Abstract

Objective

To synthesise estimates of the prevalence of cessation attempts among adolescent smokers generally, and according to age and level of cigarette consumption.

Data sources

PubMed, ERIC, and PsychInfo databases and Internet searches of central data collection agencies.

Study selection

National population‐based studies published in English between 1990 and 2005 reporting the prevalence, frequency and/or duration of cessation attempts among smokers aged ⩾10 to <20 years.

Data extraction

Five reviewers determined inclusion criteria for full‐text reports. One reviewer extracted data on the design, population characteristics and results from the reports.

Data synthesis

In total, 52 studies conformed to the inclusion criteria. The marked heterogeneity that characterised the study populations and survey questions precluded a meta‐analysis. Among adolescent current smokers, the median 6‐month, 12‐month and lifetime cessation attempt prevalence was 58% (range: 22–73%), 68% (range 43–92%) and 71% (range 28–84%), respectively. More than half had made multiple attempts. Among smokers who had attempted cessation, the median prevalence of relapse was 34, 56, 89 and 92% within 1 week, 1 month, 6 months, and 1 year, respectively, following the longest attempt. Younger (age<16 years) and non‐daily smokers experienced a similar or higher prevalence of cessation attempts compared with older (age ⩾16 years) or daily smokers. Moreover, the prevalence of relapse by 6 months following the longest cessation attempt was similar across age and smoking frequency.

Conclusions

The high prevalence of cessation attempts and relapse among adolescent smokers extends to young adolescents and non‐daily smokers. Cessation surveillance, research and program development should be more inclusive of these subgroups.

An estimated 150 million adolescents worldwide use tobacco. Approximately half of these young smokers will die of tobacco‐related diseases in later life.1 Adolescent smokers are also subject to more immediate health consequences, such as respiratory and non‐respiratory effects,2,3 changes in serum cholesterol4 and nicotine dependence and withdrawal.5 Although preventing the initiation of smoking remains a major goal of tobacco control, prevention programs directed at adolescents have shown limited effectiveness to date.6 Moreover, once adolescents start smoking, the impact of prevention programs, whether on experimental or regular smokers, is small and inconsistent across studies.7,8,9,10 It is estimated that adolescent smokers who reach a consumption level of at least 100 cigarettes will continue to smoke for another 16–20 years.11 Even brief periods of smoking cessation during adolescence have been associated with positive subjective health changes, such as improved respiratory health and a general sense of feeling healthier, fitter and more energetic.12,13

Among adolescents in the early stages of smoking onset, alternating periods of smoking and abstinence are common.14,15 Yet longitudinal studies show that only 3–12% of adolescent daily or regular smokers16,17,18,19,20 and 10–46% of adolescent non‐daily or occasional smokers18,20,21,22 no longer smoke 1–3 years later. This suggests that the likelihood of achieving abstinence, although generally low, is greater if a cessation attempt occurs at lower levels of consumption. Other reports, however, provide evidence that even adolescent smokers in the early stages of smoking onset experience difficulty attempting cessation.23 Indeed, symptoms of nicotine dependence, which make cessation difficult, can develop soon after smoking initiation.5,24,25

Recent reviews advocate the intensification of efforts to develop and implement smoking cessation programs for adolescents.26,27 Correspondingly, initiatives have been established with the goal that every adolescent tobacco user have access to appropriate and effective cessation interventions by the year 2010.28 In addition, in the US, the goal of increasing cessation attempts among adolescent smokers has been incorporated into a set of nationwide public health goals.29 This has created a critical need to document the prevalence of cessation attempts among adolescent smokers. Therefore, the present study summarises the measures used to estimate attempts at smoking cessation and quantifies the prevalence, frequency and duration of cessation attempts among adolescent smokers, generally, and according to age and level of cigarette consumption.

Methods

Search and selection strategy

English language studies published between January 1990 and June 2005 were extracted from PubMed, ERIC, and PsychInfo databases using the following abstract keywords: (a) smoking, tobacco, cigarettes; (b) cessation, quit, stop; (c) child*, adolescen*, youth, school; and (d) representative, survey, national. Titles and abstracts were screened to determine if publications met the following inclusion criteria: (1) the study was based on a nationally representative sample; (2) the subjects ranged in age from ⩾10 to <20 years; (3) the study population was broadly representative of adolescents (hence, the exclusion of studies of special adolescent populations such as vocational students, the unemployed, the incarcerated, or those who were pregnant); and (4) the study reported the prevalence, frequency and/or duration of cessation attempts among adolescents who currently smoked cigarettes. Current smoking was defined either as having smoked at least once in the past 30 days or as self‐declared “current” smoking. Additional studies that met the inclusion criteria were identified by scanning references in the reports retained from the primary search, as well as from Internet searches of the websites of the following central data collection agencies: Health Canada, Statistics Canada, UK National Health Service, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, World Health Organization, and US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The following data were abstracted from each study retained: sampling unit (school, household or other); country in which the study had been conducted; sample size; year(s) of data collection; participants' age/grade range, smoking status, smoking frequency and lifetime cigarette consumption; the definition of cessation attempt; the time period over which the prevalence, frequency and/or duration of cessation attempts was estimated; categories used to enumerate the frequency and/or duration of cessation attempts; and estimates (with 95% confidence intervals) of the prevalence, frequency and/or duration of cessation attempts.

The frequency and the duration of cessation attempts were usually reported as categorical, rather than continuous variables. To enable synthesis and comparison across studies, the frequency of cessation attempts was converted to a measure of the prevalence of multiple (⩾2, ⩾3, and/or ⩾4) cessation attempts. Estimates of the duration of cessation attempts were converted to measures of the prevalence of relapse within 1 week, 1 month, 6 months, and 1 year following the longest cessation attempt.

Stratification variables

Estimates of the prevalence of any cessation attempt, of multiple cessation attempts and of relapse were grouped according to age/grade and level of cigarette consumption as indicated by current smoking status, smoking frequency and lifetime cigarette consumption.

Age/grade strata

The following assumptions were made regarding the relationship between age and grade: Grade 6 (age: 11–12), Grade 7 or post Primary or Junior Secondary School Year 1 (age: 12–13), Grade 8 or Junior Secondary School Year 2 or Form 1 (age: 13–14), Grade 9 or Secondary 1 or Junior Secondary School Year 3 or Form 2 (age: 14–15), Grade 10 or Secondary 2 or Form 3 (age: 15–16), Grade 11 or Secondary 3 or Form 4 (age: 16–17), and Grade 12 or High school seniors or Secondary 4 or Form 5 (age: 17–18). To facilitate cross‐study comparison, three “periods” of adolescence were established: early (ages ⩾10 to <13), middle (ages ⩾13 to <16) and late (ages ⩾16 to <20).

Cigarette consumption strata

When provided by the study, level of cigarette consumption was grouped according to: smoking status (self‐defined status as a “smoker”, use “within the past 30 days” or use “within the past week”), smoking frequency (daily, non‐daily or any use), and cumulative lifetime cigarette consumption (⩾100 cigarettes or <100 cigarettes).

Synthesis and comparative analysis

Because few studies were comparable by age, by level of cigarette consumption, or by operational definition of the prevalence, frequency and/or duration smoking cessation attempts, a non‐parametric measure of central tendency (the median) and the minimum and maximum estimates were calculated to allow cross‐study summaries to be made. Several studies reported multiple aggregate and/or stratum‐specific estimates that, in some cases, were not mutually exclusive. Such duplicate and/or overlapping estimates were excluded from the estimated summary medians. Patterns of the prevalence of any cessation attempt, of multiple cessation attempts and of relapse in relation to age, smoking frequency and/or lifetime cigarette consumption were reported from studies that provided internal comparisons (ie, determined within the same population sample) across these characteristics.

Results

Sources of nationally representative cessation attempt estimates among adolescent smokers

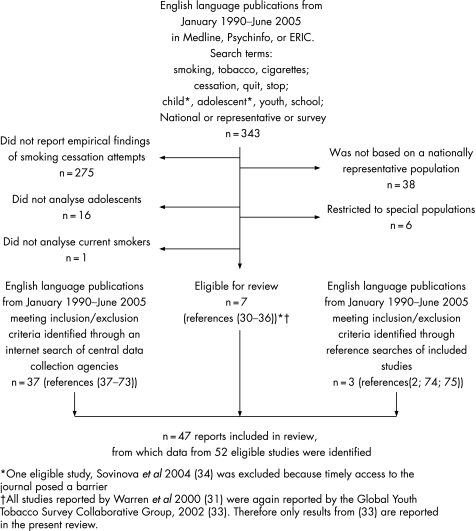

The search of PubMed, ERIC and PsychInfo databases yielded 343 unique publications, of which only 7 met the inclusion criteria (fig 1).30,31,32,33,34,35,36 The Internet search yielded an additional 37 publications, most of which were based on the Global Youth Tobacco Surveys, a joint project of the World Health Organization and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (fig 1).37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73 These surveys provided comparable and standardised country–level data with emphasis on the developing regions of the world.33 Three additional reports that met the inclusion criteria were obtained through a search of references that had appeared in the studies retained (fig 1).2,74,75 In total, the searches yielded 47 publications, which reported on the 52 nationally representative studies reviewed here (fig 1).

Figure 1 Selection of reports of nationally representative studies of the prevalence of cessation attempts among adolescent smokers.

