Abstract

To determine the effect of swine hepatitis E virus (HEV) infection on pregnant gilts, their fetuses, and offspring, 12 gilts were intravenously inoculated with swine HEV. Six gilts, who were not inoculated, served as controls. All inoculated gilts became actively infected and shed HEV in feces, but vertical transmission was not detected in the fetuses. There was no evidence of clinical disease in the gilts or their offspring. Mild multifocal lymphohistiocytic hepatitis was observed in 4 of 12 inoculated gilts. There was no significant effect of swine HEV on fetal size, fetal viability, or offspring birth weight or weight gain. The offspring acquired anti-HEV colostral antibodies but remained seronegative after the antibodies waned by 71 days of age. Swine HEV infection induced subclinical hepatitis in pregnant gilts, but had no effect on the gilts' reproductive performance, or the fetuses or offspring. Fulminant hepatitis associated with HEV infection was not reproduced in gilts.

Human hepatitis E virus (HEV) is the causative agent of acute non-A, non-B, and icterus-inducing hepatitis in humans and is characterized as a non-enveloped, single-stranded, positive sense RNA virus (1). Hepatitis E virus is considered to be enterically transmitted via the fecal-oral route. Swine HEV, first isolated from a pig in Illinois, is closely related to 2 human isolates of HEV (US-1 and US-2) identified in the United States (U.S.) (2). Cross species infection has been experimentally demonstrated; swine HEV infected rhesus monkeys and a chimpanzee, and the US-2 strain of human HEV infected pigs (3,4). These findings infer that swine may be an animal reservoir for HEV, raising concern that HEV is a potential zoonotic or xenozoonotic agent (5). Swine HEV is reportedly ubiquitous in the U.S. swine population (2). Furthermore, occupational exposure to swine, such as with swine farmers or veterinarians, poses a higher risk of HEV infection among these individuals, suggesting the possibility of animal-to-human transmission (6,7).

The course of hepatitis E in humans is self-limiting and chronic illness is not observed (1). Overall case mortality is low, ranging from 0.2% to 4%, although high mortality rates of 10% to 25% have been reported in pregnant women suffering from fulminant hepatitis associated with HEV. This particular presentation of hepatitis E mostly occurs in the 3rd trimester of pregnancy (8,9). Explanation for this phenomenon is still obscure. Vertical transmission of HEV via intrauterine infection was suggested as HEV RNA was detected in cord blood samples from infants born to mothers affected with acute fulminant hepatitis (10,11). Accordingly, an animal model would be useful to further the understanding of HEV-induced fulminant hepatitis in pregnant women. Non-human primates (cynomolgus macaques, chimpanzees, and rhesus monkeys) are susceptible to HEV infection and have been widely used in experimental models (4,12). However, pregnant rhesus monkeys inoculated intravenously with human HEV strain SAR-55 from Pakistan did not exhibit the characteristics of the fulminant hepatitis disease as seen in pregnant women. Neither a fatal effect of HEV infection on the mother or the fetuses, nor neonatal infection, was found in the study (3).

Since the discovery of swine HEV, experimental studies of the infection in growing pigs have been well described (3). Lack of an animal model for reproducing fulminant hepatitis E in pregnant women and the need for information regarding the effect of HEV infection in pregnant swine prompted us to investigate the effect of swine HEV infection in pregnant gilts during late gestation on dams, fetuses, and offspring, and to determine if the disease pattern of fulminant hepatitis E in pregnant women can be reproduced in pregnant swine.

