regard to change, the adoption of a ‘wait-and-see’ attitude towards the PRISMA-France project became the norm.

A majority of the strategic and tactical level adopters said that moving to a new institutional structure required strong institutional support, i.e. from the political leaders. Although they recognized the value of the pilot project in developing new ideas and creating evidence to sustain their legitimacy, they stressed that no ‘revolutionary’ enterprise could be successful without strong support from the authorities in the field: “If a public policy says that services must be integrated in every territory and that it will go like this, bam, bam, bam,…then it has to be done! (…) That's why I say that it is po-li-tics that decide, not the experts.” [tactical] In reality, however, an informal and blurred institutional commitment to the project was seen: “We have the impression that everything is kind of up in the air.” [tactical] The rarity of national committee meetings, lack of institutional level representatives from the strategic level and lax project supervision were indicative of the limited institutional commitment to the project. Adopters thought institutional leaders should have done more: “Explain the meaning of the project, say that it is a real goal, get someone from the national committee to talk about it (…). That's how a general motivates his troops, right? A general takes the lead when he is with his army.” [tactical]

The lack of institutional support for the PRISMA-France project was used by the adopters as a justification for their own tentativeness: “We could say that the partners are not all in good faith, they use this institutional absence.” [tactical] The strategic level adopters expressed the need for more encouragement from the top, i.e. be empowered to employ a more ‘make it happen’ approach: “You asked me how much time I spent on it; probably not enough due to the lack of encouragement from my superiors.” [strategic] The lack of decisiveness of the strategic level, composed of departmental representatives, could be due to the fact that the government did not define or communicate the extent of their mandate and authority: “I don't know if the national strategic decisional panel gave the department people a precise mission. The national committee did not say: The departmental committee in each department, these are your prerogatives, we defined this and your responsibility is that.” [tactical] This lack of direction further favoured the adoption of a ‘wait-and-see’ attitude to the legitimacy of the PRISMA model as the new organizational archetype. With the motivation of the troops compromised, the project was perceived not as moving forward, but as going round in circles: “There is nothing worse than to take a decision and not apply it because that destroys all credibility. Saying: ‘yes’, then two years later, nothing is done (…) You cannot step on the brakes and the gas at the same time, if you do, you lose control.” [tactical]

Even if for a majority of adopters the weak organizational commitment to the PRISMA-France pilot project is partly attributable to the lack of support of the institutional leaders, they also questioned their very ability to do so: “Can the government system we have today, which is a mosaic, really impose, enforce common procedures? And make sure they will be followed? Today, I really don't know.” [tactical] The partitioning of power throughout the multiple health and social services decision-making echelons was detrimental to the establishment of the atmosphere of trust required to initiate an integrated enterprise. In the long run, even though the structure of the Paris health and social services system hinders its leader's ability to unequivocally support any innovative enterprise, it appears that its decision to approve and launch the PRISMA-France project while leaving its organizational participants feeling that nobody was at the wheel will prove to be very detrimental: “There is a conductor of the orchestra, but if he does not take the decision to tell Mr. X to play… That's it! That's why I say there will most probably not be a revolution in the health and social services organization.” [tactical]

Discussion—What to learn from the emergence of these polarized views

The emergence of polarized views regarding the progress of the PRISMA-France pilot project can be explained by two main factors. First, the different standpoints and variable levels of ‘change experience’ of the organizational participants may have influenced their ability to consider the change process in its entirety. Secondly, notwithstanding the undoubted shortcomings of the change management approach enacted by the change managers, the less than full consideration of the influence of the Paris health and social services context impacted on the change managers' management legitimacy and resulting adopters' response.

While the emergence of polarized views is used here to introduce our results, it is a valuable result in itself. Nolte [17] identified competing priorities, and especially waiting-times, of integrative initiative stakeholders as a significant challenge for future endeavours. The confusion that resulted from the strategic level mainly considering the process as making progress and the tactical level mainly considering the process as standing still, strongly supports this statement. Hinnings et al. acknowledged the laboriousness of initiating an institutional change process: “the process of theorization and legitimization of a new idea are difficult to get underway” [11, p. 313]. Hence, the role of the change managers of an integrative model may be to ensure that the scope of an institutional change process is understood and that all types of progress are communicated across the organizational field. If this had been done in the present case, the change managers may have induced the tactical level adopters to see the development of the legal structure as a structural achievement likely to engender behavioral gains [18] rather than as time-consuming and futile. It is from such a holistic perspective that the evaluation grid utilized by the change managers indicates that the project achieved an experimental implementation rate of 24% [19].