Measurement of smoking cessation attempts among adolescent smokers

Table 1 presents the types of measure, the terminology and the reference timeframe used to define cessation attempts among the reviewed studies. Cessation was typically described using the term “quit” or “stop”. Although most studies considered cessation alone, one measured behaviours associated with smoking reduction (“tried to cut down on use of cigarettes”).2 In some studies, a more detailed description of what qualified as cessation was expressed through the use of such terms as “seriously” and “successfully”;35,70 in others, a minimum timeframe of abstinence of 24 h was specified.62,63,64,65,66,67

Table 1 Description of operational definitions of cessation attempt estimates in nationally representative studies* of adolescent smokers.

| Type of estimate | Reference timeframe | Language used to describe cessation attempt | Number of studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Point prevalence of any cessation attempt | In the past 6 months | “Tried to quit” | 3†30,37,70,74,75 |

| “Made at least one serious attempt to quit smoking cigarettes” | |||

| “Tried to quit smoking” | 44‡§||¶**2,31,33,35,36,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,71,72,73 | ||

| In the past 12 months | “Tried to stop smoking” | ||

| “Seriously tried to quit smoking” | |||

| “Tried to quit smoking at least once” | |||

| “Tried to quit smoking” | |||

| “Made at least one quit attempt of 24 h or more” | |||

| “Tried to cut down on use of cigarettes” | |||

| Lifetime†† | “Ever tried to quit” | 8†‡‡2,32,37,68,70,74,75 | |

| “Ever made at least one serious attempt to quit smoking cigarettes” | |||

| “Tried to stop smoking” | |||

| “Tried to quit smoking”“Ever tried to stop smoking and found you could not” | |||

| Point prevalence of multiple cessation attempts | In the past 12 months | “Number of quit attempts of at least 24 h duration” | 562,63,64,65,66,67 |

| Lifetime†† | “Number of quit attempts” | 337,68,74 | |

| “Number of times tried to quit” | |||

| “Tried to stop smoking” | |||

| Point prevalence of relapse within a specified duration following a cessation attempt | Lifetime†† | “Longest time successfully stopped smoking”“Longest time you ever quit smoking” | 337,70,74 |

| “Longest time you stayed off cigarettes” |

*We defined a study as a sample of individuals in a particular place during a particular time period.

†Multiple reports were based on the 1989 US Teenage Attitudes and Practices Study.30,74,75

‡One publication included estimates from nineteen nationally representative studies.33 Another publication included estimates from seven nationally representative studies.31

§Estimates for the same study population were provided by multiple reports as follows: Barbados (1999),31,33,71 Canada (2000)66,67 Costa Rica (1999),31,33,71,72 Dominica (2000),33,47,71 Fiji (1999),31,33 Grenada (2000),33,41,71 Jamaica (2001),33,48,71 Jordan (1999),31,33 Philippines (2000),33,38 South Africa (1999),31,33,39 Sri Lanka (1999),31,33 St. Vincent and the Grenadines (2001),33,71 and Suriname (2000),33,71,73 Trinidad and Tobago (2000),33,49,71 US (2000),33,36,71 Venezuela (1999).31,33,42,71 If estimates for the same population stratum differed between the multiple reports, only those provided by The Global Youth Tobacco Survey Collaborative Group33 were retained in subsequent tables.

||One US study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention35 measured cessation attempts in the same population through two different questions, thus providing two unique estimates.

¶Emmanuel69 reported an outlying estimate of the point prevalence of any cessation attempt in the past 12 months of 5.5% in a St. Lucia (2001) population. However, two subsequent reports33,71 indicate “data not available” for this country. Therefore, the outlying result was omitted and assumed an error.

**Perez‐Martin and Peruga71 reported results for Cuba (2001) and Haiti (2001). However, results for these countries were not included in the present review because a subsequent report33 indicated that the sampling frame for these two countries was subnational.

††We assumed a lifetime occurrence when a specific reference timeframe for measuring the cessation attempts was not described.

‡‡One publication reported the lifetime prevalence for three distinct US populations defined according to time, and therefore, was counted as three studies.2

The influence of differences in terminology on cessation attempt prevalence could not be determined because of variations in age, level of cigarette consumption, and other factors among the populations studied, as well as the small number of studies available for comparison. However, estimates of the lifetime prevalence of any cessation attempt that indicated explicitly that the attempt had failed by stating: “ever tried to stop smoking and found you could not” were substantially lower than in studies that lacked an explicit declaration of failure.2 In addition, one study reported both the point prevalence of having “seriously tried to quit smoking in the past 12 months” and of having “tried to quit at least once in the past 12 months” and found a slightly lower 12‐month point prevalence of having “seriously tried to quit smoking”.35

Study characteristics

Table 2 presents selected characteristics of the 52 studies retained. Study participants were drawn primarily from school‐based samples; only seven studies sampled households and two sampled both schools and households. Sample sizes were generally small, with only nine studies reporting samples of 1000 or more adolescent smokers (table 2). Most studies did not report 95% confidence intervals or standard errors, and the precision of estimates could not be ascertained because of missing information on the number of smokers included in the study.

Table 2 Selected characteristics of nationally representative studies* of cessation attempts among adolescent smokers according to type of cessation attempt estimate.

| Characteristic | Number of estimates | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any cessation attempt | Multiple cessation attempts | |||||

| 6‐month prevalence | 12‐month prevalence† | Lifetime prevalence | 12‐month prevalence‡ | Lifetime prevalence | Duration of cessation attempt | |

| Geographic location | ||||||

| North America | 330,37,70,74,75 | 102,33,35,36,50,51,62,63,64,65,66,67 | 62,37,70,74,75 | 562,63,64,65,66 | 27,74 | 337,70,74 |

| Central America and the Caribbean | 0 | 933,41,47,48,49,71,72,73 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| South America | 0 | 233,42 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Europe | 0 | 444,45,46,53 | 132 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Africa | 0 | 739,40,52,57,58,59,60 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Middle East | 0 | 533,54,55,56 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Asia | 0 | 533,38,43,61 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Oceania | 0 | 233 | 168 | 0 | 168 | 0 |

| Year of data collection | ||||||

| Prior to 1980 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1980–1989 | 130,74,75 | 0 | 32,74,75 | 0 | 174 | 174 |

| 1990–1999 | 137 | 102,33,35,39,42,63,72 | 232,37 | 163 | 137 | 137 |

| 2000–2005 | 170 | 3433,36,38,40,41,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,64,65,66,67,71,73 | 268,70 | 462,64,65,66 | 168 | 170 |

| Sampling frame | ||||||

| Schools | 0 | 3833,35,36,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,71,72,73 | 52,32,68 | 0 | 168 | 0 |

| Households | 130,74,75 | 62,62,63,64,65,66,67 | 174,75 | 562,63,64,65,66 | 174 | 174 |

| Other§ | 237,70 | 0 | 237,70 | 0 | 137 | 237,70 |

| Sample size|| | ||||||

| Not stated | 0 | 22,63 | 0 | 163 | 0 | 0 |

| <500 | 170 | 2333,40,41,42,47,48,49,52,54,55,56,57,59,60,61,71,73 | 268,70 | 0 | 168 | 170 |

| 500–<1000 | 0 | 833,46,62,64,65,66,67,72 | 0 | 462,64,65,66 | 0 | 0 |

| ⩾1000 | 230,37,74,75 | 1135,36,38,39,43,44,45,50,51,53,58 | 62,32,37,74,75 | 0 | 237,74 | 237,74 |

*We defined a study as a sample of individuals in a particular place during a particular time period.

†Although in some instances these were available from other reports,31,71 study characteristics were abstracted from The Global Youth Tobacco Survey Collaborative Group33 for the following study populations: Barbados (1999), Fiji (1999), Gaza Strip (2001), Jordan (1999), Montserrat (2000), Northern Mariana Islands (2000), Singapore (2000), Sri Lanka (1999), and St. Vincent and the Grenadines (2001). Study characteristics for Bahamas (2000) were abstracted from Perez Martin and Peruga (2002).71

‡Study characteristics for Canada (2000) were abstracted from Health Canada.66

§Other includes studies with a sampling frame that included both schools and households.37,70

||Reflects the sample size of current smokers. The sample size for age and smoking history specific subgroups as well as for the duration of cessation attempts was usually smaller. If the sample size of current smokers was not provided, wherever possible, it was estimated from (a) the total study sample size multiplied by the proportion of current smokers or (b) the large‐sample 95% confidence interval for a population proportion (p±1.96*SEp) where p = prevalence and SEp = standard error of p.