Eighteen swine HEV-seronegative gilts (Sus scrofa domesticus), originating from the Iowa State University specific-pathogen-free herd were used and randomly assigned to swine HEV-inoculated group (n = 12) or sham-inoculated control group (n = 6). The experimental procedures were reviewed and approved by the Iowa State University Committee on Animal Care. The swine HEV inocula contained a titer of 104.5 50% pig infectious dose (PID50) per mL, which was equal to the titer used in a previous experimental infection of swine HEV study in growing pigs (3). Twelve gilts were intravenously inoculated via an ear vein at 78 to 80 d of gestation. Clinical observations (appetite, lethargy, icterus, or diarrhea) were conducted daily throughout the study and gilt rectal temperatures were measured for 14 d after inoculation. Five to 6 gilts (4 inoculated and 1 or 2 controls) were euthanized by intravenous administration of an overdose of sodium pentobarbital on 3 separate days as follows; 91 d of gestation (12 d postinoculation [DPI], 1 control and 4 inoculated), 105 d of gestation (26 DPI; 2 controls and 4 inoculated), or at 17 to 19 d after farrowing (55 DPI; 2 controls and 4 inoculated). One control gilt that had gone into estrus again at 21 d post-service and was reserviced immediately, was necropsied separately at 46 DPI or 81 d of gestation. Four, 8- to 10-day-old piglets from each of the 6 sows that farrowed were necropsied at 46 DPI. Gross examination of the reproductive tract and internal organs of the gilts and offspring was performed. At necropsy, the number of fetuses, fetal viability and condition, fetal weight, and fetal crown-rump length were recorded. A set of tissues including liver, gall bladder, uterus, ovary, salivary gland, duodenum, jejunum, ileum, colon, pancreas, tonsil, spleen, lymph nodes, heart, skeletal muscle, lung, and kidney were collected from each gilt for microscopic examination, using hematoxylin and eosin staining. A set of tissues collected from each pig included liver, brain, thymus, tonsil, spleen, lymph nodes, lung, kidney, heart, duodenum, jejunum, ileum, and colon. The same types of tissues (excluding lymph nodes) as collected from the pigs, plus the umbilical cord, were collected from fetuses for microscopic evaluation. Offspring were weighted at birth and periodically thereafter to evaluate weight gain. All surviving pigs were weaned at 18 d of age and pigs from control gilts were mixed with those from inoculated gilts. Blood samples from these pigs were periodically collected for HEV serology until 102 d of age.

Blood samples were collected from the gilts prior to and throughout the study for HEV serology, HEV RNA detection by a nested reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assay, and liver chemistry profiles (alkaline phosphatase, aspartate aminotransferase, gamma-glutamyl transferase, sorbitol dehydrogenase, and total bilirubin) by an automated analyzer (Hitachi 912; Roche, Indianapolis, Indiana, USA). Fecal samples were also collected at the same time to be tested for HEV RNA by RT-PCR. Overall, samples for RT-PCR testing included serum, feces, liver tissues, and bile obtained from the gilts, and serum and pooled tissues (liver, lung, kidney, spleen, and small intestines) obtained from 2 fetuses (both normal or 1 normal and 1 mummified fetus with crown-rump length more than 15 cm) per litter. A nested RT-PCR technique was performed as previously described (3). The enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for swine anti-HEV antibodies was performed as previously documented (2). The cut-off absorbance value used for positive samples was 0.3.

A commercial software package was used to perform statistical analyses (Statistix, version 4.0; Analytical software, Tallahassee, Florida, USA). Proportional reproductive data were tested by Fisher's exact test (proportion of normal, small, stillborn, or mummified fetuses/pigs). Other data (rectal temperatures, liver chemistry profile values, fetal weight and length, offspring birth weight, weight gain, and litter size) were calculated as mean ± standard deviation (s). Data were tested for statistical difference between inoculated and control groups using an analysis of variance (ANOVA). For all analyses, values of P < 0.05 were considered significant.

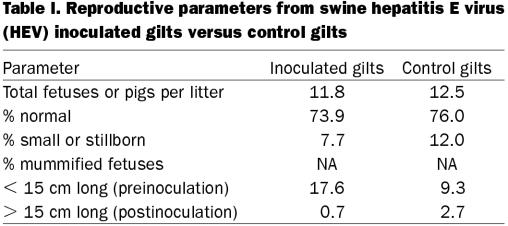

There were no clinical signs or fever observed in the inoculated gilts or their piglets (data not shown). Liver chemistry profile values were no different between inoculated and control gilts (data not shown). There were no significant differences between inoculated and control groups with regard to fetal weight and length, or offspring birth weight and weight gain (data not shown). None of the reproductive parameters from inoculated gilts were significantly different from control gilts (Table I). Although, the percentage of mummified fetuses in inoculated gilts was higher than control gilts, based on crown-rump lengths, the majority of these fetuses died prior to inoculation. Overall, litter size was relatively high for gilts and at necropsy many of the mummified fetuses were clustered together in one segment of the uterus, suggesting that fetal death occurred due to intra-uterine crowding. There were no significant gross lesions in any of the gilts, fetuses, or piglets. Mild multifocal lymphohistiocytic hepatitis associated with occasional individual hepatocyte necrosis was found in 4 of 12 inoculated gilts. Four inoculated gilts (including 2 of the gilts with hepatitis lesions) had mild multifocal lymphohistiocytic interstitial nephritis. There were no remarkable microscopic lesions in any tissues obtained from piglets or fetuses.