Furthermore, lessons may be drawn from the negative and positive effects, as expressed by the participants, of the change management enacted by the change managers. While the ‘help it happen’ approach may have favoured the adaptation of the PRISMA model and helped the project's continuity, fostering the engagement of organizations through a management approach customized to organizational participants' capabilities may also have given adopters an excuse for their ‘wait-and-see’ posture. Adapting an innovation to its adopter's context of operation is a crucial condition for the success of a change process [20], but a too lenient management approach may have fostered lethargy and a lack of interest. The experimental nature of the PRISMA-France pilot study may have been sufficiently unbinding to get ‘innovation apprehensive’ organizations on board without having to adopt, in addition, a ‘soft help it happen’ approach. Management's relaxed approach, especially in regard to the adopters' level of commitment and work schedule, may have fostered the participation of organizations more interested in seeing what was in the ‘boutique’ [2] for them than in engaging in a potentially revolutionary enterprise.

If from this point of view, the adoption of a ‘firm help it happen approach’ is hypothesized to be preferable, we should note that the adopters would also like to have been given more direction. In fact, a contingency approach may be a better choice. While Beer and Nohria [21] advised change managers to embody a symbiotic change management approach, they acknowledged that change from a more top-down approach to a more bottom-up approach may be preferable to the reverse. Hence, the requisition of the adopters may be advisable for future integrative change managers. Enacting a management approach that would progress from right to left on Greenhalgh et al.'s management framework [12] may eliminate organizations unprepared to take on a founder's role from the start of an institutional change process and foster the participating organizations' accountability. Also, in light of the delays caused by the development of the legal structure, meticulous preparation of the change managers for its guidance role may enhance efficiency. Change managers adopting a ‘help it happen’ approach may benefit greatly from developing their expertise regarding the possibilities and limitations of an organizational field in order to properly orient the bottom-up creativity they wish to cultivate [22]. Moreover, regarding the initial opacity of the management approach favoured by the change managers, it may require as much effort and energy to specify, explain and legitimize the change management approach to be employed by the change managers towards the adopters as it does to implement the innovation it promotes. By doing so, the fit of the management approach to the adopters' needs may be targeted, as is the adaptation of the innovation itself to the local conditions. In our view, it is of the utmost importance to consider an innovation as an object composed of intervention mechanisms [23], in this case represented by the six components of the PRISMA model, and of change management mechanisms, which must also be considered and planned.

In the PRISMA-France case, the lack of top-down influence from the change managers can be attributed not only to their intention to generate the positive effects of the ‘help it happen’ approach, but also by their lack of authority, which in turn can be explained by the lack of leadership shown by the institutional field leaders. The multiplicity of funding systems, and consequently of decision-making organizations that characterized the French health and social services system, seem to prevent change initiatives from benefiting from unequivocal institutional support [19]. In a context where no ultimate decision-maker exists, the clear-cut definition of the scope of each decisional level's authority would be very beneficial. The institutional leaders, the change managers and the managerial adopters, which may progressively convert to the role of change manager once convinced of the innovation's legitimacy, may thus be enabled to deploy the particular abilities and knowledge inherent to their hierarchical position in order to foster the innovation adopters' commitment. Nevertheless, the management of the spread of an integrated care network from a ‘help it happen’ approach would require not assuming that the institutional leaders will play their roles flawlessly. Change managers may rethink and extend their ‘helping’ role to all levels of adopters in order to promote communication between institutional leaders and the bottom and, consequently, to diminish the bottom's sentiment of being very remote from the decision-makers. These observations should be viewed in light of the fact that our results are derived from a single, highly complex mega-urban case, where the process remains relatively juvenile.

Conclusion—How can polarized views be reconciled?