Characteristics of cessation attempt estimates

Table 3 summarises cessation attempt estimates according to age/grade and level of cigarette consumption from the 52 studies retained. Estimates were typically measured in population samples that were heterogeneous with respect to age, ie, that included more than one period of adolescence (most often early to late or middle to late adolescence). Studies that reported findings for narrower age groups usually focused on middle or late adolescence, with only five studies reporting estimates specific to early adolescent smokers.38,39,40,41,42 Within‐study examination, by age, of patterns in the prevalence of any cessation attempt, of multiple cessation attempts or of relapse was possible in 19 studies that provided age‐stratified estimates for at least one of these measures (table 3).35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,47,49,50,51,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,74,75

Table 3 Number of national population‐based estimates* according to period of adolescence, level of cigarette consumption and type of cessation attempt estimate.

| Characteristic | Number of estimates | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any cessation attempt | Multiple† cessation attempts | |||||

| 6‐month prevalence§ | 12‐month prevalence|| | Lifetime prevalence§ | 12‐Month prevalence | Lifetime prevalence | Duration of cessation attempt‡ | |

| Period of adolescence | ||||||

| Early | – | 738,39,40,41,42 | – | – | – | – |

| Early to middle | 737,70,75 | 1435,36,42,43,44,45,46,53,54,55,57,59,60 | 937,68,70,75 | – | 337,68,74 | 537,70,74 |

| Middle | 175 | 4433,38,39,40,41,42,47,48,49,50,51,56,71 | 175 | – | 174 | 174 |

| Early to late | 730,37,75 | 122,38,40,41,47,48,49,52,61,72,73 | 537,75 | – | 237,74 | 437,74 |

| Middle to late | 537 | 1435,36,50,51,58,62,63,64,65,66,67 | 732,37,68 | 862,63,64,65,66,67 | 237,68 | 337 |

| Late | 175 | 1538,39,40,41,49,50,51,62,63,64,65,66,67 | 72,75 | 562,63,64,65,66 | 174 | 174 |

| Smoking status | ||||||

| Self‐defined current | – | 1362,63,64,65,66,67 | 132 | 1362,63,64,65,66,67 | – | – |

| Past week | 170 | – | 170 | – | – | 170 |

| Past month | 2030,37,75 | 932,33,35,36,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,71 | 272,37,68,75 | – | 937,68,74 | 1337,74 |

| Smoking frequency | ||||||

| Any use | 1337,75 | 932,33,35,36,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61 | 182,37,68,75 | – | 937,68,74 | 737,74 |

| Daily¶ | 530,37,70 | 1362,63,64,65,66,67 | 82,32,37,70 | 1362,63,64,65,66,67 | – | 437,70 |

| Non‐daily | 337 | – | 337 | – | – | 337 |

| Cumulative lifetime consumption | ||||||

| ⩾100 cigarettes | 1430,37,75 | 12 | 937 | – | 337 | 937 |

| <100 cigarettes | 337 | 12 | 337 | – | – | – |

| Any consumption/not stated | 437,70 | 10433,35,36,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,71 | 172,32,37,68,70,75 | 1362,63,64,65,66,67 | 668,74 | 570,74 |

*The estimate, not the study, is the unit of analysis for this table. A single study could report multiple age‐ and smoking history‐specific estimates.

†Studies differed in how multiple cessation attempts were categorised. Categories of ⩾2, ⩾3, and/or ⩾4 cessation attempts could be derived, although not across all studies. If more than one of these cessation attempt frequency categories could be derived for a given smoking characteristic and period of adolescence stratum, then, collectively, they were considered as a single estimate of the prevalence of multiple cessation attempts for that stratum (table 4).

‡Studies differed in how the length of abstinence was categorised. Durations of ⩽1 week, ⩽1 month, ⩽6 months and/or ⩽1 year could be derived, although not across all studies. If more than one of these duration categories could be derived for a given level of cigarette consumption and period of adolescence stratum, then, collectively, they were considered as a single estimate of the duration of the cessation attempt for that stratum (table 5).

§Three reports30,74,75 were based on the 1989 US Teenage Attitudes and Practices Survey. When estimates for duplicate age and/or smoking history strata were available, only Moss et al75 was considered in the calculation of summary estimates.

||Three reports provided duplicate estimates from several of the same populations.31,33,71 When estimates for duplicate age and or smoking history strata were available, they were abstracted from The Global Youth Tobaccos Survey Collaborative Group.33

¶Several studies provided a more detailed breakdown of consumption within the “daily” smoking category.30,37 In such instances only one aggregate age‐specific estimate among daily smokers was counted in tabulating the number of estimates.

Most cessation attempt estimates were derived from studies that defined current smoking heterogeneously as having smoked one or more cigarettes in the past 30 days (table 3). Only one study reported estimates stratified according to smoking frequency,37 while two reported estimates stratified according to cumulative lifetime consumption.2,37 These same studies reported the only cessation attempt estimates specific to non‐daily smokers or to adolescents who had consumed <100 cigarettes in their lifetime. Several additional studies, however, reported estimates specific to daily smokers30,32,62,63,64,65,66,67,70 and/or to consumers of ⩾100 cigarettes.30,74,75

Estimates of the prevalence of smoking cessation attempts

A majority of estimates indicated that at least half of adolescent current smokers had attempted cessation in the past 6 months (median: 58%, range: 22–73%) (table 6), and that more than two‐thirds had attempted cessation in the past 12 months (median: 68%, range 43–92%) (table 7), or in their lifetime (median: 71%, range 28–84%) (table 8). Moreover, a majority of estimates indicated that more than half of adolescent current smokers had made multiple lifetime cessation attempts (median⩾2 attempts: 60%, range 36–69%; median⩾3 attempts: 36%, range 27–49%; median⩾4 attempts: 22%, range 20–25%) (table 4).

Table 6 Estimated 6‐month prevalence of cessation attempts among adolescent smokers according to level of cigarette consumption* and period of adolescence.

| Country, study year | Age/grade range | Definition of cessation in the past 6 months | Prevalence (%) (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any use (in the past month) | |||

| Early to middle adolescence | |||

| Canada, 199437 | Age 10–14 | Tried to quit | 41† |

| 65‡ | |||

| 22§ | |||

| United States, 198975 | Age 12–13 | Made at least one serious attempt to quit smoking cigarettes | 73 (67 to 78)‡|| |

| Middle adolescence | |||

| United States, 198975 | Age 14–15 | Made at least one serious attempt to quit smoking cigarettes | 68 (66 to 72)‡|| |

| Early to late adolescence | |||

| Canada, 199437 | Age 10–19 | Tried to quit | 44† |

| 48‡† | |||

| 33§† | |||

| United States, 198975 | Age 12–18 | Made at least one serious attempt to quit smoking cigarettes | 57 (56 to 59)‡†|| |

| Middle to late adolescence | |||

| Canada, 199437 | Age 15–19 | Tried to quit | 45† |

| 44‡ | |||

| 52§ | |||

| Late adolescence | |||

| United States, 198975 | Age 16–18 | Made at least one serious attempt to quit smoking cigarettes | 52 (50 to 54)‡|| |

| Daily use (in the past week) | |||

| Early to middle adolescence | |||

| Canada, 200270 | Grade 5–9 | Tried to quit | 57 |

| Daily use (in the past month) | |||

| Early to middle adolescence | |||

| Canada, 199437 | Age 10–14 | Tried to quit | 64‡¶** |

| Early to late adolescence | |||

| Canada, 199437 | Age 10–19 | Tried to quit | 41‡†¶** |

| United States, 198930 | Age 12–19 | Tried to quit | 52 (<10 cigarettes per day)‡ |

| 49 (⩾10 cigarettes per day)‡ | |||

| Middle to late adolescence | |||

| Canada, 199437 | Age 15–19 | Tried to quit | 38‡¶** |

| Non‐daily use (in the past month) | |||

| Early to middle adolescence | |||

| Canada, 199437 | Age 10–14 | Tried to quit | 65‡¶ |

| Early to late adolescence | |||

| Canada, 199437 | Age 10–19 | Tried to quit | 62‡†¶ |

| Middle to late adolescence | |||

| Canada, 199437 | Age 15–19 | Tried to quit | 60‡¶ |

*Any use in the past month was defined operationally as “smoked ⩾1 cigarette in the past 30 days”; daily use in the past week was defined operationally as: “smoked cigarettes on each of the 7 days preceding data collection”; daily use in the past month was defined operationally as: “smoked⩾1 cigarette each day in the past 30 days”; non‐daily use in the past month was defined operationally as: “smoked ⩾1 cigarette in the past 30 days, but not daily”.

†Excluded from the calculation of summary estimate because complete stratum‐specific estimates were available for this study.

‡Estimated among the subgroup of adolescents who had smoked ⩾100 cigarettes in their lifetime.

§Estimated among the subgroup of adolescents who had smoked <100 cigarettes in their lifetime.

||Three reports30,74,75 were based on the 1989 US Teenage Attitudes and Practices Survey. When estimates for duplicate age and/or smoking history strata were available, only Moss et al75 was considered in the calculation of summary estimates. Estimates of the 6‐month prevalence of cessation attempts among adolescents reporting any use in the past month for duplicate age strata were as follows: 65 and 55 among 12–18 year olds as reported by Allen et al74 and Zhu et al,30 respectively; 80 among 12–13 year olds as reported by Allen et al;74 75 among 14–15 year olds as reported by Allen et al;74 and 60 among 16–18 year olds as reported by Allen et al.74

¶Estimate was derived by multiplying the proportion who ever tried to quit by the proportion of ever quitters who tried to quit in the past 6 months.