Table I.

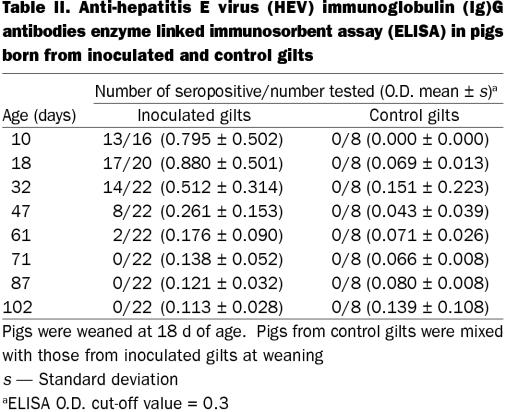

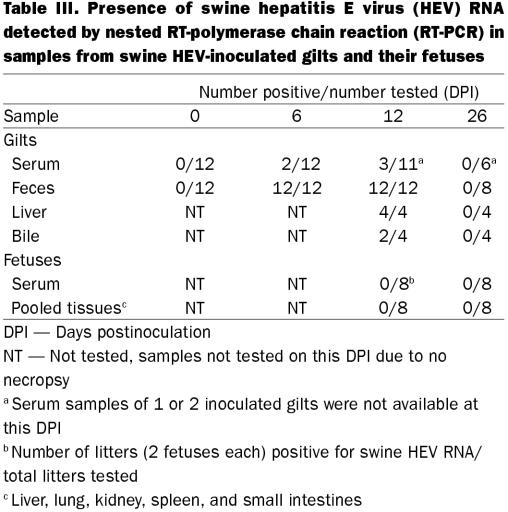

All except 1 of the inoculated gilts (7 of 8 gilts) seroconverted to anti-HEV by 19 DPI. Four inoculated gilts were necropsied at 12 DPI, hence their serum samples were not available for ELISA testing thereafter. All 8 remaining gilts subsequently acquired anti-HEV antibodies by 26 DPI and all 4 gilts that were allowed to farrow continued to be seropositive through to 47 DPI. All control gilts remained seronegative throughout the study. Detectable HEV antibodies were found in pigs from inoculated dams, when first sampled at 10 d of age. A proportion of the pigs continued to be seropositive until 61 d of age and all pigs were seronegative thereafter (102 d of age) (Table II). Results of the RT-PCR of samples obtained from swine HEV-inoculated gilts and their fetuses are summarized in Table III. All samples obtained from control gilts and their fetuses contained no detectable level of swine HEV RNA. Since experimental swine HEV infection is readily detected by anti-HEV ELISA assay, fecal samples obtained from piglets were not tested for HEV RNA (3,14).

Table II.

Table III.

Our findings demonstrated that there was no adverse effect of intravenous inoculation of pregnant gilts with U.S. swine HEV. Although the gilts shed swine HEV RNA in feces, there was no evidence of vertical transmission from dams to their fetuses. Pigs born to swine HEV-infected dams acquired anti-HEV immunoglobulin (Ig)G antibodies passively from colostrum and the passive antibodies persisted until the pigs were approximately 2 mo old. Based on our results, HEV-free pigs can be derived from HEV-infected dams by early weaning and segregation of the pigs from their dams.

Fulminant hepatitis E was not reproduced in pregnant rhesus monkeys intravenously inoculated with 105.5 50% monkey infectious dose (13,15). Similarly, fulminant hepatitis E was not reproduced in pregnant swine inoculated intravenously with swine HEV. In the current study, we used swine HEV inocula with a titer of 104.5 PID50. This inoculating dose has been repeatedly used and determined to be effective for inducing experimental HEV infection and mild hepatitis lesions in pigs (3,14). It is apparent that inducing experimental HEV infection via intravenous inoculation is more reproducible than via oral inoculation in non-human primates and swine (14,16). Perhaps, higher doses could result in clinical disease in the pregnant gilt model.