Without considering the opposing views regarding the study's progress, it is clear that the PRISMA-France pilot project was not supported by strong leadership from the institutional leaders, or by a consensual recognition of the urgent need to revolutionize the organization of the health and social services system from the bottom. The top seemed to be waiting for the bottom to produce sufficient evidence that the PRISMA model was suitable for the Paris context, while the bottom seemed to be waiting for a clear signal from the top that this initiative was worth investing in, more so than other inconclusive projects. While the management approach enacted by the PRISMA-France change managers could certainly have been improved, it did produce some positive effects. The management of the PRISMA-France pilot project engendered a sense of partnership through valuing local adaptation, allowing overworked organizations to participate through their assistance and helping to lay the foundations for the clinical phase of the study through negotiation. While it is true that the time taken gave adopters an excuse for their ‘wait-and-see’ posture, it was also productive in creating the basis of a central component of the PRISMA model: intra-organizational partnership. This progress, when viewed in light of the entire institutional change model, may in fact be very valuable. It may have been difficult to appreciate this feat from the viewpoint of the tactical level, but the experiment has already started; the PRISMA model was confronted with the reality of the Paris health and social services system from day one. Hence, we should consider the glass not as half full or half empty, but perhaps as one quarter full (after all, the evaluation grid does indicate a 24% implementation rate…). In hindsight, the experimental institutional change process would have benefited from better preparation of its change managers in order to foster patience from adopters of distinct hierarchical levels in moving from unstable to stable dissemination conditions. The most important roles of change managers may thus be to legitimize the length of an institutional change process to tenants of polarized viewpoints and to ensure that dissemination benchmarks are progressively attained in order to maintain the adopters' motivation and enable the transition from the ‘boutique’ to the institutional stage.

Acknowledgments

All authors would like to thank Catherine Perisset, Laurence Leneveut, Sylvie Lemonnier and Virginie Taprest-Raes and the clinical research unit of the Hôpital Européen Georges Pompidou. Without their active work, collaboration and support and the financial participation of the French Ministry of Health, the National Solidarity Fund for Autonomy and the Independents Workers Social Protection Organization, this study would not have been possible.

Footnotes

Program of Research on Integration of Services for Maintenance of Autonomy [3].

The organizations participating in the PRISMA-France pilot study are not given any additional funding.

Contributor Information

Francis Etheridge, Université de Sherbrooke, 1036, rue Belvédère Sud, Sherbrooke, Quebec, Canada J1H 4C4.

Yves Couturier, Université de Sherbrooke, 1036, rue Belvédère Sud, Sherbrooke, Quebec, Canada J1H 4C4.

Hélène Trouvé, Université Paris Panthéon Sorbonne, Hôpital Européen Georges-Pompidou, Pôle Urgences Réseaux, 20, rue Leblanc, 75908 Paris Cedex 15, France.

Olivier Saint-Jean, Hôpital Européen Georges-Pompidou, Chief of the Pôle Urgences Réseaux, 20, rue Leblanc, 75908 Paris Cedex 15, France.

Dominique Somme, Hôpital Européen Georges-Pompidou, Service de gériatrie, Pôle Urgences Réseaux, 20, rue Leblanc, 75908 Paris Cedex 15, France.

Reviewers

Laurann Yen, Research Fellow, Australian Primary Health Care Research Institute & Menzies Centre for Health Policy, Australian National University, Canberra, Australia

Trish Reay, PhD, Associate Professor, Strategic Management and Organization, University of Alberta School of Business, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada

One anonymous reviewer

References

- 1.Munday B. Services sociaux intégrés en Europe. [Integrated social care in Europe]. Strasbourg, France: Éditions du Conseil de l'Europe; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kodner DL. Whole-system approaches to health and social care partnerships for the frail elderly: an exploration of North American models and lessons. Health and Social Care Community. 2006;14(5):384–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2006.00655.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hébert R, Veil A, Raîche M, Dubuis MF, Dubuc N, Tousignant M. Evaluation of the implementation of PRISMA: a coordination-type integrated service delivery system for frail older people in Quebec. Journal of Integrated Care. 2008;16(6):4–14. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Couturier Y, Trouvé H, Gagnon D, Etheridge F, Carrier F, Somme D. Réceptivité d'un modèle québécois d'intégration des services aux personnes âgées en perte d'autonomie en France. [Receptivity of an integrative model of services for frail elderly people developed in Quebec in France]. Lien social et politiques; 62. (in press). [in French] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Somme D, Trouvé H, Couturier C, Carrier S, Gagnon D, Lavallart B, et al. PRISMA France: Programme d'implantation d'une innovation du système de soins et de services aux personnes en perte d'autonomie. Adaptation d'un modèle d'intégration basé sur la gestion de cas. [PRISMA France: Program of implementation of an innovation of the health and social care system for the frail elderly. Adaptation of an integrative model based on case management]. La Revue d'Épidémiologie et de Santé Publique. 2008b;56(1):54–62. doi: 10.1016/j.respe.2008.01.003. [in French] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vaarama M, Piper R. Managing integrated care for older people. European perspectives and good practices. Helsinki, Finland, Dublin, Ireland: Stakes and EHMA; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization. Technical brief No. 1 May 2008. Integrated health services – what and why? Geneva: WHO; 2008. [cited 2009 Nov 22]. Available at: http://www.who.int/healthsystems/technical_brief_final.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Longo F. Implementing managerial innovations in primary care: can we rank change drivers in complex adaptive organizations. Health Care Management Review. 2007;32(3):213–25. doi: 10.1097/01.HMR.0000281620.13116.ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edgren L. The meaning of integrated care: a systems approach. International Journal of Integrated Care [serial online] 2008 Oct 23;8 Available from: http://www.ijic.org/ [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goodwin N, 6 P, Peck E, Freeman T, Posaner R. Managing across diverse networks of care: lessons from other sectors. Report to the National Co-ordinating Centre for NHS Service Delivery and Organisation R&D (NCCSDO), January 2004. London: NCCSDO; 2004. [cited 2009 Jul 9]. Available at: http://www.sdo.nihr.ac.uk/files/adhoc/39-policy-report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hinnings CR, Greenwood R, Reay T, Suddaby R. Dynamics of change in organizational fields. In: Poole MS, Van de Ven AH, editors. Handbook of organizational change and innovation. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2004. pp. 304–23. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Macfarlane F, Bate P, Kyriakidou O. Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: systematic review and recommendations. The Milbank Quarterly. 2004;82(4):581–629. doi: 10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00325.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jepperson RL. Institutions, institutional effects and institutionalism. In: Powell WW, Dimaggio PJ, editors. The new institutionalism in organizational analysis. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1991. pp. 143–63. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yin RK. Case study research: design and methods. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muchielli A. Dictionnaire des méthodes qualitatives en sciences humaines. 2nd ed. [Dictionary of qualitative methods in social sciences]. Paris: Armand Collin; 2004. [in French] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N. Qualitative research in health care: analysing qualitative data. British Medical Journal. 2000 Jan 8;320(7227):114–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7227.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nolte E. Managing chronic illness in Europe – a comparative analysis. International Journal of Integrated Care [serial online] 2008 Jun 4; Annual Conference Supplement 2008. [cited 2009 Jul 9]. Available from: http://www.ijic.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ahgren B, Axelsson R. Evaluating integrated health care: a model for measurement. International Journal of Integrated Care [serial online] 2005 Aug 31;5 doi: 10.5334/ijic.134. Available from: http://www.ijic.org/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.PRISMA-France. Rapport PRISMA-France – Intégration des services aux personnes âgées: la recherche au service de l'action. [The PRISMA-France report – The integration of services for the elderly: research to serve action]. Paris: PRISMA-France; 2008. Dec, [cited 2009 Jul 9]. [in French]. Available from: http://www.ladocumentationfrancaise.fr/rapports-publics/094000078/index.shtml?xtor=EPR-526. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Couturier Y, Trouvé H, Gagnon D, Carrier S, St-Jean O, Somme D. Prior conceptions of integration and coordination as modulators of an innovation's adoption: the case of a pilot project targeting the implementation of a services' integration device in France. International Journal of Integrated Care [serial online] 2008 Jun 4; Annual Conference Supplement 2008. [cited 2009 Jul 9]. Available from: http://www.ijic.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beer M, Nohria N. Cracking the code of change. Harvard Business Review. 2000;78:133–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Amabile TM. Motivating creativity in organizations: on doing what you live and loving what you do. California Management Review. 1997;40(1):39–58. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pawson R, Greenhalgh T, Harvey G, Walshe K. Realist synthesis: an introduction. Manchester: University of Manchester; 2004. Aug, [cited 2009 9 Jul]. (ESRC Research Methods Programme, Working Paper Series August 2004; RMP Methods Paper 2/2004). Available at: http://www.ccsr.ac.uk/methods/publications/documents/RMPmethods2.pdf. [Google Scholar]