**Additional data were reported on the 6‐month cessation attempt prevalence according to the frequency of daily consumption among adolescents who had consumed ⩾100 cigarettes in their lifetime and who had ever tried to quit smoking, as follows: age 10–14: 83 (1–5 cigarettes per day), 73 (6–10 cigarettes per day), 68 (11–15 cigarettes per day), 77 (16–20 cigarettes per day), 84 (⩾25 cigarettes per day); age 15–19: 70 (1–5 cigarettes per day, 60 (6–10 cigarettes per day), 49 (11–15 cigarettes per day), 33 (16–20 cigarettes per day), 46 (21–25 cigarettes per day); age 10–19: 75 (1–5 cigarettes per day), 63 (6–10 cigarettes per day), 52 (11–15 cigarettes per day), 40 (16–20 cigarettes per day), 50 (21–25 cigarettes per day), 68 (⩾25 cigarettes per day).

Table 7 Estimated 12‐month prevalence of cessation attempts among adolescent smokers according to level of cigarette consumption* and period of adolescence.

| Country, study year | Age/grade range | Definition of cessation in the past 12 months | Prevalence (%) (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any use (in the past month) | |||

| Early adolescence | |||

| Grenada, 200041 | Grade 6 | Tried to stop smoking | 62 (30 to 94) |

| Grade 7 | 74 (56 to 92) | ||

| Philippines, 200038 | Age ⩽12† | Tried to stop smoking | 81 (74 to 88) |

| South Africa, 199939 | Age ⩽12† | Tried to stop smoking | 76 (59 to 92) |

| Seychelles, 200240 | Age 11–12 | Tried to stop smoking | 78 |

| Venezuela, 199942 | Grade 6 | Tried to stop smoking | 90 |

| Grade 7 | 59 | ||

| Early to middle adolescence | |||

| United States, 199935 | Grade 6–8 | Seriously tried to quit smoking | 58 (54 to 62) |

| United States, 199935 | Grade 6–8 | Tried to quit smoking at least once | 61 (59 to 63) |

| United States, 200036 | Grade 6–8 | Tried to quit smoking cigarettes | 60 (57 to 63) |

| Venezuela, 199942 | Grade 6–9 | Tried to stop smoking | 69‡ |

| Georgia, 200243 | Grade 7–9 | Tried to stop | 49 (42 to 56) |

| Serbia, 200346 | Grade 7–9 | Tried to stop smoking | 78 (73 to 83) |

| Slovakia, 200345 | Grade 7–9 | Tried to stop smoking | 81 (78 to 84) |

| Slovenia, 2002/200344 | Grade 7–9 | Tried to stop smoking | 68 (66 to 71) |

| Bahrain, 200354 | Grade 7–10 | Tried to stop smoking | 63 (55 to 71) |

| Egypt, 200159 | Grade 7–10 | Tried to stop smoking | 64 (50 to 77) |

| Ghana, 200057 | Junior secondary school years 1–3 | Tried to stop smoking | 78 |

| Hungary, 200353 | Grade 7–10 | Tried to stop smoking | 64 (60 to 68) |

| Kenya, 200160 | Grade 7–Form 2 | Tried to stop smoking | 70 (63 to 78) |

| United Arab Emirates, 200255 | Grade 7–10 | Tried to stop smoking | 64 (58 to 71) |

| Middle adolescence | |||

| Grenada, 200033,41 | Age 13–15 | Tried to stop smoking | 75‡ (67 to 83) |

| Grade 8 | 79 (56 to 100) | ||

| Form 1 | 80 (63 to 96) | ||

| Form 2 | 66 (57 to 76) | ||

| Philippines, 200033,38 | Age 13–15 | Tried to stop smoking | 83‡ (79 to 87) |

| Age 13 | 90 (81 to 99) | ||

| Age 14 | 85 (80 to 91) | ||

| Age 15 | 81 (74 to 87) | ||

| Seychelles, 200240 | Age 13 | Tried to stop smoking | 78 |

| Age 14 | 84 | ||

| Age 15 | 73 | ||

| Venezuela, 199931,33,42 | Age 13–15 | Tried to stop smoking | 68‡ (58 to 79) |

| Grade 8 | 74 | ||

| Grade 9 | 66 | ||

| Dominica, 200033,47 | Age 13–15 | Tried to stop smoking | 56¶ (43 to 69) |

| Form 2 | 47¶ (26 to 68) | ||

| Jamaica, 200133,48 | Age 13–15 | Tried to stop smoking | 71¶ (62 to 80) |

| Grade 9 | 66¶ (52 to 80) | ||

| Trinidad and Tobago, 200033,49 | Age 13–15 | Tried to stop smoking | 76¶ (68 to 84) |

| Age 14 | 65¶ | ||

| Age 15 | 87¶ | ||

| United States, 200150 | Grade 9 | Tried to quit smoking | 56 (52 to 60) |

| Grade 10 | 55 (51 to 59) | ||

| United States, 200351 | Grade 9 | Tried to quit smoking | 52 (46 to 58) |

| Grade 10 | 59 (53 to 65) | ||

| Bahamas, 200071 | Age 13–15 | Tried to stop smoking | 77 |

| Barbados, 199931,33 | Age 13–15 | Tried to stop smoking | 64 (57 to 70) |

| Costa Rica, 199931,33 | Age 13–15 | Tried to stop smoking | 63 (58 to 68) |

| Fiji, 199931,33 | Age 13–15 | Tried to stop smoking | 79 (67 to 91) |

| Gaza Strip, 200133 | Age 13–15 | Tried to stop smoking | 62 (46 to 78) |

| Jordan, 199931,33 | Age 13–15 | Tried to stop smoking | 78 (73 to 84) |

| Montserrat, 200033 | Age 13–15 | Tried to stop smoking | 60 (48 to 72) |

| Northern Mariana Islands, 200033 | Age 13–15 | Tried to stop smoking | 77 (72 to 82) |

| St. Vincent and the Grenadines, 200133 | Age 13–15 | Tried to stop smoking | 83 (72 to 94) |

| Singapore, 200033 | Age 13–15 | Tried to stop smoking | 78 (75 to 81) |

| South Africa, 199931,33,39 | Grade 8–10 | Tried to stop smoking | 77‡ (72 to 81) |

| Age 13–15 | 75‡ (69 to 80) | ||

| Age 13 | 69 (50 to 88) | ||

| Age 14 | 71 (61 to 81) | ||

| Age 15 | 78 (69 to 87) | ||

| Sri Lanka, 199931,33 | Age 13–15 | Tried to stop smoking | 43 (28 to 58) |

| Sultanate of Oman, 200356 | Grade 8–10 | Tried to stop smoking | 67 (57 to 78) |

| Suriname, 200033 | Age 13–15 | Tried to stop smoking | 73 (62 to 83) |

| United States, 200033 | Age 13–15 | Tried to quit smoking | 58‡ (56 to 60) |

| Early to late adolescence | |||

| Botswana, 200252 | Age 11–17 | Tried to stop | 68 |

| Costa Rica, 199972 | Age 11–17 | Tried to stop smoking | 71 |

| Dominica, 200047 | Age 11–17 | Tried to stop smoking | 52 (42 to 62) |

| Grenada, 200041 | Grade 6–Form 4 | Tried to stop smoking | 70‡ (62 to 78) |

| Jamaica, 200148 | Grade 7–13 | Tried to stop smoking | 68 (61 to 75) |

| Macao, 200161 | Grade 6–Form 3 | Tried to stop smoking | 64 (56 to 72) |

| Philippines, 200038 | Age ⩽12–⩾16† | Tried to stop smoking | 84 (81 to 87) |

| Seychelles, 200240 | Age 11–17 | Tried to stop smoking | 77‡ |

| Suriname, 200073 | Age 12–16 | Tried to stop smoking | 68 |

| Trinidad and Tobago, 200049 | Post Primary–Form 5 | Tried to stop smoking | 77 |

| United States, 19912 | Age 12–18 | Tried to cut down on use of cigarettes | 73§ |

| 45|| | |||

| Middle to late adolescence | |||

| South Africa, 200258 | Grade 8–11 | Tried to stop smoking | 74 (71 to 77) |

| United States, 199935 | Grade 9–12 | Seriously tried to quit smoking | 56 (53 to 58) |

| United States, 199935 | Grade 9–12 | Tried to quit smoking at least once | 62 (60 to 63) |

| United States, 200036 | Grade 9–12 | Tried to quit smoking cigarettes | 59 (57 to 61) |

| United States, 200150 | Grade 9–12 | Tried to quit smoking | 57 (56 to 59) |

| United States, 200351 | Grade 9–12 | Tried to quit smoking | 54 (51 to 57) |

| Late adolescence | |||

| Philippines, 200038 | Age ⩾16† | Tried to stop smoking | 86 (82 to 89) |

| Seychelles, 200240 | Age 16–17 | Tried to stop smoking | 78 |

| South Africa, 199939 | Age ⩾16† | Tried to stop smoking | 78 (73 to 82) |

| Trinidad and Tobago, 200049 | Age ⩾16† | Tried to stop smoking | 85¶ |

| Grenada, 200041 | Form 3 | Tried to stop smoking | 56 (35 to 78) |

| Form 4 | 78 (59 to 97) | ||

| United States, 200150 | Grade 11 | Tried to quit smoking | 60 (58 to 63) |

| Grade 12 | 58 (54 to 62) | ||

| United States, 200351 | Grade 11 | Tried to quit smoking | 51 (47 to 56) |

| Grade 12 | 53 (48 to 58) | ||

| Daily use (self‐declared current) | |||

| Middle to late adolescence | |||

| Canada, 200066,67 | Age 15–19 | Made at least one ⩾24 h quit attempt | 70‡ |

| Age 15–17 | 67 | ||

| Canada, 200165 | Age 15–19 | Made at least one ⩾24 h quit attempt | 66‡ |

| Age 15–17 | 68 | ||

| Canada, 200264 | Age 15–19 | Made at least one ⩾24 h quit attempt | 64‡ |

| Age 15–17 | 67 | ||

| Canada, 199963 | Age 15–17 | Made at least one ⩾24 h quit attempt | 79 |

| Canada, 200362 | Age 15–17 | Made at least one ⩾24 h quit attempt | 92 |

| Late adolescence | |||

| Canada, 199963 | Age 18–19 | Made at least one ⩾24 h quit attempt | 73 |

| Canada, 200066,67 | Age 18–19 | Made at least one ⩾24 h quit attempt | 61 |

| Canada, 200165 | Age 18–19 | Made at least one ⩾24 h quit attempt | 63 |

| Canada, 200264 | Age 18–19 | Made at least one ⩾24 h quit attempt | 61 |

| Canada, 200362 | Age 18–19 | Made at least one ⩾24 h quit attempt | 84 |

*Any use in the past month was defined operationally as “smoked ⩾1 cigarette in the past 30 days”, except by the US Department of Health2 where it was defined as “smoked in past month”; daily use (self‐declared current) was defined operationally as: “smoke cigarettes daily at the present time”.