The characteristics of hepatitis lesions observed in the inoculated gilts are consistent with those previously documented in growing pigs and are reportedly milder in pigs inoculated with swine HEV than in pigs inoculated with human HEV (3). With regard to the interstitial nephritis lesions found in 4 of 12 inoculated gilts, the lesions are unlikely related to swine HEV infection since there was no such lesion found in growing pigs inoculated with swine HEV (3). These nephritis lesions may be attributable to previous episodes of ascending bacterial infection of the lower urinary tract. Recurrent lower urinary tract infections and nephritis in breeding aged pigs is common (17).

Footnotes

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. Robert H. Purcell and Suzanne U. Emerson of the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland for kindly providing the SAR-55 antigen and the swine HEV inocula. We also thank Crystal Gilbert for her assistance in PCR testing of swine HEV RNA. This research was funded by grants from the National Pork Board Pork Check Off Dollars and the Iowa Livestock Health Advisory Council.

Address all correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Brad Thacker; telephone: (515) 294-2283; fax: (515) 294-1072; e-mail: bthacker@iastate.edu

Received November 14, 2002. Accepted March 17, 2003.

References

- 1.Purcell RH. Hepatitis E virus. In: Fields BN, Knipe, DM, Howley, PM, eds. Fields Virology 3rd ed. Vol 2. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven Publishers, 1996:2831–2843.

- 2.Meng XJ, Purcell RH, Halbur PG, et al. A novel virus in swine is closely related to the human hepatitis E virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1997;94:9860–9865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Halbur PG, Kasorndorkbua C, Gilbert C, et al. Comparative pathogenesis of infection of pigs with hepatitis E virus recovered from a pig and a human. J Clin Microbiol 2001;39:918–923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Meng XJ, Halbur PG, Shapiro MS, et al. Genetic and experimental evidence for cross-species infection by swine hepatitis E virus. J Virol 1998;72:9714–9721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Yoo D, Giulivi A. Xenotransplantation and the potential risk of xenogenic transmission of porcine viruses. Can J Vet Res 2000;64:193–203. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Drobinec J, Favorov MO, Shapiro CN, et al. Hepatitis E virus antibody prevalence among persons who work with swine. J Infect Dis 2001;184:1594–1597. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Meng XJ, Wiseman B, Elvinger F, et al. Prevalence of antibodies to hepatitis E virus in veterinarians working with swine and in normal blood donors in the United States and other countries. J Clin Microbiol 2002;40:117–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Mast EE, Krawczynski K. Hepatitis E virus: an overview. Ann Rev Med 1996;47:257–266. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Shams R, Khero RB, Ahmed T, Hafiz A. Prevalence of hepatitis E virus (HEV) antibody in pregnant women of Karachi. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad 2001;13:31–35. [PubMed]

- 10.Khuroo MS, Kamili S, Jameel S. Vertical transmission of hepatitis E virus. Lancet 1995;345:1025–1026. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Kumar RM, Uduman S, Rana S, Kochiyil JK, Usmani A, Thomas L. Sero-prevalence and mother-to-infant transmission of hepatitis E virus among pregnant women in the United Arab Emirates. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2001;100:9–15. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Aggarwal R, Kamili S, Spelbring J, Krawczynski K. Experimental studies on subclinical hepatitis E virus infection in cynomolgus macaques. J Infect Dis 2001;184:1380–1385. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Tsarev SA, Tsareva TS, Emerson SU, et al. Experimental hepatitis E virus in pregnant rhesus monkeys: failure to transmit hepatitis E virus (HEV) to offspring and evidence of naturally acquired antibodies to HEV. J Infect Dis 1995;172:31–37. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Kasorndorkbua C, Halbur PG, Thomas PJ, Guenette DK, Toth TE, Meng XJ. Use of a swine bioassay and a RT-PCR assay to assess the risk of transmission of swine hepatitis E virus in pigs. J Virol Methods 2002;101:71–78. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Arankalle VA, Chadha MS, Banerjee K, Srinivasan MA, Chobe LP. Hepatitis E virus infection in pregnant rhesus monkeys. Indian J Med Res 1993;97:4–8. [PubMed]

- 16.Aggarwal R, Krawczynski K. Hepatitis E virus: an overview and recent advances in clinical and laboratory research. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2000;15:9–20. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.D'Allaire S, Drolet R. Culling and mortality in breeding animals. In: Straw B, D'Allaire S, Mengeling WL, Taylor DJ, eds. Diseases of Swine, 8th ed. Ames: Iowa State University Press, 1999:1003–1016.