†The Global Youth Tobacco Surveys identified classes to correspond to the target group of adolescents aged 13–15. However, all students in the selected classes were eligible to participate. Therefore adolescents younger than 13 years and older than 15 years could be included. For the age categories ⩽12 years and ⩾16 years we assumed that the lower and upper bounds met the eligibility criteria that study subjects be adolescents aged 10–19.

‡Excluded from the calculation of summary estimate because complete stratum‐specific estimates were available for this study.

§Estimated among the subgroup of adolescents who had smoked ⩾100 cigarettes in their lifetime.

||Estimated among the subgroup of adolescents who had smoked <100 cigarettes in their lifetime.

¶Excluded from summary estimates because a more inclusive aggregate estimate is available for this study.

Table 8 Estimated lifetime prevalence of cessation attempts among adolescent smokers according to level of cigarette consumption* and period of adolescence.

| Country, study year | Age/grade range | Definition of cessation | Prevalence (%) (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any use (in the past month) | |||

| Early to middle adolescence | |||

| Canada, 199437 | Age 10–14 | Ever tried to quit | 57† |

| 84†‡ | |||

| 35§ | |||

| United States, 198975 | Age 12–13 | Ever made at least one serious attempt to quit smoking cigarettes | 82 (77 to 87)|| |

| Republic of Palau, 200168 | Grade 6–8 | Tried to stop smoking | 69 |

| Middle adolescence | |||

| United States, 198975 | Age 14–15 | Ever made at least one serious attempt to quit smoking cigarettes | 77 (75 to 80)|| |

| Early to late adolescence | |||

| Canada, 199437 | Age 10–19 | Ever tried to quit | 72† |

| 82‡† | |||

| 47§† | |||

| United States, 198975 | Age 12–18 | Ever made at least one serious attempt to quit smoking cigarettes | 74 (73 to 76)†|| |

| Middle to late adolescence | |||

| Canada, 199437 | Age 15–19 | Ever tried to quit | 79† |

| 81‡† | |||

| 68§ | |||

| Republic of Palau, 200168 | Grade 9–12 | Tried to stop smoking | 50 |

| Late adolescence | |||

| United States, 1976–19792 | High school seniors | Ever tried to stop smoking and found you could not | 32 |

| United States, 1980–19842 | High school seniors | Ever tried to stop smoking and found you could not | 31 |

| United States, 1985–19892 | High school seniors | Ever tried to stop smoking and found you could not | 28 |

| United States, 198975 | Age 16–18 | Ever made at least one serious attempt to quit smoking cigarettes | 73 (71 to 74)|| |

| Daily use (self‐declared current) | |||

| Middle to late adolescence | |||

| Denmark, 1996–199732 | Age 15–20 | Ever tried to quit smoking | 64¶ |

| Daily use (in the past week) | |||

| Early to middle adolescence | |||

| Canada, 200270 | Grade 5–9 | Ever tried to quit | 77 |

| Daily use (in the past month) | |||

| Early to middle adolescence | |||

| Canada, 199437 | Age 10–14 | Ever tried to quit | 84‡ |

| Early to late adolescence | |||

| Canada, 199437 | Age 10–19 | Ever tried to quit | 81‡† |

| Middle to late adolescence | |||

| Canada, 199437 | Age 15–19 | Ever tried to quit | 80‡ |

| Late adolescence | |||

| United States, 1976–19792 | High school seniors | Ever tried to stop smoking and found you could not | 39** |

| United States, 1980–19842 | High school seniors | Ever tried to stop smoking and found you could not | 42** |

| United States, 1985–19892 | High school seniors | Ever tried to stop smoking and found you could not | 39** |

| Non‐daily use (in the past month) | |||

| Early to middle adolescence | |||

| Canada, 199437 | Age 10–14 | Ever tried to quit | 84‡ |

| Early to late adolescence | |||

| Canada, 199437 | Age 10–19 | Ever tried to quit | 84‡† |

| Middle to late adolescence | |||

| Canada, 199437 | Age 15–19 | Ever tried to quit | 83‡ |

*Any use in the past month was defined operationally as “smoked ⩾1 cigarette in the past 30 days”, except by the US Department of Health2 where it was defined as “smoked at all in the past 30 days ”; daily use (self‐declared current) was defined operationally as: “smoke every day”; daily use in the past week was defined operationally as: “smoked cigarettes on each of the 7 days preceding data collection”; daily use in the past month was defined operationally as: “smoked⩾1 cigarette each day in the past 30 days”; non‐daily use in the past month was defined operationally as: “smoked ⩾1 cigarette in the past 30 days, but not daily”.

†Excluded from the calculation of summary estimate because complete stratum‐specific estimates were available for this study.

‡Estimated among the subgroup of adolescents who had smoked ⩾100 cigarettes in their lifetime.

§Estimated among the subgroup of adolescents who had smoked <100 cigarettes in their lifetime.

||Two reports74,75 were based on the 1989 US Teenage Attitudes and Practices Survey. When estimates for duplicate age and/or smoking history strata were available, only Moss et al75 was considered in the calculation of summary estimates. Estimates of the lifetime prevalence of cessation attempts among adolescents reporting any use in the past month for duplicate age strata as reported by Allen et al74 were as follows: 86 among 12–18 year olds; 92 among 12–13 year olds; 87 among 14–15 year olds; 85 among 16–18 year olds.

¶This estimate excluded students who reported physician‐diagnosed asthma.

**Excluded from the calculation of summary estimates because a more inclusive aggregate estimate is available for this study.

Table 4 Estimated 12‐month and lifetime prevalence of multiple cessation attempts among adolescent smokers according to level of cigarette consumption* and period of adolescence.

| Country, study year† | Age/grade range | Definition of cessation | Prevalence (%) of cessation attempts by cumulative frequency‡ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ⩾2 | ⩾3 | ⩾4 | |||

| 12‐month cessation attempts | |||||

| Daily use (self‐declared current) | |||||

| Middle to late adolescence | |||||

| Canada, 199963,67 | Age 15–17 | Number of quit attempts of at least 24 h duration | 28 | ||

| Age 15–19 | 23|| | ||||

| Canada, 200165 | Age 15–17 | Number of quit attempts of at least 24 h duration | 22 | ||

| Age 15–19 | 23|| | ||||

| Canada, 200264 | Age 15–17 | Number of quit attempts of at least 24 h duration | 20 | ||

| Age 15–19 | 19|| | ||||

| Canada, 200066 | Age 15–17 | Number of quit attempts of at least 24 h duration | 23 | ||

| Canada, 200362 | Age 15–17 | Number of quit attempts of at least 24 h duration | 28 | ||

| Late adolescence | |||||

| Canada, 199963 | Age 18–19 | Number of quit attempts of at least 24 h duration | 20 | ||

| Canada, 200066 | Age 18–19 | Number of quit attempts of at least 24 h duration | 19 | ||

| Canada, 200165 | Age 18–19 | Number of quit attempts of at least 24 h duration | 25 | ||

| Canada, 200264 | Age 18–19 | Number of quit attempts of at least 24 h duration | 18 | ||

| Canada, 200362 | Age 18–19 | Number of quit attempts of at least 24 h duration | 24 | ||

| Lifetime cessation attempts | |||||

| Any use (in the past month) | |||||

| Early to middle adolescence | |||||

| Canada, 199437 | Age 10–14 | Number of quit attempts | 69§ | 49§ | |

| Republic of Palau, 200168 | Grade 6–8 | Tried to stop smoking | 36 | 27 | |

| United States, 1989–199074 | Age 12–13 | Number of times tried to quit | 62 | 25 | |

| Middle adolescence | |||||

| United States, 1989–199074 | Age 14–15 | Number of times tried to quit | 53 | 20 | |

| Early to late adolescence | |||||

| Canada, 199437 | Age 10–19 | Number of quit attempts | 63§|| | 40§|| | |

| United States, 1989–199074 | Age 12–18 | Number of times tried to quit | 59|| | 22|| | |

| Middle to late adolescence | |||||

| Canada, 199437 | Age 15–19 | Number of quit attempts | 60§ | 37§ | |

| Republic of Palau, 200168 | Grade 9–12 | Tried to stop smoking | 49 | 35 | |

| Late adolescence | |||||

| United States, 1989–199074 | Age 16–18 | Number of times tried to quit | 60 | 22 | |

*Any use in the past month was defined operationally as “smoked ⩾1 cigarette in the past 30 days”, except in Allen et al74 where it was defined as “smoked in the past 30 days” and in Hansen et al68 where it was defined as: “smoked cigarettes ⩾1 day in the past 30 days”; daily use (self‐declared current) was defined operationally as: “daily smoker”.

†One additional report70 provided mean (3.7), median (3.0) and range (1–20) of cessation attempts. However, these estimates were confined to smokers who had attempted cessation at least once, thus an estimate among all smoking adolescents could not be derived.

‡Findings for multiple cessation attempts were usually reported on an ordinal rather than on a continuous scale. The cumulative frequency categories reported here were derived by combining multiple ordinal categories. Summary estimates could only be calculated where the responses were scaled similarly across multiple studies.

§Estimated among the subgroup of adolescents who had smoked ⩾100 cigarettes in their lifetime.

||Excluded from the calculation of summary estimate because complete stratum‐specific estimates were available for this study.

The 6‐month, 12‐month and lifetime cessation attempt prevalence was higher among consumers of ⩾100 cigarettes than among consumers of <100 cigarettes (lifetime prevalence: 47% <100 cigarettes, 82% ⩾100 cigarettes;37 12‐month prevalence: 45% <100 cigarettes, 73% ⩾100 cigarettes;2 6‐month prevalence: 33% <100 cigarettes, 48% ⩾100 cigarettes)37 (tables 6–8). These differences by cumulative lifetime consumption were greatest among younger (age 10–14) adolescent smokers.37 Smokers (age 10–14) who had consumed <100 cigarettes in their lifetime had the lowest 6‐month and lifetime cessation attempt prevalence, whereas those who had consumed ⩾100 cigarettes had the highest 6‐month prevalence and among the highest lifetime cessation attempt prevalence.37

The 6‐month, but not the lifetime, cessation attempt prevalence was lower among more frequent smokers. Two reports found that daily smokers had a lower 6‐month prevalence than those reporting any use or non‐daily use (52% (daily <10 cigarettes per day) and 49% (daily ⩾10 cigarettes per day) vs 55% (any use))30 and (41% (daily) vs 48% (any use) vs 62% (non‐daily))37 (table 6). Lifetime cessation attempt prevalence was similar among current daily and non‐daily smokers (81% daily vs 84% non‐daily).37 This similarity in lifetime prevalence persisted over a broad age range. Differences in 6‐month prevalence were evident primarily between daily and non‐daily older (age 15–19) adolescent smokers; 6‐month prevalence did not differ markedly by daily versus non‐daily use among younger (age 10–14) smokers.37

The 6‐month, 12‐month and lifetime prevalence both of any and of multiple cessation attempts, was typically higher among younger than among older adolescents. The higher 6‐month cessation attempt prevalence among younger adolescents held for any use,37,74,75 daily smokers who had consumed ⩾100 cigarettes,37 and, although less pronounced, for non‐daily smokers who had consumed ⩾100 cigarettes.37 By contrast, among smokers of <100 cigarettes 6‐month cessation attempt prevalence was higher among older adolescents.37 Patterns of 12‐month cessation attempt prevalence across age strata were less consistent, particularly within the period of middle adolescence. Although a majority of studies found that late adolescent smokers had a lower 12‐month cessation attempt prevalence than middle or middle to late adolescent smokers41,49,51,62,63,64,65,66,67 other studies found either the reverse39,50,65 or showed no linear pattern with age.38,40,42 Finally, the age‐specific lifetime cessation attempt prevalence was typically higher among younger adolescent smokers.37,47,68,74,75 However, in one study the higher lifetime cessation attempt prevalence among younger smokers depended on cumulative lifetime consumption. Lifetime prevalence of any cessation attempt did not vary by age among smokers (daily or non‐daily) who had consumed ⩾100 cigarettes; prevalence of multiple cessation attempts, however, was higher in younger than in older adolescent smokers who had consumed ⩾100 cigarettes.37 By contrast, among consumers of <100 cigarettes, lifetime prevalence was markedly lower in younger (age 10–14) than in older (age 15–19) subjects.37

Estimates of the prevalence of relapse following the longest previous cessation attempt

Three studies estimated the prevalence of relapse within 1 week, 1 month, 6 months and/or 1 year following adolescent smokers' longest previous cessation attempt (table 5).37,70,74 The median prevalence of relapse within 1 week, 1 month, 6 months and 1 year following the longest attempt was: 34% (range: 14–73%), 56% (range: 44–83%), 89% (range: 88–91%) and 92% (range: 88–95%), respectively (table 5).

Table 5 Estimated prevalence of relapse within 1 week, 1 month, 6 months, and 1 year following the longest cessation attempt according to level of cigarette consumption* and period of adolescence among adolescent smokers who ever attempted cessation.

| Country, study year | Age/grade range | Definition of duration of abstinence | Prevalence (%) of relapse within various time intervals following the longest cessation attempt† | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ⩽1 week | ⩽1 month | ⩽6 months | ⩽1 year | |||

| Any use (in the past month) | ||||||

| Early to middle adolescence | ||||||

| Canada, 199437 | Age 10–14 | Longest time you ever quit smoking | 48‡§ | 67‡§ | 90‡§ | |

| United States, 1989–199074 | Age 12–13 | Longest time you stayed off cigarettes | 15 | 48 | 88 | 88 |

| Middle adolescence | ||||||

| United States, 1989–199074 | Age 14–15 | Longest time you stayed off cigarettes | 14 | 44 | 89 | 91 |

| Early to late adolescence | ||||||

| Canada, 199437 | Age 10–19 | Longest time you ever quit smoking | 41‡§ | 65‡§ | 90‡§ | 94§ |

| United States, 1989–199074 | Age 12–18 | Longest time you stayed off cigarettes | 16‡ | 47‡ | 89‡ | 91‡ |

| Middle to late adolescence | ||||||

| Canada, 199437 | Age 15–19 | Longest time you ever quit smoking | 39§ | 65§ | 91§ | 96||§ |

| Late adolescence | ||||||

| United States, 1989–199074 | Age 16–18 | Longest time you stayed off cigarettes | 17 | 48 | 89 | 92 |

| Daily use (in the past week) | ||||||

| Early to middle adolescence | ||||||

| Canada, 200470 | Grade 5–9 | Longest time successfully stopped smoking | 68 | 83 | ||

| Daily use (in the past month) | ||||||

| Early to middle adolescence | ||||||

| Canada, 199437 | Age 10–14 | Longest time you ever quit smoking | 73§ | |||

| Early to late adolescence | ||||||

| Canada, 199437 | Age 10–19 | Longest time you ever quit smoking | 49‡§ | 72§¶ | 92§ | 95§ |

| Middle to late adolescence | ||||||

| Canada, 199437 | Age 15–19 | Longest time you ever quit smoking | 46||§ | 71||§ | 93||§ | 97||§ |

| Non‐daily use (in the past month) | ||||||

| Early to middle adolescence | ||||||

| Canada, 199437 | Age 10–14 | Longest time you ever quit smoking | 30**§ | 54**§ | 82**§ | |

| Early to late adolescence | ||||||

| Canada, 199437 | Age 10–19 | Longest time you ever quit smoking | 26‡§ | 52‡§ | 86‡§ | 92§ |

| Middle to late adolescence | ||||||

| Canada, 199437 | Age 15–19 | Longest time you ever quit smoking | 18||**§ | 45||**§ | 85||**§ | |

*Any use in the past month was defined operationally as “smoked ⩾1 cigarette in the past 30 days”, except in Allen et al74 where it was defined as “smoked in the past 30 days”; daily use in the past week was defined operationally as: “smoked cigarettes on each of the 7 days preceding data collection”; daily use in the past month was defined operationally as: “smoked⩾1 cigarette each day in the past 30 days”; non‐daily use in the past month was defined operationally as: “smoked ⩾1 cigarette in the past 30 days, but not daily”.

†Findings for the duration of the longest cessation attempt were usually reported on an ordinal rather than on a continuous scale. Summary estimates could only be calculated where the responses were scaled similarly across multiple studies. The prevalence of relapse categories reported here were derived by combining multiple ordinal categories.

‡Excluded from the calculation of summary estimate because complete stratum‐specific estimates were available for this study.

§Estimated among the subgroup of adolescents who had smoked ⩾100 cigarettes in their lifetime.

||Excluded from the calculation of summary estimate because a more inclusive estimate was available.

¶Additional data were reported on the prevalence of relapse within 1 month following the longest cessation attempt according to the frequency of daily consumption among adolescents aged 10–19 who had consumed ⩾100 cigarettes in their lifetime and who had ever tried to quit smoking, as follows: 74 (16–20 cigarettes per day), 52 (⩽5 cigarettes per day).

**Estimate does not include quit attempts of ⩽1 day due to high sampling variability in this category. For 10–14 year olds, between 9–17% quit for ⩽1 day; for 15–19 year olds, between 5–7% quit for ⩽1 day.

No study reported the prevalence of relapse according to cumulative lifetime cigarette consumption, and only one study reported differences according to smoking frequency.37 That study found that the prevalence of relapse within 1 week or 1 month of the longest cessation attempt was higher among daily than among non‐daily smokers (table 5). However, differences according to smoking frequency diminished substantially for longer‐term cessation.

In the two studies that reported age‐specific estimates, the prevalence of relapse was similar across age categories. Although one study37 found a higher prevalence of early relapse (⩽1 week) among younger adolescent smokers, the other showed little difference across age groups.74 In both studies, the prevalence of relapse within 1, 6 and/or 12 months after the longest attempt was similar across age categories (table 5).

Discussion

The present review summarises estimates of the prevalence, frequency and duration of smoking cessation attempts among adolescent smokers generally, and according to age and level of cigarette consumption. Overall, among nationally representative populations of current smokers, the median estimates of the prevalence of any cessation attempt in the past 6 months, 12 months and ever were 58%, 68% and 71%. The high prevalence of cessation attempts was not limited to late adolescent or daily smokers, but was also observed among younger adolescent and non‐daily smokers. Most adolescent smokers had made multiple cessation attempts. Among those who had attempted cessation, the prevalence of relapse was high even soon after the longest cessation attempt. Although the prevalence of relapse within 1 week or 1 month of the longest cessation attempt was lower among non‐daily compared to daily smokers, all groups, irrespective of age or level of cigarette consumption, reported a high prevalence of relapse within 6 months of their longest cessation attempt. These findings provide evidence that could assist in determining which groups of adolescent smokers should be targeted for intervention.

The recommended timing for adolescent smoking cessation programs has ranged from as soon as possible after smoking onset (even among the youngest smokers) to only once habitual smoking begins or smokers have reached adulthood.21,23,26,37,76 Based on the data reviewed here, however, there is little reason to target early and/or middle adolescent or non‐daily smokers with any less intensity than late adolescent or daily smokers. Indeed, smokers in the former groups are at least as likely to have attempted cessation, suggesting that younger and/or non‐daily smokers are motivated to quit smoking. This is supported by other evidence on their thoughts and intentions concerning cessation, as well as the immediacy after smoking initiation that many attempt cessation.2,13,19,35,36,74,77,78,79 Yet the present review also demonstrates that these subgroups, like their late adolescent and/or daily smoking counterparts, often failed to maintain long‐term (6 months) abstinence after their longest attempts. Although population approaches, such as media campaigns or school non‐smoking policies target adolescent populations broadly, their effect on cessation, especially among non‐daily smokers, has not been established.30,80 Given that tobacco reduction interventions that are effective among regular smokers might not be effective among smokers in the early stages of onset,81 it is imperative that future cessation surveillance, research and program development be directed at this latter subgroup of smokers. Programs might need to address the specific needs of smokers in the early versus late stages of onset.82

What this paper adds

The high prevalence of attempts at smoking cessation is frequently offered as evidence of the need for smoking cessation interventions among adolescents. However, to date, there has been no attempt to synthesise prevalence estimates from the many studies that have examined the prevalence of attempts at smoking cessation among adolescents, with particular emphasis on (1) systematic samples, and (2) rigorous examination of how the study populations are characterised according to age and smoking status.

The present review of 52 nationally representative studies identifies the high prevalence of attempts at smoking cessation and relapse as an important problem among adolescent smokers that extends to young adolescents (aged <16 years) and non‐daily smokers.

Cessation surveillance, research and program development should be more inclusive of these subgroups.

Evidence remains limited on the prevalence of cessation attempts early in the smoking onset process (ie, among consumers of <100 cigarettes and among non‐daily smokers). In the few studies in which cessation among smokers in the early stages of onset was considered, lifetime cigarette consumption modified the effects of age and smoking frequency on the prevalence of any and of multiple cessation attempts. More specifically, adolescent smokers aged 10–14 who had consumed <100 cigarettes in their lifetime had the lowest cessation attempt prevalence of any other subgroup characterised according to age, smoking frequency, and/or cumulative consumption.37 Consistent with this, one previous longitudinal study demonstrated adolescents who initiated regular smoking at an earlier age delayed making their first cessation attempt.13 Yet, those who did attempt cessation at an earlier age were more likely to be successful.13 Adolescents might delay attempting cessation until they identify themselves as smokers. In addition, conventionally used indicators, such as those reported here, might not capture attempts at cessation among smokers in the earliest stages of onset. In order to extend surveillance to all adolescent smokers, cessation attempt indicators appropriate to adolescents in the early stages of smoking onset should be identified. In addition, future surveillance efforts should report cessation behaviours according to stage of smoking onset and age/grade; the latter indicator might serve as a proxy for multiple biological and psychosocial developmental stages.83,84,85

Limitations of this review include the following. First, most studies were limited in their generalisability because the sample was restricted to consumers of ⩾100 cigarettes and/or to adolescents who had already “seriously thought about quitting”. This could have led to an overestimation of the prevalence of cessation attempts. Consumption of ⩾100 cigarettes is a relatively late event in the smoking onset process,86 so that cessation activity among smokers in the early stages of onset was excluded. In addition, cessation attempts are more common among adolescent smokers who report positive cognitions regarding cessation than among those who do not report positive cognitions.87 This might have resulted in the exclusion of some current smokers who have attempted cessation, and who have since then given up on making any further cessation attempts. Also excluded are smokers who have achieved temporary abstinence without necessarily explicitly expressing any intention to do so.88,89,90 Indeed, one previous qualitative study indicated that even brief, unplanned, temporary, and unintentional “quitting” (eg, while waiting for the results of a pregnancy test; while on vacation with non‐smoking relatives or friends) are all considered by adolescent smokers as cessation attempts.90 Such unintentional attempts could be a relevant route to eventual abstinence.

Second, even the large‐scale national surveys reviewed here often lacked an adequate sample size to quantify cessation behaviours among subgroups of adolescent smokers. This resulted in high variability in some of the estimates and limited the statistical power to detect differences between subgroups of adolescent smokers. Moreover, the variability of estimates was often unknown due to the incomplete reporting of sample size, of the estimated variance, or of confidence intervals. Given the recent emphasis on ensuring access to appropriate and effective cessation interventions for all adolescent smokers, there is a need to monitor and evaluate the impact of these intensified efforts on the target population.

Third, we found a marked heterogeneity in the methods of reporting of cessation attempt outcomes. As reflected in the multiple and various definitions used in the studies reviewed, a consensual definition of a cessation attempt simply does not exist. Adolescent smokers might differentiate the term “quit” from the term “stop”, leading some researchers to suggest that the term “quit” should be preferred over the term “stop” in studies investigating attempts at permanent cessation.91 However, the similarity between prevalence estimates among the studies reviewed, irrespective of the terminology used, suggests that such qualitative distinctions do not systematically bias prevalence estimates measured in national surveys. By contrast, the wide discrepancy between estimates determined among adolescents who explicitly declared an inability to quit smoking relative to those which simply enumerated past cessation attempts, suggests that few adolescent smokers consider their past attempts as failures. Indeed, one recent qualitative study found that rather than attaching a sense of failure to previous cessation attempts, adolescents proudly shared stories of being able to stop smoking for short (eg, from hours to weeks) periods.76 However, despite defining these previous failed attempts as successes, a growing body of evidence suggests that adolescent smokers usually attempt cessation with the intent to cease smoking completely and forever (AG, unpublished results).76,91,92 Moreover, adolescents with shorter smoking histories might be more likely to characterise their attempts to stop as “stop permanently”.91

In conclusion, nationally representative surveys show that the prevalence of cessation attempts is high among adolescent smokers. Evidence that this high prevalence extends to both early adolescent and non‐daily smokers provides a rationale for proposing that smoking cessation surveillance, research and program development be more inclusive of these subgroups. National, population‐based studies of adolescent smokers should ensure adequate monitoring of cessation behaviours, particularly among the subgroups here identified. Recent policy recommendations advocate that every adolescent tobacco user have access to appropriate and effective cessation interventions.28,93 Extending cessation surveillance and research to the subgroups identified here is essential to the development of cessation programs that aim to help all adolescent smokers quit permanently, not only those who are daily smokers or who are approaching the end of their adolescence.

Acknowledgements

CB was the recipient of a Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) doctoral fellowship during the time this work was completed. JO'L holds a Canada Research Chair in the Early Determinants of Adult Chronic Disease. RWP holds a Chercheur‐boursier award from the Fonds de la recherche en santé Québec (FRSQ).

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.World Health Organization Child and adolescent health and development, overview of CAH. Adolescents: the sheer numbers. http://www.who.int/child‐adolescent‐health/OVERVIEW/AHD/adh_sheer.htm (accessed 3 May 2006)

- 2.US Department of Health and Human Services Preventing tobacco use among young people: a report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, Georgia: US Department of Health and Human Services, 1994

- 3.Myers M G, Brown S A. Smoking and health in substance‐abusing adolescents: a two‐year follow‐up. Pediatrics 199493561–566. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dwyer J H, Rieger‐Ndakorerwa G E, Semmer N K.et al Low‐level cigarette smoking and longitudinal change in serum cholesterol among adolescents. The Berlin–Bremen Study. JAMA 19882592857–2862. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Colby S M, Tiffany S T, Shiffman S.et al Are adolescent smokers dependent on nicotine? A review of the evidence. Drug Alcohol Depend 200059(Suppl 1)S83–S95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thomas R. School‐based programmes for preventing smoking. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 20024CD001293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Best J A, Thomson S J, Santi S M.et al Preventing cigarette smoking among school children. Annu Rev Public Health 19889161–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sussman S, Lichtman K, Ritt A.et al Effects of thirty‐four adolescent tobacco use cessation and prevention trials on regular users of tobacco products. Subst Use Misuse 1999341469–1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murray D M, Pirie P, Leupker R V.et al Five‐ and six‐year follow‐up results from four seventh‐grade smoking prevention strategies. J Behav Med 198912207–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson C A, Hansen W B, Collins L M.et al High‐school smoking prevention: results of a three‐year longitudinal study. J Behav Med 19869439–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pierce J P, Gilpin E. How long will today's new adolescent smoker be addicted to cigarettes? Am J Public Health 199686253–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stanton W R, Lowe J B, Gillespie A M. Adolescents' experiences of smoking cessation. Drug Alcohol Depend 19964363–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ershler J, Leventhal H, Fleming R.et al The quitting experience for smokers in sixth through twelfth grades. Addict Behav 198914365–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wellman R J, DiFranza J R, Savageau J A.et al Short term patterns of early smoking acquisition. Tob Control 200413251–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kelder S H, Perry C L, Klepp K I.et al Longitudinal tracking of adolescent smoking, physical activity, and food choice behaviors. Am J Public Health 1994841121–1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pirie P L, Murray D M, Luepker R V. Gender differences in cigarette smoking and quitting in a cohort of young adults. Am J Public Health 199181324–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McNeill A D. The development of dependence on smoking in children. Br J Addict 199186589–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stanton W R, McClelland M, Elwood C.et al Prevalence, reliability and bias of adolescents' reports of smoking and quitting. Addiction 1996911705–1714. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burt R D, Peterson A V., Jr Smoking cessation among high school seniors. Prev Med 199827319–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ariza‐Cardenal C, Nebot‐Adell M. Factors associated with smoking progression among Spanish adolescents. Health Educ Res 200217750–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laoye J A, Creswell W H, Jr, Stone D B. A cohort study of 1205 secondary school smokers. J Sch Health 19724247–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sargent J D, Mott L A, Stevens M. Predictors of smoking cessation in adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1998152388–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson J L, Bottorff J L, Moffat B.et al Tobacco dependence: adolescents' perspectives on the need to smoke. Soc Sci Med 2003561481–1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DiFranza J R, Rigotti N A, McNeill A D.et al Initial symptoms of nicotine dependence in adolescents. Tob Control 20009313–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O'Loughlin J, DiFranza J, Tyndale R F.et al Nicotine‐dependence symptoms are associated with smoking frequency in adolescents. Am J Prev Med 200325219–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lantz P M, Jacobson P D, Warner K E.et al Investing in youth tobacco control: a review of smoking prevention and control strategies. Tob Control 2000947–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Backinger C L, McDonald P, Ossip‐Klein D J.et al Improving the future of youth smoking cessation. Am J Health Behav 200327(Suppl 2)S170–S184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Orleans C T, Arkin E B, Backinger C L.et al Youth Tobacco Cessation Collaborative and National Blueprint for Action. Am J Health Behav 200327(Suppl 2)S103–S119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.US Department of Health and Human Services Healthy people 2010: understanding and improving health. 2nd edn. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 2000

- 30.Zhu S H, Sun J, Billings S C.et al Predictors of smoking cessation in US adolescents. Am J Prev Med 199916(3)202–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Warren C W, Riley L, Asma S.et al Tobacco use by youth: a surveillance report from the Global Youth Tobacco Survey project. Bull World Health Organ 200078868–876. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Precht D H, Keiding L, Madsen M. Smoking patterns among adolescents with asthma attending upper secondary schools: a community‐based study. Pediatrics 2003111(5 Pt 1)e562–e568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.The Global Youth Tobacco Survey Collaborative Group Tobacco use among youth: a cross country comparison. Tob Control 200211252–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sovinova H, Csemy L. Smoking behaviour of Czech adolescents: results of the Global Youth Tobacco Survey in the Czech Republic, 2002. Cent Eur J Public Health 20041226–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention CDC surveillance summaries, youth tobacco surveillance – United States, 1998–1999. MMWR 2000491–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention CDC surveillance summaries, youth tobacco surveillance – United States, 2000. MMWR 2001501–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brown K S, Pederson L L. Smoking cessation. In: Stephens T, Morin M, eds. Youth smoking survey, 1994: technical report. Ottawa, Canada: Ministry of Supply and Services Canada, 1996

- 38.Miguel‐Baquilod M. Report on the results of the national youth tobacco survey in the Philippines GYTS 2000. http://www.cdc.gov/Tobacco/global/gyts/reports/wpro/2000/philippines01.htm (accessed 15 Sep 2005)

- 39.Swart D, Reddy P, Pitt B.et al The prevalence and determinants of tobacco use among Grade 8–10 learners in South Africa. The Global Youth Tobacco school‐based survey. http://www.cdc.gov/Tobacco/global/gyts/reports/afro/1999/SA_REPORT1.htm (accessed 4 Sep 2005)

- 40.Bovet P, Viswanathan B, Warren W. The Global Youth Tobacco Survey in the Seychelles‐2002. http://www.afro.who.int/tfi/projects/report‐gyts‐sey_31dec02_.pdf (accessed 12 Sep 2005)

- 41.Anon Report on the results of the Global Youth Tobacco Survey in Grenada 2000. http://www.cdc.gov/Tobacco/global/gyts/reports/paho/2000/grenada_2000_PAHO1.htm (accessed 15 Sep 2005)

- 42.Granero R. Report on the results of the Global Youth Tobacco Survey in Venezuela (GYTS Venezuela). http://www.cdc.gov/Tobacco/global/gyts/reports/ pdf/venezuela00 pdf (accessed 15 Sep 2005)

- 43.Nikolaishvili N, Gamkrelidze A. 2002 Global Youth Tobacco Survey (GYTS) Georgia Report. http://www.cdc.gov/Tobacco/global/gyts/reports/euro/2002/ Georgia_2002_Euro01 htm (accessed 19 Sep 2005)

- 44.Juricic M. Report on the results of the Global Youth Tobacco Survey in Slovenia 2003. http://www.cdc.gov/Tobacco/global/gyts/reports/euro/2003/slovenia_2003_EURO1.htm (accessed 15 Sep 2005)

- 45.GYTS Slovakia, 2003 Collaborative Group Report on the results of the Global Youth Tobacco Survey in Slovakia 2003. http://www.cdc.gov/Tobacco/global/gyts/reports/euro/2003/slovakia_2003_EURO1.htm (accessed 15 Sep 2005)

- 46.Anon Report on the results of the Global Youth Tobacco Survey in Serbia 2003. http://www.cdc.gov/Tobacco/global/gyts/reports/euro/2003/Serbia_2003_Euro1.htm (accessed 29 Sep 2005)

- 47.Henry J. Report on the results of the Global Youth Tobacco Survey in Dominica 2000. http://www.cdc.gov/Tobacco/global/gyts/reports/paho/2000/Dominica_2000_Paho01.htm (accessed 22 Sep 2005)

- 48.Prendergast K, Ashley D. Report on the results of the Global Youth Tobacco Survey in Jamaica 2001. http://www.cdc gov/Tobacco/global/gyts/reports/paho/2001/Jamaica_2001_Paho01.h tm (accessed 22 Sep 2005)

- 49.Carr B ‐ A, Alleyne L, Renaud D. Report on the results of the Global Youth Tobacco Survey in Trinidad and Tobago 2000. http://www.cdc.gov/Tobacco/global/gyts/reports/paho/2000/Trinidad_and_Tobago_2000_Paho01.htm (accessed 22 Sep 2005)

- 50.United States Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Division of Adolescent and School Health YRBSS, youth online: comprehensive results, 2001. http://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/yrbss (accessed 4 Oct 2004)

- 51.United States Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Division of Adolescent and School Health YRBSS, youth online: comprehensive results, 2003. http://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/yrbss (accessed 5 October 2004)

- 52.Environmental Health Unit Report on the results of the Global Youth Tobacco Survey in Botswana 2002. http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/global/gyts/reports/afro/2002/botswana_2002_AFRO1.htm (accessed 22 Sep 2005)

- 53.Nemeth A. Global Youth Tobacco Survey Hungary, national report, 2003. http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/global/gyts/reports/euro/2003/hungary01.htm (accessed 17 Sep 2005)

- 54.Public Health Department, Ministry of Health, Kingdom of Bahrain Report on the results of the Global Youth Tobacco Survey in Bahrain 2003. http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/global/gyts/reports/emro/2003/bahrain_2003_ermo.htm (accessed 22 Sep 2005)

- 55.Fikri M, Abi Saab B H. Report on the results of the Global Youth Tobacco Survey in United Arab Emirates. http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/global/gyts/reports/emro/2002/uae01.htm (accessed 14 Sep 2005)

- 56.Helmi S, Al‐Lawati J, Shuaili I. Report on the results of the Global Youth Tobacco Survey in Oman. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/global/gyts/reports/emro/2003/oman_2003_ermo1.htm (accessed 14 Sep 2005)